Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

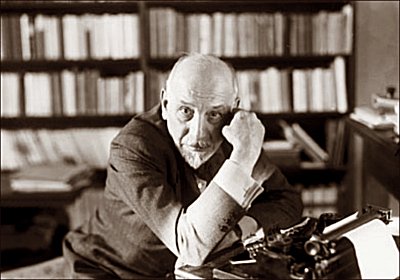

photo jef van kempen

Verlichting

Woeste dijen klagen steen en been

Over wie nu waar de vuile was heeft opgehangen,

Waarom de éne veel en de ander geen

Geruchten op kan vangen.

Wie heeft er ooit gehoord van gedachten

Die zweven in de lucht om vers te plukken,

Die voor alles wat je kunt bedenken zó

Je woorden uit je zinnen rukken.

De andere mensen zijn toch slechts decor

Die zijn er echt alleen om neer te halen,

Om aan te wijzen wat eraan mankeert

Te oud, te dik en ’t blijkt ook nog een kale.

Wie zegt er ooit iets wat vernieuwend is?

Dat werkelijk een klomp breekt of taboe,

Dat alles in de wereld op zijn kop zet

Of is dat maar elitair gedoe?

Je streelt je ego en bekijkt het in ’t raam

Het lijkt groter dan de dag ervoor,

Je borstelt het nog extra tot het glanst

Nog één keer kijken, ’t kan er wel mee door.

Het moment dat je het bijna weet

De allergrootste oplossing voor alles!

Je ziet het exact voor je, je hebt het beet!

En dat je ironie het komt vergallen.

Daar buiten is de wereld opgesplitst

In mensen die het zíjn en die het willen,

Het is jouw categorisering om jezelf

Uit het normaalste op te tillen.

Sta je van bovenaf te paraderen met je kennis

Dan zit je middenin de paradox van hen

Die, in vol daglicht, op de markt

Net gepasseerd zijn door Diogenes.

Esther Porcelijn

stadsdichter Tilburg, 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

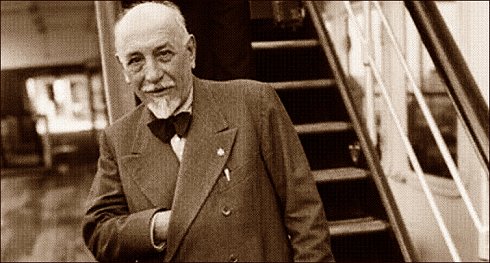

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (32)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

1

I understand, at last.

Upset? No, why should I be? So much water has passed under the bridges; the past is dead and distant. Life is here now, this life: a different life. Lawns, round about, and stages, the buildings miles away, almost in the country, between green grass and blue sky, of a cinematograph company. And she is here, an actress now…. He an actor too? Just fancy! Why, then, they must be colleagues? Splendid; I am so glad….

Everything perfect, everything smooth as oil. Life. That rustle of her blue silk skirt, now, with that curious white lace jacket, and that little winged hat like the helmet of the god of commerce, on her copper-coloured hair… yes. Life. A little heap of gravel turned up by the point of her sunshade; and an interval of silence, With her eyes wandering, fixed on the point of her sunshade that is turning up that little heap of gravel.

“What? Yes, of course, dear: a great bore.”

This is undoubtedly what must have happened yesterday, during my absence. The Nestoroff, with those wandering eyes of hers, strangely wide open, must have gone to the Kosmograph on purpose, in the hope of meeting him; she must have strolled up to him with an indifferent air, as one goes up to a friend, an acquaintance whom one happens to meet again after many years, and the butterfly, without the least suspicion of the spider, must have begun to flap his wings, quite exultant.

But how in the world did not Signorina Luisetta notice anything?

Well, that is a satisfaction which Signora Nestoroff must have had to forego. Yesterday, Signorina Luisetta, to celebrate her father’s return home, did not go with Signor Nuti to the Kosmograph. And so Signora Nestoroff cannot have had the pleasure of shewing this proud young lady who, the day before, had declined her invitation, how she, at any moment, whenever the fancy took her, could tear from the side of any proud young lady and recapture for herself all the mad young gentlemen who threatened tragedies, “st”, like that, by holding up a finger, and at once tame them, intoxicate them with the rustle of a silk skirt and a little heap of gravel turned up with the point of a sunshade. A bore, yes, a great bore unquestionably, because to this pleasure which she has had to forego Signora Nestoroff attached great importance.

That evening, knowing nothing of what had happened, Signorina Luisetta saw the young gentleman return home completely transformed, radiant with happiness. How was she to suppose that this transformation, this radiance could be due to a meeting with the Nestoroff, if, whenever she thinks with terror of that meeting, she sees red, black, confusion, madness, tragedy? And so this change, this radiance, was the effect of Papa’s return home on him also? Well, that it is of any great importance to him, her father’s return home, Signorina Luisetta cannot suppose, no; but that he should take pleasure in it, and seek to attune himself to other people’s rejoicing, why in the world not?

How else is his jubilation to be explained? And it is something to be thankful for; it is a thing to rejoice in, because this jubilation shews that his heart has become lighter, more open, so that he can readily assimilate the joy of other people.

These must certainly have been the thoughts of Signorina Luisetta. Yesterday; not to-day.

To-day she came to the Kosmograph with me, her face clouded. She had found, greatly to her surprise, that Signor Nuti had already left the house at an early hour, while it was still dark. She did not wish to display, as we went along, resentment and alarm, after the spectacle offered me last night of her gaiety; and so asked me where I had been yesterday and what I had done. “I? Oh, only a little pleasure jaunt….” And had I enjoyed myself? “Oh, immensely, to begin with at least. Afterwards….” The way things happen. We make all the arrangements for a pleasure party; we imagine that we have thought of everything, have taken every precaution so that the excursion may be a success, with no unfortunate incident to mar it; and yet there is always something, one of the many things, of which we have not thought; one thing escapes us… well, for instance, suppose there is a family with a number of children, who propose to go and spend a fine summer day picnicking in the country, there are the second child’s shoes, in one of which there is a nail, a mere nothing, a tiny nail, inside, sticking up in the heel, which needs hammering down. The mother remembered it, as soon as she got out of bed; but afterwards, you know what happens–with everything to get ready for the excursion, she forgot all about it. And that pair of shoes, with their little tongues sticking up like the pricked ears of a wily rabbit, standing in the row among all the other pairs, cleaned and polished and all ready for the children to put on, wait there and seem to be gloating in silence over the trick they are going to play on the mother who has forgotten all about them and who now, at the last moment, is in a greater bustle than ever, in wild confusion, because the father is down below at the foot of the stair shouting to her to make haste and all the children round her shout to her to make haste, they are so impatient. That pair of shoes, as the mother takes them to thrust them hurriedly on the child’s feet, say to her with a mocking laugh:

“Ah yes, mother dear; but us, you know? You have forgotten about us; and you’ll see that we shall spoil the whole day for you: when you are half way there that little nail will begin to hurt your child’s foot and make it cry and limp.”

Well, something of that sort happened to me too. No, not a nail to be hammered down in my boot. Another little detail had escaped my memory…. “What?” Nothing: another little detail. I did not wish to tell her. Another thing, Signorina Luisetta, which perhaps had long ago broken down in me.

To say that Signorina Luisetta paid me any close attention would not be true. And, as we went on our way, while I allowed my lips to go On speaking, I was thinking:

“Ah, you are not interested, my dear child, in what I am telling you? My misadventure leaves you indifferent, does it? Well, you shall see with what an air of indifference I, in my turn, to pay you back in your own coin, am going to receive the unpleasant surprise that is in store for you, as soon as you enter the Kosmograph me: you shall see!”

In fact, before we had advanced five yards across the tree-shaded lawn in front of the first building of the Kosmograph, there we saw, strolling side by side, like the dearest of friends, Signor Nuti and Signora Nestoroff: she, with her sunshade open, resting upon her shoulder, and twirling the handle.

What a look Signorina Luisetta gave me! And I: “You see! They are taking a quiet stroll. She is twirling her sunshade.”

So pale, however, so pale had the poor child turned, that I was afraid of her falling to the ground, in a faint: instinctively I put out my hand to support her arm; she withdrew her arm angrily, and looked me straight in the face. Evidently the suspicion flashed across her mind that it was my doing, a plot on my part (by arrangement, very possibly, with Polacco), that quiet and friendly reconciliation of Nuti and Signora Nestoroff, the first-fruits of the visit paid by me to that lady two days ago, and perhaps also of my mysterious absence yesterday. It must have seemed to her a vile mockery, all this secret machination, as it entered her mind in a flash. To make her dread the imminence, day after day, of a tragedy, should those two meet; to make her conceive such a terror of their meeting; to make her suffer such agony in order to pacify his ravings with a piteous deception, which had cost her so dear, and to what purpose! To offer her as a final reward the delicious picture of those two taking their quiet morning stroll under the trees on the lawn? Oh, villainy! Was it for this? For the amusement of laughing at a poor child who had taken it all seriously, plunged into the midst of this sordid, vulgar intrigue? She looked for nothing pleasant, in the absurd, miserable conditions of her life; but why this as well? Why mockery also? It was vile!

All this I read in the poor child’s eyes. Could I prove to her, there and then, that her suspicion was unjust, that life is like that–to-day more than ever it was before–made to offer such spectacles; and that I myself was in no way to blame?

I had hardened my heart; I was glad that she should pay for the injustice of her suspicion by her suffering at that spectacle, at the sight of those people, to whom I as well as she, unasked, had given something of ourselves, something that was now smarting, bruised and wounded, inside us. But we deserved it! And now, it pleased me to have her at this moment as my companion, while those two strolled up and down there without so much as seeing us. Indifference, indifference, Signorina Luisetta, there you are!

“If you will excuse me,” it occurred to me to say to her, “I shall go and get my camera, and take my place here, as is my duty, impassive.” And I felt a strange smile on my lips, which was almost the grin of a dog when he bares his teeth at some secret thought. I was looking meanwhile towards the door of the building beyond, from which emerged, coming towards us, Polacco, Bertini and Fantappiè. Suddenly there occurred a thing which I ought really to have expected, which justified Signorina Luisetta in trembling so violently and rebuked me for having chosen to remain indifferent. My mask of indifference I was obliged to throw aside in a moment, at the threat of a danger which did really seem to all of us imminent and terrible. I caught the first glimpse of it in the appearance of Polacco, who had come close up to us with Bertini and Fantappiè. They were talking among themselves, evidently of that couple who were still strolling beneath the trees, and all three were laughing at some witticism that had fallen from Fantappiè, when all of a sudden they stopped short in front of us with faces of chalk, staring eyes, all three of them. But most of all in the face of Polacco I read terror. I turned to look over my shoulder: Carlo Ferro!

He was coming up behind us, still with his travelling cap on his head, as he had left the train a few minutes earlier. And those two, meanwhile, continued to stroll up and down, together, without the least suspicion, under the trees. Did he see them! I cannot say. Fantappiè had the presence of mind to shout:

“Hallo, Carlo Ferro!”

The Nestoroff turned round, left her companion standing, and then one saw–free of charge–the moving spectacle of a lion-tamer who amid the terror of the spectators advances to meet an infuriated animal. Calmly she advanced, without haste, still balancing her open sunshade on her shoulder. And she had a smile on her lips, which said to us, without her deigning to look at us: “What are you afraid of, you idiots! I am here, a’nt I?” And a look in her eyes which I shall never forget, the look of one who knows that everyone must see that no fear can find a place in a person who looks straight ahead and advances so. The effect of that look on the savage face, the disordered person, the excited gait of Carlo Ferro was remarkable. We did not see his face, we saw his body grow limp and his pace slacken steadily as the fascination drew nearer to him. And the one sign that she too must be feeling somewhat agitated was this: she began to address him in French.

None of us cast a glance beyond her, where Aldo Nuti remained by himself, planted among the trees, but suddenly I became aware that one of us, she, Signorina Luisetta, was looking in that direction, was looking at him, and had perhaps looked at nothing else, as though for her the terror lay there and not in the two at whom the rest of us were gazing, in dismayed suspense.

But nothing occurred for the moment. To break the storm, making a great din, there dashed upon the lawn, in the nick of time, Commendator Borgalli accompanied by various members of the firm and employees from the manager’s office. Bertini and Polacco, who were with us, were swept away; but the managing director’s fierce reproaches were aimed also at the other two producers who were absent. The work was going to pieces! No control of production; the wildest confusion; a perfect Tower of Babel! Fifteen, twenty subjects left in the air; the companies scattered here, there and everywhere, when it had been announced, weeks ago, that they must be assembled and ready to get to work on the tiger film, on which thousands and thousands of lire had been spent! Some were off to the hills, some to the sea; eating their heads off! What was the use of keeping the tiger there!

There was still the whole part of the actor who was to kill it wanting? And where was the actor? Oh, he had just arrived, had he? How was that? Where had he been?

Actors, supers, scene-painters had come pouring in a crowd from every direction at the shouts of Commendator Borgalli, who had the satisfaction of measuring thus the extent of his own authority, and the fear and respect in which he was held, by the silence in which all these people stood round and then dispersed, when he concluded his harangue with the words:

“To your work! Get along back to work!”

There vanished from the lawn, as though it had been first of all submerged by this tide of people, then carried away by their ebb, every trace of the–shall we say–dramatic situation of a moment earlier; there, in the foreground, the Nestoroff and Carlo Ferro; beyond them, Nuti, solitary, apart, under the trees. The ground lay empty before us. I heard Signorina Luisetta sobbing by my side:

“Oh, heavens, oh, heavens,” and she wrung her hands. “Oh, heavens, what next? What will happen next?”

I looked at her with irritation, but tried, nevertheless, to comfort her:

“Why, what do you want to happen? Keep calm! Didn’t you see? All arranged beforehand. … At least, that is my impression. Yes, of course, keep calm! This surprise visit from Ferro…. I bet she knew all about it; I shouldn’t be surprised if she telegraphed to him yesterday to come; why yes, of course, to let him find her here engaged in a friendly conversation with Signor Nuti. You may be sure that is what it is.” “But he? He?”

“Who is “he”? Nuti?”

“If it is all a trick played by those two….”

“You are afraid he may notice it?”

“Yes! Yes!”

And the poor child began again to wring her hands.

“Well? And what if he does notice it?” said I. “You needn’t worry yourself; he won’t do anything. Depend upon it, this was arranged beforehand too.”

“By whom? By her? By that woman?”

“By that woman. She must first have made quite certain, before talking to him, that the other man would be able to turn up in time, without any danger to anyone; keep calm! Otherwise, Ferro would not have come upon the scene.”

We were quits. My statement embodied a profound contempt for Nuti; if Signorina Luisetta desired peace of mind, she was bound to accept it. She did so long to secure peace of mind, Signorina Luisetta; but on these terms, no; she would not. She shook her head violently: no, no.

There was nothing then to be done! But as a matter of fact, notwithstanding my faith in the Nestoroff’s cold perspicacity, in her power, when I reminded myself of Nuti’s desperate ravings, I did not feel any too certain myself that it was with him that we should concern ourselves. But this thought increased my irritation, already moved by the spectacle of that poor, terrified child. Despite my resolution to place and keep all these people in front of my machine as food for its hunger while I stood impassively turning the handle, I saw myself too obliged to continue to take an interest in them, to occupy myself with their affairs. There came back to me also the threats, the fierce protestations of the Nestoroff, that she feared nothing from any man, Because any other evil–a fresh crime, imprisonment, death itself–she would reckon as less than the evil which she was suffering in secret and preferred to endure. Had she perhaps suddenly grown tired of enduring it? Could this be the reason of her deciding yesterday, during my absence, to take the first step towards Nuti, in contradiction of what she had said to me the day before?

“No pity,” she had said to me, “neither for myself nor for him!”

Had she suddenly felt pity for herself? Not for him, certainly! But pity for herself means to her extricating herself by any means in her power, even at the cost of a crime, from the punishment she has inflicted on herself by living with Carlo Ferro. Suddenly making up her mind, she has gone to meet Nuti and has made Carlo Ferro return.

What does she want? What is going to happen next?

This is what happened, in the meantime, at midday beneath the pergola of the tavern, where–dressed some of them as Indians and others as English tourists–a crowd of actors and actresses from the four companies had assembled. All of them were or pretended to be infuriated and upset by Commendator Borgalli’s outburst that morning, and had for some time been taunting Carlo Ferro, letting him clearly understand that they were indebted to him for that outburst, he having first of all advanced all those silly claims and then tried to back out of the part allotted to him in the tiger film, and having left Rome, as though there were really a great risk attached to the killing of an animal cowed by all those months of captivity: an insurance for one hundred thousand lire, agreements, conditions, etc. Carlo Ferro was seated at a table, a little way off, with the Nestoroff. His face was yellow; it was quite evident that he was making an enormous effort to control himself; we all expected him at any moment to break out, to turn upon us. We were, therefore, left speechless at first when, instead of him, another man, to whom no one had given a thought, broke out all of a sudden and turned upon him, going up to the table at which Ferro and the Nestoroff were sitting. It was he, Nuti, as pale as death. In a silence that throbbed with a violent tension, a faint cry of terror was heard, to which Varia Nestoroff promptly replied by laying her hand, imperiously, upon Carlo Ferro’s arm.

Nuti said, looking Ferro straight in the face:

“Are you prepared to give up your place and your part to me? I promise before everyone here to take it on unconditionally.”

Carlo Ferro did not spring to his feet nor did he fly at the tempter. To the general amazement he sank down, sprawled awkwardly in his chair; leaned his head to one side, as though to look up at the speaker, and before replying raised the arm upon which the Nestoroff’s hand was resting, saying to her:

“Please….”

Then, turning to Nuti:

“You? My part? Why, I shall be delighted, my dear Sir. Because I am a fearful coward … you wouldn’t believe how frightened I am.

Delighted, my dear Sir, delighted!”

And he laughed, as I never saw a man laugh before!

His laughter made us all shudder, and, what with this general shudder and the whiplash of his laughter, Nuti was left quite helpless, his mind certainly vacillating from the impulse which had driven him to face his rival and had now collapsed, in the face of this awkward and teasingly submissive reception. He looked round him, and then, all of a sudden, at the sight of that pale, puzzled face, everyone began to laugh at him, broke into peals of loud, irrepressible laughter. The painful tension was broken in this way, in this enormous laugh of relief, at the challenger’s expense. Exclamations of derision sounded here and there, like jets of water amid the clamour of the laughter: “He’s cut a pretty figure!” “Caught in the trap!” “Like a mouse!”

Nuti would have done better to join in the laughter as well; but, most unfortunately, he chose to persist in the ridiculous part he had adopted, looking round for some one to whom he might cling, to keep himself afloat in this cyclone of hilarity, and stammered:

“Then… then, you agree?… I am to play the part… you agree!”

But even I myself, however reluctantly, at once took my eyes from him to look at the Nestoroff, whose dilated pupils gleamed with an evil light.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (32)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Half ons verstand

Mag ik een half ons verstand, drie kilo geluk, twee keer ingevroren welvaart, een paar pakjes behulpzaamheid, wat inlevingsvermogen, zeven vrienden, en wat appeltaart een enkel frietje, twee wodka-lime, en als het kan nog een verse bos cafeïne om de dag door te komen..

Wat sperziebonen om mijn vuist omheen te ballen, die heeft u ook?

Een heel oud vrouwtje om te kunnen concluderen dat ik nog zeeën van tijd heb.

Ik zal haar laten oversteken, aan de hand nemen en over het zebrapad helpen.

Mag ik zeven dwergen die mij kunnen dragen als ik moe ben.

En een man die van mij houdt. Die telkens als ik er niet meer in geloof op mij afrent en zegt: “Ik geloof in je, IK wél!”

Begrijpt u wat ik bedoel?

Hij moet onopvallend zijn op momenten dat ik hem niet nodig heb, en elke keer dat ik hem wel nodig heb op mij afrennen, al ben ik in Schagen.

Ik wil een vis die mij aankijkt, en waarvan ik merk dat hij mij echt aankijkt, als enige, hij hoeft zijn kieuwen maar te bewegen en ik weet wat ik vandaag moet gaan doen.

De wereld redden, ik wil de wereld redden. Hem eerst precies in het midden doorsnijden,

en dan oplepelen als een kiwi. Hij zal zoet smaken, met een warme vulling.

Hebt u daar een mes voor?

Alle mensen op de wereld zullen op een gerimpeld land wonen, ze houden elkaars handen vast om er niet vanaf te vallen.

Ik zoek ook nog muziek, muziek die ik kan vervormen naar mijn bui. Het is maar één cd en ik kan horen wat ik wil horen.

Kleuren, ik zoek kleuren die er niet bestaan, ik wil mij kunnen voorstellen dat er een kleur is die ik nog nooit heb gezien, en het is niet een soort oranje, of een soort blauw.

Het is iets anders.

Anders nog iets?

Ja iets racistisch, ik mag graag iets racistisch, een grote KKK muts die mode wordt, ik zal iedereen dwingen om hem te dragen.

Dan heb ik, als ik mij verveel, iets om naar te kijken.

Één dag almachtig, en ik ben de koning van het land, en het land is veel kleiner dan we tot nu toe dachten, het is een land met 6 miljard van dezelfde mensen die opeens de ingeving krijgen helemaal niet hetzelfde te zijn, ze zullen in de bomen klimmen en het volkslied zingen, de vogels zullen in huizen wonen en klagen over het weer en de belastingdienst.

Hiernaast deden ze er nogal moeilijk over, maar dit hadden ze wel!

Mag ik ook een vrachtschip met veertig indianen, die heel gelukkig in een container dansen, om de lijken heen van diegene die het niet overleefd hebben.

Daarbij zoek ik jaren naar een pil waarmee je de hele nacht door kan dansen, en niet omdat je heel veel energie hebt, maar omdat de tijd is gestopt.

In die tijd zal ik dansen met de rest. Het zal bezaaid zijn met allerlei.

Vooral met dictatoren die de avond van hun leven hebben, Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini hebben de grootste pret, discussietafels waar je kan aanschuiven, even bijkletsen met Julius Caesar, hij ziet er heerlijk uit, en heeft de gordijnen aan de muur om zich heen gedrapeerd.

Iedereen loopt langs de tafels, en speelt het grote ‘visies’ kwartet met de dictatoren.

Wie wint krijgt een kasteel.

Zodra de tijd het weer doet wonen alle dictatoren samen in het kasteel, hoog in de lucht.

Daar zullen ze neerkijken op het volk, zoals ze dat altijd al hebben gedaan. Ze zullen lachen. En wij beneden kwartetten met levens.

Mag ik van jou de boer? Dan krijg jij van mij de vrouw.

Nee doe mij maar een heer! Die krijg ik maar niet te pakken.

Een joker, een heer, wat is het verschil?

De mens heeft gewonnen.

En daarom zoek ik een trofee, Een trofee voor de gewonnen mens.

De mens die uit de polder is opgeklommen om zijn vinger in de dijk te doen omdat het water anders van hem wint.

Mag ik u dus met nadruk vragen om een berg om de trofee op te zetten.

Wie wil mag komen kijken.

Ik wil een wortel. Afgeblust met een beetje vrede..

Hier opeten alstublieft..

U hebt geen wortel?

Dan ga ik wel naar hiernaast..

Ik neem er ook één voor u mee.

Hier opeten alstublieft.

Esther Porcelijn 2012

Esther Porcelijn is stadsdichter van Tilburg

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

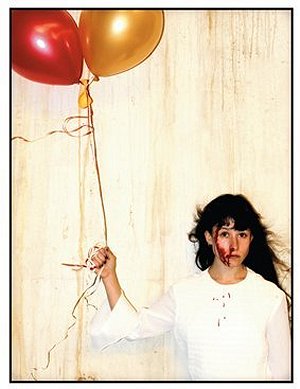

foto jef van kempen

Esther Porcelijn

Godvergeten Ironie

Je mag het wel benoemen

Maar je mag het niet zíjn

Je mag er wel om lachen

Maar je mag het niet willen

Je mag het wel afgrijselijk vinden

Maar je mag je er niet in verdiepen.

In een café praten heren over politiek.

Er wordt gestampt en gefoeterd

geproest en verloederd.

Maar niemand ziet de poster

op de achtergrond

in oranje, blauw en wit

waar iedereen precies

aan gekluisterd zit.

Zolang je maar

dingen zegt als:

“ze naaien ons toch wel!”

Met een grijns

en met een biertje.

En: “maarja.. ach”

of: “als het maar gezellig is!”

Zolang je dat maar zegt

ben je er tenminste

geen onderdeel van.

Hoef je niet bang te zijn

dat iemand echt

een goede vraag stelt.

Zolang je het parodieert

ben je het niet.

Esther Porcelijn poetry

stadsdichter Tilburg, 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Hondje

Gaan we naar buiten? Gaan we naar buiten? Jaa we gaan naar buiten! We gaan naar buiten, jaa! Mijn baas. Mijn geweldige baas. Zo loyaal en mooi en perfect en hij kan goed koken. Ik dacht dat ik altijd alleen zou blijven, dat niemand mij zou willen maar toen kwam hij en toen en toen en en en en. We gaan naar buiten!

Baas lacht. De tanden bloot. Grr. Ja baas. Grr. Boos! Ik ben ook boos. Grr. Samen boos! Jaa! Blote tanden baas! Heel bloot! Gaan we nog naar buiten baas? Ja? Ja! Baas begrijpt mij altijd goed. Weet precies wat ik leuk vind en ook wat ik niet leuk vind. Ik vind leuk: eten, en vooral lekker eten, stukje vlees, en ik vind leuk: goed geaaid worden en geborsteld, en een mooi bed en ik vind ook leuk: om anderen weg te jagen en het huis bewaken vind ik ook leuk. Wat ik niet leuk vind: katten, poedels en cavia’s. Die moeten maar weg, die zijn niet leuk. En ik vind ook niet leuk: anderen die de baas spelen. Ik ben de baas. IK ben de baas, en baas zegt ook altijd: “wij zijn de baas!” Ha! En ik vind raar eten ook niet leuk. Maar knakworsten wel, want die zijn normaal.

Ja, we gaan naar buiten! Samen de baas van buiten! Sinds ik baas heb, durf ik veel sneller te happen naar vreemden. Ik vond ze altijd al niet leuk, maar nu zijn we samen de baas. Ha! Baas is vrolijk boos. Hij heeft gekke blote tanden. Even hier plassen. En hier. Baas trekt me hard weg. Maar ik wil plassen baas! Baas zegt nee. Hij rinkelt met sleutels. Maar ik wil hier plassen, en hier nog een druppel. Zo. Toch gedaan. Nu ben ik de baas van de neuzen van de vreemden. Baas is ineens boos. Boze baas. Sorry baas echt sorry sorry maar ik wil nog even hier plassen. Baas. BAAS!! Ik wil hier nog even. Ah toeeee! Nou baahaas! Hij trekt mij mee. Hij laat mij nooit helemaal los. Maar ik kan toch zo ver lopen als baas wil, en dat is ver genoeg. Baas doet ineens gek. Rinkelt weer met zijn sleutels. Hoge piep. Grr.. boos. Hij tilt mij op en duwt mij in zijn wielenmachine. Dat gebruikt baas omdat hij niet zo hard kan rennen als ik. Elke dag gaat hij daarin en dan is hij lang weg en dan denk ik dat hij nooit meer terugkomt maar dan komt hij toch altijd weer terug. O, wat ben ik dan blij. Ik hoef nooit in de wielenmachine, alleen als ik ziek ben. Maar ik ben niet ziek en ik ben in de wielenmachine. Baas!! Baaaas!! Naast mij ligt een grote koffer, ik ruik eraan. Het ruikt naar, naar naar.. Die machine waar baas altijd zijn vacht in schoonmaakt! Waarom baas? Je hebt al een vacht aan! Één met bloemen erop vandaag.

Baas doet lief maar is boos. Ik zie dat. Hij praat nu lief zoals normaal maar ik zie aan zijn tanden dat hij boos is. Hij doet neplief. Stom.

Oo, maar andere wielenmachines! Die zijn ook leuk. Met baas ben ik niet meer alleen, zoef zoef zoef zoef zoef, overal wielenmachines en we gaan veel sneller dan ik kan rennen. Zoef! Samen de baas, baas? Samen de baas? Baas doet boos. Baas is boos. Hij roept “af” en nog wat andere dingen die ik niet versta. En hij wil niet dat we samen roepen. Alleen hij mag nu roepen. Goed dan. Ik ga wel een rondje om mijzelf heen waggelen in de wielenmachine. Nu lig ik beter. Ik lig goed. Maar dan stopt de wielenmachine. Oo ik mag eruit! Gaan we naar buiten baas? Gaan we naar buiten??

Ja, we gaan naar buiten. Jaa!

Baas pakt mij bij mijn kraag en trekt mij naar buiten. Grr baas, grr!!! Boos!

Hij slaat mij op mijn hoofd, dan draait het even. Whaa.. dat is gek, maar niet fijn gek, stom gek. We lopen naar een boom! Jaa, toch nog een plas doen! Whaa! Even een baas zijn van de neuzen! Jaa!! Jaa baas?

Maar hij pakt mij bij de kraag en ik hoor klik en dan zegt hij iets met veel û en o klanken.

Baas loopt weg.

BaBaas? Waar ga je heen baas? Ben je weer lang weg? Baas?? Ik loop achter baas aan maar ik word teruggetrokken. Hallo! Baas! Ik zit vast baas!

Baas doet niets. Hij gaat in zijn wielenmachine en zoeft weg.

Naast mij zoeven nog heel veel wielenmachines. Zoef-zoef-zoef-zoef. Hele hoge en lage tonen. Baas komt vast nog wel met een stuk vlees. Of een cavia om te bijten. Of een fris kussen waar ik dan de baas van mag zijn. Of met een aai.

Vast aan de boom. ’t Trekt aan mijn hals. Bah. Flauw. Stom. Baas was een nepbaas. Ik ben nu wel buiten, dat wel.

Esther Porcelijn 2012

Esther Porcelijn is stadsdichter van Tilburg

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

foto jef van kempen

H e r f s t a n g s t

Nog even niet de truien in

Nog even niet de vachten aan

Nog even geen verpulveren van bladeren

Nog even niet de kachelpijp

Nog even het laagje los.

Laat de stad nog éven zien,

Houd haar sluier op,

Al wordt ‘t zwaarder.

Herfst,

Geef mij nog één keer een peepshow.

Laat mij de dakpannen nog één keer roder zien.

Laat mij de grijze stenen nog één keer als zandsteen zien

en laat mij denken dat de huizen onvolledige piramides zijn.

Nog even geen chocoliedjes kerstcd’s.

Rillingen naakte bomen en natte laagjes

Druppels van mijn oren.

Koude winterlucht

die mijn hersenpan in tweeën snijdt

tot één knusse kopjes thee onder een dekentje, en één kersthatende.

Ik zet mijn rendieroren vast op.

Herfst,

Laat mij nog even niet veranderen,

Laat mij nog even geen herhaling zien

Van: “Ouwe koek en net als vorig jaar en zie je wel dacht ik al.”

Van: “Dat zei ik vroeger al, het ligt aan de rest aan de anderen

Het is de schuld van de buitenwereld, ik heb altijd gelijk en de rest verandert.”

Laat mij nog even alles zien alsof het nieuw is, dat er nog geen naam voor is.

Laat mij nog even bedenken hoe het moet heten.

Laat mij nog even niet die oude man worden die alles al benoemd heeft.

Wil je alsjeblieft nog even wachten?

Ik wacht dan met je mee dan turen we samen naar de wereld.

En noemen we alles oneindig vaak omdat we nog niks kennen.

Omdat we nog even niet binnen hoeven te zijn.

Omdat we nog even niet elk jaar hetzelfde ritueel.

Omdat we nog even geen grijsheid zien

Omdat we alle kleuren kunnen bedenken.

We kunnen alles bekijken, als jij ons de kleuren teruggeeft.

Nog even geen dikke sokken zelfde verhalen weer die éne oom.

Nog even niet koud nog even geen oude gedachten herinneringen.

Nog even niet?

Esther Porcelijn, stadsdichter Tilburg, 2012

(eerder gepubliceerd in het Brabants Dagblad)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (31)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

4

The villa.

Was this it? Is it possible that this was it?

And yet, there was nothing altered about it, or very little. Only that gate, a little higher, that pair of pillars, a little higher, replacing the little pillars of the old days, from one of which Grandfather Carlo had had the marble tablet with his name on it torn down.

But could this new gate have changed so completely the whole appearance of the old villa.

I saw that it was the same house, and it seemed to me impossible that it could be; I saw that it had remained much the same; why then did it appear a different house?

What a tragedy! The memory that seeks to live again, and cannot find its way among places that seem changed, that seem different, because our sentiments have changed, our sentiments are different. And yet I imagined that I had come hurrying to the villa with the sentiments of those days, the heart of long ago!

There it is. Knowing quite well that places have no other life, no other reality than that which we bestow on them, I saw myself obliged to admit with dismay, with infinite regret: “How I have changed!” The reality now is this. Something different.

I rang the bell. A different sound. But now I no longer knew whether this were due to some change in myself or to there being a different bell. How depressing!

There appeared an old gardener, without a coat, his shirt sleeves rolled up to the elbows, with a watering-can in his hand and a brimless hat perched on the crown of his head like a priest’s biretta.

“Donna Rosa Mirelli?”

“Who?”

“Is she dead?”

“Who do you mean?”

“Donna Rosa….”

“Ah, you want to know if she’s dead? How should I know?”

“She doesn’t live here any longer?”

“I don’t know what Donna Rosa you’re talking about. She doesn’t live here. It’s Pèrsico lives here, Don Filippo, the Cavaliere.”

“Has he a wife? Donna Duccella?”

“No, Sir. He’s a widower. He lives in town.”

“Then there’s no one living here?”

“There’s myself here, Nicola Tavuso, the gardener.”

The flowers in the borders on either side of the path from the gate to the house, red, yellow, white, hung motionless like discs of enamel in the limpid, silent air, dripping still from their recent bath. Flowers born yesterday, but upon those old borders. I looked at them: they disconcerted me; they said that it really was Tavuso who was living there now, as far as they were concerned, that he watered them well every morning, and that they were grateful to him for it: fresh, scentless, smiling with all those drops of water.

Fortunately, there appeared on the scene an old peasant woman, all breast and belly and hips, enormous under a big basket of greenstuff, with one eye shut, imprisoned beneath its swollen red lid, and the other keenly alert, clear, sky-blue, glazed with tears.

“Donna Rosa? Eh, the old mistress…. Many’s the long year since she left here…. Alive, yes, Sir, why not, poor soul? An old woman now… with the grandchild, yes, Sir, … Donna Duccella, yes, Sir…. Good folk! All for God…. No use for this world, or anything. … The house here they sold, yes, Sir, years ago, to Don Filippo the ‘surer’….”

“Pèrsico, the Cavaliere.”

“Go on, Don Nico, everyone knows Don Filippo! Now, Sir, you come along with me, and I’ll take you to Donna Rosa’s, next door to the New Church.”

Before leaving it, I took a final look at the villa. There was nothing left of it now; all of a sudden, nothing left; as though in a moment a cloud had passed from before my eyes. There it was: poverty-stricken, old, empty… nothing left! And in that case, perhaps,… Granny Rosa, Duccella…. Nothing left, of them either? Phantoms of a dream, my sweet phantoms, my dear phantoms, and nothing more!

I felt chilled. A bare, dull, icy hardness. That stout peasant’s words: “Good folk! All for God…. No use for this world….” I could feel the Church in them: hard, bare, icy. Across those green fields that smiled no longer…. But then?

I allowed myself to be led away. I cannot say what long account followed of that Don Filippo, who was aptly named ‘surer’, because… a never-ending because… the old Government … not him, no, his father… a man of God too, he was, but… his father, or so the story went, at least. And with my weariness, in my weariness, as I went, all those impressions of a sordid reality, hard, bare, icy,… a donkey covered in flies, that refused to move, the squalid road, a crumbling wall, the fetid odour of the stout woman…. Oh, what a temptation to dash to the station and take the train home again! Twice, three times, I was on the point of doing it; I checked myself; said to myself: “Let us see!”

A narrow stair, filthy, damp, almost in pitch darkness; and the old woman shouting to me from below:

“Straight on, keep straight on…. The second floor…. The bell is broken, Sir…. Knock loud; she doesn’t hear; knock loud.”

As though I were deaf too…. “Here?” I said to myself as I climbed the stair. “How have they come down to this? Lost all their money? Perhaps, two women by themselves…. That Don Filippo….”

On the landing of the second floor, two old doors, low in the lintel, freshly painted. By one hung the broken cord of its bell. The other had none. This one or that? I knocked first at this one, loud, with my fist, once, twice, thrice. I tried to pull the bell of the other: it did not ring. Was it this one, then? I knocked at it, loud, three times, four times…. No answer! But how in the world? Was Duccella deaf too? Or was she not living with her grandmother? I knocked again, more loudly. I was turning to go, when I heard on the stair the heavy step and breathing of somebody coming up. A short, thickset woman, in one of those garments that signify devotion, with the penitential cord round her waist: a coffee-coloured garment, of devotion to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Over her head and shoulders a ‘spagnoletta’, of black lace; in her hand, a fat prayer-book and the key of the house.

She stopped on the landing and looked at me with pale, lifeless eyes from a fat white face ending in a flaccid chin: on her upper lip, here and there, at the corners of her mouth, a few hairs sprouted. Duecella.

I had had enough; I wished only to make my escape! Ah, if only she had remained with that apathetic, stupid air with which she stopped short in front of me, still a little breathless, on the landing! But no: she wanted to entertain me, she wanted to be polite–she, now, like that–with those eyes that were no longer hers, with that fat, colourless nun’s face, with that short, stout body, and a voice, a voice and a kind of smile which I did not recognise: entertainment, compliments, ceremonies, as though I were shewing her a great condescension; and she was absolutely determined that I should come in and see her grandmother, who would be so delighted at the honour… why, yes, why, yes…. “Step inside, please, step inside….”

To remove her from my path I would have given her a shove, even at the risk of sending her flying downstairs! What a flabby horror! What an object! That deaf old woman, doddering with age, without a tooth in her head, with her pointed chin that protruded horribly towards the tip of her nose, chewing and mumbling, and her pallid tongue shewing between her flaccid, wrinkled lips, and those huge spectacles, monstrously enlarging her sightless eyes, scarred by an operation for cataract, between their sparse lashes, long as the feelers of an insect!

“You have made a position for yourself.” (With the soft Neapolitan z–‘posi-szi-o-ne’.)

She could think of nothing else to say to me.

I made my escape without its ever having occurred to me for a moment to suggest the plan for which I had come. What was I to say? What was there to do? Why ask them to tell me their story? If they had really fallen into poverty, as might be supposed from the appearance of the house? Perfectly content with everything, stolid and happy with God! Oh, what a horrible thing faith is! Duccella, the blushing flower… Granny Rosa, the garden of the villa with its jasmines….

In the train, I felt as though I were rushing towards madness, through the night. In what world was I? My travelling companion, a man of middle age, dark, with oval eyes, like discs of enamel, and hair that gleamed with oil, he belonged certainly to this world; firm and well established in the consciousness of his own calm and well cared for beastliness, he understood it all to perfection, without worrying about anything; he knew quite well all that it concerned him to know, where he was going, why he was travelling, the house at which he would arrive, the supper that was being prepared for him. But I? Was I of the same world? His journey and mine… his night and mine…. No, I had no time, no world, no anything. The train was his; he was travelling in it. How on earth did I come to be travelling in it also? What was I doing in the world in which he lived? How, in what respect was this night mine, when I had no means of living it, nothing to do with it? He had his night and all the time he wanted, that middle-aged man who was now twisting his neck about with signs of discomfort in his immaculate starched collar. No, no world, no time, nothing: I stood apart from everything, absent from myself and from life; and no longer knew where I was nor why I was there. Images I carried in me, not my own, of things and people; images, aspects, faces, memories of people and things which had never existed in reality, outside me, in the world which that gentleman saw round him and could touch. I had thought that I saw them, and could touch them also, but no, they were all imagination! I had never found them again, because they had never existed: phantoms, a dream…. But how could they have entered my mind? From where? Why? Was I there too, perhaps, then? Was there an I there then that now no longer existed? No; the middle-aged gentleman opposite to me told me, no: that other people existed, each in his own way and with his own space and time: I, no, I was not there; albeit, not being there, I should have found it hard to say where I really was and what I was, being thus without time or space.

I no longer understood anything. And I understood nothing when, arriving in Rome and coming to the house, about ten o’clock at night, I found in the dining-room, as gay as though nothing had happened, as though a new life had begun during my absence, Fabrizio Cavalena, a Doctor once more and restored to the bosom of his family, Aldo Nuti, Signorina Luisetta and Signora Nene, sitting round the table.

How? Why? What had happened?

I could not get rid of the impression that they were sitting there, gay and reconciled to one another, to make a fool of me, to reward me with the sight of their gaiety for the trouble that I had taken on their behalf; not only this, but that, knowing the state of mind in which I should return from the expedition, they had clubbed together to confound me utterly, making me find here also a reality such as I should never have expected.

More than any of the rest she, Signorina Luisetta, filled me with scorn, Signorina Luisetta who was impersonating Duccella in love, that Duccella, the blushing flower, of whom I had so often spoken to her! I would have liked to shout in her face how I had found her that afternoon, down at Sorrento, that Duccella, and to bid her give up this play-acting, which was an unworthy and grotesque contamination! And he too, the young man, who seemed by a miracle to be the same young man of years ago, I would have liked to shout in his face how and where I had found Duccella and Granny Rosa.

But good souls all of you! Down there, those two poor women, happy in God, and you happy here in the devil! Dear Cavalena, why yes, changed back not merely into a Doctor, but into a boy, a bridegroom, sitting by his bride! No, thank you: there is no place for me among you: don’t get up; don’t disturb yourselves: I am neither hungry nor thirsty! I can do without everything, I can. I have wasted upon you a little of what is of no use to me; you know it; a little of that heart which is of no use to me; because to me only my hand is of use: there is no need, therefore, to thank me! Indeed, you must excuse me if I have disturbed you. The fault is mine, for trying to interfere. Keep your seats, don’t get up, good night.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (31)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (30)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

3

The woman, as from the expression on my face she had at once realised my contempt for her, realised also the sense of degradation, the disgust that filled me, and the impulse that followed them.

The first, my contempt, had pleased her, possibly because she intended to make use of it for her own secret ends, submitting to it before my eyes with an air of pained humility. My sense of degradation, my disgust had not displeased her, perhaps because she herself felt them also and even more than I. What she resented was my sudden coldness, was seeing me all at once resume the cloak of my professional impassivity. And she too stiffened; looked at me coldly, and said:

“I expected to see you with Signorina Cavalena.”

“I gave her your note to read,” I replied. “She was just starting for the Kosmograph. I asked her to come.”

“She would not?”

“She did not like to. Perhaps in her capacity as a hostess…”

“Ah!” she threw back her head, “Why,” she went on, “that was precisely why I asked her to come, because she was acting as a hostess.”

“I pointed that out to her,” I said.

“And she did not think that she ought to come?”

I raised my hands.

She remained for a moment in thought; then, almost with a sigh, said:

“I have made a mistake. That day (do you remember?) when we all went together to the Bosco Sacro, she struck me as so charming, and pleased, too, at having my company, I realise that she was not a hostess then. But, surely, you are her guest also?”

She smiled, hoping to hurt me, as she aimed this question at me like a treacherous blow. And indeed, notwithstanding my determination to remain aloof from everything and everyone, I did feel hurt. So much so that I replied:

“But with two guests, as you must know, one may seem more important than the other.”

“I thought it was just the opposite,” she replied. “You don’t like her?”

“I neither like her nor dislike her, Signora.”

“Is that really so? Forgive me, I have no right to expect you to be frank with me. But I decided that I would be frank with you to-day.”

“And I have come…”

“Because Signorina Cavalena, as you tell me, wished to let it be seen that she attaches more importance to her other guest?”

“No, Signora. Signorina Cavalena said that she wished to remain apart.”

“And you too?”

“I have come.”

“And I thank you, most cordially. But you have come alone! And that–perhaps I am again mistaken–does not encourage me, not that I suppose for a moment, mind, that you, like Signorina Cavalena, attach more importance to the other guest; on the contrary….”

“You mean?”

“That this other guest is of no importance to you whatever; not only that, but that you would actually be glad if he were to meet with some accident, if only because Signorina Cavalena, by refusing to come with you, has shewn that she placed his interests above yours. Do I make myself clear?”

“Ah, no, Signora, you are mistaken!” I exclaimed sharply.

“It does not annoy you?”

“Not in the least. That is to say… well, to be honest,… it does annoy me, but it no longer affects me personally. I do really feel that I stand apart.”

“There, you see?” she interrupted me. “I feared as much, when I saw you come in by yourself. Confess that you would not feel yourself so much apart at this moment if the Signorina had come with you….”

“But if I have come myself!”

“To remain apart.”

“No, Signora. Listen, I have done more than you think. I have discussed the whole matter fully with that poor fellow and have tried in every possible way to make it clear to him that he has no right to expect anything after all that has happened, according to his own account at least.”

“What has he told you?” asked the Nestoreff, in a tone of determination, her face darkening.

“All sorts of silly things, Signora,” I replied. “He is raving. And his state is all the more alarming, believe me, since he is incapable, to my mind, of any really serious and deep feeling. As is already shewn by the fact of his coming here with a certain plan….”

“Of revenge?”

“Not exactly of revenge. He doesn’t know himself, even, what he feels. It is partly remorse … a remorse which he does not wish to feel; the irritating sting of which he feels only upon the surface, because, I repeat, he is equally incapable of a true, a sincere repentance which might mature him, make him recover his senses. And so it is partly the irritation of this remorse, which is maddening; partly rage, or rather (rage is too strong a word to apply to him) let us say vexation, a bitter vexation, which he does not admit, at having been tricked.”

“By me?”

“No. He will not admit it!”

“But you think so?”

“I think, Signora, that you never took him seriously, that you made use of him to break away from….”

I refused to utter the name: I pointed towards the six canvases. The Nestoroff knitted her brows, lowered her head. I stood gazing at her for a moment and, deciding to go on to the bitter end, pressed the point:

“He speaks of a betrayal. Of his betrayal by Mirelli, who killed himself because of the proof that he wished to give him that it was easy to obtain from you (if you will pardon my saying so) what Mirelli himself had failed to obtain.”

“Ah, he says that, does he?” broke from the Nestoroff.

“He says it, but he admits that he never obtained anything from you. He is raving. He wishes to attach himself to you, because if he goes on like this (he says) he will go mad.”

The Nestoroff looked at me almost with terror.

“You despise him?” she asked me.

I replied:

“I certainly do not admire him. Sometimes he makes me feel contempt for him, at other times pity.”

She sprang to her feet as though urged by an irrepressible impulse:

“I despise,” she said, “people who feel pity.”

I replied calmly:

“I can quite understand your feeling like that.”

“And you despise me!”

“No, Signora, far from it!”

She gazed at me for a while; smiled with a bitter disdain:

“You admire me, then?”

“I admire in you,” was my answer, “what may perhaps arouse contempt in other people; the contempt, for that matter, which you yourself wish to arouse in other people, so as not to provoke their pity.”

She gazed at me more fixedly; came forward until we stood face to face, and asked me:

“And don’t you mean by that, in a sense, that you also feel pity for me?”

“No, Signora. Admiration. Because you know how to punish yourself.”

“Indeed? so you understand that?” she said, with a change of colour, and a shudder, as though she had felt a sudden chill.

“For some time past, Signora.”

“In spite of everyone’s despising me?”

“Perhaps it was Just because everyone despised you.”

“I too have been aware of it for some time,” she said, holding out her hand and clasping mine tightly. “Thank you! But I can punish other people too, you know!” she at once added, in a threatening tone, withdrawing her hand and raising it in the air with outstretched forefinger. “I can punish other people too, without pity, because I have never sought any pity for myself and seek none now!”

She began to pace up and down the room, repeating:

“Without pity… without pity….”

Then, coming to a halt:

“You see?” she said, with an evil gleam in her eyes. “I do not admire you, for instance, who can overcome contempt with pity.”

“In that case, you ought not to admire yourself either,” I said with a smile. “Think for a moment, and then tell me why you invited me to

call upon you this morning.”

“You think it was out of pity for that… poor fellow, as you call him?”

“For him, or for some one else, or for yourself.”

“Nothing of the sort!” her denial was emphatic. “No! No! You are mistaken! Not a scrap of pity for anyone! I wish to be what I am; I intend to remain myself. I asked you to come in order that you might make him understand that I do not feel any pity for him and never shall!”

“Still, you do not wish to do him any injury.”

“I do indeed wish to do him an injury, by leaving him where he is and as he is.”

“But since you are so pitiless, would you not be doing him a greater injury if you were to call him back to you! Instead of driving him away….”

“That is because I wish, I myself, to remain as I am! I should be doing a greater injury to him, yes; but I should be conferring a benefit on myself, since I should take my revenge upon him instead of taking it upon myself. And what harm do you suppose could come to me from a man like him? I do not wish him any, you understand. Not because I feel any pity for him, but because I prefer not to feel any for myself. I am not interested in his sufferings, nor would it interest me to make him suffer more. He has had enough trouble. Let him go and weep somewhere else! I have no intention of weeping.”

“I am afraid,” I said, “that he has no longer any intention of weeping either.”

“Then what does he intend to do?”

“Well! Being, as I have already told you, incapable of doing anything, in the state of mind in which he is at present, he might unfortunately become capable of anything.”

“I am not afraid of him! The point is this, you see. I asked you to come and see me in order to tell you this, to make you understand this, so that you in turn may make him understand. I am not afraid that any harm can come to me from him, not even if he were to kill me, not even if, on his account, I had to go and end my days in prison! I am running that risk as well, you know! Deliberately, I have exposed myself to that risk as well. Because I know the man I have to deal with. And I am not afraid. I have let myself imagine that I was feeling a little afraid; imagining that, I have made an effort to send away from here a man who was threatening me, and everyone, with violence. It is not true. I have acted in cold blood, not out of fear! Any evil, even that, would count for less with me. Another crime, imprisonment, death itself, would be lesser evils to me than what I am now suffering and wish to keep on suffering. So take care not to try and arouse any pity in me for myself or for him. I have none! If you have any for him, you who have so much pity for everyone, make him, make him go away! That is what I want from you, simply because I am not afraid of anything!”

As she made this speech, she shewed in her whole person a desperate rage at not really feeling what she would have liked to feel.

I remained for some time in a state of perplexity in which dismay, anguish and also admiration were mingled; then I threw up my hands, and, so as not to make a vain promise, told her of my plan of going down to the villa by Sorrento.

She stood and listened to me, recoiling upon herself, perhaps to deaden the smart that the memory of that villa and of the two disconsolate women caused her; shut her eyes sorrowfully; shook her head; said:

“You will gain nothing.”

“Who knows?” I sighed. “One can at least try.”

She pressed my hand:

“Perhaps,” she said, “I too shall do something for you.”

I gazed at her face, with more consternation than curiosity:

“For me? What can that be?”

She shrugged her shoulders; made an effort to smile:

“I said, ‘perhaps’…. Something. You will see.”

“I thank you,” I added. “But really I do not see what you can possibly do for me. I have always asked so little of life, and I mean now to ask less than ever. Indeed, I ask it for nothing more, Signora.”

I said good-bye to her and left the house, my thoughts filled with this mysterious promise.

What does she propose to do? In cold blood, as I supposed at the time, she has sent away Carlo Ferro, with the knowledge, which does not cause her the slightest alarm, either for herself or for him or for the rest of us, that at any moment he may come rushing upon the scene here and commit a crime on his own account. How can she, knowing this, think of doing anything for me? What can she do? Where do I come in, in all this wretched entanglement? Does she intend to involve me in it in some way? With what object? She failed to get anything out of me, beyond an admission of my friendship long ago with Giorgio Mirelli and of a vague sentiment now for Signorina Luisetta. She cannot seize hold of me either by that friendship with a man who is now dead or by this sentiment which is already dying in me.

And yet, one never knows. I cannot set my mind at rest.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (30)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (29)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

2

A note from the Nestoroff, this morning at eight o’clock (a sudden and mysterious invitation to call upon her with Signorina Luisetta on our way to the Kosmograph), has made me postpone my departure.

I remained standing for a while with the note in my hand, not knowing what to make of it. Signorina Luisetta, already dressed to go out, came down the corridor past the door of my room; I called to her.

“Look at this. Read it.”

Her eyes ran down to the signature; as usual, she turned a deep red, then deadly pale; when she had finished reading it, she fixed her eyes on me with a hostile expression, her brow contracted in doubt and alarm, and asked in a faint voice:

“What does she want?”

I waved my hands in the air, not so much because I did not know what answer to make as in order to find out first what she thought about it.

“I am not going,” she said, with some confusion. “What can she want with me?”

“She must have heard,” I explained, “that he … that Signor Nuti is staying here, and…”

“And?”

“She may perhaps have some message to give, I don’t know… for him.”

“To me?”

“Why, I imagine, to you too, since she asks you to come with me….”

She controlled the trembling of her body; she did not succeed in controlling that of her voice:

“And where do I come in?”

“I don’t know; I don’t come in either,” I pointed out to her. “She wants us both….”

“And what message can she have to give me … for Signor Nuti?”

I shrugged my shoulders and looked at her with a cold firmness to call her back to herself and to indicate to her that she, in so far as her own person was concerned–she, as Signorina Luisetta, could have no reason to feel this aversion, this disgust for a lady for whose kindness she had originally been so grateful.

She understood, and grew even more disturbed.

“I suppose,” I went on, “that if she wishes to speak to you also, it will be for some good purpose; in fact, it is certain to be. You take offence….”

“Because… because I cannot… possibly … imagine…” she broke out, hesitating at first, then with headlong speed, her face catching fire as she spoke, “what in the world she can have to say to me, even if, as you suppose, it is for a good purpose. I…”

“Stand apart, like myself, from the whole affair, you mean?” I at once took her up, with increasing coldness. “Well, possibly she thinks that you may be able to help in some way….”

“No, no, I stand apart; you are quite right,” she hastened to reply, stung by my words. “I intend to remain apart, and not to have anything to do, so far as Signor Nuti is concerned, with this lady.”

“Do as you please,” I said. “I shall go alone. I need not remind you that it would be as well not to say anything to Nuti about this invitation.”

“Why, of course not!”

And she withdrew.

I remained for a long time considering, with the note in my hand, the attitude which, quite unintentionally, I had taken up in this short conversation with Signorina Luisetta.

The kindly intentions with which I had credited the Nestoroff had no other foundation than Signorina Luisetta’s curt refusal to accompany me in a secret manoeuvre which she instinctively felt to be directed against Nuti. I stood up for the Nestoroff simply because she, in inviting Signorina Luisetta to her house in my company, seems to me to have been intending to detach her from Nuti and to make her my companion, supposing her to be my friend.

Now, however, instead of letting herself be detached from Nuti, Signorina Luisetta has detached herself from me and has made me go alone to the Nestoroff. Not for a moment did she stop to consider the fact that she had been invited to come with me; the idea of keeping me company had never even occurred to her; she had eyes for none but Nuti, could think only of him; and my words had certainly produced no other effect on her than that of ranging me on the side of the Nestoroff against Nuti, and consequently against herself as well.

Except that, having now failed in the purpose for which I had credited the other with kindly intentions, I fell back into my original perplexity and in addition became a prey to a dull irritation and began to feel in myself also the most intense distrust of the Nestoroff. My irritation was with Signorina Luisetta, because, having failed in my purpose, I found myself obliged to admit that she had after all every reason to be distrustful. In fact, it suddenly became evident to me that I only needed Signorina Luisetta’s company to overcome all my distrust. In her absence, a feeling of distrust was beginning to take possession of me also, the distrust of a man who knows that at any moment he may be caught in a snare which has been spread for him with the subtlest cunning.

In this state of mind I went to call upon the Nestoroff, unaccompanied. At the same time I was urged by an anxious curiosity as to what she would have to say to me, and by the desire to see her at close quarters, in her own house, albeit I did not expect either from her or from the house any intimate revelation.

I have been inside many houses, since I lost my own, and in almost all of them, while waiting for the master or mistress of the house to appear, I have felt a strange sense of mingled annoyance and distress, at the sight of the more or less handsome furniture, arranged with taste, as though in readiness for a stage performance. This distress, this annoyance I feel more strongly than other people, perhaps, because in my heart of hearts there lingers inconsolable the regret for my own old-fashioned little house, where everything breathed an air of intimacy, where the old sticks of furniture, lovingly cared for, invited us to a frank, familiar confidence and seemed glad to retain the marks of the use we had made of them, because in those marks, even if the furniture was slightly damaged by them, lingered our memories of the life we had lived with it, in which it had had a share. But really I can never understand how certain pieces of furniture can fail to cause if not actually distress at least annoyance, furniture with which we dare not venture upon any confidence, because it seems to have been placed there to warn us with its rigid, elegant grace, that our anger, our grief, our joy must not break bounds, nor rage and struggle, nor exult, but must be controlled by the rules of good breeding. Houses made for the rest of the world, with a view to the part that we intend to play in society; houses of outward appearance, where even the furniture round us can make us blush if we happen for a moment to find ourselves behaving in some fashion that is not in keeping with that appearance nor consistent with the part that we have to play.

I knew that the Nestoroff lived in an expensive furnished flat in Via Mecenate. I was shewn by the maid (who had evidently been warned of my coming) into the drawing-room; but the maid was a trifle disconcerted owing to this previous warning, since she expected to see me arrive with a young lady. You, to the people who do not know you, and they are so many, have no other reality than that of your light trousers or your brown greatcoat or your “English” moustache. I to this maid was a person who was to come with a young lady. Without the young lady, I might be some one else. Which explains why, at first, I was left standing outside the door.

“Alone? And your little friend?” the Nestoroff was asking me a moment later in the drawing-room. But the question, when half uttered, between the words “your” and “little,” sank, or rather died away in a sudden change of feeling. The word “friend” was barely audible. This sudden change of feeling was caused by the pallor of my bewildered face, by the look in my eyes, opened wide in an almost savage stupefaction.

Looking at me, she at once guessed the reason of my pallor and bewilderment, and at once she too turned pale as death; her eyes became strangely clouded, her voice failed, and her whole body trembled before me as though I were a ghost.

The assumption of that body of hers into a prodigious life, in a light by which she could never, even in her dreams, have imagined herself as being bathed and warmed, in a transparent, triumphant harmony with a nature round about her, of which her eyes had certainly never beheld the jubilance of colours, was repeated six times over, by a miracle of art and love, in that drawing-room, upon six canvases by Giorgio Mirelli.

Fixed there for all time, in that divine reality which he had conferred on her, in that divine light, in that divine fusion of colours, the woman who stood before me was now what? Into what hideous bleakness, into what wretchedness of reality had she now fallen? And how could she have had the audacity to dye with that strange coppery colour the hair which there, on those six canvases, gave with its natural colour such frankness of expression to her earnest face, with its ambiguous smile, with its gaze plunged in the melancholy of a sad and distant dream!

She humbled herself, shrank back as though ashamed into herself, beneath my gaze which must certainly have expressed a pained contempt. From the way in which she looked at me, from the sorrowful contraction of her eyebrows and lips, from her whole attitude I gathered that not only did she feel that she deserved my contempt, but she accepted it and was grateful to me for it, since in that contempt, which she shared, she tasted the punishment of her crime and of her fall. She had spoiled herself, she had dyed her hair, she had brought herself to this wretched reality, she was living with a coarse and violent man, to make a sacrifice of herself: so much was evident; and she was determined that henceforward no one should approach her to deliver her from that self-contempt to which she had condemned herself, in which she reposed her pride, because only in that firm and fierce determination to despise herself did she still feel herself worthy of the luminous dream, in which for a moment she had drawn breath and to which a living and perennial testimony remained to her in the prodigy of those six canvases.

Not the rest of the world, not Nuti, but she, she alone, of her own accord, doing inhuman violence to herself, had torn herself from that dream, had dashed headlong from it. Why? Ah, the reason, perhaps, was to be sought elsewhere, far away. Who knows the secret ways of the soul? The torments, the darkenings, the sudden, fatal determinations? The reason, perhaps, must be sought in the harm that men had done to her from her childhood, in the vices by which she had been ruined in her early, vagrant life, and which in her own conception of them had so outraged her heart that she no longer felt it to deserve that a young man should with his love rescue and ennoble it.

As I stood face to face with this woman so fallen, evidently most unhappy and by her unhappiness made the enemy of all mankind and most of all of herself, what a sense of degradation, of disgust assailed me suddenly at the thought of the vulgar pettiness of the relations in which I found myself involved, of the people with whom I had undertaken to deal, of the importance which I had bestowed and was bestowing upon them, their actions, their feelings! How idiotic that fellow Nuti appeared to me, and how grotesque in his tragic fatuity as a fashionable dandy, all crumpled and soiled in his starched finery clotted with blood! Idiotic and grotesque the Cavalena couple, husband and wife! Idiotic Polacco, with his air of an invincible leader of men! And idiotic above all my own part, the part which I had allotted to myself of a comforter on the one hand, on the other of the guardian, and, in my heart of hearts, the saviour of a poor little girl, whom the sad, absurd confusion of her family life had led also to assume a part almost identical with my own; namely that of the phantom saviour of a young man who did not wish to be saved!

I felt myself, all of a sudden, alienated by this disgust from everyone and everything, including myself, liberated and so to speak emptied of all interest in anything or anyone, restored to my function as the impassive manipulator of a photographic machine, recaptured only by my original feeling, namely that all this clamorous and dizzy mechanism of life can produce nothing now but stupidities. Breathless and grotesque stupidities! What men, what intrigues, what life, at a time like this? Madness, crime or stupidity. A cinematographic life? Here, for instance: this woman who stood before me, with her coppery hair. There, on the six canvases, the art, the luminous dream of a young man who was unable to live at a time like this. And here, the woman, fallen from that dream, fallen from art to the cinematograph. Up, then, with a camera and turn the handle! Is there a drama here? Behold the principal character.

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (29)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (27)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

5

I have landed in a regular volcanic region. Eruptions and earthquakes without end. A big volcano, apparently snow-clad but inwardly in perpetual ebullition, Signora Nene. That one knew. But now there has come to light, unexpectedly, and has given its first eruption a little volcano, in whose bowels the fire has been lurking, hidden and threatening, albeit kindled but a few days ago.

The cataclysm was brought about by a visit from Polacco, this morning. Having come to persist in his task of persuading Nuti that he ought to leave Rome and return to Naples, to complete his convalescence, and after that should resume his travels, to distract his mind and be cured altogether, he had the painful surprise of finding Nuti up, as pale as death, with his moustache shaved clean to shew his firm intention of beginning at once, this very day, his career as an actor with the Kosmograph.

He shaved his moustache himself, as soon as he left his bed. It came as a surprise to all of us as well, because only last night the Doctor ordered him to keep absolutely quiet, to rest and not to leave his bed, except for an hour or so before noon; and last night he promised to obey these instructions.

We stood open-mouthed when we saw him appear shaved like that, completely altered, with that face of death, still not very steady on his legs, exquisitely attired.

He had cut himself slightly in shaving, at the left corner of his mouth; and the dried blood, blackening the cut, stood out against the chalky pallor of his face. His eyes, which now seemed enormous, with their lower lids stretched, as it were, by his loss of flesh, so as to shew the white of the eyeball beneath the line of the cornea, wore in confronting our pained stupefaction a terrible, almost a wicked expression of dark contempt and hatred.

“What in the world…” exclaimed Polacco.

He screwed up his face, almost baring his teeth, and raised his hands, with a nervous tremor in all his fingers; then, in the lowest of tones, indeed almost without speaking, he said:

“Leave me, leave me alone!”

“But you aren’t fit to stand!” Polacco shouted at him.

He turned and looked at him suspiciously:

“I can stand. Don’t worry me. I have… I have to go out… for a breath of air.”

“Perhaps it is a little soon, you know,” Cavalena tried to intervene, “if you will allow me….”

“But I tell you, I want to go out!” Nuti cut him short, barely tempering with a wry smile the irritation that was apparent in his voice.

This irritation springs from his desire to tear himself away from the attentions which we have been paying him recently, and which may have given us (though not me, I assure you) the illusion that he in a sense belongs to us from now onwards, is one of ourselves. He feels that this desire is held in check by his respect for the debt of gratitude which he owes to us, and sees no other way of breaking that bond of respect than by shewing indifference and contempt for his own health and welfare, so that we may begin to feel a resentment for the attentions we have paid him, and this resentment, at once creating a breach between him and ourselves, may absolve him from that debt of gratitude. A man in that state of mind dares not look people in the face And for that matter he, this morning, was not able to look any of us straight in the face.

Polacco, confronted by so definite a resolution, could see no other way out of the difficulty than to post round about him to watch, and, if need be, to defend him, as many of us as possible, and principally one who more than any of us has shewn pity for him and to whom he therefore owes a greater consideration; and, before going off with him, begged Cavalena emphatically to follow them at once to the Kosmograph, with Signorina Luisetta and myself. He said that Signorina Luisetta could not leave the film half-finished in which by accident she had been called upon to play a part, and that such a desertion would moreover be a real pity, because everyone was agreed that, in that short but by no means easy part, she had shewn a marvellous aptitude, which might lead, by his intervention, to a contract with the Kosmograph, an easy, safe and thoroughly respectable source of income, under her father’s protection.

Seeing Cavalena agree enthusiastically to this proposal, I was more than once on the point of going up to him to pluck him gently by the sleeve.

What I feared did, as a matter of fact, occur.

Signora Nene assumed that it was all a plot j engineered by her husband–Polacco’s morning call, Nuti’s sudden decision, the offer of a contract to her daughter–to enable him to go and flirt with the young actresses at the Kosmograph. And no sooner had Polacco left the house with Nuti than the volcano broke out in a tremendous eruption.

Cavalena at first tried to stand up to her, putting forward the anxiety for Nuti which obviously–as how in the world could anyone fail to see–had suggested this idea of a contract to Polacco. What? She didn’t care two pins about Nuti? Well, neither did he! Let Nuti go and hang himself a hundred times over, if once wasn’t enough! It was a question of seizing this golden opportunity of a contract for Luisetta! It would compromise her? How in the world could she be compromised, under the eyes of her father?

But presently, on Signora Nene’s part, argument ended, giving way to insults, vituperation, with such violence that finally Cavalena, indignant, exasperated, furious, rushed out of the house.

I ran after him down the stairs, along the street, doing everything in my power to stop him, repeating I don’t know how many times:

“But you are a Doctor! You are a Doctor!”