Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Tennessee’s Partner

Tennessee’s Partner

by Bret Harte

I do not think that we ever knew his real name. Our ignorance of it certainly never gave us any social inconvenience, for at Sandy Bar in 1854 most men were christened anew. Sometimes these appellatives were derived from some distinctiveness of dress, as in the case of “Dungaree Jack”; or from some peculiarity of habit, as shown in “Saleratus Bill,” so called from an undue proportion of that chemical in his daily bread; or for some unlucky slip, as exhibited in “The Iron Pirate,” a mild, inoffensive man, who earned that baleful title by his unfortunate mispronunciation of the term “iron pyrites.” Perhaps this may have been the beginning of a rude heraldry; but I am constrained to think that it was because a man’s real name in that day rested solely upon his own unsupported statement. “Call yourself Clifford, do you?” said Boston, addressing a timid newcomer with infinite scorn; “hell is full of such Cliffords!” He then introduced the unfortunate man, whose name happened to be really Clifford, as “Jay-bird Charley”–an unhallowed inspiration of the moment that clung to him ever after.

But to return to Tennessee’s Partner, whom we never knew by any other than this relative title; that he had ever existed as a separate and distinct individuality we only learned later. It seems that in 1853 he left Poker Flat to go to San Francisco, ostensibly to procure a wife. He never got any farther than Stockton. At that place he was attracted by a young person who waited upon the table at the hotel where he took his meals. One morning he said something to her which caused her to smile not unkindly, to somewhat coquettishly break a plate of toast over his upturned, serious, simple face, and to retreat to the kitchen. He followed her, and emerged a few moments later, covered with more toast and victory. That day week they were married by a justice of the peace, and returned to Poker Flat. I am aware that something more might be made of this episode, but I prefer to tell it as it was current at Sandy Bar–in the gulches and barrooms–where all sentiment was modified by a strong sense of humor.

Of their married felicity but little is known, perhaps for the reason that Tennessee, then living with his Partner, one day took occasion to say something to the bride on his own account, at which, it is said, she smiled not unkindly and chastely retreated– this time as far as Marysville, where Tennessee followed her, and where they went to housekeeping without the aid of a justice of the peace. Tennessee’s Partner took the loss of his wife simply and seriously, as was his fashion. But to everybody’s surprise, when Tennessee one day returned from Marysville, without his Partner’s wife–she having smiled and retreated with somebody else– Tennessee’s Partner was the first man to shake his hand and greet him with affection. The boys who had gathered in the canyon to see the shooting were naturally indignant. Their indignation might have found vent in sarcasm but for a certain look in Tennessee’s Partner’s eye that indicated a lack of humorous appreciation. In fact, he was a grave man, with a steady application to practical detail which was unpleasant in a difficulty.

Meanwhile a popular feeling against Tennessee had grown up on the Bar. He was known to be a gambler; he was suspected to be a thief. In these suspicions Tennessee’s Partner was equally compromised; his continued intimacy with Tennessee after the affair above quoted could only be accounted for on the hypothesis of a copartnership of crime. At last Tennessee’s guilt became flagrant. One day he overtook a stranger on his way to Red Dog. The stranger afterward related that Tennessee beguiled the time with interesting anecdote and reminiscence, but illogically concluded the interview in the following words: “And now, young man, I’ll trouble you for your knife, your pistols, and your money. You see your weppings might get you into trouble at Red Dog, and your money’s a temptation to the evilly disposed. I think you said your address was San Francisco. I shall endeavor to call.” It may be stated here that Tennessee had a fine flow of humor, which no business preoccupation could wholly subdue.

This exploit was his last. Red Dog and Sandy Bar made common cause against the highwayman. Tennessee was hunted in very much the same fashion as his prototype, the grizzly. As the toils closed around him, he made a desperate dash through the Bar, emptying his revolver at the crowd before the Arcade Saloon, and so on up Grizzly Canyon; but at its farther extremity he was stopped by a small man on a gray horse. The men looked at each other a moment in silence. Both were fearless, both self-possessed and independent; and both types of a civilization that in the seventeenth century would have been called heroic, but, in the nineteenth, simply “reckless.” “What have you got there?–I call,” said Tennessee, quietly. “Two bowers and an ace,” said the stranger, as quietly, showing two revolvers and a bowie knife. “That takes me,” returned Tennessee; and with this gamblers’ epigram, he threw away his useless pistol, and rode back with his captor.

It was a warm night. The cool breeze which usually sprang up with the going down of the sun behind the chaparral-crested mountain was that evening withheld from Sandy Bar. The little canyon was stifling with heated resinous odors, and the decaying driftwood on the Bar sent forth faint, sickening exhalations. The feverishness of day, and its fierce passions, still filled the camp. Lights moved restlessly along the bank of the river, striking no answering reflection from its tawny current. Against the blackness of the pines the windows of the old loft above the express office stood out staringly bright; and through their curtainless panes the loungers below could see the forms of those who were even then deciding the fate of Tennessee. And above all this, etched on the dark firmament, rose the Sierra, remote and passionless, crowned with remoter passionless stars.

The trial of Tennessee was conducted as fairly as was consistent with a judge and jury who felt themselves to some extent obliged to justify, in their verdict, the previous irregularities of arrest and indictment. The law of Sandy Bar was implacable, but not vengeful. The excitement and personal feeling of the chase were over; with Tennessee safe in their hands they were ready to listen patiently to any defense, which they were already satisfied was insufficient. There being no doubt in their own minds, they were willing to give the prisoner the benefit of any that might exist. Secure in the hypothesis that he ought to be hanged, on general principles, they indulged him with more latitude of defense than his reckless hardihood seemed to ask. The Judge appeared to be more anxious than the prisoner, who, otherwise unconcerned, evidently took a grim pleasure in the responsibility he had created. “I don’t take any hand in this yer game,” had been his invariable but good-humored reply to all questions. The Judge–who was also his captor–for a moment vaguely regretted that he had not shot him “on sight” that morning, but presently dismissed this human weakness as unworthy of the judicial mind. Nevertheless, when there was a tap at the door, and it was said that Tennessee’s Partner was there on behalf of the prisoner, he was admitted at once without question. Perhaps the younger members of the jury, to whom the proceedings were becoming irksomely thoughtful, hailed him as a relief.

For he was not, certainly, an imposing figure. Short and stout, with a square face sunburned into a preternatural redness, clad in a loose duck “jumper” and trousers streaked and splashed with red soil, his aspect under any circumstances would have been quaint, and was now even ridiculous. As he stooped to deposit at his feet a heavy carpetbag he was carrying, it became obvious, from partially developed legends and inscriptions, that the material with which his trousers had been patched had been originally intended for a less ambitious covering. Yet he advanced with great gravity, and after having shaken the hand of each person in the room with labored cordiality, he wiped his serious, perplexed face on a red bandanna handkerchief, a shade lighter than his complexion, laid his powerful hand upon the table to steady himself, and thus addressed the Judge:

“I was passin’ by,” he began, by way of apology, “and I thought I’d just step in and see how things was gittin’ on with Tennessee thar– my pardner. It’s a hot night. I disremember any sich weather before on the Bar.”

He paused a moment, but nobody volunteering any other meteorological recollection, he again had recourse to his pocket handkerchief, and for some moments mopped his face diligently.

“Have you anything to say in behalf of the prisoner?” said the Judge, finally.

“Thet’s it,” said Tennessee’s Partner, in a tone of relief. “I come yar as Tennessee’s pardner–knowing him nigh on four year, off and on, wet and dry, in luck and out o’ luck. His ways ain’t allers my ways, but thar ain’t any p’ints in that young man, thar ain’t any liveliness as he’s been up to, as I don’t know. And you sez to me, sez you–confidential-like, and between man and man–sez you, ‘Do you know anything in his behalf?’ and I sez to you, sez I– confidential-like, as between man and man–‘What should a man know of his pardner?'”

“Is this all you have to say?” asked the Judge impatiently, feeling, perhaps, that a dangerous sympathy of humor was beginning to humanize the Court.

“Thet’s so,” continued Tennessee’s Partner. “It ain’t for me to say anything agin’ him. And now, what’s the case? Here’s Tennessee wants money, wants it bad, and doesn’t like to ask it of his old pardner. Well, what does Tennessee do? He lays for a stranger, and he fetches that stranger. And you lays for HIM, and you fetches HIM; and the honors is easy. And I put it to you, bein’ a far-minded man, and to you, gentlemen, all, as far-minded men, ef this isn’t so.”

“Prisoner,” said the Judge, interrupting, “have you any questions to ask this man?”

“No! no!” continued Tennessee’s Partner, hastily. “I play this yer hand alone. To come down to the bedrock, it’s just this: Tennessee, thar, has played it pretty rough and expensive-like on a stranger, and on this yer camp. And now, what’s the fair thing? Some would say more; some would say less. Here’s seventeen hundred dollars in coarse gold and a watch–it’s about all my pile–and call it square!” And before a hand could be raised to prevent him, he had emptied the contents of the carpetbag upon the table.

For a moment his life was in jeopardy. One or two men sprang to their feet, several hands groped for hidden weapons, and a suggestion to “throw him from the window” was only overridden by a gesture from the Judge. Tennessee laughed. And apparently oblivious of the excitement, Tennessee’s Partner improved the opportunity to mop his face again with his handkerchief.

When order was restored, and the man was made to understand, by the use of forcible figures and rhetoric, that Tennessee’s offense could not be condoned by money, his face took a more serious and sanguinary hue, and those who were nearest to him noticed that his rough hand trembled slightly on the table. He hesitated a moment as he slowly returned the gold to the carpetbag, as if he had not yet entirely caught the elevated sense of justice which swayed the tribunal, and was perplexed with the belief that he had not offered enough. Then he turned to the Judge, and saying, “This yer is a lone hand, played alone, and without my pardner,” he bowed to the jury and was about to withdraw when the Judge called him back. “If you have anything to say to Tennessee, you had better say it now.” For the first time that evening the eyes of the prisoner and his strange advocate met. Tennessee smiled, showed his white teeth, and, saying, “Euchred, old man!” held out his hand. Tennessee’s Partner took it in his own, and saying, “I just dropped in as I was passin’ to see how things was getting’ on,” let the hand passively fall, and adding that it was a warm night, again mopped his face with his handkerchief, and without another word withdrew.

The two men never again met each other alive. For the unparalleled insult of a bribe offered to Judge Lynch–who, whether bigoted, weak, or narrow, was at least incorruptible–firmly fixed in the mind of that mythical personage any wavering determination of Tennessee’s fate; and at the break of day he was marched, closely guarded, to meet it at the top of Marley’s Hill.

How he met it, how cool he was, how he refused to say anything, how perfect were the arrangements of the committee, were all duly reported, with the addition of a warning moral and example to all future evildoers, in the RED DOG CLARION, by its editor, who was present, and to whose vigorous English I cheerfully refer the reader. But the beauty of that midsummer morning, the blessed amity of earth and air and sky, the awakened life of the free woods and hills, the joyous renewal and promise of Nature, and above all, the infinite Serenity that thrilled through each, was not reported, as not being a part of the social lesson. And yet, when the weak and foolish deed was done, and a life, with its possibilities and responsibilities, had passed out of the misshapen thing that dangled between earth and sky, the birds sang, the flowers bloomed, the sun shone, as cheerily as before; and possibly the RED DOG CLARION was right.

Tennessee’s Partner was not in the group that surrounded the ominous tree. But as they turned to disperse attention was drawn to the singular appearance of a motionless donkey cart halted at the side of the road. As they approached, they at once recognized the venerable “Jenny” and the two-wheeled cart as the property of Tennessee’s Partner–used by him in carrying dirt from his claim; and a few paces distant the owner of the equipage himself, sitting under a buckeye tree, wiping the perspiration from his glowing face. In answer to an inquiry, he said he had come for the body of the “diseased,” “if it was all the same to the committee.” He didn’t wish to “hurry anything”; he could “wait.” He was not working that day; and when the gentlemen were done with the “diseased,” he would take him. “Ef thar is any present,” he added, in his simple, serious way, “as would care to jine in the fun’l, they kin come.” Perhaps it was from a sense of humor, which I have already intimated was a feature of Sandy Bar–perhaps it was from something even better than that; but two-thirds of the loungers accepted the invitation at once.

It was noon when the body of Tennessee was delivered into the hands of his Partner. As the cart drew up to the fatal tree, we noticed that it contained a rough, oblong box–apparently made from a section of sluicing and half-filled with bark and the tassels of pine. The cart was further decorated with slips of willow, and made fragrant with buckeye blossoms. When the body was deposited in the box, Tennessee’s Partner drew over it a piece of tarred canvas, and gravely mounting the narrow seat in front, with his feet upon the shafts, urged the little donkey forward. The equipage moved slowly on, at that decorous pace which was habitual with “Jenny” even under less solemn circumstances. The men–half curiously, half jestingly, but all good-humoredly–strolled along beside the cart; some in advance, some a little in the rear of the homely catafalque. But, whether from the narrowing of the road or some present sense of decorum, as the cart passed on, the company fell to the rear in couples, keeping step, and otherwise assuming the external show of a formal procession. Jack Folinsbee, who had at the outset played a funeral march in dumb show upon an imaginary trombone, desisted, from a lack of sympathy and appreciation–not having, perhaps, your true humorist’s capacity to be content with the enjoyment of his own fun.

The way led through Grizzly Canyon–by this time clothed in funereal drapery and shadows. The redwoods, burying their moccasined feet in the red soil, stood in Indian file along the track, trailing an uncouth benediction from their bending boughs upon the passing bier. A hare, surprised into helpless inactivity, sat upright and pulsating in the ferns by the roadside as the cortege went by. Squirrels hastened to gain a secure outlook from higher boughs; and the bluejays, spreading their wings, fluttered before them like outriders, until the outskirts of Sandy Bar were reached, and the solitary cabin of Tennessee’s Partner.

Viewed under more favorable circumstances, it would not have been a cheerful place. The unpicturesque site, the rude and unlovely outlines, the unsavory details, which distinguish the nest-building of the California miner, were all here, with the dreariness of decay superadded. A few paces from the cabin there was a rough enclosure, which in the brief days of Tennessee’s Partner’s matrimonial felicity had been used as a garden, but was now overgrown with fern. As we approached it we were surprised to find that what we had taken for a recent attempt at cultivation was the broken soil about an open grave.

The cart was halted before the enclosure; and rejecting the offers of assistance with the same air of simple self-reliance he had displayed throughout, Tennessee’s Partner lifted the rough coffin on his back and deposited it, unaided, within the shallow grave. He then nailed down the board which served as a lid; and mounting the little mound of earth beside it, took off his hat, and slowly mopped his face with his handkerchief. This the crowd felt was a preliminary to speech; and they disposed themselves variously on stumps and boulders, and sat expectant.

“When a man,” began Tennessee’s Partner, slowly, “has been running free all day, what’s the natural thing for him to do? Why, to come home. And if he ain’t in a condition to go home, what can his best friend do? Why, bring him home! And here’s Tennessee has been running free, and we brings him home from his wandering.” He paused, and picked up a fragment of quartz, rubbed it thoughtfully on his sleeve, and went on: “It ain’t the first time that I’ve packed him on my back, as you see’d me now. It ain’t the first time that I brought him to this yer cabin when he couldn’t help himself; it ain’t the first time that I and ‘Jinny’ have waited for him on yon hill, and picked him up and so fetched him home, when he couldn’t speak, and didn’t know me. And now that it’s the last time, why”–he paused and rubbed the quartz gently on his sleeve–“you see it’s sort of rough on his pardner. And now, gentlemen,” he added, abruptly, picking up his long-handled shovel, “the fun’l’s over; and my thanks, and Tennessee’s thanks, to you for your trouble.”

Resisting any proffers of assistance, he began to fill in the grave, turning his back upon the crowd that after a few moments’ hesitation gradually withdrew. As they crossed the little ridge that hid Sandy Bar from view, some, looking back, thought they could see Tennessee’s Partner, his work done, sitting upon the grave, his shovel between his knees, and his face buried in his red bandanna handkerchief. But it was argued by others that you couldn’t tell his face from his handkerchief at that distance; and this point remained undecided.

In the reaction that followed the feverish excitement of that day, Tennessee’s Partner was not forgotten. A secret investigation had cleared him of any complicity in Tennessee’s guilt, and left only a suspicion of his general sanity. Sandy Bar made a point of calling on him, and proffering various uncouth, but well-meant kindnesses. But from that day his rude health and great strength seemed visibly to decline; and when the rainy season fairly set in, and the tiny grass-blades were beginning to peep from the rocky mound above Tennessee’s grave, he took to his bed. One night, when the pines beside the cabin were swaying in the storm, and trailing their slender fingers over the roof, and the roar and rush of the swollen river were heard below, Tennessee’s Partner lifted his head from the pillow, saying, “It is time to go for Tennessee; I must put ‘Jinny’ in the cart”; and would have risen from his bed but for the restraint of his attendant. Struggling, he still pursued his singular fancy: “There, now, steady, ‘Jinny’–steady, old girl. How dark it is! Look out for the ruts–and look out for him, too, old gal. Sometimes, you know, when he’s blind-drunk, he drops down right in the trail. Keep on straight up to the pine on the top of the hill. Thar–I told you so!–thar he is–coming this way, too–all by himself, sober, and his face a-shining. Tennessee! Pardner!”

And so they met.

Bret Harte (1836-1902)

Tennessee’s Partner

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, Archive G-H, Bret Harte

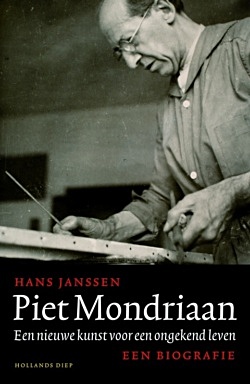

De Academie De Gouden Ganzenveer kent de Gouden Ganzenveer 2017 per acclamatie toe aan de literaire duizendpoot Arnon Grunberg. Gerdi Verbeet, Academievoorzitter De Gouden Ganzenveer maakte de laureaat bekend in het tv-programma JINEK.

De Academie De Gouden Ganzenveer kent de Gouden Ganzenveer 2017 per acclamatie toe aan de literaire duizendpoot Arnon Grunberg. Gerdi Verbeet, Academievoorzitter De Gouden Ganzenveer maakte de laureaat bekend in het tv-programma JINEK.

‘Arnon Grunberg wordt steeds unieker. Hij beoefent letterlijk alle literaire genres, van romans tot columnistiek, van poëzie tot reportagejournalistiek, van verhalen tot toneel. De traditionele grenzen tussen die genres lijken voor hem niet te bestaan: zijn grenzeloze creativiteit en expansieve literaire persoonlijkheid maken van de hele geschreven cultuur één groot gebied. Daarbij zijn het volume en de regelmaat van zijn jaarlijkse productie onwaarschijnlijk groot en bovenal zijn er weinig Nederlandse schrijvers van nu voor wie engagement zo’n vanzelfsprekende houding ten opzichte van de wereld is als voor Grunberg. Als embedded journalist, als betrokken romanschrijver, als kritisch ingesteld essayist is geen vluchtelingenzee hem te hoog, geen oorlogsgebied hem te gevaarlijk, geen politiek onderwerp hem te netelig. Arnon Grunberg laat als weinig andere auteurs zien hoezeer een vaardige pen geheel kan samenvallen met de persoonlijkheid van een schrijver die middenin de wereld staat. Om al die redenen is Grunberg de ideale kandidaat voor bekroning met de Gouden Ganzenveer 2017’ , aldus de Academie.

De prijsuitreiking vindt plaats op donderdag 6 april a.s. in Amsterdam. Een weerslag van deze bijeenkomst wordt vastgelegd in een speciale uitgave, die in de loop van het jaar zal verschijnen.

De Academie, een initiatief van het bestuur van stichting De Gouden Ganzenveer, kent jaarlijks deze culturele prijs toe. De leden zijn afkomstig uit de wereld van cultuur, wetenschap, politiek en het bedrijfsleven.

Met deze onderscheiding wil de Academie het geschreven en gedrukte woord in het Nederlands taalgebied onder de aandacht brengen.

Voorgaande laureaten zijn Xandra Schutte, Geert Mak, David Van Reybrouck, Ramsey Nasr, Annejet van der Zijl, Remco Campert, Joke van Leeuwen, Adriaan van Dis, Joost Zwagerman, Tom Lanoye, Peter van Straaten, Maria Goos, Kees van Kooten, Jan Blokker en Michaël Zeeman.

Arnon Grunberg (Amsterdam, 1971) is een literaire duizendpoot en vaak bekroonde romanschrijver, woonachtig te New York.

Arnon Grunberg (Amsterdam, 1971) is een literaire duizendpoot en vaak bekroonde romanschrijver, woonachtig te New York.

In 1994 verscheen zijn debuut Blauwe maandagen, gevolgd door onder andere Figuranten (1997), het boekenweekgeschenk De heilige Antonio (1998), Fantoompijn (2000) en De asielzoeker (2003).

In de periode 1999 tot 2005 publiceerde Grunberg tevens onder het heteroniem Marek van der Jagt de romans De geschiedenis van mijn kaalheid (1999), Gstaad 95-98 (2002), en het boekenweekessay Monogaam (2002). De geschiedenis van mijn kaalheid werd bekroond met de Anton Wachterprijs, een prijs voor het beste schrijversdebuut.

Voor Tirza (2006) ontving Grunberg zowel de Gouden Uil als de Libris Literatuurprijs. In 2007 en 2009 verschenen respectievelijk het brievenboek Omdat ik u begeer en een bundeling van zijn reportages, Kamermeisjes & soldaten. In 2010 en 2012 verschenen de romans Huid en Haar en De man zonder ziekte, en in 2015 de ideeënroman Het Bestand, een wetenschappelijk experiment over creativiteit. In het afgelopen jaar publiceerde hij de roman Moedervlekken en Aan nederlagen geen gebrek, een selectie brieven en documenten 1988-1994.

Grunberg schrijft columns, essays, recensies, korte verhalen en reportages voor veel kranten, weekbladen en literaire tijdschriften zoals NRC Handelsblad, Vrij Nederland, Humo en de VPRO-Gids. Daarnaast heeft hij bijdragen geleverd aan diverse Europese en Amerikaanse kranten en tijdschriften, zoals Die Welt, Die Zeit, Libération en The New York Times. Ook laat hij zich in het theater zien, met stukken waarin hij speelt met vorm.

Grunberg houdt een weblog bij op www.arnongrunberg.com, schrijft wekelijks als De mensendokter een bijdrage voor Vrij Nederland en heeft een dagelijkse column in de Volkskrant, ‘Voetnoot’, die in 2012 in boekvorm werd gebundeld. Zijn werk is vertaald in negenentwintig talen.

Op donderdag 6 april 2017 ontvangt hij de Gouden Ganzenveer.

# Uitgebreide informatie is te vinden op www.goudenganzenveer.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Archive G-H, Arnon Grunberg, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Joost Zwagerman, Literary Events, Remco Campert

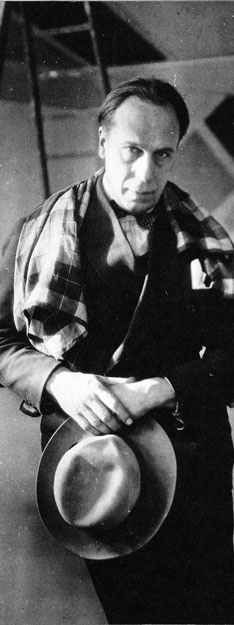

John Berger (London, November 5, 1926), art critic and author of Ways of Seeing, died in Paris (January 2, 2017)

John Berger (London, November 5, 1926), art critic and author of Ways of Seeing, died in Paris (January 2, 2017)

Berger’s best-known work was Ways of Seeing, a criticism of western cultural aesthetics. His novel G. won the Booker Prize. Half of the prize money Berger donated to the Black Panthers an radical African-American movement.

Berger began his career as a painter. But he also was a storyteller, novelist, essayist, screenwriter, dramatist and critic. He was one of the most internationally influential writers of the last fifty years.

His editor Tom Overton, who is writing John Berger’s biography, has said that the writer Berger “has let us know that art would enrich our lives”.

John Berger was author of: Another Way of Telling, About Looking, Photocopies, The Shape of a Pocket, And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief As Photos, Selected Essays of John Berger, Pig Earth, Once in Europa, King, Titian, Lilac and Flag, To the Wedding, Here Is Where We Meet, G., Pages of the Wound, Three Lives Of Lucie Cabrol.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, In Memoriam, John Berger

Sweethearts

Sweethearts

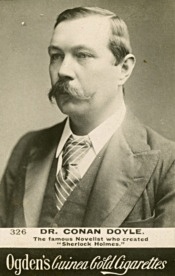

by Arthur Conan Doyle

It is hard for the general practitioner who sits among his patients both morning and evening, and sees them in their homes between, to steal time for one little daily breath of cleanly air. To win it he must slip early from his bed and walk out between shuttered shops when it is chill but very clear, and all things are sharply outlined, as in a frost. It is an hour that has a charm of its own, when, but for a postman or a milkman, one has the pavement to oneself, and even the most common thing takes an ever-recurring freshness, as though causeway, and lamp, and signboard had all wakened to the new day. Then even an inland city may seem beautiful, and bear virtue in its smoke-tainted air.

But it was by the sea that I lived, in a town that was unlovely enough were it not for its glorious neighbour. And who cares for the town when one can sit on the bench at the headland, and look out over the huge, blue bay, and the yellow scimitar that curves before it. I loved it when its great face was freckled with the fishing boats, and I loved it when the big ships went past, far out, a little hillock of white and no hull, with topsails curved like a bodice, so stately and demure. But most of all I loved it when no trace of man marred the majesty of Nature, and when the sun-bursts slanted down on it from between the drifting rainclouds. Then I have seen the further edge draped in the gauze of the driving rain, with its thin grey shading under the slow clouds, while my headland was golden, and the sun gleamed upon the breakers and struck deep through the green waves beyond, showing up the purple patches where the beds of seaweed are lying. Such a morning as that, with the wind in his hair, and the spray on his lips, and the cry of the eddying gulls in his ear, may send a man back braced afresh to the reek of a sick-room, and the dead, drab weariness of practice.

It was on such another day that I first saw my old man. He came to my bench just as I was leaving it. My eye must have picked him out even in a crowded street, for he was a man of large frame and fine presence, with something of distinction in the set of his lip and the poise of his head. He limped up the winding path leaning heavily upon his stick, as though those great shoulders had become too much at last for the failing limbs that bore them. As he approached, my eyes caught Nature’s danger signal, that faint bluish tinge in nose and lip which tells of a labouring heart.

“The brae is a little trying, sir,” said I. “Speaking as a physician, I should say that you would do well to rest here before you go further.”

He inclined his head in a stately, old-world fashion, and seated himself upon the bench. Seeing that he had no wish to speak I was silent also, but I could not help watching him out of the corners of my eyes, for he was such a wonderful survival of the early half of the century, with his low-crowned, curly-brimmed hat, his black satin tie which fastened with a buckle at the back, and, above all, his large, fleshy, clean-shaven face shot with its mesh of wrinkles. Those eyes, ere they had grown dim, had looked out from the box-seat of mail coaches, and had seen the knots of navvies as they toiled on the brown embankments. Those lips had smiled over the first numbers of “Pickwick,” and had gossiped of the promising young man who wrote them. The face itself was a seventy-year almanack, and every seam an entry upon it where public as well as private sorrow left its trace. That pucker on the forehead stood for the Mutiny, perhaps; that line of care for the Crimean winter, it may be; and that last little sheaf of wrinkles, as my fancy hoped, for the death of Gordon. And so, as I dreamed in my foolish way, the old gentleman with the shining stock was gone, and it was seventy years of a great nation’s life that took shape before me on the headland in the morning.

But he soon brought me back to earth again. As he recovered his breath he took a letter out of his pocket, and, putting on a pair of horn-rimmed eye-glasses, he read it through very carefully. Without any design of playing the spy I could not help observing that it was in a woman’s hand. When he had finished it he read it again, and then sat with the corners of his mouth drawn down and his eyes staring vacantly out over the bay, the most forlorn-looking old gentleman that ever I have seen. All that is kindly within me was set stirring by that wistful face, but I knew that he was in no humour for talk, and so, at last, with my breakfast and my patients calling me, I left him on the bench and started for home.

I never gave him another thought until the next morning, when, at the same hour, he turned up upon the headland, and shared the bench which I had been accustomed to look upon as my own. He bowed again before sitting down, but was no more inclined than formerly to enter into conversation. There had been a change in him during the last twenty-four hours, and all for the worse. The face seemed more heavy and more wrinkled, while that ominous venous tinge was more pronounced as he panted up the hill. The clean lines of his cheek and chin were marred by a day’s growth of grey stubble, and his large, shapely head had lost something of the brave carriage which had struck me when first I glanced at him. He had a letter there, the same, or another, but still in a woman’s hand, and over this he was moping and mumbling in his senile fashion, with his brow puckered, and the corners of his mouth drawn down like those of a fretting child. So I left him, with a vague wonder as to who he might be, and why a single spring day should have wrought such a change upon him.

So interested was I that next morning I was on the look out for him. Sure enough, at the same hour, I saw him coming up the hill; but very slowly, with a bent back and a heavy head. It was shocking to me to see the change in him as he approached.

“I am afraid that our air does not agree with you, sir,” I ventured to remark.

But it was as though he had no heart for talk. He tried, as I thought, to make some fitting reply, but it slurred off into a mumble and silence. How bent and weak and old he seemed—ten years older at the least than when first I had seen him! It went to my heart to see this fine old fellow wasting away before my eyes. There was the eternal letter which he unfolded with his shaking fingers. Who was this woman whose words moved him so? Some daughter, perhaps, or granddaughter, who should have been the light of his home instead of—— I smiled to find how bitter I was growing, and how swiftly I was weaving a romance round an unshaven old man and his correspondence. Yet all day he lingered in my mind, and I had fitful glimpses of those two trembling, blue-veined, knuckly hands with the paper rustling between them.

I had hardly hoped to see him again. Another day’s decline must, I thought, hold him to his room, if not to his bed. Great, then, was my surprise when, as I approached my bench, I saw that he was already there. But as I came up to him I could scarce be sure that it was indeed the same man. There were the curly-brimmed hat, and the shining stock, and the horn glasses, but where were the stoop and the grey-stubbled, pitiable face? He was clean-shaven and firm lipped, with a bright eye and a head that poised itself upon his great shoulders like an eagle on a rock. His back was as straight and square as a grenadier’s, and he switched at the pebbles with his stick in his exuberant vitality. In the button-hole of his well-brushed black coat there glinted a golden blossom, and the corner of a dainty red silk handkerchief lapped over from his breast pocket. He might have been the eldest son of the weary creature who had sat there the morning before.

I had hardly hoped to see him again. Another day’s decline must, I thought, hold him to his room, if not to his bed. Great, then, was my surprise when, as I approached my bench, I saw that he was already there. But as I came up to him I could scarce be sure that it was indeed the same man. There were the curly-brimmed hat, and the shining stock, and the horn glasses, but where were the stoop and the grey-stubbled, pitiable face? He was clean-shaven and firm lipped, with a bright eye and a head that poised itself upon his great shoulders like an eagle on a rock. His back was as straight and square as a grenadier’s, and he switched at the pebbles with his stick in his exuberant vitality. In the button-hole of his well-brushed black coat there glinted a golden blossom, and the corner of a dainty red silk handkerchief lapped over from his breast pocket. He might have been the eldest son of the weary creature who had sat there the morning before.

“Good morning, Sir, good morning!” he cried with a merry waggle of his cane.

“Good morning!” I answered, “how beautiful the bay is looking.”

“Yes, Sir, but you should have seen it just before the sun rose.”

“What, have you been here since then?”

“I was here when there was scarce light to see the path.”

“You are a very early riser.”

“On occasion, sir; on occasion!” He cocked his eye at me as if to gauge whether I were worthy of his confidence. “The fact is, sir, that my wife is coming back to me to day.”

I suppose that my face showed that I did not quite see the force of the explanation. My eyes, too, may have given him assurance of sympathy, for he moved quite close to me and began speaking in a low, confidential voice, as if the matter were of such weight that even the sea-gulls must be kept out of our councils.

“Are you a married man, Sir?”

“No, I am not.”

“Ah, then you cannot quite understand it. My wife and I have been married for nearly fifty years, and we have never been parted, never at all, until now.”

“Was it for long?” I asked.

“Yes, sir. This is the fourth day. She had to go to Scotland. A matter of duty, you understand, and the doctors would not let me go. Not that I would have allowed them to stop me, but she was on their side. Now, thank God! it is over, and she may be here at any moment.”

“Here!”

“Yes, here. This headland and bench were old friends of ours thirty years ago. The people with whom we stay are not, to tell the truth, very congenial, and we have, little privacy among them. That is why we prefer to meet here. I could not be sure which train would bring her, but if she had come by the very earliest she would have found me waiting.”

“In that case——” said I, rising.

“No, sir, no,” he entreated, “I beg that you will stay. It does not weary you, this domestic talk of mine?”

“On the contrary.”

“I have been so driven inwards during these few last days! Ah, what a nightmare it has been! Perhaps it may seem strange to you that an old fellow like me should feel like this.”

“It is charming.”

“No credit to me, sir! There’s not a man on this planet but would feel the same if he had the good fortune to be married to such a woman. Perhaps, because you see me like this, and hear me speak of our long life together, you conceive that she is old, too.”

He laughed heartily, and his eyes twinkled at the humour of the idea.

“She’s one of those women, you know, who have youth in their hearts, and so it can never be very far from their faces. To me she’s just as she was when she first took my hand in hers in ‘45. A wee little bit stouter, perhaps, but then, if she had a fault as a girl, it was that she was a shade too slender. She was above me in station, you know—I a clerk, and she the daughter of my employer. Oh! it was quite a romance, I give you my word, and I won her; and, somehow, I have never got over the freshness and the wonder of it. To think that that sweet, lovely girl has walked by my side all through life, and that I have been able——”

He stopped suddenly, and I glanced round at him in surprise. He was shaking all over, in every fibre of his great body. His hands were clawing at the woodwork, and his feet shuffling on the gravel. I saw what it was. He was trying to rise, but was so excited that he could not. I half extended my hand, but a higher courtesy constrained me to draw it back again and turn my face to the sea. An instant afterwards he was up and hurrying down the path.

A woman was coming towards us. She was quite close before he had seen her—thirty yards at the utmost. I know not if she had ever been as he described her, or whether it was but some ideal which he carried in his brain. The person upon whom I looked was tall, it is true, but she was thick and shapeless, with a ruddy, full-blown face, and a skirt grotesquely gathered up. There was a green ribbon in her hat, which jarred upon my eyes, and her blouse-like bodice was full and clumsy. And this was the lovely girl, the ever youthful! My heart sank as I thought how little such a woman might appreciate him, how unworthy she might be of his love.

She came up the path in her solid way, while he staggered along to meet her. Then, as they came together, looking discreetly out of the furthest corner of my eye, I saw that he put out both his hands, while she, shrinking from a public caress, took one of them in hers and shook it. As she did so I saw her face, and I was easy in my mind for my old man. God grant that when this hand is shaking, and when this back is bowed, a woman’s eyes may look so into mine.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

Sweethearts (#07)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka

Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer

Die Chinesische Mauer ist an ihrer nördlichsten Stelle beendet worden. Von Südosten und Südwesten wurde der Bau herangeführt und hier vereinigt. Dieses System des Teilbaues wurde auch im Kleinen innerhalb der zwei großen Arbeitsheere, des Ost- und des Westheeres, befolgt. Es geschah das so, daß Gruppen von etwa zwanzig Arbeitern gebildet wurden, welche eine Teilmauer von etwa fünfhundert Metern Länge aufzuführen hatten, eine Nachbargruppe baute ihnen dann eine Mauer von gleicher Länge entgegen. Nachdem dann aber die Vereinigung vollzogen war, wurde nicht etwa der Bau am Ende dieser tausend Meter wieder fortgesetzt, vielmehr wurden die Arbeitergruppen wieder in ganz andere Gegenden zum Mauerbau verschickt. Natürlich entstanden auf diese Weise viele große Lücken, die erst nach und nach langsam ausgefüllt wurden, manche sogar erst, nachdem der Mauerbau schon als vollendet verkündigt worden war. Ja, es soll Lücken geben, die überhaupt nicht verbaut worden sind, eine Behauptung allerdings, die möglicherweise nur zu den vielen Legenden gehört, die um den Bau entstanden sind, und die, für den einzelnen Menschen wenigstens, mit eigenen Augen und eigenem Maßstab infolge der Ausdehnung des Baues unnachprüfbar sind.

Nun würde man von vornherein glauben, es wäre in jedem Sinne vorteilhafter gewesen, zusammenhängend zu bauen oder wenigstens zusammenhängend innerhalb der zwei Hauptteile. Die Mauer war doch, wie allgemein verbreitet wird und bekannt ist, zum Schutze gegen die Nordvölker gedacht. Wie kann aber eine Mauer schützen, die nicht zusammenhängend gebaut ist. Ja, eine solche Mauer kann nicht nur nicht schützen, der Bau selbst ist in fortwährender Gefahr. Diese in öder Gegend verlassen stehenden Mauerteile können immer wieder leicht von den Nomaden zerstört werden, zumal diese damals, geängstigt durch den Mauerbau, mit unbegreiflicher Schnelligkeit wie Heuschrecken ihre Wohnsitze wechselten und deshalb vielleicht einen besseren Überblick über die Baufortschritte hatten als selbst wir, die Erbauer. Trotzdem konnte der Bau wohl nicht anders ausgeführt werden, als es geschehen ist. Um das zu verstehen, muß man folgendes bedenken: Die Mauer sollte zum Schutz für die Jahrhunderte werden; sorgfältigster Bau, Benützung der Bauweisheit aller bekannten Zeiten und Völker, dauerndes Gefühl der persönlichen Verantwortung der Bauenden waren deshalb unumgängliche Voraussetzung für die Arbeit. Zu den niederen Arbeiten konnten zwar unwissende Taglöhner aus dem Volke, Männer, Frauen, Kinder, wer sich für gutes Geld anbot, verwendet werden; aber schon zur Leitung von vier Taglöhnern war ein verständiger, im Baufach gebildeter Mann nötig; ein Mann, der imstande war, bis in die Tiefe des Herzens mitzufühlen, worum es hier ging. Und je höher die Leistung, desto größer die Anforderungen. Und solche Männer standen tatsächlich zur Verfügung, wenn auch nicht in jener Menge, wie sie dieser Bau hätte verbrauchen können, so doch in großer Zahl.

Man war nicht leichtsinnig an das Werk herangegangen. Fünfzig Jahre vor Beginn des Baues hatte man im ganzen China, das ummauert werden sollte, die Baukunst, insbesondere das Maurerhandwerk, zur wichtigsten Wissenschaft erklärt und alles andere nur anerkannt, soweit es damit in Beziehung stand. Ich erinnere mich noch sehr wohl, wie wir als kleine Kinder, kaum unserer Beine sicher, im Gärtchen unseres Lehrers standen, aus Kieselsteinen eine Art Mauer bauen mußten, wie der Lehrer den Rock schützte, gegen die Mauer rannte, natürlich alles zusammenwarf, und uns wegen der Schwäche unseres Baues solche Vorwürfe machte, daß wir heulend uns nach allen Seiten zu unseren Eltern verliefen. Ein winziger Vorfall, aber bezeichnend für den Geist der Zeit.

Ich hatte das Glück, daß, als ich mit zwanzig Jahren die oberste Prüfung der untersten Schule abgelegt hatte, der Bau der Mauer gerade begann. Ich sage Glück, denn viele, die früher die oberste Höhe der ihnen zugänglichen Ausbildung erreicht hatten, wußten jahrelang mit ihrem Wissen nichts anzufangen, trieben sich, im Kopf die großartigsten Baupläne, nutzlos herum und verlotterten in Mengen. Aber diejenigen, die endlich als Bauführer, sei es auch untersten Ranges, zum Bau kamen, waren dessen tatsächlich würdig. Es waren Maurer, die viel über den Bau nachgedacht hatten und nicht aufhörten, darüber nachzudenken, die sich mit dem ersten Stein, den sie in den Boden einsenken ließen, dem Bau verwachsen fühlten. Solche Maurer trieb aber natürlich, neben der Begierde, gründlichste Arbeit zu leisten, auch die Ungeduld, den Bau in seiner Vollkommenheit endlich erstehen zu sehen. Der Taglöhner kennt diese Ungeduld nicht, den treibt nur der Lohn, auch die oberen Führer, ja selbst die mittleren Führer sehen von dem vielseitigen Wachsen des Baues genug, um sich im Geiste dadurch kräftig zu halten. Aber für die unteren, geistig weit über ihrer äußerlich kleinen Aufgabe stehenden Männer, mußte anders vorgesorgt werden. Man konnte sie nicht zum Beispiel in einer unbewohnten Gebirgsgegend, hunderte Meilen von ihrer Heimat, Monate oder gar Jahre lang Mauerstein an Mauerstein fügen lassen; die Hoffnungslosigkeit solcher fleißigen, aber selbst in einem langen Menschenleben nicht zum Ziel führenden Arbeit hätte sie verzweifelt und vor allem wertloser für die Arbeit gemacht. Deshalb wählte man das System des Teilbaues. Fünfhundert Meter konnten etwa in fünf Jahren fertiggestellt werden, dann waren freilich die Führer in der Regel zu erschöpft, hatten alles Vertrauen zu sich, zum Bau, zur Welt verloren. Drum wurden sie dann, während sie noch im Hochgefühl des Vereinigungsfestes der tausend Meter Mauer standen, weit, weit verschickt, sahen auf der Reise hier und da fertige Mauerteile ragen, kamen an Quartieren höherer Führer vorüber, die sie mit Ehrenzeichen beschenkten, hörten den Jubel neuer Arbeitsheere, die aus der Tiefe der Länder herbeiströmten, sahen Wälder niederlegen, die zum Mauergerüst bestimmt waren, sahen Berge in Mauersteine zerhämmern, hörten auf den heiligen Stätten Gesänge der Frommen Vollendung des Baues erflehen. Alles dieses besänftigte ihre Ungeduld. Das ruhige Leben der Heimat, in der sie einige Zeit verbrachten, kräftigte sie, das Ansehen, in dem alle Bauenden standen, die gläubige Demut, mit der ihre Berichte angehört wurden, das Vertrauen, das der einfache, stille Bürger in die einstige Vollendung der Mauer setzte, alles dies spannte die Saiten der Seele. Wie ewig hoffende Kinder nahmen sie dann von der Heimat Abschied, die Lust, wieder am Volkswerk zu arbeiten, wurde unbezwinglich. Sie reisten früher von Hause fort, als es nötig gewesen wäre, das halbe Dorf begleitete sie lange Strecken weit. Auf allen Wegen Gruppen, Wimpel, Fahnen, niemals hatten sie gesehen, wie groß und reich und schön und liebenswert ihr Land war. Jeder Landmann war ein Bruder, für den man eine Schutzmauer baute, und der mit allem, was er hatte und war, sein Leben lang dafür dankte. Einheit! Einheit! Brust an Brust, ein Reigen des Volkes, Blut, nicht mehr eingesperrt im kärglichen Kreislauf des Körpers, sondern süß rollend und doch wiederkehrend durch das unendliche China.

Dadurch also wird das System des Teilbaues verständlich; aber es hatte doch wohl noch andere Gründe. Es ist auch keine Sonderbarkeit, daß ich mich bei dieser Frage so lange aufhalte, es ist eine Kernfrage des ganzen Mauerbaues, so unwesentlich sie zunächst scheint. Will ich den Gedanken und die Erlebnisse jener Zeit vermitteln und begreiflich machen, kann ich gerade dieser Frage nicht tief genug nachbohren.

Zunächst muß man sich doch wohl sagen, daß damals Leistungen vollbracht worden sind, die wenig hinter dem Turmbau von Babel zurückstehen, an Gottgefälligkeit allerdings, wenigstens nach menschlicher Rechnung, geradezu das Gegenteil jenes Baues darstellen. Ich erwähne dies, weil in den Anfangszeiten des Baues ein Gelehrter ein Buch geschrieben hat, in welchem er diese Vergleiche sehr genau zog. Er suchte darin zu beweisen, daß der Turmbau zu Babel keineswegs aus den allgemein behaupteten Ursachen nicht zum Ziele geführt hat, oder daß wenigstens unter diesen bekannten Ursachen sich nicht die allerersten befinden. Seine Beweise bestanden nicht nur aus Schriften und Berichten, sondern er wollte auch am Orte selbst Untersuchungen angestellt und dabei gefunden haben, daß der Bau an der Schwäche des Fundamentes scheiterte und scheitern mußte. In dieser Hinsicht allerdings war unsere Zeit jener längst vergangenen weit überlegen. Fast jeder gebildete Zeitgenosse war Maurer vom Fach und in der Frage der Fundamentierung untrüglich. Dahin zielte aber der Gelehrte gar nicht, sondern er behauptete, erst die große Mauer werde zum erstenmal in der Menschenzeit ein sicheres Fundament für einen neuen Babelturm schaffen. Also zuerst die Mauer und dann der Turm. Das Buch war damals in aller Hände, aber ich gestehe ein, daß ich noch heute nicht genau begreife, wie er sich diesen Turmbau dachte. Die Mauer, die doch nicht einmal einen Kreis, sondern nur eine Art Viertel- oder Halbkreis bildete, sollte das Fundament eines Turmes abgeben? Das konnte doch nur in geistiger Hinsicht gemeint sein. Aber wozu dann die Mauer, die doch etwas Tatsächliches war, Ergebnis der Mühe und des Lebens von Hunderttausenden? Und wozu waren in dem Werk Pläne, allerdings nebelhafte Pläne, des Turmes gezeichnet und Vorschläge bis ins einzelne gemacht, wie man die Volkskraft in dem kräftigen neuen Werk zusammenfassen solle?

Es gab – dieses Buch ist nur ein Beispiel – viel Verwirrung der Köpfe damals, vielleicht gerade deshalb, weil sich so viele möglichst auf einen Zweck hin zu sammeln suchten. Das menschliche Wesen, leichtfertig in seinem Grund, von der Natur des auffliegenden Staubes, verträgt keine Fesselung; fesselt es sich selbst, wird es bald wahnsinnig an den Fesseln zu rütteln anfangen und Mauer, Kette und sich selbst in alle Himmelsrichtungen zerreißen.

Es ist möglich, daß auch diese, dem Mauerbau sogar gegensätzlichen Erwägungen von der Führung bei der Festsetzung des Teilbaues nicht unberücksichtigt geblieben sind. Wir – ich rede hier wohl im Namen vieler – haben eigentlich erst im Nachbuchstabieren der Anordnungen der obersten Führerschaft uns selbst kennengelernt und gefunden, daß ohne die Führerschaft weder unsere Schulweisheit noch unser Menschenverstand für das kleine Amt, das wir innerhalb des großen Ganzen hatten, ausgereicht hätte. In der Stube der Führerschaft – wo sie war und wer dort saß, weiß und wußte niemand, den ich fragte – in dieser Stube kreisten wohl alle menschlichen Gedanken und Wünsche und in Gegenkreisen alle menschlichen Ziele und Erfüllungen. Durch das Fenster aber fiel der Abglanz der göttlichen Welten auf die Pläne zeichnenden Hände der Führerschaft.

Und deshalb will es dem unbestechlichen Betrachter nicht eingehen, daß die Führerschaft, wenn sie es ernstlich gewollt hätte, nicht auch jene Schwierigkeiten hätte überwinden können, die einem zusammenhängenden Mauerbau entgegenstanden. Bleibt also nur die Folgerung, daß die Führerschaft den Teilbau beabsichtigte. Aber der Teilbau war nur ein Notbehelf und unzweckmäßig. Bleibt die Folgerung, daß die Führerschaft etwas Unzweckmäßiges wollte. – Sonderbare Folgerung! – Gewiß, und doch hat sie auch von anderer Seite manche Berechtigung für sich. Heute kann davon vielleicht ohne Gefahr gesprochen werden. Damals war es geheimer Grundsatz Vieler, und sogar der Besten: Suche mit allen deinen Kräften die Anordnungen der Führerschaft zu verstehen, aber nur bis zu einer bestimmten Grenze, dann höre mit dem Nachdenken auf. Ein sehr vernünftiger Grundsatz, der übrigens noch eine weitere Auslegung in einem später oft wiederholten Vergleich fand: Nicht weil es dir schaden könnte, höre mit dem weiteren Nachdenken auf, es ist auch gar nicht sicher, daß es dir schaden wird. Man kann hier überhaupt weder von Schaden noch Nichtschaden sprechen. Es wird dir geschehen wie dem Fluß im Frühjahr. Er steigt, wird mächtiger, nährt kräftiger das Land an seinen langen Ufern, behält sein eignes Wesen weiter ins Meer hinein und wird dem Meere ebenbürtiger und willkommener. – So weit denke den Anordnungen der Führerschaft nach. – Dann aber übersteigt der Fluß seine Ufer, verliert Umrisse und Gestalt, verlangsamt seinen Abwärtslauf, versucht gegen seine Bestimmung kleine Meere ins Binnenland zu bilden, schädigt die Fluren, und kann sich doch für die Dauer in dieser Ausbreitung nicht halten, sondern rinnt wieder in seine Ufer zusammen, ja trocknet sogar in der folgenden heißen Jahreszeit kläglich aus. – So weit denke den Anordnungen der Führerschaft nicht nach.

Nun mag dieser Vergleich während des Mauerbaues außerordentlich treffend gewesen sein, für meinen jetzigen Bericht hat er doch zum mindesten nur beschränkte Geltung. Meine Untersuchung ist doch nur eine historische; aus den längst verflogenen Gewitterwolken zuckt kein Blitz mehr, und ich darf deshalb nach einer Erklärung des Teilbaues suchen, die weitergeht als das, womit man sich damals begnügte. Die Grenzen, die meine Denkfähigkeit mir setzt, sind ja eng genug, das Gebiet aber, das hier zu durchlaufen wäre, ist das Endlose.

Gegen wen sollte die große Mauer schützen? Gegen die Nordvölker. Ich stamme aus dem südöstlichen China. Kein Nordvolk kann uns dort bedrohen. Wir lesen von ihnen in den Büchern der Alten, die Grausamkeiten, die sie ihrer Natur gemäß begehen, machen uns aufseufzen in unserer friedlichen Laube. Auf den wahrheitsgetreuen Bildern der Künstler sehen wie diese Gesichter der Verdammnis, die aufgerissenen Mäuler, die mit hoch zugespitzten Zähnen besteckten Kiefer, die verkniffenen Augen, die schon nach dein Raub zu schielen scheinen, den das Maul zermalmen und zerreißen wird. Sind die Kinder böse, halten wir ihnen diese Bilder hin und schon fliegen sie weinend an unsern Hals. Aber mehr wissen wir von diesen Nordländern nicht. Gesehen haben wir sie nicht, und bleiben wir in unserem Dorf, werden wir sie niemals sehen, selbst wenn sie auf ihren wilden Pferden geradeaus zu uns hetzen und jagen, – zu groß ist das Land und läßt sie nicht zu uns, in die leere Luft werden sie sich verrennen.

Warum also, da es sich so verhält, verlassen wir die Heimat, den Fluß und die Brücken, die Mutter und den Vater, das weinende Weib, die lehrbedürftigen Kinder und ziehen weg zur Schule nach der fernen Stadt und unsere Gedanken sind noch weiter bei der Mauer im Norden? Warum? Frage die Führerschaft. Sie kennt uns. Sie, die ungeheure Sorgen wälzt, weiß von uns, kennt unser kleines Gewerbe, sieht uns alle zusammensitzen in der niedrigen Hütte und das Gebet, das der Hausvater am Abend im Kreise der Seinigen sagt, ist ihr wohlgefällig oder mißfällt ihr. Und wenn ich mir einen solchen Gedanken über die Führerschaft erlauben darf, so muß ich sagen, meiner Meinung nach bestand die Führerschaft schon früher, kam nicht zusammen, wie etwa hohe Mandarinen, durch einen schönen Morgentraum angeregt, eiligst eine Sitzung einberufen, eiligst beschließen, und schon am Abend die Bevölkerung aus den Betten trommeln lassen, um die Beschlüsse auszuführen, sei es auch nur um eine Illumination zu Ehren eines Gottes zu veranstalten, der sich gestern den Herren günstig gezeigt hat, um sie morgen, kaum sind die Lampions verlöscht, in einem dunklen Winkel zu verprügeln. Vielmehr bestand die Führerschaft wohl seit jeher und der Beschluß des Mauerbaues gleichfalls. Unschuldige Nordvölker, die glaubten, ihn verursacht zu haben, verehrungswürdiger, unschuldiger Kaiser, der glaubte, er hätte ihn angeordnet. Wir vom Mauerbau wissen es anders und schweigen.

Ich habe mich, schon damals während des Mauerbaues und nachher bis heute, fast ausschließlich mit vergleichender Völkergeschichte beschäftigt – es gibt bestimmte Fragen, denen man nur mit diesem Mittel gewissermaßen an den Nerv herankommt -und ich habe dabei gefunden, daß wir Chinesen gewisse volkliche und staatliche Einrichtungen in einzigartiger Klarheit, andere wieder in einzigartiger Unklarheit besitzen. Den Gründen, insbesondere der letzten Erscheinung, nachzuspüren, hat mich immer gereizt, reizt mich noch immer, und auch der Mauerbau ist von diesen Fragen wesentlich betroffen.

Nun gehört zu unseren allerundeutlichsten Einrichtungen jedenfalls das Kaisertum. In Peking natürlich, gar in der Hofgesellschaft, besteht darüber einige Klarheit, wiewohl auch diese eher scheinbar als wirklich ist. Auch die Lehrer des Staatsrechtes und der Geschichte an den hohen Schulen geben vor, über diese Dinge genau unterrichtet zu sein und diese Kenntnis den Studenten weitervermitteln zu können. Je tiefer man zu den unteren Schulen herabsteigt, desto mehr schwinden begreiflicherweise die Zweifel am eigenen Wissen, und Halbbildung wogt bergehoch um wenige seit Jahrhunderten eingerammte Lehrsätze, die zwar nichts an ewiger Wahrheit verloren haben, aber in diesem Dunst und Nebel auch ewig unerkannt bleiben.

Gerade über das Kaisertum aber sollte man meiner Meinung nach das Volk befragen, da doch das Kaisertum seine letzten Stützen dort hat. Hier kann ich allerdings wieder nur von meiner Heimat sprechen. Außer den Feldgottheiten und ihrem das ganze Jahr so abwechslungsreich und schön erfüllenden Dienst gilt unser Denken nur dem Kaiser. Aber nicht dem gegenwärtigen; oder vielmehr es hätte dem gegenwärtigen gegolten, wenn wir ihn gekannt, oder Bestimmtes von ihm gewußt hätten. Wir waren freilich – die einzige Neugierde, die uns erfüllte – immer bestrebt, irgend etwas von der Art zu erfahren, aber so merkwürdig es klingt, es war kaum möglich, etwas zu erfahren, nicht vom Pilger, der doch viel Land durchzieht, nicht in den nahen, nicht in den fernen Dörfern, nicht von den Schiffern, die doch nicht nur unsere Flüßchen, sondern auch die heiligen Ströme befahren. Man hörte zwar viel, konnte aber dem Vielen nichts entnehmen.

So groß ist unser Land, kein Märchen reicht an seine Größe, kaum der Himmel umspannt es – und Peking ist nur ein Punkt und das kaiserliche Schloß nur ein Pünktchen. Der Kaiser als solcher allerdings wiederum groß durch alle Stockwerke der Welt. Der lebendige Kaiser aber, ein Mensch wie wir, liegt ähnlich wie wir auf einem Ruhebett, das zwar reichlich bemessen, aber doch möglicherweise nur schmal und kurz ist. Wie wir streckt er manchmal die Glieder, und ist er sehr müde, gähnt er mit seinem zartgezeichneten Mund. Wie aber sollten wir davon erfahren – tausende Meilen im Süden -, grenzen wir doch schon fast ans tibetanischc Hochland. Außerdem aber käme jede Nachricht, selbst wenn sie uns erreichte, viel zu spät, wäre längst veraltet. Um den Kaiser drängt sich die glänzende und doch dunkle Menge des Hofstaates – Bosheit und Feindschaft im Kleid der Diener und Freunde -, das Gegengewicht des Kaisertums, immer bemüht, mit vergifteten Pfeilen den Kaiser von seiner Wagschale abzuschießen. Das Kaisertum ist unsterblich, aber der einzelne Kaiser fällt und stürzt ab, selbst ganze Dynastien sinken endlich nieder und veratmen durch ein einziges Röcheln. Von diesen Kämpfen und Leiden wird das Volk nie erfahren, wie Zu-spät-gekommene, wie Stadtfremde stehen sie am Ende der dichtgedrängten Seitengassen, ruhig zehrend vom mitgebrachten Vorrat, während auf dem Marktplatz in der Mitte weit vorn die Hinrichtung ihres Herrn vor sich geht.

Es gibt eine Sage, die dieses Verhältnis gut ausdrückt. Der Kaiser, so heißt es, hat Dir, dem Einzelnen, dem jämmerlichen Untertanen, dem winzig vor der kaiserlichen Sonne in die fernste Ferne geflüchteten Schatten, gerade Dir hat der Kaiser von seinem Sterbebett aus eine Botschaft gesendet. Den Boten hat er beim Bett niederknien lassen und ihm die Botschaft zugeflüstert; so sehr war ihm an ihr gelegen, daß er sich sie noch ins Ohr wiedersagen ließ. Durch Kopfnicken hat er die Richtigkeit des Gesagten bestätigt. Und vor der ganzen Zuschauerschaft seines Todes – alle hindernden Wände werden niedergebrochen und auf den weit und hoch sich schwingenden Freitreppen stehen im Ring die Großen des Reiches – vor allen diesen hat er den Boten abgefertigt. Der Bote hat sich gleich auf den Weg gemacht; ein kräftiger, ein unermüdlicher Mann; einmal diesen, einmal den andern Arm vorstreckend, schafft er sich Bahn durch die Menge; findet er Widerstand, zeigt er auf die Brust, wo das Zeichen der Sonne ist; er kommt auch leicht vorwärts wie kein anderer. Aber die Menge ist so groß; ihre Wohnstätten nehmen kein Ende. Öffnete sich freies Feld, wie würde er fliegen und bald wohl hörtest Du das herrliche Schlagen seiner Fäuste an Deiner Tür. Aber statt dessen, wie nutzlos müht er sich ab; immer noch zwängt er sich durch die Gemächer des innersten Palastes; niemals wird er sie überwinden; und gelänge ihm dies, nichts wäre gewonnen; die Treppen hinab müßte er sich kämpfen; und gelänge ihm dies, nichts wäre gewonnen; die Höfe wären zu durchmessen; und nach den Höfen der zweite umschließende Palast; und wieder Treppen und Höfe; und wieder ein Palast; und so weiter durch Jahrtausende; und stürzte er endlich aus dem äußersten Tor – aber niemals, niemals kann es geschehen -, liegt erst die Residenzstadt vor ihm, die Mitte der Welt, hochgeschüttet voll ihres Bodensatzes. Niemand dringt hier durch und gar mit der Botschaft eines Toten. – Du aber sitzt an Deinem Fenster und erträumst sie Dir, wenn der Abend kommt.

Genau so, so hoffnungslos und hoffnungsvoll, sieht unser Volk den Kaiser. Es weiß nicht, welcher Kaiser regiert, und selbst über den Namen der Dynastie bestehen Zweifel. In der Schule wird vieles dergleichen der Reihe nach gelernt, aber die allgemeine Unsicherheit in dieser Hinsicht ist so groß, daß auch der beste Schüler mit in sie gezogen wird. Längst verstorbene Kaiser werden in unseren Dörfern auf den Thron gesetzt, und der nur noch im Liede lebt, hat vor kurzem eine Bekanntmachung erlassen, die der Priester vor dem Altare verliest. Schlachten unserer ältesten Geschichte werden jetzt erst geschlagen und mit glühendem Gesicht fällt der Nachbar mit der Nachricht dir ins Haus. Die kaiserlichen Frauen, überfüttert in den seidenen Kissen, von schlauen Höflingen der edlen Sitten entfremdet, anschwellend in Herrschsucht, auffahrend in Gier, ausgebreitet in Wollust, verüben ihre Untaten immer wieder von neuem. Je mehr Zeit schon vergangen ist, desto schrecklicher leuchten alle Farben, und mit lautem Wehgeschrei erfährt einmal das Dorf, wie eine Kaiserin vor Jahrtausenden in langen Zügen ihres Mannes Blut trank.

So verfährt also das Volk mit den vergangenen, die gegenwärtigen Herrscher aber mischt es unter die Toten. Kommt einmal, einmal in einem Menschenalter, ein kaiserlicher Beamter, der die Provinz bereist, zufällig in unser Dorf, stellt im Namen der Regierenden irgendwelche Forderungen, prüft die Steuerlisten, wohnt dem Schulunterricht bei, befragt den Priester über unser Tun und Treiben, und faßt dann alles, ehe er in seine Sänfte steigt, in langen Ermahnungen an die herbeigetriebene Gemeinde zusammen, dann geht ein Lächeln über alle Gesichter, einer blickt verstohlen zum andern und beugt sich zu den Kindern hinab, um sich vom Beamten nicht beobachten zu lassen. Wie, denkt man, er spricht von einem Toten wie von einem Lebendigen, dieser Kaiser ist doch schon längst gestorben, die Dynastie ausgelöscht, der Herr Beamte macht sich über uns lustig, aber wir tun so, als ob wir es nicht merkten, um ihn nicht zu kränken. Ernstlich gehorchen aber werden wir nur unserem gegenwärtigen Herrn, denn alles andere wäre Versündigung. Und hinter der davoneilenden Sänfte des Beamten steigt irgendein willkürlich aus schon zerfallener Urne Gehobener aufstampfend als Herr des Dorfes auf.

Ähnlich werden die Leute bei uns von staatlichen Umwälzungen, von zeitgenössischen Kriegen in der Regel wenig betroffen. Ich erinnere mich hier an einen Vorfall aus meiner Jugend. In einer benachbarten, aber immerhin sehr weit entfernten Provinz war ein Aufstand ausgebrochen. Die Ursachen sind mir nicht mehr erinnerlich, sie sind hier auch nicht wichtig, Ursachen für Aufstände ergeben sich dort mit jedem neuen Morgen, es ist ein aufgeregtes Volk. Und nun wurde einmal ein Flugblatt der Aufständischen durch einen Bettler, der jene Provinz durchreist hatte, in das Haus meines Vaters gebracht. Es war gerade ein Feiertag, Gäste füllten unsere Stuben, in der Mitte saß der Priester und studierte das Blatt. Plötzlich fing alles zu lachen an, das Blatt wurde im Gedränge zerrissen, der Bettler, der allerdings schon reichlich beschenkt worden war, wurde mit Stößen aus dem Zimmer gejagt, alles zerstreute sich und lief in den schönen Tag. Warum? Der Dialekt der Nachbarprovinz ist von dem unseren wesentlich verschieden, und dies drückt sich auch in gewissen Formen der Schriftsprache aus, die für uns einen altertümlichen Charakter haben. Kaum hatte nun der Priester zwei derartige Seiten gelesen, war man schon entschieden. Alte Dinge, längst gehört, längst verschmerzt. Und obwohl – so scheint es mir in der Erinnerung – aus dem Bettler das grauenhafte Leben unwiderleglich sprach, schüttelte man lachend den Kopf und wollte nichts mehr hören. So bereit ist man bei uns, die Gegenwart auszulöschen.

Wenn man aus solchen Erscheinungen folgern wollte, daß wir im Grunde gar keinen Kaiser haben, wäre man von der Wahrheit nicht weit entfernt. Immer wieder muß ich sagen: Es gibt vielleicht kein kaisertreueres Volk als das unsrige im Süden, aber die Treue kommt dem Kaiser nicht zugute. Zwar steht auf der kleinen Säule am Dorfausgang der heilige Drache und bläst huldigend seit Menschengedenken den feurigen Atem genau in die Richtung von Peking – aber Peking selbst ist den Leuten im Dorf viel fremder als das jenseitige Leben. Sollte es wirklich ein Dorf geben, wo Haus an Haus steht, Felder bedeckend, weiter als der Blick von unserem Hügel reicht und zwischen diesen Häusern stünden bei Tag und bei Nacht Menschen Kopf an Kopf? Leichter als eine solche Stadt sich vorzustellen ist es uns, zu glauben, Peking und sein Kaiser wäre eines, etwa eine Wolke, ruhig unter der Sonne sich wandelnd im Laufe der Zeiten.

Die Folge solcher Meinungen ist nun ein gewissermaßen freies, unbeherrschtes Leben. Keineswegs sittenlos, ich habe solche Sittenreinheit, wie in meiner Heimat, kaum jemals angetroffen auf meinen Reisen. – Aber doch ein Leben, das unter keinem gegenwärtigen Gesetze steht und nur der Weisung und Warnung gehorcht, die aus alten Zeiten zu uns herüberreicht.

Ich hüte mich vor Verallgemeinerungen und behaupte nicht, daß es sich in allen zehntausend Dörfern unserer Provinz so verhält oder gar in allen fünfhundert Provinzen Chinas. Wohl aber darf ich vielleicht auf Grund der vielen Schriften, die ich über diesen Gegenstand gelesen habe, sowie auf Grund meiner eigenen Beobachtungen – besonders bei dem Mauerbau gab das Menschenmaterial dem Fühlenden Gelegenheit, durch die Seelen fast aller Provinzen zu reisen – auf Grund alles dessen darf ich vielleicht sagen, daß die Auffassung, die hinsichtlich des Kaisers herrscht, immer wieder und überall einen gewissen und gemeinsamen Grundzug mit der Auffassung in meiner Heimat zeigt. Die Auffassung will ich nun durchaus nicht als eine Tugend gelten lassen, im Gegenteil. Zwar ist sie in der Hauptsache von der Regierung verschuldet, die im ältesten Reich der Erde bis heute nicht imstande war oder dies über anderem vernachlässigte, die Institution des Kaisertums zu solcher Klarheit auszubilden, daß sie bis an die fernsten Grenzen des Reiches unmittelbar und unablässig wirke. Andererseits aber liegt doch auch darin eine Schwäche der Vorstellungs- oder Glaubenskraft beim Volke, welches nicht dazu gelangt, das Kaisertum aus der Pekinger Versunkenheit in aller Lebendigkeit und Gegenwärtigkeit an seine Untertanenbrust zu ziehen, die doch nichts besseres will, als einmal diese Berührung zu fühlen und an ihr zu vergehen.

Eine Tugend ist also diese Auffassung wohl nicht. Um so auffälliger ist es, daß gerade diese Schwäche eines der wichtigsten Einigungsmittel unseres Volkes zu sein scheint; ja, wenn man sich im Ausdruck soweit vorwagen darf, geradezu der Boden, auf dem wir leben. Hier einen Tadel ausführlich begründen, heißt nicht an unserem Gewissen, sondern, was viel ärger ist, an unseren Beinen rütteln. Und darum will ich in der Untersuchung dieser Frage vorderhand nicht weiter gehen.

Franz Kafka

(1883-1924)

Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer

fleursdumalnl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

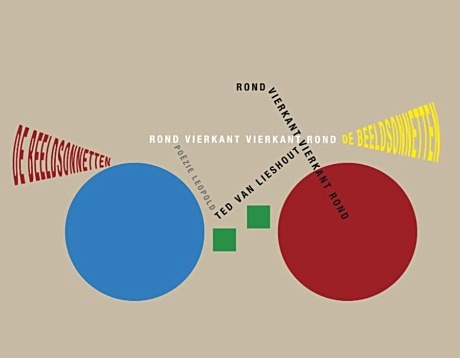

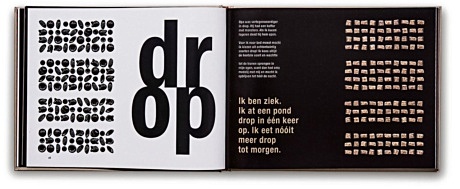

De Kunsthal Rotterdam presenteert het Locomotrutfantje, Moeder de Gans, Spartapiet, Cubaanse vlieg, Doorzager, Blauwwerker en meer beelden van Jules Deelder. Deelder, beter bekend als dichter en nachtburgemeester van Rotterdam, laat de poëzie van zijn verbeelding spreken. Zoals een echte dichter betaamt geeft hij zijn creaties de meest toepasselijke namen. In de tentoonstelling zijn elf unieke ‘Beelder’ te zien, gemaakt van kleurrijk plastic.

Sinds anderhalf jaar verzamelt J.A. Deelder pennen, cocktailstampertjes, injectiespuiten, pijpjes, rietjes, lepeltjes, tandenborstels, speelgoed en lensdopjes, om ze daarna op kleur te sorteren. Met lijm verwerkt Deelder al deze materialen tot driedimensionale objecten, waarmee hij een nieuwe dimensie aan zijn rijke oeuvre van poëzie en performances toevoegt. Hij zegt daar zelf over:

Je zit gewoon een beetje te klootzakke, en op een gegeven moment wordt het wat!

Jules Deelder

Ruimteschepen: Als Deelder’s dochter Ari in 2015 een film maakt over Willem Koopman alias Willem de wielrenner, vindt zij haar vader bereid een aantal ruimteschepen te maken zoals Willem altijd deed in de kroegen van Rotterdam. Koopman, een ex-wielrenner en voormalig zwerver met een bovennatuurlijke missie, zag Rotterdam als een ruimteschip dat elk moment uit het heelal geschoten kon worden. Deelder daarentegen ziet zijn creaties niet opstijgen tot in de verre uithoeken van het heelal, maar juist landen in de Kunsthal.

Over Jules Deelder: J.A. Deelder wordt in 1944 geboren als zoon van een Rotterdamse handelaar in vleeswaren. Sinds de vroege jaren zestig heeft Deelder nationale bekendheid als jazzconnaisseur, schrijver, dichter, performer en bovenal Rotterdammer. Zijn uitgesproken voorkeur voor zwarte kleding, vlinderbrillen, Sparta, Citroën en wielrennen maakt hem tot een graag geziene gast in tv- en radioprogramma’s.

Over Jules Deelder: J.A. Deelder wordt in 1944 geboren als zoon van een Rotterdamse handelaar in vleeswaren. Sinds de vroege jaren zestig heeft Deelder nationale bekendheid als jazzconnaisseur, schrijver, dichter, performer en bovenal Rotterdammer. Zijn uitgesproken voorkeur voor zwarte kleding, vlinderbrillen, Sparta, Citroën en wielrennen maakt hem tot een graag geziene gast in tv- en radioprogramma’s.

De Kunsthal Rotterdam is een van de toonaangevende culturele instellingen in Nederland, gelegen in het Museumpark in Rotterdam. Ontworpen door de beroemde architect Rem Koolhaas in 1992, biedt de Kunsthal zeven verschillende tentoonstellingsruimtes. Jaarlijks presenteert de Kunsthal een gevarieerd programma van circa 25 tentoonstellingen. Omdat er altijd meerdere tentoonstellingen tegelijk te bezichtigen zijn, biedt de Kunsthal een avontuurlijke reis door verschillende werelddelen en kunststromingen. Cultuur voor een breed publiek, van moderne meesters en hedendaagse kunst tot vergeten culturen, fotografie, mode en design. Bij de tentoonstellingen wordt een uitgebreid activiteitenprogramma georganiseerd.

Kunsthal Rotterdam

17 december 2016 tot 19 maart 2017

Dinsdag t/m zaterdag 10 — 17 uur

Zondag 11 — 17 uur

Museumpark

Westzeedijk 341

3015 AA Rotterdam

# Meer informatie op website Kunsthal Rotterdam

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Exhibition Archive, Jules Deelder

The Curse of Eve

The Curse of Eve

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Robert Johnson was an essentially commonplace man, with no feature to distinguish him from a million others. He was pale of face, ordinary in looks, neutral in opinions, thirty years of age, and a married man. By trade he was a gentleman’s outfitter in the New North Road, and the competition of business squeezed out of him the little character that was left. In his hope of conciliating customers he had become cringing and pliable, until working ever in the same routine from day to day he seemed to have sunk into a soulless machine rather than a man. No great question had ever stirred him. At the end of this snug century, self-contained in his own narrow circle, it seemed impossible that any of the mighty, primitive passions of mankind could ever reach him. Yet birth, and lust, and illness, and death are changeless things, and when one of these harsh facts springs out upon a man at some sudden turn of the path of life, it dashes off for the moment his mask of civilisation and gives a glimpse of the stranger and stronger face below.

Johnson’s wife was a quiet little woman, with brown hair and gentle ways. His affection for her was the one positive trait in his character. Together they would lay out the shop window every Monday morning, the spotless shirts in their green cardboard boxes below, the neckties above hung in rows over the brass rails, the cheap studs glistening from the white cards at either side, while in the background were the rows of cloth caps and the bank of boxes in which the more valuable hats were screened from the sunlight. She kept the books and sent out the bills. No one but she knew the joys and sorrows which crept into his small life. She had shared his exultations when the gentleman who was going to India had bought ten dozen shirts and an incredible number of collars, and she had been as stricken as he when, after the goods had gone, the bill was returned from the hotel address with the intimation that no such person had lodged there. For five years they had worked, building up the business, thrown together all the more closely because their marriage had been a childless one. Now, however, there were signs that a change was at hand, and that speedily. She was unable to come downstairs, and her mother, Mrs. Peyton, came over from Camberwell to nurse her and to welcome her grandchild.

Little qualms of anxiety came over Johnson as his wife’s time approached. However, after all, it was a natural process. Other men’s wives went through it unharmed, and why should not his? He was himself one of a family of fourteen, and yet his mother was alive and hearty. It was quite the exception for anything to go wrong. And yet in spite of his reasonings the remembrance of his wife’s condition was always like a sombre background to all his other thoughts.

Dr. Miles of Bridport Place, the best man in the neighbourhood, was retained five months in advance, and, as time stole on, many little packets of absurdly small white garments with frill work and ribbons began to arrive among the big consignments of male necessities. And then one evening, as Johnson was ticketing the scarfs in the shop, he heard a bustle upstairs, and Mrs. Peyton came running down to say that Lucy was bad and that she thought the doctor ought to be there without delay.

It was not Robert Johnson’s nature to hurry. He was prim and staid and liked to do things in an orderly fashion. It was a quarter of a mile from the corner of the New North Road where his shop stood to the doctor’s house in Bridport Place. There were no cabs in sight so he set off upon foot, leaving the lad to mind the shop. At Bridport Place he was told that the doctor had just gone to Harman Street to attend a man in a fit. Johnson started off for Harman Street, losing a little of his primness as he became more anxious. Two full cabs but no empty ones passed him on the way. At Harman Street he learned that the doctor had gone on to a case of measles, fortunately he had left the address—69 Dunstan Road, at the other side of the Regent’s Canal. Robert’s primness had vanished now as he thought of the women waiting at home, and he began to run as hard as he could down the Kingsland Road. Some way along he sprang into a cab which stood by the curb and drove to Dunstan Road. The doctor had just left, and Robert Johnson felt inclined to sit down upon the steps in despair.

Fortunately he had not sent the cab away, and he was soon back at Bridport Place. Dr. Miles had not returned yet, but they were expecting him every instant. Johnson waited, drumming his fingers on his knees, in a high, dim lit room, the air of which was charged with a faint, sickly smell of ether. The furniture was massive, and the books in the shelves were sombre, and a squat black clock ticked mournfully on the mantelpiece. It told him that it was half-past seven, and that he had been gone an hour and a quarter. Whatever would the women think of him! Every time that a distant door slammed he sprang from his chair in a quiver of eagerness. His ears strained to catch the deep notes of the doctor’s voice. And then, suddenly, with a gush of joy he heard a quick step outside, and the sharp click of the key in the lock. In an instant he was out in the hall, before the doctor’s foot was over the threshold.

“If you please, doctor, I’ve come for you,” he cried; “the wife was taken bad at six o’clock.”

He hardly knew what he expected the doctor to do. Something very energetic, certainly—to seize some drugs, perhaps, and rush excitedly with him through the gaslit streets. Instead of that Dr. Miles threw his umbrella into the rack, jerked off his hat with a somewhat peevish gesture, and pushed Johnson back into the room.

“Let’s see! You DID engage me, didn’t you?” he asked in no very cordial voice.

“Oh, yes, doctor, last November. Johnson the outfitter, you know, in the New North Road.”

“Yes, yes. It’s a bit overdue,” said the doctor, glancing at a list of names in a note-book with a very shiny cover. “Well, how is she?”

“I don’t——”

“Ah, of course, it’s your first. You’ll know more about it next time.”

“Mrs. Peyton said it was time you were there, sir.”

“My dear sir, there can be no very pressing hurry in a first case. We shall have an all-night affair, I fancy. You can’t get an engine to go without coals, Mr. Johnson, and I have had nothing but a light lunch.”

“We could have something cooked for you—something hot and a cup of tea.”

“Thank you, but I fancy my dinner is actually on the table. I can do no good in the earlier stages. Go home and say that I am coming, and I will be round immediately afterwards.”