Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

D e b i o g r a f i e

Een wetenschappelijk en literair genre

Studium Generale Universiteit Utrecht & SLAU

19 oktober – 9 november 2010

De biografie is begonnen als wetenschappelijk genre, maar heeft een enorme opmars gemaakt buiten de universiteit. Niet alleen belangrijke en historische figuren als Renate Rubinstein en prins Bernhard krijgen hun biografie, ook de ‘gewone man’ staat in de belangstelling, net als de familiegeschiedenis.

Waarom lezen we zo graag tot in detail over het leven van een ander? En hoe is het om jarenlang onderzoek te doen in persoonlijke archieven? Literaire biografieën draaien soms om mythevorming en schandaal: het verhaal gaat een eigen leven leiden. Vaker is er sprake van ontmythologisering: een grote figuur als Napoleon wordt van zijn voetstuk gestoten door hem al te menselijk voor te stellen.

Wetenschappelijke biografieën moeten vlot geschreven zijn, zonder te bezwijken aan een overvloed aan historisch bewijs. Maar hoe zit het met dat bewijs? Biografen van historische personen missen hun primaire bron. Dagboeken en getuigenissen worden soms geschreven met het oog op de toekomstige lezer. Hoe ontrafel je schijn en werkelijkheid? De opkomst van de nieuwe media maakt dit nog lastiger. Ook bij nog levende personen ontstaan moeilijkheden: hoe verhoudt de biograaf zich tot zijn onderwerp? Kun je wel objectief over een ander mens schrijven? En vraagt de lezer daar wel om?

Dit programma kwam tot stand i.s.m. Stichting Literaire Activiteiten Utrecht (SLAU).

![]()

Programma

Dinsdag 19 oktober

Op afstand. De biograaf en zijn onderwerp

Prof. dr. Hans Renders (Biografie Instituut RuG) en Onno Blom (schrijver en journalist)

Live / Opname

De biografie is van een wetenschappelijk genre beoefend aan de universiteit uitgegroeid tot publiekslieveling. Wat betekent dat voor de eisen die aan een biografie gesteld worden? Volgens prof. Hans Renders moet een wetenschappelijke biografie even goed geschreven zijn als een literaire roman. Hoe kenmerkt zich dan een wetenschappelijk verantwoorde biografie? Hoe zit het met zaken als objectiviteit en de betrokkenheid bij het onderwerp? Deze vragen komen ook naar voren in het werk van Onno Blom. Blom leerde als biograaf van Jan Wolkers zijn onderwerp goed kennen. Hoe houd je de benodigde afstand als er een vriendschappelijke relatie tussen biograaf en gebiografeerde ontstaat? Of is die afstand hoe dan ook een illusie?

Dinsdag 26 oktober

Verborgen geschiedenissen. Dagboek en archief

Dr. Jolande Withuis (socioloog, NIOD) en Annejet van der Zijl (schrijver)

Live / Opname

Dr. Jolande Withuis schreef een biografie van verzetsheld Pim Boellaard, bekroond met de Erik Hazelhoff Biografieprijs 2010. Hoe gaat zo’n jarenlang project in z’n werk? Het schrijven over een vaderlandse held, maakt dat een eigen interpretatie van het beschreven leven niet lastig? Biografen zitten jarenlang ‘verstopt’ in archieven, snuffelen in dagboeken en sporen getuigen op, soms de laatste die nog leven, in andere gevallen getuigen die alleen bestaan op papier. Annejet van der Zijl schreef biografieën van Annie M.G. Schmidt en recentelijk van Prins Bernhard. Personen waar een publieke beeldvorming van bestaat. Biografie en beeldvorming kunnen elkaar wederzijds beïnvloeden – eenmaal uit het archief naar boven gekomen, gaat de biografie een leven leiden in de publieke sfeer.

Dinsdag 2 november

Het verhaal van je leven. Literatuur en filosofie

Hans Goedkoop (historicus en biograaf) en prof. dr. Joachim Duyndam (Wijsbegeerte, UvH)

Live / Opname

Waarom lezen mensen graag biografieën? Wat levert het op om je te verdiepen in het leven van een ander? Aan de ene kant kan een biografie een visie geven op het werk van een schrijver, kunstenaar of historisch figuur. Maar de biografie leert ook iets over je eigen leven. Hans Goedkoop, biograaf en literatuurbeschouwer, stelt dat de biografie een perspectief toevoegt aan het leven, en antwoord geeft op de vraag hoe we betekenis geven aan het leven. Prof. Joachim Duyndam benadert het levensverhaal vanuit de humanistiek. Welke functie kan een biografie, of meer algemeen levensverhalen, vervullen in de zoektocht naar identiteit en het vormgeven van je eigen leven?

Dinsdag 9 november

De mens als mythe. Pessoa en Lorca

Michaël Stoker (Literatuurwetenschap, UU) en Peter Valkenet (vertaler Spaans)

Let op, programmawijziging t.o.v. brochure!

Meer horen over Lorca? 7 t/m 21 november vindt het Lorca Festival plaats in Utrecht

Live / Opname

In de laatste lezing komen twee internationale grootheden aan bod: Fernando Pessoa en Federico Garcia Lorca. Schrijvers die sinds hun dood bijna mythische proporties hebben aangenomen. Michaël Stoker doet onderzoek naar Pessoa, die in thuisland Portugal zo’n status heeft dat hij bijna uit het wetenschappelijke veld verdwenen is. Wat kun je schrijven over een nationale mythe? En hoe ga je om met de talloze heteroniemen, oftewel verschillende persona’s, die Pessoa voor zichzelf schiep? De mythevorming rond Lorca heeft verregaande consequenties gehad: een juridische strijd leidde tot het openen van het massagraf waarin zijn stoffelijke resten zouden liggen. Het graf was leeg.

Peter Valkenet vertelt over de fascinatie voor dit soort verhalen. Hoe is biografie verweven met cultuurgeschiedenis en actualiteit?

Aula van het Academiegebouw, Utrecht

Tijd: 20.00 tot 21.30 uur

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Annie M.G. Schmidt, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, Jan Wolkers

.jpg)

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Attente

Monte, écureuil, monte au grand chêne,

Sur la branche des cieux prochaine,

Qui plie et tremble comme un jonc.

Cigogne, aux vieilles tours fidèle,

Oh ! vole et monte à tire-d’aile

De l’église à la citadelle,

Du haut clocher au grand donjon.

Vieux aigle, monte de ton aire

A la montagne centenaire

Que blanchit l’hiver éternel.

Et toi qu’en ta couche inquiète

Jamais l’aube ne vit muette,

Monte, monte, vive alouette,

Vive alouette, monte au ciel !

Et maintenant, du haut de l’arbre,

Des flèches de la tour de marbre,

Du grand mont, du ciel enflammé,

A l’horizon, parmi la brume,

Voyez-vous flotter une plume

Et courir un cheval qui fume,

Et revenir mon bien-aimé ?

Hans Hermans photos

Victor Hugo poetry

Hans Hermans Natuurdagboek – Augustus 2010

► Website Hans Hermans Fotografie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Hugo, Victor

.jpg)

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

The Danger of Lying in Bed

The man in the ticket-office said:

“Have an accident insurance ticket, also?”

“No,” I said, after studying the matter over a little.

“No, I believe not; I am going to be travelling by rail all day to-day. However, to-morrow I don’t travel. Give me one for to-morrow.”

The man looked puzzled. He said:

“But it is for accident insurance, and if you are going to travel by rail—”

“If I am going to travel by rail I sha’n’t need it. Lying at home in bed is the thing I am afraid of.”

I had been looking into this matter. Last year I travelled twenty thousand miles, almost entirely by rail; the year before, I travelled over twenty-five thousand miles, half by sea and half by rail; and the year before that I travelled in the neighborhood of ten thousand miles, exclusively by rail. I suppose if I put in all the little odd journeys here and there, I may say I have travelled sixty thousand miles during the three years I have mentioned. And never an accident.

For a good while I said to myself every morning:

“Now I have escaped thus far, and so the chances are just that much increased that I shall catch it this time. I will be shrewd, and buy an accident ticket.” And to a dead moral certainty I drew a blank, and went to bed that night without a joint started or a bone splintered. I got tired of that sort of daily bother, and fell to buying accident tickets that were good for a month. I said to myself, “A man can’t buy thirty blanks in one bundle.”

But I was mistaken. There was never a prize in the lot. I could read of railway accidents every day—the newspaper atmosphere was foggy with them; but somehow they never came my way. I found I had spent a good deal of money in the accident business, and had nothing to show for it. My suspicions were aroused, and I began to hunt around for somebody that had won in this lottery. I found plenty of people who had invested, but not an individual that had ever had an accident or made a cent. I stopped buying accident tickets and went to ciphering. The result was astounding. The Peril Lay not in Travelling, but in staying at home.

I hunted up statistics, and was amazed to find that after all the glaring newspaper headings concerning railroad disasters, less than three hundred people had really lost their lives by those disasters in the preceding twelve months. The Erie road was set down as the most murderous in the list. It had killed forty-six—or twenty-six, I do not exactly remember which, but I know the number was double that of any other road. But the fact straightway suggested itself that the Erie was an immensely long road, and did more business than any other in the country; so the double number of killed ceased to be matter for surprise.

By further figuring, it appeared that between New York and Rochester the Erie ran eight passenger trains each way every day—sixteen altogether; and carried a daily average of 6000 persons. That is about a million in six months—the population of New York City. Well, the Erie kills from thirteen to twenty- three persons out of its million in six months; and in the same time 13,000 of New York’s million die in their beds! My flesh crept, my hair stood on end. “This is appalling!” I said. “The danger isn’t in travelling by rail, but in trusting to those deadly beds. I will never sleep in a bed again.”

I had figured on considerably less than one-half the length of the Erie road. It was plain that the entire road must transport at least eleven or twelve thousand people every day. There are many short roads running out of Boston that do fully half as much; a great many such roads. There are many roads scattered about the Union that do a prodigious passenger business. Therefore it was fair to presume that an average of 2500 passengers a day for each road in the country would be about correct. There are 846 railway lines in our country, and 846 times 2500 are 2,115,000. So the railways of America move more than two millions of people every day; six hundred and fifty millions of people a year, without counting the Sundays. They do that, too—there is no question about it; though where they get the raw material is clear beyond the jurisdiction of my arithmetic; for I have hunted the census through and through, and I find that there are not that many people in the United States, by a matter of six hundred and ten millions at the very least. They must use some of the same people over again, likely.

San Francisco is one-eighth as populous as New York; there are 60 deaths a week in the former and 500 a week in the latter—if they have luck. That is 3120 deaths a year in San Francisco, and eight times as many in New York—say about 25,000 or 26,000. The health of the two places is the same. So we will let it stand as a fair presumption that this will hold good all over the country, and that consequently 25,000 out of every million of people we have must die every year. That amounts to one-fortieth of our total population. One million of us, then, die annually. Out of this million ten or twelve thousand are stabbed, shot, drowned, hanged, poisoned, or meet a similarly violent death in some other popular way, such as perishing by kerosene lamp and hoop-skirt conflagrations, getting buried in coal-mines, falling off house-tops, breaking through church or lecture-room floors, taking patent medicines, or committing suicide in other forms. The Erie railroad kills from 23 to 46; the other 845 railroads kill an average of one-third of a man each; and the rest of that million, amounting in the aggregate to the appalling figure of nine hundred and eighty-seven thousand six hundred and thirty-one corpses, die naturally in their beds!

You will excuse me from taking any more chances on those beds. The railroads are good enough for me.

And my advice to all people is, Don’t stay at home any more than you can help; but when you have got to stay at home a while, buy a package of those insurance tickets and sit up nights. You cannot be too cautious.

[One can see now why I answered that ticket-agent in the manner recorded at the top of this sketch.]

The moral of this composition is, that thoughtless people grumble more than is fair about railroad management in the United States. When we consider that every day and night of the year full fourteen thousand railway trains of various kinds, freighted with life and armed with death, go thundering over the land, the marvel is, not that they kill three hundred human beings in a twelvemonth, but that they do not kill three hundred times three hundred!

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

Amy Levy

(1861-1889)

A Greek Girl

I may not weep, not weep, and he is dead.

A weary, weary weight of tears unshed

Through the long day in my sad heart I bear;

The horrid sun with all unpitying glare

Shines down into the dreary weaving-room,

Where clangs the ceaseless clatter of the loom,

And ceaselessly deft maiden-fingers weave

The fine-wrought web; and I from morn till eve

Work with the rest, and when folk speak to me

I smile hard smiles; while still continually

The silly stream of maiden speech flows on:–

And now at length they talk of him that’s gone,

Lightly lamenting that he died so soon–

Ah me! ere yet his life’s sun stood at noon.

Some praise his eyes, some deem his body fair,

And some mislike the colour of his hair!

Sweet life, sweet shape, sweet eyes, and sweetest hair,

What form, what hue, save Love’s own, did ye wear?

I may not weep, not weep, for very shame.

He loved me not. One summer’s eve he came

To these our halls, my father’s honoured guest,

And seeing me, saw not. If his lips had prest

My lips, but once, in love; his eyes had sent

One love-glance into mine, I had been content,

And deemed it great joy for one little life;

Nor envied other maids the crown of wife:

The long sure years, the merry children-band–

Alas, alas, I never touched his hand!

And now my love is dead that loved not me.

Thrice-blest, thrice-crowned, of gods thrice-lovèd she–

That other, fairer maid, who tombward brings

Her gold, shorn locks and piled-up offerings

Of fragrant fruits, rich wines, and spices rare,

And cakes with honey sweet, with saffron fair;

And who, unchecked by any thought of shame,

May weep her tears, and call upon his name,

With burning bosom prest to the cold ground,

Knowing, indeed, that all her life is crown’d,

Thrice-crowned, thrice honoured, with that love of his;–

No dearer crown on earth is there, I wis.

While yet the sweet life lived, more light to bear

Was my heart’s hunger; when the morn was fair,

And I with other maidens in a line

Passed singing through the city to the shrine,

Oft in the streets or crowded market-place

I caught swift glimpses of the dear-known face;

Or marked a stalwart shoulder in the throng;

Or heard stray speeches as we passed along,

In tones more dear to me than any song.

These, hoarded up with care, and kept apart,

Did serve as meat and drink my hungry heart.

And now for ever has my sweet love gone;

And weary, empty days I must drag on,

Till all the days of all my life be sped,

By no thought cheered, by no hope comforted.

For if indeed we meet among the shades,

How shall he know me from the other maids?–

Me, that had died to save his body pain!

Alas, alas, such idle thoughts are vain!

O cruel, cruel sunlight, get thee gone!

O dear, dim shades of eve, come swiftly on!

That when quick lips, keen eyes, are closed in sleep,

Through the long night till dawn I then may weep.

Amy Levy poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Amy Levy, Archive K-L, Levy, Amy

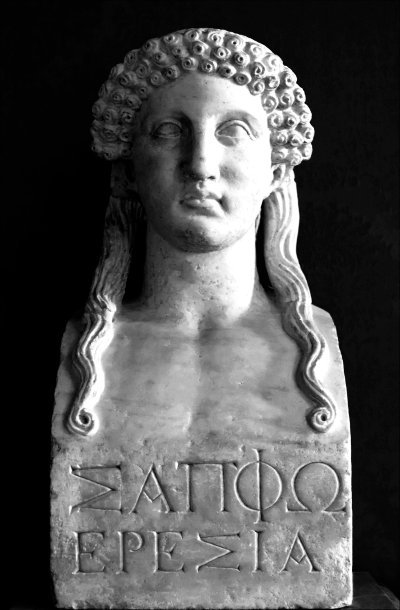

Sappho

(c. 630–570 b.c.)

Sleep, darling

Sleep, darling

I have a small

daughter called

Cleis, who is

like a golden

flower

I wouldn’t

take all Croesus’

kingdom with love

thrown in, for her

—

Don’t ask me what to wear

I have no embroidered

headband from Sardis to

give you, Cleis, such as

I wore

and my mother

always said that in her

day a purple ribbon

looped in the hair was thought

to be high style indeed

but we were dark:

a girl

whose hair is yellower than

torchlight should wear no

headdress but fresh flowers

Sappho

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

.jpg)

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sappho

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

Lucy’s Song

How beautiful at eventide

To see the twilight shadows pale,

Steal o’er the landscape, far and wide,

O’er stream and meadow, mound and dale!

How soft is Nature’s calm repose

When ev’ning skies their cool dews weep:

The gentlest wind more gently blows,

As if to soothe her in her sleep!

The gay morn breaks,

Mists roll away,

All Nature awakes

To glorious day.

In my breast alone

Dark shadows remain;

The peace it has known

It can never regain.

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

The Man Who Loved His Kind

Trotting through Deans Yard that afternoon, Prickett Ellis ran straight into Richard Dalloway, or rather, just as they were passing, the covert side glance which each was casting on the other, under his hat, over his shoulder, broadened and burst into recognition; they had not met for twenty years. They had been at school together. And what was Ellis doing? The Bar? Of course, of course—he had followed the case in the papers. But it was impossible to talk here. Wouldn’t he drop in that evening. (They lived in the same old place—just round the corner). One or two people were coming. Joynson perhaps. “An awful swell now,” said Richard.

“Good—till this evening then,” said Richard, and went his way, “jolly glad” (that was quite true) to have met that queer chap, who hadn’t changed one bit since he had been at school—just the same knobbly, chubby little boy then, with prejudices sticking out all over him, but uncommonly brilliant—won the Newcastle. Well—off he went.

Prickett Ellis, however, as he turned and looked at Dalloway disappearing, wished now he had not met him or, at least, for he had always liked him personally, hadn’t promised to come to this party. Dalloway was married, gave parties; wasn’t his sort at all. He would have to dress. However, as the evening drew on, he supposed, as he had said that, and didn’t want to be rude, he must go there.

But what an appalling entertainment! There was Joynson; they had nothing to say to each other. He had been a pompous little boy; he had grown rather more self–important—that was all; there wasn’t a single other soul in the room that Prickett Ellis knew. Not one. So, as he could not go at once, without saying a word to Dalloway, who seemed altogether taken up with his duties, bustling about in a white waistcoat, there he had to stand. It was the sort of thing that made his gorge rise. Think of grown up, responsible men and women doing this every night of their lives! The lines deepened on his blue and red shaven cheeks as he leant against the wall in complete silence, for though he worked like a horse, he kept himself fit by exercise; and he looked hard and fierce, as if his moustaches were dipped in frost. He bristled; he grated. His meagre dress clothes made him look unkempt, insignificant, angular.

Idle, chattering, overdressed, without an idea in their heads, these fine ladies and gentlemen went on talking and laughing; and Prickett Ellis watched them and compared them with the Brunners who, when they won their case against Fenners’ Brewery and got two hundred pounds compensation (it was not half what they should have got) went and spent five of it on a clock for him. That was a decent sort of thing to do; that was the sort of thing that moved one, and he glared more severely than ever at these people, overdressed, cynical, prosperous, and compared what he felt now with what he felt at eleven o’clock that morning when old Brunner and Mrs. Brunner, in their best clothes, awfully respectable and clean looking old people, had called in to give him that small token, as the old man put it, standing perfectly upright to make his speech, of gratitude and respect for the very able way in which you conducted our case, and Mrs. Brunner piped up, how it was all due to him they felt. And they deeply appreciated his generosity—because, of course, he hadn’t taken a fee.

And as he took the clock and put it on the middle of his mantelpiece, he had felt that he wished nobody to see his face. That was what he worked for—that was his reward; and he looked at the people who were actually before his eyes as if they danced over that scene in his chambers and were exposed by it, and as it faded—the Brunners faded—there remained as if left of that scene, himself, confronting this hostile population, a perfectly plain, unsophisticated man, a man of the people (he straightened himself) very badly dressed, glaring, with not an air or a grace about him, a man who was an ill hand at concealing his feelings, a plain man, an ordinary human being, pitted against the evil, the corruption, the heartlessness of society. But he would not go on staring. Now he put on his spectacles and examined the pictures. He read the titles on a line of books; for the most part poetry. He would have liked well enough to read some of his old favourites again—Shakespeare, Dickens—he wished he ever had time to turn into the National Gallery, but he couldn’t—no, one could not. Really one could not—with the world in the state it was in. Not when people all day long wanted your help, fairly clamoured for help. This wasn’t an age for luxuries. And he looked at the arm chairs and the paper knives and the well bound books, and shook his head, knowing that he would never have the time, never he was glad to think have the heart, to afford himself such luxuries. The people here would be shocked if they knew what he paid for his tobacco; how he had borrowed his clothes. His one and only extravagance was his little yacht on the Norfolk Broads. And that he did allow himself, He did like once a year to get right away from everybody and lie on his back in a field. He thought how shocked they would bethese fine folk—if they realized the amount of pleasure he got from what he was. old fashioned enough to call the love of nature; trees and fields he had known ever since he was a boy.

These fine people would be shocked. Indeed, standing there, putting his spectacles away in his pocket, he felt himself grow more and more shocking every instant. And it was a very disagreeable feeling. He did not feel this—that he loved humanity, that he paid only fivepence an ounce for tobacco and loved nature—naturally and quietly. Each of these pleasures had been turned into a protest. He felt that these people whom he despised made him stand and deliver and justify himself. “I am an ordinary man,” he kept saying. And what he said next he was really ashamed of saying, but he said it. “I have done more for my kind in one day than the rest of you in all your lives.” Indeed, he could not help himself; he kept recalling scene after scene, like that when the Brunners gave him the clockhe kept reminding himself of the nice things people had said of his humanity, of his generosity, how he had helped them. He kept seeing himself as the wise and tolerant servant of humanity. And he wished he could repeat his praises aloud. It was unpleasant that the sense of his goodness should boil within him. It was still more unpleasant that he could tell no one what people had said about him. Thank the Lord, he kept saying, I shall be back at work to–morrow; and yet he was no longer satisfied simply to slip through the door and go home. He must stay, he must stay until he had justified himself. But how could he? In all that room full of people, he did not know a soul to speak to.

At last Richard Dalloway came up.

“I want to introduce Miss O’Keefe,” he said. Miss O’Keefe looked him full in the eyes. She was a rather arrogant, abrupt mannered woman in the thirties.

Miss O’Keefe wanted an ice or something to drink. And the reason why she asked Prickett Ellis to give it her in what he felt a haughty, unjustifiable manner, was that she had seen a woman and two children, very poor, very tired, pressing against the railings of a square, peering in, that hot afternoon. Can’t they be let in? she had thought, her pity rising like a wave; her indignation boiling. No; she rebuked herself the next moment, roughly, as if she boxed her own ears. The whole force of the world can’t do it. So she picked up the tennis ball and hurled it back. The whole force of the world can’t do it, she said in a fury, and that was why she said so commandingly, to the unknown man:

“Give me an ice.”

Long before she had eaten it, Prickett Ellis, standing beside her without taking anything, told her that he had not been to a party for fifteen years; told her that his dress suit was lent him by his brother–in–law; told her that he did not like this sort of thing, and it would have eased him greatly to go on to say that he was a plain man, who happened to have a liking for ordinary people, and then would have told her (and been ashamed of it afterwards) about the Brunners and the clock, but she said:

“Have you seen the Tempest?” then (for he had not seen the Tempest), had he read some book? Again no, and then, putting her ice down, did he never read poetry?

And Prickett Ellis feeling something rise within him which would decapitate this young woman, make a victim of her, massacre her, made her sit down there, where they would not be interrupted, on two chairs, in the empty garden, for everyone was upstairs, only you could hear a buzz and a hum and a chatter and a jingle, like the mad accompaniment of some phantom orchestra to a cat or two slinking across the grass, and the wavering of leaves, and the yellow and red fruit like Chinese lanterns wobbling this way and that—the talk seemed like a frantic skeleton dance music set to something very real, and full of suffering.

“How beautiful!” said Miss O’Keefe.

Oh, it was beautiful, this little patch of grass, with the towers of Westminster massed round it black, high in the air, after the drawing–room; it was silent, after that noise. After all, they had that—the tired woman, the children.

Prickett Ellis lit a pipe. That would shock her; he filled it with shag tobacco—fivepence halfpenny an ounce. He thought how he would lie in his boat smoking, he could see himself, alone, at night, smoking under the stars. For always to–night he kept thinking how he would look if these people here were to see him. He said to Miss O’Keefe, striking a match on the sole of his boot, that he couldn’t see anything particularly beautiful out here.

“Perhaps,” said Miss O’Keefe, “you don’t care for beauty.” (He had told her that he had not seen the Tempest; that he had not read a book; he looked ill–kempt, all moustache, chin, and silver watch chain.) She thought nobody need pay a penny for this; the Museums are free and the National Gallery; and the country. Of course she knew the objections—the washing, cooking, children; but the root of things, what they were all afraid of saying, was that happiness is dirt cheap. You can have it for nothing. Beauty.

Then Prickett Ellis let her have it—this pale, abrupt, arrogant woman. He told her, puffing his shag tobacco, what he had done that day. Up at six; interviews; smelling a drain in a filthy slum; then to court.

Here he hesitated, wishing to tell her something of his own doings. Suppressing that, he was all the more caustic. He said it made him sick to hear well fed, well dressed women (she twitched her lips, for she was thin, and her dress not up to standard) talk of beauty.

“Beauty!” he said. He was afraid he did not understand beauty apart from human beings.

So they glared into the empty garden where the lights were swaying, and one cat hesitating in the middle, its paw lifted.

Beauty apart from human beings? What did he mean by that? she demanded suddenly.

Well this: getting more and more wrought up, he told her the story of the Brunners and the clock, not concealing his pride in it. That was beautiful, he said.

She had no words to specify the horror his story roused in her. First his conceit; then his indecency in talking about human feelings; it was a blasphemy; no one in the whole world ought to tell a story to prove that they had loved their kind. Yet as he told it—how the old man had stood up and made his speech—tears came into her eyes; ah, if any one had ever said that to her! but then again, she felt how it was just this that condemned humanity for ever; never would they reach beyond affecting scenes with clocks; Brunners making speeches to Prickett Ellises, and the Prickett Ellises would always say how they had loved their kind; they would always be lazy, compromising, and afraid of beauty. Hence sprang revolutions; from laziness and fear and this love of affecting scenes. Still this man got pleasure from his Brunners; and she was condemned to suffer for ever and ever from her poor poor women shut out from squares. So they sat silent. Both were very unhappy. For Prickett Ellis was not in the least solaced by what he had said; instead of picking her thorn out he had rubbed it in; his happiness of the morning had been ruined. Miss O’Keefe was muddled and annoyed; she was muddy instead of clear.

“I am afraid I am one of those very ordinary people,” he said, getting up, “who love their kind.”

Upon which Miss O’Keefe almost shouted: “So do L”

Hating each other, hating the whole houseful of people who had given them this painful, this disillusioning evening, these two lovers of their kind got up, and without a word, parted for ever.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: A Haunted House, and other short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

jef van kempen photos

stairs, 2009

►source: Museum of lost concepts

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: FDM Art Gallery, Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Museum of Lost Concepts, MUSEUM OF LOST CONCEPTS - invisible poetry, conceptual writing, spurensicherung

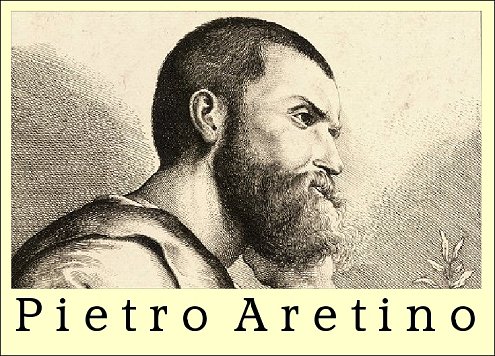

Ed Schilders

Pietro Aretino

De geschiedenis van een reputatie

Een

‘Men weet dat de vader van Aretino een zekere Luca was, een schoenmaker, wiens naam ons onbekend is gebleven: de schrijver koos de naam van zijn geboortestad.’

Dat schrijft de Moderne encyclopedie der wereldliteratuur en de redacteur bedoelt ermee te zeggen dat Aretino een bastaard was, net als Leonardo da Vinci en de Borgia’s. Hoe modern deze encyclopedie verder ook wil zijn, de schrijver van het lemma ‘Aretino’ meent niettemin dat het werk van de Italiaan ‘op zedelijk gebied ernstig voorbehoud verdient’ (inclusief het Prose Sacrai), en dat is waarschijnlijk de reden waarom Aretino’s bekendste en beste werk, de dialogen onder de titel Ragionamenti (1536), niet besproken wordt en dat de lezer er niet eens de titel terug zal vinden van zijn meest geruchtmakende produktie. Over het laatste alleen dit: ‘Zijn lichtzinnig gedrag en de obscene sonnetten, die hij bij de tekeningen van Giulio Romano voegde, dwongen hem (uit Rome) te vluchten.’ Bedoeld worden de Sonetti Lussuriosi, de Wulpse sonnetten zoals Ernst van Altena vertaalde voor de eerste Nederlandstalige druk in 1981, zestien staartsonnetten, geschreven bij evenveel tekeningen van seksuele houdingen door Giulio Romano, Raffaèls leerling die door Shakespeare (in Winter’s Tale) the rare Italian genoemd werd; de tekeningen die door Marcantonio Raimondi gegraveerd werden. Sonnetten en prenten vormen samen het eerste expliciet seksuele – en alleen daarom obsceen genoemde – voorlichtingsboek uit de moderne Europese zedengeschiedenis.

Aretino moet door schoenmaker Luca in 1491 verwekt zijn, want hij werd op 19 april 1492 in Arezzo geboren. Zijn levenswandel, die het midden hield tussen bourgondisch en decadent, heeft hem doen kennen als een van de markantste figuren uit de Italiaanse renaissance. En zoals hij leefde stierf hij, zegt men: hij kreeg een welhaast onstuitbare lachbui toen iemand hem tijdens een banket een schandaleus verhaal over zijn – Aretino’s – zuster vertelde, rolde van de lach uit zijn zetel en brak zijn nek. Het is 1557 en de plaats heet Venetië. ‘De Gesel der Prinsen’, zoals Ariosto hem noemde, was dood, maar zijn reputatie heeft de val groots overleefd, mede dankzij de zestien beroemdste obscene sonnetten aller tijden.

Ik heb in de tweede helft van het onderstaande een verzameling gegevens geordend die niet zozeer direct op die Wulpse sonnetten betrekking heeft, als wel op de legendarische reputatie die Aretino er ook postuum aan overhield. Complete boeken werden aan hem toegeschreven of onder zijn naam gepubliceerd, zowel pornografen als literatoren en zedenhistorici refereerden — met opgestoken vinger of cum summa laude — aan ‘zijn’ sedici modi of aan ‘Aretino’s standen’. De naam Aretino is eeuwenlang een handelsmerk geweest, en ‘een Aretino’ – die je kon maken of waarin je je kon gooien — werd niet minder dan een eufemisme voor iedere vorm van wellustig uitgeoefende versmelting en ook voor ieder prent-annex-tekstboek waarin de theorie fraai geïllustreerd tot de lezer kwam (voor niet-katholieken bevat de laatste zin, ik ben me dat bewust, wellicht een pleonasme). Om deze vorm van voortdurende Aretino-minachting en -verheerlijking goed te kunnen begrijpen is het noodzakelijk eerst in het kort Aretino’s reputatie bij zijn leven – ‘zijn lichtzinnig gedrag’ – te beschrijven en enige informatie te geven over de inhoud en de geschiedenis van ‘de obscene sonnetten die hij bij de tekeningen van Giulio Romano voegde.’

Aretino’s moeder was Tita, en Tita was prostituée en model voor kunstenaars. Als Aretino dertien jaar oud is berooft hij haar en vlucht hij naar Perugia waar hij leert boekbinden en schilderen. ‘Ik ging niet langer school,’ schrijft hij in een van zijn brieven, ‘dan om er een kruisteken te leren maken.’ Zes jaar later besluit hij naar Rome te vertrekken om aldaar zijn fortuin te zoeken. Ondanks goede connecties met de bankier Agostino Chigi en kardinaal Di San Giovanni lukt het hem niet tot in de hoogste kringen door te dringen: het hof van de paus, Julius II. Hij verlaat de stad, zwerft door Lombardi je en treedt tijdelijk toe tot de orde der kapucijnen. Pas als in 1513 Leo X tot paus is gekozen en het Vaticaan in een cultureel centrum veranderd wordt, keert hij terug naar de Eeuwige Stad. Hij wordt Leo’s kamenier en de paus blijkt zeer ontvankelijk voor zijn talenten als satiricus en humorist en als schrijver van de zo genaamde paskwillen en vleiende sonnetten. Aretino’s reputatie groeit voorbeeldig en het moet gezegd worden dat hij niets heeft nagelaten om zijn faam te bevorderen. Portretten van tijdgenoten en latere biografische stukken maken uitbundig gebruik van typeringen als ‘vleier, intrigant, afperser, roddelaar, chanteur en hielenlikker’, en het lijkt waar dat hij dat alles inderdaad geweest is teneinde zijn macht, aanzien en invloed te vergroten en daarmee zijn welstand. Wat zulke kwalificaties zo aardig maakt is de wetenschap dat hij zich deze haat enkel en alleen met de pen en zijn tong wist te verwerven. Wie Aretino aan zijn zijde vond kon verzekerd zijn van zeer effectieve public relations; zijn tegenstanders vreesden zijn intriges en roddel-geschriften die vaak anoniem werden verspreid maar waarvan iedere sociaal-cultureel bewuste Romein de herkomst kende.

In 1521 sterft Leo X, zijn voornaamste beschermheer, en Aretino lijkt, met vele anderen, de situatie verkeerd te hebben ingeschat. In Rome rekent men op de verkiezing tot paus van Giulio de’ Medici en Aretino heeft zich reeds voor Leo’s dood verzekerd van een eervolle plaats binnen diens vriendenkring. Zeven dukaten tegen honderd worden er in de stad ingezet op de verkiezing van Giulio maar ondanks deze goklustige opiniepeilingen en ondanks de paskwillen die Aretino bijna dagelijks tegen de tegenstanders schrijft, wordt op 9 januari 1522 onze landgenoot, de kardinaal van Tortosa, de nieuwe Papa. Het interregnum is echter van korte duur: Hadrianus VI bestuurt de moederkerk slechts één jaar en na de verkiezing van Giulio de’ Medici tot paus Clemens VII is voor Aretino de weg naar de top opnieuw vrij.

Aretino’s eerste gedichten werden in 1512 in Venetië gepubliceerd. Hoezeer hij vanaf die tijd zijn pen uitsluitend benut heeft voor persoonlijke en politieke doeleinden mag blijken uit het gegeven dat volgende publikaties, voornamelijk satirische blijspelen, pas vanaf 1533 plaatsvinden. Tussen 1512 en 1533 publiceerde hij uitsluitend de Sonetti Lussuriosi, voor het overige was hij, zoals Wayland Young hem getypeerd heeft, een gevreesd columnist en geducht politiek commentator. Wanneer de sonnetten geschreven zijn is lang duister gebleven maar vooral dankzij gedetailleerde onderzoekingen aan het eind van de vorige eeuw, onder andere door de uitgever Isidore Liseux, kan nu met zekerheid gesteld worden dat Romano zijn zestien standen in 1524 tekende en liet graveren, en dat Aretino er één jaar later zijn verzen aan toevoegde. Pas in 1527 vond deze gecombineerde inspanning zijn weg naar een breder publiek via deeerste officiële editie, gedrukt te Venetië. ‘(1) Vasari schrijft over het project het volgende: ‘Aangezien sommige van de prenten werden aangetroffen op plaatsen waar men zehet minst zou verwachten, werden ze niet alleen verboden maar werd Marcantonio gearresteerd en in het gevang geworpen.’ Een aantal schrijvers neemt aan dat deze censuuraffaire heeft plaatsgevonden naar aanleiding van de druk uit 1527, maar dit lijkt onjuist.

Al eerder moet de produktie van de prenten zowel de edele delen van de voorstanders als de adrenergische zenuwcellen van de tegenstanders in beroering hebben gebracht. Aretino zelf schrijft in een brief (1538) waarin hij op de gebeurtenissen terugkijkt: ‘Nadat ik paus Clemens had overgehaald Marcantonio Bolognese vrij te laten, hij zat in de gevangenis omdat hij de sedici modi had gegraveerd, gevoelde ik de lust de platen te zien (. . .) en toen ik ze gezien had voelde ik dezelfde aandrift welke Giulio Romano ertoe had aangezet om ze te maken. En aangezien dichters en beeldhouwers, zowel de klassieke als de moderne, van tijd tot tijd als jeux d’esprits bepaalde dingen geschreven of gebeiteld hebben (zoals de marmeren satyr in het Palazzo Chigi die een jongen probeert te verkrachten), heb ik de sonnetten neergepend die je aan de voet van ieder blad kunt zien.’

Een en ander impliceert dat het schandaal zich moet hebben afgespeeld naar aanleiding van de eerste, waarschijnlijk voor privéplezier bestemde produkties, die nog zonder Aretino’s bijdrage verschenen. Niettemin schrijft Francesco de Sanctis in zijn History of Italian Literature: ‘Hij moest uit Rome vluchten vanwege zijn zestien sonnetten, die verlucht werden door obscene tekeningen van Giulio Romano.’ Dat had zo in de Moderne encyclopedie gekund, maar of het juist is mag betwijfeld worden, al is het zeker niet onwaarschijnlijk dat Aretino met zijn geschreven bijdrage te ver ging.

De oorzaak van Aretino’s plotselinge vertrek uit Rome wordt, denk ik, beter weergegeven door Casimir von Chledowski (Die Menschen der Renaissance). Hij verbindt de vlucht met een vete die gegroeid was tussen Aretino en kardinaal Giberti, die uit woede om Aretino’s intriges en anonieme spotschriften in de nacht van 28 juli 1525 een aanslag op de dichter liet plegen waarbij Aretino gewond raakte. Merkwaardig genoeg noemt Aretino in zijn al geciteerde brief deze Giberti ook als de aanstichter van de hetze tegen Romano en Raimondi.

In welke orde van oorzaak en gevolg deze schermutselingen zich ook precies verhouden, het mag duidelijk zijn dat Aretino in Rome gevaarlijke vijanden gemaakt had en dat zijn betrokkenheid bij het standenrepertorium zijn crediet niet bevorderd heeft. Als paus Clemens weigert om zijn zijde te kiezen in het conflict met Giberti verlaat Aretino de stad en nu definitief.

Aretino’s verdere levensdagen, voornamelijk in Venetië doorgebracht, zijn hoogst boeiend maar voor het hier te volgen onderwerp in hun details niet van belang. Ik zal volstaan met enige gegevens die duidelijk maken dat zijn vlucht uit Rome hem geenszins benadeeld heeft en dat hij zijn levenslustige doelstellingen in later jaren alleen maar grootser verwezenlijkt heeft.

Na Rome brengt hij een jaar door in het kamp van Giovanni de’Medici, de leider van de bande nere, en leerde hij de voornaamste handlangers van de condottiere kennen.

Als Giovanni in zijn armen gestorven is reist hij naar Venetië waar men hem met open armen ontvangt. Hij woont er in een luxueus palazzo op kosten van zijn rijke vrienden en met het geld van de pensioenen die zijn adellijke en Vaticaanse werkgevers hem hebben toegestaan voor verrichte schrijf- en roddeldiensten. In de jaren 1530 verschijnt het grootste deel van zijn werk in druk, de komedies, de Ragionamenti, maar ook enige heiligenlevens.

In een van zijn brieven meldt hij trots dat men alom munten slaat met zijn afbeelding, dat hij op gevels prijkt en dat er kristallen vazen zijn die ‘Aretino’s’ genoemd worden en vrouwen, zijn ex-kamermeisjes, die erop staan met dezelfde naam te worden aangeduid.

Onder zijn vrienden vinden we in de loop der jaren Titiaan, die hem ‘de condottiere van de literatuur’ noemde en zijn portret schilderde, Tintoretto en Vasari, literatoren als Ariosto, Tasso en Varchi, de historicus Giovio. Frans I, de piraat Barbarossa en de sultan Suleiman zonden hem geschenken, Julius III benoemde hem tot ridder in de orde van Sint Petrus. Hij was erelid van de academies van Florence, Siena en Padua.

(wordt vervolgd)

Ed Schilders: Pietro Aretino. De geschiedenis van een reputatie (1)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Aretino, Pietro, Ed Schilders, Erotic literature

13e editie van

Boeken rond het Paleis Tilburg

op zondag 29 augustus 2010 van 10-17 uur

Literaire werken, kookboeken, biografieën, kinderboeken, geschiedenisboeken, thrillers, romans, gespecialiseerde boeken… noem het en het is te vinden in een van de 300 kramen rond het Paleis van Koning Willem II. Een locatie die goed past bij de grootste boekenmarkt van Zuid-Nederland

Zowel officiële boekverkopers als particulieren bieden hier hun boeken aan. En dat maakt de Tilburgse boekenmarkt zo speciaal. Boeken rond het Paleis wordt dit jaar voor de dertiende keer georganiseerd door Stichting Dr PJ Cools en is een kwalitatieve aanvulling op het literaire aanbod in Tilburg en omgeving. De laatste zondag van augustus is tevens koopzondag. U kunt dus ook nog gezellig winkelen in het centrum van Tilburg.

Het programma

12.00 uur Opening van het programma

12.15 uur Voordracht Ted van Lieshout in Paleis Raadhuis

13.30 uur Voordracht Ted van Lieshout in Bibliotheek Tilburg Centrum

13.30 uur Optreden Nop Maas in Paleis Raadhuis

Ted van Lieshout is schrijver van boeken als ‘Koekjes!’ en ‘Hou van mij’ (hier won hij in 2010 een Zilveren Griffel mee). De toegang is gratis en het wordt een programma voor jong en oud. Nop Maas is o.a. biograaf van Gerard Reve.

Tijdens de13de editie van deze jaarlijkse boekenmarkt op het Willemsplein en in de straten rondom het stadhuis, vindt traditiegetrouw ook de verkoop van afgeschreven materialen in Bibliotheek Tilburg Centrum plaats. Dit gebeurt tijdens een volledige openstelling van de bibliotheek van 10.00 tot 17.00 uur. Brabantse bibliotheekleden worden getrakteerd op de actie 3 halen = 2 betalen.

De toegang is op alle onderdelen gratis.

► Organisatie: Stichting Dr PJ Cools Tilburg

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: - Book Lovers

.jpg)

Nachrichten aus Berlin: Reflections 2

Photos Anton K. – Berlin 2010

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, FDM in Berlin, Nachrichten aus Berlin

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

44

If the dull substance of my flesh were thought,

Injurious distance should not stop my way,

For then despite of space I would be brought,

From limits far remote, where thou dost stay,

No matter then although my foot did stand

Upon the farthest earth removed from thee,

For nimble thought can jump both sea and land,

As soon as think the place where he would be.

But ah, thought kills me that I am not thought

To leap large lengths of miles when thou art gone,

But that so much of earth and water wrought,

I must attend, time’s leisure with my moan.

Receiving nought by elements so slow,

But heavy tears, badges of either’s woe.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature