Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Pulitzer Prizes

Pulitzer Prizes

Pulitzer Prize administrator Mike Pride has announced today (april 10) the winners of the 2017 Pulitzer Prizes in the World Room at Columbia University in New York, N.Y.

This announcement marks the 101st year of the prizes. The Pulitzer Prizes have been awarded by Columbia University each spring since 1917.

The awards are chosen by a board of jurors for Journalism, Letters, Music and Drama.

The 2017 Winners in Letters, Drama and Music:

Fiction

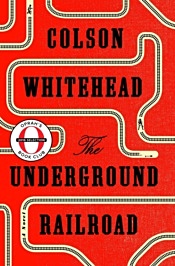

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

From prize-winning, bestselling author Colson Whitehead, a magnificent tour de force chronicling a young slave’s adventures as she makes a desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South.

Poetry

Poetry

Olio by Tyehimba Jess

Part fact, part fiction, Tyehimba Jess’s much anticipated second book weaves sonnet, song, and narrative to examine the lives of mostly unrecorded African American performers, musicians and artists directly before and after the Civil War up to World War I. Olio is an effort to understand how they met, resisted, complicated, co-opted, and sometimes defeated attempts to minstrelize them.

History

Blood in the Water: The Atica Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson

On September 9, 1971, nearly 1,300 prisoners took over the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York to protest years of mistreatment. Drawing from more than a decade of extensive research, historian Heather Ann Thompson sheds new light on every aspect of the uprising and its legacy, giving voice to all those who took part in this forty-five-year fight for justice.

Nonfiction

Nonfiction

Evicted by Matthew Desmond

Staff Pick: In this brilliant, heartbreaking book, Matthew Desmond takes us into the poorest neighborhoods of Milwaukee to tell the story of eight families on the edge.

Biography or Autobiography

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar

The Return is at once an exquisite meditation on history, politics, and art, a brilliant portrait of a nation and a people on the cusp of change, and a disquieting depiction of the brutal legacy of absolute power. Above all, it is a universal tale of loss and love and of one family’s life.

List of all this years Pulitzer Prize winners:

Journalism

Public Service: The staff of the New York Daily News and ProPublica.

Breaking News Reporting: The staff of East Bay Times.

Investigative Reporting: Eric Eyre, the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

Explanatory Reporting: The Panama Papers, by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, McClatchy and the Miami Herald.

Local Reporting: The staff of The Salt Lake Tribune.

National Reporting: David Fahrenthold, The Washington Post.

International Reporting: The staff of The New York Times.

Feature Writing: C.J. Chivers of The New York Times.

Commentary: Peggy Noonan, The Wall Street Journal.

Criticism: Hilton Als, The New Yorker.

Editorial Writing: Art Cullen, The Storm Lake Times.

Editorial Cartooning: Jim Morin, Miami Herald.

Breaking News Photography: Daniel Berehulak, The New York Times.

Feature Photography: E. Jason Wambsgans, Chicago Tribune.

Letters, Drama, & Music

Fiction: The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead.

Drama: Sweat, by Lynn Nottage.

History: Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy, by Heather Ann Thompson.

Biography or Autobiography: The Return, by Hisham Matar.

Poetry: Olio, by Tyehimba Jess.

General Nonfiction: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, by Matthew Desmond.

Music: Angel’s Bone, by Du Yun.

# more information on website pulitzer

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Awards & Prizes, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Illustrators, Illustration, MONTAIGNE, MUSIC, Photography, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, The Art of Reading, THEATRE

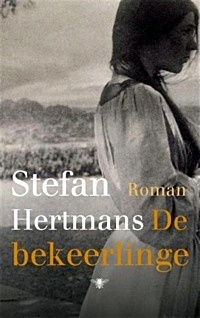

De E. du Perronprijs 2016 is toegekend aan Stefan Hertmans voor zijn roman De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij) vanwege de kracht om tegenstrijdigheden met elkaar te verbinden en de kunst om in alles het gelijke op te zoeken. De andere genomineerden waren Rodaan Al Galidi met Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas) en Carolijn Visser met Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus).

De E. du Perronprijs 2016 is toegekend aan Stefan Hertmans voor zijn roman De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij) vanwege de kracht om tegenstrijdigheden met elkaar te verbinden en de kunst om in alles het gelijke op te zoeken. De andere genomineerden waren Rodaan Al Galidi met Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas) en Carolijn Visser met Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus).

De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van €2500 euro en een textiel object, ontworpen door studio ‘by aaaa’ (Moyra Besjes en Natasja Lauwers) en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum in Tilburg.

De uitreiking vindt plaats op donderdag 13 april, aanvang 20.00 uur bij brabants kenniscentrum voor kunst en cultuur (bkkc), Spoorlaan 21 te Tilburg.

Voorafgaand aan de uitreiking houdt schrijver Arnon Grunberg de E. du Perronlezing met als titel ‘Het paradijs’.

De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum voor kunst en cultuur (bkkc). In 2015 won Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer de prijs voor zijn dichtbundel Idyllen (2015), zijn pamflet Asielzoekers en zijn columns in NRC Next. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Warna Oosterbaan en Theo Baart (2015), Mohammed Benzakour (2013), Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009), Adriaan van Dis (2008) en Guus Kuijer (2007).

# meer info op website tilburg university

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Abdelkader Benali, Art & Literature News, Eddy du Perron, Hertmans, Stefan, Literary Events

Op woensdag 5 april verschijnt het eerste nummer van 2017 van ‘Tilburg. Tijdschrift voor geschiedenis, monumenten en cultuur’ met daarin uitgebreid aandacht voor Antony Kok, Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondriaan en De Stijl.

Jef van Kempen en Hanneke van Kempen schrijven een ‘Geschiedenis van een biografie’ over hun op handen zijnde biografie van Antony Kok. Zij doen verslag van 35 jaar onderzoek naar het leven van Antony Kok, de dichter en spoorwegbeambte uit Tilburg die aan het begin van de Eerste Wereldoorlog vriendschap sloot met de Amsterdamse schrijver en schilder Theo van Doesburg. De omvangrijke briefwisseling tussen Van Doesburg en Kok is een van de belangrijkste bronnen met betrekking tot de geschiedenis van de beweging rond het tijdschrift De Stijl, dat een grote invloed had op de Nederlandse en internationale kunst.

Petra Robben gaat in haar artikel ‘Mijmering over een Mondriaan in Tilburg’ in op de Internationale Tentoonstelling van Nijverheid, Handel en Kunst in 1913. Niko de Wit vertelt over ‘Den Does’, een uitkijktoren voor Tilburg en een hommage aan Theo van Doesburg.

Losse nummers van Tijdschrift Tilburg zijn verkrijgbaar in de Tilburgse boekhandels Gianotten-Mutsaers en Livius de Zevensprong in Tilburg en bij boekhandel Buitelaar in Goirle.

‘Tilburg. Tijdschrift voor geschiedenis, monumenten en cultuur’ verschijnt drie keer per jaar en kost € 5,50

DE STIJL in Tilburg: voorpublicatie biografie Antony Kok

# Zie ook: website tijdschrift Tilburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, Constuctivisme, Dada, Dadaïsme, De Stijl, Doesburg, Theo van, Essays about Van Doesburg, Kok, Mondriaan, Schwitters, Milius & Van Moorsel, Hanneke van Kempen, Jef van Kempen, Kok, Antony, Kurt Schwitters, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Schwitters, Kurt, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg

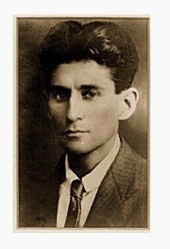

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka

Eine alltägliche Verwirrung

Ein alltäglicher Vorfall: sein Ertragen eine alltägliche Verwirrung. A hat mit B aus H ein wichtiges Geschäft abzuschließen. Er geht zur Vorbesprechung nach H, legt den Hin- und Herweg in je zehn Minuten zurück und rühmt sich zu Hause dieser besonderen Schnelligkeit. Am nächsten Tag geht er wieder nach H, diesmal zum endgültigen Geschäftsabschluß. Da dieser voraussichtlich mehrere Stunden erfordern wird, geht A sehr früh morgens fort. Obwohl aber alle Nebenumstände, wenigstens nach A’s Meinung, völlig die gleichen sind wie im Vortag, braucht er diesmal zum Weg nach H zehn Stunden. Als er dort ermüdet abends ankommt, sagt man ihm, daß B, ärgerlich wegen A’s Ausbleiben, vor einer halben Stunden zu A in sein Dorf gegangen sei und sie sich eigentlich unterwegs hätten treffen müssen. Man rät A zu warten. A aber, in Angst wegen des Geschäftes, macht sich sofort auf und eilt nach Hause.

Diesmal legt er den Weg, ohne besonders darauf zu achten, geradezu in einem Augenblick zurück. Zu Hause erfährt er, B sei doch schon gleich früh gekommen – gleich nach dem Weggang A’s; ja, er habe A im Haustor getroffen, ihn an das Geschäft erinnert, aber A habe gesagt, er hätte jetzt keine Zeit, er müsse jetzt eilig fort.

Trotz diesem unverständlichen Verhalten A’s sei aber B doch hier geblieben, um auf A zu warten. Er habe zwar schon oft gefragt, ob A nicht schon wieder zurück sei, befinde sich aber noch oben in A’s Zimmer. Glücklich darüber, B jetzt noch zu sprechen und ihm alles erklären zu können, läuft A die Treppe hinauf. Schon ist er fast oben, da stolpert er, erleidet eine Sehnenzerrung und fast ohnmächtig vor Schmerz, unfähig sogar zu schreien, nur winselnd im Dunkel hört er, wie B – undeutlich ob in großer Ferne oder knapp neben ihm – wütend die Treppe hinunterstampft und endgültig verschwindet.

Franz Kafka

(1883-1924)

Eine alltägliche Verwirrung

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

DADALENIN reconstructs and speculates about how Dada and Lenin had more in common than is usually assumed. The book points to some of the tragicomic aspects of their parallel and overlapping artistic and political histories in order to question the unfulfilled legacy of the avant-garde. In Rainer Ganahl’s voluminous series of works DADA and Lenin are abundant sources of historical imagination. To dive into the historical situation Ganahl uses a variety of artistic media and techniques–ranging from animation movies to theatre performances, from ink drawings to bronze sculptures, departing from a number of historical details and catch phrases, from the no-man’s land between porn, terror and the history of the avant-gardes.

DADALENIN reconstructs and speculates about how Dada and Lenin had more in common than is usually assumed. The book points to some of the tragicomic aspects of their parallel and overlapping artistic and political histories in order to question the unfulfilled legacy of the avant-garde. In Rainer Ganahl’s voluminous series of works DADA and Lenin are abundant sources of historical imagination. To dive into the historical situation Ganahl uses a variety of artistic media and techniques–ranging from animation movies to theatre performances, from ink drawings to bronze sculptures, departing from a number of historical details and catch phrases, from the no-man’s land between porn, terror and the history of the avant-gardes.

Dadalenin

Rainer Ganahl

Publisher Taube

ISBN 9783981451849

608 p,

ills in colour & bw,

15 x 23 cm, hb, English

€25.00

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Dada, DADA, Dadaïsme

Shortlist Libris Literatuur Prijs 2017

Shortlist Libris Literatuur Prijs 2017

De schrijvers Walter van den Berg, Alfred Birney, Arnon Grunberg, Jeroen Olyslaegers, Marja Pruis en Lize Spit maken nog kans op het winnen van de prestigieuze Libris Literatuur Prijs en de bijbehorende 50.000 euro.

De vakjury, die naast Janine van den Ende (medeoprichter en bestuurslid VandenEnde Foundation) bestaat uit Kees ’t Hart, Michel Krielaars, Anna Luyten en Marrigje Paijmans, zal op 8 mei a.s. bekend maken welke van deze zes romans zij als de beste van het afgelopen jaar beschouwt. Nieuwsuur zendt die avond live een reportage uit van de prijsuitreiking in het Amstel Hotel te Amsterdam. Vorig jaar won Connie Palmen de prijs met Jij zegt het.

De zes genomineerde auteurs ontvingen elk 2.500 euro.

Schuld

Schuld

Walter van den Berg

Welkom in het universum van Walter van den Berg: de harde wereld van Amsterdam Nieuw-West. Waar mannen hangen in snackbars, rijden in Nissan Sunny’s en lopen op badslippers – en hun vrouw slaan. De pientere Kevin maakt gejatte laptops schoon en verkoopbaar. Vieze filmpjes die hij hierbij vindt zet hij online en de vreemdgangers belt hij op. Om ze te laten zien dat het hun schuld is. Om maar met iemand te kunnen praten. Maar dan komt zijn vader, ex-charmezanger ‘Zingende Ron’, uit de bak. Sommige schulden worden nooit afgelost.

De tolk van Java

De tolk van Java

Alfred Birney

Voor een Helmondse schoenmakersdochter, een Indische voormalige oorlogstolk en hun zoon – de verteller – bestaat er geen heden. Er is alleen een belast verleden: de jeugd van de moeder tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog in Brabant; de jeugd van de vader, die na de oorlog van Oost-Java naar Nederland vlucht; en de jeugd van de verteller die, geterroriseerd door zijn paranoïde vader, zijn tienerjaren op een internaat doorbrengt. Jarenlang zal hij zijn ouders achtervolgen met vragen over de oorlog, die ook hij als een zware last met zich meedraagt. Hun verhalen zijn spannend, hilarisch, gruwelijk, treurig en rauw. Hun onderlinge verhouding is afwijkend: ze zijn eerder tot elkaar veroordeeld dan dat ze een liefhebbende band hebben, met de herinnering als hun gezamenlijke vijand.

Moedervlekken

Moedervlekken

Arnon Grunberg

Otto Kadoke werkt als psychiater in een crisiscentrum: zijn specialiteit is suicide-preventie, hij dient mensen met een doodswens voor het leven te behouden. Wanneer hij op een dag bij zijn oude en hulpbehoevende moeder op bezoek gaat, doet een van de Nepalese verzorgsters de deur open, gehuld in slechts een handdoek. De psychiater, die zich altijd aan het protocol houdt, wordt overmand door gevoelens van liefde voor het meisje, met als gevolg dat hij de verzorging voor zijn moeder voortaan alleen dient te organiseren.

Kadoke is kinderloos, van middelbare leeftijd, maar niet onaantrekkelijk voor artsen in opleiding: hij heeft er menig weten te verleiden. Na opnieuw een grensoverschrijdende ontmoeting, ditmaal met een suïcidale jonge vrouw, lopen het professionele en privéleven van Kadoke definitief in het honderd: zijn moeders huis wordt een ambulant crisiscentrum.

Moedervlekken is een genadeloos eerlijke roman over de liefde van een zoon voor zijn moeder en vader, en vice versa. Een boek over twee mensen die niet kunnen leven – en niet dood kunnen gaan – zonder elkaar. Het markeert een nieuwe fase in Arnon Grunberg’s veelomvattende schrijverschap: zorg en liefde sluiten elkaar niet langer uit. Ondanks verlies en pijn blijkt het mogelijk liefde voor het leven te voelen.

Wil

Wil

Jeroen Olyslaegers

Het is oorlog. Antwerpen wordt bezet door geweld en wantrouwen. Wilfried Wils acht zichzelf een dichter in wording, maar moet tegelijk zien te overleven als hulpagent. De mooie Yvette wordt verliefd op hem en haar broer Lode is een waaghals die zijn nek uitsteekt voor joden. Wilfrieds artistieke mentor, Nijdig Baardje, wil juist alle joden vernietigen. Onbehaaglijk laverend tussen twee werelden, probeert Wilfried te overleven terwijl de jacht op de joden onverminderd verdergaat. Jaren later vertelt hij zijn verhaal aan een van zijn nakomelingen. Een ambitieuze, veelzijdige roman die de lezer niet los zal laten. Olyslaegers bewees zijn meesterschap al eerder, maar met WIL zal hij menigeen volstrekt verrassen.

Zachte riten

Zachte riten

Marja Pruis

‘Lucas zwemt voor me uit, met zijn korte krachtige slag. Hij zweeft op een vaste afstand in mijn geheugen, waarom kan ik hem niet inhalen, terwijl ik denk dat ik almaar harder zwem?’ Guusje Bouhuys, poëziedocente, huisvriendin, zus, heeft haar leven op de rem gezet. Als haar beste vriend wordt beschuldigd van plagiaat en een dierbare collega doodziek blijkt, beseft ze dat ze haar zorgvuldig geconserveerde universum zal moeten verlaten. In een absorberende stijl, ironisch en bitterzoet, schrijft Marja Pruis over het verlangen trouw te blijven aan de mensen die met je meelopen, ook als ze er niet meer zijn. Kun je een ander redden, behoeden voor de val? Kun je jezelf bewaren als in een gedicht? Zachte riten gaat over de conflictsituaties van de menselijke ziel, de betekenis van poëzie en de plaats van liefde in ons leven. Marja Pruis schreef onder meer de veelgeprezen romans De vertrouweling en Atoomgeheimen en het biografische portret Als je weg bent. Over Patricia de Martelaere, dat vijf drukken behaalde. Ze is gerenommeerd criticus en columniste voor De Groene Amsterdammer. Haar essaybundel Kus me, straf me. Over lezen en schrijven, liefde en verraad werd genomineerd voor de AKO Literatuurprijs en won de Jan Hanlo Essayprijs.

Het smelt

Het smelt

Lize Spit

1988 is een bijzonder jaar voor het kleine, Vlaamse Bovenmeer: behalve Eva worden er slechts twee andere kinderen geboren, Pim en Laurens. De drie maken er hun hele jeugd samen het beste van. Tot de bloedhete zomer van 2002; de jongens worden pubers met snode plannen. De verlegen Eva kan meedoen of oprotten. Die keuze is geen keuze.

De Libris Literatuur Prijs wordt toegekend voor de beste oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalige roman. Met de prijs is een geldbedrag van in totaal 65.000 euro gemoeid (2.500 euro voor de zes genomineerde auteurs en 50.000 euro voor de winnaar). De prijs is gemodelleerd naar de Britse Booker Prize. Dat houdt in dat er een longlist wordt gemaakt, gevolgd door zes nominaties, waarna tot slot de prijswinnaar wordt bekend gemaakt tijdens het traditionele galadiner in het Amstel Hotel te Amsterdam. De voorzitter komt uit een maatschappelijke sector buiten de literatuur. De overige vier leden zijn werkzaam als literatuurwetenschapper, criticus en/of auteur.

# Meer informatie op website Libris Literatuur Prijs

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Arnon Grunberg, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, FICTION & NONFICTION ARCHIVE, Literary Events

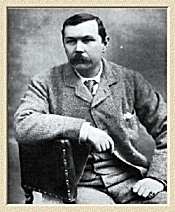

The Doctors of Hoyland

The Doctors of Hoyland

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Dr. James Ripley was always looked upon as an exceedingly lucky dog by all of the profession who knew him. His father had preceded him in a practice in the village of Hoyland, in the north of Hampshire, and all was ready for him on the very first day that the law allowed him to put his name at the foot of a prescription. In a few years the old gentleman retired, and settled on the South Coast, leaving his son in undisputed possession of the whole country side. Save for Dr. Horton, near Basingstoke, the young surgeon had a clear run of six miles in every direction, and took his fifteen hundred pounds a year, though, as is usual in country practices, the stable swallowed up most of what the consulting-room earned.

Dr. James Ripley was two-and-thirty years of age, reserved, learned, unmarried, with set, rather stern features, and a thinning of the dark hair upon the top of his head, which was worth quite a hundred a year to him. He was particularly happy in his management of ladies. He had caught the tone of bland sternness and decisive suavity which dominates without offending. Ladies, however, were not equally happy in their management of him. Professionally, he was always at their service. Socially, he was a drop of quicksilver. In vain the country mammas spread out their simple lures in front of him. Dances and picnics were not to his taste, and he preferred during his scanty leisure to shut himself up in his study, and to bury himself in Virchow’s Archives and the professional journals.

Study was a passion with him, and he would have none of the rust which often gathers round a country practitioner. It was his ambition to keep his knowledge as fresh and bright as at the moment when he had stepped out of the examination hall. He prided himself on being able at a moment’s notice to rattle off the seven ramifications of some obscure artery, or to give the exact percentage of any physiological compound. After a long day’s work he would sit up half the night performing iridectomies and extractions upon the sheep’s eyes sent in by the village butcher, to the horror of his housekeeper, who had to remove the debris next morning. His love for his work was the one fanaticism which found a place in his dry, precise nature.

It was the more to his credit that he should keep up to date in his knowledge, since he had no competition to force him to exertion. In the seven years during which he had practised in Hoyland three rivals had pitted themselves against him, two in the village itself and one in the neighbouring hamlet of Lower Hoyland. Of these one had sickened and wasted, being, as it was said, himself the only patient whom he had treated during his eighteen months of ruralising. A second had bought a fourth share of a Basingstoke practice, and had departed honourably, while a third had vanished one September night, leaving a gutted house and an unpaid drug bill behind him. Since then the district had become a monopoly, and no one had dared to measure himself against the established fame of the Hoyland doctor.

It was, then, with a feeling of some surprise and considerable curiosity that on driving through Lower Hoyland one morning he perceived that the new house at the end of the village was occupied, and that a virgin brass plate glistened upon the swinging gate which faced the high road. He pulled up his fifty guinea chestnut mare and took a good look at it. “Verrinder Smith, M. D.,” was printed across it in very neat, small lettering. The last man had had letters half a foot long, with a lamp like a fire-station. Dr. James Ripley noted the difference, and deduced from it that the new-comer might possibly prove a more formidable opponent. He was convinced of it that evening when he came to consult the current medical directory. By it he learned that Dr. Verrinder Smith was the holder of superb degrees, that he had studied with distinction at Edinburgh, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna, and finally that he had been awarded a gold medal and the Lee Hopkins scholarship for original research, in recognition of an exhaustive inquiry into the functions of the anterior spinal nerve roots. Dr. Ripley passed his fingers through his thin hair in bewilderment as he read his rival’s record. What on earth could so brilliant a man mean by putting up his plate in a little Hampshire hamlet.

But Dr. Ripley furnished himself with an explanation to the riddle. No doubt Dr. Verrinder Smith had simply come down there in order to pursue some scientific research in peace and quiet. The plate was up as an address rather than as an invitation to patients. Of course, that must be the true explanation. In that case the presence of this brilliant neighbour would be a splendid thing for his own studies. He had often longed for some kindred mind, some steel on which he might strike his flint. Chance had brought it to him, and he rejoiced exceedingly.

And this joy it was which led him to take a step which was quite at variance with his usual habits. It is the custom for a new-comer among medical men to call first upon the older, and the etiquette upon the subject is strict. Dr. Ripley was pedantically exact on such points, and yet he deliberately drove over next day and called upon Dr. Verrinder Smith. Such a waiving of ceremony was, he felt, a gracious act upon his part, and a fit prelude to the intimate relations which he hoped to establish with his neighbour.

The house was neat and well appointed, and Dr. Ripley was shown by a smart maid into a dapper little consulting room. As he passed in he noticed two or three parasols and a lady’s sun bonnet hanging in the hall. It was a pity that his colleague should be a married man. It would put them upon a different footing, and interfere with those long evenings of high scientific talk which he had pictured to himself. On the other hand, there was much in the consulting room to please him. Elaborate instruments, seen more often in hospitals than in the houses of private practitioners, were scattered about. A sphygmograph stood upon the table and a gasometer-like engine, which was new to Dr. Ripley, in the corner. A book-case full of ponderous volumes in French and German, paper-covered for the most part, and varying in tint from the shell to the yoke of a duck’s egg, caught his wandering eyes, and he was deeply absorbed in their titles when the door opened suddenly behind him. Turning round, he found himself facing a little woman, whose plain, palish face was remarkable only for a pair of shrewd, humorous eyes of a blue which had two shades too much green in it. She held a pince-nez in her left hand, and the doctor’s card in her right.

“How do you do, Dr. Ripley?” said she.

“How do you do, madam?” returned the visitor. “Your husband is perhaps out?”

“I am not married,” said she simply.

“Oh, I beg your pardon! I meant the doctor—Dr. Verrinder Smith.”

“I am Dr. Verrinder Smith.”

Dr. Ripley was so surprised that he dropped his hat and forgot to pick it up again.

“What!” he grasped, “the Lee Hopkins prizeman! You!”

He had never seen a woman doctor before, and his whole conservative soul rose up in revolt at the idea. He could not recall any Biblical injunction that the man should remain ever the doctor and the woman the nurse, and yet he felt as if a blasphemy had been committed. His face betrayed his feelings only too clearly.

“I am sorry to disappoint you,” said the lady drily.

“You certainly have surprised me,” he answered, picking up his hat.

“You are not among our champions, then?”

“I cannot say that the movement has my approval.”

“And why?”

“I should much prefer not to discuss it.”

“But I am sure you will answer a lady’s question.”

“Ladies are in danger of losing their privileges when they usurp the place of the other sex. They cannot claim both.”

“Why should a woman not earn her bread by her brains?”

Dr. Ripley felt irritated by the quiet manner in which the lady cross-questioned him.

“I should much prefer not to be led into a discussion, Miss Smith.”

“Dr. Smith,” she interrupted.

“Well, Dr. Smith! But if you insist upon an answer, I must say that I do not think medicine a suitable profession for women and that I have a personal objection to masculine ladies.”

It was an exceedingly rude speech, and he was ashamed of it the instant after he had made it. The lady, however, simply raised her eyebrows and smiled.

“It seems to me that you are begging the question,” said she. “Of course, if it makes women masculine that WOULD be a considerable deterioration.”

It was a neat little counter, and Dr. Ripley, like a pinked fencer, bowed his acknowledgment.

“I must go,” said he.

“I am sorry that we cannot come to some more friendly conclusion since we are to be neighbours,” she remarked.

He bowed again, and took a step towards the door.

“It was a singular coincidence,” she continued, “that at the instant that you called I was reading your paper on ‘Locomotor Ataxia,’ in the Lancet.”

“Indeed,” said he drily.

“I thought it was a very able monograph.”

“You are very good.”

“But the views which you attribute to Professor Pitres, of Bordeaux, have been repudiated by him.”

“I have his pamphlet of 1890,” said Dr. Ripley angrily.

“Here is his pamphlet of 1891.” She picked it from among a litter of periodicals. “If you have time to glance your eye down this passage——”

Dr. Ripley took it from her and shot rapidly through the paragraph which she indicated. There was no denying that it completely knocked the bottom out of his own article. He threw it down, and with another frigid bow he made for the door. As he took the reins from the groom he glanced round and saw that the lady was standing at her window, and it seemed to him that she was laughing heartily.

All day the memory of this interview haunted him. He felt that he had come very badly out of it. She had showed herself to be his superior on his own pet subject. She had been courteous while he had been rude, self-possessed when he had been angry. And then, above all, there was her presence, her monstrous intrusion to rankle in his mind. A woman doctor had been an abstract thing before, repugnant but distant. Now she was there in actual practice, with a brass plate up just like his own, competing for the same patients. Not that he feared competition, but he objected to this lowering of his ideal of womanhood. She could not be more than thirty, and had a bright, mobile face, too. He thought of her humorous eyes, and of her strong, well-turned chin. It revolted him the more to recall the details of her education. A man, of course, could come through such an ordeal with all his purity, but it was nothing short of shameless in a woman.

But it was not long before he learned that even her competition was a thing to be feared. The novelty of her presence had brought a few curious invalids into her consulting rooms, and, once there, they had been so impressed by the firmness of her manner and by the singular, new-fashioned instruments with which she tapped, and peered, and sounded, that it formed the core of their conversation for weeks afterwards. And soon there were tangible proofs of her powers upon the country side. Farmer Eyton, whose callous ulcer had been quietly spreading over his shin for years back under a gentle regime of zinc ointment, was painted round with blistering fluid, and found, after three blasphemous nights, that his sore was stimulated into healing. Mrs. Crowder, who had always regarded the birthmark upon her second daughter Eliza as a sign of the indignation of the Creator at a third helping of raspberry tart which she had partaken of during a critical period, learned that, with the help of two galvanic needles, the mischief was not irreparable. In a month Dr. Verrinder Smith was known, and in two she was famous.

Occasionally, Dr. Ripley met her as he drove upon his rounds. She had started a high dogcart, taking the reins herself, with a little tiger behind. When they met he invariably raised his hat with punctilious politeness, but the grim severity of his face showed how formal was the courtesy. In fact, his dislike was rapidly deepening into absolute detestation. “The unsexed woman,” was the description of her which he permitted himself to give to those of his patients who still remained staunch. But, indeed, they were a rapidly-decreasing body, and every day his pride was galled by the news of some fresh defection. The lady had somehow impressed the country folk with almost superstitious belief in her power, and from far and near they flocked to her consulting room.

Occasionally, Dr. Ripley met her as he drove upon his rounds. She had started a high dogcart, taking the reins herself, with a little tiger behind. When they met he invariably raised his hat with punctilious politeness, but the grim severity of his face showed how formal was the courtesy. In fact, his dislike was rapidly deepening into absolute detestation. “The unsexed woman,” was the description of her which he permitted himself to give to those of his patients who still remained staunch. But, indeed, they were a rapidly-decreasing body, and every day his pride was galled by the news of some fresh defection. The lady had somehow impressed the country folk with almost superstitious belief in her power, and from far and near they flocked to her consulting room.

But what galled him most of all was, when she did something which he had pronounced to be impracticable. For all his knowledge he lacked nerve as an operator, and usually sent his worst cases up to London. The lady, however, had no weakness of the sort, and took everything that came in her way. It was agony to him to hear that she was about to straighten little Alec Turner’s club foot, and right at the fringe of the rumour came a note from his mother, the rector’s wife, asking him if he would be so good as to act as chloroformist. It would be inhumanity to refuse, as there was no other who could take the place, but it was gall and wormwood to his sensitive nature. Yet, in spite of his vexation, he could not but admire the dexterity with which the thing was done. She handled the little wax-like foot so gently, and held the tiny tenotomy knife as an artist holds his pencil. One straight insertion, one snick of a tendon, and it was all over without a stain upon the white towel which lay beneath. He had never seen anything more masterly, and he had the honesty to say so, though her skill increased his dislike of her. The operation spread her fame still further at his expense, and self-preservation was added to his other grounds for detesting her. And this very detestation it was which brought matters to a curious climax.

One winter’s night, just as he was rising from his lonely dinner, a groom came riding down from Squire Faircastle’s, the richest man in the district, to say that his daughter had scalded her hand, and that medical help was needed on the instant. The coachman had ridden for the lady doctor, for it mattered nothing to the Squire who came as long as it were speedily. Dr. Ripley rushed from his surgery with the determination that she should not effect an entrance into this stronghold of his if hard driving on his part could prevent it. He did not even wait to light his lamps, but sprang into his gig and flew off as fast as hoof could rattle. He lived rather nearer to the Squire’s than she did, and was convinced that he could get there well before her.

And so he would but for that whimsical element of chance, which will for ever muddle up the affairs of this world and dumbfound the prophets. Whether it came from the want of his lights, or from his mind being full of the thoughts of his rival, he allowed too little by half a foot in taking the sharp turn upon the Basingstoke road. The empty trap and the frightened horse clattered away into the darkness, while the Squire’s groom crawled out of the ditch into which he had been shot. He struck a match, looked down at his groaning companion, and then, after the fashion of rough, strong men when they see what they have not seen before, he was very sick.

The doctor raised himself a little on his elbow in the glint of the match. He caught a glimpse of something white and sharp bristling through his trouser leg half way down the shin.

“Compound!” he groaned. “A three months’ job,” and fainted.

When he came to himself the groom was gone, for he had scudded off to the Squire’s house for help, but a small page was holding a gig-lamp in front of his injured leg, and a woman, with an open case of polished instruments gleaming in the yellow light, was deftly slitting up his trouser with a crooked pair of scissors.

“It’s all right, doctor,” said she soothingly. “I am so sorry about it. You can have Dr. Horton to-morrow, but I am sure you will allow me to help you to-night. I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw you by the roadside.”

“The groom has gone for help,” groaned the sufferer.

“When it comes we can move you into the gig. A little more light, John! So! Ah, dear, dear, we shall have laceration unless we reduce this before we move you. Allow me to give you a whiff of chloroform, and I have no doubt that I can secure it sufficiently to——”

Dr. Ripley never heard the end of that sentence. He tried to raise a hand and to murmur something in protest, but a sweet smell was in his nostrils, and a sense of rich peace and lethargy stole over his jangled nerves. Down he sank, through clear, cool water, ever down and down into the green shadows beneath, gently, without effort, while the pleasant chiming of a great belfry rose and fell in his ears. Then he rose again, up and up, and ever up, with a terrible tightness about his temples, until at last he shot out of those green shadows and was in the light once more. Two bright, shining, golden spots gleamed before his dazed eyes. He blinked and blinked before he could give a name to them. They were only the two brass balls at the end posts of his bed, and he was lying in his own little room, with a head like a cannon ball, and a leg like an iron bar. Turning his eyes, he saw the calm face of Dr. Verrinder Smith looking down at him.

“Ah, at last!” said she. “I kept you under all the way home, for I knew how painful the jolting would be. It is in good position now with a strong side splint. I have ordered a morphia draught for you. Shall I tell your groom to ride for Dr. Horton in the morning?”

“I should prefer that you should continue the case,” said Dr. Ripley feebly, and then, with a half hysterical laugh,—“You have all the rest of the parish as patients, you know, so you may as well make the thing complete by having me also.”

It was not a very gracious speech, but it was a look of pity and not of anger which shone in her eyes as she turned away from his bedside.

Dr. Ripley had a brother, William, who was assistant surgeon at a London hospital, and who was down in Hampshire within a few hours of his hearing of the accident. He raised his brows when he heard the details.

“What! You are pestered with one of those!” he cried.

“I don’t know what I should have done without her.”

“I’ve no doubt she’s an excellent nurse.”

“She knows her work as well as you or I.”

“Speak for yourself, James,” said the London man with a sniff. “But apart from that, you know that the principle of the thing is all wrong.”

“You think there is nothing to be said on the other side?”

“Good heavens! do you?”

“Well, I don’t know. It struck me during the night that we may have been a little narrow in our views.”

“Nonsense, James. It’s all very fine for women to win prizes in the lecture room, but you know as well as I do that they are no use in an emergency. Now I warrant that this woman was all nerves when she was setting your leg. That reminds me that I had better just take a look at it and see that it is all right.”

“I would rather that you did not undo it,” said the patient. “I have her assurance that it is all right.”

Brother William was deeply shocked.

“Of course, if a woman’s assurance is of more value than the opinion of the assistant surgeon of a London hospital, there is nothing more to be said,” he remarked.

“I should prefer that you did not touch it,” said the patient firmly, and Dr. William went back to London that evening in a huff.

The lady, who had heard of his coming, was much surprised on learning his departure.

“We had a difference upon a point of professional etiquette,” said Dr. James, and it was all the explanation he would vouchsafe.

For two long months Dr. Ripley was brought in contact with his rival every day, and he learned many things which he had not known before. She was a charming companion, as well as a most assiduous doctor. Her short presence during the long, weary day was like a flower in a sand waste. What interested him was precisely what interested her, and she could meet him at every point upon equal terms. And yet under all her learning and her firmness ran a sweet, womanly nature, peeping out in her talk, shining in her greenish eyes, showing itself in a thousand subtle ways which the dullest of men could read. And he, though a bit of a prig and a pedant, was by no means dull, and had honesty enough to confess when he was in the wrong.

“I don’t know how to apologise to you,” he said in his shame-faced fashion one day, when he had progressed so far as to be able to sit in an arm-chair with his leg upon another one; “I feel that I have been quite in the wrong.”

“Why, then?”

“Over this woman question. I used to think that a woman must inevitably lose something of her charm if she took up such studies.”

“Oh, you don’t think they are necessarily unsexed, then?” she cried, with a mischievous smile.

“Please don’t recall my idiotic expression.”

“I feel so pleased that I should have helped in changing your views. I think that it is the most sincere compliment that I have ever had paid me.”

“At any rate, it is the truth,” said he, and was happy all night at the remembrance of the flush of pleasure which made her pale face look quite comely for the instant.

For, indeed, he was already far past the stage when he would acknowledge her as the equal of any other woman. Already he could not disguise from himself that she had become the one woman. Her dainty skill, her gentle touch, her sweet presence, the community of their tastes, had all united to hopelessly upset his previous opinions. It was a dark day for him now when his convalescence allowed her to miss a visit, and darker still that other one which he saw approaching when all occasion for her visits would be at an end. It came round at last, however, and he felt that his whole life’s fortune would hang upon the issue of that final interview. He was a direct man by nature, so he laid his hand upon hers as it felt for his pulse, and he asked her if she would be his wife.

“What, and unite the practices?” said she.

He started in pain and anger.

“Surely you do not attribute any such base motive to me!” he cried. “I love you as unselfishly as ever a woman was loved.”

“No, I was wrong. It was a foolish speech,” said she, moving her chair a little back, and tapping her stethoscope upon her knee. “Forget that I ever said it. I am so sorry to cause you any disappointment, and I appreciate most highly the honour which you do me, but what you ask is quite impossible.”

With another woman he might have urged the point, but his instincts told him that it was quite useless with this one. Her tone of voice was conclusive. He said nothing, but leaned back in his chair a stricken man.

“I am so sorry,” she said again. “If I had known what was passing in your mind I should have told you earlier that I intended to devote my life entirely to science. There are many women with a capacity for marriage, but few with a taste for biology. I will remain true to my own line, then. I came down here while waiting for an opening in the Paris Physiological Laboratory. I have just heard that there is a vacancy for me there, and so you will be troubled no more by my intrusion upon your practice. I have done you an injustice just as you did me one. I thought you narrow and pedantic, with no good quality. I have learned during your illness to appreciate you better, and the recollection of our friendship will always be a very pleasant one to me.”

And so it came about that in a very few weeks there was only one doctor in Hoyland. But folks noticed that the one had aged many years in a few months, that a weary sadness lurked always in the depths of his blue eyes, and that he was less concerned than ever with the eligible young ladies whom chance, or their careful country mammas, placed in his way.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Doctors of Hoyland (#14)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Boekenweekgeschenk van Herman Koch

Cadeau van uw boekhandel bij besteding van € 12,50 aan Nederlandstalige boeken

Synopsis Makkelijk leven

Tom Sanders is een gevierd schrijver van zelfhulpboeken en hij leidt een gelukkig leven met Julia en twee volwassen zonen, van wie de jongste, Stefan, zijn oogappel is. Tijdens een verjaardagsfeestje voor Julia staat hun schoondochter Hanna – op wie Tom en Julia niet dol zijn – opeens voor de deur. Snikkend vertelt ze dat ze door Stefan is geslagen en dat dat niet de eerste keer is. Moet Tom zijn lievelingszoon Stefan aanspreken op zijn gedrag? Of loont het misschien meer om de adviezen uit zijn zelfhulpboeken in praktijk te brengen, zoals zijn bekende richtlijn ‘Probeer problemen niet altijd op te lossen door eraan te denken; vaak worden ze eerder opgelost door er niet aan te denken’?

Thema Verboden vruchten

De mens is genotzuchtig. Maar toegeven aan genot levert soms strijd op, met ons geweten, onze levensovertuiging, onze omgeving en onze fysieke dan wel geestelijke grenzen. Wel willen, niet mogen, toch doen: verboden vruchten, zowel in het leven als in de letteren. Wie kent ze niet: de drank- en drugsverslaafden in Meriswin (Hafid Bouazza), Hallo Muur (Erik Jan Harmens), Angst en walging in Las Vegas (Hunter S. Thomson) en  Naamloos (Pepijn Lanen), de gokkers in Alles of niets (Khalid Boudou), de seksjunks in De 120 dagen van Sodom (Marquis de Sade), Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd (Louis Paul Boon) en Lolita (Nabokov), de troosteters in Chocolat (Joanne Harris), de vreetzakken in de Romeinse klassieker Satyricon (passage Het feestmaal bij Trimalchio) en de kannabalist in De maagd Marino (Yves Petry). En natuurlijk de overspeligen zoals beschreven in De buitenvrouw (Joost Zwagerman), Godin, held (Gustaaf Peek), Komt een vrouw bij de dokter(Kluun) en Mélodie d’Amour (Margriet de Moor).

Naamloos (Pepijn Lanen), de gokkers in Alles of niets (Khalid Boudou), de seksjunks in De 120 dagen van Sodom (Marquis de Sade), Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd (Louis Paul Boon) en Lolita (Nabokov), de troosteters in Chocolat (Joanne Harris), de vreetzakken in de Romeinse klassieker Satyricon (passage Het feestmaal bij Trimalchio) en de kannabalist in De maagd Marino (Yves Petry). En natuurlijk de overspeligen zoals beschreven in De buitenvrouw (Joost Zwagerman), Godin, held (Gustaaf Peek), Komt een vrouw bij de dokter(Kluun) en Mélodie d’Amour (Margriet de Moor).

Boekenweekessay bij het thema Verboden vruchten

Voor maar € 3,50 in uw boekwinkel

Libris Literatuur Prijswinnares Connie Palmen (Prometheus) schreef het Boekenweekessay 2017 bij het thema van de Boekenweek 2017: Verboden vruchten. Titel: De zonde van de vrouw.

In de bibliotheek

De Boekenweek is het literaire hoogtepunt van het jaar. De Openbare Bibliotheken grijpen dit evenement jaarlijks aan om de mooiste boeken te presenteren die zij in huis hebben. Uiteraard heeft de bibliotheek ook veel boeken bij het thema van de Boekenweek 2017: Verboden vruchten. (lees op deze pagina meer over het thema).

Boekenweekmagazine: haal gratis bij de bibliotheek

BOEKENWEEK 2017 van 25 maart tot en met 2 april

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Bookstores, Boekenweek, FICTION & NONFICTION ARCHIVE, Illustrators, Illustration, Joost Zwagerman, Literary Events, Louis Paul Boon, Marquis de Sade

Genomineerden E. du Perronprijs 2016: Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser – Arnon Grunberg houdt bij de prijsuitreiking de E. du Perronlezing donderdagavond 13 april 2017 in Tilburg

Genomineerden E. du Perronprijs 2016: Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser – Arnon Grunberg houdt bij de prijsuitreiking de E. du Perronlezing donderdagavond 13 april 2017 in Tilburg

De schrijvers Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser zijn genomineerd voor de E. du Perronprijs 2016. De prijs wordt toegekend aan personen of instellingen die met een cultuuruiting in brede zin een bijdrage leveren aan een beter begrip van de multiculturele samenleving. De uitreiking vindt plaats op donderdagavond 13 april 2017 bij het brabants kenniscentrum kunst en cultuur (bkkc) in Tilburg. Dan houdt Arnon Grunberg de E. du Perronlezing met als titel ‘Het paradijs’.

Rodaan Al Galidi – Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas)

Rodaan Al Galidi – Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas)

Rodaan Al Galidi doet ons verslag van de leerschool die de Nederlandse asielprocedure is. Negen jaar wacht de hoofdpersoon Semmier Kariem op een beschikking in een van de vestigingen van het AZC. Negen jaar tussen aankomst in Nederland op de vlucht voor fysieke bedreiging en definitieve toelating wordt in dit verhaal invoelbaar als een oneindige mentale nekklem. Dat is het leergeld voor vluchtelingen die niet op uitnodiging de landsgrenzen passeren. Leerschool of wachtkamer, het talent van Rodaan Al Galidi is gerijpt. Deze vertellingen in de vorm van brieven aan een geïnteresseerde buitenstaander gericht laten ons alle kanten van hoop, lethargie, opstandigheid, beklag en ironie zien. De bewoners van het AZC leven op een mix van herinneringen, volharding, wanhoop; kortom overlevingsdrift. Het verslag is introspectief, zakelijk, ironisch en soms ronduit Kafkaësk. Met zijn stijl schraagt de verteller zijn bestaan en geeft hij vaart aan een eindeloos vertraagde tijd.

Stefan Hertmans – De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Stefan Hertmans – De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Bekering is een van de meest ingrijpende keuzes die een mens kan maken. Zij rukt het individu uit zijn vertrouwde verband dat bepaald wordt door afstamming en traditie. Toebehoren biedt vertrouwdheid en bescherming. Dit aanbod, deze burcht af te wijzen en te verlaten, te vluchten is een onomkeerbare daad. De bekeerling moet koersen op onbekende instrumenten: een nieuw geloof, een vreemde taal, een onbekend bestaan in een onbekend gebied. Stefan Hertmans voert ons mee in het historische verhaal van Vigdis Adelaïs, die uit liefde besluit een Joodse jongeman te volgen. Het is het einde van de 11e eeuw. Het sentiment van kruistochten hangt in de lucht. Een millennium later volgt Hertmans deze vlucht, fysiek door het landschap met gebruikmaking van bronnen en verbeelding. Verstoting, bedreiging en vlucht zijn van alle tijden. Hertmans is in staat om op heel persoonlijke manier het universele en bijzondere hiervan open te schrijven in een overtuigende roman.

Carolijn Visser – Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus)

Carolijn Visser – Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus)

De titel van deze documentaire vertelling herinnert ons onmiddellijk aan het literaire cliché dat niets zo onwaarschijnlijk is als het leven zelf. Selma, een Joodse overlevende van de Holocaust, besluit met haar Chinese echtgenoot mee te gaan naar China in de jaren vijftig. Wat haar te wachten staat is het lot van intellectuelen en buitenlanders in de periode van de Culturele Revolutie. Het is de verdienste van Carolijn Visser om het onbeschrijfelijke glashelder aan ons te presenteren. Dat doet ze door vaardig te beschrijven wat er aan informatie bewaard is gebleven, maar net zo goed door betekenisvolle leemtes achter te laten. Selma is twee keer slachtoffer geworden van etnische uitsluiting. Ze staat niet voor grotere gehelen, ze was een individu dat voortdurend onder bedreiging van grotere verbanden, ideologieën leefde en uiteindelijk ook vermalen werd. Selma is een monument voor het kwetsbare individu.

E. du Perronprijs

E. du Perronprijs

De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum kunst en cultuur (bkkc). De prijs is bedoeld voor personen of instellingen die, net als Du Perron in zijn tijd, grenzen signaleren en doorbreken die wederzijds begrip tussen verschillende bevolkingsgroepen in de weg staan. De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van €2500 euro en een textiel object, ontworpen door [NAAM] en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum. In 2015 won Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer de prijs voor zijn dichtbundel Idyllen, zijn pamflet Gelukszoekers en zijn columns in NRC Next. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Warna Oosterbaan & Theo Baart (2014), Mohammed Benzakour (2013), Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009) en Adriaan van Dis (2008).

# Meer informatie over de du Perronprijs op website Tilburg University

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Abdelkader Benali, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Eddy du Perron, Hertmans, Stefan, Literary Events

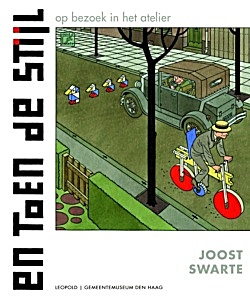

Nieuw kunstprentenboek over De Stijl door Joost Swarte

Nieuw kunstprentenboek over De Stijl door Joost Swarte

In 2017 is het honderd jaar geleden dat het tijdschrift De Stijl werd opgericht. Nederland viert dit met het feestjaar Mondriaan tot Dutch design. 100 jaar De Stijl. Met ’s werelds grootste Mondriaan-collectie – en tevens een van de grootste De Stijl-collecties – is het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag het middelpunt van dit feestelijke jaar. Op 11 februari trapt het museum dit jaar af met een tentoonstelling over de ontstaansgeschiedenis van een nieuwe kunst die de wereld voorgoed heeft veranderd. Bij Uitgeverij Leopold verschijnt op 11 februari het prentenboek dat Joost Swarte voor dit jubileumjaar maakte: En toen De Stijl.

Joost Swarte is Nederlands bekendste striptekenaar. Zijn werk is vertaald in het Engels, Frans, Spaans, Noors, Italiaans en Duits en zijn illustraties verschenen in toonaangevende magazines met The New Yorker als belangrijkste blikvanger. Naast striptekenaar is Swarte ook illustrator, architect en vormgever.

En toen De Stijl is een hommage aan de kunstenaars, architecten en ontwerpers die bij De Stijl betrokken waren of erdoor werden beïnvloed. Joost Swarte laat een kat een kijkje nemen in hun ateliers. Die zitten vol verwijzingen naar hun ontwikkeling: van de oprichting van De Stijl door Theo van Doesburg, tot de weg naar abstractie die Van der Leck doormaakte, de ultieme abstractie van Mondriaan, de meubels van Gerrit Rietveld, het door Rietveld geïnspireerde houten speelgoed van Ko Verzuu, tot het grafische werk en de bekende Bruynzeelkeuken van Piet Zwart. Een feest van ontdekking voor jong en oud. –

Joost Swarte:

En toen De Stijl.

Op bezoek in het atelier

Pagina’s 32

ISBN 978-90-258-7238-0

Prijs € 14,99

Uitg.Leopold

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Constructivism, Constuctivisme, De Stijl, Illustrators, Illustration, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg

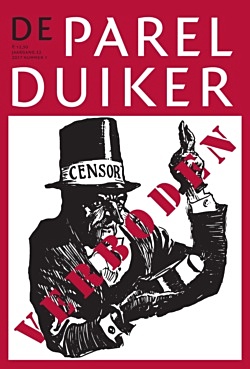

Boeken en kunstwerken kunnen om uiteenlopende redenen verboden vruchten worden. Wegens hun scabreuze karakter natuurlijk. Of om politiek ongewenste c.q. verwerpelijk geachte elementen.

Boeken en kunstwerken kunnen om uiteenlopende redenen verboden vruchten worden. Wegens hun scabreuze karakter natuurlijk. Of om politiek ongewenste c.q. verwerpelijk geachte elementen.

In de speciale Parelduiker zoomen we vier keer in op verboden boeken: de als pornografie bestempelde ‘realistische romans’ van Jan Brandts, de in beslag genomen realistische romans van Hugo Beersman, de als fascistisch gebrandmerkte kunstwerken van de Schotse kunstenaar Ian Hamilton Finlay en het toneelstuk Jan Pietersz. Coen van J. Slauerhoff.

Marco Entrop, Rendez-vous op ’t Tulpplein. Een verboden liefdesgeschiedenis

Nederland kon in de wederopbouw geen ondermijnende krachten gebruiken. Een steen des aanstoots was de pornografie. De schrijver Jan Brandts zag zich als een van de eersten geslachtofferd. Zijn in 1947 verschenen roman over de oprechte liefde tussen twee jonge mensen werd in beslag genomen, omdat ze het met elkaar deden.

Bert Sliggers, ‘Gretig gleden zijn handen over haar weelderige borsten’. De verboden realistische romans van Hugo Beersman

Hoewel er in 1914 al een Rijksbureau was dat de handel in ‘ontuchtige uitgaven’ moest tegengaan, duurde het nog tot 1930 voordat de rotte appels binnen de lectuur en literatuur grootscheeps werden opgespoord. Zo kon het gebeuren dat boeken die aan het begin van die eeuw zonder bemoeienis van de politie werden verhandeld en gelezen opeens in beslag werden genomen en de eigenaren bekeurd. Uitgever Jan Hilbingh Mulder, die een boekwinkel in de Amsterdamse Cornelis Schuytstraat dreef en boeken van Hugo Beersman uitgaf, werd door Justitie streng aangepakt.

Marco Daane, Osso? Oh, zo! Een Schotse tuinman, een Duits struikelblok en Franse houthakkers

Boeken en kunstwerken kunnen om uiteenlopende redenen verboden vruchten worden. Wegens hun scabreuze karakter natuurlijk – zie elders in dit nummer. Of om politiek ongewenste c.q. verwerpelijk geachte elementen, vooral antisemitische of nazistische. In de westerse cultuur komt dat eigenlijk niet eens zo vaak voor, maar is niet Hitlers eigen Mein Kampf formeel nog altijd verboden? Ook de Schotse kunstenaar Ian Hamilton Finlay ondervond in 1988 in Frankrijk hoe gevoelig dit thema is. Enkele Nederlanders en Vlamingen werden eveneens door de affaire beroerd.

Hein Aalders, Een ‘ploertig stuk’ en de openbare orde. De wereldpremière van Slauerhoffs Jan Pietersz. Coen

Uitvoeringen van Slauerhoffs toneelstuk Jan Pietersz. Coen (1931) stuitten keer op keer op bezwaren bij vooral burgemeesters, die opvoering ofwel verboden ofwel sterk ontrieden met een beroep op de openbare orde. Het stuk zou door zijn kritische kijk op de Hollandse koloniaal de Nederlandse politiek ten aanzien van Indonesië en Nieuw-Guinea kunnen verstoren. Uiteindelijk werd Slauerhoffs Jan Pietersz. Coen pas voor het eerst opgevoerd in 1961, door een Amsterdams studentengezelschap, maar slechts eenmalig en tijdens een besloten bijeenkomst.

Hans Olink, Berliner Beobachter: Theun de Vries in de DDR

Jan Paul Hinrichs, Schoon & haaks (over Joeri Olesja, Fritzi Harmsen van Beek, Frans Erens en J.M.A. Biesheuvel)

Paul Arnoldussen, De Laatste Pagina: Hubert van Herreweghen (1920-2016)

De Parelduiker is een uitgave van Uitgeverij Bas Lubberhuizen | Postbus 51140 | 1007 EC Amsterdam | T 020 618 41 32

Parelduikermiddag 25 maart in de Oba

De Parelduiker nodigt zijn abonnees, lezers en andere geïnteresseerden van harte uit voor een feestelijke Parelduikermiddag aan het begin van de Boekenweek, op zaterdag 25 maart van 16 tot 17.30 uur in de Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam (oba), Theater van het Woord, 7de etage (adres: Oosterdokskade 143, 1011 dl Amsterdam. Centraal staat: Jan Pietersz. Coen – een verboden toneelstuk van Slauerhoff

Vele malen werd een uitvoering van dit toneeldrama verboden. Pas in 1961 werd een eenmalige opvoering toegestaan. Spelers van toen vertellen erover. Scènes uit het gewraakte stuk worden gelezen en van commentaar voorzien.

M.m.v. Slauerhoff-biograaf Wim Hazeu, Hugo Koolschijn, Celia Nufaar, Ger Thijs, Krijn ter Braak, Paul Rutgers van der Loeff en Boudewijn Chabot. De middag wordt afgesloten door de dichteres Marieke Rijneveld (C. Buddingh’-prijs 2016), die voordraagt uit haar werk. Moderator: Anton de Goede.

De Parelduiker 2017/1

Themanummer: VERBODEN

# Meer informatie op website de parelduiker

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Boekenweek, Literary Events, LITERARY MAGAZINES, Magazines, Marco Entrop, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas

The Los Amigos Fiasco

The Los Amigos Fiasco

by Arthur Conan Doyle

I used to be the leading practitioner of Los Amigos. Of course, everyone has heard of the great electrical generating gear there. The town is wide spread, and there are dozens of little townlets and villages all round, which receive their supply from the same centre, so that the works are on a very large scale. The Los Amigos folk say that they are the largest upon earth, but then we claim that for everything in Los Amigos except the gaol and the death-rate. Those are said to be the smallest.

Now, with so fine an electrical supply, it seemed to be a sinful waste of hemp that the Los Amigos criminals should perish in the old-fashioned manner. And then came the news of the eleotrocutions in the East, and how the results had not after all been so instantaneous as had been hoped. The Western Engineers raised their eyebrows when they read of the puny shocks by which these men had perished, and they vowed in Los Amigos that when an irreclaimable came their way he should be dealt handsomely by, and have the run of all the big dynamos. There should be no reserve, said the engineers, but he should have all that they had got. And what the result of that would be none could predict, save that it must be absolutely blasting and deadly. Never before had a man been so charged with electricity as they would charge him. He was to be smitten by the essence of ten thunderbolts. Some prophesied combustion, and some disintegration and disappearance. They were waiting eagerly to settle the question by actual demonstration, and it was just at that moment that Duncan Warner came that way.

Warner had been wanted by the law, and by nobody else, for many years. Desperado, murderer, train robber and road agent, he was a man beyond the pale of human pity. He had deserved a dozen deaths, and the Los Amigos folk grudged him so gaudy a one as that. He seemed to feel himself to be unworthy of it, for he made two frenzied attempts at escape. He was a powerful, muscular man, with a lion head, tangled black locks, and a sweeping beard which covered his broad chest. When he was tried, there was no finer head in all the crowded court. It’s no new thing to find the best face looking from the dock. But his good looks could not balance his bad deeds. His advocate did all he knew, but the cards lay against him, and Duncan Warner was handed over to the mercy of the big Los Amigos dynamos.

I was there at the committee meeting when the matter was discussed. The town council had chosen four experts to look after the arrangements. Three of them were admirable. There was Joseph M’Conner, the very man who had designed the dynamos, and there was Joshua Westmacott, the chairman of the Los Amigos Electrical Supply Company, Limited. Then there was myself as the chief medical man, and lastly an old German of the name of Peter Stulpnagel. The Germans were a strong body at Los Amigos, and they all voted for their man. That was how he got on the committee. It was said that he had been a wonderful electrician at home, and he was eternally working with wires and insulators and Leyden jars; but, as he never seemed to get any further, or to have any results worth publishing he came at last to be regarded as a harmless crank, who had made science his hobby. We three practical men smiled when we heard that he had been elected as our colleague, and at the meeting we fixed it all up very nicely among ourselves without much thought of the old fellow who sat with his ears scooped forward in his hands, for he was a trifle hard of hearing, taking no more part in the proceedings than the gentlemen of the press who scribbled their notes on the back benches.

We did not take long to settle it all. In New York a strength of some two thousand volts had been used, and death had not been instantaneous. Evidently their shock had been too weak. Los Amigos should not fall into that error. The charge should be six times greater, and therefore, of course, it would be six times more effective. Nothing could possibly be more logical. The whole concentrated force of the great dynamos should be employed on Duncan Warner.

So we three settled it, and had already risen to break up the meeting, when our silent companion opened his month for the first time.

“Gentlemen,” said he, “you appear to me to show an extraordinary ignorance upon the subject of electricity. You have not mastered the first principles of its actions upon a human being.”

The committee was about to break into an angry reply to this brusque comment, but the chairman of the Electrical Company tapped his forehead to claim its indulgence for the crankiness of the speaker.

“Pray tell us, sir,” said he, with an ironical smile, “what is there in our conclusions with which you find fault?”

“With your assumption that a large dose of electricity will merely increase the effect of a small dose. Do you not think it possible that it might have an entirely different result? Do you know anything, by actual experiment, of the effect of such powerful shocks?”

“We know it by analogy,” said the chairman, pompously. “All drugs increase their effect when they increase their dose; for example—for example——”

“Whisky,” said Joseph M’Connor.

“Quite so. Whisky. You see it there.”

Peter Stulpnagel smiled and shook his head.

“Your argument is not very good,” said he. “When I used to take whisky, I used to find that one glass would excite me, but that six would send me to sleep, which is just the opposite. Now, suppose that electricity were to act in just the opposite way also, what then?”

We three practical men burst out laughing. We had known that our colleague was queer, but we never had thought that he would be as queer as this.

“What then?” repeated Philip Stulpnagel.

“We’ll take our chances,” said the chairman.

“Pray consider,” said Peter, “that workmen who have touched the wires, and who have received shocks of only a few hundred volts, have died instantly. The fact is well known. And yet when a much greater force was used upon a criminal at New York, the man struggled for some little time. Do you not clearly see that the smaller dose is the more deadly?”

“I think, gentlemen, that this discussion has been carried on quite long enough,” said the chairman, rising again. “The point, I take it, has already been decided by the majority of the committee, and Duncan Warner shall be electrocuted on Tuesday by the full strength of the Los Amigos dynamos. Is it not so?”

“I agree,” said Joseph M’Connor.

“I agree,” said I.

“And I protest,” said Peter Stulpnagel.

“Then the motion is carried, and your protest will be duly entered in the minutes,” said the chairman, and so the sitting was dissolved.

The attendance at the electrocution was a very small one. We four members of the committee were, of course, present with the executioner, who was to act under their orders. The others were the United States Marshal, the governor of the gaol, the chaplain, and three members of the press. The room was a small brick chamber, forming an outhouse to the Central Electrical station. It had been used as a laundry, and had an oven and copper at one side, but no other furniture save a single chair for the condemned man. A metal plate for his feet was placed in front of it, to which ran a thick, insulated wire. Above, another wire depended from the ceiling, which could be connected with a small metallic rod projecting from a cap which was to be placed upon his head. When this connection was established Duncan Warner’s hour was come.

There was a solemn hush as we waited for the coming of the prisoner. The practical engineers looked a little pale, and fidgeted nervously with the wires. Even the hardened Marshal was ill at ease, for a mere hanging was one thing, and this blasting of flesh and blood a very different one. As to the pressmen, their faces were whiter than the sheets which lay before them. The only man who appeared to feel none of the influence of these preparations was the little German crank, who strolled from one to the other with a smile on his lips and mischief in his eyes. More than once he even went so far as to burst into a shout of laughter, until the chaplain sternly rebuked him for his ill-timed levity.

“How can you so far forget yourself, Mr. Stulpnagel,” said he, “as to jest in the presence of death?”

But the German was quite unabashed.

“If I were in the presence of death I should not jest,” said he, “but since I am not I may do what I choose.”

This flippant reply was about to draw another and a sterner reproof from the chaplain, when the door was swung open and two warders entered leading Duncan Warner between them. He glanced round him with a set face, stepped resolutely forward, and seated himself upon the chair.

“Touch her off!” said he.

It was barbarous to keep him in suspense. The chaplain murmured a few words in his ear, the attendant placed the cap upon his head, and then, while we all held our breath, the wire and the metal were brought in contact.

“Great Scott!” shouted Duncan Warner.

He had bounded in his chair as the frightful shock crashed through his system. But he was not dead. On the contrary, his eyes gleamed far more brightly than they had done before. There was only one change, but it was a singular one. The black had passed from his hair and beard as the shadow passes from a landscape. They were both as white as snow. And yet there was no other sign of decay. His skin was smooth and plump and lustrous as a child’s.

The Marshal looked at the committee with a reproachful eye.

“There seems to be some hitch here, gentlemen,” said he.

We three practical men looked at each other.

Peter Stulpnagel smiled pensively.

“I think that another one should do it,” said I.

Again the connection was made, and again Duncan Warner sprang in his chair and shouted, but, indeed, were it not that he still remained in the chair none of us would have recognised him. His hair and his beard had shredded off in an instant, and the room looked like a barber’s shop on a Saturday night. There he sat, his eyes still shining, his skin radiant with the glow of perfect health, but with a scalp as bald as a Dutch cheese, and a chin without so much as a trace of down. He began to revolve one of his arms, slowly and doubtfully at first, but with more confidence as he went on.

Again the connection was made, and again Duncan Warner sprang in his chair and shouted, but, indeed, were it not that he still remained in the chair none of us would have recognised him. His hair and his beard had shredded off in an instant, and the room looked like a barber’s shop on a Saturday night. There he sat, his eyes still shining, his skin radiant with the glow of perfect health, but with a scalp as bald as a Dutch cheese, and a chin without so much as a trace of down. He began to revolve one of his arms, slowly and doubtfully at first, but with more confidence as he went on.

“That jint,” said he, “has puzzled half the doctors on the Pacific Slope. It’s as good as new, and as limber as a hickory twig.”

“You are feeling pretty well?” asked the old German.

“Never better in my life,” said Duncan Warner cheerily.

The situation was a painful one. The Marshal glared at the committee. Peter Stulpnagel grinned and rubbed his hands. The engineers scratched their heads. The bald-headed prisoner revolved his arm and looked pleased.

“I think that one more shock——” began the chairman.

“No, sir,” said the Marshal “we’ve had foolery enough for one morning. We are here for an execution, and a execution we’ll have.”

“What do you propose?”

“There’s a hook handy upon the ceiling. Fetch in a rope, and we’ll soon set this matter straight.”

There was another awkward delay while the warders departed for the cord. Peter Stulpnagel bent over Duncan Warner, and whispered something in his ear. The desperado started in surprise.

“You don’t say?” he asked.

The German nodded.

“What! Noways?”

Peter shook his head, and the two began to laugh as though they shared some huge joke between them.

The rope was brought, and the Marshal himself slipped the noose over the criminal’s neck. Then the two warders, the assistant and he swung their victim into the air. For half an hour he hung—a dreadful sight—from the ceiling. Then in solemn silence they lowered him down, and one of the warders went out to order the shell to be brought round. But as he touched ground again what was our amazement when Duncan Warner put his hands up to his neck, loosened the noose, and took a long, deep breath.

“Paul Jefferson’s sale is goin’ well,” he remarked, “I could see the crowd from up yonder,” and he nodded at the hook in the ceiling.

“Up with him again!” shouted the Marshal, “we’ll get the life out of him somehow.”

In an instant the victim was up at the hook once more.

They kept him there for an hour, but when he came down he was perfectly garrulous.

“Old man Plunket goes too much to the Arcady Saloon,” said he. “Three times he’s been there in an hour; and him with a family. Old man Plunket would do well to swear off.”

It was monstrous and incredible, but there it was. There was no getting round it. The man was there talking when he ought to have been dead. We all sat staring in amazement, but United States Marshal Carpenter was not a man to be euchred so easily. He motioned the others to one side, so that the prisoner was left standing alone.

“Duncan Warner,” said he, slowly, “you are here to play your part, and I am here to play mine. Your game is to live if you can, and my game is to carry out the sentence of the law. You’ve beat us on electricity. I’ll give you one there. And you’ve beat us on hanging, for you seem to thrive on it. But it’s my turn to beat you now, for my duty has to be done.”

He pulled a six-shooter from his coat as he spoke, and fired all the shots through the body of the prisoner. The room was so filled with smoke that we could see nothing, but when it cleared the prisoner was still standing there, looking down in disgust at the front of his coat.

“Coats must be cheap where you come from,” said he. “Thirty dollars it cost me, and look at it now. The six holes in front are bad enough, but four of the balls have passed out, and a pretty state the back must be in.”

The Marshal’s revolver fell from his hand, and he dropped his arms to his sides, a beaten man.

“Maybe some of you gentlemen can tell me what this means,” said he, looking helplessly at the committee.

Peter Stulpnagel took a step forward.

“I’ll tell you all about it,” said he.

“You seem to be the only person who knows anything.”

“I AM the only person who knows anything. I should have warned these gentlemen; but, as they would not listen to me, I have allowed them to learn by experience. What you have done with your electricity is that you have increased this man’s vitality until he can defy death for centuries.”

“Centuries!”

“Yes, it will take the wear of hundreds of years to exhaust the enormous nervous energy with which you have drenched him. Electricity is life, and you have charged him with it to the utmost. Perhaps in fifty years you might execute him, but I am not sanguine about it.”

“Great Scott! What shall I do with him?” cried the unhappy Marshal.

Peter Stulpnagel shrugged his shoulders.

“It seems to me that it does not much matter what you do with him now,” said he.

“Maybe we could drain the electricity out of him again. Suppose we hang him up by the heels?”

“No, no, it’s out of the question.”

“Well, well, he shall do no more mischief in Los Amigos, anyhow,” said the Marshal, with decision. “He shall go into the new gaol. The prison will wear him out.”

“On the contrary,” said Peter Stulpnagel, “I think that it is much more probable that he will wear out the prison.”

It was rather a fiasco and for years we didn’t talk more about it than we could help, but it’s no secret now and I thought you might like to jot down the facts in your case-book.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Los Amigos Fiasco (#13)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature