Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Frank Wedekind

(1864-1918)

Ilse

Ich war ein Kind von fünfzehn Jahren,

Ein reines unschuldsvolles Kind,

Als ich zum erstenmal erfahren,

Wie süß der Liebe Freuden sind.

Er nahm mich um den Leib und lachte

Und flüsterte: O welch ein Glück!

Und dabei bog er sachte, sachte

Den Kopf mir auf das Pfühl zurück.

Seit jenem Tag lieb ich sie alle,

Des Lebens schönster Lenz ist mein;

Und wenn ich keinem mehr gefalle,

Dann will ich gern begraben sein.

Frank Wedekind poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Frank Wedekind

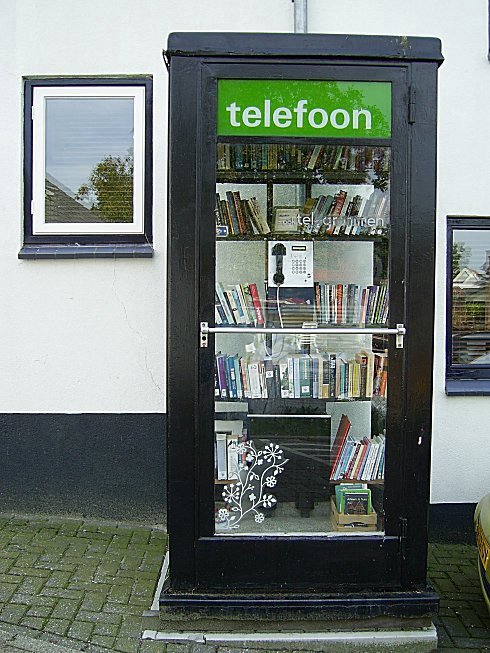

Bibliotheek in een telefooncel.

Gratis ruilbibliotheek op de hoek van de Havendijk en Slotstraat in Beesd.

foto marieke ◊ kempis.nl 2012

Guerilla libraries: Books. The last chapter?

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Guerilla Libraries

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (32)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

1

I understand, at last.

Upset? No, why should I be? So much water has passed under the bridges; the past is dead and distant. Life is here now, this life: a different life. Lawns, round about, and stages, the buildings miles away, almost in the country, between green grass and blue sky, of a cinematograph company. And she is here, an actress now…. He an actor too? Just fancy! Why, then, they must be colleagues? Splendid; I am so glad….

Everything perfect, everything smooth as oil. Life. That rustle of her blue silk skirt, now, with that curious white lace jacket, and that little winged hat like the helmet of the god of commerce, on her copper-coloured hair… yes. Life. A little heap of gravel turned up by the point of her sunshade; and an interval of silence, With her eyes wandering, fixed on the point of her sunshade that is turning up that little heap of gravel.

“What? Yes, of course, dear: a great bore.”

This is undoubtedly what must have happened yesterday, during my absence. The Nestoroff, with those wandering eyes of hers, strangely wide open, must have gone to the Kosmograph on purpose, in the hope of meeting him; she must have strolled up to him with an indifferent air, as one goes up to a friend, an acquaintance whom one happens to meet again after many years, and the butterfly, without the least suspicion of the spider, must have begun to flap his wings, quite exultant.

But how in the world did not Signorina Luisetta notice anything?

Well, that is a satisfaction which Signora Nestoroff must have had to forego. Yesterday, Signorina Luisetta, to celebrate her father’s return home, did not go with Signor Nuti to the Kosmograph. And so Signora Nestoroff cannot have had the pleasure of shewing this proud young lady who, the day before, had declined her invitation, how she, at any moment, whenever the fancy took her, could tear from the side of any proud young lady and recapture for herself all the mad young gentlemen who threatened tragedies, “st”, like that, by holding up a finger, and at once tame them, intoxicate them with the rustle of a silk skirt and a little heap of gravel turned up with the point of a sunshade. A bore, yes, a great bore unquestionably, because to this pleasure which she has had to forego Signora Nestoroff attached great importance.

That evening, knowing nothing of what had happened, Signorina Luisetta saw the young gentleman return home completely transformed, radiant with happiness. How was she to suppose that this transformation, this radiance could be due to a meeting with the Nestoroff, if, whenever she thinks with terror of that meeting, she sees red, black, confusion, madness, tragedy? And so this change, this radiance, was the effect of Papa’s return home on him also? Well, that it is of any great importance to him, her father’s return home, Signorina Luisetta cannot suppose, no; but that he should take pleasure in it, and seek to attune himself to other people’s rejoicing, why in the world not?

How else is his jubilation to be explained? And it is something to be thankful for; it is a thing to rejoice in, because this jubilation shews that his heart has become lighter, more open, so that he can readily assimilate the joy of other people.

These must certainly have been the thoughts of Signorina Luisetta. Yesterday; not to-day.

To-day she came to the Kosmograph with me, her face clouded. She had found, greatly to her surprise, that Signor Nuti had already left the house at an early hour, while it was still dark. She did not wish to display, as we went along, resentment and alarm, after the spectacle offered me last night of her gaiety; and so asked me where I had been yesterday and what I had done. “I? Oh, only a little pleasure jaunt….” And had I enjoyed myself? “Oh, immensely, to begin with at least. Afterwards….” The way things happen. We make all the arrangements for a pleasure party; we imagine that we have thought of everything, have taken every precaution so that the excursion may be a success, with no unfortunate incident to mar it; and yet there is always something, one of the many things, of which we have not thought; one thing escapes us… well, for instance, suppose there is a family with a number of children, who propose to go and spend a fine summer day picnicking in the country, there are the second child’s shoes, in one of which there is a nail, a mere nothing, a tiny nail, inside, sticking up in the heel, which needs hammering down. The mother remembered it, as soon as she got out of bed; but afterwards, you know what happens–with everything to get ready for the excursion, she forgot all about it. And that pair of shoes, with their little tongues sticking up like the pricked ears of a wily rabbit, standing in the row among all the other pairs, cleaned and polished and all ready for the children to put on, wait there and seem to be gloating in silence over the trick they are going to play on the mother who has forgotten all about them and who now, at the last moment, is in a greater bustle than ever, in wild confusion, because the father is down below at the foot of the stair shouting to her to make haste and all the children round her shout to her to make haste, they are so impatient. That pair of shoes, as the mother takes them to thrust them hurriedly on the child’s feet, say to her with a mocking laugh:

“Ah yes, mother dear; but us, you know? You have forgotten about us; and you’ll see that we shall spoil the whole day for you: when you are half way there that little nail will begin to hurt your child’s foot and make it cry and limp.”

Well, something of that sort happened to me too. No, not a nail to be hammered down in my boot. Another little detail had escaped my memory…. “What?” Nothing: another little detail. I did not wish to tell her. Another thing, Signorina Luisetta, which perhaps had long ago broken down in me.

To say that Signorina Luisetta paid me any close attention would not be true. And, as we went on our way, while I allowed my lips to go On speaking, I was thinking:

“Ah, you are not interested, my dear child, in what I am telling you? My misadventure leaves you indifferent, does it? Well, you shall see with what an air of indifference I, in my turn, to pay you back in your own coin, am going to receive the unpleasant surprise that is in store for you, as soon as you enter the Kosmograph me: you shall see!”

In fact, before we had advanced five yards across the tree-shaded lawn in front of the first building of the Kosmograph, there we saw, strolling side by side, like the dearest of friends, Signor Nuti and Signora Nestoroff: she, with her sunshade open, resting upon her shoulder, and twirling the handle.

What a look Signorina Luisetta gave me! And I: “You see! They are taking a quiet stroll. She is twirling her sunshade.”

So pale, however, so pale had the poor child turned, that I was afraid of her falling to the ground, in a faint: instinctively I put out my hand to support her arm; she withdrew her arm angrily, and looked me straight in the face. Evidently the suspicion flashed across her mind that it was my doing, a plot on my part (by arrangement, very possibly, with Polacco), that quiet and friendly reconciliation of Nuti and Signora Nestoroff, the first-fruits of the visit paid by me to that lady two days ago, and perhaps also of my mysterious absence yesterday. It must have seemed to her a vile mockery, all this secret machination, as it entered her mind in a flash. To make her dread the imminence, day after day, of a tragedy, should those two meet; to make her conceive such a terror of their meeting; to make her suffer such agony in order to pacify his ravings with a piteous deception, which had cost her so dear, and to what purpose! To offer her as a final reward the delicious picture of those two taking their quiet morning stroll under the trees on the lawn? Oh, villainy! Was it for this? For the amusement of laughing at a poor child who had taken it all seriously, plunged into the midst of this sordid, vulgar intrigue? She looked for nothing pleasant, in the absurd, miserable conditions of her life; but why this as well? Why mockery also? It was vile!

All this I read in the poor child’s eyes. Could I prove to her, there and then, that her suspicion was unjust, that life is like that–to-day more than ever it was before–made to offer such spectacles; and that I myself was in no way to blame?

I had hardened my heart; I was glad that she should pay for the injustice of her suspicion by her suffering at that spectacle, at the sight of those people, to whom I as well as she, unasked, had given something of ourselves, something that was now smarting, bruised and wounded, inside us. But we deserved it! And now, it pleased me to have her at this moment as my companion, while those two strolled up and down there without so much as seeing us. Indifference, indifference, Signorina Luisetta, there you are!

“If you will excuse me,” it occurred to me to say to her, “I shall go and get my camera, and take my place here, as is my duty, impassive.” And I felt a strange smile on my lips, which was almost the grin of a dog when he bares his teeth at some secret thought. I was looking meanwhile towards the door of the building beyond, from which emerged, coming towards us, Polacco, Bertini and Fantappiè. Suddenly there occurred a thing which I ought really to have expected, which justified Signorina Luisetta in trembling so violently and rebuked me for having chosen to remain indifferent. My mask of indifference I was obliged to throw aside in a moment, at the threat of a danger which did really seem to all of us imminent and terrible. I caught the first glimpse of it in the appearance of Polacco, who had come close up to us with Bertini and Fantappiè. They were talking among themselves, evidently of that couple who were still strolling beneath the trees, and all three were laughing at some witticism that had fallen from Fantappiè, when all of a sudden they stopped short in front of us with faces of chalk, staring eyes, all three of them. But most of all in the face of Polacco I read terror. I turned to look over my shoulder: Carlo Ferro!

He was coming up behind us, still with his travelling cap on his head, as he had left the train a few minutes earlier. And those two, meanwhile, continued to stroll up and down, together, without the least suspicion, under the trees. Did he see them! I cannot say. Fantappiè had the presence of mind to shout:

“Hallo, Carlo Ferro!”

The Nestoroff turned round, left her companion standing, and then one saw–free of charge–the moving spectacle of a lion-tamer who amid the terror of the spectators advances to meet an infuriated animal. Calmly she advanced, without haste, still balancing her open sunshade on her shoulder. And she had a smile on her lips, which said to us, without her deigning to look at us: “What are you afraid of, you idiots! I am here, a’nt I?” And a look in her eyes which I shall never forget, the look of one who knows that everyone must see that no fear can find a place in a person who looks straight ahead and advances so. The effect of that look on the savage face, the disordered person, the excited gait of Carlo Ferro was remarkable. We did not see his face, we saw his body grow limp and his pace slacken steadily as the fascination drew nearer to him. And the one sign that she too must be feeling somewhat agitated was this: she began to address him in French.

None of us cast a glance beyond her, where Aldo Nuti remained by himself, planted among the trees, but suddenly I became aware that one of us, she, Signorina Luisetta, was looking in that direction, was looking at him, and had perhaps looked at nothing else, as though for her the terror lay there and not in the two at whom the rest of us were gazing, in dismayed suspense.

But nothing occurred for the moment. To break the storm, making a great din, there dashed upon the lawn, in the nick of time, Commendator Borgalli accompanied by various members of the firm and employees from the manager’s office. Bertini and Polacco, who were with us, were swept away; but the managing director’s fierce reproaches were aimed also at the other two producers who were absent. The work was going to pieces! No control of production; the wildest confusion; a perfect Tower of Babel! Fifteen, twenty subjects left in the air; the companies scattered here, there and everywhere, when it had been announced, weeks ago, that they must be assembled and ready to get to work on the tiger film, on which thousands and thousands of lire had been spent! Some were off to the hills, some to the sea; eating their heads off! What was the use of keeping the tiger there!

There was still the whole part of the actor who was to kill it wanting? And where was the actor? Oh, he had just arrived, had he? How was that? Where had he been?

Actors, supers, scene-painters had come pouring in a crowd from every direction at the shouts of Commendator Borgalli, who had the satisfaction of measuring thus the extent of his own authority, and the fear and respect in which he was held, by the silence in which all these people stood round and then dispersed, when he concluded his harangue with the words:

“To your work! Get along back to work!”

There vanished from the lawn, as though it had been first of all submerged by this tide of people, then carried away by their ebb, every trace of the–shall we say–dramatic situation of a moment earlier; there, in the foreground, the Nestoroff and Carlo Ferro; beyond them, Nuti, solitary, apart, under the trees. The ground lay empty before us. I heard Signorina Luisetta sobbing by my side:

“Oh, heavens, oh, heavens,” and she wrung her hands. “Oh, heavens, what next? What will happen next?”

I looked at her with irritation, but tried, nevertheless, to comfort her:

“Why, what do you want to happen? Keep calm! Didn’t you see? All arranged beforehand. … At least, that is my impression. Yes, of course, keep calm! This surprise visit from Ferro…. I bet she knew all about it; I shouldn’t be surprised if she telegraphed to him yesterday to come; why yes, of course, to let him find her here engaged in a friendly conversation with Signor Nuti. You may be sure that is what it is.” “But he? He?”

“Who is “he”? Nuti?”

“If it is all a trick played by those two….”

“You are afraid he may notice it?”

“Yes! Yes!”

And the poor child began again to wring her hands.

“Well? And what if he does notice it?” said I. “You needn’t worry yourself; he won’t do anything. Depend upon it, this was arranged beforehand too.”

“By whom? By her? By that woman?”

“By that woman. She must first have made quite certain, before talking to him, that the other man would be able to turn up in time, without any danger to anyone; keep calm! Otherwise, Ferro would not have come upon the scene.”

We were quits. My statement embodied a profound contempt for Nuti; if Signorina Luisetta desired peace of mind, she was bound to accept it. She did so long to secure peace of mind, Signorina Luisetta; but on these terms, no; she would not. She shook her head violently: no, no.

There was nothing then to be done! But as a matter of fact, notwithstanding my faith in the Nestoroff’s cold perspicacity, in her power, when I reminded myself of Nuti’s desperate ravings, I did not feel any too certain myself that it was with him that we should concern ourselves. But this thought increased my irritation, already moved by the spectacle of that poor, terrified child. Despite my resolution to place and keep all these people in front of my machine as food for its hunger while I stood impassively turning the handle, I saw myself too obliged to continue to take an interest in them, to occupy myself with their affairs. There came back to me also the threats, the fierce protestations of the Nestoroff, that she feared nothing from any man, Because any other evil–a fresh crime, imprisonment, death itself–she would reckon as less than the evil which she was suffering in secret and preferred to endure. Had she perhaps suddenly grown tired of enduring it? Could this be the reason of her deciding yesterday, during my absence, to take the first step towards Nuti, in contradiction of what she had said to me the day before?

“No pity,” she had said to me, “neither for myself nor for him!”

Had she suddenly felt pity for herself? Not for him, certainly! But pity for herself means to her extricating herself by any means in her power, even at the cost of a crime, from the punishment she has inflicted on herself by living with Carlo Ferro. Suddenly making up her mind, she has gone to meet Nuti and has made Carlo Ferro return.

What does she want? What is going to happen next?

This is what happened, in the meantime, at midday beneath the pergola of the tavern, where–dressed some of them as Indians and others as English tourists–a crowd of actors and actresses from the four companies had assembled. All of them were or pretended to be infuriated and upset by Commendator Borgalli’s outburst that morning, and had for some time been taunting Carlo Ferro, letting him clearly understand that they were indebted to him for that outburst, he having first of all advanced all those silly claims and then tried to back out of the part allotted to him in the tiger film, and having left Rome, as though there were really a great risk attached to the killing of an animal cowed by all those months of captivity: an insurance for one hundred thousand lire, agreements, conditions, etc. Carlo Ferro was seated at a table, a little way off, with the Nestoroff. His face was yellow; it was quite evident that he was making an enormous effort to control himself; we all expected him at any moment to break out, to turn upon us. We were, therefore, left speechless at first when, instead of him, another man, to whom no one had given a thought, broke out all of a sudden and turned upon him, going up to the table at which Ferro and the Nestoroff were sitting. It was he, Nuti, as pale as death. In a silence that throbbed with a violent tension, a faint cry of terror was heard, to which Varia Nestoroff promptly replied by laying her hand, imperiously, upon Carlo Ferro’s arm.

Nuti said, looking Ferro straight in the face:

“Are you prepared to give up your place and your part to me? I promise before everyone here to take it on unconditionally.”

Carlo Ferro did not spring to his feet nor did he fly at the tempter. To the general amazement he sank down, sprawled awkwardly in his chair; leaned his head to one side, as though to look up at the speaker, and before replying raised the arm upon which the Nestoroff’s hand was resting, saying to her:

“Please….”

Then, turning to Nuti:

“You? My part? Why, I shall be delighted, my dear Sir. Because I am a fearful coward … you wouldn’t believe how frightened I am.

Delighted, my dear Sir, delighted!”

And he laughed, as I never saw a man laugh before!

His laughter made us all shudder, and, what with this general shudder and the whiplash of his laughter, Nuti was left quite helpless, his mind certainly vacillating from the impulse which had driven him to face his rival and had now collapsed, in the face of this awkward and teasingly submissive reception. He looked round him, and then, all of a sudden, at the sight of that pale, puzzled face, everyone began to laugh at him, broke into peals of loud, irrepressible laughter. The painful tension was broken in this way, in this enormous laugh of relief, at the challenger’s expense. Exclamations of derision sounded here and there, like jets of water amid the clamour of the laughter: “He’s cut a pretty figure!” “Caught in the trap!” “Like a mouse!”

Nuti would have done better to join in the laughter as well; but, most unfortunately, he chose to persist in the ridiculous part he had adopted, looking round for some one to whom he might cling, to keep himself afloat in this cyclone of hilarity, and stammered:

“Then… then, you agree?… I am to play the part… you agree!”

But even I myself, however reluctantly, at once took my eyes from him to look at the Nestoroff, whose dilated pupils gleamed with an evil light.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (32)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XI

Toen de oude man over partizanen begon te praten, had de chauffeur zich teruggetrokken, was achter zijn stuurrad gaan zitten en bracht de bus weer op gang. Durfde niets meer tegen de oude man te zeggen over boete. Er staat boete op het trekken aan een noodrem! En de betrokken passagier moest dan de bus uit. De chauffeur beperkte zich tot het herstellen van de oude toestand, de bus voort te bewegen over de weg, langs de rivier het Lange Rak, tussen Tepple en Wrak. En voor de rest zijn mond te houden. Hij was een van die partizanen. Durfde er nu niet meer voor uit te komen. Hoewel hij met doodsverachting partizaan was geweest. Partizanen vochten voor eerlijkheid en recht. Maar recht bestond niet en eerlijk was geen mens. De partizanen vochten dus zo maar wat, voor een onduidelijk doel. Een van de legers won, het andere verloor, dat was oorlog. Partizanen hoorden bij geen leger. Ze lieten alle soorten soldaten en burgers de lucht in vliegen. Dat werd weer bewezen door de oude man met de nek vol littekens die aan de noodrem had getrokken om even te zeggen dat er geen recht was en dat er oorlog was geweest en ook dat er al vrede was in oorlogstijd.

De bus reed verder, maar iedereen had een hart vol wrok. Iedereen had zo zijn gedachten over de oorlog. Misschien hadden die en die nog geleefd als er geen partizanen geweest waren. Maar dat was eigenlijk ook weer geen redenering voor mensen die stiekem geloofden in voorbeschikking van leven en dood door de Almachtige Schepper.

Ik telde niet hoeveel mensen er onderweg in- en uitstapten. Merkte wel dat veel mensen de bus al verlieten in Tepple. In Wrak stapte niemand uit. Wrak was één grote puinhoop, terwijl er enkel vredelievende soldaten gehuisvest waren geweest. Alleen God woonde nog in Wrak. De kerk en de toren waren om en op het altaar neergestort. God woonde in een ruïne.

Tot nu toe had niemand kans gezien de kelken en monstransen uit het tabernakel te halen. Heel Wrak was één puinhoop. Daar hoeft niemand heen met de bus. Daar komt niemand uit. En niemand wil erin. De bus hoefde er dus niet te stopppen. En God reist niet met de bus. Maar de bus was dat stoppen nog gewend uit de oorlog. Per slot van rekening was het een frontbus geweest.

In Borz woonden niet meer mensen dan in Oeroe. Alleen waren de mensen van Borz niet zo melancholiek als die van Oeroe. Er liep dan ook geen waterader onder Borz.

De brug van Borz was een noodbrug. Hoog ijzerwerk waarop je met gemak een dak zou kunnen leggen. Nu waren het hoge turnrekken. Alleen vogels konden er in turnen.

In Boeroe koesterden de mensen openlijk haat tegen die van Oeroe. Er liepen er heel wat rond met hun koppen in wit gaasverband, omdat er kermis was in Oeroe.

We reden Oeroe binnen. Passeerden de woonwagen van Cherubijn. Cherubijn zat in de deuropening. De marmot zag ik niet. Cherubijn zag mij niet. Hij hield net zijn hoofd met de luie nekspieren naar de andere kant. Kon niet tijdig zijn hoofd omdraaien om de bus te zien.

De bus hield stil op de markt. Ik holde naar de wagen.

Cherubijn was blij toen hij me zag, ging in halsbrekende standen staan om mij beter te zien en om zijn nekspieren te laten rusten. En hij wilde weten waar ik was geweest. Dat verzweeg ik.

Ik ging in het gras liggen. Speelde met de marmot die naar me toe kwam en tussen mijn benen wilde gaan liggen. Hij was dat al gewend in één nacht. Zo snel kun je een marmot iets leren.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

In a Boat

See the stars, love,

In the water much clearer and brighter

Than those above us, and whiter,

Like nenuphars.

Star-shadows shine, love,

How many stars in your bowl?

How many shadows in your soul,

Only mine, love, mine?

When I move the oars, love,

See how the stars are tossed,

Distorted, the brightest lost.

—So that bright one of yours, love.

The poor waters spill

The stars, waters broken, forsaken.

—The heavens are not shaken, you say, love,

Its stars stand still.

There, did you see

That spark fly up at us; even

Stars are not safe in heaven.

—What of yours, then, love, yours?

What then, love, if soon

Your light be tossed over a wave?

Will you count the darkness a grave,

And swoon, love, swoon?

D.H. Lawrence poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Voeu

Si j’étais la feuille que roule

L’aile tournoyante du vent,

Qui flotte sur l’eau qui s’écoule,

Et qu’on suit de l’oeil en rêvant ;

Je me livrerais, fraîche encore,

De la branche me détachant,

Au zéphyr qui souffle à l’aurore,

Au ruisseau qui vient du couchant.

Plus loin que le fleuve, qui gronde,

Plus loin que les vastes forêts,

Plus loin que la gorge profonde,

Je fuirais, je courrais, j’irais !

Plus loin que l’antre de la louve,

Plus loin que le bois des ramiers,

Plus loin que la plaine où l’on trouve

Une fontaine et trois palmiers ;

Par delà ces rocs qui répandent

L’orage en torrent dans les blés,

Par delà ce lac morne, où pendent

Tant de buissons échevelés ;

Plus loin que les terres arides

Du chef maure au large ataghan,

Dont le front pâle a plus de rides

Que la mer un jour d’ouragan.

Je franchirais comme la flèche

L’étang d’Arta, mouvant miroir,

Et le mont dont la cime empêche

Corinthe et Mykos de se voir.

Comme par un charme attirée,

Je m’arrêterais au matin

Sur Mykos, la ville carrée,

La ville aux coupoles d’étain.

J’irais chez la fille du prêtre,

Chez la blanche fille à l’oeil noir,

Qui le jour chante à sa fenêtre,

Et joue à sa porte le soir.

Enfin, pauvre feuille envolée,

Je viendrais, au gré de mes voeux,

Me poser sur son front, mêlée

Aux boucles de ses blonds cheveux ;

Comme une perruche au pied leste

Dans le blé jaune, ou bien encor

Comme, dans un jardin céleste,

Un fruit vert sur un arbre d’or.

Et là, sur sa tête qui penche,

Je serais, fût-ce peu d’instants,

Plus fière que l’aigrette blanche

Au front étoilé des sultans.

uit: Victor Hugo, Les orientales

Hans Hermans Natuurdagboek september 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD X

Het rook allesbehalve fris in de bus. Een lucht van oude vrouwen, stof en papieren zakken met inhoud uit de winkels van de voor goed geld vrijgevige Lichtstad Kork. En naar benzine stonk het.

De chauffeur van de bus had een grof belijnd gezicht. Niet opvallend. Eerder gewoon. Toch had het iets verschrikkelijks. Er hing iets dreigends in de bus. Iets dat terug was te brengen tot de grove lijnen in het gezicht van de chauffeur. Er past veel in de grove lijnen van een chauffeursgezicht. Nee, ik had er geen behoefte aan gezichten te zien.

De bus trok hortend op. Leek de motor te verliezen. Wat helemaal niet zo’n bezwaar was. Van Kork naar Oeroe daalde de weg aan één stuk door zodat de bus er toch wel zou komen. Het zou wel bezwaarlijk worden op de terugweg. Ik heb meegemaakt dat de bus van Oeroe tot Kork in de eerste versnelling reed. Of er wat haperde aan de versnellingsbak wist ik niet. Het gaf te denken over de toestand en het onderhoud van de bus. En over het sterke stijgen van de weg. Zou de bus haar route hebben langs het Woud van Tubbs, dan zou ze in zo’n korte tijd niet zo sterk hoeven te stijgen.

Voor me zat een wat oudere man. Hij had een vuile nek. Veel oudere mannen hebben dat. Blijkbaar zijn hun armen tekort geworden om tot hun nek te reiken. Voortdurend neuriede de man. Hij had littekens in zijn nek. Had dus eerder in deze bus gezeten. Was als gewonde van het front gehaald door deze bus. Had aan de bus zijn leven te danken. Bleef uit dank op en neer rijden tussen Kork en Oeroe.

We waren Tepple al gepasseerd. Het Tepple van de forensen en van de nazaten van een of ander soort adel. Of adel te verdienen viel door van iemand af te stammen! Alsof dat respect verdiende! Er waren wat misverstanden in de wereld!

We reden langs het Lange Rak, richting Wrak, toen de oude man aan de noodrem trok. Met een schok stond de bus stil. Ze was dat nog gewend uit de oorlog. De chauffeur was wit van woede. Er was geen aanleiding om aan de noodrem te trekken. Er waren voorschriften voor een noodrem in een bus. De chauffeur kende ze nauwelijks. Van het publiek werd wel verlangd dat het deze voorschriften kende. Er was geen aanleiding. Niemand was aangereden. Ook waren we geen halte voorbijgereden zonder te stoppen. Er liep geen vee over de weg. Niemand was bezweken aan het gerammel van de bus. Toch had de man het nodig gevonden aan de noodrem te trekken.

De chauffeur liep naar de man toe. Driftig.

‘Eruit! De bus uit. Voorschriften zijn er niet om ermee te spotten.’

‘Ja,’ zei de man, ‘ik weet het wel, maar hier is het gebeurd! Hier was het front! Die van ons lagen tot aan Tepple en die van de andere vaderlanden hielden alles tot en met Borz en Wrak bezet. Hier tussen Tepple en Wrak was het front.’ Hij wees met een vaag armgebaar naar de heuvels, het Lange Rak en de huizen langs de rivier. ‘Dat was het front. Hier is het gebeurd,’ zei de man. ‘Toch was het een rustig front tussen Tepple en Wrak. Het landschap was te mooi. De soldaten werden hier rustig. Ze begrepen niets meer van het moorden. Ze beperkten zich ertoe elkaar te bespioneren langs de rivier en in de huizen langs het Lange Rak. Soms dronken ze met elkaar. Alleen de partizanen hadden geen respect voor het front. Ze groeven landmijnen in de wegen. Toen ik hier langskwam, verkleed als burger, om eens te gaan horen wat de vijandelijke soldaten van de vrede dachten, vloog ik de lucht in.’

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD IX

In sommige kringen ging de vreemde uitspraak dat mierrijden dierenmishandeling zou zijn. Dat sloeg natuurlijk op het doden van de beestjes nadat ze over een afstand van dertig centimeter bereden waren. Dat was geen mishandeling! Deze mieren werden bevrijd uit hun gareel. Ze hoefden niet meer in de trein te lopen die, dag in, dag uit, het hol uitkroop en zand vervoerde. Korrels zand die ze nauwelijks konden dragen met hun haarfijne voorpootjes. Trouwens, in de oorlog zag je andere dingen. Ik heb gezien dat mensen elkaar neerschoten. Ze bleven liggen op straat. Ze waren van een ander vaderland. Welk land wist geen hond, want geen mens was er ooit geweest. Soms waren ze gewond. Niemand keek naar hen om. Niemand keek in hun van pijn vertrokken gezicht. Zo’n gezichten waren in die tijd gewoon. Het was voor de eer van vorst en vaderland. Ieder liet hen liggen, bang voor eigen hachje. Toch lag niemand de woorden ‘voor vorst en vaderland’ bestorven op de lippen. Degenen die daar lagen te sterven, konden een schop krijgen. Die waren van een ander vaderland. Dat telde niet.

Oorlog was net een stiekem spelletje. Het spelletje van leven en dood. Zoiets als pandverbeuren. Dit telt niet en dat telt niet. Ik zet deze helm op en jij die. Ik heb mijn vaderland achter mijn rug. Jij hebt jouw vaderland achter jouw rug. We proberen elkaar te vermoorden. We vechten voor een waardeloze vlag. Voor de eer van een regiment. Voor de versleten banier van God. Wanneer de waarden gekelderd zijn, wanneer God vermoord is, geven we elkaar de hand. De een druipt van het bloed van de ander. Godnogtoe, laat mierrijden mierrijden blijven!

Er stonden weinig mensen bij de bushalte. Enkele vrouwen met uitpuilende tassen. Een oudere heer met een hond die voortdurend zijn poot optilde tegen de paal van de bushalte en die me netjes goedendag blafte. Ik moest wachten. Ik had een hekel aan wachten. De vrouwen met de tassen niet. Die hadden de tijd. Die wachtten niet. Die stonden er alleen maar om het staan. Die dachten: zo en zo laat vertrekt de bus. Eerder vertrekken we lekker niet. Zo lang mogen we hier nog blijven staan. Lekker, met volle tassen in de hand. Het is prettig volle tassen in de hand te hebben. Zo lang hebben we geen honger. We zijn de oorlog nog lang niet vergeten. Gewone mensen vergeten niet zo gauw!

De man wachtte ook niet. Die stond er alleen voor de hond. Die man hoefde helemaal niet met de bus mee. Alleen de hond moest naar de bus kijken, zijn poot opheffen tegen de haltepaal en mij goedendag blaffen.

Eindelijk kwam de bus. Ze stamde nog uit de oorlog. Was haar carrière begonnen als frontbus. Bracht soldaten naar het front. Haalde lijken en gewonden naar huis. Nu reed ze van de Lichtstad Kork naar Oeroe, kwam nooit langs het Woud van Tubbs, wel over de brug van Kork, reed door het forensenplaatsje Tepple, langs het Lange Rak naar Gretz, deed daarna nog Wrak en Borz aan, stak de brug over bij Borz, bereikte over Boeroe Oeroe en reed de hele weg terug. In nog steeds dezelfde kleur als frontbus. Met hetzelfde gemis aan boslucht uit het Woud van Tubbs. Net als al de andere keren dat ze de reis begonnen was en beëindigd had.

Ik stapte in. Betaalde niet. Ik had vrij vervoer. In die tijd hadden kinderen tot zes jaar vrij reizen. Ik ging achter in de bus zitten. Vandaar kon ik alles overzien en was ik aan niemand iets schuldig. Je was aan iemand iets schuldig in de bus als je zou moeten omkijken om zijn gezicht te zien. Ik kon geen van de gezichten zien. Iedereen zat met de rug naar me toe. Hoogstens één kant van de gezichten kon ik onduidelijk zien spiegelen in de vuile ruiten. Ik had er geen behoefte aan om gezichten te zien.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Gustave Flaubert

(1821-1880)

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (G)

G

GAGNE-PETIT: Belle enseigne pour une boutique, comme inspirant la confiance.

GAIETÉ: Toujours accompagnée de folle.

GALANT HOMME: Suivant les circonstances prononcer galantuomo ou gentleman.

GALBE: Dire devant toute statue qu’on examine: «Ca manque de galbe.»

GALETS: Il faut en rapporter de la mer.

GALLOPHOBE: Se servie de cette expression en parlant des journalistes allemands.

GAMIN: Toujours de Paris. Ne jamais laisser sa femme dire: «Quand je suis gaie, j’aime à faire le gamin.»

GANTS: Donnent l’air comme il faut.

GARDE: La garde meurt et ne se rend pas! Huit mots pour remplacer cinq lettres.

GARDE-COTE: Ne jamais employer cette expression au pluriel en parlant des seins d’une femme.

GARES de chemin de fer: S’extasier devant elles et les donner comme modèles d’architecture.

GAUCHERS: Terribles à l’escrime. Plus adroits que ceux qui se servent de la main droite.

GENDARME: Rempart de la société.

GENDARMERIE: Dites: force publique ou maréchaussée.

GENDRE: Mon gendre, tout est rompu!

GÉNÉRATION SPONTANÉE: Idée de socialiste.

GÉNÉRAL: Est toujours brave. Fait généralement ce qui ne concerne pas son état, comme être ambassadeur, conseiller municipal ou chef de gouvernement.

GÉNIE (le): Inutile de l’admirer, c’est une «névrose»

GENOVEFAIN: On ne sait pas ce que c’est.

GENRE ÉPISTOLAIRE: Genre de style exclusivement réservé aux femmes.

GENTILHOMME: Il n’y en a plus.

GÉOMÈTRE: «Nul n’entre ici s’il n’est géomètre.»

GIAOUR: Expression farouche, d’une signification inconnue, mais on sait que ça se rapporte à l’Orient.

GIBELOTTE: Toujours faite avec du chat.

GIBERNE: Etui pour bâton de maréchal de France.

GIBIER: N’est bon que faisandé.

GIRAFE: Mot poli pour ne pas appeler une femme chameau.

GIRONDINS: Plus à plaindre qu’à blâmer.

GLACES: Il est dangereux d’en prendre.

GLACIERS: Tous Napolitains.

GLÈBE (la): S’apitoyer sur la glèbe.

GLOBE: Mot pudique pour désigner les seins d’une femme. «Laissez- moi baiser vos globes adorables.»

GLOIRE: N’est qu’un peu de fumée.

GLORIA: Un gloria ne marche jamais sans sa consolation.

GOBELINS (tapisserie des): Est une oeuvre inouïe et qui demande cinquante ans à finir. S’écrier devant: «C’est plus beau que la peinture!» L’ouvrier en sait pas ce qu’il fait.

GODDAM: «C’est le fond de la langue anglaise» , comme disait Beaumarchais, et là-dessus on ricane de pitié.

GOD SAVE THE KING: Chez Béranger se prononce «God savé te King» et rime avec sauvé, préservé…

GOG: Toujours suivi de Magog.

GOMME ÉLASTIQUE: Est faite avec le scrotum de cheval.

GOTHIQUE: Style d’architecture portant plus à la religion que les autres.

GOURMÉ: Toujours précédé de raide.

GOÛT: Ce qui est simple est toujours de bon goût. Doit toujours se dire à une femme qui s’excuse de la modestie de sa toilette.

GRAMMAIRE: L’apprendre aux enfants dès le plus bas âge comme étant une chose claire et facile.

GRAMMAIRIENS: Tous pédants.

GRAS: Les personnes grasses n’ont pas besoin d’apprendre à nager. Font le désespoir des bourreaux parce qu’elles offrent des difficultés d’exécution. Ex.: la Du Barry.

GRÊLÉ: Les femmes grêlées sont toutes lascives.

GRENIER: On y est bien à vingt ans!

GRENOUILLE: La femelle du crapaud.

GRISETTES: Il n’y a plus de grisettes. Cela doit être dit avec l’air déconfit du chasseur qui se plaint qu’il n’y a plus de gibier.

GROG: Pas comme il faut.

GROTTES À STALACTITES: Il y a eu dedans une fête célèbre, bal ou souper, donné par un grand personnage. On y voit «comme des tuyaux d’orgue» . On y a dit la messe pendant la Révolution.

GROUPE: Convient sur une cheminée et en politique.

GUÉRILLA: Fait plus de mal à l’ennemi que l’armée régulière.

GUERRE: Tonner contre.

GULF-STREAM: Ville célèbre de Norvège, nouvellement découverte.

GYMNASE (le): Succursale de la Comédie-Française.

GYMNASTIQUE: On ne saurait trop en faire. Exténue les enfants.

Gustave Flaubert

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (G)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

![]()

Harriet Laurey

(1924–2004)

Vlakbij je hart

Vlakbij je hart moet ik soms denken aan

het droefste liefs, en kan het niet vertellen,

maar uit mijn donker schokt het zich vandaan,

zo driftig en gehaast als waterbellen.

Ik lig het bijna, bijna te verstaan,

met open mond, om het langzaam te spellen.

Maar wat ik zeggen kan, is zo gering,

bij ’t onuitsprekelijke vergeleken,

dat ik weer stil word van verwondering.

En als ik zo lang naar je heb gekeken,

dat alle woorden zijn teruggeweken,

weten mijn lippen maar van: lieveling…

(uit: Loreley, 1952)

Harriet Laurey poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Brabantia Nostra

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

The Almond Tree

(Letter from Town)

You promised to send me some violets. Did you forget?

White ones and blue ones from under the orchard hedge?

Sweet dark purple, and white ones mixed for a pledge

Of our early love that hardly has opened yet.

Here there’s an almond tree—you have never seen

Such a one in the north—it flowers on the street, and I stand

Every day by the fence to look up for the flowers that expand

At rest in the blue, and wonder at what they mean.

Under the almond tree, the happy lands

Provence, Japan, and Italy repose,

And passing feet are chatter and clapping of those

Who play around us, country girls clapping their hands.

You, my love, the foremost, in a flowered gown,

All your unbearable tenderness, you with the laughter

Startled upon your eyes now so wide with hereafter,

You with loose hands of abandonment hanging down.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD VIII

Meneer Weber bood me een stoel aan. Een veel te hoge stoel, maar passend met de verhoudingen van het vertrek. Vanaf de stoel keek ik in een afgesloten tuin waarin de mensen van Kork nooit kwamen. Die tuin bleef voorbehouden aan de burgemeester, zijn eventuele vrouw en zijn eventuele kinderen. Er bloeiden grote rododendronstruiken in die tuin. Achterin was een pergola waarvoor een fontein sproeide, zo vrolijk dat ik het vooroorlogs noem. Toentertijd schenen het frisse en vrolijke iets met de tijd van voor de oorlog te maken te hebben. Het water viel in een vijver waarin zeker vissen zouden zitten. De pergola werd gevormd door grote bogen van rode stokrozen. Ze bloeiden waarschijnlijk het hele jaar door, zonder acht te slaan op de winter.

Meneer Weber nam plaats achter een bureau, bladerde zo maar wat door een stapel paperassen. Er klopte iemand op de deur. De huisknecht kwam binnen en vroeg onderdanig naar de verlangens van de heer Weber. Die verlangens bestonden uit een kop koffie voor de heer Weber en een glas limonade voor mij. De man verdween en kwam vlugger terug dan ik verwachtte. Blijkbaar had hij de bestelling van de heer Weber al klaarstaan.

Meneer Weber zette muziek op. Zarah Leander en consorten. Veel te vroeg wakker geweest. Slaapdronken in de studio aangekomen en daar plaatjes gemaakt. Zoveel plaatjes op een dag. Is zoveel verdiend in de week. Maakt een kapitaal per jaar. Arm als je doodgaat. Arme Zarah en consorten. Wat zong ze mooi. Ach, wat zong ze mooi.

Er ging me een licht op. Bij een man als Weber moest wat te bereiken zijn. Zo’n man zou wat kunnen doen. Hij zou mijn ouwe bok Kaïn kunnen laten opsluiten. De Gore Kana zou hij voorgoed in een gesticht voor vuile wijven kunnen duwen. Wat nog te goed zou zijn voor de Gore Kana. Toen we er later over praatten bleek dat hij, net als ik, mensen als Kaïn en de Gore Kana haatte.

Ik vertelde Weber over Cherubijn. Hij had geen medelijden, maar was wel bereid het te tonen.

Ik had een plan. Cherubijn zou met zijn wagen naar Kork rijden. Hij zou er geen standplaats krijgen, maar omdat hij in Kork wilde blijven zou de burgemeester hem een huis toewijzen. Zelfs de burgemeester vond het een goed plan.

Later wilde meneer Weber me naar Oeroe terugbrengen, maar ik ging liever met de bus. Er liep toentertijd nog een bus naar Oeroe. Die maakte een omweg. Ze kwam niet langs het Woud van Tubbs. Integendeel. Ze reed de brug over vóór Kork, deed Tepple aan, de plaats waar de forensen uit de Lichtstad Kork wonen, reed dan langs het Lange Rak naar Gretz, deed daarna nog Wrak en Borz aan, reed over de brug bij Borz en bereikte via Boeroe Oeroe. Vanuit Oeroe maakte ze dezelfde reis terug, over dezelfde weg, zodat ze nooit langs het Woud van Tubbs kwam. Nooit had de bosverzadigde lucht uit het Woud van Tubbs door de open ramen de bus in kunnen stromen.

Ik liep door de straten van Kork naar de bushalte. Ik lette op politie. Ik wist niet of er naar mij werd gezocht. Misschien had mijn ouwe bok Kaïn wroeging gekregen. Hij zou me kunnen laten opsporen. En het was een fout van de politie om me alleen op de hei te laten zitten. De politie diende te weten dat een jongetje op de hei niets te zoeken had. Dat was de algemene regel. Ze wisten niets over mijn bekwaamheden inzake het mierrijden. Zou het hun interesseren?

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature