Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

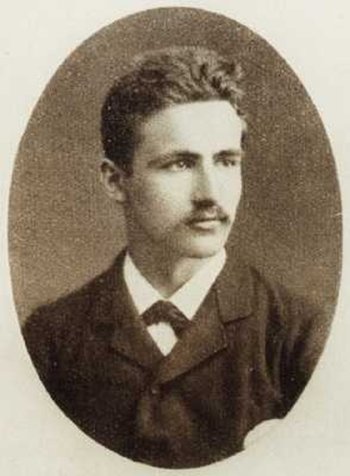

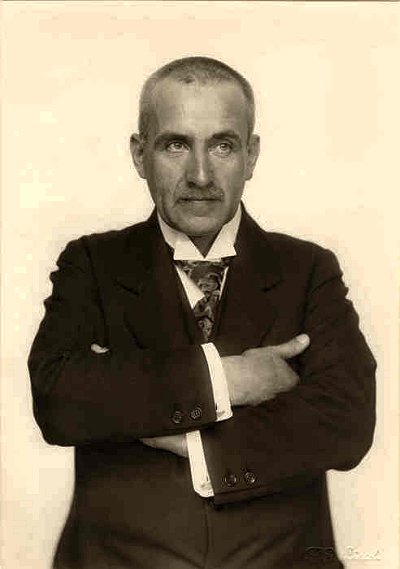

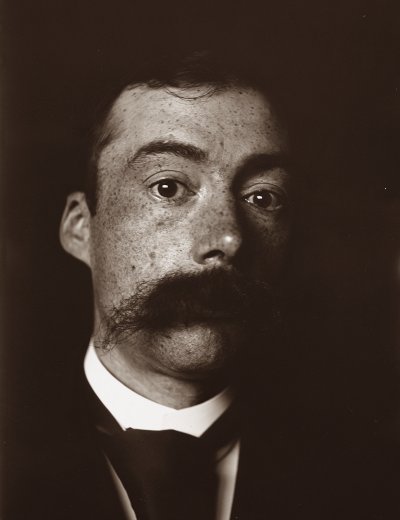

Frank Wedekind

(1864-1918)

An Elka

Elka, länger kann ich mich nicht halten,

Meine Sinne toben allzu wild;

Und in allen weiblichen Gestalten

Seh ich schon dein Götterbild!

Auch im Traum bist du mir schon erschienen,

Dich entkleidend; oh wie ward mir da!

Schwindlig ward mir hinter den Gardinen,

Als ich deinen Busen sah.

Meine beiden Knie wurden brüchig,

Von der Stirne triefte mir das Fett.

Als das Hemd du abgetan, da schlich ich

Wonneschauernd an dein Bett.

Mach, daß dieser Traum sich bald erfülle;

Mach, erhabne Königin,

Daß bei dir ich vor Behagen brülle,

Nicht vor Wut, weil ich dir ferne bin.

Frank Wedekind poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Frank Wedekind

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XV

SPELEN IN HET WOUD VAN TUBBS

Ik weet niet meer waarover ik die nacht droomde. Het moet een fijne droom zijn geweest, want toen ik ‘s morgens wakker werd, was ik blij. Ik liet niet merken dat ik wakker was. Integendeel. Ik bleef stil liggen en luisterde naar het kloppen van Alices hart, want ik lag nog steeds met mijn hoofd op haar borst. Ik voelde haar adem. Ik mocht me niet bewegen. Dan zou ik de marmot wakker maken. Die lag stil tussen mijn benen en zou het niet fijn vinden wakker gemaakt te worden. Overigens ben ik er nooit achtergekomen of de marmot ooit echt sliep. Hij hield wel zijn ogen dicht, maar hij voelde het als je naar hem keek.

In de wagen lag Cherubijn te ronken. Ik zou graag even zijn gaan kijken of zijn houten poot langs het bed naar beneden hing en of zijn kop scheef op het kussen lag en of zijn adem weer naar bedorven fruit rook.

Als ik mijn ogen opende en verder stil bleef liggen, kon ik door een spleet in de dekenzak naar buiten kijken. De wei dampte alsof er onder werd gestookt. De koeien vraten uit alle macht. De melker was bezig de draad om de wei aan te spannen. Die hing slap, in grote bogen, net als hoogspanningsdraden bij warm weer.

Over de weg liepen mensen uit Oeroe die wat door de morgen wilden wandelen. De morgen was hier, waar alleen de wei was en onze wagen, een witte wolk waar je goed doorheen kon kijken.

Sommige wandelaars bleven staan, keken naar de ademende slaapzak, maar konden niet zien wie erin lagen. Ze liepen verder, kwamen terug om opnieuw te blijven staan en naar de ademende dekenzak te kijken. Ze zochten de marmot. Ze waren verbaasd toen de dekenzak openging en Alice en ik onze hoofden naar buiten staken. Tegen elkaar zeiden ze: ‘Kijk, het meisje uit de zweef dat je niet mocht zoenen.’ Daar hadden ze toch wel respect voor. Toen de marmot langs mijn lijf naar buiten liep, gooiden ze ons geldstukjes toe.

Alice lachte. De mensen werden er gelukkiger door. Wat wilden ze nog meer. De morgen hadden ze al. Nu Alice tegen hen lachte, moesten ze genoeg energie hebben om een hele dag lang het leven vol te houden.

We kwamen uit de dekenzak. Alices rok was gekreukt. Ze streek er langs met haar strijkijzerhandjes. Weg waren de kreukels. Haar rok was weer even fleurig als de vorige dag. De mensen van Oeroe liepen door. De anderen die langs kwamen bleven niet meer staan. Naar rondlopende mensen kijk je niet. Wel naar mensen die liggen te slapen in een dekenzak en die je niet kunt zien. Dan moet je wel blijven staan om te zien wie er in de zak liggen en of je ‘goedenmorgen’ kunt zeggen. Zo waren de mensen van Oeroe. Bij al hun melancholie, veroorzaakt door de waterader die onder hun dorp liep, bleven ze toch vriendelijk. En waarom ook niet? Ze vierden de eerste naoorlogse kermis. Ook de kermissen hadden in de oorlog stilgelegen. Waarom weet ik niet. Je kon toch goed kermis vieren, ook al vocht men ergens aan het front? Of had het ook wat met het vaderland en de eigen doden te maken?

We hadden weer geld genoeg om eten te kopen. Dat hadden we aan de marmot te danken. De marmot die zonder het te weten de kost voor ons verdiende door over mijn lijf uit de slaapzak te kruipen om naar de mensen te kijken. Zo gemakkelijk heb ik de kost nooit meer verdiend. Later was ik niet meer tevreden met een stuk brood ‘s morgens en gebakken aardappelen ‘s avonds.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

4

Turn the handle; I have turned it. I have kept my word: to the end. But the vengeance that I sought to accomplish upon the obligation imposed on me, as the slave of a machine, to serve up life to my machine as food, life has chosen to turn back upon me. Very good. No one henceforward can deny that I have now arrived at perfection.

As an operator I am now, truly, perfect.

About a month after the appalling disaster which is still being discussed everywhere, I bring these notes to an end.

A pen and a sheet of paper: there is no other way left to me now in which I can communicate with my fellow-men. I have lost my voice; I am dumb now for ever. Elsewhere in these notes I have written: “I suffer from this silence of mine, into which everyone comes, as into a place of certain hospitality. ‘I should like now my silence to close round me altogether’.” Well, it has closed round me. I could not be better qualified to act as the servant of a machine.

But I must tell you the whole story, as it happened.

The wretched fellow went, next morning, to Borgalli to complain forcibly of the ridiculous figure which, as he was informed, Polacco intended to make him cut with these precautions.

He insisted at all costs that the orders should be cancelled, offering to give them all a specimen, if they needed it, of his well-known skill as a marksman. Polacco excused himself to Borgalli, saying that he had taken these measures not from any want of confidence in Nuti’s courage or sureness of eye, but from prudence, knowing Nuti to be extremely nervous, as for that matter he was shewing himself to be at that moment by uttering this excited protest, instead of the grateful, friendly thanks which Polacco had a right to expect from him.

“Besides,” he unfortunately added, pointing to me, “you see, Commendatore, there’s Gubbio here too, who has to go into the cage….”

The poor wretch looked at me with such contempt that I immediately turned upon Polacco, exclaiming:

“No, no, my dear fellow! Don’t bother about me, please! You know very well that I shall go on quietly turning my handle, even if I see this gentleman in the jaws and claws of the beast!”

There was a laugh from the actors who had gathered round to listen; whereupon Polacco shrugged his shoulders and gave way, or pretended to give way. Fortunately for me, as I learned afterwards, he gave secret instructions to Fantappiè and one of the others to conceal their weapons and to stand ready for any emergency. Nuti went off to his dressing-room to put on his sporting clothes; I went to the Negative Department to prepare my machine for its meal. Fortunately for the company, I drew a much larger supply of film than would be required, to judge approximately by the length of the scene. When I returned to the crowded lawn, by the side of the enormous cage, set with a forest scene, the other cage, with the tiger inside it, had already been carried out and placed so that the two cages opened into one another. It only remained to pull up the door of the smaller cage.

Any number of actors from the four companies had assembled on either side, close to the cage, so that they could see between the tree trunks and branches that concealed its bars. I hoped for a moment that the Nestoroff, having secured her object, would at least have had the prudence not to come. But there she was, alas!

She stood apart from the crowd, a little way off, with Carlo Ferro, dressed in bright green, and was smiling as she repeatedly nodded her head in agreement with what Ferro was saying to her, albeit from the grim attitude in which he stood by her side it seemed evident that such a smile was not the appropriate answer to his words. But it was meant for the others, that smile, for all of us who stood watching her, and was also for me, a brighter smile, when I fixed my gaze on her; and it said to me once again that she was not afraid of anything, because the greatest possible evil for her I already knew: she had it by her side–there it was–Ferro; he was her punishment, and to the very end she I was determined, with that smile, to taste its, full flavour in the coarse words which he was probably addressing to her at that moment.

Taking my eyes from her, I sought those of Nuti. They were clouded. Evidently he too had caught sight of the Nestoroff there in the distance; but he chose to pretend that he had not. His face had grown stiff. He made an effort to smile, but smiled with his lips alone, a faint, nervous smile, at what some one was saying to him. With his black velvet cap on his head, with its long peak, his red coat, a huntsman’s brass horn slung over his shoulder, his white buckskin breeches fitting close to his thighs; booted and spurred, rifle in hand: he was ready.

The door of the big cage, through which ha and I were to enter, was opened from outside; to help us to climb in, two stage hands placed a pair of steps beneath it. He entered the cage first, then I. While I was setting up my machine on its tripod, which had been handed to me through the door of the cage, I noticed that Nuti first of all knelt down on the spot marked out for him, then rose and went across to thrust apart the boughs at one side of the cage, as though he were making a loophole there. I alone was in a position to ask him:

“Why?”

But the state of feeling that had grown up between us did not allow of our exchanging a single word at this stage. His action might therefore have been interpreted by me in several ways, which would have left me uncertain at a moment when the most absolute and precise certainty was essential. And then it was just as though Nuti had not moved at all; not only did I not think any more about his action, it was exactly as though I had not even noticed it.

He took his stand on the spot marked out for him, raising his rifle; I gave the signal:

“Ready.”

We heard from the other cage the sound of the door being pulled up. Polacco, perhaps seeing the animal begin to move towards the open door, shouted amid the silence:

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

And I began to turn the handle, with my eyes on the tree trunks in the background, through which the animal’s head was now protruding, lowered, as though peering out to explore the country; I saw that head slowly drawn back, the two forepaws remain firm, close together, and the hindlegs gradually, silently gather strength and the back rise in an arch in readiness for the spring. My hand was impassively keeping the time that I had set for its movement, faster, slower, dead slow, as though my will had flowed down–firm, lucid, inflexible–into my wrist, and from there had assumed entire control, leaving my brain free to think, my heart to feel; so that my hand continued to obey even when with a pang of terror I saw Nuti take his aim from the beast and slowly turn the muzzle of his rifle towards the spot where a moment earlier he had opened a loophole among the boughs, and fire, and the tiger immediately spring upon him and become merged with him, before my eyes, in a horrible writhing mass. Drowning the most deafening shouts that came from all the actors outside the cage as they ran instinctively towards the Nestoroff who had fallen at the shot, drowning the cries of Carlo Ferro, I heard there in the cage the deep growl of the beast and the horrible gasp of the man as he lay helpless in its fangs, in its claws, which were tearing his throat and chest; I heard, I heard, I kept on hearing above that growl, above that gasp, the continuous ticking of the machine, the handle of which my hand, alone, of its own accord, still kept on turning; and I waited for the beast to spring next upon me, having brought him down; and the moments of waiting seemed to me an eternity, and it seemed to me that throughout eternity I had been counting them, as I turned, still turned the handle, powerless to stop, when finally an arm was thrust in between the bars, carrying a revolver, and fired a shot point blank into the tiger’s ear over the mangled corpse of Nuti; and I was pulled back and dragged from the cage with the handle of the machine so tightly clasped in my fist that it was impossible at first to wrest it from me. I uttered no groan, no cry: my voice, from terror, had perished in my throat for ever.

Well, I have rendered the firm a service from which they will reap a fortune. As soon as I was able, I explained to the people who gathered round me terror-struck, first of all by signs, then in writing, that they were to take good care of the machine, which had been wrenched from my hand: that machine had in its maw the life of a man; I had given it that life to eat to the very last, until the moment when that arm had been thrust in to kill the tiger. There was a fortune to be extracted from this film, what with the enormous publicity and the morbid curiosity which the sordid atrocity of the drama of that slaughtered couple would everywhere arouse.

Ah, that it would fall to my lot to feed literally on the life of a man one of the many machines invented by man for his pastime, I could never have guessed. The life which this machine has devoured was naturally no more than it could be in a time like the present, in an age of machines; a production stupid in one aspect, mad in another, inevitably, and in the former more, in the latter rather less stamped with a brand of vulgarity.

I have found salvation, I alone, in my silence, with my silence, which has made me thus–according to the standard of the times–perfect. My friend Simone Pau will not understand this, more and more determined to drown himself in ‘superfluity’, the perpetual inmate of a Casual Shelter. I have already secured a life of ease with the compensation which the firm has given me for the service I have rendered it, and I shall soon be rich with the royalties which have been assigned to me from the hire of the monstrous film. It is true that I shall not know what to do with these riches; but I shall not reveal my embarrassment to anyone; least of all to Simone Pau, who comes every day to shake me, to abuse me, in the hope of forcing me out of this inanimate silence, which makes him furious. He would like to see me weep, would like me at least with my eyes to shew distress or anger; to make him understand by signs that I agree with him, that I too believe that life is there, in that ‘superfluity’ of his. I do not move an eyelid; I sit gazing at him, rigid, motionless, until he flies from the house in a rage. Poor Cavalena, from anoher angle, is studying on my behalf textbooks of nervous pathology, suggests injections and electric batteries, hovers round me to persuade me to agree to a surgical operation on my vocal chords; and Signorina Luisetta, penitent, heartbroken at my calamity, in which she chooses to detect an element of heroism, timidly lets me see now that she would like to hear issue, if not from my lips, at any rate from my heart a “yes” for herself.

No, thank you. Thanks to everybody. I have had enough. I prefer to remain like this. The times are what they are; life is what it is; and in the sense that I give to my profession, I intend to go on as I am–alone, mute and impassive–being the operator.

Is the stage set?

“Are you ready? Shoot….”

THE END

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

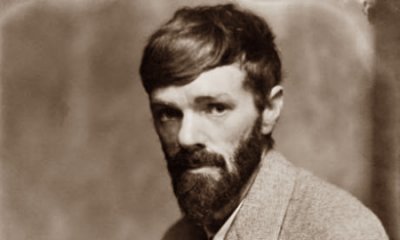

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Trees in the Garden

Ah in the thunder air

how still the trees are!

And the lime-tree, lovely and tall, every leaf silent

hardly looses even a last breath of perfume.

And the ghostly, creamy coloured little tree of leaves

white, ivory white among the rambling greens

how evanescent, variegated elder, she hesitates on the green grass

as if, in another moment, she would disappear

with all her grace of foam!

And the larch that is only a column, it goes up too tall to see:

and the balsam-pines that are blue with the grey-blue blueness of

things from the sea,

and the young copper beech, its leaves red-rosy at the ends

how still they are together, they stand so still

in the thunder air, all strangers to one another

as the green grass glows upwards, strangers in the silent garden.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

3

And now, God willing, we have reached the end. Nothing remains now save the final picture of the killing of the tiger.

The tiger: yes, I prefer, if I must be distressed, to be distressed over her; and I go to pay her a visit, standing for the last time in front of her cage.

She has grown used to seeing me, the beautiful creature, and does not stir. Only she wrinkles her brows a little, annoyed; but she endures the sight of me as she endures the burden of this sunlit silence, lying heavy round about her, which here in the cage is impregnated with a strong bestial odour. The sunlight enters the cage and she shuts her eyes, perhaps to dream, perhaps so as not to see descending ‘upon her the stripes of shadow cast by the iron bars. Ah, she must be tremendously bored with life also; bored, too, with my pity for her; and I believe that to make it cease, with a fit reward, she would gladly devour me. This desire, which she realises that the bars prevent her from satisfying, makes her heave a deep sigh; and since she is lying outstretched, her languid head drooping on one paw, I see, when she sighs, a cloud of dust rise from the floor of the cage.

Her sigh, really distresses me, albeit I understand why she has emitted it; it is her sorrowful recognition of the deprivation to which she has been condemned of her natural right to devour man, whom she has every reason to regard as her enemy.

“To-morrow,” I tell her. “To-morrow, my dear, this torment will be at an end. It is true that this torment still means something to you, and that, when it is over, nothing will matter to you any more. But if you have to choose between this torment and nothing, perhaps nothing is preferable! A captive like this, far from your savage haunts, powerless to tear anyone to pieces, or even to frighten him, what sort of tiger are you? Hark! They are making ready the big cage out there…. You are accustomed already to hearing these hammer-blows, and pay no attention to them. In this respect, you see, you are more fortunate than man: man may think, when he hears the hammer-blows: ‘There, those are for me; that is the undertaker, getting my coffin ready.’ You are already there, in your coffin, and do not know it: it will be a far larger cage than this; and you will have the comfort of a touch of local colour there too: it will represent a glade in a forest. The cage in which you now are will be carried out there and placed so that it opens into the other. A stage hand will climb on the roof of this cage, and pull up the door, while another man opens the door of the other cage; and you will then steal in between the tree trunks, cautious and wondering. But immediately you will notice a curious ticking noise. Nothing! It will be I, winding my machine on its tripod; yes, I shall be in the cage too, beside you; but don’t pay any attention to me! Do you see? Standing a little way in front of me is another man, another man who takes aim at you and fires, ah! there you are on the ground, a dead weight, brought down in your spring…. I shall come up to you; with no risk to the machine, I shall register your last convulsions, and so good-bye!”

If it ends like that…

This evening, on coming out of the Positive Department, where, in view of Borgalli’s urgency, I have been lending a hand myself in the developing and joining of the sections of this monstrous film, I saw Aldo Nuti advancing upon me with the unusual intention of accompanying me home. I at once observed that he was trying, or rather forcing himself not to let me see that he had something to say to me.

“Are you going home?”

“Yes.”

“So am I.”

When we had gone some distance he asked:

“Have you been in the rehearsal theatre to-day?”

“No. I’ve been working downstairs, in the dark room.”

Silence for a while. Then he made a painful effort to smile, with what he intended for a smile of satisfaction.

“They were trying my scenes. Everyone was pleased with them. I should never have imagined that they would come out so well. One especially.

I wish you could have seen it.”

“Which one?”

“The one that shews me by myself for a minute, close up, with a finger on my lips, like this, engaged in thinking. It lasts a little too long, perhaps… my face is a little too prominent … and my eyes…. You can count my eyelashes. I thought I should never disappear from the screen.”

I turned to look at him; but he at once took refuge in an obvious reflexion:

“Yes!” he said. “Curious the effect our own appearance has on us in a photograph, even on a plain card, when we look at it for the first time. Why is it?”

“Perhaps,” I answered, “because we feel that we are fixed there in a moment of time which no longer exists in ourselves; which will remain, and become steadily more remote.”

“Perhaps!” he sighed. “Always more remote for us….”

“No,” I went on, “for the picture as well. The picture ages too, just as we gradually age. It ages, although it is fixed there for ever in that moment; it ages young, if we are young, because that young man in the picture becomes older year by year with us, in us.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“It is quite easy to understand, if you will think a little. Just listen: the time, there, of the picture, does not advance, does not keep moving on, hour by hour, with us, into the future; you expect it to remain fixed at that point, but it is moving too, in the opposite direction; it recedes farther and farther into the past, that time. Consequently the picture itself is a dead thing which as time goes on recedes gradually farther into the past: and the younger it is the older and more remote it becomes.”

“Ah, yes, I see what you mean…. Yes, yes,” he said. “But there is something sadder still. A picture that has grown old young and empty.”

“How do you mean, empty?”

“The picture of somebody who has died young.”

I again turned to look at him; but he at once added:

“I have a portrait of my father, who died quite young, at about my age; so long ago that I don’t remember him. I have kept it reverently, this picture of him, although it means nothing to me. It has grown old too, yes, receding, as you say, into the past. But time, in ageing the picture, has not aged my father; my father has not lived through this period of time. And he presents himself before me empty, devoid of all the life that for him has not existed; he presents himself before me with his old picture of himself as a young man, which says nothing to me, which cannot say anything to me, because he does not even know that I exist. It is, in fact, a portrait he had made of himself before he married; a portrait, therefore, of a time when he was not my father. I do not exist in him, there, just as all my life has been lived without him.”

“It is sad….”

“Sad, yes. But in every family, in the old photograph albums, on the little table by the sofa in every provincial drawing-room, think of all the faded portraits of people who no longer mean anything to us, of whom we no longer know who they were, what they did, how they died….”

All of a sudden he changed the subject to ask me, with a frown:

“How long can a film be made to last?”

He no longer turned to me as to a person with whom he took pleasure in conversing; but in my capacity as an operator. And the tone of his voice was so different, the expression of his face had so changed that I suddenly felt rise up in me once again that contempt which for some time past I have been cherishing for everything and everybody. Why did he wish to know how long a film could last? Had he attached himself to me to find out this? Or from a desire to make my flesh creep, leaving me to guess that he intended to do something rash that very day, so that our walk together should leave me with a tragic memory or a sense of remorse?

I felt tempted to stop short in front of him and to shout in his face:

“I say, my dear fellow, you can drop all that with me, because I don’t take the slightest interest in you! You can do all the mad things you please, this evening, to-morrow: I shan’t stir! You may perhaps have asked me how long a film can last to make me think that you are leaving behind you that picture of yourself with your finger on your lips? And you think perhaps that you are going to fill the whole world with pity and terror with that enlarged picture, in which ‘they can count your eyelashes’? How long do you expect a film to last?”

I shrugged my shoulders and answered:

“It all depends upon how often it is used.”

He too from the change in my tone must have realised that my attitude towards him had changed also, and he began to look at me in a way that troubled me.

The position was this: he was still here on earth a petty creature. Useless, almost a nonentity; but he existed, and was walking beside me, and was suffering. It was true that he was suffering, like all the rest of us, from life which is the true malady of us all. He was suffering for no worthy reason; but whose fault was it if he had been born so petty? Petty as he was, he was suffering, and his suffering was great for him, however unworthy…. It was from life that he suffered, from one of the innumerable accidents of life, which had fallen upon him to take from him the little that he had in him and rend end destroy him! At the moment he was here, Etili walking by my side, on a June evening, the sweetness of which he could not taste; to-morrow perhaps, since life had so turned against him, he would no longer exist: those legs of his would never be set in motion again to walk; he would never see again this avenue along which we were going; and he would never again clothe his feet in those fine patent leather shoes and those silk socks, would never again take pleasure, even in the height of his desperation, as he stood before the glass of his wardrobe every morning, in the elegance of the faultless coat upon his handsome slim body which I could put out my hand now and touch, still living, conscious, by ray side.

“Brother….”

No, I did not utter that word. There are certain words that we hear, in a fleeting moment; we do not say them. Christ could say them, who was not dressed like me and was not, like me, an operator. Amid a human society which delights in a cinematographic show and tolerates a profession like mine, certain words, certain emotions become ridiculous.

“If I were to call this Signor Nuti ‘brother’,” I thought, “he would take offence; because… I may have taught him a little philosophy as to pictures that grow old, but what am I to him? An operator: a hand that turns a handle.”

He is a “gentleman,” with madness already latent perhaps in the ivory box of his skull, with despair in his heart, but a rich “titled gentleman” who can well remember having known me as a poor student, a humble tutor to Giorgio Mirelli in the villa by Sorrento. He intends to keep the distance between me and himself, and obliges me to keep it too, now, between him and myself: the distance that time and my profession have created. Between him and me, the machine.

“Excuse me,” he asked, just as we were reaching the house, “how will you manage to-morrow about taking the scene of the shooting of the tiger?”

“It is quite easy,” I answered. “I shall be standing behind you.”

“But won’t there be the bars of the cage, all the plants in between?”

“They won’t be in my way. I shall be inside the cage with you.”

He stood and stared at me in surprise:

“You will be inside the cage too?”

“Certainly,” I answered calmly.

“And if… if I were to miss?”

“I know that you are a crack shot. Not that it will make any difference. To-morrow all the actors will be standing round the cage, looking on. Several of them will be armed and ready to fire if you miss.”

He stood for a while lost in thought, as though this information had annoyed him.

Then: “They won’t fire before I do?” he said.

“No, of course not. They will fire if it is necessary.”

“But in that case,” he asked, “why did that fellow… that Signor Ferro insist upon all those conditions, if there is really no danger?”

“Because in Ferro’s case there might perhaps not have been all those others, outside the cage, armed.”

“Ah! Then they are for me? They have taken these precautions for me? How ridiculous! Whose doing is it? Yours, perhaps?”

“Mine, no. What have I got to do with it?”

“How do you know about it, then?”

“Polacco said so.”

“Said so to you? Then it was Polacco? Ah, I shall have something to say to him to-morrow morning! I won’t have it, do you understand? I won’t have it!”

“Are you addressing me?”

“You too!”

“Dear Sir, let me assure you that what you say leaves me perfectly indifferent: hit or miss your tiger; do all the mad things you like inside the cage: I shall not stir a finger, you may be sure of that. Whatever happens, I shall remain quite impassive and go on turning my handle. Bear that in mind, if you please!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XIV

Ik liep uit het licht van de zweef het donker binnen. Dook op in het licht van de mallemolen. Ik draaide een paar rondjes op de molen die veel te dicht bij de grond bleef. Waarop alleen dolle houten paarden stonden die de tong uit hun bek lieten hangen en afgejakkerd waren. Paarden die steeds rondjes draaiden, veel te dicht bij de grond bleven en bij iedere keer dat ze rond kwamen een glimp opvingen van de zweef die hoog door de lucht bogen trok en die zelf weer uitwiste. De zweef liet het mooie meisje de lichten zien van Borz en Gretz. Niet de donkerte van Wrak, waar alleen God woonde onder het puin van zijn kerk. Liet zien wie er vooraan achter het glas zaten in de cafés. Van degenen die achter tegen de muur zaten alleen de voeten liet zien. Cherubijn helemaal niet liet zien, hoewel hij nu vijf houten poten onder zijn kont had. Mij niet liet zien omdat ik in een ander licht ronddraaide, het licht van de houten paarden met de tong uit de bek.

Tijdens de rit die ik maakte op de rug van een van deze uit hout gesneden paarden, merkte ik dat de jongen die de kaartjes knipte helemaal niet van paarden hield. Nog minder van de kinderen die op de paarden zaten en ze geselden met de vlakke hand om ze harder te laten lopen. De beesten konden niet harder. Ze zaten vastgeschroefd aan de houten vloer van de veel te laagbijdegrondse draaimolen en ze moesten dus noodgedwongen het tempo van de vloer volgen. Ze waren volledig in hun vrijheid beknot, lieten daarom de tong ver uit hun bek hangen en hielden zich stil wanneer de kinderen hen sloegen.

Bij ieder rondje van de draaimolen zag ik een glimp van de zweef die rondwentelde in zijn eigen licht. Ik zag dat het de jongen die erin geslaagd was in het stoeltje achter het mooie meisje te gaan zitten, niet lukte haar in de nek te zoenen. De zweef hield vaart in voordat de mallemolen vaart inhield. Pas toen de zweef stil hing en het meisje uitstapte, minderde de mallemolen vaart. Ze liep het trapje van de zweef af. De hoofden van de mensen draaiden allemaal in haar richting. Ze verdween in het donker en dook op in het licht van de mallemolen net toen ik van het paard klom. Ze keek naar me, kwam naar me toe in haar fel gekleurde rok en gaf me een hand. Ik zei: ‘Dag. Ik had in de zweef al wat tegen je willen zeggen, maar de jongens verhinderden me dat.’ Ze boog zich naar me toe. Ik kon in haar blouse kijken. Haar huid was mooi. Ze zei dat ze Alice heette en met me wilde spelen. Ik vond het fijn en ik vertelde haar dat ze dan bij mij, bij Cherubijn en bij de marmot zou moeten gaan wonen. Dat wilde ze graag. Er waren geen problemen over wonen en zo. We zouden dekens gebruiken om er een dekenzak van te maken waar we met zijn drieën in konden slapen, Alice, de marmot en ik.

We speelden: ‘Ik zie, ik zie, wat jij niet ziet, rara wat is dat!’ Ik zag direct wat zíj zag. Meestal duurde het lang voordat zij zag wat ík zag. We speelden niet in de lichtkringen van de mallemolen of de zweef. Ik was bang dat alle mensen jaloers zouden zijn. Toen we genoeg hadden van het spel, deden we landverbeuren, maar dat ging niet goed in het donker. We konden de strepen die we over de grond trokken nauwelijks zien. Zo konden we niet weten of we in elkaars land stonden.

We gaven elkaar een hand en liepen naar de wagen. We gingen in de deuropening zitten en wachtten op Cherubijn. Even later kwam hij de weg afstrompelen en verdween hij in de wagen, zonder naar ons te kijken. Hij viel op het bed neer. Direct snurkte hij als een os.

Ik haalde de dekens uit de wagen. Alice maakte er een slaapzak van waarin we met zijn drieën konden liggen.

We sliepen buiten. Alice lag met haar hoofd op het kussen uit de mand van de marmot. Ik lag met mijn hoofd op de borst van Alice. De marmot lag tussen mijn benen. De dekenzak hield de kou van de nevel tegen.

Het duurde niet lang voor ik sliep. Ik was moe van het spelen en vooral van de reis naar de Lichtstad Kork en van het zitten in de bus die vanuit Kork over de brug van Kork naar Tepple reed, zijn weg vervolgde langs het Lange Rak en Gretz, Wrak en Borz aandeed, daarna de brug bij Borz passeerde met de hoge turnrekken voor de vogels en over Boeroe Oeroe bereikte.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

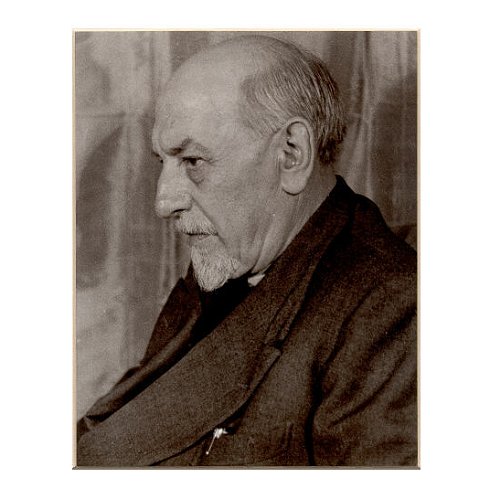

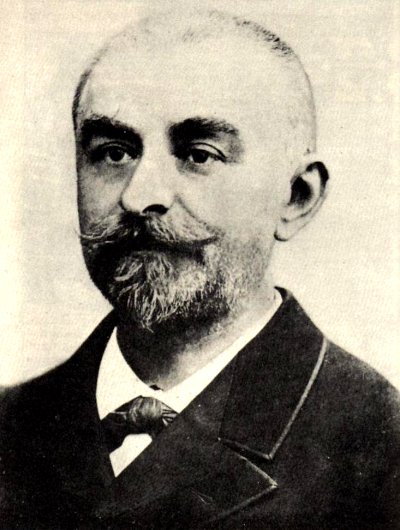

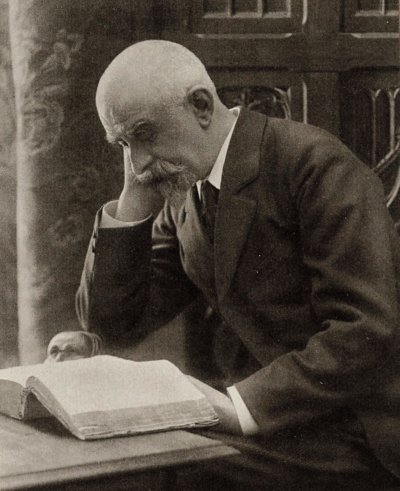

Arij Prins (1860-1922)

J.K. Huysmans,

door Arij Prins

II

Zooals gezegd, hebben de hollandsche schilders der XVIIe eeuw een grooten invloed op dezen artist uitgeoefend. Voor hunne doeken, die in de Louvre hangen, gevoelde hij den aandrang in zich ontwaken met de pen te geven wat zij hebben geschilderd, en hij schreef daarop: Le Drageoir aux Epices, een dun, thans uiterst zeldzaam werkje, vol korte beschrijvingen. Deze stukjes, waarvan enkelen o.a. La Ritournelle later in de Croquis Parisiens zijn opgenomen geworden, zijn over het algemeen vrij middelmatig. De schrijver aarzelt nog, weet nog niet welken weg hij zal opgaan – het is echter niet te loochenen, dat zijne voornaamste eigenschappen, hoewel zwak, reeds in dit boekje zijn te onderkennen.

Veel hooger staat Marthe, eene krachtige, ware studie, die een flink succès had, dank zij den dwazen maatregel van het fransche gouvernement dit werk, in Brussel uitgekomen, op de lijst der verboden boeken te plaatsen.

In dit boek, geschreven voor Nana en La fille Elisa, heeft Huysmans het eerst van alle moderne schrijvers de publieke vrouw zonder sentimentaliteit, in al hare ellende en met al hare goede en slechte eigenschappen geteekend. En juist wijl het beeld zoo streng, zoo droevig juist is en daardoor niets aantrekkelijks en verleidelijks heeft, behoort Marthe tot de hoogst zedelijke werken.

Hare geschiedenis is niets dan de verkondiging van de treurige waarheid, dat de vrouw, die zich eenmaal op het hellend vlak heeft begeven, onverbiddelijk naar omlaag gaat en steeds dieper en dieper zinkt.

Uit zucht naar weelde en genot, uit overgeërfde luiheid gaat zij een los leven leiden, heeft verscheidene minnaars, belandt uit armoede in een verdacht huis, hetwelk zij vol walging ontvlucht, heeft weder eenige minnaars en komt ten laatste op nieuw en nu voor goed in een lupanar terecht.

Ofschoon de taal een weinig gewrongen is, en men Marthe geen ‘rijp’ kunstwerk kan noemen, vindt men evenwel in dit werk uitstekende gedeelten, die van een niet gewoon talent getuigen.

In Les Soeurs Vatard is de artist tot zijn volle ontwikkeling gekomen. Men heeft over dezen roman, die het meest van al zijne werken bekend is, verbazend veel lawaai gemaakt – enkele woorden en zinnen uit hun verband gerukt, en daarmede willen aantoonen, dat nog nooit een schrijver zoo ruw en onbehoorlijk is geweest. Dit zelfde is ook aan Zola verweten, maar daar men hem thans niet meer durft aanvallen, wordt in woorden vol gehuichelde bewondering over zijne werken gesproken, en tegelijk – ten bewijze dat men onbevooroordeeld en vrijzinnig is – aan de jongeren alle talent ontzegd.

De waarheid is, dat Les Soeurs Vatard krachtige, ware beelden en tafreelen uit het leven der parijsche werklieden geeft, en dat onder de oppervlakkige ruwheid een fijn sentiment is verscholen.

In dit knappe werk verhaalt Huysmans de geschiedenis van twee zusters, die in een fabriek arbeiden. De oudste, Céline, leidt een ongeregeld leven, heeft als minnaar Anatole, een soort van schooijer, gaat daarop met een artist wonen, verlaat hem, omdat zij niet bij elkaâr passen, en keert weder tot Anatole terug. Desirée, de jongste, is verstandig. Zij geeft zich niet met mannen af, en droomt eens gelukkig getrouwd te zijn. Een stille vrijage met een fatsoenlijken werkman leidt niet tot een huwelijk, wijl Auguste zoo weinig verdient, en Desirée trouwt daarop met iemand, die zij wel mag, maar om wien zij vroeger nooit heeft gedacht.

Om deze figuren bewegen zich verscheidene bijfiguren, o.a. de vader der beide meisjes Pierre Séraphin Vatard, ‘un homme circonspect et doux, qui eut été un mari parfait sans une belle indifférence pour les mille tracas de la vie et une invincible paresse à les surmonter.’

Groote menschenkennis spreekt er uit de wijze, waarop Huysmans dezen werkman het loszinnig gedrag van zijn dochter laat beoordeelen.

‘Il lui avait reproché en termes de cour d’assises, la crapule de ses moeurs, mais elle s’était fachée, avait jeté la maison sens dessus-dessous, menaçant de tout saccager si on l’embêtait encore. Vatard avait alors adopté une grande indulgence, puis le terrible bagout de sa fille le divertissait pendant sa digestion, le soir. Elle lui semblait même trés emerillonnée et très folâtre. Les expressions de barrière, ses gestes de bastringue, ses rires de fille, qui connait la vie, lui rappelaient sa jeunesse et une certaine maîtresse, qu’il aurait pu aimer.‘

Hoe lijnrecht staat Huysmans in deze bladzijden tegenover de valsche idealisten, die in zulk een geval van den vader een onmogelijk sentimenteelen arbeider vol nobele denkbeelden, in strijd met zijn opvoeding en begrippen, zouden hebben gemaakt.

In het laatste gedeelte van Les Soeurs Vatard, schooner van compositie en soberder geschreven, dan de eerste helft van het werk, zijn zeer fraaie gedeelten, zooals de beschrijving, van de avondwandelingen van Desirée en Auguste in de eenzame rue de Colignon, vol van eene fijne, diepe melancholie, die den lezer aangrijpt.

Les Soeurs Vatard is vol breede, krachtige beschrijvingen van de omgeving, waarin zijne personen leven, maar aan zijn hartstocht om te schilderen geeft Huysmans zich eerst in zijn volgend werk Croquis Parisiens ten volle over.

In dit zeldzame boek – met etsen van Raffaeli en Forain – heeft hij zijn taal nog meer verfijnd en verrijkt. Elk der korte stukjes is dan ook een juweel van beschrijving, hetwelk men steeds met meer genot herleest. Les Similitudes treft ons door het fantastische, den oosterschen gloed, weergegeven in woorden die de fijnste schakeering uitdrukken, en in Les Folies Bergères beschrijft Huysmans dit café chantant op zulk eene meesterlijke wijze, dat het alledaagsche en gewone verheven wordt. In dit stuk hebben zijne zinnen eene statigheid, die men slechts in het proza van Flaubert en Villiers de l’Isle Adam aantreft.

Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848–1907)

Het streven om het leven zooveel mogelijk nabij te komen, zoowel als de behoefte om zijne aandoeningen te uiten, brengen menig auteur er toe, de indrukken, die hij ontvangt en de gedachten, die hem bezig houden in zijne personen over te brengen, waarvan het gevolg is, dat zij zich door hun gewaarwordingen en innerlijken strijd boven het gewone menschelijke verheffen.

Deze eigenschap, welke Huysmans met vele schrijvers gemeen heeft, wordt natuurlijk een psychologische fout, zoodra de artist alledaagsche menschen behandelt.

Als Huysmans bijv. in Les Soeurs Vatard (hoofdst. XVI) Desirée en Céline uit haar venster over den spoorbaan laat kijken, geeft hij eene prachtige beschrijving van een modern onderwerp, maar hij gaat te ver door aan deze meisjes een fijnheid van opmerking, een sentiment voor kleur te geven, welke hij bezit.

In En Ménage hindert ons niets van dien aard, wijl de beide hoofdpersonen, de letterkundige André Jayant en de schilder Cyprien Fibaille fijn ontwikkelde, nerveuse artisten zijn. –

Deze roman, naar mijne meening een der voortreffelijkste van onzen tijd – is, wat de geschiedenis betreft, zeer eenvoudig. Op een ongelukkigen avond komt André Jayant onverwacht naar huis en vindt een hem onbekende heer bij zijne vrouw. Eene scheiding is daarvan het gevolg, en de jonge man gaat op kamers wonen. Langzamerhand begint hij zich te vervelen, hij gevoelt behoefte aan een vrouw, kan niet meer werken – en neemt een maitresse. Deze liaison duurt niet lang, uit onverschilligheid, en ook wijl ze hem te veel geld kost, komt hij niet meer bij Blanche terug. Daarop ontmoet hij een meisje, dat hij vroeger heeft gekend, en leeft met haar tot zij naar Londen moet vertrekken. Deze scheiding dompelt hem op nieuw in het grijze, eentonige leven – en het eenige redmiddel is zich met zijn vrouw te verzoenen. De wond, die zij hem heeft toegebracht, is langzamerhand geheeld en hij vergeeft haar alles, waarop zij weder tezamen gaan wonen.

De knappe eigenschappen van dit werk, waarin geen zwakheid te ontdekken is, zijn veelzijdig. Naast de sobere realiteit, die reeds in het eerste hoofdstuk – als André te huis komend, de fatale ontdekking doet – tot hare volle uiting komt, moet men de groote psychologische kennis bewonderen. Weinig schrijvers zijn dan ook zoo diep in alle aandoeningen hunner personen doorgedrongen als Huysmans. Hij verbergt geen hunner zwakheden en hartstochten, en juist wijl niets verzwegen wordt, zijn zij zoo geheel mensch. Als de auteur in hoofdstuk VIII de gevolgen beschrijft van een losbandigen nacht en de ellende van den volgenden dag aantoont, herinnert hij den lezer aan hetgeen hijzelf wel heeft ondervonden. Ook hoofdst. VI, waarin La Crise Juponnière wordt beschreven, is een juiste, doordringende bladzijde uit het groote boek der menschelijke kwalen.

De drie vrouwen, die zich om André bewegen: Berthe, de stijve, getrouwe dame met burgerlijke ondeugden; Blanche, de prostituée van beroep, en Jeanne, de sympathieke minnares, zijn ware, levendig geteekende figuren, wier karakters en eigenschappen door fijne trekjes worden aangetoond.

Men heeft gezegd, dat in André en des Esseintes uit A Rebours geen onderscheid kan ontdekt worden. Dit is onjuist, want de eigenschappen der nerveuse, pessimistische menschen zijn bij laatstgenoemde zoo sterk ontwikkeld, dat hij een uitzondering is en bijna al het menschelijke heeft verloren. Deze jonge man, wiens zenuwen door het geringste in beroering worden gebracht, is onmachtig handelend op te treden, en zijn geringe levenskracht concentreert zich in zijne hersenen, die slechts indrukken opnemen en verwerken.

Ziekelijk, vol walging voor de wereld, waarin hij leeft en voor het genot, dat hij onder alle vormen heeft gesmaakt, trekt des Esseintes zich in een oud kasteel terug, hetwelk hij op de grilligste en meest verfijnde wijze laat inrichten. Daar brengt hij zijn tijd door met zich alles voor den geest te roepen wat hij heeft genoten, gezien en ondervonden, tot hij ziek wordt en voor zijne gezondheid naar Parijs moet terugkeeren.

Door dit vreemdsoortige werk, hetwelk de ziekelijke schoonheid van een teedere kasplant bezit, heeft het talent van Huysmans in een zekere richting de uiterste grens bereikt.

De grootste verdiensten van A Rebours zijn behalve het curieuse zielkundige proces, de meesterlijke schilderingen, nu eens vol realiteit, dan weder phantastisch, geheimzinnig, als de novellen van Edgar Allan Poe.

Na dezen roman – verschenen in 1884 – heeft Huysmans niets nieuws uitgegeven dan enkele bladzijden, o.a. de grootsche beschrijving van de Ouverture der Tannhäuser, want hij behoort niet tot die auteurs, welke ieder jaar – met het gemak van een leggende hen – van een paar dikke deelen bevallen. – Zijn rijk talent, alvorens zich wellicht op een anderen weg te begeven, schijnt behoefte aan rust te hebben.

April 1886

Arij Prins over J.-K. Huysmans

bron: De Nieuwe Gids. Jaargang 1. W. Versluys, Amsterdam 1885-1886

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Huysmans, Joris-Karl, J.-K. Huysmans

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XIII

In het eerste het beste café verdiende ik geld genoeg om Cherubijn aan een tafeltje achter te laten. Met de vier poten van de stoel zaten er dus vijf houten poten aan het tafeltje.

Ik holde terug naar de wagen en legde de marmot in de mand. Het beest sloot direct de ogen.

Terug op de kermis was de zweef net aan een vlucht begonnen, draaide enorm hard in het rond. Meer nog dan de avond ervoor leken mij de rokken van de meisjes gekleurd. Meer nog luisterde ik naar het smakken van de zoenen van de jongens in de nekken van de meisjes.

In de volgende rit schoot ik achter de rokken aan. Ik liet het zoenen achterwege. Luisterde alleen naar het zoenen. Ik kon het niet goed horen, want ook de as van de zweef die zichtbaar over kogels liep, maakte zuigende geluiden. Ik liet de meisjes in hun rokken en keek naar de lichten van Borz en Gretz. Het was intussen donker geworden. Ik probeerde ook Wrak te zien. Dat was onmogelijk. In Wrak was geen licht. Alleen God woonde er in zijn gouden huis, waar de hele kerk zich met toren en al op had gestort.

Ik draaide bijna horizontaal over de aarde. Zag de gezichten van de mensen die van plan waren enkel naar de rokken van de meisjes te kijken. En naar het zoenen te luisteren. Ik had dat plan laten varen door de bedenkelijke geluiden van de as. Ik kon in de cafés naar binnen kijken, maar ik zag Cherubijn niet, hoewel ik lette op een stoel met vijf houten poten. Vanaf deze hoogte zag je alleen de mensen die vooraan achter het venster zaten. Van de rest zag ik alleen de benen. Van degenen die achterin zaten zag ik enkel de schoenen. Cherubijn moest ergens midden in het café zitten. Dus verwachtte ik zijn hele onderlijf te zien.

De rest van de rit bleef ik draaien met gesloten ogen. Het was of er een scherm over me werd neergelaten. Of daarna iemand in mij het doek opentrok en aankondigde: ‘Dit is de vluchteling, hij zwaait langs het firmament. Hij sluit zijn ogen voor wie hem zoeken. Wee, wee, wee.’ Daarna werd het doek in mij dichtgetrokken.

De zweef minderde snelheid. Ik opende mijn ogen, zag de grond dichterbij komen. De gezichten van de mensen. Het waren geen eerlijke gezichten. Ze keken stiekem, al belette niemand hen om open om zich heen te kijken. Het leek of ze iets misten in hun leven.

Het bakje hing stil. Ik moest haastig de ketting losmaken om eruit te komen. Er stonden diverse kerels aan me te trekken, bereid voor het bakje te vechten, want er was een heel mooi meisje in het stoeltje voor me gaan zitten. Ik zou onder het zweven graag ‘dag’ tegen haar zeggen. Ze zou beslist wat terugzeggen. Het was al te laat. Mijn stoeltje was al bezet. Ik liep het trapje af. Alle mensen keken naar dat ene meisje. Ze beseften dat God zijn schepsels niet gelijk had gemaakt: God was niet eerlijk, de een gaf hij alles, de ander niets. Zij die rond de zweef stonden en te weinig moois hadden gekregen, trachtten dat goed te maken door naar de kleurige rok van het beeldschone meisje te kijken. Ze bleven totaal onkundig van hun vrije wil.

Ik had genoeg van de zweef, voelde me evenals de andere kijkers bedrukt omdat ik geen kans zag wat tegen het meisje te zeggen. Ik had ‘dag’ tegen haar willen zeggen. Of: ‘Wat ben je mooi,’ of: ‘Ik zou wel bij je willen blijven. Dan moet je ook bij Cherubijn en bij de marmot blijven.’

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (33)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

2

Trapped. That is all. This and this only is what Nestoroff wished–that it should be he who entered the cage.

With what object? That seems to me easily understood, after the way in which she has arranged things: that is to say that everyone, first of all, heaping contempt upon Carlo Ferro whom she had persuaded or forced to go away, should insist that there was no danger involved in entering the cage, so that afterwards the challenge of Nuti’s offer to enter it should seem all the more ridiculous, and, by the laughter with which that challenge was greeted, the other’s self-esteem might emerge if not unscathed still with the least possible damage; with no damage at all, indeed, since, with the malign satisfaction which people feel on seeing a poor bird caught in a snare, that the snare in question was not a pleasant thing everyone is now prepared to admit; all the more credit, therefore, to Ferro who has managed to free himself from it at this sparrow’s expense. In short, this to my mind is clearly what she wished: to take in Nuti, by shewing him her heartfelt determination to spare Ferro even a trifling inconvenience and the mere shadow of a remote danger, such as that of entering a cage and firing at an animal which everyone says is cowed by all these months of captivity. There: she has taken him neatly by the nose and amid universal laughter has led him into the cage.

Even the most moral of moralists, unintentionally, between the lines of their fables, allow us to observe their keen delight in the cunning of the fox, at the expense of the wolf or the rabbit or the hen: and heaven only knows what the fox represents in those fables! The moral to be drawn from them is always this: that the loss and the ridicule are borne by the foolish, the timid, the simple, and that the thing to be valued above all is therefore cunning, even when the fox fails to reach the grapes and says that they are sour. A fine moral! But this is a trick that the fox is always playing on the moralists, who, do what they may, can never succeed in making him cut a sorry figure. Have you laughed at the fable of the fox and the grapes? I never did. Because no wisdom has ever seemed to me wiser than this, which teaches us to cure ourselves of every desire by despising its object.

This, you understand, I am now saying of myself, who would like to be a fox and am not. I cannot find it in me to say sour grapes to Signorina Luisetta. And that poor child, whose heart I have not been able to reach, here she is doing everything in her power to make me, in her company, lose my reason, my calm impassivity, abandon the fine wise course which I have repeatedly declared my intention of following, in short all my boasted ‘inanimate silence’. I should like to despise her, Signorina Luisetta, when I see her throwing herself away like this upon that fool; I cannot. The poor child can no longer

sleep, and comes to tell me so every morning in my room, with eyes that change in colour, now a deep blue, now a pale green, with pupils that now dilate with terror, now contract to a pair of pin-points which seem stabbed by the most acute anguish.

I say to her: “You don’t sleep? Why not?” prompted by a malicious desire, which I would like to repress but cannot, to annoy her. Her youth, the calm weather ought surely to coax her to sleep. No? Why not? I feel a strong inclination to force her to tell me that she lies awake because she is afraid that he… Indeed? And then: “No, no, sleep sound, everything is going well, going perfectly. You should see the energy with which he has set to work to interpret his part in the tiger film! And he does it really well, because as a boy he used to say that if his grandfather had allowed it, he would have gone upon the stage; and he would not have been wrong! A marvellous natural aptitude; a true thoroughbred distinction; the perfect composure of an

English gentleman following the perfidious ‘Miss’ on her travels in the East! And you ought to see the courteous submission with which he accepts advice from the professional actors, from the producers Bertini and Polacco, and how delighted he is with their praise! So there is nothing to be afraid of, Signorina. He is perfectly calm….” “How do you account for that?” “Why, in this way, perhaps, that having never done anything, lucky fellow, in his life, now that, by force of circumstances, he has set himself to do something, and the very thing that at one time he would have liked to do, he has taken a fancy to it, finds distraction in it, flatters his vanity with it.”

No! Signorina Luisetta says no, persists in repeating no, no, no; that it does not seem to her possible; that she cannot believe it; that he must be brooding over some act of violence, which he is keeping dark.

Nothing could be easier, when a suspicion of this sort has taken root, than to find a corroborating significance in every trifling action. And Signorina Luisetta finds so many! And she comes and tells me about them every morning in my room: “He is writing,” “He is frowning,” “He never looked up,” “He forgot to say good morning….”

“Yes, Signorina, and what about this; he blew his nose with his left hand this morning, instead of using his right!”

Signorina Luisetta does not laugh: she looks at me, frowning, to see whether I am serious: then goes away in a dudgeon and sends to my room Cavalena, her father, who (I can see) is doing everything in his power, poor man, to overcome in my presence the consternation which his daughter has succeeded in conveying to him in its strongest form, trying to rise to abstract considerations.

“Women!” he begins, throwing out his hands. “You, fortunately for yourself (and may it always remain so, I wish with, all my heart, Signor Gubbio!) have never encountered the Enemy upon your path. But look at me! What fools the men are who, when they hear woman called’the enemy,’ at once retort: ‘But what about your mother? Your sisters? Your daughters?’ as though to a man, who in that case is a son, a brother, a father, those were women! Women, indeed! One’s mother? You have to consider your mother in relation to your father, and your sisters or daughters in relation to their husbands; then the true woman, the enemy will emerge! Is there anything dearer to me than my poor darling child? Yet I have not the slightest hesitation in admitting, Signor Gubbio, that even she, undoubtedly, even my Sesè is capable of becoming, like all other women when face to face with man, the enemy. And there is no goodness of heart, there is no submissiveness that can restrain them, believe me! When, at a turn in the road, you meet her, the particular woman, to whom I refer, the enemy: then one of two things must happen: either you kill her, or you have to submit, as I have done. But how many men are capable of submitting as I have done? Grant me at least the meagre satisfaction of saying very few, Signor Gubbio, very few!”

I reply that I entirely agree with him.

Whereupon: “You agree?” asks Cavalena, with a surprise which he makes haste to conceal, fearing lest from his surprise I may divine his purpose. “You agree?”

And he looks me timidly in the face, as though seeking the right moment to descend, without marring our agreement, from the abstract consideration to the concrete instance. But here I quickly stop him.

“Good Lord, but why,” I ask him, “must you believe in such a desperate resolution on Signora Nestoroff’s part to be Signor Nuti’s enemy!”

“What’s that? But surely? Don’t you think so? But she is! She is the enemy!” exclaims Cavalena. “That seems to me to be unquestionable!”

“And why?” I persisted. “What seems to me unquestionable is that she has no desire to be his friend or his enemy or anything at all.”

“But that is just the point!” Cavalena interrupts me. “Surely; or do you mean that we ought to consider woman in and by herself? Always in relation to a man, Signor Gubbio! The greater enemy, in certain cases, the more indifferent she is! And in this case, indifference, really, at this stage? After all the harm that she has done him? And she doesn’t stop at that; she must make a mock of him, too. Really!”

I gaze at him for a while in silence, then with a sigh return to my original question:

“Very good. But why must you now believe that the indifference and mockery of Signora Nestoroff have provoked Signor Nuti to (what shall I say?) anger, scorn, violent plans of revenge? On what do you base your argument? He certainly shews no sign of it! He keeps perfectly calm, he is looking forward with evident pleasure to his part as an English gentleman….”

“It is not natural! It is not natural!” Cavalena protests, shrugging his shoulders. “Believe me, Signor Gubbio, it is not natural! My daughter is right. If I saw him cry with rage or grief, rave, writhe, waste away, I should say ‘amen’. You see, he is tending towards one or other alternative.”

“You mean?”

“The alternatives between which a man can choose when he is face to face with the enemy. Do you follow me? But this calm, no, it is not natural! We have seen him go mad here, for this woman, raving mad; and now…. Why, it is not natural! It is not natural!”

At this point I make a sign with my finger, which poor Cavalena does not at first understand.

“What do you mean?” he asks me.

I repeat the sign; then, in the most placid of tones:

“Go up higher, my friend, go up higher….” “Higher… what do you mean?”

“A step higher, Signor Fabrizio; rise a step above these abstract considerations, of which you began by giving me a specimen. Believe me, if you are in search of comfort, it is the only way. And it is the fashionable way, too, to-day.”

“And what is that?” asks Cavalena, bewildered.

To which I:

“Escape, Signor Fabrizio, escape; fly from the drama! It is a fine thing, and it is the fashion, too, I tell you. Let yourself e-va-po-rate in (shall we say?) lyrical expansion, above the brutal necessities of life, so ill-timed and out of place and illogical; up, a step above every reality that threatens to plant itself, in its petty crudity, before our eyes. Imitate, in short, the songbirds in cages, Signor Fabrizio, which do indeed, as they hop from perch to perch, cast their droppings here and there, but afterwards spread their wings and fly: there, you see, prose and poetry; it is the fashion. Whenever things go amiss, whenever two people, let us say, come to blows or draw their knives, up, look above you, study the weather, watch the swallows dart by, or the bats if you like, count the passing clouds; note in what phase the moon is, and if the stars are of gold or silver. You will be considered original, and will appear to enjoy a vaster understanding of life.”

Cavalena stares at me open-eyed: perhaps he thinks me mad.

Then: “Ah,” he says, “to be able to do that!”

“The easiest thing in the world, Signor Fabrizio! What does it require? As soon as a drama begins to take shape before you, as soon as things promise to assume a little consistency and are about to spring up before you solid, concrete, menacing, just liberate from within you the madman, the frenzied poet, armed with a suction pump; begin to pump out of the prose of that mean and sordid reality a little bitter poetry, and there you are!”

“But the heart?” asks Cavalena.

“What heart?”

“Good God, the heart! One would need to be without one!”

“The heart, Signor Fabrizio! Nothing of the sort. Foolishness. What do you suppose it matters to my heart if Tizio weeps or Cajo weds, if Sempronio slays Filano, and so on? I escape, I avoid the drama, I expand, look, I expand!”

What do expand more and more are the eyes of poor Cavalena. I rise to my feet and say to him in conclusion:

“In a word, to your consternation and that of your daughter, Signor Fabrizio, my answer is this: that I do not wish to hear any more; I am weary of the whole business, and should like to send you all to blazes. Signor Fabrizio, tell your daughter this: my job is to be an operator, there!”

And off I go to the Kosmograph.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (33)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Frank Wedekind

(1864-1918

Brigitte B.

Ein junges Mädchen kam nach Baden,

Brigitte B. war sie genannt,

Fand Stellung dort in einem Laden,

Wo sie gut angeschrieben stand.

Die Dame, schon ein wenig älter,

War dem Geschäfte zugetan,

Der Herr ein höherer Angestellter

Der königlichen Eisenbahn.

Die Dame sagt nun eines Tages,

Wie man zur Nacht gegessen hat:

»Nimm dies Paket, mein Kind, und trag es

Zu der Baronin vor der Stadt.«

Auf diesem Wege traf Brigitte

Jedoch ein Individium,

Das hat an sie nur eine Bitte,

Wenn nicht, dann bringe er sich um.

Brigitte, völlig unerfahren,

Gab sich ihm mehr aus Mitleid hin.

Drauf ging er fort mit ihren Waren

Und ließ sie in der Lage drin.

Sie konnt es anfangs gar nicht fassen,

Dann lief sie heulend und gestand,

Daß sie sich hat verführen lassen,

Was die Madam begreiflich fand.

Daß aber dabei die Tournüre

Für die Baronin vor der Stadt

Gestohlen worden sei, das schnüre

Das Herz ihr ab, sie hab sie satt.

Brigitte warf sich vor ihr nieder,

Sie sei gewiß nicht mehr so dumm;

Den Abend aber schlief sie wieder

Bei ihrem Individium.

Und als die Herrschaft dann um Pfingsten

Ausflog mit dem Gesangverein,

Lud sie ihn ohne die geringsten

Bedenken abends zu sich ein.

Sofort ließ er sich alles zeigen,

Den Schreibtisch und den Kassenschrank,

Macht die Papiere sich zu eigen

Und zollt ihr nicht mal mehr den Dank.

Brigitte, als sie nun gesehen,

Was ihr Geliebter angericht’,

Entwich auf unhörbaren Zehen

Dem Ehepaar aus dem Gesicht.

Vorgestern hat man sie gefangen,

Es läßt sich nicht erzählen, wo;

Dem Jüngling, der die Tat begangen,

Dem ging es gestern ebenso.

Frank Wedekind poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Frank Wedekind

Arij Prins (1860-1922)

J.K. Huysmans,

door Arij Prins

I

De werken van dezen artist worden slechts door weinigen begrepen, wijl zij hooge, moeielijke kunst zijn.

Het groote publiek, voorgelicht door onkundige critici, zonder kunstenaarsziel, die angstvallig gekeerd zijn tegen elke nieuwe uiting, beschouwt Huysmans als een soort van letterkundigen anarchist, die het ‘schoone’ tracht omver te werpen, en met voorliefde in het onreine wroet.

De volbloed naturalisten daarentegen duiden het hem euvel, dat hij in A Rebours der werkelijkheid ontrouw is geworden, en in des Esseintes eene onmogelijke, onbestaanbare persoonlijkheid heeft gegeven.

Maar voor ‘les raffinés’, die noch aan het onderwerp, noch aan een school hechten, is Huysmans laatste roman de meesterlijke droom van een verfijnd nerveus artist.

Dit verschil van meening, waardoor bewezen wordt dat iedereen, hetgeen zeer menschelijk is, zich het meest voelt aangetrokken tot die werken, welke met zijn temperament in overeenstemming zijn, heeft mij er toe gebracht den arbeid van een artist te ontleden, die, alhoewel van nederlandsche afkomst, in ons vaderland bijna geheel onbekend is.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Huysmans behoort niet tot die kunstenaars, wier talent slechts naar een kant sterk ontwikkeld is, slechts één overheerschende eigenschap heeft, waardoor het gemakkelijk is hunne werken te analyseeren. Integendeel bij een nauwgezet bestudeeren zijner romans ontdekt men steeds nieuwe zijden van zijn talent. Deze veelzijdigheid, deze aaneenschakeling van schoone eigenschappen, welke men slechts bij eerste rangs artisten aantreft, verzwaart de critiek, en is een der hoofdoorzaken, dat Huysmans bijna immer verkeerd beoordeeld wordt.

De meeste lieden, hun oordeel grondend op het stoute, krachtige realisme, dat in Huysmans’ werken doorstraalt, hebben hem bij Zola vergeleken, en zelfs gezegd dat hij hem navolgde. Dit is eene grove dwaling.

Zola verheerlijkt zijn tijd in de bewonderenswaardige serie der Rougon Macquart, het groote letterkundige monument dezer eeuw. Hij schildert met breede, krachtige lijnen en sterke kleuren alle lagen der maatschappij. En ofschoon de voorvechter van het naturalisme, wordt hij dikwijls door vroegere lectuur en denkbeelden tot het romantische aangetrokken, waardoor menig bladzijde in zijn romans – vooral in Germinal – in tegenspraak met zijne kunstbeginselen is.

Huysmans, die trouwens jonger is, staat in het geheel niet onder den invloed der romantiek. Hij mist de verbazingwekkende kracht en het overweldigende van Zola, maar is daarentegen fijner, nerveuser en dringt dieper door in de aandoeningen zijner personen.

Zeer zelden behandelt hij ook een grooten kring van menschen, meestal teekent hij enkele personen, doorgaans zelfs in eene beperkte omgeving. – En als hij de behoefte gevoelt het moderne Parijs te ontvluchten, dat hij met smartelijke volharding bestudeert, droomt hij in A Rebours eene ideale woning, waarin zich de ziekelijke des Esseintes beweegt, die door zijne aandoeningen en denkbeelden op de uiterste grens van het menschelijke staat.

Eveneens is er groot verschil in de taal van beide schrijvers. Zola’s zinnen zijn machtig, zwaar gebouwd, vallen als mokerslagen neder, en alhoewel hij over een rijken woordenschat beschikt, blijft hij eenvoudig, zelfs verstaanbaar voor vreemdelingen. – Huysmans bewerkt, ciseleert zijne zinnen meer, tracht evenals Flaubert, de allerfijnste indrukken weder te geven, en om dit te bereiken bedient hij zich van nieuwe, ongekende uitdrukkingen, of graaft, zooals in A Rebours, oude vergeten woorden op.

Bij Huysmans geniet men reeds bij het lezen van enkele regels; bij Zola staat men vol bewondering voor een bladzijde.

Groot onderscheid is er ook in den grondtoon hunner werken. Beide kunstenaars zijn pessimisten, maar in verschillenden graad.

Zola is vol medelijden, milder, dikwijls zelfs optimistisch, want hij bewondert onze eeuw en ziet met groot vertrouwen de toekomst tegemoet. Huysmans verfoeit, verafschuwt onzen tijd en schaart zich naast Edm. de Goncourt, die van le menaçant avenir promis par le petrole et la dynamite spreekt. (Zie voorrede van Chérie.) En in al zijne werken bespeurt men, dat hij van het ellendige, het doellooze, het nietige van ons bestaan overtuigd is.

In de meesterlijke studie, die de groote fransche criticus Emile Hennequin over Le Pessimisme des Ecrivains heeft geschreven, zegt hij:

‘Comme la rose et comme l’orchidée double, l’homme supérieur, l’artiste, l’homme de lettres est un monstre, un être factice et délicat, incomplet en certaines parties, anomalement developpé en d’autres. Il est constitué d’une façon spéciale, à la fois maladive et admirable, dans son intelligence, sa sensibilité et sa volonté; les émotions qu’il élabore en livres, le soumettent à certaines necessités de letères; il occupe dans la société, à la quelle; il demeure extérieur et étranger, une position nécessairement douloureuse.’

Daarop bewijst Hennequin, dat de zenuwen van zulk een persoon, die voortdurend van alles indrukken ontvangt, welke aan gewone gezonder schepselen onbekend zijn, door den zwaren arbeid, verbazend prikkelbaar en overspannen worden. En verder steunend op Herbert Spencer, die in zijne Principes de psychologie heeft verklaard, que toute impression médiocre et salutaire est agréable, toute impression extréme et nuisible douloureuse, toont hij aan welke de oorzaken zijn, dat de artist aux fibres delicatement vibrantes, au lieu d’être affecté, vivement mais également, par les sensations agréables et les douloureuses tend plutôt à s’assimiler ces dernières et transforme même les jouissances en sources de peine.

Aan Hennequin komt dan ook door deze studie de eer toe, duidelijk te hebben uiteengezet hoe het komt, dat bij de moderne schrijvers als Flaubert, Zola, de Goncourt en Huysmans, aangename indrukken tot donkere, smartelijke bladzijden worden omgezet, en dat het onaangename zelf nog zwarter wordt gemaakt,

Van dit viertal auteurs heeft Huysmans deze eigenschap zeker in de sterkste mate.

Joris-Karl Huysmans (1848–1907)

Door de omstandigheden genoodzaakt in aanraking te komen met eene maatschappij, die hij verfoeit, tot aan den hals gedompeld in de ellende van het dagelijksche bestaan, hebben alle ontberingen en onaangenaamheden, die hij heeft leeren kennen, hem smartelijk getroffen. Niet één schrijver heeft dan ook zoo juist en scherp de aaneenschakeling van kleine misères (die zulk een plaats in ons leven innemen) opgemerkt, geanalyseerd en weergegeven.

In het zoo zeldzame werkje A. Vau l’eau toont hij aan welk een treurig leven de meeste ongehuwde heeren leiden, in L’Obsession hoe landerig men zich na enkele rustdagen gevoelt, en in het meesterlijke hoofdstuk VIII van En Ménage beschrijft hij den onaangenamen dag, die voor menschen met een zwak gestel op een ‘nuit blanche’ volgt. Maar Huysmans is nog dieper in de ellenden van het huishouden, het huwelijksleven en collages, doorgedrongen, en juist wijl zijne opmerkingen zoo menschkundig zijn, zoo geheel overeenstemmen met hetgeen wij zelf ondervinden en gevoelen, treffen zij ons dieper, dan de werken waarin groote catastrophen worden behandeld, en kwalen worden beschreven, die wij als toeschouwers uit de verte bezien.

En het hierboven aangegevene is er ook de oorzaak van, dat Huysmans dit alles op pessimistische wijze beschrijft. Om slechts een voorbeeld aan te halen, volgt uit En Ménage een gedeelte van een gesprek tusschen den letterkundige André Jayant en den schilder Cyprien Fibaille, waarin eerstgenoemde mededeelt waarom hij getrouwd is:

‘Je me suis marié parfaitement, parce que ce moment là était venu, parce que j’étais las de manger froid, dans une assiette en terre de pipe, le diner apprêté par la femme de ménage ou la concierge. J’avais des devants de chemise qui baîllaient, et perdaient leurs boutons, des manchettes fatiguées – comme celles que tu as là, tiens – j’ai toujours manqué de mèches à lampes et de mouchoirs propres. L’été lorsque je sortais, le matin, et ne rentrais que le soir, ma chambre était une fournaise, les stóres et les rideaux étant restés baissés à cause du soleil; l’hiver c’était une glacière sans feu, depuis douze heures. J’ai senti alors le besoin de ne plus manger de potages figés, de voir clair quand tombait la nuit, de me moucher dans des linges propres, d’avoir frais ou chaud suivant la saison. Et tu en arriveras là, mon bon homme; voyons sincèrement, là, est ce une vie que d’être comme j’étais et comme toi, tu es encore? est ce une vie que d’avoir le coeur perpétuellement barbouillé par les crasses des filles; est ce une vie que de désirer une maîtresse lorsqu’on n’en a pas, de s’ennuyer à périr, quand on en possêde une, d’avoir l’âme à vif quand elle vous lâche, et de s’embèter plus formitablement encore quand une nouvelle vous la remplace? Oh non par exemple! Bêtise pour bêtise, le mariage vaut mieux.‘

Hoe somber, troosteloos deze woorden ook zijn, zal toch zeker menigeen er de treffende waarheid van inzien.

Dikwijls ontdekt men in het werk van een kunstenaar hoedanigheden, die, ofschoon schijnbaar met elkander in strijd, toch uit zijn temperament voortvloeien en elkaâr de hand reiken. Zoo ook bij Huysmans, die tegelijk pessimist en humorist is. Zijn humor heeft echter niets gemeen met die der engelsche en duitsche schrijvers. Het grof belachelijke mist men; Huysmans is daarvoor een te fijn gevoelig artist. Om een banale couranten-uitdrukking te bezigen: ‘hij brengt de lachspieren niet in beweging’, maar bij enkele personen, bij enkele scènes geniet de geest door de fijne trekjes en zuiver geestige teekening. – Een uitstekend geslaagde figuur is in dit opzicht Mélanie, de goedige wauwelende dienstbode van André Jayant.

En enkele maal, zooals in de schildering van Gingenet uit Marthe, een schreeuwerige drinkebroêr, denkt men aan de koddige figuren van Brouwer en Ostade. – Daardoor verraadt Huysmans, dat hij van hollandsche afkomst is.

Gesproten uit een geslacht van schilders – zijn vader en grootvader hanteerden het penseel en in de Louvre hangen zelfs doeken van een zijner voorzaten – is het niet te verwonderen, dat Huysmans als beschrijvend artist zeer hoog staat. Met verbazende juistheid en fijn gevoel voor kleur, weet hij den ontvangen indruk van een landschap of stadsgezicht in woorden weer te geven, en zijne beschrijvingen zijn meestal zoo krachtig, dat men ziet hetgeen op het papier is gebracht.

Vurig bewonderaar der oud-hollandsche meesters, heeft Huysmans menigmaal getracht datgene te geven wat zij hebben gepenseeld, o.a. in de meesterlijke kermisbeschrijving in Les Soeurs Vatard.

Met voorliefde schildert hij ook de kwijnende landschappen met halfdoode boomen en bleek, ongezond gras, welke Parijs omringen, of typige oude buurten met smerige, hooge huizen, waarin eene levendige, handeldrijvende bevolking woont. Verscheidene dezer beschrijvingen zijn heerlijke vondsten, want geen artist heeft meer dan Huysmans in alle hoeken en gaten van de groote stad rondgesnuffeld.

Een ander maal, en dit is voornamelijk in den laatsten tijd het geval, verlaat hij de realiteit, en geeft in enkele geniale bladzijden den indruk weder, die de etsen van Odilon Redon op hem hebben gemaakt, of wel beschrijft in A Rebours de schilderij van Gustave Moreau: Salomé dansend voor Hérode: Ses seins ondulent et au frottement de ses colliers, qui tourbillonnent, leurs bouts se dressent; sur la moiteur de sa peu les diamants attachés, scintillent; ses bracelets, ses ceintures, ses bagues crachent des entincelles….

Deze beschrijving wedijvert in schoonheid met de heerlijke bladzijden in Salammbo.

Van groote kracht, gepaard met eene soberheid in woorden, getuigt de wijze waarop de inval der Hunnen wordt geschilderd (A Rebours, pag. 46).

‘Tout disparut dans la poussière des galops, dans la fumée des incendies. Les tenèbres se firent, et les peuples consternés tremblèrent, écoutant passer avec un fracas de tonnerre l’épouvantable trombe. La horde des Huns rasa l’Europe, se rua sur la Gaule s’écrasa dans les plaines de Châlons ou Aétius la pila dans une effroyable charge. La plaine gorgée de sang, moutonna comme une mer de pourpre, deux cent mille cadavres barrèrent la route, brisêrent l’élan de cette avalanche qui deviée, tomba, éclatant en coups de foudre sur l’Italie ou les villes exterminées flambèrent comme des meules.’

In deze bladzijden gevoelde Huysmans de behoefte het moderne leven den rug toe te keeren en zich in vroegere tijden te verplaatsen, waarin zijn phantasie in alle vrijheid kon ronddwalen.

wordt vervolgd

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Huysmans, J.-K., J.-K. Huysmans

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XII

ALICE

Het werd avond. Ik hoorde Cherubijn in de wagen rondscharrelen. Later rook ik dat hij aardappels bakte op het komfoor.

Ik kon de hele wei zien. De lompe koeien. De dromerige melker die door het gras liep, steeds hetzelfde rondje. Hij maakte vage gebaren tegen de hemel. Mompelde wat. Had het blijkbaar erg druk met zich een theorie omtrent de spijsvertering van dieren in het hoofd te praten.

De koeien lagen op hun dikke buik in het gras, maalden de ene pens leeg en de andere vol. Ze wisten nergens van.

Vanuit het dorp klonk muziek. Kermis. Een enkele keer zwierden de zitjes van de zweef boven de daken uit. Dan zag ik in heel kleine kleuren de rokken van de meisjes.

Soms klonken dof de knallen van de kop van jut, wanneer de een of andere vlegel uit Oeroe zijn spieren liet zien aan de dunne meisjes uit Boeroe.

De meisjes uit Boeroe mochten zolang het licht was naar de kermis in Oeroe. Daarna moesten ze naar huis gaan, met hun dunne en vleselijke verlangens die niets met dikte en leeftijd te maken hadden.

Cherubijn riep. Zijn stem klonk dof uit de wagen. Het geluid leek op het neuzige geluid van de koeien wanneer die wat te zeggen hadden. Over de toestand van het avondgras bijvoorbeeld. Of over de melker die nu stilstond omdat hij Cherubijn had horen roepen en gebakken aardappels rook. Cherubijn, die de reactie van de melker door het open raam had gezien, besefte dat de melker honger had en riep ook hem. De melker toonde geen spoor van bedeesdheid. Hij voelde zich bij ons thuis. Hij nam een bord vol aardappels en at met smaak.

De marmot moest niets hebben van gebakken aardappels. Hij toonde geen enkele belangstelling voor de bruine korstjes die ik hem toewierp. Hij hupte de weg over en deed zich in de wei te goed aan klaverblad en avondgras.

De melker was iemand die de hele dag tegen zichzelf praatte, omdat hij tegen niemand anders wat te zeggen had. Nu at hij alleen maar en liet het praten over aan Cherubijn en mij.

Veel hadden wij ook niet te zeggen. Daarom bleef het stil. Dat hoort zo wanneer heel gewone mensen eten. Ze horen met hun stilte God te danken.

Wij waren tevreden. Dat lag minder aan God, maar meer aan de aardappels en aan het weer.

Na het eten liep de melker terug naar de wei, beklopte de koeien aan alle kanten. Het had iets met zijn of hun spijsvertering te maken. Later doodde hij zijn tijd weer met rondjes te lopen over het vochtige avondgras.