Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

O s c a r W i l d e

(1854-1900)

My Voice

Within this restless, hurried, modern world

We took our hearts’ full pleasure–You and I,

And now the white sails of our ship are furled,

And spent the lading of our argosy.

Wherefore my cheeks before their time are wan,

For very weeping is my gladness fled,

Sorrow has paled my young mouth’s vermilion,

And Ruin draws the curtains of my bed.

But all this crowded life has been to thee

No more than lyre, or lute, or subtle spell

Of viols, or the music of the sea

That sleeps, a mimic echo, in the shell.

.jpg)

O s c a r W i l d e p o e t r y

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Wilde, Oscar

.jpg)

![]()

Namen noemen. Purisme of respect?

door Lauran Toorians

![]()

‘Keltische studies’ de brede en algemeen geaccepteerde omschrijving voor de academische discipline die zich bezighoudt met de Keltische talen en hun letterkunde. Het is geen discipline die in Nederland (of Vlaanderen) op grote schaal wordt beoefend en ook onder het bredere publiek is de kennis van dit vakgebied gering, en dat ondanks dat ‘de Kelten’ al geruime tijd uiterst modieus zijn. Een gevolg hiervan is, dat er veel onduidelijkheid bestaat over de te bezigen terminologie, zeker waar het gaat om het benoemen van de verschillende talen, terwijl ook de correcte Nederlandse spelling van die namen problematisch is.

Het begint al met het vakgebied zelf. Wanneer we de ‘keltische studies’ met één woord willen benoemen, hebben we keuze uit twee mogelijkheden: keltistiek en keltologie. Beide namen voor het vak zijn in Nederlandstalige literatuur terug te vinden, en een duidelijke voorkeur lijkt niet te bestaan.

Van de Keltische talen is het Iers de enige met een status als nationale taal in de Ierse Republiek en als EG-taal (er staat Iers in uw paspoort). In het Iers zelf heet deze taal Gaeilge, wat in oudere literatuur in het Nederlands nog wel eens Gaelisch oplevert. Voor oudere taalfasen spreken we van Oudiers en Middeliers. Onder invloed van het Engels hebben veel auteurs de neiging hiervoor in het Nederlands ‘Oud Iers’ te schrijven, maar dat is toch iets anders. Bovendien is het goed gebruik om ook bijvoorbeeld Oudfrans en Middelnederlands als één woord te schrijven. Wel is het – ook in navolging van het Engels – gebruikelijk geworden om te spreken van Modern Iers, Modern Bretons, enz., en niet van bijvoorbeeld Nieuwiers. Dit in tegenstelling tot termen als Nieuwnederlands en Nieuwhoogduits, zoals die in de germanistiek gebruikelijk zijn.

Uit het Oudiers ontstonden, naast de latere varianten van het Iers in Ierland, het Gaelg Vanninagh op het Eiland Man, dat we normaal aanduiden als Manx, en het Gàedhlig in Schotland. Het zal duidelijk zijn dat de sprekers van deze drie talen in feite allemaal dezelfde term gebruiken en we in het Nederlands dan ook al deze talen Gaelisch zouden kunnen noemen. De eigen naam van het Manx betekent letterlijk ‘het Gaelisch van (het Eiland) Man’. De Keltische taal van Schotland behoeft in het Nederlands ook een dergelijke toevoeging en wordt in het Nederlands Schots-Gaelisch genoemd. In recente literatuur vinden we hiervoor vaak ‘Schots-Gaelic’, met een deels Engelse spelling (en uitspraak), maar een goede reden daarvoor ontbreekt. De taal uitsluitend ‘Schots’ noemen, wekt verwarring met het Engelse dialect (of de Germaanse taal, hierover bestaat onenigheid) van Schotland, dat zowel in die taal zelf als in het Engels Scots heet. Andere benamingen die voor deze taal worden gebezigd zijn Broad Scots (ongeveer ‘plat Schots’) en Lallands (‘Lowland’s’).

In het Engelse spraakgebruik is het mogelijk beide talen (Iers en Schots-Gaelisch) ‘Gaelisch’ te noemen en daarbij in de uitspraak te laten horen om welke taal het gaat. Gaeilge (Iers) klinkt dan in het Engels als Gaelic met in de eerste lettergreep een –ee– als in zeef, terwijl hetzelfde Engelse woord voor Gàedhlig klinkt met een –a– als in appel. In oudere literatuur in het Nederlands vinden we Schots(ch)-Gaelisch, en soms ook Gaëlisch……………………………………………………….

Lees de volledige tekst van Lauran Toorians: ![]()

![]()

Lauran Toorians: Namen noemen. Purisme of respect?

kempis poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

.jpg)

Ein Landarzt

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Ich war in großer Verlegenheit: eine dringende Reise stand mir bevor; ein Schwerkranker wartete auf mich in einem zehn Meilen entfernten Dorfe; starkes Schneegestöber füllte den weiten Raum zwischen mir und ihm; einen Wagen hatte ich, leicht, großräderig, ganz wie er für unsere Landstraßen taugt; in den Pelz gepackt, die Instrumententasche in der Hand, stand ich reisefertig schon auf dem Hofe; aber das Pferd fehlte, das Pferd. Mein eigenes Pferd war in der letzten Nacht, infolge der Überanstrengung in diesem eisigen Winter, verendet; mein Dienstmädchen lief jetzt im Dorf umher, um ein Pferd geliehen zu bekommen; aber es war aussichtslos, ich wußte es, und immer mehr vom Schnee überhäuft, immer unbeweglicher werdend, stand ich zwecklos da. Am Tor erschien das Mädchen, allein, schwenkte die Laterne; natürlich, wer leiht jetzt sein Pferd her zu solcher Fahrt? Ich durchmaß noch einmal den Hof; ich fand keine Möglichkeit; zerstreut, gequält stieß ich mit dem Fuß an die brüchige Tür des schon seit Jahren unbenützten Schweinestalles. Sie öffnete sich und klappte in den Angeln auf und zu. Wärme und Geruch wie von Pferden kam hervor. Eine trübe Stallaterne schwankte drin an einem Seil. Ein Mann, zusammengekauert in dem niedrigen Verschlag, zeigte sein offenes blauäugiges Gesicht. »Soll ich anspannen?« fragte er, auf allen Vieren hervorkriechend. Ich wußte nichts zu sagen und beugte mich nur, um zu sehen, was es noch in dem Stalle gab. Das Dienstmädchen stand neben mir. »Man weiß nicht, was für Dinge man im eigenen Hause vorrätig hat,« sagte es, und wir beide lachten. »Hollah, Bruder, hollah, Schwester!« rief der Pferdeknecht, und zwei Pferde, mächtige flankenstarke Tiere schoben sich hintereinander, die Beine eng am Leib, die wohlgeformten Köpfe wie Kamele senkend, nur durch die Kraft der Wendungen ihres Rumpfes aus dem Türloch, das sie restlos ausfüllten.

Aber gleich standen sie aufrecht, hochbeinig, mit dicht ausdampfendem Körper. »Hilf ihm,« sagte ich, und das willige Mädchen eilte, dem Knecht das Geschirr des Wagens zu reichen. Doch kaum war es bei ihm, umfaßt es der Knecht und schlägt sein Gesicht an ihres. Es schreit auf und flüchtet sich zu mir; rot eingedrückt sind zwei Zahnreihen in des Mädchens Wange. »Du Vieh,« schreie ich wütend, »willst du die Peitsche?«, besinne mich aber gleich, daß es ein Fremder ist; daß ich nicht weiß, woher er kommt, und daß er mir freiwillig aushilft, wo alle andern versagen. Als wisse er von meinen Gedanken, nimmt er meine Drohung nicht übel, sondern wendet sich nur einmal, immer mit den Pferden beschäftigt, nach mir um. »Steigt ein,« sagt er dann, und tatsächlich: alles ist bereit. Mit so schönem Gespann, das merke ich, bin ich noch nie gefahren und ich steige fröhlich ein. »Kutschieren werde aber ich, du kennst nicht den Weg,« sage ich. »Gewiß,« sagt er, »ich fahre gar nicht mit, ich bleibe bei Rosa.« »Nein,« schreit Rosa und läuft im richtigen Vorgefühl der Unabwendbarkeit ihres Schicksals ins Haus; ich höre die Türkette klirren, die sie vorlegt; ich höre das Schloß einspringen; ich sehe, wie sie überdies im Flur und weiterjagend durch die Zimmer alle Lichter verlöscht, um sich unauffindbar zu machen.

»Du fährst mit,« sage ich zu dem Knecht, »oder ich verzichte auf die Fahrt, so dringend sie auch ist. Es fällt mir nicht ein, dir für die Fahrt das Mädchen als Kaufpreis hinzugeben.« »Munter!« sagt er; klatscht in die Hände; der Wagen wird fortgerissen, wie Holz in die Strömung; noch höre ich, wie die Tür meines Hauses unter dem Ansturm des Knechtes birst und splittert, dann sind mir Augen und Ohren von einem zu allen Sinnen gleichmäßig dringenden Sausen erfüllt. Aber auch das nur einen Augenblick, denn, als öffne sich unmittelbar vor meinem Hoftor der Hof meines Kranken, bin ich schon dort; ruhig stehen die Pferde; der Schneefall hat aufgehört; Mondlicht ringsum; die Eltern des Kranken eilen aus dem Haus; seine Schwester hinter ihnen; man hebt mich fast aus dem Wagen; den verwirrten Reden entnehme ich nichts; im Krankenzimmerist die Luft kaum atembar; der vernachlässigte Herdofen raucht; ich werde das Fenster aufstoßen; zuerst aber will ich den Kranken sehen. Mager, ohne Fieber, nicht kalt, nicht warm, mit leeren Augen, ohne Hemd hebt sich der Junge unter dem Federbett, hängt sich an meinen Hals, flüstert mir ins Ohr: »Doktor, laß mich sterben.« Ich sehe mich um; niemand hat es gehört; die Eltern stehen stumm vorgebeugt und erwarten mein Urteil; die Schwester hat einen Stuhl für meine Handtasche gebracht. Ich öffne die Tasche und suche unter meinen Instrumenten; der Junge tastet immerfort aus dem Bett nach mir hin, um mich an seine Bitte zu erinnern; ich fasse eine Pinzette, prüfe sie im Kerzenlicht und lege sie wieder hin. »Ja,« denke ich lästernd, »in solchen Fällen helfen die Götter, schicken das fehlende Pferd, fügen der Eile wegen noch ein zweites hinzu, spenden zum Übermaß noch den Pferdeknecht –« Jetzt erst fällt mir wieder Rosa ein; was tue ich, wie rette ich sie, wie ziehe ich sie unter diesem Pferdeknecht hervor, zehn Meilen von ihr entfernt, unbeherrschbare Pferde vor meinem Wagen? Diese Pferde, die jetzt die Riemen irgendwie gelockert haben; die Fenster, ich weiß nicht wie, von außen aufstoßen; jedes durch ein Fenster den Kopf stecken und, unbeirrt durch den Aufschrei der Familie, den Kranken betrachten. »Ich fahre gleich wieder zurück,« denke ich, als forderten mich die Pferde zur Reise auf, aber ich dulde es, daß die Schwester, die mich durch die Hitze betäubt glaubt, den Pelz mir abnimmt. Ein Glas Rum wird mir bereitgestellt, der Alte klopft mir auf die Schulter, die Hingabe seines Schatzes rechtfertigt diese Vertraulichkeit. Ich schüttle den Kopf; in dem engen Denkkreis des Alten würde mir übel; nur aus diesem Grunde lehne ich es ab zu trinken. Die Mutter steht am Bett und lockt mich hin; ich folge und lege, während ein Pferd laut zur Zimmerdecke wiehert, den Kopf an die Brust des Jungen, der unter meinem nassen Bart erschauert. Es bestätigt sich, was ich weiß: der Junge ist gesund, ein wenig schlecht durchblutet, von der sorgenden Mutter mit Kaffee durchtränkt, aber gesund und am besten mit einem Stoß aus dem Bett zu treiben. Ich bin kein Weltverbesserer und lasse ihn liegen. Ich bin vom Bezirk angestellt und tue meine Pflicht bis zum Rand, bis dorthin, wo es fast zu viel wird. Schlecht bezahlt, bin ich doch freigebig und hilfsbereit gegenüber den Armen. Noch für Rosa muß ich sorgen, dann mag der Junge recht haben und auch ich will sterben. Was tue ich hier in diesem endlosen Winter! Mein Pferd ist verendet, und da ist niemand im Dorf, der mir seines leiht. Aus dem Schweinestall muß ich mein Gespann ziehen; wären es nicht zufällig Pferde, müßte ich mit Säuen fahren. So ist es. Und ich nicke der Familie zu. Sie wissen nichts davon, und wenn sie es wüßten, würden sie es nicht glauben. Rezepte schreiben ist leicht, aber im übrigen sich mit den Leuten verständigen, ist schwer. Nun, hier wäre also mein Besuch zu Ende, man hat mich wieder einmal unnötig bemüht, daran bin ich gewöhnt, mit Hilfe meiner Nachtglocke martert mich der ganze Bezirk, aber daß ich diesmal auch noch Rosa hingeben mußte, dieses schöne Mädchen, das jahrelang, von mir kaum beachtet, in meinem Hause lebte – dieses Opfer ist zu groß, und ich muß es mir mit Spitzfindigkeiten aushilfsweise in meinem Kopf irgendwie zurechtlegen, um nicht auf diese Familie loszufahren, die mir ja beim besten Willen Rosa nicht zurückgeben kann. Als ich aber meine Handtasche schließe und nach meinem Pelz winke, die Familie beisammensteht, der Vater schnuppernd über dem Rumglas in seiner Hand, die Mutter, von mir wahrscheinlich enttäuscht – ja, was erwartet denn das Volk? – tränenvoll in die Lippen beißend und die Schwester ein schwer blutiges Handtuch schwenkend, bin ich irgendwie bereit, unter Umständen zuzugeben, daß der Junge doch vielleicht krank ist. Ich gehe zu ihm, er lächelt mir entgegen, als brächte ich ihm etwa die allerstärkste Suppe – ach, jetzt wiehern beide Pferde; der Lärm soll wohl, höhern Orts angeordnet, die Untersuchung erleichtern – und nun finde ich: ja, der Junge ist krank. In seiner rechten Seite, in der Hüftengegend hat sich eine handtellergroße Wunde aufgetan. Rosa, in vielen Schattierungen, dunkel in der Tiefe, hellwerdend zu den Rändern, zartkörnig, mit ungleichmäßig sich aufsammelndem Blut, offen wie ein Bergwerk obertags.

So aus der Entfernung. In der Nähe zeigt sich noch eine Erschwerung. Wer kann das ansehen ohne leise zu pfeifen? Würmer, an Stärke und Länge meinem kleinen Finger gleich, rosig aus eigenem und außerdem blutbespritzt, winden sich, im Innern der Wunde festgehalten, mit weißen Köpfchen, mit vielen Beinchen ans Licht. Armer Junge, dir ist nicht zu helfen. Ich habe deine große Wunde aufgefunden; an dieser Blume in deiner Seite gehst du zugrunde. Die Familie ist glücklich, sie sieht mich in Tätigkeit; die Schwester sagt’s der Mutter, die Mutter dem Vater, der Vater einigen Gästen, die auf den Fußspitzen, mit ausgestreckten Armen balancierend, durch den Mondschein der offenen Tür hereinkommen. »Wirst du mich retten?« flüstert schluchzend der Junge, ganz geblendet durch das Leben in seiner Wunde. So sind die Leute in meiner Gegend. Immer das Unmögliche vom Arzt verlangen. Den alten Glauben haben sie verloren; der Pfarrer sitzt zu Hause und zerzupft die Meßgewänder, eines nach dem andern; aber der Arzt soll alles leisten mit seiner zarten chirurgischen Hand. Nun, wie es beliebt: ich habe mich nicht angeboten; verbraucht ihr mich zu heiligen Zwecken, lasse ich auch das mit mir geschehen; was will ich Besseres, alter Landarzt, meines Dienstmädchens beraubt! Und sie kommen, die Familie und die Dorfältesten, und entkleiden mich; ein Schulchor mit dem Lehrer an der Spitze steht vor dem Haus und singt eine äußerst einfache Melodie auf den Text:

»Entkleidet ihn, dann wird er heilen,

Und heilt er nicht, so tötet ihn!

’Sist nur ein Arzt, ’sist nur ein Arzt.«

Dann bin ich entkleidet und sehe, die Finger im Barte, mit geneigtem Kopf die Leute ruhig an. Ich bin durchaus gefaßt und allen überlegen und bleibe es auch, trotzdem es mir nichts hilft, denn jetzt nehmen sie mich beim Kopf und bei den Füßen und tragen mich ins Bett. Zur Mauer, an die Seite der Wunde legen sie mich. Dann gehen alle aus der Stube; die Tür wird zugemacht; der Gesang verstummt; Wolken treten vor den Mond; warm liegt das Bettzeug um mich; schattenhaft schwanken die Pferdeköpfe in den Fensterlöchern. »Weißt du,« höre ich, mir ins Ohr gesagt, »mein Vertrauen zu dir ist sehr gering. Du bist ja auch nur irgendwo abgeschüttelt, kommst nicht auf eigenen Füßen. Statt zu helfen, engst du mir mein Sterbebett ein. Am liebsten kratzte ich dir die Augen aus.«

»Richtig,« sage ich, »es ist eine Schmach. Nun bin ich aber Arzt. Was soll ich tun? Glaube mir, es wird auch mir nicht leicht.« »Mit dieser Entschuldigung soll ich mich begnügen? Ach, ich muß wohl. Immer muß ich mich begnügen. Mit einer schönen Wunde kam ich auf die Welt; das war meine ganze Ausstattung.« »Junger Freund,« sage ich, »dein Fehler ist: du hast keinen Überblick. Ich, der ich schon in allen Krankenstuben, weit und breit, gewesen bin, sage dir: deine Wunde ist so übel nicht. Im spitzen Winkel mit zwei Hieben der Hacke geschaffen. Viele bieten ihre Seite an und hören kaum die Hacke im Forst, geschweige denn, daß sie ihnen näher kommt.« »Ist es wirklich so oder täuschest du mich im Fieber?« »Es ist wirklich so, nimm das Ehrenwort eines Amtsarztes mit hinüber.« Und er nahm’s und wurde still. Aber jetzt war es Zeit, an meine Rettung zu denken. Noch standen treu die Pferde an ihren Plätzen. Kleider, Pelz und Tasche waren schnell zusammengerafft; mit demAnkleiden wollte ich mich nicht aufhalten; beeilten sich die Pferde wie auf der Herfahrt, sprang ich ja gewissermaßen aus diesem Bett in meines.

Gehorsam zog sich ein Pferd vom Fenster zurück; ich warf den Ballen in den Wagen; der Pelz flog zu weit, nur mit einem Ärmel hielt er sich an einem Haken fest. Gut genug. Ich schwang mich aufs Pferd. Die Riemen lose schleifend, ein Pferd kaum mit dem andern verbunden, der Wagen irrend hinterher, der Pelz als letzter im Schnee. »Munter!« sagte ich, aber munter ging’s nicht; langsam wie alte Männer zogen wir durch die Schneewüste; lange klang hinter uns der neue, aber irrtümliche Gesang der Kinder:

»Freuet Euch, Ihr Patienten,

Der Arzt ist Euch ins Bett gelegt!«

Niemals komme ich so nach Hause; meine blühende Praxis ist verloren; ein Nachfolger bestiehlt mich, aber ohne Nutzen, denn er kann mich nicht ersetzen; in meinem Hause wütet der ekle Pferdeknecht; Rosa ist sein Opfer; ich will es nicht ausdenken. Nackt, dem Froste dieses unglückseligsten Zeitalters ausgesetzt, mit irdischem Wagen, unirdischen Pferden, treibe ich mich alter Mann umher. Mein Pelz hängt hinten am Wagen, ich kann ihn aber nicht erreichen, und keiner aus dem beweglichen Gesindel der Patienten rührt den Finger. Betrogen! Betrogen! Einmal dem Fehlläuten der Nachtglocke gefolgt – es ist niemals gutzumachen.

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

Von Kempelen and his Discovery

After the very minute and elaborate paper by Arago, to say nothing of the summary in ‘Silliman’s Journal,’ with the detailed statement just published by Lieutenant Maury, it will not be supposed, of course, that in offering a few hurried remarks in reference to Von Kempelen’s discovery, I have any design to look at the subject in a scientific point of view. My object is simply, in the first place, to say a few words of Von Kempelen himself (with whom, some years ago, I had the honor of a slight personal acquaintance), since every thing which concerns him must necessarily, at this moment, be of interest; and, in the second place, to look in a general way, and speculatively, at the results of the discovery.

It may be as well, however, to premise the cursory observations which I have to offer, by denying, very decidedly, what seems to be a general impression (gleaned, as usual in a case of this kind, from the newspapers), viz.: that this discovery, astounding as it unquestionably is, is unanticipated.

By reference to the ‘Diary of Sir Humphrey Davy’ (Cottle and Munroe, London, pp. 150), it will be seen at pp. 53 and 82, that this illustrious chemist had not only conceived the idea now in question, but had actually made no inconsiderable progress, experimentally, in the very identical analysis now so triumphantly brought to an issue by Von Kempelen, who although he makes not the slightest allusion to it, is, without doubt (I say it unhesitatingly, and can prove it, if required), indebted to the ‘Diary’ for at least the first hint of his own undertaking.

The paragraph from the ‘Courier and Enquirer,’ which is now going the rounds of the press, and which purports to claim the invention for a Mr. Kissam, of Brunswick, Maine, appears to me, I confess, a little apocryphal, for several reasons; although there is nothing either impossible or very improbable in the statement made. I need not go into details. My opinion of the paragraph is founded principally upon its manner. It does not look true. Persons who are narrating facts, are seldom so particular as Mr. Kissam seems to be, about day and date and precise location. Besides, if Mr. Kissam actually did come upon the discovery he says he did, at the period designated — nearly eight years ago — how happens it that he took no steps, on the instant, to reap the immense benefits which the merest bumpkin must have known would have resulted to him individually, if not to the world at large, from the discovery? It seems to me quite incredible that any man of common understanding could have discovered what Mr. Kissam says he did, and yet have subsequently acted so like a baby — so like an owl — as Mr. Kissam admits that he did. By-the-way, who is Mr. Kissam? and is not the whole paragraph in the ‘Courier and Enquirer’ a fabrication got up to ‘make a talk’? It must be confessed that it has an amazingly moon-hoaxy-air. Very little dependence is to be placed upon it, in my humble opinion; and if I were not well aware, from experience, how very easily men of science are mystified, on points out of their usual range of inquiry, I should be profoundly astonished at finding so eminent a chemist as Professor Draper, discussing Mr. Kissam’s (or is it Mr. Quizzem’s?) pretensions to the discovery, in so serious a tone.

But to return to the ‘Diary’ of Sir Humphrey Davy. This pamphlet was not designed for the public eye, even upon the decease of the writer, as any person at all conversant with authorship may satisfy himself at once by the slightest inspection of the style. At page 13, for example, near the middle, we read, in reference to his researches about the protoxide of azote: ‘In less than half a minute the respiration being continued, diminished gradually and were succeeded by analogous to gentle pressure on all the muscles.’ That the respiration was not ‘diminished,’ is not only clear by the subsequent context, but by the use of the plural, ‘were.’ The sentence, no doubt, was thus intended: ‘In less than half a minute, the respiration [being continued, these feelings] diminished gradually, and were succeeded by [a sensation] analogous to gentle pressure on all the muscles.’ A hundred similar instances go to show that the MS. so inconsiderately published, was merely a rough note-book, meant only for the writer’s own eye, but an inspection of the pamphlet will convince almost any thinking person of the truth of my suggestion. The fact is, Sir Humphrey Davy was about the last man in the world to commit himself on scientific topics. Not only had he a more than ordinary dislike to quackery, but he was morbidly afraid of appearing empirical; so that, however fully he might have been convinced that he was on the right track in the matter now in question, he would never have spoken out, until he had every thing ready for the most practical demonstration. I verily believe that his last moments would have been rendered wretched, could he have suspected that his wishes in regard to burning this ‘Diary’ (full of crude speculations) would have been unattended to; as, it seems, they were. I say ‘his wishes,’ for that he meant to include this note-book among the miscellaneous papers directed ‘to be burnt,’ I think there can be no manner of doubt. Whether it escaped the flames by good fortune or by bad, yet remains to be seen. That the passages quoted above, with the other similar ones referred to, gave Von Kempelen the hint, I do not in the slightest degree question; but I repeat, it yet remains to be seen whether this momentous discovery itself (momentous under any circumstances) will be of service or disservice to mankind at large. That Von Kempelen and his immediate friends will reap a rich harvest, it would be folly to doubt for a moment. They will scarcely be so weak as not to ‘realize,’ in time, by large purchases of houses and land, with other property of intrinsic value.

In the brief account of Von Kempelen which appeared in the ‘Home Journal,’ and has since been extensively copied, several misapprehensions of the German original seem to have been made by the translator, who professes to have taken the passage from a late number of the Presburg ‘Schnellpost.’ ‘Viele’ has evidently been misconceived (as it often is), and what the translator renders by ‘sorrows,’ is probably ‘lieden,’ which, in its true version, ‘sufferings,’ would give a totally different complexion to the whole account; but, of course, much of this is merely guess, on my part.

Von Kempelen, however, is by no means ‘a misanthrope,’ in appearance, at least, whatever he may be in fact. My acquaintance with him was casual altogether; and I am scarcely warranted in saying that I know him at all; but to have seen and conversed with a man of so prodigious a notoriety as he has attained, or will attain in a few days, is not a small matter, as times go.

‘The Literary World’ speaks of him, confidently, as a native of Presburg (misled, perhaps, by the account in ‘The Home Journal’) but I am pleased in being able to state positively, since I have it from his own lips, that he was born in Utica, in the State of New York, although both his parents, I believe, are of Presburg descent. The family is connected, in some way, with Maelzel, of Automaton-chess-player memory. In person, he is short and stout, with large, fat, blue eyes, sandy hair and whiskers, a wide but pleasing mouth, fine teeth, and I think a Roman nose. There is some defect in one of his feet. His address is frank, and his whole manner noticeable for bonhomie. Altogether, he looks, speaks, and acts as little like ‘a misanthrope’ as any man I ever saw. We were fellow-sojouners for a week about six years ago, at Earl’s Hotel, in Providence, Rhode Island; and I presume that I conversed with him, at various times, for some three or four hours altogether. His principal topics were those of the day, and nothing that fell from him led me to suspect his scientific attainments. He left the hotel before me, intending to go to New York, and thence to Bremen; it was in the latter city that his great discovery was first made public; or, rather, it was there that he was first suspected of having made it. This is about all that I personally know of the now immortal Von Kempelen; but I have thought that even these few details would have interest for the public.

There can be little question that most of the marvellous rumors afloat about this affair are pure inventions, entitled to about as much credit as the story of Aladdin’s lamp; and yet, in a case of this kind, as in the case of the discoveries in California, it is clear that the truth may be stranger than fiction. The following anecdote, at least, is so well authenticated, that we may receive it implicitly.

Von Kempelen had never been even tolerably well off during his residence at Bremen; and often, it was well known, he had been put to extreme shifts in order to raise trifling sums. When the great excitement occurred about the forgery on the house of Gutsmuth & Co., suspicion was directed toward Von Kempelen, on account of his having purchased a considerable property in Gasperitch Lane, and his refusing, when questioned, to explain how he became possessed of the purchase money. He was at length arrested, but nothing decisive appearing against him, was in the end set at liberty. The police, however, kept a strict watch upon his movements, and thus discovered that he left home frequently, taking always the same road, and invariably giving his watchers the slip in the neighborhood of that labyrinth of narrow and crooked passages known by the flash name of the ‘Dondergat.’ Finally, by dint of great perseverance, they traced him to a garret in an old house of seven stories, in an alley called Flatzplatz, — and, coming upon him suddenly, found him, as they imagined, in the midst of his counterfeiting operations. His agitation is represented as so excessive that the officers had not the slightest doubt of his guilt. After hand-cuffing him, they searched his room, or rather rooms, for it appears he occupied all the mansarde.

Opening into the garret where they caught him, was a closet, ten feet by eight, fitted up with some chemical apparatus, of which the object has not yet been ascertained. In one corner of the closet was a very small furnace, with a glowing fire in it, and on the fire a kind of duplicate crucible — two crucibles connected by a tube. One of these crucibles was nearly full of lead in a state of fusion, but not reaching up to the aperture of the tube, which was close to the brim. The other crucible had some liquid in it, which, as the officers entered, seemed to be furiously dissipating in vapor. They relate that, on finding himself taken, Kempelen seized the crucibles with both hands (which were encased in gloves that afterwards turned out to be asbestic), and threw the contents on the tiled floor. It was now that they hand-cuffed him; and before proceeding to ransack the premises they searched his person, but nothing unusual was found about him, excepting a paper parcel, in his coat-pocket, containing what was afterward ascertained to be a mixture of antimony and some unknown substance, in nearly, but not quite, equal proportions. All attempts at analyzing the unknown substance have, so far, failed, but that it will ultimately be analyzed, is not to be doubted.

Passing out of the closet with their prisoner, the officers went through a sort of ante-chamber, in which nothing material was found, to the chemist’s sleeping-room. They here rummaged some drawers and boxes, but discovered only a few papers, of no importance, and some good coin, silver and gold. At length, looking under the bed, they saw a large, common hair trunk, without hinges, hasp, or lock, and with the top lying carelessly across the bottom portion. Upon attempting to draw this trunk out from under the bed, they found that, with their united strength (there were three of them, all powerful men), they ‘could not stir it one inch.’ Much astonished at this, one of them crawled under the bed, and looking into the trunk, said:

‘No wonder we couldn’t move it — why it’s full to the brim of old bits of brass!’ Putting his feet, now, against the wall so as to get a good purchase, and pushing with all his force, while his companions pulled with an theirs, the trunk, with much difficulty, was slid out from under the bed, and its contents examined. The supposed brass with which it was filled was all in small, smooth pieces, varying from the size of a pea to that of a dollar; but the pieces were irregular in shape, although more or less flat-looking, upon the whole, ‘very much as lead looks when thrown upon the ground in a molten state, and there suffered to grow cool.’ Now, not one of these officers for a moment suspected this metal to be any thing but brass. The idea of its being gold never entered their brains, of course; how could such a wild fancy have entered it? And their astonishment may be well conceived, when the next day it became known, all over Bremen, that the ‘lot of brass’ which they had carted so contemptuously to the police office, without putting themselves to the trouble of pocketing the smallest scrap, was not only gold — real gold — but gold far finer than any employed in coinage-gold, in fact, absolutely pure, virgin, without the slightest appreciable alloy.

I need not go over the details of Von Kempelen’s confession (as far as it went) and release, for these are familiar to the public. That he has actually realized, in spirit and in effect, if not to the letter, the old chimaera of the philosopher’s stone, no sane person is at liberty to doubt. The opinions of Arago are, of course, entitled to the greatest consideration; but he is by no means infallible; and what he says of bismuth, in his report to the Academy, must be taken cum grano salis. The simple truth is, that up to this period all analysis has failed; and until Von Kempelen chooses to let us have the key to his own published enigma, it is more than probable that the matter will remain, for years, in statu quo. All that as yet can fairly be said to be known is, that ‘Pure gold can be made at will, and very readily from lead in connection with certain other substances, in kind and in proportions, unknown.’

Speculation, of course, is busy as to the immediate and ultimate results of this discovery — a discovery which few thinking persons will hesitate in referring to an increased interest in the matter of gold generally, by the late developments in California; and this reflection brings us inevitably to another — the exceeding inopportuneness of Von Kempelen’s analysis. If many were prevented from adventuring to California, by the mere apprehension that gold would so materially diminish in value, on account of its plentifulness in the mines there, as to render the speculation of going so far in search of it a doubtful one — what impression will be wrought now, upon the minds of those about to emigrate, and especially upon the minds of those actually in the mineral region, by the announcement of this astounding discovery of Von Kempelen? a discovery which declares, in so many words, that beyond its intrinsic worth for manufacturing purposes (whatever that worth may be), gold now is, or at least soon will be (for it cannot be supposed that Von Kempelen can long retain his secret), of no greater value than lead, and of far inferior value to silver. It is, indeed, exceedingly difficult to speculate prospectively upon the consequences of the discovery, but one thing may be positively maintained — that the announcement of the discovery six months ago would have had material influence in regard to the settlement of California.

In Europe, as yet, the most noticeable results have been a rise of two hundred per cent. in the price of lead, and nearly twenty-five per cent. that of silver.

Edgar Allan Poe: Von Kempelen and his Discovery

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Chess in literature, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

Ambrose Bierce

(1842-1914?)

The Key Note

I dreamed I was dreaming one morn as I lay

In a garden with flowers teeming.

On an island I lay in a mystical bay,

In the dream that I dreamed I was dreaming.

The ghost of a scent–had it followed me there

From the place where I truly was resting?

It filled like an anthem the aisles of the air,

The presence of roses attesting.

Yet I thought in the dream that I dreamed I dreamed

That the place was all barren of roses–

That it only seemed; and the place, I deemed,

Was the Isle of Bewildered Noses.

Full many a seaman had testified

How all who sailed near were enchanted,

And landed to search (and in searching died)

For the roses the Sirens had planted.

For the Sirens were dead, and the billows boomed

In the stead of their singing forever;

But the roses bloomed on the graves of the doomed,

Though man had discovered them never.

I thought in my dream ’twas an idle tale,

A delusion that mariners cherished–

That the fragrance loading the conscious gale

Was the ghost of a rose long perished.

I said, “I will fly from this island of woes.”

And acting on that decision,

By that odor of rose I was led by the nose,

For ’twas truly, ah! truly, Elysian.

I ran, in my madness, to seek out the source

Of the redolent river–directed

By some supernatural, sinister force

To a forest, dark, haunted, infected.

And still as I threaded (’twas all in the dream

That I dreamed I was dreaming) each turning

There were many a scream and a sudden gleam

Of eyes all uncannily burning!

The leaves were all wet with a horrible dew

That mirrored the red moon’s crescent,

And all shapes were fringed with a ghostly blue,

Dim, wavering, phosphorescent.

But the fragrance divine, coming strong and free,

Led me on, though my blood was clotting,

Till–ah, joy!–I could see, on the limbs of a tree,

Mine enemies hanging and rotting!

.jpg)

Ambrose Bierce poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bierce, Ambrose

.jpg)

P. A. d e G é n e s t e t

(1829 – 1861)

O n v e r m o e i d

Des drijvers geweldige roede

Jaagt rustloos ons voort op ons pad:

Wij loopen en worden wel moede,

Wij wandlen en worden wel mat.

De hitte des daags drukt ons neder

En donker daalt menige nacht;

Wij gaan – en wij komen niet weder,

Waar ’t luchtje zoo mild was en zacht;

Waar lieflijk de levensstroom ruischte,

En vroolijk uit bloemhof en dal

De wildzang der vogelen bruiste

En ’t hart sloeg met jubelgeschal!

Hoe kwijnden en bloemen en zonnen!

Veel trouwe gezichten zijn heen:

De reis, zoo gezellig begonnen,

Werd somber en eenzaam meteen.

Wat vloodt ge ons, gij lieve, gij goede?

Keert weder ten steun op ons pad

Wij loopen en worden zoo moede,

Wij wandlen en worden zoo mat!

Zij keeren niet weder, de dooden,

En ’t omzien wekt ijdele smart

Wat staat gij? – de rust is verboden!

Geen ruste, al bezweek ook uw bart.

Noch omzien, noch schreien, noch klagen

Vertroost ons, vernieuwt ons de kracht….

Mijn ziel, laat een psalmtoon u dragen,

En klink’, o mijn harpe, te nacht:

Wij slaan naar de bergen onze oogen,

De hulpe zal komen van God:

’t Is Hij, die uw tranen zal drogen,

U leidt op den weg van uw lot!

Vaartwel dan, gij lachende dreven!

En vredige dalen, gegroet!

Berg-op gaat de weg van ons leven,

Wij stijgen met manlijken moed.

Al buigen, in treurig gepeize,

Wel vaak onze zielen zich neêr,

De korte verdrukking der reize

Vindt ook haar vergoedinge weer.

Wij kennen en – kussen de roede,

Die rustloos ons drijft op ons pad,

Wij loopen en – worden wij moede –

Wij zoeken ook de eeuwige Stad!

Geen rusteloos zwerven en smachten

Is ’t leven: een Doel licht ons voor;

En worstlende winnen wij krachten,

En dwalende vinden wij ’t spoor!

Een Machtige steunt ons en schraagt ons,

Wij struiklen : Hij richt onzen voet

Wij vreezen, wij vallen…. Hij draagt ons

Getrouw over bergen en vloed!

Zoo vreest niet! laat rijzen uw psalmen,

Laat vroolijk langs afgrond en rots

Het moedige reislied weergalmen,

Het reislied der kinderen Gods.

Wij wachten met dankenden hoofde

Uw heil en uw waarheid, o Heer!

En wat het verleden ons roofde,

Geeft schooner de toekomst ons weer.

Steek’ de zon, daal’ de nacht, Gij Algoede!

Zijt schaduw en licht op ons pad; –

Wij loopen en worden niet moede,

Wij wandlen en worden niet mat.

.jpg)

P.A. de Génestet gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Génestet, P.A. de

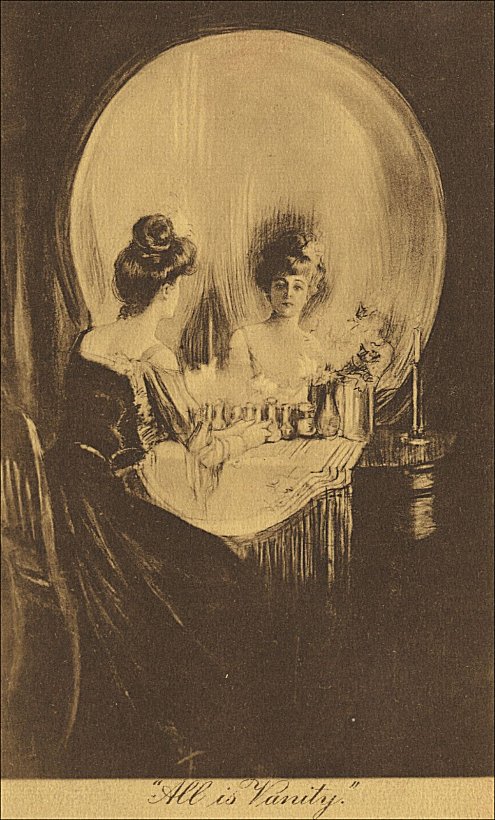

All is Vanity

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Camera Obscura, Invisible poetry

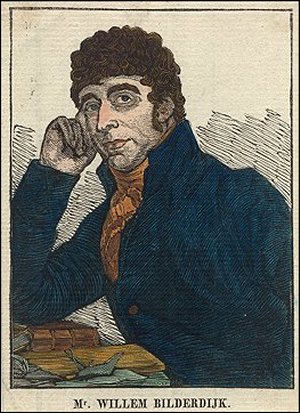

Willem Bilderdijk

(1756-1831)

Doodsgedachten

Ja, nog leef ik, lieve vrinden;

Maar die morgen wederkomt

Als het middagklokjen bromt,

Zal my die nog levend vinden?

Of — mijn kaarsjen uitgedompt?

Ja, ik was en ben nog heden

Onbelemmerd van gezicht;

De ingewanden doen hun plicht;

’k Ben nog onberoerd van leden;

Maar…wie kent het morgenlicht?

’k Heb reeds van mijn kindsche jaren

Op geen heden ooit gebouwd;

’s Menschen adem nooit betrouwd,

Maar als schuim van waterbaren,

Als een zeepnat-bel beschouwd.

Nimmer wilde ik voor het morgen

Met een voorbaat van bestuur,

Nimmer voor het avonduur

Van d’ onzeekren leeftijd zorgen,

Of is ’t had in vasten huur.

Elken oogwenk zag ik ’t sterven

(Reisbegeerig) voor my staan.

Nooit een ochtend glom my aan,

Nooit een nacht kon ’t veld ontverven,

Of ik dacht naar ’t graf te gaan.

Dag aan dag verlengde een leven,

Ieder tijdstip als gesloopt;

Telkens weder aangeknoopt,

Telkens als op nieuw gegeven;

Altijd even onverhoopt.

Dankbaar mocht ik ’s steeds ontfangen;

Uit de hand die alles schenkt,

Met vernieuwde kracht gedrenkt; —

Zonder weêrzin of verlangen; —

Altijd door den Dood gewenkt. —

Vijf- en twintigduizend dagen

vlogen over my voorby

Met den doodsbaar aan mijn zij’;

In gestaâge wisslvlagen

Van een stormend wareldtij’.

En, nu zoudt ge my verbieden

By des levens laatsten rook

Uit te kijken, naar het spook,

Dat nooit snelheid kon ontvlieden,

Dat nooit schranderheid ontdook!

Neen! ik wensch hem niet te ontloopen,

’k Geef hem met een blij gemoed

d’ Ongeveinsden welkomgroet;

’k Zet de deur hem willig open

Tegen dat hy komen moet.

Draalt hy nog —; ik ben te vrede,

Maar verbei hem dag en nacht

Als een vriend waarop ik wacht;

En, neemt hy dit rompjen mede,

Gaarne geeft ik ’t hem voor vracht.

’t Is toch nietig van stofsaadje,

En ik voel, het past my slecht;

Hier is ’t scheef, en daer niet recht:

’k gun hem al die reisbagaadje,

Waar ik geen belang aan hecht.

Want, MY veilig overvaren,

Ja, dat zal die Veerman wel:

Daar toe heeft hy streng bevel.

Reeds voor duizend van jaren

Had Hy ’t briefjen van bestel.

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Bilderdijk, Willem

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 55

Ik weet niet hoe ‘t komt maar

Ein Märchen aus alten Zeiten

Das will mir nicht aus dem Sinn.

En ‘t klinkt als:

O, what a noble mind is here overthrown!

Zo is er veel in de Hamlet wat me als muziek door de ziel ruist.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

T H E S O N N E T S

27

Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed,

The dear respose for limbs with travel tired,

But then begins a journey in my head

To work my mind, when body’s work’s expired.

For then my thoughts (from far where I abide)

Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee,

And keep my drooping eyelids open wide,

Looking on darkness which the blind do see.

Save that my soul’s imaginary sight

Presents thy shadow to my sightless view,

Which like a jewel (hung in ghastly night)

Makes black night beauteous, and her old face new.

Lo thus by day my limbs, by night my mind,

For thee, and for my self, no quiet find.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Marc Ouwerling:

Luchtduel & andere notities

In Luchtduel & andere notities van Marc Ouwerling zijn gedichten opgenomen over sport, oorlog, vriendschappen, natuur, reisimpressies en een, letterlijk, gevecht om lucht. Voortdurend probeert hij door middel van een ogenschijnlijk lichte toets de verschillende thema’s in een soort van evenwicht te houden.

Deze gedichten, door hem hardnekkig ‘notities’ genoemd, blinken uit in hun vorm en inhoud. Marc Ouwerling (1954) studeerde Nederlands in Tilburg en Leiden, en publiceerde eerder de bundels De Slaap van Sisera en De gemorste Tijd en, samen met fotograaf Rutger Lokin, het fotoboek De Stilte en de Echo, over de Duitse vernietigingskampen in Polen in de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Als reiziger prefereert hij de rol van de zwijgzame passant, altijd op doorreis, die het beschouwde fotografeert, maar er nooit deel van uitmaakt. Hij is als tekstschrijver en conceptman werkzaam in de reclamebranche, schrijft (sport-) columns en korte verhalen.

Marc Ouwerling: Luchtduel & andere notities

Uitgeverij Van Kemenade –Prijs € 17,50

ISBN 9789071376399

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Literary Events

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Anton K. photos: Nature Morte (1)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, Dutch Landscapes

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature