Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Het even verguisde als bewierookte enfant terrible van de Franse letteren: Michel Houellebecq treedt zaterdag 16 mei op tijdens City2Cities 2015! Met zijn vertaler Martin de Haan spreekt Houellebecq over zijn nieuwe boek Onderworpen (Soumission) waarin een moslim in 2022 president wordt van Frankrijk. Het boek veroorzaakte al voor verschijnen ophef, die alleen nog maar werd aangewakkerd door de aanslag op Charlie Hebdo in Parijs.

Het even verguisde als bewierookte enfant terrible van de Franse letteren: Michel Houellebecq treedt zaterdag 16 mei op tijdens City2Cities 2015! Met zijn vertaler Martin de Haan spreekt Houellebecq over zijn nieuwe boek Onderworpen (Soumission) waarin een moslim in 2022 president wordt van Frankrijk. Het boek veroorzaakte al voor verschijnen ophef, die alleen nog maar werd aangewakkerd door de aanslag op Charlie Hebdo in Parijs.

Michel Houellebecq debuteerde begin jaren negentig als dichter, maar brak in 1998 door met de roman Elementaire deeltjes. Met dat boek en later nogmaals met Mogelijkheid van een eiland greep hij net naast de belangrijkste Franse literatuurprijs. In 2010 ontving hij de Prix Goncourt wel, voor De kaart en het gebied. In 2011 ‘verdween’ Houellebecq vlak voor een promotietournee door Nederland en België. Bijna een week later dook hij weer op, met als excuus dat hij de tour vergeten was. Nooit werd helemaal duidelijk wat de werkelijke reden was om niets van zich te laten horen. Begin dit jaar ging de film The kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq in première. In deze komische nep-documentaire wordt uit de doeken gedaan waarom hij destijds zo onverwacht verdween.

Onderworpen (De Arbeiderspers), de zesde roman van Michel Houellebecq, speelt zich af in het Frankrijk van 2022. Bij de presidentverkiezingen kiest het land voor het eerst in de geschiedenis voor een islamitische president. Om het Front National van een verkiezingsoverwinning af te houden, steunen de linkse en rechtse partijen de populaire en charismatische Mohammed Ben Abbes. Op die manier krijgt Frankrijk een moslimpresident, ondanks dat nog altijd een grote meerderheid van de bevolking niet islamitisch is. De bevolking gaat al snel wat merken van de macht van de moslims: vrouwen moeten hoofddoekjes dragen en minirokjes verdwijnen uit het straatbeeld. De hoofdpersoon in de roman, de 44-jarige universitair docent Francois, ziet zijn land steeds verder polariseren.

Onderworpen (De Arbeiderspers), de zesde roman van Michel Houellebecq, speelt zich af in het Frankrijk van 2022. Bij de presidentverkiezingen kiest het land voor het eerst in de geschiedenis voor een islamitische president. Om het Front National van een verkiezingsoverwinning af te houden, steunen de linkse en rechtse partijen de populaire en charismatische Mohammed Ben Abbes. Op die manier krijgt Frankrijk een moslimpresident, ondanks dat nog altijd een grote meerderheid van de bevolking niet islamitisch is. De bevolking gaat al snel wat merken van de macht van de moslims: vrouwen moeten hoofddoekjes dragen en minirokjes verdwijnen uit het straatbeeld. De hoofdpersoon in de roman, de 44-jarige universitair docent Francois, ziet zijn land steeds verder polariseren.

Over Michel Houellebecq: Michel Houellebecq (1958) is Frankrijks onbetwiste sterschrijver van dit moment. Hij publiceerde essays en poëzie voordat hij zich in 1994 met de roman De wereld als markt en strijd opwierp als belofte van de Franse letteren. Die status bevestigde hij met Elementaire deeltjes , dat hem terecht de faam van groot schrijver bezorgde, en Platform. In 2011 verscheen zijn grote nieuwe roman De kaart en het gebied. Zijn veelvuldig bekroonde en wereldwijd vertaalde werk is naar het Nederlands vertaald door Martin de Haan.

Over Martin de Haan: Martin de Haan (Middelburg, 1966) werkte na zijn studies Frans en literatuurwetenschap enkele jaren aan een proefschrift over de poëzie van Raymond Queneau, maar zei in 1995 de wetenschap vaarwel om zelf literair actief te worden. Hij was lange tijd recensent Franse literatuur voor de Volkskrant en schreef essays voor diverse Nederlandse en Vlaamse tijdschriften. Martin de Haan is de vaste vertaler van o.a. Milan Kundera en Michel Houellebecq.

City2Cities 2015 – Met Michel Houellebecq, Michel Faber e.v.a. op 15 & 16 mei 2015

City2Cities 2015 – Met Michel Houellebecq, Michel Faber e.v.a. op 15 & 16 mei 2015

Twee avonden vult het Postkantoor Neude zich met internationale literatuur. Onder de bogen van de indrukwekkende hal – waar men vroeger in de rij stond voor postzegels en briefkaarten – klinkt twee dagen proza, poëzie en muziek. Net als voorgaande jaren gaat ook deze editie bijzondere aandacht uit naar de literatuur uit twee wereldsteden. Dit jaar zijn dat Krakau en Parijs.

City2Cities 2015 – Vrijdagavond 15 mei – Met Eleanor Catton, Jens Christian Grøndahl e.v.a. – Postkantoor Neude, Utrecht, programma:

– Eleanor Catton over haar met de Man Booker Prize bekroonde roman Al wat schittert.

– De grote Deense schrijver Jens Christian Grøndahl (Portret van een man) in gesprek met de Nederlandse romancier Stephan Enter.

– Marie Darrieussecq (Zeugzoenen & Je moet veel van mannen houden), een van de origineelste en opmerkelijkste Franse schrijvers, in gesprek met Niña Weijers.

– Olga Tokarczuk (De rustelozen), een van de meest bejubelde én best verkopende Poolse schrijvers van dit moment, in gesprek met de Vlaamse Annelies Verbeke, schrijver van o.a. Slaap! en Dertig dagen.

– Karol Lesman en Olga Tokarczuk over dé Poolse literaire klassieker: De pop (1890) van Bolesław Prus.

– Jo Govaerts, Sławomir Shuty en anderen over literair Krakau.

– Alle genomineerden voor de C.C.S. Crone Stipendia 2015.

Met zaterdag 16 mei 19:30 – Postkantoor Neude, Utrecht, op het programma:

– MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ in gesprek met zijn vertaler Martin de Haan over Onderworpen (Soumission).

– MICHEL FABER over zijn nieuwste en laatste roman Het boek van wonderlijke nieuwe dingen.

– JAN SIEBELINK over Parijs

– Rokus Hofstede & Martin de Haan over MARCEL PROUST

– Alle genomineerden voor de FILTER VERTAALPRIJS.

– Writer in Residence THOMAS CLERC

– ŁUKASZ KOTERBA en VROUWKJE TUINMAN over het Polenhotel

– RUBEN VAN GOGH over zijn Parijse roots

# Meer informatie website City2Cities

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Michel Houellebecq, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE

Hans Hermans © photos: History of Britain

(Exmoor National Park, near Woody Bay 2014)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, History of Britain, Photography

Speciaal themanummer Literair tijdschrift Extaze tijdens het Kellendonk-jaar 2015

Speciaal themanummer Literair tijdschrift Extaze tijdens het Kellendonk-jaar 2015

Ook dit jaar maakt Literair Tijdschrift Extaze weer een bijzonder themanummer. Vijfentwintig jaar geleden is de Nederlandse schrijver Frans Kellendonk overleden, voor Extaze reden om een apart nummer over zijn leven en schrijverschap te plannen. Begin april is een crowdfundingactie gestart via website: www.voordekunst.nl

Het Kellendonk-nummer, zoals dat de redactie van Extaze voor ogen staat, kan niet met de eigen bescheiden middelen gefinancierd worden. De kosten voor het onderzoek, de uitwerking van de stukken, het beeldend werk (waarvoor een gerichte opdracht is gegeven aan Rens Krikhaar, een beeldend kunstenaar te Den Haag wiens stijl verwantschap toont met het werk van Kellendonk), de speciale vormgeving, net als het beeldend werk aangepast aan het onderwerp, de extra drukkosten die de bijzondere vormgeving en het extra aantal pagina’s met zich meebrengen en de ‘anders dan andere’ presentatie, waarvoor sprekers en podiumartiesten gerichte opdrachten krijgen, noodzaken de redactie een beroep op u te doen.

# Meer informatie over Frans Kellendonk op website Kellendonk-fonds

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Frans Kellendonk, LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING

Dada Manifesto by Hugo Ball (1886–1927)

Dada Manifesto by Hugo Ball (1886–1927)

Read at the first public by Dada soirée, Zurich, July 14, 1916.

Dada is a new tendency in art. One can tell this from the fact that until now nobody knew anything about it, and tomorrow everyone in Zurich will be talking about it. Dada comes from the dictionary. It is terribly simple. In French it means “hobby horse”. In German it means “good-bye”, “Get off my back”, “Be seeing you sometime”. In Romanian: “Yes, indeed, you are right, that’s it. But of course, yes, definitely, right”. And so forth.

An International word. Just a word, and the word a movement. Very easy to understand. Quite terribly simple. To make of it an artistic tendency must mean that one is anticipating complications. Dada psychology, dada Germany cum indigestion and fog paroxysm, dada literature, dada bourgeoisie, and yourselves, honoured poets, who are always writing with words but never writing the word itself, who are always writing around the actual point. Dada world war without end, dada revolution without beginning, dada, you friends and also-poets, esteemed sirs, manufacturers, and evangelists. Dada Tzara, dada Huelsenbeck, dada m’dada, dada m’dada dada mhm, dada dera dada, dada Hue, dada Tza.

How does one achieve eternal bliss? By saying dada. How does one become famous? By saying dada. With a noble gesture and delicate propriety. Till one goes crazy. Till one loses consciousness. How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated? By saying dada. Dada is the world soul, dada is the pawnshop. Dada is the world’s best lily-milk soap. Dada Mr Rubiner, dada Mr Korrodi. Dada Mr Anastasius Lilienstein. In plain language: the hospitality of the Swiss is something to be profoundly appreciated. And in questions of aesthetics the key is quality.

I shall be reading poems that are meant to dispense with conventional language, no less, and to have done with it. Dada Johann Fuchsgang Goethe. Dada Stendhal. Dada Dalai Lama, Buddha, Bible, and Nietzsche. Dada m’dada. Dada mhm dada da. It’s a question of connections, and of loosening them up a bit to start with. I don’t want words that other people have invented. All the words are other people’s inventions. I want my own stuff, my own rhythm, and vowels and consonants too, matching the rhythm and all my own. If this pulsation is seven yards long, I want words for it that are seven yards long. Mr Schulz’s words are only two and a half centimetres long.

It will serve to show how articulated language comes into being. I let the vowels fool around. I let the vowels quite simply occur, as a cat meows . . . Words emerge, shoulders of words, legs, arms, hands of words. Au, oi, uh. One shouldn’t let too many words out. A line of poetry is a chance to get rid of all the filth that clings to this accursed language, as if put there by stockbrokers’ hands, hands worn smooth by coins. I want the word where it ends and begins. Dada is the heart of words.

Each thing has its word, but the word has become a thing by itself. Why shouldn’t I find it? Why can’t a tree be called Pluplusch, and Pluplubasch when it has been raining? The word, the word, the word outside your domain, your stuffiness, this laughable impotence, your stupendous smugness, outside all the parrotry of your self-evident limitedness. The word, gentlemen, is a public concern of the first importance.

Dada Manifesto by Hugo Ball (1886–1927)

Dada soirée, Zurich, July 14, 1916.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Ball, Hugo, DADA, Dada

Jonathan Swift

(1667–1745)

On The World

With a whirl of thoughts oppress’d,

I sunk from reverie to rest.

A horrid vision seized my head,

I saw the graves give up their dead!

Jove, arm’d with terrors, bursts the skies,

And thunder roars and lightning flies!

Amazed, confused, its fate unknown,

The world stands trembling at his throne!

While each pale sinner hung his head,

Jove, nodding, shook the heavens, and said:

“Offending race of human kind,

By nature, reason, learning, blind;

You who, through frailty, stepp’d aside;

And you, who never fell from pride:

You who in different sects were shamm’d,

And come to see each other damn’d;

(So some folk told you, but they knew

No more of Jove’s designs than you;)

—The world’s mad business now is o’er,

And I resent these pranks no more.

—I to such blockheads set my wit!

I damn such fools!—Go, go, you’re bit.”

Jonathan Swift poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swift, Jonathan

Arthur Rimbaud

(1854-1891)

Chant de guerre parisien

Le Printemps est évident, car

Du cœur des Propriétés vertes,

Le vol de Thiers et de Picard

Tient ses splendeurs grandes ouvertes !

Ô Mai ! quels délirants culs-nus !

Sèvres, Meudon, Bagneux, Asnières,

Écoutez donc les bienvenus

Semer les choses printanières !

Ils ont schako, sabre et tam-tam,

Non la vieille boîte à bougies

Et des yoles qui n’ont jam, jam…

Fendent le lac aux eaux rougies !

Plus que jamais nous bambochons

Quand arrivent sur nos tanières

Crouler les jaunes cabochons

Dans des aubes particulières !

Thiers et Picard sont des Éros,

Des enleveurs d’héliotropes,

Au pétrole ils font des Corots :

Voici hannetonner leurs tropes….

Ils sont familiers du Grand Truc !..

Et couché dans les glaïeuls, Favre

Fait son cillement aqueduc,

Et ses reniflements à poivre !

La Grand’ville a le pavé chaud,

Malgré vos douches de pétrole,

Et décidément, il nous faut

Vous secouer dans votre rôle…

Et les Ruraux qui se prélassent

Dans de longs accroupissements,

Entendront des rameaux qui cassent

Parmi les rouges froissements !

Arthur Rimbaud poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Arthur Rimbaud, Rimbaud, Arthur, Rimbaud, Arthur

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal

(1829-1862)

At Last

O mother, open the window wide

And let the daylight in;

The hills grow darker to my sight

And thoughts begin to swim.

And mother dear, take my young son,

(Since I was born of thee)

And care for all his little ways

And nurse him on thy knee.

And mother, wash my pale pale hands

And then bind up my feet;

My body may no longer rest

Out of its winding sheet.

And mother dear, take a sapling twig

And green grass newly mown,

And lay them on my empty bed

That my sorrow be not known.

And mother, find three berries red

And pluck them from the stalk,

And burn them at the first cockcrow

That my spirit may not walk.

And mother dear, break a willow wand,

And if the sap be even,

Then save it for sweet Robert’s sake

And he’ ll know my sou’s in heaven.

And mother, when the big tears fall,

(And fall, God knows, they may)

Tell him I died of my great love

And my dying heart was gay.

And mother dear, when the sun has set

And the pale kirk grass waves,

Then carry me through the dim twilight

And hide me among the graves.

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal poems

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Lizzy Siddal, Siddal, Lizzy

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

2. A Society

(from: Monday or Tuesday)

This is how it all came about. Six or seven of us were sitting one day after tea. Some were gazing across the street into the windows of a milliner’s shop where the light still shone brightly upon scarlet feathers and golden slippers. Others were idly occupied in building little towers of sugar upon the edge of the tea tray.

After a time, so far as I can remember, we drew round the fire and began as usual to praise men — how strong, how noble, how brilliant, how courageous, how beautiful they were — how we envied those who by hook or by crook managed to get attached to one for life — when Poll, who had said nothing, burst into tears. Poll, I must tell you, has always been queer. For one thing her father was a strange man. He left her a fortune in his will, but on condition that she read all the books in the London Library. We comforted her as best we could; but we knew in our hearts how vain it was. For though we like her, Poll is no beauty; leaves her shoe laces untied; and must have been thinking, while we praised men, that not one of them would ever wish to marry her. At last she dried her tears. For some time we could make nothing of what she said. Strange enough it was in all conscience. She told us that, as we knew, she spent most of her time in the London Library, reading. She had begun, she said, with English literature on the top floor; and was steadily working her way down to the Times on the bottom. And now half, or perhaps only a quarter, way through a terrible thing had happened. She could read no more. Books were not what we thought them. “Books,” she cried, rising to her feet and speaking with an intensity of desolation which I shall never forget, “are for the most part unutterably bad!”

Of course we cried out that Shakespeare wrote books, and Milton and Shelley.

“Oh, yes,” she interrupted us. “You’ve been well taught, I can see. But you are not members of the London Library.” Here her sobs broke forth anew. At length, recovering a little, she opened one of the pile of books which she always carried about with her —“From a Window” or “In a Garden,” or some such name as that it was called, and it was written by a man called Benton or Henson, or something of that kind. She read the first few pages. We listened in silence. “But that’s not a book,” someone said. So she chose another. This time it was a history, but I have forgotten the writer’s name. Our trepidation increased as she went on. Not a word of it seemed to be true, and the style in which it was written was execrable.

“Poetry! Poetry!” we cried, impatiently.

“Read us poetry!” I cannot describe the desolation which fell upon us as she opened a little volume and mouthed out the verbose, sentimental foolery which it contained.

“It must have been written by a woman,” one of us urged. But no. She told us that it was written by a young man, one of the most famous poets of the day. I leave you to imagine what the shock of the discovery was. Though we all cried and begged her to read no more, she persisted and read us extracts from the Lives of the Lord Chancellors. When she had finished, Jane, the eldest and wisest of us, rose to her feet and said that she for one was not convinced.

“Why,” she asked, “if men write such rubbish as this, should our mothers have wasted their youth in bringing them into the world?”

We were all silent; and, in the silence, poor Poll could be heard sobbing out, “Why, why did my father teach me to read?”

Clorinda was the first to come to her senses. “It’s all our fault,” she said. “Every one of us knows how to read. But no one, save Poll, has ever taken the trouble to do it. I, for one, have taken it for granted that it was a woman’s duty to spend her youth in bearing children. I venerated my mother for bearing ten; still more my grandmother for bearing fifteen; it was, I confess, my own ambition to bear twenty. We have gone on all these ages supposing that men were equally industrious, and that their works were of equal merit. While we have borne the children, they, we supposed, have borne the books and the pictures. We have populated the world. They have civilized it. But now that we can read, what prevents us from judging the results? Before we bring another child into the world we must swear that we will find out what the world is like.”

So we made ourselves into a society for asking questions. One of us was to visit a man-of-war; another was to hide herself in a scholar’s study; another was to attend a meeting of business men; while all were to read books, look at pictures, go to concerts, keep our eyes open in the streets, and ask questions perpetually. We were very young. You can judge of our simplicity when I tell you that before parting that night we agreed that the objects of life were to produce good people and good books. Our questions were to be directed to finding out how far these objects were now attained by men. We vowed solemnly that we would not bear a single child until we were satisfied.

Off we went then, some to the British Museum; others to the King’s Navy; some to Oxford; others to Cambridge; we visited the Royal Academy and the Tate; heard modern music in concert rooms, went to the Law Courts, and saw new plays. No one dined out without asking her partner certain questions and carefully noting his replies. At intervals we met together and compared our observations. Oh, those were merry meeting! Never have I laughed so much as I did when Rose read her notes upon “Honour” and described how she had dressed herself as an Ethiopian Prince and gone aboard one of His Majesty’s ships. Discovering the hoax, the Captain visited her (now disguised as a private gentleman) and demanded that honour should be satisfied. “But how?” she asked. “How?” he bellowed. “With the cane of course!” Seeing that he was beside himself with rage and expecting that her last moment had come, she bent over and received, to her amazement, six light taps upon the behind. “The honour of the British Navy is avenged!” he cried, and, raising herself, she saw him with the sweat pouring down his face holding out a trembling right hand. “Away!” she exclaimed, striking an attitude and imitating the ferocity of his own expression, “My honour has still to be satisfied!” “Spoken like a gentleman!” he returned, and fell into profound thought. “If six strokes avenge the honour of the King’s Navy,” he mused, “how many avenge the honour of a private gentleman?” He said he would prefer to lay the case before his brother officers. She replied haughtily that she could not wait. He praised her sensibility. “Let me see,” he cried suddenly, “did your father keep a carriage?” “No,” she said. “Or a riding horse?” “We had a donkey,” she bethought her, “which drew the mowing machine.” At this his face lighted. “My mother’s name —” she added. “For God’s sake, man, don’t mention your mother’s name!” he shrieked, trembling like an aspen and flushing to the roots of his hair, and it was ten minutes at least before she could induce him to proceed. At length he decreed that if she gave him four strokes and a half in the small of the back at a spot indicated by himself (the half conceded, he said, in recognition of the fact that her great grandmother’s uncle was killed at Trafalgar) it was his opinion that her honour would be as good as new. This was done; they retired to a restaurant; drank two bottles of wine for which he insisted upon paying; and parted with protestations of eternal friendship.

Then we had Fanny’s account of her visit to the Law Courts. At her first visit she had come to the conclusion that the Judges were either made of wood or were impersonated by large animals resembling man who had been trained to move with extreme dignity, mumble and nod their heads. To test her theory she had liberated a handkerchief of bluebottles at the critical moment of a trial, but was unable to judge whether the creatures gave signs of humanity for the buzzing of the flies induced so sound a sleep that she only woke in time to see the prisoners led into the cells below. But from the evidence she brought we voted that it is unfair to suppose that the Judges are men.

Helen went to the Royal Academy, but when asked to deliver her report upon the pictures she began to recite from a pale blue volume, “O! for the touch of a vanished hand and the sound of a voice that is still. Home is the hunter, home from the hill. He gave his bridle reins a shake. Love is sweet, love is brief. Spring, the fair spring, is the year’s pleasant King. O! to be in England now that April’s there. Men must work and women must weep. The path of duty is the way to glory —” We could listen to no more of this gibberish.

“We want no more poetry!” we cried.

“Daughters of England!” she began, but here we pulled her down, a vase of water getting spilt over her in the scuffle.

“Thank God!” she exclaimed, shaking herself like a dog. “Now I’ll roll on the carpet and see if I can’t brush off what remains of the Union Jack. Then perhaps —” here she rolled energetically. Getting up she began to explain to us what modern pictures are like when Castalia stopped her.

“What is the average size of a picture?” she asked. “Perhaps two feet by two and a half,” she said. Castalia made notes while Helen spoke, and when she had done, and we were trying not to meet each other’s eyes, rose and said, “At your wish I spent last week at Oxbridge, disguised as a charwoman. I thus had access to the rooms of several Professors and will now attempt to give you some idea — only,” she broke off, “I can’t think how to do it. It’s all so queer. These Professors,” she went on, “live in large houses built round grass plots each in a kind of cell by himself. Yet they have every convenience and comfort. You have only to press a button or light a little lamp. Theirs papers are beautifully filed. Books abound. There are no children or animals, save half a dozen stray cats and one aged bullfinch — a cock. I remember,” she broke off, “an Aunt of mine who lived at Dulwich and kept cactuses. You reached the conservatory through the double drawing-room, and there, on the hot pipes, were dozens of them, ugly, squat, bristly little plants each in a separate pot. Once in a hundred years the Aloe flowered, so my Aunt said. But she died before that happened —” We told her to keep to the point. “Well,” she resumed, “when Professor Hobkin was out, I examined his life work, an edition of Sappho. It’s a queer looking book, six or seven inches thick, not all by Sappho. Oh, no. Most of it is a defence of Sappho’s chastity, which some German had denied, add I can assure you the passion with which these two gentlemen argued, the learning they displayed, the prodigious ingenuity with which they disputed the use of some implement which looked to me for all the world like a hairpin astounded me; especially when the door opened and Professor Hobkin himself appeared. A very nice, mild, old gentleman, but what could he know about chastity?” We misunderstood her.

“No, no,” she protested, “he’s the soul of honour I’m sure — not that he resembled Rose’s sea captain in the least. I was thinking rather of my Aunt’s cactuses. What could they know about chastity?”

Again we told her not to wander from the point — did the Oxbridge professors help to produce good people and good books? — the objects of life.

“There!” she exclaimed. “It never struck me to ask. It never occurred to me that they could possibly produce anything.”

“I believe,” said Sue, “that you made some mistake. Probably Professor Hobkin was a gynecologist. A scholar is a very different sort of man. A scholar is overflowing with humour and invention — perhaps addicted to wine, but what of that? — a delightful companion, generous, subtle, imaginative — as stands to reason. For he spends his life in company with the finest human beings that have ever existed.”

“Hum,” said Castalia. “Perhaps I’d better go back and try again.”

Some three months later it happened that I was sitting alone when Castalia entered. I don’t know what it was in the look of her that so moved me; but I could not restrain myself, and, dashing across the room, I clasped her in my arms. Not only was she very beautiful; she seemed also in the highest spirits. “How happy you look!” I exclaimed, as she sat down.

“I’ve been at Oxbridge,” she said.

“Asking questions?”

“Answering them,” she replied.

“You have not broken our vows?” I said anxiously, noticing something about her figure.

“Oh, the vow,” she said casually. “I’m going to have a baby, if that’s what you mean. You can’t imagine,” she burst out, “how exciting, how beautiful, how satisfying —”

“What is?” I asked.

“To — to — answer questions,” she replied in some confusion. Whereupon she told me the whole of her story. But in the middle of an account which interested and excited me more than anything I had ever heard, she gave the strangest cry, half whoop, half holloa —

“Chastity! Chastity! Where’s my chastity!” she cried. “Help Ho! The scent bottle!”

There was nothing in the room but a cruet containing mustard, which I was about to administer when she recovered her composure.

“You should have thought of that three months ago,” I said severely.

“True,” she replied. “There’s not much good in thinking of it now. It was unfortunate, by the way, that my mother had me called Castalia.”

“Oh, Castalia, your mother —” I was beginning when she reached for the mustard pot.

“No, no, no,” she said, shaking her head. “If you’d been a chaste woman yourself you would have screamed at the sight of me — instead of which you rushed across the room and took me in your arms. No, Cassandra. We are neither of us chaste.” So we went on talking.

Meanwhile the room was filling up, for it was the day appointed to discuss the results of our observations. Everyone, I thought, felt as I did about Castalia. They kissed her and said how glad they were to see her again. At length, when we were all assembled, Jane rose and said that it was time to begin. She began by saying that we had now asked questions for over five years, and that though the results were bound to be inconclusive — here Castalia nudged me and whispered that she was not so sure about that. Then she got up, and, interrupting Jane in the middle of a sentence, said:

“Before you say any more, I want to know — am I to stay in the room? Because,” she added, “I have to confess that I am an impure woman.”

Everyone looked at her in astonishment.

“You are going to have a baby?” asked Jane.

She nodded her head.

It was extraordinary to see the different expressions on their faces. A sort of hum went through the room, in which I could catch the words “impure,” “baby,” “Castalia,” and so on. Jane, who was herself considerably moved, put it to us:

“Shall she go? Is she impure?”

Such a roar filled the room as might have been heard in the street outside.

“No! No! No! Let her stay! Impure? Fiddlesticks!” Yet I fancied that some of the youngest, girls of nineteen or twenty, held back as if overcome with shyness. Then we all came about her and began asking questions, and at last I saw one of the youngest, who had kept in the background, approach shyly and say to her:

“What is chastity then? I mean is it good, or is it bad, or is it nothing at all?” She replied so low that I could not catch what she said.

“You know I was shocked,” said another, “for at least ten minutes.”

“In my opinion,” said Poll, who was growing crusty from always reading in the London Library, “chastity is nothing but ignorance — a most discreditable state of mind. We should admit only the unchaste to our society. I vote that Castalia shall be our President.”

This was violently disputed.

“It is as unfair to brand women with chastity as with unchastity,” said Poll. “Some of us haven’t the opportunity either. Moreover, I don’t believe Cassy herself maintains that she acted as she did from a pure love of knowledge.”

“He is only twenty-one and divinely beautiful,” said Cassy, with a ravishing gesture.

“I move,” said Helen, “that no one be allowed to talk of chastity or unchastity save those who are in love.”

“Oh, bother,” said Judith, who had been enquiring into scientific matters, “I’m not in love and I’m longing to explain my measures for dispensing with prostitutes and fertilizing virgins by Act of Parliament.”

She went on to tell us of an invention of hers to be erected at Tube stations and other public resorts, which, upon payment of a small fee, would safeguard the nation’s health, accommodate its sons, and relieve its daughters. Then she had contrived a method of preserving in sealed tubes the germs of future Lord Chancellors “or poets or painters or musicians,” she went on, “supposing, that is to say, that these breeds are not extinct, and that women still wish to bear children —”

“Of course we wish to bear children!” cried Castalia, impatiently. Jane rapped the table.

“That is the very point we are met to consider,” she said. “For five years we have been trying to find out whether we are justified in continuing the human race. Castalia has anticipated our decision. But it remains for the rest of us to make up our minds.”

Here one after another of our messengers rose and delivered their reports. The marvels of civilisation far exceeded our expectations, and, as we learnt for the first time how man flies in the air, talks across space, penetrates to the heart of an atom, and embraces the universe in his speculations, a murmur of admiration burst from our lips.

“We are proud,” we cried, “that our mothers sacrificed their youth in such a cause as this!” Castalia, who had been listening intently, looked prouder than all the rest. Then Jane reminded us that we had still much to learn, and Castalia begged us to make haste. On we went through a vast tangle of statistics. We learnt that England has a population of so many millions, and that such and such a proportion of them is constantly hungry and in prison; that the average size of a working man’s family is such, and that so great a percentage of women die from maladies incident to childbirth. Reports were read of visits to factories, shops, slums, and dockyards. Descriptions were given of the Stock Exchange, of a gigantic house of business in the City, and of a Government Office. The British Colonies were now discussed, and some account was given of our rule in India, Africa and Ireland. I was sitting by Castalia and I noticed her uneasiness.

“We shall never come to any conclusion at all at this rate,” she said. “As it appears that civilisation is so much more complex than we had any notion, would it not be better to confine ourselves to our original enquiry? We agreed that it was the object of life to produce good people and good books. All this time we have been talking of aeroplanes, factories, and money. Let us talk about men themselves and their arts, for that is the heart of the matter.”

So the diners out stepped forward with long slips of paper containing answers to their questions. These had been framed after much consideration. A good man, we had agreed, must at any rate be honest, passionate, and unworldly. But whether or not a particular man possessed those qualities could only be discovered by asking questions, often beginning at a remote distance from the centre. Is Kensington a nice place to live in? Where is your son being educated — and your daughter? Now please tell me, what do you pay for your cigars? By the way, is Sir Joseph a baronet or only a knight? Often it seemed that we learnt more from trivial questions of this kind than from more direct ones. “I accepted my peerage,” said Lord Bunkum, “because my wife wished it.” I forget how many titles were accepted for the same reason. “Working fifteen hours out of the twenty-four, as I do —” ten thousand professional men began.

“No, no, of course you can neither read nor write. But why do you work so hard?” “My dear lady, with a growing family —” “But why does your family grow?” Their wives wished that too, or perhaps it was the British Empire. But more significant than the answers were the refusals to answer. Very few would reply at all to questions about morality and religion, and such answers as were given were not serious. Questions as to the value of money and power were almost invariably brushed aside, or pressed at extreme risk to the asker. “I’m sure,” said Jill, “that if Sir Harley Tightboots hadn’t been carving the mutton when I asked him about the capitalist system he would have cut my throat. The only reason why we escaped with our lives over and over again is that men are at once so hungry and so chivalrous. They despise us too much to mind what we say.”

“Of course they despise us,” said Eleanor. “At the same time how do you account for this — I made enquiries among the artists. Now, no woman has ever been an artist, has she, Polls?”

“Jane — Austen — Charlotte — Bronte — George — Eliot,” cried Poll, like a man crying muffins in a back street.

“Damn the woman!” someone exclaimed. “What a bore she is!”

“Since Sappho there has been no female of first rate —” Eleanor began, quoting from a weekly newspaper.

“It’s now well known that Sappho was the somewhat lewd invention of Professor Hobkin,” Ruth interrupted.

“Anyhow, there is no reason to suppose that any woman ever has been able to write or ever will be able to write,” Eleanor continued. “And yet, whenever I go among authors they never cease to talk to me about their books. Masterly! I say, or Shakespeare himself! (for one must say something) and I assure you, they believe me.”

“That proves nothing,” said Jane. “They all do it. Only,” she sighed, “it doesn’t seem to help us much. Perhaps we had better examine modern literature next. Liz, it’s your turn.”

Elizabeth rose and said that in order to prosecute her enquiry she had dressed as a man and been taken for a reviewer.

“I have read new books pretty steadily for the past five years,” said she. “Mr. Wells is the most popular living writer; then comes Mr. Arnold Bennett; then Mr. Compton Makenzie; Mr. McKenna and Mr. Walpole may be bracketed together.” She sat down.

“But you’ve told us nothing!” we expostulated. “Or do you mean that these gentlemen have greatly surpassed Jane-Elliot and that English fiction is — where’s that review of yours? Oh, yes, ‘safe in their hands.’”

“Safe, quite safe,” she said, shifting uneasily from foot to foot. “And I’m sure that they give away even more than they receive.”

We were all sure of that. “But,” we pressed her, “do they write good books?”

“Good books?” she said, looking at the ceiling “You must remember,” she began, speaking with extreme rapidity, “that fiction is the mirror of life. And you can’t deny that education is of the highest importance, and that it would be extremely annoying, if you found yourself alone at Brighton late at night, not to know which was the best boarding house to stay at, and suppose it was a dripping Sunday evening — wouldn’t it be nice to go to the Movies?”

“But what has that got to do with it?” we asked.

“Nothing — nothing — nothing whatever,” she replied.

“Well, tell us the truth,” we bade her.

“The truth? But isn’t it wonderful,” she broke off —“Mr. Chitter has written a weekly article for the past thirty years upon love or hot buttered toast and has sent all his sons to Eton —”

“The truth!” we demanded.

“Oh, the truth,” she stammered, “the truth has nothing to do with literature,” and sitting down she refused to say another word.

It all seemed to us very inconclusive.

“Ladies, we must try to sum up the results,” Jane was beginning, when a hum, which had been heard for some time through the open window, drowned her voice.

“War! War! War! Declaration of War!” men were shouting in the street below.

We looked at each other in horror.

“What war?” we cried. “What war?” We remembered, too late, that we had never thought of sending anyone to the House of Commons. We had forgotten all about it. We turned to Poll, who had reached the history shelves in the London Library, and asked her to enlighten us.

“Why,” we cried, “do men go to war?”

“Sometimes for one reason, sometimes for another,” she replied calmly. “In 1760, for example —” The shouts outside drowned her words. “Again in 1797 — in 1804 — It was the Austrians in 1866-1870 was the Franco-Prussian — In 1900 on the other hand —”

“But it’s now 1914!” we cut her short.

“Ah, I don’t know what they’re going to war for now,” she admitted.

* * * *

The war was over and peace was in process of being signed, when I once more found myself with Castalia in the room where our meetings used to be held. We began idly turning over the pages of our old minute books. “Queer,” I mused, “to see what we were thinking five years ago.” “We are agreed,” Castalia quoted, reading over my shoulder, “that it is the object of life to produce good people and good books.” We made no comment upon that. “A good man is at any rate honest, passionate and unworldly.” “What a woman’s language!” I observed. “Oh, dear,” cried Castalia, pushing the book away from her, “what fools we were! It was all Poll’s father’s fault,” she went on. “I believe he did it on purpose — that ridiculous will, I mean, forcing Poll to read all the books in the London Library. If we hadn’t learnt to read,” she said bitterly, “we might still have been bearing children in ignorance and that I believe was the happiest life after all. I know what you’re going to say about war,” she checked me, “and the horror of bearing children to see them killed, but our mothers did it, and their mothers, and their mothers before them. And they didn’t complain. They couldn’t read. I’ve done my best,” she sighed, “to prevent my little girl from learning to read, but what’s the use? I caught Ann only yesterday with a newspaper in her hand and she was beginning to ask me if it was ‘true.’ Next she’ll ask me whether Mr. Lloyd George is a good man, then whether Mr. Arnold Bennett is a good novelist, and finally whether I believe in God. How can I bring my daughter up to believe in nothing?” she demanded.

“Surely you could teach her to believe that a man’s intellect is, and always will be, fundamentally superior to a woman’s?” I suggested. She brightened at this and began to turn over our old minutes again. “Yes,” she said, “think of their discoveries, their mathematics, their science, their philosophy, their scholarship —” and then she began to laugh, “I shall never forget old Hobkin and the hairpin,” she said, and went on reading and laughing and I thought she was quite happy, when suddenly she drew the book from her and burst out, “Oh, Cassandra, why do you torment me? Don’t you know that our belief in man’s intellect is the greatest fallacy of them all?” “What?” I exclaimed. “Ask any journalist, schoolmaster, politician or public house keeper in the land and they will all tell you that men are much cleverer than women.” “As if I doubted it,” she said scornfully. “How could they help it? Haven’t we bred them and fed and kept them in comfort since the beginning of time so that they may be clever even if they’re nothing else? It’s all our doing!” she cried. “We insisted upon having intellect and now we’ve got it. And it’s intellect,” she continued, “that’s at the bottom of it. What could be more charming than a boy before he has begun to cultivate his intellect? He is beautiful to look at; he gives himself no airs; he understands the meaning of art and literature instinctively; he goes about enjoying his life and making other people enjoy theirs. Then they teach him to cultivate his intellect. He becomes a barrister, a civil servant, a general, an author, a professor. Every day he goes to an office. Every year he produces a book. He maintains a whole family by the products of his brain — poor devil! Soon he cannot come into a room without making us all feel uncomfortable; he condescends to every woman he meets, and dares not tell the truth even to his own wife; instead of rejoicing our eyes we have to shut them if we are to take him in our arms. True, they console themselves with stars of all shapes, ribbons of all shades, and incomes of all sizes — but what is to console us? That we shall be able in ten years’ time to spend a weekend at Lahore? Or that the least insect in Japan has a name twice the length of its body? Oh, Cassandra, for Heaven’s sake let us devise a method by which men may bear children! It is our only chance. For unless we provide them with some innocent occupation we shall get neither good people nor good books; we shall perish beneath the fruits of their unbridled activity; and not a human being will survive to know that there once was Shakespeare!”

“It is too late,” I replied. “We cannot provide even for the children that we have.”

“And then you ask me to believe in intellect,” she said.

While we spoke, man were crying hoarsely and wearily in the street, and, listening, we heard that the Treaty of Peace had just been signed. The voices died away. The rain was falling and interfered no doubt with the proper explosion of the fireworks.

“My cook will have bought the Evening News,” said Castalia, “and Ann will be spelling it out over her tea. I must go home.”

“It’s no good — not a bit of good,” I said. “Once she knows how to read there’s only one thing you can teach her to believe in — and that is herself.”

“Well, that would be a change,” sighed Castalia.

So we swept up the papers of our Society, and, though Ann was playing with her doll very happily, we solemnly made her a present of the lot and told her we had chosen her to be President of the Society of the future — upon which she burst into tears, poor little girl.

Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf

2. A Society

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Monday or Tuesday, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

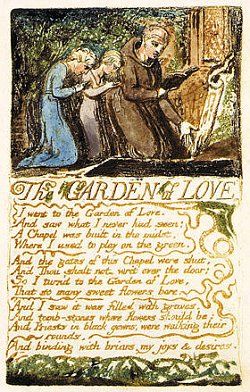

William Blake

(1757-1827)

The Garden Of Love

I went to the Garden of Love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A Chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of the Chapel were shut,

And Thou shalt not writ over the door;

So I turn’d to the Garden of Love

That so many sweet flowers bore,

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tomb-stones where flowers should be:

And Priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys & desires.

William Blake poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blake, William

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

(1806-1861)

If Thou Must Love Me

If thou must love me, let it be for naught

Except for love’s sake only. Do not say

“I love her for her smile…her look…her way

Of speaking gently…for a trick of thought

That falls in well with mine, and certes brought

A sense of pleasant ease on such a day” –

For these things in themselves, Belovéd, may

Be changed, or change for thee, – and love, so wrought,

May be unwrought so. Neither love me for

Thine own dear pity’s wiping my cheeks dry, –

A creature might forget to weep, who bore

Thy comfort long, and lose thy love thereby!

But love me for love’s sake, that evermore

Thou mayst love on, through love’s eternity.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Barrett Browning, Elizabeth

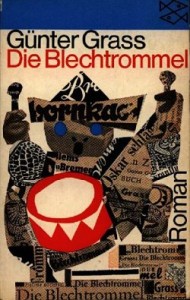

De Duitse schrijver Günter Grass is op 13 april in Lübeck overleden. Grass is 87 jaar oud geworden. In 1999 ontving hij de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur.

De Duitse schrijver Günter Grass is op 13 april in Lübeck overleden. Grass is 87 jaar oud geworden. In 1999 ontving hij de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur.

Het romandebuut van Günter Grass is het beroemd geworden boek Die Blechtrommel (De blikken trommel) uit 1959. Samen met Kat en Muis (Katz und Maus) en Hondenjaren (Hundejahre) vormden ze de zogenoemde Danzig-trilogie.

De trilogie handelt over de opkomst van het nazisme, de verschrikkingen van de oorlog en de schuldgevoelens die overbleven nadat Duitsland was verslagen. Grass putte vaak uit zijn eigen ervaringen als militair en krijgsgevangene. Zijn laatste boek was De woorden van Grimm uit 2010.

Günter Grass stierf aan de gevolgen van een longinfectie

Kurze bibliographie

Romane, Novellen

Danziger Trilogie

-Die Blechtrommel. Roman. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1959.

-Katz und Maus. Novelle. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1961.

-Hundejahre. Roman. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1963.

örtlich betäubt. Roman. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1969.

Aus dem Tagebuch einer Schnecke. Roman. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1972.

Der Butt. Roman. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1977.

Das Treffen in Telgte. Erzählung. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1979.

Kopfgeburten oder Die Deutschen sterben aus. Erzählung. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1980.

Die Rättin. Roman. Luchterhand. Darmstadt und Neuwied 1986.

Unkenrufe. Erzählung. Steidl, Göttingen 1992.

Ein weites Feld. Roman. Steidl, Göttingen 1995.

Mein Jahrhundert. Roman. Steidl, Göttingen 1999.

Im Krebsgang. Novelle. Steidl, Göttingen 2002.

Beim Häuten der Zwiebel. Erinnerungen. Steidl, Göttingen 2006.

Die Box. Roman. Steidl, Göttingen 2008.

Unterwegs von Deutschland nach Deutschland. Tagebuch 1990. Steidl, Göttingen 2009.

Grimms Wörter. Eine Liebeserklärung. Steidl, Göttingen 2010.

Lyrik

Die Vorzüge der Windhühner. 1956.

Gleisdreieck. 1960.

Ausgefragt. 1967.

Gesammelte Gedichte. 1971.

Letzte Tänze. 2003.

Lyrische Beute. 2004.

Dummer August. 2007.

Was gesagt werden muss. Einzelveröffentlichung, 2012.

Europas Schande. Einzelveröffentlichung, 2012.[97]

Eintagsfliegen. 2012.

Poesiealbum 302. Märkischer Verlag, Wilhelmshorst 2012.

Grafik, Skulpturen, Plastiken

Der Butt. Plastik im Hafen von Sonderburg, Dänemark.

Zeichnungen und Schreiben. Das bildnerische Werk des Schriftstellers Günter Grass. Band I: Zeichnungen und Texte 1954–1977. Hrsg. von Anselm Dreher. Darmstadt/Neuwied 1982

Zeichnungen und Schreiben II. Radierungen und Texte 1972–1982. Hrsg. von Anselm Dreher. Darmstadt/Neuwied 1984.

In Kupfer, auf Stein. Die Radierungen und Lithographien 1972–1986. Göttingen 1986.

Graphik und Plastik. Bearbeitet von Werner Timm. Regensburg 1987 (Ausstellungskatalog).

Hundert Zeichnungen 1955–1987. Ausstellungskatalog der Kunsthalle Kiel. Hrsg. von Jens Christian Jensen. Kiel 1987.

Dramen

Die bösen Köche. Ein Drama. 1956.

Hochwasser. Ein Stück in zwei Akten. 1957.

Onkel, Onkel. Ein Spiel in vier Akten. 1958.

Hoch zehn Minuten bis Buffalo. Ein Spiel in einem Akt. 1958.

Die Plebejer proben den Aufstand. Ein deutsches Trauerspiel. 1966.

Briefe, Reden usw

„O Susanna“. Ein Jazzbilderbuch. Blues, Balladen, Spirituals, Jazz. Bilder: Horst Geldmacher. Deutsche Texte: Günter Grass. Musikarbeit: Herman Wilson. Mit einem Nachwort von Joachim-Ernst Berendt. Köln und Berlin: Kiepenheuer & Witsch 1959.

(mit Pavel Kohout) Briefe über die Grenze. Versuch eines Ost-West-Dialogs. (1968)

Über das Selbstverständliche. Reden – Aufsätze – Offene Briefe – Kommentare. (1968)

Die Vogelscheuchen. Ballettlibretto (UA 1970)

Der Bürger und seine Stimme. Reden Aufsätze Kommentare. (1974)

Denkzettel. Politische Reden und Aufsätze 1965–1976. (1978)

Widerstand lernen. Politische Gegenreden 1980–1983. (1984)

Zunge zeigen. Ein Tagebuch in Zeichnungen. (1988)

Rede vom Verlust. Über den Niedergang der politischen Kultur im geeinten Deutschland. (1992)

Ein Schnäppchen namens DDR. Letzte Reden vorm Glockengeleut. (1993)

Günter Grass, Ōe Kenzaburō: Gestern vor 50 Jahren. Ein deutsch-japanischer Briefwechsel. 1. Auflage. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 1995.

Rede über den Standort (1997)

Zeit, sich einzumischen. Die Kontroverse um Günter Grass und die Laudatio auf Yasar Kemal in der Paulskirche (1998)

Vom Abenteuer der Aufklärung. Werkstattgespräche mit Harro Zimmermann. (1999)

Günter Grass – Helen Wolff. Briefe 1959–1994. (2003).

Hans Christian Andersens Märchen – gesehen von Günter Grass (2005).

Uwe Johnson – Anna Grass – Günter Grass. Der Briefwechsel 1961–1984. (2007).

Martin Kölbel (Hrsg.): Willy Brandt und Günter Grass – Der Briefwechsel. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2013.

Verfilmungen

Die Blechtrommel. Spielfilm, Deutschland, Polen, Frankreich, Jugoslawien, 1980, 142 Min., Regie: Volker Schlöndorff, u. a. mit Mario Adorf als Alfred Matzerath, Angela Winkler als Agnes Matzerath, David Bennent als Oskar, Katharina Thalbach als Maria Matzerath

Katz und Maus, Spielfilm, BRD, 1967, 88 Min., Regie: Hansjürgen Pohland, u. a. mit Wolfgang Neuss als Pilenz

Mein Jahrhundert, Fernsehlesung. Günter Grass liest Mein Jahrhundert im Deutschen Theater Göttingen. Produktion Radio Bremen/3sat 1999.

Die Rättin. Fernsehfilm, Deutschland, 87 Min., Regie: Martin Buchhorn, Erstausstrahlung: ARD, 14. Oktober 1997, u. a. mit Matthias Habich als Markus Frank

Unkenrufe – Zeit der Versöhnung. Spielfilm, Deutschland, Polen, 2005, 98 Min., Regie: Robert Glinski

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Günter Grass, In Memoriam

Hendrik Marsman

(1899-1940)

De vrouw van de zon

‘Ik zag een vrouw, die schreed

alsof zij nooit zou sterven.’

A. Roland Holst

Vrij en eeuwig,

tijdeloos ontheven,

in een hoog en onaanrandbaar zweven,

schrijdt gij,

koninklijk geheven,

langs de blauwe muren van het licht.

o! de sneeuwstorm van uw gouden mantel

o! de zon, het diamanten vlamsel,

dat de heemlen uitstroomt uwer haren

langs de wolkenloze bergen van de dag

o! de nacht –

waar uw fonkelende gouden tocht

in de hoge, sidderende loop der herten

eenzaam eindigt,

in de diepste verten.

Hendrik Marsman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Marsman, Hendrik

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature