Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

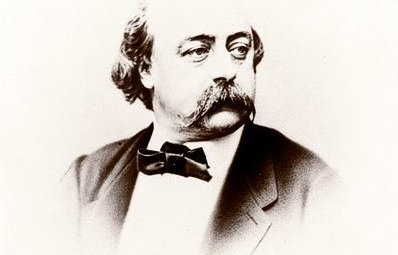

Gustave Flaubert

(1821-1880)

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (F)

F

FABRIQUE: Voisinage dangereux.

FACTURE: Toujours trop élevé.

FAÏENCE: Plus chic que la porcelaine.

FAISAN: Très chic dans un dîner.

FAISCEAUX: A former, est le comble de la difficulté dans la garde nationale.

FANFARE: Toujours joyeuse.

FARCE: Il faut en faire lorsqu’on est en partie de campagne avec des dames.

FARD: Abîme la peau.

FATALITÉ: Mot exclusivement romantique. Homme fatal se dit de celui qui a le mauvais oeil.

FAUBOURGS: Terribles dans les révolutions.

FAUTE: «C’est pire qu’un crime, c’est une faute.» (Talleyrand.) «Il n’y a plus une seule faute à commettre.» (Thiers.) Ces deux phrases doivent être articulées avec profondeur.

FAUX-MONNAYEURS: Travaillent toujours dans les souterrains.

FÉLICITATIONS: Toujours sincères, empressées, cordiales, etc.

FÉLICITÉ: Toujours parfaite. Votre bonne se nomme Félicité, alors elle est parfaite.

FEMELLE: A n’employer qu’en parlant des animaux. Contrairement à ce qui existe dans l’espèce humaine, les femelles des animaux sont moins belles que les mâles. Ex.: faisan, coq, lion, etc.

FEMME: Personne du sexe. Une des côtes d’Adam. Na dites pas: «ma femme» , mais «mon épouse» , ou mieux encore, «ma moitié».

FEMMES DE CHAMBRE: Plus jolies que leur maîtresses. Connaissent tous leurs secrets et les trahissent. Toujours déshonorées par le fils de la maison.

FÉODALITÉ: N’en avoir aucune idée précise mais tonner contre.

FERME (adjectif): Toujours suivi de «comme un roc»

FERME (subst.): Lorsqu’on visite une ferme, on ne doit y manger que du pain bis et ne boire que du lait. Si on ajoute des oeufs, s’écrier: «Dieu! comme ils sont frais! Il n’y a pas de danger pour qu’on en trouve de comme ça à la ville.»

FERMÉ: Toujours précédé de hermétiquement.

FERMIER: Toujours lui dire: Maître un tel. Les fermiers sont tous à leur aise.

FEU (subst.): Purifie tout. Quand on entend crier «au feu!» on doit commencer par perdre la tête.

FEU (adj.): Feu mon père, et on soulève son chapeau.

FEUILLE DE VIGNE: Emblème de la virilité dans l’art de la sculpture.

FEUILLETONS: Cause de démoralisation. Se disputer sur le dénouement probable. Ecrire à l’auteur pour lui fournir des idées.

Fureur quand on y trouve un nom pareil au sien.

FIDÈLE: Inséparable d’ami et de chien. Ne pas manquer de citer les deux vers: Oui puisque je retrouve un ami si fidèle, Ma fortune, etc.

FIÈVRE: Preuve de la force du sang. Est causée par les prunes, le melon, le soleil d’avril, etc.

FIGARO (Le Mariage de): Encore une des causes de la Révolution!

FIGURE: Une figure agréable est le plus sûr des passeports.

FLAGRANT DÉLIT: Prononcer flagrante delicto. Ne s’emploie que pour les cas d’adultère.

FLAMANT: Oiseau ainsi nommé parce qu’il vient des Flandres.

FLATTEUR: Ne jamais manquer la citation: Détestables flatteurs, présent le plus funeste – Que puisse faire aux rois la colère céleste! ou bien: Apprenez que tout flatteur – Vit aux dépens de celui qui l’écoute.

FLEGME: Bon genre, et puis ça donne l’air anglais. Toujours suivi de imperturbable.

FOETUS: Toute pièce anatomique conservée dans l’esprit de vin.

FOLLICULAIRES: Les journalistes. Quand on ajoute de bas étage, c’est le comble du mépris.

FONCTIONNAIRE: Inspire le respect quelle que soit la fonction qu’il remplisse.

FONDEMENT: Toutes les nouvelles en manquent.

FONDS SECRETS: Sommes incalculables avec lesquelles les ministres achètent les consciences. S’indigner contre.

FORCATS: Ont toujours une figure patibulaire. Tous très adroits de leurs mains. Au bagne, il y a des hommes de génie.

FORCE: Toujours herculéenne. La force prime le droit (Bismarck).

FORNARINA: C’était une belle femme; inutile d’en savoir plus long.

FORT: Comme un Turc, un boeuf, un cheval, comme Hercule. Cet homme doit être fort, il est tout de nerfs.

FORTUNE: Audaces fortuna juvat. Ils sont heureux les riches, ils ont de la fortune. Quand on vous parle d’une grande fortune, ne pas manquer de dire: «Oui, mais est-elle bien sûre?»

FOSSETTES: On doit toujours dire à une jolie fille qu’elle a des amours nichés dans ses fossettes.

FOSSILES: Preuve du déluge. Plaisanterie de bon goût, en parlant d’un académicien.

FOUDRES du Vatican: En rire.

FOULARD: Il est «comme il faut» de se moucher dedans.

FOULE: A toujours de bons instincts. Turba ruit ou ruunt. La vile multitude (Thiers.) Le peuple saint en foule inondait les portiques… , etc.

FOURCHETTE: Doit toujours être en argent, c’est moins dangereux. On doit s’en servir avec la main gauche, c’est plus commode et plus distingué.

FOURMIS: Bel exemple à citer devant un dissipateur. Ont donné l’idée des caisses d’épargne.

FOURRURE: Signe de richesse.

FOUTRE: N’employer de mot que pour jurer, et encore! (v. Docteur).

FRANÇAIS: Le premier peuple de l’univers. «Il n’y a qu’un Français de plus» , a dit le comte d’Artois. Ah! qu’on est fier d’être Français, – Quand on regarde la colonne!

FRANC-MACONNERIE: Encore une des causes de la Révolution! Les épreuves de l’initiation sont terribles. Cause de dispute dans les ménages. Mal vue des ecclésiastiques. Quel peut bien être son secret?

FRANCS-TIREURS: Plus terribles que l’ennemi.

FRAUDER: Frauder l’octroi n’est pas tromper, c’est une preuve d’esprit et d’indépendance politique.

FRESQUE: On n’en fait plus.

FRICASSÉE: Ne se fait bien qu’à la campagne.

FRISER, FRISURE: Ne convient pas à un homme.

FROID: Plus sain que la chaleur.

FROMAGE: Citer l’aphorisme de Brillat-Savarin: «Un dessert sans fromage est une belle à qui il manque un oeil.»

FRONT: Large et chauve, signe de génie ou d’aplomb.

FRONTISPICE: Les grands hommes font bien dessus.

FRUSTE: Tout ce qui antique est fruste, et tout ce qui est fruste

est antique. Bien se le rappeler quand on achète des antiquités.

FUGUE: On ignore en quoi cela consiste, mais il faut affirmer que c’est fort difficile et très ennuyeux.

FULMINER: Joli verbe.

FURIE FRANÇAISE: Toujours prononcer furia francese.

FURONCLE: V. boutons.

FUSIL: Toujours en avoir un à la campagne.

FUSILLADE: Seule manière de faire taire les Parisiens.

FUSILLER: Plus noble que guillotiner. Joie de l’individu à qui on accorde cette faveur.

FUSION des branches royales: L’espérer toujours.

Gustave Flaubert

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (F)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD VII

NAAR DE LICHTSTAD KORK. LANGS HET WOUD VAN TUBBS. TERUG OVER DE BRUG VAN KORK, OVER TEPPLE, GRETZ, WRAK, BORZ, DE BRUG BIJ BORZ EN BOEROE

Na het eten ging Cherubijn op bed liggen. De marmot sliep nog steeds.

Ik ging op stap. Ik liep in de richting van Kork, langs het Woud van Tubbs. Dat was een akelig woud als je er ‘s nachts door liep. Overdag was het mooi. Niemand die je dan stoorde.

Ik wilde rust. Ik was van plan te oefenen in het mierrijden. Ik vond een mooi holletje. Mieren van een grote soort. Met lange poten. Met dit soort mieren kreeg ik de kans mijn eigen record te verbeteren. Twintig mieren over een afstand van dertig centimeter te berijden en ze dan te doden. Hoewel dit record al zeer scherp stond met het getal negentien.

Plotseling zag ik een vreemde man door het woud lopen. Hij bewoog zich eigenaardig voort. Tikte steeds de bomen aan, alsof hij in zijn eentje krijgertje speelde. Dat kon. Hij zag me wel, maar lette toch niet op me. Dat was vreemd voor een man. Meestal schamen grote mensen zich voor kinderen als ze betrapt worden bij het spelen. Hij liep met ontbloot bovenlijf en hij had zich ingesmeerd met verf. Ik dacht dat hij een rol repeteerde voor een toneelstuk.

Toen hij schijnbaar genoeg gespeeld had, kwam hij naar me toe en gaf me een hand.

‘Hallo,’ zei hij, ‘ik ben het spook van de Lüne-heide.’

‘Hallo,’ zei ik, ‘ik woon bij Cherubijn. Nu wil ik spelen.’

‘Ik zal kijken hoe je speelt,’ zei het spook.

Ik speelde. Terwijl het spook toekeek, verbeterde ik mijn record met twee stuks. Het spook klapte in de handen. Dat gaf waarde aan de prestatie.

Het spook vroeg of ik even op hem wilde wachten. Hij moest zich verkleden. We zouden samen met de auto naar de Lichtstad Kork rijden.

Het was niet mijn bedoeling naar Kork te gaan. Maar ik zat graag in een auto. Het spook veranderde in een goed geklede, grijzende heer. Aan de rand van het woud stond zijn auto. Ik geloofde niet meer in het spook. De tegenwoordige tijd is de vloek voor een spook. Dat zei ik hem ook. De man was daar echter niet van overtuigd. Volgens hem was het spook-zijn het in stand houden van een traditie. Bovendien was het spookspelen, af en toe, een aangename bezigheid voor hem.

Hij dacht dat ik voor in de auto ging zitten. Ik gaf de voorkeur aan de achterbank. Zo kon ik hem blijven zien. Je wist het nooit met een spook, ook al was het een schijnspook.

We reden langs het Woud van Tubbs tot aan de rivier het Lange Rak, sloegen vóór de brug de weg in naar de Lichtstad Kork. In Kork was het, zoals gewoonlijk, druk. De mensen weken achteruit toen ze de auto zagen. Het bleek dat het spook belangrijk was in de Lichtstad Kork.

‘Je mag niet meer ‘spook’ zeggen,’ zei het spook. ‘Ik heet meneer Weber. Ik ben de burgemeester van de Lichtstad Kork. En ik ben senator.’

‘Dat zijn eigenaardige bezigheden voor een spook,’ meende ik. Daar bleek hij het mee eens te zijn. Die functies had hij echter voor de kost. Het spook-zijn was ‘roeping’. Het was de eerste keer dat ik het woord ‘roeping’ hoorde. Ik wilde graag van hem horen wat dat betekende. Hij bleek het zelf niet te weten. Hij meende dat het iets was dat iemand in het bloed zat.

Zijn huis was hoog. Je zou er twee huizen van kunnen maken, dan had je nog twee ruime huizen. We kwamen in de burgemeesterskamer, een grote salon met tijgervellen op de vloer. Het leek of ze over het parket zwommen. Was de burgemeester ooit in Afrika op jacht geweest? De muren hingen vol schilderijen. Als ik me niet vergis was het vroeg werk van de een of andere duivelskop.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

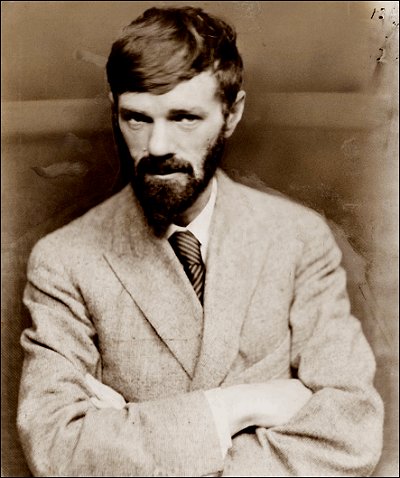

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Piano

Softly, in the dusk, a woman is singing to me;

Taking me back down the vista of years, till I see

A child sitting under the piano, in the boom of the tingling strings

And pressing the small, poised feet of a mother who smiles as she sings.

In spite of myself, the insidious mastery of song

Betrays me back, till the heart of me weeps to belong

To the old Sunday evenings at home, with winter outside

And hymns in the cosy parlour, the tinkling piano our guide.

So now it is vain for the singer to burst into clamour

With the great black piano appassionato. The glamour

Of childish days is upon me, my manhood is cast

Down in the flood of remembrance, I weep like a child for the past.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Joop Oversteegen

(Amsterdam 1900 – Eindhoven 1994)

‘Ome Joop’ werd Oversteegen genoemd door veel dichters. Hij stond altijd voor hen en kunstenaars in het algemeen klaar. Toen hij in 1962 het initiatief namen tot de Schrijvers Associatie Opwenteling ging dat ten koste van zijn eigen spaargeld.

Oversteegen nam het initiatief omdat de Brabantse dichters landelijk nauwelijks tegen het ‘poëtisch geweld’ van de dichters en schrijvers uit de randstad op konden. Met name jonge dichters hadden hier geen schijn van kans. En poëzie was juist van belang voor de ontwikkeling van de vrij denkende mens! Stad en land werd door hem afgelopen om contacten te leggen. De resultaten waren er naar. Uiteindelijk zouden heel wat later bekend geworden dichters en schrijvers bij de Eindhovense Schrijvers Associatie Opwenteling debuteren. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan Frans Kuijpers, Maria van der Steen, Hans Vlek, Silva Ley en Hans van de Waarsenburg. Maar ook de voor de tijd van Opwenteling landelijk bekend staande dichter Frans Babylon werd bij Opwenteling gepubliceerd. In totaal zagen zeker zo’n zeshonderd dichters bij Opwenteling hun poëzie in bundelvorm verschijnen. Allemaal gerealiseerd door vrijwilligers of die in de redacties functioneerden, bij de PR of er voor zorgden dat het secretariaat functioneerden.

De Schrijvers Associatie Opwenteling had een ideaal en groeide uit tot een landelijke en in België bekende debuutuitgeverij van bloemlezingen en persoonlijke dichtbundels. En dat niet alleen, hoorspelen, korte verhalen kregen eveneens hun plaats. In de loop der tijd kende ‘Opwenteling’ verschillende voorzitters. Allereerst Oversteegen zelf, die naast de dichtbundels eveneens het literair tijdschrift ‘Manifest’ publiceerde, Ton Veugen die de bekende reeks ‘Naar Morgen’ het licht deed zien. Riet van Gent die de fakkel van hem overnam. Wim van Til, de huidige directeur van het Studie en Documentatiecentrum ‘Poëzie Centrum Nederland’ in Bredevoort en schrijver van diverse dichtbundels zowel bij en buiten Opwenteling. Will van Sebille die na haar voorzitterschap bij Opwenteling actief was als begeleidster van jonge dichters wat leidde tot de bundel ‘Re_cyclus’, de schrijfgroep ‘Het schrijfsterscollectie Eindhoven’ en een dichtersgroep uit Delft. Zelf bleef ze bezig als dichter, publiceerde een dichtbundel en leverde bijdragen aan verschillende bloemlezingen. Als uitgever bij De Witte Uitgeverij (tussen 2007 en 20012) zette zij de reeks ‘Witte Voeten’ op, waarin ook weer een aantal opwenteling dichters verschijnen.

Latere voorzitters zijn Bernard Kessels en Willem Fonteijn. De dichtbundel ‘’ Dat ik je dan vastleg’ van de Eindhovenaar Chris van Lenteren en Jan Holman onder de redactie van Jack Tinnemans is de laatste uitgegeven bundel van de Stichting Schrijvers Associatie Opwenteling.

Onlangs maakte Opwenteling een doorstart. Hoewel niet op dezelfde leest geschoeid als zijn illustere voorganger. Daarover meer tijdens het literair Podium ‘Joop Oversteegen en Opwenteling op 28 oktober a.s.

De Werkgroep ‘Boekenkast’ III. Organiseerde eerder een soortgelijk podium over Frans Babylon en Lodewijk van Woensel (Louis Vrijdag). Doel: Het onder de aandacht brengen van overleden dichters die in de ontwikkeling van de poëzie in Eindhoven en regio van belang zijn geweest. De werkgroep bestaat uit: Willem Adelaar (dichter), Pierre Maréchal (schrijver/dichter) en Peter Thoben (Cultuur- en kunsthistoricus).

De Popband Beez. Over de bekende verrassende Eindhovense Band Beez valt veel te schrijven. Tijdens het vorige literaire programma van De Werkgroep Boekenkast brachten zij indrukwekkende muziek aan de hand van gedichten van Lodewijk van Woensel (Louis Vrijdag). Deze keer brengen zij muziek en zang ten gehoor aan de hand van gedichten van Joop Oversteegen. Nadere informatie: www. beezbeez.nl

De bekende blues zanger en gitarist Ernest van Aaken ontvangt met zijn muziek de gasten van deze middag. Van Aaken is onder andere bekend van zijn deelname aan K& B Literair, NulVeertig©, Poëtement en momenteel ‘Eindhoven uit de kunst’.

Groendomein Wasven. Bestaat uit: Gasterij in ’t Ven, Tussen de Molens en De Wasvenboerderij met een groene omgeving waarin het niet alleen goed vertoeven is maar waar mens, natuur en milieu belangrijk zijn. In dit kader worden er educatie-avonden gehouden. Om kennis te maken met het groendomein is het raadzaam om vroeger te komen en eens door het gebied te wandelen. De Wasvenboerderij is geopend van 10 – tot 22. Uur. Gasterij open van Nadere informatie: www.wasven.nl

Literair Podium over Joop Oversteegen en Opwenteling

Waar: Groendomein Wasven, Celebeslaan 30, 5641 AG Eindhoven (stadsdeel Tongelre).

Wanneer: Zondag 28 oktober 2012

Tijd: 14.00 uur- 17.00 uur

Parkeren in de omliggende omgeving nabij bij ’t Hofke bijvoorbeeld

Openbaar vervoer: Bushalte ‘Hofke nabij het oude raadhuis van Tongelre. Bus 55 vanaf Eindhoven Station naar ’t Hofke. Let op de zondagtijden!

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Babylon, Frans, Brabantia Nostra, Waarsenburg, Hans van de

Gustave Flaubert

(1821-1880)

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (E)

E

EAU: L’eau de Paris donne des coliques. L’eau de mer soutient pour nager. L’eau de Cologne sent bon.

ÉBÉNISTE: Ouvrier qui travaille surtout l’acajou.

ÉCHAFAUD: S’arranger quand on y monte pour prononcer quelques mots éloquents avant de mourir.

ÉCHARPE: Poétique.

ÉCHECS (jeu des): Image de la tactique militaire. Tous les grands capitaines y étaient forts. Trop sérieux pour un jeu, trop futile pour une science.

ÉCHO: Citer ceux du Panthéon et du pont de Neuilly.

ÉCLECTISME: Tonner contre comme étant une philosophie immorale.

ÉCOLES: Polytechnique, rêve de toutes les mères (vieux). Terreur du bourgeois dans les émeutes quand il apprend que ‘Ecole Polytechnique sympathise avec les ouvriers (vieux). Dire simplement «l’Ecole» fait accroire qu’on y a été. A Saint-Cyr: jeunes gens nobles. A l’Ecole de Médecine: tous exaltés. A l’Ecole de Droit: jeunes gens de bonne famille.

ÉCONOMIE: Toujours précédé de «ordre» . Mène à la fortune. Citer l’anecdote de Laffitte ramassant une épingle dans la cour du banquier Perrégaux.

ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE: Science sans entrailles.

ÉCREVISSE: Marche à reculons. Toujours appeler les réactionnaires des écrevisses.

ÉCRIRE: Currente calamo, c’est l’excuse pour les fautes de style ou d’orthographe.

ÉCRIT, BIEN ÉCRIT: Mots de portier, pour désigner les romans-feuilletons qui les amusent.

ÉCRITURE: Une belle écriture mène à tout. Indéchiffrable: signe de science. Ex.: les ordonnances des médecins.

ÉCUME DE MER: Se trouve dans la terre. On en fait des pipes.

ÉDILES: Tonner contre à propos du pavage des rues. «A quoi songent nos édiles?»

ÉGOÏSME: Se plaindre de celui des autres et ne pas s’apercevoir du sien.

ÉLÉPHANTS: Se distinguent par leur mémoire, et adorent le soleil.

ÉMAIL: Le secret en est perdu.

EMBONPOINT: Signe de richesse et de fainéantise.

ÉMIGRÉS: Gagnaient leur vie à donner des leçons de guitare et à faire la salade.

ÉMIR: Ne se dit qu’en parlant d’Abd-el-Kader.

EMPIRE: «L’Empire c’est la paix.» (Napoléon III.)

ENCEINTE: Fait bien dans les discours officiels: «Messieurs, dans cette enceinte…»

ENCRIER: Se donne en cadeau à un médecin.

ENCYCLOPÉDIE: En rire de pitié, comme étant un ouvrage rococo, et même tonner contre.

ENFANTS: Affecter pour eux une tendresse lyrique, quand il y a du monde.

ENGELURE: Signe de santé: vient de s’être chauffé quand on avait froid.

ENTERREMENT: A propos du défunt: «Et dire que je dînais avec lui il y a huit jours!» S’appelle obsèques quand il s’agit d’un général, enfouissement quand c’est celui d’un philosophe.

ENTHOUSIASME: Ne peut être provoqué que par le retour des cendres de l’Empereur. Toujours impossible à décrire, et pendant deux colonnes le journal ne parle que de ça.

ENTRACTE: Toujours trop long.

ENVERGURE: Se disputer sur la prononciation du mot.

ÉPACTE, NOMBRE D’OR, LETTRE DOMINICALE: Sur les calendriers, on ne sait pas ce que c’est.

ÉPARGNE (Caisse d’): Occasion de vol pour les domestiques.

ÉPÉE: On ne connaît que celle de Damoclès. Regretter le temps où on en portait. «Brave comme une épée.» Quelquefois elle n’a jamais servi.

ÉPÉRONS: Font bien à une paire de bottes.

ÉPICURE: Le mépriser.

ÉPINARDS: Sont le balai de l’estomac. Ne jamais rater la phrase célèbre de Prudhomme: «Je ne les aime pas, j’en suis bien aise, car si je les aimais, j’en mangerai et je ne puis pas les souffrir.» (Il y en a qui trouveront cela parfaitement logique et qui ne riront pas).

ÉPOQUE (la nôtre): Tonner contre elle. Se plaindre de ce qu’elle n’est pas poétique. L’appeler époque de transition, de décadence.

ÉPUISEMENT: Toujours prématuré.

ÉQUITATION: Bon exercice pour faire maigrir. Ex.: tous les soldats de cavalerie sont maigres. Bon exercice pour engraisser. Ex.: tous les officiers de cavalerie ont un gros ventre. «Il monte à cheval comme un vrai centaure.»

ÈRE (des révolutions): Toujours ouverte puisque chaque nouveau gouvernement promet de la fermer.

ÉRECTION: Ne se dit qu’en parlant des monuments.

ÉRUDITION: La mépriser comme étant la marque d’un esprit étroit.

ESCRIME: Les maîtres d’escrime savent des bottes secrètes.

ESCROC: Toujours du grand monde (v. espion).

ESPION: Toujours du grand monde (v. escroc).

ESPLANADE: Ne se voit qu’aux Invalides.

ESPRIT: Toujours suivi d’étincelant. Court les rues. Les beaux esprits se rencontrent.

ESTOMAC: Toutes les maladies viennent de l’estomac.

ÉTAGÈRE: Indispensable chez une jolie femme.

ÉTALON: Toujours vigoureux. Une femme doit ignorer la différence qu’il y a entre un étalon et un cheval.

ÉTÉ: Toujours exceptionnel (v. hiver).

ÉTERNUEMENT: Après qu’on a dit: «Dieu vous bénisse» , engager une discussion sur l’origine de cet usage.

ÉTERNUER: C’est une raillerie spirituelle de dire: le russe et le polonais ne se parlent pas, ça s’éternue.

ÉTOILE: Chacun a la sienne, comme l’Empereur.

ÉTRANGER: Engouement pour tout ce qui vient de l’étranger, preuve de l’esprit libéral. Dénigrement de tout ce qui n’est pas français, preuve de patriotisme.

ÉTRENNES: S’indigner contre.

ÉTRUSQUE: Tous les vases anciens sont étrusques.

ÉTUDIANT: Portent tous des bérets rouges, des pantalons à la hussarde, fumant la pipe dans la rue et n’étudie pas.

ÉTYMOLOGIE: Rien de plus facile à trouver avec le latin et un peu de réflexion.

EUNUQUE: N’a jamais d’enfants… Fulminer contre les castrats de la chapelle Sixtine.

ÉVACUATIONS: Les évacuations sont souvent copieuses et toujours de mauvaise nature.

ÉVANGILES: Livres divins, sublimes, etc.

ÉVIDENCE: Vous aveugle, quand elle ne crève pas les yeux.

EXASPÉRATION: Constamment à son comble.

EXCEPTION: Dites qu’elle confirme la règle. Ne vous risquez pas à expliquer comment.

EXÉCUTIONS CAPITALES: Se plaindre des femmes qui vont les voir.

EXERCICE: Préserve de toutes les maladies: toujours conseiller d’en faire.

EXPIRER: Ne se conjugue qu’à propos des abonnements de journaux.

EXPOSITION: Sujet de délire du XIXe siècle.

EXTINCTION: Ne s’emploie qu’avec paupérisme.

EXTIRPER: Ce verbe ne s’emploie que pour les hérésies et les cors aux pieds.

Gustave Flaubert

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (E)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

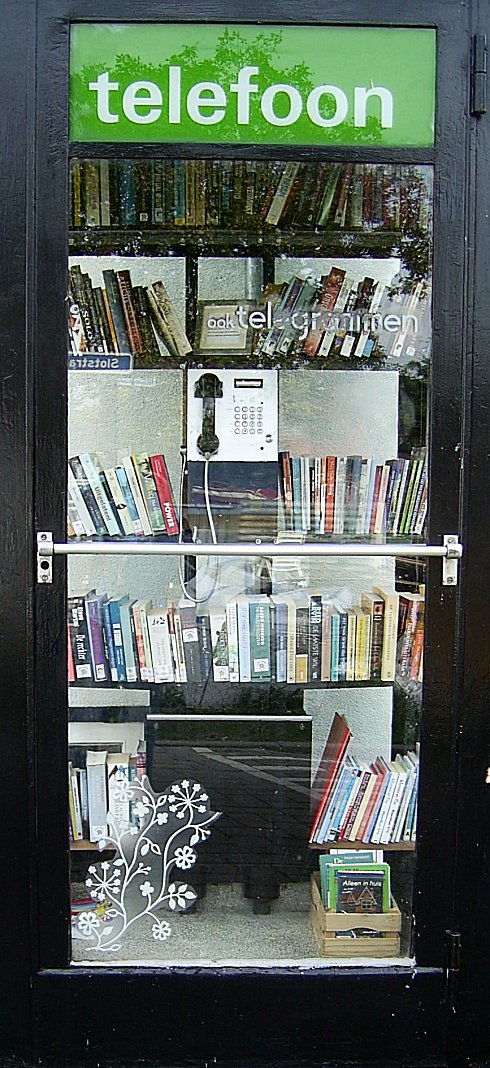

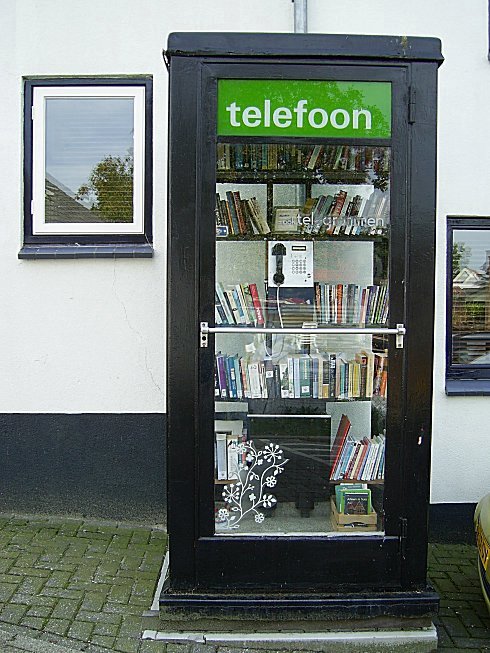

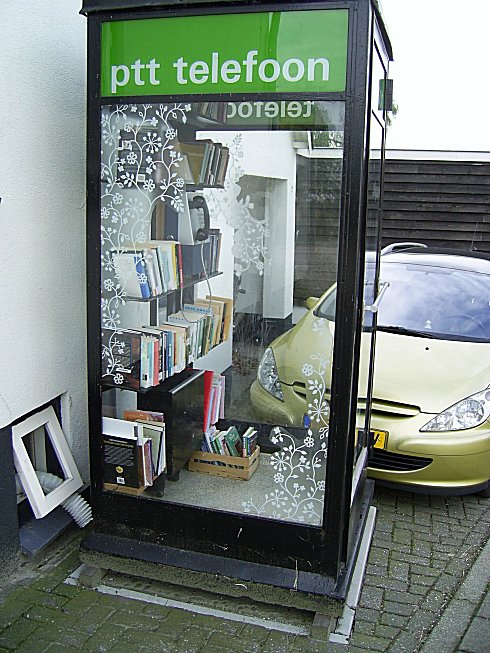

Gratis ruilbibliotheek van Jordi en Michelle de Groot

in een telefooncel

hoek van de Havendijk en Slotstraat te Beesd.

photo fleurdumal

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Guerilla Libraries

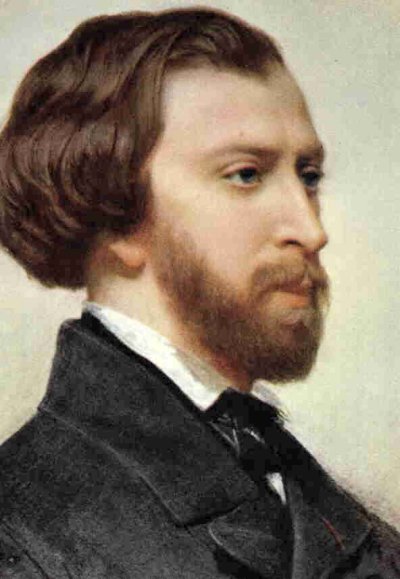

George Sand

(1804-1876)

Lettre envoyée par Aurore Dupin

dite George SAND

à Alfred de MUSSET

Je suis très émue de vous dire que j’ai

bien compris l’autre soir que vous aviez

toujours une envie folle de me faire

danser. Je garde le souvenir de votre

baiser et je voudrais bien que ce soit

là une preuve que je puisse être aimée

par vous. Je suis prête à vous montrer mon

affection toute désintéressée et sans cal-

cul, et si vous voulez me voir aussi

vous dévoiler sans artifice mon âme

toute nue, venez me faire une visite.

Nous causerons en amis, franchement.

Je vous prouverai que je suis la femme

sincère, capable de vous offrir l’affection

la plus profonde comme la plus étroite

amitié, en un mot la meilleure preuve

que vous puissiez rêver, puisque votre

âme est libre. Pensez que la solitude où j’ha-

bite est bien longue, bien dure et souvent

difficile. Ainsi en y songeant j’ai l’âme

grosse. Accourez donc vite et venez me la

faire oublier par l’amour où je veux me

mettre

George Sand (1835)

NB : A vous de découvrir l’érotisme caché.

Relisez-la en sautant les lignes paires

La réponse d’Alfred de Musset

Quand je mets à vos pieds un éternel hommage,

Voulez-vous qu’un instant je change de visage ?

Vous avez capturé les sentiments d’un coeur

Que pour vous adorer forma le créateur.

Je vous chéris, amour, et ma plume en délire

Couche sur le papier ce que je n’ose dire.

Avec soin de mes vers lisez les premiers mots,

Vous saurez quel remède apporter à mes maux.

Alfred de Musset

La réponse de George Sand

Cette insigne faveur que votre coeur réclame

Nuit à ma renommée et répugne à mon âme.

George Sand poetry & prose

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, George Sand, Musset, Alfred de

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (31)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

4

The villa.

Was this it? Is it possible that this was it?

And yet, there was nothing altered about it, or very little. Only that gate, a little higher, that pair of pillars, a little higher, replacing the little pillars of the old days, from one of which Grandfather Carlo had had the marble tablet with his name on it torn down.

But could this new gate have changed so completely the whole appearance of the old villa.

I saw that it was the same house, and it seemed to me impossible that it could be; I saw that it had remained much the same; why then did it appear a different house?

What a tragedy! The memory that seeks to live again, and cannot find its way among places that seem changed, that seem different, because our sentiments have changed, our sentiments are different. And yet I imagined that I had come hurrying to the villa with the sentiments of those days, the heart of long ago!

There it is. Knowing quite well that places have no other life, no other reality than that which we bestow on them, I saw myself obliged to admit with dismay, with infinite regret: “How I have changed!” The reality now is this. Something different.

I rang the bell. A different sound. But now I no longer knew whether this were due to some change in myself or to there being a different bell. How depressing!

There appeared an old gardener, without a coat, his shirt sleeves rolled up to the elbows, with a watering-can in his hand and a brimless hat perched on the crown of his head like a priest’s biretta.

“Donna Rosa Mirelli?”

“Who?”

“Is she dead?”

“Who do you mean?”

“Donna Rosa….”

“Ah, you want to know if she’s dead? How should I know?”

“She doesn’t live here any longer?”

“I don’t know what Donna Rosa you’re talking about. She doesn’t live here. It’s Pèrsico lives here, Don Filippo, the Cavaliere.”

“Has he a wife? Donna Duccella?”

“No, Sir. He’s a widower. He lives in town.”

“Then there’s no one living here?”

“There’s myself here, Nicola Tavuso, the gardener.”

The flowers in the borders on either side of the path from the gate to the house, red, yellow, white, hung motionless like discs of enamel in the limpid, silent air, dripping still from their recent bath. Flowers born yesterday, but upon those old borders. I looked at them: they disconcerted me; they said that it really was Tavuso who was living there now, as far as they were concerned, that he watered them well every morning, and that they were grateful to him for it: fresh, scentless, smiling with all those drops of water.

Fortunately, there appeared on the scene an old peasant woman, all breast and belly and hips, enormous under a big basket of greenstuff, with one eye shut, imprisoned beneath its swollen red lid, and the other keenly alert, clear, sky-blue, glazed with tears.

“Donna Rosa? Eh, the old mistress…. Many’s the long year since she left here…. Alive, yes, Sir, why not, poor soul? An old woman now… with the grandchild, yes, Sir, … Donna Duccella, yes, Sir…. Good folk! All for God…. No use for this world, or anything. … The house here they sold, yes, Sir, years ago, to Don Filippo the ‘surer’….”

“Pèrsico, the Cavaliere.”

“Go on, Don Nico, everyone knows Don Filippo! Now, Sir, you come along with me, and I’ll take you to Donna Rosa’s, next door to the New Church.”

Before leaving it, I took a final look at the villa. There was nothing left of it now; all of a sudden, nothing left; as though in a moment a cloud had passed from before my eyes. There it was: poverty-stricken, old, empty… nothing left! And in that case, perhaps,… Granny Rosa, Duccella…. Nothing left, of them either? Phantoms of a dream, my sweet phantoms, my dear phantoms, and nothing more!

I felt chilled. A bare, dull, icy hardness. That stout peasant’s words: “Good folk! All for God…. No use for this world….” I could feel the Church in them: hard, bare, icy. Across those green fields that smiled no longer…. But then?

I allowed myself to be led away. I cannot say what long account followed of that Don Filippo, who was aptly named ‘surer’, because… a never-ending because… the old Government … not him, no, his father… a man of God too, he was, but… his father, or so the story went, at least. And with my weariness, in my weariness, as I went, all those impressions of a sordid reality, hard, bare, icy,… a donkey covered in flies, that refused to move, the squalid road, a crumbling wall, the fetid odour of the stout woman…. Oh, what a temptation to dash to the station and take the train home again! Twice, three times, I was on the point of doing it; I checked myself; said to myself: “Let us see!”

A narrow stair, filthy, damp, almost in pitch darkness; and the old woman shouting to me from below:

“Straight on, keep straight on…. The second floor…. The bell is broken, Sir…. Knock loud; she doesn’t hear; knock loud.”

As though I were deaf too…. “Here?” I said to myself as I climbed the stair. “How have they come down to this? Lost all their money? Perhaps, two women by themselves…. That Don Filippo….”

On the landing of the second floor, two old doors, low in the lintel, freshly painted. By one hung the broken cord of its bell. The other had none. This one or that? I knocked first at this one, loud, with my fist, once, twice, thrice. I tried to pull the bell of the other: it did not ring. Was it this one, then? I knocked at it, loud, three times, four times…. No answer! But how in the world? Was Duccella deaf too? Or was she not living with her grandmother? I knocked again, more loudly. I was turning to go, when I heard on the stair the heavy step and breathing of somebody coming up. A short, thickset woman, in one of those garments that signify devotion, with the penitential cord round her waist: a coffee-coloured garment, of devotion to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Over her head and shoulders a ‘spagnoletta’, of black lace; in her hand, a fat prayer-book and the key of the house.

She stopped on the landing and looked at me with pale, lifeless eyes from a fat white face ending in a flaccid chin: on her upper lip, here and there, at the corners of her mouth, a few hairs sprouted. Duecella.

I had had enough; I wished only to make my escape! Ah, if only she had remained with that apathetic, stupid air with which she stopped short in front of me, still a little breathless, on the landing! But no: she wanted to entertain me, she wanted to be polite–she, now, like that–with those eyes that were no longer hers, with that fat, colourless nun’s face, with that short, stout body, and a voice, a voice and a kind of smile which I did not recognise: entertainment, compliments, ceremonies, as though I were shewing her a great condescension; and she was absolutely determined that I should come in and see her grandmother, who would be so delighted at the honour… why, yes, why, yes…. “Step inside, please, step inside….”

To remove her from my path I would have given her a shove, even at the risk of sending her flying downstairs! What a flabby horror! What an object! That deaf old woman, doddering with age, without a tooth in her head, with her pointed chin that protruded horribly towards the tip of her nose, chewing and mumbling, and her pallid tongue shewing between her flaccid, wrinkled lips, and those huge spectacles, monstrously enlarging her sightless eyes, scarred by an operation for cataract, between their sparse lashes, long as the feelers of an insect!

“You have made a position for yourself.” (With the soft Neapolitan z–‘posi-szi-o-ne’.)

She could think of nothing else to say to me.

I made my escape without its ever having occurred to me for a moment to suggest the plan for which I had come. What was I to say? What was there to do? Why ask them to tell me their story? If they had really fallen into poverty, as might be supposed from the appearance of the house? Perfectly content with everything, stolid and happy with God! Oh, what a horrible thing faith is! Duccella, the blushing flower… Granny Rosa, the garden of the villa with its jasmines….

In the train, I felt as though I were rushing towards madness, through the night. In what world was I? My travelling companion, a man of middle age, dark, with oval eyes, like discs of enamel, and hair that gleamed with oil, he belonged certainly to this world; firm and well established in the consciousness of his own calm and well cared for beastliness, he understood it all to perfection, without worrying about anything; he knew quite well all that it concerned him to know, where he was going, why he was travelling, the house at which he would arrive, the supper that was being prepared for him. But I? Was I of the same world? His journey and mine… his night and mine…. No, I had no time, no world, no anything. The train was his; he was travelling in it. How on earth did I come to be travelling in it also? What was I doing in the world in which he lived? How, in what respect was this night mine, when I had no means of living it, nothing to do with it? He had his night and all the time he wanted, that middle-aged man who was now twisting his neck about with signs of discomfort in his immaculate starched collar. No, no world, no time, nothing: I stood apart from everything, absent from myself and from life; and no longer knew where I was nor why I was there. Images I carried in me, not my own, of things and people; images, aspects, faces, memories of people and things which had never existed in reality, outside me, in the world which that gentleman saw round him and could touch. I had thought that I saw them, and could touch them also, but no, they were all imagination! I had never found them again, because they had never existed: phantoms, a dream…. But how could they have entered my mind? From where? Why? Was I there too, perhaps, then? Was there an I there then that now no longer existed? No; the middle-aged gentleman opposite to me told me, no: that other people existed, each in his own way and with his own space and time: I, no, I was not there; albeit, not being there, I should have found it hard to say where I really was and what I was, being thus without time or space.

I no longer understood anything. And I understood nothing when, arriving in Rome and coming to the house, about ten o’clock at night, I found in the dining-room, as gay as though nothing had happened, as though a new life had begun during my absence, Fabrizio Cavalena, a Doctor once more and restored to the bosom of his family, Aldo Nuti, Signorina Luisetta and Signora Nene, sitting round the table.

How? Why? What had happened?

I could not get rid of the impression that they were sitting there, gay and reconciled to one another, to make a fool of me, to reward me with the sight of their gaiety for the trouble that I had taken on their behalf; not only this, but that, knowing the state of mind in which I should return from the expedition, they had clubbed together to confound me utterly, making me find here also a reality such as I should never have expected.

More than any of the rest she, Signorina Luisetta, filled me with scorn, Signorina Luisetta who was impersonating Duccella in love, that Duccella, the blushing flower, of whom I had so often spoken to her! I would have liked to shout in her face how I had found her that afternoon, down at Sorrento, that Duccella, and to bid her give up this play-acting, which was an unworthy and grotesque contamination! And he too, the young man, who seemed by a miracle to be the same young man of years ago, I would have liked to shout in his face how and where I had found Duccella and Granny Rosa.

But good souls all of you! Down there, those two poor women, happy in God, and you happy here in the devil! Dear Cavalena, why yes, changed back not merely into a Doctor, but into a boy, a bridegroom, sitting by his bride! No, thank you: there is no place for me among you: don’t get up; don’t disturb yourselves: I am neither hungry nor thirsty! I can do without everything, I can. I have wasted upon you a little of what is of no use to me; you know it; a little of that heart which is of no use to me; because to me only my hand is of use: there is no need, therefore, to thank me! Indeed, you must excuse me if I have disturbed you. The fault is mine, for trying to interfere. Keep your seats, don’t get up, good night.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (31)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD VI

Ik bleef in de deuropening zitten, keek naar de weg waarover de bevolking van Oeroe voorbijkwam. In een grote groep maakten ze een ochtendwandeling, ook al was het niet meer zo vroeg. De mensen bleven even staan.

Hé, daar heb je het jongetje van het marmotje, dachten ze, en soms wierp iemand me een geldstuk toe. Toen ik de munten naderhand bij elkaar telde, was het genoeg om eten te kopen. Ik sloot de deur. Cherubijn sliep nog. Ook de marmot lag, met de ogen stijf dicht, in de mand.

De straten van Oeroe waren slecht. Ik moest om kuilen met water heen lopen. De wegen werden niet onderhouden. Het had geen zin. Ieder jaar vroren ze kapot. Veel erger dan in andere plaatsen. Er liep een waterader zo groot als een onderaardse rivier onder het dorp. Heel Oeroe was vochtig. De huizen zaten vol schimmel. Over het algemeen waren de mensen van Oeroe melancholiek. In deze dagen viel dat niet zo op, omdat men kermis vierde, maar de rest van het jaar liepen ze rond met lange gezichten.

Langs de straten liepen goten. Ze waren gedeeltelijk weggespoeld. Op hogere gedeelten langs de weg speelden gele kinderen in geel zand. Een enkele jongen probeerde het mierrijden maar gaf het spoedig op. Voor deze sport was veel tact en een uitgesproken aanleg nodig. Als ik met deze kinderen, die van mijn leeftijd waren, een wedstrijd zou houden, dan zouden ze niet meer halen dan hooguit vijf stuks over een afstand van dertig centimeter te laten lopen, in de tijd van tien minuten. Met het lastigste soort mieren kwam ik nog altijd wel tot vijftien stuks, in dezelfde tijd en over dezelfde afstand.

Ik liep vlug verder om aan de bekoring van het spel weerstand te bieden.

Er waren niet veel winkels in Oeroe. Het waren handeltjes in allerlei goederen. Ze deden niet zulke beste zaken, maar het lukte me toch om brood, suiker en boter te kopen.

Het werd warm. De lucht voorspelde dat het een hete dag zou worden. Tegen het zonlicht kon ik talrijke spiraaltjes, bolletjes en ringetjes zien bewegen.

Cherubijn stond in de open deur. Keek onbeweeglijk naar één punt. Merkte dat ik kwam aanlopen. Hij hield zijn hoofd in dezelfde stand en kon toch in mijn richting kijken door zijn been en zijn houten poot te verzetten. Hij was erop getraind de functies van zijn luie nekspieren gedeeltelijk over te dragen aan de spieren van zijn middenrif.

Hij had honger. Graaide naar het brood. Trok er een stuk af en begon ervan te eten. Ik trok vliegensvlug het brood uit zijn handen, sprong achter hem zodat hij me niet kon zien en hij als een blinde om zich heen greep.

Ik zei dat we in het vervolg aan tafel zouden eten. Hij was verbaasd. De tafel lag vol rommel die ik opzij schoof. Ik zocht een mes, sneed het brood, smeerde de sneeën vol boter en strooide er suiker op. Ik wist dat het zo hoorde. Eten aan tafel. Cherubijn had het nooit nodig gevonden. Toch begreep hij iets van mijn bedoelingen.

Maar toen ik later sprak over het onderhoud van de wagen, over de vuiligheid, de zurige lucht, en over de marmot die de kost voor ons verdiende, knikte hij alleen ja en hoorde niets van alles wat ik vertelde. Vond het niet nodig ook om het te horen.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD V

INKOPEN DOEN IN OEROE

Het was een mooie morgen. ‘s Nachts had het geregend. De ozon vrat aan de zurige lucht in de wagen. De zon liep in een drafje langs de hemel en was niet vergeten alle soorten mensen en dieren te wekken.

De wereld leefde. De harten in de dorpen Oeroe en Boeroe klopten traag, omdat er kermis was gevierd. De dorpen borgen menig delirium, niet iedereen was op tijd gestopt met zuipen, en vele kapotte koppen.

Hoewel Boeroe en Oeroe samen één gemeente vormden, waren het twee elkaar vijandig gezinde dorpen. De kerels dachten dat ze bij elke mogelijke gelegenheid moesten vechten, in de waterplaatsen van de cafés en op stille plekken. Om elkaar de dorpsbelangen in het gezicht te ranselen.

Zo waren er die morgen in Oeroe en Boeroe mannen die, geplaagd door hun kapotgebeukte gezichten, naar de dokter gingen en terugkeerden met hun koppen in wit verband. Er waren nog steeds mensen die beweerden dat de oorlog hun wat geleerd had!

Cherubijn sliep nog toen ik de deur openduwde. Als ik dicht bij hem stond, rook ik dat zijn adem naar rottend fruit stonk. Hij lag aangekleed in bed. Zijn kop onnatuurlijk scheef omdat zijn nekspieren het niet beter wisten. Zijn handen lagen samengevouwen op zijn buik, alsof hij bad. Voor wat zou Cherubijn moeten bidden? Zijn houten poot hing langs het bed omlaag.

De marmot was uit zijn mand gesprongen en zat in de open deur. Keek naar buiten als een vroegwijze die zijn weet wel van de wereld had. Keek soms naar mij. Hij verwachtte dat ik hem vreten zou geven. Hij keek niet naar Cherubijn. Verwachtte van hem niets. Waarschijnlijk had hij hem altijd als een meubelstuk van de wagen beschouwd.

Ik liep naar buiten. In de wei aan de overkant van de straat graasden onnozele koeien. Hun domme lijven, die niets anders waren dan melkfabrieken, pasten niet op de veel te groene spiegel van het ochtendgras dat plezierig was, maar nu weggevreten werd door de trage gele tanden.

De melker lag in de wei te slapen. Zijn hoofd op een steen. Hij droomde zich een jakobsladder naar de hemel waar een troon stond vanwaar hij, de melker, vrede zou stichten tussen Oeroe en Boeroe. Melkers blijven altijd onnozel!

Terwijl ik blaadjes plukte van klaver en paardebloem, zag ik dat het gras huiverde wanneer een koeienkop in de buurt kwam en het bewasemde met een vochtige adem.

De marmot was tevreden met het ontbijt dat ik hem gaf: gras en paardebloemen. Hij vrat het allemaal op en ging weer in de mand liggen. De ogen dicht.

Ik was weer helemaal alleen.

Nu zou ik de wagen moeten opruimen, zoals ik me had voorgenomen. Ik had geen zin. Dat was niet plezierig. Ik had het mezelf min of meer beloofd. Het was nodig om beloften tegenover jezelf te houden. Maar op klaarlichte dag was de wagen zo oud en zo rot dat er geen beginnen aan was. In het donker had ik alleen gezien dat hij vuil was en slecht onderhouden, nu zag ik ook dat het hout vermolmd was. De ruiten waren gebarsten. De duigen die het dak steun moesten geven waren doorgeroest.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (D)

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

D

DAGUERRÉOTYPE: Remplacera la peinture (v. photographie).

DAMAS: Seul endroit où l’on sache faire les sabres. Toute bonne lame est de Damas.

DAME: Tout pour les dames. Honneur aux dames. Ne jamais dire: «Ces dames sont aux salons.»

DANSE: On ne danse plus, on marche.

DANTON: «De l’audace, encore de l’audace, toujours de l’audace!»

DARTRE: signe de santé (v. boutons).

DARWIN: Celui qui dit que nous descendons du singe.

DAUPHIN: Porte les enfants sur son dos.

DÉBAUCHE: Cause de toutes les maladies des célibataires.

DÉCHAÎNER: On déchaîne ses chiens et les mauvaises passions.

DÉCOR de théâtre: N’est pas de la peinture: il suffit de jeter en vrac sur la toile un seau de couleurs; puis on l’étend avec un balai; et l’éloignement avec la lumière fait l’illusion.

DÉCORATION de la Légion d’honneur: La blaguer mais la convoiter. Quand on l’obtient, toujours dire qu’on ne l’a pas demandée.

DÉCORUM: Donne du prestige. Frappe l’imagination des masses. «Il en faut! Il en faut!»

DÉFAITE: S’essuie, et elle est tellement complète qu’il n’en reste personne pour en porter la nouvelle.

DÉFILÉ: Toujours citer les Thermopyles. Le défilé des Vosges sont les Thermopyles de la France (s’est beaucoup dit en 1870).

DÉICIDE: S’indigner contre, bien que le crime ne soit pas fréquent.

DÉJEUNER des garçons: Exige des huîtres, du vin blanc et des gaudrioles.

DÉMÊLOIR: Fait tomber les cheveux.

DÉMOSTHÈNE: Ne prononçait pas de discours sans avoir un galet dans la bouche.

DENTS: Sont gâtées par le cidre, le tabac, les dragées, la glace, boire de suite après le potage et dormir la bouche ouverte. Dent oeillère: dangereux de l’arracher parce qu’elle correspond à l’oeil. L’arrachement d’une dent «ne fait pas jouir» .

DENTISTES: Tous menteurs. Se servent du baume d’acier. On les croit aussi pédicures. Se disent chirurgiens comme les opticiens se disent se disent ingénieurs.

DÉPURATIF: Se prend en cachette.

DÉPUTÉ: L’être, comble de la gloire. Tonner contre la Chambre des députés. Trop de bavards à le Chambre. Ne font rien.

DÉRATÉ: Courir comme un dératé. Inutile de savoir que l’extirpation de la rate n’a jamais été pratiquée sur l’homme.

DERBY: Mot de courses. Très chic.

DESCARTES: Cogito, ergo sum.

DESERT: Produit des dattes.

DESSERT: Regretter qu’on n’y chante plus. Les gens vertueux le méprisent: «Non! non! pas de pâtisseries! Jamais de dessert!»

DESSIN (l’art du): Se compose de trois choses: le ligne, le grain, et le grainé fin; de plus, le trait de force. Mais le trait de force, il n’y a que le maître seul qui le donne. (Christophe.)

DEVOIRS: Les exiger de la part des autres, s’en affranchir. Les autres en ont envers nous, mais on n’en a pas envers eux.

DÉVOUEMENT: Se plaindre de ce que les autres en manquent. «Nous sommes bien inférieurs au chien, sous ce rapport!»

DIAMANT: On finira par en faire! Et dire que ce n’est que du charbon! Si nous en trouvions un dans son état naturel, nous ne le ramasserions pas!

DIANE: Déesse de la chasse-teté.

DICTIONNAIRE: En dire: «N’est fait que pour les ignorants.» Dictionnaire de rimes: s’en servir? Honteux!

DIDEROT: Toujours suivi de d’Alembert.

DIEU: Voltaire lui-même l’a dit: «Si Dieu n’existait pas, il faudrait l’inventer.»

DILETTANTE: Homme riche, abonné à l’Opéra.

DILIGENCES: Regretter le temps des diligences.

DÎNER: Autrefois on dînait à midi, maintenant on dîne à des heures impossibles. Le dîner de nos pères était notre déjeuner, et notre déjeuner était leur dîner. Dîner si tard que ça n’appelle pas dîner, mais souper.

DIOGÈNE: «Je cherche un homme… Retire-toi de mon soleil.»

DIPLOMATIE: Belle carrière, mais hérissée de difficultés, plaine de mystères. Ne convient qu’aux gens nobles. Métier d’une vague signification, mais au-dessus du commerce. Un diplomate est toujours fin et pénétrant.

DIPLÔME: Signe de science. Ne prouve rien.

DIRECTOIRE (le): Les hontes du Directoire. «Dans ce temps-là l’honneur s’était réfugié aux armées.» Les femmes, à Paris, se promenaient toutes nues.

DISSECTION: Outrage à la majesté de la mort.

DIVA: Toutes les cantatrices doivent être appelées Diva.

DIVORCE: Si Napoléon n’avait pas divorcé, il serait encore sur le trône.

DIX (Conseil des): On ne sait pas ce que c’est, mais c’est formidable! Délibérait masqué. En trembler encore.

DJINN: Nom d’une danse orientale.

DOCTEUR: Toujours précédé de bon, et, entre hommes, dans la conversation, de foutre: «Ah! foutre, docteur!» Est un aigle quand il a votre confiance, n’est plus qu’un âne dès que vous êtes brouillés. Tous matérialistes. «C’est qu’on ne trouve pas la foi au bout d’un scalpel.»

DOCTRINAIRES: Les mépriser. Pourquoi? On n’en sait rien.

DOCUMENT: Toujours de la plus haute importance.

DOGE: Epousait la mer. On n’en connaît qu’un: Marino Faliero.

DOIGT: Le doigt de Dieu se fourre partout.

DOLMEN: A rapport aux anciens Français. Pierre qui servait au sacrifice des druides. Il n’y en a qu’en Bretagne. On n’en sait pas plus.

DÔME: Tour de forme (sic) architecturale. S’étonner de ce que cela puisse tenir tout seul. En citer deux: celui des Invalides et celui de Saint-Pierre de Rome.

DOMICILE: Toujours inviolable. Cependant la Justice, la Police, y pénètrent quand elles veulent. Je regagne mes pénates. Je rentre dans mes lares.

DOMINOS: On y joue d’autant mieux qu’on est gris.

DOMPTEURS de bêtes féroces: Emploient des pratiques obscènes.

DONJON: Eveille des idées lugubres.

DORMIR: Trop dormir épaissit le sang.

DORTOIRS: Toujours spacieux et bien aérés. Préférables aux chambres pour la moralité des élèves.

DOS: Une tape dans le dos peut rendre poitrinaire.

DOUANE: On doit se révolter contre et la frauder (v. octroi).

DOULEUR: A toujours un résultat favorable. La véritable est toujours contenue.

DOUTE: Pire que la négation.

DRAP: Tous les draps viennent d’Elbeuf.

DRAPEAU national: Sa vue fait battre le coeur.

DROIT (le): On ne sait pas ce que c’est.

DRÔLE: Doit s’employer à tout propos: «C’est drôle.»

DUEL: Tonner contre. N’est pas une preuve de courage. Prestige de l’homme qui a eu un duel.

DUPE: Mieux vaut être fripon que dupe.

DUPUYTREN: Célèbre par sa pommade et son musée.

DUR: Ajouter invariablement comme du fer. Il y a bien dur comme la pierre, mas c’est moins énergique.

Gustave Flaubert

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (D)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (30)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

3

The woman, as from the expression on my face she had at once realised my contempt for her, realised also the sense of degradation, the disgust that filled me, and the impulse that followed them.

The first, my contempt, had pleased her, possibly because she intended to make use of it for her own secret ends, submitting to it before my eyes with an air of pained humility. My sense of degradation, my disgust had not displeased her, perhaps because she herself felt them also and even more than I. What she resented was my sudden coldness, was seeing me all at once resume the cloak of my professional impassivity. And she too stiffened; looked at me coldly, and said:

“I expected to see you with Signorina Cavalena.”

“I gave her your note to read,” I replied. “She was just starting for the Kosmograph. I asked her to come.”

“She would not?”

“She did not like to. Perhaps in her capacity as a hostess…”

“Ah!” she threw back her head, “Why,” she went on, “that was precisely why I asked her to come, because she was acting as a hostess.”

“I pointed that out to her,” I said.

“And she did not think that she ought to come?”

I raised my hands.

She remained for a moment in thought; then, almost with a sigh, said:

“I have made a mistake. That day (do you remember?) when we all went together to the Bosco Sacro, she struck me as so charming, and pleased, too, at having my company, I realise that she was not a hostess then. But, surely, you are her guest also?”

She smiled, hoping to hurt me, as she aimed this question at me like a treacherous blow. And indeed, notwithstanding my determination to remain aloof from everything and everyone, I did feel hurt. So much so that I replied:

“But with two guests, as you must know, one may seem more important than the other.”

“I thought it was just the opposite,” she replied. “You don’t like her?”

“I neither like her nor dislike her, Signora.”

“Is that really so? Forgive me, I have no right to expect you to be frank with me. But I decided that I would be frank with you to-day.”

“And I have come…”

“Because Signorina Cavalena, as you tell me, wished to let it be seen that she attaches more importance to her other guest?”

“No, Signora. Signorina Cavalena said that she wished to remain apart.”

“And you too?”

“I have come.”

“And I thank you, most cordially. But you have come alone! And that–perhaps I am again mistaken–does not encourage me, not that I suppose for a moment, mind, that you, like Signorina Cavalena, attach more importance to the other guest; on the contrary….”

“You mean?”

“That this other guest is of no importance to you whatever; not only that, but that you would actually be glad if he were to meet with some accident, if only because Signorina Cavalena, by refusing to come with you, has shewn that she placed his interests above yours. Do I make myself clear?”

“Ah, no, Signora, you are mistaken!” I exclaimed sharply.

“It does not annoy you?”

“Not in the least. That is to say… well, to be honest,… it does annoy me, but it no longer affects me personally. I do really feel that I stand apart.”

“There, you see?” she interrupted me. “I feared as much, when I saw you come in by yourself. Confess that you would not feel yourself so much apart at this moment if the Signorina had come with you….”

“But if I have come myself!”

“To remain apart.”

“No, Signora. Listen, I have done more than you think. I have discussed the whole matter fully with that poor fellow and have tried in every possible way to make it clear to him that he has no right to expect anything after all that has happened, according to his own account at least.”

“What has he told you?” asked the Nestoreff, in a tone of determination, her face darkening.

“All sorts of silly things, Signora,” I replied. “He is raving. And his state is all the more alarming, believe me, since he is incapable, to my mind, of any really serious and deep feeling. As is already shewn by the fact of his coming here with a certain plan….”

“Of revenge?”

“Not exactly of revenge. He doesn’t know himself, even, what he feels. It is partly remorse … a remorse which he does not wish to feel; the irritating sting of which he feels only upon the surface, because, I repeat, he is equally incapable of a true, a sincere repentance which might mature him, make him recover his senses. And so it is partly the irritation of this remorse, which is maddening; partly rage, or rather (rage is too strong a word to apply to him) let us say vexation, a bitter vexation, which he does not admit, at having been tricked.”

“By me?”

“No. He will not admit it!”

“But you think so?”

“I think, Signora, that you never took him seriously, that you made use of him to break away from….”

I refused to utter the name: I pointed towards the six canvases. The Nestoroff knitted her brows, lowered her head. I stood gazing at her for a moment and, deciding to go on to the bitter end, pressed the point:

“He speaks of a betrayal. Of his betrayal by Mirelli, who killed himself because of the proof that he wished to give him that it was easy to obtain from you (if you will pardon my saying so) what Mirelli himself had failed to obtain.”

“Ah, he says that, does he?” broke from the Nestoroff.

“He says it, but he admits that he never obtained anything from you. He is raving. He wishes to attach himself to you, because if he goes on like this (he says) he will go mad.”

The Nestoroff looked at me almost with terror.

“You despise him?” she asked me.

I replied:

“I certainly do not admire him. Sometimes he makes me feel contempt for him, at other times pity.”

She sprang to her feet as though urged by an irrepressible impulse:

“I despise,” she said, “people who feel pity.”

I replied calmly:

“I can quite understand your feeling like that.”

“And you despise me!”

“No, Signora, far from it!”

She gazed at me for a while; smiled with a bitter disdain:

“You admire me, then?”

“I admire in you,” was my answer, “what may perhaps arouse contempt in other people; the contempt, for that matter, which you yourself wish to arouse in other people, so as not to provoke their pity.”

She gazed at me more fixedly; came forward until we stood face to face, and asked me:

“And don’t you mean by that, in a sense, that you also feel pity for me?”

“No, Signora. Admiration. Because you know how to punish yourself.”

“Indeed? so you understand that?” she said, with a change of colour, and a shudder, as though she had felt a sudden chill.

“For some time past, Signora.”

“In spite of everyone’s despising me?”

“Perhaps it was Just because everyone despised you.”

“I too have been aware of it for some time,” she said, holding out her hand and clasping mine tightly. “Thank you! But I can punish other people too, you know!” she at once added, in a threatening tone, withdrawing her hand and raising it in the air with outstretched forefinger. “I can punish other people too, without pity, because I have never sought any pity for myself and seek none now!”

She began to pace up and down the room, repeating:

“Without pity… without pity….”

Then, coming to a halt:

“You see?” she said, with an evil gleam in her eyes. “I do not admire you, for instance, who can overcome contempt with pity.”

“In that case, you ought not to admire yourself either,” I said with a smile. “Think for a moment, and then tell me why you invited me to

call upon you this morning.”

“You think it was out of pity for that… poor fellow, as you call him?”

“For him, or for some one else, or for yourself.”

“Nothing of the sort!” her denial was emphatic. “No! No! You are mistaken! Not a scrap of pity for anyone! I wish to be what I am; I intend to remain myself. I asked you to come in order that you might make him understand that I do not feel any pity for him and never shall!”

“Still, you do not wish to do him any injury.”

“I do indeed wish to do him an injury, by leaving him where he is and as he is.”

“But since you are so pitiless, would you not be doing him a greater injury if you were to call him back to you! Instead of driving him away….”

“That is because I wish, I myself, to remain as I am! I should be doing a greater injury to him, yes; but I should be conferring a benefit on myself, since I should take my revenge upon him instead of taking it upon myself. And what harm do you suppose could come to me from a man like him? I do not wish him any, you understand. Not because I feel any pity for him, but because I prefer not to feel any for myself. I am not interested in his sufferings, nor would it interest me to make him suffer more. He has had enough trouble. Let him go and weep somewhere else! I have no intention of weeping.”

“I am afraid,” I said, “that he has no longer any intention of weeping either.”

“Then what does he intend to do?”

“Well! Being, as I have already told you, incapable of doing anything, in the state of mind in which he is at present, he might unfortunately become capable of anything.”

“I am not afraid of him! The point is this, you see. I asked you to come and see me in order to tell you this, to make you understand this, so that you in turn may make him understand. I am not afraid that any harm can come to me from him, not even if he were to kill me, not even if, on his account, I had to go and end my days in prison! I am running that risk as well, you know! Deliberately, I have exposed myself to that risk as well. Because I know the man I have to deal with. And I am not afraid. I have let myself imagine that I was feeling a little afraid; imagining that, I have made an effort to send away from here a man who was threatening me, and everyone, with violence. It is not true. I have acted in cold blood, not out of fear! Any evil, even that, would count for less with me. Another crime, imprisonment, death itself, would be lesser evils to me than what I am now suffering and wish to keep on suffering. So take care not to try and arouse any pity in me for myself or for him. I have none! If you have any for him, you who have so much pity for everyone, make him, make him go away! That is what I want from you, simply because I am not afraid of anything!”

As she made this speech, she shewed in her whole person a desperate rage at not really feeling what she would have liked to feel.

I remained for some time in a state of perplexity in which dismay, anguish and also admiration were mingled; then I threw up my hands, and, so as not to make a vain promise, told her of my plan of going down to the villa by Sorrento.

She stood and listened to me, recoiling upon herself, perhaps to deaden the smart that the memory of that villa and of the two disconsolate women caused her; shut her eyes sorrowfully; shook her head; said:

“You will gain nothing.”

“Who knows?” I sighed. “One can at least try.”

She pressed my hand:

“Perhaps,” she said, “I too shall do something for you.”

I gazed at her face, with more consternation than curiosity:

“For me? What can that be?”

She shrugged her shoulders; made an effort to smile:

“I said, ‘perhaps’…. Something. You will see.”

“I thank you,” I added. “But really I do not see what you can possibly do for me. I have always asked so little of life, and I mean now to ask less than ever. Indeed, I ask it for nothing more, Signora.”

I said good-bye to her and left the house, my thoughts filled with this mysterious promise.

What does she propose to do? In cold blood, as I supposed at the time, she has sent away Carlo Ferro, with the knowledge, which does not cause her the slightest alarm, either for herself or for him or for the rest of us, that at any moment he may come rushing upon the scene here and commit a crime on his own account. How can she, knowing this, think of doing anything for me? What can she do? Where do I come in, in all this wretched entanglement? Does she intend to involve me in it in some way? With what object? She failed to get anything out of me, beyond an admission of my friendship long ago with Giorgio Mirelli and of a vague sentiment now for Signorina Luisetta. She cannot seize hold of me either by that friendship with a man who is now dead or by this sentiment which is already dying in me.

And yet, one never knows. I cannot set my mind at rest.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (30)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature