Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

`Ken jij dat verhaal nog, over die koopman?’ vraagt Mels. `Het verhaal dat de juf voorlas?’

`Ik ken het nog’, zegt Tijger. `Het verhaal van de man in het zwart, die als een koopman langs de huizen ging. Als de mensen aan de deuren kwamen, lichtte hij zijn hoed, zodat ze de horentjes op zijn hoofd zagen.

`Ik ken het nog’, zegt Tijger. `Het verhaal van de man in het zwart, die als een koopman langs de huizen ging. Als de mensen aan de deuren kwamen, lichtte hij zijn hoed, zodat ze de horentjes op zijn hoofd zagen.

Niemand durfde de duivel te weigeren iets van hem te kopen. Maar wat hij te koop aanbood, maakte hen bang. Het waren lege zakken, lege dozen en holle vaten met niks erin. Voor veel geld had je niks gekocht. De duivel verkocht alleen maar lucht. Daar betaalden de mensen voor, uit angst door hem te worden meegenomen. De duivel was de patroon van de kooplui, hun leermeester en hun voorbeeld.’

`Precies, zo ging dat verhaal’, zegt Mels. `Vroeger kende ik het vanbuiten.’

`Daarin was jij beter’, geeft Tijger toe. `Je had een open oor voor verhalen. Maar met sporten was ik beter. Ik heb vaak van je gewonnen.’

`Je kon niet tegen je verlies. Erger was dat je altijd beloond wilde worden. Mijn zakmes, mijn vulpen, jij pikte het allemaal in.’

`Kleine dingen maar. Weet je nog dat we onder de brug door voeren en Lizet op de brug stond. Weet je dat ik je bij de volgende overwinning de kousenband van Lizet had willen vragen?’

`Daar was ik nooit op ingegaan’, zegt Mels een beetje driftig. `Ik kon Lizet niet uitstaan.’

`Je kon je ogen niet van haar afhouden.’

`Hou op.’

`Ik vind het niet gek dat je met haar getrouwd bent.’

`En Thija?’

`Nu denk ik dat het ook een wedstrijd was.’

`Voor jou?’

`Ja, zeker voor mij.’

`En jij zou hebben gewonnen?’

`Ik won toch altijd alles?’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (106)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

`Knikkeren?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Knikkeren?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Heb je penningen?’

`Twee. Ik zet. Jij gooit.’

Tijger gaat op zijn kont zitten, de benen uit elkaar, de penning, met de beeltenis van de Duitse keizer, staat op zijn rand. Mels probeert hem te raken, maar alle knikkers gaan er langs. Ze rollen Tijgers broekspijpen in.

De schoolbel maakt een einde aan het spel. Fluisterend lopen ze door de gang naar het natuurkundelokaal. Binnen ruikt het naar krijt en naar de meisjes die in het uur daarvoor les hebben gehad. Meisjes krijgen altijd apart natuurkundeles, omdat ze iets moeten leren wat jongens niet mogen weten.

Juf Elsbeth zet de fles kikkervisjes op haar lessenaar en begint te praten over het wonder van de schepping. Haar stem zakt weg in het geluid van motoren buiten. De ruiten van de klas trillen van het zware gebrom van de vrachtwagens die door de slurf van de silo worden leeggezogen. Een man staat op het dak van de silo en draait met een handel de slurf hoger op. Hij schreeuwt tegen de stem van de juffrouw in. `Joehoe, joehoe!’ Niemand lijkt hem te horen. Een van de ruiten van het klaslokaal protesteert tegen het lawaai op deze zonnige middag, waarop het rustig hoort te zijn, en springt met een knal in tweeën. Splinters spatten over de leerlingen, als kleine stukjes ijs.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (105)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

THE PROMOTER

Even as early as September, in the year of 1870, the newly emancipated had awakened to the perception of the commercial advantages of freedom, and had begun to lay snares to catch the fleet and elusive dollar.

Those co ntroversialists who say that the Negro’s only idea of freedom was to live without work are either wrong, malicious, or they did not know Little Africa when the boom was on; when every little African, fresh from the fields and cabins, dreamed only of untold wealth and of mansions in which he would have been thoroughly uncomfortable.

ntroversialists who say that the Negro’s only idea of freedom was to live without work are either wrong, malicious, or they did not know Little Africa when the boom was on; when every little African, fresh from the fields and cabins, dreamed only of untold wealth and of mansions in which he would have been thoroughly uncomfortable.

These were the devil’s sunny days, and early and late his mowers were in the field. These were the days of benefit societies that only benefited the shrewdest man; of mutual insurance associations, of wild building companies, and of gilt-edged land schemes wherein the unwary became bogged. This also was the day of Mr. Jason Buford, who, having been free before the war, knew a thing or two, and now had set himself up as a promoter. Truly he had profited by the example of the white men for whom he had so long acted as messenger and factotum.

As he frequently remarked when for purposes of business he wished to air his Biblical knowledge, “I jest takes the Scripter fur my motter an’ foller that ol’ passage where it says, ‘Make hay while the sun shines, fur the night cometh when no man kin work.'”

It is related that one of Mr. Buford’s customers was an old plantation exhorter. At the first suggestion of a Biblical quotation the old gentleman closed his eyes and got ready with his best amen. But as the import of the words dawned on him he opened his eyes in surprise, and the amen died a-borning. “But do hit say dat?” he asked earnestly.

“It certainly does read that way,” said the promoter glibly.

“Uh, huh,” replied the old man, settling himself back in his chair. “I been preachin’ dat t’ing wrong fu’ mo’ dan fo’ty yeahs. Dat’s whut comes o’ not bein’ able to read de wo’d fu’ yo’se’f.”

Buford had no sense of the pathetic or he could never have done what he did—sell to the old gentleman, on the strength of the knowledge he had imparted to him, a house and lot upon terms so easy that he might drowse along for a little time and then wake to find himself both homeless and penniless. This was the promoter’s method, and for so long a time had it proved successful that he had now grown mildly affluent and had set up a buggy in which to drive about and see his numerous purchasers and tenants.

Buford was a suave little yellow fellow, with a manner that suggested the training of some old Southern butler father, or at least, an experience as a likely house-boy. He was polite, plausible, and more than all, resourceful. All of this he had been for years, but in all these years he had never so risen to the height of his own uniqueness as when he conceived and carried into execution the idea of the “Buford Colonizing Company.”

Humanity has always been looking for an Eldorado, and, however mixed the metaphor may be, has been searching for a Moses to lead it thereto. Behold, then, Jason Buford in the rôle of Moses. And equipped he was to carry off his part with the very best advantage, for though he might not bring water from the rock, he could come as near as any other man to getting blood from a turnip.

The beauty of the man’s scheme was that no offering was too small to be accepted. Indeed, all was fish that came to his net.

Think of paying fifty cents down and knowing that some time in the dim future you would be the owner of property in the very heart of a great city where people would rush to buy. It was glowing enough to attract a people more worldly wise than were these late slaves. They simply fell into the scheme with all their souls; and off their half dollars, dollars, and larger sums, Mr. Buford waxed opulent. The land meanwhile did not materialise.

It was just at this time that Sister Jane Callender came upon the scene and made glad the heart of the new-fledged Moses. He had heard of Sister Jane before, and he had greeted her coming with a sparkling of eyes and a rubbing of hands that betokened a joy with a good financial basis.

The truth about the newcomer was that she had just about received her pension, or that due to her deceased husband, and she would therefore be rich, rich to the point where avarice would lie in wait for her.

Sis’ Jane settled in Mr. Buford’s bailiwick, joined the church he attended, and seemed only waiting with her dollars for the very call which he was destined to make. She was hardly settled in a little three-room cottage before he hastened to her side, kindly intent, or its counterfeit, beaming from his features. He found a weak-looking old lady propped in a great chair, while another stout and healthy-looking woman ministered to her wants or stewed about the house in order to be doing something.

“Ah, which—which is Sis’ Jane Callender,” he asked, rubbing his hands for all the world like a clothing dealer over a good customer.

“Dat’s Sis’ Jane in de cheer,” said the animated one, pointing to her charge. “She feelin’ mighty po’ly dis evenin’. What might be yo’ name?” She was promptly told.

“Sis’ Jane, hyeah one de good brothahs come to see you to offah his suvices if you need anything.”

“Thanky, brothah, charity,” said the weak voice, “sit yo’se’f down. You set down, Aunt Dicey. Tain’t no use a runnin’ roun’ waitin’ on me. I ain’t long fu’ dis worl’ nohow, mistah.”

“Buford is my name an’ I came in to see if I could be of any assistance to you, a-fixin’ up yo’ mattahs er seein’ to anything for you.”

“Hit’s mighty kind o’ you to come, dough I don’ ‘low I’ll need much fixin’ fu’ now.”

“Oh, we hope you’ll soon be better, Sistah Callender.”

“Nevah no mo’, suh, ’til I reach the Kingdom.”

“Sis’ Jane Callender, she have been mighty sick,” broke in Aunt Dicey Fairfax, “but I reckon she gwine pull thoo’, the Lawd willin’.”

“Amen,” said Mr. Buford.

“Huh, uh, children, I done hyeahd de washin’ of de waters of Jerdon.”

“No, no, Sistah Callendah, we hope to see you well and happy in de injoyment of de pension dat I understan’ de gov’ment is goin’ to give you.”

“La, chile, I reckon de white folks gwine to git dat money. I ain’t nevah gwine to live to ‘ceive it. Des’ aftah I been wo’kin’ so long fu’ it, too.”

The small eyes of Mr. Buford glittered with anxiety and avarice. What, was this rich plum about to slip from his grasp, just as he was about to pluck it? It should not be. He leaned over the old lady with intense eagerness in his gaze.

“You must live to receive it,” he said, “we need that money for the race. It must not go back to the white folks. Ain’t you got nobody to leave it to?”

“Not a chick ner a chile, ‘ceptin’ Sis’ Dicey Fairfax here.”

Mr. Buford breathed again. “Then leave it to her, by all means,” he said.

“I don’ want to have nothin’ to do with de money of de daid,” said Sis’ Dicey Fairfax.

“Now, don’t talk dat away, Sis’ Dicey,” said the sick woman. “Brother Buford is right, case you sut’ny has been good to me sence I been layin’ hyeah on de bed of affliction, an’ dey ain’t nobody more fitterner to have dat money den you is. Ef de Lawd des lets me live long enough, I’s gwine to mek my will in yo’ favoh.”

“De Lawd’s will be done,” replied the other with resignation, and Mr. Buford echoed with an “Amen!”

He stayed very long that evening, planning and talking with the two old women, who received his words as the Gospel. Two weeks later the Ethiopian Banner, which was the organ of Little Africa, announced that Sis’ Jane Callender had received a back pension which amounted to more than five hundred dollars. Thereafter Mr. Buford was seen frequently in the little cottage, until one day, after a lapse of three or four weeks, a policeman entered Sis’ Jane Callender’s cottage and led her away amidst great excitement to prison. She was charged with pension fraud, and against her protestations, was locked up to await the action of the Grand Jury.

The promoter was very active in his client’s behalf, but in spite of all his efforts she was indicted and came up for trial.

It was a great day for the denizens of Little Africa, and they crowded the court room to look upon this stranger who had come among them to grow so rich, and then suddenly to fall so low.

The prosecuting attorney was a young Southerner, and when he saw the prisoner at the bar he started violently, but checked himself. When the prisoner saw him, however, she made no effort at self control.

“Lawd o’ mussy,” she cried, spreading out her black arms, “if it ain’t Miss Lou’s little Bobby.”

The judge checked the hilarity of the audience; the prosecutor maintained his dignity by main force, and the bailiff succeeded in keeping the old lady in her place, although she admonished him: “Pshaw, chile, you needn’t fool wid me, I nussed dat boy’s mammy when she borned him.”

It was too much for the young attorney, and he would have been less a man if it had not been. He came over and shook her hand warmly, and this time no one laughed.

It was really not worth while prolonging the case, and the prosecution was nervous. The way that old black woman took the court and its officers into her bosom was enough to disconcert any ordinary tribunal. She patronised the judge openly before the hearing began and insisted upon holding a gentle motherly conversation with the foreman of the jury.

She was called to the stand as the very first witness.

“What is your name?” asked the attorney.

“Now, Bobby, what is you axin’ me dat fu’? You know what my name is, and you one of de Fairfax fambly, too. I ‘low ef yo’ mammy was hyeah, she’d mek you ‘membah; she’d put you in yo’ place.”

The judge rapped for order.

“That is just a manner of proceeding,” he said; “you must answer the question, so the rest of the court may know.”

“Oh, yes, suh, ‘scuse me, my name hit’s Dicey Fairfax.”

The attorney for the defence threw up his hands and turned purple. He had a dozen witnesses there to prove that they had known the woman as Jane Callender.

“But did you not give your name as Jane Callender?”

“I object,” thundered the defence.

“Do, hush, man,” Sis’ Dicey exclaimed, and then turning to the prosecutor, “La, honey, you know Jane Callender ain’t my real name, you knows dat yo’se’f. It’s des my bus’ness name. W’y, Sis’ Jane Callender done daid an’ gone to glory too long ‘go fu’ to talk erbout.”

“Then you admit to the court that your name is not Jane Callender?”

“Wha’s de use o’ my ‘mittin’, don’ you know it yo’se’f, suh? Has I got to come hyeah at dis late day an’ p’ove my name an’ redentify befo’ my ol’ Miss’s own chile? Mas’ Bob, I nevah did t’ink you’d ac’ dat away. Freedom sutny has done tuk erway yo’ mannahs.”

“Yes, yes, yes, that’s all right, but we want to establish the fact that your name is Dicey Fairfax.”

“Cose it is.”

“Your Honor, I object—I——”

“Your Honor,” said Fairfax coldly, “will you grant me the liberty of conducting the examination in a way somewhat out of the ordinary lines? I believe that my brother for the defence will have nothing to complain of. I believe that I understand the situation and shall be able to get the truth more easily by employing methods that are not altogether technical.”

The court seemed to understand a thing or two himself, and overruled the defence’s objection.

“Now, Mrs. Fairfax——”

Aunt Dicey snorted. “Hoomph? What? Mis’ Fairfax? What ou say, Bobby Fairfax? What you call me dat fu’? My name Aunt Dicey to you an’ I want you to un’erstan’ dat right hyeah. Ef you keep on foolin’ wid me, I ‘spec’ my patience gwine waih claih out.”

“Excuse me. Well, Aunt Dicey, why did you take the name of Jane Callender if your name is really Dicey Fairfax?”

“W’y, I done tol’ you, Bobby, dat Sis’ Jane Callender was des’ my bus’ness name.”

“Well, how were you to use this business name?”

“Well, it was des dis away. Sis’ Jane Callender, she gwine git huh pension, but la, chile, she tuk down sick unto deaf, an’ Brothah Buford, he say dat she ought to mek a will in favoh of somebody, so’s de money would stay ‘mongst ouah folks, an’ so, bimeby, she ‘greed she mek a will.”

“And who is Brother Buford, Aunt Dicey?”

“Brothah Buford? Oh, he’s de gemman whut come an’ offered to ‘ten’ to Sis’ Jane Callender’s bus’ness fu’ huh. He’s a moughty clevah man.”

“And he told her she ought to make a will?”

“Yas, suh. So she ‘greed she gwine mek a will, an’ she say to me, ‘Sis Dicey, you sut’ny has been good to me sence I been layin’ hyeah on dis bed of ‘fliction, an’ I gwine will all my proputy to you.’ Well, I don’t want to tek de money, an’ she des mos’ nigh fo’ce it on me, so I say yes, an’ Brothah Buford he des sot an’ talk to us, an’ he say dat he come to-morror to bring a lawyer to draw up de will. But bless Gawd, honey, Sis’ Callender died dat night, an’ de will wasn’t made, so when Brothah Buford come bright an’ early next mornin’, I was layin’ Sis’ Callender out. Brothah Buford was mighty much moved, he was. I nevah did see a strange pusson tek anything so hard in all my life, an’ den he talk to me, an’ he say, ‘Now, Sis’ Dicey, is you notified any de neighbours yit?’ an’ I said no I hain’t notified no one of de neighbours, case I ain’t ‘quainted wid none o’ dem yit, an’ he say, ‘How erbout de doctah? Is he ‘quainted wid de diseased?’ an’ I tol’ him no, he des come in, da’s all. ‘Well,’ he say, ‘cose you un’erstan’ now dat you is Sis’ Jane Callender, caise you inhe’it huh name, an’ when de doctah come to mek out de ‘stiffycate, you mus’ tell him dat Sis’ Dicey Fairfax is de name of de diseased, an’ it’ll be all right, an’ aftah dis you got to go by de name o’ Jane Callender, caise it’s a bus’ness name you done inhe’it.’ Well, dat’s whut I done, an’ dat’s huccome I been Jane Callender in de bus’ness ‘sactions, an’ Dicey Fairfax at home. Now, you un’erstan’, don’t you? It wuz my inhe’ited name.”

“But don’t you know that what you have done is a penitentiary offence?”

“Who you stan’in’ up talkin’ to dat erway, you nasty impident little scoun’el? Don’t you talk to me dat erway. I reckon ef yo’ mammy was hyeah she sut’ny would tend to yo’ case. You alluse was sassier an’ pearter den yo’ brother Nelse, an’ he had to go an’ git killed in de wah, an’ you—you—w’y, jedge, I’se spanked dat boy mo’ times den I kin tell you fu’ hus impidence. I don’t see how you evah gits erlong wid him.”

The court repressed a ripple that ran around. But there was no smile on the smooth-shaven, clear-cut face of the young Southerner. Turning to the attorney for the defence, he said: “Will you take the witness?” But that gentleman, waving one helpless hand, shook his head.

“That will do, then,” said young Fairfax. “Your Honor,” he went on, addressing the court, “I have no desire to prosecute this case further. You all see the trend of it just as I see, and it would be folly to continue the examination of any of the rest of these witnesses. We have got that story from Aunt Dicey herself as straight as an arrow from a bow. While technically she is guilty; while according to the facts she is a criminal according to the motive and the intent of her actions, she is as innocent as the whitest soul among us.” He could not repress the youthful Southerner’s love for this little bit of rhetoric.

“And I believe that nothing is to be gained by going further into the matter, save for the purpose of finding out the whereabouts of this Brother Buford, and attending to his case as the facts warrant. But before we do this, I want to see the stamp of crime wiped away from the name of my Aunt Dicey there, and I beg leave of the court to enter a nolle prosse. There is only one other thing I must ask of Aunt Dicey, and that is that she return the money that was illegally gotten, and give us information concerning the whereabouts of Buford.”

Aunt Dicey looked up in excitement, “W’y, chile, ef dat money was got illegal, I don’ want it, but I do know whut I gwine to do, cause I done ‘vested it all wid Brothah Buford in his colorednization comp’ny.” The court drew its breath. It had been expecting some such dénouement.

“And where is the office of this company situated?”

“Well, I des can’t tell dat,” said the old lady. “W’y, la, man, Brothah Buford was in co’t to-day. Whaih is he? Brothah Buford, whaih you?” But no answer came from the surrounding spectators. Brother Buford had faded away. The old lady, however, after due conventions, was permitted to go home.

It was with joy in her heart that Aunt Dicey Fairfax went back to her little cottage after her dismissal, but her face clouded when soon after Robert Fairfax came in.

“Hyeah you come as usual,” she said with well-feigned anger. “Tryin’ to sof’ soap me aftah you been carryin’ on. You ain’t changed one mite fu’ all yo’ bein’ a man. What you talk to me dat away in co’t fu’?”

Fairfax’s face was very grave. “It was necessary, Aunt Dicey,” he said. “You know I’m a lawyer now, and there are certain things that lawyers have to do whether they like it or not. You don’t understand. That man Buford is a scoundrel, and he came very near leading you into a very dangerous and criminal act. I am glad I was near to save you.”

“Oh, honey, chile, I didn’t know dat. Set down an’ tell me all erbout it.”

This the attorney did, and the old lady’s indignation blazed forth. “Well, I hope to de Lawd you’ll fin’ dat rascal an’ larrup him ontwell he cain’t stan’ straight.”

“No, we’re going to do better than that and a great deal better. If we find him we are going to send him where he won’t inveigle any more innocent people into rascality, and you’re going to help us.”

“W’y, sut’ny, chile, I’ll do all I kin to he’p you git dat rascal, but I don’t know whaih he lives, case he’s allus come hyeah to see me.”

“He’ll come back some day. In the meantime we will be laying for him.”

Aunt Dicey was putting some very flaky biscuits into the oven, and perhaps the memory of other days made the young lawyer prolong his visit and his explanation. When, however, he left, it was with well-laid plans to catch Jason Buford napping.

It did not take long. Stealthily that same evening a tapping came at Aunt Dicey’s door. She opened it, and a small, crouching figure crept in. It was Mr. Buford. He turned down the collar of his coat which he had had closely up about his face and said:

“Well, well, Sis’ Callender, you sut’ny have spoiled us all.”

“La, Brothah Buford, come in hyeah an’ set down. Whaih you been?”

“I been hidin’ fu’ feah of that testimony you give in the court room. What did you do that fu’?”

“La, me, I didn’t know, you didn’t ‘splain to me in de fust.”

“Well, you see, you spoiled it, an’ I’ve got to git out of town as soon as I kin. Sis’ Callender, dese hyeah white people is mighty slippery, and they might catch me. But I want to beg you to go on away from hyeah so’s you won’t be hyeah to testify if dey does. Hyeah’s a hundred dollars of yo’ money right down, and you leave hyeah to-morrer mornin’ an’ go erway as far as you kin git.”

“La, man, I’s puffectly willin’ to he’p you, you know dat.”

“Cose, cose,” he answered hurriedly, “we col’red people has got to stan’ together.”

“But what about de res’ of dat money dat I been ‘vestin’ wid you?”

“I’m goin’ to pay intrus’ on that,” answered the promoter glibly.

“All right, all right.” Aunt Dicey had made several trips to the little back room just off her sitting room as she talked with the promoter. Three times in the window had she waved a lighted lamp. Three times without success. But at the last “all right,” she went into the room again. This time the waving lamp was answered by the sudden flash of a lantern outside.

“All right,” she said, as she returned to the room, “set down an’ lemme fix you some suppah.”

“I ain’t hardly got the time. I got to git away from hyeah.” But the smell of the new baked biscuits was in his nostrils and he could not resist the temptation to sit down. He was eating hastily, but with appreciation, when the door opened and two minions of the law entered.

Buford sprang up and turned to flee, but at the back door, her large form a towering and impassive barrier, stood Aunt Dicey.

“Oh, don’t hu’y, Brothah Buford,” she said calmly, “set down an’ he’p yo’se’f. Dese hyeah’s my friends.”

It was the next day that Robert Fairfax saw him in his cell. The man’s face was ashen with coward’s terror. He was like a caught rat though, bitingly on the defensive.

“You see we’ve got you, Buford,” said Fairfax coldly to him. “It is as well to confess.”

“I ain’t got nothin’ to say,” said Buford cautiously.

“You will have something to say later on unless you say it now. I don’t want to intimidate you, but Aunt Dicey’s word will be taken in any court in the United States against yours, and I see a few years hard labour for you between good stout walls.”

The little promoter showed his teeth in an impotent snarl. “What do you want me to do?” he asked, weakening.

“First, I want you to give back every cent of the money that you got out of Dicey Fairfax. Second, I want you to give up to every one of those Negroes that you have cheated every cent of the property you have accumulated by fraudulent means. Third, I want you to leave this place, and never come back so long as God leaves breath in your dirty body. If you do this, I will save you—you are not worth the saving—from the pen or worse. If you don’t, I will make this place so hot for you that hell will seem like an icebox beside it.”

The little yellow man was cowering in his cell before the attorney’s indignation. His lips were drawn back over his teeth in something that was neither a snarl nor a smile. His eyes were bulging and fear-stricken, and his hands clasped and unclasped themselves nervously.

“I—I——” he faltered, “do you want to send me out without a cent?”

“Without a cent, without a cent,” said Fairfax tensely.

“I won’t do it,” the rat in him again showed fight. “I won’t do it. I’ll stay hyeah an’ fight you. You can’t prove anything on me.”

“All right, all right,” and the attorney turned toward the door.

“Wait, wait,” called the man, “I will do it, my God! I will do it. Jest let me out o’ hyeah, don’t keep me caged up. I’ll go away from hyeah.”

Fairfax turned back to him coldly, “You will keep your word?”

“Yes.”

“I will return at once and take the confession.”

And so the thing was done. Jason Buford, stripped of his ill-gotten gains, left the neighbourhood of Little Africa forever. And Aunt Dicey, no longer a wealthy woman and a capitalist, is baking golden brown biscuits for a certain young attorney and his wife, who has the bad habit of rousing her anger by references to her business name and her investments with a promoter.

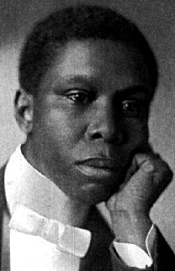

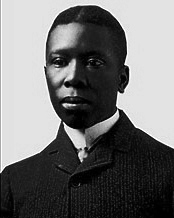

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Promotor

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Een wolk schuift voor de zon. De beelden van grootvader en het molenhuis lossen op. Mels hoort alleen nog de stemmen van het kerkhof. Als bijen zoemen ze rond zijn hoofd.

Er zijn ook stemmen die hij niet wil horen, maar het is moeilijk er zijn oren voor te sluiten. Hij hoort zijn vittende vader, die op hem kankert omdat hij lui en te speels is. `Je moet beter je best doen! Je verlummelt je tijd! Je bent net zo lui als je moeder, die zit ook altijd in de zon! Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niets voor je werk! Zat je alweer in je bootje op de Wijer! Was je weer bij je grootvader Bernhard! Van die man leer je niets goeds!’

Er zijn ook stemmen die hij niet wil horen, maar het is moeilijk er zijn oren voor te sluiten. Hij hoort zijn vittende vader, die op hem kankert omdat hij lui en te speels is. `Je moet beter je best doen! Je verlummelt je tijd! Je bent net zo lui als je moeder, die zit ook altijd in de zon! Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niets voor je werk! Zat je alweer in je bootje op de Wijer! Was je weer bij je grootvader Bernhard! Van die man leer je niets goeds!’

Hij rilt van afschuw. De kreten van zijn vader, die altijd terug blijven komen. Door zijn ongenoegen over het leven was hij zelf vroeg gestorven. Hij haatte de zon. Hij kende alleen plicht.

Om de stem van zijn vader terug te dringen in het graf, draait hij zijn hoofd weg en luistert naar de vogels die rond de silo vliegen. Hij wil nu niet denken. Het brengt de ergernis terug in zijn hoofd. Het wordt steeds moeilijker om die te onderdrukken. Zijn hersens raken erdoor op drift. Hij kan zich steeds minder goed beheersen. Zijn hoofd laat zich niet meer dwingen. Zijn hersens zijn aangetast. Hij herinnert zich dingen die hij niet meer kan plaatsen. Gesprekken die hij met Wilkington heeft gevoerd. Wilkington die hem vertelde hoe het bij hem thuis was. En over een kamertje dat bestemd was voor zijn zoon, maar dat altijd leeg was gebleven. Hij moet die gesprekken hebben gefantaseerd, want hij heeft Wilkington nooit gezien.

Nooit heeft hij geweten dat de graansilo zo veel vogels herbergde. Ze wonen in alle kieren en gaten. Ze vliegen door de kapotte ramen naar binnen en ze zingen en fluiten. Ze zijn vrolijk, maar misschien zouden ze zich ongerust moeten maken, nu Bouwbedrijf Leon van Wijk en Zonen een begin heeft gemaakt met de bouw van appartementen in de silo. De nesten zullen worden vernield.

Langgeleden is hij op het dak geweest, samen met Tijger en Thija. Twaalf jaar waren ze toen. Langs de stalen trap in de fabriek waren ze naar boven geklommen. Van boven had het dorp op een sprookjesdorp geleken.

Op hun rug hadden ze op het dak gelegen, met het gevoel veel dichter bij de wolken te zijn en er zo op te kunnen stappen om weg te zeilen. Onder een veel grotere hemel. En Thija had een gedicht van Jacob over zijn eenzaamheid voorgelezen.

De bouwlift komt omhoog en stopt. Hij hoort de stappen op het dak, achter zijn rug. Ze komen hem halen.

`Je zit hier mooi.’ Het is de stem van Tijger, achter hem, diep, zoals de stem van een zestigjarige. Hij schrikt niet eens dat Tijger zo dicht bij hem is.

Zijn vriend Tijger. In zijn dromen heeft hij altijd met Tijger gepraat. Soms was Tijger twaalf, maar vaak was hij net zo oud als hijzelf. In leeftijd blijkt hij gewoon meegegroeid, zoals een echte vriend voor het leven meegroeit.

`Kijk, het dak van mijn ouderlijk huis’, zegt Mels. `Ik ben er altijd gebleven. Ik heb er met mijn moeder gewoond tot ze stierf. Ik ben er gebleven toen ik trouwde. Als je erop neerkijkt, lijkt het heel mooi.’

`Op afstand is alles mooi’, zegt Tijger. `Maar het is écht een mooi dorp. Schilderachtig zelfs, omdat je nu de silo niet ziet. Als je beneden bent, zie je altijd die rottige toren.’

`Ze knappen de silo op’, zegt Mels. `Ze vinden hem mooi omdat hij oud is. Snap jij dat?’

`Oud is altijd mooi’, zegt Tijger. `Een natte oude krant die opdroogt in de zon wordt ook weer mooi. Ik blader graag in oude kranten. Op het kerkhof krijgen we geen andere kranten dan verwaaide oude kranten. Vaak zijn de letters bijna opgelost door zon en water. Je weet nooit precies wat je leest.’

`Zo is het met nieuw nieuws ook’, zegt Mels. `Je weet nooit precies wat ze je vertellen willen. Hoor jij de stemmen van beneden ook?’

`Waar praten ze over?’

`Veel zul je er niet meer van begrijpen. Alles is anders. Iedereen is anders. Bijna niemand van de mensen die hier nu wonen kent je nog.’

`En mijn zus?’

`Ze herinnert zich niet veel van je.’

`En mijn moeder?’

`Ze heeft zich opgehangen. Ze is nooit over het verlies van jou heen gekomen.’

`Wat spijt me dat’, zegt Tijger met een brok in zijn keel. `Als ik alles had geweten, zou ik niet zo’n waaghals zijn geweest.’

Hij loopt naar de rand van het dak en gaat zitten, zijn benen bungelend over de rand.

`Je bent nog net zo’n waaghals’, zegt Mels. Het valt hem op hoe kaal zijn vriend is geworden. Hij heeft veel weg van grootvader Bernhard.

`Ik wilde altijd alles voor honderd procent’, zegt Tijger.

`Als je toen niet verongelukt was, zou het later wel gebeurd zijn. Niet veel later. Als je zestien of twintig was geweest. Met jouw waaghalzerij zou je nooit oud zijn geworden.’

`Ik ben nooit bang geweest. Soms, in mijn slaap. Maar nu ben ik wel bang.’

`Waarvoor?’

`Voor het leven dat ik heb gemist.’

`Maar je bent teruggekomen.’

`Je weet het toch nog wel’, zegt Tijger. `John Wilkington. Je was er toch zeker van dat zijn ziel in jou doorleefde.’

`Dat denk ik nu nog.’

`De dochters van Wilkington hadden je zussen kunnen zijn.’

Mels is verbijsterd. Opeens begrijpt hij waarom zijn vader zo afstandelijk was. Dat hij nauwelijks woorden had voor zijn moeder. Dat hij altijd weg was.

`Je schrikt er toch niet van’, zegt Tijger. `Je bent uit liefde geboren, wat wil je meer? Zonder Wilkington op zolder was je er nooit geweest.’

`Je hebt gelijk. Ik moet hem dankbaar zijn.’

`Bovendien leef je voort. Je hebt een dochter. Kleinkinderen. Maar ik? Jij bent de enige die nog aan mij denkt. Straks, als jij ook weg bent, ben ik totaal vergeten. Dat maakt me bang. Ik ben bang voor de eenzaamheid. Om hier altijd te moeten blijven.’

`Misschien is het dat wat ze eeuwigheid noemen’, zegt Mels. `Dat je ergens voor altijd blijft.’

`Maar toch niet hier! Weet je nog dat wij vroeger ook wel eens stiekem op het dak van de silo stonden?’ Tijger schuift wat achteruit, trekt zijn benen op en gaat staan.

`Het is maar één keer gebeurd’, zegt Mels. `Toen Thija dat gedicht van Jacob las.’

`Vaker.’

`Dat herinner ik me niet.’

`Ik wilde vleugels maken, om naar beneden te zeilen.’

`Dat klopt. Jij wilde vliegen. Je hebt het niet geprobeerd. Je zou te pletter zijn gevallen.’

`Als iedereen zo denkt, durft niemand wat. Als niemand had willen vliegen, zouden er nog steeds geen vliegtuigen zijn.’

`Zou jij het vliegtuig hebben uitgevonden?’

`Dat denk ik wel. Als ik was blijven leven wel. Ik zou zeker hebben gevlogen.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (104)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Bahnhofstrasse

The eyes that mock me sign the way

Whereto I pass at eve of day.

Grey way whose violet signals are

The trysting and the twining star.

Ah star of evil! star of pain!

Highhearted youth comes not again

Nor old heart’s wisdom yet to know

The signs that mock me as I go.

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

Bahnhofstrasse

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

Grootvader Bernhard heeft een flesje in zijn hand en dept azijn op de arm van Thija, die door een bij is gestoken. Thija wordt vaak gestoken.

`Heb je de angel er uitgezogen?’ vraagt grootvader.

`Heb je de angel er uitgezogen?’ vraagt grootvader.

Thija laat het kleine zwarte puntje zien op de nagel van haar wijsvinger, maar door zijn kippige ogen ziet grootvader het niet.

`Rotbijen’, zegt Thija. `Waarom steken bijen vooral meisjes?’

`Meisjes hebben zoet bloed’, zegt grootvader. `Jullie zijn van suiker. Vroeger woonde er een meisje in ons dorp dat helemaal door de bijen is opgegeten. Van haar hebben ze alleen de botten teruggevonden.’

`Vorige week vertelde u dat ze door een wolf was opgegeten.’

`Zei ik dat? Dan moet ik me toen hebben vergist. Zie je, ik word oud. Ik haal de dingen door elkaar. Ik denk dat er twee meisjes zijn opgegeten, een door bijen en een door een wolf.’

`Dat van die wolf is waar’, zegt Mels. `Grootvader Rudolf vertelt het ook. In een strenge winter, langgeleden, zijn de wolven uit het bos gekomen en hebben een meisje opgegeten.’

`Ik denk dat Rudolf het verhaaltje over het meisje dat is opgegeten door de wolf zelf in omloop heeft gebracht.’

`Zoals u het praatje over het meisje dat is opgegeten door de bijen zelf hebt bedacht?’

`Zo zal het wel zijn gegaan’, lacht grootvader. `Oude mannen vertellen maar wat. Zo ontstaan verhalen. Sommigen schrijven ze op. En dat leren jullie dan op school als geschiedenis.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (103)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Voor de bouwvakkers zit de werkdag erop. Ze lopen terug naar de auto en vertrekken. Mels rolt naar de silo om het resultaat beter te bekijken. De steigers staan al een paar meter boven de grond.

De deur van de voormalige directiekamer staat open. Hij kan er zo binnenrijden. De meubels van de laatste directeuren staan er nog. Alles is gebleven zoals het was. Niemand heeft ooit de moeite genomen hier iets weg te halen. Alles is verrot en vervuild. Het heeft voor niemand waarde meer. Het ziet ernaaruit dat de arbeiders het allemaal in een container voor grof vuil zullen gooien.

De deur van de voormalige directiekamer staat open. Hij kan er zo binnenrijden. De meubels van de laatste directeuren staan er nog. Alles is gebleven zoals het was. Niemand heeft ooit de moeite genomen hier iets weg te halen. Alles is verrot en vervuild. Het heeft voor niemand waarde meer. Het ziet ernaaruit dat de arbeiders het allemaal in een container voor grof vuil zullen gooien.

Het gepolitoerde bureau van Frans-Joseph zit onder het vuil. De kast, met de monsters van de meelproducten die ze maakten, staat er nog. De affiches aan de muur, huisvrouwen die glunderend hun pakken meel vasthouden. De foto’s van de stichters van de fabriek, de weduwe Hubben-Houba zo breed als de molenaar zelf, aan haar rokken zoon Frits, die later de molen zou overnemen, en Tom, de zoon die naar Amerika zou verdwijnen. En de dochters die naar het klooster werden gestuurd, zodat ze geen beroep konden doen op de erfenis, en zo geruisloos uit de geschiedenis van de familie en van de fabriek werden weggesluisd.

De grote foto van Frits Hubben, de erfgenaam die het bedrijf liet verhuizen van de watermolen naar de fabriek, zittend aan een bureau. Naast hem de twee zonen, Frans-Hubert en Frans-Joseph, beiden al met een blik in de ogen die verraadt dat het hen allemaal geen bal interesseert.

De foto’s van de laatste generatie. De kinderen van Frans-Hubert en van Frans-Joseph, van wie niemand nog in het bedrijf heeft gewerkt, vrolijk lachend bijeen op een grasveld voor een villa.

Hij vindt het jammer dat hij niet eerder wist dat dit hier allemaal hing te vergaan. Hij had het graag willen behouden. De foto’s had hij kunnen bewaren in zijn archief, maar nu zijn ze waardeloos. Vocht heeft ze aangetast en beschimmeld. Waterkringen lopen door het rottende papier. Deze rotzooi kan hij niet meer mee naar huis nemen, ook al zou hij het willen. Lizet wil het zeker niet in huis hebben.

In een laatje vindt hij stukken van het reclamearchief, waar Frits Hubben zo zorgvuldig mee omging. Foto’s van vrouwen die verlekkerd een beslag kloppen, met in hun hand een pak patentmeel van Hubben. Foto’s van de verpakkingen van Luxe- en Excellentmeel, die zo mooi zijn dat ze van meel een kostbaarheid maken. Een foto van een dikke man, glunderend met een pak anti-obstipatiemeel vol zemelen in de hand, het wondermeel waarvan hardlijvige mensen een gezonde stoelgang zouden krijgen. Foto’s in een bakkerij waar de balen Hubben Broodmeel hoog liggen opgeslagen, en de bakker en zijn knechten trots de glimmende broden met suikerkorst tonen. Winkels in levensmiddelen en koloniale waren met Hubbens bijzondere soorten brood- en bakmeel in de rekken. Hubbens broodmeel in Indonesië en Zuid-Afrika. Alle foto’s stralen glorie uit en demonstreren daardoor des te meer hoe onnodig de ondergang van de fabriek was.

In zijn woede grijpt hij een pot met een verdroogde bloem van de vensterbank en gooit hem naar het familieportret van de lapzwansen. Het glas rinkelt. Dat doet goed.

Dan pas ziet hij de bouwlift, aan de achterkant van de silo. Die moeten ze vandaag hebben geplaatst. In een opwelling rijdt hij ernaartoe en rolt het platform op van de lift. Hij drukt op de knop. Het ding werkt. Ze hebben vergeten de stroom uit te schakelen.

Langzaam gaat hij naar boven. Het is opwindend. Hij voelt zich een klein kind dat iets doet wat verboden is.

De lift staat stil. Hij is op het hoogste punt aangekomen. Nu weer naar beneden? Of het dak op? De vloerplaat kan uitgeschoven worden. Door een druk op een knop schuift de plaat tot op het dak en vormt een brug.

Hij rijdt het dak op. Hij kijkt rond en voelt zich vrij.

Op nog geen halve meter van de rand stopt hij de rolstoel. Tussen zijn voeten doorkijkend, in de diepte, ziet hij het dorp zoals een vogel het ziet. De rookpluimen boven de rode, blauwe en grauwe daken. Hij kan ze tellen. Nu hij er bovenop kijkt, ontdekt hij de regelmaat in het patroon. Broederlijk liggen de huizen dicht naast elkaar. Hun goten omarmen elkaar en verbinden meer dan honderd huizen. Aan elkaar gesloten pannenrijen, rood, blauw en grijs, versterken het beeld van een gesloten dorp.

Vanaf hier is zijn huis het zevende dak van rechts. Als je het dorp vanaf het noorden binnenkomt, is zijn huis het derde aan de rechterkant. Kom je vanuit het zuiden, dan is het ‘t tweeëntwintigste huis aan de linkerkant. Kom je van de weg langs de Wijer, dan is het vanaf de brug het zevende huis rechts, aan de overkant van de straat.

Zou je met een bootje over de Wijer het dorp binnenvaren tegen de stroom op, dan is het het negende huis links. Tegenover zijn huis ligt slagerij Kemp. Kemp levert bierworst aan café De Zwaan, dat aan de andere kant van de brug ligt, en fijne vleeswaren als er in De Zwaan een uitvaartmaal wordt geserveerd of als er een trouwpartij is.

Maar er komt niemand over de Wijer het dorp binnenvaren. Nu, laat in de middag, is de beek een zilveren streep tussen de weilanden, die soms heel even zwart wordt als er een wolk voor de zon trekt. Vanmiddag zijn er weinig wolken. De zon schijnt zo overdadig dat de miljoenen margrieten langs het riviertje een breed wit tapijt vormen. De oevers zijn net zo wit als vroeger, toen de weide wit was omdat zijn moeder er de lakens op te bleken had gelegd en hij haar moest helpen om stenen op de hoeken te leggen, zodat de wind ze niet kon meenemen.

Van bovenaf lijkt het dorp veel lieflijker dan het in werkelijkheid is. Het centrum van vroeger is maar klein. De huizen staan er dicht op elkaar, alsof ze bang zijn voor de uitgestrektheid van de velden, weilanden en bossen die het dorp omringen, maar vooral voor de groeiende buitenwijken.

Hoewel het dorp diep beneden hem ligt, lijkt alles waar hij naar kijkt toch heel dichtbij. De wand van de silo versterkt de geluiden van beneden, zodat hij alles hoort wat zich daar afspeelt. Er zijn maar een paar mensen op straat, maar doordat hij van zo hoog op hen neerkijkt, hebben ze hun proporties verloren: het zijn gedrongen poppetjes.

Nu hoeft hij alleen maar de rem van zijn rolstoel te ontkoppelen, de wind zal hem wel een zetje willen geven. Voor het eerst sinds lang zullen ze naar hem kijken, allemaal, daar in het dorp. Hij glimlacht bij de gedachte, juist omdat hij dat niet nodig heeft. Hij hoeft geen aandacht, hij wil alleen maar dat ze weten wie hij is.

Hij hoort hoe de mensen met elkaar praten. De daken kunnen wel het zicht op de mensen verbergen, maar nemen niet hun stemmen weg. Hij meent zelfs het ademen van de baby in de tuin van zijn dochter te horen. En het snorren van de poes, die als een bal opgerold aan het voeteneind in de kinderwagen ligt. Het is gevaarlijk. De kat mag niet op de baby gaan liggen, dat zou de dood van het kind kunnen betekenen.

Eigenlijk zou hij moeten schreeuwen, om de kat te verjagen. Maar het beest zal hem niet horen. Van beneden kan niemand hem horen. Hij heeft eens een man vanaf het dak van de silo naar beneden zien schreeuwen, de mond wijdopen, de handen als een toeter aan de mond, maar niemand hoorde hem.

Het is zelfs nog maar de vraag of ze hem van de straat af kunnen zien. Als ze naar boven zouden kijken, kijken ze tegen de onderkant van de rolstoel aan, de voetenplankjes. Ze zullen denken dat het ding iets is van de aannemer die de silo verbouwt.

Opeens hoort hij zoemen achter zijn rug. De lift. De vloerplaat wordt naar binnen gehaald. Dan zakt de lift naar beneden. Heeft iemand hem ontdekt? Halen ze hem nu van het dak?

Hij hoort veel stemmen tegelijk en doet moeite om het koor van geluiden te ontrafelen. Een voor een weet hij de stemmen in zijn oren te ontcijferen. De stem van Kemp, de slager, de stemmen van de samenwonende nichtjes Tinie en Tinie van de Bercken, die beiden al bijna honderd moeten zijn en theedrinken op het terras achter het huis waarmee ze samen in de tijd wegzakken. De postbode, die `post!’ roept bij elke brievenbus waar hij wat in gooit, ook bij een huis dat al jaren leegstaat en waarin de post zich in de gang tot een berg heeft opgehoopt.

Hij hoort niet alleen de stemmen van degenen die beneden zijn, er klinken ook fragmenten door van stemmen van langgeleden. De bewoners van het kerkhof. Grootvader Bernhard. Juffrouw Fijnhout. Ze zijn rumoerig en praten door elkaar heen, net of ze hem allemaal tegelijk iets willen zeggen. Of ze hem roepen. Eén stem is goed te verstaan omdat hij zacht en rustig is. Grootvader Bernhard. Fragmenten van zinnen. `Zonnebloemen zijn … zomerbui … lusten jullie een … heb ik al klaar’, waaruit Mels begrijpt dat regen goed was voor zonnebloemen en dat grootvader glazen limonade voor hen op het aanrecht heeft staan. Hoewel grootvader Bernhard steeds stukken van zinnen inslikt, begrijpt hij hem toch goed als hij zegt: `Niet doen … is heilig … niet de hand aan …’ Even ziet hij hem zitten, in zijn leunstoel, boven op de betonnen grafsteen, maar dan lost zijn beeld op in het zonlicht om weer op te duiken bij het molenhuis, op zijn stukje land bij de Wijer.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (102)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

THE SCAPEGOAT (II)

A year is not a long time. It was short enough to prevent people from forgetting Robinson, and yet long enough for their pity to grow strong as they remembered. Indeed, he was not gone a year. Good behaviour cut two months off the time of his sentence, and by the time people had come around to the notion that he was really the greatest and smartest man in Cadgers he was at home again.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

Here anxious, pitying custom came to him and he prospered again. He was very quiet. Uptown hardly knew that he was again in Cadgers, and it knew nothing whatever of his doings.

“I wonder why Asbury is so quiet,” they said to one another. “It isn’t like him to be quiet.” And they felt vaguely uneasy about him.

So many people had begun to say, “Well, he was a mighty good fellow after all.”

Mr. Bingo expressed the opinion that Asbury was quiet because he was crushed, but others expressed doubt as to this. There are calms and calms, some after and some before the storm. Which was this?

They waited a while, and, as no storm came, concluded that this must be the after-quiet. Bingo, reassured, volunteered to go and seek confirmation of this conclusion.

He went, and Asbury received him with an indifferent, not to say, impolite, demeanour.

“Well, we’re glad to see you back, Asbury,” said Bingo patronisingly. He had variously demonstrated his inability to lead during his rival’s absence and was proud of it. “What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to work.”

“That’s right. I reckon you’ll stay out of politics.”

“What could I do even if I went in?”

“Nothing now, of course; but I didn’t know—-“

He did not see the gleam in Asbury’s half shut eyes. He only marked his humility, and he went back swelling with the news.

“Completely crushed–all the run taken out of him,” was his report.

The black district believed this, too, and a sullen, smouldering anger took possession of them. Here was a good man ruined. Some of the people whom he had helped in his former days–some of the rude, coarse people of the low quarter who were still sufficiently unenlightened to be grateful–talked among themselves and offered to get up a demonstration for him. But he denied them. No, he wanted nothing of the kind. It would only bring him into unfavourable notice. All he wanted was that they would always be his friends and would stick by him.

They would to the death.

There were again two factions in Cadgers. The school-master could not forget how once on a time he had been made a tool of by Mr. Bingo. So he revolted against his rule and set himself up as the leader of an opposing clique. The fight had been long and strong, but had ended with odds slightly in Bingo’s favour.

But Mr. Morton did not despair. As the first of January and Emancipation Day approached, he arrayed his hosts, and the fight for supremacy became fiercer than ever. The school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard brought the school-children in for chorus singing, secured an able orator, and the best essayist in town. With all this, he was formidable.

Mr. Bingo knew that he had the fight of his life on his hands, and he entered with fear as well as zest. He, too, found an orator, but he was not sure that he was as good as Morton’s. There was no doubt but that his essayist was not. He secured a band, but still he felt unsatisfied. He had hardly done enough, and for the school-master to beat him now meant his political destruction.

It was in this state of mind that he was surprised to receive a visit from Mr. Asbury.

“I reckon you’re surprised to see me here,” said Asbury, smiling.

“I am pleased, I know.” Bingo was astute.

“Well, I just dropped in on business.”

“To be sure, to be sure, Asbury. What can I do for you?”

“It’s more what I can do for you that I came to talk about,” was the reply.

“I don’t believe I understand you.”

“Well, it’s plain enough. They say that the school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard fight.”

“Oh, not so hard.”

“No man can be too sure of winning, though. Mr. Morton once did me a mean turn when he started the faction against me.”

Bingo’s heart gave a great leap, and then stopped for the fraction of a second.

“You were in it, of course,” pursued Asbury, “but I can look over your part in it in order to get even with the man who started it.”

It was true, then, thought Bingo gladly. He did not know. He wanted revenge for his wrongs and upon the wrong man. How well the schemer had covered his tracks! Asbury should have his revenge and Morton would be the sufferer.

“Of course, Asbury, you know what I did I did innocently.”

“Oh, yes, in politics we are all lambs and the wolves are only to be found in the other party. We’ll pass that, though. What I want to say is that I can help you to make your celebration an overwhelming success. I still have some influence down in my district.”

“Certainly, and very justly, too. Why, I should be delighted with your aid. I could give you a prominent place in the procession.”

“I don’t want it; I don’t want to appear in this at all. All I want is revenge. You can have all the credit, but let me down my enemy.”

Bingo was perfectly willing, and, with their heads close together, they had a long and close consultation. When Asbury was gone, Mr. Bingo lay back in his chair and laughed. “I’m a slick duck,” he said.

From that hour Mr. Bingo’s cause began to take on the appearance of something very like a boom. More bands were hired. The interior of the State was called upon and a more eloquent orator secured. The crowd hastened to array itself on the growing side.

With surprised eyes, the school-master beheld the wonder of it, but he kept to his own purpose with dogged insistence, even when he saw that he could not turn aside the overwhelming defeat that threatened him. But in spite of his obstinacy, his hours were dark and bitter. Asbury worked like a mole, all underground, but he was indefatigable. Two days before the celebration time everything was perfected for the biggest demonstration that Cadgers had ever known. All the next day and night he was busy among his allies.

On the morning of the great day, Mr. Bingo, wonderfully caparisoned, rode down to the hall where the parade was to form. He was early. No one had yet come. In an hour a score of men all told had collected. Another hour passed, and no more had come. Then there smote upon his ear the sound of music. They were coming at last. Bringing his sword to his shoulder, he rode forward to the middle of the street. Ah, there they were. But–but–could he believe his eyes? They were going in another direction, and at their head rode–Morton! He gnashed his teeth in fury. He had been led into a trap and betrayed. The procession passing had been his–all his. He heard them cheering, and then, oh! climax of infidelity, he saw his own orator go past in a carriage, bowing and smiling to the crowd.

There was no doubting who had done this thing. The hand of Asbury was apparent in it. He must have known the truth all along, thought Bingo. His allies left him one by one for the other hall, and he rode home in a humiliation deeper than he had ever known before.

Asbury did not appear at the celebration. He was at his little news-stand all day.

In a day or two the defeated aspirant had further cause to curse his false friend. He found that not only had the people defected from him, but that the thing had been so adroitly managed that he appeared to be in fault, and three-fourths of those who knew him were angry at some supposed grievance. His cup of bitterness was full when his partner, a quietly ambitious man, suggested that they dissolve their relations.

His ruin was complete.

The lawyer was not alone in seeing Asbury’s hand in his downfall. The party managers saw it too, and they met together to discuss the dangerous factor which, while it appeared to slumber, was so terribly awake. They decided that he must be appeased, and they visited him.

He was still busy at his news-stand. They talked to him adroitly, while he sorted papers and kept an impassive face. When they were all done, he looked up for a moment and replied, “You know, gentlemen, as an ex-convict I am not in politics.”

Some of them had the grace to flush.

“But you can use your influence,” they said.

“I am not in politics,” was his only reply.

And the spring elections were coming on. Well, they worked hard, and he showed no sign. He treated with neither one party nor the other. “Perhaps,” thought the managers, “he is out of politics,” and they grew more confident.

It was nearing eleven o’clock on the morning of election when a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand appeared upon the horizon. It came from the direction of the black district. It grew, and the managers of the party in power looked at it, fascinated by an ominous dread. Finally it began to rain Negro voters, and as one man they voted against their former candidates. Their organisation was perfect. They simply came, voted, and left, but they overwhelmed everything. Not one of the party that had damned Robinson Asbury was left in power save old Judge Davis. His majority was overwhelming.

The generalship that had engineered the thing was perfect. There were loud threats against the newsdealer. But no one bothered him except a reporter. The reporter called to see just how it was done. He found Asbury very busy sorting papers. To the newspaper man’s questions he had only this reply, “I am not in politics, sir.”

But Cadgers had learned its lesson.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (II)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

THE SCAPEGOAT (I)

The law is usually supposed to be a stern mistress, not to be lightly wooed, and yielding only to the most ardent pursuit. But even law, like love, sits more easily on some natures than on others.

This was the case with Mr. Robinson Asbury. Mr. Asbury had started life as a bootblack in the growing town of Cadgers. From this he had risen one step and become porter and messenger in a barber-shop. This rise fired his ambition, and he was not content until he had learned to use the shears and the razor and had a chair of his own. From this, in a man of Robinson’s temperament, it was only a step to a shop of his own, and he placed it where it would do the most good.

This was the case with Mr. Robinson Asbury. Mr. Asbury had started life as a bootblack in the growing town of Cadgers. From this he had risen one step and become porter and messenger in a barber-shop. This rise fired his ambition, and he was not content until he had learned to use the shears and the razor and had a chair of his own. From this, in a man of Robinson’s temperament, it was only a step to a shop of his own, and he placed it where it would do the most good.

Fully one-half of the population of Cadgers was composed of Negroes, and with their usual tendency to colonise, a tendency encouraged, and in fact compelled, by circumstances, they had gathered into one part of the town. Here in alleys, and streets as dirty and hardly wider, they thronged like ants.

It was in this place that Mr. Asbury set up his shop, and he won the hearts of his prospective customers by putting up the significant sign, “Equal Rights Barber-Shop.” This legend was quite unnecessary, because there was only one race about, to patronise the place. But it was a delicate sop to the people’s vanity, and it served its purpose.

Asbury came to be known as a clever fellow, and his business grew. The shop really became a sort of club, and, on Saturday nights especially, was the gathering-place of the men of the whole Negro quarter. He kept the illustrated and race journals there, and those who cared neither to talk nor listen to someone else might see pictured the doings of high society in very short skirts or read in the Negro papers how Miss Boston had entertained Miss Blueford to tea on such and such an afternoon. Also, he kept the policy returns, which was wise, if not moral.

It was his wisdom rather more than his morality that made the party managers after a while cast their glances toward him as a man who might be useful to their interests. It would be well to have a man–a shrewd, powerful man–down in that part of the town who could carry his people’s vote in his vest pocket, and who at any time its delivery might be needed, could hand it over without hesitation. Asbury seemed that man, and they settled upon him. They gave him money, and they gave him power and patronage. He took it all silently and he carried out his bargain faithfully. His hands and his lips alike closed tightly when there was anything within them. It was not long before he found himself the big Negro of the district and, of necessity, of the town. The time came when, at a critical moment, the managers saw that they had not reckoned without their host in choosing this barber of the black district as the leader of his people.

Now, so much success must have satisfied any other man. But in many ways Mr. Asbury was unique. For a long time he himself had done very little shaving–except of notes, to keep his hand in. His time had been otherwise employed. In the evening hours he had been wooing the coquettish Dame Law, and, wonderful to say, she had yielded easily to his advances.

It was against the advice of his friends that he asked for admission to the bar. They felt that he could do more good in the place where he was.

“You see, Robinson,” said old Judge Davis, “it’s just like this: If you’re not admitted, it’ll hurt you with the people; if you are admitted, you’ll move uptown to an office and get out of touch with them.”

Asbury smiled an inscrutable smile. Then he whispered something into the judge’s ear that made the old man wrinkle from his neck up with appreciative smiles.

“Asbury,” he said, “you are–you are–well, you ought to be white, that’s all. When we find a black man like you we send him to State’s prison. If you were white, you’d go to the Senate.”

The Negro laughed confidently.

He was admitted to the bar soon after, whether by merit or by connivance is not to be told.

“Now he will move uptown,” said the black community. “Well, that’s the way with a coloured man when he gets a start.”

But they did not know Asbury Robinson yet. He was a man of surprises, and they were destined to disappointment. He did not move uptown. He built an office in a small open space next his shop, and there hung out his shingle.

“I will never desert the people who have done so much to elevate me,” said Mr. Asbury.

“I will live among them and I will die among them.”

This was a strong card for the barber-lawyer. The people seized upon the statement as expressing a nobility of an altogether unique brand.

They held a mass meeting and indorsed him. They made resolutions that extolled him, and the Negro band came around and serenaded him, playing various things in varied time.

All this was very sweet to Mr. Asbury, and the party managers chuckled with satisfaction and said, “That Asbury, that Asbury!”

Now there is a fable extant of a man who tried to please everybody, and his failure is a matter of record. Robinson Asbury was not more successful. But be it said that his ill success was due to no fault or shortcoming of his.

For a long time his growing power had been looked upon with disfavour by the coloured law firm of Bingo & Latchett. Both Mr. Bingo and Mr. Latchett themselves aspired to be Negro leaders in Cadgers, and they were delivering Emancipation Day orations and riding at the head of processions when Mr. Asbury was blacking boots. Is it any wonder, then, that they viewed with alarm his sudden rise? They kept their counsel, however, and treated with him, for it was best. They allowed him his scope without open revolt until the day upon which he hung out his shingle. This was the last straw. They could stand no more. Asbury had stolen their other chances from them, and now he was poaching upon the last of their preserves. So Mr. Bingo and Mr. Latchett put their heads together to plan the downfall of their common enemy.

The plot was deep and embraced the formation of an opposing faction made up of the best Negroes of the town. It would have looked too much like what it was for the gentlemen to show themselves in the matter, and so they took into their confidence Mr. Isaac Morton, the principal of the coloured school, and it was under his ostensible leadership that the new faction finally came into being.

Mr. Morton was really an innocent young man, and he had ideals which should never have been exposed to the air. When the wily confederates came to him with their plan he believed that his worth had been recognised, and at last he was to be what Nature destined him for–a leader.

The better class of Negroes–by that is meant those who were particularly envious of Asbury’s success–flocked to the new man’s standard. But whether the race be white or black, political virtue is always in a minority, so Asbury could afford to smile at the force arrayed against him.

The new faction met together and resolved. They resolved, among other things, that Mr. Asbury was an enemy to his race and a menace to civilisation. They decided that he should be abolished; but, as they couldn’t get out an injunction against him, and as he had the whole undignified but still voting black belt behind him, he went serenely on his way.

“They’re after you hot and heavy, Asbury,” said one of his friends to him.

“Oh, yes,” was the reply, “they’re after me, but after a while I’ll get so far away that they’ll be running in front.”

“It’s all the best people, they say.”

“Yes. Well, it’s good to be one of the best people, but your vote only counts one just the same.”

The time came, however, when Mr. Asbury’s theory was put to the test. The Cadgerites celebrated the first of January as Emancipation Day. On this day there was a large procession, with speechmaking in the afternoon and fireworks at night. It was the custom to concede the leadership of the coloured people of the town to the man who managed to lead the procession. For two years past this honour had fallen, of course, to Robinson Asbury, and there had been no disposition on the part of anybody to try conclusions with him.

Mr. Morton’s faction changed all this. When Asbury went to work to solicit contributions for the celebration, he suddenly became aware that he had a fight upon his hands. All the better-class Negroes were staying out of it. The next thing he knew was that plans were on foot for a rival demonstration.

“Oh,” he said to himself, “that’s it, is it? Well, if they want a fight they can have it.”

He had a talk with the party managers, and he had another with Judge Davis.

“All I want is a little lift, judge,” he said, “and I’ll make ’em think the sky has turned loose and is vomiting niggers.”

The judge believed that he could do it. So did the party managers. Asbury got his lift. Emancipation Day came.

There were two parades. At least, there was one parade and the shadow of another. Asbury’s, however, was not the shadow. There was a great deal of substance about it–substance made up of many people, many banners, and numerous bands. He did not have the best people. Indeed, among his cohorts there were a good many of the pronounced rag-tag and bobtail. But he had noise and numbers. In such cases, nothing more is needed. The success of Asbury’s side of the affair did everything to confirm his friends in their good opinion of him.

When he found himself defeated, Mr. Silas Bingo saw that it would be policy to placate his rival’s just anger against him. He called upon him at his office the day after the celebration.

“Well, Asbury,” he said, “you beat us, didn’t you?”

“It wasn’t a question of beating,” said the other calmly. “It was only an inquiry as to who were the people–the few or the many.”

“Well, it was well done, and you’ve shown that you are a manager. I confess that I haven’t always thought that you were doing the wisest thing in living down here and catering to this class of people when you might, with your ability, to be much more to the better class.”

“What do they base their claims of being better on?”

“Oh, there ain’t any use discussing that. We can’t get along without you, we see that. So I, for one, have decided to work with you for harmony.”

“Harmony. Yes, that’s what we want.”

“If I can do anything to help you at any time, why you have only to command me.”

“I am glad to find such a friend in you. Be sure, if I ever need you, Bingo, I’ll call on you.”

“And I’ll be ready to serve you.”

Asbury smiled when his visitor was gone. He smiled, and knitted his brow. “I wonder what Bingo’s got up his sleeve,” he said. “He’ll bear watching.”

It may have been pride at his triumph, it may have been gratitude at his helpers, but Asbury went into the ensuing campaign with reckless enthusiasm. He did the most daring things for the party’s sake. Bingo, true to his promise, was ever at his side ready to serve him. Finally, association and immunity made danger less fearsome; the rival no longer appeared a menace.

With the generosity born of obstacles overcome, Asbury determined to forgive Bingo and give him a chance. He let him in on a deal, and from that time they worked amicably together until the election came and passed.

It was a close election and many things had had to be done, but there were men there ready and waiting to do them. They were successful, and then the first cry of the defeated party was, as usual, “Fraud! Fraud!” The cry was taken up by the jealous, the disgruntled, and the virtuous.

Someone remembered how two years ago the registration books had been stolen. It was known upon good authority that money had been freely used. Men held up their hands in horror at the suggestion that the Negro vote had been juggled with, as if that were a new thing. From their pulpits ministers denounced the machine and bade their hearers rise and throw off the yoke of a corrupt municipal government. One of those sudden fevers of reform had taken possession of the town and threatened to destroy the successful party.

They began to look around them. They must purify themselves. They must give the people some tangible evidence of their own yearnings after purity. They looked around them for a sacrifice to lay upon the altar of municipal reform. Their eyes fell upon Mr. Bingo. No, he was not big enough. His blood was too scant to wash away the political stains. Then they looked into each other’s eyes and turned their gaze away to let it fall upon Mr. Asbury. They really hated to do it. But there must be a scapegoat. The god from the Machine commanded them to slay him.

Robinson Asbury was charged with many crimes–with all that he had committed and some that he had not. When Mr. Bingo saw what was afoot he threw himself heart and soul into the work of his old rival’s enemies. He was of incalculable use to them.

Judge Davis refused to have anything to do with the matter. But in spite of his disapproval it went on. Asbury was indicted and tried. The evidence was all against him, and no one gave more damaging testimony than his friend, Mr. Bingo. The judge’s charge was favourable to the defendant, but the current of popular opinion could not be entirely stemmed. The jury brought in a verdict of guilty.

“Before I am sentenced, judge, I have a statement to make to the court. It will take less than ten minutes.”

“Go on, Robinson,” said the judge kindly.

Asbury started, in a monotonous tone, a recital that brought the prosecuting attorney to his feet in a minute. The judge waved him down, and sat transfixed by a sort of fascinated horror as the convicted man went on. The before-mentioned attorney drew a knife and started for the prisoner’s dock. With difficulty he was restrained. A dozen faces in the court-room were red and pale by turns.

“He ought to be killed,” whispered Mr. Bingo audibly.

Robinson Asbury looked at him and smiled, and then he told a few things of him. He gave the ins and outs of some of the misdemeanours of which he stood accused. He showed who were the men behind the throne. And still, pale and transfixed, Judge Davis waited for his own sentence.

Never were ten minutes so well taken up. It was a tale of rottenness and corruption in high places told simply and with the stamp of truth upon it.

He did not mention the judge’s name. But he had torn the mask from the face of every other man who had been concerned in his downfall. They had shorn him of his strength, but they had forgotten that he was yet able to bring the roof and pillars tumbling about their heads.

The judge’s voice shook as he pronounced sentence upon his old ally–a year in State’s prison.

Some people said it was too light, but the judge knew what it was to wait for the sentence of doom, and he was grateful and sympathetic.

When the sheriff led Asbury away the judge hastened to have a short talk with him.

“I’m sorry, Robinson,” he said, “and I want to tell you that you were no more guilty than the rest of us. But why did you spare me?”

“Because I knew you were my friend,” answered the convict.

“I tried to be, but you were the first man that I’ve ever known since I’ve been in politics who ever gave me any decent return for friendship.”

“I reckon you’re about right, judge.”

In politics, party reform usually lies in making a scapegoat of someone who is only as criminal as the rest, but a little weaker. Asbury’s friends and enemies had succeeded in making him bear the burden of all the party’s crimes, but their reform was hardly a success, and their protestations of a change of heart were received with doubt. Already there were those who began to pity the victim and to say that he had been hardly dealt with.

Mr. Bingo was not of these; but he found, strange to say, that his opposition to the idea went but a little way, and that even with Asbury out of his path he was a smaller man than he was before. Fate was strong against him. His poor, prosperous humanity could not enter the lists against a martyr. Robinson Asbury was now a martyr.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (I)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

The Flying Man

The Ethnologist looked at the bhimraj feather thoughtfully. “They seemed loth to part with it,” he said.

“It is sacred to the Chiefs,” said the lieutenant; “just as yellow silk, you know, is sacred to the Chinese Emperor.”

The Ethnologist did not answer. He hesitated. Then opening the topic abruptly, “What on earth is this cock-and-bull story they have of a flying man?”

The lieutenant smiled faintly. “What did they tell you?”

The lieutenant smiled faintly. “What did they tell you?”

“I see,” said the Ethnologist, “that you know of your fame.”

The lieutenant rolled himself a cigarette. “I don’t mind hearing about it once more. How does it stand at present?”

“It’s so confoundedly childish,” said the Ethnologist, becoming irritated. “How did you play it off upon them?”

The lieutenant made no answer, but lounged back in his folding-chair, still smiling.

“Here am I, come four hundred miles out of my way to get what is left of the folk-lore of these people, before they are utterly demoralised by missionaries and the military, and all I find are a lot of impossible legends about a sandy-haired scrub of an infantry lieutenant. How he is invulnerable — how he can jump over elephants — how he can fly. That’s the toughest nut. One old gentleman described your wings, said they had black plumage and were not quite as long as a mule. Said he often saw you by moonlight hovering over the crests out towards the Shendu country. — Confound it, man!”

The lieutenant laughed cheerfully. “Go on,” he said. “Go on.”

The Ethnologist did. At last he wearied. “To trade so,” he said, “on these unsophisticated children of the mountains. How could you bring yourself to do it, man?”

“I’m sorry,” said the lieutenant, “but truly the thing was forced upon me. I can assure you I was driven to it. And at the time I had not the faintest idea of how the Chin imagination would take it. Or curiosity. I can only plead it was an indiscretion and not malice that made me replace the folk-lore by a new legend. But as you seem aggrieved, I will try and explain the business to you.

“It was in the time of the last Lushai expedition but one, and Walters thought these people you have been visiting were friendly. So, with an airy confidence in my capacity for taking care of myself, he sent me up the gorge — fourteen miles of it — with three of the Derbyshire men and half a dozen Sepoys, two mules, and his blessing, to see what popular feeling was like at that village you visited. A force of ten — not counting the mules — fourteen miles, and during a war! You saw the road?”

“Road!” said the Ethnologist.

“It’s better now than it was. When we went up we had to wade in the river for a mile where the valley narrows, with a smart stream frothing round our knees and the stones as slippery as ice. There it was I dropped my rifle. Afterwards the Sappers blasted the cliff with dynamite and made the convenient way you came by. Then below, where those very high cliffs come, we had to keep on dodging across the river — I should say we crossed it a dozen times in a couple of miles.

“We got in sight of the place early the next morning. You know how it lies, on a spur halfway between the big hills, and as we began to appreciate how wickedly quiet the village lay under the sunlight, we came to a stop to consider.

“At that they fired a lump of filed brass idol at us, just by way of a welcome. It came twanging down the slope to the right of us where the boulders are, missed my shoulder by an inch or so, and plugged the mule that carried all the provisions and utensils. I never heard such a death-rattle before or since. And at that we became aware of a number of gentlemen carrying matchlocks, and dressed in things like plaid dusters, dodging about along the neck between the village and the crest to the east.

“‘Right about face,’ I said. ‘Not too close together.’

“And with that encouragement my expedition of ten men came round and set off at a smart trot down the valley again hitherward. We did not wait to save anything our dead had carried, but we kept the second mule with us — he carried my tent and some other rubbish — out of a feeling of friendship.

“So ended the battle — ingloriously. Glancing back, I saw the valley dotted with the victors, shouting and firing at us. But no one was hit. These Chins and their guns are very little good except at a sitting shot. They will sit and finick over a boulder for hours taking aim, and when they fire running it is chiefly for stage effect. Hooker, one of the Derbyshire men, fancied himself rather with the rifle, and stopped behind for half a minute to try his luck as we turned the bend. But he got nothing.