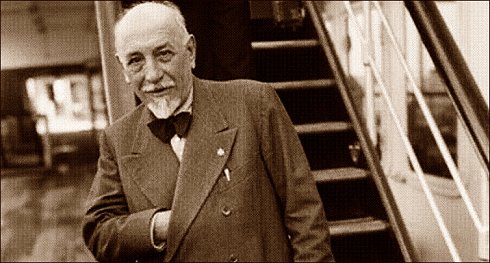

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (26)

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (26)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

4

What fools all the people are who declare that life is a mystery, wretches who seek to explain by the use of reason what reason is powerless to explain!

To set life before one as an object of study is absurd, because life, when set before one like that, inevitably loses all its real consistency and becomes an abstraction, void of meaning and value. And how after that is it possible to explain it to oneself? You have killed it. The most you can do now is to dissect it.

Life is not explained; it is lived.

Reason exists in life; it cannot exist apart from it. And life is not to be set before one, but felt within one and lived. How many of us, emerging from a passion as we emerge from a dream, ask ourselves:

“I? How can I have been like that? How could I do such a thing?”

We are no longer able to account for it; just as we are powerless to explain how other people can give a meaning and a value to certain things which for us have ceased or have not yet begun to have either. The reason, which lies in these things, we seek outside them. Can we find it? Outside life there is nullity. To observe this nullity, with the reason which abstracts itself from life, is still to live, is still a ‘nullity’ in our life: a sense of mystery: religion. It may be desperate, if it has no illusions; ft may appease itself by plunging back into life, no longer as of old but there, into that ‘nullity’, which at once becomes ‘all’.

How clearly I have learned all this in a few days, since I began really to feel! I mean, since I began to feel ‘myself also’, for other people I have always felt within me, and have found it easy therefore to explain them to myself and to sympathise with them.

But the feeling that I have of myself, at this moment, is most bitter.

On your account, Signorina Luisetta, for all that you are so compassionate! Indeed, just because you are so compassionate. I cannot say it to you, I cannot make you understand. I would rather not say it to myself, I would rather not understand it myself either. But no, I am no longer ‘a thing’, and this silence of mine is no longer an ‘inanimate’ silence. I wished to draw other people’s attention to this silence, but now I ‘suffer’ from it myself, so keenly.

I go on, nevertheless, welcoming everyone into it. I feel, however, that everyone hurts me now who comes into it, as into a place of certain hospitality. My silence would like to draw ever more closely round about me.

Here, in the meantime, is Cavalena, who has settled himself in it, poor man, as in his own home. He comes, whenever he can, to talk over with me, always with fresh arguments, or on the most futile pretexts, his own misfortunes. He tells me that it is impossible, on account of his wife, to keep Nuti in the house any longer, and that I shall have to find him a lodging elsewhere, as soon as he has recovered. Two dramas, side by side, cannot be kept going. Especially since Nuti’s drama is one of passion, of women. … Cavalena requires lodgers with judgment and self-control. He would gladly pay out of his own pocket to have all men serious, dignified, pure and enjoying a spotless reputation for chastity, with which to crush his wife’s furious hatred for the whole of the male sex. It falls to him every evening to pay the penalty–the fine, he calls it–for all the misdeeds of men, recorded in the columns of the newspapers, as though he were the author or the necessary accomplice of every seduction, of every adultery.

“You see?” his wife screams at him, her finger pointing to the paragraph in the paper: “You see what ‘you men’ are capable of?”

And in vain does the poor wretch try to make her see that in each case of adultery, for every erring man who betrays his wife, there must be also an erring woman, his accomplice in the betrayal. Cavalena thinks that he has found a triumphant argument, instead of which he sees Signora Nene’s mouth form that round O with her finger across it, the familiar expression which means:

“Fool!”

Excellent logic! That we know! And does not Signora Nene hate the whole of the female sex as well?

Drawn on by the unreal, pressing arguments of that terrible reasoning insanity which never comes to a halt at any conclusion, he always finds himself, in the end, lost or bewildered, in a false situation, from which he has no idea how to escape. Why, inevitably! If he is compelled to alter, to complicate the most obvious and natural things, to conceal the simplest and commonest actions; an acquaintance, an introduction, a chance meeting, a look, a smile, a word, in which his wife might suspect who knows what secret understandings and plots; then inevitably, even when he is engaged upon an abstract discussion with her, there must emerge incidents, contradictions which all of a sudden, unexpectedly, reveal him and represent him, with every appearance of truth, a liar and impostor. Revealed, caught out in his own innocent deception, which however he himself now sees cannot any longer appear innocent in his wife’s eyes; exasperated, with his back to the wall, in the face of the evidence, he still persists in denying it, and so, over and over again, for no reason, they come to quarrels, scenes, and Cavalena escapes from the house and stays away for a fortnight or three weeks, until he is once more conscious of being a doctor and the thought recurs to him of his abandoned daughter, “poor, dear, sweet little soul,” as he calls her.

It is a great pleasure to me when he begins to talk to me of her; but for that very reason I never do anything to incite him to speak of her: I should feel that I was taking a base advantage of her father’s weakness to penetrate, by way of his confidences, into the private life of that poor, dear, sweet little soul. No, no! Often I have even been on the point of forbidding him to continue.

Ages ago, it seems to Cavalena, his Sesè ought to have married, to have had a life of her own away from the hell of this house! Her mother, on the other hand, does nothing but shout at her, day after day:

“Never marry, mind! Don’t marry, you fool! Don’t do anything so mad!”

“And Sesè? Sesè?” I feel tempted to ask him; but, as usual, I remain silent.

Poor Sesè, perhaps, does not know herself what she would like to do. Perhaps, on some days, like her father, she would wish it to be to-morrow; on other days she will feel the bitterest disgust when she sees some hint of it pass between her parents. For undoubtedly they, with their degrading scenes, must have rent asunder all her illusions, all of them, one after another, shewing her through the rents the most sickening crudities of married life.

They have prevented her, meanwhile, from securing her freedom in any other way, the means of providing henceforward for herself, of being able to leave this house and live on her own. They will have told her that, thank heaven, there is no need for her to do so: an only child, she will some day have the whole of her mother’s fortune for herself. Why degrade herself by becoming a teacher or looking out for some other employment? She can read, study what she pleases, play the piano, do embroidery, a free woman in her own home.

A fine freedom!

The other evening, fairly late, when we had all left the room in which Nuti had already fallen asleep, I saw her sitting on the balcony. We live in the last house in Via Veneto, and have in front of us the open space of the Villa Borghese. Four little balconies on the top floor, on the cornice of the building. Cavalena was sitting on another balcony, and appeared to be lost in contemplation of the stars.

Suddenly, in a voice that seemed to come from a distance, almost from the sky, suffused with infinite pain, I heard him say:

“Sesè, do you see the Pleiads?”

She pretended to look: perhaps her eyes were filled with tears.

And her father:

“There they are… above your head… that little cluster of stars… do you see them?”

She nodded her head; yes, she saw them.

“Fine, aren’t they, Sesè? And do you see how bright Capella is?”

The stars… Poor Papa! A fine distraction. … And with one hand he straightened, stroked on his temples the curling locks of his artistic wig, while with the other… what? Why, yes … he was holding on his knee Piccini, his enemy, and was stroking her head…. Poor Papa! This must be one of his most tragic and pathetic moments!

There came from the Villa a long, slow slight rustle of leaves; from the deserted street an occasional sound of footsteps and the rapid clattering sound of a carriage driven in haste. The clang of the bell and the long-drawn whine of the trolley running along the electric wire of the tramway seemed to tear the street apart and fling it violently in its wake, with the houses and trees. Then all was silent, and in the weary calm returned the distant sound of a piano from one of the houses. It was a gentle, almost veiled, melancholy sound, which drew the spirit, fixed it at a definite point, as though to enable it to perceive how heavy was the cloak of sadness suspended over everything.

Ah, yes–Signorina Luisetta was perhaps thinking–marriage…. She was imagining, perhaps, that it was she who was playing, in a strange house, far away, that piano, to lull to sleep the pain of the sad, early memories which have poisoned her life for all time.

Will it be possible for her to illude herself? Will she be able to prevent from falling, withered, like the petals of flowers, on the silent air, chill with a want of confidence that is now perhaps insuperable, all the innocent graces that from time to time spring up in her soul?

I observe that she is spoiling herself, deliberately; she makes herself, every now and then, hard, bristling, so as not to appear tender and credulous. Perhaps she would like to be gay, frolicsome, as in more than one light moment of oblivion, when she has just risen from her bed, her eyes have suggested to her, from her mirror: those eyes of hers, which would so gladly laugh, keen and brilliant, and which she instead condemns to appear absent, or shy and sullen. Poor, lovely eyes! How often under her knitted brows does she not fix them on the empty air, while through her nostrils she breathes a long sigh in silence, as though she did not wish it to reach even her own ears! And how they cloud over and change colour, whenever she breathes one of those silent sighs.

Certainly she must have learned long ago to distrust her own impressions, perhaps in the fear lest she be gradually seized by the same malady as her mother. This is clearly shewn by her abrupt changes of expression, a sudden pallor following a sudden crimson flushing of her whole face, a smiling return to serenity after a fleeting cloud. Who knows how often, as she walks the streets with her father and mother, she must feel herself stabbed by every sound of laughter, and how often she must have the strange feeling that even that little blue frock, of Swiss silk, light as a feather, is weighing upon her like the habit of a cloistered nun and that the straw hat is crushing her head; and be tempted to tear off the blue silk, to wrench the straw from her head and tear it in pieces furiously with both hands and fling it… in her mother’s face? No… in her father’s, then? No… on the ground, on the ground, trampling it underfoot. Because it must seem to her a masquerade, an idiotic farce, to go about dressed like that, like a respectable person, like a young lady who is under the illusion that she is cutting a figure, or rather who lets it be seen that she has some beautiful dream in her mind, when presently at home, and even now in the street, everything that is most ugly, most brutal, most savage in life must be disclosed, must spring to light in those almost daily scenes between her parents, to smother her in misery and shame and disgrace.

And this reflexion more than any other seems to me to have profoundly penetrated her soul: that in the world, as her parents create it for themselves and round about her with their comic appearance, with the grotesque absurdity of that furious jealousy, with the disorder of their existence, there can be no room, air nor light for her charm. How can charm shew itself, breathe, refresh itself in a delicate, light and airy hue, in the midst of that ridicule which holds it down and stifles and obscures it?

She is like a butterfly cruelly fastened down with a pin, while still alive. She dares not beat her wings, not only because she has no hope of freeing herself, but also and even more because she might attract attention.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (26)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!