Fleurs du Mal Magazine

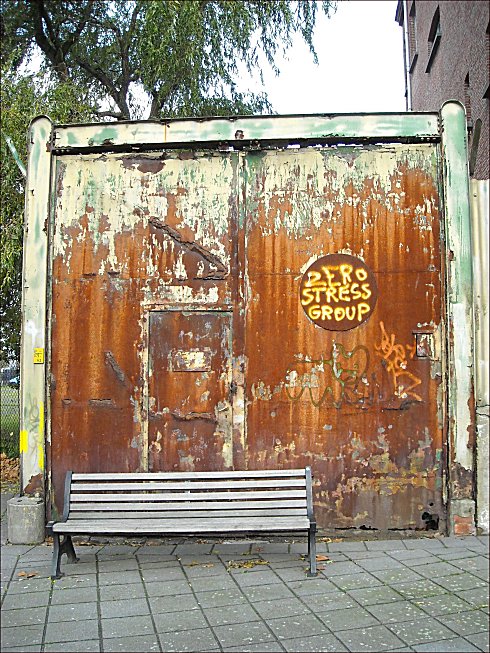

Street poetry: Zero stress group (Antwerpen)

photo fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Street Art

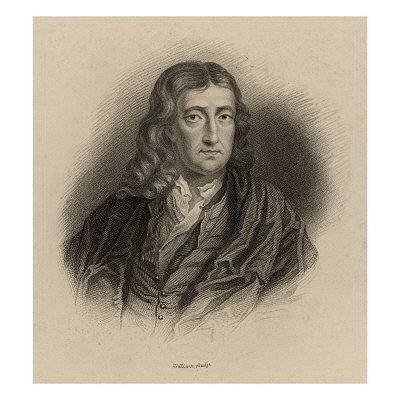

John Milton

(1608-1674 )

Anno ætatis 17.

On the Death of a Fair Infant Dying of a Cough

I

O Fairest flower no sooner blown but blasted,

Soft silken Primrose fading timelesslie,

Summers chief honour if thou hadst out-lasted

Bleak winters force that made thy blossome drie;

For he being amorous on that lovely die

That did thy cheek envermeil, thought to kiss

But kill’d alas, and then bewayl’d his fatal bliss.

II

For since grim Aquilo his charioter

By boistrous rape th’ Athenian damsel got,

He thought it toucht his Deitie full neer,

If likewise he some fair one wedded not,

Thereby to wipe away th’ infamous blot,

Of long-uncoupled bed, and childless eld,

Which ‘mongst the wanton gods a foul reproach was held.

III

So mounting up in ycie-pearled carr,

Through middle empire of the freezing aire

He wanderd long, till thee he spy’d from farr,

There ended was his quest, there ceast his care.

Down he descended from his Snow-soft chaire,

But all unwares with his cold-kind embrace

Unhous’d thy Virgin Soul from her fair biding place.

IV

Yet art thou not inglorious in thy fate;

For so Apollo, with unweeting hand

Whilome did slay his dearly-loved mate

Young Hyacinth born on Eurotas strand,

Young Hyacinth the pride of Spartan land;

But then transform’d him to a purple flower

Alack that so to change thee winter had no power.

V

Yet can I not perswade me thou art dead

Or that thy coarse corrupts in earths dark wombe,

Or that thy beauties lie in wormie bed,

Hid from the world in a low delved tombe;

Could Heav’n for pittie thee so strictly doom?

Oh no? for something in thy face did shine

Above mortalitie that shew’d thou wast divine.

VI

Resolve me then oh Soul most surely blest

(If so it be that thou these plaints dost hear)

Tell me bright Spirit where e’re thou hoverest

Whether above that high first-moving Spheare

Or in the Elisian fields (if such there were.)

Oh say me true if thou wert mortal wight

And why from us so quickly thou didst take thy flight.

VII

Wert thou some Starr which from the ruin’d roof

Of shak’t Olympus by mischance didst fall;

Which carefull Jove in natures true behoofe

Took up, and in fit place did reinstall?

Or did of late earths Sonnes besiege the wall

Of sheenie Heav’n, and thou some goddess fled

Amongst us here below to hide thy nectar’d head.

VIII

Or wert thou that just Maid who once before

Forsook the hated earth, O tell me sooth,

And cam’st again to visit us once more?

Or wert thou that sweet smiling Youth!

Or that crown’d Matron sage white-robed truth?

Or any other of that heav’nly brood

Let down in clowdie throne to do the world some good.

IX

Or wert thou of the golden-winged hoast,

Who having clad thy self in humane weed,

To earth from thy præfixed seat didst poast,

And after short abode flie back with speed,

As if to shew what creatures Heav’n doth breed,

Thereby to set the hearts of men on fire

To scorn the sordid world, and unto Heav’n aspire.

X

But oh why didst thou not stay here below

To bless us with thy heav’n-lov’d innocence,

To slake his wrath whom sin hath made our foe

To turn Swift-rushing black perdition hence,

Or drive away the slaughtering pestilence,

To stand ‘twixt us and our deserved smart

But thou canst best perform that office where thou art.

XI

Then thou the mother of so sweet a child

Her false imagin’d loss cease to lament,

And wisely learn to curb thy sorrows wild;

Think what a present thou to God hast sent,

And render him with patience what he lent;

This if thou do, he will an off-spring give

That till the worlds last end shall make thy name to live.

John Milton poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Milton, John

Hans Warren

(1921-2001)

Terugkeer

We liepen door het late land. De bomen

geurden bedwelmend en de zomerlucht was zwaar.

Duister schoof over vers gemaaide klaver.

De wind kwam als een warm en tastbaar aaien

onder de hemel, spiegelend in een meer

op blauwgroen fond zijn ambergele wolkenvlokken.

Er klonk vreemde muziek, die ik vergat.

We zagen achter wijde velden spitse torens,

gerezen aan de duistere einderboog

tegen het stil verschilferd koepelparelmoer.

Er was gefluister en gegiechel langs de wegen

en bladerschaduw als een lokkend grottenhol.

Terugkeer. Dit nooit kunnen verwoorden:

terugkeer door de zomeravond, naar huis,

maar niet mijn huis, het onvolmaakte.

Dit was nóóit samen, altijd heel alleen,

de lucht moest warmer zijn dan bloed,

het licht heel rood verguld, de geuren

bijna verstikkend zwaar. Een ander paar

moest ergens dwalen, een veel gelukkiger

en mooier paar, en een jonge landman zong

of oefende in een tuin op een trombone.

En nooit heb ik dat huis bereikt, maar soms

in dromen ben ik nog op weg daarheen.

![]()

(Uit: Hans Warren: ‘Verzamelde gedichten’, Amsterdam 2002)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X

Street poetry: Eén van de pinguïns loopt mank

(Safaripark Beekse Bergen Hilvarenbeek)

photo fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Street Art

Dat kan mijn kleine zusje ook!

(Henk & Ingrid)

http://www.henkeningrid.org/

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, The talk of the town

Renée Crevel

(1900-1935)

Elle ne suffit l’éloquence

Elle ne suffit pas l’éloquence.

Mon cœur ce soir se balance

Et glisse au fil d’une paupière

Lampion de misère

Qui n’éclaire pas ma nuit.

Homme noir mais non d’onyx

Homme couleur de dépit

Titubant par le marais des petites haines

Tu voudrais

Comme une alouette son miroir

Un soleil où mourir avec ta peine.

Tu cherches mais trop inquiet

Pour trouver ton Reposoir.

Rien ne brille

Ni les yeux, ni le fer, ni l’aimant anonyme

Qui libèrent de mille clous

Tes douleurs

Où l’essaim des mouches au vol boiteux

Des mouches qui n’ont qu’une aile

Allument de piètres étoiles de sang.

Jongleur

Jongleur de paroles

Tes mots s’écrasent contre les murs.

Ton angoisse –encore un ruban frivole–

Couronne

Un cerveau qui trop longtemps a joué au « pigeon vole ».

Les lettres du désespoir

Ce soir

Sont égales aux lettres des bonheurs d’autrefois.

Que dirai-je alors !

Que te dirai-je à toi

Frère né de mes pieds.

Sur un sol où tu ne vis que pour m’épier.

Trottoir que j’ai suivi

Pour son mensonge de granit.

J’ai oublié que là-bas était la mer

Et j’ai fui l’eau miroir d’étoiles

Pour chanter une main

Dans une autre main.

Fleuve vert

Enfance douce

Pitié pour l’homme qui passe

L’homme qui mord sa lèvre

Dans ses lèvres

Car il a peur d’oublier le goût de bouche.

Timonier brun, sous la toile bleue

La peau couler de cheveux

Holà ! beau voyageur

Tu allais vers la mer

Maintenant tu marches au ciel, un trou un hublot

Je suis le noyé des terres.

Dis qu’il n’est pas trop tard

O mon orgueil, pour jouer au phare.

Et sur le matelas des herbes tendres

Tombe en triangles de métal.

Mon cœur aura beau hurler son mal

Mon cœur j’en ferai des lanières

Des lanières que je saurai teindre

Ou tordre en chiffres

Plus définitifs

Que les œufs dans leurs coquilles

Et les momies dans leur robe d’or.

Et toi, mon corps, maudis les sens comme un malade ses béquilles.

1924

Renée Crevel poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crevel, Renée

John Milton

(1608-1674 )

On the University Carrier who sickn’d in the time of his vacancy, being forbid to go to London, by reason of the Plague

Here lies old Hobson, Death hath broke his girt,

And here alas, hath laid him in the dirt,

Or els the ways being foul, twenty to one,

He’s here stuck in a slough, and overthrown.

‘Twas such a shifter, that if truth were known,

Death was half glad when he had got him down;

For he had any time this ten yeers full,

Dodg’d with him, betwixt Cambridge and the Bull.

And surely, Death could never have prevail’d,

Had not his weekly cours of carriage fail’d;

But lately finding him so long at home,

And thinking now his journeys end was come,

And that he had tane up his latest Inne,

In the kind office of a Chamberlin

Shew’d him his room where he must lodge that night,

Pull’d off his Boots, and took away the light:

If any ask for him, it shall be sed,

Hobson has supt, and ‘s newly gon to bed.

Another on the Same

Here lieth one who did most truly prove,

That he could never die while he could move,

So hung his destiny never to rot

While he might still jogg on, and keep his trot,

Made of sphear-metal, never to decay

Untill his revolution was at stay.

Time numbers motion, yet (without a crime

‘Gainst old truth) motion number’d out his time;

And like an Engin mov’d with wheel and waight,

His principles being ceast, he ended strait,

Rest that gives all men life, gave him his death,

And too much breathing put him out of breath,

Nor were it contradiction to affirm

Too long vacation hastned on his term.

Meerly to drive the time away he sickn’d,

Fainted, and died, nor would with Ale be quickn’d;

Nay, quoth he, on his swooning bed outstretch’d,

If I may not carry, sure Ile ne’re be fetch’d,

But vow though the cross Doctors all stood hearers,

For one Carrier put down to make six bearers.

Ease was his chief disease, and to judge right,

He di’d for heavines that his Cart went light,

His leasure told him that his time was com,

And lack of load, made his life burdensom,

That even to his last breath (ther be that say’t)

As he were prest to death, he cry’d more waight;

But had his doings lasted as they were,

He had bin an immortall Carrier.

Obedient to the Moon he spent his date

In cours reciprocal, and had his fate

Linkt to the mutual flowing of the Seas,

Yet (strange to think) his wain was his increase:

His Letters are deliver’d all and gon,

Onely remains this superscription.

John Milton poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Milton, John

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (02)

Shoot! (Si Gira. 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio,

Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

OF THE NOTES OF SERAFINO GUBBIO, CINEMATOGRAPH OPERATOR

2

I satisfy, by writing, a need to let off steam which is overpowering.

I get rid of my professional impassivity, and avenge myself as well; and with myself avenge ever so many others, condemned like myself to be nothing more than ‘a hand that turns a handle’.

This was bound to happen, and it has happened at last!

Man who first of all, as a poet, deified his own feelings and worshipped them, now having flung aside every feeling, as an

encumbrance not only useless but positively harmful, and having become clever and industrious, has set to work to fashion out of iron and steel his new deities, and has become a servant and a slave to them.

Long live the Machine that mechanises life!

Do you still retain, gentlemen, a little soul, a little heart and a little mind? Give them, give them over to the greedy machines, which are waiting for them! You shall see and hear the sort of product, the exquisite stupidities they will manage to extract from them.

To pacify their hunger, in the urgent haste to satiate them, what food can you extract from yourselves every day, every hour, every minute?

It is, perforce, the triumph of stupidity, after all the ingenuity and research that have been expended on the creation of these monsters, which ought to have remained instruments, and have instead become, perforce, our masters.

The machine is made to act, to move, it requires to swallow up our soul, to devour our life. And how do you expect them to be given back to us, our life and soul, in a centuplicated and continuous output, by the machines? Let me tell you: in bits and morsels, all of one pattern, stupid and precise, which would make, if placed one on top of another, a pyramid that might reach to the stars. Stars, gentlemen, no! Don’t you believe it. Not even to the height of a telegraph pole. A breath stirs it and down it tumbles, and leaves such a litter, only not inside this time but outside us, that–Lord, look at all the boxes, big, little, round, square–we no longer know where to set our feet, how to move a step. These are the products of our soul, the pasteboard boxes of our life.

What is to be done? I am here. I serve my machine, in so far as I turn the handle so that it may eat. But my soul does not serve me. My hand serves me, that is to say serves the machine. The human soul for food, life for food, you must supply, gentlemen, to the machine whose handle I turn. I shall be amused to see, with your permission, the product that will come out at the other end. A fine product and a rare entertainment, I can promise you.

Already my eyes and my ears too, from force of habit, are beginning to see and hear everything in the guise of this rapid, quivering, ticking mechanical reproduction.

I don’t deny it; the outward appearance is light and vivid. We move, we fly. And the breeze stirred by our flight produces an alert, joyous, keen agitation, and sweeps away every thought. On! On, that we may not have time nor power to heed the burden of sorrow, the degradation of shame which remain within us, in our hearts. Outside, there is a continuous glare, an incessant giddiness: everything flickers and disappears.

“What was that?” Nothing, it has passed! Perhaps it was something sad; but no matter, it has passed now.

There is one nuisance, however, that does not pass away. Do you hear it? A hornet that is always buzzing, forbidding, grim, surly,diffused, and never stops. What is it? The hum of the telegraph poles? The endless scream of the trolley along the overhead wire of the electric trams? The urgent throb of all those countless machines, near and far? That of the engine of the motor-car? Of the cinematograph?

The beating of the heart is not felt, nor do we feel the pulsing of our arteries. The worse for us if we did! But this buzzing, this perpetual ticking we do notice, and I say that all this furious haste is not natural, all this flickering and vanishing of images; but that there lies beneath it a machine which seems to pursue it, frantically screaming.

Will it break down?

Ah, we must not fix our attention upon it too closely. That would arouse in us an ever-increasing fury, an exasperation which finally we could endure no longer; would drive us mad.

On nothing, on nothing at all now, in this dizzy bustle which sweeps down upon us and overwhelms us, ought we to fix our attention. Take in, rather, moment by moment, this rapid passage of aspects and events, and so on, until we reach the point when for each of us the buzz shall cease.

(to be continued)

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (02)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Dopo un anno, il re prese di nuovo moglie: una donna bella, ma orgogliosa; non poteva tollerare che qualcuno la superasse in bellezza. Possedeva uno specchio e, quando vi si specchiava, diceva:-Specchio fatato, in questo castello, hai forse visto aspetto più bello?-E lo specchio rispondeva:-E’ il tuo, Regina, di tutte il più bello!-Ed ella era contenta, perché‚ sapeva che lo specchio diceva la verità. Ma Biancaneve cresceva, diventando sempre più bella e, quand’ebbe sette anni, era Revolution zum Handeln zu gelangen. Die Herausgeberinnen haben 15 Autorinnen aus Asien, Afrika, Europa, Australien, Ozeanien sowie den beiden Amerikas gebeten, die Zukunft aus einer kosmopolitischen Sicht zu entwerfen und damit die Lebenskunst nach Platon und Aristoteles-..

J.A. Woolf: Making memories (04)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: J.A. Woolf, J.A. Woolf

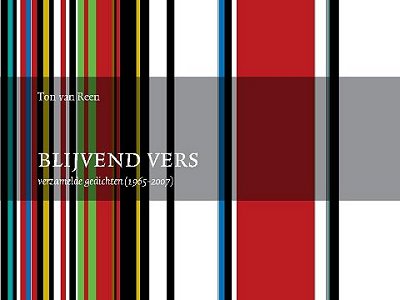

Ton van Reen

wit licht

Wit licht uit de hutten

wit de witte graanschuren

wit de rode bomen, wit de zwarte dieren

wit de adem van het dorp

die wit boven de hutten van wit riet hangt

Het licht wit het stof van de zwarte straten

wit stof wit de bruine ezels

wit stof wit de zwarte kinderen

zwarte kinderen zijn wit

in wit licht

zwarte kinderen zijn witter dan wit

Het witte stof wit het licht

het witte stof van de witte straat

het witte stof

van de witbestoven ezels

het witte licht van de zwarte kinderen

die wit stof tegen het witte licht blazen

Uit: Ton van Reen, Blijvend vers, Verzamelde gedichten (1965-2007). Uitgeverij De Contrabas, 2011, ISBN 9789079432462, 144 pagina’s, paperback

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

.jpg)

Paul Boldt

(1885-1921)

DER FRAUENTOD

Der Tod umarmt mich in den warmen Frauen.

Beischlaf erregt, zersetzt die Moleküle.

Ich wandre durch Provinzen der Gefühle

Der Freude ab und komme in das Grauen.

Dich, Dirne, macht die Nacktheit antlitzschön.

Heiliges Fleisch steht auf den Knien im Haar.

Ich liege bei dir, lächelnd, am Altar,

Dem Tod entrückt auf deiner Brüste Höhen.

Aber nach den Umarmungen, nach allem

Durchscheinen jedes Fleisch die hellen Knochen.

Die Muskeln schimmern am Skelett, zerfallen.

Ich sterbe. Niemand hat zu mir gesprochen.

Irrsinnig lasse ich mich sagen, lallen,

Und fühle dich vor Blut und Brüsten kochen.

Paul Boldt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Boldt, Paul, Expressionism

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

(1772-1834)

Frost at Midnight

The Frost performs its secret ministry,

Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry

Came loud – and hark, again! loud as before.

The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,

Have left me to that solitude, which suits

Abstruser musings: save that at my side

My cradled infant slumbers peacefully.

‘Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,

This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood,

With all the numberless goings-on of life,

Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Methinks its motion in this hush of nature

Gives it dim sympathies with me who live,

Making it a companionable form,

Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling Spirit

By its own moods interprets, everywhere

Echo or mirror seeking of itself,

And makes a toy of Thought.

But O! how oft,

How oft at school, with most believing mind,

Presageful, have I gazed upon the bars,

To watch that fluttering stranger! and as oft

With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt

Of my sweet birthplace, and the old church tower,

Whose bells, the poor man’s only music, rang

From morn to evening, all the hot fair-day,

So sweetly, that they stirred and haunted me

With a wild pleasure, falling on mine ear

Most like articulate sounds of things to come!

So gazed I, till the soothing things, I dreamt,

Lulled me to sleep, and sleep prolonged my dreams!

And so I brooded all the following morn,

Awed by the stern preceptor’s face, mine eye

Fixed with mock study on my swimming book:

Save if the door half opened, and I snatched

A hasty glance, and still my heart leaped up,

For still I hoped to see the stranger’s face,

Townsman, or aunt, or sister more beloved,

My playmate when we both were clothed alike!

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the interspersèd vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

My babe so beautiful! it thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee,

And think that thou shalt learn far other lore,

And in far other scenes! For I was reared

In the great city, pent ‘mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mold

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple tree, while the nigh thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

1798

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Vorst te middernacht

De vorst werkt stil aan zijn geheime taak,

Geen wind die daarbij helpt. Het uiltje gaf

Zijn luide roep – en hoor, weer! even luid.

Alle bewoners van mijn stulpje slapen nu,

En bieden mij afzondering, die past

Bij diepergaand gepeins: behalve dan

Dat naast mij kalm mijn wiegekindje rust.

Hoe vredig! Zo zeer, dat ‘t bezinning stoort

En tegenwerkt door buitensporige

En vreemde stilligheid. Zee, heuvel, bos,

Dit volk-rijk dorp! Zee, heuvel, bos,

Met al die grote drukte van ‘t bestaan,

Onhoorbaar als een droom! De dunne vlam

Dekt blauw mijn smeulend vuur, en wappert niet;

Maar ‘n film, die trillend op het rooster lag,

Trilt nu nog steeds, en stoort de rust alleen.

Medunkt die onrust in de stilte der natuur

Geeft het wat meegevoel met mij die leeft,

Waardoor zich ‘n deelgenootschap vormt,

En, sluimerend, de geest ‘t zwak fladderen

Door de eigen stemmingen verklaart, op zoek

Naar echo’s of een spiegel van zichzelf,

En spel maakt van gepeins.

Maar O! hoe vaak,

Hoe vaak op school, in goedgelovigheid,

Staard’ ik met voorgevoel de spijlen aan,

En zag die fladderende vreemde! * Vaak

Ook had ik, d’ ogen open, zoet gedroomd

Van waar mijn wieg stond, van de kerkklok,

De enige muziek der arme man, die klonk

Van vroeg tot laat, de ganse, warme dag,

Zo lieflijk, dat het mij ontroerde en greep

Met wild plezier, en in mijn oren zonk

Als ‘t klinkklaar luiden van wat komen zou!

Zo staarde ik, tot ik kalmerend door die droom,

In slaap viel, en die droom weer langer werd!

Zo mijmerde ik de dag daarop nog door.

Mijn oog, bevreesd voor meester’s strenge blik,

Kleefde al spijbelend aan mijn drijvend boek:

Behalve als bij open deur, ik snel

Een blik wierp, en mijn hart weer opsprong,

Want steeds nog keek ik naar de vreemde uit,

Stedeling, tante, zuster meer geliefd,

Mijn makker, nog gelijk gekleed als ik!

Lief kindje, naast mij slapend in je wieg,

Wiens zachte adem, hoorbaar in de rust,

De leemtes en de korte pauzes soms

Verspreid in de gedachtenstromen vult!

Mijn kind, zo schoon! Het schenkt mijn hart

Een tere vreugd, als ik zo naar je kijk,

En weet dat jij veel, anders leren zult,

En in heel ander landschap ook! Want ik

Groeide gekloosterd als een stadskind op,

En zag aan schoons slechts sterren en de lucht.

Maar jij, mijn kind, zult zwerven als een bries

Aan meer en oever, onder aan de kloof

Van ‘n oude berg, en onder ‘t wolkendek,

Dat in zijn opbouw oever, meer, en kloof

Verbeeldt: zo zul je zien en horen ook

De liefelijke vormen en bevattelijke klank

Van die onsterfelijke taal, door God

Gesproken, die zich eeuwig onderwijst

In ‘t al, en alle dingen in Zichzelf.

De grote algehele Leraar! Hij boetseert

Je geest, and zorgt door geven dat die vraagt.

Daarom zal elk seizoen je dierbaar zijn,

Of nu de zomer heel de aarde kleedt

In ‘t groen, of ‘t roodborstje zit en zingt

Tussen de plekjes sneeuw op ‘n kale tak

Van een bemoste appelboom, terwijl

Het rietdak dampt in zonnedooi; of nu

Dakdruppels spetteren bij geluwde wind,

Of dat, door de geheime taak der vorst,

Ze onhoorbaar neerhangen als ijspegels,

In stilte schijnend naar de stille maan.

* Vreemde: de roetfilm die boven het rooster zweeft wordt “overal in het land vreemde genoemd en kondigt de komst van een afwezige bekende aan” (aantekening van Coleridge)

Vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Uit: Bestorm mijn hart, de beste Engelse gedichten uit de 16e-19e eeuw gekozen en vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld, tweetalige editie. Rainbow Essentials no. 55, Uitgeverij Maarten Muntinga, Amsterdam, 2008, 296 pp, € 9,95 ISBN: 9789041740588

Kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Coleridge, Coleridge, Samuel Taylor

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature