Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Eddy van Vliet

(1942-2002)

Dood

Dood. Heb geen angst. Talm niet

voor mijn deur. Kom binnen.

Lees mijn boeken. In negen van de tien

kom je voor. Je bent geen onbekende.

Hou mij niet voor de gek met kwalen

waarvan niemand de namen durft te noemen.

Leg mij niet in een bed tussen kwijlende

kinderen die van ouderdom niet weten wat ze zeggen.

Klop mij geen geld uit de zak

voor nutteloze uren in chique klinieken.

Veeg je voeten en wees welkom.

Eddy van Vliet poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V

Books. The last chapter?

Bookstores :

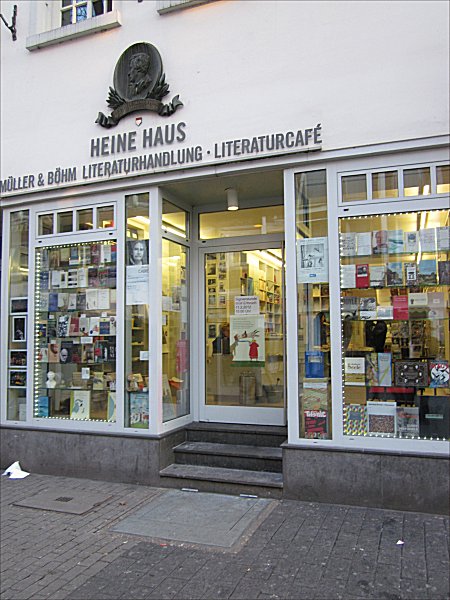

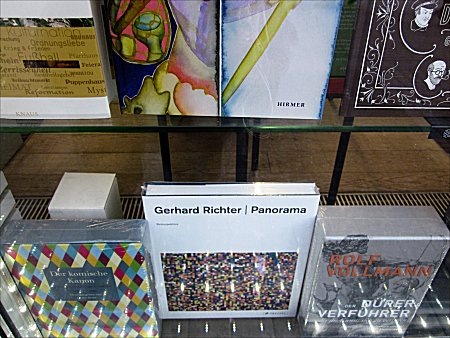

Müller & Böhm – Literaturhandlung im Heine Haus

Bolkerstraße 53, Düsseldorf

photos: kemp=mag 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Bookstores

Avro Close Up

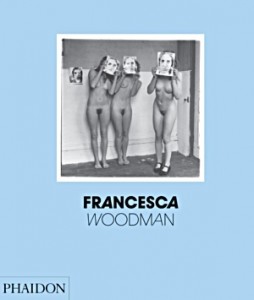

Francesca Woodman – fotografe

Documentaire

– Dinsdag 10 april 2012 – 23:00 – 00:00

– Zondag 15 april 2012 – 17:05 – 18:05

Nadat de zeer talentvolle Amerikaanse fotografe Sarah Woodman op 22-jarige leeftijd zelfmoord pleegde, kostte het haar ouders en broer – eveneens kunstenaars – jaren om in het reine te komen met haar dood. Ondertussen vergaarde Woodman postuum roem met haar mysterieuze zwart-wit foto’s van naakte vrouwen in verlaten interieurs, waarop zij zelf vaak prominent figureerde.

Nadat de zeer talentvolle Amerikaanse fotografe Sarah Woodman op 22-jarige leeftijd zelfmoord pleegde, kostte het haar ouders en broer – eveneens kunstenaars – jaren om in het reine te komen met haar dood. Ondertussen vergaarde Woodman postuum roem met haar mysterieuze zwart-wit foto’s van naakte vrouwen in verlaten interieurs, waarop zij zelf vaak prominent figureerde.

Francesca Woodman (1958-1981) groeide op in een gezin van zeer gedreven kunstenaars. Haar moeder, Betty Woodman, was ceramiste en haar vader, George Woodman, schilderde. Francesca bracht de zomers van haar jeugd met haar ouders en broer door in Florence, waar ze als klein meisje in musea ronddwaalde en haar schetsboeken vulde met tekeningen van vrouwen in formele kleding.

De ouders van Francesca leefden volgens het principe ‘kunst is keihard werken’ maar desondanks stonden ze verbaasd over de ambitie van hun opgroeiende dochter die haar ouders in doelgerichtheid en vastberadenheid overtrof. Als zeventienjarige werd Woodman verliefd op de fotografie en al snel ontwikkelde ze een complexe, volwassen stijl waarbij ze als haar eigen model figureerde in mysterieuze taferelen die zich afspeelden in verlaten en vervallen interieurs. In de jaren die volgden verhuisde ze naar New York waar ze in de kunstwereld als veelbelovend werd gezien, maar een doorbraak liet op zich wachten. Ondertussen worstelde Francesca met depressies, een strijd die haar zo zwaar viel dat ze in 1981 een einde maakte aan haar leven.

De documentaire ‘Francesca Woodman – Fotografe’ schetst een beeld van het uitzonderlijke talent van Francesca Woodman, van wie het werk tegenwoordig in musea hangt. De film laat ook zien hoe haar ouders en haar broer het vroegtijdig overlijden van hun dochter en zus verwerkt hebben en welke rol hun eigen kunst gespeeld heeft in een lang en pijnlijk proces.

Regie: C. Scott Willis

Een productie van C. Scott Films

Close Up: Francesca Woodman – Fotografe:

10 april 2012, 23.00 uur, Ned. 2.

Herhaling: Zondag 15 april , 17.05 uur, Ned. 2.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Francesca Woodman, Francesca Woodman

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (10)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

4

The experience of seeing men sink lower than the beasts must frequently have occurred to Varia Nestoroff.

And yet she has not killed them. A huntress, as you are a hunter. The snipe, you have killed. She has never killed anyone. One only, for her sake, has killed himself, by his own hand: Giorgio Mirelli; but not for her sake alone.

The beast, moreover, which does harm from a necessity of its nature, is not, so far as we know, unhappy.

The Nestoroff, as we have abundant grounds for supposing, is most unhappy. She does not enjoy her own wickedness, for all that it is carried out with such cold-blooded calculation.

If I were to say openly what I think of her to my fellow-operators, to the actors and actresses of the firm, all of them would at once suspect that I too had fallen in love with the Nestoroff.

I ignore this suspicion.

The Nestoroff feels for me, like all her fellow-artists, an almost instinctive aversion. I do not reciprocate it in any way because I do not spend my time with her, except when I am in the service of my machine, and then, as I turn the handle, I am what I am supposed to be, that is to say perfectly ‘impassive’. I am unable either to hate or to love the Nestoroff, as I am unable either to hate or to love anyone. I am ‘a hand that turns the handle’. When, finally, I am

restored to myself, that is to say when for me the torture of being only a hand is ended, and I can regain possession of the rest of my body, and marvel that I have still a head on my shoulders, and abandon myself once more to that wretched ‘superfluity’ which exists in me nevertheless and of which for almost the whole day my profession condemns me to be deprived; then… ah, then the affections, the memories that come to life in me are certainly not such as can persuade me to love this woman. I was the friend of Giorgio Mirelli, and among the most cherished memories of my life is that of the dear house in the country by Sorrento, where Granny Rosa and poor Duccella still live and mourn.

I study. I go on studying, because that is perhaps my ruling passion: it nourished in times of poverty and sustained my dreams, and it is the sole comfort that I have left, now that they have ended so miserably.

I study this woman, then, without passion but intently, who, albeit she may seem to understand what she is doing and why she does it, yet has not in herself any of that quiet “systematisation” of concepts, affections, rights and duties, opinions and habits, which I abominate in other people.

She knows nothing for certain, except the harm that she can do to others, and she does it, I repeat, with cold-blooded calculation.

This, in the opinion of other people, of all the “systematised,” debars her from any excuse. But I believe that she cannot offer any excuse, herself, for the harm which nevertheless she knows herself to have done.

She has something in her, this woman, which the others do not succeed in understanding, because even she herself does not clearly understand it. One guesses it, however, from the violent expressions which she assumes, involuntarily, unconsciously, in the parts that are assigned to her.

She alone takes them seriously, and all the more so the more illogical and extravagant they are, grotesquely heroic and contradictory. And there is no way of keeping her in check, of making her moderate the violence of those expressions. She alone ruins more films than all the other actors in the four companies put together. For one thing, she always moves out of the picture; when by any chance she does not move out, her action is so disordered, her face so strangely altered and disguised, that in the rehearsal theatre almost all the scenes in which she has taken part turn out useless and have to be done again.

Any other actress, who had not enjoyed and did not enjoy, as she does, the favour of the warm-hearted Commendator Borgalli, would long since have been given notice to leave.

Instead of which, “Dear, dear, dear…” exclaims the warm-hearted Commendatore, without the least annoyance, when he sees projected on the screen in the rehearsal theatre those demoniacal pictures, “dear, dear, dear… oh, come … no… is it possible? Oh, Lord, how horrible … cut it out, cut it out….”

And he finds fault with Polacco, and with all the producers in general, who keep the _scenarios_ to themselves, confining themselves to suggesting bit by bit to the actors the action to be performed in each separate scene, often disjointedly, because not all the scenes can be taken in order, one after another, in a studio. It often happens that the actors do not even know what part they are supposed to be taking in the play as a whole, and one hears some actor ask in the middle:

“I say, Polacco, am I the husband or the lover?”

In vain does Polacco protest that he has carefully explained the whole part to the Nestoroff. Commendator Borgalli knows that the fault does not lie with Polacco; so much so, that he has given him another leading lady, the Sgrelli, in order not to waste all the films that are allotted to his company. But the Nestoroff protests on her own account, if Polacco makes use of the Sgrelli alone, or of the Sgrelli more than of herself, the true leading lady of the company. Her

ill-wishers say that she does this to ruin Polacco, and Polacco himself believes it and goes about saying so. It is untrue: the only thing ruined, here, is film; and the Nestoroff is genuinely in despair at what she has done; I repeat, involuntarily and unconsciously. She herself remains speechless and almost terror-stricken at her own image on the screen, so altered and disordered. She sees there some one who is herself but whom she does not know. She would like not to recognise herself in this person, but at least to know her.

Possibly for years and years, through all the mysterious adventures of her life, she has gone in quest of this demon which exists in her and always escapes her, to arrest it, to ask it what it wants, why it is suffering, what she ought to do to soothe it, to placate it, to give it peace.

No one, whose eyes are not clouded by a passionate antipathy, and who has seen her come out of the rehearsal theatre after the presentation of those pictures of herself, can retain any doubt as to that. She is really tragic: terrified and enthralled, with that sombre stupor in her eyes which we observe in the eyes of the dying, and can barely restrain the convulsive tremor of her entire person.

I know the answer I should receive, were I to point this out to anyone:

“But it is rage! She is quivering with rage!”

It is rage, yes; but not the sort of rage that they all suppose, namely at a film that has gone wrong. A cold rage, colder than a blade of steel, is indeed this woman’s weapon against all her enemies. Now Cocò Polacco is not an enemy in her eyes. If he were, she would not tremble like that: with the utmost coldness she would avenge herself on him.

Enemies, to her, all the men become to whom she attaches herself, in order that they may help her to arrest the secret thing in her that escapes her: she herself, yes, but a thing that lives and suffers, so to speak, ‘outside herself’.

Well, no one has ever taken any notice of this thing, which to her is more pressing than anything else; everyone, rather, remains dazzled by her exquisite form, and does not wish to possess or to know anything else of her. And then she punishes them with a cold rage, just where their desires prick them; and first of all she exasperates those desires with the most perfidious art, that her revenge may be all the greater. She avenges herself by flinging her body, suddenly and coldly, at those whom they least expected to see thus favoured: like that, so as to shew them in what contempt she holds the thing that they prize most of all in her.

I do not believe that there can be any other explanation of certain sudden changes in her amorous relations, which appear to everyone, at first sight, inexplicable, because no one can deny that she has done harm to herself by them.

Except that the others, thinking it over and considering, on the one hand the nature of the men with whom she had consorted previously, and on the other that of the men at whom she has suddenly flung herself, say that this is due to the fact that with the former sort she could not remain, ‘could not breathe’; whereas to the latter she felt herself attracted by a “gutter” affinity; and this sudden and unexpected flinging of herself they explain as the sudden spring of a person who, after a long suffocation, seeks to obtain at last, ‘wherever he can’, a mouthful of air.

And if it should be just the opposite? If ‘in order to breathe’, to secure that help of which I have already spoken, she had attached herself to the former sort, and instead of having the ‘breathing-space’, the help for which she hoped, had found no breathing-space and no help from them, but rather an anger and disgust all the stronger because increased and embittered by disappointment, and also by a certain contempt which a person feels for the needs of another’s soul who sees and cares for nothing but his own SOUL, like that, in capital letters? No one knows; but of these “gutter” refinements those may well be capable who mostly highly esteem themselves, and are deemed ‘superior’ by their fellows. And then…then, better the gutter which offers itself as such, which, if it makes you sad, does not delude you; and which may have, as often it does have, a good side to it, and, now and then, certain traces of innocence, which cheer and refresh you all the more, the less you expected to find them there.

The fact remains that, for more than a year, the Nestoroff has been living with the Sicilian actor Carlo Ferro, who also is engaged by the Kosmograph: she is dominated by him and passionately in love with him. She knows what she may expect from such a man, and asks for nothing more. But it seems that she obtains far more from him than the others are capable of imagining.

This explains why, for some time back, I have set myself to study, with keen interest, Carlo Ferro also.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (10)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

(to be continued)

More in: -Shoot!

Düsseldorf, Rundgang 2012

February 2012

The Rundgang of the Düsseldorf Kunstakademie is visited by people of all ages. One of the explanations for its success may be that much of the art on display is fresh, direct and not yet ‘polluted’ by the intellectual and historical art considerations/layers that make art interesting to the art professional but also make it less accessible for the occasional exhibition visitor. A lack of high quality is compensated by a surplus of enthusiasm. We will show you the last batch of pictures with mostly paintings.

Kunstakademie Düsseldorf – Rundgang 2012 – Teil 4

Photos Anton K. & Monica Richter – fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Galerie Deutschland

130 kilometer per uur is leuker dan cultuur.

(Henk & Ingrid)

(http://www.henkeningrid.org/ ) ( de wereld volgens Henk & Ingrid)

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, The talk of the town

![]()

Nederlandse fototentoonstelling naar New York

The Wonder of Woman

22 juni t/m 1 juli 2012

Dat de Nederlandse fotografie in het buitenland bijzonder populair is, ondervond Aloys Ginjaar toen hij op het New York Photo Festival 2011 een tentoonstelling organiseerde. Enkele duizenden bezochten Dutch Delight en de reacties waren zeer enthousiast. Directeur Sam Barzilay: “It was great having Dutch Delight as part of the New York Photo Festival and we look forward to many more collaborations in the future!”

Ginjaar keert deze zomer terug naar New York met The Wonder of Woman, een Hommage aan de Vrouw met 60 foto’s van 26 Nederlandse fotografen. De tentoonstelling maakt van 22 juni t/m 1 juli 2012 deel uit van het nieuwe internationale fotofestival Photoville, in het Brooklyn Bridge Park. De opening zal worden verricht door een vertegenwoordiger van het Nederlands Consulaat in New York.

Aan The Wonder of Woman doen mee: Jenny Boot – Rinze van Brug – Gon Buurman – Frank van Delft – Martin Dijkstra – Tara Fallaux – Aloys Ginjaar – Carli Hermès – Barend Houtsmuller – Lilith -– Susanne Middelberg – Lenny Moeskops/Diederick Ingel –Mathilde µP – Cornelia Nauta – Roger Neve – Lieve Prins – Annelies Rigter – Suzan van de Roemer – Maartje Roos – Govert de Roos – Nancy Schoenmakers – Speer – Paul Tolenaar – Astrid Verhoef – Bianca van der Werf – Shakiro Werleman

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery

Ton van Reen

EEN NOG SCHONERE SCHIJN VAN WITHEID

Een winterverhaal

3

Vanachter het raam keken grootmoeder en ik toe hoe de gebeurtenis zich ging ontknopen. Ik verwachtte dat moeder aan de witte zeilen zou opstijgen en misschien zelfs tot boven de kersenbomen zou worden geblazen, zo wild gingen de lakens tekeer in de wind. En misschien zou ze wel over het dak van het kippenhok van buurman Hermans vliegen, en dan zou zijn zoon die een beetje gek was naar haar zwaaien. En misschien vloog ze wel over de drooghokken van de steenfabriek, waarin de uit leem gevormde stenen stonden te bevriezen in plaats van te drogen zodat de arbeiders die later weer allemaal weg moesten gooien. En misschien …, stel je toch voor dat ze met al haar lakens aan de bliksemafleider aan de top van de schoorsteen van de steenfabriek zou blijven hangen! Adembenemend, maar het zou kunnen! Het zou kunnen!!! Met moeder wist je het immers nooit. Een voor een werden de lakens uit haar handen gerukt en zeilden naar de boomgaard, alsof ze wilden ontkomen aan de zoveelste wasbeurt die ze nog doorzichtiger zou maken. Ze waren oud. Ze waren al van grootmoeder geweest. Twee generaties kinderen hadden ertussen geslapen.

Moeder won. Met de hark trok ze de lakens uit de takken, plukte ten slotte het laken van mijn zusje uit de kersenboom en klopte het af met een hardheid die op afstraffen leek. Triomfantelijk kwam ze naar binnen met het witrozige laken dat het kleinste was, maar het dapperst was geweest. Dat had je altijd: ik was ook het kleinst, en daarom moest ik altijd het hardst vechten tegen mijn oudere broers, die dachten dat ik een hamster of een hond was die je af en toe gewoon stiekem kon meppen als je een pestbui had.

Moeder zette de stijve lakens rechtop tegen de muur achter de kachel, waarna ze op een vreemde manier, vol schuldgevoel, in elkaar begonnen te zakken, ontmoedigd door de wetenschap dat ze opnieuw zouden worden gekookt en gestoomd tot ze weer kraakhelder zouden zijn en weer aan de wasdraad buiten zouden worden uitgehangen, hun uiterste witte witheid tonend, zodat de hele straat kon zien dat wij toch een proper gezin vormden ondanks het feit dat we drie jongens hadden die elke week op school tijdens de godsdienstles van de pastoor te horen kregen dat jongens nooit met zichzelf mochten spelen, omdat je dan langzaam krom ging groeien doordat het nat dat uit je piemel kwam afgetapt ruggenmerg was. Jongens die dat deden waren voorbestemd voor de hel of zouden in dit leven al gestraft worden doordat ze later alleen nog maar arbeider bij de steenfabriek of turfgraver in de Peel konden worden. Tja, waarschijnlijk had de pastoor gelijk, want de arbeiders die op het tasveld van de steenfabriek werkten, aan de overkant van de straat, waren allemaal wat grauw en mager en hadden dus de straf om arbeider te zijn zelf verdiend door als jongen in bed niet te slapen maar met zichzelf te spelen. En als ze het nou maar gebiecht hadden, want de pastoor wilde altijd van alle jongens weten hoe vaak ze het hadden gedaan, maar dat hadden ze waarschijnlijk niet gedurfd, ik ook niet trouwens, dus het was hun verdiende straf om in weer en wind stenen te vormen die later weer, als ze bevroren waren, moesten worden weggegooid. Vreemd volk, die arbeiders. Als ik in het poortje bij de straat stond, kon ik de schunnige moppen horen die ze aan elkaar vertelden. Het was geen leuke gedachte dat ik later een van hen zou moeten zijn en al dat gebazel van hen een leven lang zou moeten horen.

wordt vervolgd

Het verhaal Een nog schonere schijn van witheid van Ton van Reen werd uitgegeven op 26 februari 2012 in opdracht van De Bibliotheek Maas en Peel, ter gelegenheid van de heropening van de bibliotheek in Maasbree.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Haaks

Ver geslacht zijn wij van daar waar hutten

roken naar vuur en vlam, naar brandend,

sissend vlees. Waar jankende zuigelingen

tot voorvaderen werden, en beulen kappen

droegen boven gewette zwaarden, verroest

nu als de waarden waarvoor zij daalden.

De weg kwijt ben je immer als je die zoekt.

Als terugzien belemmert dat je weet waar je

opa’s hun eerste stappen zetten, waar je bent

als je schrijft dat je weet waar je was toen je

schreef dat je wist waar je was toen alles nog

rook naar inkt en die mooie schilfers die je zag

ontstaan bij het slijpen van het potlood dat nu

rust als een stompje bij stompjes. Zo haaks op

alles wat reeds lang bestaat staat alles wat nog

niet geschreven is.

Bert Bevers

Verschenen in jubileumnummer Ballustrada (t.g.v. 25-jarig bestaan), Middelburg, november 2011

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature