Fleurs du Mal Magazine

![]()

Harriet Laurey

(1924–2004)

Uiteindelijk

Blijf nu voorgoed in mij gestorven;

want dit is een onschendbaar graf.

Ik heb U eindelijk verworven.

Ik sta U niet meer af.

Houd nu voorgoed Uw oog gesloten

over het laatst-gespiegeld beeld,

dat op Uw netvlies ligt gebroken

en niet meer heelt.

Mijn aarde streelt U overal.

Mijn diepte vult zich met Uw droom,

– Uw wezen, eindelijk verlost -,

die ik eenmaal vertalen zal

in liefde’s teder idioom:

gras, bloemen, vochtig mos.

(uit: Triple alliantie, 1951)

Harriet Laurey poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Brabantia Nostra

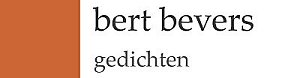

Gerard Manley Hopkins

(1844 – 1889)

The Alchemist in the City

My window shews the travelling clouds,

Leaves spent, new seasons, alter’d sky,

The making and the melting crowds:

The whole world passes; I stand by.

They do not waste their meted hours,

But men and masters plan and build:

I see the crowning of their towers,

And happy promises fulfill’d.

And I – perhaps if my intent

Could count on prediluvian age,

The labours I should then have spent

Might so attain their heritage,

But now before the pot can glow

With not to be discover’d gold,

At length the bellows shall not blow,

The furnace shall at last be cold.

Yet it is now too late to heal

The incapable and cumbrous shame

Which makes me when with men I deal

More powerless than the blind or lame.

No, I should love the city less

Even than this my thankless lore;

But I desire the wilderness

Or weeded landslips of the shore.

I walk my breezy belvedere

To watch the low or levant sun,

I see the city pigeons veer,

I mark the tower swallows run

Between the tower-top and the ground

Below me in the bearing air;

Then find in the horizon-round

One spot and hunger to be there.

And then I hate the most that lore

That holds no promise of success;

Then sweetest seems the houseless shore,

Then free and kind the wilderness,

Or ancient mounds that cover bones,

Or rocks where rockdoves do repair

And trees of terebinth and stones

And silence and a gulf of air.

There on a long and squared height

After the sunset I would lie,

And pierce the yellow waxen light

With free long looking, ere I die.

Gerard Manley Hopkins poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hopkins, Gerard Manley

George Sand

(1804-1876)

À Aurore

La nature est tout ce qu’on voit,

Tout ce qu’on veut, tout ce qu’on aime.

Tout ce qu’on sait, tout ce qu’on croit,

Tout ce que l’on sent en soi-même.

Elle est belle pour qui la voit,

Elle est bonne à celui qui l’aime,

Elle est juste quand on y croit

Et qu’on la respecte en soi-même.

Regarde le ciel, il te voit,

Embrasse la terre, elle t’aime.

La vérité c’est ce qu’on croit

En la nature c’est toi-même.

George Sand poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, George Sand

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 144

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still,

The better angel is a man right fair:

The worser spirit a woman coloured ill.

To win me soon to hell my female evil,

Tempteth my better angel from my side,

And would corrupt my saint to be a devil:

Wooing his purity with her foul pride.

And whether that my angel be turned fiend,

Suspect I may, yet not directly tell,

But being both from me both to each friend,

I guess one angel in another’s hell.

Yet this shall I ne’er know but live in doubt,

Till my bad angel fire my good one out.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD III

CHERUBIJN

Voortaan zou ik alleen door de wereld gaan.

Vluchten noemde ik het niet. Aan mij zag trouwens niemand dat ik er vandoor ging. Nog minder voor wie of voor wat ik vluchtte. Ik kon overal naar- toe. De meeste mensen lachten naar me en dachten: dat jongetje loopt een eindje om. Soms zei er een: ‘Kijk, kijk, daar hebben we de jonge heer Kaïn. Hij gaat op stap. Hij heeft een aardje naar zijn vaartje.’ Maar hoe kon ik, zo jong nog, op mijn ouwe bok Kaïn lijken die al zestig was geweest en die nogal last had van de jeugdige neiging tot overdrijven?

Tegen de avond kwam ik aan in het dorp Boeroe. De mensen van het dorp waren niet thuis. Ze waren naar de kermis in Oeroe. Boeroe hoorde tot de gemeente Oeroe. Men zoop er, nog net zo hard als voor de oorlog, zoals de mensen het uitdrukten. Ze zopen zoals ik het vaak mijn ouwe bok Kaïn had zien doen. Tot aan het delirium zuipen en dan ophouden. Op het randje van de volslagen waanzin ophouden uit een redelijke overweging. De wens om langer te leven of zo. Dat zou een wens kunnen zijn van mensen die vijf jaar of langer met de dood op de hielen hadden gelopen. Het was belachelijk, maar dat wist ik toen nog niet.

Dus liep ik door naar Oeroe. Op het kermisplein stond een hoge draaimolen. De witte paarden die vastgeschroefd waren aan het plankier, werden dol van het draaien. Het was goed te zien. Hun uit hout gesneden tongen hingen klaaglijk uit hun bekken. Ze leken levenloos, maar ik wist dat ze leefden onder hun houten pantser en dat ze blij zouden zijn als de kinderen van Oeroe en Boeroe naar bed werden gebracht zodat die hen niet meer konden geselen met hun venijnige handjes.

Ook stond er een zweefmolen waarin jongelui op vrijersleeftijd, in stoeltjes die aan kettingen hingen, grote bogen langs de hemel trokken. De meisjes wapperden luid met hun kleren. De jongens lachten grollig en boers om ingehouden grappen, trokken de meisjes aan hun rokken, probeerden hen achter in hun nek te zoenen.

Daar zag ik Cherubijn.

Hij had een houten poot en zag eruit als een piraat.

Hij was duidelijk jaloers op de jeugd die hoog boven ons rondcirkelde. Of er geen groter genot bestond dan in een bijna horizontale toestand in rondjes over de aarde te scheren, het hele kermisterrein te overschouwen, in cafés binnen te kijken, heel vluchtig over de daken te reiken en soms de lichten te zien van de dorpen als Borz en Gretz. Misschien zelfs van de Lichtstad Kork.

Daar stond mijn zoveelste vader!

Cherubijn.

Veel schoner dan mijn ouwe bok Kaïn was hij niet. Dat kwam door zijn gebreken. Behalve zijn houten poot was het hem onmogelijk zijn rechterarm te bewegen. En zijn hoofd reageerde niet op commando’s die door de hersens via prikkelingen in het centrale zenuwstelsel gegeven werden, maar wel op bevelen die ergens uit zijn lijf kwamen. Misschien uit zijn mond, misschien uit zijn hart. Zijn zenuwen hadden het in de buurt van zijn nekspieren laten afweten. Daarom bleef hij nog een minuut of wat naar de jeugd boven ons hoofd kijken terwijl hij zich al inspande naar beneden te kijken nadat ik hem aangestoten had en gezegd had: ‘Dag Cherubijn.’

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (29)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

2

A note from the Nestoroff, this morning at eight o’clock (a sudden and mysterious invitation to call upon her with Signorina Luisetta on our way to the Kosmograph), has made me postpone my departure.

I remained standing for a while with the note in my hand, not knowing what to make of it. Signorina Luisetta, already dressed to go out, came down the corridor past the door of my room; I called to her.

“Look at this. Read it.”

Her eyes ran down to the signature; as usual, she turned a deep red, then deadly pale; when she had finished reading it, she fixed her eyes on me with a hostile expression, her brow contracted in doubt and alarm, and asked in a faint voice:

“What does she want?”

I waved my hands in the air, not so much because I did not know what answer to make as in order to find out first what she thought about it.

“I am not going,” she said, with some confusion. “What can she want with me?”

“She must have heard,” I explained, “that he … that Signor Nuti is staying here, and…”

“And?”

“She may perhaps have some message to give, I don’t know… for him.”

“To me?”

“Why, I imagine, to you too, since she asks you to come with me….”

She controlled the trembling of her body; she did not succeed in controlling that of her voice:

“And where do I come in?”

“I don’t know; I don’t come in either,” I pointed out to her. “She wants us both….”

“And what message can she have to give me … for Signor Nuti?”

I shrugged my shoulders and looked at her with a cold firmness to call her back to herself and to indicate to her that she, in so far as her own person was concerned–she, as Signorina Luisetta, could have no reason to feel this aversion, this disgust for a lady for whose kindness she had originally been so grateful.

She understood, and grew even more disturbed.

“I suppose,” I went on, “that if she wishes to speak to you also, it will be for some good purpose; in fact, it is certain to be. You take offence….”

“Because… because I cannot… possibly … imagine…” she broke out, hesitating at first, then with headlong speed, her face catching fire as she spoke, “what in the world she can have to say to me, even if, as you suppose, it is for a good purpose. I…”

“Stand apart, like myself, from the whole affair, you mean?” I at once took her up, with increasing coldness. “Well, possibly she thinks that you may be able to help in some way….”

“No, no, I stand apart; you are quite right,” she hastened to reply, stung by my words. “I intend to remain apart, and not to have anything to do, so far as Signor Nuti is concerned, with this lady.”

“Do as you please,” I said. “I shall go alone. I need not remind you that it would be as well not to say anything to Nuti about this invitation.”

“Why, of course not!”

And she withdrew.

I remained for a long time considering, with the note in my hand, the attitude which, quite unintentionally, I had taken up in this short conversation with Signorina Luisetta.

The kindly intentions with which I had credited the Nestoroff had no other foundation than Signorina Luisetta’s curt refusal to accompany me in a secret manoeuvre which she instinctively felt to be directed against Nuti. I stood up for the Nestoroff simply because she, in inviting Signorina Luisetta to her house in my company, seems to me to have been intending to detach her from Nuti and to make her my companion, supposing her to be my friend.

Now, however, instead of letting herself be detached from Nuti, Signorina Luisetta has detached herself from me and has made me go alone to the Nestoroff. Not for a moment did she stop to consider the fact that she had been invited to come with me; the idea of keeping me company had never even occurred to her; she had eyes for none but Nuti, could think only of him; and my words had certainly produced no other effect on her than that of ranging me on the side of the Nestoroff against Nuti, and consequently against herself as well.

Except that, having now failed in the purpose for which I had credited the other with kindly intentions, I fell back into my original perplexity and in addition became a prey to a dull irritation and began to feel in myself also the most intense distrust of the Nestoroff. My irritation was with Signorina Luisetta, because, having failed in my purpose, I found myself obliged to admit that she had after all every reason to be distrustful. In fact, it suddenly became evident to me that I only needed Signorina Luisetta’s company to overcome all my distrust. In her absence, a feeling of distrust was beginning to take possession of me also, the distrust of a man who knows that at any moment he may be caught in a snare which has been spread for him with the subtlest cunning.

In this state of mind I went to call upon the Nestoroff, unaccompanied. At the same time I was urged by an anxious curiosity as to what she would have to say to me, and by the desire to see her at close quarters, in her own house, albeit I did not expect either from her or from the house any intimate revelation.

I have been inside many houses, since I lost my own, and in almost all of them, while waiting for the master or mistress of the house to appear, I have felt a strange sense of mingled annoyance and distress, at the sight of the more or less handsome furniture, arranged with taste, as though in readiness for a stage performance. This distress, this annoyance I feel more strongly than other people, perhaps, because in my heart of hearts there lingers inconsolable the regret for my own old-fashioned little house, where everything breathed an air of intimacy, where the old sticks of furniture, lovingly cared for, invited us to a frank, familiar confidence and seemed glad to retain the marks of the use we had made of them, because in those marks, even if the furniture was slightly damaged by them, lingered our memories of the life we had lived with it, in which it had had a share. But really I can never understand how certain pieces of furniture can fail to cause if not actually distress at least annoyance, furniture with which we dare not venture upon any confidence, because it seems to have been placed there to warn us with its rigid, elegant grace, that our anger, our grief, our joy must not break bounds, nor rage and struggle, nor exult, but must be controlled by the rules of good breeding. Houses made for the rest of the world, with a view to the part that we intend to play in society; houses of outward appearance, where even the furniture round us can make us blush if we happen for a moment to find ourselves behaving in some fashion that is not in keeping with that appearance nor consistent with the part that we have to play.

I knew that the Nestoroff lived in an expensive furnished flat in Via Mecenate. I was shewn by the maid (who had evidently been warned of my coming) into the drawing-room; but the maid was a trifle disconcerted owing to this previous warning, since she expected to see me arrive with a young lady. You, to the people who do not know you, and they are so many, have no other reality than that of your light trousers or your brown greatcoat or your “English” moustache. I to this maid was a person who was to come with a young lady. Without the young lady, I might be some one else. Which explains why, at first, I was left standing outside the door.

“Alone? And your little friend?” the Nestoroff was asking me a moment later in the drawing-room. But the question, when half uttered, between the words “your” and “little,” sank, or rather died away in a sudden change of feeling. The word “friend” was barely audible. This sudden change of feeling was caused by the pallor of my bewildered face, by the look in my eyes, opened wide in an almost savage stupefaction.

Looking at me, she at once guessed the reason of my pallor and bewilderment, and at once she too turned pale as death; her eyes became strangely clouded, her voice failed, and her whole body trembled before me as though I were a ghost.

The assumption of that body of hers into a prodigious life, in a light by which she could never, even in her dreams, have imagined herself as being bathed and warmed, in a transparent, triumphant harmony with a nature round about her, of which her eyes had certainly never beheld the jubilance of colours, was repeated six times over, by a miracle of art and love, in that drawing-room, upon six canvases by Giorgio Mirelli.

Fixed there for all time, in that divine reality which he had conferred on her, in that divine light, in that divine fusion of colours, the woman who stood before me was now what? Into what hideous bleakness, into what wretchedness of reality had she now fallen? And how could she have had the audacity to dye with that strange coppery colour the hair which there, on those six canvases, gave with its natural colour such frankness of expression to her earnest face, with its ambiguous smile, with its gaze plunged in the melancholy of a sad and distant dream!

She humbled herself, shrank back as though ashamed into herself, beneath my gaze which must certainly have expressed a pained contempt. From the way in which she looked at me, from the sorrowful contraction of her eyebrows and lips, from her whole attitude I gathered that not only did she feel that she deserved my contempt, but she accepted it and was grateful to me for it, since in that contempt, which she shared, she tasted the punishment of her crime and of her fall. She had spoiled herself, she had dyed her hair, she had brought herself to this wretched reality, she was living with a coarse and violent man, to make a sacrifice of herself: so much was evident; and she was determined that henceforward no one should approach her to deliver her from that self-contempt to which she had condemned herself, in which she reposed her pride, because only in that firm and fierce determination to despise herself did she still feel herself worthy of the luminous dream, in which for a moment she had drawn breath and to which a living and perennial testimony remained to her in the prodigy of those six canvases.

Not the rest of the world, not Nuti, but she, she alone, of her own accord, doing inhuman violence to herself, had torn herself from that dream, had dashed headlong from it. Why? Ah, the reason, perhaps, was to be sought elsewhere, far away. Who knows the secret ways of the soul? The torments, the darkenings, the sudden, fatal determinations? The reason, perhaps, must be sought in the harm that men had done to her from her childhood, in the vices by which she had been ruined in her early, vagrant life, and which in her own conception of them had so outraged her heart that she no longer felt it to deserve that a young man should with his love rescue and ennoble it.

As I stood face to face with this woman so fallen, evidently most unhappy and by her unhappiness made the enemy of all mankind and most of all of herself, what a sense of degradation, of disgust assailed me suddenly at the thought of the vulgar pettiness of the relations in which I found myself involved, of the people with whom I had undertaken to deal, of the importance which I had bestowed and was bestowing upon them, their actions, their feelings! How idiotic that fellow Nuti appeared to me, and how grotesque in his tragic fatuity as a fashionable dandy, all crumpled and soiled in his starched finery clotted with blood! Idiotic and grotesque the Cavalena couple, husband and wife! Idiotic Polacco, with his air of an invincible leader of men! And idiotic above all my own part, the part which I had allotted to myself of a comforter on the one hand, on the other of the guardian, and, in my heart of hearts, the saviour of a poor little girl, whom the sad, absurd confusion of her family life had led also to assume a part almost identical with my own; namely that of the phantom saviour of a young man who did not wish to be saved!

I felt myself, all of a sudden, alienated by this disgust from everyone and everything, including myself, liberated and so to speak emptied of all interest in anything or anyone, restored to my function as the impassive manipulator of a photographic machine, recaptured only by my original feeling, namely that all this clamorous and dizzy mechanism of life can produce nothing now but stupidities. Breathless and grotesque stupidities! What men, what intrigues, what life, at a time like this? Madness, crime or stupidity. A cinematographic life? Here, for instance: this woman who stood before me, with her coppery hair. There, on the six canvases, the art, the luminous dream of a young man who was unable to live at a time like this. And here, the woman, fallen from that dream, fallen from art to the cinematograph. Up, then, with a camera and turn the handle! Is there a drama here? Behold the principal character.

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (29)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

![]()

Mijn liefste meisje

Willoos is de vlieger

die meevaart op zonnestralen

naar een rimpelrode branding

van oud geworden licht

Mijn meisje bij zee;

ommuurd met sterfelijkheid

heb ik je zandkastelen, je zijgende beelden

van ridders en prinsessen

Ik ben jou, je vlieger,

je zonlicht; vrees de dagen

zonder zandsculpturen en sprookjesfiguren

die gespeend van jou en mij zullen zijn

Niels Landstra

Niels Landstra presenteert dichtbundel: Waterval

Donderdag 20 september zal Niels Landstra zijn nieuwe dichtbundel Waterval presenteren bij Selexyz Gianotten in Breda, de Barones 63. De aanvang is 19.00 uur.

Na het verschijnen van het kort verhaal ‘Het portret’ in e-zine Meander in 2004, volgde een lange reeks publicaties (korte verhalen, poëzie en interviews) in diverse literaire tijdschriften in zowel Nederland als Vlaanderen. Het oeuvre van Niels Landstra is dan ook rijk, bevat elementen als liefde en dood, geloof en noodlot, en het nemen van afscheid, zoals in zijn gedicht Mijn liefste meisje: ‘Ik ben jou, je vlieger, je zonlicht; vrees de dagen zonder zandsculpturen en sprookjesfiguren die gespeend van jou en mij zullen zijn’.

Naast zijn gedichten en verhalen, schreef hij drie romans en een novelle, waar deze elementen sterk in verweven zijn en die een melancholische sfeer oproepen, maar ook een wrange vorm van humor kennen; deze vertelwijze maakt zijn werk dan ook boeiend tot de laatst gelezen letter.

Zijn dichtbundel ‘Waterval’ bij uitgeverij Oorsprong is zijn debuut als dichter.

Volgend jaar zal Niels Landstra’s eerste roman ‘De vereerder’ verschijnen bij uitgeverij Beefcake Publishing in Gent, België.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

Norbert de Vries

Kemp natuurlijk (IV)

Pierre (1 december 1886- 21 juli 1967) en Mathias (31 december 1890- 7 augustus 1964) waren beide autodidact.

Van de lagere school ging het linea recta naar de fabriek. In hun geval was dat de Société Céramique. Die enorm grote fabriek is een jaar of tien gelden gesloopt, en nu ligt daar een prachtige, nieuwe stadswijk. Inderdaad, de wijk Céramique.

Pierre en Math werkten er als plateelschilder.

Het is bijna ongelooflijk om te zien hoe beide jongelieden zich ontwikkeld hebben.

In de lijn van hun dagelijkse werk is hun inschrijving als leerling van het Stadstekeninstituut.

Pierre schilderde er vijf jaar (1906-1911), samen met onder anderen Jan Grégoire en Henri Jonas (die voor een loopbaan in de beeldend kunst zouden kiezen), en het is niet overdreven om Pierre op een met hen vergelijkbaar artistiek niveau te stellen. Pierre Kemp is beroemd geworden als dichter, maar hij heeft enige tijd zeer serieus gewerkt aan een carrière als kunstschilder.

En dan: zijn echte, zijn grote droom was het om componist te worden.

De beide broers kwamen uit een volstrekt niet intellectueel of artistiek milieu, ze hadden weinig onderwijs genoten, en toch hebben ze alle twee erg veel bereikt op het terrein van het geschreven woord. Ze kregen daarvoor ook de alleszins verdiende maatschappelijke erkenning.

Voor me ligt het dossier 1823 (niet openbaar). Een dossier over Koninklijke Onderscheidingen.

Over Math zit er méér in dan over Pierre. Math wordt ook eerder onderscheiden dan Pierre. Je krijgt als lezer van de stukken (na meer dan 50 jaar) ook de indruk dat Math in Maastricht meer gezien was dan Pierre.

We schrijven oktober 1950.

Er heeft zich een Mathias Kemp-Comité gevormd, met lokale zwaargewichten als dr. H. van Can, drs. J. Notermans en mr. Drs. H. Wouters.

Het comité heeft op 19 oktober een gesprek gehad met burgemeester mr. W. Baron Michiels van Kessenich met het oogmerk te bevorderen dat aan Mathias Kemp bij gelegenheid van zijn zestigste verjaardag een KO wordt verleend.

Op 7 november zendt het comité een uitgewerkte levensbeschrijving (4 pagina’s). Voorts geeft Jef Notermans een 5 bladzijden omvattende beschouwing ten beste over ‘Mathias Kemp en de BeNeLux-gedachte. Ook is er een curriculum vitae opgesteld met een opsomming daarbij van ’s mans vele publicaties (poëzie, proza, toneel, uitgaven op cultureel, historisch en sociaal-economisch gebied).

Indrukwekkend. Er is werkelijk flink werk van gemaakt.

De burgemeester heeft er eveneens zichtbaar zorg aan besteed: de concept-brief heeft hij op diverse punten gecorrigeerd en aangepast. En hoe snel handelt hij: de voordracht gaat op 10 november 1950 de deur uit.

Het is voor iemand die de procedures kent geen verrassing: een uitreiking van de onderscheiding op 31 december 1950 is niet haalbaar gebleken. Het wordt uiteindelijk 12 maart 1951. Behoorlijk snel, toch nog.

De brief van het Ministerie van Onderwijs, Kunsten en Wetenschappen is van 6 maart 1951, ondertekend door mr. J. Cals.

Kennelijk kent hij Math Kemp, ‘letterkundige en journalist’, persoonlijk, want de burgemeester wordt nadrukkelijk gevraagd Kemp namens hem te feliciteren.

De geridderde Math was, veel meer dan Pierre, een bekende Limburger.

In 1913 stapte hij van het plateel schilderen over naar de journalistiek. Opmerkelijk dat iemand zoiets lukt. Dan moet je toch over veel talent beschikken. Maar kennelijk zonder enig probleem nam hij de redactie van het weekblad De Maastrichter Krant op zich, en onderscheidde hij zich door het schrijven van vlammende artikelen tegen de expansieneigingen van het Duitse keizerrijk.

Tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog is hij de eerste bibliothecaris van de katholieke bibliotheek van Maastricht.

In 1920 wordt hij hoofdredacteur van het weekblad Limburgs Leven (het eerste tijdschrift van algemene strekking in dit landsdeel!), later opgevolgd door De Nedermaas.

Math is op allerlei journalistiek en publicitair vlak actief. Hij vervult voor kortere of langere tijd diverse functies: secretaris van de Kamer van Koophandel, redacteur voor de provincie Limburg van De Maasbode, hoofdredacteur van dagblad De Nieuwe Venlosche Courant, directeur en firmant van de boekhandel en uitgeverij Veldeke te Maastricht, correspondent van De Tijd en Het Algemeen Dagblad, en, sinds 1933, eigenaar en beheerder van het Limburgs antiquariaat en uitgeverij Veldeke.

Op 10 mei 1940 wordt hij gegijzeld door de Duitsers, en is daarmee een van de eerste politieke gevangenen in Nederland!

(mooi detail: burgemeester Michiels van Kessenich moest in mei 1940 van de Duitsers een lijstje van tien vooraanstaande Maastrichtenaren opstellen. Deze mensen golden dan als gijzelaar, ‘als waarborg voor de rustige houding van de Maastrichtenaren’. Van Kessenich gaf, zonder iemand te consulteren, de namen van tien intimi of (kaart)vrienden van hem. Natuurlijk had hij zichzelf bovenaan dat lijstje moeten plaatsen, maar hij verzuimde dat.

Zijn vrienden hebben die weinig dappere houding niet erg gewaardeerd. Kort na de bevrijding van ons land moest er een nieuw kabinet worden geformeerd, en Van Kessenich zou daarin minister worden. Op het laatste moment ging dat niet door. Algemeen wordt inmiddels aangenomen dat die gijzelaarskwestie daar de oorzaak van is geweest.

Overigens is geen der gijzelaars, onder wie dus Math Kemp, een haar gekrenkt tijdens de oorlog.)

In 1951 wordt Math Ridder in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau. En zijn geniale broer? Die moet wachten tot zijn zeventigste verjaardag.

Op 30 januari 1956 schrijft de toenmalige wethouder van onderwijs, kunsten en wetenschappen, Fons Baeten (inderdaad, de latere burgemeester van Maastricht) een korte nota aan de burgemeester, waaruit ik volgende regels citeer:

“Op 1 december van dit jaar zal, zo dit God belieft, de dichter Pierre Kemp zeventig jaar worden. Deze in wezen weinig belangrijke gebeurtenis lijkt mij een gerede aanleiding om de persoon en het werk van deze dichter tot voorwerp van bijzondere belangstelling voor de overheid te maken.

Ik koester het plan de stad Maastricht te interesseren in de uitgave van een gedichtencyclus die de dichter onlangs in regeringsopdracht wijdde aan Maastricht. Nadere voorstellen dienaangaande zullen het College eerlang bereiken. (…..) Een overzicht van leven en werk van de dichter, van de hand van Fernand M. de Louvick (Fernand Lodewick) diene ter adstructie van mijn en eventueel Uw verzoek.”

Het overzicht van De Louvick sluit op pagina 3 af met de zin: “Volgens onze mening is Pierre Kemp niet alleen een dichter die in de hedendaagse Nederlandse literatuur tot de merkwaardigste (sic!) en beste (sic!) gerekend moet worden, maar beweegt hij zich in zijn verzen op een wat men noemen kan Europees peil.”

Middelbare school, vak Nederlands: Literaire kunst van Lodewick. Ik denk dat ik het nog grotendeels van buiten ken. Wat mooi om deze Lodewick zovele jaren nadien nog op een taalfoutje te kunnen betrappen.

Het jaar 1956 is voor Pierre echt een feestjaar geworden.

Hij ontvangt de Constantijn Huygensprijs, en in Maastricht is er onder voorzitterschap van Jef Notermans een werk-comité actief om de ‘dichter-schilder Pierre Kemp’ een passende hulde te brengen, onder meer met een expositie van een paar dozijn van zijn schilderijen in de zalen van de Jan van Eyck-Academie.

” . . . zal in de maand december kunstcritici en minnaars van een kleurrijk palet de overtuiging schenken, dat Pierre Kemp als picturale nazaat van Graafland en Jonas een eervolle plaats inneemt tussen oudere en jongere beoefenaars van Apelles’ kunst.”.

Trouwens, in 1956 verschijnt de bundel Engelse Verfdoos, volgens velen zijn beste werk.

Op 1 december 1956 ontvangt Pierre het Ridderkruis in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau.

Vlak voor zijn dood zal hij, op 30 april 1967, worden bevorderd tot Officier in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau. Het gaat allemaal in grote haast. In het dossier een handgeschreven, ongedateerde notitie:

De heer P. Kemp wordt verpleegd in het ziekenhuis. Naar mededeling van zoon Kemp komt P. Kemp niet meer thuis. Hart en longen zijn zeer zwak.

Norbert de Vries: Kemp natuurlijk (IV)

Mijmeringen over Pierre Kemp uit mijn Maastrichtse tijd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Kemp, Pierre, Norbert de Vries

Een Egyptische weduwe

bij het schilderij van Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Wij weten nu dat deze schilder wist

dat eeuwen her zich deze dode

als een mummie naar de toekomst wrong

in uitgeleefde luchten en vluchtte

in hiernamaalsen waarin hij zelf

geloofde. Ter plekke zong de twijfel:

men roofde graven leeg en zweeg en

daarom neuriet er de hoop dat

rust hier mag gaan heersen.

De weduwe treurt diep maar ondertussen

leert ze van het sterven: het lot

vermomt zich graag als einde.

Bert Bevers

(uit Afglans – Gedichten 1972-1997, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 1997)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Charles Cros

(1842-1888)

Testament

Si mon âme claire s’éteint

Comme une lampe sans pétrole,

Si mon esprit, en haut, déteint

Comme une guenille folle,

Si je moisis, diamantin,

Entier, sans tache, sans vérole,

Si le bégaiement bête atteint

Ma persuasive parole,

Et si je meurs, soûl, dans un coin

C’est que ma patrie est bien loin

Loin de la France et de la terre.

Ne craignez rien, je ne maudis

Personne. Car un paradis

Matinal, s’ouvre et me fait taire.

Charles Cros poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cros, Charles

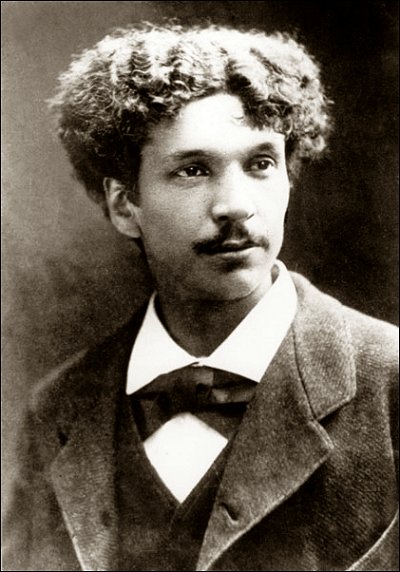

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

The Elephant is Slow to Mate

The elephant, the huge old beast,

is slow to mate;

he finds a female, they show no haste

they wait

for the sympathy in their vast shy hearts

slowly, slowly to rouse

as they loiter along the river-beds

and drink and browse

and dash in panic through the brake

of forest with the herd,

and sleep in massive silence, and wake

together, without a word.

So slowly the great hot elephant hearts

grow full of desire,

and the great beasts mate in secret at last,

hiding their fire.

Oldest they are and the wisest of beasts

so they know at last

how to wait for the loneliest of feasts

for the full repast.

They do not snatch, they do not tear;

their massive blood

moves as the moon-tides, near, more near

till they touch in flood.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

foto joost bataille

Esther Porcelijn

Bloemlezen en Koffiedik kijken

op de Roze Maandag

Lights On

Daar gaan we Weer Weer WEER Weer.

Zonder ideeën ben ik er niet

Zonder ideeën zijn jullie er niet

Zonder de mensen is er niks

om over te praten.

Zonder verschillen kunnen we alles

stilzwijgend ondergaan.

Dan gaan de lichten op de dimstand.

De grootste beren op de Roze rots,

Komrij’s Paralymics.

Het anders-zijn wordt juist benadrukt?

Met z’n allen in een draaimolen,

de carrousel.

Alle plaatjes van mensen in de centrifuge

tot oliebolsap.

Allemaal hetzelfde,

behalve op Roze maandag.

Nog een Keer Keer KEER Keer.

Online bashen, inmaken oprotten optiefen onder de lakens houden, achter de voordeur. “Mij maakt het niet uit hoor,” als ze maar niet ehm zoenen op straat, ehm handen vasthouden, ehm genegenheid tonen, ehm mij aankijken, ehm iets roze-achtigs doen, ehm of denken, ehm ademen, of ehm leven.

“Het is een ziekte,”

“homo’s zijn dierlijk.”

Nieuw Nieuw NIEUW Nieuw

Oproer uit de jaren 50.

Conservatisme is de allergrootste traditie.

Misplaatste frustratie

van anoniem-schreeuwers is

de online munitie

waar we met z’n allen in draaien.

Zij met de grootste aannames nemen

nooit iets aan van anderen,

want dat is een no-Go Go GO Go.

Dansers in kooien, harde sex, slappe handjes,

roze boa’s, darkrooms.

Cliché Cliché CLICHÉ Cliché.

Niet te verdragen.

Erger nog dan Jonge Sla.

Gay. What’s in a name?

Mo money mo homo mo homo mo homo

Geld waard.

Straks mis je nog de Bootsma.

Geld waard, twee voor de prijs van

Één Één ÉÉN Één.

Benadruk het anders zijn,

anders doet niemand het,

gaan de lichten op dimstand.

Zwieren en draaien.

Daar gaan We We WE We

Weer Weer WEER Weer.

Het evenement ‘Roze Maandag’ maakt onderdeel uit van de Tilburgse Kermis, juli 2012. Het gedicht ‘Bloemlezen en Koffiedik kijken op de Roze Maandag’ werd eerder gepubliceerd in het Brabants Dagblad.

esther porcelijn poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, LGBT+ (lhbt+), Porcelijn, Esther

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature