Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

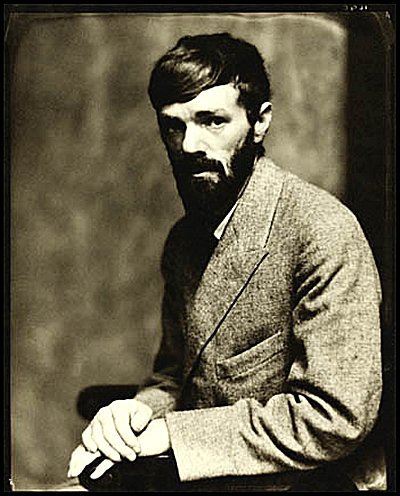

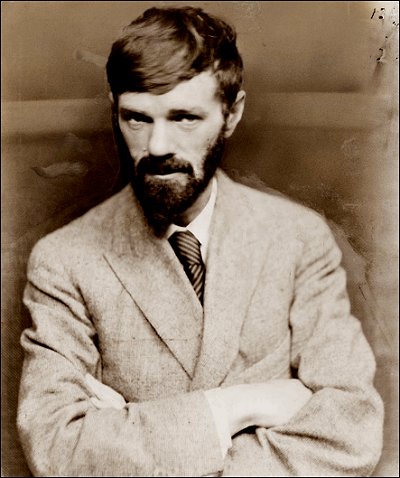

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Snake

A snake came to my water-trough

On a hot, hot day, and I in pyjamas for the heat,

To drink there.

In the deep, strange-scented shade of the great dark carob-tree

I came down the steps with my pitcher

And must wait, must stand and wait, for there he was at the trough before

me.

He reached down from a fissure in the earth-wall in the gloom

And trailed his yellow-brown slackness soft-bellied down, over the edge of

the stone trough

And rested his throat upon the stone bottom,

i o And where the water had dripped from the tap, in a small clearness,

He sipped with his straight mouth,

Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,

Silently.

Someone was before me at my water-trough,

And I, like a second comer, waiting.

He lifted his head from his drinking, as cattle do,

And looked at me vaguely, as drinking cattle do,

And flickered his two-forked tongue from his lips, and mused a moment,

And stooped and drank a little more,

Being earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth

On the day of Sicilian July, with Etna smoking.

The voice of my education said to me

He must be killed,

For in Sicily the black, black snakes are innocent, the gold are venomous.

And voices in me said, If you were a man

You would take a stick and break him now, and finish him off.

But must I confess how I liked him,

How glad I was he had come like a guest in quiet, to drink at my water-trough

And depart peaceful, pacified, and thankless,

Into the burning bowels of this earth?

Was it cowardice, that I dared not kill him?

Was it perversity, that I longed to talk to him?

Was it humility, to feel so honoured?

I felt so honoured.

And yet those voices:

If you were not afraid, you would kill him!

And truly I was afraid, I was most afraid, But even so, honoured still more

That he should seek my hospitality

From out the dark door of the secret earth.

He drank enough

And lifted his head, dreamily, as one who has drunken,

And flickered his tongue like a forked night on the air, so black,

Seeming to lick his lips,

And looked around like a god, unseeing, into the air,

And slowly turned his head,

And slowly, very slowly, as if thrice adream,

Proceeded to draw his slow length curving round

And climb again the broken bank of my wall-face.

And as he put his head into that dreadful hole,

And as he slowly drew up, snake-easing his shoulders, and entered farther,

A sort of horror, a sort of protest against his withdrawing into that horrid black hole,

Deliberately going into the blackness, and slowly drawing himself after,

Overcame me now his back was turned.

I looked round, I put down my pitcher,

I picked up a clumsy log

And threw it at the water-trough with a clatter.

I think it did not hit him,

But suddenly that part of him that was left behind convulsed in undignified haste.

Writhed like lightning, and was gone

Into the black hole, the earth-lipped fissure in the wall-front,

At which, in the intense still noon, I stared with fascination.

And immediately I regretted it.

I thought how paltry, how vulgar, what a mean act!

I despised myself and the voices of my accursed human education.

And I thought of the albatross

And I wished he would come back, my snake.

For he seemed to me again like a king,

Like a king in exile, uncrowned in the underworld,

Now due to be crowned again.

And so, I missed my chance with one of the lords

Of life.

And I have something to expiate:

A pettiness.

Taormina, 1923

D. H. Lawrence: Snake

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (6)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio,

Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

OF THE NOTES OF SERAFINO GUBBIO

CINEMATOGRAPH OPERATOR

6

All the reflexions that I made at the beginning with regard to my wretched plight, and that of all the others who are condemned like myself to be nothing more than a hand that turns a handle, have as their starting point this man, whom I met on the morning after myarrival in Rome. Certainly I have been in a position to make them, because I too have been reduced to this office of being the servant of a machine; but that came afterwards.

I say this, because this man presented to the reader at this point, after the aforesaid reflexions, might appear to him to be a grotesque invention of my fancy. But let him remember that I should perhaps never have thought of those reflexions, had they not been, partly at least, suggested to me by Simone Pau’s introducing the unfortunate creature to me; while, for that matter, the whole of this first adventure of mine is grotesque, and is so because Simone Pau himself is, and means to be, almost by profession, grotesque, as he shewed on that first evening when he chose to take me to a Casual Shelter.

I did not make any reflexion whatsoever at the time; in the first place, because I could never, even in my wildest dreams, have thought that I should be reduced to this occupation; also, because I should have been interrupted by a great hubbub on the stair leading to the dormitory, and by the tumultuous and joyful inrush of all the inmates who had already gone down to the dressing-room to recover their clothes.

What had happened?

They came upstairs again, still swathed in the white wrappers, and with the slippers on their feet.

Among them, together with the attendants and the Sisters of Charity attached to the Shelter and to the soup kitchen, were a number of gentlemen and some ladies, all well dressed and smiling, with an air of curiosity and novelty. Two of these gentlemen were carrying, one a machine, which now I know well, wrapped in a black cover, while the other had under his arm its knock-kneed tripod. They were actors and operators from a cinematograph company, and had come about a film to take a scene from real life in a Casual Shelter.

The cinematograph company which had sent these actors was the Kosmograph, in which I for the last eight months have held the post of operator; and the stage manager who was in charge of them was Nicola Polacco, or, as they all call him, Cocò Polacco, my playmate and schoolfellow at Naples in my early boyhood. I am indebted to him for my post, and to the fortunate coincidence of my happening to have spent the night with Simone Pau in that Casual Shelter.

But neither, I repeat, did it enter my mind, that morning, that I should ever come down to setting up a photographic camera on its tripod, as I saw these two gentlemen doing, nor did it occur to Cocò Polacco to suggest such an occupation to me. He, like the good fellow that he is, made no bones about recognising me, whereas I, having at once recognised him, was trying my hardest not to catch his eye in that wretched place, seeing him radiant with Parisian smartness and with the air and in the setting of an invincible leader of men, among all those actors and actresses and all those recruits of poverty, whowere beside themselves with joy in their white gowns at this unlooked-for source of profit. He shewed surprise at finding me there, but only because of the early hour, and asked me how I had known that he and his company would be coming that morning to the Shelter for a real life interior. I left him under the illusion that I had turned up there by chance, out of curiosity; I introduced Simone Pau (the man with the violin, in the confusion, had slipped away); and I remained to look on disgusted at the indecent contamination of this grim reality, the full horror of which I had tasted overnight, by the stupid fiction which Polacco had come there to stage.

My disgust, however, I perhaps feel only now. That morning, I must have felt more than anything else curiosity at being present for the first time at the production of a film. This curiosity, though, was distracted at a certain point in the proceedings by one of the actresses, who, the moment I caught sight of her, aroused in me another curiosity far more keen.

Nestoroff? Was it possible? It seemed to be she and yet it seemed not to be. That hair of a strange tawny colour, almost coppery, that style of dress, sober, almost stiff, were not hers. But the motion of her slender, exquisite body, with a touch of the feline in the sway of her hips; the head raised high, inclined a little to one side, and that sweet smile on a pair of lips as fresh as a pair of rose-leaves, whenever anyone addressed her; those eyes, unnaturally wide, open,

greenish, fixed and at the same time vacant, and cold in the shadow of their long lashes were hers, entirely hers, with that certainty all her own that everyone, whatever she might say or ask, would answer yes.

Varia Nestoroff? Was it possible? Acting for a cinematograph company?

There flashed through my mind Capri, the Russian colony, Naples, all those noisy gatherings of young artists, painters, sculptors, in strange eccentric haunts, full of sunshine and colour, and a house, a dear house in the country, near Sorrento, into which this woman had brought confusion and death.

When, after a second rehearsal of the scene for which the company had come to the Shelter, Cocò Polacco invited me to come and see him at the Kosmograph, I, still in doubt, asked him if this actress was really the Nestoroff.

“Yes, my dear fellow,” he answered with a sigh. “You know her history, perhaps.”

I nodded my head.

“Ah, but you can’t know the rest of it!” Polacco went on. “Come, come and see me at the Kosmograph; I’ll tell you the whole story. Gubbio, I don’t know what I wouldn’t pay to get that woman off my hands. But, I can tell you, it is asier…”

“Polacco! Polacco!” she called to him at that moment.

And from the haste with which Cocò Polacco obeyed her summons, I fully realised the power that she had with the firm, from which she held a contract as principal with one of the most lavish salaries.

A day or two later I went to the Kosmograph, for no reason except to learn the rest of this woman’s story, of which I knew the beginning all too well.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (6)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

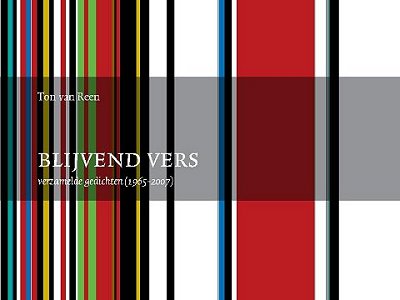

Ton van Reen

vogels

Vanavond

zijn wij

twee doodgewaande

vogels

ver van huis

in de mist geraakt

scheef

uit ons vandaan

lopen

aan elkaar geregen

tijdsberichten

naar de wezens

in de andere sferen

onze vroegere

vrienden

in een eigen

andere wereld

waaronder wij

zijn doorgevlogen

Uit: Ton van Reen, Blijvend vers, Verzamelde gedichten (1965-2007). Uitgeverij De Contrabas, 2011, ISBN 9789079432462, 144 pagina’s, paperback

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Virginia Woolf

How Should One Read a Book?

In the first place, I want to emphasize the note of interrogation at the end of my title. Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.

But to enjoy freedom, if the platitude is pardonable, we have of course to control ourselves. We must not squander our powers, helplessly and ignorantly, squirting half the house in order to water a single rose-bush; we must train them, exactly and powerfully, here on the very spot. This, it may be, is one of the first difficulties that faces us in a library. What is “the very spot?” There may well seem to be nothing but a conglomeration and huddle of confusion. Poems and novels, histories and memories, dictionaries and blue-books; books written in all languages by men and women of all tempers, races, and ages jostle each other on the shelf. And outside the donkey brays, the women gossip at the pump, the colts gallop across the fields. Where are we to begin? How are we to bring order into this multitudinous chaos and so get the deepest and widest pleasure from what we read?

It is simple enough to say that since books have classes—fiction, biography, poetry—we should separate them and take from each what it is right that each should give us. Yet few people ask from books what books can give us. Most commonly we come to books with blurred and divided minds, asking of fiction that it shall be true, of poetry that it shall be false, of biography that it shall be flattering, of history that it shall enforce our own prejudices. If we could banish all such preconceptions when we read, that would be an admirable beginning. Do not dictate to your author; try to become him. Be his fellow-worker and accomplice. If you hang back, and reserve and criticize at first, you are preventing yourself from getting the fullest possible value from what you read. But if you open your mind as widely as possible, then signs and hints of almost imperceptible fineness, from the twist and turn of the first sentences, will bring you into the presence of a human being unlike any other. Steep yourself in this, acquaint yourself with this, and soon you will find that your author is giving you, or attempting to give you, something far more definite. The thirty-chapters of a novel—if we consider how to read a novel first—are an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building: but words are more impalpable than bricks; reading is a longer and more complicated process than seeing. Perhaps the quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiment with the dangers and difficulties of words. Recall, then, some event that has left a distinct impression on you— how at the corner of the street, perhaps, you passed two people talking. A tree shook; an electric light danced; the tone of the talk was comic, but also tragic; a whole vision, an entire conception, seemed contained in that moment.

But when you attempt to reconstruct it in words, you will find that it breaks into a thousand conflicting impressions. Some must be subdued; others emphasized; in the process you will lose, probably, all grasp upon the emotion itself. Then turn from your blurred and littered pages to the opening pages of some great novelist—Defoe, Jane Austen, Hardy. Now you will be better able to appreciate their mastery. It is not merely that we are in the presence of a different person—Defoe, Jane Austen, or Thomas Hardy—but that we are living in a different world. Here, in Robinson Crusoe, we are trudging a plain high road; one thing happens after another; the fact and the order of the fact is enough. But if the open air and adventure mean everything to Defoe they mean nothing to Jane Austen. Hers is the drawing-room, and people talking, and by the many mirrors of their talk revealing their characters. And if, when we have accustomed ourselves to the drawing-room and its reflections, we turn to Hardy, we are once more spun round. The moors are round us and the stars are above our heads. The other side of the mind is now exposed—the dark side that comes uppermost in solitude, not the light side that shows in company. Our relations are not towards people, but towards Nature and destiny. Yet different as these worlds are, each is consistent with itself. The maker of each is careful to observe the laws of his own perspective, and however great a strain they may put upon us they will never confuse us, as lesser writers so frequently do, by introducing two different kinds of reality into the same book. Thus to go from one great novelist to another—from Jane Austen to Hardy, from Peacock to Trollope, from Scott to Meredith—is to be wrenched and uprooted; to be thrown this way and then that. To read a novel is a difficult and complex art. You must be capable not only of great fineness of perception, but of great boldness of imagination if you are going to make use of all that the novelist—the great artist—gives you.

But a glance at the heterogeneous company on the shelf will show you that writers are very seldom “great artists;” far more often a book makes no claim to be a work of art at all. These biographies and autobiographies, for example, lives of great men, of men long dead and forgotten, that stand cheek by jowl with the novels and poems, are we to refuse to read them because they are not “art?” Or shall we read them, but read them in a different way, with a different aim? Shall we read them in the first place to satisfy that curiosity which possesses us sometimes when in the evening we linger in front of a house where the lights are lit and the blinds not yet drawn, and each floor of the house shows us a different section of human life in being? Then we are consumed with curiosity about the lives of these people—the servants gossiping, the gentlemen dining, the girl dressing for a party, the old woman at the window with her knitting. Who are they, what are they, what are their names, their occupations, their thoughts, and adventures?

Biographies and memoirs answer such questions, light up innumerable such houses; they show us people going about their daily affairs, toiling, failing, succeeding, eating, hating, loving, until they die. And sometimes as we watch, the house fades and the iron railings vanish and we are out at sea; we are hunting, sailing, fighting; we are among savages and soldiers; we are taking part in great campaigns. Or if we like to stay here in England, in London, still the scene changes; the street narrows; the house becomes small, cramped, diamond-paned, and malodorous. We see a poet, Donne, driven from such a house because the walls were so thin that when the children cried their voices cut through them. We can follow him, through the paths that lie in the pages of books, to Twickenham; to Lady Bedford’s Park, a famous meeting-ground for nobles and poets; and then turn our steps to Wilton, the great house under the downs, and hear Sidney read the Arcadia to his sister; and ramble among the very marshes and see the very herons that figure in that famous romance; and then again travel north with that other Lady Pembroke, Anne Clifford, to her wild moors, or plunge into the city and control our merriment at the sight of Gabriel Harvey in his black velvet suit arguing about poetry with Spenser. Nothing is more fascinating than to grope and stumble in the alternate darkness and splendor of Elizabethan London. But there is no staying there. The Temples and the Swifts, the Harleys and the St Johns beckon us on; hour upon hour can be spent disentangling their quarrels and deciphering their characters; and when we tire of them we can stroll on, past a lady in black wearing diamonds, to Samuel Johnson and Goldsmith and Garrick; or cross the channel, if we like, and meet Voltaire and Diderot, Madame du Deffand; and so back to England and Twickenham—how certain places repeat themselves and certain names!—where Lady Bedford had her Park once and Pope lived later, to Walpole’s home at Strawberry Hill. But Walpole introduces us to such a swarm of new acquaintances, there are so many houses to visit and bells to ring that we may well hesitate for a moment, on the Miss Berrys’ doorstep, for example, when behold, up comes Thackeray; he is the friend of the woman whom Walpole loved; so that merely by going from friend to friend, from garden to garden, from house to house, we have passed from one end of English literature to another and wake to find ourselves here again in the present, if we can so differentiate this moment from all that have gone before. This, then, is one of the ways in which we can read these lives and letters; we can make them light up the many windows of the past; we can watch the famous dead in their familiar habits and fancy sometimes that we are very close and can surprise their secrets, and sometimes we may pull out a play or a poem that they have written and see whether it reads differently in the presence of the author. But this again rouses other questions. How far, we must ask ourselves, is a book influenced by its writer’s life—how far is it safe to let the man interpret the writer? How far shall we resist or give way to the sympathies and antipathies that the man himself rouses in us—so sensitive are words, so receptive of the character of the author? These are questions that press upon us when we read lives and letters, and we must answer them for ourselves, for nothing can be more fatal than to be guided by the preferences of others in a matter so personal.

But also we can read such books with another aim, not to throw light on literature, not to become familiar with famous people, but to refresh and exercise our own creative powers. Is there not an open window on the right hand of the bookcase? How delightful to stop reading and look out! How stimulating the scene is, in its unconsciousness, its irrelevance, its perpetual movement—the colts galloping round the field, the woman filling her pail at the well, the donkey throwing back his head and emitting his long, acrid moan. The greater part of any library is nothing but the record of such fleeting moments in the lives of men, women, and donkeys. Every literature, as it grows old, has its rubbish-heap, its record of vanished moments and forgotten lives told in faltering and feeble accents that have perished. But if you give yourself up to the delight of rubbish-reading you will be surprised, indeed you will be overcome, by the relics of human life that have been cast out to molder. It may be one letter—but what a vision it gives! It may be a few sentences—but what vistas they suggest! Sometimes a whole story will come together with such beautiful humor and pathos and completeness that it seems as if a great novelist had been at work, yet it is only an old actor, Tate Wilkinson, remembering the strange story of Captain Jones; it is only a young subaltern serving under Arthur Wellesley and falling in love with a pretty girl at Lisbon; it is only Maria Allen letting fall her sewing in the empty drawing-room and sighing how she wishes she had taken Dr Burney’s good advice and had never eloped with her Rishy. None of this has any value; it is negligible in the extreme; yet how absorbing it is now and again to go through the rubbish-heaps and find rings and scissors and broken noses buried in the huge past and try to piece them together while the colt gallops round the field, the woman fills her pail at the well, and the donkey brays.

But we tire of rubbish-reading in the long run. We tire of searching for what is needed to complete the half-truth which is all that the Wilkinsons, the Bunburys and the Maria Allens are able to offer us. They had not the artist’s power of mastering and eliminating; they could not tell the whole truth even about their own lives; they have disfigured the story that might have been so shapely. Facts are all that they can offer us, and facts are a very inferior form of fiction. Thus the desire grows upon us to have done with half-statements and approximations; to cease from searching out the minute shades of human character, to enjoy the greater abstractness, the purer truth of fiction. Thus we create the mood, intense and generalized, unaware of detail, but stressed by some regular, recurrent beat, whose natural expression is poetry; and that is the time to read poetry when we are almost able to write it.

Western wind, when wilt thou blow?

The small rain down can rain.

Christ, if my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

The impact of poetry is so hard and direct that for the moment there is no other sensation except that of the poem itself. What profound depths we visit then—how sudden and complete is our immersion! There is nothing here to catch hold of; nothing to stay us in our flight. The illusion of fiction is gradual; its effects are prepared; but who when they read these four lines stops to ask who wrote them, or conjures up the thought of Donne’s house or Sidney’s secretary; or enmeshes them in the intricacy of the past and the succession of generations? The poet is always our contemporary. Our being for the moment is centered and constricted, as in any violent shock of personal emotion. Afterwards, it is true, the sensation begins to spread in wider rings through our minds; remoter senses are reached; these begin to sound and to comment and we are aware of echoes and reflections. The intensity of poetry covers an immense range of emotion. We have only to compare the force and directness of

I shall fall like a tree, and find my grave,

Only remembering that I grieve,

with the wavering modulation of

Minutes are numbered by the fall of sands,

As by an hour glass; the span of time

Doth waste us to our graves, and we look on it;

An age of pleasure, revelled out, comes home

At last, and ends in sorrow; but the life,

Weary of riot, numbers every sand,

Wailing in sighs, until the last drop down,

So to conclude calamity in rest

or place the meditative calm of

whether we be young or old,

Our destiny, our being’s heart and home,

Is with infinitude, and only there;

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And effort evermore about to be,

beside the complete and inexhaustible loveliness of

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And nowhere did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside—

or the splendid fantasy of

And the woodland haunter

Shall not cease to saunter

When, far down some glade,

Of the great world’s burning,

One soft flame upturning

Seems to his discerning,

Crocus in the shade,

to bethink us of the varied art of the poet; his power to make us at once actors and spectators; his power to run his hand into characters as if it were a glove, and be Falstaff or Lear; his power to condense, to widen, to state, once and for ever.

“We have only to compare”—with those words the cat is out of the bag, and the true complexity of reading is admitted. The first process, to receive impressions with the utmost understanding, is only half the process of reading; it must be completed, if we are to get the whole pleasure from a book, by another. We must pass judgment upon these multitudinous impressions; we must make of these fleeting shapes one that is hard and lasting. But not directly. Wait for the dust of reading to settle; for the conflict and the questioning to die down; walk, talk, pull the dead petals from a rose, or fall asleep. Then suddenly without our willing it, for it is thus that Nature undertakes these transitions, the book will return, but differently. It will float to the top of the mind as a whole. And the book as a whole is different from the book received currently in separate phrases. Details now fit themselves into their places. We see the shape from start to finish; it is a barn, a pig-sty, or a cathedral. Now then we can compare book with book as we compare building with building. But this act of comparison means that our attitude has changed; we are no longer the friends of the writer, but his judges; and just as we cannot be too sympathetic as friends, so as judges we cannot be too severe. Are they not criminals, books that have wasted our time and sympathy; are they not the most insidious enemies of society, corrupters, defilers, the writers of false books, faked books, books that fill the air with decay and disease? Let us then be severe in our judgments; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind. There they hang in the mind the shapes of the books we have read solidified by the judgments we have passed on them—Robinson Crusoe, Emma The Return of the Native. Compare the novels with these—even the latest and least of novels has a right to be judged with the best. And so with poetry when the intoxication of rhythm has died down and the splendor of words has faded, a visionary shape will return to us and this must be compared with Lear, with Phèdre, with The Prelude; or if not with these, with whatever is the best or seems to us to be the best in its own kind. And we may be sure that the newness of new poetry and fiction is its most superficial quality and that we have only to alter slightly, not to recast, the standards by which we have judged the old.

It would be foolish, then, to pretend that the second part of reading, to judge, to compare, is as simple as the first—to open the mind wide to the fast flocking of innumerable impressions. To continue reading without the book before you, to hold one shadow-shape against another, to have read widely enough and with enough understanding to make such comparisons alive and illuminating—that is difficult; it is still more difficult to press further and to say, “Not only is the book of this sort, but it is of this value; here it fails; here it succeeds; this is bad; that is good.” To carry out this part of a reader’s duty needs such imagination, insight, and learning that it is hard to conceive any one mind sufficiently endowed; impossible for the most self-confident to find more than the seeds of such powers in himself. Would it not be wiser, then, to remit this part of reading and to allow the critics, the gowned and furred authorities of the library, to decide the question of the book’s absolute value for us? Yet how impossible! We may stress the value of sympathy; we may try to sink our own identity as we read. But we know that we cannot sympathize wholly or immerse ourselves wholly; there is always a demon in us who whispers, “I hate, I love,” and we cannot silence him. Indeed, it is precisely because we hate and we love that our relation with the poets and novelists is so intimate that we find the presence of another person intolerable. And even if the results are abhorrent and our judgments are wrong, still our taste, the nerve of sensation that sends shocks through us, is our chief illuminant; we learn through feeling; we cannot suppress our own idiosyncrasy without impoverishing it. But as time goes on perhaps we can train our taste; perhaps we can make it submit to some control. When it has fed greedily and lavishly upon books of all sorts—poetry, fiction, history, biography—and has stopped reading and looked for long spaces upon the variety, the incongruity of the living world, we shall find that it is changing a little; it is not so greedy, it is more reflective. It will begin to bring us not merely judgments on particular books, but it will tell us that there is a quality common to certain books. Listen, it will say, what shall we call this? And it will read us perhaps Lear and then perhaps the Agamemnon in order to bring out that common quality. Thus, with our taste to guide us, we shall venture beyond the particular book in search of qualities that group books together; we shall give them names and thus frame a rule that brings order into our perceptions. We shall gain a further and a rarer pleasure from that discrimination. But as a rule only lives when it is perpetually broken by contact with the books themselves—nothing is easier and more stultifying than to make rules which exists out of touch with facts, in a vacuum—now at last, in order to steady ourselves in this difficult attempt, it may be well to turn to the very rare writers who are able to enlighten us upon literature as an art. Coleridge and Dryden and Johnson, in their considered criticism, the poets and novelists themselves in their unconsidered sayings, are often surprisingly relevant; they light up and solidify the vague ideas that have been tumbling in the misty depths of our minds. But they are only able to help us if we come to them laden with questions and suggestions won honestly in the course of our own reading. They can do nothing for us if we herd ourselves under their authority and lie down like sheep in the shade of a hedge. We can only understand their ruling when it comes in conflict with our own and vanquishes it.

If this is so, if to read a book as it should be read calls for the rarest qualities of imagination, insight, and judgment, and you may perhaps conclude that literature is a very complex art and that it is unlikely that we shall be able, even after a lifetime of reading, to make any valuable contribution to its criticism. We must remain readers; we shall not put on the further glory that belongs to those rare beings who are also critics. But still we have our responsibilities as readers and even our importance. The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work. An influence is created which tells upon them even if it never finds its way into print. And that influence, if it were well instructed, vigorous and individual and sincere, might be of great value now when criticism is necessarily in abeyance; when books pass in review like the procession of animals in a shooting gallery, and the critic has only one second in which to load and aim and shoot and may well be pardoned if he mistakes rabbits for tigers, eagles for barndoor fowls, or misses altogether and wastes his shot upon some peaceful cow grazing in a further field. If behind the erratic gunfire of the press the author felt that there was another kind of criticism, the opinion of people reading for the love of reading, slowly and unprofessionally, and judging with great sympathy and yet with great severity, might this not improve the quality of his work? And if by our means books were to become stronger, richer, and more varied, that would be an end worth reaching.

Yet who reads to bring about an end, however desirable? Are there not some pursuits that we practice because they are good in themselves, and some pleasures that are final? And is not this among them? I have sometimes dreamt, at least that when the Day of judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards—their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble—the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

Virgina Woolf

(The Common Reader, Second Series 1926)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Libraries in Literature, The Art of Reading, Woolf, Virginia

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (5)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

5

Simone Pau pointed him out to me, the following morning, when we rose from our hammocks.

I shall not describe that barrack of a dormitory, foul with the breath of so many men, in the grey light of dawn, nor the exodus of the inmates, as they went downstairs, dishevelled and stupid with sleep, in their long white nightshirts, with their canvas slippers on their feet, and their tickets in their hands, to the dressing-room to recover their clothes.

There was one man among them who, amid the folds of his white wrapper, gripped tightly under his arm a violin, wrapped in a worn, dirty, faded cover of green baize, and went on his way frowning darkly, as though lost in contemplation of the hairs that overhung from his bushy, knitted eyebrows.

“Friend, friend!” Simone Pau called to him. The man came towards us, keeping his head lowered, as though bowed down by the enormous weight of his red, fleshy nose; and seemed to be saying as he advanced:

“Make way! Make way! You see what life can make of a man’s nose?”

Simone Pau went up to him; lovingly with one hand he lifted up the man’s chin; with the other he clapped him on the houlder, to give him confidence, and repeated:

“My friend!”

Then, turning again to myself:

“Serafino,” he said, “let me introduce to you a great artist. They have labelled him with a shocking nickname; but no matter; he is a great artist. Gaze upon him: there he is, with his God under his arm!

It looks like a broom: it is a violin.”

I turned to observe the effect of Simone Pau’s words on the face of the stranger. Emotionless. And Simone Pau went on:

“A violin, nothing else. And he never parts from it. The attendants here even allow him to take it to bed with him, on the understanding that he does not play it at night and disturb the other inmates. But there is no danger of that. Out with it, my friend, and shew it to this gentleman, who can feel for you.”

The man eyed me at first with misgivings; then, on a further request from Simone Pau, took from its case the old violin, a really priceless instrument, and shewed it to us, as a modest cripple might expose his stump.

Simone Pau went on, turning to me:

“You see? He lets you see it. A great concession, for which you ought to thank him! His father, many years ago, left him in possession of a printing press at Perugia, with all sorts of machines and type and a good connexion. Tell us, my riend, what you did with it, to consecrate yourself to the service of your God.”

The man stood looking at Simone Pau, as though he had not understood the request.

Simone Pau made it clearer:

“What did you do with it, with your press?”

Thereupon the man waved his hand with a gesture of contemptuous indifference.

“He neglected it,” Simone Pau explained this gesture. “He neglected it until he had brought himself to the verge of starvation. And then, with his violin under his arm, he came to Rome. He has not played for some time now, because he thinks that he cannot play any longer, after all that has happened to him. But until recently, he used to play in the wine-shops. In the wineshops one drinks; and he would play first, and drink afterwards. He played divinely; the more divinely he played, the more he drank; so that often he was obliged to place his God, his violin, in pawn. And then he would call at some printing press to find work; gradually he would put together what he needed to redeem his violin, and back he would go to play in the wine-shops. But listen to what happened to him once, and has led, you understand, to a slight alteration of his … don’t, for heaven’s sake, let us say his reason, let us say his conception of life. Put it away, my friend, put your instrument away: I know it hurts you if I tell the story while you have your violin uncovered.”

The man nodded several times in the affirmative, gravely, with his towsled head, and wrapped up his violin.

“This is what happened to him,” Simone Pau went on. “He called at a big printing office where there is a foreman who, as a lad, used to work in his press at Perugia. ‘There’s no vacancy; I’m sorry,’ he was told. And my friend was going away, crushed, when he heard himself called back. ‘Wait,’ said the foreman, ‘if you can adapt yourself to it, we might have something for you…. It isn’t the job for you; still, if you are hard up….’ My friend shrugged his shoulders and went with the foreman. He was taken into a special room, all silent; and the foreman shewed him a new machine: a pachyderm, flat, black, squat; a monstrous beast which eats lead and voids books. It is a perfected monotype, with none of the complications of rods and wheels and bands, without the noisy jigging of the fount. I tell you, a regular beast, a pachyderm, quietly chewing away at its long ribbon of perforated paper. ‘It does everything by itself,’ the foreman said to my friend. ‘You have nothing to do but feed it now and then with its cakes of lead, and keep an eye on it.’ My friend felt his breath fail and his arms sink. To be brought down to such an office as that, a man, an artist! Worse than being a stable-boy. … To keep an eye on that black beast, which did everything by itself, and required no other service of him than to have put in its mouth, from time to time, its food, those leaden cakes! But this is nothing, Serafino! Crushed, mortified, bowed down with shame and poisoned with spleen, my friend endured a week of this degrading slavery, and, as he handed the monster its leaden cakes, dreamed of his deliverance, his violin, his art; vowed and swore that he would never go back to playing in the wine-shops, where he is so strongly, so irresistibly tempted to drink, and determined to find other places more befitting the exercise of his art, the worship of his deity. Yes, my friends! No sooner had he redeemed the violin than he read in the advertisement columns of a newspaper, among the offers of employment, one from a inematograph, addressed: such and such a street and number, which required a violin and clarinet for its orchestra. At once my friend hastened to the place; presented himself, joyful, exultant, with his violin under his arm. Well; he found himself face to face with another machine, an automatic pianoforte, what is called a piano player. They said to him: ‘You with your violin have to accompany this instrument!’ Do you understand? A violin, in the hands of a man, accompany a roll of perforated paper running through the belly of this other machine! The soul, which moves and guides the hands of the man, which now passes into the touch of the bow, now trembles in the fingers that press the strings, obliged to follow the register of this automatic instrument!

My friend flew into such a towering passion that the police had to be called, and he was arrested and sentenced to a ortnight’s imprisonment for assaulting the forces of law and order.

“He came out again, as you see him.

“He drinks now, and does not play any more.”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (5)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

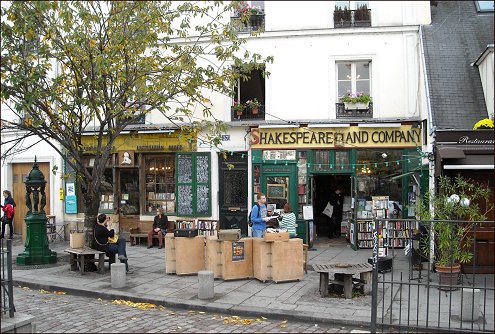

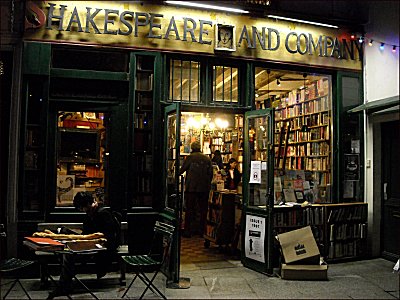

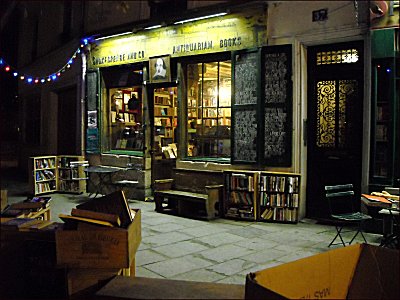

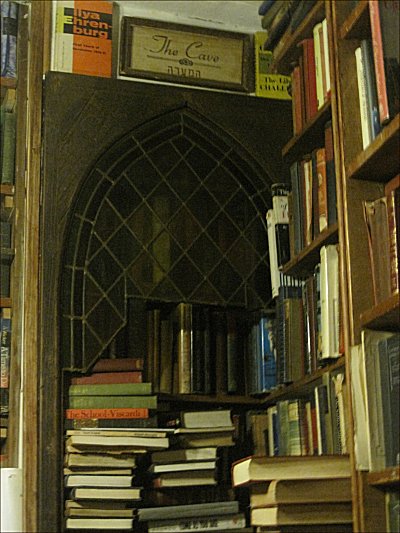

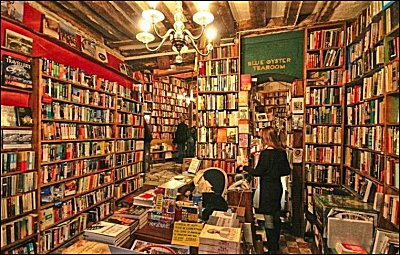

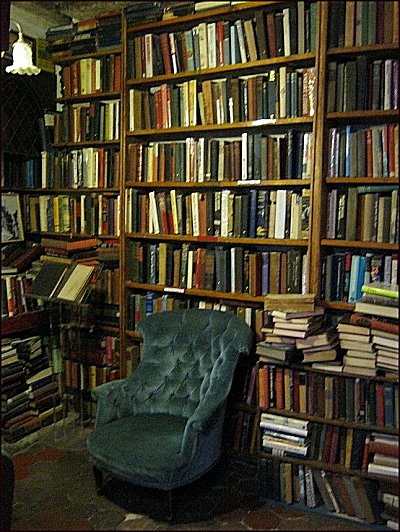

Bookshop Shakespeare and Company in Paris

Death of George Whitman

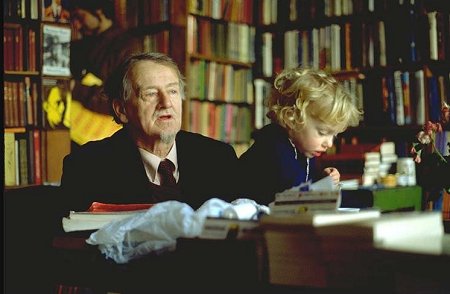

On Wednesday 14th December, 2011, George Whitman died peacefully at home in the apartment above his bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, in Paris. George suffered a stroke two months ago, but showed incredible strength and determination up to the end, continuing to read every day in the company of his daughter, Sylvia, his friends and his cat and dog. He died two days after his 98th birthday.

George Whitman was born on December 12, 1913 to mother Grace Bates and father Walter George Whitman in East Orange, New Jersey. When George was still a baby the family moved to Salem, Massachusetts. Early in his life George’s parents instilled in him a passionate and profound respect for literature. Walter was a well-respected professor of physics and the author of several books on science in the home and community. In 1925, when George was twelve years old, Walter took the whole family (except the youngest son Carl) on a year-long sabbatical to Nanking University in China. Immersed in Chinese culture and society, George and his younger sister Mary learned the language quite quickly. It was his first trip abroad, and his experiences in China made a lasting impression on him.

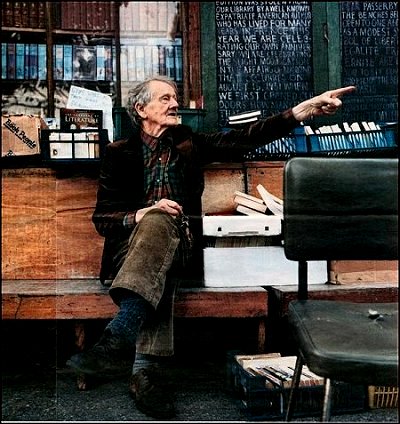

George Whitman

With the brief exception of the Nanking exchange, George lived in Salem until he graduated from high school. While he was a student he published and edited his own satirical paper called “The Reflector” and also worked as a newsboy. In 1931 George decided to enroll as an undergraduate at Boston University with a major in journalism. After his graduation in 1935 he decided to travel again. With $40 in his pocket he caught a ride to Mexico city and began a voyage that was to trace almost 5000 kilometers through Mexico and Central America, including the Honduras, Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Hawaii. During this time he became fluent in Spanish.

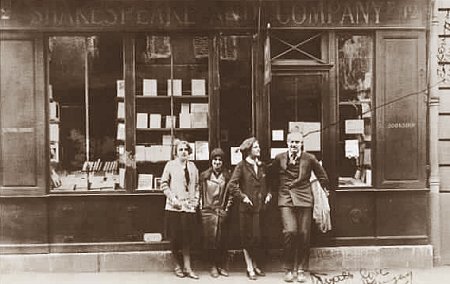

Ernest Hemingway (right)

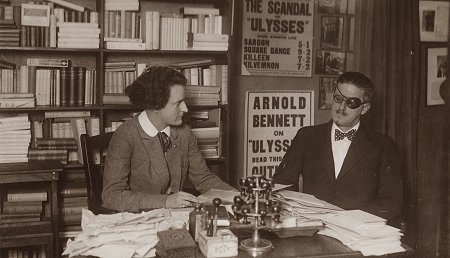

Sylvia Beach and James Joyce

George Whitman and daughter Sylvia

Sylvia Whitman

This trip was a formative experience in George’s life. Much of his traveling was done alone and on foot. He had many adventures and close calls. In an isolated part of the Yucatan he fell sick with dysentery and was forced to walk alone for three days through the swampy jungle with no food or water. Eventually he was found and nursed back to health by a tribe of Mayans. George was deeply impressed by the fact that despite hardship and extreme poverty, the people he met were invariably friendly and generous. This philosophy of “give what you can, take what you need” would become one of his founding principles.

When he arrived in Panama George ran out of money. He found a job working with the Panama Canal Company, where he stayed for several months before sailing to Hawaii and then to San Francisco in 1938, where he worked as a cable car conductor, attended classes at the University of California and enlisted in the US Army. He didn’t stay out west for long but decided to hobo his way back east, riding the rails until he arrived back in Massachussets. In 1939 he enrolled at Harvard University, where he stayed until 1941 when he was called into military service. He was trained as a Medical Warrant Officer and worked at different hospitals around Europe, helping with the wounded. Several months of his army career were spent at an isolated post in Greenland. He lived with the natives, learned to sail, and according to George, had a beautiful Eskimo girlfriend.

Returning to the United States, George managed to open and run a small bookstore in Taunton, Massachusetts while still working night shifts for the army until the war ended and he was discharged. After more travels through western Europe and France, George moved permanently to Paris in 1948 under the GI Bill. He lived in a small room in the Hotel Suez on Boulevard St. Michel in the heart of the Left Bank and enrolled at the Sorbonne, studying French civilization, philosophy, culture, and literature. Encouraged by his great friend Lawrence Lawrence Ferlinghetti, George founded his bookshop, Le Mistral, at 37 rue de la Bûcherie in 1951. The name, he says, “was in honour of the first girl I ever fell in love with.” Inspired by his encounters with the legendary bookseller Sylvia Beach, he later changed the name of his shop to Shakespeare and Company. In 1981 George’s only daughter was born at the Hôtel Dieu, directly across the Seine from the bookshop. She was respectfully named after Sylvia Beach.

For 60 years George worked tirelessly to ensure that Shakespeare and Company remains not only a venerable independent bookshop, but also a renowned Left Bank cultural institution and a home-away-from-home for many thousands of writers and visitors from around the world. In 2006 he was awarded the Officier des Arts et Lettres by the French Minister of Culture for his lifelong contribution to the arts.

On Wednesday 14th December, 2011, George Whitman died at home in the apartment above his bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, in Paris. George suffered a stroke two months before, but showed incredible strength and determination up to the end, continuing to read every day in the company of his daughter, Sylvia, his friends and his cat and dog. He died two days after his 98th birthday.

After a life entirely dedicated to books, authors and readers, George will be sorely missed by all his loved ones and by bibliophiles around the world who have read, written and stayed in his bookshop for over 60 years. Nicknamed the Don Quixote of the Latin Quarter, George will be remembered for his free spirit, his eccentricity and his generosity – all three summarised in the verses written on the walls of his open, much-visited library : “Be not inhospitable to strangers / Lest they be angels in disguise.”

George was buried at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, in the good company of other men and women of letters such as Guillaume Apollinaire, Colette, Oscar Wilde and Balzac. His bookstore continues, run by his daughter Sylvia.

Shakespeare and Company, 37 Rue Bûcherie, 75005 Paris, France

photos 1-3 jef van kempen + photos archive shakespeare & company

≡ Website Shakespeare & Company Paris

Books. The final chapter?

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Bookstores, FDM in Paris

17 maart 2012

Tilburgs literatuur- en

theaterfestival TILT

Wegens groot succes geprolongeerd: TiLT. Een festival dat bol staat van literatuur, muziek, theater en beeldende kunst. Verrassende cross-overs, spraakmakende interviews, hilarische acts en een vette band. Vorig jaar was de eerste editie stijf uitverkocht. Op zaterdag 17 maart gaat De NWE Vorst in Tilburg opnieuw op TiLT.

In de Boekenweek komen de letteren tot leven. En hoe! Het Zuidelijk Toneel opent het bal, in een verrassende combi met Fontysstudenten. Robert Vuijsje komt langs met zijn nieuwe roman Beste Vriend. AKO-literatuurprijswinnares Marente de Moor zal er zijn. Maar ook absurdist Gummbah met zijn Net niet verschenen boeken, Henk van Straten met zijn Superlul, en stadsdichteres Esther Porcelijn met vers Tilburgs vlees.

Overal in De NWE Vorst zijn optredens. Bezoekers vinden vier zalen vol proza, poëzie, beeldende kunst, muziek en theater. Er zijn columns van Hanna Bervoets (Volkskrant) en Renske de Greef (nrc-next) en liedjes van Koek & Trommel. Er is Stine Jensen met filosofie over Facebook, A.H.J. Dautzenberg met spraakmakende literatuur, een poëzieinstallatie van kunstenares Anouk van Reijen en nog veel meer. In de meeste gevallen gaat het om programma’s die speciaal voor TiLT zijn gemaakt. En dat alles wordt afgesloten met een swingende deejay en de boomende band The Kik.

Nieuw dit jaar is Kroeg op TiLT. Op vrijdag 16 maart, de avond vóór het festival, staan zes kroegen op de Korte Heuvel in het teken van de taal. Gedichten, muziek, dans, zang, verhalen, film, alles zal versmelten tot één uniek evenement. Een gratis crossoverprogramma vol Tilburgs talent, samengesteld door Studievereniging Animo van de Tilburg University.

TiLT vindt plaats in de Boekenweek, op zaterdag 17 maart, van 20.00 – 02.00 uur in theater De NWE Vorst in Tilburg. Tickets kosten € 17,50. Meer info: www.tilt.nu

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: A.H.J. Dautzenberg, Art & Literature News, Gummbah, MUSIC, Porcelijn, Esther, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg

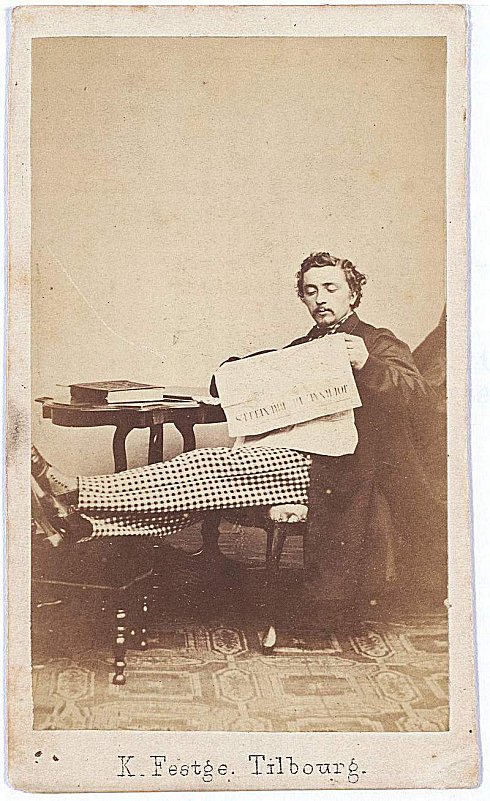

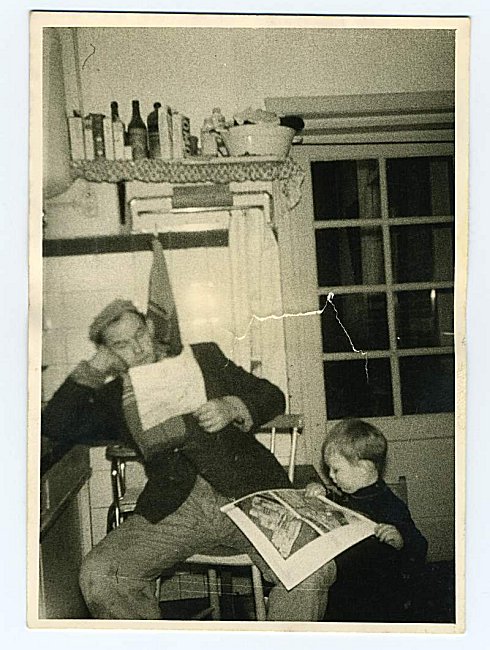

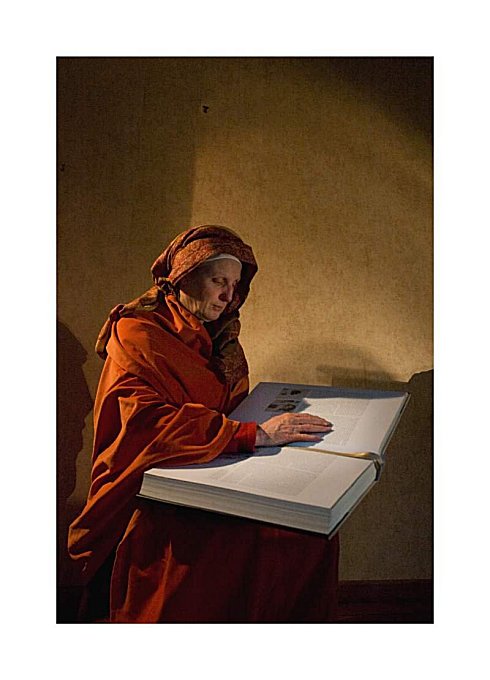

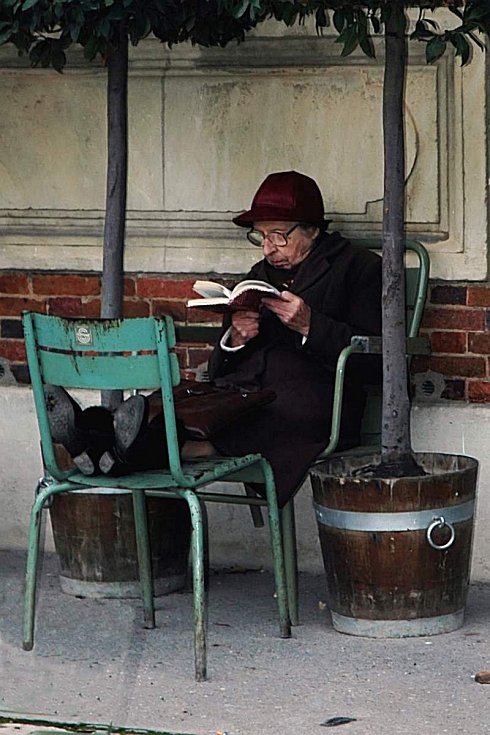

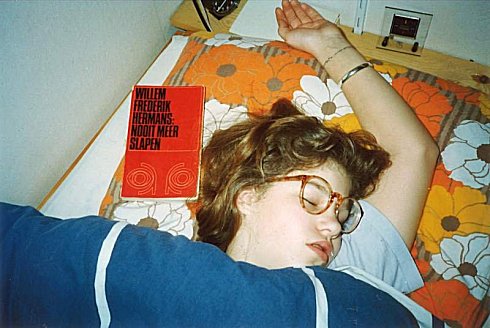

Foto-expo in de Bibliotheek Tilburg

‘Lezen altijd overal’

TILBURG – ‘Lezen altijd overal’. Onder die titel is in januari een fototentoonstelling te zien in de hoofdvestiging van de Openbare Bibliotheek Tilburg aan het Koningsplein. Lezende mensen van vroeger en nu staan hierbij centraal.

De betreffende leesfoto’s werden ingestuurd door Midden-Brabanders na een oproep van de Stichting Dr. P.J. Cools msc. Deze stichting organiseert de jaarlijks terugkerende tweedehandsboekenmarkt ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’. Van de 125 ingestuurde foto’s – voornamelijk afkomstig uit familiealbums – werden er 83 opgenomen in een boekje dat samengesteld werd door Joep Eijkens. De oudste foto dateert van rond 1865, de jongste van 2011.

De gratis toegankelijke tentoonstelling omvat overigens niet alleen alle foto’s uit het boekje maar ook een deel van de niet geselecteerde foto’s.

Lezen altijd overal. Leesfoto’s 1865 – 2011

Joep Eijkens (samenst.)

stichting Dr. P.J. Cools msc, Tilburg 2011

oplage 500 ex. / verkoopprijs € 7,50

verkrijgbaar bij boekhandel Livius Tilburg

Expositie Openbare Bibliotheek Tilburg in januari 2012

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: BOOKS. The final chapter?, Joep Eijkens Photos

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (4)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

4

Coming to the end of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, we crossed the bridge. I remember that I gazed almost with a religious awe at the dark rounded mass of Castel Sant’ Angelo, high and solemn under the twinkling of the stars. The great works of human architecture, by night, and the heavenly constellations seem to have a mutual understanding. In the humid chill of that immense nocturnal background, I felt this awe start up, flicker as in a succession of spasms, which were caused in me perhaps by the serpentine reflexions of the lights on the other bridges and on the banks, in the black mysterious water of the river. But Simone Pau tore me from this attitude of admiration, turning first in the direction of Saint Peter’s, then dodging aside along the Vicolo del Villano. Uncertain of the way, uncertain of everything, in the empty horror of the deserted streets, full of strange phantoms quivering from the rusty reflectors of the infrequent lamps, at every breath of air, on the walls of the old houses, I thought with terror and disgust of the people that were lying comfortably asleep in those houses and had no idea how their homes appeared from outside to such as wandered homeless through the night, without there being a single house anywhere which they might enter. Now and again, Simone Pau shook his head and tapped his chest

with two fingers. Oh, yes! The mountain was he, and the tree, and the sea; but the hotel, where was it? There, in Borgo Pio? Yes, close at hand, in the Vicolo del Falco. I raised my eyes; I saw on the right hand side of that alley a grim building, with a lantern hung out above the door: a big lantern, in which the flame of the gas-jet yawned through the dirty glass. I stopped in front of this door which was standing ajar, and read over the arch:

CASUAL SHELTER

“Do you sleep here?”

“Yes, and feed too. Lovely bowls of soup. In the best of company. Come in: this is my home.”

Indeed the old porter and two other men of the night staff of the Shelter, huddled and crouching together round a copper brazier, welcomed him as a regular guest, greeting him with gestures and in words from their glass cage in the echoing orridor:

“Good evening, Signor Professore.”

Simone Pau warned me, darkly, with great solemnity, that I must not be disappointed, for I should not be able to sleep in this hotel for more than six nights in succession. He explained to me that after every sixth night I should have to spend at least one outside, in the open, in order to start a fresh series.

I, sleep there?

In the presence of those three watchmen, I listened to his explanation with a melancholy smile, which, however, hovered ently over my lips, as though to preserve the buoyancy of my spirits and to keep them from sinking into the shame of this abyss.

Albeit in a wretched plight, with but a few lire in my pocket, I was well dressed, with gloves on my hands, spats on my ankles. I wanted to take the adventure, with this smile, as a whimsical caprice on the part of my strange friend. But Simone Pau was annoyed:

“You don’t take me seriously?”

“No, my dear fellow, indeed I don’t take you seriously.”

“You are right,” said Simone Pau, “serious, do you know who is really serious? The quack doctor with a black coat and no collar, with a big black beard and spectacles, who sends the medium to sleep in the market-place. I am not quite as serious as that yet. You may laugh, friend Serafino.”

And he went on to explain to me that it was all free of charge there. In winter, on the hammocks, a pair of clean sheets, solid and fresh as the sails of a ship, and two thick woollen blankets; in summer, the sheets alone, and a counterpane for anyone who wanted it; also a wrapper and a pair of canvas slippers, washable.

“Remember that, washable!”

“And why?”

“Let me explain. With these slippers and wrapper they give you a ticket; you go into that dressing-room there–through that door on the right–undress, and hand in your clothes, including your shoes, to be disinfected, which is done in the ovens over there. Then, come over here, look…. Do you see this lovely pond?”

I lowered my eyes and looked.

A pond? It was a chasm, mouldy, narrow and deep, a sort of den to herd swine in, carved out of the living rock, to which one went down by five or six steps, and over which there hung a pungent odour of suds.

A tin pipe, pierced with holes that were all yellow with rust, ran above it along the middle from end to end.

“Well?”

“You undress over there; hand in your clothes….”

“… shoes included….”

“… shoes included, to be disinfected, and step down here naked.”

“Naked?”

“Naked, in company with six or seven other nudes. One of our dear friends in the cage there turns on the tap, and you, standing under the pipe, zifff…, you get, free for nothing, a most beautiful shower. Then you dry yourself sumptuously with your wrapper, put on your canvas slippers, and steal quietly out in procession with the other draped figures up the stairs; there they are; up there is the dormitory, and so goodnight.”

“Is it compulsory?”

“What? The shower? Ah, because you are wearing gloves and spats, friend Serafino? But you can take them off without shame. Everyone here strips himself of his shame, and offers himself naked to the baptism of this pond! Haven’t you the courage to descend to these nudities?”

There was no need. The shower is obligatory only for unclean mendicants. Simone Pau had never taken it.

In this place he is, really, a schoolmaster. Attached to the shelter there are a soup kitchen and a refuge for homeless children of either sex, beggars’ children, prisoners’ children, children of every form of sin and shame. They are under the care of certain Sisters of Charity, who have managed to set up a little school for them as well. Simone Pau, albeit by profession a bitter enemy of humanity and of every form of teaching, gives lessons with the greatest pleasure to these

children, for two hours daily, in the early morning, and the children are extremely grateful to him. He is given, in return, his board and lodging: that is to say a little room, all to himself, clean and neat, and a special service of meals, shared with four other teachers, who are a poor old pensioner of the Papal Government and three spinster schoolmistresses, friends of the Sisters and taken in here by them. But Simone Pau dispenses with the special meals, since at midday he is never in the Shelter, and it is only in the evenings, when it suits his convenience, that he takes a bowlful or two of soup from the common kitchen; he keeps the little room, but he never uses it, because he goes and sleeps in the dormitory of the Night Shelter, for the sake of the company to be found there, which he has grown to relish, of queer, vagrant types. Apart from these two hours devoted to teaching, he spends all his time in the libraries and the ‘caffè’; every now and then, he publishes in some philosophic review an essay which amazes everyone by the bizarre novelty of the views expressed in it, the strangeness of the arguments and the abundance of learning displayed; and he flourishes again for a while.

At the time, I repeat, I was not aware of all this. I supposed, and perhaps it was partly true, that he had brought me there for the pleasure of bewildering me; and since there is no better way of disconcerting a person who is seeking to bewilder one with extravagant paradoxes or with the strangest, most fantastic suggestions than to pretend to accept those paradoxes as though they were the most obvious truisms, and his suggestions as entirely natural and opportune; so I behaved that evening, to disconcert my friend Simone Pau. He, realising my intention, looked me in the eyes and, seeing them to be completely impassive, exclaimed with a smile: “What an idiot you are!”

He offered me his room; I thought at first that he was joking; but when he assured me that he really had a room there to himself, I would not accept it and went with him to the dormitory of the Shelter. I am not sorry, since, for the discomfort and repulsion that I felt in that odious place, I had two compensations:

First; that of finding the post which I now hold, or rather the opportunity of going as an operator to the great cinematograph company, the Kosmograph;

Secondly; that of meeting the man who has remained for me ever since the symbol of the wretched fate to which continuous progress condemns the human race.

First of all, the man.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (4)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

to be continued

More in: -Shoot!

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (3)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio,

Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

OF THE NOTES OF SERAFINO GUBBIO CINEMATOGRAPH OPERATOR

3

I cannot get out of my mind the man I met a year ago, on the night of

my arrival in Rome.

It was in November, a bitterly cold night. I was wandering in search

of a modest lodging, not so much for myself, accustomed to spend my

nights in the open, on friendly terms with the bats and the stars, as

for my portmanteau, which was my sole worldly possession, left behind

in the railway cloakroom, when I happened to run into one of my

friends from Sassari, of whom I had long lost sight: Simone Pau, a man

of singular originality and freedom from prejudice. Hearing of my

hapless plight, he proposed that I should come and sleep that night in

his hotel. I accepted the invitation, and we set off on foot through

the almost deserted streets. On our way, I told him of my many

misadventures and of the frail hopes that had brought me to Rome.

Every now and then Simone Pau raised his hat-less head, on which the

long, sleek, grey hair was parted down the middle in flowing locks,

but zigzag, the parting being made with his fingers, for want of a

comb. These locks, drawn back behind his ears on either side, gave him

a curious, scanty, irregular mane. He expelled a large mouthful of

smoke, and stood for a while listening to me, with his huge swollen

lips held apart, like those of an ancient comic mask. His crafty,

mouselike eyes, sharp as needles, seemed to dart to and fro, as though

trapped in his big, rugged, massive face, the face of a savage and

unsophisticated peasant. I supposed him to have adopted this attitude,

with his mouth open, to laugh at me, at my misfortunes and hopes. But,

at a certain point in my recital, I saw him stop in the middle of the

street lugubriously lighted by its gas lamps, and heard him say aloud

in the silence of the night:

“Excuse me, but what do I know about the mountain, the tree, the sea?

The mountain is a mountain because I say: ‘That is a mountain.’ In

other words: ‘_I am the mountain_.’ What are we? We are whatever, at

any given moment, occupies our attention. I am the mountain, I am the

tree, I am the sea. I am also the star, which knows not its own

existence!”

I remained speechless. But not for long. I too have, inextricably

rooted in the very depths of my being, the same malady as my friend.

A malady which, to my mind, proves in the clearest manner that

everything that happens happens probably because the earth was made

not so much for mankind as for the animals. Because animals have in

themselves by nature only so much as suffices them and is necessary

for them to live in the conditions to which they were, each after its

own kind, ordained; whereas men have in them a superfluity which

constantly and vainly torments them, never making them satisfied with

any conditions, and always leaving them uncertain of their destiny. An

inexplicable superfluity, which, to afford itself an outlet, creates

in nature an artificial world, a world that has a meaning and value

for them alone, and yet one with which they themselves cannot ever be

content, so that without pause they keep on frantically arranging and

rearranging it, like a thing which, having been fashioned by

themselves from a need to extend and relieve an activity of which they

can see neither the end nor the reason, increases and complicates ever

more and more their torments, carrying them farther from the simple

conditions laid down by nature for life on this earth, conditions to

which only dumb animals know how to remain faithful and obedient.

My friend Simone Pau is convinced in good faith that he is worth a

great deal more than a dumb animal, because the animal does not know

and is content always to repeat the same action.

I too am convinced that he is of far greater value than an animal, but

not for those reasons. Of what benefit is it to a man not to be

content with always repeating the same action? Why, those actions that

are fundamental and indispensable to life, he too is obliged to

perform and to repeat, day after day, like the animals, if he does not

wish to die. All the rest, arranged and rearranged continually and

frantically, can hardly fail to reveal themselves sooner or later as

illusions or vanities, being as they are the fruit of that

superfluity, of which we do not see on this earth either the end or

the reason. And where did my friend Simone Pau learn that the animal

does not know? It knows what is necessary to itself, and does not

bother about the rest, because the animal has not in its nature any

superfluity. Man, who has a superfluity, and simply because he has it,

torments himself with certain problems, destined on earth to remain

insoluble. And this is where his superiority lies! Perhaps this

torment is a sign and proof (riot, let us hope, an earnest also) of

another life beyond this earth; but, things being as they are upon

earth, I feel that I am in the right when I say that it was made more

for the animals than for men.

I do not wish to be misunderstood. What I mean is, that on this earth

man is destined to fare ill, because he has in him more than is

sufficient for him to fare well, that is to say in peace and

contentment. And that it is indeed an excess, _for life on earth_,

this element which man has within him (and which makes him a man and

not a beast), is proved by the fact that it–this excess–never

succeeds in finding rest in anything, nor in deriving contentment from

anything here below, so that it seeks and demands elsewhere, beyond

the life on earth, the reason and recompense for its torment. So much

the worse, then, does man fare, the more he seeks to employ, upon the

earth itself, in frantic constructions and complications, his own

superfluity.

This I know, I who turn a handle.

As for my friend Simone Pau, the beauty of it is this: that he

believes that he has set himself free from all superfluity, reducing

all his wants to a minimum, depriving himself of every comfort and

living the naked life of a snail. And he does not see that, on the

contrary, he, by reducing himself thus, has immersed himself

altogether in the superfluity and lives now by nothing else.

That evening, having just come to Rome, I was not yet aware of this. I

knew him, I repeat, to be a man of singular originality and freedom

from prejudice, but I could never have imagined that his originality

and his freedom from prejudice would reach the point that I am about

to relate.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (3)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Ton van Reen

de bomen

De bomen

hebben zich opgehangen

in de lucht

ze hebben de sferen

doorworteld

de bovenaardse lagen

afgegraasd

ze zijn als wilde paarden

op hol geslagen

de manen van hun

veel te grote wezens

achter zich sleurend

als bagage

alsof ze mensen waren

die met grote ijver

verjaagd zijn

van hun beperkte meters aarde

om het bezit van de vruchten

Uit: Ton van Reen, Blijvend vers, Verzamelde gedichten (1965-2007). Uitgeverij De Contrabas, 2011, ISBN 9789079432462, 144 pagina’s, paperback

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

After The Opera

Down the stone stairs

Girls with their large eyes wide with tragedy

Lift looks of shocked and momentous emotion up at me.

And I smile.

Ladies

Stepping like birds with their bright and pointed feet

Peer anxiously forth, as if for a boat to carry them out of the wreckage,

And among the wreck of the theatre crowd

I stand and smile.

They take tragedy so becomingly.

Which pleases me.

But when I meet the weary eyes

The reddened aching eyes of the bar-man with thin arms,

I am glad to go back to where I came from.

D. H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature