Fleurs du Mal Magazine

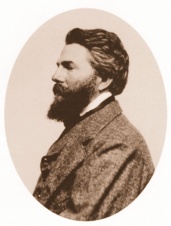

Hart Crane

(1889 – 1932)

My Grandmother’s Love Letters

There are no stars to-night

But those of memory.

Yet how much room for memory there is

In the loose girdle of soft rain.

There is even room enough

For the letters of my mother’s mother,

Elizabeth,

That have been pressed so long

Into a corner of the roof

That they are brown and soft,

And liable to melt as snow.

Over the greatness of such space

Steps must be gentle.

It is all hung by an invisible white hair.

It trembles as birch limbs webbing the air.

And I ask myself:

“Are your fingers long enough to play

Old keys that are but echoes:

Is the silence strong enough

To carry back the music to its source

And back to you again

As though to her?”

Yet I would lead my grandmother by the hand

Through much of what she would not understand;

And so I stumble. And the rain continues on the roof

With such a sound of gently pitying laughter.

Hart Crane poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crane, Hart

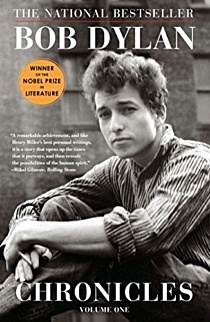

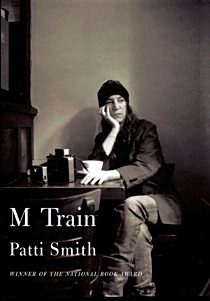

Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature 2016

Bob Dylan born: 24 May 1941, Duluth, MN, USA – Nobel Prize motivation: “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” – Bob Dylan (not present at the ceremony) writes Nobel prize speech & Patti Smith will perform Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” on the Nobel banquet on Dec 10, 2016

Bob Dylan’s Albums

Bob Dylan (1962)

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963)

The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964)

Another Side Of Bob Dylan (1964)

Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

Blonde On Blonde (1966)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (1967)

John Wesley Harding (1968)

Nashville Skyline (1969)

Self Portrait (1970)

New Morning (1970)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. 2 (1971)

Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid (1973)

Dylan (1973)

Planet Waves (1974)

Before The Flood (1974)

Blood On The Tracks (1975)

The Basement Tapes (1975)

Desire (1976)

Hard Rain (1976)

Street Legal (1978)

Bob Dylan At Budokan (1978)

Slow Train Coming (1979)

Saved (1980)

Shot Of Love (1981)

Infidels (1983)

Real Live (1984)

Empire Burlesque (1985)

Biograph (1985)

Knocked Out Loaded (1986)

Down In The Groove (1988)

Dylan & The Dead (1989)

Oh Mercy (1989)

Under The Red Sky (1990)

The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3: Rare And Unreleased 1961-1991 (1991)

Good As I Been to You (1992)

World Gone Wrong (1993)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. 3 (1994)

MTV Unplugged (1995)

The Best Of Bob Dylan (1997)

The Songs Of Jimmie Rodgers: A Tribute (1997)

Time Out Of Mind (1997)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966: The ’Royal Albert Hall’ Concert (1998)

The Essential Bob Dylan (2000)

”Love And Theft” (2001)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5: Live 1975: The Rolling Thunder Revue (2002)

Masked And Anonymous: The Soundtrack (2003)

Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs Of Bob Dylan (2003)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 6: Live 1964: Concert At Philharmonic Hall (2004)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack (2005)

Live At The Gaslight 1962 (2005)

Live At Carnegie Hall 1963 (2005)

Modern Times (2006)

The Traveling Wilburys Collection (2007)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare And Unreleased, 1989-2006 (2008)

Together Through Life (2009)

Christmas In The Heart (2009)

The Original Mono Recordings (2010)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos: 1962-1964 (2010)

Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy Of Sun (2011)

Timeless (2011)

Tempest (2012)

The Lost Notebooks Of Hank Williams (2011)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (2013)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete (2014)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966 (2015)

Shadows In The Night (2015)

Fallen Angels (2016)

Nobel Prizes in Literature since 2000

Nobel Prizes in Literature since 2000

2016, Bob Dylan “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”

2015, Svetlana Alexievich “for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time”

2014, Patrick Modiano “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world of the occupation”

2013, Alice Munro “master of the contemporary short story”

2012, Mo Yan “who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary”

2011, Tomas Tranströmer “because, through his condensed, translucent images, he gives us fresh access to reality”

2010, Mario Vargas Llosa “for his cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual’s resistance, revolt, and defeat”

2009, Herta Müller “who, with the concentration of poetry and the frankness of prose, depicts the landscape of the dispossessed”

2008, Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio “author of new departures, poetic adventure and sensual ecstasy, explorer of a humanity beyond and below the reigning civilization”

2007, Doris Lessing “that epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny”

2006, Orhan Pamuk “who in the quest for the melancholic soul of his native city has discovered new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures”

2005, Harold Pinter “who in his plays uncovers the precipice under everyday prattle and forces entry into oppression’s closed rooms”

2004, Elfriede Jelinek “for her musical flow of voices and counter-voices in novels and plays that with extraordinary linguistic zeal reveal the absurdity of society’s clichés and their subjugating power”

2003, John M. Coetzee “who in innumerable guises portrays the surprising involvement of the outsider”

2002, Imre Kertész “for writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history”

2001, Sir Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul “for having united perceptive narrative and incorruptible scrutiny in works that compel us to see the presence of suppressed histories”

2000, Gao Xingjian “for an æuvre of universal validity, bitter insights and linguistic ingenuity, which has opened new paths for the Chinese novel and drama”

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, Archive C-D, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Bob Dylan, Dylan, Bob, Patti Smith, Smith, Patti, THEATRE

Felicia Hemans

The last song of Sappho

Sound on, thou dark unslumbering sea!

My dirge is in thy moan;

My spirit finds response in thee,

To its own ceaseless cry–’Alone, alone !’

Yet send me back one other word,

Ye tones that never cease !

Oh ! let your secret caves be stirr’d,

And say, dark waters! will ye give me peace?

Away! my weary soul hath sought

In vain one echoing sigh,

One answer to consuming thought

In human hearts–and will the wave reply ?

Sound on, thou dark, unslumbering sea!

Sound in thy scorn and pride !

I ask not, alien world, from thee,

What my own kindred earth hath still denied.

And yet I loved that earth so well,

With all its lovely things!

–Was it for this the death-wind fell

On my rich lyre, and quench’d its living strings?

–Let them lie silent at my feet !

Since broken even as they,

The heart whose music made them sweet,

Hath pour’d on desert-sands its wealth away.

Yet glory’s light hath touch’d my name,

The laurel-wreath is mine–

–With a lone heart, a weary frame–

O restless deep ! I come to make them thine !

Give to that crown, that burning crown,

Place in thy darkest hold!

Bury my anguish, my renown,

With hidden wrecks, lost gems, and wasted gold.

Thou sea-bird on the billow’s crest,

Thou hast thy love, thy home;

They wait thee in the quiet nest,

And I, the unsought, unwatch’d-for–I too come!

I, with this winged nature fraught,

These visions wildly free,

This boundless love, this fiery thought–

Alone I come–oh ! give me peace, dark sea!

Felicia Hemans (1793 – 1835)

The last song of Sappho

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive S-T, CLASSIC POETRY, Sappho

Max Jacob

(1876 – 1944)

Contes

Je me suis trompé d’étage

et de soirée mondaine.

Bah ! ce sera la même chose,

les gens se ressemblent,

l’appartement,

les meubles et le buffet.

Mais non ! ce sont des étrangers!

Vous croyez?

L’escalier!

on monte!

on redescend!

il est tard.

La soirée a bien changé d’aspect!

à l’autre étage aussi.

Au bord d’une herbe tendre

Je les ai vus passer

Et que faut-il comprendre

A les voir enlacés?

C’était un polyglotte

Du nom de

Rustifan

Et avait une grotte

Avec ses partisans.

Elle aime les dolmans.

J’aime les

Allemandes.

Nous aurons des enfants

Si

Dieu nous en demande.

Nous aurons des enfants

Faits par la propagande.

Nous aurons des enfants

Au linge damassé.

Max Jacob poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jacob, Max

The Mortal Immortal

The Mortal Immortal

by Mary Shelley

July 16, 1833. — This is a memorable anniversary for me; on it I complete my three hundred and twenty-third year!

The Wandering Jew? — certainly not. More than eighteen centuries have passed over his head. In comparison with him, I am a very young Immortal.

Am I, then, immortal? This is a question which I have asked myself, by day and night, for now three hundred and three years, and yet cannot answer it. I detected a grey hair amidst my brown locks this very day — that surely signifies decay. Yet it may have remained concealed there for three hundred years — for some persons have become entirely white-headed before twenty years of age.

I will tell my story, and my reader shall judge for me. I will tell my story, and so contrive to pass some few hours of a long eternity, become so wearisome to me. For ever! Can it be? to live for ever! I have heard of enchantments, in which the victims were plunged into a deep sleep, to wake, after a hundred years, as fresh as ever: I have heard of the Seven Sleepers — thus to be immortal would not be so burthensome: but, oh! the weight of never-ending time — the tedious passage of the still-succeeding hours! How happy was the fabled Nourjahad! — But to my task.

All the world has heard of Cornelius Agrippa. His memory is as immortal as his arts have made me. All the world has also heard of his scholar, who, unawares, raised the foul fiend during his master’s absence, and was destroyed by him. The report, true or false, of this accident, was attended with many inconveniences to the renowned philosopher. All his scholars at once deserted him — his servants disappeared. He had no one near him to put coals on his ever-burning fires while he slept, or to attend to the changeful colours of his medicines while he studied. Experiment after experiment failed, because one pair of hands was insufficient to complete them: the dark spirits laughed at him for not being able to retain a single mortal in his service.

I was then very young — very poor — and very much in love. I had been for about a year the pupil of Cornelius, though I was absent when this accident took place. On my return, my friends implored me not to return to the alchymist’s abode. I trembled as I listened to the dire tale they told; I required no second warning; and when Cornelius came and offered me a purse of gold if I would remain under his roof, I felt as if Satan himself tempted me. My teeth chattered — my hair stood on end; — I ran off as fast as my trembling knees would permit.

My failing steps were directed whither for two years they had every evening been attracted, — a gently bubbling spring of pure living water, beside which lingered a dark-haired girl, whose beaming eyes were fixed on the path I was accustomed each night to tread. I cannot remember the hour when I did not love Bertha; we had been neighbours and playmates from infancy, — her parents, like mine were of humble life, yet respectable, — our attachment had been a source of pleasure to them. In an evil hour, a malignant fever carried off both her father and mother, and Bertha became an orphan. She would have found a home beneath my paternal roof, but, unfortunately, the old lady of the near castle, rich, childless, and solitary, declared her intention to adopt her. Henceforth Bertha was clad in silk — inhabited a marble palace — and was looked on as being highly favoured by fortune. But in her new situation among her new associates, Bertha remained true to the friend of her humbler days; she often visited the cottage of my father, and when forbidden to go thither, she would stray towards the neighbouring wood, and meet me beside its shady fountain.

She often declared that she owed no duty to her new protectress equal in sanctity to that which bound us. Yet still I was too poor to marry, and she grew weary of being tormented on my account. She had a haughty but an impatient spirit, and grew angry at the obstacle that prevented our union. We met now after an absence, and she had been sorely beset while I was away; she complained bitterly, and almost reproached me for being poor. I replied hastily, —

“I am honest, if I am poor! — were I not, I might soon become rich!”

This exclamation produced a thousand questions. I feared to shock her by owning the truth, but she drew it from me; and then, casting a look of disdain on me, she said, —

“You pretend to love, and you fear to face the Devil for my sake!”

I protested that I had only dreaded to offend her; — while she dwelt on the magnitude of the reward that I should receive. Thus encouraged — shamed by her — led on by love and hope, laughing at my later fears, with quick steps and a light heart, I returned to accept the offers of the alchymist, and was instantly installed in my office.

A year passed away. I became possessed of no insignificant sum of money. Custom had banished my fears. In spite of the most painful vigilance, I had never detected the trace of a cloven foot; nor was the studious silence of our abode ever disturbed by demoniac howls. I still continued my stolen interviews with Bertha, and Hope dawned on me — Hope — but not perfect joy: for Bertha fancied that love and security were enemies, and her pleasure was to divide them in my bosom. Though true of heart, she was something of a coquette in manner; I was jealous as a Turk. She slighted me in a thousand ways, yet would never acknowledge herself to be in the wrong. She would drive me mad with anger, and then force me to beg her pardon. Sometimes she fancied that I was not sufficiently submissive, and then she had some story of a rival, favoured by her protectress. She was surrounded by silk-clad youths — the rich and gay. What chance had the sad-robed scholar of Cornelius compared with these?

On one occasion, the philosopher made such large demands upon my time, that I was unable to meet her as I was wont. He was engaged in some mighty work, and I was forced to remain, day and night, feeding his furnaces and watching his chemical preparations. Bertha waited for me in vain at the fountain. Her haughty spirit fired at this neglect; and when at last I stole out during a few short minutes allotted to me for slumber, and hoped to be consoled by her, she received me with disdain, dismissed me in scorn, and vowed that any man should possess her hand rather than he who could not be in two places at once for her sake. She would be revenged! And truly she was. In my dingy retreat I heard that she had been hunting, attended by Albert Hoffer. Albert Hoffer was favoured by her protectress, and the three passed in cavalcade before my smoky window. Methought that they mentioned my name; it was followed by a laugh of derision, as her dark eyes glanced contemptuously towards my abode.

Jealousy, with all its venom and all its misery, entered my breast. Now I shed a torrent of tears, to think that I should never call her mine; and, anon, I imprecated a thousand curses on her inconstancy. Yet, still I must stir the fires of the alchymist, still attend on the changes of his unintelligible medicines.

Cornelius had watched for three days and nights, nor closed his eyes. The progress of his alembics was slower than he expected: in spite of his anxiety, sleep weighted upon his eyelids. Again and again he threw off drowsiness with more than human energy; again and again it stole away his senses. He eyed his crucibles wistfully. “Not ready yet,” he murmured; “will another night pass before the work is accomplished? Winzy, you are vigilant — you are faithful — you have slept, my boy — you slept last night. Look at that glass vessel. The liquid it contains is of a soft rose-colour: the moment it begins to change hue, awaken me — till then I may close my eyes. First, it will turn white, and then emit golden flashes; but wait not till then; when the rose-colour fades, rouse me.” I scarcely heard the last words, muttered, as they were, in sleep. Even then he did not quite yield to nature. “Winzy, my boy,” he again said, “do not touch the vessel — do not put it to your lips; it is a philtre — a philtre to cure love; you would not cease to love your Bertha — beware to drink!”

And he slept. His venerable head sunk on his breast, and I scarce heard his regular breathing. For a few minutes I watched the vessel — the rosy hue of the liquid remained unchanged. Then my thoughts wandered — they visited the fountain, and dwelt on a thousand charming scenes never to be renewed — never! Serpents and adders were in my heart as the word “Never!” half formed itself on my lips. False girl! — false and cruel! Never more would she smile on me as that evening she smiled on Albert. Worthless, detested woman! I would not remain unrevenged — she should see Albert expire at her feet — she should die beneath my vengeance. She had smiled in disdain and triumph — she knew my wretchedness and her power. Yet what power had she? — the power of exciting my hate — my utter scorn — my — oh, all but indifference! Could I attain that — could I regard her with careless eyes, transferring my rejected love to one fairer and more true, that were indeed a victory!

A bright flash darted before my eyes. I had forgotten the medicine of the adept; I gazed on it with wonder: flashes of admirable beauty, more bright than those which the diamond emits when the sun’s rays are on it, glanced from the surface of the liquid; and odour the most fragrant and grateful stole over my sense; the vessel seemed one globe of living radiance, lovely to the eye, and most inviting to the taste. The first thought, instinctively inspired by the grosser sense, was, I will — I must drink. I raised the vessel to my lips. “It will cure me of love — of torture!” Already I had quaffed half of the most delicious liquor ever tasted by the palate of man, when the philosopher stirred. I started — I dropped the glass — the fluid flamed and glanced along the floor, while I felt Cornelius’s gripe at my throat, as he shrieked aloud, “Wretch! you have destroyed the labour of my life!”

The philosopher was totally unaware that I had drunk any portion of his drug. His idea was, and I gave a tacit assent to it, that I had raised the vessel from curiosity, and that, frightened at its brightness, and the flashes of intense light it gave forth, I had let it fall. I never undeceived him. The fire of the medicine was quenched — the fragrance died away — he grew calm, as a philosopher should under the heaviest trials, and dismissed me to rest.

I will not attempt to describe the sleep of glory and bliss which bathed my soul in paradise during the remaining hours of that memorable night. Words would be faint and shallow types of my enjoyment, or of the gladness that possessed my bosom when I woke. I trod air — my thoughts were in heaven. Earth appeared heaven, and my inheritance upon it was to be one trance of delight. “This it is to be cured of love,” I thought; “I will see Bertha this day, and she will find her lover cold and regardless; too happy to be disdainful, yet how utterly indifferent to her!”

The hours danced away. The philosopher, secure that he had once succeeded, and believing that he might again, began to concoct the same medicine once more. He was shut up with his books and drugs, and I had a holiday. I dressed myself with care; I looked in an old but polished shield which served me for a mirror; methoughts my good looks had wonderfully improved. I hurried beyond the precincts of the town, joy in my soul, the beauty of heaven and earth around me. I turned my steps toward the castle — I could look on its lofty turrets with lightness of heart, for I was cured of love. My Bertha saw me afar off, as I came up the avenue. I know not what sudden impulse animated her bosom, but at the sight, she sprung with a light fawn-like bound down the marble steps, and was hastening towards me. But I had been perceived by another person. The old high-born hag, who called herself her protectress, and was her tyrant, had seen me also; she hobbled, panting, up the terrace; a page, as ugly as herself, held up her train, and fanned her as she hurried along, and stopped my fair girl with a “How, now, my bold mistress? whither so fast? Back to your cage — hawks are abroad!”

Bertha clasped her hands — her eyes were still bent on my approaching figure. I saw the contest. How I abhorred the old crone who checked the kind impulses of my Bertha’s softening heart. Hitherto, respect for her rank had caused me to avoid the lady of the castle; now I disdained such trivial considerations. I was cured of love, and lifted above all human fears; I hastened forwards, and soon reached the terrace. How lovely Bertha looked! her eyes flashing fire, her cheeks glowing with impatience and anger, she was a thousand times more graceful and charming than ever. I no longer loved — oh no! I adored — worshipped — idolized her!

She had that morning been persecuted, with more than usual vehemence, to consent to an immediate marriage with my rival. She was reproached with the encouragement that she had shown him — she was threatened with being turned out of doors with disgrace and shame. Her proud spirit rose in arms at the threat; but when she remembered the scorn that she had heaped upon me, and how, perhaps, she had thus lost one whom she now regarded as her only friend, she wept with remorse and rage. At that moment I appeared. “Oh, Winzy!” she exclaimed, “take me to your mother’s cot; swiftly let me leave the detested luxuries and wretchedness of this noble dwelling — take me to poverty and happiness.”

I clasped her in my arms with transport. The old dame was speechless with fury, and broke forth into invective only when we were far on the road to my natal cottage. My mother received the fair fugitive, escaped from a gilt cage to nature and liberty, with tenderness and joy; my father, who loved her, welcomed her heartily; it was a day of rejoicing, which did not need the addition of the celestial potion of the alchymist to steep me in delight.

Soon after this eventful day, I became the husband of Bertha. I ceased to be the scholar of Cornelius, but I continued his friend. I always felt grateful to him for having, unaware, procured me that delicious draught of a divine elixir, which, instead of curing me of love (sad cure! solitary and joyless remedy for evils which seem blessings to the memory), had inspired me with courage and resolution, thus winning for me an inestimable treasure in my Bertha.

I often called to mind that period of trance-like inebriation with wonder. The drink of Cornelius had not fulfilled the task for which he affirmed that it had been prepared, but its effects were more potent and blissful than words can express. They had faded by degrees, yet they lingered long — and painted life in hues of splendour. Bertha often wondered at my lightness of heart and unaccustomed gaiety; for, before, I had been rather serious, or even sad, in my disposition. She loved me the better for my cheerful temper, and our days were winged by joy.

Five years afterwards I was suddenly summoned to the bedside of the dying Cornelius. He had sent for me in haste, conjuring my instant presence. I found him stretched on his pallet, enfeebled even to death; all of life that yet remained animated his piercing eyes, and they were fixed on a glass vessel, full of roseate liquid.

“Behold,” he said, in a broken and inward voice, “the vanity of human wishes! a second time my hopes are about to be crowned, a second time they are destroyed. Look at that liquor — you may remember five years ago I had prepared the same, with the same success; — then, as now, my thirsting lips expected to taste the immortal elixir — you dashed it from me! and at present it is too late.”

He spoke with difficulty, and fell back on his pillow. I could not help saying, —

“How, revered master, can a cure for love restore you to life?”

A faint smile gleamed across his face as I listened earnestly to his scarcely intelligible answer.

“A cure for love and for all things — the Elixir of Immortality. Ah! if now I might drink, I should live for ever!”

As he spoke, a golden flash gleamed from the fluid; a well-remembered fragrance stole over the air; he raised himself, all weak as he was — strength seemed miraculously to re-enter his frame — he stretched forth his hand — a loud explosion startled me — a ray of fire shot up from the elixir, and the glass vessel which contained it was shivered to atoms! I turned my eyes towards the philosopher; he had fallen back — his eyes were glassy — his features rigid — he was dead!

But I lived, and was to live for ever! So said the unfortunate alchymist, and for a few days I believed his words. I remembered the glorious intoxication that had followed my stolen draught. I reflected on the change I had felt in my frame — in my soul. The bounding elasticity of the one — the buoyant lightness of the other. I surveyed myself in a mirror, and could perceive no change in my features during the space of the five years which had elapsed. I remembered the radiant hues and grateful scent of that delicious beverage — worthy the gift it was capable of bestowing — I was, then,IMMORTAL!

A few days after I laughed at my credulity. The old proverb, that “a prophet is least regarded in his own country,” was true with respect to me and my defunct master. I loved him as a man — I respected him as a sage — but I derided the notion that he could command the powers of darkness, and laughed at the superstitious fears with which he was regarded by the vulgar. He was a wise philosopher, but had no acquaintance with any spirits but those clad in flesh and blood. His science was simply human; and human science, I soon persuaded myself, could never conquer nature’s laws so far as to imprison the soul for ever within its carnal habitation. Cornelius had brewed a soul-refreshing drink — more inebriating than wine — sweeter and more fragrant than any fruit: it possessed probably strong medicinal powers, imparting gladness to the heart and vigour to the limbs; but its effects would wear out; already they were diminished in my frame. I was a lucky fellow to have quaffed health and joyous spirits, and perhaps a long life, at my master’s hands; but my good fortune ended there: longevity was far different from immortality.

I continued to entertain this belief for many years. Sometimes a thought stole across me — Was the alchymist indeed deceived? But my habitual credence was, that I should meet the fate of all the children of Adam at my appointed time — a little late, but still at a natural age. Yet it was certain that I retained a wonderfully youthful look. I was laughed at for my vanity in consulting the mirror so often, but I consulted it in vain — my brow was untrenched — my cheeks — my eyes — my whole person continued as untarnished as in my twentieth year.

I was troubled. I looked at the faded beauty of Bertha — I seemed more like her son. By degrees our neighbors began to make similar observations, and I found at last that I went by the name of the Scholar bewitched. Bertha herself grew uneasy. She became jealous and peevish, and at length she began to question me. We had no children; we were all in all to each other; and though, as she grew older, her vivacious spirit became a little allied to ill-temper, and her beauty sadly diminished, I cherished her in my heart as the mistress I idolized, the wife I had sought and won with such perfect love.

At last our situation became intolerable: Bertha was fifty — I twenty years of age. I had, in very shame, in some measure adopted the habits of advanced age; I no longer mingled in the dance among the young and gay, but my heart bounded along with them while I restrained my feet; and a sorry figure I cut among the Nestors of our village. But before the time I mention, things were altered — we were universally shunned; we were — at least, I was — reported to have kept up an iniquitous acquaintance with some of my former master’s supposed friends. Poor Bertha was pitied, but deserted. I was regarded with horror and detestation.

What was to be done? we sat by our winter fire — poverty had made itself felt, for none would buy the produce of my farm; and often I had been forced to journey twenty miles to some place where I was not known, to dispose of our property. It is true, we had saved something for an evil day — that day was come.

We sat by our lone fireside — the old-hearted youth and his antiquated wife. Again Bertha insisted on knowing the truth; she recapitulated all she had ever heard said about me, and added her own observations. She conjured me to cast off the spell; she described how much more comely grey hairs were than my chestnut locks; she descanted on the reverence and respect due to age — how preferable to the slight regard paid to mere children: could I imagine that the despicable gifts of youth and good looks outweighed disgrace, hatred and scorn? Nay, in the end I should be burnt as a dealer in the black art, while she, to whom I had not deigned to communicate any portion of my good fortune, might be stoned as my accomplice. At length she insinuated that I must share my secret with her, and bestow on her like benefits to those I myself enjoyed, or she would denounce me — and then she burst into tears.

Thus beset, methought it was the best way to tell the truth. I reveled it as tenderly as I could, and spoke only of a very long life, not of immortality — which representation, indeed, coincided best with my own ideas. When I ended I rose and said,–

“And now, my Bertha, will you denounce the lover of your youth? — You will not, I know. But it is too hard, my poor wife, that you should suffer for my ill-luck and the accursed arts of Cornelius. I will leave you — you have wealth enough, and friends will return in my absence. I will go; young as I seem and strong as I am, I can work and gain my bread among strangers, unsuspected and unknown. I loved you in youth; God is my witness that I would not desert you in age, but that your safety and happiness require it.”

I took my cap and moved toward the door; in a moment Bertha’s arms were round my neck, and her lips were pressed to mine. “No, my husband, my Winzy,” she said, “you shall not go alone — take me with you; we will remove from this place, and, as you say, among strangers we shall be unsuspected and safe. I am not so old as quite to shame you, my Winzy; and I daresay the charm will soon wear off, and, with the blessing of God, you will become more elderly-looking, as is fitting; you shall not leave me.”

I returned the good soul’s embrace heartily. “I will not, my Bertha; but for your sake I had not thought of such a thing. I will be your true, faithful husband while you are spared to me, and do my duty by you to the last.”

The next day we prepared secretly for our emigration. We were obliged to make great pecuniary sacrifices — it could not be helped. We realized a sum sufficient, at least, to maintain us while Bertha lived; and, without saying adieu to any one, quitted our native country to take refuge in a remote part of western France.

It was a cruel thing to transport poor Bertha from her native village, and the friends of her youth, to a new country, new language, new customs. The strange secret of my destiny rendered this removal immaterial to me; but I compassionated her deeply, and was glad to perceive that she found compensation for her misfortunes in a variety of little ridiculous circumstances. Away from all tell-tale chroniclers, she sought to decrease the apparent disparity of our ages by a thousand feminine arts — rouge, youthful dress, and assumed juvenility of manner. I could not be angry. Did I not myself wear a mask? Why quarrel with hers, because it was less successful? I grieved deeply when I remembered that this was my Bertha, whom I had loved so fondly and won with such transport — the dark-eyed, dark-haired girl, with smiles of enchanting archness and a step like a fawn — this mincing, simpering, jealous old woman. I should have revered her grey locks and withered cheeks; but thus! — It was my work, I knew; but I did not the less deplore this type of human weakness.

Her jealously never slept. Her chief occupation was to discover that, in spite of outward appearances, I was myself growing old. I verily believe that the poor soul loved me truly in her heart, but never had woman so tormenting a mode of displaying fondness. She would discern wrinkles in my face and decrepitude in my walk, while I bounded along in youthful vigour, the youngest looking of twenty youths. I never dared address another woman. On one occasion, fancying that the belle of the village regarded me with favouring eyes, she brought me a grey wig. Her constant discourse among her acquaintances was, that though I looked so young, there was ruin at work within my frame; and she affirmed that the worst symptom about me was my apparent health. My youth was a disease, she said, and I ought at all times to prepare, if not for a sudden and awful death, at least to awake some morning white-headed and bowed down with all the marks of advanced years. I let her talk — I often joined in her conjectures. Her warnings chimed in with my never-ceasing speculations concerning my state, and I took an earnest, though painful, interest in listening to all that her quick wit and excited imagination could say on the subject.

Why dwell on these minute circumstances? We lived on for many long years. Bertha became bedrid and paralytic; I nursed her as a mother might a child. She grew peevish, and still harped upon one string — of how long I should survive her. It has ever been a source of consolation to me, that I performed my duty scrupulously towards her. She had been mine in youth, she was mine in age; and at last, when I heaped the sod over her corpse, I wept to feel that I had lost all that really bound me to humanity.

Since then how many have been my cares and woes, how few and empty my enjoyments! I pause here in my history — I will pursue it no further. A sailor without rudder or compass, tossed on a stormy sea — a traveller lost on a widespread heath, without landmark or stone to guide him — such I have been: more lost, more hopeless than either. A nearing ship, a gleam from some far cot, may save them; but I have no beacon except the hope of death.

Death! mysterious, ill-visaged friend of weak humanity! Why alone of all mortals have you cast me from your sheltering fold? Oh, for the peace of the grave! the deep silence of the iron-bound tomb! that thought would cease to work in my brain, and my heart beat no more with emotions varied only by new forms of sadness!

Am I immortal? I return to my first question. In the first place, is it not more probably that the beverage of the alchymist was fraught rather with longevity than eternal life? Such is my hope. And then be it remembered, that I only drank half of the potion prepared by him. Was not the whole necessary to complete the charm? To have drained half the Elixir of Immortality is but to be half-immortal — my For-ever is thus truncated and null.

But again, who shall number the years of the half of eternity? I often try to imagine by what rule the infinite may be divided. Sometimes I fancy age advancing upon me. One grey hair I have found. Fool! do I lament? Yes, the fear of age and death often creeps coldly into my heart; and the more I live, the more I dread death, even while I abhor life. Such an enigma is man — born to perish — when he wars, as I do, against the established laws of his nature.

But for this anomaly of feeling surely I might die: the medicine of the alchymist would not be proof against fire — sword — and the strangling waters. I have gazed upon the blue depths of many a placid lake, and the tumultuous rushing of many a mighty river, and have said, peace inhabits those waters; yet I have turned my steps away, to live yet another day. I have asked myself, whether suicide would be a crime in one to whom thus only the portals of the other world could be opened. I have done all, except presenting myself as a soldier or duelist, an objection of destruction to my — no, not my fellow mortals, and therefore I have shrunk away. They are not my fellows. The inextinguishable power of life in my frame, and their ephemeral existence, places us wide as the poles asunder. I could not raise a hand against the meanest or the most powerful among them.

Thus have I lived on for many a year — alone, and weary of myself — desirous of death, yet never dying — a mortal immortal. Neither ambition nor avarice can enter my mind, and the ardent love that gnaws at my heart, never to be returned — never to find an equal on which to expend itself — lives there only to torment me.

This very day I conceived a design by which I may end all — without self-slaughter, without making another man a Cain — an expedition, which mortal frame can never survive, even endued with the youth and strength that inhabits mine. Thus I shall put my immortality to the test, and rest for ever — or return, the wonder and benefactor of the human species.

Before I go, a miserable vanity has caused me to pen these pages. I would not die, and leave no name behind. Three centuries have passed since I quaffed the fatal beverage; another year shall not elapse before, encountering gigantic dangers — warring with the powers of frost in their home — beset by famine, toil, and tempest — I yield this body, too tenacious a cage for a soul which thirsts for freedom, to the destructive elements of air and water; or, if I survive, my name shall be recorded as one of the most famous among the sons of men; and, my task achieved, I shall adopt more resolute means, and, by scattering and annihilating the atoms that compose my frame, set at liberty the life imprisoned within, and so cruelly prevented from soaring from this dim earth to a sphere more congenial to its immortal essence.

Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851)

The Mortal Immortal

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary

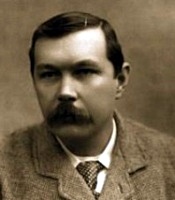

The Five Orange Pips

The Five Orange Pips

by Arthur Conan Doyle

When I glance over my notes and records of the Sherlock Holmes cases between the years ’82 and ’90, I am faced by so many which present strange and interesting features that it is no easy matter to know which to choose and which to leave. Some, however, have already gained publicity through the papers, and others have not offered a field for those peculiar qualities which my friend possessed in so high a degree, and which it is the object of these papers to illustrate. Some, too, have baffled his analytical skill, and would be, as narratives, beginnings without an ending, while others have been but partially cleared up, and have their explanations founded rather upon conjecture and surmise than on that absolute logical proof which was so dear to him. There is, however, one of these last which was so remarkable in its details and so startling in its results that I am tempted to give some account of it in spite of the fact that there are points in connection with it which never have been, and probably never will be, entirely cleared up.

The year ’87 furnished us with a long series of cases of greater or less interest, of which I retain the records. Among my headings under this one twelve months I find an account of the adventure of the Paradol Chamber, of the Amateur Mendicant Society, who held a luxurious club in the lower vault of a furniture warehouse, of the facts connected with the loss of the British bark Sophy Anderson, of the singular adventures of the Grice Patersons in the island of Uffa, and finally of the Camberwell poisoning case. In the latter, as may be remembered, Sherlock Holmes was able, by winding up the dead man’s watch, to prove that it had been wound up two hours before, and that therefore the deceased had gone to bed within that time — a deduction which was of the greatest importance in clearing up the case. All these I may sketch out at some future date, but none of them present such singular features as the strange train of circumstances which I have now taken up my pen to describe.

It was in the latter days of September, and the equinoctial gales had set in with exceptional violence. All day the wind had screamed and the rain had beaten against the windows, so that even here in the heart of great, hand-made London we were forced to raise our minds for the instant from the routine of life and to recognize the presence of those great elemental forces which shriek at mankind through the bars of his civilization, like untamed beasts in a cage. As evening drew in, the storm grew higher and louder, and the wind cried and sobbed like a child in the chimney. Sherlock Holmes sat moodily at one side of the fireplace cross-indexing his records of crime, while I at the other was deep in one of Clark Russell’s fine sea-stories until the howl of the gale from without seemed to blend with the text, and the splash of the rain to lengthen out into the long swash of the sea waves. My wife was on a visit to her mother’s, and for a few days I was a dweller once more in my old quarters at Baker Street.

“Why,” said I, glancing up at my companion, “that was surely the bell. Who could come to-night? Some friend of yours, perhaps?”

“Except yourself I have none,” he answered. “I do not encourage visitors.”

“A client, then?”

“If so, it is a serious case. Nothing less would bring a man out on such a day and at such an hour. But I take it that it is more likely to be some crony of the landlady’s.”

Sherlock Holmes was wrong in his conjecture, however, for there came a step in the passage and a tapping at the door. He stretched out his long arm to turn the lamp away from himself and towards the vacant chair upon which a newcomer must sit.

“Come in!” said he.

The man who entered was young, some two-and-twenty at the outside, well-groomed and trimly clad, with something of refinement and delicacy in his bearing. The streaming umbrella which he held in his hand, and his long shining waterproof told of the fierce weather through which he had come. He looked about him anxiously in the glare of the lamp, and I could see that his face was pale and his eyes heavy, like those of a man who is weighed down with some great anxiety.

“l owe you an apology,” he said, raising his golden pince-nez to his eyes. “I trust that I am not intruding. I fear that I have brought some traces of the storm and rain into your snug chamber.”

“Give me your coat and umbrella,” said Holmes. “They may rest here on the hook and will be dry presently. You have come up from the south-west, I see.”

“Yes, from Horsham.”

“That clay and chalk mixture which I see upon your toe caps is quite distinctive.”

“I have come for advice.”

“That is easily got.”

“And help.”

“That is not always so easy.”

“I have heard of you, Mr. Holmes. I heard from Major Prendergast how you saved him in the Tankerville Club scandal.”

“Ah, of course. He was wrongfully accused of cheating at cards.”

“He said that you could solve anything.”

“He said too much.”

“That you are never beaten.”

“I have been beaten four times – three times by men, and once by a woman.”

“But what is that compared with the number of your successes?”

“It is true that I have been generally successful.”

“Then you may be so with me.”

“I beg that you will draw your chair up to the fire and favour me with some details as to your case.”

“It is no ordinary one.”

“None of those which come to me are. I am the last court of appeal.”

“And yet I question, sir, whether, in all your experience, you have ever listened to a more mysterious and inexplicable chain of events than those which have happened in my own family.”

“You fill me with interest,” said Holmes. “Pray give us the essential facts from the commencement, and I can afterwards question you as to those details which seem to me to be most important.”

The young man pulled his chair up and pushed his wet feet out towards the blaze.

“My name,” said he, “is John Openshaw, but my own affairs have, as far as I can understand, little to do with this awful business. It is a hereditary matter; so in order to give you an idea of the facts, I must go back to the commencement of the affair.

“You must know that my grandfather had two sons — my uncle Elias and my father Joseph. My father had a small factory at Coventry, which he enlarged at the time of the invention of bicycling. He was a patentee of the Openshaw unbreakable tire, and his business met with such success that he was able to sell it and to retire upon a handsome competence.

“My uncle Elias emigrated to America when he was a young man and became a planter in Florida, where he was reported to have done very well. At the time of the war he fought in Jackson’s army, and afterwards under Hood, where he rose to be a colonel. When Lee laid down his arms my uncle returned to his plantation, where he remained for three or four years. About 1869 or 1870 he came back to Europe and took a small estate in Sussex, near Horsham. He had made a very considerable fortune in the States, and his reason for leaving them was his aversion to the negroes, and his dislike of the Republican policy in extending the franchise to them. He was a singular man, fierce and quick-tempered, very foul-mouthed when he was angry, and of a most retiring disposition. During all the years that he lived at Horsham, I doubt if ever he set foot in the town. He had a garden and two or three fields round his house, and there he would take his exercise, though very often for weeks on end he would never leave his room. He drank a great deal of brandy and smoked very heavily, but he would see no society and did not want any friends, not even his own brother.

“He didn’t mind me; in fact, he took a fancy to me, for at the time when he saw me first I was a youngster of twelve or so. This would be in the year 1878, after he had been eight or nine years in England. He begged my father to let me live with him and he was very kind to me in his way. When he was sober he used to be fond of playing backgammon and draughts with me, and he would make me his representative both with the servants and with the tradespeople, so that by the time that I was sixteen I was quite master of the house. I kept all the keys and could go where I liked and do what I liked, so long as I did not disturb him in his privacy. There was one singular exception, however, for he had a single room, a lumber-room up among the attics, which was invariably locked, and which he would never permit either me or anyone else to enter. With a boy’s curiosity I have peeped through the keyhole, but I was never able to see more than such a collection of old trunks and bundles as would be expected in such a room.

“One day — it was in March, 1883 — a letter with a foreign stamp lay upon the table in front of the colonel’s plate. It was not a common thing for him to receive letters, for his bills were all paid in ready money, and he had no friends of any sort. ‘From India!’ said he as he took it up, ‘Pondicherry postmark! What can this be?’ Opening it hurriedly, out there jumped five little dried orange pips, which pattered down upon his plate. I began to laugh at this, but the laugh was struck from my lips at the sight of his face. His lip had fallen, his eyes were protruding, his skin the colour of putty, and he glared at the envelope which he still held in his trembling hand, ‘K. K. K.!’ he shrieked, and then, ‘My God, my God, my sins have overtaken me!’

” ‘What is it, uncle?’ I cried.

” ‘Death,’ said he, and rising from the table he retired to his room, leaving me palpitating with horror. I took up the envelope and saw scrawled in red ink upon the inner flap, just above the gum, the letter K three times repeated. There was nothing else save the five dried pips. What could be the reason of his over-powering terror? I left the breakfast-table, and as I ascended the stair I met him coming down with an old rusty key, which must have belonged to the attic, in one hand, and a small brass box, like a cashbox, in the other.

” ‘They may do what they like, but I’ll checkmate them still,’ said he with an oath. ‘Tell Mary that I shall want a fire in my room to-day, and send down to Fordham, the Horsham lawyer.’

“I did as he ordered, and when the lawyer arrived I was asked to step up to the room. The fire was burning brightly, and in the grate there was a mass of black, fluffy ashes, as of burned paper, while the brass box stood open and empty beside it. As I glanced at the box I noticed, with a start, that upon the lid was printed the treble K which I had read in the morning upon the envelope.

” ‘I wish you, John,’ said my uncle, ‘to witness my will. I leave my estate, with all its advantages and all its disadvantages, to my brother, your father, whence it will, no doubt, descend to you. If you can enjoy it in peace, well and good! If you find you cannot, take my advice, my boy, and leave it to your deadliest enemy. I am sorry to give you such a two-edged thing, but I can’t say what turn things are going to take. Kindly sign the paper where Mr. Fordham shows you.’

“I signed the paper as directed, and the lawyer took it away with him. The singular incident made, as you may think, the deepest impression upon me, and I pondered over it and turned it every way in my mind without being able to make anything of it. Yet I could not shake off the vague feeling of dread which it left behind, though the sensation grew less keen as the weeks passed and nothing happened to disturb the usual routine of our lives. I could see a change in my uncle, however. He drank more than ever, and he was less inclined for any sort of society. Most of his time he would spend in his room, with the door locked upon the inside, but sometimes he would emerge in a sort of drunken frenzy and would burst out of the house and tear about the garden with a revolver in his hand, screaming out that he was afraid of no man, and that he was not to be cooped up, like a sheep in a pen, by man or devil. When these hot fits were over however, he would rush tumultuously in at the door and lock and bar it behind him, like a man who can brazen it out no longer against the terror which lies at the roots of his soul. At such times I have seen his face, even on a cold day, glisten with moisture, as though it were new raised from a basin.

“Well, to come to an end of the matter, Mr. Holmes, and not to abuse your patience, there came a night when he made one of those drunken sallies from which he never came back. We found him, when we went to search for him, face downward in a little green-scummed pool, which lay at the foot of the garden. There was no sign of any violence, and the water was but two feet deep, so that the jury, having regard to his known eccentricity, brought in a verdict of ‘suicide.’ But I, who knew how he winced from the very thought of death, had much ado to persuade myself that he had gone out of his way to meet it. The matter passed, however, and my father entered into possession of the estate, and of some 14,000 pounds, which lay to his credit at the bank.”

“One moment,” Holmes interposed, “your statement is, I foresee, one of the most remarkable to which I have ever listened. Let me have the date of the reception by your uncle of the letter, and the date of his supposed suicide.”

“The letter arrived on March 10, 1883. His death was seven weeks later, upon the night of May 2d.”

“Thank you. Pray proceed.”

“When my father took over the Horsham property, he, at my request, made a careful examination of the attic, which had been always locked up. We found the brass box there, although its contents had been destroyed. On the inside of the cover was a paper label, with the initials of K. K. K. repeated upon it, and ‘Letters, memoranda, receipts, and a register’ written beneath. These, we presume, indicated the nature of the papers which had been destroyed by Colonel Openshaw. For the rest, there was nothing of much importance in the attic save a great many scattered papers and note-books bearing upon my uncle’s life in America. Some of them were of the war time and showed that he had done his duty well and had borne the repute of a brave soldier. Others were of a date during the reconstruction of the Southern states, and were mostly concerned with politics, for he had evidently taken a strong part in opposing the carpet-bag politicians who had been sent down from the North.

“Well, it was the beginning of ’84 when my father came to live at Horsham, and all went as well as possible with us until the January of ’85. On the fourth day after the new year I heard my father give a sharp cry of surprise as we sat together at the breakfast-table. There he was, sitting with a newly opened envelope in one hand and five dried orange pips in the outstretched palm of the other one. He had always laughed at what he called my cock-and-bull story about the colonel, but he looked very scared and puzzled now that the same thing had come upon himself.

” ‘Why, what on earth does this mean, John?’ he stammered.

“My heart had turned to lead. ‘It is K. K. K.,’ said I.

“He looked inside the envelope. ‘So it is,’ he cried. ‘Here are the very letters. But what is this written above them?’

” ‘Put the papers on the sundial,’ I read, peeping over his shoulder.

” ‘What papers? What sundial?’ he asked.

” ‘The sundial in the garden. There is no other,’ said I; ‘but the papers must be those that are destroyed.’

” ‘Pooh!’ said he, gripping hard at his courage. ‘We are in a civilized land here, and we can’t have tomfoolery of this kind. Where does the thing come from?’

” ‘From Dundee,’ I answered, glancing at the postmark.

” ‘Some preposterous practical joke,’ said he. ‘What have I to do with sundials and papers? I shall take no notice of such nonsense.’

” ‘I should certainly speak to the police,’ I said.

” ‘And be laughed at for my pains. Nothing of the sort.’

” ‘Then let me do so?’

” ‘No, I forbid you. I won’t have a fuss made about such nonsense.’

“It was in vain to argue with him, for he was a very obstinate man. I went about, however, with a heart which was full of forebodings.

“On the third day after the coming of the letter my father went from home to visit an old friend of his, Major Freebody, who is in command of one of the forts upon Portsdown Hill. I was glad that he should go, for it seemed to me that he was farther from danger when he was away from home. In that, however, I was in error. Upon the second day of his absence I received a telegram from the major, imploring me to come at once. My father had fallen over one of the deep chalk-pits which abound in the neighbourhood, and was lying senseless, with a shattered skull. I hurried to him, but he passed away without having ever recovered his consciousness. He had, as it appears, been returning from Fareham in the twilight, and as the country was unknown to him, and the chalk-pit unfenced, the jury had no hesitation in bringing in a verdict of ‘death from accidental causes.’ Carefully as I examined every fact connected with his death, I was unable to find anything which could suggest the idea of murder. There were no signs of violence, no footmarks, no robbery, no record of strangers having been seen upon the roads. And yet I need not tell you that my mind was far from at ease, and that I was well-nigh certain that some foul plot had been woven round him.

“In this sinister way I came into my inheritance. You will ask me why I did not dispose of it? I answer, because I was well convinced that our troubles were in some way dependent upon an incident in my uncle’s life, and that the danger would be as pressing in one house as in another.

“It was in January, ’85, that my poor father met his end, and two years and eight months have elapsed since then. During that time I have lived happily at Horsham, and I had begun to hope that this curse had passed way from the family, and that it had ended with the last generation. I had begun to take comfort too soon, however; yesterday morning the blow fell in the very shape in which it had come upon my father.”

The young man took from his waistcoat a crumpled envelope, and turning to the table he shook out upon it five little dried orange pips.

“This is the envelope,” he continued. “The postmark is London — eastern division. Within are the very words which were upon my father’s last message: ‘K. K. K.’; and then ‘Put the papers on the sundial.’ “

“What have you done?” asked Holmes.

“Nothing.”

“Nothing?”

“To tell the truth” — he sank his face into his thin, white hands — “I have felt helpless. I have felt like one of those poor rabbits when the snake is writhing towards it. I seem to be in the grasp of some resistless, inexorable evil, which no foresight and no precautions can guard against.”

“Tut! tut!” cried Sherlock Holmes. “You must act, man, or you are lost. Nothing but energy can save you. This is no time for despair.”

“I have seen the police.”

“Ah!”

“But they listened to my story with a smile. I am convinced that the inspector has formed the opinion that the letters are all practical jokes, and that the deaths of my relations were really accidents, as the jury stated, and were not to be connected with the warnings.”

Holmes shook his clenched hands in the air. “Incredible imbecility!” he cried.

“They have, however, allowed me a policeman, who may remain in the house with me.”

“Has he come with you tonight?”

“No. His orders were to stay in the house.”

Again Holmes raved in the air.

“Why did you not come to me,” he cried, “and, above all, why did you not come at once?”

“I did not know. It was only today that I spoke to Major Prendergast about my troubles and was advised by him to come to you.”

“It is really two days since you had the letter. We should have acted before this. You have no further evidence, I suppose, than that which you have placed before us — no suggestive detail which might help us?”

“There is one thing,” said John Openshaw. He rummaged in his coat pocket, and, drawing out a piece of discoloured, blue-tinted paper, he laid it out upon the table. “I have some remembrance,” said he, “that on the day when my uncle burned the papers I observed that the small, unburned margins which lay amid the ashes were of this particular colour. I found this single sheet upon the floor of his room, and I am inclined to think that it may be one of the papers which has, perhaps, fluttered out from among the others, and in that way has escaped destruction. Beyond the mention of pips, I do not see that it helps us much. I think myself that it is a page from some private diary. The writing is undoubtedly my uncle’s.”

Holmes moved the lamp, and we both bent over the sheet of paper, which showed by its ragged edge that it had indeed been torn from a book. It was headed, “March, 1869,” and beneath were the following enigmatical notices:

4th. Hudson came. Same old platform.

7th. Set the pips on McCauley, Paramore, and John Swain, of St. Augustine.

9th. McCauley cleared.

10th. John Swain cleared.

12th. Visited Paramore. All well.

“Thank you!” said Holmes, folding up the paper and returning it to our visitor. “And now you must on no account lose another instant. We cannot spare time even to discuss what you have told me. You must get home instantly and act.”

“What shall I do?”

“There is but one thing to do. It must be done at once. You must put this piece of paper which you have shown us into the brass box which you have described. You must also put in a note to say that all the other papers were burned by your uncle, and that this is the only one which remains. You must assert that in such words as will carry conviction with them. Having done this, you must at once put the box out upon the sundial, as directed. Do you understand?”

“Entirely.”

“Do not think of revenge, or anything of the sort, at present. I think that we may gain that by means of the law; but we have our web to weave, while theirs is already woven. The first consideration is to remove the pressing danger which threatens you. The second is to clear up the mystery and to punish the guilty parties.”

“I thank you,” said the young man, rising and pulling on his overcoat. “You have given me fresh life and hope. I shall certainly do as you advise.”

“Do not lose an instant. And, above all, take care of yourself in the meanwhile, for I do not think that there can be a doubt that you are threatened by a very real and imminent danger. How do you go back?”

“By train from Waterloo.”

“It is not yet nine. The streets will be crowded, so l trust that you may be in safety. And yet you cannot guard yourself too closely.”

“I am armed.”

“That is well. To-morrow I shall set to work upon your case.”

“I shall see you at Horsham, then?”

“No, your secret lies in London. It is there that I shall seek it.”

“Then I shall call upon you in a day, or in two days, with news as to the box and the papers. I shall take your advice in every particular.” He shook hands with us and took his leave. Outside the wind still screamed and the rain splashed and pattered against the windows. This strange, wild story seemed to have come to us from amid the mad elements — blown in upon us like a sheet of sea-weed in a gale — and now to have been reabsorbed by them once more.

Sherlock Holmes sat for some time in silence, with his head sunk forward and his eyes bent upon the red glow of the fire. Then he lit his pipe, and leaning back in his chair he watched the blue smoke-rings as they chased each other up to the ceiling.

“I think, Watson,” he remarked at last, “that of all our cases we have had none more fantastic than this.”

“Save, perhaps, the Sign of Four.”

“Well, yes. Save, perhaps, that. And yet this John Openshaw seems to me to be walking amid even greater perils than did the Sholtos.”

“But have you,” I asked, “formed any definite conception as to what these perils are?”

“There can be no question as to their nature,” he answered.

“Then what are they? Who is this K. K. K., and why does he pursue this unhappy family?”

Sherlock Holmes closed his eyes and placed his elbows upon the arms of his chair, with his finger-tips together. “The ideal reasoner,” he remarked, “would, when he had once been shown a single fact in all its bearings, deduce from it not only all the chain of events which led up to it but also all the results which would follow from it. As Cuvier could correctly describe a whole animal by the contemplation of a single bone, so the observer who has thoroughly understood one link in a series of incidents should be able to accurately state all the other ones, both before and after. We have not yet grasped the results which the reason alone can attain to. Problems may be solved in the study which have baffled all those who have sought a solution by the aid of their senses. To carry the art, however, to its highest pitch, it is necessary that the reasoner should be able to utilize all the facts which have come to his knowledge; and this in itself implies, as you will readily see, a possession of all knowledge, which, even in these days of free education and encyclopaedias, is a somewhat rare accomplishment. It is not so impossible, however, that a man should possess all knowledge which is likely to be useful to him in his work, and this I have endeavoured in my case to do. If I remember rightly, you on one occasion, in the early days of our friendship, defined my limits in a very precise fashion.”

“Yes,” I answered, laughing. “It was a singular document. Philosophy, astronomy, and politics were marked at zero, I remember. Botany variable, geology profound as regards the mud-stains from any region within fifty miles of town, chemistry eccentric, anatomy unsystematic, sensational literature and crime records unique, violin-player, boxer, swordsman, lawyer, and self-poisoner by cocaine and tobacco. Those, I think, were the main points of my analysis.”

Holmes grinned at the last item. “Well,” he said, “I say now, as I said then, that a man should keep his little brain-attic stocked with all the furniture that he is likely to use, and the rest he can put away in the lumber-room of his library, where he can get it if he wants it. Now, for such a case as the one which has been submitted to us to-night, we need certainly to muster all our resources. Kindly hand me down the letter K of the American Encyclopaedia which stands upon the shelf beside you. Thank you. Now let us consider the situation and see what may be deduced from it. In the first place, we may start with a strong presumption that Colonel Openshaw had some very strong reason for leaving America. Men at his time of life do not change all their habits and exchange willingly the charming climate of Florida for the lonely life of an English provincial town. His extreme love of solitude in England suggests the idea that he was in fear of someone or something, so we may assume as a working hypothesis that it was fear of someone or something which drove him from America. As to what it was he feared, we can only deduce that by considering the formidable letters which were received by himself and his successors. Did you remark the postmarks of those letters?”

“The first was from Pondicherry, the second from Dundee, and the third from London.”

“From East London. What do you deduce from that?”

“They are all seaports. That the writer was on board of a ship.”

“Excellent. We have already a clue. There can be no doubt that the probability — the strong probability — is that the writer was on board of a ship. And now let us consider another point. In the case of Pondicherry, seven weeks elapsed between the threat and its fulfillment, in Dundee it was only some three or four days. Does that suggest anything?”

“A greater distance to travel.”

“But the letter had also a greater distance to come.”

“Then I do not see the point.”

“There is at least a presumption that the vessel in which the man or men are is a sailing-ship. It looks as if they always sent their singular warning or token before them when starting upon their mission. You see how quickly the deed followed the sign when it came from Dundee. If they had come from Pondicherry in a steamer they would have arrived almost as soon as their letter. But, as a matter of fact, seven weeks elapsed. I think that those seven weeks represented the difference between the mail-boat which brought the letter and the sailing vessel which brought the writer.”

“It is possible.”

“More than that. It is probable. And now you see the deadly urgency of this new case, and why I urged young Openshaw to caution. The blow has always fallen at the end of the time which it would take the senders to travel the distance. But this one comes from London, and therefore we cannot count upon delay.”

“Good God!” I cried. “What can it mean, this relentless persecution?”

“The papers which Openshaw carried are obviously of vital importance to the person or persons in the sailing-ship. I think that it is quite clear that there must be more than one of them. A single man could not have carried out two deaths in such a way as to deceive a coroner’s jury. There must have been several in it, and they must have been men of resource and determination. Their papers they mean to have, be the holder of them who it may. In this way you see K. K. K. ceases to be the initials of an individual and becomes the badge of a society.”

“But of what society?”

“Have you never –” said Sherlock Holmes, bending forward and sinking his voice –“have you never heard of the Ku Klux Klan?”

“I never have.”

Holmes turned over the leaves of the book upon his knee. “Here it is,” said he presently:

“Ku Klux Klan. A name derived from the fanciful resemblance to the sound produced by cocking a rifle. This terrible secret society was formed by some ex-Confederate soldiers in the Southern states after the Civil War, and it rapidly formed local branches in different parts of the country, notably in Tennessee, Louisiana, the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. Its power was used for political purposes, principally for the terrorizing of the negro voters and the murdering and driving from the country of those who were opposed to its views. Its outrages were usually preceded by a warning sent to the marked man in some fantastic but generally recognized shape — a sprig of oak-leaves in some parts, melon seeds or orange pips in others. On receiving this the victim might either openly abjure his former ways, or might fly from the country. If he braved the matter out, death would unfailingly come upon him, and usually in some strange and unforeseen manner. So perfect was the organization of the society, and so systematic its methods, that there is hardly a case upon record where any man succeeded in braving it with impunity, or in which any of its outrages were traced home to the perpetrators. For some years the organization flourished in spite of the efforts of the United States government and of the better classes of the community in the South. Eventually, in the year 1869, the movement rather suddenly collapsed, although there have been sporadic outbreaks of the same sort since that date.

“You will observe,” said Holmes, laying down the volume, “that the sudden breaking up of the society was coincident with the disappearance of Openshaw from America with their papers. It may well have been cause and effect. It is no wonder that he and his family have some of the more implacable spirits upon their track. You can understand that this register and diary may implicate some of the first men in the South, and that there may be many who will not sleep easy at night until it is recovered.”

“Then the page we have seen –“

“Is such as we might expect. It ran, if I remember right, ‘sent the pips to A, B, and C’ — that is, sent the society’s warning to them. Then there are successive entries that A and B cleared, or left the country, and finally that C was visited, with, I fear, a sinister result for C. Well, I think, Doctor, that we may let some light into this dark place, and I believe that the only chance young Openshaw has in the meantime is to do what I have told him. There is nothing more to be said or to be done to-night, so hand me over my violin and let us try to forget for half an hour the miserable weather and the still more miserable ways of our fellowmen.”

It had cleared in the morning, and the sun was shining with a subdued brightness through the dim veil which hangs over the great city. Sherlock Holmes was already at breakfast when I came down.

“You will excuse me for not waiting for you,” said he; “I have, I foresee, a very busy day before me in looking into this case of young Openshaw’s.”

“What steps will you take?” I asked.

“It will very much depend upon the results of my first inquiries. I may have to go down to Horsham, after all.”

“You will not go there first?”

“No, I shall commence with the City. Just ring the bell and the maid will bring up your coffee.”

As I waited, I lifted the unopened newspaper from the table and glanced my eye over it. It rested upon a heading which sent a chill to my heart.

“Holmes,” I cried, “you are too late.”

“Ah!” said he, laying down his cup, “I feared as much. How was it done?” He spoke calmly, but I could see that he was deeply moved.

“My eye caught the name of Openshaw, and the heading ‘Tragedy Near Waterloo Bridge.’ Here is the account:

“Between nine and ten last night Police-Constable Cook, of the H Division, on duty near Waterloo Bridge, heard a cry for help and a splash in the water. The night, however, was extremely dark and stormy, so that, in spite of the help of several passers-by, it was quite impossible to effect a rescue. The alarm, however, was given, and, by the aid of the water-police, the body was eventually recovered. It proved to be that of a young gentleman whose name, as it appears from an envelope which was found in his pocket, was John Openshaw, and whose residence is near Horsham. It is conjectured that he may have been hurrying down to catch the last train from Waterloo Station, and that in his haste and the extreme darkness he missed his path and walked over the edge of one of the small landing-places for river steamboats. The body exhibited no traces of violence, and there can be no doubt that the deceased had been the victim of an unfortunate accident, which should have the effect of calling the attention of the authorities to the condition of the riverside landing-stages.”

We sat in silence for some minutes, Holmes more depressed and shaken than I had ever seen him.

“That hurts my pride, Watson,” he said at last. “It is a petty feeling, no doubt, but it hurts my pride. It becomes a personal matter with me now, and, if God sends me health, I shall set my hand upon this gang. That he should come to me for help, and that I should send him away to his death –!” He sprang from his chair and paced about the room in uncontrollable agitation, with a flush upon his sallow cheeks and a nervous clasping and unclasping of his long thin hands.

“They must be cunning devils,” he exclaimed at last. “How could they have decoyed him down there? The Embankment is not on the direct line to the station. The bridge, no doubt, was too crowded, even on such a night, for their purpose. Well, Watson, we shall see who will win in the long run. I am going out now!”

“To the police?”

“No; I shall be my own police. When I have spun the web they may take the flies, but not before.”

All day I was engaged in my professional work, and it was late in the evening before I returned to Baker Street. Sherlock Holmes had not come back yet. It was nearly ten o’clock before he entered, looking pale and worn. He walked up to the sideboard, and tearing a piece from the loaf he devoured it voraciously, washing it down with a long draught of water.

“You are hungry,” I remarked.

“Starving. It had escaped my memory. I have had nothing since breakfast.”

“Nothing?”

“Not a bite. I had no time to think of it.”

“And how have you succeeded?”

“Well.”

“You have a clue?”

“I have them in the hollow of my hand. Young Openshaw shall not long remain unavenged. Why, Watson, let us put their own devilish trade-mark upon them. It is well thought of!”

“What do you mean?”

He took an orange from the cupboard, and tearing it to pieces he squeezed out the pips upon the table. Of these he took five and thrust them into an envelope. On the inside of the flap he wrote “S. H. for J. O.” Then he sealed it and addressed it to “Captain James Calhoun, Bark Lone Star, Savannah, Georgia.”

“That will await him when he enters port,” said he, chuckling. “It may give him a sleepless night. He will find it as sure a precursor of his fate as Openshaw did before him.”

“And who is this Captain Calhoun?”

“The leader of the gang. I shall have the others, but he first.”

“How did you trace it, then?”

He took a large sheet of paper from his pocket, all covered with dates and names.

“I have spent the whole day,” said he, “over Lloyd’s registers and files of the old papers, following the future career of every vessel which touched at Pondicherry in January and February in ’83. There were thirty-six ships of fair tonnage which were reported there during those months. Of these, one, the Lone Star, instantly attracted my attention, since, although it was reported as having cleared from London, the name is that which is given to one of the states of the Union.”

“Texas, I think.”

“I was not and am not sure which; but I knew that the ship must have an American origin.”

“What then?”

“I searched the Dundee records, and when I found that the bark Lone Star was there in January, ’85, my suspicion became a certainty. I then inquired as to the vessels which lay at present in the port of London.”

“Yes?”

“The Lone Star had arrived here last week. I went down to the Albert Dock and found that she had been taken down the river by the early tide this morning, homeward bound to Savannah. I wired to Gravesend and learned that she had passed some time ago, and as the wind is easterly I have no doubt that she is now past the Goodwins and not very far from the Isle of Wight.”

“What will you do, then?”