Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD IV

Hij heette niet Cherubijn.

Hij heette Jonas Uit De Walvis en was in de oorlog beschadigd. Later heb ik het hem weleens horen vertellen. Beschadigd in een tank die was getroffen door een anti-tankbrisantgranaat. Hij was door het luikje van de tank naar buiten gevlogen. De vijand – dat is nu onze vriend – had hem voor lijk laten liggen. Als ze geweten hadden dat hij toen nog leefde, hadden ze wel de moeite genomen om even een bajonet door zijn lijf te rammen.

Hij was dus Jonas Uit De Walvis en kon van geluk spreken. Wat hij niet deed. Het was hem eender om voort te leven of in de tank het leven gelaten te hebben voor een onbekende vorst en een onduidelijk vaderland.

Na een minuut zag hij mij. Grimlachte. Heel anders dan mijn ouwe bok Kaïn. Die glimlachte. Cherubijn gaf me een hand en zei: ‘Kom.’

We gingen naar zijn woonwagen. Ik kreeg een marmot in mijn armen gedrukt. Daarna gingen we naar de cafés. Cherubijn zoop met die van Oeroe en Boeroe mee en liet mij geld verdienen door met de marmot langs de tafels te leuren en treurig te kijken.

Toch was ik niet treurig. Eerder blij. Dit was het echte leven. Nu zou ik mensen zien. Dag aan dag cafés ruiken. En bier drinken uit halfvolle glazen omdat de lui liever een dronken jongetje zagen dan een nuchter marmotje.

Die avond verdiende ik veel geld, vooral dubbeltjes en kwartjes, maar toen Cherubijn zijn rekening had betaald, was er niet veel meer over. Jammer, van het geld had ik de volgende dag eten willen kopen.

Het woonwagentje van Cherubijn was oud en gammel. Er was één bed. Dus sliep ik in de mand van de marmot. Er was voor het kleine beest nog ruimte genoeg om tussen mijn benen te liggen. Wat hem blijkbaar beviel. Ik heb hem nooit kunnen betrappen op pogingen om van die plaats weg te komen.

Het stonk in de wagen naar een of ander zuur. Ik nam me voor de volgende dag grote schoonmaak te houden. De vloer te boenen, de stoel, de slaapmand, het bed en het komfoor. En het grote oog van God dat lichtgevend was, boven de deur hing en de enige versiering in de wagen bleek, zodat het iedereen opviel die binnenkwam. Het bespaarde Cherubijn veel last. Wie was er niet bang voor het lichtgevende oog van God?

De eerste uren kon ik niet goed slapen. Het moest nog wennen om in een mand te liggen met een marmot tussen de benen. Ik dacht nog aan Kaïn en Kana die nu in een cel zouden zitten. Voor de zoveelste maal ontluisd en ingepoederd met DDT. En geregeld geranseld werden omdat ze ontucht hadden gepleegd in de vrije natuur. Nota bene in het gezelschap van een kind. De politie kon niet weten dat het mij weinig deed. Ik had alleen afkeer van het vuile lijf van de Gore Kana en van de harde billen van Kaïn.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

![]()

Harriet Laurey

(1924–2004)

Uiteindelijk

Blijf nu voorgoed in mij gestorven;

want dit is een onschendbaar graf.

Ik heb U eindelijk verworven.

Ik sta U niet meer af.

Houd nu voorgoed Uw oog gesloten

over het laatst-gespiegeld beeld,

dat op Uw netvlies ligt gebroken

en niet meer heelt.

Mijn aarde streelt U overal.

Mijn diepte vult zich met Uw droom,

– Uw wezen, eindelijk verlost -,

die ik eenmaal vertalen zal

in liefde’s teder idioom:

gras, bloemen, vochtig mos.

(uit: Triple alliantie, 1951)

Harriet Laurey poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Brabantia Nostra

George Sand

(1804-1876)

À Aurore

La nature est tout ce qu’on voit,

Tout ce qu’on veut, tout ce qu’on aime.

Tout ce qu’on sait, tout ce qu’on croit,

Tout ce que l’on sent en soi-même.

Elle est belle pour qui la voit,

Elle est bonne à celui qui l’aime,

Elle est juste quand on y croit

Et qu’on la respecte en soi-même.

Regarde le ciel, il te voit,

Embrasse la terre, elle t’aime.

La vérité c’est ce qu’on croit

En la nature c’est toi-même.

George Sand poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, George Sand

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD III

CHERUBIJN

Voortaan zou ik alleen door de wereld gaan.

Vluchten noemde ik het niet. Aan mij zag trouwens niemand dat ik er vandoor ging. Nog minder voor wie of voor wat ik vluchtte. Ik kon overal naar- toe. De meeste mensen lachten naar me en dachten: dat jongetje loopt een eindje om. Soms zei er een: ‘Kijk, kijk, daar hebben we de jonge heer Kaïn. Hij gaat op stap. Hij heeft een aardje naar zijn vaartje.’ Maar hoe kon ik, zo jong nog, op mijn ouwe bok Kaïn lijken die al zestig was geweest en die nogal last had van de jeugdige neiging tot overdrijven?

Tegen de avond kwam ik aan in het dorp Boeroe. De mensen van het dorp waren niet thuis. Ze waren naar de kermis in Oeroe. Boeroe hoorde tot de gemeente Oeroe. Men zoop er, nog net zo hard als voor de oorlog, zoals de mensen het uitdrukten. Ze zopen zoals ik het vaak mijn ouwe bok Kaïn had zien doen. Tot aan het delirium zuipen en dan ophouden. Op het randje van de volslagen waanzin ophouden uit een redelijke overweging. De wens om langer te leven of zo. Dat zou een wens kunnen zijn van mensen die vijf jaar of langer met de dood op de hielen hadden gelopen. Het was belachelijk, maar dat wist ik toen nog niet.

Dus liep ik door naar Oeroe. Op het kermisplein stond een hoge draaimolen. De witte paarden die vastgeschroefd waren aan het plankier, werden dol van het draaien. Het was goed te zien. Hun uit hout gesneden tongen hingen klaaglijk uit hun bekken. Ze leken levenloos, maar ik wist dat ze leefden onder hun houten pantser en dat ze blij zouden zijn als de kinderen van Oeroe en Boeroe naar bed werden gebracht zodat die hen niet meer konden geselen met hun venijnige handjes.

Ook stond er een zweefmolen waarin jongelui op vrijersleeftijd, in stoeltjes die aan kettingen hingen, grote bogen langs de hemel trokken. De meisjes wapperden luid met hun kleren. De jongens lachten grollig en boers om ingehouden grappen, trokken de meisjes aan hun rokken, probeerden hen achter in hun nek te zoenen.

Daar zag ik Cherubijn.

Hij had een houten poot en zag eruit als een piraat.

Hij was duidelijk jaloers op de jeugd die hoog boven ons rondcirkelde. Of er geen groter genot bestond dan in een bijna horizontale toestand in rondjes over de aarde te scheren, het hele kermisterrein te overschouwen, in cafés binnen te kijken, heel vluchtig over de daken te reiken en soms de lichten te zien van de dorpen als Borz en Gretz. Misschien zelfs van de Lichtstad Kork.

Daar stond mijn zoveelste vader!

Cherubijn.

Veel schoner dan mijn ouwe bok Kaïn was hij niet. Dat kwam door zijn gebreken. Behalve zijn houten poot was het hem onmogelijk zijn rechterarm te bewegen. En zijn hoofd reageerde niet op commando’s die door de hersens via prikkelingen in het centrale zenuwstelsel gegeven werden, maar wel op bevelen die ergens uit zijn lijf kwamen. Misschien uit zijn mond, misschien uit zijn hart. Zijn zenuwen hadden het in de buurt van zijn nekspieren laten afweten. Daarom bleef hij nog een minuut of wat naar de jeugd boven ons hoofd kijken terwijl hij zich al inspande naar beneden te kijken nadat ik hem aangestoten had en gezegd had: ‘Dag Cherubijn.’

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (29)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

2

A note from the Nestoroff, this morning at eight o’clock (a sudden and mysterious invitation to call upon her with Signorina Luisetta on our way to the Kosmograph), has made me postpone my departure.

I remained standing for a while with the note in my hand, not knowing what to make of it. Signorina Luisetta, already dressed to go out, came down the corridor past the door of my room; I called to her.

“Look at this. Read it.”

Her eyes ran down to the signature; as usual, she turned a deep red, then deadly pale; when she had finished reading it, she fixed her eyes on me with a hostile expression, her brow contracted in doubt and alarm, and asked in a faint voice:

“What does she want?”

I waved my hands in the air, not so much because I did not know what answer to make as in order to find out first what she thought about it.

“I am not going,” she said, with some confusion. “What can she want with me?”

“She must have heard,” I explained, “that he … that Signor Nuti is staying here, and…”

“And?”

“She may perhaps have some message to give, I don’t know… for him.”

“To me?”

“Why, I imagine, to you too, since she asks you to come with me….”

She controlled the trembling of her body; she did not succeed in controlling that of her voice:

“And where do I come in?”

“I don’t know; I don’t come in either,” I pointed out to her. “She wants us both….”

“And what message can she have to give me … for Signor Nuti?”

I shrugged my shoulders and looked at her with a cold firmness to call her back to herself and to indicate to her that she, in so far as her own person was concerned–she, as Signorina Luisetta, could have no reason to feel this aversion, this disgust for a lady for whose kindness she had originally been so grateful.

She understood, and grew even more disturbed.

“I suppose,” I went on, “that if she wishes to speak to you also, it will be for some good purpose; in fact, it is certain to be. You take offence….”

“Because… because I cannot… possibly … imagine…” she broke out, hesitating at first, then with headlong speed, her face catching fire as she spoke, “what in the world she can have to say to me, even if, as you suppose, it is for a good purpose. I…”

“Stand apart, like myself, from the whole affair, you mean?” I at once took her up, with increasing coldness. “Well, possibly she thinks that you may be able to help in some way….”

“No, no, I stand apart; you are quite right,” she hastened to reply, stung by my words. “I intend to remain apart, and not to have anything to do, so far as Signor Nuti is concerned, with this lady.”

“Do as you please,” I said. “I shall go alone. I need not remind you that it would be as well not to say anything to Nuti about this invitation.”

“Why, of course not!”

And she withdrew.

I remained for a long time considering, with the note in my hand, the attitude which, quite unintentionally, I had taken up in this short conversation with Signorina Luisetta.

The kindly intentions with which I had credited the Nestoroff had no other foundation than Signorina Luisetta’s curt refusal to accompany me in a secret manoeuvre which she instinctively felt to be directed against Nuti. I stood up for the Nestoroff simply because she, in inviting Signorina Luisetta to her house in my company, seems to me to have been intending to detach her from Nuti and to make her my companion, supposing her to be my friend.

Now, however, instead of letting herself be detached from Nuti, Signorina Luisetta has detached herself from me and has made me go alone to the Nestoroff. Not for a moment did she stop to consider the fact that she had been invited to come with me; the idea of keeping me company had never even occurred to her; she had eyes for none but Nuti, could think only of him; and my words had certainly produced no other effect on her than that of ranging me on the side of the Nestoroff against Nuti, and consequently against herself as well.

Except that, having now failed in the purpose for which I had credited the other with kindly intentions, I fell back into my original perplexity and in addition became a prey to a dull irritation and began to feel in myself also the most intense distrust of the Nestoroff. My irritation was with Signorina Luisetta, because, having failed in my purpose, I found myself obliged to admit that she had after all every reason to be distrustful. In fact, it suddenly became evident to me that I only needed Signorina Luisetta’s company to overcome all my distrust. In her absence, a feeling of distrust was beginning to take possession of me also, the distrust of a man who knows that at any moment he may be caught in a snare which has been spread for him with the subtlest cunning.

In this state of mind I went to call upon the Nestoroff, unaccompanied. At the same time I was urged by an anxious curiosity as to what she would have to say to me, and by the desire to see her at close quarters, in her own house, albeit I did not expect either from her or from the house any intimate revelation.

I have been inside many houses, since I lost my own, and in almost all of them, while waiting for the master or mistress of the house to appear, I have felt a strange sense of mingled annoyance and distress, at the sight of the more or less handsome furniture, arranged with taste, as though in readiness for a stage performance. This distress, this annoyance I feel more strongly than other people, perhaps, because in my heart of hearts there lingers inconsolable the regret for my own old-fashioned little house, where everything breathed an air of intimacy, where the old sticks of furniture, lovingly cared for, invited us to a frank, familiar confidence and seemed glad to retain the marks of the use we had made of them, because in those marks, even if the furniture was slightly damaged by them, lingered our memories of the life we had lived with it, in which it had had a share. But really I can never understand how certain pieces of furniture can fail to cause if not actually distress at least annoyance, furniture with which we dare not venture upon any confidence, because it seems to have been placed there to warn us with its rigid, elegant grace, that our anger, our grief, our joy must not break bounds, nor rage and struggle, nor exult, but must be controlled by the rules of good breeding. Houses made for the rest of the world, with a view to the part that we intend to play in society; houses of outward appearance, where even the furniture round us can make us blush if we happen for a moment to find ourselves behaving in some fashion that is not in keeping with that appearance nor consistent with the part that we have to play.

I knew that the Nestoroff lived in an expensive furnished flat in Via Mecenate. I was shewn by the maid (who had evidently been warned of my coming) into the drawing-room; but the maid was a trifle disconcerted owing to this previous warning, since she expected to see me arrive with a young lady. You, to the people who do not know you, and they are so many, have no other reality than that of your light trousers or your brown greatcoat or your “English” moustache. I to this maid was a person who was to come with a young lady. Without the young lady, I might be some one else. Which explains why, at first, I was left standing outside the door.

“Alone? And your little friend?” the Nestoroff was asking me a moment later in the drawing-room. But the question, when half uttered, between the words “your” and “little,” sank, or rather died away in a sudden change of feeling. The word “friend” was barely audible. This sudden change of feeling was caused by the pallor of my bewildered face, by the look in my eyes, opened wide in an almost savage stupefaction.

Looking at me, she at once guessed the reason of my pallor and bewilderment, and at once she too turned pale as death; her eyes became strangely clouded, her voice failed, and her whole body trembled before me as though I were a ghost.

The assumption of that body of hers into a prodigious life, in a light by which she could never, even in her dreams, have imagined herself as being bathed and warmed, in a transparent, triumphant harmony with a nature round about her, of which her eyes had certainly never beheld the jubilance of colours, was repeated six times over, by a miracle of art and love, in that drawing-room, upon six canvases by Giorgio Mirelli.

Fixed there for all time, in that divine reality which he had conferred on her, in that divine light, in that divine fusion of colours, the woman who stood before me was now what? Into what hideous bleakness, into what wretchedness of reality had she now fallen? And how could she have had the audacity to dye with that strange coppery colour the hair which there, on those six canvases, gave with its natural colour such frankness of expression to her earnest face, with its ambiguous smile, with its gaze plunged in the melancholy of a sad and distant dream!

She humbled herself, shrank back as though ashamed into herself, beneath my gaze which must certainly have expressed a pained contempt. From the way in which she looked at me, from the sorrowful contraction of her eyebrows and lips, from her whole attitude I gathered that not only did she feel that she deserved my contempt, but she accepted it and was grateful to me for it, since in that contempt, which she shared, she tasted the punishment of her crime and of her fall. She had spoiled herself, she had dyed her hair, she had brought herself to this wretched reality, she was living with a coarse and violent man, to make a sacrifice of herself: so much was evident; and she was determined that henceforward no one should approach her to deliver her from that self-contempt to which she had condemned herself, in which she reposed her pride, because only in that firm and fierce determination to despise herself did she still feel herself worthy of the luminous dream, in which for a moment she had drawn breath and to which a living and perennial testimony remained to her in the prodigy of those six canvases.

Not the rest of the world, not Nuti, but she, she alone, of her own accord, doing inhuman violence to herself, had torn herself from that dream, had dashed headlong from it. Why? Ah, the reason, perhaps, was to be sought elsewhere, far away. Who knows the secret ways of the soul? The torments, the darkenings, the sudden, fatal determinations? The reason, perhaps, must be sought in the harm that men had done to her from her childhood, in the vices by which she had been ruined in her early, vagrant life, and which in her own conception of them had so outraged her heart that she no longer felt it to deserve that a young man should with his love rescue and ennoble it.

As I stood face to face with this woman so fallen, evidently most unhappy and by her unhappiness made the enemy of all mankind and most of all of herself, what a sense of degradation, of disgust assailed me suddenly at the thought of the vulgar pettiness of the relations in which I found myself involved, of the people with whom I had undertaken to deal, of the importance which I had bestowed and was bestowing upon them, their actions, their feelings! How idiotic that fellow Nuti appeared to me, and how grotesque in his tragic fatuity as a fashionable dandy, all crumpled and soiled in his starched finery clotted with blood! Idiotic and grotesque the Cavalena couple, husband and wife! Idiotic Polacco, with his air of an invincible leader of men! And idiotic above all my own part, the part which I had allotted to myself of a comforter on the one hand, on the other of the guardian, and, in my heart of hearts, the saviour of a poor little girl, whom the sad, absurd confusion of her family life had led also to assume a part almost identical with my own; namely that of the phantom saviour of a young man who did not wish to be saved!

I felt myself, all of a sudden, alienated by this disgust from everyone and everything, including myself, liberated and so to speak emptied of all interest in anything or anyone, restored to my function as the impassive manipulator of a photographic machine, recaptured only by my original feeling, namely that all this clamorous and dizzy mechanism of life can produce nothing now but stupidities. Breathless and grotesque stupidities! What men, what intrigues, what life, at a time like this? Madness, crime or stupidity. A cinematographic life? Here, for instance: this woman who stood before me, with her coppery hair. There, on the six canvases, the art, the luminous dream of a young man who was unable to live at a time like this. And here, the woman, fallen from that dream, fallen from art to the cinematograph. Up, then, with a camera and turn the handle! Is there a drama here? Behold the principal character.

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (29)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

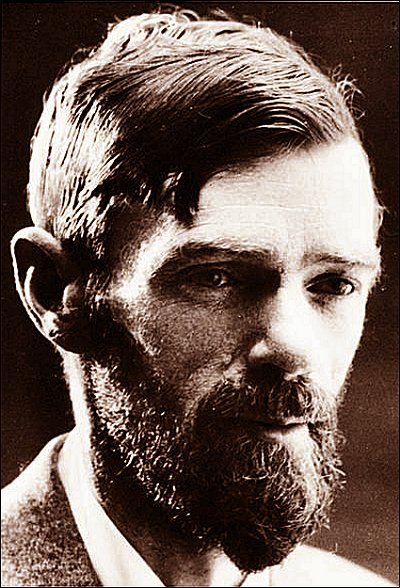

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

The Elephant is Slow to Mate

The elephant, the huge old beast,

is slow to mate;

he finds a female, they show no haste

they wait

for the sympathy in their vast shy hearts

slowly, slowly to rouse

as they loiter along the river-beds

and drink and browse

and dash in panic through the brake

of forest with the herd,

and sleep in massive silence, and wake

together, without a word.

So slowly the great hot elephant hearts

grow full of desire,

and the great beasts mate in secret at last,

hiding their fire.

Oldest they are and the wisest of beasts

so they know at last

how to wait for the loneliest of feasts

for the full repast.

They do not snatch, they do not tear;

their massive blood

moves as the moon-tides, near, more near

till they touch in flood.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD II

Daar stond Kana, op het punt klaar te komen, trillend van de pijn, die als een wortel door haar vuile lichaam liep, vanuit haar onderbuik.

Mijn ouwe bok Kaïn lachte. Hij lachte niet gemeen, zoals verwacht: hij had werkelijk pret. Hij hield zijn buik vast van het lachen.

Ik vond de toestand weer normaal, wilde verder gaan met mierrijden, maar kwam daar niet toe. Plotseling vielen er grote schaduwen over het hol, over het zand eromheen en over de hei.

Ik keek op en zag de blauwe benen van uniformzieke kerels. Hogerop: blinkende knopen en gespen. Nog hoger: kapotgeschoren kinnen boven stijve kragen. Verder niets. Niets van een hoofd of zoiets. De harde kinnen, dat was alles wat ik van de gezichten kon zien. De kerels hadden stokken waarmee ze sloegen. Daarbij bleven ze recht staan, als palen. Palen met levende takken die sloegen in het gezicht van mijn ouwe bok Kaïn.

Ik voelde me opgelucht. Ik had altijd geweten dat dit ervan moest komen. Altijd wordt alles gered door uniformen met blinkende knopen en gespen. Nu werd mijn ouwe bok Kaïn gered voor verder onheil. Ook de Gore Kana werd geslagen. De kerels hadden al veel geslagen, dat zag je aan hun routine. Ze spanden zich niet in. Toch kwamen de slagen hard aan.

Ik kwam overeind uit mijn gebukte houding en overzag in een paar tellen het slagveld. Van een van de uniformzieke kerels kon ik toen het gezicht zien. Hij had een gezicht van hout, net zo geil als dat van mijn ouwe bok Kaïn. Hij was niet geil op Kana. Dat was duidelijk. Hij toonde een intense afkeer van haar vuile, klagende lijf. Waarop de stokken neerkwamen.

Ik wist: ze mochten negenendertig slagen geven. Ik had het aantal slagen niet geteld. Ik schat dat ze achttien keer sloegen, dat Kaïn en Kana elk negen slagen kregen. Kana voelde ze het hardst. Ze was nog helemaal naakt. Daarna zag ik het gezicht boven het andere uniform. Een geteisterd gezicht. Een mislukte God die sloeg uit overtuiging.

De eerste sloeg omdat hij Kaïn en Kana lelijk vond. Een mooie vrouw zou hij beslist niet geslagen hebben. Hij zou op haar zijn gaan liggen om haar te naaien. De ander, die mislukte God, gaf een slecht voorbeeld. En bleek niet van zins vergiffenis te schenken. Ik dacht dat God alles vergaf en dat straf pas kwam na de dood! Grote mensen, zeker die met een gezicht van God, gaven altijd een slecht voorbeeld. En wat had deze man met Kaïn en Kana te maken? Waarom liet hij hen niet begaan? Ik zei er toch ook niets van? Ik wist best dat er eens een kind van zou komen. Een vuil kind met deuken in de huid van de slagen die de Gore Kana voortdurend kreeg van Kaïn. Ik zou van dat kind houden. Het zou een mongool worden, zoiets, omdat het slecht werd gevoed. Per slot van zaken werd het ook maar de wereld in geschopt.

De Gore Kana mocht zich niet aankleden. Dat was goed. Met kleren aan had ze nog minder vorm. De kerels dreven Kaïn en Kana voor zich uit. Mijn ouwe bok dacht alleen aan zijn eigen hachje. Hij vergat mij. De kerels vergaten mij ook.

Ik bleef alleen. Dit was geen toestand om te huilen. Ik moest blij zijn. Nu was ik mijn eigen baas. Nu hoefde ik me niet meer te ergeren aan het gedrag van Kaïn en zijn Gore Kana. Toch bleef ik lusteloos. Ik lette niet op de mieren die koortsachtig in treinen naar buiten bleven lopen en langs hun dode kameraden spoorden. Soms meende ik hen te horen zeggen: ‘Het zal hun straf wel zijn.’ Zoals dat ook onder mensen gaat.

Ik stond op, stak mijn handen in de broekzakken en liep in de andere richting dan de vier gegaan waren. De God en de wellusteling, Kaïn en Kana voor zich uit drijvend.

De weg was zacht. Overal bloeiden bremstruiken. Ze roken als altijd naar zweet. Ze werkten ook hard. Hun kleur was geler dan geel.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (28)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

1

Sweet and cool is the pulp of winter pears, but often, here and there, it hardens in a bitter knot. Your teeth, in the act of biting, come upon the hard piece and are set on edge. So is it with our position, which might be sweet and cool, for two of us at any rate, were we not conscious of the intrusion of something bitter and hard.

We have been going together, for the last three days, every morning, Signorina Luisetta, Aldo Nuti and I, to the Kosmograph.

Of the two of us, Signora Nene trusts me, certainly not Nuti, with her daughter. But the said daughter, of the two of us, certainly seems rather to be going with Nuti than to be coming with me.

Meanwhile: I see Signorina Luisetta, and do not see Nuti; Signorina Luisetta sees Nuti and does not see me; Nuti sees neither me nor Signorina Luisetta.

So we proceed, all three of us, side by side, but without seeing ourselves in one another’s company.

Signorina Nene’s confidence ought to irritate me, ought to… what else? Nothing. It ought to irritate me, it ought to degrade me: instead of which, it does not irritate me, it does not degrade me. It moves me, if anything. So as to make me feel more contemptuous than ever.

And so I consider the nature of this confidence, in an attempt to overcome my contemptuous emotion.

It is certainly an extraordinary tribute to my incapacity, on one hand; to my capacity, on the other. The latter–I mean the tribute to my capacity–might in one respect flatter me; but it is quite certain that this tribute has not been paid me by Signora Nene without a slight trace of derisive pity.

A man who is incapable of doing evil cannot, in her eyes, be a man at all. So that this other capacity of mine cannot be a manly quality.

It appears that we cannot help doing evil, if we are to be regarded as men. For my own part, I know quite well, perfectly well, that I am a man: evil I have done, and in abundance! But it appears that other people do not choose to notice it. And that makes me furious. It makes me furious because, obliged to assume that certificate of incapacity–which both is and is not mine–I often find my shoulders bowed, by the arrogance of other people, under a fine cloak of hypocrisy. And how often have I groaned beneath the weight of that cloak! At no time, I am certain, so often as during the last few days. I feel almost inclined to go and look Signora Nene in the face in a certain fashion, so that. … But, no, no, what an idea, poor woman! She has grown so meek, all of a sudden, so helpless rather, after that furious outbreak by her daughter and this sudden determination to become a cinematograph actress! You ought to see her when, shortly before we leave the house, every morning, she comes up to me and, behind her daughter’s back, raises her hands ever so slightly, with a furtive movement, and with a piteous look in her eyes:

“Take care of her,” she stammers.

The situation, as soon as we arrive at the Kosmograph, changes and becomes highly serious, notwithstanding the fact that at the entrance, every morning, we find–punctual to a second and trembling all over with anxiety–Cavalena. I have already told him, the day before yesterday and again yesterday, of the change in his wife; but Cavalena shews no sign as yet of becoming a Doctor again. Far from it! The day before yesterday and again yesterday, he seemed to be carried away before my eyes in a fit of distraction, as though trying not to let himself be affected by what I was saying to him:

“Oh, indeed? Good, good…” was his answer. “But I, for the present…. What is that you say? No, excuse me, I thought…. I am glad, don’t you know? But if I go back, it will all come to an end. Heaven help us! What I have to do at present is to stay here and consolidate Luisetta’s position and my own.”

Ah yes, consolidate: father and daughter might be treading on air. I reflect that their life might be easy and comfortable, their story unfold in a sweet, serene peace. There is the mother’s fortune; Cavalena, honest man, could attend quietly to his profession; there would be no need to take strangers into their home, and Signorina Luisetta, on the window sill of a peaceful little house in the sun, might gracefully cultivate, like flowers, the fairest dreams of girlhood. But no! This fiction which ought to be the reality, as everyone sees, for everyone admits that Signora Nene has absolutely no reason to torment her husband, this thing which ought to be the reality, I say, is a dream. The reality, on the other hand, must be something different, utterly remote from this dream. The reality is Signora Nene’s madness. And in the reality of this madness–which is of necessity an agonised, exasperated disorder–here they are flung out of doors, straying, helpless, this poor man and this poor girl. They wish to consolidate their position, both of them, in this reality of madness, and so they have been wandering about here for the last two days, side by side, sad and speechless, through the studios and grounds.

Cocò Polacco, to whom with Nuti they report on their arrival, tells them that there is nothing for them to do at present. But the engagement is in force; the salary is mounting up. It is unnecessary, therefore, for Signorina Luisetta to take the trouble to come; if she is not to pose, she does not lose anything.

But this morning, at last, they have made her pose. Polacco lent her to his fellow producer Bongarzoni for a small part in a coloured film, in eighteenth century costume.

I have been working for the last few days with Bongarzoni. On reaching the Kosmograph I hand over Signorina Luisetta to her father, go to the Positive Department to fetch my camera, and often it happens that for hours on end I see nothing more of Signorina Luisetta, nor of Nuti, nor of Polacco, nor of Cavalena. So that I was not aware that Polacco had given Bongarzoni Signorina Luisetta for this small part. I was thunderstruck when I saw her appear before me as if she had stepped out of a picture by Watteau.

She was with the Sgrelli, who had just completed a careful and loving supervision of her toilet in the “costume” wardrobe, and with one finger was pressing to her cheek a silken patch that refused to stick. Bongarzoni was lavish with his compliments, and the poor child made an effort to smile without moving her head, for fear of overbalancing the enormous pile of hair above it. She did not know how to move her limbs in that billowing silken skirt.

And now the little scene is arranged. An outside staircase, leading down to a stretch of park. The little lady appears from a glazed balcony; trips down a couple of steps; leans over the pillared balustrade to gaze out across the park, timid, perplexed, in a state of anxious alarm: then runs quickly down the remaining steps and hides a note, which is in her hand, under the laurel that is growing in a bowl on the pillar at the foot of the balustrade.

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

Never before have I turned the handle of my machine with such delicacy. This great black spider on its tripod has had her twice, now, for its dinner. But the first time, out in the Bosco Sacro, my hand, in turning the handle to give her to the machine to eat, did not yet ‘feel’. Whereas, on this occasion…

Ah, I am ruined, if ever my hand begins to feel! No, Signorina Luisetta, no: it is evident that you must not continue in this vile trade. Quite so, I know why you are doing it! They all tell you, Bongarzoni himself told you this morning that you have a quite exceptional natural gift for the scenic art; and I tell you so too; not because of this morning’s rehearsal, though. Oh, you went through your part as well as anyone could wish; but I know very well, I know very well how you were able to give such a marvellous rendering of anxious alarm, when, after coming down the first two steps, you leaned over the balustrade to gaze into the distance. I know so well that almost, now and then, I turned my head too to gaze where you were gazing, to see whether at that moment the Nestoroff might not have arrived.

For the last three days, here, you have been living in this state of anxiety and alarm. Not you only; although more, perhaps, than anyone else. At any moment, indeed, the Nestoroff may arrive. She has not been seen for more than a week. But she is in Rome; she has not left. Only Carlo Ferro has left, with five or six other actors and Bertini, for Tarante.

On the day of Carlo Ferro’s departure (about a fortnight ago), Polacco came to me radiant, as though a stone had been lifted from his chest.

“What did I tell you, simpleton? He would go to hell if she told him to!”

“I only hope,” I answered, “that we shan’t see him burst in here suddenly like a bomb.”

But it is already a great thing, certainly, and one that to me remains inexplicable, that he should have gone. His words still echo in my ears:

“I may be a wild beast when I’m face to face with a man, but as a man face to face with a wild beast I’m worth nothing!”

And yet, with the consciousness of being worth nothing, on a point of honour, he did not draw back, he did not refuse to face the beast; now, having a man to face, he has fled. Because it is indisputable that his departure, the day after Nuti’s arrival, has every appearance of flight.

I do not deny that the Nestoroff has such power over him that she can compel him to do what she wishes. But I have heard roaring in him, simply because of Nuti’s coming, all the fury of jealousy. His rage at Polacco’s having put him down to kill the tiger was not due only to the suspicion that Polacco was hoping in this way to get rid of him, but also and even more to the suspicion that he has made Nuti come here at the same time in order that Nuti may be free to recapture the Nestoroff. And it seems obvious to me that he is not sure of her. Why then has he gone?

No, no: there is most certainly something behind this, a secret agreement; this departure must be concealing a trap. The Nestoroff could never have induced him to go by shewing him that she was afraid of losing him, in any event, by allowing him to remain here to await the coming of a man who was certainly coming with the deliberate intention of provoking him. A fear of that sort would never have made him go. Or, at least, she would have gone with him. If she has remained here and he has gone, leaving the field clear for Nuti, it means that an agreement must have been reached between them, a net woven so strongly and securely that he himself has been able to pack tip his jealousy in it and so keep it in check. No sign of fear can she have shewn him; rather, the agreement having been reached, she must have demanded this proof of his faith in her, that he should leave her here alone to face Nuti. In fact, for several days after Carlo Ferro’s departure, she continued to come to the Kosmograph, evidently prepared for an encounter with Nuti. She cannot have come for any other reason, free as she now is from any professional engagement. She ceased to come, when she learned that Nuti was seriously ill.

But now, at any moment, she may return.

What is going to happen?

Polacco is once again on tenterhooks. He never lets Nuti out of his sight; if he is obliged to leave him for a moment, he first of all makes a covert signal to Cavalena. But Nuti, for all that, now and again, some slight obstacle makes him break out in a way that points to an exasperation forcibly held in check, is relatively calm; he seems also to have shaken off the sombre mood of the early days of his convalescence; he allows himself to be led about everywhere by Polacco and Cavalena; he shews a certain curiosity to make a closer acquaintance with this world of the cinematograph and has carefully visited, with the air of a stern inspector, both the departments.

Polacco, hoping to distract him, has twice suggested that he should try some part or other. He has declined, saying that he wishes to gain a little experience first by watching the others act.

“It is a labour,” he observed yesterday in my hearing, after he had watched the production of a scene, “and it must also be an effort that destroys, alters and exaggerates people’s expressions, this acting without words. In speaking, the action comes automatically; but without speaking….”

“You speak to yourself,” came with a marvellous seriousness from the little Sgrelli (La Sgrellina, as they all call her here). “You speak to yourself, so as not to force the action….”

“Exactly,” Nuti went on, as though she had taken the words out of his mouth.

The Sgrellina then laid her forefinger on her brow and looked all round her with an assumption of silliness which asked, with the most delicate irony:

“Who said I wasn’t intelligent?”

We all laughed, including Nuti. Polacco could hardly refrain from kissing her. Perhaps he hopes that she, Nuti having taken the place here of Gigetto Fleccia, may decide that he ought also to take Fleccia’s place in her affections, and may succeed in performing the miracle of detaching him from the Nestoroff. To enhance and give ample food to this hope, he has introduced him also to all the young actresses of the four companies; but it seems that Nuti, although exquisitely polite to all of them, does not shew the slightest sign of wishing to be detached. Besides, all the rest, even if they were not

already, more or less, bespoke, would take great care not to stand in the Sgrellina’s way. And as for the Sgrellina, I am prepared to bet that she has already observed that she would be doing an injury, herself, to a certain young lady, who has been coming for the last three days to the Kosmograph with Nuti and with ‘Shoot’.

Who has not observed it? Only Nuti himself! And yet I have a suspicion that he too has observed it. And the strange thing is this, and 1 should like to find a way of pointing it out to Signorina Luisetta: that his perception of her feeling for him creates an effect in him the opposite of that for which she longs: it turns him away from her and makes him strain all the more ardently after the Nestoroff. Because it is obvious now that Nuti remembers having identified her, in his delirium, with Duccella; and since he knows that she cannot and does not wish to love him any longer, the love that he perceives in Signorina Luisetta must of necessity appear to him a sham, no longer pitiful, now that his delirium has passed; but rather pitiless: a burning memory, which makes the old wound ache again.

It is impossible to make Signorina Luisetta understand this.

Glued by the clinging blood of a victim to his love for two different women, each of whom rejects him, Nuti can have no eyes for her; he may see in her the deception, that false Duccella, who for a moment appeared to him in his delirium; but now the delirium has passed, what was a pitiful deception has become for him a cruel memory, all the more so the more he sees the phantom of that deception persist in it.

And so, instead of retaining him, Signorina Luisetta with this phantom of Duccella drives him away, thrusts him more blindly than ever into the arms of the Nestoroff.

For her, first of all; then for him, and lastly–why not?–for myself, I see no other remedy than an extreme, almost a desperate attempt: that I should go to Sorrento, reappear after all these years in the old home of the grandparents, to revive in Duccella the earliest memory of her love and, if possible, take her away and make her come here to give substance to this phantom, ?which another girl, here, for her sake, is desperately sustaining with her pity and love.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (28)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (C)

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

C

CACHET: Toujours suivi de «tout particulier» .

CACHOT: Toujours affreux. La paille y est toujours humide. On n’en a pas encore rencontré de délicieux.

CADEAU: Ce n’est pas la valeur qui en fait le prix, ou bien ce n’est pas le prix qui en fait la valeur. Le cadeau n’est rien, c’est l’intention qui compte.

CAFÉ: Donne de l’esprit. N’est bon qu’en venant du Havre. Dans un grand dîner, doit se prendre debout. L’avaler sans sucre, très chic, donne l’air d’avoir vécu en Orient.

CALVITIE: Toujours précoce, est causée par des excès de jeunesse ou la conception de grande pensée.

CAMARILLA: S’indigner quand on prononce ce mot.

CAMPAGNE: Les gens de la campagne meilleurs que ceux des villes: envier leur sort. A la campagne tout est permis; habits bas, farces, etc.

CANARDS: Viennent tous de Rouen.

CANDEUR: Toujours adorable. On en est rempli ou on n’en a pas du tout.

CANONADE: Change le temps.

CARABINS: Dorment près des cadavres. Il y en a qui en mangent.

CARÈME: Au fond n’est qu’une mesure hygiénique.

CATAPLASME: Doit toujours être mis en attendant l’arrivée du médecin.

CATHOLICISME: A eu une influence très favorable sur les arts.

CAUCHEMAR: Vient de l’estomac.

CAVALERIE: Plus noble que l’infanterie.

CAVERNES: Habitation ordinaire des voleurs. Sont toujours remplies de serpents.

CÈDRE: Celui du Jardin des Plantes a été rapporté dans un chapeau.

CÉLÉBRITÉ: Les célébrités: s’inquiéter du moindre détail de leur vie privée, afin de pouvoir les dénigrer.

CELIBATAIRES: Tous égoïstes et débauchés. On devrait les imposer. Se préparent une triste vieillesse.

CENSURE: Utile, on a beau dire.

CERCLE: On doit toujours faire partie d’un cercle.

CERTIFICAT: Garantie pour les familles et pour les parents est toujours favorable.

CÉRUMEN: «Cire humaine» . Se garder de l’ôter parce qu’elle empêche les insectes d’enter dans les oreilles.

CHACAL: Singulier de shakos (vieux, mais fait toujours rire).

CHALEUR: Toujours insupportable. Ne pas boire quand il fait chaud.

CHAMBRE À COUCHER: Dans un vieux château: Henri IV y a toujours passé une nuit.

CHAMEAU: A deux bosses et le dromadaire une seule. Ou bien le chameau a une bosse et le dromadaire deux (on s’y embrouille).

CHAMPAGNE: Caractérise le dîner de cérémonie. Faire semblant de le détester, en disant que «ce n’est pas du vin« . Provoque l’enthousiasme chez les petites gens. La Russie en consomme plus que la France. C’est par lui que les idées françaises se sont répandues en Europe. Sous la Régence, on ne faisait pas autre chose que d’en boire. Mais on ne le boit pas, on le «sable» .

CHAMPIGNONS: Ne doivent être achetés qu’au marché.

CHANTEUR: Avalent tous les matins un oeuf frais pour s’éclaircir la voix. Le ténor a toujours une voix charmante et tendre, le baryton un organe sympathique et bien timbré, et la basse une émission puissante.

CHAPEAU: Protester contre la forme des chapeaux.

CHARCUTIER: Anecdote des pâtés faits avec de la chair humaine. Toutes les charcutières sont jolies.

CHARTREUX: Passent leur temps à faire de la chartreuse, à creuser leur tombe et à dire: «Frère, il faut mourir.»

CHASSE: Excellent exercice que l’on doit feindre d’adorer. Fait partie de la pompe des souverains. Sujet de délire pour la magistrature.

CHAT: Les chats sont traîtres. Les appeler tigres de salon. Leur couper la queue pour empêcher le vertigo.

CHÂTAIGNE: Femelle du marron.

CHATEAUBRIAND: Connu surtout par le beefsteak qui porte son nom.

CHÂTEAU FORT: A toujours subi un siège sous Philippe Auguste.

CHEMINÉE: Fume toujours. Sujet de discussion à propos du chauffage.

CHEMINS DE FER: Si Napoléon les avait eus à sa disposition, il aurait été invincible. S’extasier sur leur invention et dire: «Moi, monsieur, qui vous parle, j’étais ce matin à X…; je suis parti par le train de X…; là-bas, j’ai fait mes affaires, etc. , et à x heures, j’étais revenu!»

CHEVAL: S’il connaissait sa force, ne se laisserait pas conduire. Viande de cheval: beau sujet de brochure pour un homme qui désire se poser en personnage sérieux. Cheval de course: le mépriser. A quoi sert-il?

CHIEN: Spécialement créé pour sauver la vie à son maître. Le chien est l’ami de l’homme.

CHIRURGIENS: Ont le coeur dur: les appeler bouchers.

CHOLÉRA: Le melon donne le choléra. On s’en guérit en prenant beaucoup de thé avec du rhum.

CHRISTIANISME: A affranchi les esclaves.

CIDRE: Gâte les dents.

CIGARES: Ceux de la Régie, «tous infects» . Les seuls bons viennent par contrebande.

CIRAGE: N’est bon que si on le fait soi-même.

CLAIR-OBSCUR: On ne sait pas ce que c’est.

CLARINETTE: En jouer rend aveugle. Ex.: Tous les aveugles jouent de la clarinette.

CLASSIQUES (les): On est censé les connaître.

CLOCHER de village: Fait battre le coeur.

CLOU: V. boutons.

CLOWN: A été disloqué dès l’enfance.

CLUB: Sujet d’exaspération pour les conservateurs. Embarras et discussion sur la prononciation de ce mot.

COCHON: L’intérieur de son corps étant «tout pareil à celui d’un homme» , on devrait s’en servir dans les hôpitaux pour apprendre l’anatomie.

COCU: Toute femme doit faire son mari cocu.

COFFRES-FORTS: Leurs complications sont très faciles à déjouer.

COGNAC: Très funeste. Excellent dans plusieurs maladies. Un bon verre de cognac ne fait jamais de mal. Pris à jeun tue le ver de l’estomac.

COIT, COPULATION: Mots à éviter. Dire: «Ils avaient des rapports…»

COLÈRE: Fouette le sang; hygiénique de s’y mettre de temps en temps.

COLLEGE, lycée: Plus noble qu’une pension.

COLONIES (nos): S’attrister quand on en parle.

COMÉDIE: En vers, ne convient plus à notre époque. On doit cependant respecter la haute comédie. Castigat ridendo mores.

COMÈTES: Rire des gens qui en avaient peur.

COMMERCE: Discuter pour savoir lequel est le plus noble, du commerce ou de l’industrie.

COMMUNION: La première communion: le plus beau jour de la vie.

COMPAS: On voit juste quand on l’a dans l’oeil.

CONCERT: Passe-temps comme il faut.

CONCESSIONS: N’en faire jamais. Elles ont perdu Louis XVI.

CONCILIATION: Les prêcher toujours, même quand les contraires sont absolus.

CONCUPISCENCE: Mot de curé pour exprimer les désirs charnels.

CONCURRENCE: L’âme du commerce.

CONFISEURS: Tous les Rouennais sont confiseurs.

CONFORTABLE: Précieuse découverte moderne.

CONGRÉGANISTE: Chevalier d’Onan.

CONJURÉ: Les conjurés ont toujours la manie de s’inscrire sur une liste.

CONSERVATEUR: Homme politique à gros ventre. «Conservateur borné! – Oui, monsieur, les bornes servent de garde-fou. «

CONSERVATOIRE: Il est indispensable d’être abonné au Conservatoire.

CONSTIPATION: Tous les gens de lettres sont constipés. Influe sur les convictions politiques.

CONTRALTO: On ne sait pas ce que c’est.

CONVERSATION: La politique et la religion doivent en être exclues.

COPAHU: Feindre d’en ignorer l’usage.

COQ: Un homme maigre doit toujours dire qu’un bon coq n’est jamais gras.

COR aux pieds: Indique le changement de temps mieux qu’un baromètre. Très dangereux quand il est mal coupé: citer des exemples d’accidents terribles.

COR de chasse: Dans les bois fait bon effet, et le soir sur l’eau.

CORDE: On ne connaît pas la force d’une corde. Est plus solide que le fer.

CORDONNIER: Ne sutor ultra crepidam.

CORPS: Si nous savions comment notre corps est fait, nous n’oserions pas faire un mouvement.

CORSET: Empêche d’avoir des enfants.

COSAQUES: Mangent de la chandelle.

COTON: Est surtout utile pour les oreilles.

COURTISANE: Est un mal nécessaire. Sauvegarde de nos filles et de nos soeurs tant qu’il y aura des célibataires. Devraient être chassées impitoyablement. On ne peut plus sortir avec sa femme à cause de leur présence sur le boulevard. Sont toujours des filles du peuple débauchées par des bourgeois riches.

COUSIN: Conseiller aux maris de se méfier du petit cousin.

COUTEAU: Est catalan quand la lame est longue. S’appelle poignard quand il a servi à commettre un crime.

CRAPAUD: Mâle de la grenouille. Possède un venin fort dangereux. Habite l’intérieur des pierres.

CRÉOLE: Vit dans un hamac.

CRIMINEL: Toujours odieux.

CRITIQUE: Toujours éminent. Est censé tout connaître, tout savoir, avoir tout lu, tout vu. Quand il vous déplaît, l’appeler Aristarque, ou eunuque.

CROCODILE: Imite le cri des enfants pour attirer l’homme.

CROISADES: Ont été bienfaisantes pour le commerce de Venise.

CRUCIFIX: Fait bien dans une alcôve et à la guillotine.

CUIR: Tous les cuirs viennent de Russie.

CUISINE: De restaurant: toujours échauffante. Bourgeoise: toujours saine. Du Midi: trop épicée ou toute à l’huile.

CUJAS: Inséparable de Bartole; on ne sait pas ce qu’ils ont écrit, n’importe. Dire à tout homme étudiant le droit: «Vous êtes enfermé dans Cujas et Bartole»

CURACAO: Le meilleur est de Hollande parce qu’il se fabrique à Curaçao, une des Antilles.

CYGNE: Chante avant de mourir. Avec son aile peut casser la cuisse d’un homme. Le cygne de Cambrai n’était pas un oiseau, mais un homme nommé Fénélon. Le cygne de Mantoue, c’est Virgile. Le cygne de Pesaro, c’est Rossini.

CYPRÈS: Ne pousse que dans les cimetières.

CZAR: Prononcer tzar et de temps en temps autocrate.

Gustave Flaubert:

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (C)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

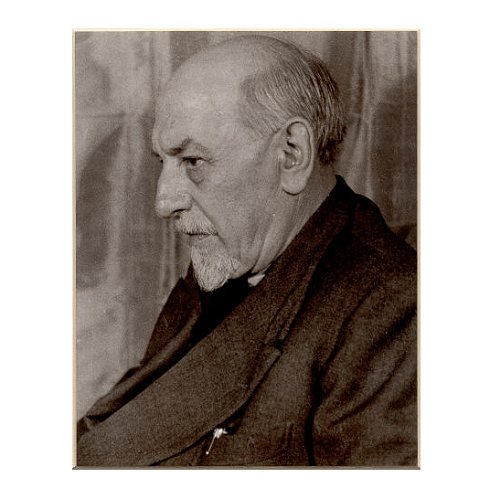

Ton van Reen schreef de novelle DE GEVANGENE DIE VERMOORD WERD AANGETROFFEN IN DE LIBERTYSTRAAT in 1962. Dat is vijftig jaar geleden. Hij was toen 20 jaar oud. Het manuscript lag 3 jaar bij Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers. Directeur Johan Veninga en redacteur Martin Ros waren er enthousiast over en verzekerden hem dat het boek bij deze uitgeverij zou verschijnen. Na (te) lang wachten bood Van Reen het boek aan bij Uitgeverij Meulenhoff die het in 1967 publiceerde, samen met de novelle DE MOORD DOOR GEALLIEERDE MILITAIREN EN BURGERS UIT DE LICHTSTAD KORK OP LEDEN VAN HET DOOR DE MIERRIJDER GESTICHTE GEZIN VAN CHERUBIJN, een novelle die hij in 1963 had geschreven.

Beiden novellen zijn, in 6e druk, opgenomen in de uitgave VERZAMELD WERK, DEEL 1, uitgeverij De Geus, isbn 978-90-445-1351-6.

Na verschijning schreef Gerrit Krol in het toenmalige Het Handelsblad: Ik heb lang uitgezien naar een verhaal waarin de hoererij op zo onschuldige wijze wordt behandeld. De Gevangene en De Moord zijn heel gekke, ontroerende idylles, zoals je zelden leest en waarin je, dwars door de onmogelijkheden heen, volledig gelooft. Dat bewijst meteen de kracht van Van Reens schrijverschap dat, behalve kracht, ook zoveel naiefs heeft dat ik me van tijd tot tijd afvroeg hoe het mogelijk is dat iemand zo kan schrijven. Een onvergetelijk boek. Ton van Reen schrijft leerboeken voor schrijvers.

Aad Nuis schreef in de Haagse Post: Van Reen schrijft eigenlijk steeds sprookjes, waarbij de toon onverhoeds kan omslaan van Andersen op zijn charmants in Grimm op zijn gruwelijkst.

Kempis.nl zal beide novellen publiceren.

DE MOORD DOOR GEALLIEERDE MILITAIREN EN BURGERS UIT DE LICHTSTAD KORK OP LEDEN VAN HET DOOR DE MIERRIJDER GESTICHTE GEZIN VAN CHERUBIJN

kleine roman, Ton van Reen

De moord door geallieerde militairen en burgers uit de Lichtstad Kork op leden van het door de mierrijder gestichte gezin van Cherubijn

Voor Alice, het meisje dat ik trof in de zweef tijdens de eerste naoorlogse kermis te Oeroe

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD I

KAïN EN DE GORE KANA

Ik mocht alleen mieren berijden. Andere soorten paarden waren te edel. Te groot. En wat de doorslag gaf: te duur.

In die tijd kostte een goed paard al zeker rond de negenhonderd gulden. Hoewel een goed paard van toen beter was dan een goed paard van nu. Dat lag aan de natuur van de paarden die in die tijd niet zo uitgekruist was. Zoals dat met de hedendaagse paarden het geval is. Een Holsteiner bijvoorbeeld, zeker een goed paard, is eigenlijk een kruising. De ene tak komt voort enerzijds uit een aangespoelde fjordenhengst die in de zee lag om wind in de zeilen te blazen van Noorse boten die door de Sont voeren en anderzijds uit een afgedankt werkpaard van een boer uit Lüne of daaromtrent. De andere tak toont verwantschap met de dochter van de laatste graaf van Holstein en het spook van de Lüne-heide.

Ik reed mier en deed dat voortreffelijk. Ik oefende veel. Mierrijden is een van de moeilijkste sporten die men zich denken kan.

Al spelend en trainend zag ik niet veel meer dan de korrels zand die door nog niet ingereden mieren treinsgewijs, via een uiterst vernuftig gangenstelsel, naar de oppervlakte werden gedragen. Daar neergelegd en gesorteerd op dikte en kleur gaven ze het mierenhol een aantrekkelijk uiterlijk. Zo netjes als een voor de zondag geharkt tuintje voor een burgermanshuis.

Mijn ouwe bok Kaïn lag klaar te komen. Paarsgewijs aan de Gore Kana. Ik mocht haar niet. Ze was erg vies en vlezig, plaatselijk spierwit, met rode striemen van de elastieken in haar kleren. Alsof een rood touw om haar naakte en witte lijf was gedraaid.

Niemand die zich over mij ontfermde.

Na iedere rit doodde ik mijn rijdier. Met een takje drukte ik de smalle verbinding tussen de twee korrels die zijn lichaam vormden door.

Meestal lag het slachtoffer dan te zieltogen. Het was moeilijk te zien of het kramp was of iets anders. De bewegingen waren miniem. En kleur in de ogen heeft een mier niet. Heeft een mier wel ogen?

Dan nam ik een nieuw rijdier uit de trein die uit het mierenhol naar buiten liep, bereed het en doodde ook dat. Zo kon ik, in ongeveer tien minuten, twintig dieren berijden over een afstand van dertig centimeter elk. Mierrijden vereist de nodige routine. Ik wist dat, als er ooit wedstrijden mierrijden gehouden zouden worden, ik zeker kampioen werd. De tact die ik van nature had, en de oefening, waren de beginselen van het mierrijden.

Ik oefende iedere dag, tenminste als ik de kans kreeg. De mieren waren niet altijd even snel. Er waren trage soorten. Dan kwam je in tien minuten met elke mier dertig centimeter te laten lopen hooguit aan vijftien stuks. Dan ging de lol eraf. Mijn ouwe bok Kaïn trok zijn broek over zijn harde billen. Met de vlakke hand sloeg hij Gore Kana op de vuilwitte buik, zodat ze met een gil opsprong en als een afzichtelijk gedrocht afstak tegen de van hitte trillende lucht.

Nooit heb ik een afzichtelijker beeld gezien dan deze Gore Kana. De vuile baard van vuilnat schaamhaar, haar dat vuil en zwart afstak tegen een vaal witte buik.

Uit afschuw staakte ik het mierrijden, gaf een gil en kreeg van Kaïn een klap in mijn gezicht. Mijn geile bok Kaïn met de harde billen die mijn grootvader was.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (27)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

5

I have landed in a regular volcanic region. Eruptions and earthquakes without end. A big volcano, apparently snow-clad but inwardly in perpetual ebullition, Signora Nene. That one knew. But now there has come to light, unexpectedly, and has given its first eruption a little volcano, in whose bowels the fire has been lurking, hidden and threatening, albeit kindled but a few days ago.

The cataclysm was brought about by a visit from Polacco, this morning. Having come to persist in his task of persuading Nuti that he ought to leave Rome and return to Naples, to complete his convalescence, and after that should resume his travels, to distract his mind and be cured altogether, he had the painful surprise of finding Nuti up, as pale as death, with his moustache shaved clean to shew his firm intention of beginning at once, this very day, his career as an actor with the Kosmograph.

He shaved his moustache himself, as soon as he left his bed. It came as a surprise to all of us as well, because only last night the Doctor ordered him to keep absolutely quiet, to rest and not to leave his bed, except for an hour or so before noon; and last night he promised to obey these instructions.

We stood open-mouthed when we saw him appear shaved like that, completely altered, with that face of death, still not very steady on his legs, exquisitely attired.

He had cut himself slightly in shaving, at the left corner of his mouth; and the dried blood, blackening the cut, stood out against the chalky pallor of his face. His eyes, which now seemed enormous, with their lower lids stretched, as it were, by his loss of flesh, so as to shew the white of the eyeball beneath the line of the cornea, wore in confronting our pained stupefaction a terrible, almost a wicked expression of dark contempt and hatred.

“What in the world…” exclaimed Polacco.

He screwed up his face, almost baring his teeth, and raised his hands, with a nervous tremor in all his fingers; then, in the lowest of tones, indeed almost without speaking, he said:

“Leave me, leave me alone!”

“But you aren’t fit to stand!” Polacco shouted at him.

He turned and looked at him suspiciously:

“I can stand. Don’t worry me. I have… I have to go out… for a breath of air.”

“Perhaps it is a little soon, you know,” Cavalena tried to intervene, “if you will allow me….”

“But I tell you, I want to go out!” Nuti cut him short, barely tempering with a wry smile the irritation that was apparent in his voice.

This irritation springs from his desire to tear himself away from the attentions which we have been paying him recently, and which may have given us (though not me, I assure you) the illusion that he in a sense belongs to us from now onwards, is one of ourselves. He feels that this desire is held in check by his respect for the debt of gratitude which he owes to us, and sees no other way of breaking that bond of respect than by shewing indifference and contempt for his own health and welfare, so that we may begin to feel a resentment for the attentions we have paid him, and this resentment, at once creating a breach between him and ourselves, may absolve him from that debt of gratitude. A man in that state of mind dares not look people in the face And for that matter he, this morning, was not able to look any of us straight in the face.

Polacco, confronted by so definite a resolution, could see no other way out of the difficulty than to post round about him to watch, and, if need be, to defend him, as many of us as possible, and principally one who more than any of us has shewn pity for him and to whom he therefore owes a greater consideration; and, before going off with him, begged Cavalena emphatically to follow them at once to the Kosmograph, with Signorina Luisetta and myself. He said that Signorina Luisetta could not leave the film half-finished in which by accident she had been called upon to play a part, and that such a desertion would moreover be a real pity, because everyone was agreed that, in that short but by no means easy part, she had shewn a marvellous aptitude, which might lead, by his intervention, to a contract with the Kosmograph, an easy, safe and thoroughly respectable source of income, under her father’s protection.

Seeing Cavalena agree enthusiastically to this proposal, I was more than once on the point of going up to him to pluck him gently by the sleeve.

What I feared did, as a matter of fact, occur.

Signora Nene assumed that it was all a plot j engineered by her husband–Polacco’s morning call, Nuti’s sudden decision, the offer of a contract to her daughter–to enable him to go and flirt with the young actresses at the Kosmograph. And no sooner had Polacco left the house with Nuti than the volcano broke out in a tremendous eruption.

Cavalena at first tried to stand up to her, putting forward the anxiety for Nuti which obviously–as how in the world could anyone fail to see–had suggested this idea of a contract to Polacco. What? She didn’t care two pins about Nuti? Well, neither did he! Let Nuti go and hang himself a hundred times over, if once wasn’t enough! It was a question of seizing this golden opportunity of a contract for Luisetta! It would compromise her? How in the world could she be compromised, under the eyes of her father?

But presently, on Signora Nene’s part, argument ended, giving way to insults, vituperation, with such violence that finally Cavalena, indignant, exasperated, furious, rushed out of the house.

I ran after him down the stairs, along the street, doing everything in my power to stop him, repeating I don’t know how many times:

“But you are a Doctor! You are a Doctor!”

A Doctor, indeed! For the moment he was a wild beast in furious flight. And I had to let him escape, so that he should not go on shouting in the street.

He will come back when he is tired of running about, when once again the phantom of his tragicomic destiny, or rather of his conscience, appears before him, unrolling the dusty parchment certificate of his medical degree.

In the meantime, he will find a little breathing-space outside.

Returning to the house, I found, to my great and painful surprise, an eruption of the little volcano; an eruption so violent that the big volcano was almost overwhelmed by it.

She no longer seemed herself, Signorina Luisetta! All the disgust accumulated in all these years, from a childhood that had passed without ever a smile amid quarrels and scandal; all the disgraceful scenes which they had made her witness, she hurled in her mother’s face and at the back of her retreating father. Ah, so her mother was thinking now of her being compromised? When for all these years, with her idiotic, shameful insanity, she had destroyed her daughter’s existence, irreparably! Submerged in the sickening shame of a family which no one could approach without a feeling of revulsion! It was not compromising her, then, to keep her tied to that shame? Did her mother not hear how everyone laughed at her and at such a father? She had had enough, enough, enough! She had no wish to be tormented any longer by that laughter; she wished to free herself from the disgrace, and to make her escape by the way that was opening now before her, unsought, along which nothing worse could conceivably befall her! Away! Away! Away!

She turned to me, heated and trembling.

“You come with me, Signor Gubbio! I am going to my room to put on my hat, and then let us start at once!”

She ran off to her room. I turned to look at her mother.

Left speechless before her daughter who had at last risen to crush her with a condemnation which she at once felt to be all the more deserved inasmuch as she knew that the thought of her daughter’s being compromised was nothing more, really, than an excuse brought forward to prevent her husband from accompanying the girl to the Kosmograph; now, left face to face with me, with drooping head, her hands pressed to her bosom, she was endeavouring in a hoarse groan to liberate the cry of grief from her wrung, contracted bowels.

It pained me to see her.

All of a sudden, before her daughter returned, she raised her hands from her bosom and joined them in supplication, still powerless to speak, her whole face contracted in expectation of the tears which she had not yet succeeded in drawing up from their fount. In this attitude, she said to me with her hands what certainly she would never have said to me with her lips. Then she buried her face in them and turned away, as her daughter entered the room.

I drew the latter’s attention, pityingly, to her mother as she went off sobbing to her own room.

“Would you like me to go by myself?” Signorina Luisetta said menacingly.

“I should like you,” I answered sadly, “at least to calm yourself a little first.”

“I shall calm myself on the way,” she said, “Come along, let us be off.”

And a little later, when we had got into a carriage at the end of Via Veneto, she added:

“Anyhow, you’ll see, we are certain to find Papa at the Kosmograph.”

What made her add this reflexion? Was it to free me from the thought of the responsibility she was making me assume, in obliging me to accompany her? Then she is not really sure of her freedom to act as she chooses. In fact, she at once went on:

“Does it seem to you a possible life?”

“But if it is madness!” I reminded her. “If, as your father says, it is a typical form of paranoia?”

“Quite so, but for that very reason! Is it possible to go on living like that? When people have trouble of that sort, they can’t have a home any more; nor a family; nor anything. It is an endless struggle, and a desperate one, believe me! It can’t go on! What is to be done? What is to stop it? One flies off one way, another another. Everyone sees us, everyone knows. Our house stands open to the world. There is nothing left to keep secret! We might be living in the street. It is a disgrace! A disgrace!! Besides, you never know, perhaps this meeting violence with violence will make her shake off this madness which is driving us all mad! At least, I shall be doing something… I shall see things, I shall move about… I shall shake off this degradation, this desperation!”

“But if for all these years you have put up with this desperation, how in the world can you now, all of a sudden,” I found myself asking her, “rebel so fiercely?”

If, immediately after that little part which she had played in the Bosco Sacro, Polacco had suggested engaging her at the Kosmograph, would she not have recoiled from the suggestion, almost with horror? Why, of course! And yet the conditions at home were just the same then.

Whereas now here she is racing off with me to the Kosmograph! In desperation? Yes, but not on account of that mother of hers who gives her no peace.

How pale she turned, how ready she seemed to faint, as soon as her father, poor Cavalena, appeared with a face of terror in the doorway of the Kosmograph to inform us that “he,” Aldo Nuti, was not there, and that Polacco had telephoned to the management to say that he would not be coming there that day, so that there was nothing for it but to turn back.

“I can’t myself,” I said to Cavalena. “I have to remain here. I am very late as it is. You must take the Signorina home.”

“No, no, no, no!” shouted Cavalena. “I shall keep her with me all day; but afterwards I shall bring her back here, and you will oblige me, Signor Gubbio, by seeing her home, or she shall go alone. I, no; I decline to set foot in the house again! That will do, now! That will do!”

And off he went, accompanying his protests with an expressive gesture of his head and hands. Signorina Luisetta followed her father, shewing clearly in her eyes that she no longer saw any reason for what she had done. How cold the little hand was that she held out to me, and how absent her glance and hollow her voice, when she turned to take leave of me and to say to me:

“Till this evening.”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (27)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (B)

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

B

BACCALAURÉAT: Tonner contre.

BADAUD: Tous les Parisiens sont des badauds quoique sur dix habitants de Paris il y ait neuf provinciaux. A Paris on ne travaille pas.

BADIGEON dans les églises: Tonner contre. Cette colère artistique est extrêmement bien portée.

BAGNOLET: Pays célèbre par ses aveugles.

BAGUE: Il est très distingué de la porter au doigt indicateur. La mettre au pouce est trop oriental. Porter des bagues déforme les doigts.

BÂILLEMENT: Il faut dire: «Excusez-moi, ça ne vient pas de l’ennui, mais de l’estomac.»

BAISER: Dire embrasser, plus décent. Doux larcin. Le baiser se dépose sur le front d’une jeune fille, la joue d’une maman, la main d’une jolie femme, le cou d’un enfant, les lèvres d’une maîtresse.

BALLONS: Avec les ballons, on finira par aller dans la lune. On n’est pas près de les diriger.

BANDITS: Toujours féroces.

BANQUET: La plus franche des cordialité ne cesse d’y régner. On en emporte le meilleur souvenir et on ne se sépare jamais sans s’être donné rendez-vous pour l’année prochaine. Un farceur doit dire: «Au banquet de la vie, infortuné convive…» , etc.

BANQUIERS: Tous riches. Arabes, loups, cerviers.

BARAGOUIN: Manière de parler des étrangers. Toujours rire de l’étranger qui parle mal français.

BARBE: Signe de force. Trop de barbe fait tomber les cheveux. Utile pour protéger les cravates.

BARBIER: Aller chez le frater, chez Figaro. Le barbier de Louis XI. Autrefois saignait.

BAS-BLEU: Terme de mépris pour désigner toute femme qui s’intéresse aux choses intellectuelles. Citer Molière à l’appui: «Quand la capacité de son esprit se hausse…» , etc.

BASES de la société: Id est, la propriété, la famille, la religion, le respect des autorités. En parler avec colère si on les attaque.

BASILIQUE: Synonyme pompeux d’église. Est toujours imposante.

BASQUES: Le peuple qui court le mieux.

BATAILLE: Toujours sanglante. Il y a toujours deux vainqueurs, le battant et le battu.

BÂTON: Plus redoutable que l’épée.

BAUDRUCHE: Ne sert qu’à faire des ballons.

BAYADÈRE: Mot qui entraîne l’imagination. Toutes les femmes de l’Orient sont des bayadères (v. odalisques).

BEETHOVEN: Ne prononcez pas Bitovan. Se pâmer quand même lorsqu’on exécute une de se oeuvres.

BERGERS: Tous sorciers. Ont la spécialité de causer avec la Sainte Vierge.

BÊTES: Ah! si les bêtes pouvaient parler! Il y en a qui sont plus intelligentes que des hommes.

BIBLE: Le plus ancien livre du monde.

BIBLIOTHÈQUE: Toujours en avoir une chez soi, principalement quand on habite la campagne.

BIÈRE: Il ne faut pas en boire, ça enrhume.

BILLARD: Noble jeu. Indispensable à la campagne.

BLONDES: Plus chaudes que les brunes (v. brunes).

BOIS: Les bois font rêver. Sont propres à composer des vers. A l’automne, quand on se promène, on doit dire: «De la dépouille de nos bois…» , etc.

BONNES: Toutes mauvaises. Il n’y a plus de domestiques!

BONNET GREC: Indispensable à l’homme de cabinet. Donne de la majesté au visage.

BOSSUS: Ont beaucoup d’esprit. Sont très recherchés par des femmes lascives.

BOTTE: Par les grandes chaleurs, ne jamais oublier les allusions sur les bottes de gendarmes ou les souliers des facteurs (n’est permis qu’à la campagne, au grand air). On n’est bien chaussé qu’avec des bottes.

BOUCHERS: Sont terribles en temps de révolution.

BOUDIN: Signe de gaieté dans les maisons. Indispensable la nuit de Noël.

BOUDDHISME: «Fausse religion de l’Inde» (Définition du Dictionnaire Bouillet, 1re édition).

BOUILLI (le): C’est sain. Inséparable du mot soupe: la soupe et le bouilli.

BOULET: Le vent du boulet rend aveugle.

BOURREAU: Toujours de père en fils.

BOURSE (la): Thermomètre de l’opinion publique.

BOURSIERS: Tous voleurs.

BOUTONS: Au visage ou ailleurs, signe de santé et de force du sang. Ne point les faire passer.

BRACONNIERS: Tous forçats libérés. Auteurs de tous les crimes commis dans les campagnes. Doivent exciter une colère frénétique: «Pas de pitié, monsieur, pas de pitié!»

BRAS: Pour gouverner la France, il faut un bras de fer.

BRETONS: Tous braves gens, mais entêtés.

BROCHE: Doit toujours encadrer une mèche de cheveux ou une photographie.

BRUNES: Plus chaudes que les blondes (v. blondes).

BUDGET: Jamais en équilibre.

BUFFON: Mettait des manchettes pour écrire.

Gustave Flaubert:

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (B)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, Archive E-F, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature