Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

5

A problem which I find it far more difficult to solve is this: how in the world Giorgio Mirelli, who would fly with such impatience from every complication, can have lost himself to this woman, to the point of laying down his life on her account.

Almost all the details are lacking that would enable me to solve this problem, and I have said already that I have no more than a summary report of the drama.

I know from various sources that the Nestoroff, at Capri, when Giorgio Mirelli saw her for the first time, was in distinctly bad odour, and was treated with great diffidence by the little Russian colony, which for some years past has been settled upon that island.

Some even suspected her of being a spy, perhaps because she, not very prudently, had introduced herself as the widow of an old conspirator, who had died some years before her coming to Capri, a refugee in Berlin. It appears that some one wrote for information, both to Berlin and to Petersburg, with regard to her and to this unknown conspirator, and that it came to light that a certain Nikolai Nestoroff had indeed been for some years in exile in Berlin, and had died there, but without ever having given anyone to understand that he was exiled for political reasons. It appears to have become known also that this Nikolai Nestoroff had taken her, as a little girl, from the streets, in one of the poorest and most disreputable quarters of Petersburg, and, after having her educated, had married her; and then, reduced by his vices to the verge of starvation had lived upon her, sending her out to sing in music-halls of the lowest order, until, with the police on his track, he had made his escape, alone, into Germany. But the Nestoroff, to my knowledge, indignantly denies all these stories.

That she may have complained privately to some one of the ill-treatment, not to say the cruelty she received from her girlhood at the hands of this old man is quite possible; but she does not say that he lived upon her; she says rather that, of her own accord, obeying the call of her passion, and also, perhaps, to supply the necessities of life, having overcome his opposition, she took to acting in the provinces, a-c-t-i-n-g, mind, on the legitimate stage; and that then, her husband having fled from Russia for political reasons and settled in Berlin, she, knowing him to be in frail health and in need of attention, taking pity on him, had joined him there and remained with him till his death. What she did then, in Berlin, as a widow, and afterwards in Paris and Vienna, cities to which she often refers, shewing a thorough knowledge of their life and customs, she neither says herself nor certainly does anyone ever venture to ask her.

For certain people, for innumerable people, I should say, who are incapable of seeing anything but themselves, love of humanity often, if not always, means nothing more than being pleased with themselves.

Thoroughly pleased with himself, with his art, with his studies of landscape, must Giorgio Mirelli, unquestionably, have been in those days at Capri.

Indeed–and I seem to have said this before–his habitual state of mind was one of rapture and amazement. Given such a state of mind, it is easy to imagine that this woman did not appear to him as she really was, with the needs that she felt, wounded, scourged, poisoned by the distrust and evil gossip that surrounded her; but in the fantastic transfiguration that he at once made of her, and illuminated by the light in which he beheld her. For him feelings must take the form of colours, and, perhaps, entirely engrossed in his art, he had no other feeling left save for colour. All the impressions that he formed of her were derived exclusively, perhaps, from the light which he shed upon her; impressions, therefore, that were felt by him alone. She need not, perhaps could not participate in them. Now, nothing irritates us more than to be shut out from an enjoyment, vividly present before our eyes, round about us, the reason of which we can neither discover nor guess. But even if Giorgio Mirelli had told her of his enjoyment, he could not have conveyed it to her mind. It was a joy felt by him alone, and proved that he too, in his heart, prayed and wished for nothing else of her than her body; not, it is true, like other men, with base intent; but even this, in the long run–if you think it over carefully–could not but increase the woman’s irritation. Because, if the failure to derive any assistance, in the maddening uncertainties of her spirit, from the many who saw and desired nothing in her save her body, to satisfy on it the brutal appetite of the senses, filled her with anger and disgust; her anger with the one man, who also desired her body and nothing more; her body, but only to extract from it an ideal and absolutely self-sufficient pleasure, must have been all the stronger, in so far as every provocative of disgust was entirely lacking, and must have rendered more difficult, if not absolutely futile, the vengeance which she was in the habit of wreaking upon other people. An angel, to a woman, is always more irritating than a beast.

I know from all Giorgio Mirelli’s artist friends in Naples that he was spotlessly chaste, not because he did not know how to make an impression upon women, but because he instinctively avoided every vulgar distraction.

To account for his suicide, which beyond question was largely due to the Nestoroff, we ought to assume that she, not cared for, not helped, and irritated to madness, in order to be avenged, must with the finest and subtlest art have contrived that her body should gradually come to life before his eyes, not for the delight of his eyes alone; and that, when she saw him, like all the rest, conquered and enslaved, she forbade him, the better to taste her revenge, to take any other pleasure from her than that with which, until then, he had been content, as the only one desired, because the only one worthy of him.

‘We ought’, I say, to assume this, but only if we wish to be ill-natured. The Nestoroff might say, and perhaps does say, that she did nothing to alter that relation of pure friendship which had grown up between herself and Mirelli; so much so that when he, no longer contented with that pure friendship, more impetuous than ever owing to the severe repulse with which she met his advances, yet, to obtain his purpose, offered to marry her, she struggled for a long time–and this is true; I learned it on good authority–to dissuade him, and proposed to leave Capri, to disappear; and in the end remained there only because of his acute despair.

But it is true that, if we wish to be ill-natured, we may also be of opinion that both the early repulse and the later struggle and threat and attempt to leave the island, to disappear, were perhaps so many artifices carefully planned and put into practice to reduce this young man to despair after having seduced him, and to obtain from him all sorts of things which otherwise he would never, perhaps, have conceded to her. Foremost among them, that she should be introduced as his future bride at the Villa by Sorrento to that dear Granny, to that sweet little sister, of whom he had spoken to her, and to the sister’s betrothed.

It seems that he, Aldo Nuti, more than, the two women, resolutely opposed this claim. Authority and power to oppose and to prevent this marriage he did not possess, for Giorgio was now his own master, free to act as he chose, and considered that he need no longer give an account of himself to anyone; but that he should bring this woman to the house and place her in contact with his sister, and expect the latter to welcome her and to treat her as a sister, this, by Jove, he could and must oppose, and oppose it he did with all his strength. But were they, Granny Rosa and Duccella, aware what sort of woman this was that Giorgio proposed to bring to the house and to marry? A Russian adventuress, an actress, if not something worse! How could he allow such a thing, how not oppose it with all his strength?

Again “with all his strength”… Ah, yes, who knows how hard Granny Rosa and Duccella had to fight in order to overcome, little by little, by their sweet and gentle persuasion, all the strength of Aldo Nuti. How could they have imagined what was to become of that strength at the sight of Varia Nestoroff, as soon as she set foot, timid, ethereal and smiling, in the dear villa by Sorrento!

Perhaps Giorgio, to account for the delay which Granny Rosa and Duccella shewed in answering, may have said to the Nestoroff that this delay was due to the opposition “with all his strength” of his sister’s future husband; so that the Nestoroff felt the temptation to measure her own strength against this other, at once, as soon as she set foot in the villa. I know nothing! I know that Aldo Nuti was drawn in as though into a whirlpool and at once carried away like a wisp of straw by passion for this woman.

I do not know him. I saw him as a boy, once only, when I was acting as Giorgio’s tutor, and he struck me as a fool. This impression of mine does not agree with what Mirelli said to me about him, on my return from Liege, namely that he was ‘complicated’. Nor does what I have heard from other people, with regard to him correspond in the least with this first impression, which however has irresistibly led me to speak of him according to the idea that I had formed of him from it. I must, really, have been mistaken. Duccella found it possible to love him! And this, to my mind, does more than anything else to prove me in the wrong. But we cannot control our impressions. He may be, as people tell me, a serious young man, albeit of a most ardent temperament; for me, until I see him again, he will remain that fool of a boy, with the baron’s coronet on his handkerchiefs and portfolios, the young gentleman who ‘would so love to become an actor’.

He became one, and not by way of make-believe, with the Nestoroff, at Giorgio Mirelli’s expense. The drama was unfolded at Naples, shortly after the Nestoroff’s introduction and brief visit to the house at Sorrento. It seems that Nuti returned to Naples with the engaged couple, after that brief visit, to help the inexperienced Giorgio and her who was not yet familiar with the town, to set their house in order before the wedding.

Perhaps the drama would not have happened, or would have had a different ending, had it not been for the complication of Duccella’s engagement to, or rather her love for Nuti. For this reason Giorgio Mirelli was obliged to concentrate on himself the violence of the unendurable horror that overcame him at the sudden discovery of his betrayal.

Aldo Nuti rushed from Naples like a madman before there arrived from Sorrento at the news of Giorgio’s suicide Granny Rosa and Duccella.

Poor Duccella, poor Granny Rosa! The woman who from thousands and thousands of miles away came to bring confusion and death into your little house where with the jasmines bloomed the most innocent of idylls, I have her here, now, in front of my machine, every day; and, if the news I have heard from Polacco be true, I shall presently have him here as well, Aldo Nuti, who appears to have heard that the Nestoroff is leading lady with the Kosmograph.

I do not know why, my heart tells me that, as I turn the handle of this photographic machine, I am destined to carry out both your revenge and your poor Giorgio’s, dear Duccella, dear Granny Rosa!

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

(to be continued)

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Ton van Reen

EEN NOG SCHONERE SCHIJN VAN WITHEID

Een winterverhaal

4

Onze lakens zwegen gelukkig altijd, ook als de pastoor voorbijfietste en ze hem toe hadden kunnen schreeuwen wat jongens in bed wel deden maar nooit opbiechtten, maar dat deden de lakens, die net zo’n hekel hadden aan wasbeurten als ik, lekker niet. De pastoor met zijn zoete praatjes kon hen gestolen worden.

“En toen, grootmoeder?”

Moeder, nog rood van de kou, spreidde haar armen naar de kachel om zich te warmen en keek mij beschuldigend aan.

“Je had me wel kunnen helpen, kwajong,” zei ze.

“En toen?” vroeg ik. Ik probeerde me voor te stellen hoe mijn moeder, die nu in die oude jas, die ooit van vader was geweest maar nog te goed om weg te gooien, met haar gezicht rood van de kou in de rozige gloed van de kachel stond, ooit als meisje in de gang had gestaan voor de spiegel met zijn gepolitoerde nepgouden lijst en haar haren kamde. Maar het beeld van het meisje met de vlechten, dat ze was toen ze twaalf was en zoals ze op een foto op het dressoir stond, kreeg ik niet voor ogen. Hoewel die oude jas zo oud en haveloos was, vond ik hem nu heel erg mooi en precies bij haar passend. Het kon niet schelen dat er geen knopen aan zaten. Ik begreep opeens dat ze die jas nooit weg zou kunnen doen omdat hij van mijn vader was geweest. Het kon niet schelen dat hij legergroen was en dat hij tien jaar in de paardenstal van de marechaussee aan de kapstok had gehangen. Er was geen lekkerder lucht dan de geur van de paardenstal van mijn vader de wachtmeester bij de marechaussee die, hoog gezeten op zijn paard, mijn moeder ooit ten huwelijk had gevraagd, zonder dat hij wist hoe ze heette en zonder dat ze hem bij zijn naam kon noemen, terwijl ze beiden wisten dat ze nooit meer buiten elkaar zouden kunnen.

“En toen, grootmoeder?”

Ze keek me een beetje verbaasd aan.

“De rest weet je zelf wel.”

“Ja ja, de rest weet ik zelf.” Ik wist dat ik nu haar verhaal aan mezelf moest vertellen, omdat mijn moeder, die de hoofdpersoon in haar vertelsel was, nu bij ons in de keuken was. Nu kon grootje het verhaal over haar dochter, die haar niet wilde helpen met de was, niet afmaken, want dat was tegen haar regels. Een andere keer, als moeder naar de bakker was of bij een buurvrouw thee was drinken, zou ze de rest vertellen.

“Ja ja, ik weet alles,” herhaalde ik.

“Is er weer iets wat ik niet mag weten?” vroeg moeder, een beetje ontdooiend in de gloed van de kachel, hoewel de koude lucht nog steeds tussen de plooien van haar jas ontsnapte en de geuren van ijs en rook van de steenfabriek de keuken binnenbracht.

wordt vervolgd

Het verhaal Een nog schonere schijn van witheid van Ton van Reen werd uitgegeven op 26 februari 2012 in opdracht van De Bibliotheek Maas en Peel, ter gelegenheid van de heropening van de bibliotheek in Maasbree.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van

Seconden later zijn wij allerbesten

Seconden later zijn wij allerbesten.

Hij spreekt alweer van vroeger en van toen,

van: “ weet je nog?” en onze eerste zoen.

Hij koos de mooiste, deelde wat er restte.

Wij lachend om die avond in ’t plantsoen,

de avond in het gras op Tilburg West en

ik kon niet wachten op mijn grootse test en

zag hem mijn liefje van haar goed ontdoen.

Terwijl hij alle mensen om zich rijgt,

zijn nonchalante ‘k-weet-’t-ook-niet-geste,

ben ik diegene die zacht grapt en zwijgt.

Zal ik dan toch de rake waarheid ketsen?

Hem laten zien dat ik hem overstijg?

Ach wat, ik blijf toch altijd de gekwetste.

Esther Porcelijn

30 januari 2012

(uit: Over vriendschappen en andere ongemakken, Aardige Jongens, maart 2012)

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Ton van Reen

EEN NOG SCHONERE SCHIJN VAN WITHEID

Een winterverhaal

Het was lekker warm in de keuken van mijn grootmoeder, die toevallig ook onze keuken was, ik weet niet eens meer of wij bij háár woonden of zij bij óns. Het was vooral zo behaaglijk omdat er ijspegels van bijna een meter aan de dakrand zonder goot hingen, sprookjesachtig schitterend ijs. Doordat de zon erop stond, zag ik de kleuren erin leven. De ijspegels maakten van ons sobere huis een toverkasteeltje, vooral door de sprookjesachtige verhalen die mijn grootmoeder, het liefst met dit soort winterweer, aan ons vertelde. Vaak verhalen over de geheimen van de Peel, over de verborgen schatten in het Soemeer die je alleen met middernacht kunt vinden als je er zeker van bent dat je ziel zo wit is als een pas gewassen laken, of over de geest van de Romein die de gouden helm zoekt die hij in het moeras heeft verloren. Verhalen soms zo griezelig dat ik van spanning met mijn kont vast leek te vriezen aan mijn stoel. Stijf van spanning, bang dat ik door me te bewegen de hele sfeer in de keuken naar de maan zou helpen en de betovering van de vertelling zou verbreken.

Zo ging het meestal, maar elke dag was het een beetje anders.

“Er was eens een meisje dat haar moeder nooit wilde helpen met de was, met de was strijken, met de was ophangen,” zo begon grootje haar verhaal van vandaag. Misschien kwam ze tot dit verhaal door mijn moeder, haar dochter, die buiten bezig was met het wasgoed. Moeder haalde de stijf bevroren lakens, waaruit de dromen van drie jongens en een meisje waren weg gekookt, van de lijn. Helaas moest de wasbeurt worden overgedaan omdat een hoestbui van de schoorsteen van de steenfabriek een laagje roet over de schone lakens had gespreid, alsof de duivel eroverheen had geademd.

Mijn grootmoeder betrok de gebeurtenissen van het moment altijd in haar verhalen, dus toen ze vertelde over het ongehoorzame meisje dat haar moeder niet wilde helpen, keken we beiden tussen de ijspegels door naar mijn moeder die buiten in gevecht was met onwillige lakens die niet meer terugwilden naar onze jongensbedden en zich ijzig stijf hielden in hun verzet tegen een volgende gloeiende kookbeurt in de wasketel. Met over haar zomerschort een oude jas, die open hing door gebrek aan knopen, probeerde moeder de lakens die dreigden te breken van de draad te tillen. Fier, met wapperende haren in de wind, stond ze daar, kwaad omdat wij geen poot uitstaken om haar te helpen.

Grootmoeder en ik spanden vaker samen tegen moeder, vooral in een geval als dit, omdat het allemaal haar eigen schuld was. Grootmoeder had haar gewaarschuwd en wel tien keer gezegd dat het veel te koud was om de natte lakens buiten te hangen. En ik had haar gezegd dat ik het helemaal niet nodig vond dat de lakens werden gewassen omdat ik het juist lekker vond dat ze een beetje vies waren en naar mij roken als ik naar bed ging. Ik vond het helemaal geen lolletje om in de winterse slaapkamer tussen koude gesteven lakens te slapen, liever waren me de lakens die een beetje aanvoelden als mijn eigen vel, een huid die ook weinig zeep kon verdragen.

Het was wel spannend dat het verhaal dat grootmoeder nu begon te vertellen over mijn moeder ging en dat ik dat wat ik nu te horen kreeg eigenlijk niet mocht weten. Een kind hoorde niets te weten van de kwade streken van zijn ouders toen ze zelf nog kinderen waren. Maar grootmoeder lapte al dit soort wetten aan haar laars. Daarom vertelde ze het verhaal over een meisje dat niet wilde luisteren in de vorm van een sprookje, dat had ik wel door. Ik mocht het geloven of niet. Misschien snapte ik het nu nog niet, maar later wel.

Met de verhalen van grootmoeder kon het alle kanten op. Ze hield er vooral van om te vertellen over de mensen ‘die van ons waren’ maar die er toevallig niet bij waren, in ieder geval niet binnen gehoorafstand. Omdat wij twee alleen binnen waren en moeder buiten bezig was, was zij het onderwerp. Ik kende grootmoeder door en door. Straks als ik naar Jong Nederland was en zij alleen was met moeder, zou ze, zeker weten, het een en ander over mij vertellen. Soms deed ik of ik wegging en sloop even later op kousenvoeten door de achterdeur naar binnen. Het was altijd raak: dan had ze het over mij. Ik had haar betrapt, maar toch ging ik weg, omdat ik iets hoorde dat niet bedoeld was voor mijn oren. Mijn gedrag was tegen haar spelregels.

wordt vervolgd

Het verhaal Een nog schonere schijn van witheid van Ton van Reen werd uitgegeven op 26 februari 2012 in opdracht van De Bibliotheek Maas en Peel, ter gelegenheid van de heropening van de bibliotheek in Maasbree. Teksten uit het verhaal zijn aangebracht op glazen wanden. © Ton van Reen

fleursdumal.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van

![]()

Levenslus

Voor Ton de Witte 29 maart 1966 – 6 maart 2012

Het absoluut omgekeerde van leven

Alles in negatief zien, want kleuren zijn niet mooi

Alles is niet.

Niet hier maar daar kent niemand het.

Niet eens verveling, gewoon, nee niet gewoon.

Altijd de buitenstaander.

Lachen, maar waarom. De vragen voorbij.

Zo ver van erbij zijn, bij de anderen.

Mensen zijn zo vluchtig.

Wie kan het iets schelen hoe je bent,

Of je echt lacht of niet.

En wel zo gewoon.

Gewoon bestek, gewoon boodschappen, gewoon ansjovis

Gewoon mensen.

Maar altijd weten dat vragen ook maar vragen is.

Gewoon de afwas, gewoon een biertje, gewoon je buurman, gewoon de wc, gewoon de deurklink.

Gewoon de bank, gewoon de naden in je schoen, gewoon haren.

Gewoon waaien, gewoon slapen, gewoon knikken en je wapenen.

Gewoon ideeën.

Gewoon de oude doos, gewoon de rode huisjes van Monopoly.

Gewoon mee.

Gewoon je sperziebonen laten liggen.

Gewoon de blaadjes bezinken in je thee.

Was er geen klaagzang zoals in de films? Was het maar als in de films, dan komt er altijd een wijze man uit een oud dorp die bijtend op een graantje net die ene zin zegt die wegpinkt voor ‘t traantje.

Zou er licht zijn? Licht zo licht als een eindeloze zucht.

‘t Is geen vlucht, het is een sprong.

Een groot “waarom?” staat te kloppen maar het huis is te vol. Het staat te bonken maar is niet thuis.

Een vraag is al teveel. Als een vraag er is dan kun je nog door.

Het past niet, het hoofd te vol.

Het is niet laf, wie is er laf?

Beleefd voor het leven.

Het leven serieus nemen.

Juist dan zijn vragen maar vragen.

Alles in negatief zien, lachen en knikken.

Altijd beleefd voor het leven geweest.

Alles is niet. Nu niet.

Esther Porcelijn

Stadsdichter Tilburg

Ton de Witte (45) is dinsdag (6 maart 2012) plotseling overleden. Hij laat zijn collega’s bij De NWE Vorst in Tilburg in diepe rouw achter. Ton de Witte was de stuwende kracht achter de culturele stadswandelingen van L’Avventura en maakte naam als gedreven steunpilaar, vormgever en theatermaker van veel jonge acteurs en dansers.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

foto joep eijkens

Esther Porcelijn

Trots op Tilburg?!

Doe maar gewoon dan doe je al gek genoeg!?

“Doe maar gewoon!” Zegt de man tegen de vrouw.

“Dan doe je al gek genoeg.”

“Spaar jezelf of je piekt te vroeg

En dan geeft niemand om jou.”

De vrouw, hevig verontwaardigd,

Wilde hem enkel bekoren:

“Mijn borsten gelift tot aan mijn oren,

ze raken al jaren mijn gezicht.”

“Het onkruid tussen de tegels geplukt,

de oude details gerenoveerd.

“Elke andere man zou vereerd

zijn en intens verrukt!”

“Al jaren klaagde je over mijn vormen

Je vond ze niet bij de tijd!”

“Ik moest zelfs, tot mijn spijt,

mijn oude beelden bestormen”

“Nee nee,” zei de man, “je vergist je schat!”

“Mijn liefde voor jou is geen prijs.”

“Ik hoef geen hemels paradijs,

Voor mij volstaat de grauwe stad.”

“Bij mij valt niets te winnen.

Ik heb frietsaus, geen mayonaise

En zeker geen bearnaise!

Juist daarom wil ik je beminnen!”

“Je buitenkant neem ik voor lief

Het gaat mij om van binnen!”

“Ik hou van al je twintig kinnen

En van je vlekkenmotief!”

“Je kent mij toch, ik ben niet van ingewikkeld.”

“Van hoge kunst en woorden,

en muziek met zware akkoorden!”

“Van theater met een grote T, ’t is niet wat mij prikkelt!”

“Ik hoef geen importevangelie

Van die boven-rivierse mensen,

met hun grote wereldse wensen.”

“Eenvoud is de schoonste harmonie!

“Ach hypocriet!”, zei de vrouw tot haar man,

“wat nou, doe maar gewoon?”

“Je spreekt zelf als de hoogste boom,

Ja, jij kan er wat van!”

“Geen opsmuk, zeg je, wat een gezwam!”

“Eerst zeuren dat het minder moet,

dat uiterlijk er niet toe doet

En geen theater uit Amsterdam..”

“..En dan morgen met een stoet

Van 25 mensen naar Madurodam!”

Stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn schreef het gedicht “trots op tilburg?!” t.b.v. de wedstrijd voor beste binnenstad van Nederland. Voor elke genomineerde stad ging een delegatie van 25 man naar Madurodam voor de bekendmaking van de winnaar.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

foto joep eijkens

Esther Porcelijn

In Breda en in Tilburg

Ik woonde in een ansichtkaart

Breda is één groot vroeger

Een raam op zolder starend naar

De kerk en alle kroegen;

Waar mensen feestend zweterig

Zich door de biertjes zwoegen.

Omlijst is elk klein detail

De hofjes en de muren

Van baksteen staat elk huis zo lang

Dat al eeuwenoude uren

Mensen turend hun gedachten

Op de stad afvuren.

Toch lijken de inwoners

De schoonheid niet te delen

Ze ogen rijk en carnaval

Religie gaat vervelen;

Het boordje is geruild voor polo

‘t Verstikt nog steeds hun kelen.

Hen lijkt de vreemdheid ongehoord

Ze houden niet van anders

Geen polo: is te stumperig

En de rest, de omstanders?

Zij drinken er lustig op los

En dansen hun polonaise om de bijstanders.

Nu ik verhuis naar een andere stad

Waar oude muren zeldzaam

En hofjes onbestaand

Kijk ik door mijn nieuwe raam:

Een plein met auto’s en bomen

Vroeger heeft hier een andere naam.

De mensen, echter, zijn zélf anders

Sferen van raarheid, hun gelaat

Is minder strak hooghartig

Rokerige dronkenmanspraat,

Tijdens lange cafénachten,

Dragen ze als een sieraad.

Ik woonde in een ansichtkaart

Waar ik de schoonheid had

De nieuwe plaats is anders, ja,

Maar vrolijk en minder glad

Bij dat besef verscheur ik mijn post

Een ansichtkaart is toch maar plat.

Esther Porcelijn is stadsdichter van Tilburg

Kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: City Poets / Stadsdichters, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

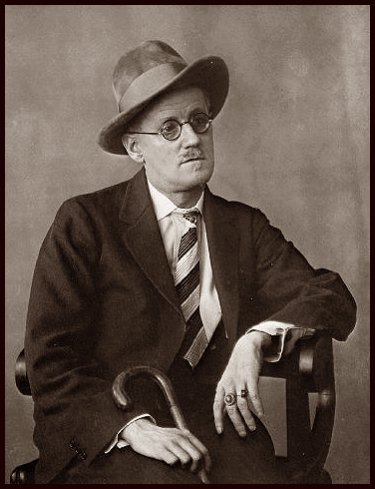

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Painful Case

Mr. James Duffy lived in Chapelizod because he wished to live as far as possible from the city of which he was a citizen and because he found all the other suburbs of Dublin mean, modern and pretentious. He lived in an old sombre house and from his windows he could look into the disused distillery or upwards along the shallow river on which Dublin is built. The lofty walls of his uncarpeted room were free from pictures. He had himself bought every article of furniture in the room: a black iron bedstead, an iron washstand, four cane chairs, a clothes-rack, a coal-scuttle, a fender and irons and a square table on which lay a double desk. A bookcase had been made in an alcove by means of shelves of white wood. The bed was clothed with white bedclothes and a black and scarlet rug covered the foot. A little hand-mirror hung above the washstand and during the day a white-shaded lamp stood as the sole ornament of the mantelpiece. The books on the white wooden shelves were arranged from below upwards according to bulk. A complete Wordsworth stood at one end of the lowest shelf and a copy of the Maynooth Catechism, sewn into the cloth cover of a notebook, stood at one end of the top shelf. Writing materials were always on the desk. In the desk lay a manuscript translation of Hauptmann’s Michael Kramer, the stage directions of which were written in purple ink, and a little sheaf of papers held together by a brass pin. In these sheets a sentence was inscribed from time to time and, in an ironical moment, the headline of an advertisement for Bile Beans had been pasted on to the first sheet. On lifting the lid of the desk a faint fragrance escaped, the fragrance of new cedarwood pencils or of a bottle of gum or of an overripe apple which might have been left there and forgotten.

Mr. Duffy abhorred anything which betokened physical or mental disorder. A medival doctor would have called him saturnine. His face, which carried the entire tale of his years, was of the brown tint of Dublin streets. On his long and rather large head grew dry black hair and a tawny moustache did not quite cover an unamiable mouth. His cheekbones also gave his face a harsh character; but there was no harshness in the eyes which, looking at the world from under their tawny eyebrows, gave the impression of a man ever alert to greet a redeeming instinct in others but often disappointed. He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glasses. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a predicate in the past tense. He never gave alms to beggars and walked firmly, carrying a stout hazel.

He had been for many years cashier of a private bank in Baggot Street. Every morning he came in from Chapelizod by tram. At midday he went to Dan Burke’s and took his lunch, a bottle of lager beer and a small trayful of arrowroot biscuits. At four o’clock he was set free. He dined in an eating-house in George’s Street where he felt himself safe from the society of Dublin’s gilded youth and where there was a certain plain honesty in the bill of fare. His evenings were spent either before his landlady’s piano or roaming about the outskirts of the city. His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.

He had neither companions nor friends, church nor creed. He lived his spiritual life without any communion with others, visiting his relatives at Christmas and escorting them to the cemetery when they died. He performed these two social duties for old dignity’s sake but conceded nothing further to the conventions which regulate the civic life. He allowed himself to think that in certain circumstances he would rob his hank but, as these circumstances never arose, his life rolled out evenly, an adventureless tale.

One evening he found himself sitting beside two ladies in the Rotunda. The house, thinly peopled and silent, gave distressing prophecy of failure. The lady who sat next him looked round at the deserted house once or twice and then said:

“What a pity there is such a poor house tonight! It’s so hard on people to have to sing to empty benches.”

He took the remark as an invitation to talk. He was surprised that she seemed so little awkward. While they talked he tried to fix her permanently in his memory. When he learned that the young girl beside her was her daughter he judged her to be a year or so younger than himself. Her face, which must have been handsome, had remained intelligent. It was an oval face with strongly marked features. The eyes were very dark blue and steady. Their gaze began with a defiant note but was confused by what seemed a deliberate swoon of the pupil into the iris, revealing for an instant a temperament of great sensibility. The pupil reasserted itself quickly, this half-disclosed nature fell again under the reign of prudence, and her astrakhan jacket, moulding a bosom of a certain fullness, struck the note of defiance more definitely.

He met her again a few weeks afterwards at a concert in Earlsfort Terrace and seized the moments when her daughter’s attention was diverted to become intimate. She alluded once or twice to her husband but her tone was not such as to make the allusion a warning. Her name was Mrs. Sinico. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather had come from Leghorn. Her husband was captain of a mercantile boat plying between Dublin and Holland; and they had one child.

Meeting her a third time by accident he found courage to make an appointment. She came. This was the first of many meetings; they met always in the evening and chose the most quiet quarters for their walks together. Mr. Duffy, however, had a distaste for underhand ways and, finding that they were compelled to meet stealthily, he forced her to ask him to her house. Captain Sinico encouraged his visits, thinking that his daughter’s hand was in question. He had dismissed his wife so sincerely from his gallery of pleasures that he did not suspect that anyone else would take an interest in her. As the husband was often away and the daughter out giving music lessons Mr. Duffy had many opportunities of enjoying the lady’s society. Neither he nor she had had any such adventure before and neither was conscious of any incongruity. Little by little he entangled his thoughts with hers. He lent her books, provided her with ideas, shared his intellectual life with her. She listened to all.

Sometimes in return for his theories she gave out some fact of her own life. With almost maternal solicitude she urged him to let his nature open to the full: she became his confessor. He told her that for some time he had assisted at the meetings of an Irish Socialist Party where he had felt himself a unique figure amidst a score of sober workmen in a garret lit by an inefficient oil-lamp. When the party had divided into three sections, each under its own leader and in its own garret, he had discontinued his attendances. The workmen’s discussions, he said, were too timorous; the interest they took in the question of wages was inordinate. He felt that they were hard-featured realists and that they resented an exactitude which was the produce of a leisure not within their reach. No social revolution, he told her, would be likely to strike Dublin for some centuries.

She asked him why did he not write out his thoughts. For what, he asked her, with careful scorn. To compete with phrasemongers, incapable of thinking consecutively for sixty seconds? To submit himself to the criticisms of an obtuse middle class which entrusted its morality to policemen and its fine arts to impresarios?

He went often to her little cottage outside Dublin; often they spent their evenings alone. Little by little, as their thoughts entangled, they spoke of subjects less remote. Her companionship was like a warm soil about an exotic. Many times she allowed the dark to fall upon them, refraining from lighting the lamp. The dark discreet room, their isolation, the music that still vibrated in their ears united them. This union exalted him, wore away the rough edges of his character, emotionalised his mental life. Sometimes he caught himself listening to the sound of his own voice. He thought that in her eyes he would ascend to an angelical stature; and, as he attached the fervent nature of his companion more and more closely to him, he heard the strange impersonal voice which he recognised as his own, insisting on the soul’s incurable loneliness. We cannot give ourselves, it said: we are our own. The end of these discourses was that one night during which she had shown every sign of unusual excitement, Mrs. Sinico caught up his hand passionately and pressed it to her cheek.

Mr. Duffy was very much surprised. Her interpretation of his words disillusioned him. He did not visit her for a week, then he wrote to her asking her to meet him. As he did not wish their last interview to be troubled by the influence of their ruined confessional they meet in a little cakeshop near the Parkgate. It was cold autumn weather but in spite of the cold they wandered up and down the roads of the Park for nearly three hours. They agreed to break off their intercourse: every bond, he said, is a bond to sorrow. When they came out of the Park they walked in silence towards the tram; but here she began to tremble so violently that, fearing another collapse on her part, he bade her good-bye quickly and left her. A few days later he received a parcel containing his books and music.

Four years passed. Mr. Duffy returned to his even way of life. His room still bore witness of the orderliness of his mind. Some new pieces of music encumbered the music-stand in the lower room and on his shelves stood two volumes by Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra and The Gay Science. He wrote seldom in the sheaf of papers which lay in his desk. One of his sentences, written two months after his last interview with Mrs. Sinico, read: Love between man and man is impossible because there must not be sexual intercourse and friendship between man and woman is impossible because there must be sexual intercourse. He kept away from concerts lest he should meet her. His father died; the junior partner of the bank retired. And still every morning he went into the city by tram and every evening walked home from the city after having dined moderately in George’s Street and read the evening paper for dessert.

One evening as he was about to put a morsel of corned beef and cabbage into his mouth his hand stopped. His eyes fixed themselves on a paragraph in the evening paper which he had propped against the water-carafe. He replaced the morsel of food on his plate and read the paragraph attentively. Then he drank a glass of water, pushed his plate to one side, doubled the paper down before him between his elbows and read the paragraph over and over again. The cabbage began to deposit a cold white grease on his plate. The girl came over to him to ask was his dinner not properly cooked. He said it was very good and ate a few mouthfuls of it with difficulty. Then he paid his bill and went out.

He walked along quickly through the November twilight, his stout hazel stick striking the ground regularly, the fringe of the buff Mail peeping out of a side-pocket of his tight reefer overcoat. On the lonely road which leads from the Parkgate to Chapelizod he slackened his pace. His stick struck the ground less emphatically and his breath, issuing irregularly, almost with a sighing sound, condensed in the wintry air. When he reached his house he went up at once to his bedroom and, taking the paper from his pocket, read the paragraph again by the failing light of the window. He read it not aloud, but moving his lips as a priest does when he reads the prayers Secreto. This was the paragraph:

DEATH OF A LADY AT SYDNEY PARADE

A PAINFUL CASE

Today at the City of Dublin Hospital the Deputy Coroner (in the absence of Mr. Leverett) held an inquest on the body of Mrs. Emily Sinico, aged forty-three years, who was killed at Sydney Parade Station yesterday evening. The evidence showed that the deceased lady, while attempting to cross the line, was knocked down by the engine of the ten o’clock slow train from Kingstown, thereby sustaining injuries of the head and right side which led to her death.

James Lennon, driver of the engine, stated that he had been in the employment of the railway company for fifteen years. On hearing the guard’s whistle he set the train in motion and a second or two afterwards brought it to rest in response to loud cries. The train was going slowly.

P. Dunne, railway porter, stated that as the train was about to start he observed a woman attempting to cross the lines. He ran towards her and shouted, but, before he could reach her, she was caught by the buffer of the engine and fell to the ground.

A juror. “You saw the lady fall?”

Witness. “Yes.”

Police Sergeant Croly deposed that when he arrived he found the deceased lying on the platform apparently dead. He had the body taken to the waiting-room pending the arrival of the ambulance.

Constable 57 corroborated.

Dr. Halpin, assistant house surgeon of the City of Dublin Hospital, stated that the deceased had two lower ribs fractured and had sustained severe contusions of the right shoulder. The right side of the head had been injured in the fall. The injuries were not sufficient to have caused death in a normal person. Death, in his opinion, had been probably due to shock and sudden failure of the heart’s action.

Mr. H. B. Patterson Finlay, on behalf of the railway company, expressed his deep regret at the accident. The company had always taken every precaution to prevent people crossing the lines except by the bridges, both by placing notices in every station and by the use of patent spring gates at level crossings. The deceased had been in the habit of crossing the lines late at night from platform to platform and, in view of certain other circumstances of the case, he did not think the railway officials were to blame.

Captain Sinico, of Leoville, Sydney Parade, husband of the deceased, also gave evidence. He stated that the deceased was his wife. He was not in Dublin at the time of the accident as he had arrived only that morning from Rotterdam. They had been married for twenty-two years and had lived happily until about two years ago when his wife began to be rather intemperate in her habits.

Miss Mary Sinico said that of late her mother had been in the habit of going out at night to buy spirits. She, witness, had often tried to reason with her mother and had induced her to join a League. She was not at home until an hour after the accident. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence and exonerated Lennon from all blame.

The Deputy Coroner said it was a most painful case, and expressed great sympathy with Captain Sinico and his daughter. He urged on the railway company to take strong measures to prevent the possibility of similar accidents in the future. No blame attached to anyone.

Mr. Duffy raised his eyes from the paper and gazed out of his window on the cheerless evening landscape. The river lay quiet beside the empty distillery and from time to time a light appeared in some house on the Lucan road. What an end! The whole narrative of her death revolted him and it revolted him to think that he had ever spoken to her of what he held sacred. The threadbare phrases, the inane expressions of sympathy, the cautious words of a reporter won over to conceal the details of a commonplace vulgar death attacked his stomach. Not merely had she degraded herself; she had degraded him. He saw the squalid tract of her vice, miserable and malodorous. His soul’s companion! He thought of the hobbling wretches whom he had seen carrying cans and bottles to be filled by the barman. Just God, what an end! Evidently she had been unfit to live, without any strength of purpose, an easy prey to habits, one of the wrecks on which civilisation has been reared. But that she could have sunk so low! Was it possible he had deceived himself so utterly about her? He remembered her outburst of that night and interpreted it in a harsher sense than he had ever done. He had no difficulty now in approving of the course he had taken.

As the light failed and his memory began to wander he thought her hand touched his. The shock which had first attacked his stomach was now attacking his nerves. He put on his overcoat and hat quickly and went out. The cold air met him on the threshold; it crept into the sleeves of his coat. When he came to the public-house at Chapelizod Bridge he went in and ordered a hot punch.

The proprietor served him obsequiously but did not venture to talk. There were five or six workingmen in the shop discussing the value of a gentleman’s estate in County Kildare They drank at intervals from their huge pint tumblers and smoked, spitting often on the floor and sometimes dragging the sawdust over their spits with their heavy boots. Mr. Duffy sat on his stool and gazed at them, without seeing or hearing them. After a while they went out and he called for another punch. He sat a long time over it. The shop was very quiet. The proprietor sprawled on the counter reading the Herald and yawning. Now and again a tram was heard swishing along the lonely road outside.

As he sat there, living over his life with her and evoking alternately the two images in which he now conceived her, he realised that she was dead, that she had ceased to exist, that she had become a memory. He began to feel ill at ease. He asked himself what else could he have done. He could not have carried on a comedy of deception with her; he could not have lived with her openly. He had done what seemed to him best. How was he to blame? Now that she was gone he understood how lonely her life must have been, sitting night after night alone in that room. His life would be lonely too until he, too, died, ceased to exist, became a memory, if anyone remembered him.

It was after nine o’clock when he left the shop. The night was cold and gloomy. He entered the Park by the first gate and walked along under the gaunt trees. He walked through the bleak alleys where they had walked four years before. She seemed to be near him in the darkness. At moments he seemed to feel her voice touch his ear, her hand touch his. He stood still to listen. Why had he withheld life from her? Why had he sentenced her to death? He felt his moral nature falling to pieces.

When he gained the crest of the Magazine Hill he halted and looked along the river towards Dublin, the lights of which burned redly and hospitably in the cold night. He looked down the slope and, at the base, in the shadow of the wall of the Park, he saw some human figures lying. Those venal and furtive loves filled him with despair. He gnawed the rectitude of his life; he felt that he had been outcast from life’s feast. One human being had seemed to love him and he had denied her life and happiness: he had sentenced her to ignominy, a death of shame. He knew that the prostrate creatures down by the wall were watching him and wished him gone. No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast. He turned his eyes to the grey gleaming river, winding along towards Dublin. Beyond the river he saw a goods train winding out of Kingsbridge Station, like a worm with a fiery head winding through the darkness, obstinately and laboriously. It passed slowly out of sight; but still he heard in his ears the laborious drone of the engine reiterating the syllables of her name.

He turned back the way he had come, the rhythm of the engine pounding in his ears. He began to doubt the reality of what memory told him. He halted under a tree and allowed the rhythm to die away. He could not feel her near him in the darkness nor her voice touch his ear. He waited for some minutes listening. He could hear nothing: the night was perfectly silent. He listened again: perfectly silent. He felt that he was alone.

James Joyce: A Painful Case

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

foto joep eijkens

Esther Porcelijn

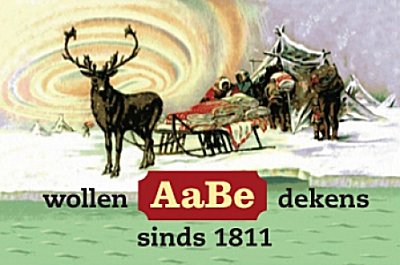

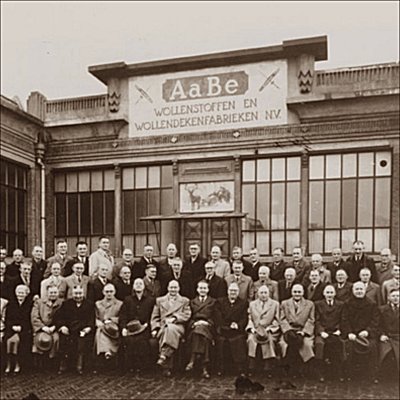

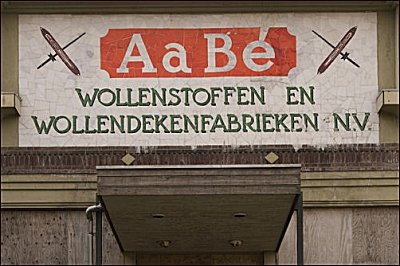

Aabe, Weeft Getrouw

(AaBe, Textielfabriek Tilburg)

Weefgetouw, oorverdovende patronen

Van draden los naar vast

Waar personeel gepast

In gekleurde overalls hun rangen tonen.

Aandraaien, kamrijgen, rietsteken en draadmaken

De beweging rijgt zich door de mensen

Die allen delen in hun wensen

Van goed salaris en goede zaken.

Na de prikkaart in de prikklok

Gaat ieder naar zijn plaats

Geen minuut te laat

Niemand wil ’t met de baas aan de stok.

De heren van den Bergh als directeur

Zijn heren van gezag

Een wekelijks bezoek brengt

De werkvloer in bedrijviger humeur.

“Samenwerking schept vreugde en trots”

De ezels zijn geketend

Maar weten wat dit betekent:

Naar links en dán naar rechts, dat is ’t vlotst.

De ruimte, een modern juweel

Het nieuwste netste schoonste

Waar orde ’t gewoonste

Zonder ouderwets gekrakeel.

Eindeloze ruimte, de centrale gang

Als ader door de bedrijvigheid

Rechte vormen en openheid

En grote duidelijkheidsdrang

Hier scheppen mensen bewust

Reinheid, en met regelmaat

Als bijen in een honingraat

Hier weeft men goede nachtrust.

Als plots het dekbed de wol

De das heeft omgedaan.

Het gebouw wordt ontdaan

Van zijn jarenlange rol.

De eerste barsten beginnen te komen

De laatste man prikt kaart in klok

Nog één keer klanken in de nok

Nooit meer jonge jongensdromen.

Brokkelende stenen

Klimop langs metalen palen

Leegte komt zijn ruimte halen.

Geen herkenning, enkel vreemden.

De structuur ontsluiert zich traag

De bedrading toont zich ook

Vervlochten met een betonnen strook

Soms is binnen of buiten vaag.

De draden en de organen van de structuur

Weven alles samen tot geheel

Zodat men bij het kijken veel

Kan herkennen in een muur.

Het gebouw geeft haar geheimen bloot

We kijken in de kieren

En zien de tijd vieren

Dat ze immer nieuwheid doodt.

Je zou haar skelet willen toedekken

Zoo naakt en zoo koud

Als een arme vrouw te oud

Om haar ledematen uit te rekken.

Gelijkend onszelf zijn de delen samen één

Wij bestaan uit losse stukken

Waar zit dan het geluk en

Wie houdt ons allen op de been?

Het weven van ons samen tot één deel

Gebeurt niet vanzelf en zonder kracht

En wie te lang wacht

Blijft over zonder al te veel.

Zoals het skelet van een gebouw

Onszelf kan representeren

Wij spiegelen elkaar, laten we dat eren

Jij weeft mij en ik weef jouw.

De bedrading zijn losse delen die ieder

Nodig zijn voor overleven

Het gaat niet om het korte en het even

Het gaat niet om de hoogste bieder.

Wie schoonheid ziet herkent ’t acuut.

Wie geld ziet zal gaan kwijlen

En wie wil schoonheid laten veilen?

Een oud gebouw met een nieuw debuut?

Nieuwe plannen voor dit complex

Duurzaam herbestemmen

Maar het skelet blijvend herkennen

In het mooist, het duurst, het gekst.

Nu is de oorverdovende stilte begonnen

Een lichaam heeft een beweger nodig

Saamhorigheid lijkt overbodig

Maar zonder wever rest enkel het verstommen.

De oude vrouw is broos en ijl

Ze zucht onder haar pilaren

Ze wil enkel dat haar jaren

Terugkeren in een nieuwe stijl.

De oude vrouw was excentriek

Nu beeft ze aan haar koude draden

Misschien dat we bij de Eskimo’s nog dekens kunnen halen

Ze voorkomen immers reumatiek.

Aabe; weeft getrouw is geschreven door stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn voor het Erasmusfestival 2011. AaBe of voluit: Albert van den Bergh was gevestigd aan de Hoevenseweg in Tilburg. De fabriek voor wollen dekens, die een rendier als logo had, ging in 2008, na een reeks van reorganisaties, failliet.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Virginia Woolf

How Should One Read a Book?

In the first place, I want to emphasize the note of interrogation at the end of my title. Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.

But to enjoy freedom, if the platitude is pardonable, we have of course to control ourselves. We must not squander our powers, helplessly and ignorantly, squirting half the house in order to water a single rose-bush; we must train them, exactly and powerfully, here on the very spot. This, it may be, is one of the first difficulties that faces us in a library. What is “the very spot?” There may well seem to be nothing but a conglomeration and huddle of confusion. Poems and novels, histories and memories, dictionaries and blue-books; books written in all languages by men and women of all tempers, races, and ages jostle each other on the shelf. And outside the donkey brays, the women gossip at the pump, the colts gallop across the fields. Where are we to begin? How are we to bring order into this multitudinous chaos and so get the deepest and widest pleasure from what we read?

It is simple enough to say that since books have classes—fiction, biography, poetry—we should separate them and take from each what it is right that each should give us. Yet few people ask from books what books can give us. Most commonly we come to books with blurred and divided minds, asking of fiction that it shall be true, of poetry that it shall be false, of biography that it shall be flattering, of history that it shall enforce our own prejudices. If we could banish all such preconceptions when we read, that would be an admirable beginning. Do not dictate to your author; try to become him. Be his fellow-worker and accomplice. If you hang back, and reserve and criticize at first, you are preventing yourself from getting the fullest possible value from what you read. But if you open your mind as widely as possible, then signs and hints of almost imperceptible fineness, from the twist and turn of the first sentences, will bring you into the presence of a human being unlike any other. Steep yourself in this, acquaint yourself with this, and soon you will find that your author is giving you, or attempting to give you, something far more definite. The thirty-chapters of a novel—if we consider how to read a novel first—are an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building: but words are more impalpable than bricks; reading is a longer and more complicated process than seeing. Perhaps the quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiment with the dangers and difficulties of words. Recall, then, some event that has left a distinct impression on you— how at the corner of the street, perhaps, you passed two people talking. A tree shook; an electric light danced; the tone of the talk was comic, but also tragic; a whole vision, an entire conception, seemed contained in that moment.

But when you attempt to reconstruct it in words, you will find that it breaks into a thousand conflicting impressions. Some must be subdued; others emphasized; in the process you will lose, probably, all grasp upon the emotion itself. Then turn from your blurred and littered pages to the opening pages of some great novelist—Defoe, Jane Austen, Hardy. Now you will be better able to appreciate their mastery. It is not merely that we are in the presence of a different person—Defoe, Jane Austen, or Thomas Hardy—but that we are living in a different world. Here, in Robinson Crusoe, we are trudging a plain high road; one thing happens after another; the fact and the order of the fact is enough. But if the open air and adventure mean everything to Defoe they mean nothing to Jane Austen. Hers is the drawing-room, and people talking, and by the many mirrors of their talk revealing their characters. And if, when we have accustomed ourselves to the drawing-room and its reflections, we turn to Hardy, we are once more spun round. The moors are round us and the stars are above our heads. The other side of the mind is now exposed—the dark side that comes uppermost in solitude, not the light side that shows in company. Our relations are not towards people, but towards Nature and destiny. Yet different as these worlds are, each is consistent with itself. The maker of each is careful to observe the laws of his own perspective, and however great a strain they may put upon us they will never confuse us, as lesser writers so frequently do, by introducing two different kinds of reality into the same book. Thus to go from one great novelist to another—from Jane Austen to Hardy, from Peacock to Trollope, from Scott to Meredith—is to be wrenched and uprooted; to be thrown this way and then that. To read a novel is a difficult and complex art. You must be capable not only of great fineness of perception, but of great boldness of imagination if you are going to make use of all that the novelist—the great artist—gives you.

But a glance at the heterogeneous company on the shelf will show you that writers are very seldom “great artists;” far more often a book makes no claim to be a work of art at all. These biographies and autobiographies, for example, lives of great men, of men long dead and forgotten, that stand cheek by jowl with the novels and poems, are we to refuse to read them because they are not “art?” Or shall we read them, but read them in a different way, with a different aim? Shall we read them in the first place to satisfy that curiosity which possesses us sometimes when in the evening we linger in front of a house where the lights are lit and the blinds not yet drawn, and each floor of the house shows us a different section of human life in being? Then we are consumed with curiosity about the lives of these people—the servants gossiping, the gentlemen dining, the girl dressing for a party, the old woman at the window with her knitting. Who are they, what are they, what are their names, their occupations, their thoughts, and adventures?

Biographies and memoirs answer such questions, light up innumerable such houses; they show us people going about their daily affairs, toiling, failing, succeeding, eating, hating, loving, until they die. And sometimes as we watch, the house fades and the iron railings vanish and we are out at sea; we are hunting, sailing, fighting; we are among savages and soldiers; we are taking part in great campaigns. Or if we like to stay here in England, in London, still the scene changes; the street narrows; the house becomes small, cramped, diamond-paned, and malodorous. We see a poet, Donne, driven from such a house because the walls were so thin that when the children cried their voices cut through them. We can follow him, through the paths that lie in the pages of books, to Twickenham; to Lady Bedford’s Park, a famous meeting-ground for nobles and poets; and then turn our steps to Wilton, the great house under the downs, and hear Sidney read the Arcadia to his sister; and ramble among the very marshes and see the very herons that figure in that famous romance; and then again travel north with that other Lady Pembroke, Anne Clifford, to her wild moors, or plunge into the city and control our merriment at the sight of Gabriel Harvey in his black velvet suit arguing about poetry with Spenser. Nothing is more fascinating than to grope and stumble in the alternate darkness and splendor of Elizabethan London. But there is no staying there. The Temples and the Swifts, the Harleys and the St Johns beckon us on; hour upon hour can be spent disentangling their quarrels and deciphering their characters; and when we tire of them we can stroll on, past a lady in black wearing diamonds, to Samuel Johnson and Goldsmith and Garrick; or cross the channel, if we like, and meet Voltaire and Diderot, Madame du Deffand; and so back to England and Twickenham—how certain places repeat themselves and certain names!—where Lady Bedford had her Park once and Pope lived later, to Walpole’s home at Strawberry Hill. But Walpole introduces us to such a swarm of new acquaintances, there are so many houses to visit and bells to ring that we may well hesitate for a moment, on the Miss Berrys’ doorstep, for example, when behold, up comes Thackeray; he is the friend of the woman whom Walpole loved; so that merely by going from friend to friend, from garden to garden, from house to house, we have passed from one end of English literature to another and wake to find ourselves here again in the present, if we can so differentiate this moment from all that have gone before. This, then, is one of the ways in which we can read these lives and letters; we can make them light up the many windows of the past; we can watch the famous dead in their familiar habits and fancy sometimes that we are very close and can surprise their secrets, and sometimes we may pull out a play or a poem that they have written and see whether it reads differently in the presence of the author. But this again rouses other questions. How far, we must ask ourselves, is a book influenced by its writer’s life—how far is it safe to let the man interpret the writer? How far shall we resist or give way to the sympathies and antipathies that the man himself rouses in us—so sensitive are words, so receptive of the character of the author? These are questions that press upon us when we read lives and letters, and we must answer them for ourselves, for nothing can be more fatal than to be guided by the preferences of others in a matter so personal.

But also we can read such books with another aim, not to throw light on literature, not to become familiar with famous people, but to refresh and exercise our own creative powers. Is there not an open window on the right hand of the bookcase? How delightful to stop reading and look out! How stimulating the scene is, in its unconsciousness, its irrelevance, its perpetual movement—the colts galloping round the field, the woman filling her pail at the well, the donkey throwing back his head and emitting his long, acrid moan. The greater part of any library is nothing but the record of such fleeting moments in the lives of men, women, and donkeys. Every literature, as it grows old, has its rubbish-heap, its record of vanished moments and forgotten lives told in faltering and feeble accents that have perished. But if you give yourself up to the delight of rubbish-reading you will be surprised, indeed you will be overcome, by the relics of human life that have been cast out to molder. It may be one letter—but what a vision it gives! It may be a few sentences—but what vistas they suggest! Sometimes a whole story will come together with such beautiful humor and pathos and completeness that it seems as if a great novelist had been at work, yet it is only an old actor, Tate Wilkinson, remembering the strange story of Captain Jones; it is only a young subaltern serving under Arthur Wellesley and falling in love with a pretty girl at Lisbon; it is only Maria Allen letting fall her sewing in the empty drawing-room and sighing how she wishes she had taken Dr Burney’s good advice and had never eloped with her Rishy. None of this has any value; it is negligible in the extreme; yet how absorbing it is now and again to go through the rubbish-heaps and find rings and scissors and broken noses buried in the huge past and try to piece them together while the colt gallops round the field, the woman fills her pail at the well, and the donkey brays.

But we tire of rubbish-reading in the long run. We tire of searching for what is needed to complete the half-truth which is all that the Wilkinsons, the Bunburys and the Maria Allens are able to offer us. They had not the artist’s power of mastering and eliminating; they could not tell the whole truth even about their own lives; they have disfigured the story that might have been so shapely. Facts are all that they can offer us, and facts are a very inferior form of fiction. Thus the desire grows upon us to have done with half-statements and approximations; to cease from searching out the minute shades of human character, to enjoy the greater abstractness, the purer truth of fiction. Thus we create the mood, intense and generalized, unaware of detail, but stressed by some regular, recurrent beat, whose natural expression is poetry; and that is the time to read poetry when we are almost able to write it.

Western wind, when wilt thou blow?

The small rain down can rain.

Christ, if my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

The impact of poetry is so hard and direct that for the moment there is no other sensation except that of the poem itself. What profound depths we visit then—how sudden and complete is our immersion! There is nothing here to catch hold of; nothing to stay us in our flight. The illusion of fiction is gradual; its effects are prepared; but who when they read these four lines stops to ask who wrote them, or conjures up the thought of Donne’s house or Sidney’s secretary; or enmeshes them in the intricacy of the past and the succession of generations? The poet is always our contemporary. Our being for the moment is centered and constricted, as in any violent shock of personal emotion. Afterwards, it is true, the sensation begins to spread in wider rings through our minds; remoter senses are reached; these begin to sound and to comment and we are aware of echoes and reflections. The intensity of poetry covers an immense range of emotion. We have only to compare the force and directness of

I shall fall like a tree, and find my grave,

Only remembering that I grieve,

with the wavering modulation of

Minutes are numbered by the fall of sands,

As by an hour glass; the span of time

Doth waste us to our graves, and we look on it;

An age of pleasure, revelled out, comes home

At last, and ends in sorrow; but the life,

Weary of riot, numbers every sand,

Wailing in sighs, until the last drop down,

So to conclude calamity in rest

or place the meditative calm of

whether we be young or old,

Our destiny, our being’s heart and home,

Is with infinitude, and only there;

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And effort evermore about to be,

beside the complete and inexhaustible loveliness of

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And nowhere did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside—

or the splendid fantasy of

And the woodland haunter

Shall not cease to saunter

When, far down some glade,

Of the great world’s burning,

One soft flame upturning

Seems to his discerning,

Crocus in the shade,

to bethink us of the varied art of the poet; his power to make us at once actors and spectators; his power to run his hand into characters as if it were a glove, and be Falstaff or Lear; his power to condense, to widen, to state, once and for ever.

“We have only to compare”—with those words the cat is out of the bag, and the true complexity of reading is admitted. The first process, to receive impressions with the utmost understanding, is only half the process of reading; it must be completed, if we are to get the whole pleasure from a book, by another. We must pass judgment upon these multitudinous impressions; we must make of these fleeting shapes one that is hard and lasting. But not directly. Wait for the dust of reading to settle; for the conflict and the questioning to die down; walk, talk, pull the dead petals from a rose, or fall asleep. Then suddenly without our willing it, for it is thus that Nature undertakes these transitions, the book will return, but differently. It will float to the top of the mind as a whole. And the book as a whole is different from the book received currently in separate phrases. Details now fit themselves into their places. We see the shape from start to finish; it is a barn, a pig-sty, or a cathedral. Now then we can compare book with book as we compare building with building. But this act of comparison means that our attitude has changed; we are no longer the friends of the writer, but his judges; and just as we cannot be too sympathetic as friends, so as judges we cannot be too severe. Are they not criminals, books that have wasted our time and sympathy; are they not the most insidious enemies of society, corrupters, defilers, the writers of false books, faked books, books that fill the air with decay and disease? Let us then be severe in our judgments; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind. There they hang in the mind the shapes of the books we have read solidified by the judgments we have passed on them—Robinson Crusoe, Emma The Return of the Native. Compare the novels with these—even the latest and least of novels has a right to be judged with the best. And so with poetry when the intoxication of rhythm has died down and the splendor of words has faded, a visionary shape will return to us and this must be compared with Lear, with Phèdre, with The Prelude; or if not with these, with whatever is the best or seems to us to be the best in its own kind. And we may be sure that the newness of new poetry and fiction is its most superficial quality and that we have only to alter slightly, not to recast, the standards by which we have judged the old.

It would be foolish, then, to pretend that the second part of reading, to judge, to compare, is as simple as the first—to open the mind wide to the fast flocking of innumerable impressions. To continue reading without the book before you, to hold one shadow-shape against another, to have read widely enough and with enough understanding to make such comparisons alive and illuminating—that is difficult; it is still more difficult to press further and to say, “Not only is the book of this sort, but it is of this value; here it fails; here it succeeds; this is bad; that is good.” To carry out this part of a reader’s duty needs such imagination, insight, and learning that it is hard to conceive any one mind sufficiently endowed; impossible for the most self-confident to find more than the seeds of such powers in himself. Would it not be wiser, then, to remit this part of reading and to allow the critics, the gowned and furred authorities of the library, to decide the question of the book’s absolute value for us? Yet how impossible! We may stress the value of sympathy; we may try to sink our own identity as we read. But we know that we cannot sympathize wholly or immerse ourselves wholly; there is always a demon in us who whispers, “I hate, I love,” and we cannot silence him. Indeed, it is precisely because we hate and we love that our relation with the poets and novelists is so intimate that we find the presence of another person intolerable. And even if the results are abhorrent and our judgments are wrong, still our taste, the nerve of sensation that sends shocks through us, is our chief illuminant; we learn through feeling; we cannot suppress our own idiosyncrasy without impoverishing it. But as time goes on perhaps we can train our taste; perhaps we can make it submit to some control. When it has fed greedily and lavishly upon books of all sorts—poetry, fiction, history, biography—and has stopped reading and looked for long spaces upon the variety, the incongruity of the living world, we shall find that it is changing a little; it is not so greedy, it is more reflective. It will begin to bring us not merely judgments on particular books, but it will tell us that there is a quality common to certain books. Listen, it will say, what shall we call this? And it will read us perhaps Lear and then perhaps the Agamemnon in order to bring out that common quality. Thus, with our taste to guide us, we shall venture beyond the particular book in search of qualities that group books together; we shall give them names and thus frame a rule that brings order into our perceptions. We shall gain a further and a rarer pleasure from that discrimination. But as a rule only lives when it is perpetually broken by contact with the books themselves—nothing is easier and more stultifying than to make rules which exists out of touch with facts, in a vacuum—now at last, in order to steady ourselves in this difficult attempt, it may be well to turn to the very rare writers who are able to enlighten us upon literature as an art. Coleridge and Dryden and Johnson, in their considered criticism, the poets and novelists themselves in their unconsidered sayings, are often surprisingly relevant; they light up and solidify the vague ideas that have been tumbling in the misty depths of our minds. But they are only able to help us if we come to them laden with questions and suggestions won honestly in the course of our own reading. They can do nothing for us if we herd ourselves under their authority and lie down like sheep in the shade of a hedge. We can only understand their ruling when it comes in conflict with our own and vanquishes it.

If this is so, if to read a book as it should be read calls for the rarest qualities of imagination, insight, and judgment, and you may perhaps conclude that literature is a very complex art and that it is unlikely that we shall be able, even after a lifetime of reading, to make any valuable contribution to its criticism. We must remain readers; we shall not put on the further glory that belongs to those rare beings who are also critics. But still we have our responsibilities as readers and even our importance. The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work. An influence is created which tells upon them even if it never finds its way into print. And that influence, if it were well instructed, vigorous and individual and sincere, might be of great value now when criticism is necessarily in abeyance; when books pass in review like the procession of animals in a shooting gallery, and the critic has only one second in which to load and aim and shoot and may well be pardoned if he mistakes rabbits for tigers, eagles for barndoor fowls, or misses altogether and wastes his shot upon some peaceful cow grazing in a further field. If behind the erratic gunfire of the press the author felt that there was another kind of criticism, the opinion of people reading for the love of reading, slowly and unprofessionally, and judging with great sympathy and yet with great severity, might this not improve the quality of his work? And if by our means books were to become stronger, richer, and more varied, that would be an end worth reaching.

Yet who reads to bring about an end, however desirable? Are there not some pursuits that we practice because they are good in themselves, and some pleasures that are final? And is not this among them? I have sometimes dreamt, at least that when the Day of judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards—their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble—the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

Virgina Woolf

(The Common Reader, Second Series 1926)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Libraries in Literature, The Art of Reading, Woolf, Virginia

17 maart 2012

Tilburgs literatuur- en

theaterfestival TILT

Wegens groot succes geprolongeerd: TiLT. Een festival dat bol staat van literatuur, muziek, theater en beeldende kunst. Verrassende cross-overs, spraakmakende interviews, hilarische acts en een vette band. Vorig jaar was de eerste editie stijf uitverkocht. Op zaterdag 17 maart gaat De NWE Vorst in Tilburg opnieuw op TiLT.

In de Boekenweek komen de letteren tot leven. En hoe! Het Zuidelijk Toneel opent het bal, in een verrassende combi met Fontysstudenten. Robert Vuijsje komt langs met zijn nieuwe roman Beste Vriend. AKO-literatuurprijswinnares Marente de Moor zal er zijn. Maar ook absurdist Gummbah met zijn Net niet verschenen boeken, Henk van Straten met zijn Superlul, en stadsdichteres Esther Porcelijn met vers Tilburgs vlees.

Overal in De NWE Vorst zijn optredens. Bezoekers vinden vier zalen vol proza, poëzie, beeldende kunst, muziek en theater. Er zijn columns van Hanna Bervoets (Volkskrant) en Renske de Greef (nrc-next) en liedjes van Koek & Trommel. Er is Stine Jensen met filosofie over Facebook, A.H.J. Dautzenberg met spraakmakende literatuur, een poëzieinstallatie van kunstenares Anouk van Reijen en nog veel meer. In de meeste gevallen gaat het om programma’s die speciaal voor TiLT zijn gemaakt. En dat alles wordt afgesloten met een swingende deejay en de boomende band The Kik.

Nieuw dit jaar is Kroeg op TiLT. Op vrijdag 16 maart, de avond vóór het festival, staan zes kroegen op de Korte Heuvel in het teken van de taal. Gedichten, muziek, dans, zang, verhalen, film, alles zal versmelten tot één uniek evenement. Een gratis crossoverprogramma vol Tilburgs talent, samengesteld door Studievereniging Animo van de Tilburg University.

TiLT vindt plaats in de Boekenweek, op zaterdag 17 maart, van 20.00 – 02.00 uur in theater De NWE Vorst in Tilburg. Tickets kosten € 17,50. Meer info: www.tilt.nu

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: A.H.J. Dautzenberg, Art & Literature News, Gummbah, MUSIC, Porcelijn, Esther, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg

Ivo van Leeuwen, 2011

Portret van Esther Porcelijn, actrice en stadsdichter van Tilburg

©ivovanleeuwen

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Ivo van Leeuwen, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature