Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Students

‘Hoest?’

‘Vet en jij?’

‘Ook, wat gaan we doen?’

‘Appie H, knoeipakket scoren, knoeien bij mij?’

‘Doen we, cool’

‘Hé Joris join us’

‘Super, wat gaan we doen?’

‘Barbeknoeitje bij Menno’

‘Vet, let’s do it’

‘Scoor ik snel effe wat grolsies thuis, merkt Bart to nie’

‘Ik zeg doen’

‘Me too’

‘CU’

‘Catch you later boys’

Freda Kamphuis

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kamphuis, Freda

![]()

Valeria

Het zand onder haar boetseert

De naakte deining van haar lijf

Die onder haar weg spoelt, als zij

omkeert. Het gezonken beeld leert

mij haar te lezen: ze smaakt naar zout,

en is er even, de minnares

die mijn momenten leent. Oud

maar slaafs volg ik haar met een krans

van doorns in mijn haar, het is spelen

met mijn wil. Blauw en groot zijn haar

ogen als de zeven hemelen

die zij bestijgt; haar beeldenaar

mag ik zijn. Haar verkondigen

en afstaan. Zolang ze zondig

is en mijn vergeving zich richt

op haar stil en licht bewegen.

Niels Landstra

Niels Landstra presenteert dichtbundel: Waterval

Donderdag 20 september zal Niels Landstra zijn nieuwe dichtbundel Waterval presenteren bij Selexyz Gianotten in Breda, de Barones 63. De aanvang is 19.00 uur.

Na het verschijnen van het kort verhaal ‘Het portret’ in e-zine Meander in 2004, volgde een lange reeks publicaties (korte verhalen, poëzie en interviews) in diverse literaire tijdschriften in zowel Nederland als Vlaanderen. Het oeuvre van Niels Landstra is dan ook rijk, bevat elementen als liefde en dood, geloof en noodlot, en het nemen van afscheid, zoals in zijn gedicht Mijn liefste meisje: ‘Ik ben jou, je vlieger, je zonlicht; vrees de dagen zonder zandsculpturen en sprookjesfiguren die gespeend van jou en mij zullen zijn’.

Naast zijn gedichten en verhalen, schreef hij drie romans en een novelle, waar deze elementen sterk in verweven zijn en die een melancholische sfeer oproepen, maar ook een wrange vorm van humor kennen; deze vertelwijze maakt zijn werk dan ook boeiend tot de laatst gelezen letter.

Zijn dichtbundel ‘Waterval’ bij uitgeverij Oorsprong is zijn debuut als dichter.

Volgend jaar zal Niels Landstra’s eerste roman ‘De vereerder’ verschijnen bij uitgeverij Beefcake Publishing in Gent, België.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

Vincent Berquez© painting:

My son the musician

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Berquez, Vincent, Vincent Berquez

vincent berquez

this

this is the vessel

this is the child

the spontaneous

sparks into action

this is central

this is who we are

this is the treasure

and the bud opens.

this is you and me

in our ideal form,

we have blended

and here before us

is unrefined love

that is a smile

and we praise this

through him, with him.

29.09.10

Vincent Berquez Biography

Vincent Berquez is a London–based artist and poet. He has published in Britain, Europe, America and New Zealand. His work is in many anthologies, collections and magazine worldwide. Vincent Berquez was requested to write a Tribute as part of ‘Poems to the American People’ for the Hastings International Poetry Festival for 9/11, read by the mayor of New York at the podium. He has also been commissioned to write a eulogy by the son of Chief Albert Nwanzi Okoluko, the Ogimma Obi of Ogwashi-Uku to commemorate the death of his father. Berquez has been a judge many times, including for Manifold Magazine and had work read as part of Manifold Voices at Waltham Abbey. He has recited many times, including at The Troubadour and the Pitshanger Poets, in London. In 2006 his name was put forward with the Forward Prize for Literature. He recently was awarded a prize with Decanto Magazine. Berquez is now a member of London Voices who meet monthly in London, United Kingdom.

Vincent Berquez has also been collaborating in 07/08 with a Scottish composer and US film maker to produce a song-cycle of seven of his poems for mezzo-soprano and solo piano. These are being recorded at the Royal College of Music under the directorship of the concert pianist, Julian Jacobson. In 2009 he will be contributing 5 poems for the latest edition of A Generation Defining Itself, as well as 3 poems for Eleftheria Lialios’s forthcoming book on wax dolls published in Chicago. He also made poetry films that have been shown at various venues, including a Polish/British festival in London, Jan 07.

As an artist Vincent Berquez has exhibited world wide, winning prizes, such as at the Novum Comum 88’ Competition in Como, Italy. He has worked with an art’s group, called Eins von Hundert, from Cologne, Germany for over 16 years. He has shown his work at the Institute of Art in Chicago, US, as well as many galleries and institutions worldwide. Berquez recently showed his paintings at the Lambs Conduit Festival, took part in a group show called Gazing on Salvation, reciting his poetry for Lent and exhibiting paintings/collages. In October he had a one-man show at Sacred Spaces Gallery with his Christian collages in 2007. In 2008 Vincent Berquez had a solo show of paintings at The Foundlings Museum and in 2011 an exposition with new work in Langham Gallery London.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Berquez, Vincent, Vincent Berquez

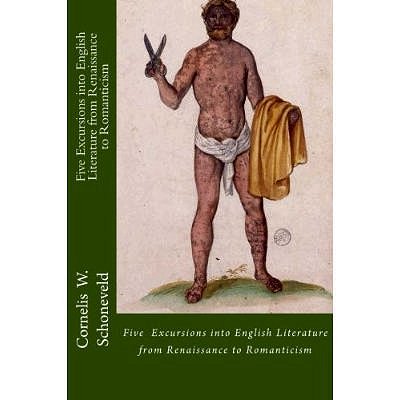

Five Excursions into English Literature from Renaissance to Romanticism by Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Dear Readers of Fleursdumal Magazine,

Some of you might be interested to respond to my experiment in the new phenomenon of self-publishing. During my active life as a researcher in the field of English literature, a few of the finished results were only published in abstract form, or in media with limited circulation. Instead of letting them ultimately go to waste, I have now put them together between the covers of one volume, and also in e-book form , via CreativeSpace, which is a subsidiary of www. amazon. com. CreateSpace is based in the USA, and to order the book there would involve a postage fee higher than the bookprice, but it is also available from w.w.w.amazon.de , (Germany) at a minimal price, with free delivery in the EU. Here is the link; the bottom of the page contains is a description of the (varied) contents.

Warm regards,

Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Five Excursions into English Literature from Renaissance to Romanticism [Englisch] [Paperback)

Cornelis W. Schoneveld (Author)

Of the five research essays collected here, two are excursions by the author chronologically outlining and discussing the history of English novel criticism from 1660 to 1800, and paying special attention to the terms ‘novel’, ‘romance’ and ‘history’. Two are concerned with excursions dealt with in literary texts themselves, the first being on how continental excursions by English Renaissance gentlemen influenced their dress habits as these were discussed and criticized at home; the second being on the haunting excursion undertaken by Coleridge’s Romantic Ancient Mariner, showing how and why it can be interpreted as his agonizing introduction into becoming a literary artist. The fifth essay maps out the excursion of Alexander Pope’s Essay on Man into Holland, by way of the five translations made of it in the 18th and 19th centuries, supplemented with a checklist of all his other works translated into Dutch. The research was done some time ago, but the results were not published earlier otherwise than in abstract form or in media with limited circulation. For many years Dr. C.W. Schoneveld was lecturer in the history of English Literature at the University of Leiden, the Netherlands. Two of his publications are Intertraffic of the Mind, Studies in 17th-Century Anglo-Dutch Translation (1983), and Sea-Changes, Studies in Three Centuries of Anglo-Dutch cultural Transmission (1996). His most recent work is a translation of 100 English poems into Dutch from the 16th to the 19th centuries in bilingual edition entitled Bestorm my Hart, (Amsterdam 2008), and a fully annotated translation of Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, with an introductory essay, (Amsterdam, 2011).

About Cornelis W. Schoneveld: For many years Dr. C.W. Schoneveld was lecturer in the history of English Literature at the University of Leiden, the Netherlands. Two of his publications are Intertraffic of the Mind, Studies in 17th-Century Anglo-Dutch Translation (1983), and Sea-Changes, Studies in Three Centuries of Anglo-Dutch cultural Transmission (1996). His most recent work is a translation of 100 English poems into Dutch from the 16th to the 19th centuries in bilingual edition entitled Bestorm mijn Hart, (Amsterdam 2008), and a fully annotated translation of Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, with an introductory essay, (Amsterdam, 2011).

Amazon.de

Taschenbuch: 118 Seiten

Editon: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (8. August 2012)

Englisch text

ISBN-10: 1478347082

ISBN-13: 978-1478347088

Cornelis W. Schoneveld: Poetry in translation

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, POETRY IN TRANSLATION: SCHONEVELD

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 143

Lo as a careful huswife runs to catch,

One of her feathered creatures broke away,

Sets down her babe and makes all swift dispatch

In pursuit of the thing she would have stay:

Whilst her neglected child holds her in chase,

Cries to catch her whose busy care is bent,

To follow that which flies before her face:

Not prizing her poor infant’s discontent;

So run’st thou after that which flies from thee,

Whilst I thy babe chase thee afar behind,

But if thou catch thy hope turn back to me:

And play the mother’s part, kiss me, be kind.

So will I pray that thou mayst have thy Will,

If thou turn back and my loud crying still.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD II

Daar stond Kana, op het punt klaar te komen, trillend van de pijn, die als een wortel door haar vuile lichaam liep, vanuit haar onderbuik.

Mijn ouwe bok Kaïn lachte. Hij lachte niet gemeen, zoals verwacht: hij had werkelijk pret. Hij hield zijn buik vast van het lachen.

Ik vond de toestand weer normaal, wilde verder gaan met mierrijden, maar kwam daar niet toe. Plotseling vielen er grote schaduwen over het hol, over het zand eromheen en over de hei.

Ik keek op en zag de blauwe benen van uniformzieke kerels. Hogerop: blinkende knopen en gespen. Nog hoger: kapotgeschoren kinnen boven stijve kragen. Verder niets. Niets van een hoofd of zoiets. De harde kinnen, dat was alles wat ik van de gezichten kon zien. De kerels hadden stokken waarmee ze sloegen. Daarbij bleven ze recht staan, als palen. Palen met levende takken die sloegen in het gezicht van mijn ouwe bok Kaïn.

Ik voelde me opgelucht. Ik had altijd geweten dat dit ervan moest komen. Altijd wordt alles gered door uniformen met blinkende knopen en gespen. Nu werd mijn ouwe bok Kaïn gered voor verder onheil. Ook de Gore Kana werd geslagen. De kerels hadden al veel geslagen, dat zag je aan hun routine. Ze spanden zich niet in. Toch kwamen de slagen hard aan.

Ik kwam overeind uit mijn gebukte houding en overzag in een paar tellen het slagveld. Van een van de uniformzieke kerels kon ik toen het gezicht zien. Hij had een gezicht van hout, net zo geil als dat van mijn ouwe bok Kaïn. Hij was niet geil op Kana. Dat was duidelijk. Hij toonde een intense afkeer van haar vuile, klagende lijf. Waarop de stokken neerkwamen.

Ik wist: ze mochten negenendertig slagen geven. Ik had het aantal slagen niet geteld. Ik schat dat ze achttien keer sloegen, dat Kaïn en Kana elk negen slagen kregen. Kana voelde ze het hardst. Ze was nog helemaal naakt. Daarna zag ik het gezicht boven het andere uniform. Een geteisterd gezicht. Een mislukte God die sloeg uit overtuiging.

De eerste sloeg omdat hij Kaïn en Kana lelijk vond. Een mooie vrouw zou hij beslist niet geslagen hebben. Hij zou op haar zijn gaan liggen om haar te naaien. De ander, die mislukte God, gaf een slecht voorbeeld. En bleek niet van zins vergiffenis te schenken. Ik dacht dat God alles vergaf en dat straf pas kwam na de dood! Grote mensen, zeker die met een gezicht van God, gaven altijd een slecht voorbeeld. En wat had deze man met Kaïn en Kana te maken? Waarom liet hij hen niet begaan? Ik zei er toch ook niets van? Ik wist best dat er eens een kind van zou komen. Een vuil kind met deuken in de huid van de slagen die de Gore Kana voortdurend kreeg van Kaïn. Ik zou van dat kind houden. Het zou een mongool worden, zoiets, omdat het slecht werd gevoed. Per slot van zaken werd het ook maar de wereld in geschopt.

De Gore Kana mocht zich niet aankleden. Dat was goed. Met kleren aan had ze nog minder vorm. De kerels dreven Kaïn en Kana voor zich uit. Mijn ouwe bok dacht alleen aan zijn eigen hachje. Hij vergat mij. De kerels vergaten mij ook.

Ik bleef alleen. Dit was geen toestand om te huilen. Ik moest blij zijn. Nu was ik mijn eigen baas. Nu hoefde ik me niet meer te ergeren aan het gedrag van Kaïn en zijn Gore Kana. Toch bleef ik lusteloos. Ik lette niet op de mieren die koortsachtig in treinen naar buiten bleven lopen en langs hun dode kameraden spoorden. Soms meende ik hen te horen zeggen: ‘Het zal hun straf wel zijn.’ Zoals dat ook onder mensen gaat.

Ik stond op, stak mijn handen in de broekzakken en liep in de andere richting dan de vier gegaan waren. De God en de wellusteling, Kaïn en Kana voor zich uit drijvend.

De weg was zacht. Overal bloeiden bremstruiken. Ze roken als altijd naar zweet. Ze werkten ook hard. Hun kleur was geler dan geel.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

j.a. woolf©

J.A. Woolf: Making memories (#26)

kempis.nl poetry magazine 2012

More in: J.A. Woolf

Pas geleden

Weet ik nog?

Wil ik nog?

Was ik weg,

voor even?

Zeg het me,

want pas geleden

is maar kort!

Pleun Andriessen

Pleun Andriessen is kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg 2011-2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Andriessen, Pleun, Archive A-B

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (28)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

1

Sweet and cool is the pulp of winter pears, but often, here and there, it hardens in a bitter knot. Your teeth, in the act of biting, come upon the hard piece and are set on edge. So is it with our position, which might be sweet and cool, for two of us at any rate, were we not conscious of the intrusion of something bitter and hard.

We have been going together, for the last three days, every morning, Signorina Luisetta, Aldo Nuti and I, to the Kosmograph.

Of the two of us, Signora Nene trusts me, certainly not Nuti, with her daughter. But the said daughter, of the two of us, certainly seems rather to be going with Nuti than to be coming with me.

Meanwhile: I see Signorina Luisetta, and do not see Nuti; Signorina Luisetta sees Nuti and does not see me; Nuti sees neither me nor Signorina Luisetta.

So we proceed, all three of us, side by side, but without seeing ourselves in one another’s company.

Signorina Nene’s confidence ought to irritate me, ought to… what else? Nothing. It ought to irritate me, it ought to degrade me: instead of which, it does not irritate me, it does not degrade me. It moves me, if anything. So as to make me feel more contemptuous than ever.

And so I consider the nature of this confidence, in an attempt to overcome my contemptuous emotion.

It is certainly an extraordinary tribute to my incapacity, on one hand; to my capacity, on the other. The latter–I mean the tribute to my capacity–might in one respect flatter me; but it is quite certain that this tribute has not been paid me by Signora Nene without a slight trace of derisive pity.

A man who is incapable of doing evil cannot, in her eyes, be a man at all. So that this other capacity of mine cannot be a manly quality.

It appears that we cannot help doing evil, if we are to be regarded as men. For my own part, I know quite well, perfectly well, that I am a man: evil I have done, and in abundance! But it appears that other people do not choose to notice it. And that makes me furious. It makes me furious because, obliged to assume that certificate of incapacity–which both is and is not mine–I often find my shoulders bowed, by the arrogance of other people, under a fine cloak of hypocrisy. And how often have I groaned beneath the weight of that cloak! At no time, I am certain, so often as during the last few days. I feel almost inclined to go and look Signora Nene in the face in a certain fashion, so that. … But, no, no, what an idea, poor woman! She has grown so meek, all of a sudden, so helpless rather, after that furious outbreak by her daughter and this sudden determination to become a cinematograph actress! You ought to see her when, shortly before we leave the house, every morning, she comes up to me and, behind her daughter’s back, raises her hands ever so slightly, with a furtive movement, and with a piteous look in her eyes:

“Take care of her,” she stammers.

The situation, as soon as we arrive at the Kosmograph, changes and becomes highly serious, notwithstanding the fact that at the entrance, every morning, we find–punctual to a second and trembling all over with anxiety–Cavalena. I have already told him, the day before yesterday and again yesterday, of the change in his wife; but Cavalena shews no sign as yet of becoming a Doctor again. Far from it! The day before yesterday and again yesterday, he seemed to be carried away before my eyes in a fit of distraction, as though trying not to let himself be affected by what I was saying to him:

“Oh, indeed? Good, good…” was his answer. “But I, for the present…. What is that you say? No, excuse me, I thought…. I am glad, don’t you know? But if I go back, it will all come to an end. Heaven help us! What I have to do at present is to stay here and consolidate Luisetta’s position and my own.”

Ah yes, consolidate: father and daughter might be treading on air. I reflect that their life might be easy and comfortable, their story unfold in a sweet, serene peace. There is the mother’s fortune; Cavalena, honest man, could attend quietly to his profession; there would be no need to take strangers into their home, and Signorina Luisetta, on the window sill of a peaceful little house in the sun, might gracefully cultivate, like flowers, the fairest dreams of girlhood. But no! This fiction which ought to be the reality, as everyone sees, for everyone admits that Signora Nene has absolutely no reason to torment her husband, this thing which ought to be the reality, I say, is a dream. The reality, on the other hand, must be something different, utterly remote from this dream. The reality is Signora Nene’s madness. And in the reality of this madness–which is of necessity an agonised, exasperated disorder–here they are flung out of doors, straying, helpless, this poor man and this poor girl. They wish to consolidate their position, both of them, in this reality of madness, and so they have been wandering about here for the last two days, side by side, sad and speechless, through the studios and grounds.

Cocò Polacco, to whom with Nuti they report on their arrival, tells them that there is nothing for them to do at present. But the engagement is in force; the salary is mounting up. It is unnecessary, therefore, for Signorina Luisetta to take the trouble to come; if she is not to pose, she does not lose anything.

But this morning, at last, they have made her pose. Polacco lent her to his fellow producer Bongarzoni for a small part in a coloured film, in eighteenth century costume.

I have been working for the last few days with Bongarzoni. On reaching the Kosmograph I hand over Signorina Luisetta to her father, go to the Positive Department to fetch my camera, and often it happens that for hours on end I see nothing more of Signorina Luisetta, nor of Nuti, nor of Polacco, nor of Cavalena. So that I was not aware that Polacco had given Bongarzoni Signorina Luisetta for this small part. I was thunderstruck when I saw her appear before me as if she had stepped out of a picture by Watteau.

She was with the Sgrelli, who had just completed a careful and loving supervision of her toilet in the “costume” wardrobe, and with one finger was pressing to her cheek a silken patch that refused to stick. Bongarzoni was lavish with his compliments, and the poor child made an effort to smile without moving her head, for fear of overbalancing the enormous pile of hair above it. She did not know how to move her limbs in that billowing silken skirt.

And now the little scene is arranged. An outside staircase, leading down to a stretch of park. The little lady appears from a glazed balcony; trips down a couple of steps; leans over the pillared balustrade to gaze out across the park, timid, perplexed, in a state of anxious alarm: then runs quickly down the remaining steps and hides a note, which is in her hand, under the laurel that is growing in a bowl on the pillar at the foot of the balustrade.

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

Never before have I turned the handle of my machine with such delicacy. This great black spider on its tripod has had her twice, now, for its dinner. But the first time, out in the Bosco Sacro, my hand, in turning the handle to give her to the machine to eat, did not yet ‘feel’. Whereas, on this occasion…

Ah, I am ruined, if ever my hand begins to feel! No, Signorina Luisetta, no: it is evident that you must not continue in this vile trade. Quite so, I know why you are doing it! They all tell you, Bongarzoni himself told you this morning that you have a quite exceptional natural gift for the scenic art; and I tell you so too; not because of this morning’s rehearsal, though. Oh, you went through your part as well as anyone could wish; but I know very well, I know very well how you were able to give such a marvellous rendering of anxious alarm, when, after coming down the first two steps, you leaned over the balustrade to gaze into the distance. I know so well that almost, now and then, I turned my head too to gaze where you were gazing, to see whether at that moment the Nestoroff might not have arrived.

For the last three days, here, you have been living in this state of anxiety and alarm. Not you only; although more, perhaps, than anyone else. At any moment, indeed, the Nestoroff may arrive. She has not been seen for more than a week. But she is in Rome; she has not left. Only Carlo Ferro has left, with five or six other actors and Bertini, for Tarante.

On the day of Carlo Ferro’s departure (about a fortnight ago), Polacco came to me radiant, as though a stone had been lifted from his chest.

“What did I tell you, simpleton? He would go to hell if she told him to!”

“I only hope,” I answered, “that we shan’t see him burst in here suddenly like a bomb.”

But it is already a great thing, certainly, and one that to me remains inexplicable, that he should have gone. His words still echo in my ears:

“I may be a wild beast when I’m face to face with a man, but as a man face to face with a wild beast I’m worth nothing!”

And yet, with the consciousness of being worth nothing, on a point of honour, he did not draw back, he did not refuse to face the beast; now, having a man to face, he has fled. Because it is indisputable that his departure, the day after Nuti’s arrival, has every appearance of flight.

I do not deny that the Nestoroff has such power over him that she can compel him to do what she wishes. But I have heard roaring in him, simply because of Nuti’s coming, all the fury of jealousy. His rage at Polacco’s having put him down to kill the tiger was not due only to the suspicion that Polacco was hoping in this way to get rid of him, but also and even more to the suspicion that he has made Nuti come here at the same time in order that Nuti may be free to recapture the Nestoroff. And it seems obvious to me that he is not sure of her. Why then has he gone?

No, no: there is most certainly something behind this, a secret agreement; this departure must be concealing a trap. The Nestoroff could never have induced him to go by shewing him that she was afraid of losing him, in any event, by allowing him to remain here to await the coming of a man who was certainly coming with the deliberate intention of provoking him. A fear of that sort would never have made him go. Or, at least, she would have gone with him. If she has remained here and he has gone, leaving the field clear for Nuti, it means that an agreement must have been reached between them, a net woven so strongly and securely that he himself has been able to pack tip his jealousy in it and so keep it in check. No sign of fear can she have shewn him; rather, the agreement having been reached, she must have demanded this proof of his faith in her, that he should leave her here alone to face Nuti. In fact, for several days after Carlo Ferro’s departure, she continued to come to the Kosmograph, evidently prepared for an encounter with Nuti. She cannot have come for any other reason, free as she now is from any professional engagement. She ceased to come, when she learned that Nuti was seriously ill.

But now, at any moment, she may return.

What is going to happen?

Polacco is once again on tenterhooks. He never lets Nuti out of his sight; if he is obliged to leave him for a moment, he first of all makes a covert signal to Cavalena. But Nuti, for all that, now and again, some slight obstacle makes him break out in a way that points to an exasperation forcibly held in check, is relatively calm; he seems also to have shaken off the sombre mood of the early days of his convalescence; he allows himself to be led about everywhere by Polacco and Cavalena; he shews a certain curiosity to make a closer acquaintance with this world of the cinematograph and has carefully visited, with the air of a stern inspector, both the departments.

Polacco, hoping to distract him, has twice suggested that he should try some part or other. He has declined, saying that he wishes to gain a little experience first by watching the others act.

“It is a labour,” he observed yesterday in my hearing, after he had watched the production of a scene, “and it must also be an effort that destroys, alters and exaggerates people’s expressions, this acting without words. In speaking, the action comes automatically; but without speaking….”

“You speak to yourself,” came with a marvellous seriousness from the little Sgrelli (La Sgrellina, as they all call her here). “You speak to yourself, so as not to force the action….”

“Exactly,” Nuti went on, as though she had taken the words out of his mouth.

The Sgrellina then laid her forefinger on her brow and looked all round her with an assumption of silliness which asked, with the most delicate irony:

“Who said I wasn’t intelligent?”

We all laughed, including Nuti. Polacco could hardly refrain from kissing her. Perhaps he hopes that she, Nuti having taken the place here of Gigetto Fleccia, may decide that he ought also to take Fleccia’s place in her affections, and may succeed in performing the miracle of detaching him from the Nestoroff. To enhance and give ample food to this hope, he has introduced him also to all the young actresses of the four companies; but it seems that Nuti, although exquisitely polite to all of them, does not shew the slightest sign of wishing to be detached. Besides, all the rest, even if they were not

already, more or less, bespoke, would take great care not to stand in the Sgrellina’s way. And as for the Sgrellina, I am prepared to bet that she has already observed that she would be doing an injury, herself, to a certain young lady, who has been coming for the last three days to the Kosmograph with Nuti and with ‘Shoot’.

Who has not observed it? Only Nuti himself! And yet I have a suspicion that he too has observed it. And the strange thing is this, and 1 should like to find a way of pointing it out to Signorina Luisetta: that his perception of her feeling for him creates an effect in him the opposite of that for which she longs: it turns him away from her and makes him strain all the more ardently after the Nestoroff. Because it is obvious now that Nuti remembers having identified her, in his delirium, with Duccella; and since he knows that she cannot and does not wish to love him any longer, the love that he perceives in Signorina Luisetta must of necessity appear to him a sham, no longer pitiful, now that his delirium has passed; but rather pitiless: a burning memory, which makes the old wound ache again.

It is impossible to make Signorina Luisetta understand this.

Glued by the clinging blood of a victim to his love for two different women, each of whom rejects him, Nuti can have no eyes for her; he may see in her the deception, that false Duccella, who for a moment appeared to him in his delirium; but now the delirium has passed, what was a pitiful deception has become for him a cruel memory, all the more so the more he sees the phantom of that deception persist in it.

And so, instead of retaining him, Signorina Luisetta with this phantom of Duccella drives him away, thrusts him more blindly than ever into the arms of the Nestoroff.

For her, first of all; then for him, and lastly–why not?–for myself, I see no other remedy than an extreme, almost a desperate attempt: that I should go to Sorrento, reappear after all these years in the old home of the grandparents, to revive in Duccella the earliest memory of her love and, if possible, take her away and make her come here to give substance to this phantom, ?which another girl, here, for her sake, is desperately sustaining with her pity and love.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (28)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (C)

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

C

CACHET: Toujours suivi de «tout particulier» .

CACHOT: Toujours affreux. La paille y est toujours humide. On n’en a pas encore rencontré de délicieux.

CADEAU: Ce n’est pas la valeur qui en fait le prix, ou bien ce n’est pas le prix qui en fait la valeur. Le cadeau n’est rien, c’est l’intention qui compte.

CAFÉ: Donne de l’esprit. N’est bon qu’en venant du Havre. Dans un grand dîner, doit se prendre debout. L’avaler sans sucre, très chic, donne l’air d’avoir vécu en Orient.

CALVITIE: Toujours précoce, est causée par des excès de jeunesse ou la conception de grande pensée.

CAMARILLA: S’indigner quand on prononce ce mot.

CAMPAGNE: Les gens de la campagne meilleurs que ceux des villes: envier leur sort. A la campagne tout est permis; habits bas, farces, etc.

CANARDS: Viennent tous de Rouen.

CANDEUR: Toujours adorable. On en est rempli ou on n’en a pas du tout.

CANONADE: Change le temps.

CARABINS: Dorment près des cadavres. Il y en a qui en mangent.

CARÈME: Au fond n’est qu’une mesure hygiénique.

CATAPLASME: Doit toujours être mis en attendant l’arrivée du médecin.

CATHOLICISME: A eu une influence très favorable sur les arts.

CAUCHEMAR: Vient de l’estomac.

CAVALERIE: Plus noble que l’infanterie.

CAVERNES: Habitation ordinaire des voleurs. Sont toujours remplies de serpents.

CÈDRE: Celui du Jardin des Plantes a été rapporté dans un chapeau.

CÉLÉBRITÉ: Les célébrités: s’inquiéter du moindre détail de leur vie privée, afin de pouvoir les dénigrer.

CELIBATAIRES: Tous égoïstes et débauchés. On devrait les imposer. Se préparent une triste vieillesse.

CENSURE: Utile, on a beau dire.

CERCLE: On doit toujours faire partie d’un cercle.

CERTIFICAT: Garantie pour les familles et pour les parents est toujours favorable.

CÉRUMEN: «Cire humaine» . Se garder de l’ôter parce qu’elle empêche les insectes d’enter dans les oreilles.

CHACAL: Singulier de shakos (vieux, mais fait toujours rire).

CHALEUR: Toujours insupportable. Ne pas boire quand il fait chaud.

CHAMBRE À COUCHER: Dans un vieux château: Henri IV y a toujours passé une nuit.

CHAMEAU: A deux bosses et le dromadaire une seule. Ou bien le chameau a une bosse et le dromadaire deux (on s’y embrouille).

CHAMPAGNE: Caractérise le dîner de cérémonie. Faire semblant de le détester, en disant que «ce n’est pas du vin« . Provoque l’enthousiasme chez les petites gens. La Russie en consomme plus que la France. C’est par lui que les idées françaises se sont répandues en Europe. Sous la Régence, on ne faisait pas autre chose que d’en boire. Mais on ne le boit pas, on le «sable» .

CHAMPIGNONS: Ne doivent être achetés qu’au marché.

CHANTEUR: Avalent tous les matins un oeuf frais pour s’éclaircir la voix. Le ténor a toujours une voix charmante et tendre, le baryton un organe sympathique et bien timbré, et la basse une émission puissante.

CHAPEAU: Protester contre la forme des chapeaux.

CHARCUTIER: Anecdote des pâtés faits avec de la chair humaine. Toutes les charcutières sont jolies.

CHARTREUX: Passent leur temps à faire de la chartreuse, à creuser leur tombe et à dire: «Frère, il faut mourir.»

CHASSE: Excellent exercice que l’on doit feindre d’adorer. Fait partie de la pompe des souverains. Sujet de délire pour la magistrature.

CHAT: Les chats sont traîtres. Les appeler tigres de salon. Leur couper la queue pour empêcher le vertigo.

CHÂTAIGNE: Femelle du marron.

CHATEAUBRIAND: Connu surtout par le beefsteak qui porte son nom.

CHÂTEAU FORT: A toujours subi un siège sous Philippe Auguste.

CHEMINÉE: Fume toujours. Sujet de discussion à propos du chauffage.

CHEMINS DE FER: Si Napoléon les avait eus à sa disposition, il aurait été invincible. S’extasier sur leur invention et dire: «Moi, monsieur, qui vous parle, j’étais ce matin à X…; je suis parti par le train de X…; là-bas, j’ai fait mes affaires, etc. , et à x heures, j’étais revenu!»

CHEVAL: S’il connaissait sa force, ne se laisserait pas conduire. Viande de cheval: beau sujet de brochure pour un homme qui désire se poser en personnage sérieux. Cheval de course: le mépriser. A quoi sert-il?

CHIEN: Spécialement créé pour sauver la vie à son maître. Le chien est l’ami de l’homme.

CHIRURGIENS: Ont le coeur dur: les appeler bouchers.

CHOLÉRA: Le melon donne le choléra. On s’en guérit en prenant beaucoup de thé avec du rhum.

CHRISTIANISME: A affranchi les esclaves.

CIDRE: Gâte les dents.

CIGARES: Ceux de la Régie, «tous infects» . Les seuls bons viennent par contrebande.

CIRAGE: N’est bon que si on le fait soi-même.

CLAIR-OBSCUR: On ne sait pas ce que c’est.

CLARINETTE: En jouer rend aveugle. Ex.: Tous les aveugles jouent de la clarinette.

CLASSIQUES (les): On est censé les connaître.

CLOCHER de village: Fait battre le coeur.

CLOU: V. boutons.

CLOWN: A été disloqué dès l’enfance.

CLUB: Sujet d’exaspération pour les conservateurs. Embarras et discussion sur la prononciation de ce mot.

COCHON: L’intérieur de son corps étant «tout pareil à celui d’un homme» , on devrait s’en servir dans les hôpitaux pour apprendre l’anatomie.

COCU: Toute femme doit faire son mari cocu.

COFFRES-FORTS: Leurs complications sont très faciles à déjouer.

COGNAC: Très funeste. Excellent dans plusieurs maladies. Un bon verre de cognac ne fait jamais de mal. Pris à jeun tue le ver de l’estomac.

COIT, COPULATION: Mots à éviter. Dire: «Ils avaient des rapports…»

COLÈRE: Fouette le sang; hygiénique de s’y mettre de temps en temps.

COLLEGE, lycée: Plus noble qu’une pension.

COLONIES (nos): S’attrister quand on en parle.

COMÉDIE: En vers, ne convient plus à notre époque. On doit cependant respecter la haute comédie. Castigat ridendo mores.

COMÈTES: Rire des gens qui en avaient peur.

COMMERCE: Discuter pour savoir lequel est le plus noble, du commerce ou de l’industrie.

COMMUNION: La première communion: le plus beau jour de la vie.

COMPAS: On voit juste quand on l’a dans l’oeil.

CONCERT: Passe-temps comme il faut.

CONCESSIONS: N’en faire jamais. Elles ont perdu Louis XVI.

CONCILIATION: Les prêcher toujours, même quand les contraires sont absolus.

CONCUPISCENCE: Mot de curé pour exprimer les désirs charnels.

CONCURRENCE: L’âme du commerce.

CONFISEURS: Tous les Rouennais sont confiseurs.

CONFORTABLE: Précieuse découverte moderne.

CONGRÉGANISTE: Chevalier d’Onan.

CONJURÉ: Les conjurés ont toujours la manie de s’inscrire sur une liste.

CONSERVATEUR: Homme politique à gros ventre. «Conservateur borné! – Oui, monsieur, les bornes servent de garde-fou. «

CONSERVATOIRE: Il est indispensable d’être abonné au Conservatoire.

CONSTIPATION: Tous les gens de lettres sont constipés. Influe sur les convictions politiques.

CONTRALTO: On ne sait pas ce que c’est.

CONVERSATION: La politique et la religion doivent en être exclues.

COPAHU: Feindre d’en ignorer l’usage.

COQ: Un homme maigre doit toujours dire qu’un bon coq n’est jamais gras.

COR aux pieds: Indique le changement de temps mieux qu’un baromètre. Très dangereux quand il est mal coupé: citer des exemples d’accidents terribles.

COR de chasse: Dans les bois fait bon effet, et le soir sur l’eau.

CORDE: On ne connaît pas la force d’une corde. Est plus solide que le fer.

CORDONNIER: Ne sutor ultra crepidam.

CORPS: Si nous savions comment notre corps est fait, nous n’oserions pas faire un mouvement.

CORSET: Empêche d’avoir des enfants.

COSAQUES: Mangent de la chandelle.

COTON: Est surtout utile pour les oreilles.

COURTISANE: Est un mal nécessaire. Sauvegarde de nos filles et de nos soeurs tant qu’il y aura des célibataires. Devraient être chassées impitoyablement. On ne peut plus sortir avec sa femme à cause de leur présence sur le boulevard. Sont toujours des filles du peuple débauchées par des bourgeois riches.

COUSIN: Conseiller aux maris de se méfier du petit cousin.

COUTEAU: Est catalan quand la lame est longue. S’appelle poignard quand il a servi à commettre un crime.

CRAPAUD: Mâle de la grenouille. Possède un venin fort dangereux. Habite l’intérieur des pierres.

CRÉOLE: Vit dans un hamac.

CRIMINEL: Toujours odieux.

CRITIQUE: Toujours éminent. Est censé tout connaître, tout savoir, avoir tout lu, tout vu. Quand il vous déplaît, l’appeler Aristarque, ou eunuque.

CROCODILE: Imite le cri des enfants pour attirer l’homme.

CROISADES: Ont été bienfaisantes pour le commerce de Venise.

CRUCIFIX: Fait bien dans une alcôve et à la guillotine.

CUIR: Tous les cuirs viennent de Russie.

CUISINE: De restaurant: toujours échauffante. Bourgeoise: toujours saine. Du Midi: trop épicée ou toute à l’huile.

CUJAS: Inséparable de Bartole; on ne sait pas ce qu’ils ont écrit, n’importe. Dire à tout homme étudiant le droit: «Vous êtes enfermé dans Cujas et Bartole»

CURACAO: Le meilleur est de Hollande parce qu’il se fabrique à Curaçao, une des Antilles.

CYGNE: Chante avant de mourir. Avec son aile peut casser la cuisse d’un homme. Le cygne de Cambrai n’était pas un oiseau, mais un homme nommé Fénélon. Le cygne de Mantoue, c’est Virgile. Le cygne de Pesaro, c’est Rossini.

CYPRÈS: Ne pousse que dans les cimetières.

CZAR: Prononcer tzar et de temps en temps autocrate.

Gustave Flaubert:

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (C)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

Middeleeuws Iers gedicht

vertaald door Lauran Toorians

Teicht do Róim:

mór saído, becc torbai!

in rí chon-daigi hi foss,

manim-bera latt, ní fogbai.

Op weg naar Rome:

veel moeite, geringe winst!

De koning die je hier zoekt,

– tenzij je hem meebrengt –

vind je niet.

Middeleeuwse Ierse gedichten vertaald door Lauran Toorians

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature