Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Ton van Reen schreef de novelle DE GEVANGENE DIE VERMOORD WERD AANGETROFFEN IN DE LIBERTYSTRAAT in 1962. Dat is vijftig jaar geleden. Hij was toen 20 jaar oud. Het manuscript lag 3 jaar bij Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers. Directeur Johan Veninga en redacteur Martin Ros waren er enthousiast over en verzekerden hem dat het boek bij deze uitgeverij zou verschijnen. Na (te) lang wachten bood Van Reen het boek aan bij Uitgeverij Meulenhoff die het in 1967 publiceerde, samen met de novelle DE MOORD DOOR GEALLIEERDE MILITAIREN EN BURGERS UIT DE LICHTSTAD KORK OP LEDEN VAN HET DOOR DE MIERRIJDER GESTICHTE GEZIN VAN CHERUBIJN, een novelle die hij in 1963 had geschreven.

Beiden novellen zijn, in 6e druk, opgenomen in de uitgave VERZAMELD WERK, DEEL 1, uitgeverij De Geus, isbn 978-90-445-1351-6.

Na verschijning schreef Gerrit Krol in het toenmalige Het Handelsblad: Ik heb lang uitgezien naar een verhaal waarin de hoererij op zo onschuldige wijze wordt behandeld. De Gevangene en De Moord zijn heel gekke, ontroerende idylles, zoals je zelden leest en waarin je, dwars door de onmogelijkheden heen, volledig gelooft. Dat bewijst meteen de kracht van Van Reens schrijverschap dat, behalve kracht, ook zoveel naiefs heeft dat ik me van tijd tot tijd afvroeg hoe het mogelijk is dat iemand zo kan schrijven. Een onvergetelijk boek. Ton van Reen schrijft leerboeken voor schrijvers.

Aad Nuis schreef in de Haagse Post: Van Reen schrijft eigenlijk steeds sprookjes, waarbij de toon onverhoeds kan omslaan van Andersen op zijn charmants in Grimm op zijn gruwelijkst.

Kempis.nl zal beide novellen publiceren.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (A)

Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880)

A

ABELARD: Inutile d’avoir la moindre idée de sa philosophie, ni même de connaître le titre de ses ouvrages. Faire une allusion discrète à la mutilation opérée sur lui par Fulbert. Tombeau d’Eloïse et d’Abélard: si l’on vous prouve qu’il est faux, s’écrier: «Vous m’ôtez mes illusions. «

ABRICOTS: Nous n’en aurons pas encore cette année.

ABSALON: S’il eût porté perruque, Joab n’aurait pu le tuer. Nom facétieux à donner à un ami chauve.

ABSINTHE: Poison extra-violent: un verre et vous êtes mort. Les journalistes en boivent pendant qu’ils écrivent leurs articles. A tué plus de soldats que les Bédouins.

ACADÉMIE FRANCAISE: La dénigrer, mais tâcher d’en faire partie si on peut.

ACCIDENT: Toujours déplorable ou fâcheux (comme si on devait jamais trouver un malheur une chose réjouissante…).

ACCOUCHEMENT: Mot à éviter; le remplacer par événement. «Pour quelle époque attendez-vous l’événement?»

ACHILLE: Ajouter «aux pieds légers»; cela donne à croire qu’on a lu Homère.

ACTRICES: La perte des fils de famille. Sont d’une lubricité effrayante, se livrent à des orgies, avalent des millions, finissent à l’hôpital. Pardon! il y en a qui sont bonnes mères de famille!

ADIEUX: Mettre des larmes dans sa voix en parlant des adieux de Fontainebleau.

ADOLESCENT: Ne jamais commencer un discours de distribution des prix autrement que par «Jeunes adolescents» (ce qui est un pléonasme).

AFFAIRES (Les): Passent avant tout. Une femme doit éviter de parler des siennes. Sont dans la vie ce qu’il y a de plus important. Tout est là.

AGENT: Terme lubrique.

AGRICULTURE: Une des mamelles de l’Etat (l’Etat est du genre masculin, mais ça ne fait rien). On devrait l’encourager. Manque de bras.

AIL: Tue les vers intestinaux et dispose aux combats de l’amour. On en frotta les lèvres de Henri IV au moment où il vient au monde.

AIR: Toujours se méfier des courants d’air. Invariablement le fond de l’air est en contradiction avec la température; si elle est chaude, il est froid, et l’inverse.

AIRAIN: Métal de l’antiquité.

ALBÂTRE: Sert à décrire les plus belles parties du corps de la femme.

ALBION: Toujours précédé de blanche, perfide, positive. Il s’en est fallu de bien peu que Napoléon en fît la conquête. En faire l’éloge: la libre Angleterre.

ALCIBIADE: Célèbre par la queue de son chien. Type de débauché. Fréquentait Aspasie.

ALCOOLISME: Cause de toute les maladies modernes (v. absinthe et tabac).

ALLEMAGNE: Toujours précédé de blonde, rêveuse. Mais quelle organisation militaire.

ALLEMANDS: Peuple de rêveurs (vieux). Ce n’est pas étonnant qu’ils nous aient battus, nous n’étions pas prêts!

AMBITIEUX: En province, tout homme qui fait parler de lui. «Je ne suis pas ambitieux, moi! « veut dire égoïste ou incapable.

AMBITION: Toujours précédé de folle quand elle n’est pas noble.

AMÉRIQUE: Bel exemple d’injustice: C’est Colomb qui la découvrit et elle tire son nom d’Améric Vespuce. Sans la découverte de l’Amérique, nous n’aurions pas la syphilis et le phylloxéra. L’exalter quand même, surtout quand on n’y a pas été. Faire une tirade sur le self-government.

AMIRAL: Toujours brave. Ne jure que par «mille sabords!»

ANDROCLÈS: Citer le lion d’Androclès à propos de dompteurs.

ANGE: Fait bien en amour et en littérature.

ANGLAIS: Tous riches.

ANGLAISES: S’étonner de ce qu’elles ont de jolis enfants.

ANTÉCHRIST: Voltaire, Renan…

ANTIQUITÉ (et tout ce qui s’y rapporte): Poncif, embêtant.

ANTIQUITÉS (les): Sont toujours de fabrication moderne.

APLOMB: Toujours suivi de infernal ou précédé de rude.

APPARTEMENT de garçon: Toujours en désordre, avec des colifichets de femme traînant ça et là. Odeur de cigarettes. On doit y trouver des choses extraordinaires.

ARBALÈTE: Belle occasion pour raconter l’histoire de Guillaume Tell.

ARCHIMÈDE: Dire à son nom: «Euréka! Donnez-moi un point d’appui et je soulèverai le monde.» Il y a encore la vis d’Archimède, mais on n’est pas tenu de savoir en quoi elle consiste.

ARCHITECTES: Tous imbéciles. Oublient toujours l’escalier des maisons.

ARCHITECTURE: Il n’y a que quatre ordre d’architecture. Bien entendu qu’on ne compte pas l’égyptien, le cyclopéen, l’assyrien, l’indien, le chinois, le gothique, le roman, etc.

ARGENT: Cause de tout le mal. Auri sacra fames. Le dieu du jour (ne pas confondre avec Apollon). Les ministres le nomment traitement, les notaires émoluments, les médecins honoraires, les employés appointements, les ouvriers salaires, les domestiques gages. L’argent ne fait pas le bonheur.

ARMÉE: Le rempart de la Société.

ARSENIC: Se trouve partout (rappeler Mme Lafarge). Cependant, il y a des peuples qui en mangent.

ART: Ca mène à l’hôpital. A quoi ça sert, puisqu’on le remplace par la mécanique qui fait mieux et plus vite.

ARTISTES: Tous farceurs. Vanter leur désintéressement (vieux). S’étonner de ce qu’ils sont habillés comme tout le monde (vieux). Gagnent des sommes folles, mais les jettent par les fenêtres. Souvent invités à dîner en ville. Femme artiste ne peut être qu’une catin. Ce qu’ils font ne peut s’appeler travailler.

ASPIC: Animal connu par le panier de figues de Cléopâtre.

ASSASSIN: Toujours lâche, même quand il a été intrépide et audacieux. Moins coupable qu’un incendiaire.

ASTRONOMIE: Belle science. N’est utile que pour la marine. A ce propos, rire de l’astrologie.

ATHÉE: Un peuple d’athée ne saurait subsister.

AUTEUR: On doit «connaître des auteurs«; inutile de savoir leur nom.

AUTRUCHE: Digère les pierres.

AVOCATS: Trop d’avocats à la Chambre. Ont le jugement faussé. Dire d’un avocat qui parle mal:»Oui, mais il est fort en droit.»

Gustave Flaubert:

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (A)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, Archive E-F, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

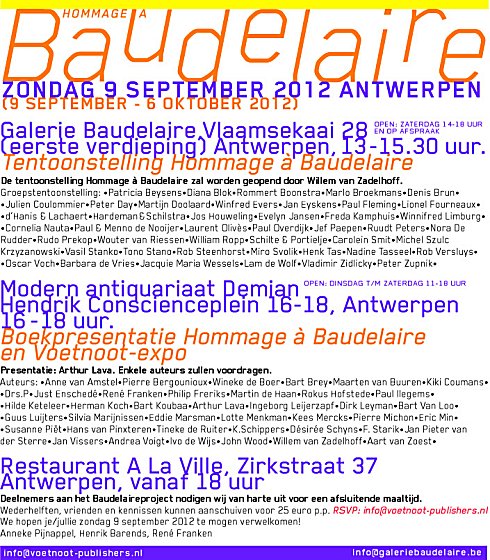

ZONDAG 9 SEPTEMBER 2012 ANTWERPEN

(9 SEPTEMBER – 6 OKTOBER 2012)

Galerie Baudelaire,Vlaamsekaai 28

(eerste verdieping) Antwerpen, 13 – 15.30 uur

Tentoonstelling Hommage à Baudelaire

Modern antiquariaat Demian

Hendrik Conscienceplein 16-18, Antwerpen

16 – 18 uur

Boekpresentatie Hommage à Baudelaire en Voetnoot-expo

Restaurant A La Ville, Zirkstraat 37, Antwerpen, vanaf 18 uur

Groepstentoonstelling: •Patricia Beysens • Diana Blok•Rommert Boonstra • Marlo Broekmans • Denis Brun •Julien Coulommier•Peter Day • Martijn Doolaard•Winfred Evers•Jan Eyskens•Paul Fleming • Lionel Fourneaux • d’Hanis & Lachaert • Hardeman & Schilstra • Jos Houweling • Evelyn Jansen•Freda Kamphuis • Winnifred Limburg • Cornelia Nauta•Paul & Menno de Nooijer • Laurent Olivès • Paul Overdijk • Jef Paepen • Ruudt Peters • Nora De Rudder • Rudo Prekop • Wouter van Riessen•William Ropp •Schilte & Portielje • Carolein Smit•Michel Szulc Krzyzanowski • Vasil Stanko • Tono Stano • Rob Steenhorst • Miro Svolik • Henk Tas•Nadine Tasseel • Rob Versluys • Oscar Voch • Barbara de Vries • Jacquie Maria Wessels • Lam de Wolf • Vladimir Zidlicky • Peter Zupnik •

De tentoonstelling Hommage à Baudelaire zal worden geopend door Willem van Zadelhoff.

Auteurs: •Anne van Amstel •Pierre Bergounioux •Wineke de Boer •Bart Brey •Maarten van Buuren •Kiki Coumans• •Drs.P •Just Enschedé •René Franken •Philip Freriks •Martin de Haan •Rokus Hofstede •Paul Ilegems• •Hilde Keteleer •Herman Koch •Bart Koubaa •Arthur Lava •Ingeborg Leijerzapf •Dirk Leyman •Bart Van Loo• •Guus Luijters •Silvia Marijnissen •Eddie Marsman •Lotte Menkman •Kees Mercks •Pierre Michon •Eric Min• •Susanne Piët •Hans van Pinxteren •Tineke de Ruiter •K.Schippers •Désirée Schyns •F. Starik •Jan Pieter van der Sterre •Jan Vissers •Andrea Voigt •Ivo de Wijs •John Wood •Willem van Zadelhoff •Aart van Zoest•

Presentatie: Arthur Lava. Enkele auteurs zullen voordragen. We hopen je/jullie zondag 9 september 2012 te mogen verwelkomen! Anneke Pijnappel, Henrik Barends, René Franken

OPEN: DINSDAG T/M ZATERDAG 11-18 UUR

OPEN: ZATERDAG 14-18 UUR EN OP AFSPRAAK

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Charles, Freda Kamphuis

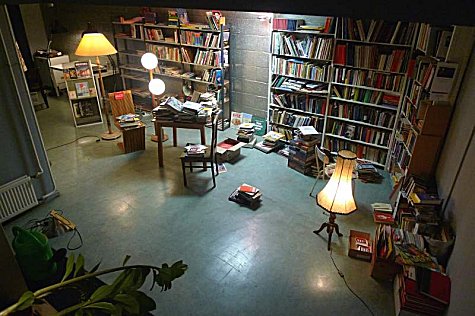

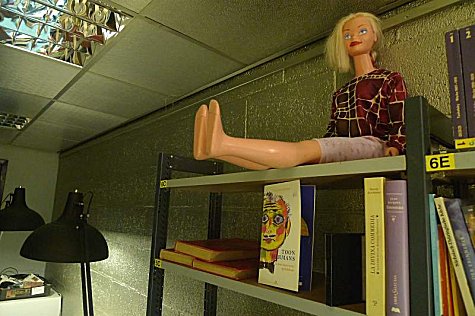

De Terechte Kronkel

‘De Terechte Kronkel’ heet het zaakje. Ik liep er toevallig langs op zoek maar een andere winkel aan de Amsterdamse Vijzelstraat . ‘Het kleinste tweedehandsboekwinkeltje ter wereld!’ riep een bord op het trottoir. Binnen zaten twee heren te discussiëren in een tamelijk duistere ruimte. Eén van hen bleek de eigenaar te zijn, Frans de Jong, en die vertelde dat hij hier maar tijdelijk zat.

Natuurlijk had de naam van zijn zaak te maken met het pseudoniem van Simon Carmiggelt. En natuurlijk had hij veel werk in voorraad van de grote Amsterdamse schrijver. Maar De Jong vond fotoboeken ook interessant en wilde zich meer gaan specialiseren in die categorie. Nou, hij is al op de goede weg, want ik vond een voor mij onbekend boekje van Spencer Tunick, de New Yorkse fotograaf die bekend werd door zijn foto’s van grote massa’s naakte mensen.

Of De Jongs ‘antiquariaatje’ echt het kleinste ter wereld is, waag ik te betwijfelen. Ik meen in Luik wel eens een tweedehandsboekenzaakje bezocht te hebben ter grootte van een ruime inloopkast. In elk geval bleek hier een trap te leiden naar een souterrain waar ook behoorlijk wat te snuffelen viel. Boven een boek van Toon Hermans zat een grote meisjespop te lachen om niets. Kronkel zou er misschien een mooi verhaal over hebben kunnen schrijven.

Joep Eijkens

fleursdumal.nlmagazine

joep eijkens© photos & text 2012

More in: - Bookstores, Joep Eijkens Photos

foto jef van kempen© alberto manguel tilburg 1999

Frederik Mullerlezing en boekensalon met

Alberto Manguel

Vrijdag 31 augustus 2012, 17:00 – 19:00 uur

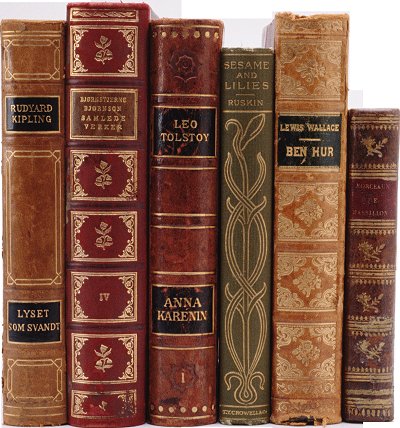

De Frederik Mullerlezing 2012 wordt op 31 augustus uitgesproken door schrijver Alberto Manguel. Deze lezing heeft als titel The Reader as Traveller. Een dag eerder, op 30 augustus, organiseren de Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam een boekensalon met Alberto Manguel. Martin de Haan interviewt hem over zijn boeken en zijn drive om te schrijven.

Voor Alberto Manguel is lezen een constante, haast nomadische reis, van de ene ervaring naar de andere. Deze reis staat in schril contrast met de wereld van de zoekmachines, waar met één druk op de knop de gevraagde data worden geleverd. Op het beeldscherm is alles onder handbereik. Dat is nuttig maar ook beperkend. Manguel pleit ervoor dat wij – als reizigers in cyberspace – ons bewust zijn van deze beperkingen en de vrijheid van de reiziger herwinnen in authentieke leeservaringen.

De Frederik Mullerlezing 2012 vindt plaats op vrijdag 31 augustus om 17.00 uur in de Aula van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, Singel 411. De boekensalon met Alberto Manguel is op donderdag 30 augustus om 17.00 uur in het Museumcafé van de Bijzondere Collecties, Oude Turfmarkt 129 (Rokin). Toegang beide keren gratis.

Dr. Alberto Manguel (Buenos Aires, 1948) is essayist, journalist en bibliofiel. Hij woont en werkt in Frankrijk. In Nederland is hij vooral bekend van de vertalingen Een geschiedenis van het lezen (1996), Kunstlezen: over het kijken naar beeldende kunst (2000), Dagboek van een lezer (2004) en De bibliotheek bij nacht (2007). Manguel ontving vele prijzen, waaronder de Prix Médicis en de Premio Grinzane Cavour.

De Frederik Mullerlezingen zijn vernoemd naar de oprichter van de Bibliotheek van het Boekenvak, die is ondergebracht bij de Bijzondere Collecties. Ze beogen de Boekhistorische Collecties van de UvA in een breed perspectief te plaatsen. De Frederik Mullerlezing 2012 wordt georganiseerd door de Bijzondere Collecties en de leerstoelgroep Boekwetenschap en handschriftenkunde.

De Frederik Mullerlezing 2012 vormt de afsluiting van de summerschool Boeken van ver, die plaatsvindt van 20 t/m 31 augustus. Zie voor het ‘à la carte’-programma van cursussen, workshops en evenementen de link hieronder.

Summerschool ‘Boeken van ver’

Locatie: Aula van de UvA – Singel 411 – 1012 WN Amsterdam

foto jef van kempen© alberto manguel tilburg 1999

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Alberto Manguel, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

Stichting Cools doet boekje open over leesclubs

‘Vrouwen kunnen beter lezen!’

TILBURG – Stichting dr. P.J. Cools msc brengt traditiegetrouw een boekje over lezen en boeken uit bij gelegenheid van ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’, de grootste tweedehandsboekenmarkt van Zuid-Nederland. Ging het boekje vorig jaar over foto’s van lezende mensen vroeger en nu, dit jaar staan leesclubs in de schijnwerper. ‘De Lekkere Letters en andere leesclubs’, luidt de titel van het door Joep Eijkens en Norbert de Vries samengestelde boekje.

Alleen al Midden-Brabant telt tientallen leesclubs. Voor de buitenwereld zijn ze niet erg zichtbaar. Begrijpelijk, want veelal komen de leden thuis bij elkaar. Ze vormen hechte groepen waarin het draait om lezen en vriendschap. En alleen al daarom vormen leesclubs een interessant sociaal en cultureel fenomeen.

Eijkens en De Vries hebben 27 leesclubs uit Midden-Brabant te boek gesteld. “Ik denk, dat we via dit boekje een goede indruk hebben kunnen geven van het functioneren van een leesclub”, zegt De Vries. “Beschouw ons boekje maar als een hommage aan al die groepen.”

Inleven

Opvallend is, dat de meeste leesclubs uitsluitend uit vrouwen bestaan. Leesclubleden zelf hebben daar, desgevraagd, wel verschillende verklaringen voor. Uit hun antwoorden komt naar voren, dat vrouwen zich graag verplaatsen in de wereld van anderen, en daarover graag praten. Een van de vrouwen formuleerde het als volgt:“Vrouwen kunnen beter lezen! Althans, waar het literatuur betreft. Bij een roman moet je je betrokken voelen, moet je je inleven in de personages en omstandigheden. Nou, vrouwen kunnen dat beter dan mannen. Ze zijn nieuwsgierig naar mensen, naar hoe en waarom ze hun leven leiden, zoals ze het leiden (kortom: naar de geschiedenis). Daarnaast willen vrouwen graag hun ideeën, gedachten, ervaringen en gevoelens hierover met elkaar delen. Mannen lezen meer ‘doelgericht’, om kennis te vergaren, nuttige kennis waar ze direct voordeel van hebben. Over literatuur praten is voor mannen vaak small talk bij de borrel. Dat is ietwat gechargeerd, maar in de kern komt het hier wel op neer.”

De Lekkere Letters

‘De Lekkere Letters’ is de naam van één van de 27 Midden-Brabantse leesclubs die in het boekje opgenomen zijn. Veel leesclubs hebben daarentegen geen naam. Alle 27 passeren de revue in woord en beeld, waarbij Joep Eijkens voor de fotografie zorgde.

Uit de 27 portretten valt op te maken, dat het imago van ‘theekransjes’, dat de leesclubs aankleeft, geheel onterecht is. Weliswaar zie je op de foto’s hoe de leden gewoonlijk bijeen zitten aan een tafel, en dat op die tafel niet enkel boeken zichtbaar zijn, maar meestal ook kopjes, een schaaltje met wat lekkernijen, en een koffie- of theepot, maar uit de beschrijvingen blijkt zonneklaar, dat bij de besprekingen de ernst de boventoon voert.

De leden bereiden zich ook serieus voor. Zij lezen het boek, en sommigen bestuderen het: men verzamelt achtergrondinformatie over de auteur, men verdiept zich in de historische situatie die in het boek aan de orde komt, en men slaat er recensies van het boek op na. Ook de boekbespreking zelf gebeurt veelal op een zeer gedegen wijze. Soms komen daarbij plattegrondtekeningen op tafel waarop het verloop van de gebeurtenissen en de rol daarin van de hoofdfiguren in beeld is gebracht. Ook komt het voor dat men tijdens de bijeenkomst naar de muziek luistert die in het boek wordt genoemd.

Géén ‘small talk’

‘Dit alles staat ver af van small talk en theekransjes’, aldus Norbert de Vries, tevens voorzitter van de stichting die het boekje uitgeeft. ‘Naast gedegenheid is er genegenheid, ofwel het sociale aspect van de leesclubs. Vriendschap en plezier enerzijds, en belangstelling voor literatuur anderzijds: die beide elementen vormen de kern van de leesclub’.

Sommige leesclubs komen voort uit een vriendinnengroep, andere wórden een vriendinnengroep. De onderlinge band is vaak zeer sterk. Dit leidt er toe, dat veel clubs ook activiteiten op een ‘aanpalend’ terrein gaan ontwikkelen: het gezamenlijk bezoek aan tentoonstelling, film of toneel, of het organiseren van een eigen weekend met daarin culturele/literaire excursies.

‘De Lekkere Letters en andere leesclubs’ . Tekst Joep Eijkens en Norbert de Vries. Fotografie Joep Eijkens. Het boekje is op de boekenmarkt ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’ op 26 augustus 2012 voor 7,50 euro te koop bij de kraam van de Stichting dr P.J. Cools msc.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, The Art of Reading

15e editie Boeken rond het Paleis Tilburg

Zondag 26 augustus 2012

grootste boekenmarkt van Zuid-Nederland

met ruim 300 kramen in het centrum van Tilburg

van 10.00 – 17.00 uur

Organisatie Stichting Cools Tilburg

Informatie per email: info@beo-events.nl

De locatie omvat globaal het gebied rond de het Stadhuis en het oude Paleis-Raadhuis en de omgeving Bibliotheek-Centrum: Willemsplein – Stadhuisplein – Katterug – Paleisring – Koningsplein

De vijftiende editie van ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’ al weer! En natuurlijk staan ze er a.s. zondag, zoals steeds: de meer dan 300 kramen met leesvoer, te kust en te keur. Met een hart dat vol verwachting klopt, gaan de bezoekers weer rond, op zoek naar dat boek waar ze al zo lang hun zinnen op hebben gezet, of gewoon om te kijken ‘of er iets interessants bij zit’. De sneupers hopen op een gouden vondst, de handelaren verlangen naar een mooie omzet, en iedereen ziet graag mooi, droog weer en een aangename sfeer tegemoet. Komaan, laten we er ook dit jaar weer een boekenfeest van maken! De organiserende Stichting dr. P.J. Cools msc zou graag zien, dat om 17.00 uur de duizenden bezoekers met tassen vol boeken huiswaarts keren, voldaan terugkijkend op een welbestede dag. In ieder geval, de marktkramen staan klaar, vol boeken. In dit boekje vindt u alle deelnemers vermeld, en er is een kaartje waarop u, via de kraamnummers, de handelaar van uw keuze kunt vinden.

De markt is zondag open van 10 tot 17 uur. De officiële opening vindt om 12.30 uur plaats, net als vorig jaar in de bibliotheek aan het Koningsplein. De opening zal worden verricht door wethouder Erik de Ridder. Hem zal ook het eerste exemplaar van het Cools-boekje van dit jaar worden overhandigd. Hadden we vorig jaar een boekje met foto’s van lezenden, dit jaar presenteren we een boekje over leesclubs, met veel foto’s daarin van over boeken met elkaar van gedachten wisselende lezers. In totaal 27 leesclubs uit Midden-Brabant hebben meegewerkt aan het boekje “De Prettige Letters en andere leesclubs”.

De markt zal worden opgeluisterd met muziek van de BE-Brassband, een achtkoppig ensemble dat het motto voert: Yes… we can brass. Voorts zijn er optredens van de dichter Martin Beversluis.

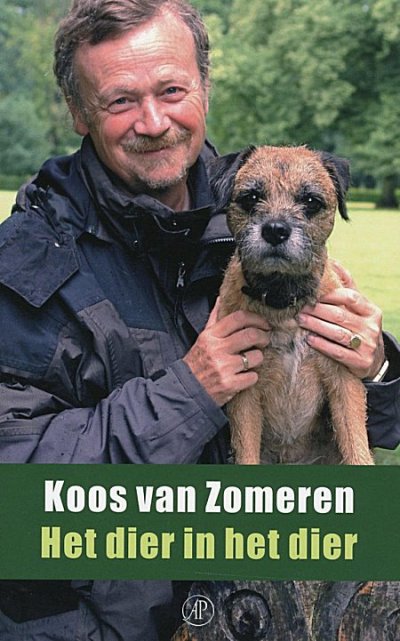

Het literaire programma dat altijd aan de boekenmarkt verbonden is geweest (en nog steeds is!), hebben we dit jaar naar de zaterdagavond verschoven. Het thema van deze avond: het schrijven van een column. Koos van Zomeren en Ronald Giphart zullen wellicht wat ‘tricks of the trade’ uitleggen.

B e s t u u r S t i c h t i n g D r P J C o o l s T i l b u r g

Routebeschrijving

Te voet vanaf het Centraal Station (8 min) : Station uitlopen. – Spoorlaan oversteken. – Rechtdoor Stationsstraat volgen. – Bij kruising (vijfsprong) rechtdoor Nieuwlandstraat volgen. Voorbij boekhandel Livius, bij de volgende kruising, eerst links, dan rechts. – U bent aan het begin van de boekenmarkt vanaf de Heikese kerk.

Met de auto vanuit de richting Den Bosch/Eindhoven: Afrit 10 Tilburg – Hilvarenbeek voorbij rijden. – Neem afrit 11 Goirle – Tilburg – Verder de aanwijzingen volgen zoals hieronder bij ‘richting Breda’ is aangegeven.

Met de auto vanuit de richting Breda: Afrit 11 Goirle – Tilburg nemen. – Volg Tilburg/Waalwijk (niet Tilburg Zuid). – U komt dan op de Ringbaan West. – Volg de borden Tilburg Centrum. – Volg verwijsborden parkeergarages Schouwburg of Koningsplein.

Met de auto vanuit de richting Waalwijk: Vanaf Waalwijk komt u Tilburg binnen via de Midden-Brabantweg. – Deze gaat na de rotonde (met het ‘Draaiende huis’) over in Ringbaan West (u gaat hier rechtdoor). – Via een viaduct het spoor over. – Direct daarna linksaf de Hart van Brabantlaan in, richting Centrum. – Volg verwijsborden parkeergarages Schouwburg of Koningsplein.

boeken rond het paleis – stichting p.j. cools tilburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers

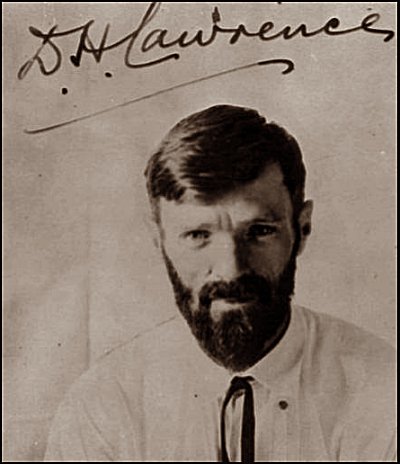

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Green

The dawn was apple-green,

The sky was green wine held up in the sun,

The moon was a golden petal between.

She opened her eyes, and green

They shone, clear like flowers undone

For the first time, now for the first time seen.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Boekenmarkt Tilburg 2012:

Giphart en Van Zomeren over de column

Op zaterdagavond 25 augustus organiseert de Stichting Cools in het kader van de boekenmarkt ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’ een literaire avond in de bovenzaal van stadscafé MeesterS. De avond zal in het teken staan van de column.

Koos van Zomeren en Ronald Giphart zijn auteurs die niet alleen romans, maar ook columns hebben geschreven.

Ronald Giphart schrijft ze voor de Volkskrant waar hij de opvolger is van de meesterlijke columnist Martin Bril (volgens Giphart ‘de columnistste columnist van ons taalgebied’).

Koos van Zomeren is vermaard als de schrijver van de duizend-en-een schitterende miniatuurtjes die tussen 1992 en 1995 op de voorpagina van NRC Handelsblad verschenen. Twee uitstekende columnisten dus, die met elkaar van gedachten zullen wisselen over het schrijven van columns. U kunt daar bij zijn, gratis en voor niets! De bijeenkomst duurt van 19.30 uur tot 21.30 uur. Wees op tijd.

Belangstellenden moeten reserveren. Zij worden verzocht zich vóór 21 augustus via email op het adres: nvadevries@home.nl aan te melden.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (26)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

4

What fools all the people are who declare that life is a mystery, wretches who seek to explain by the use of reason what reason is powerless to explain!

To set life before one as an object of study is absurd, because life, when set before one like that, inevitably loses all its real consistency and becomes an abstraction, void of meaning and value. And how after that is it possible to explain it to oneself? You have killed it. The most you can do now is to dissect it.

Life is not explained; it is lived.

Reason exists in life; it cannot exist apart from it. And life is not to be set before one, but felt within one and lived. How many of us, emerging from a passion as we emerge from a dream, ask ourselves:

“I? How can I have been like that? How could I do such a thing?”

We are no longer able to account for it; just as we are powerless to explain how other people can give a meaning and a value to certain things which for us have ceased or have not yet begun to have either. The reason, which lies in these things, we seek outside them. Can we find it? Outside life there is nullity. To observe this nullity, with the reason which abstracts itself from life, is still to live, is still a ‘nullity’ in our life: a sense of mystery: religion. It may be desperate, if it has no illusions; ft may appease itself by plunging back into life, no longer as of old but there, into that ‘nullity’, which at once becomes ‘all’.

How clearly I have learned all this in a few days, since I began really to feel! I mean, since I began to feel ‘myself also’, for other people I have always felt within me, and have found it easy therefore to explain them to myself and to sympathise with them.

But the feeling that I have of myself, at this moment, is most bitter.

On your account, Signorina Luisetta, for all that you are so compassionate! Indeed, just because you are so compassionate. I cannot say it to you, I cannot make you understand. I would rather not say it to myself, I would rather not understand it myself either. But no, I am no longer ‘a thing’, and this silence of mine is no longer an ‘inanimate’ silence. I wished to draw other people’s attention to this silence, but now I ‘suffer’ from it myself, so keenly.

I go on, nevertheless, welcoming everyone into it. I feel, however, that everyone hurts me now who comes into it, as into a place of certain hospitality. My silence would like to draw ever more closely round about me.

Here, in the meantime, is Cavalena, who has settled himself in it, poor man, as in his own home. He comes, whenever he can, to talk over with me, always with fresh arguments, or on the most futile pretexts, his own misfortunes. He tells me that it is impossible, on account of his wife, to keep Nuti in the house any longer, and that I shall have to find him a lodging elsewhere, as soon as he has recovered. Two dramas, side by side, cannot be kept going. Especially since Nuti’s drama is one of passion, of women. … Cavalena requires lodgers with judgment and self-control. He would gladly pay out of his own pocket to have all men serious, dignified, pure and enjoying a spotless reputation for chastity, with which to crush his wife’s furious hatred for the whole of the male sex. It falls to him every evening to pay the penalty–the fine, he calls it–for all the misdeeds of men, recorded in the columns of the newspapers, as though he were the author or the necessary accomplice of every seduction, of every adultery.

“You see?” his wife screams at him, her finger pointing to the paragraph in the paper: “You see what ‘you men’ are capable of?”

And in vain does the poor wretch try to make her see that in each case of adultery, for every erring man who betrays his wife, there must be also an erring woman, his accomplice in the betrayal. Cavalena thinks that he has found a triumphant argument, instead of which he sees Signora Nene’s mouth form that round O with her finger across it, the familiar expression which means:

“Fool!”

Excellent logic! That we know! And does not Signora Nene hate the whole of the female sex as well?

Drawn on by the unreal, pressing arguments of that terrible reasoning insanity which never comes to a halt at any conclusion, he always finds himself, in the end, lost or bewildered, in a false situation, from which he has no idea how to escape. Why, inevitably! If he is compelled to alter, to complicate the most obvious and natural things, to conceal the simplest and commonest actions; an acquaintance, an introduction, a chance meeting, a look, a smile, a word, in which his wife might suspect who knows what secret understandings and plots; then inevitably, even when he is engaged upon an abstract discussion with her, there must emerge incidents, contradictions which all of a sudden, unexpectedly, reveal him and represent him, with every appearance of truth, a liar and impostor. Revealed, caught out in his own innocent deception, which however he himself now sees cannot any longer appear innocent in his wife’s eyes; exasperated, with his back to the wall, in the face of the evidence, he still persists in denying it, and so, over and over again, for no reason, they come to quarrels, scenes, and Cavalena escapes from the house and stays away for a fortnight or three weeks, until he is once more conscious of being a doctor and the thought recurs to him of his abandoned daughter, “poor, dear, sweet little soul,” as he calls her.

It is a great pleasure to me when he begins to talk to me of her; but for that very reason I never do anything to incite him to speak of her: I should feel that I was taking a base advantage of her father’s weakness to penetrate, by way of his confidences, into the private life of that poor, dear, sweet little soul. No, no! Often I have even been on the point of forbidding him to continue.

Ages ago, it seems to Cavalena, his Sesè ought to have married, to have had a life of her own away from the hell of this house! Her mother, on the other hand, does nothing but shout at her, day after day:

“Never marry, mind! Don’t marry, you fool! Don’t do anything so mad!”

“And Sesè? Sesè?” I feel tempted to ask him; but, as usual, I remain silent.

Poor Sesè, perhaps, does not know herself what she would like to do. Perhaps, on some days, like her father, she would wish it to be to-morrow; on other days she will feel the bitterest disgust when she sees some hint of it pass between her parents. For undoubtedly they, with their degrading scenes, must have rent asunder all her illusions, all of them, one after another, shewing her through the rents the most sickening crudities of married life.

They have prevented her, meanwhile, from securing her freedom in any other way, the means of providing henceforward for herself, of being able to leave this house and live on her own. They will have told her that, thank heaven, there is no need for her to do so: an only child, she will some day have the whole of her mother’s fortune for herself. Why degrade herself by becoming a teacher or looking out for some other employment? She can read, study what she pleases, play the piano, do embroidery, a free woman in her own home.

A fine freedom!

The other evening, fairly late, when we had all left the room in which Nuti had already fallen asleep, I saw her sitting on the balcony. We live in the last house in Via Veneto, and have in front of us the open space of the Villa Borghese. Four little balconies on the top floor, on the cornice of the building. Cavalena was sitting on another balcony, and appeared to be lost in contemplation of the stars.

Suddenly, in a voice that seemed to come from a distance, almost from the sky, suffused with infinite pain, I heard him say:

“Sesè, do you see the Pleiads?”

She pretended to look: perhaps her eyes were filled with tears.

And her father:

“There they are… above your head… that little cluster of stars… do you see them?”

She nodded her head; yes, she saw them.

“Fine, aren’t they, Sesè? And do you see how bright Capella is?”

The stars… Poor Papa! A fine distraction. … And with one hand he straightened, stroked on his temples the curling locks of his artistic wig, while with the other… what? Why, yes … he was holding on his knee Piccini, his enemy, and was stroking her head…. Poor Papa! This must be one of his most tragic and pathetic moments!

There came from the Villa a long, slow slight rustle of leaves; from the deserted street an occasional sound of footsteps and the rapid clattering sound of a carriage driven in haste. The clang of the bell and the long-drawn whine of the trolley running along the electric wire of the tramway seemed to tear the street apart and fling it violently in its wake, with the houses and trees. Then all was silent, and in the weary calm returned the distant sound of a piano from one of the houses. It was a gentle, almost veiled, melancholy sound, which drew the spirit, fixed it at a definite point, as though to enable it to perceive how heavy was the cloak of sadness suspended over everything.

Ah, yes–Signorina Luisetta was perhaps thinking–marriage…. She was imagining, perhaps, that it was she who was playing, in a strange house, far away, that piano, to lull to sleep the pain of the sad, early memories which have poisoned her life for all time.

Will it be possible for her to illude herself? Will she be able to prevent from falling, withered, like the petals of flowers, on the silent air, chill with a want of confidence that is now perhaps insuperable, all the innocent graces that from time to time spring up in her soul?

I observe that she is spoiling herself, deliberately; she makes herself, every now and then, hard, bristling, so as not to appear tender and credulous. Perhaps she would like to be gay, frolicsome, as in more than one light moment of oblivion, when she has just risen from her bed, her eyes have suggested to her, from her mirror: those eyes of hers, which would so gladly laugh, keen and brilliant, and which she instead condemns to appear absent, or shy and sullen. Poor, lovely eyes! How often under her knitted brows does she not fix them on the empty air, while through her nostrils she breathes a long sigh in silence, as though she did not wish it to reach even her own ears! And how they cloud over and change colour, whenever she breathes one of those silent sighs.

Certainly she must have learned long ago to distrust her own impressions, perhaps in the fear lest she be gradually seized by the same malady as her mother. This is clearly shewn by her abrupt changes of expression, a sudden pallor following a sudden crimson flushing of her whole face, a smiling return to serenity after a fleeting cloud. Who knows how often, as she walks the streets with her father and mother, she must feel herself stabbed by every sound of laughter, and how often she must have the strange feeling that even that little blue frock, of Swiss silk, light as a feather, is weighing upon her like the habit of a cloistered nun and that the straw hat is crushing her head; and be tempted to tear off the blue silk, to wrench the straw from her head and tear it in pieces furiously with both hands and fling it… in her mother’s face? No… in her father’s, then? No… on the ground, on the ground, trampling it underfoot. Because it must seem to her a masquerade, an idiotic farce, to go about dressed like that, like a respectable person, like a young lady who is under the illusion that she is cutting a figure, or rather who lets it be seen that she has some beautiful dream in her mind, when presently at home, and even now in the street, everything that is most ugly, most brutal, most savage in life must be disclosed, must spring to light in those almost daily scenes between her parents, to smother her in misery and shame and disgrace.

And this reflexion more than any other seems to me to have profoundly penetrated her soul: that in the world, as her parents create it for themselves and round about her with their comic appearance, with the grotesque absurdity of that furious jealousy, with the disorder of their existence, there can be no room, air nor light for her charm. How can charm shew itself, breathe, refresh itself in a delicate, light and airy hue, in the midst of that ridicule which holds it down and stifles and obscures it?

She is like a butterfly cruelly fastened down with a pin, while still alive. She dares not beat her wings, not only because she has no hope of freeing herself, but also and even more because she might attract attention.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (26)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

3

I have laid these notes aside for some days.

They have been days of sorrow and trepidation. They are still not quite over; but now the storm, which broke with terrific force in the soul of this unhappy man whom all of us here have vied with one another in helping compassionately and with all the more devotion in that he was virtually a stranger to us all and what little we knew of him combined with his appearance and the suggestion of fatality that he conveyed to inspire in us pity and a keen interest in his most wretched plight; this storm, I say, seems to be shewing signs of gradually abating. Unless it is only a brief lull. I fear it. Often, at the height of a gale, a formidable peal of thunder succeeds in clearing the sky for a little, but presently the mass of clouds, rent asunder for a moment, return to accumulate slowly and ever more menacingly, and the gale having increased its strength breaks out afresh, more furious than before. The calm, in fact, in which Nuti’s spirit seems gradually to be gathering strength after his delirious ravings and the horrible frenzy of all these days, is tremendously dark, just like the calm of a sky in which a storm is gathering.

No one takes any notice, or seems to take any notice of this, perhaps from the need which we all feel to heave a momentary sigh of relief, saying that in any case the worst is over. We ought, we intend to adjust first, to the best of our ability, ourselves, and also everything round us, swept by the whirlwind of his madness; because there remains not only in all of us but even in the room, in the very furniture of the room, a sort of blind stupefaction, a strange uncertainty in the appearance of everything, as it were an air of hostility, suspended and diffused.

In vain do we detach ourselves from the outburst of a soul which from its profoundest depths hurls forth, broken and disordered, the most recondite thoughts, never yet confessed to itself even, its most serious and awful feelings, the strangest sensations which strip things of every familiar meaning, to give them at once another, unexpected meaning, with a truth that springs forth and imposes itself, disconcerting and terrifying. The terror is due to our recognition, with an appalling clarity, that madness dwells and lurks within each of us and that a mere trifle may let it loose: release it for a moment from the elastic web of present consciousness, and lo, all the imaginings accumulated in years past and now wandering unconnected; the fragments of a life that has remained hidden, because we could not or would not let it be reflected in ourselves by the light of reason; dubious actions, shameful falsehoods, dark hatreds, crimes meditated in the shadow of our inward selves and planned to the last detail, and forgotten memories and unconfessed desires burst in tumultuous, with diabolical fury, roaring like wild beasts. On more than one occasion, we all looked at one another with madness in our eyes, the terror of the spectacle of that madman being sufficient to release in us too for a moment the elastic net of consciousness. And even now we eye askance, and go up and touch with a sense of misgiving some object in the room which was for a moment illumined with the sinister light of a new and terrible meaning by the sick man’s hallucinations; and, going to our own rooms, observe with stupefaction and repugnance that… yes, positively, we too have been overborne by that madness, even at a distance, even when alone: we find here and there clear signs of it, pieces of furniture, all sorts of things, strangely out of place.

We ought, we intend to adjust ourselves, we need to believe that the patient is now in this state, in this brooding calm, because he is still stunned by the violence of his final outbursts and is now exhausted, worn out.

There suffices to support this deception a slight smile of gratitude which he just perceptibly offers with his lips or eyes to Signorina Luisetta: a breath, an imperceptible glimmer which does not, in my opinion, emanate from the sick man, but is rather suffused over his face by his gentle nurse, whenever she draws near and bends over the bed.

Alas, how she too is worn out, his gentle nurse! But no one gives her a thought; least of all herself. And yet the same storm has torn up and swept away this innocent creature!

It has been an agony of which as yet perhaps not even she can form any idea, because she still perhaps has not with her, within her, her own soul. She has given it to him, as a thing not her own, as a thing which he in his delirium might appropriate to derive from it refreshment and comfort.

I have been present at this agony. I have done nothing, nor could I perhaps have done anything to prevent it. But I see and confess that I am revolted by it. Which means that my feelings are compromised. Indeed, I fear that presently I may have to make another painful confession to myself.

This is what has happened: Nuti, in his delirium, mistook Signorina Luisetta for Duccella and, at first, inveighed furiously against her, shouting in her face that her obduracy, her cruelty to him were unjust, since he was in no way to blame for the death of her brother, who, of his own accord, like an idiot, like a madman, had killed himself for that woman; then, as soon as she, overcoming her first terror, grasping at once the nature of his hallucination, went compassionately to his side, lie refused to let her leave him for a moment, clasped her tightly to him, sobbing broken-heartedly or murmuring the most burning, the tenderest words of love to her, and caressing her or kissing her hands, her hair, her brow.

And she allowed him to do it. And all the rest of us allowed it. Because those words, those caresses, those embraces, those kisses were not intended for her: they were for a hallucination, in which his delirium found peace. And so we had to allow him. She, Signorina Luisetta, made her heart pitiful and loving for another girl’s sake; and this heart, thus made pitiful and loving, she gave to him, as a thing not her own, but belonging to that other girl, to Duccella. And while he appropriated that heart, she could not, must not appropriate those words, those caresses, those kisses…. But she trembled at them in every fibre of her body, poor child, ready from the first moment to feel such pity for this man who was suffering so on account of the other woman. And not on her own behalf, who did really pity him, did it come to her to feel pitiful, but for that other, whom she naturally supposes to be harsh and cruel. Well, she has given her pity to the other, that the other might pass it on to him, and by him–through the medium of Luisetta’s body–be loved and caressed in return. But love, love, who has given that? It was she that had to give it, to give love, together with her pity. And the poor child has given it. She knows, she feels that she has given it, with all her soul, with all her heart; and at the same time she must suppose that she has given it for the other.

The result has been as follows: that while he, now, is gradually returning to himself and collecting himself, and shutting himself up again darkly in his trouble; she remains empty and lost, held in suspense, without a gleam in her eye, as though she had lost her wits, a ghost, the ghost that entered into his hallucination. For him, the ghost has vanished, and with the ghost, love. But this poor child who has emptied herself to fill that ghost with herself, her love, her pity, is now herself left a ghost; and he notices nothing. He barely smiles at her in gratitude. The remedy has proved effective: the hallucination has vanished: nothing more at present, is that it?

I should not be so distressed, had I not, for all these days, seen myself obliged to bestow my pity, also, to spend myself, to run in all directions, to sit up for several nights in succession, not from a feeling that was genuinely my own, that is to say one inspired in me by Nuti, as I could have wished; but from a different feeling, one of pity indeed, but of interested pity, so interested that it made and still makes appear false and odious to me the pity which I she-wed and am still shewing for Nuti.

I feel that, as a witness of the sacrifice (without doubt involuntary) which he has made of Signorina Luisetta’s heart, I, who seek to obey my true feelings, ought to have withdrawn my pity from him. I did indeed withdraw it inwardly, to pour it all upon that poor, tormented little heart, but I continued to shew pity for him, seeing that I could do no less, compelled by her sacrifice, which was even greater. If she actually subjected herself to that torture ‘out of pity’ for him, could I, could the rest of us shrink from devotion, fatigue, proofs of Christian charity that were far less? For me to draw back meant my admitting and letting it be seen that she was undergoing this torture not ‘out of pity only’, but also ‘for love’ of him, indeed principally ‘for love’. And that could not, must not be. I have had to pretend, because she has had to believe that she was bestowing her love upon him for that other woman. And I have pretended, albeit with self-contempt, marvellously. Only in this way have I been able to modify her attitude towards myself; to make her my friend again. And yet, by shewing myself for her sake so compassionate towards Nuti, I have perhaps lost the one way that remained to me of calling her back to herself; that, namely, of proving to her that Duccella, on whose behalf she imagines that she loves him, has no reason whatever to feel any pity for him. Were I to give Duccella her true shape, her ghost, that loving and pitiful ghost, into which she, Signorina Luisetta, has transformed herself, would have to vanish, and leave her, SignorinaLuisetta, with her love ‘unjustified’ and in no way sought by him: because he has sought it from the other, not from her, and she has given it to him for the other, and not for herself, thus publicly, before us all.

Very good, but if I know that she has really given it to him, beneath this pious fiction of pity, upon which I am now weaving sophistries?

As Aldo Nuti thinks Duccella hard and cruel, so she would think me hard and cruel, were I to tear from her the veil of this pious fiction. She is a sham Duccella, simply because she is in love; and she knows that the true Duccella has not the slightest reason to be in love; she knows it from the very fact that Aldo Nuti, now that his hallucination has passed, no longer sees any sign of love in her, and sadly just thanks her for her pity.

Perhaps, at the cost of suffering a little more, she might cover herself, but only on condition that Duccella became really pitiful, upon learning the wretched plight to which her former sweetheart had been brought, and appeared in person here, by the bed upon which he lies, to give him her love again and so to save him. But Duccella will not come. And Signorina Luisetta will continue to pretend to all of us and also to herself, in good faith, that it is for her sake that she is in love with Aldo Nuti.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Whales Weep Not!

They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains

the hottest blood of all, and the wildest, the most urgent.

All the whales in the wider deeps, hot are they, as they urge

on and on, and dive beneath the icebergs.

The right whales, the sperm-whales, the hammer-heads, the killers

there they blow, there they blow, hot wild white breath out of

the sea!

And they rock, and they rock, through the sensual ageless ages

on the depths of the seven seas,

and through the salt they reel with drunk delight

and in the tropics tremble they with love

and roll with massive, strong desire, like gods.

Then the great bull lies up against his bride

in the blue deep bed of the sea,

as mountain pressing on mountain, in the zest of life:

and out of the inward roaring of the inner red ocean of whale-blood

the long tip reaches strong, intense, like the maelstrom-tip, and

comes to rest

in the clasp and the soft, wild clutch of a she-whale’s

fathomless body.

And over the bridge of the whale’s strong phallus, linking the

wonder of whales

the burning archangels under the sea keep passing, back and

forth,

keep passing, archangels of bliss

from him to her, from her to him, great Cherubim

that wait on whales in mid-ocean, suspended in the waves of the

sea

great heaven of whales in the waters, old hierarchies.

And enormous mother whales lie dreaming suckling their whale-

tender young

and dreaming with strange whale eyes wide open in the waters of

the beginning and the end.

And bull-whales gather their women and whale-calves in a ring

when danger threatens, on the surface of the ceaseless flood

and range themselves like great fierce Seraphim facing the threat

encircling their huddled monsters of love.

And all this happens in the sea, in the salt

where God is also love, but without words:

and Aphrodite is the wife of whales

most happy, happy she!

and Venus among the fishes skips and is a she-dolphin

she is the gay, delighted porpoise sporting with love and the sea

she is the female tunny-fish, round and happy among the males

and dense with happy blood, dark rainbow bliss in the sea.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature