Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

A MATTER OF DOCTRINE

There was great excitement in Miltonville over the advent of a most eloquent and convincing minister from the North.

The beauty about the Rev. Thaddeus Warwick was that he was purely and simply a man of the doctrine. He had no emotions, his sermons were never matters of feeling; but he insisted so strongly upon the constant presentation of the tenets of his creed that his presence in a town was always marked by the enthusiasm and joy of religious disputation.

The beauty about the Rev. Thaddeus Warwick was that he was purely and simply a man of the doctrine. He had no emotions, his sermons were never matters of feeling; but he insisted so strongly upon the constant presentation of the tenets of his creed that his presence in a town was always marked by the enthusiasm and joy of religious disputation.

The Rev. Jasper Hayward, coloured, was a man quite of another stripe. With him it was not so much what a man held as what he felt. The difference in their characteristics, however, did not prevent him from attending Dr. Warwick’s series of sermons, where, from the vantage point of the gallery, he drank in, without assimilating, that divine’s words of wisdom.

Especially was he edified on the night that his white brother held forth upon the doctrine of predestination. It was not that he understood it at all, but that it sounded well and the words had a rich ring as he champed over them again and again.

Mr. Hayward was a man for the time and knew that his congregation desired something new, and if he could supply it he was willing to take lessons even from a white co-worker who had neither “de spi’it ner de fiah.” Because, as he was prone to admit to himself, “dey was sump’in’ in de unnerstannin’.”

He had no idea what plagiarism is, and without a single thought of wrong, he intended to reproduce for his people the religious wisdom which he acquired at the white church. He was an innocent beggar going to the doors of the well-provided for cold spiritual victuals to warm over for his own family. And it would not be plagiarism either, for this very warming-over process would save it from that and make his own whatever he brought. He would season with the pepper of his homely wit, sprinkle it with the salt of his home-made philosophy, then, hot with the fire of his crude eloquence, serve to his people a dish his very own. But to the true purveyor of original dishes it is never pleasant to know that someone else holds the secret of the groundwork of his invention.

It was then something of a shock to the Reverend Mr. Hayward to be accosted by Isaac Middleton, one of his members, just as he was leaving the gallery on the night of this most edifying of sermons.

Isaac laid a hand upon his shoulder and smiled at him benevolently.

“How do, Brothah Hayward,” he said, “you been sittin’ unner de drippin’s of de gospel, too?”

“Yes, I has been listenin’ to de wo’ds of my fellow-laborah in de vineya’d of de Lawd,” replied the preacher with some dignity, for he saw vanishing the vision of his own glory in a revivified sermon on predestination.

Isaac linked his arm familiarly in his pastor’s as they went out upon the street.

“Well, what you t’ink erbout pre-o’dination an’ fo’-destination any how?”

“It sutny has been pussented to us in a powahful light dis eve’nin’.”

“Well, suh, hit opened up my eyes. I do’ know when I’s hyeahed a sehmon dat done my soul mo’ good.”

“It was a upliftin’ episode.”

“Seem lak ‘co’din’ to de way de brothah ‘lucidated de matter to-night dat evaht’ing done sot out an’ cut an’ dried fu’ us. Well dat’s gwine to he’p me lots.”

“De gospel is allus a he’p.”

“But not allus in dis way. You see I ain’t a eddicated man lak you, Brothah Hayward.”

“We can’t all have de same ‘vantages,” the preacher condescended. “But what I feels, I feels, an’ what I unnerstan’s, I unnerstan’s. The Scripture tell us to get unnerstannin’.”

“Well, dat’s what I’s been a-doin’ to-night. I’s been a-doubtin’ an’ a-doubtin’, a-foolin’ erroun’ an’ wonderin’, but now I unnerstan’.”

“‘Splain yo’se’f, Brothah Middleton,” said the preacher.

“Well, suh, I will to you. You knows Miss Sally Briggs? Huh, what say?”

The Reverend Hayward had given a half discernible start and an exclamation had fallen from his lips.

“What say?” repeated his companion.

“I knows de sistah ve’y well, she bein’ a membah of my flock.”

“Well, I been gwine in comp’ny wit dat ooman fu’ de longes’. You ain’t nevah tasted none o’ huh cookin’, has you?”

“I has ‘sperienced de sistah’s puffo’mances in dat line.”

“She is the cookin’est ooman I evah seed in all my life, but howsomedever, I been gwine all dis time an’ I ain’ nevah said de wo’d. I nevah could git clean erway f’om huh widout somep’n’ drawin’ me back, an’ I didn’t know what hit was.”

The preacher was restless.

“Hit was des dis away, Brothah Hayward, I was allus lingerin’ on de brink, feahful to la’nch away, but now I’s a-gwine to la’nch, case dat all dis time tain’t been nuffin but fo’-destination dat been a-holdin’ me on.”

“Ahem,” said the minister; “we mus’ not be in too big a hu’y to put ouah human weaknesses upon some divine cause.”

“I ain’t a-doin’ dat, dough I ain’t a-sputin’ dat de lady is a mos’ oncommon fine lookin’ pusson.”

“I has only seed huh wid de eye of de spi’it,” was the virtuous answer, “an’ to dat eye all t’ings dat are good are beautiful.”

“Yes, suh, an’ lookin’ wid de cookin’ eye, hit seem lak’ I des fo’destinated fu’ to ma’y dat ooman.”

“You say you ain’t axe huh yit?”

“Not yit, but I’s gwine to ez soon ez evah I gets de chanst now.”

“Uh, huh,” said the preacher, and he began to hasten his steps homeward.

“Seems lak you in a pow’ful hu’y to-night,” said his companion, with some difficulty accommodating his own step to the preacher’s masterly strides. He was a short man and his pastor was tall and gaunt.

“I has somp’n’ on my min,’ Brothah Middleton, dat I wants to thrash out to-night in de sollertude of my own chambah,” was the solemn reply.

“Well, I ain’ gwine keep erlong wid you an’ pestah you wid my chattah, Brothah Hayward,” and at the next corner Isaac Middleton turned off and went his way, with a cheery “so long, may de Lawd set wid you in yo’ meddertations.”

“So long,” said his pastor hastily. Then he did what would be strange in any man, but seemed stranger in so virtuous a minister. He checked his hasty pace, and, after furtively watching Middleton out of sight, turned and retraced his steps in a direction exactly opposite to the one in which he had been going, and toward the cottage of the very Sister Griggs concerning whose charms the minister’s parishioner had held forth.

It was late, but the pastor knew that the woman whom he sought was industrious and often worked late, and with ever increasing eagerness he hurried on. He was fully rewarded for his perseverance when the light from the window of his intended hostess gleamed upon him, and when she stood in the full glow of it as the door opened in answer to his knock.

“La, Brothah Hayward, ef it ain’t you; howdy; come in.”

“Howdy, howdy, Sistah Griggs, how you come on?”

“Oh, I’s des tol’able,” industriously dusting a chair. “How’s yo’se’f?”

“I’s right smaht, thankee ma’am.”

“W’y, Brothah Hayward, ain’t you los’ down in dis paht of de town?”

“No, indeed, Sistah Griggs, de shep’erd ain’t nevah los’ no whaih dey’s any of de flock.” Then looking around the room at the piles of ironed clothes, he added: “You sutny is a indust’ious ooman.”

“I was des ’bout finishin’ up some i’onin’ I had fu’ de white folks,” smiled Sister Griggs, taking down her ironing-board and resting it in the corner. “Allus when I gits thoo my wo’k at nights I’s putty well tiahed out an’ has to eat a snack; set by, Brothah Hayward, while I fixes us a bite.”

“La, sistah, hit don’t skacely seem right fu’ me to be a-comin’ in hyeah lettin’ you fix fu’ me at dis time o’ night, an’ you mighty nigh tuckahed out, too.”

“Tsch, Brothah Hayward, taint no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan it is lookin’ out fu’ one.”

Hayward flashed a quick upward glance at his hostess’ face and then repeated slowly, “Yes’m, dat sutny is de trufe. I ain’t nevah t’ought o’ that befo’. Hit ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan hit is fu’ one,” and though he was usually an incessant talker, he lapsed into a brown study.

Be it known that the Rev. Mr. Hayward was a man of a very level head, and that his bachelorhood was a matter of economy. He had long considered matrimony in the light of a most desirable estate, but one which he feared to embrace until the rewards for his labours began looking up a little better. But now the matter was being presented to him in an entirely different light. “Hit ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan fu’ one.” Might that not be the truth after all. One had to have food. It would take very little more to do for two. One had to have a home to live in. The same house would shelter two. One had to wear clothes. Well, now, there came the rub. But he thought of donation parties, and smiled. Instead of being an extravagance, might not this union of two beings be an economy? Somebody to cook the food, somebody to keep the house, and somebody to mend the clothes.

His reverie was broken in upon by Sally Griggs’ voice. “Hit do seem lak you mighty deep in t’ought dis evenin’, Brothah Hayward. I done spoke to you twicet.”

“Scuse me, Sistah Griggs, my min’ has been mighty deeply ‘sorbed in a little mattah o’ doctrine. What you say to me?”

“I say set up to the table an’ have a bite to eat; tain’t much, but ‘sich ez I have’—you know what de ‘postle said.”

The preacher’s eyes glistened as they took in the well-filled board. There was fervour in the blessing which he asked that made amends for its brevity. Then he fell to.

Isaac Middleton was right. This woman was a genius among cooks. Isaac Middleton was also wrong. He, a layman, had no right to raise his eyes to her. She was the prize of the elect, not the quarry of any chance pursuer. As he ate and talked, his admiration for Sally grew as did his indignation at Middleton’s presumption.

Meanwhile the fair one plied him with delicacies, and paid deferential attention whenever he opened his mouth to give vent to an opinion. An admirable wife she would make, indeed.

At last supper was over and his chair pushed back from the table. With a long sigh of content, he stretched his long legs, tilted back and said: “Well, you done settled de case ez fur ez I is concerned.”

“What dat, Brothah Hayward?” she asked.

“Well, I do’ know’s I’s quite prepahed to tell you yit.”

“Hyeah now, don’ you remembah ol’ Mis’ Eve? Taint nevah right to git a lady’s cur’osity riz.”

“Oh, nemmine, nemmine, I ain’t gwine keep yo’ cur’osity up long. You see, Sistah Griggs, you done ‘lucidated one p’int to me dis night dat meks it plumb needful fu’ me to speak.”

She was looking at him with wide open eyes of expectation.

“You made de ’emark to-night, dat it ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out aftah two dan one.”

“Oh, Brothah Hayward!”

“Sistah Sally, I reckernizes dat, an’ I want to know ef you won’t let me look out aftah we two? Will you ma’y me?”

She picked nervously at her apron, and her eyes sought the floor modestly as she answered, “Why, Brothah Hayward, I ain’t fittin’ fu’ no sich eddicated man ez you. S’posin’ you’d git to be pu’sidin’ elder, er bishop, er somp’n’ er othah, whaih’d I be?”

He waved his hand magnanimously. “Sistah Griggs, Sally, whatevah high place I may be fo’destined to I shall tek my wife up wid me.”

This was enough, and with her hearty yes, the Rev. Mr. Hayward had Sister Sally close in his clerical arms. They were not through their mutual felicitations, which were indeed so enthusiastic as to drown the sound of a knocking at the door and the ominous scraping of feet, when the door opened to admit Isaac Middleton, just as the preacher was imprinting a very decided kiss upon his fiancee’s cheek.

“Wha’—wha'” exclaimed Middleton.

The preacher turned. “Dat you, Isaac?” he said complacently. “You must ‘scuse ouah ‘pearance, we des got ingaged.”

The fair Sally blushed unseen.

“What!” cried Isaac. “Ingaged, aftah what I tol’ you to-night.” His face was a thundercloud.

“Yes, suh.”

“An’ is dat de way you stan’ up fu’ fo’destination?”

This time it was the preacher’s turn to darken angrily as he replied, “Look a-hyeah, Ike Middleton, all I got to say to you is dat whenevah a lady cook to please me lak dis lady do, an’ whenevah I love one lak I love huh, an’ she seems to love me back, I’s a-gwine to pop de question to huh, fo’destination er no fo’destination, so dah!”

The moment was pregnant with tragic possibilities. The lady still stood with bowed head, but her hand had stolen into her minister’s. Isaac paused, and the situation overwhelmed him. Crushed with anger and defeat he turned toward the door.

On the threshold he paused again to say, “Well, all I got to say to you, Hayward, don’ you nevah talk to me no mor’ nuffin’ ’bout doctrine!”

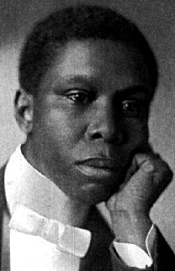

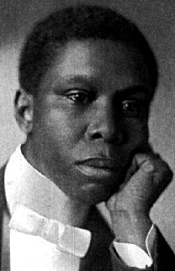

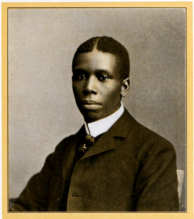

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

A Matter Of Doctrine

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive African American Literature, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Thija komt buiten met haar reistas. Ze heeft een mantelpakje aan, lichtgrijs, rood afgebiesd. Ze ziet eruit als een dochter van een deftige familie, die naar kostschool vertrekt. Ze heeft een strik in het haar, net als op zondag wanneer ze naar de kerk gaat.

Ze zet de reistas op de grond en gaat erop zitten. Haar onmogelijk lange rok hangt op het trottoir, zodat ze hem wat op moet trekken.

Ze zet de reistas op de grond en gaat erop zitten. Haar onmogelijk lange rok hangt op het trottoir, zodat ze hem wat op moet trekken.

Mels gaat op de stoep zitten, aan de andere kant van de straat, want hij is ontzettend boos.

Thija vijlt haar nagels.

`Hou op met dat gedoe’, zegt hij boos.

`Ik schrijf je toch’, zegt Thija. `Ik vergeet je echt niet.’

`Weet je nu waar je gaat wonen?’

`Rotterdam, dat zei ik toch. Ik schrijf je volgende week al. Elke week schrijf ik.’

Er rijdt een auto door de straat, langzaam. Passeert hen. Even is ze uit zijn ogen weg. Dat even doet al pijn.

`Ik heb een cadeau voor je.’

`Wat is het?’ vraagt hij.

`Kom het maar halen.’

`Je moet het me brengen.’

Blijkbaar hoort ze aan zijn toon dat hij niet toe zal geven, zeker niet nu hij zo geweldig boos is over het afscheid. Ze staat op en steekt de straat over. De rok hangt bijna op haar schoenen. De neuzen glimmen.

Uit haar reistas pakt ze een doosje, met een lint eromheen.

`Je mag het pas uitpakken als ik weg ben.’

`Goed.’

Hij neemt het pakje aan en steekt het in zijn zak.

Ze komt naast hem zitten. Even is het alsof er niets aan de hand is, alsof ze een spelletje gaan doen dat de hele dag zal duren. Zoals ze het zo vaak gedaan hebben. Raden waar je naar kijkt. De stemmen van voorbijgangers nadoen. Of gewoon verhalen vertellen.

Haar moeder komt buiten en zet een paar dozen met huisraad op de stoep.

`Nemen jullie niet alles mee?’

`De koffers worden later opgehaald. Ze zijn nooit uitgepakt. Eigenlijk hebben we er niets van nodig. Voorlopig gaan we in een hotel wonen, tot we een huis hebben gevonden.’

Ze slaat een arm om hem heen. Hij voelt hoe warm haar arm is, ook al is die nog zo dun. Haar huid is van zijde.

`Ik wil liever blijven’, zegt ze. `Ik vind het net zo erg als jij. Maar het kan niet. Als je ouders verhuizen, moet je mee.’

Een auto rijdt voor en stopt voor haar deur. Thija’s vader stapt uit. Mels heeft hem nog nooit gezien. Hij schrikt een beetje van hem. Het is een oudere, forse en grijze man. Niet veel jonger dan zijn grootvader. Niet de vader die hij had verwacht. De man groet hem niet, hij kijkt gewoon over hem heen. Het is een man die het druk heeft, dat kun je zo aan hem zien. Daarom neemt hij hen nu mee naar Rotterdam, om hen vaker te zien. Mels snapt het, maar het is niet eerlijk.

Haar vader laadt de dozen in de achterbak en klopt het stof van zijn handen.

Mels voelt de tranen langs zijn wangen lopen.

`Niet doen’, zegt ze. `Ik schrijf je toch. Ik schrijf je alles wat ik nog over China weet.’

`Je gaat naar Rotterdam!’

`Kom op, we hebben weinig tijd’, zegt haar moeder. `Je moet nu afscheid nemen.’ Ze strijkt Mels over het haar en loopt naar de auto.

`Nou, ik moet gaan.’ Thija staat op en geeft hem een kus.

Door zijn tranen heen ziet Mels haar in de auto stappen. Hij ziet hoe die stomme rok van haar even blijft haken. Ze valt bijna de auto in. Als hij een pistool had zou hij haar vader doodschieten. Maar misschien ook niet. Hij weet het niet. Hij is verlamd. Hij zou niet eens kunnen schieten.

De auto rijdt de straat uit. Ze zwaait. Hij wil terugzwaaien, maar het gaat niet. Hij is versteend. Het liefst was hij dood.

Pas als de auto al een uur weg is, of misschien wel twee uur, gaat hij naar huis.

Op zijn kamer pakt hij het cadeautje uit. Het is papier over papier. Laag na laag. Het pakje wordt steeds kleiner. Ten slotte blijft er een klein velletje van een kladblok over.

`Misschien gaan we zo ver weg dat ik je nooit meer zal zien’, leest hij. `We blijven maar even in Rotterdam. Een paar dagen, of een paar weken. Dan vertrekken we naar China, waar mijn vader op een theeplantage gaat werken. Ik weet niet eens in welk China. Hij zegt er niets over tegen mij, maar ik denk dat hij Formosa bedoelt. Meer weet ik er ook niet van. Misschien kom ik later naar Nederland terug, om te studeren. Ik moest dit opschrijven, want ik kon het je niet vertellen omdat ik zelf niet wil dat het gebeurt. Ik wil niet zonder jou naar China. Maar ook al zou ik je nooit meer zien, je moet weten dat ik altijd net zo veel van jou zal houden als van Tijger. Thija.’

Liggend op bed perst hij zijn hoofd zo vast in het kussen dat alles zwart wordt. Hij wil net zo dood zijn als Tijger.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (099)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

THE INTERFERENCE OF PATSY ANN

Patsy Ann Meriweather would have told you that her father, or more properly her “pappy,” was a “widover,” and she would have added in her sad little voice, with her mournful eyes upon you, that her mother had “bin daid fu’ nigh onto fou’ yeahs.” Then you could have wept for Patsy, for her years were only thirteen now, and since the passing away of her mother she had been the little mother for her four younger brothers and sisters, as well as her father’s house-keeper.

But Patsy Ann never complained; she was quite willing to be all that she had been until such time as Isaac and Dora, Cassie and little John should be old enough to care for themselves, and also to lighten some of her domestic burdens. She had never reckoned upon any other manner of release. In fact her youthful mind was not able to contemplate the possibility of any other manner of change. But the good women of Patsy’s neighbourhood were not the ones to let her remain in this deplorable state of ignorance. She was to be enlightened as to other changes that might take place in her condition, and of the unspeakable horrors that would transpire with them.

But Patsy Ann never complained; she was quite willing to be all that she had been until such time as Isaac and Dora, Cassie and little John should be old enough to care for themselves, and also to lighten some of her domestic burdens. She had never reckoned upon any other manner of release. In fact her youthful mind was not able to contemplate the possibility of any other manner of change. But the good women of Patsy’s neighbourhood were not the ones to let her remain in this deplorable state of ignorance. She was to be enlightened as to other changes that might take place in her condition, and of the unspeakable horrors that would transpire with them.

It was upon the occasion that little John had taken it into his infant head to have the German measles just at the time that Isaac was slowly recovering from the chicken-pox. Patsy Ann’s powers had been taxed to the utmost, and Mrs. Caroline Gibson had been called in from next door to superintend the brewing of the saffron tea, and for the general care of the fretful sufferer.

To Patsy Ann, then, in ominous tone, spoke this oracle. “Patsy Ann, how yo’ pappy doin’ sence Matildy died?” “Matildy” was the deceased wife.

“Oh, he gittin’ ‘long all right. He was mighty broke up at de fus’, but he ‘low now dat de house go on de same’s ef mammy was a-livin’.”

“Oom huh,” disdainfully; “Oom huh. Yo’ mammy bin daid fou’ yeahs, ain’t she?”

“Yes’m; mighty nigh.”

“Oom huh; fou’ yeahs is a mighty long time fu’ a colo’d man to wait; but we’n he do wait dat long, hit’s all de wuss we’n hit do come.”

“Pap bin wo’kin right stiddy at de brick-ya’d,” said Patsy, in loyal defence against some vaguely implied accusation, “an’ he done put some money in de bank.”

“Bad sign, bad sign,” and Mrs. Gibson gave her head a fearsome shake.

But just then the shrill voice of little John calling for attention drew her away and left Patsy Ann to herself and her meditations.

What could this mean?

When that lady had finished ministering to the sick child and returned, Patsy Ann asked her, “Mis’ Gibson, what you mean by sayin’ ‘bad sign, bad sign?'”

Again the oracle shook her head sagely. Then she answered, “Chil’, you do’ know de dev’ment dey is in dis worl’.”

“But,” retorted the child, “my pappy ain’ up to no dev’ment, ‘case he got ‘uligion an’ bin baptised.”

“Oom-m,” groaned Sistah Gibson, “dat don’ mek a bit o’ diffunce. Who is any mo’ ma’yin’ men den de preachahs demse’ves? W’y Brothah ‘Lias Scott done tempted matermony six times a’ready, an’ ‘s lookin’ roun’ fu’ de sebent, an’ he’s a good man, too.”

“Ma’yin’,” said Patsy breathlessly.

“Yes, honey, ma’yin’, an’ I’s afeared yo’ pappy’s got notions in his haid, an’ w’en a widower git gals in his haid dey ain’ no use a-pesterin’ wid ’em, ‘case dey boun’ to have dey way.”

“Ma’yin’,” said Patsy to herself reflectively. “Ma’yin’.” She knew what it meant, but she had never dreamed of the possibility of such a thing in connection with her father. “Ma’yin’,” and yet the idea of it did not seem so very unalluring.

She spoke her thoughts aloud.

“But ef pap ‘u’d ma’y, Mis’ Gibson, den I’d git a chanct to go to school. He allus sayin’ he mighty sorry ’bout me not goin’.”

“Dah now, dah now,” cried the woman, casting a pitying glance at the child, “dat’s de las’ t’ing. He des a feelin’ roun’ now. You po’, ign’ant, mothahless chil’. You ain’ nevah had no step-mothah, an’ you don’ know what hit means.”

“But she’d tek keer o’ the chillen,” persisted Patsy.

“Sich tekin’ keer of ’em ez hit ‘u’d be. She’d keer fu’ ’em to dey graves. Nobody cain’t tell me nuffin ’bout step-mothahs, case I knows ’em. Dey ain’ no ooman goin’ to tek keer o’ nobody else’s chile lak she’d tek keer o’ huh own,” and Patsy felt a choking come into her throat and a tight sensation about her heart while she listened as Mrs. Gibson regaled her with all the choice horrors that are laid at the door of step-mothers.

From that hour on, one settled conviction took shape and possessed Patsy Ann’s mind; never, if she could help it, would she run the risk of having a step-mother. Come what may, let her be compelled to do what she might, let the hope of school fade from her sight forever and a day—but no step-mother should ever cast her baneful shadow over Patsy Ann’s home.

Experience of life had made her wise for her years, and so for the time she said nothing to her father; but she began to watch him with wary eyes, his goings out and his comings in, and to attach new importance to trifles that had passed unnoticed before by her childish mind.

For instance, if he greased or blacked his boots before going out of an evening her suspicions were immediately aroused and she saw dim visions of her father returning, on his arm the terrible ogress whom she had come to know by the name of step-mother.

Mrs. Gibson’s poison had worked well and rapidly. She had thoroughly inoculated the child’s mind with the step-mother virus, but she had not at the same time made the parent widow-proof, a hard thing to do at best. So it came to pass that with a mysterious horror growing within her, Patsy Ann saw her father black his boots more and more often and fare forth o’ nights and Sunday afternoons.

Finally her little heart could contain its sorrow no longer, and one night when he was later than usual she could not sleep. So she slipped out of bed, turned up the light, and waited for him, determined to have it out, then and there.

He came at last and was all surprise to meet the solemn, round eyes of his little daughter staring at him from across the table.

“W’y, lady gal,” he exclaimed, “what you doin’ up at ‘his time?”

“I sat up fu’ you. I got somep’n’ to ax you, pappy.” Her voice quivered and he snuggled her up in his arms.

“What’s troublin’ my little lady gal now? Is de chillen bin bad?”

She laid her head close against his big breast, and the tears would come as she answered, “No, suh; de chillen bin ez good az good could be, but oh, pappy, pappy, is you got gal in yo’ haid an’ a-goin’ to bring me a step-mothah?”

He held her away from him almost harshly and gazed at her as he queried, “W’y, you po’ baby, you! Who’s bin puttin’ dis hyeah foolishness in yo’ haid?” Then his laugh rang out as he patted her head and drew her close to him again. “Ef yo’ pappy do bring a step-mothah into dis house, Gawd knows he’ll bring de right kin’.”

“Dey ain’t no right kin’,” answered Patsy.

“You don’ know, baby; you don’ know. Go to baid an’ don’ worry.”

He sat up a long time watching the candle sputter, then he pulled off his boots and tiptoed to Patsy’s bedside. He leaned over her. “Po’ little baby,” he said; “what do she know about a step-mothah?” And Patsy saw him and heard him, for she was awake then, and far into the night.

In the eyes of the child her father stood convicted. He had “gal in his haid,” and was going to bring her a step-mother; but it would never be; her resolution was taken.

She arose early the next morning and after getting her father off to work as usual, she took the children into hand. First she scrubbed them assiduously, burnishing their brown faces until they shone again. Then she tussled with their refractory locks, and after that she dressed them out in all the bravery of their best clothes.

Meanwhile her tears were falling like rain, though her lips were shut tight. The children off her mind, she turned her attention to her own toilet, which she made with scrupulous care. Then taking a small tin-type of her mother from the bureau drawer, she put it in her bosom, and leading her little brood she went out of the house, locking the door behind her and placing the key, as was her wont, under the door-step.

Outside she stood for a moment or two, undecided, and then with one long, backward glance at her home she turned and went up the street. At the first corner she paused again, spat in her hand and struck the watery globule with her finger. In the direction the most of the spittle flew, she turned. Patsy Ann was fleeing from home and a step-mother, and Fate had decided her direction for her, even as Mrs. Gibson’s counsels had directed her course.

The child had no idea where she was going. She knew no one to whom she might turn in her distress. Not even with Mrs. Gibson would she be safe from the horror which impended. She had but one impulse in her mind and that was to get beyond the reach of the terrible woman, or was it a monster? who was surely coming after her. On and on she walked through the town with her little band trudging bravely along beside her. People turned to look at the funny group and smiled good-naturedly as they passed, and one man, a little more amused than the rest, shouted after them, “Where you goin’, sis, with that orphan’s home?”

But Patsy Ann’s dignity was impregnable. She walked on with her head in the air, the desire for safety tugging at her heart.

The hours passed and the gentle coolness of morning turned into the fierce heat of noon, and still with frequent rests they trudged on, Patsy ever and anon using her divining hand, unconscious that she was doubling and redoubling on her tracks. When the whistles blew for twelve she got her little brood into the shade of a poplar tree and set them down to the lunch which, thoughtful little mother that she was, she had brought with her. After that they all stretched themselves out on the grass that bordered the sidewalk, for all the children were tired out, and baby John was both sleepy and cross. Even Patsy Ann drowsed and finally dropped into the deep slumber of childhood. They looked too peaceful and serene for passers-by to bother them, and so they slept and slept.

It was past three o’clock when the little guardian awakened with a start, and shook her charges into activity. John wept a little at first, but after a while took up his journey bravely with the rest.

She had just turned into a side street, discouraged and bewildered, when the round face of a coloured woman standing in the doorway of a whitewashed cottage caught her eye and attention. Once more she paused and consulted her watery oracle, then turned to encounter the gaze of the round-faced woman. The oracle had spoken and she turned into the yard.

“Whaih you goin’, honey? You sut’ny look lak you plumb tukahed out. Come in an’ tell me all ’bout yo’se’f, you po’ little t’ing. Dese yo’ little brothas an’ sistahs?”

“Yes’m,” said Patsy Ann.

“W’y, chil’, whaih you goin’?”

“I don’ know,” was the truthful answer.

“You don’ know? Whaih you live?”

“Oh, I live down on Douglas Street,” said Patsy Ann, “an’ I’s runnin’ away f’om home an’ my step-mothah.”

The woman looked keenly at her.

“What yo’ name?” she said.

“My name’s Patsy Ann Meriweather.”

“An’ is yo’ got a step-mothah?”

“No,” said Patsy Ann, “I ain’ got none now, but I’s sut’ny ‘spectin’ one.”

“What you know ’bout step-mothahs, honey?”

“Mis’ Gibson tol’ me. Dey sho’ly is awful, missus, awful.”

“Mis’ Gibson ain’ tol’ you right, honey. You come in hyeah and set down. You ain’ nothin’ mo’ dan a baby yo’se’f, an’ you ain’ got no right to be trapsein’ roun’ dis away.”

Have you ever eaten muffins? Have you eaten bacon with onions? Have you drunk tea? Have you seen your little brother John taken up on a full bosom and rocked to sleep in the most motherly way, with the sweetness and tenderness that only a mother can give? Well, that was Patsy Ann’s case to-night.

And then she laid them along like ten-pins crosswise of her bed and sat for a long time thinking.

To Maria Adams about six o’clock that night came a troubled and disheartened man. It was no less a person than Patsy Ann’s father.

“Maria! Maria! What shall I do? Somebody don’ stole all my chillen.”

Maria, strange to say, was a woman of few words.

“Don’ you bothah ’bout de chillen,” she said, and she took him by the hand and led him to where the five lay sleeping calmly across the bed.

“Dey was runnin’ f’om home an’ dey step-mothah,” said she.

“Dey run hyeah f’om a step-mothah an’ foun’ a mothah.” It was a tribute and a proposal all in one.

When Patsy Ann awakened, the matter was explained to her, and with penitent tears she confessed her sins.

“But,” she said to Maria Adams, “ef you’s de kin’ of fo’ks dat dey mek step-mothahs out o’ I ain’ gwine to bothah my haid no mo’.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Interference Of Patsy Ann. Short Story

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Mels blijft even staan op de brug en kijkt uit over de Wijer. Was de beek vroeger blauwer?

Is het echt waar dat ze vroeger tot op de bodem konden kijken omdat het water zo helder was als kristal, of herinnert hij zich dat zo omdat hij alles van vroeger idealiseert? Als ze in hun bootje zaten, voeren ze op een kleine rivier van stromend glas.

Is het echt waar dat ze vroeger tot op de bodem konden kijken omdat het water zo helder was als kristal, of herinnert hij zich dat zo omdat hij alles van vroeger idealiseert? Als ze in hun bootje zaten, voeren ze op een kleine rivier van stromend glas.

Het blauw dat hij in zijn geheugen heeft, was onzegbaar blauw. Het diepste blauw.

Hij sluit zijn ogen om zich dat blauw van de Wijer voor de geest te halen. De blauwe zomerkleur van het stromende water. Het blauw van de libellen. Het geel van de lisdodden. De spekwitte huid van de waterlelies.

Zonder nog op te kijken draait hij zijn rolstoel en rijdt naar huis.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (098)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Ein elsässischer Soldat im Ersten Weltkrieg entdeckt am Nachthimmel das Sternbild des Großen Burschen, das so schauderhaft ist, dass er niemandem davon erzählen kann.

Ein junger Mann, der sich in die blinde Anja verliebt hat, muss feststellen, dass ihr Apartment von oben bis unten mit Beschimpfungen bekritzelt ist. Marcel, sechzehn Jahre alt, hinterlässt auf der Toilettenwand eines Erotiklokals seine Handynummer und den Namen Suzy.

Ein junger Mann, der sich in die blinde Anja verliebt hat, muss feststellen, dass ihr Apartment von oben bis unten mit Beschimpfungen bekritzelt ist. Marcel, sechzehn Jahre alt, hinterlässt auf der Toilettenwand eines Erotiklokals seine Handynummer und den Namen Suzy.

Familie Scheuch bekommt eines Tages Besuch von einem Herrn Ulrichsdorfer, der vorgibt, in ihrem Haus aufgewachsen zu sein, und einen Elektroschocker unter seinem geliehenen Anzugjackett verbirgt.

Das ganz und gar Unerwartete bricht in das Leben von Clemens J. Setz’ Figuren ein. Ihr Schöpfer erzählt davon einfühlsam, fast zärtlich. Durch Falltüren gestattet er uns Blicke auf rätselhafte Erscheinungen und in geheimnisvolle Abgründe des Alltags, man stößt auf Wiedergänger und auf Sätze, die einen mit der Zunge schnalzen lassen.

Der Trost runder Dinge ist ein Buch voller Irrlichter und doppelter Böden – radikal erzählt und aufregend bis ins Detail.

Clemens J. Setz wurde 1982 in Graz geboren, wo er Mathematik sowie Germanistik studierte und heute als Übersetzer und freier Schriftsteller lebt. 2011 wurde er für seinen Erzählband Die Liebe zur Zeit des Mahlstädter Kindes mit dem Preis der Leipziger Buchmesse ausgezeichnet. Sein Roman Indigo stand auf der Shortlist des Deutschen Buchpreises 2012 und wurde mit dem Literaturpreis des Kulturkreises der deutschen Wirtschaft 2013 ausgezeichnet. 2014 erschien sein erster Gedichtband Die Vogelstraußtrompete. Für seinen Roman Die Stunde zwischen Frau und Gitarre erhielt Setz den Wilhelm Raabe-Literaturpreis 2015.

Clemens J. Setz

Der Trost runder Dinge

Erzählungen

Erschienen: 11.02.2019

Gebunden

320 Seiten

ISBN: 978-3-518-42852-8

Suhrkamp Verlag AG

Mit Abbildungen

€ 24,00

# new books

Der Trost runder Dinge

Erzählungen

Clemens J. Setz

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, WAR & PEACE

`Zullen we doen wie het eerst bij de kerk is?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Goed’, zegt Mels. `Maar ik wil twintig meter voorsprong. Mijn fiets is niet zo goed als die van jou.’

`Jij mag mijn fiets.’

`Jij mag mijn fiets.’

`Dan starten we gelijk.’

`Jullie wachten maar op me bij de kerk’, zegt Thija.

`Ik tel tot drie’, roept Tijger.

Bij `drie’ vliegen ze ervandoor. De betere fiets helpt Mels niet. Tijger gaat op kop. Maar Mels geeft zich nog niet gewonnen.

Ze naderen het dorp. In volle vaart schiet Tijger van het pad, zoeft rakelings langs de Wijer en vindt het pad terug. Bijna had Mels hem ingehaald.

De kerk is al dichtbij. Het pad wordt breder. Op het laatste stuk van het pad, vanaf het kerkhof tot de kerk, ligt grind. Daar kunnen ze nog harder.

Tijger zoeft de straat op. Een paar tellen later gevolgd door Mels.

Hij hoort een klap. Roepen. Schelden.

Tijger ligt bewegingloos op straat. De fiets ligt verwrongen onder het wiel van de tractor. Mensen schieten te hulp. Vrouwen met handdoeken en verband. Mannen stropen in paniek hun mouwen op.

De boer probeert de fiets onder het tractorwiel vandaan te trekken.

Mels wil naar zijn vriend, maar de mensen duwen hem aan de kant. Hij ziet hoe een straaltje bloed uit het oor van Tijger loopt.

Thija slaat een arm om Mels heen. Hij ziet haar grote ogen waar de tranen uit stromen.

`Hij is dood’, horen ze de man zeggen die zijn oor aan Tijgers borst houdt.

`Hij is dood’, zegt de man tegen Tijgers moeder.

`Hij is dood’, fluistert Mels.

Thija’s tranen vloeien langs haar hals en vormen een donkere vlek op haar lichtgroene blouse.

Een politieman stuurt alle kinderen weg. Het helpt niet als ze zeggen dat Tijger hun vriend is.

`Jullie moeten weg’, zegt de agent. `En hij heet geen Tijger. Hij heet Bart.’

Ze gaan op de bank voor de kerk zitten en zien hoe een ambulance voorrijdt, hoe Tijger op een brancard wordt gelegd en hoe hij het dorp uit wordt gereden.

De moeder van Mels komt naar hem en Thija toe, gaat bij hen zitten en legt een arm om hen heen. Samen zitten ze op de bank, totdat het donker wordt. En dan blijven ze ook nog zitten, omdat ze weer moeten huilen als ze steeds opnieuw het ijselijke gillen van Tijgers moeder horen. De dokter is bij haar, en de pastoor, maar geen pillen en geen gebeden krijgen haar stil.

Dan komt ook de moeder van Thija bij hen zitten. Zo zitten ze daar uren, in het almaar killer wordende maanlicht. En opeens begint Thija’s moeder te vertellen in haar wonderlijke taal die een mengeling is van Engels, Nederlands, Chinees en gebarentaal. Haar woorden verdoven de pijn. Ze vertelt dat ze als meisje leerde zwemmen in de Jangtsekiang. Dat ze als kind met haar ouders uit China is gevlucht, en dat ze het niet erg vindt om niet in China te wonen, maar dat ze zo dolgraag dat plekje aan de Gele Rivier terug zou willen zien.

Pas als beide wijzers van de kerkklok op twaalf staan, gaan ze naar huis.

Als Thija wegloopt, ziet Mels weer hoe dun ze is. Ze is niet meer dan vel over been.

De volgende ochtend wordt er op school over Tijger gesproken. De juf vertelt verhalen over de overstap van het leven naar de dood. En dan moeten ze allemaal huilen. De juf kan zo goed vertellen dat zelfs de meisjes die een hekel hadden aan Tijger moeten huilen.

Ze maken een rouwkrans en leggen die op Tijgers bank. Daar zal hij de rest van het schooljaar blijven liggen.

Na school gaan Mels en Thija naar het molenhuis van grootvader Bernhard.

Ze klimmen naar de doodstille zolder.

`Hoe gaat het in China als kinderen doodgaan?’ vraagt Mels.

`Vraag je dat aan mij?’

`Jij was er toch? Tenminste, jouw moeder.’

`Kinderen begraven ze in glazen kisten.’

`Net als Sneeuwwitje?’

`Soms worden ze verbrand, zodat de ziel van de overledene terug kan keren in een ander lichaam.’

`Kan Tijger dat ook?’

`Hij zal wel moeten’, zegt Thija. `We kunnen niet zonder hem.’

Mels ziet dat er tranen in haar ogen staan en daarom moeten ze opeens weer allebei huilen.

`Hij moet terugkomen’, zegt Mels.

`Misschien is hij al terug.’ Thija wijst op de grote vlinder die op de ruit gaat zitten en met zijn grote gekleurde vleugels naar hen wuift.

`Zo’n grote kapel heb ik hier nog nooit gezien’, zegt Mels. `Kapellen zijn heel zeldzaam. Denk je écht dat hij het is?’

`Ik denk het wel’, zegt Thija. `In China leven de zielen van gestorven kinderen ook voort in vlinders. En dan vliegen ze wuivend door het dorp. Je ziet toch dat hij naar ons wuift! Ik vind het echt iets voor Tijger.’

Bij de begrafenis loopt Thija aan de hand van haar moeder. Mels loopt ingehaakt in de arm van zijn moeder, die zachtjes huilt, maar toch zo hard dat iedereen het hoort. Ze kan er niets aan doen.

Mels huilt niet. En ook Thija huilt niet meer. Het meer achter haar ogen is leeg. Maar haar ogen staan schuiner dan ooit, alsof ze bij de begrafenis van Tijger extra mooi wil zijn.

De kist van Tijger wordt gedragen door mannen uit de buurt.

Het hele dorp loopt van de kerk naar het kerkhof. Ook de boer die Tijger doodgereden heeft. Hij heeft een vreemd bleek voorhoofd, precies waar zijn pet gewoonlijk staat, de rest van zijn gezicht is bruingebrand door de zon. Hij houdt de pet in de hand en knijpt hem bijna fijn.

De mannen laten Tijgers kist in het graf zakken. Mels probeert naar zichzelf te luisteren, maar zo stil is het in zijn hoofd nog nooit geweest.

Thija fluistert iets. Haar mond gaat open. Ze wijst. Dan pas ziet hij de kapel met grote gekleurde vleugels die over het kerkhof vliegt en tussen de bomen verdwijnt. Tijger is voorgoed vertrokken.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (097)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

De herinnering aan de grote brand emotioneert hem. Hij merkt dat zijn hoofd gaat dazen, of er bijen in rond zoemen. Het zijn geen bijen, maar kinderstemmen. De school is uit.

`Zit je hier al lang, opa?’ Het zijn Afke en Zhia. In hun kleurige jurken hinkelen ze rond zijn rolstoel.

`Zit je hier al lang, opa?’ Het zijn Afke en Zhia. In hun kleurige jurken hinkelen ze rond zijn rolstoel.

`Ik wachtte op jullie.’

`Wat gaan we doen?’

`Naar de watermolen?’

`Goed’, zegt Afke.

`Is er feest?’

`Hoezo?’

`Omdat jullie jurken dragen. Jullie lopen altijd in broeken.’

`Straks ga ik bij haar thuis spelen’, zegt Afke. `Zhia’s oma is over. Ze is heel aardig, maar tegen meisjes in broeken praat ze niet.’

`Ik vind die jurken ook veel mooier.’ Hij meent het echt.

Als vlinders lopen ze voor hem uit.

Bij het vlondertje van het voormalige huis van grootvader Rudolf staan ze even stil. Omdat ze daar altijd even stilstaan en omdat Mels er altijd wat vertelt.

`Hier legde ik vroeger mijn boot vast’, zegt hij. `Dan liep ik naar binnen. Grootvader vertelde vaak over zijn denkbeeldige reizen, of over de oorlog. In het schuurtje had hij een klein museum.’

`Waar is dat spul gebleven?’ vraagt Afke.

`Het meeste ligt bij mij op zolder.’

`Mogen wij er gaan kijken?’

`Zeker. Het spul moet er trouwens weg. Misschien is het iets voor een echt museum.’

`En als we het zelf willen houden?’ zegt Afke. `Je kunt het aan mij geven. Ik bewaar het goed.’

`Dan mag jij alles hebben.’

De meisjes hinkelen voor hem uit. Als ze te ver voorop zijn, wachten ze op hem.

`Ik wil het weitje bij mijn grootvaders huis wel weer eens zien’, zegt Mels.

`Wij spelen daar vaak’, zegt Afke.

`Vroeger kwam er nooit iemand. Alleen wij. Tijger heeft er een kist met spullen begraven. Voor later.’

`Wat zat erin?’

`Zijn cadeaus van een verjaardagsfeestje. Ook de mondharmonica die ik hem had gegeven.’

`Die is allang verroest’, zegt Zhia. `Waarom heeft hij dat spul begraven?’

`Tijger was net een eekhoorn. Hij stopte de dingen waarvan hij hield weg.’

`Eekhoorns vergeten waar ze hun noten begraven hebben’, zegt Zhia.

`Tijger kreeg niet eens de tijd om zijn spullen terug te zoeken.’

Bij de brug slaat hij de weg in die langs de Wijer naar de molen en de parkeerplaats loopt.

`Jij rijdt hard’, roept Afke tegen hem. `Straks rij je het water in.’

`Passen júllie maar op. Er zitten duiveltjes in het water, die je met hun haakstokken de beek in trekken.’

Hij stopt omdat hij een dode kraai aan de kant ziet liggen. Verderop ligt een dode egel. Vroeger stonden hier de frambozen van zijn moeder. De dieren hadden er vrij spel, maar op het asfalt hebben ze geen kans. De vogels en dieren die vroeger te snel of te stekelig waren om ze te kunnen pakken, zijn nu te langzaam of te zacht om te ontsnappen aan de auto’s van de mensen die de molen bezoeken.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (096)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Luigi Pirandello’s extraordinary final novel begins when Vitangelo Moscarda’s wife remarks that Vitangelo’s nose tilts to the right.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

At first he only notices small differences in how he sees himself and how others do; but his self-examination quickly becomes relentless, dizzying, leading to often darkly comic results as Vitangelo decides that he must demolish that version of himself that others see.

Pirandello said of his 1926 novel that it “deals with the disintegration of the personality. It arrives at the most extreme conclusions, the farthest consequences.” Indeed, its unnerving humor and existential dissection of modern identity find counterparts in Samuel Beckett’s Molloy trilogy and the works of Thomas Bernhard and Vladimir Nabokov.

Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936) was an Italian author, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934 for his “bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage.” Pirandello’s works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and plays. Pirandello’s plays are often seen as forerunners for the theatre of the absurd.

One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

Publisher Spurl Editions

Format Paperback

218 pages

ISBN-10 194367907X

ISBN-13 9781943679072

2018

$18.00

# new books

Title One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Author Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi, Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard, Vladimir Nabokov

OLD ABE’S CONVERSION

The Negro population of the little Southern town of Danvers was in a state of excitement such as it seldom reached except at revivals, baptisms, or on Emancipation Day. The cause of the commotion was the anticipated return of the Rev. Abram Dixon’s only son, Robert, who, having taken up his father’s life-work and graduated at one of the schools, had been called to a city church.

When Robert’s ambition to take a college course first became the subject of the village gossip, some said that it was an attempt to force Providence. If Robert were called to preach, they said, he would be endowed with the power from on high, and no intervention of the schools was necessary. Abram Dixon himself had at first rather leaned to this side of the case. He had expressed his firm belief in the theory that if you opened your mouth, the Lord would fill it. As for him, he had no thought of what he should say to his people when he rose to speak. He trusted to the inspiration of the moment, and dashed blindly into speech, coherent or otherwise.

When Robert’s ambition to take a college course first became the subject of the village gossip, some said that it was an attempt to force Providence. If Robert were called to preach, they said, he would be endowed with the power from on high, and no intervention of the schools was necessary. Abram Dixon himself had at first rather leaned to this side of the case. He had expressed his firm belief in the theory that if you opened your mouth, the Lord would fill it. As for him, he had no thought of what he should say to his people when he rose to speak. He trusted to the inspiration of the moment, and dashed blindly into speech, coherent or otherwise.

Himself a plantation exhorter of the ancient type, he had known no school except the fields where he had ploughed and sowed, the woods and the overhanging sky. He had sat under no teacher except the birds and the trees and the winds of heaven. If he did not fail utterly, if his labour was not without fruit, it was because he lived close to nature, and so, near to nature’s God. With him religion was a matter of emotion, and he relied for his results more upon a command of feeling than upon an appeal to reason. So it was not strange that he should look upon his son’s determination to learn to be a preacher as unjustified by the real demands of the ministry.

But as the boy had a will of his own and his father a boundless pride in him, the day came when, despite wagging heads, Robert Dixon went away to be enrolled among the students of a growing college. Since then six years had passed. Robert had spent his school vacations in teaching; and now, for the first time, he was coming home, a full-fledged minister of the gospel.

It was rather a shock to the old man’s sensibilities that his son’s congregation should give him a vacation, and that the young minister should accept; but he consented to regard it as of the new order of things, and was glad that he was to have his boy with him again, although he murmured to himself, as he read his son’s letter through his bone-bowed spectacles: “Vacation, vacation, an’ I wonder ef he reckons de devil’s goin’ to take one at de same time?”

It was a joyous meeting between father and son. The old man held his boy off and looked at him with proud eyes.

“Why, Robbie,” he said, “you—you’s a man!”

“That’s what I’m trying to be, father.” The young man’s voice was deep, and comported well with his fine chest and broad shoulders.

“You’s a bigger man den yo’ father ever was!” said his mother admiringly.

“Oh, well, father never had the advantage of playing football.”

The father turned on him aghast. “Playin’ football!” he exclaimed. “You don’t mean to tell me dat dey ‘lowed men learnin’ to be preachers to play sich games?”

“Oh, yes, they believe in a sound mind in a sound body, and one seems to be as necessary as the other in fighting evil.”

Abram Dixon shook his head solemnly. The world was turning upside down for him.

“Football!” he muttered, as they sat down to supper.

Robert was sorry that he had spoken of the game, because he saw that it grieved his father. He had come intending to avoid rather than to combat his parent’s prejudices. There was no condescension in his thought of them and their ways. They were different; that was all. He had learned new ways. They had retained the old. Even to himself he did not say, “But my way is the better one.”

His father was very full of eager curiosity as to his son’s conduct of his church, and the son was equally glad to talk of his work, for his whole soul was in it.

“We do a good deal in the way of charity work among the churchless and almost homeless city children; and, father, it would do your heart good if you could only see the little ones gathered together learning the first principles of decent living.”

“Mebbe so,” replied the father doubtfully, “but what you doin’ in de way of teachin’ dem to die decent?”

The son hesitated for a moment, and then he answered gently, “We think that one is the companion of the other, and that the best way to prepare them for the future is to keep them clean and good in the present.”

“Do you give ’em good strong doctern, er do you give ’em milk and water?”

“I try to tell them the truth as I see it and believe it. I try to hold up before them the right and the good and the clean and beautiful.”

“Humph!” exclaimed the old man, and a look of suspicion flashed across his dusky face. “I want you to preach fer me Sunday.”

It was as if he had said, “I have no faith in your style of preaching the gospel. I am going to put you to the test.”

Robert faltered. He knew his preaching would not please his father or his people, and he shrank from the ordeal. It seemed like setting them all at defiance and attempting to enforce his ideas over their own. Then a perception of his cowardice struck him, and he threw off the feeling that was possessing him. He looked up to find his father watching him keenly, and he remembered that he had not yet answered.

“I had not thought of preaching here,” he said, “but I will relieve you if you wish it.”

“De folks will want to hyeah you an’ see what you kin do,” pursued his father tactlessly. “You know dey was a lot of ’em dat said I oughn’t ha’ let you go away to school. I hope you’ll silence ’em.”

Robert thought of the opposition his father’s friends had shown to his ambitions, and his face grew hot at the memory. He felt his entire inability to please them now.

“I don’t know, father, that I can silence those who opposed my going away or even please those who didn’t, but I shall try to please One.”

It was now Thursday evening, and he had until Saturday night to prepare his sermon. He knew Danvers, and remembered what a chill fell on its congregations, white or black, when a preacher appeared before them with a manuscript or notes. So, out of concession to their prejudices, he decided not to write his sermon, but to go through it carefully and get it well in hand. His work was often interfered with by the frequent summons to see old friends who stayed long, not talking much, but looking at him with some awe and a good deal of contempt. His trial was a little sorer than he had expected, but he bore it all with the good-natured philosophy which his school life and work in a city had taught him.

The Sunday dawned, a beautiful, Southern summer morning; the lazy hum of the bees and the scent of wild honeysuckle were in the air; the Sabbath was full of the quiet and peace of God; and yet the congregation which filled the little chapel at Danvers came with restless and turbulent hearts, and their faces said plainly: “Rob Dixon, we have not come here to listen to God’s word. We have come here to put you on trial. Do you hear? On trial.”

And the thought, “On trial,” was ringing in the young minister’s mind as he rose to speak to them. His sermon was a very quiet, practical one; a sermon that sought to bring religion before them as a matter of every-day life. It was altogether different from the torrent of speech that usually flowed from that pulpit. The people grew restless under this spiritual reserve. They wanted something to sanction, something to shout for, and here was this man talking to them as simply and quietly as if he were not in church.

As Uncle Isham Jones said, “De man never fetched an amen”; and the people resented his ineffectiveness. Even Robert’s father sat with his head bowed in his hands, broken and ashamed of his son; and when, without a flourish, the preacher sat down, after talking twenty-two minutes by the clock, a shiver of surprise ran over the whole church. His father had never pounded the desk for less than an hour.

Disappointment, even disgust, was written on every face. The singing was spiritless, and as the people filed out of church and gathered in knots about the door, the old-time head-shaking was resumed, and the comments were many and unfavourable.

“Dat’s what his schoolin’ done fo’ him,” said one.

“It wasn’t nothin’ mo’n a lecter,” was another’s criticism.

“Put him ‘side o’ his father,” said one of the Rev. Abram Dixon’s loyal members, “and bless my soul, de ol’ man would preach all roun’ him, and he ain’t been to no college, neither!”

Robert and his father walked home in silence together. When they were in the house, the old man turned to his son and said:

“Is dat de way dey teach you to preach at college?”

“I followed my instructions as nearly as possible, father.”

“Well, Lawd he’p dey preachin’, den! Why, befo’ I’d ha’ been in dat pulpit five minutes, I’d ha’ had dem people moanin’ an’ hollerin’ all over de church.”

“And would they have lived any more cleanly the next day?”

The old man looked at his son sadly, and shook his head as at one of the unenlightened.

Robert did not preach in his father’s church again before his visit came to a close; but before going he said, “I want you to promise me you’ll come up and visit me, father. I want you to see the work I am trying to do. I don’t say that my way is best or that my work is a higher work, but I do want you to see that I am in earnest.”

“I ain’t doubtin’ you mean well, Robbie,” said his father, “but I guess I’d be a good deal out o’ place up thaih.”

“No, you wouldn’t, father. You come up and see me. Promise me.”

And the old man promised.

It was not, however, until nearly a year later that the Rev. Abram Dixon went up to visit his son’s church. Robert met him at the station, and took him to the little parsonage which the young clergyman’s people had provided for him. It was a very simple place, and an aged woman served the young man as cook and caretaker; but Abram Dixon was astonished at what seemed to him both vainglory and extravagance.

“Ain’t you livin’ kin’ o’ high fo’ yo’ raisin’, Robbie?” he asked.

The young man laughed. “If you’d see how some of the people live here, father, you’d hardly say so.”

Abram looked at the chintz-covered sofa and shook his head at its luxury, but Robert, on coming back after a brief absence, found his father sound asleep upon the comfortable lounge.

On the next day they went out together to see something of the city. By the habit of years, Abram Dixon was an early riser, and his son was like him; so they were abroad somewhat before business was astir in the town. They walked through the commercial portion and down along the wharves and levees. On every side the same sight assailed their eyes: black boys of all ages and sizes, the waifs and strays of the city, lay stretched here and there on the wharves or curled on doorsills, stealing what sleep they could before the relentless day should drive them forth to beg a pittance for subsistence.

“Such as these we try to get into our flock and do something for,” said Robert.

His father looked on sympathetically, and yet hardly with full understanding. There was poverty in his own little village, yes, even squalour, but he had never seen anything just like this. At home almost everyone found some open door, and rare was the wanderer who slept out-of-doors except from choice.

At nine o’clock they went to the police court, and the old minister saw many of his race appear as prisoners, receiving brief attention and long sentences. Finally a boy was arraigned for theft. He was a little, wobegone fellow hardly ten years of age. He was charged with stealing cakes from a bakery. The judge was about to deal with him as quickly as with the others, and Abram’s heart bled for the child, when he saw a negro call the judge’s attention. He turned to find that Robert had left his side. There was a whispered consultation, and then the old preacher heard with joy, “As this is his first offence and a trustworthy person comes forward to take charge of him, sentence upon the prisoner will be suspended.”

Robert came back to his father holding the boy by the hand, and together they made their way from the crowded room.

“I’m so glad! I’m so glad!” said the old man brokenly.

“We often have to do this. We try to save them from the first contact with the prison and all that it means. There is no reformatory for black boys here, and they may not go to the institutions for the white; so for the slightest offence they are sent to jail, where they are placed with the most hardened criminals. When released they are branded forever, and their course is usually downward.”

He spoke in a low voice, that what he said might not reach the ears of the little ragamuffin who trudged by his side.

Abram looked down on the child with a sympathetic heart.

“What made you steal dem cakes?” he asked kindly.

“I was hongry,” was the simple reply.

The old man said no more until he had reached the parsonage, and then when he saw how the little fellow ate and how tenderly his son ministered to him, he murmured to himself, “Feed my lambs”; and then turning to his son, he said, “Robbie, dey’s some’p’n in ‘dis, dey’s some’p’n in it, I tell you.”

That night there was a boy’s class in the lower room of Robert Dixon’s little church. Boys of all sorts and conditions were there, and Abram listened as his son told them the old, sweet stories in the simplest possible manner and talked to them in his cheery, practical way. The old preacher looked into the eyes of the street gamins about him, and he began to wonder. Some of them were fierce, unruly-looking youngsters, inclined to meanness and rowdyism, but one and all, they seemed under the spell of their leader’s voice. At last Robert said, “Boys, this is my father. He’s a preacher, too. I want you to come up and shake hands with him.” Then they crowded round the old man readily and heartily, and when they were outside the church, he heard them pause for a moment, and then three rousing cheers rang out with the vociferated explanation, “Fo’ de minister’s pap!”

Abram held his son’s hand long that night, and looked with tear-dimmed eyes at the boy.

“I didn’t understan’,” he said. “I didn’t understan’.”

“You’ll preach for me Sunday, father?”

“I wouldn’t daih, honey. I wouldn’t daih.”

“Oh, yes, you will, pap.”

He had not used the word for a long time, and at sound of it his father yielded.

It was a strange service that Sunday morning. The son introduced the father, and the father, looking at his son, who seemed so short a time ago unlearned in the ways of the world, gave as his text, “A little child shall lead them.”

He spoke of his own conceit and vainglory, the pride of his age and experience, and then he told of the lesson he had learned. “Why, people,” he said, “I feels like a new convert!”

It was a gentler gospel than he had ever preached before, and in the congregation there were many eyes as wet as his own.

“Robbie,” he said, when the service was over, “I believe I had to come up here to be converted.” And Robbie smiled.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

Old Abe’s Conversion

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

`Wat een allemachtig mooie bliksem’, zegt Tijger vol bewondering. Het hele dorp wordt geraakt door vuurpijlen die sissend in de grond slaan.

`Onweer is sprookjesweer’, zegt Thija.

`Onweer is sprookjesweer’, zegt Thija.

Door het raampje van de zolder is het uitzicht op de wereld altijd sprookjesachtig, maar vooral nu, nu de bliksem het dorp wil afbranden en de donkere bossen aan de bovenloop van de Wijer in een witte gloed zet.

In hun bijna geluiddichte schuilplaats op de zolder van de molen horen ze het onweer nauwelijks, maar zien ze wel de bliksem wanneer die als een drietand boven het dorp staat. Hij vonkt langs de bliksemafleider van de kerk. De vlammen spatten van het beeld van Christoffel dat boven op de toren staat en die het dorp bewaakt, met op zijn schouder het kindje Jezus dat al een paar honderd jaar wacht om over de Wijer te worden gedragen.

Thija leest voor uit een van de bijbelboeken die in een doos op de zolder staan. Ze hebben er pas twee gelezen. De rest moet nog.

`Zodra Izebel, de weduwe van koning Achab van Juda, hoorde dat Jehoe, de nieuwe koning van Juda en moordenaar van haar man, haar kwam bezoeken, liet zij haar huis beschilderen, plantte bloemen in haar tuin en nodigde vrouwen in haar huis.’

`Dat zijn veel komma’s in één zin’, zegt Mels.

`Ik kan niet anders lezen dan dat wat er staat’, zegt Thija. Ze leest verder.

`Deze vrouwen waren in de hogere kringen zeer geliefd. Zij verstonden de kunst van het verleiden en maakten daar gebruik van.’

`Hoeren dus’, zegt Tijger. `Net als in de bunker.’

`Op de dag van Jehoes aankomst, verfde Izebel haar ogen zwart, haar lippen rood en haar nagels paars.’ Thija doet een vinger op haar lippen om te voorkomen dat Tijger daar weer opmerkingen over maakt. `Ze maakte haar kapsel in orde, kleedde zich in een jurk van doorschijnende zijde, sierde zich met paarlen, robijnen en blauw glanzende brokken aquamarijn. Daarna ging ze op het met bloemen gestikte kussen voor het venster zitten en wachtte af. Toen ze Jehoe zag naderen, raakte ze zeer opgewonden. “Hoe gaat het de nieuwe koning van Juda?” vroeg ze. “Hoe gaat het de moordenaar van mijn man? Het zal wel goed met hem zijn. De Heer onze God is met hem, want hij heeft het land een dienst bewezen door mijn man Achab te vermoorden.”‘

`Ze had wel lef’, zegt Tijger.

`Toen Jehoe haar hoorde, riep hij woedend tegen zijn soldaten: “Gooi dat kreng het raam uit!” De soldaten grepen Izebel en gooiden haar op de binnenplaats. Daar liet Jehoe haar door de paarden vertrappen. Haar bloed spoot tegen de muur. Wilde honden vraten haar vlees. Haar hersenen werden verzameld door een bedelaar die ermee aan de haal ging.

In de volgende dagen liet Jehoe alle zonen van Achab vermoorden. Achab had zeventig zonen, verwekt bij Izebel, slavinnen en publieke vrouwen. Hij had geen dochters, omdat Izebel nooit een dochter gebaard had. De dochters die Achab verwekt had bij slavinnen en publieke vrouwen, had hij voor de leeuwen laten werpen. Volgens de wetten van het volk waren ze een doorn in het oog van God. De zonen van Achab woonden verspreid over heel Israël, bij oude leermeesters. Ze werden door Jehoes soldaten neergestoken en ontmand. Hun hoofden werden afgehouwen en verpakt in manden naar Jehoe gezonden. Jehoe voerde de hoofden van Achabs zonen aan de wilde dieren. Zo kwam er een einde aan het geslacht van Achab.’

Verbijsterd kijken ze elkaar aan.

`Waarom staat zoiets in de bijbel?’ vraagt Tijger.

`De bijbel is een geschiedenisboek’, zegt Thija.

`Denk je dat dit echt is gebeurd?’

`Natuurlijk. De mensen leefden als beesten.’

`Net als in China?’

`Net als in China.’

`Lees nog maar een verhaal. Met dit weer kunnen we toch niet weg. Maar wel een verhaal dat minder gruwelijk is.’

Thija slaat het boek weer open, maar stokt in haar beweging als de wind de pannen rijtje voor rijtje oplicht en ze roffelend weer op hun plek laat vallen. Een paar pannen vallen kapot. De regen slaat als een waterval op de ruit. Het is echt noodweer.

De bliksem treft de kerk opnieuw. Het kind op de schouder van Christoffel staat in brand.

`Ik hoor dat Jezus “help” roept’, zegt Tijger

`Hierboven horen we niks’, zegt Mels.

`We horen Hem wel’, zegt Thija. `Hij is nog maar een kind. We horen het als Hij angst heeft. Hij roept naar ons. Jezus kan dat. God kan alles.’

`Hij staat echt in brand’, zegt Mels, nauwelijks gelovend wat hij ziet. `De toren brandt.’

Ze zien dat Christoffel wankelt en naar voren helt. Even houdt hij zich vast aan de antenne op zijn rug en draait een halve slag om zijn as. Dan valt hij samen met het kind naar beneden. Hun val wordt gebroken door uitstekende draden en haken, dan tuimelen ze in de afgrond tussen de daken van het dorp.

`Jezus komt thuis bij Zijn Vader op het altaar’, zegt Thija bleek. Ze glijdt van de stapel meelzakken af, knielt neer, haar hoofd gebogen en bidt.

De jongens houden hun adem in. Mels weet dat dit een moment is waarop de wereld kan blijven stilstaan.

Op zolder is het nog stiller dan het al was. Verbijsterd kijken ze naar de vlammen die uit de toren slaan en over het dak van de kerk dansen. In een paar tellen zetten ze het hele gebouw in lichterlaaie.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (095)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Hij rijdt de winkel in, rechtdoor naar de bloemenhoek die nu op de plek zit waar vroeger de keuken van juffrouw Fijnhout was.

Al een paar dagen na de begrafenis van juffrouw Fijnhout betrok nicht Jozefien, met man en kinderen, het huis.

Al een paar dagen na de begrafenis van juffrouw Fijnhout betrok nicht Jozefien, met man en kinderen, het huis.

Haar man begon direct met het uitbreiden van de winkel. Hij verkocht ook verf en behang, kalk en wasbenzine. En hij had een drukpersje voor geboortekaartjes. En wie geboortekaartjes kocht, kocht ook bloemen. Daarom stond een hoek van de winkel altijd vol kleurige bloemen voor geboortefeesten en een andere hoek vol witte ruikers voor bruiloften en begrafenissen.

Nicht Jozefien vlocht ook grafkransen. Ze had wel wat van haar overleden tante. Voor alles kon men bij haar terecht.

In de loop der jaren is de winkel uitgebreid. Mels komt er nog graag. De geuren van de bloemen doen hem goed. En de kleuren. Hij hoort het druppelen van de fonteintjes. Overal staan ze. Het is mode. Fonteintjes van aardewerk, van hard, gekleurd plastic, van glas. En veel spiegels die het wereldje van de winkel uitvergroten tot een ware tuin. Door al die spiegels lijken er meer meisjes in de winkel te zijn, maar er is alleen Christine, de kleindochter van nicht Jozefien.

`Geef die witte aronskelken maar’, zegt Mels. Hij is een beetje gek op haar, door de manier waarop ze alles doet, bedachtzaam en vanzelfsprekend. Ze weet precies wat mooi is. Een prinses in een koninklijke tuin. Ze is altijd vriendelijk.

`Jammer dat het kerkhof weggaat, hè’, zegt Christine, terwijl ze bezig is met een bloemstuk voor een begrafenis. Ze lijkt als twee druppels water op haar grootmoeder Jozefien. Ze is al de vijfde generatie in de winkel.

`Ik kom er zelf niet meer te liggen’, zegt Mels. `Ik dacht bij mijn vriend Tijger begraven te worden, maar als het zover is, brengen ze me naar een plek waar ik nu al niet meer op eigen kracht kan komen.’

`Hoelang is uw vriend al dood?’

`Al bijna vijftig jaar. Hem laten ze gewoon liggen. De huizen worden gewoon op de resterende graven gebouwd.’

`Ik zou daar niet willen wonen.’

`Tijger kan er wel om lachen’, zegt Mels.

Christine pakt de aronskelken in en legt ze op zijn schoot. Ze zijn wit en ruiken naar vanille.

Hij ziet zichzelf in de spiegel naast de kassa. Vanaf zijn borst. De bloemen op zijn schoot verbergen zijn onderlijf. Hij ziet er goed uit, met die bloemen op schoot. Bloemen houden van hem. Ze maken hem mooier. Daarom geeft hij ze aan Tijger. Hij weet nog wat zijn moeder zei: je moet altijd de dingen geven waarvan je het meest houdt.

Mels betaalt. De kassa rinkelt. Het is een geluid dat in een winkel hoort.

`Ik voel me hier nog steeds net zo thuis als toen het de kleine winkel van juffrouw Fijnhout was.’

`Juffrouw Fijnhout?’

`De oudtante van je grootmoeder.’

`O, die. Ze had geen kinderen, hè?’

`Jouw grootmoeder leek ook op haar. Net als jouw moeder op haar lijkt. En jij op allemaal.’

`Was ze knap?’

`Wil je weten of jij knap bent?’

`Zeg maar niets’, lacht ze.

`Ja, ze was knap. Maar dat besefte ik later pas. Een kind ziet zoiets niet. Maar ik kwam graag bij haar. Dat is wat telt. Of jij knap bent, laat ik over aan de jongemannen.’

`Bonnetje?’

`Welnee’, zegt hij, overmoedig door de bloemen op zijn schoot. `Geef mij maar een kus.’

Ze kijkt hem lachend aan en geeft hem dan een kus op zijn wang.

`Ik hoop dat er ook nog iemand aan mij denkt als ík al vijftig jaar dood ben’, zegt ze.

`Vast wel’, lacht Mels. `Ik gun je veel kleinkinderen.’

Hij rijdt de winkel uit en kijkt nog een keer om. Hij ziet Christine in drie spiegels tegelijk. Van voor en van achter en van opzij. Alle Christines zijn even mooi.

Hij rijdt door naar het kerkhof en stopt bij het graf van grootvader Rudolf. Hij haalt een bloem uit het boeket en legt die bij het kruis waaronder grootvader Rudolf is begraven, boven op zijn veel eerder gestorven vrouw.

`Rudolphus Johannes Cremers’, leest hij hardop. `Voormalig hoofd der school.’ En daarboven staat: `Katelijne Melanie Jansen’, `huisvrouw’. De kruisjes geven aan dat grootmoeder Katelijne in 1944 is overleden en grootvader Rudolf in 1978. Hij is, geboren in 1882, bijna honderd geworden. Grootmoeder Katelijne is geboren in 1906. Ze was dus achttien jaar jonger en pas achtendertig toen ze stierf. Van horen zeggen weet hij dat ze pianospeelde op familiefeestjes.

Wat doen ze nu met hen? Wordt grootvader naar het nieuwe kerkhof verhuisd en blijft grootmoeder hier achter omdat ze hier al meer dan veertig jaar ligt?

Op elk graf van een familielid legt hij een bloem.

Hij rijdt een rondje. Een deel van de graven is al weg. Door al die lege plekken, ziet het er rommelig uit.

Het graf van Tijger ligt tussen de kindergraven. De meeste opschriften op de kinderkruisen zijn onleesbaar geworden. Ook dat van Tijger is afgebladderd. Van zijn voornaam is alleen een a over, maar het kan ook een o zijn. Hij is een vergeten kind. Wie geen nageslacht heeft, houdt op te bestaan.

Hij legt de bloemen op het graf.

`Dank je.’ Het is de stem van Tijger. Elke keer als hij bloemen op het graf legt, hoort hij hem. Het kan natuurlijk niet, maar toch.

Hij klopt het stuifmeel van zijn jas.

In de eerste maanden na zijn dood brachten Thija en hij vaak boeketten naar het graf. Bloemen die ze langs de Wijer hadden geplukt. Distels, lelies, judaspenningen, alles wat er in het wild groeide.

Vroeger, met de schoolklas, hebben ze vaak het kerkhof geharkt, het onkruid gewied, het mos van de stenen gekrast. Er was hun respect bijgebracht voor het kerkhof. De plek van de voorouders, die altijd zo hoorde te blijven.

Het graf van vliegenier John Wilkington, dat altijd door Mels’ moeder werd onderhouden, is allang weg. Het houten kruis, waarvan de verf verdwenen is, staat in een hoekje van het kerkhof te wachten op mensen die zich het lot van John Wilkington willen aantrekken en de geschiedenis aan hem levend willen houden, maar Mels is een van de weinigen die nog weten wie John Wilkington was. En hij is niet meer in staat het kruis op te knappen om John de eer te geven die hem toekomt.

Bij de poort van het kerkhof staat het beeld van Christoffel met Jezus op zijn schouder. Half tussen de struiken. Langgeleden is het bij de grote kerkbrand van de toren gevallen. Christoffel is een deel van zijn hoofd kwijtgeraakt en mist ook zijn voeten. Jezus heeft de arm verloren die hij om Christoffels schouder had geslagen. Na de restauratie van de kerk is het beeld niet teruggeplaatst op de toren maar vervangen door een haan. Het gehavende beeld is in de tuin gezet en vergeten. Het is een verkeerde plek. Christoffel met op zijn schouder het kind dat over het water wil worden gedragen, had langs de Wijer moeten staan.

De brand van de kerk was de grootste ramp die het dorp ooit getroffen had.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (094)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Als Mels door de achterdeur binnenkomt hoort hij het direct: het is te stil.

Op zijn tenen loopt hij naar de keuken. Juffrouw Fijnhout zit aan tafel, met haar hoofd op haar armen.

Het is zes uur, tijd om de klok op te winden. Is ze het vergeten? Is ze er te moe voor?

Hij gaat tegenover haar zitten en kijkt naar haar witte haar. De ene helft van haar gezicht. Haar ogen zijn dicht.

Hij gaat tegenover haar zitten en kijkt naar haar witte haar. De ene helft van haar gezicht. Haar ogen zijn dicht.

Nu pas valt hem de vreemde lucht op. Hij ziet het plasje onder haar stoel.

Kalm gaat hij naar huis.

`Er is iets met juffrouw Fijnhout’, zegt hij tegen zijn moeder.

`Ze is dood’, zegt ze. `Dat zie ik aan je gezicht.’ Ze slaat een kruis. `Dat de Here zich over haar moge ontfermen. Ze heeft een mooie plek in de hemel verdiend. Amen.’

`Ze hield van haar winkel. Denk jij dat ze in de hemel een winkeltje begint?’

`Maar of ze daar ook Hohner-muziekinstrumenten hebben? Haal je tante. We moeten juffrouw Fijnhout gaan verzorgen. En waarschuw de dokter. Ze is niet dood voordat hij het zegt.’

Mels rent naar zijn tante en brengt haar het nieuws. Nog geen vijf minuten later weet iedereen in de buurt over de dood van juffrouw Fijnhout, die zonder veel pijn is overleden. De mensen zijn tevreden. Ze heeft een zachte dood verdiend.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (093)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature