Fleurs du Mal Magazine

IJzerhard

Stalen glans op paars blad. Op hoge stelen wiegt

de ijzerhard. Middaguur in onze hortus botanicus

liegt niet: het land van gisteren is toe. Alles bloeit.

Ik hoor kinderen op een nabijgelegen schoolplein

driewerf hoera roepen. Er wordt traag gesproeid

door een man die graag bezorgd lijkt. Soms wil hij

de tuin uit hollen en het op een gillen zetten, maar

zijn bladeren houden niet van geluid. Het ruikt naar

zoethout. Een koolwitje laveert tegen wind in, en zand

wijkt zachtjes voor zaad. Wolkjes zijn licht en de goden

nabij. Laat alle mensen maar weten waar de verhalen

over gaan. Wie een grens trekt heeft een huis.

Bert Bevers

(Verschenen in Smeedwerk, Stichting Bredevoort Boekenstad, Bredevoort, lente 2007)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Louis Paul Boonparade in Aalst

Op 23 juni maakt Aalst zich op voor een heuse Boonparade, de kers op de taart van een creatieproces van een twaalftal socio-culturele verenigingen (theatergezelschap PACT, straathoekwerk, buurtsport, Aalsterse dienstencentra, fietskoerierdienst, L’Atelier…) en scholen (De Voorstad, de stedelijke Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten…) en evenveel begeleidende hedendaagse kunstenaars.

Enkele namen: Stief Desmet, Bart Lodewijks, Wouter Cox, Lucie Renneboog, Danny Cobbaut, Franck Bragigand, Olivier Bras, Francis Denys, Robin Vermeersch… Het centrale thema voor de creaties is ‘De wereld van Boon’. De optocht is een eerbetoon aan de veelkunstenaar Boon.

Vanaf de Kapellekensbaan vertrekken deze groepen onder muzikale begeleiding naar het Werfplein waar nadien verder gefeest wordt.

Er is ook een Miss Ondine verkiezing met Herman Brusselmans.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Louis Paul Boon

Iedereen kan schilderen.

(Henk & Ingrid)

http://www.henkeningrid.org/ – (de wereld volgens Henk & Ingrid)

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, The talk of the town

Museum De Pont Tilburg

De Witte Nacht

donderdagavond@depont voor één keer op zaterdag!

zaterdag 23 juni 2012, 17.00 – 23.00 uur

Iedereen is uitgenodigd voor de 20e verjaardag van De Pont: De Witte Nacht. Het belooft een waar Tilburgs feest te worden met een expositie van Tilburg CowBoys, muziek van Paul van Kemenade en het Muzekoor onder leiding van Peter van Meel en een speciale editie van Dichter bij de Kunst met stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn en haar collega’s Jeroen Geurts, Daan Taks, Jeroen Kant en Robert Proost. Verder zijn er rondleidingen op zaal en in de tuin (door stadsbioloog Gert Brunnink), workshops, dansoptredens, circusartiesten, singer-songwriters en Tai Chi-demonstraties. Om 17 uur wordt De Witte Nacht op feestelijke wijze geopend, aansluitend speelt Paul van Kemenade en daarna wordt de hele avond gevuld met activiteiten. En vergeet niet: dit is de laatste kans om de tentoonstelling van Ai Weiwei te bekijken!

Het museum is geopend van 11 tot 23 uur en vanaf 17 uur gratis toegankelijk. Het De Pont café, Heet Brood en de Kippenkar zorgen voor lekker eten en drinken. Singer-songwriter Janneke Peeters maakt het verblijf in het museum-cafe nog aangenamer met haar kleine, fijne, soms vieze liedjes.

Tilburg CowBoys hebben een lange geschiedenis met voorwerpen en toegevoegde waardes. Het gaat altijd over de verhalen achter de spullen: dat was het geval bij de Spullenprocessie in 2008 in de wijk Jeruzalem, of bij het Herinneringen Netwerk Brabant, Deel Mee!, tot de sterke verhalen wedstrijd in café De Worm. Voor De Pont hebben ze als Taxateurs Emotionele Waarde een mooie expositie samengesteld uit spullen die op de Meimarkt ingekocht zijn. U kunt de voorwerpen tijdens De Witte Nacht kopen, maar dan wel met de Toegevoegde Waarde van het verhaal, dat achter deze spullen ligt.

Humade: De zussen Gieke en Lotte, beiden vormgever, hebben een oude Japanse techniek aangepast om gebroken serviesgoed met hoge Emotioneel Toegevoegde Waarde weer met goud aan elkaar te lijmen. Neem tijdens De Witte Nacht uw gebroken vaas, of kop en schotel mee en doe mee met de workshop “lijm je herinnering met een gouden randje”.

Paul van Kemenade i.s.m. November Music: Een muzikale held op altsaxofoon. Zijn relatie met Tilburg is intens: Hij heeft hier gestudeerd en stond aan de wieg van Paradox. Op dit moment maakt hij o.a. deel uit van zijn eigen Paul van Kemenade quintet. In 2000 ontving Van Kemenade de prestigieuze Boy Edgar prijs voor zijn bijdrage aan de Nederlandse jazzmuziek.

Dichter bij de kunst: Stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn nodigt Daan Taks, Jeroen Geurts, Robert Proost en Jeroen Kant uit om voor een werk uit de vaste collectie van De Pont een gedicht of lied te maken. Bezie de kunst van De Pont eens door deze poëtische ogen!

Dansgroep Bach 3: Deze studenten van Fontys dansacademie brengen de dansvoorstelling ”Als de man van huis is, dansen de huisvrouwen op tafel”. Het zal u niet verbazen dat deze choreografie zich op en rondom een tafel in de tuin zal afspelen.

Muziektheater: Het Muzekoor (onder leiding van Peter van Meel) heeft speciaal voor De Witte Nacht een stuk gemaakt, De Elementen, met liederen van o.a. Arvo Pärt en Allegri. De Pont heeft dus de primeur!

Klassiek zangeres: Anita van de Kamp heeft zich laten inspireren door beeldend werk van Giuseppe Penone. Zij zingt liederen uit de Romantische periode van Bellini. Pianist Ruud Verbunt, begeleidt Anita tijdens haar optredens.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Ai Weiwei, FDM Art Gallery, The talk of the town

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (20)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926. The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK IV

3

A parenthesis. Yes, another. The things that I am obliged to do all day long, I do not speak of them; the beastlinesses that I have to serve up all day long as food for this black spider on its tripod, which eats and is never filled, I do not speak of them; beastlinesses incarnate in these actors and actresses, in all the people who are driven by necessity to feed this machine upon their own modesty, their own dignity, I do not speak of them; I must, all the same, have a little breathing-space, now and again, absolutely, draw a mouthful of air for my superfluity; or die. I am interested in the history of this woman, the Nestoroff I mean; I have filled with it many pages of these notes; but I do not, for all that, intend to be carried away by her history; I intend her, the lady, to remain in front of my machine, or rather I intend myself to remain in front of her what I am to her, an operator, and nothing more.

When my friend Simone Pau has failed for some days in succession to pay me a visit at the Kosmograph, I go myself in the evening to visit him in Borgo Pio, at his Falcon Hostelry.

The reason why, for some days, he has not come to see me, is the saddest imaginable. The man with the violin is dying.

I found keeping watch in the room set apart for Pau in the Shelter, Pa’u himself, his aged colleague, the pensioner of the Papal Government, and the three old spinster schoolmistresses, friends of the Sisters of Charity. On Simone Pau’s bed, with an ice-pack on his head, lay the man with the violin, struck down three evenings ago by an apoplectic stroke.

“He is freeing himself,” Simone Pau said to me, with a wave of his hand, by way of comfort. “Sit down here, Serafino. Science has placed on his head that cap of ice, which is completely useless. We are helping him to pass away amid serene philosophic discussions, in return for the precious gift which he leaves as an heirloom to us: his violin. Sit down, man, sit here. They have washed him thoroughly, all over; they have put him in order with the sacraments; they have anointed him. Now we are waiting for the end, which cannot be far distant. You remember when he played before the tiger? It made him ill. But perhaps it is better so: he is gaining his freedom!”

How genially the old man smiled at these words, sitting there so clean and neat, with his cap on his head and the bone snuff-box in his hand with the portrait of the Holy Father on the lid!

“Continue,” Simone Pau went on, turning to the old man, “continue, Signor Cesarino, your panegyric of the three-wicked oil-lamps, please.”

“Panegyric indeed!” exclaimed Signor Cesarino. “You insist that I am making a panegyric of them! I tell you that they belong to that generation, that is all.”

“And is not that a panegyric!”

“Why, no; I say that it all comes to the same thing in the end: it is an idea of mine: so many things I used to see in the dark with those lamps, which, you are perhaps unable to see by electric light; but then, on the other hand, you see other things with these lights here which I fail to see; because four generations of lights, four, my dear Professor, oil, paraffin, gas and electricity, in the course of sixty years, eh… eh… eh… it’s too much, you know? and it’s bad for our eyesight, and for our heads too; yes, it’s bad for the head too, it is.”

The three old maids, who were sitting, all three of them, with their hands, in thread mittens, quietly folded in their laps, shewed their approval by nodding silently with their heads: yes, yes, yes.

“Light, a fine light, I don’t say it isn’t! Eh, but I know it is,” sighed the old man, “I can remember when you went about with a lantern in your hand, so as not to break your neck. But light for outside, that’s what it is…. Does it help us to see better indoors? No.”

The three quiet old maids, still keeping their hands, in their thread mittens, folded in their laps, agreed in silence, with their heads: no, no, no.

The old man rose and offered those pure and peaceful hands the reward of a pinch of snuff. Simone Pau held out two fingers.

“You too?” the old man asked him.

“I too, I too,” answered Simone Pau, slightly irritated by the question. “And you too, Serafino. Take it, I tell you! Don’t you see that it is a rite?”

The little old man, with the pinch between his fingers, shut one eye wickedly:

“Contraband tobacco,” he said softly. “It comes from over there….”

And with the thumb of his other hand he made a furtive sign, as though to say: “Saint Peter’s, Vatican.”

“You understand?” Simone Pau turned to me, thrusting his pinch out before my eyes. “It sets you free from Italy! Does that seem to you nothing? You snuff it, and you no longer smell the stench of the Kingdom!”

“Come, come, do not say that…” the little old man pleaded in distress, for he wished to enjoy in peace the benefits of toleration, by tolerating others.

“It is I who say it, not you,” replied Simone Pau. “I say it, who have a right to say it. If you said it, I should ask you not to say it in my presence, is that all right? But you are a wise man, Signor Cesarino! Go on, go on, please, describing to us, with your courtly, old-fashioned grace, the good old oil-lamps, with three wicks, of days gone by… I saw one, do you know, in Beethoven’s house, at Bonn on the Rhine, when I was travelling in Germany. There, this evening we must recall the memory of all the good old things, round this poor violin, shattered by an automatic piano. I confess that I am not over pleased to see my friend in the room here, at such a moment. Yes, you, Serafino. My friend, ladies and gentlemen–let me introduce him to you: Serafino Gubbio–is an operator: poor fellow, he turns the handle of a cinematograph machine.”

“Ah,” said the little old man, with a note of pleasure.

And the three old maids gazed at me in admiration.

“You see?” Simone Pau said to me. “You spoil everything with your presence here. I wager that you now, Signor Cesarino, and you too, ladies, have a burning desire to learn from my friend how the machine works, and how a film is made. But for pity’s sake!”

And he pointed to the dying man, who was breathing heavily in a profound coma under the ice-pack.

“You know that I…” I attempted to put in, quietly.

“I know!” he interrupted me. “You do not enter into your profession, but that does not mean, my dear fellow, that your profession does not enter into you! Try to disabuse these colleagues of mine of the idea that I am a professor. I am the Professor, for them: a trifle eccentric, but still a professor! We may easily fail to recognise ourselves in what we do, but what we do, my dear fellow, remains done: an action which circumscribes you, my dear fellow, gives you a form of sorts, and imprisons you in it. Do you seek to rebel? You cannot. In

the first place, we are not free to do as we wish: the age we live in,

the habits of other people, our means, the conditions of our existence, ever so many other reasons, outside and inside us, compel us often to do what we do not wish; and then, the spirit is not detached from the flesh; and the flesh, however closely you guard it, has a will of its own. And what is our intelligence worth, if it does not feel compassion for the beast that is within us? I do not say excuse it. The intelligence that excuses the beast, bestialises itself as well. But to feel pity for it is another matter! Christ preached it; am I not right, Signor Cesarino? So you are the prisoner of what you have done, of the form that your actions have given you. Duties, responsibilities, a chain of consequences, coils, tentacles which are wound about you, and do not leave you room to breathe. You must do nothing more, or as little as possible, like me, so as to remain as free as possible? Ah, yes! Life itself is an action! When your father brought you into the world, my dear fellow, the deed was done. You can never free yourself again until you end by dying. And not even after your death, Signor Cesarino here will tell you, eh? He never frees himself again, eh? Not even after death. Keep calm, my dear fellow. You will go on turning the handle of your machine even beyond the grave! But yes, yes, because it is not for your being, for which you are not to blame, but for your actions and the consequences of your actions that you have to answer, am I not right, Signor Cesarino?”

“Quite right, yes; but it is not a sin, Professor, to turn the handle of a cinematograph machine,” Signor Cesarino observed.

“Not a sin? You ask him!” said Pau.

The little old man and the three old maids gazed at me stupefied and dismayed to see me assent with a nod of my head, smiling, to Simone Pau’s verdict.

I smiled because I was picturing myself in the presence of the Creator, in the presence of the Angels and of the blessed souls in Paradise standing behind my great black spider on its knock-kneed tripod, condemned to turn the handle, in the next world also, after my death.

“Why, of course,” sighed the little old man, “when the cinematograph represents certain indecencies, certain stupid scenes….”

The three old maids, with lowered eyes, made a sign of outraged modesty with their hands.

“But this gentleman would not be responsible for it,” Signor Cesarino hastened to add, courteous and still friendly.

There came from the staircase a sound of sweeping garments and of the heavy beads of a rosary with a dangling crucifix. There appeared, under the broad white wings of her coif, a Sister of Charity. Who had sent for her? The fact remains that, as soon as she appeared on the threshold, the dying man ceased to breathe. And she was quite ready to perform the last duties. She lifted the ice-pack from his head; turned to look at us, in silence, with a simple, rapid movement of her eyes towards the ceiling; then stooped to arrange the deathbed and fell on her knees. The three old maids and Signor Cesarino followed her example. Simone Pau summoned me from the room.

“Count,” he bade me, as we began to go downstairs, pointing to the steps. “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine. The steps of a stair; of this stair, which ends in this dark passage…. The hands that hewed them, and placed them here, one upon another…. Dead. The hands that erected this building…. Dead. Like other hands, which erected all the other houses in this quarter…. Rome; what do you think of it? A great city…. Think of this little earth in the firmament…. Do you see? What is it?… A man has died…. Myself, yourself … no matter: a man…. And five people, in there, have gone on their knees round him to pray to some one, to something, which they believe to be outside and over everything and everyone, and not in themselves, a sentiment of theirs which rises independent of their judgment and invokes that same pity which they hope to receive themselves, and it brings them comfort and peace. Well, people must

act like that. You and I, who cannot act thus, are a pair of fools. Because, in saying these stupid things that I am now saying, we are doing the same thing, on our feet, uncomfortably, with only this result for our trouble, that we derive from it neither comfort nor peace. And fools like us are all those who seek God within themselves and despise Him without, who fail, that is to say, to see the value of the actions, of all the actions, even the most worthless, which man has performed since the world began, always the same, however different they may appear. Different, forsooth? Different because we credit them with another value, which, in any event, is arbitrary. We know nothing for certain. And there is nothing to be known beyond that which, in one way or another, is represented outwardly, in actions. Within is torment and weariness. Go, go and turn your handle, Serafino! Be assured that yours is a profession to be envied! And do not regard as more stupid than any others the actions that are arranged before your eyes, to be taken by your machine. They are all stupid in the same way, always: life is all a mass of stupidity, always, because it never comes to an end and can never come to an end. Go, my dear fellow, go and turn your handle, and leave me to go and sleep with the wisdom which, by always sleeping, dogs shew us. Good night.”

I came away from the Shelter, comforted. Philosophy is like religion: it is always comforting, even when it is a philosophy of despair, because it is born of the need to overcome a torment, and even when it does not overcome it, the action of setting that torment before our eyes is already a relief, inasmuch as, for a while at least, we no longer feel it within us. The comfort I derived from Simone Pau’s words had come to me, however, principally from what he had said with regard to my profession.

Enviable, yes, perhaps; but if it were applied to the recording, without any stupid invention or imaginary construction of scenes and actions, of life, life as it comes, without selection and without any plan; the actions of life as they are performed without a thought, when people are alive and do not know that a machine is lurking in concealment to surprise them. Who knows how ridiculous they would appear to us! Most of all, ourselves. We should not recognise ourselves, at first; we should exclaim, shocked, mortified, indignant: “What? I, like that? I, that person? Do I walk like that? Do I laugh like that? Is that my action? My face?” Ah, no, my friend, not you: your haste, your wish to do this or that, your impatience, your frenzy, your anger, your joy, your grief…. How can you know, you who have them within you, in what manner all these things are represented outwardly? A man who is alive, when he is alive, does not see himself: he lives…. To see how one lived would indeed be a ridiculous spectacle!

Ah, if my profession were destined to this end only! If it had the sole object of presenting to men the ridiculous spectacle of their heedless actions, an immediate view of their passions, of their life as it is. Of this life without rest, which never comes to an end.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (20)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

![]()

Ellen Deckwitz wint C. Buddingh’-prijs 2012

Dichter, performancekunstenaar en literatuurwetenschapper Ellen Deckwitz wint de C. Buddingh’-prijs 2012. De jury van de vijfentwinstigste editie van de C. Buddingh’-prijs bekroonde haar debuutbundel De steen vreest mij als het beste Nederlandstalige poëziedebuut van het afgelopen jaar. Deckwitz ontving de prijs donderdag 14 juni j.l. tijdens een spannend uitreikingsprogramma op het 43e Poetry International Festival Rotterdam. De jury noemt De steen vreest mij van Deckwitz ‘de bundel die het meest verbluft deed staan en het meest het gevoel gaf niet alleen grote kwaliteit te bekronen maar ook een grote belofte te erkennen en bevestigen.’ Ook de debuten van Max Temmerman, Michaël Vandebril en Jeroen Mettes waren genomineerd. Aan de C. Buddingh’-prijs is een bedrag van € 1.200,- verbonden.

Uit het juryrapport: ‘De steen vreest mij van Ellen Deckwitz is de hechtst gecomponeerde bundel. Een verhaallijn, die we hier niet gaan verklappen, houdt de bundel samen. Op het onheilszwangere begin volgt een uitdieping van de personages, een gezin met een ik, een broer, een moeder en een grootvader. Wanneer dan aan het eind de plot zich ontrolt, geeft die uitdieping hem zijn volle morele complexiteit mee: ‘Ik bleef nog heel lang bij/ de rand. Mijn rug jeukte, ik dacht/ nu komen vast mijn vleugels door.’

Deckwitz houdt van begin tot eind haar taal in de hand. Elk gebruikt beeld is een toevoeging. Beelden worden herhaald, waardoor ze een grotere eenheid bewerkstelligen. We zien de zoektocht van een puber naar een eigen identiteit ontsporen met een taalbeheersing die zelf tot in het laatste detail, tot in de licht kantelende typografie toe, ons als lezer op de rails houdt en ons aan het einde beloont met de nodige morele vragen.’

Hij neemt me op schoot, vertelt

over onze soort, de Hades in de aderen

die alles schoonwoedt. Het gat tussen

zijn ogen dat zich vol met inkt zuigt

dat zich sluit. Ik kruip tegen hem aan,

hij knikt, gelooft niet

dat er in een ballpointpunt

ook een kogel zit.

(Uit: De steen vreest mij)

Ellen Deckwitz (1982) studeerde Literatuur- en Cultuurwetenschap en publiceerde in onder meer Bunker Hill, Dietsche Warande & Belfort en de bloemlezing Ik ben een bijl. In 2009 kreeg ze de Meander Dichtprijs toegekend en won ze het NK Poetry Slam. Deckwitz leeft van haar schrijverschap.

De nieuwe bundel Ha, feest van Ellen Deckwitz verschijnt begin september bij Nijgh & Van Ditmar.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Poetry International

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 131

Thou art as tyrannous, so as thou art,

As those whose beauties proudly make them cruel;

For well thou know’st to my dear doting heart

Thou art the fairest and most precious jewel.

Yet in good faith some say that thee behold,

Thy face hath not the power to make love groan;

To say they err, I dare not be so bold,

Although I swear it to my self alone.

And to be sure that is not false I swear,

A thousand groans but thinking on thy face,

One on another’s neck do witness bear

Thy black is fairest in my judgment’s place.

In nothing art thou black save in thy deeds,

And thence this slander as I think proceeds.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal

(1829-1862)

The Passing of Love

O God, forgive me that I ranged

My live into a dream of love!

Will tears of anguish never wash

The passion from my blood?

Love kept my heart in a song of joy,

My pulses quivered to the tune;

The coldest blasts of winter blew

Upon me like sweet airs in June.

Love floated on the mists of morn

And rested on the sunset’s rays;

He calmed the thunder of the storm

And lighted all my ways.

Love held me joyful through the day

And dreaming ever through the night;

No evil thing could come to me,

My spirit was so light.

O Heaven help my foolish heart

Which heeded not the passing time

That dragged my idol from its place

And shattered all its shrine.

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal poems

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Lizzy Siddal, Siddal, Lizzy

Nick J. Swarth

Wachten als die jongens

Over de nacht het volgende

Je hoort de lift naar beneden gaan, jij wel ja, jij wel

Is die lamp nu alweer kapot?

Dat die blanken ophouden met dansen

Of met hun baarden

Hou op met je baard, blanke lul

Ben jij de bouwer van die monumentale gebouwen?

Hun taal laat je in de steek

Je kunt die hal maar beter aanvegen IEDREEN RUIT!

RUIT!

Ik ga toch ook niet van dat vuilnis zitten eten

IJzige Herbert doet zijn ronde, de herder aan de riem

krabt kwispelend zijn buik KOMMA fikkie KOMMA

Geprevel bij de bus

Wijn op de muur

En weer die baarden, die snorren, die pijp

Een doorgaande camion zonder vracht BILLBOARDS

en dag aan dag een vlag, gewikkeld om de mast

Over die tunnel het volgende HIJ IS LEEG

Over de trap LEEG over het perron IK WOU

DAT IK DAT KON wachten als die jongens (op wat

komen gaat

stoïcijns stommetje spelend, bukshag bietsend (!) (van

elkaar.

(uit: Nick J. Swarth: MIJN ONSTERFELIJKE LEVER. Gedichten & tekeningen. Uitgeverij IJzer, Utrecht | 2012. ISBN 978 90 8684 086 1 – NUR 305 – Paperback, 64 blz. Prijs: € 10 – Zie voor meer informatie: www.swarth.nl )

Nick J. Swarth poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swarth, Nick J.

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Alles still

Alles still! Es tanzt den Reigen

Mondenstrahl im Wald und Flur,

Und darüber thront das Schweigen

Und der Winterhimmel nur.

Alles still! Vergeblich lauschet

Man der Krähe heisrem Schrei,

Keiner Fichte Wipfel rauschet

Und kein Bächlein summt vorbei.

Alles still! Die Dorfes-Hütten

Sind wie Gräber anzusehen,

Die, von Schnee bedeckt, inmitten

Eines weiten Friedhofs stehn.

Alles still! Nichts hör ich klopfen

Als mein Herz durch die Nacht; –

Heiße Tränen niedertropfen

Auf die kalte Winterpracht.

nach oben!

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

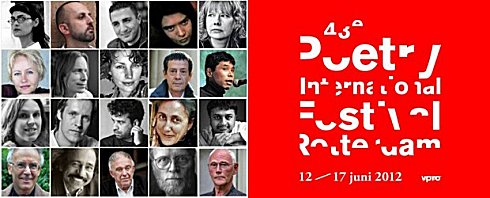

43e Poetry International Festival Rotterdam

12-17 juni, Schouwburg Rotterdam

“Elk woord verandert als het wordt gesproken”. Het Poetry International Festival Rotterdam is voor het 43e jaar op rij het feestelijke podium voor poëzie uit de hele wereld. De klank van de dichters live, hun gedreven, inspirerende kijk op de actualiteit, het leven en de wereld, de kracht en de schoonheid van de taal en de ontmoeting tussen de vele wereldtalen en culturen zorgen voor een grote rijkdom aan poëzie.

Ontdek het wonder van taal:

“Elk woord verandert als het wordt gesproken” (Stanley Moss, Poetry International Festival 1995)

“Over hoe dit gedicht gaat eindigen valt vooralsnog niets te zeggen” (Matei Vis,niec, Poetry International Festival 2005)

Wanneer is poëzie af en wanneer nog niet? Net als Schuberts Unvollendete blijven ook gedichten soms onaf. Ongewild, door de voortijdige dood van de dichter bijvoorbeeld, of met opzet, via een literaire truc. Wat gebeurt er met het onvoltooide gedicht? En is onvoltooid werkelijk onvoltooid? En is het nu de dichter of de lezer die bepaalt wanneer een gedicht af is? Over deze vragen gaat het in de speciale festivalprogramma’s, o.a. aan de hand van de fragmentarisch overgeleverde gedichten van Sappho, het niet-geschreven werk van Friederike Mayröcker, de literaire ruimte van Maurice Blanchot en het laatste gedicht van Samuel Beckett.

Poetry Actief: Zelf schrijven? Hoe te lezen? Vertalen? Poetry International laat het je graag allemaal zelf doen tijdens Masterclasses Poëzie schrijven en Poëzie lezen, in vertaalworkshops, een Rengasessie en doorfluisteringen.

Language & Art Gallery Tour 2012: Sinds 2004 hebben meer dan 150 kunstenaars het poetrypubliek verrast met hun werk op het snijvlak van taal en beeldende kunst. Onder hen Joseph Kosuth, Lawrence Weiner, John Körmeling en Jenny Holzer. De Language & Art Gallery Tour neemt u de hele maand juni mee langs Rotterdamse galeries voor een tocht langs intensieve versmeltingen van taal en kunst. De officiële opening van de Tour vindt op zondag 10 juni om 11.00 uur tijdens een feestelijk ontbijt plaats in het Centrum Beeldende Kunst Rotterdam.

Festival dichters: Sascha Aurora Akhtar • Vahe Arsen • Najwan Darwish • Dolores Dorantes • Ulrike Draesner • Olli Heikkonen • L.K. Holt • Hédi Kaddour • Marije Langelaar • Jan Lauwereyns • Márcio-André • Chus Pato • Tomaž Šalamun • K. Satchidanandan • K. Schippers • Ron Silliman • Karen Solie • Inuo Taguchi • Umar Timol • B. Zwaal

≡ website poetry international festival 2012

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Poetry International, The talk of the town

In Memoriam Anton (Toon) Eijkens

(1920-2012)

Anton Eijkens schreef de Tilburgse historie in 1000 dichtregels

TILBURG – In het verzorgingshuis Koningsvoorde is afgelopen zaterdagochtend Antonius Maria Eijkens overleden. Toon Eijkens heeft diverse boeken op zijn naam staan en schreef ook de Tilburgse rijmkroniek die burgemeester Jan van de Mortel in 1946 bij zijn afscheid aangeboden kreeg van de Tilburgse bevolking. Het beschrijft de geschiedenis van Tilburg in duizend dichtregels.

Eijkens werd in 1920 te Tilburg geboren en volgde het gymnasium op het St. Odulphuslyceum waar hij zich al vroeg ontpopte als een jongeman met talent voor taal en muziek én als dichter. Zijn vader vond een baan voor hem bij Bureau Van Spaendonck. Het stond zijn literaire ambities niet in de weg. Onder de naam Anton Eijkens schreef hij artikelen en verhalen in de bladen Brabantia Nostra en Edele Brabant, waar hij ook in de redactie zat.

In 1946 beleefde Anton Eijkens zijn productiefste jaar. Hij publiceerde toen onder meer de verhalenbundel Rond de toren, de bloemlezing De Sprookjeshoorn en Een handvol verzen. Bovendien schreef hij samen met Jan Naaijkens het scenario en de teksten voor het massale openluchtspel Kruis en Ploeg dat in de zomer van 1946 bij gelegenheid van het 50-jarig bestaan van de Noord-Brabantse Christelijke Boerenbond (NBC) opgevoerd werd in het Willem II-stadion. Kort erna werd aan burgemeester Van de Mortel het gedenkboek Rijmkroniek van Tilburg, het hart van Brabant aangeboden, een uniek in kalfsleer gebonden boek waarvan de door Eijkens geschreven tekst geheel gekalligrafeerd was door zijn zwager Kees Mandos.

Ook in de daarop volgende jaren bleef Eijkens actief als schrijver, zij het vooral van gelegenheidsliederen voor zijn collega’s en van gedenkboeken voor het bedrijfsleven en voor Bureau Van Spaendonck zelf. Daar nam hij in 1984 afscheid als secretaris van diverse werkgeversorganisaties en directeur van de Sector Secretariaten.

Toon Eijkens was getrouwd met Thea Mandos met wie hij zeven kinderen kreeg. In 1982 werd hij geridderd in de Orde van Oranje Nassau.

Anton Eijkens

(1920-2012)

Voor de Beminde

Mijn liederen zijn gering als schaamle kinderen,

die voor een aalmoes komen zingen aan je raam,

als ‘t daglicht in de straat begint te minderen

en aan de avondlucht de eerste sterren staan.

Wie zal mij in mijn schamelheid verhinderen

mijn leed en vreugd te komen zingen aan je raam?

Ik weet: jij kunt het lied van schaamle kinderen

niet zonder mildheid langs je venster laten gaan.

Ontmoeting

Ik had maar de kortste weg genomen,

een weg vol distels en woekerkruid,

want de avond viel dichter in de bomen

en de wind blies langzaam de sterren uit.

Maar aan de rand van een bloeiende tuin,

geurend van appels, pruimen en peren,

blies een bultenaar op zijn kranke bazuin;

“Kunt gij het geluk uw rug toekeren?”

Hoe vreemd: teruggaand heb ik genomen

de langste weg, langs de hoogste bomen.

Anton Eijkens: Twee gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Eijkens, Anton, In Memoriam

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature