Fleurs du Mal Magazine

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 153

Cupid laid by his brand and fell asleep,

A maid of Dian’s this advantage found,

And his love-kindling fire did quickly steep

In a cold valley-fountain of that ground:

Which borrowed from this holy fire of Love,

A dateless lively heat still to endure,

And grew a seeting bath which yet men prove,

Against strange maladies a sovereign cure:

But at my mistress’ eye Love’s brand new-fired,

The boy for trial needs would touch my breast,

I sick withal the help of bath desired,

And thither hied a sad distempered guest.

But found no cure, the bath for my help lies,

Where Cupid got new fire; my mistress’ eyes.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 152

In loving thee thou know’st I am forsworn,

But thou art twice forsworn to me love swearing;

In act thy bed-vow broke and new faith torn,

In vowing new hate after new love bearing;

But why of two oaths’ breach do I accuse thee,

When I break twenty? I am perjured most,

For all my vows are oaths but to misuse thee,

And all my honest faith in thee is lost.

For I have sworn deep oaths of thy deep kindness:

Oaths of thy love, thy truth, thy constancy,

And to enlighten thee gave eyes to blindness,

Or made them swear against the thing they see.

For I have sworn thee fair: more perjured eye,

To swear against the truth so foul a lie.

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 152

Liefde voor jou maakt, weet je, dat ik loog,

Maar jij loog dubbel met jouw liefdes-eden:

Je bed-eed brak je en nieuwe trouw vervloog,

Met liefde nieuw gebaard, en nieuwe haat beleden;

Maar mag ‘k om dubbele eedbreuk jou beleren,

Als ik er twintig breek? Mij treft meer schuld,

Want iedere eed dient slechts om jou te onteren,

En mijn geloof in jou werd nooit vervuld.

Want diep vertrouwde ik op jouw mededogen,

Bezwoer je liefde, trouw, standvastigheid,

En schonk voor licht in jou aan blindheid ogen,

Of dwong hun blind te zijn voor zichtbaarheid.

Mijn eed bood jou verschoning: meineed oog,

Dat jij de waarheid zo vervuild beloog!

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld

(dec. 2012)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare

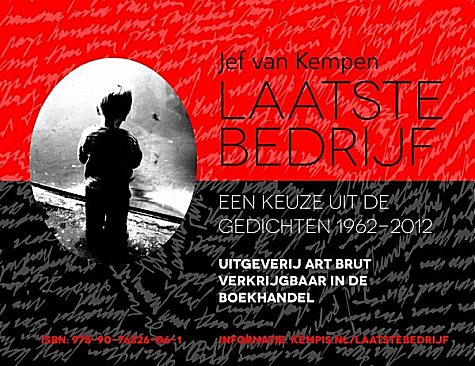

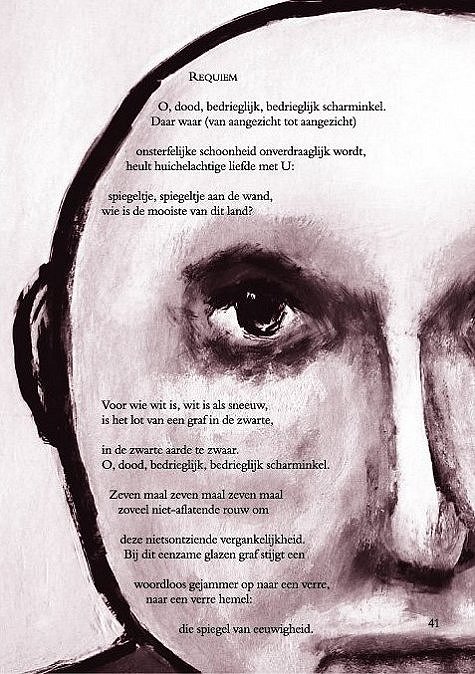

Op 16 december 2012 verschijnt:

Jef van Kempen

LAATSTE BEDRIJF

een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012

Presentatie dichtbundel: Laatste Bedrijf van Jef van Kempen op zondag 16 December 2012 om 14.00 uur bij Boekhandel Livius in Tilburg

Schrijver en dichter Ton van Reen en stadsdichter en actrice Esther Porcelijn zullen, op eigen wijze, medewerking verlenen aan de lancering van dit bijzondere boek.

Jef van Kempen (1948) publiceerde poëzie en korte verhalen, biografische artikelen en essays, o.a. over Guido Gezelle, J.-K. Huysmans, Theo van Doesburg, Antony Kok, de Stijlbeweging en Walter Breedveld. Hij is ook (mede)samensteller van enkele literaire bloemlezingen. Daarnaast schreef hij voor boeken, kranten en tijdschriften vele artikelen over de Brabantse geschiedenis. De serie artikelen die hij voor het Brabants Dagblad schreef over de straat waar hij geboren is, werden gebundeld onder de titel: Onze Lieve Vrouw van de Veestraat en andere verhalen en in het boek: Het gevoel dat je hier thuishoort. Jef van Kempen is ook actief als (literair) vertaler. Daarnaast is hij redacteur van kempis.nl (een van de belangrijkste Nederlandse poëziewebsites) en drie andere literaire websites.

De bundel bevat, naast gepubliceerde en ongepubliceerde gedichten, talrijke illustraties van Jef van Kempen uit dezelfde periode.

Jef van Kempen

Laatste Bedrijf.

Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012

Uitgeverij Art Brut

ISBN: 978-90-76326-06-1

68 pag. – 12,50 euro

Geïllustreerd, 24×15 cm

Gedichten en illustraties van Jef van Kempen

Vormgeving Michiel Leenaars

Verschijnt op 16 december 2012

Presentatie van 14.00 tot 15.30 uur bij Boekhandel Livius, Nieuwlandstraat 56 in Tilburg.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kempen, Jef van

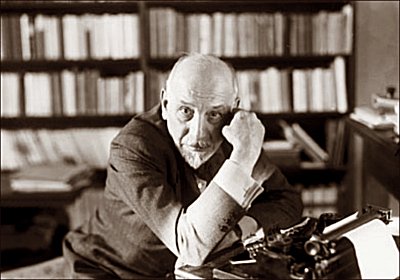

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (32)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

1

I understand, at last.

Upset? No, why should I be? So much water has passed under the bridges; the past is dead and distant. Life is here now, this life: a different life. Lawns, round about, and stages, the buildings miles away, almost in the country, between green grass and blue sky, of a cinematograph company. And she is here, an actress now…. He an actor too? Just fancy! Why, then, they must be colleagues? Splendid; I am so glad….

Everything perfect, everything smooth as oil. Life. That rustle of her blue silk skirt, now, with that curious white lace jacket, and that little winged hat like the helmet of the god of commerce, on her copper-coloured hair… yes. Life. A little heap of gravel turned up by the point of her sunshade; and an interval of silence, With her eyes wandering, fixed on the point of her sunshade that is turning up that little heap of gravel.

“What? Yes, of course, dear: a great bore.”

This is undoubtedly what must have happened yesterday, during my absence. The Nestoroff, with those wandering eyes of hers, strangely wide open, must have gone to the Kosmograph on purpose, in the hope of meeting him; she must have strolled up to him with an indifferent air, as one goes up to a friend, an acquaintance whom one happens to meet again after many years, and the butterfly, without the least suspicion of the spider, must have begun to flap his wings, quite exultant.

But how in the world did not Signorina Luisetta notice anything?

Well, that is a satisfaction which Signora Nestoroff must have had to forego. Yesterday, Signorina Luisetta, to celebrate her father’s return home, did not go with Signor Nuti to the Kosmograph. And so Signora Nestoroff cannot have had the pleasure of shewing this proud young lady who, the day before, had declined her invitation, how she, at any moment, whenever the fancy took her, could tear from the side of any proud young lady and recapture for herself all the mad young gentlemen who threatened tragedies, “st”, like that, by holding up a finger, and at once tame them, intoxicate them with the rustle of a silk skirt and a little heap of gravel turned up with the point of a sunshade. A bore, yes, a great bore unquestionably, because to this pleasure which she has had to forego Signora Nestoroff attached great importance.

That evening, knowing nothing of what had happened, Signorina Luisetta saw the young gentleman return home completely transformed, radiant with happiness. How was she to suppose that this transformation, this radiance could be due to a meeting with the Nestoroff, if, whenever she thinks with terror of that meeting, she sees red, black, confusion, madness, tragedy? And so this change, this radiance, was the effect of Papa’s return home on him also? Well, that it is of any great importance to him, her father’s return home, Signorina Luisetta cannot suppose, no; but that he should take pleasure in it, and seek to attune himself to other people’s rejoicing, why in the world not?

How else is his jubilation to be explained? And it is something to be thankful for; it is a thing to rejoice in, because this jubilation shews that his heart has become lighter, more open, so that he can readily assimilate the joy of other people.

These must certainly have been the thoughts of Signorina Luisetta. Yesterday; not to-day.

To-day she came to the Kosmograph with me, her face clouded. She had found, greatly to her surprise, that Signor Nuti had already left the house at an early hour, while it was still dark. She did not wish to display, as we went along, resentment and alarm, after the spectacle offered me last night of her gaiety; and so asked me where I had been yesterday and what I had done. “I? Oh, only a little pleasure jaunt….” And had I enjoyed myself? “Oh, immensely, to begin with at least. Afterwards….” The way things happen. We make all the arrangements for a pleasure party; we imagine that we have thought of everything, have taken every precaution so that the excursion may be a success, with no unfortunate incident to mar it; and yet there is always something, one of the many things, of which we have not thought; one thing escapes us… well, for instance, suppose there is a family with a number of children, who propose to go and spend a fine summer day picnicking in the country, there are the second child’s shoes, in one of which there is a nail, a mere nothing, a tiny nail, inside, sticking up in the heel, which needs hammering down. The mother remembered it, as soon as she got out of bed; but afterwards, you know what happens–with everything to get ready for the excursion, she forgot all about it. And that pair of shoes, with their little tongues sticking up like the pricked ears of a wily rabbit, standing in the row among all the other pairs, cleaned and polished and all ready for the children to put on, wait there and seem to be gloating in silence over the trick they are going to play on the mother who has forgotten all about them and who now, at the last moment, is in a greater bustle than ever, in wild confusion, because the father is down below at the foot of the stair shouting to her to make haste and all the children round her shout to her to make haste, they are so impatient. That pair of shoes, as the mother takes them to thrust them hurriedly on the child’s feet, say to her with a mocking laugh:

“Ah yes, mother dear; but us, you know? You have forgotten about us; and you’ll see that we shall spoil the whole day for you: when you are half way there that little nail will begin to hurt your child’s foot and make it cry and limp.”

Well, something of that sort happened to me too. No, not a nail to be hammered down in my boot. Another little detail had escaped my memory…. “What?” Nothing: another little detail. I did not wish to tell her. Another thing, Signorina Luisetta, which perhaps had long ago broken down in me.

To say that Signorina Luisetta paid me any close attention would not be true. And, as we went on our way, while I allowed my lips to go On speaking, I was thinking:

“Ah, you are not interested, my dear child, in what I am telling you? My misadventure leaves you indifferent, does it? Well, you shall see with what an air of indifference I, in my turn, to pay you back in your own coin, am going to receive the unpleasant surprise that is in store for you, as soon as you enter the Kosmograph me: you shall see!”

In fact, before we had advanced five yards across the tree-shaded lawn in front of the first building of the Kosmograph, there we saw, strolling side by side, like the dearest of friends, Signor Nuti and Signora Nestoroff: she, with her sunshade open, resting upon her shoulder, and twirling the handle.

What a look Signorina Luisetta gave me! And I: “You see! They are taking a quiet stroll. She is twirling her sunshade.”

So pale, however, so pale had the poor child turned, that I was afraid of her falling to the ground, in a faint: instinctively I put out my hand to support her arm; she withdrew her arm angrily, and looked me straight in the face. Evidently the suspicion flashed across her mind that it was my doing, a plot on my part (by arrangement, very possibly, with Polacco), that quiet and friendly reconciliation of Nuti and Signora Nestoroff, the first-fruits of the visit paid by me to that lady two days ago, and perhaps also of my mysterious absence yesterday. It must have seemed to her a vile mockery, all this secret machination, as it entered her mind in a flash. To make her dread the imminence, day after day, of a tragedy, should those two meet; to make her conceive such a terror of their meeting; to make her suffer such agony in order to pacify his ravings with a piteous deception, which had cost her so dear, and to what purpose! To offer her as a final reward the delicious picture of those two taking their quiet morning stroll under the trees on the lawn? Oh, villainy! Was it for this? For the amusement of laughing at a poor child who had taken it all seriously, plunged into the midst of this sordid, vulgar intrigue? She looked for nothing pleasant, in the absurd, miserable conditions of her life; but why this as well? Why mockery also? It was vile!

All this I read in the poor child’s eyes. Could I prove to her, there and then, that her suspicion was unjust, that life is like that–to-day more than ever it was before–made to offer such spectacles; and that I myself was in no way to blame?

I had hardened my heart; I was glad that she should pay for the injustice of her suspicion by her suffering at that spectacle, at the sight of those people, to whom I as well as she, unasked, had given something of ourselves, something that was now smarting, bruised and wounded, inside us. But we deserved it! And now, it pleased me to have her at this moment as my companion, while those two strolled up and down there without so much as seeing us. Indifference, indifference, Signorina Luisetta, there you are!

“If you will excuse me,” it occurred to me to say to her, “I shall go and get my camera, and take my place here, as is my duty, impassive.” And I felt a strange smile on my lips, which was almost the grin of a dog when he bares his teeth at some secret thought. I was looking meanwhile towards the door of the building beyond, from which emerged, coming towards us, Polacco, Bertini and Fantappiè. Suddenly there occurred a thing which I ought really to have expected, which justified Signorina Luisetta in trembling so violently and rebuked me for having chosen to remain indifferent. My mask of indifference I was obliged to throw aside in a moment, at the threat of a danger which did really seem to all of us imminent and terrible. I caught the first glimpse of it in the appearance of Polacco, who had come close up to us with Bertini and Fantappiè. They were talking among themselves, evidently of that couple who were still strolling beneath the trees, and all three were laughing at some witticism that had fallen from Fantappiè, when all of a sudden they stopped short in front of us with faces of chalk, staring eyes, all three of them. But most of all in the face of Polacco I read terror. I turned to look over my shoulder: Carlo Ferro!

He was coming up behind us, still with his travelling cap on his head, as he had left the train a few minutes earlier. And those two, meanwhile, continued to stroll up and down, together, without the least suspicion, under the trees. Did he see them! I cannot say. Fantappiè had the presence of mind to shout:

“Hallo, Carlo Ferro!”

The Nestoroff turned round, left her companion standing, and then one saw–free of charge–the moving spectacle of a lion-tamer who amid the terror of the spectators advances to meet an infuriated animal. Calmly she advanced, without haste, still balancing her open sunshade on her shoulder. And she had a smile on her lips, which said to us, without her deigning to look at us: “What are you afraid of, you idiots! I am here, a’nt I?” And a look in her eyes which I shall never forget, the look of one who knows that everyone must see that no fear can find a place in a person who looks straight ahead and advances so. The effect of that look on the savage face, the disordered person, the excited gait of Carlo Ferro was remarkable. We did not see his face, we saw his body grow limp and his pace slacken steadily as the fascination drew nearer to him. And the one sign that she too must be feeling somewhat agitated was this: she began to address him in French.

None of us cast a glance beyond her, where Aldo Nuti remained by himself, planted among the trees, but suddenly I became aware that one of us, she, Signorina Luisetta, was looking in that direction, was looking at him, and had perhaps looked at nothing else, as though for her the terror lay there and not in the two at whom the rest of us were gazing, in dismayed suspense.

But nothing occurred for the moment. To break the storm, making a great din, there dashed upon the lawn, in the nick of time, Commendator Borgalli accompanied by various members of the firm and employees from the manager’s office. Bertini and Polacco, who were with us, were swept away; but the managing director’s fierce reproaches were aimed also at the other two producers who were absent. The work was going to pieces! No control of production; the wildest confusion; a perfect Tower of Babel! Fifteen, twenty subjects left in the air; the companies scattered here, there and everywhere, when it had been announced, weeks ago, that they must be assembled and ready to get to work on the tiger film, on which thousands and thousands of lire had been spent! Some were off to the hills, some to the sea; eating their heads off! What was the use of keeping the tiger there!

There was still the whole part of the actor who was to kill it wanting? And where was the actor? Oh, he had just arrived, had he? How was that? Where had he been?

Actors, supers, scene-painters had come pouring in a crowd from every direction at the shouts of Commendator Borgalli, who had the satisfaction of measuring thus the extent of his own authority, and the fear and respect in which he was held, by the silence in which all these people stood round and then dispersed, when he concluded his harangue with the words:

“To your work! Get along back to work!”

There vanished from the lawn, as though it had been first of all submerged by this tide of people, then carried away by their ebb, every trace of the–shall we say–dramatic situation of a moment earlier; there, in the foreground, the Nestoroff and Carlo Ferro; beyond them, Nuti, solitary, apart, under the trees. The ground lay empty before us. I heard Signorina Luisetta sobbing by my side:

“Oh, heavens, oh, heavens,” and she wrung her hands. “Oh, heavens, what next? What will happen next?”

I looked at her with irritation, but tried, nevertheless, to comfort her:

“Why, what do you want to happen? Keep calm! Didn’t you see? All arranged beforehand. … At least, that is my impression. Yes, of course, keep calm! This surprise visit from Ferro…. I bet she knew all about it; I shouldn’t be surprised if she telegraphed to him yesterday to come; why yes, of course, to let him find her here engaged in a friendly conversation with Signor Nuti. You may be sure that is what it is.” “But he? He?”

“Who is “he”? Nuti?”

“If it is all a trick played by those two….”

“You are afraid he may notice it?”

“Yes! Yes!”

And the poor child began again to wring her hands.

“Well? And what if he does notice it?” said I. “You needn’t worry yourself; he won’t do anything. Depend upon it, this was arranged beforehand too.”

“By whom? By her? By that woman?”

“By that woman. She must first have made quite certain, before talking to him, that the other man would be able to turn up in time, without any danger to anyone; keep calm! Otherwise, Ferro would not have come upon the scene.”

We were quits. My statement embodied a profound contempt for Nuti; if Signorina Luisetta desired peace of mind, she was bound to accept it. She did so long to secure peace of mind, Signorina Luisetta; but on these terms, no; she would not. She shook her head violently: no, no.

There was nothing then to be done! But as a matter of fact, notwithstanding my faith in the Nestoroff’s cold perspicacity, in her power, when I reminded myself of Nuti’s desperate ravings, I did not feel any too certain myself that it was with him that we should concern ourselves. But this thought increased my irritation, already moved by the spectacle of that poor, terrified child. Despite my resolution to place and keep all these people in front of my machine as food for its hunger while I stood impassively turning the handle, I saw myself too obliged to continue to take an interest in them, to occupy myself with their affairs. There came back to me also the threats, the fierce protestations of the Nestoroff, that she feared nothing from any man, Because any other evil–a fresh crime, imprisonment, death itself–she would reckon as less than the evil which she was suffering in secret and preferred to endure. Had she perhaps suddenly grown tired of enduring it? Could this be the reason of her deciding yesterday, during my absence, to take the first step towards Nuti, in contradiction of what she had said to me the day before?

“No pity,” she had said to me, “neither for myself nor for him!”

Had she suddenly felt pity for herself? Not for him, certainly! But pity for herself means to her extricating herself by any means in her power, even at the cost of a crime, from the punishment she has inflicted on herself by living with Carlo Ferro. Suddenly making up her mind, she has gone to meet Nuti and has made Carlo Ferro return.

What does she want? What is going to happen next?

This is what happened, in the meantime, at midday beneath the pergola of the tavern, where–dressed some of them as Indians and others as English tourists–a crowd of actors and actresses from the four companies had assembled. All of them were or pretended to be infuriated and upset by Commendator Borgalli’s outburst that morning, and had for some time been taunting Carlo Ferro, letting him clearly understand that they were indebted to him for that outburst, he having first of all advanced all those silly claims and then tried to back out of the part allotted to him in the tiger film, and having left Rome, as though there were really a great risk attached to the killing of an animal cowed by all those months of captivity: an insurance for one hundred thousand lire, agreements, conditions, etc. Carlo Ferro was seated at a table, a little way off, with the Nestoroff. His face was yellow; it was quite evident that he was making an enormous effort to control himself; we all expected him at any moment to break out, to turn upon us. We were, therefore, left speechless at first when, instead of him, another man, to whom no one had given a thought, broke out all of a sudden and turned upon him, going up to the table at which Ferro and the Nestoroff were sitting. It was he, Nuti, as pale as death. In a silence that throbbed with a violent tension, a faint cry of terror was heard, to which Varia Nestoroff promptly replied by laying her hand, imperiously, upon Carlo Ferro’s arm.

Nuti said, looking Ferro straight in the face:

“Are you prepared to give up your place and your part to me? I promise before everyone here to take it on unconditionally.”

Carlo Ferro did not spring to his feet nor did he fly at the tempter. To the general amazement he sank down, sprawled awkwardly in his chair; leaned his head to one side, as though to look up at the speaker, and before replying raised the arm upon which the Nestoroff’s hand was resting, saying to her:

“Please….”

Then, turning to Nuti:

“You? My part? Why, I shall be delighted, my dear Sir. Because I am a fearful coward … you wouldn’t believe how frightened I am.

Delighted, my dear Sir, delighted!”

And he laughed, as I never saw a man laugh before!

His laughter made us all shudder, and, what with this general shudder and the whiplash of his laughter, Nuti was left quite helpless, his mind certainly vacillating from the impulse which had driven him to face his rival and had now collapsed, in the face of this awkward and teasingly submissive reception. He looked round him, and then, all of a sudden, at the sight of that pale, puzzled face, everyone began to laugh at him, broke into peals of loud, irrepressible laughter. The painful tension was broken in this way, in this enormous laugh of relief, at the challenger’s expense. Exclamations of derision sounded here and there, like jets of water amid the clamour of the laughter: “He’s cut a pretty figure!” “Caught in the trap!” “Like a mouse!”

Nuti would have done better to join in the laughter as well; but, most unfortunately, he chose to persist in the ridiculous part he had adopted, looking round for some one to whom he might cling, to keep himself afloat in this cyclone of hilarity, and stammered:

“Then… then, you agree?… I am to play the part… you agree!”

But even I myself, however reluctantly, at once took my eyes from him to look at the Nestoroff, whose dilated pupils gleamed with an evil light.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (32)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XI

Toen de oude man over partizanen begon te praten, had de chauffeur zich teruggetrokken, was achter zijn stuurrad gaan zitten en bracht de bus weer op gang. Durfde niets meer tegen de oude man te zeggen over boete. Er staat boete op het trekken aan een noodrem! En de betrokken passagier moest dan de bus uit. De chauffeur beperkte zich tot het herstellen van de oude toestand, de bus voort te bewegen over de weg, langs de rivier het Lange Rak, tussen Tepple en Wrak. En voor de rest zijn mond te houden. Hij was een van die partizanen. Durfde er nu niet meer voor uit te komen. Hoewel hij met doodsverachting partizaan was geweest. Partizanen vochten voor eerlijkheid en recht. Maar recht bestond niet en eerlijk was geen mens. De partizanen vochten dus zo maar wat, voor een onduidelijk doel. Een van de legers won, het andere verloor, dat was oorlog. Partizanen hoorden bij geen leger. Ze lieten alle soorten soldaten en burgers de lucht in vliegen. Dat werd weer bewezen door de oude man met de nek vol littekens die aan de noodrem had getrokken om even te zeggen dat er geen recht was en dat er oorlog was geweest en ook dat er al vrede was in oorlogstijd.

De bus reed verder, maar iedereen had een hart vol wrok. Iedereen had zo zijn gedachten over de oorlog. Misschien hadden die en die nog geleefd als er geen partizanen geweest waren. Maar dat was eigenlijk ook weer geen redenering voor mensen die stiekem geloofden in voorbeschikking van leven en dood door de Almachtige Schepper.

Ik telde niet hoeveel mensen er onderweg in- en uitstapten. Merkte wel dat veel mensen de bus al verlieten in Tepple. In Wrak stapte niemand uit. Wrak was één grote puinhoop, terwijl er enkel vredelievende soldaten gehuisvest waren geweest. Alleen God woonde nog in Wrak. De kerk en de toren waren om en op het altaar neergestort. God woonde in een ruïne.

Tot nu toe had niemand kans gezien de kelken en monstransen uit het tabernakel te halen. Heel Wrak was één puinhoop. Daar hoeft niemand heen met de bus. Daar komt niemand uit. En niemand wil erin. De bus hoefde er dus niet te stopppen. En God reist niet met de bus. Maar de bus was dat stoppen nog gewend uit de oorlog. Per slot van rekening was het een frontbus geweest.

In Borz woonden niet meer mensen dan in Oeroe. Alleen waren de mensen van Borz niet zo melancholiek als die van Oeroe. Er liep dan ook geen waterader onder Borz.

De brug van Borz was een noodbrug. Hoog ijzerwerk waarop je met gemak een dak zou kunnen leggen. Nu waren het hoge turnrekken. Alleen vogels konden er in turnen.

In Boeroe koesterden de mensen openlijk haat tegen die van Oeroe. Er liepen er heel wat rond met hun koppen in wit gaasverband, omdat er kermis was in Oeroe.

We reden Oeroe binnen. Passeerden de woonwagen van Cherubijn. Cherubijn zat in de deuropening. De marmot zag ik niet. Cherubijn zag mij niet. Hij hield net zijn hoofd met de luie nekspieren naar de andere kant. Kon niet tijdig zijn hoofd omdraaien om de bus te zien.

De bus hield stil op de markt. Ik holde naar de wagen.

Cherubijn was blij toen hij me zag, ging in halsbrekende standen staan om mij beter te zien en om zijn nekspieren te laten rusten. En hij wilde weten waar ik was geweest. Dat verzweeg ik.

Ik ging in het gras liggen. Speelde met de marmot die naar me toe kwam en tussen mijn benen wilde gaan liggen. Hij was dat al gewend in één nacht. Zo snel kun je een marmot iets leren.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

foto kempis.nl

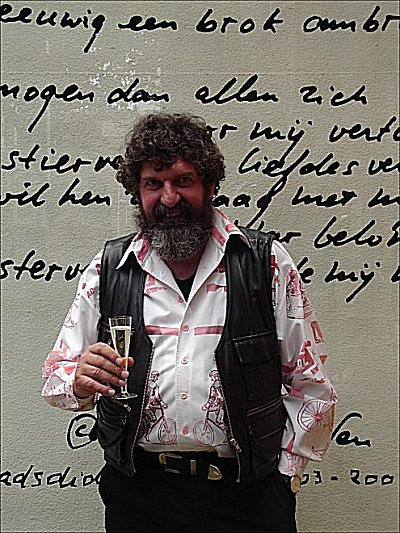

JACE van de Ven

4 gedichten voor

Vóór de kerk van Gilze

(gemeente Gilze-Rijen NB)

I

hieronder in het kempisch zand

(groot)moeders, -vaders, kinderen,

acht kuilen, vijfenvijftig graven,

duizend gilzenaren ons verwant

ze liggen op hun rug te wachten

tot hij die hen beloofd is komt

de godganse dag wij onbedacht

over hun blinde graven jachten

II

al eeuwenlang zijn ze morsdood

maar, vlees op de botten, zouden

wij ze vast herkennen aan gezicht

aan leest, of aan een manke poot

zeggen, gij bent er toch geen van?

en ja hoor, ik ben een echte gilse

handen schudden, namen noemen

ouders zien in elke vrouw en man

III

‘t is klaar, we zijn van eender hout

gul naar elkaar, geuren en kleuren,

doen wij onze en zij hun verhalen

van verliefd, verloofd, getrouwd

van vloeiend door het leven glijden

tot ergens blijven steken in de pijn

hoor, wij praten uit dezelfde mond

dit is een grafsteen voor ons beiden

IV

straks als de tand des tijds ons lijf

vermaalt en wij elkaar omarmen

onder deze stenen; zullen we dan

wat zingen, zomaar uit tijdverdrijf?

in paradisum met zijn allen samen

in paradisum nos angeli, zij en wij,

tot onze zang het donker breekt en

er licht zal zijn in eeuwigheid amen

© 2012 JACE van de Ven

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Ven, Jace van de

J.A. Woolf: Making memories (#31)

kempis.nl poetry magazine 2012

More in: FLUXUS LEGACY, J.A. Woolf, Visual & Concrete Poetry, ZERO art

Eugene Field

(1850-1895)

LITTLE BOY BLUE

HE little toy dog is covered with dust,

But sturdy and stanch he stands;

And the little toy soldier is red with rust,

And his musket moulds in his hands.

Time was when the little toy dog was new,

And the soldier was passing fair;

And that was the time when our Little Boy Blue

Kissed them and put them there.

“Now, don’t you go till I come,” he said,

“And don’t you make any noise!”

So, toddling off to his trundle-bed,

He dreamt of the pretty toys;

And, as he was dreaming, an angel song

Awakened our Little Boy Blue–

Oh! the years are many, the years are long,

But the little toy friends are true!

Ay, faithful to Little Boy Blue they stand,

Each in the same old place,

Awaiting the touch of a little hand,

The smile of a little face;

And they wonder, as waiting the long years through

In the dust of that little chair,

What has become of our Little Boy Blue,

Since he kissed them and put them there.

“Little Boy Blue” is reprinted from The Little Book of American Poets: 1787-1900.

Ed. Jessie B. Rittenhouse. Cambridge: Riverside Press, 1915.

Eugene Field poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Field, Eugene

William Blake

(1757-1827)

A POISON TREE

Was angry with my friend:

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

And I watered it in fears,

Night and morning with my tears;

And I sunnèd it with smiles,

And with soft deceitful wiles.

And it grew both day and night,

Till it bore an apple bright;

And my foe beheld it shine,

And he knew that it was mine,

And into my garden stole,

When the night had veiled the pole:

In the morning glad I see

My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

William Blake poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blake, William

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 152

In loving thee thou know’st I am forsworn,

But thou art twice forsworn to me love swearing,

In act thy bed-vow broke and new faith torn,

In vowing new hate after new love bearing:

But why of two oaths’ breach do I accuse thee,

When I break twenty? I am perjured most,

For all my vows are oaths but to misuse thee:

And all my honest faith in thee is lost.

For I have sworn deep oaths of thy deep kindness:

Oaths of thy love, thy truth, thy constancy,

And to enlighten thee gave eyes to blindness,

Or made them swear against the thing they see.

For I have sworn thee fair: more perjured I,

To swear against the truth so foul a lie.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature