Fleurs du Mal Magazine

De Colombiaanse schrijver Gabriel García Márquez is vandaag (17 april 2014) overleden in zijn huis in Mexico-Stad. Dit hebben de Mexicaanse media gemeld.

De Colombiaanse schrijver Gabriel García Márquez is vandaag (17 april 2014) overleden in zijn huis in Mexico-Stad. Dit hebben de Mexicaanse media gemeld.

García Márquez werd op 6 maart 1927 geboren in Aracataca in Colombia, maar woonde de laatste jaren in Mexico.

In maart werd hij in een ziekenhuis opgenomen met een longontsteking. Na een week mocht hij weer naar huis. García Márquez laat een vrouw en twee zonen na.

Márquez was, behalve publicist, ook journalist en politiek activist. Hij kreeg vooral grote internationale roem met zijn boeken Honderd jaar eenzaamheid (1967) en Liefde in tijden van Cholera (1985).

In 1982 kreeg hij de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: BOOKS, In Memoriam

The Sorrows of Young Werther (28) by J.W. von Goethe ♦AUGUST 15. ♦ There can be no doubt that in this world nothing is so indispensable as love. I observe that Charlotte could not lose me without a pang, and the very children have but one wish; that is, that I should visit them again to-morrow. I went this afternoon to tune Charlotte’s piano. But I could not do it, for the little ones insisted on my telling them a story; and Charlotte herself urged me to satisfy them. I waited upon them at tea, and they are now as fully contented with me as with Charlotte; and I told them my very best tale of the princess who was waited upon by dwarfs. I improve myself by this exercise, and am quite surprised at the impression my stories create. If I sometimes invent an incident which I forget upon the next narration, they remind one directly that the story was different before; so that I now endeavour to relate with exactness the same anecdote in the same monotonous tone, which never changes. I find by this, how much an author injures his works by altering them, even though they be improved in a poetical point of view. The first impression is readily received. We are so constituted that we believe the most incredible things; and, once they are engraved upon the memory, woe to him who would endeavour to efface them.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

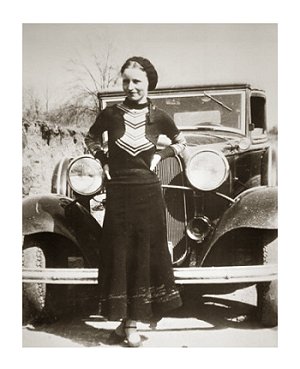

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker

(1910 – 1934)

The story of “Suicide Sal”

We each of us have a good “alibi”

For being down here in the “joint”

But few of them really are justified

If you get right down to the point.

You’ve heard of a woman’s glory

Being spent on a “downright cur”

Still you can’t always judge the story

As true, being told by her.

As long as I’ve stayed on this “island”

And heard “confidence tales” from each “gal”

Only one seemed interesting and truthful-

The story of “Suicide Sal”.

Now “Sal” was a gal of rare beauty,

Though her features were coarse and tough;

She never once faltered from duty

To play on the “up and up”.

“Sal” told me this tale on the evening

Before she was turned out “free”

And I’ll do my best to relate it

Just as she told it to me:

I was born on a ranch in Wyoming;

Not treated like Helen of Troy,

I was taught that “rods were rulers”

And “ranked” as a greasy cowboy.

Then I left my old home for the city

To play in its mad dizzy whirl,

Not knowing how little of pity

It holds for a country girl.

There I fell for “the line” of a “henchman”

A “professional killer” from “Chi”

I couldn’t help loving him madly,

For him even I would die.

One year we were desperately happy

Our “ill gotten gains” we spent free,

I was taught the ways of the “underworld”

Jack was just like a “god” to me.

I got on the “F.B.A.” payroll

To get the “inside lay” of the “job”

The bank was “turning big money”!

It looked like a “cinch for the mob”.

Eighty grand without even a “rumble”-

Jack was last with the “loot” in the door,

When the “teller” dead-aimed a revolver

From where they forced him to lie on the floor.

I knew I had only a moment-

He would surely get Jack as he ran,

So I “staged” a “big fade out” beside him

And knocked the forty-five out of his hand.

They “rapped me down big” at the station,

And informed me that I’d get the blame

For the “dramatic stunt” pulled on the “teller”

Looked to them, too much like a “game”.

The “police” called it a “frame-up”

Said it was an “inside job”

But I steadily denied any knowledge

Or dealings with “underworld mobs”.

The “gang” hired a couple of lawyers,

The best “fixers” in any mans town,

But it takes more than lawyers and money

When Uncle Sam starts “shaking you down”.

I was charged as a “scion of gangland”

And tried for my wages of sin,

The “dirty dozen” found me guilty-

From five to fifty years in the pen.

I took the “rap” like good people,

And never one “squawk” did I make

Jack “dropped himself” on the promise

That we make a “sensational break”.

Well, to shorten a sad lengthy story,

Five years have gone over my head

Without even so much as a letter-

At first I thought he was dead.

But not long ago I discovered;

From a gal in the joint named Lyle,

That Jack and his “moll” had “got over”

And were living in true “gangster style”.

If he had returned to me sometime,

Though he hadn’t a cent to give

I’d forget all the hell that he’s caused me,

And love him as long as I lived.

But there’s no chance of his ever coming,

For he and his moll have no fears

But that I will die in this prison,

Or “flatten” this fifty years.

Tommorow I’ll be on the “outside”

And I’ll “drop myself” on it today,

I’ll “bump ’em if they give me the “hotsquat”

On this island out here in the bay…

The iron doors swung wide next morning

For a gruesome woman of waste,

Who at last had a chance to “fix it”

Murder showed in her cynical face.

Not long ago I read in the paper

That a gal on the East Side got “hot”

And when the smoke finally retreated,

Two of gangdom were found “on the spot”.

It related the colorful story

Of a “jilted gangster gal”

Two days later, a “sub-gun” ended

The story of “Suicide Sal”.

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker (October 1, 1910 – May 23, 1934) and Clyde Chestnut Barrow (March 24, 1909 – May 23, 1934) were well-known (as Bonnie & Clyde) American outlaws and bankrobbers. They were both killed in a police ambush on May 23, 1934. Bonnie Parker wrote most of her poems, while in jail, in a little notebook she had obtained from The First National Bank of Burkburnett, Texas.

Bonnie Parker poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Suicide, Western Fiction

Hans Hermans photos: Island (Terschelling) I

hanshermans©2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Dutch Landscapes, Hans Hermans Photos, Photography

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (25)

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (25)

♦ Grijze muren ♦

Met een rotvaart, alsof hij door een kat achterna werd gezeten, schoot een grijze muis door de voordeur naar binnen.

`Nou krijgen we het helemaal’, riep Bas verbouwereerd uit. `Hij komt al net zo binnen als de eerste zwarte en de eerste witte muizen! Herejee, zouden er ook nog rode, groene en gele muizen zijn?’

De cafébezoekers keken even op, maar leken de grijze muis wel aardig te vinden en gingen door met het weinige wat ze normaal rond deze tijd deden: drinken en ouwehoeren.

De muis schoot regelrecht op de bar af en verborg zich in een uitgevreten hoekje. Daar bleef hij zitten bibberen.

Bas boog zich naar de muis toe.

`Je hoeft niet bang te zijn’, zei hij bemoedigend. `Hier doet niemand je wat. Daar zorg ik wel voor.’

`Als je wist waar ik vandaan kwam,’ zei de muis, met een accent dat verried dat hij van ver kwam, `dan zou je weten waarom ik bang ben.’ Toch bibberde hij al wat minder.

Bas pakte het diertje op en bekeek de muis vol verwondering. Het was een exemplaar van een slanker soort dan die tot nu toe zijn café bewoonden, hoewel hij een dikke, grijze vacht had die zacht was als velours. En zijn staart was niet zo naakt als bij de andere rassen, maar dik behaard en eindigend in een pluim. Hij had iets van een eekhoorntje. Het was de mooiste muis die Bas ooit had gezien.

`Wie doet je wat?’ vroeg Bas.

`De andere muizen’, zei de grijze schuchter. `De zwarten en de witten. Ze pesten ons.’

`Hebben ze daar een reden voor?’ vroeg Bas, die het nauwelijks kon geloven.

`We zijn anders en we zijn met veel minder’, zei de grijze. `Daarom kunnen ze ons makkelijk aan.’

`Je wilt toch niet zeggen dat andere muizen jullie lastigvallen omdat jullie zwakker zijn?’ zei Bas, bijna kwaad omdat het hem zo onwaarschijnlijk leek. `Het lijkt akelig veel op het gedrag van mensen.’

`Je denkt toch niet dat muizen anders of beter zijn?’ zei de grijze.

`Ik heb het toch altijd gehoopt’, zei Bas teleurgesteld. Hij kwam er steeds meer achter hoe verkeerd hij de muizenwereld had beoordeeld. Misschien kwam het doordat ze zo klein waren dat ze aardiger leken dan mensen, maar onder elkaar bleken ze net zo bloeddorstig en kwaadaardig te zijn.

`Wij grijze muizen trekken altijd aan het kortste eind’, zei de grijze.

`Dan moet je leren je te verweren. Je weet toch dat het leven een gevecht om het bestaan is?’

`We zijn met zo weinig dat we ons nauwelijks kunnen verweren. Ze jagen ons overal op. Wij krijgen alleen de slechtste plekken. Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor de lol van het ene huis naar het andere hol! Ik zou ook liever in een kroeg, een slagerswinkel of een bakkerij wonen. Een gewone zolder of kelder zou ik al heel geschikt vinden.’

`Dan bezet je toch zo’n pand’, zei Bas.

`We zijn niet met genoeg om het echt te durven.’

`Fokken jullie dan minder dan de witten en de zwarten? Als ik zie hoe snel dat volkje zich uitbreidt, dan verbaast het me dat de hele wereld nog niet is kaalgevreten.’

`We krijgen niet de kans om sterk te worden’, zei de grijze. `Ziektes, daar begint het al mee. We leven op de rotste plekken en we krijgen nooit fatsoenlijk te eten. Dat dunt ons volkje aardig uit. Wij grijze muizen hebben een leven van niks. We mogen nog van geluk spreken dat we niet de stad uit gelazerd zijn.’

`Dat kunnen ze toch niet doen’, zei Bas. `Zo hard kunnen andere muizen niet zijn.’

`Reken maar van wel. De zwarten en witten tolereren ons, omdat ze ons nodig hebben. Ze komen ons vragen als er gevaarlijke of vuile karweitjes zijn op te knappen. Zo hebben we laatst dat nieuwe Holiday Hotel bezet. Na maanden de zaak te hebben verkend en toen we door schade en schande te weten waren gekomen waar de vallen en de gifbakjes stonden, mochten we dat aan de zwarte muizen doorvertellen en oprotten. Wij waren niet meer nodig, terwijl wij de kastanjes uit het vuur hadden gehaald. Tientallen van ons zijn omgekomen bij de verovering van dat terrein. Mijn eigen kinderen heb ik gezien in vallen, de koppen ingeslagen. Anderen hebben dagen liggen creperen met het gif in hun lijf.’

`Spijtig’, zei Bas ontdaan. `Dat muizen elkaar het leven zo ondraaglijk maken.’

`En dan moet je weten wat voor een leven we in dat hotel hebben gehad’, zei de grijze muis. `In de paar maanden dat we er zijn geweest, hebben we niets anders gedaan dan vreten. Je hoefde er niets voor te doen. De duurste diners kieperen ze er zo in de vuilnisbak.’

`Daar moeten die patsers de zweep voor krijgen’, zei Bas. `Het is godgeklaagd. Van wat zij wegmieteren, zouden heel wat lui kunnen bestaan. En dan hoor je nog wel eens zeggen dat er honger in de wereld is.’

`Heb jij wat te eten voor me?’

`Ik kamp hier al lang met overbevolking,’ zei Bas, `maar voor één keertje wil ik je wel helpen.’

Hij was nog niet uitgesproken of de grijze was al weg.

`Ik haal mijn familie even op’, riep hij, nog voordat hij de deur uit schoot.

Daar schrok Bas toch wel van. Met hoeveel zouden ze terugkomen? Was het mogelijk nog meer kostgangers te bergen dan hij nu al in huis had?

Kaspar, de forse stamvader van de zwarte kolonie, kwam naar hem toe en keek hem vuil aan.

`Aan wat voor avontuur begin je nou weer?’ vroeg hij nijdig. `Vind je het nog niet welletjes? Moeten die grijze lummels er ook nog bij, nadat de witte muizen hier al de hele zaak hebben bedorven?’

Met lede ogen zag Kaspar aan hoe de grijze muis kwam binnenrennen, aan het hoofd van een volkje van wel dertig stuks, vooral kleintjes, en allemaal even fraai en grijs en met zo’n aardig pluimstaartje.

`Hoe meer ik het gevoel krijg dat ik door muizen word gebruikt, hoe beter ik je bezwaren aanvoel’, zei Bas. `Maar ik kan hen niet weigeren. Zou ik hen er niet inlaten, dan zou ik jullie er allemaal moeten uitgooien. Zwarte muizen zijn me niet liever dan witte of grijze.’

`Als jij ons er niet uit trapt, dan gaan we zelf wel weg’, zei Kaspar kwaad. `Dan zoeken we wel een ander plekje, waar we onszelf kunnen zijn. Ik wil niks met dat grijze gebroed te maken hebben.’

Vol walging zag Kaspar hoe Bas het groepje grijze muizen op een schotel kaas trakteerde. De diertjes vielen er zo hongerig op aan dat wel duidelijk was dat ze in dagen niet hadden gegeten.

`Ze vreten nog onbeschoft ook, de schrokkers’, zei Kaspar venijnig. `Ze zijn niet opgevoed.’

`Dat moet jij nodig zeggen’, stoof Bas op. `Kijk jij maar eens naar jouw eigen zwarte muisjes, daar bij de bloempot. Die heb jij toch opgevoed!’

Niet wetend wat ze deden, vraten de jonge muizen aan de critolis. Een paar hadden de stengel omgebogen en vraten de meeldraden uit de bloem, wat de plant pijnlijke rillingen bezorgde.

`Laat dat, rotzakken!’ riep Bas. Hij gooide een bierviltje naar de onverlaten. Helaas trof het viltje niet de muizen maar de knop van de critolis die, hevig geprikkeld, ogenblikkelijk tevoorschijn kwam, wachtend op meer liefkozingen, maar Bas vond dat ze haar portie wel had gehad.

Ton van Reen: Katapult (25)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: - Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam, Reen, Ton van

The Sorrows of Young Werther (27) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 12. ♦ Certainly Albert is the best fellow in the world. I had a strange scene with him yesterday. I went to take leave of him; for I took it into my head to spend a few days in these mountains, from where I now write to you. As I was walking up and down his room, my eye fell upon his pistols. “Lend me those pistols,” said I, “for my journey.” “By all means,” he replied, “if you will take the trouble to load them; for they only hang there for form.” I took down one of them; and he continued, “Ever since I was near suffering for my extreme caution, I will have nothing to do with such things.” I was curious to hear the story. “I was staying,” said he, “some three months ago, at a friend’s house in the country. I had a brace of pistols with me, unloaded; and I slept without any anxiety. One rainy afternoon I was sitting by myself, doing nothing, when it occurred to me I do not know how that the house might be attacked, that we might require the pistols, that we might in short, you know how we go on fancying, when we have nothing better to do. I gave the pistols to the servant, to clean and load. He was playing with the maid, and trying to frighten her, when the pistol went off–God knows how!–the ramrod was in the barrel; and it went straight through her right hand, and shattered the thumb. I had to endure all the lamentation, and to pay the surgeon’s bill; so, since that time, I have kept all my weapons unloaded. But, my dear friend, what is the use of prudence? We can never be on our guard against all possible dangers.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (27) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 12. ♦ Certainly Albert is the best fellow in the world. I had a strange scene with him yesterday. I went to take leave of him; for I took it into my head to spend a few days in these mountains, from where I now write to you. As I was walking up and down his room, my eye fell upon his pistols. “Lend me those pistols,” said I, “for my journey.” “By all means,” he replied, “if you will take the trouble to load them; for they only hang there for form.” I took down one of them; and he continued, “Ever since I was near suffering for my extreme caution, I will have nothing to do with such things.” I was curious to hear the story. “I was staying,” said he, “some three months ago, at a friend’s house in the country. I had a brace of pistols with me, unloaded; and I slept without any anxiety. One rainy afternoon I was sitting by myself, doing nothing, when it occurred to me I do not know how that the house might be attacked, that we might require the pistols, that we might in short, you know how we go on fancying, when we have nothing better to do. I gave the pistols to the servant, to clean and load. He was playing with the maid, and trying to frighten her, when the pistol went off–God knows how!–the ramrod was in the barrel; and it went straight through her right hand, and shattered the thumb. I had to endure all the lamentation, and to pay the surgeon’s bill; so, since that time, I have kept all my weapons unloaded. But, my dear friend, what is the use of prudence? We can never be on our guard against all possible dangers.

However,”–now, you must know I can tolerate all men till they come to “however;”–for it is self-evident that every universal rule must have its exceptions. But he is so exceedingly accurate, that, if he only fancies he has said a word too precipitate, or too general, or only half true, he never ceases to qualify, to modify, and extenuate, till at last he appears to have said nothing at all. Upon this occasion, Albert was deeply immersed in his subject: I ceased to listen to him, and became lost in reverie. With a sudden motion, I pointed the mouth of the pistol to my forehead, over the right eye. “What do you mean?” cried Albert, turning back the pistol. “It is not loaded,” said I. “And even if not,” he answered with impatience, “what can you mean? I cannot comprehend how a man can be so mad as to shoot himself, and the bare idea of it shocks me.”

“But why should any one,” said I, “in speaking of an action, venture to pronounce it mad or wise, or good or bad? What is the meaning of all this? Have you carefully studied the secret motives of our actions? Do you understand–can you explain the causes which occasion them, and make them inevitable? If you can, you will be less hasty with your decision.”

“But you will allow,” said Albert; “that some actions are criminal, let them spring from whatever motives they may.” I granted it, and shrugged my shoulders.

“But still, my good friend,” I continued, “there are some exceptions here too. Theft is a crime; but the man who commits it from extreme poverty, with no design but to save his family from perishing, is he anobject of pity, or of punishment? Who shall throw the first stone at a husband, who, in the heat of just resentment, sacrifices his faithless wife and her perfidious seducer? or at the young maiden, who, in her weak hour of rapture, forgets herself in the impetuous joys of love?

Even our laws, cold and cruel as they are, relent in such cases, and withhold their punishment.”

“That is quite another thing,” said Albert; “because a man under the influence of violent passion loses all power of reflection, and is regarded as intoxicated or insane.”

“That is quite another thing,” said Albert; “because a man under the influence of violent passion loses all power of reflection, and is regarded as intoxicated or insane.”

“Oh! you people of sound understandings,” I replied, smiling, “are ever ready to exclaim ‘Extravagance, and madness, and intoxication!’ You moral men are so calm and so subdued! You abhor the drunken man, and detest the extravagant; you pass by, like the Levite, and thank God, like the Pharisee, that you are not like one of them. I have been more than once intoxicated, my passions have always bordered on extravagance: I am not ashamed to confess it; for I have learned, by my own experience, that all extraordinary men, who have accomplished great and astonishing actions, have ever been decried by the world as drunken or insane. And in private life, too, is it not intolerable that no one can undertake the execution of a noble or generous deed, without giving rise to the exclamation that the doer is intoxicated or mad? Shame upon you, ye sages!”

“This is another of your extravagant humours,” said Albert: “you always exaggerate a case, and in this matter you are undoubtedly wrong; for we were speaking of suicide, which you compare with great actions, when it is impossible to regard it as anything but a weakness. It is much easier to die than to bear a life of misery with fortitude.”

I was on the point of breaking off the conversation, for nothing puts me so completely out of patience as the utterance of a wretched commonplace when I am talking from my inmost heart. However, I composed myself, for I had often heard the same observation with sufficient vexation; and I answered him, therefore, with a little warmth, “You call this a weakness–beware of being led astray by appearances. When a nation, which has long groaned under the intolerable yoke of a tyrant, rises at last and throws off its chains, do you call that weakness? The man who, to rescue his house from the flames, finds his physical strength redoubled, so that he lifts burdens with ease, which, in the absence of excitement, he could scarcely move; he who, under the rage of an insult, attacks and puts to flight half a score of his enemies, are such persons to be called weak? My good friend, if resistance be strength, how can the highest degree of resistance be a weakness?”

Albert looked steadfastly at me, and said, “Pray forgive me, but I do not see that the examples you have adduced bear any relation to the question.” “Very likely,” I answered; “for I have often been told that my style of illustration borders a little on the absurd. But let us see if we cannot place the matter in another point of view, by inquiring what can be a man’s state of mind who resolves to free himself from the burden of life,–a burden often so pleasant to bear,–for we cannot otherwise reason fairly upon the subject.

“Human nature,” I continued, “has its limits. It is able to endure a certain degree of joy, sorrow, and pain, but becomes annihilated as soon as this measure is exceeded. The question, therefore, is, not whether a man is strong or weak, but whether he is able to endure the measure of his sufferings. The suffering may be moral or physical; and in my opinion it is just as absurd to call a man a coward who destroys himself, as to call a man a coward who dies of a malignant fever.”

“Paradox, all paradox!” exclaimed Albert. “Not so paradoxical as you imagine,” I replied. “You allow that we designate a disease as mortal when nature is so severely attacked, and her strength so far exhausted, that she cannot possibly recover her former condition under any change that may take place.

“Now, my good friend, apply this to the mind; observe a man in his natural, isolated condition; consider how ideas work, and how impressions fasten on him, till at length a violent passion seizes him, destroying all his powers of calm reflection, and utterly ruining him.

“It is in vain that a man of sound mind and cool temper understands the condition of such a wretched being, in vain he counsels him. He can no more communicate his own wisdom to him than a healthy man can instil his strength into the invalid, by whose bedside he is seated.”

Albert thought this too general. I reminded him of a girl who had drowned herself a short time previously, and I related her history. She was a good creature, who had grown up in the narrow sphere of household industry and weekly appointed labour; one who knew no pleasure beyond indulging in a walk on Sundays, arrayed in her best attire, accompanied by her friends, or perhaps joining in the dance now and then at some festival, and chatting away her spare hours with a neighbour, discussing the scandal or the quarrels of the village, trifles sufficient to occupy her heart. At length the warmth of her nature is influenced by certain new and unknown wishes. Inflamed by the flatteries of men, her former pleasures become by degrees insipid, till at length she meets with a youth to whom she is attracted by an indescribable feeling; upon him she now rests all her hopes; she forgets the world around her; she sees, hears, desires nothing but him, and him only. He alone occupies all her thoughts. Uncorrupted by the idle indulgence of an enervating vanity, her affection moving steadily toward its object, she hopes to become his, and to realise, in an everlasting union with him, all that happiness which she sought, all that bliss for which she longed. His repeated promises confirm her hopes: embraces and endearments, which increase the ardour of her desires, overmaster her soul. She floats in a dim, delusive anticipation of her happiness; and her feelings become excited to their utmost tension. She stretches out her arms finally to embrace the object of all her wishes and her lover forsakes her. Stunned and bewildered, she stands upon a precipice. All is darkness around her. No prospect, no hope, no consolation–forsaken by him in whom her existence was centred! She sees nothing of the wide world before her, thinks nothing of the many individuals who might supply the void in her heart; she feels herself deserted, forsaken by the world; and, blinded and impelled by the agony which wrings her soul, she plunges into the deep, to end her sufferings in the broad embrace of death. See here, Albert, the history of thousands; and tell me, is not this a case of physical infirmity? Nature has no way to escape from the labyrinth: her powers are exhausted: she can contend no longer, and the poor soul must die.

Albert thought this too general. I reminded him of a girl who had drowned herself a short time previously, and I related her history. She was a good creature, who had grown up in the narrow sphere of household industry and weekly appointed labour; one who knew no pleasure beyond indulging in a walk on Sundays, arrayed in her best attire, accompanied by her friends, or perhaps joining in the dance now and then at some festival, and chatting away her spare hours with a neighbour, discussing the scandal or the quarrels of the village, trifles sufficient to occupy her heart. At length the warmth of her nature is influenced by certain new and unknown wishes. Inflamed by the flatteries of men, her former pleasures become by degrees insipid, till at length she meets with a youth to whom she is attracted by an indescribable feeling; upon him she now rests all her hopes; she forgets the world around her; she sees, hears, desires nothing but him, and him only. He alone occupies all her thoughts. Uncorrupted by the idle indulgence of an enervating vanity, her affection moving steadily toward its object, she hopes to become his, and to realise, in an everlasting union with him, all that happiness which she sought, all that bliss for which she longed. His repeated promises confirm her hopes: embraces and endearments, which increase the ardour of her desires, overmaster her soul. She floats in a dim, delusive anticipation of her happiness; and her feelings become excited to their utmost tension. She stretches out her arms finally to embrace the object of all her wishes and her lover forsakes her. Stunned and bewildered, she stands upon a precipice. All is darkness around her. No prospect, no hope, no consolation–forsaken by him in whom her existence was centred! She sees nothing of the wide world before her, thinks nothing of the many individuals who might supply the void in her heart; she feels herself deserted, forsaken by the world; and, blinded and impelled by the agony which wrings her soul, she plunges into the deep, to end her sufferings in the broad embrace of death. See here, Albert, the history of thousands; and tell me, is not this a case of physical infirmity? Nature has no way to escape from the labyrinth: her powers are exhausted: she can contend no longer, and the poor soul must die.

“Shame upon him who can look on calmly, and exclaim, ‘The foolish girl! she should have waited; she should have allowed time to wear off the impression; her despair would have been softened, and she would have found another lover to comfort her.’ One might as well say, ‘The fool, to die of a fever! why did he not wait till his strength was restored, till his blood became calm? all would then have gone well, and he would have been alive now.'”

Albert, who could not see the justice of the comparison, offered some further objections, and, amongst others, urged that I had taken the case of a mere ignorant girl. But how any man of sense, of more enlarged views and experience, could be excused, he was unable to comprehend. “My friend!” I exclaimed, “man is but man; and, whatever be the extent of his reasoning powers, they are of little avail when passion rages within, and he feels himself confined by the narrow limits of nature.

It were better, then–but we will talk of this some other time,” I said, and caught up my hat. Alas! my heart was full; and we parted without conviction on either side. How rarely in this world do men understand each other!

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was ♦ A certain father had two sons, the elder of whom was smart and sensible, and could do everything, but the younger was stupid and could neither learn nor understand anything, and when people saw him they said, “There’s a fellow who will give his father some trouble!” When anything had to be done, it was always the elder who was forced to do it; but if his father bade him fetch anything when it was late, or in the night-time, and the way led through the churchyard, or any other dismal place, he answered “Oh, no, father, I’ll not go there, it makes me shudder!” for he was afraid. Or when stories were told by the fire at night which made the flesh creep, the listeners sometimes said “Oh, it makes us shudder!” The younger sat in a corner and listened with the rest of them, and could not imagine what they could mean. “They are always saying ‘it makes me shudder, it makes me shudder!’ It does not make me shudder,” thought he. “That, too, must be an art of which I understand nothing.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was ♦ A certain father had two sons, the elder of whom was smart and sensible, and could do everything, but the younger was stupid and could neither learn nor understand anything, and when people saw him they said, “There’s a fellow who will give his father some trouble!” When anything had to be done, it was always the elder who was forced to do it; but if his father bade him fetch anything when it was late, or in the night-time, and the way led through the churchyard, or any other dismal place, he answered “Oh, no, father, I’ll not go there, it makes me shudder!” for he was afraid. Or when stories were told by the fire at night which made the flesh creep, the listeners sometimes said “Oh, it makes us shudder!” The younger sat in a corner and listened with the rest of them, and could not imagine what they could mean. “They are always saying ‘it makes me shudder, it makes me shudder!’ It does not make me shudder,” thought he. “That, too, must be an art of which I understand nothing.”

Now it came to pass that his father said to him one day “Hearken to me, thou fellow in the corner there, thou art growing tall and strong, and thou too must learn something by which thou canst earn thy living. Look how thy brother works, but thou dost not even earn thy salt.” – “Well, father,” he replied, “I am quite willing to learn something – indeed, if it could but be managed, I should like to learn how to shudder. I don’t understand that at all yet.” The elder brother smiled when he heard that, and thought to himself, “Good God, what a blockhead that brother of mine is! He will never be good for anything as long as he lives. He who wants to be a sickle must bend himself betimes.” The father sighed, and answered him “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, but thou wilt not earn thy bread by that.”

Soon after this the sexton2 came to the house on a visit, and the father bewailed his trouble, and told him how his younger son was so backward in every respect that he knew nothing and learnt nothing. “Just think,” said he, “when I asked him how he was going to earn his bread, he actually wanted to learn to shudder.” – “If that be all,” replied the sexton, “he can learn that with me. Send him to me, and I will soon polish him.” The father was glad to do it, for he thought, “It will train the boy a little.” The sexton therefore took him into his house, and he had to ring the bell. After a day or two, the sexton awoke him at midnight, and bade him arise and go up into the church tower and ring the bell. “Thou shalt soon learn what shuddering is,” thought he, and secretly went there before him; and when the boy was at the top of the tower and turned round, and was just going to take hold of the bell rope, he saw a white figure standing on the stairs opposite the sounding hole. “Who is there?” cried he, but the figure made no reply, and did not move or stir. “Give an answer,” cried the boy, “or take thy self off, thou hast no business here at night.” The sexton, however, remained standing motionless that the boy might think he was a ghost. The boy cried a second time, “What do you want here? – speak if thou art an honest fellow, or I will throw thee down the steps!” The sexton thought, “he can’t intend to be as bad as his words,” uttered no sound and stood as if he were made of stone. Then the boy called to him for the third time, and as that was also to no purpose, he ran against him and pushed the ghost down the stairs, so that it fell down ten steps and remained lying there in a corner. Thereupon he rang the bell, went home, and without saying a word went to bed, and fell asleep. The sexton’s wife waited a long time for her husband, but he did not come back. At length she became uneasy, and wakened the boy, and asked, “Dost thou not know where my husband is? He climbed up the tower before thou didst.” – “No, I don’t know,” replied the boy, “but some one was standing by the sounding hole on the other side of the steps, and as he would neither give an answer nor go away, I took him for a scoundrel, and threw him downstairs, just go there and you will see if it was he. I should be sorry if it were.” The woman ran away and found her husband, who was lying moaning in the corner, and had broken his leg.

She carried him down, and then with loud screams she hastened to the boy’s father. “Your boy,” cried she, “has been the cause of a great misfortune! He has thrown my husband down the steps and made him break his leg. Take the good-for-nothing fellow away from our house.” The father was terrified, and ran thither and scolded the boy. “What wicked tricks are these?” said he, “the Devil must have put this into thy head.” – “Father,” he replied, “do listen to me. I am quite innocent. He was standing there by night like one who is intending to do some evil. I did not know who it was, and I entreated him three times either to speak or to go away.” – “Ah,” said the father, “I have nothing but unhappiness with you. Go out of my sight. I will see thee no more.” – “Yes, father, right willingly, wait only until it is day. Then will I go forth and learn how to shudder, and then I shall, at any rate, understand one art which will support me.” – “Learn what thou wilt,” spake the father, “it is all the same to me. Here are fifty thalers3 for thee. Take these and go into the wide world, and tell no one from whence thou comest, and who is thy father, for I have reason to be ashamed of thee.” – “Yes, father, it shall be as you will. If you desire nothing more than that, I can easily keep it in mind.”

She carried him down, and then with loud screams she hastened to the boy’s father. “Your boy,” cried she, “has been the cause of a great misfortune! He has thrown my husband down the steps and made him break his leg. Take the good-for-nothing fellow away from our house.” The father was terrified, and ran thither and scolded the boy. “What wicked tricks are these?” said he, “the Devil must have put this into thy head.” – “Father,” he replied, “do listen to me. I am quite innocent. He was standing there by night like one who is intending to do some evil. I did not know who it was, and I entreated him three times either to speak or to go away.” – “Ah,” said the father, “I have nothing but unhappiness with you. Go out of my sight. I will see thee no more.” – “Yes, father, right willingly, wait only until it is day. Then will I go forth and learn how to shudder, and then I shall, at any rate, understand one art which will support me.” – “Learn what thou wilt,” spake the father, “it is all the same to me. Here are fifty thalers3 for thee. Take these and go into the wide world, and tell no one from whence thou comest, and who is thy father, for I have reason to be ashamed of thee.” – “Yes, father, it shall be as you will. If you desire nothing more than that, I can easily keep it in mind.”

When day dawned, therefore, the boy put his fifty thalers into his pocket, and went forth on the great highway, and continually said to himself, “If I could but shudder! If I could but shudder!” Then a man approached who heard this conversation which the youth was holding with himself, and when they had walked a little farther to where they could see the gallows, the man said to him, “Look, there is the tree where seven1 men have married the ropemaker’s daughter, and are now learning how to fly. Sit down below it, and wait till night comes, and you will soon learn how to shudder.” – “If that is all that is wanted,” answered the youth, “it is easily done; but if I learn how to shudder as fast as that, thou shalt have my fifty thalers. Just come back to me early in the morning.” Then the youth went to the gallows, sat down below it, and waited till evening came. And as he was cold, he lighted himself a fire, but at midnight the wind blew so sharply that in spite of his fire, he could not get warm. And as the wind knocked the hanged men against each other, and they moved backwards and forwards, he thought to himself “Thou shiverest below by the fire, but how those up above must freeze and suffer!” And as he felt pity for them, he raised the ladder, and climbed up, unbound one of them after the other, and brought down all seven. Then he stirred the fire, blew it, and set them all round it to warm themselves. But they sat there and did not stir, and the fire caught their clothes. So he said, “Take care, or I will hang you up again.” The dead men, however, did not hear, but were quite silent, and let their rags go on burning. On this he grew angry, and said, “If you will not take care, I cannot help you, I will not be burnt with you,” and he hung them up again each in his turn. Then he sat down by his fire and fell asleep, and the next morning the man came to him and wanted to have the fifty thalers, and said, “Well, dost thou know how to shudder?” – “No,” answered he, “how was I to get to know? Those fellows up there did not open their mouths, and were so stupid that they let the few old rags which they had on their bodies get burnt.” Then the man saw that he would not get the fifty thalers that day, and went away saying, “One of this kind has never come my way before.”

The youth likewise went his way, and once more began to mutter to himself, “Ah, if I could but shudder! Ah, if I could but shudder!” A waggoner who was striding behind him heard that and asked, “Who are you?” – “I don’t know,” answered the youth. Then the waggoner asked, “From whence comest thou?” – “I know not.” – “Who is thy father?” – “That I may not tell thee.” – “What is it that thou art always muttering between thy teeth.” – “Ah,” replied the youth, “I do so wish I could shudder, but no one can teach me how to do it.” – “Give up thy foolish chatter,” said the waggoner. “Come, go with me, I will see about a place for thee.” The youth went with the waggoner, and in the evening they arrived at an inn where they wished to pass the night. Then at the entrance of the room the youth again said quite loudly, “If I could but shudder! If I could but shudder!” The host who heard this, laughed and said, “If that is your desire, there ought to be a good opportunity for you here.” – “Ah, be silent,” said the hostess, “so many inquisitive persons have already lost their lives, it would be a pity and a shame if such beautiful eyes as these should never see the daylight again.” But the youth said, “However difficult it may be, I will learn it and for this purpose indeed have I journeyed forth.” He let the host have no rest, until the latter told him, that not far from thence stood a haunted castle where any one could very easily learn what shuddering was, if he would but watch in it for three nights. The King had promised that he who would venture should have his daughter to wife, and she was the most beautiful maiden the sun shone on. Great treasures likewise lay in the castle, which were guarded by evil spirits, and these treasures would then be freed, and would make a poor man rich enough. Already many men had gone into the castle, but as yet none had come out again. Then the youth went next morning to the King and said if he were allowed he would watch three nights in the haunted castle. The King looked at him, and as the youth pleased him, he said, “Thou mayest ask for three things to take into the castle with thee, but they must be things without life.” Then he answered, “Then I ask for a fire, a turning lathe, and a cutting-board with the knife.”

The King had these things carried into the castle for him during the day. When night was drawing near, the youth went up and made himself a bright fire in one of the rooms, placed the cutting-board and knife beside it, and seated himself by the turning-lathe. “Ah, if I could but shudder!” said he, “but I shall not learn it here either.” Towards midnight he was about to poke his fire, and as he was blowing it, something cried suddenly from one corner, “Au, miau! how cold we are!” – “You simpletons!” cried he, “what are you crying about? If you are cold, come and take a seat by the fire and warm yourselves.” And when he had said that, two great black cats came with one tremendous leap and sat down on each side of him, and looked savagely at him with their fiery eyes. After a short time, when they had warmed themselves, they said, “Comrade, shall we have a game at cards?” – “Why not?” he replied, “but just show me your paws.” Then they stretched out their claws. “Oh,” said he, “what long nails you have! Wait, I must first cut them for you.” Thereupon he seized them by the throats, put them on the cutting-board and screwed their feet fast. “I have looked at your fingers,” said he, “and my fancy for card-playing has gone,” and he struck them dead and threw them out into the water. But when he had made away with these two, and was about to sit down again by his fire, out from every hole and corner came black cats and black dogs with red-hot chains, and more and more of them came until he could no longer stir, and they yelled horribly, and got on his fire, pulled it to pieces, and tried to put it out. He watched them for a while quietly, but at last when they were going too far, he seized his cutting-knife, and cried, “Away with ye, vermin,” and began to cut them down. Part of them ran away, the others he killed, and threw out into the fish-pond. When he came back he fanned the embers of his fire again and warmed himself. And as he thus sat, his eyes would keep open no longer, and he felt a desire to sleep. Then he looked round and saw a great bed in the corner. “That is the very thing for me,” said he, and got into it. When he was just going to shut his eyes, however, the bed began to move of its own accord, and went over the whole of the castle. “That’s right,” said he, “but go faster.” Then the bed rolled on as if six horses were harnessed to it, up and down, over thresholds and steps, but suddenly hop, hop, it turned over upside down, and lay on him like a mountain.

The King had these things carried into the castle for him during the day. When night was drawing near, the youth went up and made himself a bright fire in one of the rooms, placed the cutting-board and knife beside it, and seated himself by the turning-lathe. “Ah, if I could but shudder!” said he, “but I shall not learn it here either.” Towards midnight he was about to poke his fire, and as he was blowing it, something cried suddenly from one corner, “Au, miau! how cold we are!” – “You simpletons!” cried he, “what are you crying about? If you are cold, come and take a seat by the fire and warm yourselves.” And when he had said that, two great black cats came with one tremendous leap and sat down on each side of him, and looked savagely at him with their fiery eyes. After a short time, when they had warmed themselves, they said, “Comrade, shall we have a game at cards?” – “Why not?” he replied, “but just show me your paws.” Then they stretched out their claws. “Oh,” said he, “what long nails you have! Wait, I must first cut them for you.” Thereupon he seized them by the throats, put them on the cutting-board and screwed their feet fast. “I have looked at your fingers,” said he, “and my fancy for card-playing has gone,” and he struck them dead and threw them out into the water. But when he had made away with these two, and was about to sit down again by his fire, out from every hole and corner came black cats and black dogs with red-hot chains, and more and more of them came until he could no longer stir, and they yelled horribly, and got on his fire, pulled it to pieces, and tried to put it out. He watched them for a while quietly, but at last when they were going too far, he seized his cutting-knife, and cried, “Away with ye, vermin,” and began to cut them down. Part of them ran away, the others he killed, and threw out into the fish-pond. When he came back he fanned the embers of his fire again and warmed himself. And as he thus sat, his eyes would keep open no longer, and he felt a desire to sleep. Then he looked round and saw a great bed in the corner. “That is the very thing for me,” said he, and got into it. When he was just going to shut his eyes, however, the bed began to move of its own accord, and went over the whole of the castle. “That’s right,” said he, “but go faster.” Then the bed rolled on as if six horses were harnessed to it, up and down, over thresholds and steps, but suddenly hop, hop, it turned over upside down, and lay on him like a mountain.

But he threw quilts and pillows up in the air, got out and said, “Now any one who likes, may drive,” and lay down by his fire, and slept till it was day. In the morning the King came, and when he saw him lying there on the ground, he thought the evil spirits had killed him and he was dead. Then said he, “After all it is a pity, he is a handsome man.” The youth heard it, got up, and said, “It has not come to that yet.” Then the King was astonished, but very glad, and asked how he had fared. “Very well indeed,” answered he; “one night is past, the two others will get over likewise.” Then he went to the innkeeper, who opened his eyes very wide, and said, “I never expected to see thee alive again! Hast thou learnt how to shudder yet?” – “No,” said he, “it is all in vain. If some one would but tell me.”

But he threw quilts and pillows up in the air, got out and said, “Now any one who likes, may drive,” and lay down by his fire, and slept till it was day. In the morning the King came, and when he saw him lying there on the ground, he thought the evil spirits had killed him and he was dead. Then said he, “After all it is a pity, he is a handsome man.” The youth heard it, got up, and said, “It has not come to that yet.” Then the King was astonished, but very glad, and asked how he had fared. “Very well indeed,” answered he; “one night is past, the two others will get over likewise.” Then he went to the innkeeper, who opened his eyes very wide, and said, “I never expected to see thee alive again! Hast thou learnt how to shudder yet?” – “No,” said he, “it is all in vain. If some one would but tell me.”

The second night he again went up into the old castle, sat down by the fire, and once more began his old song, “If I could but shudder.” When midnight came, an uproar and noise of tumbling about was heard; at first it was low, but it grew louder and louder. Then it was quiet for awhile, and at length with a loud scream, half a man came down the chimney and fell before him. “Hollo!” cried he, “another half belongs to this. This is too little!” Then the uproar began again, there was a roaring and howling, and the other half fell down likewise. “Wait,” said he, “I will just blow up the fire a little for thee.” When he had done that and looked round again, the two pieces were joined together, and a frightful man was sitting in his place. “That is no part of our bargain,” said the youth, “the bench is mine.” The man wanted to push him away; the youth, however, would not allow that, but thrust him off with all his strength, and seated himself again in his own place. Then still more men fell down, one after the other; they brought nine dead men’s legs and two skulls, and set them up and played at nine-pins with them. The youth also wanted to play and said “Hark you, can I join you?” – “Yes, if thou hast any money.” – “Money enough,” replied he, “but your balls are not quite round.” Then he took the skulls and put them in the lathe and turned them till they were round. “There, now, they will roll better!” said he. “Hurrah! Now it goes merrily!” He played with them and lost some of his money, but when it struck twelve, everything vanished from his sight. He lay down and quietly fell asleep. Next morning the King came to inquire after him. “How has it fared with you this time?” asked he. “I have been playing at nine-pins,” he answered, “and have lost a couple of hellers1.” – “Hast thou not shuddered then?” – “Eh, what?” said he, “I have made merry. If I did but know what it was to shudder!”

The third night he sat down again on his bench and said quite sadly, “If I could but shudder.” When it grew late, six tall men came in and brought a coffin. Then said he, “Ha, ha, that is certainly my little cousin, who died only a few days ago,” and he beckoned with his finger, and cried “Come, little cousin, come.” They placed the coffin on the ground, but he went to it and took the lid off, and a dead man lay therein. He felt his face, but it was cold as ice. “Stop,” said he, “I will warm thee a little,” and went to the fire and warmed his hand and laid it on the dead man’s face, but he remained cold. Then he took him out, and sat down by the fire and laid him on his breast and rubbed his arms that the blood might circulate again. As this also did no good, he thought to himself “When two people lie in bed together, they warm each other,” and carried him to the bed, covered him over and lay down by him. After a short time the dead man became warm too, and began to move. Then said the youth, “See, little cousin, have I not warmed thee?” The dead man, however, got up and cried, “Now will I strangle thee.” – “What!” said he, “is that the way thou thankest me? Thou shalt at once go into thy coffin again,” and he took him up, threw him into it, and shut the lid. Then came the six men and carried him away again. “I cannot manage to shudder,” said he. “I shall never learn it here as long as I live.”

Then a man entered who was taller than all others, and looked terrible. He was old, however, and had a long white beard. “Thou wretch,” cried he, “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, for thou shalt die.” – “Not so fast,” replied the youth. “If I am to die, I shall have to have a say in it.” – “I will soon seize thee,” said the fiend. “Softly, softly, do not talk so big. I am as strong as thou art, and perhaps even stronger.” – “We shall see,” said the old man. “If thou art stronger, I will let thee go – come, we will try.” Then he led him by dark passages to a smith’s forge, took an axe, and with one blow struck an anvil into the ground. “I can do better than that,” said the youth, and went to the other anvil. The old man placed himself near and wanted to look on, and his white beard hung down. Then the youth seized the axe, split the anvil with one blow, and struck the old man’s beard in with it. “Now I have thee,” said the youth. “Now it is thou who will have to die.” Then he seized an iron bar and beat the old man till he moaned and entreated him to stop, and he would give him great riches. The youth drew out the axe and let him go. The old man led him back into the castle, and in a cellar showed him three chests full of gold. “Of these,” said he, “one part is for the poor, the other for the king, the third is thine.” In the meantime it struck twelve, and the spirit disappeared; the youth, therefore, was left in darkness. “I shall still be able to find my way out,” said he, and felt about, found the way into the room, and slept there by his fire. Next morning the King came and said “Now thou must have learnt what shuddering is?” – “No,” he answered; “what can it be? My dead cousin was here, and a bearded man came and showed me a great deal of money down below, but no one told me what it was to shudder.” – “Then,” said the King, “thou hast delivered from the castle, and shalt marry my daughter.” – “That is all very well,” said he, “but still I do not know what it is to shudder.”

Then a man entered who was taller than all others, and looked terrible. He was old, however, and had a long white beard. “Thou wretch,” cried he, “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, for thou shalt die.” – “Not so fast,” replied the youth. “If I am to die, I shall have to have a say in it.” – “I will soon seize thee,” said the fiend. “Softly, softly, do not talk so big. I am as strong as thou art, and perhaps even stronger.” – “We shall see,” said the old man. “If thou art stronger, I will let thee go – come, we will try.” Then he led him by dark passages to a smith’s forge, took an axe, and with one blow struck an anvil into the ground. “I can do better than that,” said the youth, and went to the other anvil. The old man placed himself near and wanted to look on, and his white beard hung down. Then the youth seized the axe, split the anvil with one blow, and struck the old man’s beard in with it. “Now I have thee,” said the youth. “Now it is thou who will have to die.” Then he seized an iron bar and beat the old man till he moaned and entreated him to stop, and he would give him great riches. The youth drew out the axe and let him go. The old man led him back into the castle, and in a cellar showed him three chests full of gold. “Of these,” said he, “one part is for the poor, the other for the king, the third is thine.” In the meantime it struck twelve, and the spirit disappeared; the youth, therefore, was left in darkness. “I shall still be able to find my way out,” said he, and felt about, found the way into the room, and slept there by his fire. Next morning the King came and said “Now thou must have learnt what shuddering is?” – “No,” he answered; “what can it be? My dead cousin was here, and a bearded man came and showed me a great deal of money down below, but no one told me what it was to shudder.” – “Then,” said the King, “thou hast delivered from the castle, and shalt marry my daughter.” – “That is all very well,” said he, “but still I do not know what it is to shudder.”

Then the gold was brought up and the wedding celebrated; but howsoever much the young king loved his wife, and however happy he was, he still said always “If I could but shudder – if I could but shudder.” And at last she was angry at this. Her waiting-maid said, “I will find a cure for him; he shall soon learn what it is to shudder.” She went out to the stream which flowed through the garden, and had a whole bucketful of gudgeons brought to her. At night when the young king was sleeping, his wife was to draw the clothes off him and empty the bucketful of cold water with the gudgeons in it over him, so that the little fishes would sprawl about him. When this was done, he woke up and cried “Oh, what makes me shudder so? What makes me shudder so, dear wife? Ah! now I know what it is to shudder!”

THE END

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). This is the Brothers Grimm version of the story and in 1844 translated into English by Margarate Hunt. KHM1 004: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

De vergeten winter

Frank Pollet opgedragen, maart 2014

Bekeken door de zeef van geduld heeft tijd

hier geen heft. Zie beenbreek en ogentroost:

de lente gaat droog als naaldhout open.

Alsof ineens de zon zijn gedachten bezingt.

Regen laat zich lastig wegen, kent geen spijt

omdat men treurt om een verloren oogst.

Wijsjes met een vederlicht vibrato lopen

hoog op. Ze lijken wel bergdauw. Er klinkt

bezoeming als door hommels in het hoofd,

de dag tot aan de ogen diep in de lauwe inkt.

Bert Bevers

Ongepubliceerd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Hans Hermans photo: Buizerd

hanshermansphotos©2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Dutch Landscapes, Hans Hermans Photos

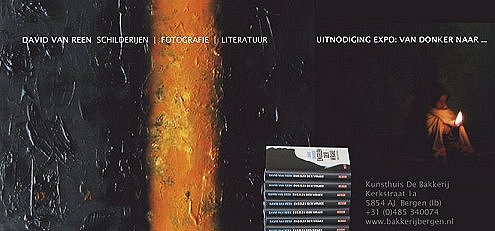

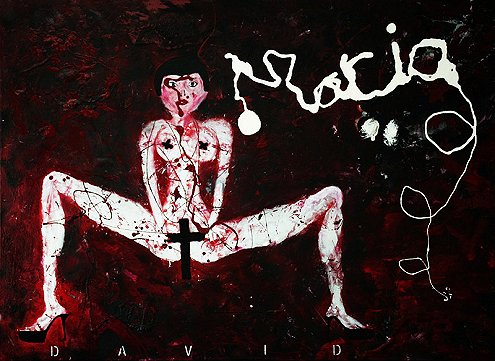

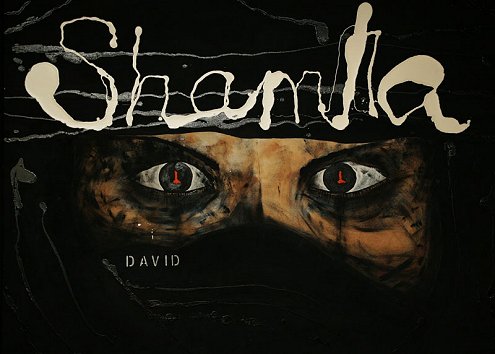

Expositie “Van Donker Naar Licht” 4 april tot 10 juni 2014

David van Reen | schilderijen, fotografie en literatuur

De Bakkerij, kunsthuis – Kerkstraat 1a –

5854 AJ Bergen (aan de Maas), Nederland

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, David van Reen Photos

Charles Guérin

(1873-1907)

La maison dort

La maison dort au coeur de quelque vieille ville

Où des dames s’en vont, lasses de bonnes oeuvres,

S’assoupir en suivant l’office de six heures,

Ville où le rouet gris de l’ennui se dévide.

Dans la cour un bassin où pleurent les eaux vives

D’avoir vu verdir les Tritons et d’être seules.

Et la maison laisse gémir les eaux jaseuses ;

Ses yeux sont noirs où s’avivaient jadis les vitres,

Et, vers le soir, les cuivres du soleil s’éteignent

Sur les plafonds tendus de terreuses dentelles

Qu’un coup de vent parfois tord comme des écharpes.

Les mites ont aimé dans les tentures ternes ;

Aussi, charme décoloré des chambres, charme

Des rêves qu’on a trop songés et qui se taisent.

Charles Guérin poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (24)

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (24)

`Je kunt wel zeggen dat ik vergeten was’, zei het vrouwtje. `Daarom heb ik in mijn laatste jaren zoveel gezopen. Ik had geen geld voor eten, ik gaf alles uit aan drank. Aan de roes. De roes is fijn. Als je dronken bent, voel je je weer als een kind dat nog veel van het leven verwacht. Alleen de kater moet je niet te vaak meemaken.’

Crazy schonk koffie in. Van de geur werden ze allemaal een beetje wakker.

David bleef slapen. Mireille luisterde naar zijn ademen. Hij zag er lief uit, zo. Hij had nu niets van het uitgekookte knaapje dat situaties aardig naar zijn hand kon zetten en heel gewiekst voordeel haalde uit het feit dat hij nog een kind was.

Crazy keek naar het plafond. Hij vroeg zich af wat er moest gebeuren. Voor het eerst zag hij dat het plafond, dat vroeger ooit wit was geweest, door rook en kookvocht zo was aangetast dat er een hele landkaart van bruine barsten in te zien was. Met een beetje fantasie kon hij soms de grenzen van bestaande landen ontdekken, maar het was vreemd Frankrijk aan IJsland te zien grenzen en de Noordpool in de hoogtelijntjes van Brazilië terug te vinden. De provincie Limburg leek een ontzagwekkende mogendheid, grenzend aan de lilliputlaars van Italië.

`Jullie moeten me nu begraven’, zei het vrouwtje. `Ik zie dat jullie vrede met elkaar hebben. En met mij. Dat is voor mij genoeg. Nu kan ik in alle rust van de wereld af. Van jullie verwacht ik dat jullie me een laatste rustplaats bezorgen.’

`Dat gaat zo makkelijk niet’, zei Albert bedachtzaam. `Je komt het kerkhof niet op zonder langs de doodgraver te komen. Hij woont bij de poort. Hij heeft een overlijdensattest nodig. Dat kan alleen een dokter afgeven.’

`Ik zal Hondewater laten komen’, zei Crazy. `Mijn huisarts. Hij woont twee deuren verder. Hij kan zo’n attest schrijven.’

Hij verliet de kamer. Hij was zo vlug terug met Hondewater, dat het leek of de man op hem had zitten wachten.

Hondewater was een al wat oudere, grof gebouwde man, een soort buldog in een mensenpak. In zijn blauwe ogen lag een kille blik. Met hem kwam een ijskoude stroom lucht de kamer binnen.

`Hondewater’, zei hij, om zich voor te stellen, en hij opende direct zijn tas. Hij keek nauwelijks naar wie er in het vertrek waren. Hij had alleen maar aandacht voor het dode vrouwtje op het vloerkleed en boog zich over haar heen.

`Ze is morsdood’, zei hij, ofschoon hij haar nog niet had aangeraakt. `Je zou dat ongedierte van haar moeten afhouden.’ Hij doelde op het vogeltje dat op haar voorhoofd zat. `Ik vind dat je hier beter moet stoken. Het is hier koud.’

`Dat is het nog maar net’, zei Mireille, zich zwak verdedigend. `Vanaf dat u binnen bent. Daarvoor was het warm.’

De man hoorde het niet of wilde het niet horen.

Crazy huiverde. Hij zag dat er zich kleine kristallen van dun ijs op de ruiten vormden. En ook op de glazen in de kast ontstonden sterretjes. Het verbaasde hem. Hoe kon het hier zo vlug koud worden, terwijl ze toch met zovelen in dit kleine kamertje waren?

David werd wakker van de kou. Half slapend kroop hij overeind en hij keek om zich heen om te zien waar hij was. Hij herkende de plek en was gerustgesteld. De korte tijd die hij had geslapen, had hem goedgedaan. Voor iemand die uit zijn slaap was gehaald, keek hij bijzonder helder uit zijn ogen.

Nu pas zag David het dode vrouwtje. Hij schrok. Hij kende haar.

`Ik wilde haar vaak goedendag zeggen’, zei hij, meer tegen zichzelf dan tegen wie ook. `Ik durfde niet. Ze zag me nooit. Ze keek over iedereen heen.’

`Kunnen we haar nu begraven?’ vroeg Crazy aan Hondewater.

`Als je betaalt. Dat maakt honderd piek.’

`Honderd piek?’ schrok Crazy. `Waarvoor?’

`Om me te betalen natuurlijk’, zei Hondewater. `Als je hebt betaald, schrijf ik het attest. Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niks ben gekomen?’

`Ze heeft geen cent’, huiverde Crazy. Zijn voeten waren ijskoud.

`Jíj moet betalen’, zei Hondewater. `Jíj wilt haar toch begraven?’

`Waar moet ik honderd piek vandaan halen?’ Stilletjes hoopte Crazy dat het vrouwtje wat zou zeggen, maar ze hield haar mond. Dat gezwets over geld was natuurlijk te banaal voor haar.

`Contant betalen’, zei Hondewater.

`Ik heb geen honderd piek’, zei Crazy.

`Ik betaal wel’, zei Albert, die van de akelige man af wilde zijn. Hij haalde een briefje van honderd uit zijn portefeuille en gaf het aan Hondewater. De dokter krabbelde wat op een formulier, gaf het aan Albert en verdween als een haas die in zijn kont was geschoten.

`Het ruikt hier steeds lekkerder’, zei Mireille, hoewel haar stem haast stikte in de tranen.

`Het ruikt hier naar een ijskar’, zei David. `Vanille en fruit.’

Ton van Reen: Katapult (24)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: - Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature