Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Jacques Perk

(1859-1881)

O, noodlot!

Wie naar ons staren, staren naar ons beiden,

Als waren wij gelukkig en verloofd;

Men ziet ons aan, en wenkt met oog en hoofd,

En wil ons vreugd door wedervreugd bereiden.

Mathilde! ik zou u nimmer kunnen leiden

Door ‘t leven! ‘t Noodlot, dat gij wijs gelooft,

Scheidt mij van u, die mijn verdriet me ontrooft

En vroolijk hart…. Ik k…n niet van u scheiden….

En tòch, die Macht, die over ‘t menschdom waakt,

Is wijs, en doet mij wijslijk u verlaten,

Omdat, hoog wezen! Gij me een onding maakt!

Ik leef in ú, en denk en doe als gij,

Ik ga mijzelf, zooals ik nú ben, haten –

Tot dweper, tot een jonkvrouw maakt gij mij…!

(Mathilde – Een Sonnettenkrans in vier boeken – XXVI)

Jacques Perk gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, CLASSIC POETRY, Jacques Perk

.jpg)

Gabriele D’Annunzio

(1863-1938)

I Poeti

Il sogno d’un passato lontano, d’una ignota

stirpe, d’una remota

favola nei Poeti luce. Ai Poeti oscuro

è il sogno del futuro.

Qual contro l’aure avverse una chioma divina,

una fiamma divina,

tal ne la vita splende

l’Anima, si distende,

in dietro effusa pende.

Ospiti fummo (O tu che m’ami: ti sovviene?

Era ne le tue vene

il Ritmo), ospiti fummo in imperi di gloria.

Nativa è la memoria

in noi, dei fiori ardenti su dai cavi alabastri

come tangibili astri,

dei misteri veduti,

degli amori goduti,

degli aromi bevuti.

In qual sera purpurea chiudemmo gli occhi?

Quale fu ne l’ora mortale il nostro dio?

Da quale portentosa ferita

esalammo la vita?

Forse dopo una strage di eroi?

Sotto il profondo ciel d’un letto profondo?

Le nostre spoglie fiera custodì la Chimera

ne la purpurea sera.

E al risveglio improvviso dal sonno secolare

noi vedemmo raggiare

un altro cielo; udimmo altre voci, altri canti;

udimmo tutti i pianti

umani, tutti i pianti umani che la Terra

nel suo cerchio rinserra.

Udimmo tutti i vani gemiti e gli urli insani

e le bestemmie immani.

Udimmo taciturni la querela confusa.

Ma ne l’anima chiusa

l’antichissimo sogno, che fluttuava ancòra,

ebbe una nuova aurora.

E vivemmo; e ingannammo la vita ricordando

quella morte, cantando

dei misteri veduti,

degli amori goduti,

degli aromi bevuti.

Or conviene il silenzio: alto silenzio. Oscuro

è il sogno del futuro.

Nuova morte ci attende. Ma in qual giorno supremo,

o Fato, rivivremo?

Quando i Poeti al mondo canteranno su corde

d’oro l’inno concorde:

O voi che il sangue opprime, Uomini, su le cime

splende l’Alba sublime!

Il sogno d’un passato lontano, d’una ignota

stirpe, d’una remota

favola nei Poeti luce.

Ai Poeti oscuro è il sogno del futuro.

Qual contro l’aure avverse una chioma divina,

una fiamma divina, tal ne la vita splende

l’Anima, si distende, in dietro effusa pende.

Ospiti fummo (O tu che m’ami: ti sovviene?

Era ne le tue vene

il Ritmo), ospiti fummo in imperi di gloria.

Nativa è la memoria

in noi, dei fiori ardenti su dai cavi alabastri

come tangibili astri,

dei misteri veduti,

degli amori goduti,

degli aromi bevuti.

In qual sera purpurea chiudemmo gli occhi? Quale

fu ne l’ora mortale

il nostro dio? Da quale portentosa ferita

esalammo la vita?

Forse dopo una strage di eroi? Sotto il profondo

ciel d’un letto profondo?

Le nostre spoglie fiera

custodì la Chimera

ne la purpurea sera.

E al risveglio improvviso dal sonno secolare

noi vedemmo raggiare

un altro cielo; udimmo altre voci, altri canti;

udimmo tutti i pianti

umani, tutti i pianti umani che la Terra

nel suo cerchio rinserra.

Udimmo tutti i vani

gemiti e gli urli insani

e le bestemmie immani.

Udimmo taciturni la querela confusa.

Ma ne l’anima chiusa

l’antichissimo sogno, che fluttuava ancòra,

ebbe una nuova aurora.

E vivemmo; e ingannammo la vita ricordando

quella morte, cantando

dei misteri veduti,

degli amori goduti,

degli aromi bevuti.

Or conviene il silenzio: alto silenzio. Oscuro

è il sogno del futuro.

Nuova morte ci attende. Ma in qual giorno supremo,

o Fato, rivivremo?

Quando i Poeti al mondo canteranno su corde

d’oro l’inno concorde:

O voi che il sangue opprime,

Uomini, su le cime splende l’Alba sublime!

.jpg)

Gabriele D’Annunzio poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, D'Annunzio, Gabriele

.jpg)

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

Post-Mortem Poetry

In Philadelphia they have a custom which it would be pleasant to see adopted throughout the land. It is that of appending to published death-notices a little verse or two of comforting poetry. Any one who is in the habit of reading the daily Philadelphia Ledger, must frequently be touched by these plaintive tributes to extinguished worth. In Philadelphia, the departure of a child is a circumstance which is not more surely followed by a burial than by the accustomed solacing poesy in the Public Ledger. In that city death loses half its terror because the knowledge of its presence comes thus disguised in the sweet drapery of verse. For instance, in a late Ledger I find the following (I change the surname):

“Died

“Hawks.—On the 17th inst., Clara, the daughter of Ephraim and Laura Hawks, aged 21 months and 2 days.

“That merry shout no more I hear,

No laughing child I see,

No little arms are round my neck,

No feet upon my knee;

No kisses drop upon my cheek,

These lips are sealed to me.

Dear Lord, how could I give Clara up

To any but to Thee?”

A child thus mourned could not die wholly discontended. From the Ledger of the same date I make the following extract, merely changing the surname, as before:

“Becket.—On Sunday morning, 19th inst., John P., infant son of George and Julia Becket, aged 1 year, 6 months, and 15 days.

“That merry shout no more I hear,

No laughing child I see,

No little arms are round my neck,

No feet upon my knee;

No kisses drop upon my cheek,

These lips are sealed to me.

Dear Lord, how could I give Johnnie up

To any but to Thee?”

The similarity of the emotions as produced in the mourners in these two instances is remarkably evidenced by the singular similarity of thought which they experienced, and the surprising coincidence of language used by them to give it expression.

In the same journal, of the same date, I find the following (surname suppressed, as before):

“Wagner.—On the 10th inst., Ferguson G., the son of William L. and Martha Theresa Wagner, aged 4 weeks and 1 day.

“That merry shout no more I hear,

No laughing child I see,

No little arms are round my neck,

No feet upon my knee;

No kisses drop upon my cheek,

These lips are sealed to me.

Dear Lord, how could I give Ferguson up

To any but to Thee?”

It is strange what power the reiteration of an essentially poetical thought has upon one’s feelings. When we take up theLedger and read the poetry about little Clara, we feel an unaccountable depression of the spirits. When we drift further down the column and read the poetry about little Johnnie, the depression of spirits acquires an added emphasis, and we experience tangible suffering. When we saunter along down the column further still and read the poetry about little Ferguson, the word torture but vaguely suggests the anguish that rends us.

In the Ledger (same copy referred to above) I find the following (I alter surname, as usual):

“Welch.—On the 5th inst., Mary C. Welch, wife of William B. Welch, and daughter of Catharine and George W. Markland, in the 29th year of her age.

“A mother dear, a mother kind,

Has gone and left us all behind.

Cease to weep, for tears are vain,

Mother dear is out of pain.

“Farewell, husband, children dear,

Serve thy God with filial fear,

And meet me in the land above,

Where all is peace, and joy, and love.”

What could be sweeter than that? No collection of salient facts (without reduction to tabular form) could be more succinctly stated than is done in the first stanza by the surviving relatives, and no more concise and comprehensive programme of farewells, post-mortuary general orders, etc., could be framed in any form than is done in verse by deceased in the last stanza. These things insensibly make us wiser and tenderer, and better. Another extract:

“Ball.—On the morning of the 15th inst, Mary E., daughter of John and Sarah F. Ball.

“’Tis sweet to rest in lively hope

That when my change shall come

Angels will hover round my bed,

To waft my spirit home.”

The following is apparently the customary form for heads of families:

“Burns.—On the 20th inst., Michael Burns, aged 40 years.

“Dearest father, thou hast left us,

Here thy loss we deeply feel;

But ’tis God that has bereft us,

He can all our sorrows heal.

“Funeral at 2 o’clock sharp.”

There is something very simple and pleasant about the following, which, in Philadelphia, seems to be the usual form for consumptives of long standing. (It deplores four distinct cases in the single copy of the Ledger which lies on the Memoranda editorial table):

“Bromley.—On the 29th inst., of consumption, Philip Bromley, in the 50th year of his age.

“Affliction sore long time he bore,

Physicians were in vain—

Till God at last did hear him mourn,

And eased him of his pain.

“The friend whom death from us has torn,

We did not think so soon to part;

An anxious care now sinks the thorn

Still deeper in our bleeding heart.”

This beautiful creation loses nothing by repetition. On the contrary, the oftener one sees it in the Ledger, the more grand and awe-inspiring it seems.

With one more extract I will close:

“Doble.—On the 4th inst., Samuel Peveril Worthington Doble, aged 4 days.

“Our little Sammy’s gone,

His tiny spirit’s fled;

Our little boy we loved so dear

Lies sleeping with the dead.

“A tear within a father’s eye,

A mother’s aching heart,

Can only tell the agony

How hard it is to part.”

Could anything be more plaintive than that, without requiring further concessions of grammar? Could anything be likely to do more towards reconciling deceased to circumstances, and making him willing to go? Perhaps not. The power of song can hardly be estimated. There is an element about some poetry which is able to make even physical suffering and death cheerful things to contemplate and consummations to be desired. This element is present in the mortuary poetry of Philadelphia degree of development.

The custom I have been treating of is one that should be adopted in all the cities of the land.

It is said that once a man of small consequence died, and the Rev. T. K. Beecher was asked to preach the funeral sermon—a man who abhors the lauding of people, either dead or alive, except in dignified and simple language, and then only for merits which they actually possessed or possess, not merits which they merely ought to have possessed. The friends of the deceased got up a stately funeral. They must have had misgivings that the corpse might not be praised strongly enough, for they prepared some manuscript headings and notes in which nothing was left unsaid on that subject that a fervid imagination and an unabridged dictionary could compile, and these they handed handed to the minister as he entered the pulpit. They were merely intended as suggestions, and so the friends were filled with consternation when the minister stood up in the pulpit and proceeded to read off the curious odds and ends in ghastly detail and in a loud voice! And their consternation solidified to petrification when he paused at the end, contemplated the multitude reflectively, and then said, impressively:

“The man would be a fool who tried to add anything to that. Let us pray!”

And with the same strict adhesion to truth it can be said that the man would be a fool who tried to add anything to the following transcendent obituary poem. There is something so innocent, so guileless, so complacent, so unearthly serene and self-satisfied about this peerless “hogwash,” that the man must be made of stone who can read it without a dulcet ecstasy creeping along his backbone and quivering in his marrow. There is no need to say that this poem is genuine and in earnest, for its proofs are written all over its face. An ingenious scribbler might imitate it after a fashion, but Shakespeare himself could not counterfeit it. It is noticeable that the country editor who published it did not know that it was a treasure and the most perfect thing of its kind that the storehouses and museums of literature could show. He did not dare to say no to the dread poet—for such a poet must have been something of an apparition—but he just shovelled it into his paper anywhere that came handy, and felt ashamed, and put that disgusted “Published by Request” over it, and hoped that his subscribers would overlook it or not feel an impulse to read it:

“(Published by request)

“Lines

‘Composed on the death of Samuel and Catharine Belknap’s children

“By M. A. Glaze

“Friends and neighbors all draw near,

And listen to what I have to say;

And never leave your children dear

When they are small, and go away.

“But always think of that sad fate,

That happened in year of ’63;

Four children with a house did burn,

Think of their awful agony.

“Their mother she had gone away,

And left them there alone to stay;

The house took fire and down did burn,

Before their mother did return.

“Their piteous cry the neighbors heard,

And then the cry of fire was given;

But, ah! before they could them reach,

Their little spirits had flown to heaven.

“Their father he to war had gone,

And on the battle-field was slain;

But little did he think when he went away,

But what on earth they would meet again.

“The neighbors often told his wife

Not to leave his children there,

Unless she got someone to stay,

And of the little ones take care.

“The oldest he was years not six,

And the youngest only eleven months old,

But often she had left them there alone,

As, by the neighbors, I have been told.

“How can she bear to see the place.

Where she so oft has left them there,

Without a single one to look to them,

Or of the little ones to take good care.

“Oh, can she look upon the spot,

Whereunder their little burnt bones lay,

But what she thinks she hears them say,

‘’Twas God had pity, and took us on high.’

“And there may she kneel down and pray,

And ask God her to forgive;

And she may lead a different life

While she on earth remains to live.

“Her husband and her children too,

God has took from pain and woe.

May she reform and mend her ways,

That she may also to them go.

“And when it is God’s holy will,

O, may she be prepared

To meet her God and friends in peace,

And leave this world of care.”

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Galerie des Morts, Twain, Mark

Nieuw gevelgedicht in Hulten (Gemeente Gilze-Rijen)

s t e e n

van Erik van Os (1963)

Plaats: Basisschool Gerardus Majella

Gerardus Majellastraat 17, Hulten

steen

Reizend door mijn rugzak

vond ik tussen restjes reis

die steen die

zo mooi voelde

toen ik hem vond

die ik meenam

omdat ik wist

eenmaal thuis

onder in mijn rugzak

die steen vinden

dat moet iets moois zijn.

Erik van Os

Gevelgedichten’ is een project van Hanneke van Kempen, Louis Chamuleau

en Jan de Jong namens de kunstcommissie Gilze en Rijen

flersdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Hanneke van Kempen, Street Art, Urban Art

![]()

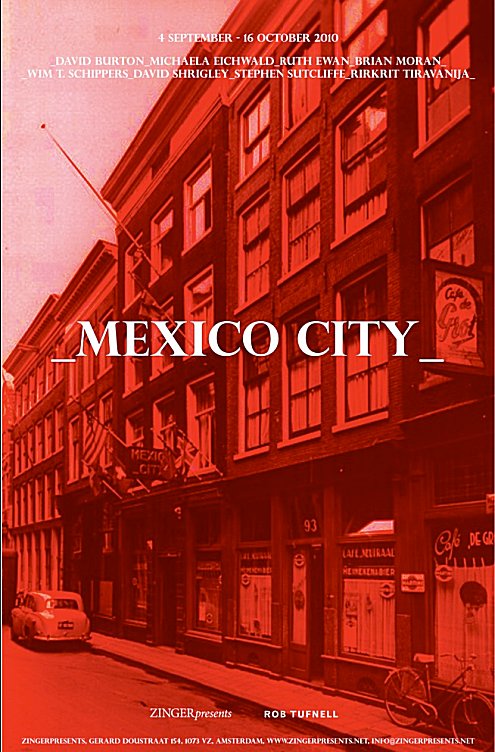

Galerie ZINGERpresents Amsterdam

Mexico City

David Burton, Michaela Eichwald, Ruth Ewan, Brian Moran, Wim T. Schippers,

David Shrigley, Stephen Sutcliffe, Rirkrit Tiravanija

Curated by Rob Tufnell

4 September – 16 October 2010

De titel van de tentoonstelling Mexico City is ontleend aan de naam van de bar die ooit was gevestigd aan de Warmoesstraat 91 te Amsterdam en de setting was voor Albert Camus‘ beroemde boek La Chute (De val) uit 1956. Mexico City is een tentoonstelling over de vervallen lach, lege beloftes, ongebalanceerde ondergrond en iconoclasme. De werken in de tentoonstelling beroeren de centrale thema’s van het Camus’ boek rondom mislukking en hypocrisie door hun gebruik van oppervlakkig simplistische vormen die gelezen kunnen worden als het product van zowel radeloosheid als overdaad.

De tentoonstelling bevat een werk op papier van de autodidacte straatkunstenaar David Burton (b. 1944). Ook wordt voor de tentoonstelling de legendarische pindakaasvloer van Wim T. Schippers uit 1962 in een nieuwe configuratie getoond. Verder wordt Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Black Bicycles uit 1995 geïnstalleerd, een werk waarin fietsen met een duister verleden een bloeiende schaduweconomie blootleggen. Naast deze historische werken zullen Michaela Eichwald, Ruth Ewan, Brian Moran and David Shrigley nieuw werk presenteren.

Camus’ La Chute omvat grotendeels een monoloog, uitgesproken in de Amsterdamse rosse buurt gelegen bar Mexico City, een gebied waar .de concentrische kanalen zich verhouden tot de cirkels van de hel… een middenklasse hel, uiteraard, bevolkt met duistere dromen.

Wanneer men geleidelijk van buiten de cirkels penetreert, het leven – en sterker haar misdrijven – wordt beklemmender en duisterder. En hier komen we aan in de laatste cirkel.’ Het is hier dat onze protagonist zijn keuze maakt om zichzelf onder te dompelen onder

zeeniveau in een zelfopgelegde afgrond waar niemand hypocriet is in zijn genoegens.

Rob Tufnell, 2010 (vertaling S.v.G/L.v.d.E)

Galerie ZINGERpresents, Gerard Doustraat 154, 1073VZ Amsterdam The Netherlands

+31 6 2493 9047

info@zingerpresents.net

►website zingerpresents

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News

.jpg)

Ed Schilders

Pietro Aretino

De geschiedenis van een reputatie

Drie

De geschiedenis wordt gecompliceerd door het bestaan van een suite afbeeldingen waarvan een zekere Count Frédéric de Waldeck (1766-1875!) beweerde dat hij ze had teruggevonden in een klooster (!) in Mexico City. Foxon vergeleek ze, voor zover mogelijk, met het Toscanini-exemplaar, en hoewel er verschillen zijn in details corresponderen er tien precies met elkaar. Waldeck vond echter 20 prenten (over het aantal hieronder meer) en juist via die tien overige kon Foxon vaststellen dat Waldeck hier en daar geïmproviseerd moet hebben: ‘Waldecks twaalfde plaat komt overeen met houtgravure nr. 9 in Toscanini’s exemplaar, maar alleen in zoverre ze met elkaar verbonden kunnen worden door een fragment in het British Museum . . .’ Voor de entourage bedacht Waldeck zelf a completely different scene. Daaruit volgt dat Waldeck hooguit tien vroege prenten onder ogen kan hebben gehad maar ook dit zijn waarschijnlijk latere kopieën geweest. De meeste naslagwerken en overzichten beelden deze Waldeck-prenten af (zie bij voorbeeld Mimus Eroticus van A. M. Rabenalt, Hamburg, 1965, twee delen, en Erotische Kunst in Europa, D. M. Klinger, Nùrnberg 1982, deel I; het laatste werk heeft ook een reproduktie van twee bladen uit de Toscanini-bundel, inclusief de tekst van de sonnetten).

Tenslotte moet in dit verband vermeld worden dat in 1904 in Parijs een van de allermooiste uitgaven van de sonnetten verscheen ter nagedachtenis aan de legendarische uitgever en bibliofiel Isidore Liseux, een ex-jezuïet, inclusief diens al genoemde naspeuringen. Het bijzondere van deze uitgave is niet alleen dat zowel de Italiaanse als de Franse tekst gegeven worden, of dat alle modier in drie staten in zijn opgenomen, maar dat de eerste staat een reproduktie zou zijn van schetsen die zorgvuldig naar de originelen van Giulio Romano gemaakt zouden zijn. De schetsen wijken echter zozeer van alle bekende andere prenten af dat dit zeer onwaarschijnlijk is. (3) Niettemin is Liseux’ verhaal interessant genoeg om hier kort herhaald te worden.

De originelen, schrijft Liseux, ‘blijven tot nu toe definitief onvindbaar’, maar de schetsen die hij hier voor het eerst prijs geeft aan de openbaarheid zijn ‘direct genomen van een origineel exemplaar van het standenboek door een kunstenaar die het geluk had deze composities te bestuderen en het vernuft er een duurzaam souvenir van te bewaren.’

Liseux vond de schetsen ‘gedurende een vakantiereis door de Gers’. ‘Wij hadden het wonderlijke genoegen bij een bescheiden verzamelaar de serie van zestien tekeningen te ontmoeten, getraceerd op bladen van gevergeerd papier.’ Deze traceringen zijn, zegt Liseux, weliswaar niet ouder dan 1779, maar ongetwijfeld diende dat bijzondere, originele exemplaar als ondergrond. Helaas kan dat laatste feit niet aannemelijk gemaakt worden. Wat niet wegneemt dat deze suite veel mooier is dan al het voorgaande dat ouder en daarom iets origineler is.

Waldeck, Sander en Toscanini, Liseux. Voeg daarbij de suites waarvan bekend is dat ze van later datum zijn en het ontbreken van de originelen is enerzijds een moeilijk te verteren zaak geweest, anderzijds een enthousiast ingevulde witte vlek in de geschiedenis van het erotische boek.

Het verdwijnen van de originelen is een gegeven dat zich gemakkelijker laat verklaren dan de schijnbewegingen van Waldeck en Liseux. Aretino’s gitzwarte reputatie (onder puriteinen) zal er ongetwijfeld toe hebben bijgedragen dat van de eerste en volgende oplages weinig is overgebleven, ook al omdat die oplages nooit erg groot geweest kunnen zijn. Er zijn berichten over zeer succesvolle verkopen (onder andere bij Casanova) maar om meer dan enige tientallen exemplaren per jaar gaat het dan nog steeds niet.

Daarnaast treffen we in de achtergrondliteratuur voortdurend gevallen van censuur of vernietiging aan. Misschien verantwoorden die het uitsterven van de editto princeps niet, ze zijn niettemin illustratief voor de gestrengheid waarmee sommigen de modi te lijf gingen.

‘De laatste set waarvan bericht vastligt,’ schrijft Foxon, en hij heeft het over de editie van 1527, ‘en het lot ervan wordt beschreven in Nollekens and His Times (1829).’ Deze Nollekens werd door zijn biechtvader betrapt toen hij op een mooie dag (neem ik aan) zijn Aretino bekeek. De geestelijke weigerde Nollekens de absolutie te geven als hij de set niet on-middellijk in de open haard wierp. En Nollekens deed dat. Hij schijnt er een trauma aan te hebben overgehouden: ‘Zo nu en dan zag men hem in tranen,’ schrijft zijn biograaf T. S. Smith, ‘wegens wat hij zijn follynoemde.’

Het waren niet alleen paters en prelaten. Liseux citeert uit Chevilliers Origine de l’Imprimerie(1694) waarin sprake is van een Parijse graveur die een set kocht voor ‘een aanzienlijke som gelds’, uitsluitend met het doel er de brand in te steken. ‘Hij heeft steeds gedacht,’ en het lijkt alsof zulke daden altijd, al is het maar sous-entendu, een emotionele plot moeten hebben, ‘dat het de originele platen waren, gegraveerd door Marcantonio, en dat hij ze had vernietigd.’ Maar dat waren ze dus niet.

In januari 1674 of 1675 werd, volgens Ashbee (Catena), een poging tot herdruk en compensatie van de schaarste ondernomen op de pers van de universiteit van Oxford. Op het laatste moment werden de studenten tijdens hun clandestiene werkzaamheden betrapt door de eigenaar van de drukkerij. Of er toch nog exemplaren in omloop zijn gekomen kon Ashbee al niet meer met zekerheid vaststellen. Zijn bron, Humphrey Prideaux, bericht dat er zestig stuks bad gon abroad before the business was discovered,maar Ashbee zelf meent dat ‘waarschijnlijk geen enkele set momenteel nog bestaat.’

Het Bilder Lexikon meldt tenslotte een geval van literaire autoda-fe uit 1556 en dat derhalve echt een van de vroegste uitgaven moet hebben betroffen. Het ging om het exemplaar van de Dresdener Bibliothek.

(wordt vervolgd)

Ed Schilders: Pietro Aretino. De geschiedenis van een reputatie (3)

.jpg)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Aretino, Pietro, Ed Schilders, Erotic literature

P.C. Boutens

(1870-1943)

In eenzaamheid

Weêr ontvangt mij vroeger einder:

Al het schoon van aarde en hemel

Vloeit ineen tot de oude lijn der

Diepe zee wier lichtgewemel

Mijner oogen jonkheid boeide

Vóor haar vloed om u vervloeide.

O als welk een ander kind,

Armer wel en zeker droever,

Zat ik aan denzelfden oever

Eer mijn ziel u had bemind!

Hoe verdiept de duizend glansen

Over de’ eigen spiegel dansen!

Al de brandend witte rozen,

Aller vooglen hoogste wijzen,

Sneeuwen wolken en de hoozen

Blanke sterren die er rijzen,

Al de stralende oogenlichten

In der menschen aangezichten:

Al de brekers op de wijde

Zee die uitvloeit aan mijn voeten,

Zijn de onafgebroken stoeten

Van het zegerijk geleide

Waarvan de ommegang niet eindt

Tot uw glans hem overschijnt.

P.C. Boutens gedicht

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Boutens, P.C.

George Eliot

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

Count That Day Lost

If you sit down at set of sun

And count the acts that you have done,

And, counting, find

One self-denying deed, one word

That eased the heart of him who heard,

One glance most kind

That fell like sunshine where it went –

Then you may count that day well spent.

But if, through all the livelong day,

You’ve cheered no heart, by yea or nay –

If, through it all

You’ve nothing done that you can trace

That brought the sunshine to one face–

No act most small

That helped some soul and nothing cost –

Then count that day as worse than lost.

.jpg)

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George

A case of identity:

Doris

jef van kempen 2010

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Photography

Ton van Reen

Lopen

Een man vult zijn kalebas met water

op blote voeten gaat hij op weg

het is vroeg in de donkere ochtend

hij is de enige man onder de verblekende sterren

de hele ochtend loopt hij door, altijd rechtdoor

spaarzaam drinkt hij water

rond de middag komt hij bij een kruispunt

hij neemt de afslag naar rechts

de zon is heet, maar zijn voeten willen niet rusten

hij loopt door, ook al brandt de weg onder hem

de hele middag loopt hij door, altijd rechtdoor

spaarzaam drinkt hij water

vroeg in de avond nadert hij een kruispunt

hij neemt de afslag naar rechts

de hele avond loopt hij door, altijd rechtdoor

hij ziet de sterren aan de hemel verschijnen

spaarzaam drinkt hij water

tegen middernacht komt hij bij een kruispunt

hij neemt de afslag naar rechts

de hele nacht loopt hij door, altijd rechtdoor

spaarzaam drinkt hij water

hij is de enige man onder de maan

eindeloos telt hij de flonkerende sterren

tot ze verbleken aan de hemel

vroeg in de ochtend bereikt hij zijn huis

hij is dankbaar dat hij een huis heeft

een huis om thuis te kunnen komen

tevreden dept hij zijn brandende voeten

met het laatste restje water

hij is zijn voeten dankbaar

hij buigt diep en droogt ze met eerbied af

hij weet dat hij een man met voeten is

een man die kan lopen

Ton van Reen poetry: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -De naam van het mes, Ton van Reen

![]()

Lola Ridge

(1873-1941)

Broadway

Light!

Innumerable ions of light,

Kindling, irradiating,

All to their foci tending…

Light that jingles like anklet chains

On bevies of little lithe twinkling feet,

Or clingles in myriad vibrations

Like trillions of porcelain

Vases shattering…

Light over the laminae of roofs,

Diffusing in shimmering nebulae

About the night’s boundaries,

Or billowing in pearly foam

Submerging the low-lying stars…

Light for the feast prolonged –

Captive light in the goblets quivering…

Sparks evanescent

Struck of meeting looks –

Fringed eyelids leashing

Sheathed and leaping lights…

Infinite bubbles of light

Bursting, reforming…

Silvery filings of light

Incessantly falling…

Scintillant, sided dust of light

Out of the white flares of Broadway –

Like a great spurious diamond

In the night’s corsage faceted…

Broadway,

In ambuscades of light,

Drawing the charmed multitudes

With the slow suction of her breath –

Dangling her naked soul

Behind the blinding gold of eunuch lights

That wind about her like a bodyguard.

Or like a huge serpent, iridescent-scaled,

Trailing her coruscating length

Over the night prostrate –

Triumphant poised,

Her hydra heads above the avenues,

Values appraising

And her avid eyes

Glistening with eternal watchfulness…

Broadway –

Out of her towers rampant,

Like an unsubtle courtezan

Reserving nought for some adventurous night.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Ridge, Lola

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

45

The other two, slight air, and purging fire,

Are both with thee, wherever I abide,

The first my thought, the other my desire,

These present-absent with swift motion slide.

For when these quicker elements are gone

In tender embassy of love to thee,

My life being made of four, with two alone,

Sinks down to death, oppressed with melancholy.

Until life’s composition be recured,

By those swift messengers returned from thee,

Who even but now come back again assured,

Of thy fair health, recounting it to me.

This told, I joy, but then no longer glad,

I send them back again and straight grow sad.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature