Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

David van Reen

David van Reen

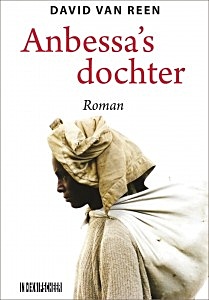

Anbessa’s dochter

Roman

Ethiopië 1991. Lasta, een meisje van veertien, woont in Lalibela, het beroemde stadje met de uit de rotsen gehakte kerken. Soldaten van het moorddadige communistische regime zoeken haar vader Anbessa, een onderwijzer, die ze aanzien voor een opstandeling. Hij vlucht. Uit wraak wordt Lasta’s moeder door de soldaten verkracht en vermoord. Een hoge officier biedt Lasta een baantje aan als huismeid in Addis Abeba. Ze wordt uitgebuit. Ze vlucht en komt terecht tussen de duizenden mensen die op straat leven. Soms heeft ze een baantje. Meestal gaat het niet goed met haar, vooral niet als ze in verwachting raakt en de vader van het kind haar in de steek laat. Na jaren besluit ze terug te keren naar Lalibela.

Anbessa’s dochter is een kleurrijke roman over mensen aan de onderkant van de samenleving. Hoewel het een schokkend verhaal is, gebaseerd op de waarheid van de hoofdpersonen, is het ook een verhaal over mensen die proberen iets moois van hun leven te maken.

Van David van Reen (1969-2015) verschenen eerder de roman Engelen der wrake, die zich afspeelt in Nairobi, en het fotoboek Het land van de verbrande gezichten over het leven in Ethiopië. Hij woonde lange tijd in Kenia en Ethiopië. Hij was schrijver, schilder en fotograaf. David van Reen was in 1999 ook mede-oprichter van Stichting Lalibela (Ethiopië). Over zijn werk in Ethiopië maakte Marijn Poels voor L1 in 2012 de film ‘David in Ethiopië’.

David van Reen

Anbessa’s dochter

Roman

Nederland – Ethiopië

Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer

Paperback met flappen,

212 blz., € 16,50

ISBN 978-90-6265-930-2

september 2016

# Meer info website Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer

# Meer info website Stiichting Lalibela

magazine fleursdumal.nl

More in: African Art, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, David van Reen, David van Reen Photos

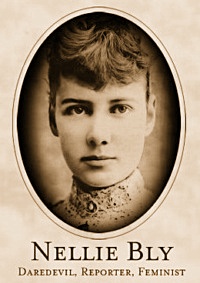

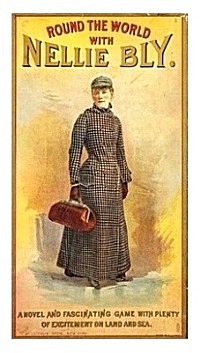

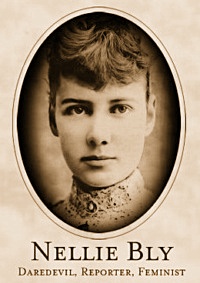

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter II: Preparing for the ordeal)

by Nellie Bly

BUT to return to my work and my mission. After receiving my instructions I returned to my boarding-house, and when evening came I began to practice the role in which I was to make my debut on the morrow. What a difficult task, I thought, to appear before a crowd of people and convince them that I was insane. I had never been near insane persons before in my life, and had not the faintest idea of what their actions were like. And then to be examined by a number of learned physicians who make insanity a specialty, and who daily come in contact with insane people! How could I hope to pass these doctors and convince them that I was crazy? I feared that they could not be deceived. I began to think my task a hopeless one; but it had to be done. So I flew to the mirror and examined my face. I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection. I assure you the sight was not reassuring, even to myself, especially in the dead of night. I tried to turn the gas up higher in hopes that it would raise my courage. I succeeded only partially, but I consoled myself with the thought that in a few nights more I would not be there, but locked up in a cell with a lot of lunatics.

The weather was not cold; but, nevertheless, when I thought of what was to come, wintery chills ran races up and down my back in very mockery of the perspiration which was slowly but surely taking the curl out of my bangs. Between times, practicing before the mirror and picturing my future as a lunatic, I read snatches of improbable and impossible ghost stories, so that when the dawn came to chase away the night, I felt that I was in a fit mood for my mission, yet hungry enough to feel keenly that I wanted my breakfast. Slowly and sadly I took my morning bath and quietly bade farewell to a few of the most precious articles known to modern civilization. Tenderly I put my tooth-brush aside, and, when taking a final rub of the soap, I murmured, “It may be for days, and it may be–for longer.” Then I donned the old clothing I had selected for the occasion.

I was in the mood to look at everything through very serious glasses. It’s just as well to take a last “fond look,” I mused, for who could tell but that the strain of playing crazy, and being shut up with a crowd of mad people, might turn my own brain, and I would never get back. But not once did I think of shirking my mission. Calmly, outwardly at least, I went out to my crazy business.

I first thought it best to go to a boarding-house, and, after securing lodging, confidentially tell the landlady, or lord, whichever it might chance to be, that I was seeking work, and, in a few days after, apparently go insane. When I reconsidered the idea, I feared it would take too long to mature. Suddenly I thought how much easier it would be to go to a boarding-home for working women. I knew, if once I made a houseful of women believe me crazy, that they would never rest until I was out of their reach and in secure quarters.

From a directory I selected the Temporary Home for Females, No. 84 Second Avenue. As I walked down the avenue, I determined that, once inside the Home, I should do the best I could to get started on my journey to Blackwell’s Island and the Insane Asylum.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter II: Preparing for the ordeal)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

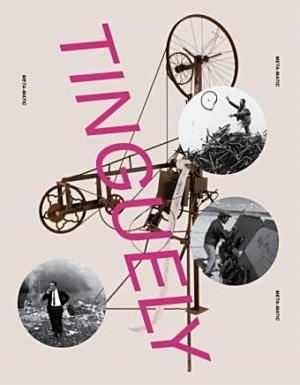

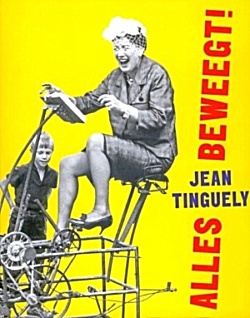

Jean Tinguely – Machinespektakel

Grootste overzicht ooit in Nederland van veelzijdige avant-gardekunstenaar

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

1 oktober 2016 – 5 maart 2017

De Zwitserse kunstenaar Jean Tinguely (1925 – 1991) staat bekend om zijn speelse, stoere machinekunst en explosieve performances. Alles moest anders, alles moest in beweging. Precies 25 jaar na zijn dood presenteert het Stedelijk vanaf 1 oktober een retrospectief van Tinguely: de grootste tentoonstelling van deze kunstenaar ooit in Nederland. Door middel van meer dan honderd, merendeels werkende machinesculpturen, films, foto’s, tekeningen en archiefmateriaal, maakt de bezoeker op chronologische en thematische wijze kennis met Tinguely’s artistieke ontwikkeling en motieven; zoals zijn voorliefde voor absurd spel en zijn fascinatie voor destructie en vergankelijkheid

De Zwitserse kunstenaar Jean Tinguely (1925 – 1991) staat bekend om zijn speelse, stoere machinekunst en explosieve performances. Alles moest anders, alles moest in beweging. Precies 25 jaar na zijn dood presenteert het Stedelijk vanaf 1 oktober een retrospectief van Tinguely: de grootste tentoonstelling van deze kunstenaar ooit in Nederland. Door middel van meer dan honderd, merendeels werkende machinesculpturen, films, foto’s, tekeningen en archiefmateriaal, maakt de bezoeker op chronologische en thematische wijze kennis met Tinguely’s artistieke ontwikkeling en motieven; zoals zijn voorliefde voor absurd spel en zijn fascinatie voor destructie en vergankelijkheid

Te zien zijn de vroege draadsculpturen en reliëfs waarmee hij de abstracte schilderijen van kunstenaars als Malevich, Miró en Klee nabootst en verandert door ze in beweging te zetten; de interactieve tekenmachines en wild dansende installaties van schroot, afval en gebruikte kledingstukken; en zijn strakke, militaristisch aandoende zwarte sculpturen.

-Primeur: monumentale Mengele-Totentanz voor het eerst te zien in Nederland

De tentoonstelling besteedt veel aandacht aan Tinguely’s zelfdestructieve performances. De enorme installaties die Tinguely tussen 1960-1970 maakte (Homage to New York, Etude pour une fin du monde No. 1, Study for an End of the World No. 2 en La Vittoria) hadden als doel zichzelf luidruchtig en spectaculair te vernietigen. Daarnaast worden de tentoonstellingen Bewogen Beweging (1961) en Dylaby (1962) die Tinguely in het Stedelijk Museum heeft georganiseerd belicht, net als zijn latere enorme sculpturen, HON – en katedral (1966), Crocrodrome (1977) en het spectaculaire Le Cyclop (1969–1994), dat buiten Parijs nog steeds te bezoeken is. Als sluitstuk van de tentoonstelling, en een Nederlandse primeur, wordt Tinguely’s monumentale Mengele-Totentanz (1986) gepresenteerd: een duistere installatie met schaduwspel, die Tinguely maakte naar aanleiding van een verwoestende brand waarvan hij ooggetuige was. Het werk is opgebouwd uit overblijfselen van de brand: verkoolde balken, landbouwmachines (van de firma Mengele) en dierenskeletten. Het resultaat is een gigantische memento mori, die ook verwijst naar de concentratiekampen van de Nazi’s. De bewegingen en hoge schelle geluiden zorgen voor een sacrale en macabere sfeer.

-Spel, interactie en spektakel!

Voor Jean Tinguely was zijn werk een verzet tegen de conventionele statische kunst(wereld); hij wilde spel en experiment voorop zetten. Voor hem hoefde de bezoeker niet meer in een steriele witte ruimte op afstand naar een verstild schilderij te kijken. Met zijn kinetische kunst zette hij zowel de kunst als de kunstgeschiedenis in beweging en verkende hij de grenzen tussen kunst en leven. Met zijn do-it-yourself tekenmachines bekritiseerde Tinguely de rol van de kunstenaar en de elitaire positie van kunst in de samenleving. Hij verwierp de uniciteit van ‘de hand van de kunstenaar’ door bezoekers zelf werken in elkaar te laten zetten.

Samenwerking stond centraal in zijn loopbaan: met kunstenaars als Daniel Spoerri, Niki de Saint Phalle (ook zijn echtgenote), Yves Klein, het ZERO-netwerk, maar ook met museumdirecteuren als Pontus Hultén, Willem Sandberg en Paul Wember. Tinguely speelde een belangrijke rol in deze netwerken, als leider, inspirator, en verbinder. Zijn charismatische, stoere persoonlijkheid en het eclatante succes waarmee hij zijn werk (en zichzelf) in de openbare ruimte presenteerde, droegen daar in belangrijke mate aan bij.

-Relatie met Amsterdam en het Stedelijk

Amsterdam heeft een dynamische geschiedenis met Tinguely. Vooral de mede door Tinguely samengestelde tentoonstellingen Bewogen Beweging (1961) en Dylaby (1962) in het Stedelijk Museum getuigen van het nauwe contact. Hij bracht niet alleen zijn kinetische Méta machines, maar ook zijn internationale avant-gardenetwerk naar Nederland en liet een blijvende indruk achter bij het publiek, dat deze experimentele tentoonstellingen in grote aantallen bezocht. Een innige band met Willem Sandberg, toenmalig directeur van het Stedelijk Museum, en curator Ad Petersen leidde tot verschillende retrospectieven en aankopen voor de collectie (dertien sculpturen, waaronder zijn beroemde tekenmachine Méta-Matic No. 10 uit 1959, Gismo uit 1960 en de enorme Méta II uit 1971).

# Meer info op website Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

-Catalogus

-Catalogus

Bij de tentoonstelling verschijnt een catalogus, gebaseerd op meerjarig onderzoek van het Stedelijk Museum en Kunstpalast Düsseldorf, met essays van onder meer Margriet Schavemaker, Barbara Til en Beat Wismer.

Jean Tinguely – Machinespektakel

Grootste overzicht ooit in Nederland van veelzijdige avant-gardekunstenaar

1 oktober 2016 – 5 maart 2017

Stedelijk Museum

Postbus 75082

1070 AB Amsterdam

T +31 (0)20 5732 911

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, FDM Art Gallery, Jean Tinguely & Niki de Saint Phalle, Sculpture

Foam Magazine #43: Ai Weiwei – Freedom of Expression under Surveillance

Foam Magazine #43: Ai Weiwei – Freedom of Expression under Surveillance

Foam is proud to launch the brand new and unique Foam Magazine, which was made in close collaboration with world-renowned Chinese contemporary artist and activist Ai Weiwei (1957, Beijing). Weiwei is guest editor for this issue that is entirely dedicated to the theme ‘Freedom of Expression under Surveillance’. Ai Weiwei himself is the central point of the magazine, as an artist under constant surveillance by the Chinese government. The magazine contains images he made while documenting his life by using Instagram and webcams, but also pays attention to Ai Weiwei’s constant endeavour to keep a sharp eye on the ones surveilling him.

Freedom of Expression under Surveillance

Freedom of Expression under Surveillance

Containing an interview with, and quotes by the artist Foam Magazine #43 is divided into four parts: ‘Sousveillance”, ‘Self Surveillance’, ‘Urban Surveillance’ and ‘Art and Surveillance’. It reports on the way the artist worked the last few years. Instagram and Twitter became the means by which Ai Weiwei shared virtually every aspect of his life with a steadily growing multitude of followers all over the world. Part of the issue shows a selection of the endless stream of images posted on Instagram by Ai Weiwei. In another part Weiwei shares stills from the ‘Weiweicam’ he directed at himself 24/7. Foam Magazine #43 documents crucial and highly eventful period in the life of one of the most important artists of our age.

About Ai Weiwei

Ai Weiwei is an influential Chinese contemporary artist and activist. As a political activist, he has been openly criticizing the Chinese Government’s stance on democracy and human rights. In 2011, following his arrest at Beijing Capital International Airport he was held for 81 days without any official charges being filed. Recently he had his passport returned to him and was given the opportunity to travel abroad. Among art works by Ai Weiwei are Fairytale (2007), produced for Documenta 12, and Sunflower Seeds, an installation in London’s Tate Modern in 2010. A major solo exhibition of his work is currently on show at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

ISBN 9789491727825

Published December 2015

288 pages + 4 cover pages front + back

Printed on selected specialized paper

Swiss bound

300x230x25 mm

€22,50

# More information: www.foam.org

Photo Anton K. (FdM): Protest in Berlin, Linienstrasse, 2011

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Ai Weiwei, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, Photography, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

The Book

The Book

by H. P. Lovecraft

My memories are very confused. There is even much doubt as to where they begin; for at times I feel appalling vistas of years stretching behind me, while at other times it seems as if the present moment were an isolated point in a grey, formless infinity. I am not even certain how I am communicating this message. While I know I am speaking, I have a vague impression that some strange and perhaps terrible mediation will be needed to bear what I say to the points where I wish to be heard. My identity, too, is bewilderingly cloudy. I seem to have suffered a great shock—perhaps from some utterly monstrous outgrowth of my cycles of unique, incredible experience.

These cycles of experience, of course, all stem from that worm-riddled book. I remember when I found it—in a dimly lighted place near the black, oily river where the mists always swirl. That place was very old, and the ceiling-high shelves full of rotting volumes reached back endlessly through windowless inner rooms and alcoves. There were, besides, great formless heaps of books on the floor and in crude bins; and it was in one of these heaps that I found the thing. I never learned its title, for the early pages were missing; but it fell open toward the end and gave me a glimpse of something which sent my senses reeling.

There was a formula—a sort of list of things to say and do—which I recognised as something black and forbidden; something which I had read of before in furtive paragraphs of mixed abhorrence and fascination penned by those strange ancient delvers into the universe’s guarded secrets whose decaying texts I loved to absorb. It was a key—a guide—to certain gateways and transitions of which mystics have dreamed and whispered since the race was young, and which lead to freedoms and discoveries beyond the three dimensions and realms of life and matter that we know. Not for centuries had any man recalled its vital substance or known where to find it, but this book was very old indeed. No printing-press, but the hand of some half-crazed monk, had traced these ominous Latin phrases in uncials of awesome antiquity.

I remember how the old man leered and tittered, and made a curious sign with his hand when I bore it away. He had refused to take pay for it, and only long afterward did I guess why. As I hurried home through those narrow, winding, mist-choked waterfront streets I had a frightful impression of being stealthily followed by softly padding feet. The centuried, tottering houses on both sides seemed alive with a fresh and morbid malignity—as if some hitherto closed channel of evil understanding had abruptly been opened. I felt that those walls and overhanging gables of mildewed brick and fungous plaster and timber—with fishy, eye-like, diamond-paned windows that leered—could hardly desist from advancing and crushing me . . . yet I had read only the least fragment of that blasphemous rune before closing the book and bringing it away.

I remember how I read the book at last—white-faced, and locked in the attic room that I had long devoted to strange searchings. The great house was very still, for I had not gone up till after midnight. I think I had a family then—though the details are very uncertain—and I know there were many servants. Just what the year was, I cannot say; for since then I have known many ages and dimensions, and have had all my notions of time dissolved and refashioned. It was by the light of candles that I read—I recall the relentless dripping of the wax—and there were chimes that came every now and then from distant belfries. I seemed to keep track of those chimes with a peculiar intentness, as if I feared to hear some very remote, intruding note among them.

Then came the first scratching and fumbling at the dormer window that looked out high above the other roofs of the city. It came as I droned aloud the ninth verse of that primal lay, and I knew amidst my shudders what it meant. For he who passes the gateways always wins a shadow, and never again can he be alone. I had evoked—and the book was indeed all I had suspected. That night I passed the gateway to a vortex of twisted time and vision, and when morning found me in the attic room I saw in the walls and shelves and fittings that which I had never seen before.

Nor could I ever after see the world as I had known it. Mixed with the present scene was always a little of the past and a little of the future, and every once-familiar object loomed alien in the new perspective brought by my widened sight. From then on I walked in a fantastic dream of unknown and half-known shapes; and with each new gateway crossed, the less plainly could I recognise the things of the narrow sphere to which I had so long been bound. What I saw about me none else saw; and I grew doubly silent and aloof lest I be thought mad. Dogs had a fear of me, for they felt the outside shadow which never left my side. But still I read more—in hidden, forgotten books and scrolls to which my new vision led me—and pushed through fresh gateways of space and being and life-patterns toward the core of the unknown cosmos.

I remember the night I made the five concentric circles of fire on the floor, and stood in the innermost one chanting that monstrous litany the messenger from Tartary had brought. The walls melted away, and I was swept by a black wind through gulfs of fathomless grey with the needle-like pinnacles of unknown mountains miles below me. After a while there was utter blackness, and then the light of myriad stars forming strange, alien constellations. Finally I saw a green-litten plain far below me, and discerned on it the twisted towers of a city built in no fashion I had ever known or read of or dreamed of. As I floated closer to that city I saw a great square building of stone in an open space, and felt a hideous fear clutching at me. I screamed and struggled, and after a blankness was again in my attic room, sprawled flat over the five phosphorescent circles on the floor. In that night’s wandering there was no more of strangeness than in many a former night’s wandering; but there was more of terror because I knew I was closer to those outside gulfs and worlds than I had ever been before. Thereafter I was more cautious with my incantations, for I had no wish to be cut off from my body and from the earth in unknown abysses whence I could never return.

The Book (1933?)

by H. P. Lovecraft (1890 – 1937)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive K-L, Lovecraft, H.P., Tales of Mystery & Imagination

NEW YORK: IAN L. MUNRO, PUBLISHER, 24 AND 26 VANDEWATER STREET

NEW YORK: IAN L. MUNRO, PUBLISHER, 24 AND 26 VANDEWATER STREET

WHY ARE THE MADAME MORA’S CORSETS A MARVEL OF COMFORT AND ELEGANCE!?!

Try them and you will Find

WHY they need no breaking in, but feel easy at once.

WHY they are liked by Ladies of full figure.

WHY they do not break down over the hips, and

WHY the celebrated French curved band prevents any wrinkling or stretching at the sides.

WHY dressmakers delight in fitting dresses over them.

WHY merchants say they give better satisfaction than any others.

WHY they take pains to recommend them.

Their popularity has induced many imitations, which are frauds, high at any price. Buy only the genuine, stamped Madame Mora’s. Sold by all leading dealers with this GUARANTEE: that if not perfectly satisfactory upon trial the money will be refunded.

L. KRAUS & CO., Manufacturers, Birmingham, Conn.

INTRODUCTION

SINCE my experiences in Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum were published in the World I have received hundreds of letters in regard to it. The edition containing my story long since ran out, and I have been prevailed upon to allow it to be published in book form, to satisfy the hundreds who are yet asking for copies.

I am happy to be able to state as a result of my visit to the asylum and the exposures consequent thereon, that the City of New York has appropriated $1,000,000 more per annum than ever before for the care of the insane. So I have at least the satisfaction of knowing that the poor unfortunates will be the better cared for because of my work.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter 1: A delicate mission)

by Nellie Bly

On the 22d of September I was asked by the World if I could have myself committed to one of the asylums for the insane in New York, with a view to writing a plain and unvarnished narrative of the treatment of the patients therein and the methods of management, etc. Did I think I had the courage to go through such an ordeal as the mission would demand? Could I assume the characteristics of insanity to such a degree that I could pass the doctors, live for a week among the insane without the authorities there finding out that I was only a “chiel amang ’em takin’ notes?” I said I believed I could. I had some faith in my own ability as an actress and thought I could assume insanity long enough to accomplish any mission intrusted to me. Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island? I said I could and I would. And I did.

My instructions were simply to go on with my work as soon as I felt that I was ready. I was to chronicle faithfully the experiences I underwent, and when once within the walls of the asylum to find out and describe its inside workings, which are always, so effectually hidden by white-capped nurses, as well as by bolts and bars, from the knowledge of the public. “We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time. But I am afraid of that chronic smile of yours,” said the editor. “I will smile no more,” I said, and I went away to execute my delicate and, as I found out, difficult mission.

My instructions were simply to go on with my work as soon as I felt that I was ready. I was to chronicle faithfully the experiences I underwent, and when once within the walls of the asylum to find out and describe its inside workings, which are always, so effectually hidden by white-capped nurses, as well as by bolts and bars, from the knowledge of the public. “We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time. But I am afraid of that chronic smile of yours,” said the editor. “I will smile no more,” I said, and I went away to execute my delicate and, as I found out, difficult mission.

If I did get into the asylum, which I hardly hoped to do, I had no idea that my experiences would contain aught else than a simple tale of life in an asylum.

That such an institution could be mismanaged, and that cruelties could exist ‘neath its roof, I did not deem possible. I always had a desire to know asylum

life more thoroughly–a desire to be convinced that the most helpless of God’s creatures, the insane, were cared for kindly and properly. The many stories I

had read of abuses in such institutions I had regarded as wildly exaggerated or else romances, yet there was a latent desire to know positively.

I shuddered to think how completely the insane were in the power of their keepers, and how one could weep and plead for release, and all of no avail, if

the keepers were so minded. Eagerly I accepted the mission to learn the inside workings of the Blackwell Island Insane Asylum.

“How will you get me out,” I asked my editor, “after I once get in?”

“I do not know,” he replied, “but we will get you out if we have to tell who you are, and for what purpose you feigned insanity–only get in.”

I had little belief in my ability to deceive the insanity experts, and I think my editor had less.

All the preliminary preparations for my ordeal were left to be planned by myself. Only one thing was decided upon, namely, that I should pass under the pseudonym of Nellie Brown, the initials of which would agree with my own name and my linen, so that there would be no difficulty in keeping track of my

movements and assisting me out of any difficulties or dangers I might get into.

There were ways of getting into the insane ward, but I did not know them. I might adopt one of two courses. Either I could feign insanity at the house of friends, and get myself committed on the decision of two competent physicians, or I could go to my goal by way of the police courts.

Nellie practices insanity at home

On reflection I thought it wiser not to inflict myself upon my friends or to get any good-natured doctors to assist me in my purpose. Besides, to get to Blackwell’s Island my friends would have had to feign poverty, and, unfortunately for the end I had in view, my acquaintance with the struggling poor, except my own self, was only very superficial. So I determined upon the plan which led me to the successful accomplishment of my mission. I succeeded in getting committed to the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island, where I spent ten days and nights and had an experience which I shall never forget. I took upon myself to enact the part of a poor, unfortunate crazy girl, and felt it my duty not to shirk any of the disagreeable results that should follow. I became one of the city’s insane wards for that length of time, experienced much, and saw and heard more of the treatment accorded to this helpless class of our population, and when I had seen and heard enough, my release was promptly secured. I left the insane ward with pleasure and regret–pleasure that I was once more able to enjoy the free breath of heaven; regret that I could not have brought with me some of the unfortunate women who lived and suffered with me, and who, I am convinced, are just as sane as I was and am now myself.

But here let me say one thing: From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted the crazier I was thought to be by all except one physician, whose kindness and gentle ways I shall not soon forget.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter 1: A delicate mission)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

Dioraphte Literatour Prijs

De Dioraphte Literatour Prijs bestaat uit een vakjuryprijs en een publieksprijs waarbij jongeren worden opgeroepen te stemmen op genomineerde boeken van de vakjury.

De beste boeken uit 2015 worden door de vakjury uitgelicht en bekroond. De DLP richt zich op alle jongeren van 15-18 jaar.

Je kunt op de website literatour.nu stemmen van 5 t/m 15 september 2016

De genomineerden in de categorie Oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalig zijn:

De genomineerden in de categorie Oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalig zijn:

De IJsmakers van Ernest van der Kwast (De Bezige Bij)

De zee zien van Koos Meinderts (De Fontein)

Het bestand van Arnon Grunberg (Nijgh & Van Ditmar)

Het uur van Zimmerman van Karolien Berkvens (Lebowski)

Oliver van Edward van de Vendel (Querido)

Underdog van Elfie Tromp (De Geus)

In de categorie Vertaald zijn genomineerd:

De naam van mijn broer van Larry Tremblay (Nieuw Amsterdam) en vertaald door Gertrud Maes

Doorgang van David Mitchell (Nieuw Amsterdam) en vertaald door Harm Damsma

Waar het licht is van Jennifer Niven (Moon) en vertaald door Aleid van Eekelen-Benders

Vuur & as van Sabaa Tahir (Luitingh-Sijthoff) en vertaald door Hanneke van Soest

Eerdere winnaars:

In 2015 ging de Dioraphte Literatour Prijs naar De veteraan van Johan Faber (Oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalig), Eleanor & Park van Rainbow Rowell (Vertaald) en Birk van Jaap Robben (Publieksprijs).

Nog meer verhalen:

Nog meer verhalen:

3PAK is een verhalenbundel met drie korte verhalen die speciaal geschreven zijn voor Literatour. Mirjam Mous, Helen Vreeswijk en Alex Boogers zijn de auteurs van de verhalen. De eerste twee verhalen worden online verspreid, het complete 3PAK is te verkrijgen bij de deelnemende bibliotheken & boekhandels.

Verhalen:

Domino Day – Mirjam Mous

De Rebel – Helen Vreeswijk

Vergeet Amy – Alex Boogers

Docenten opgelet:

Bij Literatour & 3Pak zijn er mogelijkheden tot klassikale lessen. Hiervoor kunt u terecht op de Voor Scholen pagina van de website van Literatour.

# Meer info op website Literatour

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, Elfie Tromp, FICTION & NONFICTION ARCHIVE, Literary Events

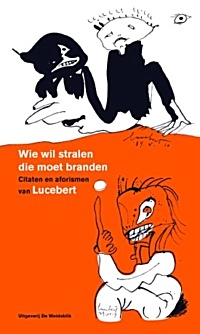

‘Alles van waarde is weerloos’, staat er in grote neonletters op het dak van een Nederlandse verzekeraar. Het is een tot aforisme, zelfs tot spreekwoord geworden versregel van Lucebert.

‘Alles van waarde is weerloos’, staat er in grote neonletters op het dak van een Nederlandse verzekeraar. Het is een tot aforisme, zelfs tot spreekwoord geworden versregel van Lucebert.

Lucebert werd en wordt weleens getypeerd als een ontoegankelijk dichter. Des te opmerkelijker is het hoeveel sporen hij heeft achtergelaten in de omgangstaal. In tal van niet-literaire teksten wordt onnadrukkelijk of juist expliciet verwezen naar passages uit zijn gedichten: ‘de ruimte van het volledig leven’, ‘omroeper van oproer’, ‘dichters van fluweel’, ‘het proefondervindelijk gedicht’, ‘de blote kont van de kunst’, ‘ritselende revolutie’, ‘overal zanikt bagger’ – het is maar een greep uit het dichterlijk erfgoed van Lucebert dat zich in de omgangstaal heeft genesteld.

In Wie wil stralen die moet branden zijn deze citaten en aforismen uit het oeuvre van Lucebert bijeengebracht door Ton den Boon (hoofdredacteur van de Dikke Van Dale), die daarbij een inleiding schreef over de invloed van Lucebert op de Nederlandse taal. Het boekje is verlucht met niet eerder gepubliceerde tekeningen van Lucebert.

Wie wil stralen die moet branden.

Citaten en aforismen van Lucebert – Lucebert, Ton den Boon

Auteurs: Lucebert, Ton den Boon

Vormgeving: Huug Schipper, Studio Tint

Omvang: 96 pagina’s

Afwerking: paperback

Formaat: 12 x 20 cm

ISBN: 9789077767658

€ 7,50

Verschijning: september 2016, De Weideblik

De Weideblik is een middelgrote uitgeverij, gespecialiseerd in uitgaven op het gebied van de beeldende kunst. Veel van onze boeken worden gemaakt in nauwe samenwerking met een kunstenaar (of diens nazaten) en/of een tentoonstellingsinstelling.

# Meer info website Uitgeverij Weideblik

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Lucebert, Lucebert

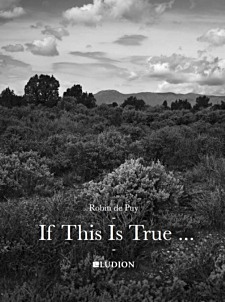

Fotoweek benoemt Robin de Puy (1986) tot vierde Fotograaf des Vaderlands, als opvolger van Ahmet Polat.

Fotoweek benoemt Robin de Puy (1986) tot vierde Fotograaf des Vaderlands, als opvolger van Ahmet Polat.

De Fotograaf des Vaderlands is een jaar lang de ambassadeur van Fotoweek en het gezicht van de Nederlandse professionele fotografie. Rond het thema van Fotoweek 2016 ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’ maakt de Fotograaf des Vaderlands, speciaal voor Fotoweek, een bijzondere fotoserie die wordt getoond tijdens het tweejaarlijkse internationale fotofestival BredaPhoto dat dit jaar plaatsvindt van 15 september tot 30 oktober.

De foto’s van de Nederlandse portretfotograaf Robin de Puy zijn altijd intiem en vol leven. Haar stijl is karakteristiek: zwart-wit, en balancerend op de rand van documentairefotografie. Haar werk is vaak een combinatie van fotografie en film, want; taal en beweging zijn voor de Puy een essentieel onderdeel van identiteit.

Fotoweek is trots Robin de Puy te presenteren als vierde Fotograaf des Vaderlands. Ze is een fotograaf met een succesvolle carrière, een perfect boegbeeld voor het vak fotografie. Vanwege de Puy’s aansprekende talent om karakters bloot te leggen, kijkt Fotoweek uit naar haar nieuwe serie in het thema van 2016 ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’.

Voor Fotoweek maakt de Puy een intiem portret van de oom van haar vader, Jan Mallan, een 81-jarige man met Alzheimer. Ze heeft een warme band met deze man, die begin jaren zestig met zijn Deense vrouw naar Denemarken verhuisde. Ze was naar eigen zeggen bang om hem te verliezen, bang dat zijn uniciteit verloren zou gaan door de ziekte. Maar wat neemt de ziekte precies weg van zijn identiteit? Wat komt ervoor in de plaats?

Op 15 september worden de fotoserie en film onthuld in een tentoonstelling op het internationale fotofestival BredaPhoto. Het thema van BredaPhoto 2016 is ‘YOU’. Een interessante combinatie met het thema van de Fotoweek, want wat is een ‘ík’, zonder een ‘jij’?

Biografie Robin de Puy

Robin de Puy (1986) studeerde in 2009 af aan de Fotoacademie Rotterdam. Vanaf deze periode nam haar carrière een spurt en won zij met haar serie ‘Meisjes in de prostitutie’ in 2009 de Photo Academy Award. Vervolgens won zij In 2013 de Nationale Portretprijs en was haar eerste solotentoonstelling in het Fotomuseum Den Haag. Haar werk is gepubliceerd in nationale en internationale bladen, waaronder New York Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, ELLE, L’Officiel, de Volkskrant en LINDA.

Thema Fotoweek 2016: ‘Kijk: Dit ben ik’

Met het thema van dit jaar, ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’, wordt de nadruk gelegd op portretfotografie. En op de wisselwerking tussen de geportretteerde en de fotograaf. Wie ben jij? Hoe kijk je naar jezelf? Wat wil je van jezelf laten zien? Weerspiegelt jouw portret je ware ik, of is dat slechts het beeld dat de fotograaf van je heeft? Hoeveel van zichzelf kan de fotograaf overbrengen in het portret van een ander? Fotoweek legt de focus op het individu: zowel voor als achter de lens.

Tijdens de Fotoweek zullen verschillende instellingen pop-up studio’s organiseren waar bezoekers hun portret kunnen laten maken door bekende en onbekende portretfotografen. Verder zijn er activiteiten en programma’s in verschillende musea en culturele instellingen, zoals het Groninger Museum, het Joods Historisch Museum, de Kunsthal Rotterdam, het Nationaal Archief in Den Haag en het Nieuwe Instituut. Bezoek deze zomer onze website www.defotoweek.nl voor een overzicht van de diverse activiteiten.

Fotograaf des Vaderlands: een traditie

In 2013 benoemde Fotoweek Ilvy Njiokiktjien tot de eerste Fotograaf des Vaderlands. Zij maakte voor het thema ‘Kijk! Mijn Familie’ een fotoserie over Hollandse verjaardagen. In 2014 werd Njiokiktjien opgevolgd door Koen Hauser. Voor Fotoweek 2014 maakte Hauser een fotoserie passend bij het thema ‘Kijk! Mijn Geluk’ die tijdens Fotoweek 2014 onthuld werd en te zien was bij het internationale fotografiefestival BredaPhoto. De huidige Fotograaf des Vaderlands, Ahmet Polat, zal op woensdag 7 september 2016 opgevolgd worden door een nieuwe Fotograaf des Vaderlands.

Van vrijdag 9 t/m zondag 18 september 2016, vindt de vierde editie van Fotoweek plaats. Tien dagen lang zet Fotoweek de schijnwerpers op fotografie. De start van Fotoweek wordt gemarkeerd door de bekendmaking van de nieuwe Fotograaf des Vaderlands op 7 september. Het thema dit jaar is ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, FDM Art Gallery, Photography, PRESS & PUBLISHING, Robin de Puy

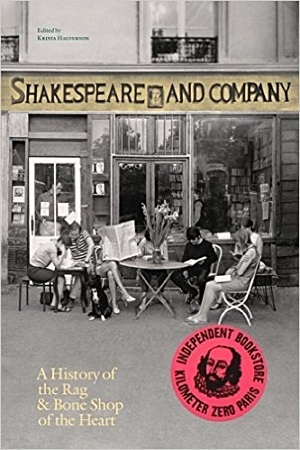

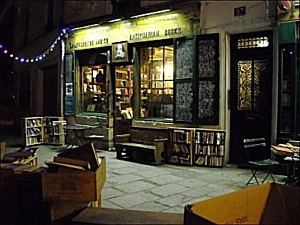

A Biography of a Bookstore – Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart – by Krista Halverson (Editor) – Sylvia Whitman (Afterword) – Jeannette Winterson (Foreword)

A Biography of a Bookstore – Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart – by Krista Halverson (Editor) – Sylvia Whitman (Afterword) – Jeannette Winterson (Foreword)

A copiously illustrated account of the famed Paris bookstore on its 65th anniversary.

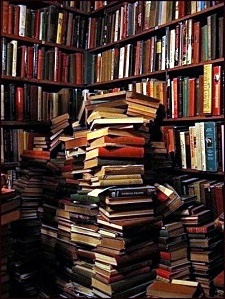

For almost 70 years, Shakespeare and Company has been a home-away-from-home for celebrated writers—including James Baldwin, Jorge Luis Borges, A. M. Homes, and Dave Eggers—as well as for young, aspiring authors and poets. Visitors are invited to read in the library, share a pot of tea, and sometimes even live in the shop itself, sleeping in beds tucked among the towering shelves of books. Since 1951, more than 30,000 have slept at the “rag and bone shop of the heart.”

This first-ever history of the legendary bohemian bookstore in Paris interweaves essays and poetry from dozens of writers associated with the shop–Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Ethan Hawke, Robert Stone and Jeanette Winterson, among others–with hundreds of never-before-seen archival pieces, including photographs of James Baldwin, William Burroughs and Langston Hughes, plus a foreword by the celebrated British novelist Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the daughter of the store’s founder, George Whitman. The book has been edited by Krista Halverson, director of the newly founded Shakespeare and Company publishing house.

This first-ever history of the legendary bohemian bookstore in Paris interweaves essays and poetry from dozens of writers associated with the shop–Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Ethan Hawke, Robert Stone and Jeanette Winterson, among others–with hundreds of never-before-seen archival pieces, including photographs of James Baldwin, William Burroughs and Langston Hughes, plus a foreword by the celebrated British novelist Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the daughter of the store’s founder, George Whitman. The book has been edited by Krista Halverson, director of the newly founded Shakespeare and Company publishing house.

George Whitman opened his bookstore in a tumbledown 16th-century building just across the Seine from Notre-Dame in 1951, a decade after the original Shakespeare and Company had closed. Run by Sylvia Beach, it had been the meeting place for the Lost Generation and the first publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses. (This book includes an illustrated adaptation of Beach’s memoir.) Since Whitman picked up the mantle, Shakespeare and Company has served as a home-away-from-home for many celebrated writers, from Jorge Luis Borges to Ray Bradbury, A.M. Homes to Dave Eggers, as well as for young authors and poets. Visitors are invited not only to read the books in the library and to share a pot of tea, but sometimes also to live in the bookstore itself–all for free.

George Whitman opened his bookstore in a tumbledown 16th-century building just across the Seine from Notre-Dame in 1951, a decade after the original Shakespeare and Company had closed. Run by Sylvia Beach, it had been the meeting place for the Lost Generation and the first publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses. (This book includes an illustrated adaptation of Beach’s memoir.) Since Whitman picked up the mantle, Shakespeare and Company has served as a home-away-from-home for many celebrated writers, from Jorge Luis Borges to Ray Bradbury, A.M. Homes to Dave Eggers, as well as for young authors and poets. Visitors are invited not only to read the books in the library and to share a pot of tea, but sometimes also to live in the bookstore itself–all for free.

More than 30,000 people have stayed at Shakespeare and Company, fulfilling Whitman’s vision of a “socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore.” Through the prism of the shop’s history, the book traces the lives of literary expats in Paris from 1951 to the present, touching on the Beat Generation, civil rights, May ’68 and the feminist movement–all while pondering that perennial literary question, “What is it about writers and Paris?”

In this first-ever history of the bookstore, photographs and ephemera are woven together with personal essays, diary entries, and poems from writers including Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Sylvia Beach, Nathan Englander, Dervla Murphy, Jeet Thayil, David Rakoff, Ian Rankin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke.

In this first-ever history of the bookstore, photographs and ephemera are woven together with personal essays, diary entries, and poems from writers including Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Sylvia Beach, Nathan Englander, Dervla Murphy, Jeet Thayil, David Rakoff, Ian Rankin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke.

With hundreds of images, it features Tumbleweed autobiographies, precious historical documents, and beautiful photographs, including ones of such renowned guests as William Burroughs, Henry Miller, Langston Hughes, Alberto Moravia, Zadie Smith, Jimmy Page, and Marilynne Robinson.

Tracing more than 100 years in the French capital, the book touches on the Lost Generation and the Beats, the Cold War, May ’68, and the feminist movement—all while reflecting on the timeless allure of bohemian life in Paris.

Krista Halverson is the director of Shakespeare and Company bookstore’s publishing venture. Previously, she was the managing editor of Zoetrope: All-Story, the art and literary quarterly published by Francis Ford Coppola, which has won several National Magazine Awards for Fiction and numerous design prizes. She was responsible for the magazine’s art direction, working with guest designers including Lou Reed, Kara Walker, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Zaha Hadid, Wim Wenders and Tom Waits, among others.

Krista Halverson is the director of Shakespeare and Company bookstore’s publishing venture. Previously, she was the managing editor of Zoetrope: All-Story, the art and literary quarterly published by Francis Ford Coppola, which has won several National Magazine Awards for Fiction and numerous design prizes. She was responsible for the magazine’s art direction, working with guest designers including Lou Reed, Kara Walker, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Zaha Hadid, Wim Wenders and Tom Waits, among others.

Jeanette Winterson‘s first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, was published in 1985. In 1992 she was one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists. She has won numerous awards and is published around the world. Her memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, was an international bestseller. Her latest novel, The Gap of Time, is a “cover version” of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale.

Sylvia Whitman is the owner of Shakespeare and Company bookstore, which her father opened in 1951. She took on management of the shop in 2004, when she was 23, and now co-manages the bookstore with her partner, David Delannet. Together they have opened an adjoining cafe, as well as launched a literary festival, a contest for unpublished novellas, and a publishing arm.

“I created this bookstore like a man would write a novel, building each room like a chapter, and I like people to open the door the way they open a book, a book that leads into a magic world in their imaginations.” —George Whitman, founder

Drawing on a century’s worth of never-before-seen archives, this first history of the bookstore features more than 300 images and 70 editorial contributions from shop visitors such as Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke. With a foreword by Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the 400-page book is fully illustrated with color throughout.

Drawing on a century’s worth of never-before-seen archives, this first history of the bookstore features more than 300 images and 70 editorial contributions from shop visitors such as Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke. With a foreword by Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the 400-page book is fully illustrated with color throughout.

Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart by Krista Halverson

Foreword by: Jeanette Winterson

Epilogue by: Sylvia Whitman

Contributions by:

Allen Ginsberg

Anaïs Nin

Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Sylvia Beach

Nathan Englander

Dervla Murphy

Ian Rankin

Kate Tempest

Ethan Hawke

David Rakoff

Publisher: Shakespeare and Company Paris

Publication date: August 2016

Hardback – ISBN: 979-1-09610-100-9

€ 35.00

Publication country:France

Pages:384

Weight: 1501.000g.

# More information on website Shakespeare & Company

Photos: Shakespeare & Comp, Jef van Kempen FDM

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, BEAT GENERATION, Borges J.L., Burroughs, William S., Ernest Hemingway, Ginsberg, Allen, J.A. Woolf, James Baldwin, Kate/Kae Tempest, Samuel Beckett, Shakespeare, William, Tempest, Kate/Kae

His First Operation

His First Operation

by Arthur Conan Doyle

It was the first day of the winter session, and the third year’s man was walking with the first year’s man. Twelve o’clock was just booming out from the Tron Church.

“Let me see,” said the third year’s man. “You have never seen an operation?”

“Never.”

“Then this way, please. This is Rutherford’s historic bar. A glass of sherry, please, for this gentleman. You are rather sensitive, are you not?”

“My nerves are not very strong, I am afraid.”

“Hum! Another glass of sherry for this gentleman. We are going to an operation now, you know.”

The novice squared his shoulders and made a gallant attempt to look unconcerned.

“Nothing very bad—eh?”

“Well, yes—pretty bad.”

“An—an amputation?”

“No; it’s a bigger affair than that.”

“I think—I think they must be expecting me at home.”

“There’s no sense in funking. If you don’t go to-day, you must to-morrow. Better get it over at once. Feel pretty fit?”

“Oh, yes; all right!” The smile was not a success.

“One more glass of sherry, then. Now come on or we shall be late. I want you to be well in front.”

“Surely that is not necessary.”

“Oh, it is far better! What a drove of students! There are plenty of new men among them. You can tell them easily enough, can’t you? If they were going down to be operated upon themselves, they could not look whiter.”

“I don’t think I should look as white.”

“Well, I was just the same myself. But the feeling soon wears off. You see a fellow with a face like plaster, and before the week is out he is eating his lunch in the dissecting rooms. I’ll tell you all about the case when we get to the theatre.”

The students were pouring down the sloping street which led to the infirmary—each with his little sheaf of note-books in his hand. There were pale, frightened lads, fresh from the high schools, and callous old chronics, whose generation had passed on and left them. They swept in an unbroken, tumultuous stream from the university gate to the hospital. The figures and gait of the men were young, but there was little youth in most of their faces. Some looked as if they ate too little—a few as if they drank too much. Tall and short, tweed-coated and black, round-shouldered, bespectacled, and slim, they crowded with clatter of feet and rattle of sticks through the hospital gate. Now and again they thickened into two lines, as the carriage of a surgeon of the staff rolled over the cobblestones between.

“There’s going to be a crowd at Archer’s,” whispered the senior man with suppressed excitement. “It is grand to see him at work. I’ve seen him jab all round the aorta until it made me jumpy to watch him. This way, and mind the whitewash.”

They passed under an archway and down a long, stone-flagged corridor, with drab-coloured doors on either side, each marked with a number. Some of them were ajar, and the novice glanced into them with tingling nerves. He was reassured to catch a glimpse of cheery fires, lines of white-counterpaned beds, and a profusion of coloured texts upon the wall. The corridor opened upon a small hall, with a fringe of poorly clad people seated all round upon benches. A young man, with a pair of scissors stuck like a flower in his buttonhole and a note-book in his hand, was passing from one to the other, whispering and writing.

“Anything good?” asked the third year’s man.

“You should have been here yesterday,” said the out-patient clerk, glancing up. “We had a regular field day. A popliteal aneurism, a Colles’ fracture, a spina bifida, a tropical abscess, and an elephantiasis. How’s that for a single haul?”

“I’m sorry I missed it. But they’ll come again, I suppose. What’s up with the old gentleman?”

A broken workman was sitting in the shadow, rocking himself slowly to and fro, and groaning. A woman beside him was trying to console him, patting his shoulder with a hand which was spotted over with curious little white blisters.

“It’s a fine carbuncle,” said the clerk, with the air of a connoisseur who describes his orchids to one who can appreciate them. “It’s on his back and the passage is draughty, so we must not look at it, must we, daddy? Pemphigus,” he added carelessly, pointing to the woman’s disfigured hands. “Would you care to stop and take out a metacarpal?”

“No, thank you. We are due at Archer’s. Come on!” and they rejoined the throng which was hurrying to the theatre of the famous surgeon.

The tiers of horseshoe benches rising from the floor to the ceiling were already packed, and the novice as he entered saw vague curving lines of faces in front of him, and heard the deep buzz of a hundred voices, and sounds of laughter from somewhere up above him. His companion spied an opening on the second bench, and they both squeezed into it.

“This is grand!” the senior man whispered. “You’ll have a rare view of it all.”

Only a single row of heads intervened between them and the operating table. It was of unpainted deal, plain, strong, and scrupulously clean. A sheet of brown water-proofing covered half of it, and beneath stood a large tin tray full of sawdust. On the further side, in front of the window, there was a board which was strewed with glittering instruments—forceps, tenacula, saws, canulas, and trocars. A line of knives, with long, thin, delicate blades, lay at one side. Two young men lounged in front of this, one threading needles, the other doing something to a brass coffee-pot-like thing which hissed out puffs of steam.

“That’s Peterson,” whispered the senior, “the big, bald man in the front row. He’s the skin-grafting man, you know. And that’s Anthony Browne, who took a larynx out successfully last winter. And there’s Murphy, the pathologist, and Stoddart, the eye-man. You’ll come to know them all soon.”

“Who are the two men at the table?”

“Nobody—dressers. One has charge of the instruments and the other of the puffing Billy. It’s Lister’s antiseptic spray, you know, and Archer’s one of the carbolic-acid men. Hayes is the leader of the cleanliness-and-cold-water school, and they all hate each other like poison.”

A flutter of interest passed through the closely packed benches as a woman in petticoat and bodice was led in by two nurses. A red woolen shawl was draped over her head and round her neck. The face which looked out from it was that of a woman in the prime of her years, but drawn with suffering, and of a peculiar beeswax tint. Her head drooped as she walked, and one of the nurses, with her arm round her waist, was whispering consolation in her ear. She gave a quick side-glance at the instrument table as she passed, but the nurses turned her away from it.

“What ails her?” asked the novice.

“Cancer of the parotid. It’s the devil of a case; extends right away back behind the carotids. There’s hardly a man but Archer would dare to follow it. Ah, here he is himself!”

As he spoke, a small, brisk, iron-grey man came striding into the room, rubbing his hands together as he walked. He had a clean-shaven face, of the naval officer type, with large, bright eyes, and a firm, straight mouth. Behind him came his big house-surgeon, with his gleaming pince-nez, and a trail of dressers, who grouped themselves into the corners of the room.

“Gentlemen,” cried the surgeon in a voice as hard and brisk as his manner, “we have here an interesting case of tumour of the parotid, originally cartilaginous but now assuming malignant characteristics, and therefore requiring excision. On to the table, nurse! Thank you! Chloroform, clerk! Thank you! You can take the shawl off, nurse.”

The woman lay back upon the water-proofed pillow, and her murderous tumour lay revealed. In itself it was a pretty thing—ivory white, with a mesh of blue veins, and curving gently from jaw to chest. But the lean, yellow face and the stringy throat were in horrible contrast with the plumpness and sleekness of this monstrous growth. The surgeon placed a hand on each side of it and pressed it slowly backwards and forwards.

“Adherent at one place, gentlemen,” he cried. “The growth involves the carotids and jugulars, and passes behind the ramus of the jaw, whither we must be prepared to follow it. It is impossible to say how deep our dissection may carry us. Carbolic tray. Thank you! Dressings of carbolic gauze, if you please! Push the chloroform, Mr. Johnson. Have the small saw ready in case it is necessary to remove the jaw.”

The patient was moaning gently under the towel which had been placed over her face. She tried to raise her arms and to draw up her knees, but two dressers restrained her. The heavy air was full of the penetrating smells of carbolic acid and of chloroform. A muffled cry came from under the towel, and then a snatch of a song, sung in a high, quavering, monotonous voice:

“He says, says he,

If you fly with me

You’ll be mistress of the ice-cream van.

You’ll be mistress of the——”

It mumbled off into a drone and stopped. The surgeon came across, still rubbing his hands, and spoke to an elderly man in front of the novice.

“Narrow squeak for the Government,” he said.

“Oh, ten is enough.”

“They won’t have ten long. They’d do better to resign before they are driven to it.”

“Oh, I should fight it out.”

“What’s the use. They can’t get past the committee even if they got a vote in the House. I was talking to——”

“Patient’s ready, sir,” said the dresser.

“Talking to McDonald—but I’ll tell you about it presently.” He walked back to the patient, who was breathing in long, heavy gasps. “I propose,” said he, passing his hand over the tumour in an almost caressing fashion, “to make a free incision over the posterior border, and to take another forward at right angles to the lower end of it. Might I trouble you for a medium knife, Mr. Johnson?”

The novice, with eyes which were dilating with horror, saw the surgeon pick up the long, gleaming knife, dip it into a tin basin, and balance it in his fingers as an artist might his brush. Then he saw him pinch up the skin above the tumour with his left hand. At the sight his nerves, which had already been tried once or twice that day, gave way utterly. His head swain round, and he felt that in another instant he might faint. He dared not look at the patient. He dug his thumbs into his ears lest some scream should come to haunt him, and he fixed his eyes rigidly upon the wooden ledge in front of him. One glance, one cry, would, he knew, break down the shred of self-possession which he still retained. He tried to think of cricket, of green fields and rippling water, of his sisters at home—of anything rather than of what was going on so near him.

And yet somehow, even with his ears stopped up, sounds seemed to penetrate to him and to carry their own tale. He heard, or thought that he heard, the long hissing of the carbolic engine. Then he was conscious of some movement among the dressers. Were there groans, too, breaking in upon him, and some other sound, some fluid sound, which was more dreadfully suggestive still? His mind would keep building up every step of the operation, and fancy made it more ghastly than fact could have been. His nerves tingled and quivered. Minute by minute the giddiness grew more marked, the numb, sickly feeling at his heart more distressing. And then suddenly, with a groan, his head pitching forward, and his brow cracking sharply upon the narrow wooden shelf in front of him, he lay in a dead faint.

When he came to himself, he was lying in the empty theatre, with his collar and shirt undone. The third year’s man was dabbing a wet sponge over his face, and a couple of grinning dressers were looking on.

“All right,” cried the novice, sitting up and rubbing his eyes. “I’m sorry to have made an ass of myself.”

“Well, so I should think,” said his companion.

“What on earth did you faint about?”

“I couldn’t help it. It was that operation.”

“What operation?”

“Why, that cancer.”

There was a pause, and then the three students burst out laughing. “Why, you juggins!” cried the senior man, “there never was an operation at all! They found the patient didn’t stand the chloroform well, and so the whole thing was off. Archer has been giving us one of his racy lectures, and you fainted just in the middle of his favourite story.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

His First Operation (#02)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

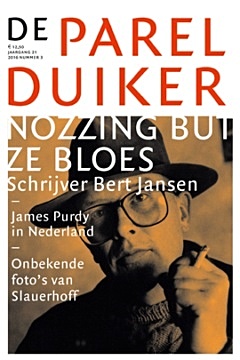

De Parelduiker 2016/3

De Parelduiker 2016/3

Nozzing but ze bloes. Het vergeten schrijversleven van Bert Jansen

Bert Jansen (1949-2002) is de auteur van Nozzing but ze bloes (1975), het gebundelde feuilleton van de jaren zestig, later herdrukt als En nog steeds vlekken in de lakens. Hij publiceerde een groot aantal boeken, maar nog veel meer niet. Zijn archief in het Letterkundig Museum getuigt van vele manuscripten die keer op keer werden geweigerd. Dit lot trof ook het boek dat zijn magnum opus had moeten worden, een biografie van de Drentse blueszanger en streekgenoot Harry Muskee. Voor De Parelduiker ontsluit Rutger Vahl het schrijversarchief van Bert Jansen.

Onbekende foto’s van Slauerhoff

Onlangs kreeg het Letterkundig Museum twee albums met foto’s van Slauerhoff in bezit. Ze zijn afkomstig van Lenie van der Goes, een vrouw die Slauerhoff in 1927 in Soerabaja ontmoette en met wie hij trouwplannen smeedde. Hoewel ze voorkomt in Wim Hazeus Slauerhoff-biografie, is er nog veel onbekend over deze vrouw, die ten faveure van de exotische dichter de brui gaf aan haar kersverse huwelijk met de arts Leendert Eerland. Wie was zij en wie maakte de andere foto’s in het album, waarop Slauerhoff in Macao te zien is?

En verder:

menno voskuil, Ben je in de winterboom. James Purdy en de Nederlandse private press

marco entrop, Tussen wilde zwanen en onsterfelijke nachtegalen.Op verjaarsvisite bij J.C. Bloem

bart slijper, Desperate charges. Tachtigers en sport

hans olink, Het geheim van Buchenwald

jan paul hinrichs, Schoon & haaks

paul arnoldussen, Wout Vuyk (1922-2016)

De Parelduiker is een uitgave van Uitgeverij Bas Lubberhuizen | Postbus 51140 | 1007 EC Amsterdam

# Meer op website De Parelduiker

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Bloem, J.C., LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING, Slauerhoff, Jan

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature