Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

3. Monday or Tuesday

(from: Monday or Tuesday)

Lazy and indifferent, shaking space easily from his wings, knowing his way, the heron passes over the church beneath the sky. White and distant, absorbed in itself, endlessly the sky covers and uncovers, moves and remains. A lake? Blot the shores of it out! A mountain? Oh, perfect — the sun gold on its slopes. Down that falls. Ferns then, or white feathers, for ever and ever —

Desiring truth, awaiting it, laboriously distilling a few words, for ever desiring —(a cry starts to the left, another to the right. Wheels strike divergently. Omnibuses conglomerate in conflict)— for ever desiring —(the clock asseverates with twelve distinct strokes that it is midday; light sheds gold scales; children swarm)— for ever desiring truth. Red is the dome; coins hang on the trees; smoke trails from the chimneys; bark, shout, cry “Iron for sale”— and truth?

Radiating to a point men’s feet and women’s feet, black or gold-encrusted —(This foggy weather — Sugar? No, thank you — The commonwealth of the future)— the firelight darting and making the room red, save for the black figures and their bright eyes, while outside a van discharges, Miss Thingummy drinks tea at her desk, and plate-glass preserves fur coats —

Flaunted, leaf — light, drifting at corners, blown across the wheels, silver-splashed, home or not home, gathered, scattered, squandered in separate scales, swept up, down, torn, sunk, assembled — and truth?

Now to recollect by the fireside on the white square of marble. From ivory depths words rising shed their blackness, blossom and penetrate. Fallen the book; in the flame, in the smoke, in the momentary sparks — or now voyaging, the marble square pendant, minarets beneath and the Indian seas, while space rushes blue and stars glint — truth? content with closeness?

Lazy and indifferent the heron returns; the sky veils her stars; then bares them.

Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf

3. Monday or Tuesday

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Monday or Tuesday, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

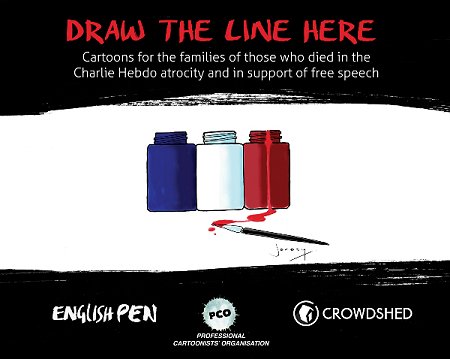

Draw the Line Here: Cartoonists respond to the Charlie Hebdo killings. Cartoons for the families of the victims of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, and in support of free speech.

English PEN is delighted to announce the publication of Draw The Line Here, a collection of cartoons drawn in response to the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris in January 2015.

The book is a collaboration between the Professional Cartoonists’ Organisation (PCO), Crowdshed, and English PEN. It features cartoons drawn by British artists in the days immediately after the attacks. The work of 66 cartoonists is featured, including Steve Bell, Dave Brown, Martin Rowson, Peter Brooke and Ralph Steadman.

Proceeds from the book will be split equally between the fund for the victims of the Charlie Hebdo murders, and English PEN’s Writers at Risk programme.

Proceeds from the book will be split equally between the fund for the victims of the Charlie Hebdo murders, and English PEN’s Writers at Risk programme.

Production of the book was made possible by a crowd-funding campaign launched in February. Over 200 people pledged their support to the project, and will be receiving their copies of the book in the coming days.

Draw The Line Here includes a foreword by Libby Purves, patron of the PCO, who writes:

Some cartoons here are gentle, others savage; some merely encapsulate the bafflement and sadness of a world where mockery is met not with the proper response, a shrug, but with murder. Again and again the theme is of the fragility of the sceptical, laughing pencil: its simplicity and its splendour, the opposite of the vainglorious, meaningless squalor of the gun and the bomb.

Jo Glanville, director of English PEN, said:

We are extremely grateful to the PCO and to Crowdshed for choosing English PEN as a beneficiary of this project, and of course to all the cartoonists who have contributed to the book. By exercising their own right to freedom of expression, these artists are helping to defend the free speech of others.

The publication of this book could not be more timely. Sunday 3 May is World Press Freedom Day, the perfect time to stand in solidarity with Charlie Hebdo.

Draw The Line Here may be purchased online at: www.englishpen.org/campaigns/draw-the-line-here

Supporters to the Crowdfunding campaign will receive their copies in the coming days

Books cost UK £15.00 each. UK delivery is £2.00 and international delivery is £4.00.

# More information on website English PEN

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Hoofdstuk 6

Hoofdstuk 6

Jacob Ramesz, de oude vlooientemmer,

stond meestal in gedachten verzonken in het deurgat

van zijn huis. Normaal was er nooit veel te doen op het plein. Dat

handjevol mensen, dat hij door en door kende, haalde zelden of nooit

iets uit waarvan zijn hart sneller ging kloppen. Alles was er altijd

precies hetzelfde. En als er eens wat te beleven viel, merkte je er

nog niet veel van. Op enkele uitzonderingen na, zoals die dronken

timmerman en Kaffa de dorpsgek, onderdrukte iedereen zijn gevoelens.

Het hoorde nu eenmaal niet om je bloot te geven.

Maar vandaag was het anders. De

lucht kraakte van de spanning, al vanaf het eerste gillen van de

jongen, zo vroeg in de ochtend. Dat lag niet aan de kraaien die zich

op het plein ophielden, want als de jongen niet op sterven had

gelegen, zouden ze er ook wel zijn geweest. Niet in het zwart maar in

hun daagse kleren, al maakte dat weinig verschil. Elke dag had het

troepje wijven ontstellend veel te vertellen. Dorpspraat. Oeverloos

gelul over de onnozelste zaken, waar je hoorndol van werd als je het

te lang aanhoorde. Wat Jacob Ramesz wel eens dwong zijn huis in te

vluchten. Met weemoed dacht Jacob terug aan vroeger. De jaren dat hij

nog wat voorstelde in Solde. Dit verdomde dorp was eigenlijk veel te

benauwd voor hem. Met dat ene café, zijn aardappelboeren en zijn

leger kraaien. Vroeger, dát waren nog eens tijden. Toen hij nog jong

was en elk jaar de hort op ging. Met zijn vlooientheater trok hij

door het hele land. Van het ene naar het andere feest. Kermissen en

oogstfeesten. Bruiloften en schuttersdagen. Alles deed hij aan met

zijn hele circus, dat hij op één arm kon zetten, alle dertig

tegelijk, om hen met zijn eigen bloed te voeden. Zelf gefokte dieren

waar andere vlooientemmers uit die tijd jaloers op waren. Tot

verdriet van Jacob stierf het vak uit. Maar wie herinnerde zich niet

zijn sterke trekhengst Fiffie? Ter grootte van een luciferkop, een

hele omvang voor een vlo, trok die in een tuigje van zijde een gouden

koetsje. Nou ja, goud. In elk geval trok hij een koetsje zo groot als

een pink rond een soepbord. Zo vaak je het maar hebben wilde. En dan

de ster van het gezelschap, Chocho, eigenlijk niet eens een

mensenvlo, die drie salto's sprong, waarvan één achterwaarts, over

een koffiekopje. Zijn hele leven had Ramesz voor niets anders gedeugd

dan voor het spel met de vlooien. Hij deed het nog steeds. In het

geniep. Hij wist dat de mensen hem licht van een plaag of ander

ongemak konden beschuldigen. In een doosje had hij enkele exemplaren

die hij 's avonds op opoes huid zette, om ze van haar bloed te laten

drinken. Het kindse mensje had het toch niet in de gaten.

De Jacob Ramesz die lang geleden

bekendstond als een sterk messenspeler, stond zich van woede op te

vreten over de vreemde afloop van het spelletje landverbeuren tussen

de slager en die gek. Het kwijl liep hem van ergernis uit de

mondhoeken. Die verrekte Kaffa maakte het kampioen zijn te schande

door zich zonder slag of stoot gewonnen te geven. Als een konijn was

hij door de slager afgemaakt en toch vertikte hij het om revanche te

nemen. Wat bezielde die vent? Zon niet eens op wraak! Liet alles maar

op zijn beloop. Leek nog te beroerd om de lijnen van de landen uit te

vegen. De schande van zijn verlies zou nog lang te zien zijn op het

plein. Azurri wachtte op wat Kaffa ging doen. In de verwachting dat

de ander toch nog een spelletje zou wagen om te proberen het verlies

goed te maken. Maar er kwam geen beweging in Kaffa. In tegenstelling

tot anders, wanneer hij zich hevig kon opwinden over de afloop van

een spel, werd hij nu koud noch warm van zijn verlies. Daar was de

slager blij mee. Durfde de ander niet te spelen, dan was hij

kampioen.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (35)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Kaffa begreep heel goed waar het de slager om te doen was. Hij zou kunnen weigeren tegen Azurri te spelen, maar achteraf zou de man het kunnen uitleggen als lafheid. Kaffa voelde zich niet in beste conditie. Zijn handen trilden.

Kaffa begreep heel goed waar het de slager om te doen was. Hij zou kunnen weigeren tegen Azurri te spelen, maar achteraf zou de man het kunnen uitleggen als lafheid. Kaffa voelde zich niet in beste conditie. Zijn handen trilden.

Het gebeuren met de waarzegger werkte op zijn zenuwen. Toch besloot hij de uitdaging aan te nemen. Met kracht gooide Kaffa het mes zo diep in het land van Azurri dat zelfs een deel van het heft in de grond drong. Hij sneed een stuk van het gebied van zijn tegenstander af. Worp na worp wist hij grote stukken land van de slager te veroveren. Het leek erop dat hij zou gaan winnen, zonder dat de slager ook maar één keer aan de beurt was geweest. Maar het land van de slager werd zo klein dat Kaffa’s laatste worp ernaast ging. Het mes viel buiten de grenzen. Kaffa was af. Hij trok het mes uit de grond en wierp het naar de slager, die het handig opving, gewend als hij was met messen om te gaan. Om te zien of het scherp genoeg voor hem was, zette de slager het op zijn arm en schoor een baan haren af. Spuwde op het lemmet en wreef het droog op de rug van zijn hand. Hij gooide het mes in Kaffa’s land en won in één keer het grootste deel van diens gebied. Voor zijn volgende worp bekeek Azurri het mes opnieuw, spuwde op het lemmet en mikte. Het vochtige mes schoot iets te vroeg uit zijn hand en sloeg met een knal tegen de stam van de meidoorn. Het lemmet knapte af, het mes schoot als een boemerang naar de slager terug en schoof in zijn voet. Kaffa vloekte. Hij raapte het heft op en woog het in zijn hand. Zijn beste mes was nu waardeloos. Hij wilde Azurri’s schoen losmaken, maar voelde dat het trillen van zijn linkerhand door zijn hele lichaam kroop. Azurri’s vrouw kwam toelopen. Ze hielp haar man met het uittrekken van zijn schoen. Het bloed stroomde uit de voet en bleef als een korst op het droge zand achter. De vrouw bekeek de wonde, maar dat maakte haar niet veel wijzer. Ze goot er jenever over, om infectie te voorkomen. Om het bloed sneller te doen stollen, legde ze er een zakje gedroogde kruiden op en verbond de wond. Het gezicht van de slager was van pijn vertrokken. Om zijn voet niet te zien keek hij naar de bakfiets vol varkens, die naast de spoelbak stond. Nu hij kennis had gemaakt met de scherpte van een mes, zou hij moeten begrijpen hoe vreselijk het lot van de varkens was. Maar waarschijnlijk had zijn beroep hem te zeer afgestompt om dat gevoel op te brengen. Door alle drukte was Kaffa nogal van streek. Hij borg de resten van het mes in de dekenzak, die in de meidoorn hing, haalde een nieuw mes tevoorschijn en veegde de lijnen van de landen uit om het spel opnieuw te beginnen.

Met de punt van het nieuwe mes tekende hij eerst de as die de grens van de twee landen was, daarna de cirkel zelf. Ondanks de pijn nam Azurri het mes van Kaffa aan en gooide. Hij kon slechts een klein deel van het land van Kaffa winnen voordat zijn mes plat viel. Daarna was de beurt aan Kaffa. Hij voelde dat het mes in zijn handen talmde. Zijn hand trilde heftig. Hij móést gooien. Hij probeerde zuiver te mikken. Het mes viel languit neer. Azurri lachte. Met de volgende worpen wist hij zoveel van Kaffa te winnen dat die geen land meer had om er zijn koning in kwijt te kunnen. Kaffa begreep dat hij met dit verlies een stuk van het aanzien verloor dat hij, kampioen, had opgebouwd. Hij kon het zich niet permitteren verslagen te worden. Bij elk verder verlies zou hij een deel van zijn greep op het plein kwijtraken. Hij zou er de enige reden voor zijn aanwezigheid in het dorp door verliezen. De koning van het plein wankelde.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (34)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

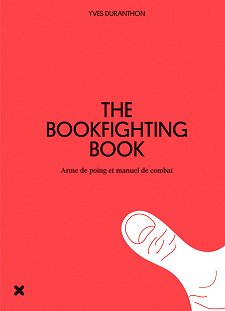

Le bookfighting est un sport de combat : deux adversaires (protégés), s’affrontent avec des livres (de poche!), sous le contrôle d’un arbitre. Chaque touche vaut un point dans une partie en sept jeux. Point fort du règlement : la possibilité à tout moment d’ouvrir un livre, sa lecture, pour soi ou à voix haute, ayant pour effet immédiat d’interrompre le combat. La véhémence initiale cède ainsi à l’autorité du livre, le combat-lecture instaurant un indécidable aller-retour entre deux états connus et opposés, nature et culture. Au terme du combat, l’arbitre annonce le résultat et désigne le vainqueur sous les applaudissements du public, convié à participer s’il le désire.

Le bookfighting est un sport de combat : deux adversaires (protégés), s’affrontent avec des livres (de poche!), sous le contrôle d’un arbitre. Chaque touche vaut un point dans une partie en sept jeux. Point fort du règlement : la possibilité à tout moment d’ouvrir un livre, sa lecture, pour soi ou à voix haute, ayant pour effet immédiat d’interrompre le combat. La véhémence initiale cède ainsi à l’autorité du livre, le combat-lecture instaurant un indécidable aller-retour entre deux états connus et opposés, nature et culture. Au terme du combat, l’arbitre annonce le résultat et désigne le vainqueur sous les applaudissements du public, convié à participer s’il le désire.

Bookfighting Performance Yves Duranthon

Date: 07/05/2015 – 18:00

MUSEE PALAIS DE TOKYO

13, avenue du Président Wilson,

75 116 Paris

Bookfighting: Men, women, and children fighting with books. The show is captivating and you can not manage to turn a blind eye to these objects being handled in such a manner. Is this the way to treat culture and the great minds of our civilization? It’s outrageous and you want to react, but you keep it inside, because you don’t know how to release your anger.

Bookfighting: Men, women, and children fighting with books. The show is captivating and you can not manage to turn a blind eye to these objects being handled in such a manner. Is this the way to treat culture and the great minds of our civilization? It’s outrageous and you want to react, but you keep it inside, because you don’t know how to release your anger.

The show goes on, regardless of your uneasiness and good judgment, and eventually you succumb to the spectacle. You are fascinated by the disturbing yet beautiful event of fighters energetically chucking books at each other.

You come back later, armed with books taken from your own library, and get involved in the fighting yourself so that you can discover the flip side of culture.

# Website Palais de Tokyo

Bookfighting Performance Yves Duranthon

# Website Yves Duranthon bookfighting performance

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, Libraries in Literature, Performing arts, The Art of Reading, THEATRE

Het even verguisde als bewierookte enfant terrible van de Franse letteren: Michel Houellebecq treedt zaterdag 16 mei op tijdens City2Cities 2015! Met zijn vertaler Martin de Haan spreekt Houellebecq over zijn nieuwe boek Onderworpen (Soumission) waarin een moslim in 2022 president wordt van Frankrijk. Het boek veroorzaakte al voor verschijnen ophef, die alleen nog maar werd aangewakkerd door de aanslag op Charlie Hebdo in Parijs.

Het even verguisde als bewierookte enfant terrible van de Franse letteren: Michel Houellebecq treedt zaterdag 16 mei op tijdens City2Cities 2015! Met zijn vertaler Martin de Haan spreekt Houellebecq over zijn nieuwe boek Onderworpen (Soumission) waarin een moslim in 2022 president wordt van Frankrijk. Het boek veroorzaakte al voor verschijnen ophef, die alleen nog maar werd aangewakkerd door de aanslag op Charlie Hebdo in Parijs.

Michel Houellebecq debuteerde begin jaren negentig als dichter, maar brak in 1998 door met de roman Elementaire deeltjes. Met dat boek en later nogmaals met Mogelijkheid van een eiland greep hij net naast de belangrijkste Franse literatuurprijs. In 2010 ontving hij de Prix Goncourt wel, voor De kaart en het gebied. In 2011 ‘verdween’ Houellebecq vlak voor een promotietournee door Nederland en België. Bijna een week later dook hij weer op, met als excuus dat hij de tour vergeten was. Nooit werd helemaal duidelijk wat de werkelijke reden was om niets van zich te laten horen. Begin dit jaar ging de film The kidnapping of Michel Houellebecq in première. In deze komische nep-documentaire wordt uit de doeken gedaan waarom hij destijds zo onverwacht verdween.

Onderworpen (De Arbeiderspers), de zesde roman van Michel Houellebecq, speelt zich af in het Frankrijk van 2022. Bij de presidentverkiezingen kiest het land voor het eerst in de geschiedenis voor een islamitische president. Om het Front National van een verkiezingsoverwinning af te houden, steunen de linkse en rechtse partijen de populaire en charismatische Mohammed Ben Abbes. Op die manier krijgt Frankrijk een moslimpresident, ondanks dat nog altijd een grote meerderheid van de bevolking niet islamitisch is. De bevolking gaat al snel wat merken van de macht van de moslims: vrouwen moeten hoofddoekjes dragen en minirokjes verdwijnen uit het straatbeeld. De hoofdpersoon in de roman, de 44-jarige universitair docent Francois, ziet zijn land steeds verder polariseren.

Onderworpen (De Arbeiderspers), de zesde roman van Michel Houellebecq, speelt zich af in het Frankrijk van 2022. Bij de presidentverkiezingen kiest het land voor het eerst in de geschiedenis voor een islamitische president. Om het Front National van een verkiezingsoverwinning af te houden, steunen de linkse en rechtse partijen de populaire en charismatische Mohammed Ben Abbes. Op die manier krijgt Frankrijk een moslimpresident, ondanks dat nog altijd een grote meerderheid van de bevolking niet islamitisch is. De bevolking gaat al snel wat merken van de macht van de moslims: vrouwen moeten hoofddoekjes dragen en minirokjes verdwijnen uit het straatbeeld. De hoofdpersoon in de roman, de 44-jarige universitair docent Francois, ziet zijn land steeds verder polariseren.

Over Michel Houellebecq: Michel Houellebecq (1958) is Frankrijks onbetwiste sterschrijver van dit moment. Hij publiceerde essays en poëzie voordat hij zich in 1994 met de roman De wereld als markt en strijd opwierp als belofte van de Franse letteren. Die status bevestigde hij met Elementaire deeltjes , dat hem terecht de faam van groot schrijver bezorgde, en Platform. In 2011 verscheen zijn grote nieuwe roman De kaart en het gebied. Zijn veelvuldig bekroonde en wereldwijd vertaalde werk is naar het Nederlands vertaald door Martin de Haan.

Over Martin de Haan: Martin de Haan (Middelburg, 1966) werkte na zijn studies Frans en literatuurwetenschap enkele jaren aan een proefschrift over de poëzie van Raymond Queneau, maar zei in 1995 de wetenschap vaarwel om zelf literair actief te worden. Hij was lange tijd recensent Franse literatuur voor de Volkskrant en schreef essays voor diverse Nederlandse en Vlaamse tijdschriften. Martin de Haan is de vaste vertaler van o.a. Milan Kundera en Michel Houellebecq.

City2Cities 2015 – Met Michel Houellebecq, Michel Faber e.v.a. op 15 & 16 mei 2015

City2Cities 2015 – Met Michel Houellebecq, Michel Faber e.v.a. op 15 & 16 mei 2015

Twee avonden vult het Postkantoor Neude zich met internationale literatuur. Onder de bogen van de indrukwekkende hal – waar men vroeger in de rij stond voor postzegels en briefkaarten – klinkt twee dagen proza, poëzie en muziek. Net als voorgaande jaren gaat ook deze editie bijzondere aandacht uit naar de literatuur uit twee wereldsteden. Dit jaar zijn dat Krakau en Parijs.

City2Cities 2015 – Vrijdagavond 15 mei – Met Eleanor Catton, Jens Christian Grøndahl e.v.a. – Postkantoor Neude, Utrecht, programma:

– Eleanor Catton over haar met de Man Booker Prize bekroonde roman Al wat schittert.

– De grote Deense schrijver Jens Christian Grøndahl (Portret van een man) in gesprek met de Nederlandse romancier Stephan Enter.

– Marie Darrieussecq (Zeugzoenen & Je moet veel van mannen houden), een van de origineelste en opmerkelijkste Franse schrijvers, in gesprek met Niña Weijers.

– Olga Tokarczuk (De rustelozen), een van de meest bejubelde én best verkopende Poolse schrijvers van dit moment, in gesprek met de Vlaamse Annelies Verbeke, schrijver van o.a. Slaap! en Dertig dagen.

– Karol Lesman en Olga Tokarczuk over dé Poolse literaire klassieker: De pop (1890) van Bolesław Prus.

– Jo Govaerts, Sławomir Shuty en anderen over literair Krakau.

– Alle genomineerden voor de C.C.S. Crone Stipendia 2015.

Met zaterdag 16 mei 19:30 – Postkantoor Neude, Utrecht, op het programma:

– MICHEL HOUELLEBECQ in gesprek met zijn vertaler Martin de Haan over Onderworpen (Soumission).

– MICHEL FABER over zijn nieuwste en laatste roman Het boek van wonderlijke nieuwe dingen.

– JAN SIEBELINK over Parijs

– Rokus Hofstede & Martin de Haan over MARCEL PROUST

– Alle genomineerden voor de FILTER VERTAALPRIJS.

– Writer in Residence THOMAS CLERC

– ŁUKASZ KOTERBA en VROUWKJE TUINMAN over het Polenhotel

– RUBEN VAN GOGH over zijn Parijse roots

# Meer informatie website City2Cities

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Michel Houellebecq, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE

Speciaal themanummer Literair tijdschrift Extaze tijdens het Kellendonk-jaar 2015

Speciaal themanummer Literair tijdschrift Extaze tijdens het Kellendonk-jaar 2015

Ook dit jaar maakt Literair Tijdschrift Extaze weer een bijzonder themanummer. Vijfentwintig jaar geleden is de Nederlandse schrijver Frans Kellendonk overleden, voor Extaze reden om een apart nummer over zijn leven en schrijverschap te plannen. Begin april is een crowdfundingactie gestart via website: www.voordekunst.nl

Het Kellendonk-nummer, zoals dat de redactie van Extaze voor ogen staat, kan niet met de eigen bescheiden middelen gefinancierd worden. De kosten voor het onderzoek, de uitwerking van de stukken, het beeldend werk (waarvoor een gerichte opdracht is gegeven aan Rens Krikhaar, een beeldend kunstenaar te Den Haag wiens stijl verwantschap toont met het werk van Kellendonk), de speciale vormgeving, net als het beeldend werk aangepast aan het onderwerp, de extra drukkosten die de bijzondere vormgeving en het extra aantal pagina’s met zich meebrengen en de ‘anders dan andere’ presentatie, waarvoor sprekers en podiumartiesten gerichte opdrachten krijgen, noodzaken de redactie een beroep op u te doen.

# Meer informatie over Frans Kellendonk op website Kellendonk-fonds

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Frans Kellendonk, LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

2. A Society

(from: Monday or Tuesday)

This is how it all came about. Six or seven of us were sitting one day after tea. Some were gazing across the street into the windows of a milliner’s shop where the light still shone brightly upon scarlet feathers and golden slippers. Others were idly occupied in building little towers of sugar upon the edge of the tea tray.

After a time, so far as I can remember, we drew round the fire and began as usual to praise men — how strong, how noble, how brilliant, how courageous, how beautiful they were — how we envied those who by hook or by crook managed to get attached to one for life — when Poll, who had said nothing, burst into tears. Poll, I must tell you, has always been queer. For one thing her father was a strange man. He left her a fortune in his will, but on condition that she read all the books in the London Library. We comforted her as best we could; but we knew in our hearts how vain it was. For though we like her, Poll is no beauty; leaves her shoe laces untied; and must have been thinking, while we praised men, that not one of them would ever wish to marry her. At last she dried her tears. For some time we could make nothing of what she said. Strange enough it was in all conscience. She told us that, as we knew, she spent most of her time in the London Library, reading. She had begun, she said, with English literature on the top floor; and was steadily working her way down to the Times on the bottom. And now half, or perhaps only a quarter, way through a terrible thing had happened. She could read no more. Books were not what we thought them. “Books,” she cried, rising to her feet and speaking with an intensity of desolation which I shall never forget, “are for the most part unutterably bad!”

Of course we cried out that Shakespeare wrote books, and Milton and Shelley.

“Oh, yes,” she interrupted us. “You’ve been well taught, I can see. But you are not members of the London Library.” Here her sobs broke forth anew. At length, recovering a little, she opened one of the pile of books which she always carried about with her —“From a Window” or “In a Garden,” or some such name as that it was called, and it was written by a man called Benton or Henson, or something of that kind. She read the first few pages. We listened in silence. “But that’s not a book,” someone said. So she chose another. This time it was a history, but I have forgotten the writer’s name. Our trepidation increased as she went on. Not a word of it seemed to be true, and the style in which it was written was execrable.

“Poetry! Poetry!” we cried, impatiently.

“Read us poetry!” I cannot describe the desolation which fell upon us as she opened a little volume and mouthed out the verbose, sentimental foolery which it contained.

“It must have been written by a woman,” one of us urged. But no. She told us that it was written by a young man, one of the most famous poets of the day. I leave you to imagine what the shock of the discovery was. Though we all cried and begged her to read no more, she persisted and read us extracts from the Lives of the Lord Chancellors. When she had finished, Jane, the eldest and wisest of us, rose to her feet and said that she for one was not convinced.

“Why,” she asked, “if men write such rubbish as this, should our mothers have wasted their youth in bringing them into the world?”

We were all silent; and, in the silence, poor Poll could be heard sobbing out, “Why, why did my father teach me to read?”

Clorinda was the first to come to her senses. “It’s all our fault,” she said. “Every one of us knows how to read. But no one, save Poll, has ever taken the trouble to do it. I, for one, have taken it for granted that it was a woman’s duty to spend her youth in bearing children. I venerated my mother for bearing ten; still more my grandmother for bearing fifteen; it was, I confess, my own ambition to bear twenty. We have gone on all these ages supposing that men were equally industrious, and that their works were of equal merit. While we have borne the children, they, we supposed, have borne the books and the pictures. We have populated the world. They have civilized it. But now that we can read, what prevents us from judging the results? Before we bring another child into the world we must swear that we will find out what the world is like.”

So we made ourselves into a society for asking questions. One of us was to visit a man-of-war; another was to hide herself in a scholar’s study; another was to attend a meeting of business men; while all were to read books, look at pictures, go to concerts, keep our eyes open in the streets, and ask questions perpetually. We were very young. You can judge of our simplicity when I tell you that before parting that night we agreed that the objects of life were to produce good people and good books. Our questions were to be directed to finding out how far these objects were now attained by men. We vowed solemnly that we would not bear a single child until we were satisfied.

Off we went then, some to the British Museum; others to the King’s Navy; some to Oxford; others to Cambridge; we visited the Royal Academy and the Tate; heard modern music in concert rooms, went to the Law Courts, and saw new plays. No one dined out without asking her partner certain questions and carefully noting his replies. At intervals we met together and compared our observations. Oh, those were merry meeting! Never have I laughed so much as I did when Rose read her notes upon “Honour” and described how she had dressed herself as an Ethiopian Prince and gone aboard one of His Majesty’s ships. Discovering the hoax, the Captain visited her (now disguised as a private gentleman) and demanded that honour should be satisfied. “But how?” she asked. “How?” he bellowed. “With the cane of course!” Seeing that he was beside himself with rage and expecting that her last moment had come, she bent over and received, to her amazement, six light taps upon the behind. “The honour of the British Navy is avenged!” he cried, and, raising herself, she saw him with the sweat pouring down his face holding out a trembling right hand. “Away!” she exclaimed, striking an attitude and imitating the ferocity of his own expression, “My honour has still to be satisfied!” “Spoken like a gentleman!” he returned, and fell into profound thought. “If six strokes avenge the honour of the King’s Navy,” he mused, “how many avenge the honour of a private gentleman?” He said he would prefer to lay the case before his brother officers. She replied haughtily that she could not wait. He praised her sensibility. “Let me see,” he cried suddenly, “did your father keep a carriage?” “No,” she said. “Or a riding horse?” “We had a donkey,” she bethought her, “which drew the mowing machine.” At this his face lighted. “My mother’s name —” she added. “For God’s sake, man, don’t mention your mother’s name!” he shrieked, trembling like an aspen and flushing to the roots of his hair, and it was ten minutes at least before she could induce him to proceed. At length he decreed that if she gave him four strokes and a half in the small of the back at a spot indicated by himself (the half conceded, he said, in recognition of the fact that her great grandmother’s uncle was killed at Trafalgar) it was his opinion that her honour would be as good as new. This was done; they retired to a restaurant; drank two bottles of wine for which he insisted upon paying; and parted with protestations of eternal friendship.

Then we had Fanny’s account of her visit to the Law Courts. At her first visit she had come to the conclusion that the Judges were either made of wood or were impersonated by large animals resembling man who had been trained to move with extreme dignity, mumble and nod their heads. To test her theory she had liberated a handkerchief of bluebottles at the critical moment of a trial, but was unable to judge whether the creatures gave signs of humanity for the buzzing of the flies induced so sound a sleep that she only woke in time to see the prisoners led into the cells below. But from the evidence she brought we voted that it is unfair to suppose that the Judges are men.

Helen went to the Royal Academy, but when asked to deliver her report upon the pictures she began to recite from a pale blue volume, “O! for the touch of a vanished hand and the sound of a voice that is still. Home is the hunter, home from the hill. He gave his bridle reins a shake. Love is sweet, love is brief. Spring, the fair spring, is the year’s pleasant King. O! to be in England now that April’s there. Men must work and women must weep. The path of duty is the way to glory —” We could listen to no more of this gibberish.

“We want no more poetry!” we cried.

“Daughters of England!” she began, but here we pulled her down, a vase of water getting spilt over her in the scuffle.

“Thank God!” she exclaimed, shaking herself like a dog. “Now I’ll roll on the carpet and see if I can’t brush off what remains of the Union Jack. Then perhaps —” here she rolled energetically. Getting up she began to explain to us what modern pictures are like when Castalia stopped her.

“What is the average size of a picture?” she asked. “Perhaps two feet by two and a half,” she said. Castalia made notes while Helen spoke, and when she had done, and we were trying not to meet each other’s eyes, rose and said, “At your wish I spent last week at Oxbridge, disguised as a charwoman. I thus had access to the rooms of several Professors and will now attempt to give you some idea — only,” she broke off, “I can’t think how to do it. It’s all so queer. These Professors,” she went on, “live in large houses built round grass plots each in a kind of cell by himself. Yet they have every convenience and comfort. You have only to press a button or light a little lamp. Theirs papers are beautifully filed. Books abound. There are no children or animals, save half a dozen stray cats and one aged bullfinch — a cock. I remember,” she broke off, “an Aunt of mine who lived at Dulwich and kept cactuses. You reached the conservatory through the double drawing-room, and there, on the hot pipes, were dozens of them, ugly, squat, bristly little plants each in a separate pot. Once in a hundred years the Aloe flowered, so my Aunt said. But she died before that happened —” We told her to keep to the point. “Well,” she resumed, “when Professor Hobkin was out, I examined his life work, an edition of Sappho. It’s a queer looking book, six or seven inches thick, not all by Sappho. Oh, no. Most of it is a defence of Sappho’s chastity, which some German had denied, add I can assure you the passion with which these two gentlemen argued, the learning they displayed, the prodigious ingenuity with which they disputed the use of some implement which looked to me for all the world like a hairpin astounded me; especially when the door opened and Professor Hobkin himself appeared. A very nice, mild, old gentleman, but what could he know about chastity?” We misunderstood her.

“No, no,” she protested, “he’s the soul of honour I’m sure — not that he resembled Rose’s sea captain in the least. I was thinking rather of my Aunt’s cactuses. What could they know about chastity?”

Again we told her not to wander from the point — did the Oxbridge professors help to produce good people and good books? — the objects of life.

“There!” she exclaimed. “It never struck me to ask. It never occurred to me that they could possibly produce anything.”

“I believe,” said Sue, “that you made some mistake. Probably Professor Hobkin was a gynecologist. A scholar is a very different sort of man. A scholar is overflowing with humour and invention — perhaps addicted to wine, but what of that? — a delightful companion, generous, subtle, imaginative — as stands to reason. For he spends his life in company with the finest human beings that have ever existed.”

“Hum,” said Castalia. “Perhaps I’d better go back and try again.”

Some three months later it happened that I was sitting alone when Castalia entered. I don’t know what it was in the look of her that so moved me; but I could not restrain myself, and, dashing across the room, I clasped her in my arms. Not only was she very beautiful; she seemed also in the highest spirits. “How happy you look!” I exclaimed, as she sat down.

“I’ve been at Oxbridge,” she said.

“Asking questions?”

“Answering them,” she replied.

“You have not broken our vows?” I said anxiously, noticing something about her figure.

“Oh, the vow,” she said casually. “I’m going to have a baby, if that’s what you mean. You can’t imagine,” she burst out, “how exciting, how beautiful, how satisfying —”

“What is?” I asked.

“To — to — answer questions,” she replied in some confusion. Whereupon she told me the whole of her story. But in the middle of an account which interested and excited me more than anything I had ever heard, she gave the strangest cry, half whoop, half holloa —

“Chastity! Chastity! Where’s my chastity!” she cried. “Help Ho! The scent bottle!”

There was nothing in the room but a cruet containing mustard, which I was about to administer when she recovered her composure.

“You should have thought of that three months ago,” I said severely.

“True,” she replied. “There’s not much good in thinking of it now. It was unfortunate, by the way, that my mother had me called Castalia.”

“Oh, Castalia, your mother —” I was beginning when she reached for the mustard pot.

“No, no, no,” she said, shaking her head. “If you’d been a chaste woman yourself you would have screamed at the sight of me — instead of which you rushed across the room and took me in your arms. No, Cassandra. We are neither of us chaste.” So we went on talking.

Meanwhile the room was filling up, for it was the day appointed to discuss the results of our observations. Everyone, I thought, felt as I did about Castalia. They kissed her and said how glad they were to see her again. At length, when we were all assembled, Jane rose and said that it was time to begin. She began by saying that we had now asked questions for over five years, and that though the results were bound to be inconclusive — here Castalia nudged me and whispered that she was not so sure about that. Then she got up, and, interrupting Jane in the middle of a sentence, said:

“Before you say any more, I want to know — am I to stay in the room? Because,” she added, “I have to confess that I am an impure woman.”

Everyone looked at her in astonishment.

“You are going to have a baby?” asked Jane.

She nodded her head.

It was extraordinary to see the different expressions on their faces. A sort of hum went through the room, in which I could catch the words “impure,” “baby,” “Castalia,” and so on. Jane, who was herself considerably moved, put it to us:

“Shall she go? Is she impure?”

Such a roar filled the room as might have been heard in the street outside.

“No! No! No! Let her stay! Impure? Fiddlesticks!” Yet I fancied that some of the youngest, girls of nineteen or twenty, held back as if overcome with shyness. Then we all came about her and began asking questions, and at last I saw one of the youngest, who had kept in the background, approach shyly and say to her:

“What is chastity then? I mean is it good, or is it bad, or is it nothing at all?” She replied so low that I could not catch what she said.

“You know I was shocked,” said another, “for at least ten minutes.”

“In my opinion,” said Poll, who was growing crusty from always reading in the London Library, “chastity is nothing but ignorance — a most discreditable state of mind. We should admit only the unchaste to our society. I vote that Castalia shall be our President.”

This was violently disputed.

“It is as unfair to brand women with chastity as with unchastity,” said Poll. “Some of us haven’t the opportunity either. Moreover, I don’t believe Cassy herself maintains that she acted as she did from a pure love of knowledge.”

“He is only twenty-one and divinely beautiful,” said Cassy, with a ravishing gesture.

“I move,” said Helen, “that no one be allowed to talk of chastity or unchastity save those who are in love.”

“Oh, bother,” said Judith, who had been enquiring into scientific matters, “I’m not in love and I’m longing to explain my measures for dispensing with prostitutes and fertilizing virgins by Act of Parliament.”

She went on to tell us of an invention of hers to be erected at Tube stations and other public resorts, which, upon payment of a small fee, would safeguard the nation’s health, accommodate its sons, and relieve its daughters. Then she had contrived a method of preserving in sealed tubes the germs of future Lord Chancellors “or poets or painters or musicians,” she went on, “supposing, that is to say, that these breeds are not extinct, and that women still wish to bear children —”

“Of course we wish to bear children!” cried Castalia, impatiently. Jane rapped the table.

“That is the very point we are met to consider,” she said. “For five years we have been trying to find out whether we are justified in continuing the human race. Castalia has anticipated our decision. But it remains for the rest of us to make up our minds.”

Here one after another of our messengers rose and delivered their reports. The marvels of civilisation far exceeded our expectations, and, as we learnt for the first time how man flies in the air, talks across space, penetrates to the heart of an atom, and embraces the universe in his speculations, a murmur of admiration burst from our lips.

“We are proud,” we cried, “that our mothers sacrificed their youth in such a cause as this!” Castalia, who had been listening intently, looked prouder than all the rest. Then Jane reminded us that we had still much to learn, and Castalia begged us to make haste. On we went through a vast tangle of statistics. We learnt that England has a population of so many millions, and that such and such a proportion of them is constantly hungry and in prison; that the average size of a working man’s family is such, and that so great a percentage of women die from maladies incident to childbirth. Reports were read of visits to factories, shops, slums, and dockyards. Descriptions were given of the Stock Exchange, of a gigantic house of business in the City, and of a Government Office. The British Colonies were now discussed, and some account was given of our rule in India, Africa and Ireland. I was sitting by Castalia and I noticed her uneasiness.

“We shall never come to any conclusion at all at this rate,” she said. “As it appears that civilisation is so much more complex than we had any notion, would it not be better to confine ourselves to our original enquiry? We agreed that it was the object of life to produce good people and good books. All this time we have been talking of aeroplanes, factories, and money. Let us talk about men themselves and their arts, for that is the heart of the matter.”

So the diners out stepped forward with long slips of paper containing answers to their questions. These had been framed after much consideration. A good man, we had agreed, must at any rate be honest, passionate, and unworldly. But whether or not a particular man possessed those qualities could only be discovered by asking questions, often beginning at a remote distance from the centre. Is Kensington a nice place to live in? Where is your son being educated — and your daughter? Now please tell me, what do you pay for your cigars? By the way, is Sir Joseph a baronet or only a knight? Often it seemed that we learnt more from trivial questions of this kind than from more direct ones. “I accepted my peerage,” said Lord Bunkum, “because my wife wished it.” I forget how many titles were accepted for the same reason. “Working fifteen hours out of the twenty-four, as I do —” ten thousand professional men began.

“No, no, of course you can neither read nor write. But why do you work so hard?” “My dear lady, with a growing family —” “But why does your family grow?” Their wives wished that too, or perhaps it was the British Empire. But more significant than the answers were the refusals to answer. Very few would reply at all to questions about morality and religion, and such answers as were given were not serious. Questions as to the value of money and power were almost invariably brushed aside, or pressed at extreme risk to the asker. “I’m sure,” said Jill, “that if Sir Harley Tightboots hadn’t been carving the mutton when I asked him about the capitalist system he would have cut my throat. The only reason why we escaped with our lives over and over again is that men are at once so hungry and so chivalrous. They despise us too much to mind what we say.”

“Of course they despise us,” said Eleanor. “At the same time how do you account for this — I made enquiries among the artists. Now, no woman has ever been an artist, has she, Polls?”

“Jane — Austen — Charlotte — Bronte — George — Eliot,” cried Poll, like a man crying muffins in a back street.

“Damn the woman!” someone exclaimed. “What a bore she is!”

“Since Sappho there has been no female of first rate —” Eleanor began, quoting from a weekly newspaper.

“It’s now well known that Sappho was the somewhat lewd invention of Professor Hobkin,” Ruth interrupted.

“Anyhow, there is no reason to suppose that any woman ever has been able to write or ever will be able to write,” Eleanor continued. “And yet, whenever I go among authors they never cease to talk to me about their books. Masterly! I say, or Shakespeare himself! (for one must say something) and I assure you, they believe me.”

“That proves nothing,” said Jane. “They all do it. Only,” she sighed, “it doesn’t seem to help us much. Perhaps we had better examine modern literature next. Liz, it’s your turn.”

Elizabeth rose and said that in order to prosecute her enquiry she had dressed as a man and been taken for a reviewer.

“I have read new books pretty steadily for the past five years,” said she. “Mr. Wells is the most popular living writer; then comes Mr. Arnold Bennett; then Mr. Compton Makenzie; Mr. McKenna and Mr. Walpole may be bracketed together.” She sat down.

“But you’ve told us nothing!” we expostulated. “Or do you mean that these gentlemen have greatly surpassed Jane-Elliot and that English fiction is — where’s that review of yours? Oh, yes, ‘safe in their hands.’”

“Safe, quite safe,” she said, shifting uneasily from foot to foot. “And I’m sure that they give away even more than they receive.”

We were all sure of that. “But,” we pressed her, “do they write good books?”

“Good books?” she said, looking at the ceiling “You must remember,” she began, speaking with extreme rapidity, “that fiction is the mirror of life. And you can’t deny that education is of the highest importance, and that it would be extremely annoying, if you found yourself alone at Brighton late at night, not to know which was the best boarding house to stay at, and suppose it was a dripping Sunday evening — wouldn’t it be nice to go to the Movies?”

“But what has that got to do with it?” we asked.

“Nothing — nothing — nothing whatever,” she replied.

“Well, tell us the truth,” we bade her.

“The truth? But isn’t it wonderful,” she broke off —“Mr. Chitter has written a weekly article for the past thirty years upon love or hot buttered toast and has sent all his sons to Eton —”

“The truth!” we demanded.

“Oh, the truth,” she stammered, “the truth has nothing to do with literature,” and sitting down she refused to say another word.

It all seemed to us very inconclusive.

“Ladies, we must try to sum up the results,” Jane was beginning, when a hum, which had been heard for some time through the open window, drowned her voice.

“War! War! War! Declaration of War!” men were shouting in the street below.

We looked at each other in horror.

“What war?” we cried. “What war?” We remembered, too late, that we had never thought of sending anyone to the House of Commons. We had forgotten all about it. We turned to Poll, who had reached the history shelves in the London Library, and asked her to enlighten us.

“Why,” we cried, “do men go to war?”

“Sometimes for one reason, sometimes for another,” she replied calmly. “In 1760, for example —” The shouts outside drowned her words. “Again in 1797 — in 1804 — It was the Austrians in 1866-1870 was the Franco-Prussian — In 1900 on the other hand —”

“But it’s now 1914!” we cut her short.

“Ah, I don’t know what they’re going to war for now,” she admitted.

* * * *

The war was over and peace was in process of being signed, when I once more found myself with Castalia in the room where our meetings used to be held. We began idly turning over the pages of our old minute books. “Queer,” I mused, “to see what we were thinking five years ago.” “We are agreed,” Castalia quoted, reading over my shoulder, “that it is the object of life to produce good people and good books.” We made no comment upon that. “A good man is at any rate honest, passionate and unworldly.” “What a woman’s language!” I observed. “Oh, dear,” cried Castalia, pushing the book away from her, “what fools we were! It was all Poll’s father’s fault,” she went on. “I believe he did it on purpose — that ridiculous will, I mean, forcing Poll to read all the books in the London Library. If we hadn’t learnt to read,” she said bitterly, “we might still have been bearing children in ignorance and that I believe was the happiest life after all. I know what you’re going to say about war,” she checked me, “and the horror of bearing children to see them killed, but our mothers did it, and their mothers, and their mothers before them. And they didn’t complain. They couldn’t read. I’ve done my best,” she sighed, “to prevent my little girl from learning to read, but what’s the use? I caught Ann only yesterday with a newspaper in her hand and she was beginning to ask me if it was ‘true.’ Next she’ll ask me whether Mr. Lloyd George is a good man, then whether Mr. Arnold Bennett is a good novelist, and finally whether I believe in God. How can I bring my daughter up to believe in nothing?” she demanded.

“Surely you could teach her to believe that a man’s intellect is, and always will be, fundamentally superior to a woman’s?” I suggested. She brightened at this and began to turn over our old minutes again. “Yes,” she said, “think of their discoveries, their mathematics, their science, their philosophy, their scholarship —” and then she began to laugh, “I shall never forget old Hobkin and the hairpin,” she said, and went on reading and laughing and I thought she was quite happy, when suddenly she drew the book from her and burst out, “Oh, Cassandra, why do you torment me? Don’t you know that our belief in man’s intellect is the greatest fallacy of them all?” “What?” I exclaimed. “Ask any journalist, schoolmaster, politician or public house keeper in the land and they will all tell you that men are much cleverer than women.” “As if I doubted it,” she said scornfully. “How could they help it? Haven’t we bred them and fed and kept them in comfort since the beginning of time so that they may be clever even if they’re nothing else? It’s all our doing!” she cried. “We insisted upon having intellect and now we’ve got it. And it’s intellect,” she continued, “that’s at the bottom of it. What could be more charming than a boy before he has begun to cultivate his intellect? He is beautiful to look at; he gives himself no airs; he understands the meaning of art and literature instinctively; he goes about enjoying his life and making other people enjoy theirs. Then they teach him to cultivate his intellect. He becomes a barrister, a civil servant, a general, an author, a professor. Every day he goes to an office. Every year he produces a book. He maintains a whole family by the products of his brain — poor devil! Soon he cannot come into a room without making us all feel uncomfortable; he condescends to every woman he meets, and dares not tell the truth even to his own wife; instead of rejoicing our eyes we have to shut them if we are to take him in our arms. True, they console themselves with stars of all shapes, ribbons of all shades, and incomes of all sizes — but what is to console us? That we shall be able in ten years’ time to spend a weekend at Lahore? Or that the least insect in Japan has a name twice the length of its body? Oh, Cassandra, for Heaven’s sake let us devise a method by which men may bear children! It is our only chance. For unless we provide them with some innocent occupation we shall get neither good people nor good books; we shall perish beneath the fruits of their unbridled activity; and not a human being will survive to know that there once was Shakespeare!”

“It is too late,” I replied. “We cannot provide even for the children that we have.”

“And then you ask me to believe in intellect,” she said.

While we spoke, man were crying hoarsely and wearily in the street, and, listening, we heard that the Treaty of Peace had just been signed. The voices died away. The rain was falling and interfered no doubt with the proper explosion of the fireworks.

“My cook will have bought the Evening News,” said Castalia, “and Ann will be spelling it out over her tea. I must go home.”

“It’s no good — not a bit of good,” I said. “Once she knows how to read there’s only one thing you can teach her to believe in — and that is herself.”

“Well, that would be a change,” sighed Castalia.

So we swept up the papers of our Society, and, though Ann was playing with her doll very happily, we solemnly made her a present of the lot and told her we had chosen her to be President of the Society of the future — upon which she burst into tears, poor little girl.

Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf

2. A Society

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Monday or Tuesday, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

De Duitse schrijver Günter Grass is op 13 april in Lübeck overleden. Grass is 87 jaar oud geworden. In 1999 ontving hij de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur.

De Duitse schrijver Günter Grass is op 13 april in Lübeck overleden. Grass is 87 jaar oud geworden. In 1999 ontving hij de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur.

Het romandebuut van Günter Grass is het beroemd geworden boek Die Blechtrommel (De blikken trommel) uit 1959. Samen met Kat en Muis (Katz und Maus) en Hondenjaren (Hundejahre) vormden ze de zogenoemde Danzig-trilogie.

De trilogie handelt over de opkomst van het nazisme, de verschrikkingen van de oorlog en de schuldgevoelens die overbleven nadat Duitsland was verslagen. Grass putte vaak uit zijn eigen ervaringen als militair en krijgsgevangene. Zijn laatste boek was De woorden van Grimm uit 2010.

Günter Grass stierf aan de gevolgen van een longinfectie

Kurze bibliographie

Romane, Novellen

Danziger Trilogie

-Die Blechtrommel. Roman. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1959.

-Katz und Maus. Novelle. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1961.

-Hundejahre. Roman. Luchterhand, Neuwied 1963.

örtlich betäubt. Roman. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1969.

Aus dem Tagebuch einer Schnecke. Roman. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1972.

Der Butt. Roman. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1977.

Das Treffen in Telgte. Erzählung. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1979.

Kopfgeburten oder Die Deutschen sterben aus. Erzählung. Luchterhand, Darmstadt und Neuwied 1980.

Die Rättin. Roman. Luchterhand. Darmstadt und Neuwied 1986.

Unkenrufe. Erzählung. Steidl, Göttingen 1992.

Ein weites Feld. Roman. Steidl, Göttingen 1995.

Mein Jahrhundert. Roman. Steidl, Göttingen 1999.

Im Krebsgang. Novelle. Steidl, Göttingen 2002.

Beim Häuten der Zwiebel. Erinnerungen. Steidl, Göttingen 2006.

Die Box. Roman. Steidl, Göttingen 2008.

Unterwegs von Deutschland nach Deutschland. Tagebuch 1990. Steidl, Göttingen 2009.

Grimms Wörter. Eine Liebeserklärung. Steidl, Göttingen 2010.

Lyrik

Die Vorzüge der Windhühner. 1956.

Gleisdreieck. 1960.

Ausgefragt. 1967.

Gesammelte Gedichte. 1971.

Letzte Tänze. 2003.

Lyrische Beute. 2004.

Dummer August. 2007.

Was gesagt werden muss. Einzelveröffentlichung, 2012.

Europas Schande. Einzelveröffentlichung, 2012.[97]

Eintagsfliegen. 2012.

Poesiealbum 302. Märkischer Verlag, Wilhelmshorst 2012.

Grafik, Skulpturen, Plastiken

Der Butt. Plastik im Hafen von Sonderburg, Dänemark.

Zeichnungen und Schreiben. Das bildnerische Werk des Schriftstellers Günter Grass. Band I: Zeichnungen und Texte 1954–1977. Hrsg. von Anselm Dreher. Darmstadt/Neuwied 1982

Zeichnungen und Schreiben II. Radierungen und Texte 1972–1982. Hrsg. von Anselm Dreher. Darmstadt/Neuwied 1984.

In Kupfer, auf Stein. Die Radierungen und Lithographien 1972–1986. Göttingen 1986.

Graphik und Plastik. Bearbeitet von Werner Timm. Regensburg 1987 (Ausstellungskatalog).

Hundert Zeichnungen 1955–1987. Ausstellungskatalog der Kunsthalle Kiel. Hrsg. von Jens Christian Jensen. Kiel 1987.

Dramen

Die bösen Köche. Ein Drama. 1956.

Hochwasser. Ein Stück in zwei Akten. 1957.

Onkel, Onkel. Ein Spiel in vier Akten. 1958.

Hoch zehn Minuten bis Buffalo. Ein Spiel in einem Akt. 1958.

Die Plebejer proben den Aufstand. Ein deutsches Trauerspiel. 1966.

Briefe, Reden usw

„O Susanna“. Ein Jazzbilderbuch. Blues, Balladen, Spirituals, Jazz. Bilder: Horst Geldmacher. Deutsche Texte: Günter Grass. Musikarbeit: Herman Wilson. Mit einem Nachwort von Joachim-Ernst Berendt. Köln und Berlin: Kiepenheuer & Witsch 1959.

(mit Pavel Kohout) Briefe über die Grenze. Versuch eines Ost-West-Dialogs. (1968)

Über das Selbstverständliche. Reden – Aufsätze – Offene Briefe – Kommentare. (1968)

Die Vogelscheuchen. Ballettlibretto (UA 1970)

Der Bürger und seine Stimme. Reden Aufsätze Kommentare. (1974)

Denkzettel. Politische Reden und Aufsätze 1965–1976. (1978)

Widerstand lernen. Politische Gegenreden 1980–1983. (1984)

Zunge zeigen. Ein Tagebuch in Zeichnungen. (1988)

Rede vom Verlust. Über den Niedergang der politischen Kultur im geeinten Deutschland. (1992)

Ein Schnäppchen namens DDR. Letzte Reden vorm Glockengeleut. (1993)

Günter Grass, Ōe Kenzaburō: Gestern vor 50 Jahren. Ein deutsch-japanischer Briefwechsel. 1. Auflage. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 1995.

Rede über den Standort (1997)

Zeit, sich einzumischen. Die Kontroverse um Günter Grass und die Laudatio auf Yasar Kemal in der Paulskirche (1998)

Vom Abenteuer der Aufklärung. Werkstattgespräche mit Harro Zimmermann. (1999)

Günter Grass – Helen Wolff. Briefe 1959–1994. (2003).

Hans Christian Andersens Märchen – gesehen von Günter Grass (2005).

Uwe Johnson – Anna Grass – Günter Grass. Der Briefwechsel 1961–1984. (2007).

Martin Kölbel (Hrsg.): Willy Brandt und Günter Grass – Der Briefwechsel. Steidl Verlag, Göttingen 2013.

Verfilmungen

Die Blechtrommel. Spielfilm, Deutschland, Polen, Frankreich, Jugoslawien, 1980, 142 Min., Regie: Volker Schlöndorff, u. a. mit Mario Adorf als Alfred Matzerath, Angela Winkler als Agnes Matzerath, David Bennent als Oskar, Katharina Thalbach als Maria Matzerath

Katz und Maus, Spielfilm, BRD, 1967, 88 Min., Regie: Hansjürgen Pohland, u. a. mit Wolfgang Neuss als Pilenz

Mein Jahrhundert, Fernsehlesung. Günter Grass liest Mein Jahrhundert im Deutschen Theater Göttingen. Produktion Radio Bremen/3sat 1999.

Die Rättin. Fernsehfilm, Deutschland, 87 Min., Regie: Martin Buchhorn, Erstausstrahlung: ARD, 14. Oktober 1997, u. a. mit Matthias Habich als Markus Frank

Unkenrufe – Zeit der Versöhnung. Spielfilm, Deutschland, Polen, 2005, 98 Min., Regie: Robert Glinski

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Günter Grass, In Memoriam

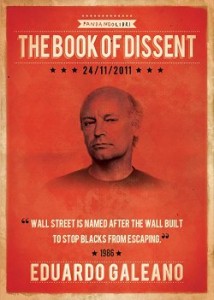

Eduardo Hughes Galeano (Montevideo 1940–2015) was een Uruguayaans journalist en schrijver. Zijn bekendste werken zijn Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971 vert. Aderlating van een continent) en Memoria del fuego (1986). Galeano vermengt in zijn boeken fictie, journalistiek en geschiedschrijving. Hij geldt als een van de belangrijkste Zuid-Amerikaanse schrijvers.

Eduardo Hughes Galeano (Montevideo 1940–2015) was een Uruguayaans journalist en schrijver. Zijn bekendste werken zijn Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971 vert. Aderlating van een continent) en Memoria del fuego (1986). Galeano vermengt in zijn boeken fictie, journalistiek en geschiedschrijving. Hij geldt als een van de belangrijkste Zuid-Amerikaanse schrijvers.

Na een militaire staatsgreep in 1973 belandde Galeano in de gevangenis en later moest hij Uruguay ontvluchten. In 1985 keerde hij terug naar Montevideo.

Eduardo Galeano overleed op 13 april 2015 op 74-jarige leeftijd aan longkanker.

Beknopte bibliografie:

Los días siguientes (1962)

China, Crónica De Un Desafío (1964)

Guatemala: Occupied Country (1967)

Su majestad el fútbol (1968)

Las venas abiertas de América Latina (1971)

Memoria del fuego (1982–1986)

Mirrors: Stories of Almost Everyone (2009)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, BOOKS. The final chapter?, DEAD POETS CORNER, In Memoriam

De kinderen gingen hem achterna en bleven hem sarren. Ze hadden altijd angst voor hem gehad. Weerloos was hij nu aan hen overgeleverd. Niemand deed een poging hen te bedaren. Ook Kaffa niet, hoewel hij walgde van het tafereel.

De kinderen gingen hem achterna en bleven hem sarren. Ze hadden altijd angst voor hem gehad. Weerloos was hij nu aan hen overgeleverd. Niemand deed een poging hen te bedaren. Ook Kaffa niet, hoewel hij walgde van het tafereel.

Vol weerzin hield hij het lemmet van het mes nogmaals onder de koude straal. Het water spoot bruisend uit de pomphals, of het kookte. Kaffa merkte dat het mes trilde als hij het in zijn linkerhand droeg. De hand waarmee hij had gegooid. Het verwonderde hem. Zijn linkerhand was altijd sterk en zeker geweest. Hij nam het mes over in de rechter. Die was rustiger. Hij nam het weer over in de linker. Die hand trilde zo heftig dat hij het mes direct weer moest overgeven aan de rechterhand. Hij vloekte. Hij kon niet verdragen dat de zenuwen de baas waren over zijn lijf. De slager kwam het plein op zeulen op zijn bakfiets, waarin enkele biggen gilden. Hijgend plaatste hij de bak naast de pomp. Hij transpireerde hevig en stonk naar stallen. `Je wast je mes?’ vroeg hij, verbaasd over zichzelf omdat hij de gek aansprak. `Ja, ik was mijn mes’, zei Kaffa, terwijl hij het trillen in zijn linkerhand voelde en vaag het geouwehoer van Jacob Ramesz over zijn worp met het mes opving. Wat hem bijna in woede deed uitbarsten. Godverdomme. Waar bemoeide die ouwe vent zich mee? `Ik was mijn mes’, zei hij nog eens. `Dat verrekte bloed kleeft eraan als teer.’ Azurri trok zijn hemd uit en waste kop en bovenlijf onder de koele straal van de pomp. Hij pompte een emmer vol en gooide hem over de varkens, die van het koude water schrokken en weer gilden. Waarschijnlijk hadden ze in de paar weken dat ze leefden nooit water gezien. Nu pas zag de slager hoe Elysee tussen de gebouwen van Chile door hinkte en om zijn ezel riep, al was het dier in geen velden of wegen te bekennen. En de joelende kinderen die de man naliepen. Er kwam een minachtende grijns rond de mond van de slager. Angela holde naar Kaffa. Dankbaar omdat hij haar uit de klauwen van Elysee had gehaald, sprong ze tegen hem op en bleef als een klit om zijn hals hangen. Hij drukte haar tegen zich aan. Voelde haar natte lijf door zijn kleren heen. Ze duwde haar wang in zijn nek, ademde in zijn gezicht. Hij zoende haar haren, proefde haar zoute tranen. Ze huilde geluidloos. Lieve, lieve vrouw. Hij streelde haar warme lijf, haar dijen. `Lekker warm dier’, lachte hij en hij beet in haar oor. Hij zag de blik van Azurri, die zich gruwelijk ergerde aan het gedrag van zijn dochter. Net toen hij tegen het meisje wilde uitvallen, fluisterde zijn vrouw hem wat in het oor.

Waarschijnlijk over het voorval met de waarzegger en de manier waarop Kaffa het meisje had bevrijd. Het leek de slager niet tot betere gevoelens voor Kaffa aan te zetten, maar hij hield zich koest en liep mokkend terug naar zijn bakfiets vol varkens. Om zijn gevoelens te luchten moesten de beesten, die nergens schuld aan hadden, het ontgelden. Met zijn blote vuisten sloeg hij de dieren waar hij ze raken kon. Op kop, rug en nek. De biggen, die niets van deze afstraffing begrepen, begonnen wild te krijsen en sprongen tegen de schotten van de bak omhoog. Geschrokken van het lawaai zette Kaffa het meisje op de grond. Hij zag dat er kort gras tegen de verdrukking in onder het granieten pompbed uitgroeide, een klein stukje maar, want verderop verstikte het in de modder en de door zeik verzuurde grond. Hij veegde het lemmet van zijn mes droog aan de pijp van zijn broek, zette het aan in zijn handpalm en voelde dat het nog scherper kon. Hij wette het secuur op de gladde rand van de spoelbak. Kleine gensters spoten in het rond. `Het is mijn beste mes’, zei Kaffa verontschuldigend tegen Azurri. `Het ligt goed in de hand. Het treft precies waar ik het hebben wil.’ Kaffa liep terug naar zijn plaats. Veegde met een voet de grenzen van de oude landen uit. Tekende met de punt van het mes een cirkel. Sneed de cirkel in twee gelijke delen. Legde in elk land een lucifer. Zo had elk land zijn eigen koning. De slager, die zag dat Kaffa met zijn spel wilde beginnen, vergat zijn varkens, veegde het zweet van zijn voorhoofd, schurkte zijn rug tegen de opstand van de pomp en liep naar Kaffa. Zonder te vragen of hij mocht meedoen spuwde hij in zijn handen en hurkte tegenover Kaffa neer. Nu had hij eindelijk de kans om die gek eens te laten zien wie de werkelijke kampioen van het dorp was.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (33)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

De Stichting Motel Mozaïque organiseert jaarlijks een aantal bijzondere culturele programma’s, waarvan het gelijknamige festival ondertussen is uitgegroeid tot een nationaal en internationaal gewaardeerd evenement. In 2004 is Motel Mozaïque tot ‘Beste Festival’ uitgeroepen door de Vereniging Nederlandse Poppodia & Festivals. Motel Mozaïque is ontstaan én gevestigd in Rotterdam.

Het kunstenfestival Motel Mozaïque is de meest in het oog springende en bekendste activiteit van de stichting. Motel Mozaïque biedt een organische mix van muziek, theater, beeldende kunst, film en de mogelijkheid daadwerkelijk te overnachten in kunstwerken. Daarnaast (ver)leiden de Gidsen van Motel Mozaïque de bezoekers langs bijzondere plekken in de stad en in het festival.

Gastvrijheid is de rode draad in het programma en tevens de inspiratiebron voor de makers van Motel Mozaïque. Tijdens het festival zijn bekende en onbekende muzikanten, dj’s, beeldend kunstenaars en theatergezelschappen afwisselend of gezamenlijk te gast in het motel. De festivaleditie Motel Mozaïque is een zeer nauwe samenwerking van Motel Mozaïque met de Rotterdamse kunstinstellingen de Rotterdamse Schouwburg, CBK Rotterdam en Rotown.

Motel Mozaïque is ontstaan tijdens Rotterdam 2001, Culturele Hoofdstad van Europa. Initiatiefnemer van dit kunstenfestival is Harry Hamelink. Het redactieteam scout en nodigt artiesten en performers uit die in hun werk laten zien, naast warmte en kwaliteit, een ‘open mind’ te hebben. Daarnaast creëren kunstenaars slaapplaatsen op uiteenlopende plekken in de stad en worden de bezoekers door gidsen meegenomen naar de programma-onderdelen die zij zelf nog niet ontdekt hebben.

Naast Kate Tempest zijn onder meer te gast: Temples, Asgeir, Jungle, George Ezra, Kurt Vile, Wild Beasts, Larry Gus, Aufgang, Hauschka, Angel Olsen, Ivo Dimchev, Florentijn Hofman, Jaga Jazzist & Rotterdam Sinfonia, AlunaGeorge, Laura Mvula, The Veils, Jose James, Soap&Skin, Patrick Watson, Django Django, Balthazar, Blaudzun, Fink, The Maccabees, Jose Gonzalez, Belle & Sebastian, James Blake, Lykke Li, Mumford & Sons, Ben Howard, James Vincent McMorrow, Band Of Horses, Angus & Julia Stone, The Gaslamp Killer, Mulatu Astatke, Fuck Buttons, Midlake, The Whitest Boy Alive, Fever Ray, Nico Muhly, dEUS, Trentemoller, Goldfrapp, Efterklang, CocoRosie, LCD Soundsystem, Scissor Sisters, Antony & The Johnsons, Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, Nancy Sinatra, Arthur Lee, The Kills, Feist, The Libertines, Peaches, Carina Molier, Benji Reid, Zita Swoon, Abattoir Fermé, !!!, A Silver Mt. Zion, Kung Fu, PONI, Schie 2.0, Observatorium, Bliss, Miriam Reeders, Madeleine Berkhemer, Michael Spencer Jones, Gotan Project, Múm, Sigurdur Gudmundsson, Emiliana Torrini, Atelier van Lieshout, Dré Wapenaar, Mogwai, Claudy Jongstra, Villanella / Hanneke Paauwe, The Veils, Amon Tobin en 2ManyDJ’s waren al te gast tijdens Motel Mozaïque.

Gisteren was Kate Tempest op TV te zien in DWDD met een veel te kort optreden, vandaag (vrijdag 10 april) treedt het Engelse super-dicht-talent op in Rotterdam. Het optreden van vandaag maakt deel uit van haar Europese tour. Na Rotterdam staan deze maand de volgende shows nog op het programma: 11 April: Trix, Antwerp – 13 April: VEGA, Copenhagen – 14 April: Debaser, Stockholm – 16 April: Fri-Son, Fribourg – 17 April: Biko, Milan – 18 April: Teatro Quirinetta, Rome – 20 April: Gebaude 9, Cologne – 21 April: Berghain, Berlin

Voor meer info over dichter Kate Tempest, zie deze website (fleursdumal.nl) en natuurlijk haar eigen website: katetempest.co.uk

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Kate/Kae Tempest, MUSIC, Tempest, Kate/Kae, THEATRE

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature