Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

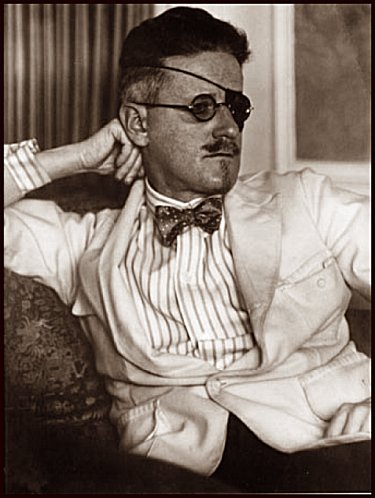

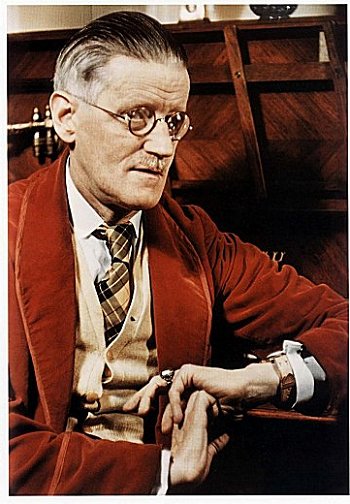

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

After The Race

The cars came scudding in towards Dublin, running evenly like pellets in the groove of the Naas Road. At the crest of the hill at Inchicore sightseers had gathered in clumps to watch the cars careering homeward and through this channel of poverty and inaction the Continent sped its wealth and industry. Now and again the clumps of people raised the cheer of the gratefully oppressed. Their sympathy, however, was for the blue cars, the cars of their friends, the French.

The French, moreover, were virtual victors. Their team had finished solidly; they had been placed second and third and the driver of the winning German car was reported a Belgian. Each blue car, therefore, received a double measure of welcome as it topped the crest of the hill and each cheer of welcome was acknowledged with smiles and nods by those in the car. In one of these trimly built cars was a party of four young men whose spirits seemed to be at present well above the level of successful Gallicism: in fact, these four young men were almost hilarious. They were Charles Segouin, the owner of the car; Andre Riviere, a young electrician of Canadian birth; a huge Hungarian named Villona and a neatly groomed young man named Doyle. Segouin was in good humour because he had unexpectedly received some orders in advance (he was about to start a motor establishment in Paris) and Riviere was in good humour because he was to be appointed manager of the establishment; these two young men (who were cousins) were also in good humour because of the success of the French cars. Villona was in good humour because he had had a very satisfactory luncheon; and besides he was an optimist by nature. The fourth member of the party, however, was too excited to be genuinely happy.

He was about twenty-six years of age, with a soft, light brown moustache and rather innocent-looking grey eyes. His father, who had begun life as an advanced Nationalist, had modified his views early. He had made his money as a butcher in Kingstown and by opening shops in Dublin and in the suburbs he had made his money many times over. He had also been fortunate enough to secure some of the police contracts and in the end he had become rich enough to be alluded to in the Dublin newspapers as a merchant prince. He had sent his son to England to be educated in a big Catholic college and had afterwards sent him to Dublin University to study law. Jimmy did not study very earnestly and took to bad courses for a while. He had money and he was popular; and he divided his time curiously between musical and motoring circles. Then he had been sent for a term to Cambridge to see a little life. His father, remonstrative, but covertly proud of the excess, had paid his bills and brought him home. It was at Cambridge that he had met Segouin. They were not much more than acquaintances as yet but Jimmy found great pleasure in the society of one who had seen so much of the world and was reputed to own some of the biggest hotels in France. Such a person (as his father agreed) was well worth knowing, even if he had not been the charming companion he was. Villona was entertaining also, a brilliant pianist, but, unfortunately, very poor.

The car ran on merrily with its cargo of hilarious youth. The two cousins sat on the front seat; Jimmy and his Hungarian friend sat behind. Decidedly Villona was in excellent spirits; he kept up a deep bass hum of melody for miles of the road The Frenchmen flung their laughter and light words over their shoulders and often Jimmy had to strain forward to catch the quick phrase. This was not altogether pleasant for him, as he had nearly always to make a deft guess at the meaning and shout back a suitable answer in the face of a high wind. Besides Villona’s humming would confuse anybody; the noise of the car, too.

Rapid motion through space elates one; so does notoriety; so does the possession of money. These were three good reasons for Jimmy’s excitement. He had been seen by many of his friends that day in the company of these Continentals. At the control Segouin had presented him to one of the French competitors and, in answer to his confused murmur of compliment, the swarthy face of the driver had disclosed a line of shining white teeth. It was pleasant after that honour to return to the profane world of spectators amid nudges and significant looks. Then as to money, he really had a great sum under his control. Segouin, perhaps, would not think it a great sum but Jimmy who, in spite of temporary errors, was at heart the inheritor of solid instincts knew well with what difficulty it had been got together. This knowledge had previously kept his bills within the limits of reasonable recklessness, and if he had been so conscious of the labour latent in money when there had been question merely of some freak of the higher intelligence, how much more so now when he was about to stake the greater part of his substance! It was a serious thing for him.

Of course, the investment was a good one and Segouin had managed to give the impression that it was by a favour of friendship the mite of Irish money was to be included in the capital of the concern. Jimmy had a respect for his father’s shrewdness in business matters and in this case it had been his father who had first suggested the investment; money to be made in the motor business, pots of money. Moreover Segouin had the unmistakable air of wealth. Jimmy set out to translate into days’ work that lordly car in which he sat. How smoothly it ran. In what style they had come careering along the country roads! The journey laid a magical finger on the genuine pulse of life and gallantly the machinery of human nerves strove to answer the bounding courses of the swift blue animal.

They drove down Dame Street. The street was busy with unusual traffic, loud with the horns of motorists and the gongs of impatient tram-drivers. Near the Bank Segouin drew up and Jimmy and his friend alighted. A little knot of people collected on the footpath to pay homage to the snorting motor. The party was to dine together that evening in Segouin’s hotel and, meanwhile, Jimmy and his friend, who was staying with him, were to go home to dress. The car steered out slowly for Grafton Street while the two young men pushed their way through the knot of gazers. They walked northward with a curious feeling of disappointment in the exercise, while the city hung its pale globes of light above them in a haze of summer evening.

In Jimmy’s house this dinner had been pronounced an occasion. A certain pride mingled with his parents’ trepidation, a certain eagerness, also, to play fast and loose for the names of great foreign cities have at least this virtue. Jimmy, too, looked very well when he was dressed and, as he stood in the hall giving a last equation to the bows of his dress tie, his father may have felt even commercially satisfied at having secured for his son qualities often unpurchaseable. His father, therefore, was unusually friendly with Villona and his manner expressed a real respect for foreign accomplishments; but this subtlety of his host was probably lost upon the Hungarian, who was beginning to have a sharp desire for his dinner.

The dinner was excellent, exquisite. Segouin, Jimmy decided, had a very refined taste. The party was increased by a young Englishman named Routh whom Jimmy had seen with Segouin at Cambridge. The young men supped in a snug room lit by electric candle lamps. They talked volubly and with little reserve. Jimmy, whose imagination was kindling, conceived the lively youth of the Frenchmen twined elegantly upon the firm framework of the Englishman’s manner. A graceful image of his, he thought, and a just one. He admired the dexterity with which their host directed the conversation. The five young men had various tastes and their tongues had been loosened. Villona, with immense respect, began to discover to the mildly surprised Englishman the beauties of the English madrigal, deploring the loss of old instruments. Riviere, not wholly ingenuously, undertook to explain to Jimmy the triumph of the French mechanicians. The resonant voice of the Hungarian was about to prevail in ridicule of the spurious lutes of the romantic painters when Segouin shepherded his party into politics. Here was congenial ground for all. Jimmy, under generous influences, felt the buried zeal of his father wake to life within him: he aroused the torpid Routh at last. The room grew doubly hot and Segouin’s task grew harder each moment: there was even danger of personal spite. The alert host at an opportunity lifted his glass to Humanity and, when the toast had been drunk, he threw open a window significantly.

That night the city wore the mask of a capital. The five young men strolled along Stephen’s Green in a faint cloud of aromatic smoke. They talked loudly and gaily and their cloaks dangled from their shoulders. The people made way for them. At the corner of Grafton Street a short fat man was putting two handsome ladies on a car in charge of another fat man. The car drove off and the short fat man caught sight of the party.

“Andre.”

“It’s Farley!”

A torrent of talk followed. Farley was an American. No one knew very well what the talk was about. Villona and Riviere were the noisiest, but all the men were excited. They got up on a car, squeezing themselves together amid much laughter. They drove by the crowd, blended now into soft colours, to a music of merry bells. They took the train at Westland Row and in a few seconds, as it seemed to Jimmy, they were walking out of Kingstown Station. The ticket-collector saluted Jimmy; he was an old man:

“Fine night, sir!”

It was a serene summer night; the harbour lay like a darkened mirror at their feet. They proceeded towards it with linked arms, singing Cadet Roussel in chorus, stamping their feet at every:

“Ho! Ho! Hohe, vraiment!”

They got into a rowboat at the slip and made out for the American’s yacht. There was to be supper, music, cards. Villona said with conviction:

“It is delightful!”

There was a yacht piano in the cabin. Villona played a waltz for Farley and Riviere, Farley acting as cavalier and Riviere as lady. Then an impromptu square dance, the men devising original figures. What merriment! Jimmy took his part with a will; this was seeing life, at least. Then Farley got out of breath and cried “Stop!” A man brought in a light supper, and the young men sat down to it for form’s sake. They drank, however: it was Bohemian. They drank Ireland, England, France, Hungary, the United States of America. Jimmy made a speech, a long speech, Villona saying: “Hear! hear!” whenever there was a pause. There was a great clapping of hands when he sat down. It must have been a good speech. Farley clapped him on the back and laughed loudly. What jovial fellows! What good company they were!

Cards! cards! The table was cleared. Villona returned quietly to his piano and played voluntaries for them. The other men played game after game, flinging themselves boldly into the adventure. They drank the health of the Queen of Hearts and of the Queen of Diamonds. Jimmy felt obscurely the lack of an audience: the wit was flashing. Play ran very high and paper began to pass. Jimmy did not know exactly who was winning but he knew that he was losing. But it was his own fault for he frequently mistook his cards and the other men had to calculate his I.O.U.’s for him. They were devils of fellows but he wished they would stop: it was getting late. Someone gave the toast of the yacht The Belle of Newport and then someone proposed one great game for a finish.

The piano had stopped; Villona must have gone up on deck. It was a terrible game. They stopped just before the end of it to drink for luck. Jimmy understood that the game lay between Routh and Segouin. What excitement! Jimmy was excited too; he would lose, of course. How much had he written away? The men rose to their feet to play the last tricks. talking and gesticulating. Routh won. The cabin shook with the young men’s cheering and the cards were bundled together. They began then to gather in what they had won. Farley and Jimmy were the heaviest losers.

He knew that he would regret in the morning but at present he was glad of the rest, glad of the dark stupor that would cover up his folly. He leaned his elbows on the table and rested his head between his hands, counting the beats of his temples. The cabin door opened and he saw the Hungarian standing in a shaft of grey light:

“Daybreak, gentlemen!”

James Joyce: After the race

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Mother

Mr Holohan, assistant secretary of the Eire Abu Society, had been walking up and down Dublin for nearly a month, with his hands and pockets full of dirty pieces of paper, arranging about the series of concerts. He had a game leg and for this his friends called him Hoppy Holohan. He walked up and down constantly, stood by the hour at street corners arguing the point and made notes; but in the end it was Mrs. Kearney who arranged everything.

Miss Devlin had become Mrs. Kearney out of spite. She had been educated in a high-class convent, where she had learned French and music. As she was naturally pale and unbending in manner she made few friends at school. When she came to the age of marriage she was sent out to many houses, where her playing and ivory manners were much admired. She sat amid the chilly circle of her accomplishments, waiting for some suitor to brave it and offer her a brilliant life. But the young men whom she met were ordinary and she gave them no encouragement, trying to console her romantic desires by eating a great deal of Turkish Delight in secret. However, when she drew near the limit and her friends began to loosen their tongues about her, she silenced them by marrying Mr. Kearney, who was a bootmaker on Ormond Quay.

He was much older than she. His conversation, which was serious, took place at intervals in his great brown beard. After the first year of married life, Mrs. Kearney perceived that such a man would wear better than a romantic person, but she never put her own romantic ideas away. He was sober, thrifty and pious; he went to the altar every first Friday, sometimes with her, oftener by himself. But she never weakened in her religion and was a good wife to him. At some party in a strange house when she lifted her eyebrow ever so slightly he stood up to take his leave and, when his cough troubled him, she put the eider-down quilt over his feet and made a strong rum punch. For his part, he was a model father. By paying a small sum every week into a society, he ensured for both his daughters a dowry of one hundred pounds each when they came to the age of twenty-four. He sent the older daughter, Kathleen, to a good convent, where she learned French and music, and afterward paid her fees at the Academy. Every year in the month of July Mrs. Kearney found occasion to say to some friend:

“My good man is packing us off to Skerries for a few weeks.”

If it was not Skerries it was Howth or Greystones.

When the Irish Revival began to be appreciable Mrs. Kearney determined to take advantage of her daughter’s name and brought an Irish teacher to the house. Kathleen and her sister sent Irish picture postcards to their friends and these friends sent back other Irish picture postcards. On special Sundays, when Mr. Kearney went with his family to the pro-cathedral, a little crowd of people would assemble after mass at the corner of Cathedral Street. They were all friends of the Kearneys, musical friends or Nationalist friends; and, when they had played every little counter of gossip, they shook hands with one another all together, laughing at the crossing of so many hands, and said good-bye to one another in Irish. Soon the name of Miss Kathleen Kearney began to be heard often on people’s lips. People said that she was very clever at music and a very nice girl and, moreover, that she was a believer in the language movement. Mrs. Kearney was well content at this. Therefore she was not surprised when one day Mr. Holohan came to her and proposed that her daughter should be the accompanist at a series of four grand concerts which his Society was going to give in the Antient Concert Rooms. She brought him into the drawing-room, made him sit down and brought out the decanter and the silver biscuit-barrel. She entered heart and soul into the details of the enterprise, advised and dissuaded: and finally a contract was drawn up by which Kathleen was to receive eight guineas for her services as accompanist at the four grand concerts.

As Mr. Holohan was a novice in such delicate matters as the wording of bills and the disposing of items for a programme, Mrs. Kearney helped him. She had tact. She knew what artistes should go into capitals and what artistes should go into small type. She knew that the first tenor would not like to come on after Mr. Meade’s comic turn. To keep the audience continually diverted she slipped the doubtful items in between the old favourites. Mr. Holohan called to see her every day to have her advice on some point. She was invariably friendly and advising, homely, in fact. She pushed the decanter towards him, saying:

“Now, help yourself, Mr. Holohan!”

And while he was helping himself she said:

“Don’t be afraid! Don t be afraid of it! “

Everything went on smoothly. Mrs. Kearney bought some lovely blush-pink charmeuse in Brown Thomas’s to let into the front of Kathleen’s dress. It cost a pretty penny; but there are occasions when a little expense is justifiable. She took a dozen of two-shilling tickets for the final concert and sent them to those friends who could not be trusted to come otherwise. She forgot nothing, and, thanks to her, everything that was to be done was done.

The concerts were to be on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. When Mrs. Kearney arrived with her daughter at the Antient Concert Rooms on Wednesday night she did not like the look of things. A few young men, wearing bright blue badges in their coats, stood idle in the vestibule; none of them wore evening dress. She passed by with her daughter and a quick glance through the open door of the hall showed her the cause of the stewards’ idleness. At first she wondered had she mistaken the hour. No, it was twenty minutes to eight.

In the dressing-room behind the stage she was introduced to the secretary of the Society, Mr. Fitzpatrick. She smiled and shook his hand. He was a little man, with a white, vacant face. She noticed that he wore his soft brown hat carelessly on the side of his head and that his accent was flat. He held a programme in his hand, and, while he was talking to her, he chewed one end of it into a moist pulp. He seemed to bear disappointments lightly. Mr. Holohan came into the dressingroom every few minutes with reports from the box-office. The artistes talked among themselves nervously, glanced from time to time at the mirror and rolled and unrolled their music. When it was nearly half-past eight, the few people in the hall began to express their desire to be entertained. Mr. Fitzpatrick came in, smiled vacantly at the room, and said:

“Well now, ladies and gentlemen. I suppose we’d better open the ball.”

Mrs. Kearney rewarded his very flat final syllable with a quick stare of contempt, and then said to her daughter encouragingly:

“Are you ready, dear?”

When she had an opportunity, she called Mr. Holohan aside and asked him to tell her what it meant. Mr. Holohan did not know what it meant. He said that the committee had made a mistake in arranging for four concerts: four was too many.

“And the artistes!” said Mrs. Kearney. “Of course they are doing their best, but really they are not good.”

Mr. Holohan admitted that the artistes were no good but the committee, he said, had decided to let the first three concerts go as they pleased and reserve all the talent for Saturday night. Mrs. Kearney said nothing, but, as the mediocre items followed one another on the platform and the few people in the hall grew fewer and fewer, she began to regret that she had put herself to any expense for such a concert. There was something she didn’t like in the look of things and Mr. Fitzpatrick’s vacant smile irritated her very much. However, she said nothing and waited to see how it would end. The concert expired shortly before ten, and everyone went home quickly.

The concert on Thursday night was better attended, but Mrs. Kearney saw at once that the house was filled with paper. The audience behaved indecorously, as if the concert were an informal dress rehearsal. Mr. Fitzpatrick seemed to enjoy himself; he was quite unconscious that Mrs. Kearney was taking angry note of his conduct. He stood at the edge of the screen, from time to time jutting out his head and exchanging a laugh with two friends in the corner of the balcony. In the course of the evening, Mrs. Kearney learned that the Friday concert was to be abandoned and that the committee was going to move heaven and earth to secure a bumper house on Saturday night. When she heard this, she sought out Mr. Holohan. She buttonholed him as he was limping out quickly with a glass of lemonade for a young lady and asked him was it true. Yes. it was true.

“But, of course, that doesn’t alter the contract,” she said. “The contract was for four concerts.”

Mr. Holohan seemed to be in a hurry; he advised her to speak to Mr. Fitzpatrick. Mrs. Kearney was now beginning to be alarmed. She called Mr. Fitzpatrick away from his screen and told him that her daughter had signed for four concerts and that, of course, according to the terms of the contract, she should receive the sum originally stipulated for, whether the society gave the four concerts or not. Mr. Fitzpatrick, who did not catch the point at issue very quickly, seemed unable to resolve the difficulty and said that he would bring the matter before the committee. Mrs. Kearney’s anger began to flutter in her cheek and she had all she could do to keep from asking:

“And who is the Cometty pray?”

But she knew that it would not be ladylike to do that: so she was silent.

Little boys were sent out into the principal streets of Dublin early on Friday morning with bundles of handbills. Special puffs appeared in all the evening papers, reminding the music loving public of the treat which was in store for it on the following evening. Mrs. Kearney was somewhat reassured, but be thought well to tell her husband part of her suspicions. He listened carefully and said that perhaps it would be better if he went with her on Saturday night. She agreed. She respected her husband in the same way as she respected the General Post Office, as something large, secure and fixed; and though she knew the small number of his talents she appreciated his abstract value as a male. She was glad that he had suggested coming with her. She thought her plans over.

The night of the grand concert came. Mrs. Kearney, with her husband and daughter, arrived at the Ancient Concert Rooms three-quarters of an hour before the time at which the concert was to begin. By ill luck it was a rainy evening. Mrs. Kearney placed her daughter’s clothes and music in charge of her husband and went all over the building looking for Mr. Holohan or Mr. Fitzpatrick. She could find neither. She asked the stewards was any member of the committee in the hall and, after a great deal of trouble, a steward brought out a little woman named Miss Beirne to whom Mrs. Kearney explained that she wanted to see one of the secretaries. Miss Beirne expected them any minute and asked could she do anything. Mrs. Kearney looked searchingly at the oldish face which was screwed into an expression of trustfulness and enthusiasm and answered:

“No, thank you!”

The little woman hoped they would have a good house. She looked out at the rain until the melancholy of the wet street effaced all the trustfulness and enthusiasm from her twisted features. Then she gave a little sigh and said:

“Ah, well! We did our best, the dear knows.”

Mrs. Kearney had to go back to the dressing-room.

The artistes were arriving. The bass and the second tenor had already come. The bass, Mr. Duggan, was a slender young man with a scattered black moustache. He was the son of a hall porter in an office in the city and, as a boy, he had sung prolonged bass notes in the resounding hall. From this humble state he had raised himself until he had become a first-rate artiste. He had appeared in grand opera. One night, when an operatic artiste had fallen ill, he had undertaken the part of the king in the opera of Maritana at the Queen’s Theatre. He sang his music with great feeling and volume and was warmly welcomed by the gallery; but, unfortunately, he marred the good impression by wiping his nose in his gloved hand once or twice out of thoughtlessness. He was unassuming and spoke little. He said yous so softly that it passed unnoticed and he never drank anything stronger than milk for his voice’s sake. Mr. Bell, the second tenor, was a fair-haired little man who competed every year for prizes at the Feis Ceoil. On his fourth trial he had been awarded a bronze medal. He was extremely nervous and extremely jealous of other tenors and he covered his nervous jealousy with an ebullient friendliness. It was his humour to have people know what an ordeal a concert was to him. Therefore when he saw Mr. Duggan he went over to him and asked:

“Are you in it too? “

“Yes,” said Mr. Duggan.

Mr. Bell laughed at his fellow-sufferer, held out his hand and said:

“Shake!”

Mrs. Kearney passed by these two young men and went to the edge of the screen to view the house. The seats were being filled up rapidly and a pleasant noise circulated in the auditorium. She came back and spoke to her husband privately. Their conversation was evidently about Kathleen for they both glanced at her often as she stood chatting to one of her Nationalist friends, Miss Healy, the contralto. An unknown solitary woman with a pale face walked through the room. The women followed with keen eyes the faded blue dress which was stretched upon a meagre body. Someone said that she was Madam Glynn, the soprano.

“I wonder where did they dig her up,” said Kathleen to Miss Healy. “I’m sure I never heard of her.”

Miss Healy had to smile. Mr. Holohan limped into the dressing-room at that moment and the two young ladies asked him who was the unknown woman. Mr. Holohan said that she was Madam Glynn from London. Madam Glynn took her stand in a corner of the room, holding a roll of music stiffly before her and from time to time changing the direction of her startled gaze. The shadow took her faded dress into shelter but fell revengefully into the little cup behind her collar-bone. The noise of the hall became more audible. The first tenor and the baritone arrived together. They were both well dressed, stout and complacent and they brought a breath of opulence among the company.

Mrs. Kearney brought her daughter over to them, and talked to them amiably. She wanted to be on good terms with them but, while she strove to be polite, her eyes followed Mr. Holohan in his limping and devious courses. As soon as she could she excused herself and went out after him.

“Mr. Holohan, I want to speak to you for a moment,” she said.

They went down to a discreet part of the corridor. Mrs Kearney asked him when was her daughter going to be paid. Mr. Holohan said that Mr. Fitzpatrick had charge of that. Mrs. Kearney said that she didn’t know anything about Mr. Fitzpatrick. Her daughter had signed a contract for eight guineas and she would have to be paid. Mr. Holohan said that it wasn’t his business.

“Why isn’t it your business?” asked Mrs. Kearney. “Didn’t you yourself bring her the contract? Anyway, if it’s not your business it’s my business and I mean to see to it.”

“You’d better speak to Mr. Fitzpatrick,” said Mr. Holohan distantly.

“I don’t know anything about Mr. Fitzpatrick,” repeated Mrs. Kearney. “I have my contract, and I intend to see that it is carried out.”

When she came back to the dressing-room her cheeks were slightly suffused. The room was lively. Two men in outdoor dress had taken possession of the fireplace and were chatting familiarly with Miss Healy and the baritone. They were the Freeman man and Mr. O’Madden Burke. The Freeman man had come in to say that he could not wait for the concert as he had to report the lecture which an American priest was giving in the Mansion House. He said they were to leave the report for him at the Freeman office and he would see that it went in. He was a grey-haired man, with a plausible voice and careful manners. He held an extinguished cigar in his hand and the aroma of cigar smoke floated near him. He had not intended to stay a moment because concerts and artistes bored him considerably but he remained leaning against the mantelpiece. Miss Healy stood in front of him, talking and laughing. He was old enough to suspect one reason for her politeness but young enough in spirit to turn the moment to account. The warmth, fragrance and colour of her body appealed to his senses. He was pleasantly conscious that the bosom which he saw rise and fall slowly beneath him rose and fell at that moment for him, that the laughter and fragrance and wilful glances were his tribute. When he could stay no longer he took leave of her regretfully.

“O’Madden Burke will write the notice,” he explained to Mr. Holohan, “and I’ll see it in.”

“Thank you very much, Mr. Hendrick,” said Mr. Holohan, “you’ll see it in, I know. Now, won’t you have a little something before you go?”

“I don’t mind,” said Mr. Hendrick.

The two men went along some tortuous passages and up a dark staircase and came to a secluded room where one of the stewards was uncorking bottles for a few gentlemen. One of these gentlemen was Mr. O’Madden Burke, who had found out the room by instinct. He was a suave, elderly man who balanced his imposing body, when at rest, upon a large silk umbrella. His magniloquent western name was the moral umbrella upon which he balanced the fine problem of his finances. He was widely respected.

While Mr. Holohan was entertaining the Freeman man Mrs. Kearney was speaking so animatedly to her husband that he had to ask her to lower her voice. The conversation of the others in the dressing-room had become strained. Mr. Bell, the first item, stood ready with his music but the accompanist made no sign. Evidently something was wrong. Mr. Kearney looked straight before him, stroking his beard, while Mrs. Kearney spoke into Kathleen’s ear with subdued emphasis. From the hall came sounds of encouragement, clapping and stamping of feet. The first tenor and the baritone and Miss Healy stood together, waiting tranquilly, but Mr. Bell’s nerves were greatly agitated because he was afraid the audience would think that he had come late.

Mr. Holohan and Mr. O’Madden Burke came into the room In a moment Mr. Holohan perceived the hush. He went over to Mrs. Kearney and spoke with her earnestly. While they were speaking the noise in the hall grew louder. Mr. Holohan became very red and excited. He spoke volubly, but Mrs. Kearney said curtly at intervals:

“She won’t go on. She must get her eight guineas.”

Mr. Holohan pointed desperately towards the hall where the audience was clapping and stamping. He appealed to Mr Kearney and to Kathleen. But Mr. Kearney continued to stroke his beard and Kathleen looked down, moving the point of her new shoe: it was not her fault. Mrs. Kearney repeated:

“She won’t go on without her money.”

After a swift struggle of tongues Mr. Holohan hobbled out in haste. The room was silent. When the strain of the silence had become somewhat painful Miss Healy said to the baritone:

“Have you seen Mrs. Pat Campbell this week?”

The baritone had not seen her but he had been told that she was very fine. The conversation went no further. The first tenor bent his head and began to count the links of the gold chain which was extended across his waist, smiling and humming random notes to observe the effect on the frontal sinus. From time to time everyone glanced at Mrs. Kearney.

The noise in the auditorium had risen to a clamour when Mr. Fitzpatrick burst into the room, followed by Mr. Holohan who was panting. The clapping and stamping in the hall were punctuated by whistling. Mr. Fitzpatrick held a few banknotes in his hand. He counted out four into Mrs. Kearney’s hand and said she would get the other half at the interval. Mrs. Kearney said:

“This is four shillings short.”

But Kathleen gathered in her skirt and said: “Now. Mr. Bell,” to the first item, who was shaking like an aspen. The singer and the accompanist went out together. The noise in hall died away. There was a pause of a few seconds: and then the piano was heard.

The first part of the concert was very successful except for Madam Glynn’s item. The poor lady sang Killarney in a bodiless gasping voice, with all the old-fashioned mannerisms of intonation and pronunciation which she believed lent elegance to her singing. She looked as if she had been resurrected from an old stage-wardrobe and the cheaper parts of the hall made fun of her high wailing notes. The first tenor and the contralto, however, brought down the house. Kathleen played a selection of Irish airs which was generously applauded. The first part closed with a stirring patriotic recitation delivered by a young lady who arranged amateur theatricals. It was deservedly applauded; and, when it was ended, the men went out for the interval, content.

All this time the dressing-room was a hive of excitement. In one corner were Mr. Holohan, Mr. Fitzpatrick, Miss Beirne, two of the stewards, the baritone, the bass, and Mr. O’Madden Burke. Mr. O’Madden Burke said it was the most scandalous exhibition he had ever witnessed. Miss Kathleen Kearney’s musical career was ended in Dublin after that, he said. The baritone was asked what did he think of Mrs. Kearney’s conduct. He did not like to say anything. He had been paid his money and wished to be at peace with men. However, he said that Mrs. Kearney might have taken the artistes into consideration. The stewards and the secretaries debated hotly as to what should be done when the interval came.

“I agree with Miss Beirne,” said Mr. O’Madden Burke. “Pay her nothing.”

In another corner of the room were Mrs. Kearney and he: husband, Mr. Bell, Miss Healy and the young lady who had to recite the patriotic piece. Mrs. Kearney said that the Committee had treated her scandalously. She had spared neither trouble nor expense and this was how she was repaid.

They thought they had only a girl to deal with and that therefore, they could ride roughshod over her. But she would show them their mistake. They wouldn’t have dared to have treated her like that if she had been a man. But she would see that her daughter got her rights: she wouldn’t be fooled. If they didn’t pay her to the last farthing she would make Dublin ring. Of course she was sorry for the sake of the artistes. But what else could she do? She appealed to the second tenor who said he thought she had not been well treated. Then she appealed to Miss Healy. Miss Healy wanted to join the other group but she did not like to do so because she was a great friend of Kathleen’s and the Kearneys had often invited her to their house.

As soon as the first part was ended Mr. Fitzpatrick and Mr. Holohan went over to Mrs. Kearney and told her that the other four guineas would be paid after the committee meeting on the following Tuesday and that, in case her daughter did not play for the second part, the committee would consider the contract broken and would pay nothing.

“I haven’t seen any committee,” said Mrs. Kearney angrily. “My daughter has her contract. She will get four pounds eight into her hand or a foot she won’t put on that platform.”

“I’m surprised at you, Mrs. Kearney,” said Mr. Holohan. “I never thought you would treat us this way.”

“And what way did you treat me?” asked Mrs. Kearney.

Her face was inundated with an angry colour and she looked as if she would attack someone with her hands.

“I’m asking for my rights.” she said.

You might have some sense of decency,” said Mr. Holohan.

“Might I, indeed? . . . And when I ask when my daughter is going to be paid I can’t get a civil answer.”

She tossed her head and assumed a haughty voice:

“You must speak to the secretary. It’s not my business. I’m a great fellow fol-the-diddle-I-do.”

“I thought you were a lady,” said Mr. Holohan, walking away from her abruptly.

After that Mrs. Kearney’s conduct was condemned on all hands: everyone approved of what the committee had done. She stood at the door, haggard with rage, arguing with her husband and daughter, gesticulating with them. She waited until it was time for the second part to begin in the hope that the secretaries would approach her. But Miss Healy had kindly consented to play one or two accompaniments. Mrs. Kearney had to stand aside to allow the baritone and his accompanist to pass up to the platform. She stood still for an instant like an angry stone image and, when the first notes of the song struck her ear, she caught up her daughter’s cloak and said to her husband:

“Get a cab!”

He went out at once. Mrs. Kearney wrapped the cloak round her daughter and followed him. As she passed through the doorway she stopped and glared into Mr. Holohan’s face.

“I’m not done with you yet,” she said.

“But I’m done with you,” said Mr. Holohan.

Kathleen followed her mother meekly. Mr. Holohan began to pace up and down the room, in order to cool himself for he his skin on fire.

“That’s a nice lady!” he said. “O, she’s a nice lady!”

“You did the proper thing, Holohan,” said Mr. O’Madden Burke, poised upon his umbrella in approval.

James Joyce: A Mother

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

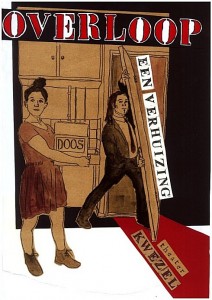

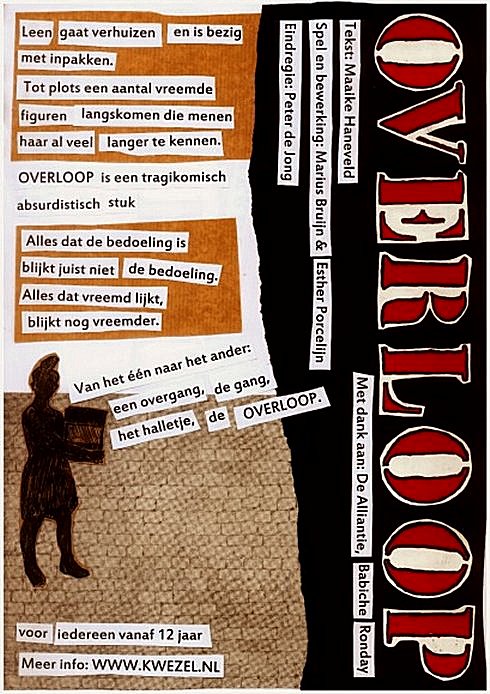

Theater Kwezel speelt:

OVERLOOP, een verhuizing

Een locatieproject in de Staalmanpleinbuurt, Amsterdam. Een theatervoorstelling over die belangrijke stap in je leven. Van Esther Porcelijn, Marius Bruijn en Maaike Haneveld. Overloop wordt een komische voorstelling met tekstscenes, poppenspel (voor volwassenen) en muziek voor iedereen vanaf 12 jaar.

Theater

OVERLOOP is gemaakt op locatie op het Abraham Staalmanplein in Amsterdam Slotervaart. In deze buurt, de Staalmanpleinbuurt, zijn grootschalige veranderingen gaande. Oude flats worden afgebroken, nieuwe worden gebouwd. Overal zijn mensen aan het verhuizen. Dit is het decor van de komische en absurdistische theatervoorstelling. Ons personage, Leen, woont te midden van deze straten. En ze is vastbesloten te vertrekken.

Thema

Overloop gaat over een overgangsfase, een stap in het onbekende. Het onbekende ziet er wellicht duister, bedreigend en verwarrend uit, er lijken weinig wegen te bewandelen en weinig perspectief op verbetering. En toch wil hoofdpersoon Leen die stap zetten. Om er in de nieuwe situatie beter en zelfverzekerder uit te komen. En misschien is die nieuwe situatie wel gewoon in het oude huis!

De Makers

Bewerking en spel: Marius Bruijn & Esther Porcelijn

Regie: Peter de Jong

Tekst: Maaike Haneveld

Bekijk de Teaser op YouTube

Voorstellingen

OP LOCATIE op het Abraham Staalmanplein 12, Amsterdam Slotervaart, Borrel na afloop

– try out – vrijdag 13 jan. 19:00

– première – vrijdag 13 jan. 21:00

– zaterdag 14 jan. 16:00 en 20:00

– zondag 15 jan. 14:00 en 17:00

– zaterdag 21 jan. 16:00 en 20:00

– zondag 22 jan. 14:00 en 17:00

Extra voorstellingen in de

Vondelbunker: Vondelpark 6, Amsterdam

www.vondelbunker.nl

– vrijdag 20 januari 2012, Toegang 10 euro,

reserveren aanbevolen via: marius@kwezel.nl

Meer info op www.kwezel.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther, THEATRE

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

An Encounter

It was Joe Dillon who introduced the Wild West to us. He had a little library made up of old numbers of The Union Jack , Pluck and The Halfpenny Marvel . Every evening after school we met in his back garden and arranged Indian battles. He and his fat young brother Leo, the idler, held the loft of the stable while we tried to carry it by storm; or we fought a pitched battle on the grass. But, however well we fought, we never won siege or battle and all our bouts ended with Joe Dillon’s war dance of victory. His parents went to eight-o’clock mass every morning in Gardiner Street and the peaceful odour of Mrs. Dillon was prevalent in the hall of the house. But he played too fiercely for us who were younger and more timid. He looked like some kind of an Indian when he capered round the garden, an old tea-cosy on his head, beating a tin with his fist and yelling:

“Ya! yaka, yaka, yaka!”

Everyone was incredulous when it was reported that he had a vocation for the priesthood. Nevertheless it was true.

A spirit of unruliness diffused itself among us and, under its influence, differences of culture and constitution were waived. We banded ourselves together, some boldly, some in jest and some almost in fear: and of the number of these latter, the reluctant Indians who were afraid to seem studious or lacking in robustness, I was one. The adventures related in the literature of the Wild West were remote from my nature but, at least, they opened doors of escape. I liked better some American detective stories which were traversed from time to time by unkempt fierce and beautiful girls. Though there was nothing wrong in these stories and though their intention was sometimes literary they were circulated secretly at school. One day when Father Butler was hearing the four pages of Roman History clumsy Leo Dillon was discovered with a copy of The Halfpenny Marvel.

“This page or this page? This page Now, Dillon, up! ‘Hardly had the day’ . . . Go on! What day? ‘Hardly had the day dawned’ . . . Have you studied it? What have you there in your pocket?”

Everyone’s heart palpitated as Leo Dillon handed up the paper and everyone assumed an innocent face. Father Butler turned over the pages, frowning.

“What is this rubbish?” he said. “The Apache Chief! Is this what you read instead of studying your Roman History? Let me not find any more of this wretched stuff in this college. The man who wrote it, I suppose, was some wretched fellow who writes these things for a drink. I’m surprised at boys like you, educated, reading such stuff. I could understand it if you were . . . National School boys. Now, Dillon, I advise you strongly, get at your work or . . . ”

This rebuke during the sober hours of school paled much of the glory of the Wild West for me and the confused puffy face of Leo Dillon awakened one of my consciences. But when the restraining influence of the school was at a distance I began to hunger again for wild sensations, for the escape which those chronicles of disorder alone seemed to offer me. The mimic warfare of the evening became at last as wearisome to me as the routine of school in the morning because I wanted real adventures to happen to myself. But real adventures, I reflected, do not happen to people who remain at home: they must be sought abroad.

The summer holidays were near at hand when I made up my mind to break out of the weariness of schoollife for one day at least. With Leo Dillon and a boy named Mahony I planned a day’s miching. Each of us saved up sixpence. We were to meet at ten in the morning on the Canal Bridge. Mahony’s big sister was to write an excuse for him and Leo Dillon was to tell his brother to say he was sick. We arranged to go along the Wharf Road until we came to the ships, then to cross in the ferryboat and walk out to see the Pigeon House. Leo Dillon was afraid we might meet Father Butler or someone out of the college; but Mahony asked, very sensibly, what would Father Butler be doing out at the Pigeon House. We were reassured: and I brought the first stage of the plot to an end by collecting sixpence from the other two, at the same time showing them my own sixpence. When we were making the last arrangements on the eve we were all vaguely excited. We shook hands, laughing, and Mahony said:

“Till tomorrow, mates!”

That night I slept badly. In the morning I was firstcomer to the bridge as I lived nearest. I hid my books in the long grass near the ashpit at the end of the garden where nobody ever came and hurried along the canal bank. It was a mild sunny morning in the first week of June. I sat up on the coping of the bridge admiring my frail canvas shoes which I had diligently pipeclayed overnight and watching the docile horses pulling a tramload of business people up the hill. All the branches of the tall trees which lined the mall were gay with little light green leaves and the sunlight slanted through them on to the water. The granite stone of the bridge was beginning to be warm and I began to pat it with my hands in time to an air in my head. I was very happy.

When I had been sitting there for five or ten minutes I saw Mahony’s grey suit approaching. He came up the hill, smiling, and clambered up beside me on the bridge. While we were waiting he brought out the catapult which bulged from his inner pocket and explained some improvements which he had made in it. I asked him why he had brought it and he told me he had brought it to have some gas with the birds. Mahony used slang freely, and spoke of Father Butler as Old Bunser. We waited on for a quarter of an hour more but still there was no sign of Leo Dillon. Mahony, at last, jumped down and said:

“Come along. I knew Fatty’d funk it.”

“And his sixpence . . . ?” I said.

“That’s forfeit,” said Mahony. “And so much the better for us, a bob and a tanner instead of a bob.”

We walked along the North Strand Road till we came to the Vitriol Works and then turned to the right along the Wharf Road. Mahony began to play the Indian as soon as we were out of public sight. He chased a crowd of ragged girls, brandishing his unloaded catapult and, when two ragged boys began, out of chivalry, to fling stones at us, he proposed that we should charge them. I objected that the boys were too small and so we walked on, the ragged troop screaming after us: “Swaddlers! Swaddlers!” thinking that we were Protestants because Mahony, who was dark-complexioned, wore the silver badge of a cricket club in his cap. When we came to the Smoothing Iron we arranged a siege; but it was a failure because you must have at least three. We revenged ourselves on Leo Dillon by saying what a funk he was and guessing how many he would get at three o’clock from Mr. Ryan.

We came then near the river. We spent a long time walking about the noisy streets flanked by high stone walls, watching the working of cranes and engines and often being shouted at for our immobility by the drivers of groaning carts. It was noon when we reached the quays and as all the labourers seemed to be eating their lunches, we bought two big currant buns and sat down to eat them on some metal piping beside the river. We pleased ourselves with the spectacle of Dublin’s commerce, the barges signalled from far away by their curls of woolly smoke, the brown fishing fleet beyond Ringsend, the big white sailing-vessel which was being discharged on the opposite quay. Mahony said it would be right skit to run away to sea on one of those big ships and even I, looking at the high masts, saw, or imagined, the geography which had been scantily dosed to me at school gradually taking substance under my eyes. School and home seemed to recede from us and their influences upon us seemed to wane.

We crossed the Liffey in the ferryboat, paying our toll to be transported in the company of two labourers and a little Jew with a bag. We were serious to the point of solemnity, but once during the short voyage our eyes met and we laughed. When we landed we watched the discharging of the graceful three-master which we had observed from the other quay. Some bystander said that she was a Norwegian vessel. I went to the stern and tried to decipher the legend upon it but, failing to do so, I came back and examined the foreign sailors to see had any of them green eyes for I had some confused notion. . . . The sailors’ eyes were blue and grey and even black. The only sailor whose eyes could have been called green was a tall man who amused the crowd on the quay by calling out cheerfully every time the planks fell:

“All right! All right!”

When we were tired of this sight we wandered slowly into Ringsend. The day had grown sultry, and in the windows of the grocers’ shops musty biscuits lay bleaching. We bought some biscuits and chocolate which we ate sedulously as we wandered through the squalid streets where the families of the fishermen live. We could find no dairy and so we went into a huckster’s shop and bought a bottle of raspberry lemonade each. Refreshed by this, Mahony chased a cat down a lane, but the cat escaped into a wide field. We both felt rather tired and when we reached the field we made at once for a sloping bank over the ridge of which we could see the Dodder.

It was too late and we were too tired to carry out our project of visiting the Pigeon House. We had to be home before four o’clock lest our adventure should be discovered. Mahony looked regretfully at his catapult and I had to suggest going home by train before he regained any cheerfulness. The sun went in behind some clouds and left us to our jaded thoughts and the crumbs of our provisions.

There was nobody but ourselves in the field. When we had lain on the bank for some time without speaking I saw a man approaching from the far end of the field. I watched him lazily as I chewed one of those green stems on which girls tell fortunes. He came along by the bank slowly. He walked with one hand upon his hip and in the other hand he held a stick with which he tapped the turf lightly. He was shabbily dressed in a suit of greenish-black and wore what we used to call a jerry hat with a high crown. He seemed to be fairly old for his moustache was ashen-grey. When he passed at our feet he glanced up at us quickly and then continued his way. We followed him with our eyes and saw that when he had gone on for perhaps fifty paces he turned about and began to retrace his steps. He walked towards us very slowly, always tapping the ground with his stick, so slowly that I thought he was looking for something in the grass.

He stopped when he came level with us and bade us goodday. We answered him and he sat down beside us on the slope slowly and with great care. He began to talk of the weather, saying that it would be a very hot summer and adding that the seasons had changed gready since he was a boy, a long time ago. He said that the happiest time of one’s life was undoubtedly one’s schoolboy days and that he would give anything to be young again. While he expressed these sentiments which bored us a little we kept silent. Then he began to talk of school and of books. He asked us whether we had read the poetry of Thomas Moore or the works of Sir Walter Scott and Lord Lytton. I pretended that I had read every book he mentioned so that in the end he said:

“Ah, I can see you are a bookworm like myself. Now,” he added, pointing to Mahony who was regarding us with open eyes, “he is different; he goes in for games.”

He said he had all Sir Walter Scott’s works and all Lord Lytton’s works at home and never tired of reading them. “Of course,” he said, “there were some of Lord Lytton’s works which boys couldn’t read.” Mahony asked why couldn’t boys read them, a question which agitated and pained me because I was afraid the man would think I was as stupid as Mahony. The man, however, only smiled. I saw that he had great gaps in his mouth between his yellow teeth. Then he asked us which of us had the most sweethearts. Mahony mentioned lightly that he had three totties. The man asked me how many I had. I answered that I had none. He did not believe me and said he was sure I must have one. I was silent.

“Tell us,” said Mahony pertly to the man, “how many have you yourself?”

The man smiled as before and said that when he was our age he had lots of sweethearts.

“Every boy,” he said, “has a little sweetheart.”

His attitude on this point struck me as strangely liberal in a man of his age. In my heart I thought that what he said about boys and sweethearts was reasonable. But I disliked the words in his mouth and I wondered why he shivered once or twice as if he feared something or felt a sudden chill. As he proceeded I noticed that his accent was good. He began to speak to us about girls, saying what nice soft hair they had and how soft their hands were and how all girls were not so good as they seemed to be if one only knew. There was nothing he liked, he said, so much as looking at a nice young girl, at her nice white hands and her beautiful soft hair. He gave me the impression that he was repeating something which he had learned by heart or that, magnetised by some words of his own speech, his mind was slowly circling round and round in the same orbit. At times he spoke as if he were simply alluding to some fact that everybody knew, and at times he lowered his voice and spoke mysteriously as if he were telling us something secret which he did not wish others to overhear. He repeated his phrases over and over again, varying them and surrounding them with his monotonous voice. I continued to gaze towards the foot of the slope, listening to him.

After a long while his monologue paused. He stood up slowly, saying that he had to leave us for a minute or so, a few minutes, and, without changing the direction of my gaze, I saw him walking slowly away from us towards the near end of the field. We remained silent when he had gone. After a silence of a few minutes I heard Mahony exclaim:

“I say! Look what he’s doing!”

As I neither answered nor raised my eyes Mahony exclaimed again:

“I say . . . He’s a queer old josser!”

“In case he asks us for our names,” I said “let you be Murphy and I’ll be Smith.”

We said nothing further to each other. I was still considering whether I would go away or not when the man came back and sat down beside us again. Hardly had he sat down when Mahony, catching sight of the cat which had escaped him, sprang up and pursued her across the field. The man and I watched the chase. The cat escaped once more and Mahony began to throw stones at the wall she had escaladed. Desisting from this, he began to wander about the far end of the field, aimlessly.

After an interval the man spoke to me. He said that my friend was a very rough boy and asked did he get whipped often at school. I was going to reply indignantly that we were not National School boys to be whipped, as he called it; but I remained silent. He began to speak on the subject of chastising boys. His mind, as if magnetised again by his speech, seemed to circle slowly round and round its new centre. He said that when boys were that kind they ought to be whipped and well whipped. When a boy was rough and unruly there was nothing would do him any good but a good sound whipping. A slap on the hand or a box on the ear was no good: what he wanted was to get a nice warm whipping. I was surprised at this sentiment and involuntarily glanced up at his face. As I did so I met the gaze of a pair of bottle-green eyes peering at me from under a twitching forehead. I turned my eyes away again.

The man continued his monologue. He seemed to have forgotten his recent liberalism. He said that if ever he found a boy talking to girls or having a girl for a sweetheart he would whip him and whip him; and that would teach him not to be talking to girls. And if a boy had a girl for a sweetheart and told lies about it then he would give him such a whipping as no boy ever got in this world. He said that there was nothing in this world he would like so well as that. He described to me how he would whip such a boy as if he were unfolding some elaborate mystery. He would love that, he said, better than anything in this world; and his voice, as he led me monotonously through the mystery, grew almost affectionate and seemed to plead with me that I should understand him.

I waited till his monologue paused again. Then I stood up abruptly. Lest I should betray my agitation I delayed a few moments pretending to fix my shoe properly and then, saying that I was obliged to go, I bade him good-day. I went up the slope calmly but my heart was beating quickly with fear that he would seize me by the ankles. When I reached the top of the slope I turned round and, without looking at him, called loudly across the field:

“Murphy!”

My voice had an accent of forced bravery in it and I was ashamed of my paltry stratagem. I had to call the name again before Mahony saw me and hallooed in answer. How my heart beat as he came running across the field to me! He ran as if to bring me aid. And I was penitent; for in my heart I had always despised him a little.

James Joyce: An Encounter

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

photo KEMP=MAG

Esther Porcelijn

Bomensoep

Een modern sprookje

Er was eens een jongen die de wereld wilde redden.

De jongen hield niet van dingen die verkeerd gaan, en zeker niet van dingen die vergaan.

De jongen werd altijd treurig in de herfst, als de bladeren van de bomen vallen.

Niemand anders leek het erg te vinden, niemand keek er van op of om. “Ja de bladeren vallen van de bomen, nou en?” zeiden ze dan tegen hem.

Hij vond de bomen dan zo naakt en vond het zielig voor ze dat niemand ze een jasje om deed.

De mensen lachten hem dan uit als hij dat zei. “Het wordt toch lente!” zeiden ze dan.

“ja, maar wat nu als de lente niet komt! Wat als de bomen eeuwig zo kaal blijven?”

“dat is onzin, doe niet zo raar!” zeiden de mensen dan.

In de herfst bleef de jongen uren en uren naar een boom kijken, hoe elk blaadje viel en hoe de boom bij elk verloren blaadje even leek te schudden in de wind.

Als hij het te koud kreeg, ging hij naar huis, naar zijn moeder. Hij moest altijd op tijd thuis zijn om soep te maken. Zijn moeder lag vaak op bed, waarom precies wist hij niet, “ik heb weer last van mijn ziekte” zei ze dan. En als zijn moeder last had van haar ziekte moest hij soep maken. Het gebeurde steeds vaker.

Thuis begroette hij zijn moeder, tilde haar op, maakte het bed op, legde haar er weer in, stofte de kamer, gaf de planten water en maakte soep.

Hij ging bij haar op bed zitten met twee kommen soep. Hij vertelde haar over de bomen en hoe ze bladeren verloren en hoe ze het koud hadden. “De mensen vinden mij raar” zei hij. Zijn moeder zei dat hij een lieve maar inderdaad ook een rare jongen was. “Bomen hebben het niet koud”, zei ze, “En het wordt vanzelf weer lente, dat komt allemaal goed.”

“Ja, dat zeiden de mensen ook al,” zei de jongen, “Nou, zie je wel!” zei zijn moeder en ze draaide zich op haar zij en ging weer liggen “je moet nog huiswerk maken!”.

Hij besloot er maar niet meer over te beginnen. Het was al avond en hij was moe, te moe om nog huiswerk te maken.

Een paar maanden later werd het lente. Zo ging het elk jaar. Het stelde de jongen niet gerust. “Wat nu als de lente niet komt?”, dacht hij, “Moet ik elk jaar er opnieuw vanuit gaan dat de lente weer komt?” “De bomen moeten zo hard werken om weer nieuwe blaadjes te maken, zo houden ze toch te weinig tijd over?” “En waar hebben bomen tijd voor nodig dan?”, vroegen de mensen, “Om aan bomendingen te denken en bomendingen te doen.” , zei de jongen.

Een paar jaar verstreken en de jongen stond elk jaar naar de bomen te staren.

En elke lente keek hij argwanend naar de mensen om hem heen.

Tegen zijn moeder zei hij er maar niets meer over. Die was al ziek genoeg.

Op een dag, ergens in de herfst, besloot de jongen dat het genoeg was geweest met het vergaan van de bladeren.

Hij besloot om elk gevallen blaadje weer aan de boom te plakken. Hij ging elke dag met een trap en touw en lijm van huis, zette de trap tegen een boom, raapte een blaadje op van de grond en bond deze met een touwtje aan de tak en lijmde deze vast.

“Hij is gek geworden!” , zeiden de mensen op de grond, en vonden het zó raar dat ze hun schouders ophaalden en doorliepen.

Als het lukte dan ving de jongen de blaadjes op, zodat ze niet op de grond vielen. Dat was het beste, dan kon hij precies het blaadje bij de juiste tak vinden.

Elke dag ging hij na dat werk terug naar zijn moeder om soep te maken. Zij was erg ziek geworden en had veel hulp nodig. Hij tilde haar weer op, maakte het bed op, legde haar er weer in, stofte de kamer, gaf de planten water en maakte soep. “Hoe is ‘t buiten?”, vroeg zij dan. “Buiten is het goed,” zei hij dan. Veel meer kon ze niet zeggen, daarvoor was ze te moe, en over huiswerk werd al heel lang niet meer gesproken.

Iedere dag ging hij van huis met de trap, ‘t touw en de lijm om de bomen te repareren, totdat hij alle blaadjes weer aan alle bomen had gedaan. Tevreden keek hij rond en dacht: “zo, jullie vergaan tenminste niet.”

Een paar maanden later was het lente, of tenminste, dat had het moeten zijn. Er kwamen geen nieuwe blaadjes aan de bomen. De mensen op straat keken omhoog en vonden het zo raar dat ze hun schouders ophaalden en doorliepen.

De jongen was niet verbaasd maar maakte zich wel zorgen om de blaadjes die nu bruin waren. Er was niets groens te vinden.

Hij was thuis soep aan het maken voor zijn moeder toen zij vroeg: “hoe is ‘t buiten?”

Hij wist niet wat hij moest zeggen en besloot haar mee naar buiten te nemen.

Eenmaal buiten wist de moeder niet wat ze zag. Overal bruine blaadjes, nergens iets groens, en mensen op straat die zich er niets van aantrokken. “het is toch ondertussen lente?”, vroeg ze, “ja”, zei hij, “heb jij dit gedaan?”, vroeg ze, “ja”, zei hij.

De moeder begon heel erg te huilen en ze sprak voorbijgangers aan.” Zien jullie niet wat jullie hebben gedaan door niets te doen? Deze jongen wilde de bomen redden, en nu is de lente verdwenen en jullie doen alsof er niets aan de hand is, kan het jullie dan niets schelen?”

De mensen op straat schrokken enorm. Ze wilden liever inderdaad ook groene blaadjes. En het kon ze toch wel wat schelen. “H.H.H…Heb je misschien wat hulp nodig?” vroeg iemand. “Ja” zei de jongen. En samen met iedereen gingen ze de bomen weer snoeien en klaarmaken voor het volgende jaar. Alle oude blaadjes eraf en ruimte maken voor de nieuwe. Alle oude takken en blaadjes in een grote emmer. Iedereen hielp mee.

De jongen keek naar de grote emmer vol blaadjes en takken. “Bomensoep” zei hij tegen zijn moeder. “Ja, bomensoep” zei zij. En de mensen op straat boden de jongen aan om hem ook thuis te helpen. De mensen vonden hem niet meer raar. Niemand haalde nog zijn schouders op en niemand liep nog door.

Bomensoep.

Esther Porcelijn verhalen en gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

foto joep eijkens

Esther Porcelijn

Gedicht voor het overgebleven ijsblokje

Zal ik je opeten of niet

In mijn mond nemen

En laten smelten

Op je kauwen tot brokjes

En de brokjes weer herkauwen

Tot je water bent

Doorslikken en voelen

Hoe je niet koud smaakt

Als dat had gekund

Je bent vergaan, drinken is valsspelen

Ik ben te laat

Esther Porcelijn gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

foto jef van kempen

Installatie

Esther Porcelijn

tot stadsdichter van Tilburg

Op zondagmiddag 30 oktober a.s. zal afscheid worden genomen van Cees van Raak als de Tilburgse stadsdichter 2009-2011, en zal de nieuwe stadsdichter, Esther Porcelijn, worden geïnstalleerd.

De installatie wordt, zoals gebruikelijk, georganiseerd door Stichting Cools en vindt plaats in de Rode Salon van theater De NWE Vorst, Willem II straat 49. Van 12.45 uur tot ongeveer 13.05 uur is de inloop voor het installatieprogramma dat naar verwachting om 14.30 uur zal eindigen.

Het programma van de installatie zal worden gepresenteerd door oud-stadsdichter Nick J. Swarth. In hoofdlijnen omvat het programma de volgden onderdelen: Wilbert van Herwijnen, de voorzitter van de Stadsdichtercommissie, zal de keuze van de commissie voor Esther Porcelijn toelichten, en wethouder Marjo Frenk zal haar vervolgens installeren. Voorts zijn er optredens van Cees van Raak, Esther Porcelijn, en, op speciaal verzoek van laatstgenoemde, Neeltje Maria Min.

≡ Gedichten en prozateksten van Esther Porcelijn op deze website

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: City Poets / Stadsdichters, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

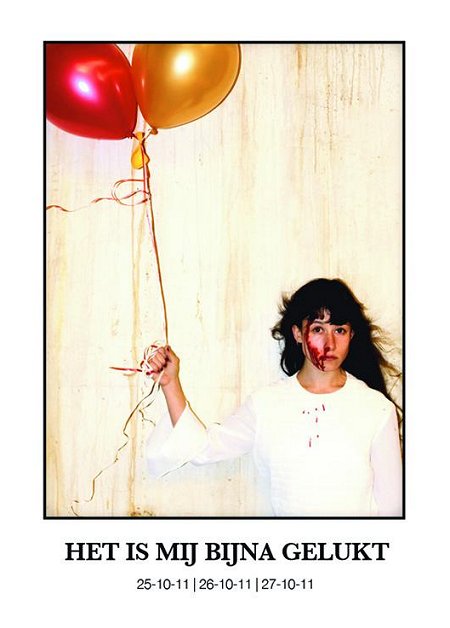

Wegens succes gaat de voorstelling

Het is mij bijna gelukt

in reprise!

Het is mij bijna gelukt is een voorstelling over de mythes en scepsis rondom het leven na de dood. Twee personages vechten met zichzelf en met elkaar om grip te krijgen op het hiernamaals.

De spelers en dramaturg hebben onderzoek gedaan naar bijna-dood-ervaringen en interviews gehouden met mensen die deze ervaringen hebben gehad. Zij willen wetenschap aan theater koppelen door grote onderwerpen compact te maken en thema’s, die door velen als zwaar worden gezien, licht te maken. Bij elke voorstelling zal een filosoof of wetenschapper een korte lezing geven over het desbetreffende onderwerp.

Bij de nieuwe voorstelling, vanaf begin januari met dezelfde groep, zal ook weer een wetenschapper gekoppeld worden om een lezing te geven. Theater Walhalla te Rotterdam wil de groep programmeren voor komend jaar in een drieluik.

Bij deze Esther Porcelijn en Jasper Hupkens voorstelling: Onder leiding van Fransje Christiaans hebben Het is mij bijna gelukt gemaakt. Filosoof Arthur Kok (Universiteit van Tilburg) zal de voorafgaande lezing verzorgen.

Locatie: Club-Trouw te Amsterdam op: 25,26 en 27 oktober.

Bekijk voor de kortingsactie naar dit filmpje: http://vimeo.com/30668988

Reserveren door te bellen: 020-463 77 88 of kijk op www.trouwamsterdam.nl onder het kopje “programma”, wees er snel bij, er zijn maar beperkte plaatsen!

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther, THEATRE

© foto joep eijkens

Verhuizing van een

vrouwelijke stadsdichter

Als het droste-effect hoogtij viert

En scheve ogen uit oude mannen puilen

Om net onder mijn rok te kijken

Wachtend op hun jeugdigheid

Heb ik toch geen medelijden.

Was ik maar één van hen,

Een rijpere oude man

onder mijn eigen rok kijkend.

Elke dag dat ik me verplaats is

Als een enorme verhuizing

Maar mochten mensen bang zijn

Dat ik te Amsterdams ben

Wees niet bevreesd,

Ik ben ook maar een mens.

We zitten allen in dezelfde carrousel.

Het ene paardje is roze en het andere paars

Maar allen in dezelfde carrousel van het droste-effect.

Merry Go-Merry Go

Merry Go Round

Misschien word ik ooit nog een echte vent.

Tot die tijd ben ik de kleinste vrouw,

of, als ik op een landkaart sta, de grootste ter wereld.

Het is wit en het staat in het Vondelpark..

Witte gij ut?

Esther Porcelijn

Esther Porcelijn is actrice, schrijfster, student filosofie en sinds augustus 2011 stadsdichter van Tilburg

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Jane Austen

(1775-1817)

Northanger Abbey

Chapter 10

The Allens, Thorpes, and Morlands all met in the evening at the theatre; and, as Catherine and Isabella sat together, there was then an opportunity for the latter to utter some few of the many thousand things which had been collecting within her for communication in the immeasurable length of time which had divided them. “Oh, heavens! My beloved Catherine, have I got you at last?” was her address on Catherine’s entering the box and sitting by her. “Now, Mr. Morland,” for he was close to her on the other side, “I shall not speak another word to you all the rest of the evening; so I charge you not to expect it. My sweetest Catherine, how have you been this long age? But I need not ask you, for you look delightfully. You really have done your hair in a more heavenly style than ever; you mischievous creature, do you want to attract everybody? I assure you, my brother is quite in love with you already; and as for Mr. Tilney — but that is a settled thing — even your modesty cannot doubt his attachment now; his coming back to Bath makes it too plain. Oh! What would not I give to see him! I really am quite wild with impatience. My mother says he is the most delightful young man in the world; she saw him this morning, you know; you must introduce him to me. Is he in the house now? Look about, for heaven’s sake! I assure you, I can hardly exist till I see him.”

“No,” said Catherine, “he is not here; I cannot see him anywhere.”

“Oh, horrid! Am I never to be acquainted with him? How do you like my gown? I think it does not look amiss; the sleeves were entirely my own thought. Do you know, I get so immoderately sick of Bath; your brother and I were agreeing this morning that, though it is vastly well to be here for a few weeks, we would not live here for millions. We soon found out that our tastes were exactly alike in preferring the country to every other place; really, our opinions were so exactly the same, it was quite ridiculous! There was not a single point in which we differed; I would not have had you by for the world; you are such a sly thing, I am sure you would have made some droll remark or other about it.”

“No, indeed I should not.”

“Oh, yes you would indeed; I know you better than you know yourself. You would have told us that we seemed born for each other, or some nonsense of that kind, which would have distressed me beyond conception; my cheeks would have been as red as your roses; I would not have had you by for the world.”

“Indeed you do me injustice; I would not have made so improper a remark upon any account; and besides, I am sure it would never have entered my head.”

Isabella smiled incredulously and talked the rest of the evening to James.

Catherine’s resolution of endeavouring to meet Miss Tilney again continued in full force the next morning; and till the usual moment of going to the pump–room, she felt some alarm from the dread of a second prevention. But nothing of that kind occurred, no visitors appeared to delay them, and they all three set off in good time for the pump–room, where the ordinary course of events and conversation took place; Mr. Allen, after drinking his glass of water, joined some gentlemen to talk over the politics of the day and compare the accounts of their newspapers; and the ladies walked about together, noticing every new face, and almost every new bonnet in the room. The female part of the Thorpe family, attended by James Morland, appeared among the crowd in less than a quarter of an hour, and Catherine immediately took her usual place by the side of her friend. James, who was now in constant attendance, maintained a similar position, and separating themselves from the rest of their party, they walked in that manner for some time, till Catherine began to doubt the happiness of a situation which, confining her entirely to her friend and brother, gave her very little share in the notice of either. They were always engaged in some sentimental discussion or lively dispute, but their sentiment was conveyed in such whispering voices, and their vivacity attended with so much laughter, that though Catherine’s supporting opinion was not unfrequently called for by one or the other, she was never able to give any, from not having heard a word of the subject. At length however she was empowered to disengage herself from her friend, by the avowed necessity of speaking to Miss Tilney, whom she most joyfully saw just entering the room with Mrs. Hughes, and whom she instantly joined, with a firmer determination to be acquainted, than she might have had courage to command, had she not been urged by the disappointment of the day before. Miss Tilney met her with great civility, returned her advances with equal goodwill, and they continued talking together as long as both parties remained in the room; and though in all probability not an observation was made, nor an expression used by either which had not been made and used some thousands of times before, under that roof, in every Bath season, yet the merit of their being spoken with simplicity and truth, and without personal conceit, might be something uncommon.

“How well your brother dances!” was an artless exclamation of Catherine’s towards the close of their conversation, which at once surprised and amused her companion.

“Henry!” she replied with a smile. “Yes, he does dance very well.”

“He must have thought it very odd to hear me say I was engaged the other evening, when he saw me sitting down. But I really had been engaged the whole day to Mr. Thorpe.” Miss Tilney could only bow. “You cannot think,” added Catherine after a moment’s silence, “how surprised I was to see him again. I felt so sure of his being quite gone away.”

“When Henry had the pleasure of seeing you before, he was in Bath but for a couple of days. He came only to engage lodgings for us.”

“That never occurred to me; and of course, not seeing him anywhere, I thought he must be gone. Was not the young lady he danced with on Monday a Miss Smith?”

“Yes, an acquaintance of Mrs. Hughes.”

“I dare say she was very glad to dance. Do you think her pretty?”

“Not very.”

“He never comes to the pump–room, I suppose?”

“Yes, sometimes; but he has rid out this morning with my father.”

Mrs. Hughes now joined them, and asked Miss Tilney if she was ready to go. “I hope I shall have the pleasure of seeing you again soon,” said Catherine. “Shall you be at the cotillion ball tomorrow?”

“Perhaps we — Yes, I think we certainly shall.”

“I am glad of it, for we shall all be there.” This civility was duly returned; and they parted — on Miss Tilney’s side with some knowledge of her new acquaintance’s feelings, and on Catherine’s, without the smallest consciousness of having explained them.

She went home very happy. The morning had answered all her hopes, and the evening of the following day was now the object of expectation, the future good. What gown and what head–dress she should wear on the occasion became her chief concern. She cannot be justified in it. Dress is at all times a frivolous distinction, and excessive solicitude about it often destroys its own aim. Catherine knew all this very well; her great aunt had read her a lecture on the subject only the Christmas before; and yet she lay awake ten minutes on Wednesday night debating between her spotted and her tamboured muslin, and nothing but the shortness of the time prevented her buying a new one for the evening. This would have been an error in judgment, great though not uncommon, from which one of the other sex rather than her own, a brother rather than a great aunt, might have warned her, for man only can be aware of the insensibility of man towards a new gown. It would be mortifying to the feelings of many ladies, could they be made to understand how little the heart of man is affected by what is costly or new in their attire; how little it is biased by the texture of their muslin, and how unsusceptible of peculiar tenderness towards the spotted, the sprigged, the mull, or the jackonet. Woman is fine for her own satisfaction alone. No man will admire her the more, no woman will like her the better for it. Neatness and fashion are enough for the former, and a something of shabbiness or impropriety will be most endearing to the latter. But not one of these grave reflections troubled the tranquillity of Catherine.

She entered the rooms on Thursday evening with feelings very different from what had attended her thither the Monday before. She had then been exulting in her engagement to Thorpe, and was now chiefly anxious to avoid his sight, lest he should engage her again; for though she could not, dared not expect that Mr. Tilney should ask her a third time to dance, her wishes, hopes, and plans all centred in nothing less. Every young lady may feel for my heroine in this critical moment, for every young lady has at some time or other known the same agitation. All have been, or at least all have believed themselves to be, in danger from the pursuit of someone whom they wished to avoid; and all have been anxious for the attentions of someone whom they wished to please. As soon as they were joined by the Thorpes, Catherine’s agony began; she fidgeted about if John Thorpe came towards her, hid herself as much as possible from his view, and when he spoke to her pretended not to hear him. The cotillions were over, the country–dancing beginning, and she saw nothing of the Tilneys.

“Do not be frightened, my dear Catherine,” whispered Isabella, “but I am really going to dance with your brother again. I declare positively it is quite shocking. I tell him he ought to be ashamed of himself, but you and John must keep us in countenance. Make haste, my dear creature, and come to us. John is just walked off, but he will be back in a moment.”

Catherine had neither time nor inclination to answer. The others walked away, John Thorpe was still in view, and she gave herself up for lost. That she might not appear, however, to observe or expect him, she kept her eyes intently fixed on her fan; and a self–condemnation for her folly, in supposing that among such a crowd they should even meet with the Tilneys in any reasonable time, had just passed through her mind, when she suddenly found herself addressed and again solicited to dance, by Mr. Tilney himself. With what sparkling eyes and ready motion she granted his request, and with how pleasing a flutter of heart she went with him to the set, may be easily imagined. To escape, and, as she believed, so narrowly escape John Thorpe, and to be asked, so immediately on his joining her, asked by Mr. Tilney, as if he had sought her on purpose! — it did not appear to her that life could supply any greater felicity.