Fleurs du Mal Magazine

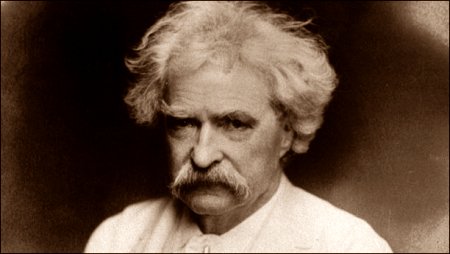

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

The First Writing-Machines

From My Unpublished Autobiography

Some days ago a correspondent sent in an old type-written sheet, faded by age, containing the following letter over the signature of Mark Twain:

“Hartford, March 19, 1875.

“Please do not use my name in any way. Please do not even divulge the fact that I own a machine. I have entirely stopped using the type-writer, for the reason that I never could write a letter with it to anybody without receiving a request by return mail that I would not only describe the machine, but state what progress I had made in the use of it, etc., etc. I don’t like to write letters, and so I don’t want people to know I own this curiosity-breeding little joker.”

A note was sent to Mr. Clemens asking him if the letter was genuine and whether he really had a type- writer as long ago as that. Mr. Clemens replied that his best answer is in the following chapter from his unpublished autobiography:

1904. Villa Quarto, Florence, January.

Dictating autobiography to a type-writer is a new experience for me, but it goes very well, and is going to save time and “language”—the kind of language that soothes vexation.

I have dictated to a type-writer before—but not autobiography. Between that experience and the present one there lies a mighty gap—more than thirty years! It is a sort of lifetime. In that wide interval much has happened—to the type-machine as well as to the rest of us. At the beginning of that interval a type- machine was a curiosity. The person who owned one was a curiosity, too. But now it is the other way about: the person who doesn’t own one is a curiosity. I saw a type-machine for the first time in—what year? I suppose it was 1873—because Nasby was with me at the time, and it was in Boston. We must have been lecturing, or we could not have been in Boston, I take it. I quitted the platform that season.

But never mind about that, it is no matter. Nasby and I saw the machine through a window, and went in to look at it. The salesman explained it to us, showed us samples of its work, and said it could do fifty- seven words a minute—a statement which we frankly confessed that we did not believe. So he put his type-girl to work, and we timed her by the watch. She actually did the fifty-seven in sixty seconds. We were partly convinced, but said it probably couldn’t happen again. But it did. We timed the girl over and over again—with the same result always: she won out. She did her work on narrow slips of paper, and we pocketed them as fast as she turned them out, to show as curiosities. The price of the machine was $125. I bought one, and we went away very much excited.

At the hotel we got out our slips and were a little disappointed to find that they all contained the same words. The girl had economized time and labor by using a formula which she knew by heart. However, we argued—safely enough—that the first type-girl must naturally take rank with the first billiard-player: neither of them could be expected to get out of the game any more than a third or a half of what was in it. If the machine survived—if it survived—experts would come to the front, by-and-by, who would double this girl’s output without a doubt. They would do one hundred words a minute—my talking speed on the platform. That score has long ago been beaten.

At home I played with the toy, repeating and repeating and repeating “The Boy stood on the Burning Deck,” until I could turn that boy’s adventure out at the rate of twelve words a minute; then I resumed the pen, for business, and only worked the machine to astonish inquiring visitors. They carried off many reams of the boy and his burning deck.

By-and-by I hired a young woman, and did my first dictating (letters, merely), and my last until now. The machine did not do both capitals and lower case (as now), but only capitals. Gothic capitals they were, and sufficiently ugly. I remember the first letter I dictated. It was to Edward Bok, who was a boy then. I was not acquainted with him at that time. His present enterprising spirit is not new—he had it in that early day. He was accumulating autographs, and was not content with mere signatures, he wanted a whole autograph letter. I furnished it—in type-machine capitals, signature and all. It was long; it was a sermon; it contained advice; also reproaches. I said writing was my trade, my bread-and- butter; I said it was not fair to ask a man to give away samples of his trade; would he ask the blacksmith for a horseshoe? would he ask the doctor for a corpse?

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

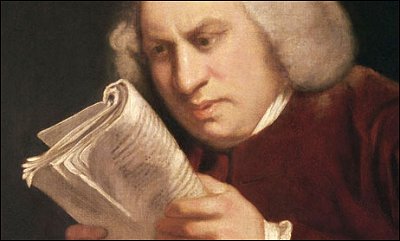

Samuel Johnson

(1709 – 1784)

Evening Ode

To Stella:

Evening now from purple wings

Sheds the grateful gifts she brings;

Brilliant drops bedeck the mead,

Cooling breezes shake the reed;

Shake the reed, and curl the stream

Silver’d o’er with Cynthia’s beam;

Near the chequer’d, lonely grove,

Hears, and keeps thy secrets, love!

Stella, thither let us stray,

Lightly o’er the dewy way.

Phoebus drives his burning car,

Hence, my lovely Stella, far;

In his stead, the queen of night

Round us pours a lambent light:

Light that seems but just to show

Breasts that beat, and cheeks that glow;

Let us now, in whisper’d joy,

Evening’s silent hours employ,

Silent best, and conscious shades,

Please the hearts that love invades,

Other pleasures give them pain,

Lovers all but love disdain.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Archive I-J

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

43

When most I wink then do mine eyes best see,

For all the day they view things unrespected,

But when I sleep, in dreams they look on thee,

And darkly bright, are bright in dark directed.

Then thou whose shadow shadows doth make bright

How would thy shadow’s form, form happy show,

To the clear day with thy much clearer light,

When to unseeing eyes thy shade shines so!

How would (I say) mine eyes be blessed made,

By looking on thee in the living day,

When in dead night thy fair imperfect shade,

Through heavy sleep on sightless eyes doth stay!

All days are nights to see till I see thee,

And nights bright days when dreams do show thee me.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

.jpg)

W i l l e m B i l d e r d i j k

(1756-1831)

By den dood van mijn Jongste Zoontjen

Il piano steffo li pianger non lascia.

(DANTE)

Thands niet verr’van u, mijn waarde; msst in uwen arm gekneld,

Zwelgt mijn hart te zilte tranen, van wier stroom mijn boezem welt.

Zwelgt het uw en mijne tranen : tranen, aan geen oog ontplascht,

Waar een ’t peil ontwassen droefheid in verademt, in ontlast!

Neen, maar tranen van den boezem die in de overstelping stikt,

En met onbevochtigde oogen naar den hollen doodstuip snikt!

Thands, van uwen arm omvangen…! Dierbare, ach, dezelfde smart,

De eigen pijl doorgrieft ons beiden, ja, doorreeg ons beider hart.

Siddrend, en den zinnen bijster, slaan wy ’t stijf en starrend oog

Op elkanders bleeke wangen — en wy zien die wangen droog!

ô Wat schouwspel, mijn Geliefde! wat gezicht vol aakligheên!

’t Wicht verstijft u in die armen! ik. in d’eigen arm, versteen!

Ach! wat riep ik uit, verdwaasde, by een vroeger harteslag

» Zalig, die zijn Vadertranen met een Egâ mengen mag! »

Thands vermag ik ’t, en geen afstand weigert ons die ijdle troost!

Vliet thands, tranen, kunt gy vlieten! vliet vereenigd op ons kroost!

Hemel! hemel, zoo weldadig! dit is dan uw dierbre gift!

Gift, zoo vurig afgebeden, en omhelsd met zoo veel drift!

Dit is ’t wichtjen, zoo bekoorlijk, daar ons diepgegriefd gemoed

Twee paar wreed verloren wichtjens zich zoo blijd in zag vergoed!

Dit, dit wichtjen, zoo aanvallig, in wiens hemelvollen lach,

’t Oudrenhart deze aard verdwijnen, en een Eden open zag!

In wiens zieldoorstralend lonkjen ’t lief en schuldloos zieltjen sprak,

Als ’t teedre rozenmondjen naar ons beider kusjens stak!

Wiens aanvallig zoet gekozel ons geheel het hart ontsloot,

Als zijn minlijk handendrukjen ons den blijden morgen bood!

Morgen, die ons hart vervulde met den zegen van ons lot!

Morgen, thands voor eeuwig duister — ! zonder hemel, zonder God!

Hemel!, hemel, zoo weldadig…! ach! ik weet dat gy het zijt;

Maar kan dit een Vader voelen, wien de vlijm het hart doorrijt!

’k Moest dan hieruit verre streken, uit een afgelegen Volk,

’k Moest dan hier door woeste baren, over stroom en waterkolk,

’k Moest dan hier het zand gaan zoeken dat uw lijkjen dekken mocht!

Hier uw asch een graf ontsluiten, was dan alles wat ik zocht!

’t Moest mijn Vaderland hervinden om te sterven io uw graf!

’t Was uw doodkist, dierbaar wichtjen, dat dit Vaderland my gaf!

’t Was uw doodkist — ! Groote hemel! ô Vergeef eens Vaders hart,

Wat het opwerp’, wat het smoore, in de wanhoop van zijn smart!

Leyden, ô onzalig Leijden, waar mijn boezem zoo naar trok!

Waar ik enkel zielrust hoopte, na zoo menig’ harteschok!

Waar mijn borst zich zou herhalen van haar eindeloos gezucht,

En mijn wallend bloed zich koelen in eene onberoerde lucht!

’t Is uw schoot dan, dierbaar Leyden, die mijn wichtjens asch verslindt!

Niets, niets zoch ik in uw wallen dan de doodbaar van mijn kind!

Hemel! hemel, zoo weldadig! Gy die heil en rampen zendt!

Moet my elke voetstap voeren tot vernieuwing van elland?

Moet ik land by land doorkruisen, zonder uitzicht, zonder troost,

Om heel de aarde te overspreiden met de lijkjens van mijn kroost!

Dierbaar wichtjen, thands het tiende, dat my ’s aardrijks schoot bewaart,

(Ach, hoe luttel, goede hemel, heeft uw deernis my gespaard!)

Dierbaar wichtjen, meer dan allen vastgeklonken aan mijn ziel!

Dierbaar wichtjen, waar my alles, alle vreugde, meê ontviel!

Dierbaar wichtjen, boven allen die het gruwzaam lot my nam,

My ten kenmerk van Gods zegen op de teêrste huwlijksvlam!

Ach, daar ligt gy, neêrgezegen, als een platgereden blom!

Daar, het vonkjen uitgetreden, waar uw hemels oog van glom!

Wek het bloemtjen, doe het rijzen, windtjen van den morgenstond!

Blaas het leven weêr in ’t vonkjen met den adem van uw’ mond!

Geef ons ’t leven in het leven met de lust des levens weêr!

Of, ô hemel, stort den vader by zijn zielloos wichtjen neêr!

ô Mijn boezem! kost gy schreien! Neen, gy kunt het niet, ô neen!

Krijt dan! krijt, en dring’ dit krijten door de verste stranden heen!

Krijt, en gil de holle wanden en hun doffen weêrgalm stom!

Krijt, en doe den klaagtoon zwijgen van het doodsche grafgebrom!

Zullen wand en doodklok treuren als van uwen rouw geroerd,

Gy versteenen, gy verharden, daar uw hart u wordt ontvoerd!

Wie kan wat gy uitstaat voelen? wie, gevoelen en weêrstaan!

Wie weêrstaan, en tot den hemel geen verwijten op doen gaan!

Wie het onbescheid niet vloeken, dat geweld doet aan Natuur

En het bloeden wil verbieden aan de diepe hartkwetsuur!

Krijt dan, ja! en help my krijten, ô mijn dierbare Echtgenoot!

Ach, dat stil, dat starziend zwijgen is my wreeder dan de dood.

Geef, Geliefde, geef een’ uittocht aan het hartverworgend leed!

Sla uw’ boezem, wring de handen, noem, ja, noem den hemel wreed!

Ja, verwensch ons-beider liefde, oorzaak van dat gruwzaam wee!

Vloek onze Echttoorts, vloek my-zelven die u liefde kennen deê!

Zoeter zal die vloek my wezen van uw diepgetroffen hart

Dan dit zwijgend nederzinken, in eene onoplosbre smart.

Lieve, druk u aan mijn’ boezem! in des harten Wel verstopt,

Snik naar adem, hijg naar lichtnis! voel hoe ’t siddrend bloed my klopt!

ô Herroepe ’t u aan ’t leven, dat gy hebt bemind om my!

ô Bemin het nog, mijn Waarde; ja, hoe wreed het leven zij!

ô Bemin het om het telgjen, ’t eenigst dat voor ons nog bloeit!

Voel de tranen op uw wangen, daar zijn oog u meê besproeit!

Voel de kusjens, die zijn mondtjen tusschen u en my verdeelt!

Voel ons-beider ziel vereenigd in ons beider evenbeeld!

Reik en hem en my de handen tot een blijk van teedre min!

En barst uit, mijn Zielsgeliefde; hoe uw doodsche smart niet in!

Gy bekoomt dan, lieve Gade! ach! ik voel uw hart weêr slaan.

Hijg, ô boezem, aan den mijnen! — Maar wat zie ik? ach, een’ traan!

Dank, ô hemel, voor dat traantjen! ô mijn lippen, kust het af!

Maar, ô neen, het eischt te vlieten op des lieven zuiglings graf.

Vliete ’t, ja, en onbedwongen! geve ’t aan uw smarten lucht!

Geve ’t doortocht aan den boezem voor een’ Moederlijken zucht!

Ach, daar welt hy, zoo weldadig! hy, die zucht die ’t hart ontlast;

En de stroom begint te groeien, die de wangen overplascht.

Schrei, mijn Weêrhelft, spaar geen tranen! ô die tranen zijn u zoet,

Wel hem, die ze mag vergieten als de rouw ze stijgen doet!

Smaak hun lichtnis, lieve Gade! Smaak haar, thands ons eenig kroost,

Dat, en met en om ons schreiend, ons uw tranen plengt ten troost!

Schreit, en wekt ook my die tranen, die my ’t schroevend leed misgunt!

Doe my schreien van genoegen, dat gy weder schreien kunt!

Ja, ik kan het, ik gevoel het! ja, mijn borst breekt snikkende uit.

Vloeit, mijne oogen! vloeit als stroomen, wee hem, die uw vlieten stuit!

Ja, betalen wy die schatting aan den noodeisch der Natuur!

Gy, heb dank voor deze tranen, immerweldoend Albestuur!

Immer weldoend! — Heilig Vader, gy die geeft en ook herneemt!

ô Vergeef het menschlijk harte, met uw raadsbesluiten vreemd!

ô Vergeef het, zoo ’t onzinnig, zoo ’t weêrspannig zich verzet!

Zoo ’t verwijt en wrevel ademt voor de klaagstem van ’t gebed!

Ach! het harte van een’ vader — God : gy kent, gy ziet het door!

Waar, waar is hy, die zijn kinders, en zijn reden niet verloor?

Immer weldoend! — wat is leven, zoo de dood een weldaad is?

Wat bezitten, zoo er weldaad is verbonden aan ’t gemis?

ô Mijn ziel, ô sluit uwe oogen! leer dit Godsgeheim ontzien!

Dood en leven zijn uw weldaad, Vader, laat uw wil geschiên!

Dierbaar, van mijn hart gereten, lief, en onvergeetbaar wicht!

’k Moet u ’s aardrijks schoot hergeven! wat ontzettelijke plicht!

Plicht, die ’t lijdend Vaderharte, dat naar zijne ontbinding smacht,

Van zijn tweetal lieve loten met zoo’n wellust had verwacht!

’k Moet, — en, uitgedreven balling, vreemd in eigen Vaderland,

Waar, waar berg ik u in de aarde, u, mijn hart, mijn ingewand!

Balling, ach! en zelfs geplonderd van mijn erflijk grafgesteent’,

Mag ik u geen rustplaats schenken by voorvaderlijk gebeent’.

Schokt niet, ouderlijke beenders, staat niet op om dezen smaad,

Zoo het stof van uwe kinders verre van uw stof vergaat!

Is uw grafkuil ons gesloten, ga, mijn teêrgeliefde kind,

Ga ter rust (ik zal u volgen) by uws vaders diersten vrind. —

Gy, die steeds voor mij een vader, een teêrhartig vader waart,

En wiens oogen nog te sluiten voor mijn weêrkomst was bespaard,

Gy, ô Halsvrind, wien mijn voeten wagglend leiden naar uw graf,

Zie, zie op! een deel uws hartvriends daalt reeds in uw armen af.

ô Ontfange ’t met uw beenders haast het nietig overschot,

Als my ’t uur der rust zal dagen, dat bestemd is van mijn’ God!

Lieve Heiland, die ons leven en ons sterven hebt beproefd!

Die den mensch hebt aangetogen, en eens Engels troost behoefd!

Gy, gy hebt de kleine wichtjens van uw kniën niet belet,

Gy, gy zegende in uw armen dezen zegen van het bed!

Gy, gy hebt hem aangenomen tot uw eigendom en kroost!

Mijn Alexis, ja, was de uwe! Lieve Jezus, dit geeft troost.

Teedre Weêrhelft, wees gelaten! leg uw handen in mijn hand!

Vlechten we onzer beider armen om ons thands nog eenig pand.

Hy, hy is onze eerste zegen, hem vroeg de Almacht niet weêrom!

Hy getuigt ons van Gods liefde. — Kom, mijn levens leven, kom ! —

Biên wy Jezus d’ons ontrukte, schreiend, ja, maar willig aan!

Hem als hemeling te groeten, ô verdient dat niet een’ traan?

Hem, na ’t doorgeworsteld leven, met geheel een Englen stoet,

Uit uw’ zuivren schoot geboren, voortgesproten uit mijn bloed,

Hem, hem alleen weêr te omhelzen in de volheid van Gods heil — !

Lieve Gade, deze wellust is voor niets dan tranen veil.

Dierbre Goël,.ja, wy voelen, wy erkennen die genâ;

Sla ons met ontfermende oogen, sla ons in dees droefheid gâ!

Gun, ô gun dit oovrig telgjen beider vurigen gebeên!

Gun ons, hem (genadig Heiland) in uw’ hemel voor te treên!

Voor te treden! Lieve Jezus! waar zijn heil, zijn erfdeel zij!

Meer dan dit voor hem te vragen laat ons ’t Ouderhart niet vrij.

Eer of schatten, aardsche wijsheid, waar het hart zich op verheft — !

Neen, zij needrigheid zijn luister, zy, die grootheid overtreft!

Gy, gy zult hen niet begeven, die uw bloed geëigend heeft.

Gy geeft nooddruft, gy verzading, wie op uw betrouwen leeft.

Alles heeft hy, dierbre Heiland, die uw liefde slechts bezit!

Schenk haar aan ons eenig knaapjen, en hy hebb’ nooit ander wit!

Geef ons uit zijn jonge lenden spruiten tot dien schoonen dag,

Die uwe Almacht op de wolken als Hersteller groeten mag!

En, behaagt het u, ô Vader, gy die neemt en ook hergeeft!

Troost ons weder met een telgjen, waar Alexis in herleeft!

1806

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive A-B, Bilderdijk, Willem

Jacqueline E. van der Waals

(1868-1922)

Melancolia

Toen ik door het maanlicht liep

En de paden meed,

Bang, dat ik den tuin, die sliep,

Wakkerschrikken deed

Door het ritselend gerucht

Van mijn kleed en voet –

De oude boomen! die een zucht

Wakkerschrikken doet.

Toen ik naar den vijver ging

Door het korte gras,

Naar den boom die overhing

In den vijverplas,

Waar het water inkt geleek,

En zo roerloos sliep,

Of het oog in ‘t duister keek

Van een peilloos diep,

Waar het windgefluister klonk

Door het popelblad…

Weet gij, wie op d’ elzentronk

Mij te wachten zat?

Vleermuisvleugelige vrouw,

Die mij eeuwig jong,

‘t Eeuwig oude lied van rouw

Vaak te voren zong,

Tot ik in den maneschijn

Zacht heb meegeschreid

Met het eeuwenoud refrein:

“Alles ijdelheid.”

Hebt ge hier op mij gewacht,

Denkend, dat ik sliep?

Hebt gij zóó aan mij gedacht,

Dat uw geest mij riep,

Dat ik staan kwam aan het raam

En onrustig werd

Door het roepen van mijn naam

Uit de lichte vert’?….

Toen ik u hier wachten vond

En met stillen schrik

In den peilloos diepen grond

Staarde van uw blik,

Toen ik zwijgend binnentrad

En in zwarte schauw

Uwer vleuglen nederzat,

Zwartgewiekte vrouw,

Heb ik, met uw hoofd gevleid,

Liefste aan mijn hart,

Zachtkens met u meê geschreid

Om der dingen ijdelheid

Om onze oude smart.

Jacqueline E. van der Waals gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Waals, Jacqueline van der

Annette von Droste-Hülshoff

(1797-1848)

Poesie

Frägst du mich im Rätselspiele,

Wer die zarte lichte Fei,

Die sich drei Kleinoden gleiche

Und ein Strahl doch selber sei?

Ob ich’s rate? ob ich fehle?

Liebchen, pfiffig war ich nie,

Doch in meiner tiefsten Seele

Hallt es: das ist Poesie!

Jener Strahl, der, Licht und Flamme,

Keiner Farbe zugetan,

Und doch, über alles gleitend,

Tausend Farben zündet an,

Jedes Recht und keines Eigen.

Die Kleinode nenn’ ich dir:

Den Türkis, den Amethysten

Und der Perle edle Zier.

Poesie gleicht dem Türkise,

Dessen frommes Auge bricht,

Wenn verborgner Säure Brodem

Nahte seinem reinen Licht;

Dessen Ursprung keiner kündet,

Der wie Himmelsgabe kam

Und des Himmels milde Bläue

Sich zum milden Zeichen nahm.

Und sie gleicht dem Amethysten,

Der sein veilchenblau Gewand

Läßt zu schnödem Grau erblassen

An des Ungetreuen Hand;

Der, gemeinen Götzen frönend,

Sinkt zu niedren Steines Art,

Und nur einer Flamme dienend

Seinen edlen Glanz bewahrt;

Gleicht der Perle auch, der zarten,

Am Gesunden tauig klar,

Aber saugend, was da Krankes

In geheimsten Adern war;

Sahst du niemals ihre Schimmer

Grünlich, wie ein rnodernd Tuch?

Eine Perle bleibt es immer,

Aber die ein Siecher trug.

Und du lächelst meiner Lösung,

Flüsterst wie ein Wiederhall:

Poesie gleicht dem Pokale

Aus venedischem Kristall!

Gift hinein und schwirrend singt er

Schwanenliedes Melodie,

Dann in tausend Trümmer klirrend,

Und hin ist die Poesie!

Annette von Droste-Hülshoff poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive G-H

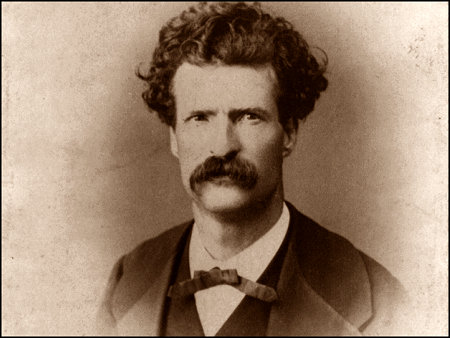

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

An Entertaining Article

I take the following paragraph from an article in the Boston Advertiser:

“Perhaps the most successful flights of the humor of Mark Twain have been descriptions of the persons who did not appreciate his humor at all. We have become familiar with the Californians who were thrilled with terror by his burlesque of a newspaper reporter’s way of telling a story, and we have heard of the Pennsylvania clergyman who sadly returned his Innocents Abroad to the book-agent with the remark that ‘the man who could shed tears over the tomb of Adam must be an idiot.’ But Mark Twain may now add a much more glorious instance to his string of trophies. The Saturday Review, in its number of October 8th, reviews his book of travels, which has been republished in England, and reviews it seriously. We can imagine the delight of the humorist in reading this tribute to his power; and indeed it is so amusing in itself that he can hardly do better than reproduce the article in full in his next monthly Memoranda.”

(Publishing the above paragraph thus, gives me a sort of authority for reproducing the Saturday Review’s article in full in these pages. I dearly wanted to do it, for I cannot write anything half so delicious myself. If I had a cast-iron dog that could read this English criticism and preserve his austerity, I would drive him off the door-step.)

(From the London “Saturday Review.”)

“Reviews of New Books”

“The Innocents Abroad. A Book of Travels. By Mark Twain. London: Hotten, publisher. 1870. “Lord Macaulay died too soon. We never felt this so deeply as when we finished the last chapter of the above- named extravagant work. Macaulay died too soon—for none but he could mete out complete and comprehensive justice to the insolence, the impertinence, the presumption, the mendacity, and, above all, the majestic ignorance of this author.

“To say that the Innocents Abroad is a curious book, would be to use the faintest language—would be to speak of the Matterhorn as a neat elevation or of Niagara as being ‘nice’ or ‘pretty.’ ‘Curious’ is too tame a word wherewith to describe the imposing insanity of this work. There is no word that is large enough or long enough. Let us, therefore, photograph a passing glimpse of book and author, and trust the rest to the reader. Let the cultivated English student of human nature picture to himself this Mark Twain as a person capable of doing the following-described things—and not only doing them, but with incredible innocence printing them calmly and tranquilly in a book. For instance:

“He states that he entered a hair-dresser’s in Paris to get shaved, and the first ‘rake’ the barber gave with his razor it loosened his ‘hide’ and lifted him out of the chair.

“This is unquestionably exaggerated. In Florence he was so annoyed by beggars that he pretends to have seized and eaten one in a frantic spirit of revenge. There is, of course, no truth in this. He gives at full length a theatrical programme seventeen or eighteen hundred years old, which he professes to have found in the ruins of the Coliseum, among the dirt and mould and rubbish. It is a sufficient comment upon this statement to remark that even a cast-iron programme would not have lasted so long under such circumstances. In Greece he plainly betrays both fright and flight upon one occasion, but with frozen efforntery puts the latter in this falsely tame form: ‘We sidled towards the Piræus.’ ‘Sidled,’ indeed! He does not hesitate to intimate that at Ephesus, when his mule strayed from the proper course, he got down, took him under his arm, carried him to the road again, pointed him right, remounted, and went to sleep contentedly till it was time to restore the beast to the path once more. He states that a growing youth among his ship’s passengers was in the constant habit of appeasing his hunger with soap and oakum between meals. In Palestine he tells of ants that came eleven miles to spend the summer in the desert and brought their provisions with them; yet he shows by his description of the country that the feat was an impossibility. He mentions, as if it were the most commonplace of matters, that he cut a Moslem in two in broad daylight in Jerusalem, with Godfrey de Bouillon’s sword, and would have shed more blood if he had had a graveyard of his own. These statements are unworthy a moment’s attention. Mr. Twain or any other foreigner who did such a thing in Jerusalem would be mobbed, and would infallibly lose his life. But why go on? Why repeat more of his audacious and exasperating falsehoods? Let us close fittingly with this one: he affirms that ‘in the mosque of St. Sophia at Constantinople I got my feet so stuck up with a complication of gums, slime, and general impurity, that I wore out more than two thousand pair of bootjacks getting my boots off that night, and even then some Christian hide peeled off with them.’ It is monstrous. Such statements are simply lies—there is no other name for them. Will the reader longer marvel at the brutal ignorance that pervades the American nation when we tell him that we are informed upon perfectly good authority that this extravagant compilation of falsehoods, this exhaustless mine of stupendous lies, this Innocents Abroad, has actually been adopted by the schools and colleges of several of the States as a text-book!

“But if his falsehoods are distressing, his innocence and his ignorance are enough to make one burn the book and despise the author. In one place he was so appalled at the sudden spectacle of a murdered man, unveiled by the moonlight, that he jumped out of the window, going through sash and all, and then remarks with the most childlike simplicity that he ‘was not scared, but was considerably agitated.’ It puts us out of patience to note that the simpleton is densely unconscious that Lucrezia Borgia ever existed off the stage. He is vulgarly ignorant of all foreign languages, but is frank enough to criticise the Italians’ use of their own tongue. He says they spell the name of their great painter ‘Vinci, but pronounce it Vinchy’—and then adds with a naïveté possible only to helpless ignorance, ‘foreigners always spell better than they pronounce.’ In another place he commits the bald absurdity of putting the phrase ‘tare an ouns’ into an Italian’s mouth. In Rome he unhesitatingly believes the legend that St. Philip Neri’s heart was so inflamed with divine love that it burst his ribs—believes it wholly because an author with a learned list of university degrees strung after his name endorses it—‘otherwise,’ says this gentle idiot, ‘I should have felt a curiosity to know what Philip had for dinner.’ Our author makes a long, fatiguing journey to the Grotto del Cane on purpose to test its poisoning powers on a dog—got elaborately ready for the experiment, and then discovered that he had no dog. A wiser person would have kept such a thing discreetly to himself, but with this harmless creature everything comes out. He hurts his foot in a rut two thousand years old in exhumed Pompeii, and presently, when staring at one of the cinder-like corpses unearthed in the next square, conceives the idea that may be it is the remains of the ancient Street Commissioner, and straightway his horror softens down to a sort of chirpy contentment with the condition of things. In Damascus he visits the well of Ananias, three thousand years old, and is as surprised and delighted as a child to find that the water is ‘as pure and fresh as if the well had been dug yesterday.’ In the Holy Land he gags desperately at the hard Arabic and Hebrew Biblical names, and finally concludes to call them Baldwinsville, Williamsburgh, and so on, ‘for convenience of spelling.’

“We have thus spoken freely of this man’s stupefying simplicity and innocence, but we cannot deal similarly with his colossal ignorance. We do not know where to begin. And if we knew where to begin, we certainly would not know where to leave off. We will give one specimen, and one only. He did not know, until he got to Rome, that Michael Angelo was dead! And then, instead of crawling away and hiding his shameful ignorance somewhere, he proceeds to express a pious, grateful sort of satisfaction that he is gone and out of his troubles!

“No, the reader may seek out the author’s exhibition of his uncultivation for himself. The book is absolutely dangerous, considering the magnitude and variety of its misstatements, and the convincing confidence with which they are made. And yet it is a text-book in the schools of America.

The poor blunderer mouses among the sublime creations of the Old Masters, trying to acquire the elegant proficiency in art-knowledge, which he has a groping sort of comprehension is a proper thing for the travelled man to be able to display. But what is the manner of his study? And what is the progress he achieves? To what extent does he familiarize himself with the great pictures of Italy, and what degree of appreciation does he arrive at? Read:

“‘When we see a monk going about with a lion and looking up into heaven, we know that that is St. Mark. When we see a monk with a book and a pen, looking tranquilly up to heaven, trying to think of a word, we know that that is St. Matthew. When we see a monk sitting on a rock, looking tranquilly up to heaven, with a human skull beside him, and without other baggage, we know that that is St. Jerome. Because we know that he always went flying light in the matter of baggage. When we see other monks looking tranquilly up to heaven, but having no trade-mark, we always ask who those parties are. We do this because we humbly wish to learn.’

“He then enumerates the thousands and thousands of copies of these several pictures which he has seen, and adds with accustomed simplicity that he feels encouraged to believe that when he has seen ‘Some More’ of each, and had a larger experience, he will eventually ‘begin to take an absorbing interest in them’—the vulgar boor.

“That we have shown this to be a remarkable book, we think no one will deny. That it is a pernicious book to place in the hands of the confiding and uninformed, we think we have also shown. That the book is a deliberate and wicked creation of a diseased mind, is apparent upon every page. Having placed our judgement thus upon record, let us close with what charity we can, by remarking that even in this volume there is some good to be found; for whenever the author talks of his own country and lets Europe alone, he never fails to make himself interesting, and not only interesting, but instructive. No one can read without benefit his occasional chapters and paragraphs, about life in the gold and silver mines of California and Nevada; about the Indians of the plains and deserts of the West, and their cannibalism; about the raising of vegetables in kegs of gunpowder by the aid of two or three teaspoonfuls of guano; about the moving of small farms from place to place at night in wheelbarrows to avoid taxes; and about a sort of cows and mules in the Humboldt mines, that climb down chimneys and disturb the people at night. These matters are not only new, but are well worth knowing. It is a pity the author did not put in more of the same kind. His book is well written and is exceedingly entertaining, and so it just barely escaped being quite valuable also.”

(One month later)

Latterly I have received several letters, and see a number of newspaper paragraphs, all upon a certain subject, and all of about the same tenor. I here give honest specimens. One is from a New York paper, one is from a letter from an old friend, and one is from a letter from a New York publisher who is a stranger to me. I humbly endeavor to make these bits tooth-some with the remark that the article they are praising (which appeared in the December Galaxy, and pretended to be a criticism from the London Saturday Review on my Innocents Abroad) was written by myself, every line of it:

“The Herald says the richest thing out is the ‘serious critique’ in the London Saturday Review, on Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad. We thought before we read it that it must be ‘serious,’ as everybody said so, and were even ready to shed a few tears; but since perusing it, we are bound to confess that next to Mark Twain’s ‘Jumping Frog’ it’s the finest bit of humor and sarcasm that we’ve come across in many a day.”

(I do not get a compliment like that every day.)

“I used to think that your writings were pretty good, but after reading the criticism in The Galaxy from the London Review, have discovered what an ass I must have been. If suggestions are in order, mine is, that you put that article in your next edition of the Innocents, as an extra chapter, if you are not afraid to put your own humor in competition with it. It is as rich a thing as I ever read.”

(Which is strong commendation from a book publisher.)

“The London Reviewer, my friend, is not the stupid, ‘serious’ creature he pretends to be, I think; but, on the contrary, has a keen appreciation and enjoyment of your book. As I read his article in The Galaxy, I could imagine him giving vent to many a hearty laugh. But he is writing for Catholics and Established Church people, and high-toned, antiquated, conservative gentility, whom it is a delight to him to help you shock, while he pretends to shake his head with owlish density. He is a magnificent humorist himself.” (Now that is graceful and handsome. I take off my hat to my life-long friend and comrade, and with my feet together and my fingers spread over my heart, I say, in the language of Alabama, “You do me proud.”)

I stand guilty of the authorship of the article, but I did not mean any harm. I saw by an item in the Boston Advertiser that a solemn, serious critique on the English edition of my book had appeared in the London Saturday Review, and the idea of such a literary breakfast by a stolid, ponderous British ogre of the quill was too much for a naturally weak virtue, and I went home and burlesqued it—revelled in it, I may say. I never saw a copy of the real Saturday Review criticism until after my burlesque was written and mailed to the printer. But when I did get hold of a copy, I found it to be vulgar, awkwardly written, ill- natured, and entirely serious and in earnest. The gentleman who wrote the newspaper paragraph above quoted had not been misled as to its character.

If any man doubts my word now, I will kill him. No, I will not kill him; I will win his money. I will bet him twenty to one, and let any New York publisher hold the stakes, that the statements I have above made as to the authorship of the article in question are entirely true. Perhaps I may get wealthy at this, for I am willing to take all the bets that offer; and if a man wants larger odds, I will give him all he requires. But he ought to find out whether I am betting on what is termed “a sure thing” or not before he ventures his money, and he can do that by going to a public library and examining the London Saturday Review of October 8th, which contains the real critique.

Bless me, some people thought that I was the “sold” person!

P. S.—I cannot resist the temptation to toss in this most savory thing of all—this easy, graceful, philosophical disquisition, with its happy, chirping confidence. It is from the Cincinnati Enquirer:

“Nothing is more uncertain than the value of a fine cigar. Nine smokers out of ten would prefer an ordinary domestic article, three for a quarter, to a fifty-cent Partaga, if kept in ignorance of the cost of the latter. The flavor of the Partaga is too delicate for palates that have been accustomed to Connecticut seed leaf. So it is with humor. The finer it is in quality, the more danger of its not being recognized at all. Even Mark Twain has been taken in by an English review of his Innocents Abroad. Mark Twain is by no means a coarse humorist, but the Englishman’s humor is so much finer than his, that he mistakes it for solid earnest, and ‘larfs most consumedly.’ ”

A man who cannot learn stands in his own light. Hereafter, when I write an article which I know to be good, but which I may have reason to fear will not, in some quarters, be considered to amount to much, coming from an American, I will aver that an Englishman wrote it and that it is copied from a London journal. And then I will occupy a back seat and enjoy the cordial applause.

(Still later)

“Mark Twain at last sees that the Saturday Review’s criticism of his Innocents Abroad was not serious, and he is intensely mortified at the thought of having been so badly sold. He takes the only course left him, and in the last Galaxy claims that he wrote the criticism himself, and published it in The Galaxy to sell the public. This is ingenious, but unfortunately it is not true. If any of our readers will take the trouble to call at this office we will show them the original article in the Saturday Review of October 8th, which, on comparison, will be found to be identical with the one published in The Galaxy. The best thing for Mark to do will be to admit that he was sold, and say no more about it.”

The above is from the Cincinnati Enquirer, and is a falsehood. Come to the proof. If the Enquirer people, through any agent, will produce at The Galaxy office a London Saturday Review of October 8th, containing an “article which, on comparison, will be found to be that identical with the one published in The Galaxy, I will pay to that agent five hundred dollars cash. Moreover, if at any specified time I fail to produce at the same place a copy of the London Saturday Review of October 8th, containing a lengthy criticism upon the Innocents Abroad, entirely different, in every paragraph and sentence, from the one I published in The Galaxy, I will pay to the Enquirer agent another five hundred dollars cash. I offer Sheldon & Co., publishers, 500 Broadway, New York, as my “backers.” Any one in New York, authorized by the Enquirer, will receive prompt attention. It is an easy and profitable way for the Enquirer people to prove that they have not uttered a pitiful, deliberate falsehood in the above paragraphs. Will they swallow that falsehood ignominiously, or will they send an agent to The Galaxy office? I think the Cincinnati Enquirer must be edited by children.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

Prosper van Langendonck

(1862-1920)

Ik had u niet gevraagd

Ik had u niet gevraagd: gij zijt gekomen…

Veel bloemen bloeiden in mijn stillen tuin;

de zoele Meiwind wiegde kruin tot kruin

vol teere bloesems, frisch als lentedroomen.

Ik had u niet gevraagd: gij zijt gekomen,

Muze der smarten, in mijn stillen tuin;

daar bogen levenloos nu twijg en kruin,

en bloem en bald verschroeide op plant en boomen.

O geef mij weer mijn slanke en eedle jeugd,

mijn argelooze liefde en heldre vreugd,

nauw door een waas van weemoed overtogen.

‘k Voel niets meer dan dien eeuwgen wanhoopsdrang,

maar, door uw felste woede en haat bewogen,

zal ik u vloeken tot mijn laatsten zang.

Prosper van Langendonck gedicht

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L

.jpg)

Nachrichten aus Berlin: Reflections

Photos Anton K. – Berlin 2010

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, Nachrichten aus Berlin

.jpg)

Gabriele D’Annunzio

(1863-1938)

Intra du’ Arni

Ecco l’isola di Progne

ove sorridi

ai gridi

della ronine trace

che per le molli crete

ripete

le antiche rampogne

al re fallace,

e senza pace,

appena aggiorna,

va e torna

vigile all’opra

nidace,

né si posa né si tace

se non si copra

d’ombra la riviera

e sera

circa l’isola leggiera

di canne e di crete,

che all’aulete

dà flauti,

alla migrante nidi

e, se sorridi, lauti

giacigli all’amor folle.

Ecco l’isola molle.

Ecco l’isola molle

intra du’ Arni,

cuna di carmi,

ove cantano l’Estate

le canne virenti

ai vènti

in varii modi,

non odi ?,

quasi di nodi

prive e di midolle,

quasi inspirate

da volubili bocche

e tocche

da dita sapienti,

quasi con arte elette

e giunte insieme a schiera,

su l’esempio divino,

con lino

attorto e con cera

sapida di miele,

a sette a sette,

quasi perfette

sampogne.

Ecco l’isola di Progne

Gabriele D’Annunzio poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, D'Annunzio, Gabriele

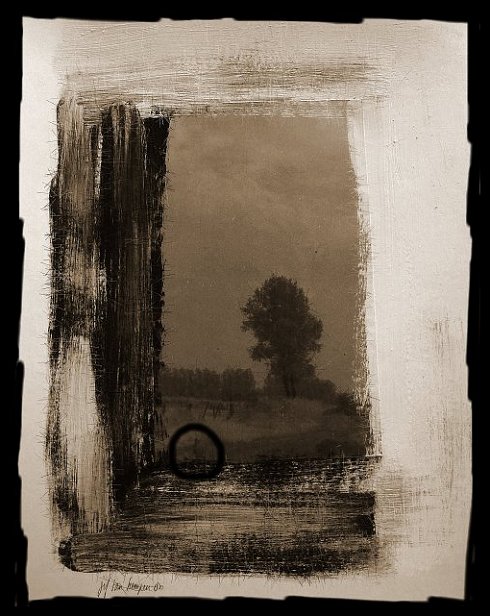

jef van kempen 1980

The Hare

► website Museum of lost concepts

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Dutch Landscapes, FDM Art Gallery, Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Museum of Lost Concepts

.jpg)

W i l l e m B i l d e r d i j k

(1756-1831)

Op een Grafteken voor eene Ongelukkige

AAN DEN OPENBARE WEG BEGRAVEN

Met de doodwaâ om de leden,

’t Hoofd op luttel stroo gebedt,

Lig ik aan den weg vertreden,

Eens de baan der deugd ontgleden,

En mijn naam werd lastersmet.

’t Stormweêr moog dit gras doen golven,

’t Zand verwaaien dat my dekt,

’t Lichaam in den kuil ontdolven

Leevren tot een aas der wolven;

’k Wacht op d’Engel die my wekt.

God is goed; maar rustloos beven

Wroeging, door geen tijd gesmoord,

Zal door ’s wreedaarts boezem zweven,

Die de lust van ’t argloos leven

In mijne Onschuld heeft vermoord.

Moog hem God genâ bewijzen

Om die wroeging, om dat leed,

’k Zal in dubble vreugd verrijzen

Om diens Heilands naam te prijzen,

Wien de menschheid heeft omkleed.

1823.

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Bilderdijk, Willem

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature