Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Menno ter Braak

(1902-1940)

De wereld van de dans II

De zon is niet andermaal ondergegaan, zonder Christiaan met haar avondlijke stralen als een overtuigd aanhanger des burgemeesters beschenen te hebben. Na een ellendige nacht verrees hij van zijn simplistische sponde, die des daags geen sponde is. Hij wies zich nog nauwkeuriger dan anders en beschouwde somber zijn vaal gelaat, dat zich weer zou moeten spiegelen in de zotternij der wereld.

Want het noodlot had van Christiaan een wilskrachtige gemaakt. Hij behoorde niet tot de wilskrachtigen, die hun wil verkrachten, omdat zij niets krachtig willen.

Christiaan’s willen was zeer positief; dus zou hij zien, wat de sabbatviering hero onthouden had. En bovendien was hij Foxtrot-kampioen van zijn zeer nette dansclub.

Christiaan maakte zich wederom op. Met aangename verwondering ontdekte hij aan de ingang van het meergemelde Concertgebouw, dat de heer Reese ditmaal geen toegangsgift van hem verlangde. Binnentredend ontvouwde zich voor hem een nieuw schouwspel. Met fluwelen ketenen was een beschaafde arena afgebakend. Een aantal twijfelachtige personen, waarvan Christiaan de portée niet kon vatten, huisden aarzelend om dit tournooiveld, als zwakke ridders ener kwalijk riekende cultuur. Aan twee zijden van dit krijt troonden orkesten in die bepaalde languissanie houding van zwijgende lieden, wier roeping het is rumoerig geluid voort te brengen…

Een man met bleke kaken en brandende ogen betrad het strijdperk en hield een toespraak; dit was de heraut, die de aanvang verkondigde. Klanken loeiden op, violen draalden syncopen, trompetgeschal plonsde tussen de laffe horde, waarvan geen de eerste waagde te zijn. Dwaze lachjes. Nodende wenken. Op, gij lummels!…

Een gevoel van lichte misselijkheid schroefde plotseling Christiaan’s sherry-slikkend keelgat toe. Het was die onpasselijkheid, die iemand bekruipt, wanneer een medicus zijn vak bespreekt aan een fijn diner, of Henri Wallig als tartaars student vermomd in Tuschinsky het Io Vivat laat schallen. Deze onpasselijkheid is als een moroze regenmorgen, een druilende kakatoe met hangende vederen, zij heeft kop noch staart…

Zoals gezegd, Christiaan zat in een nette dansclub met introductie. Hij meende het dansen te kennen en hij werd ontgoocheld. Zelden is ontgoocheling bitterder geweest. Zelden is een burgemeester schitterender gerehabiliteerd. Maar hij, Christiaan, hing mistroostig op zijn stoel en bemerkte niet, dat een onhebbelijke kelner hem een tweede bestelling wilde aansmeren. Voor zijn ogen dwarrelde het gore ras, dat ten ondergang gedoemd is. En somber sprak hij tot zichzelf:

‘U, burgervader, roem ik hier, U en Uw beginselen, door een danslustige Raad bespot. Liever wat goedmoedige burgerlijkheid dan deze ontteugeling van wat zich in Amsterdam aan onverfijnde driften tot op heden schuil hield. Liever een slecht zittend jacquet met één knoop te veel, dan deze naar de schouders verplaatste mannentailles. Liever verzadigde, ronduit hersenloze vrouwengezichten dan deze starre muizensnuiten. Liever…

Hier werd Christiaan onderbroken door de kelner, die het prevelen zijner lippen voor een bede om afrekening aanzag. Uit pure ergernis gaf hij 5 cts. te veel fooi, waarvoor hij in zijn jas gehesen werd.

Diezelfde avond schreef hij een studie De Tragiek van den Dans, opgedragen aan de burgemeester van Amsterdam; waarin hij er de nadruk op legde, dat ‘tragiek’ samenhangt met ‘tragos’ = bok.

Propria Cures 31 mei 1924

Menno ter Braak: De wereld van de dans II

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Menno ter Braak

Vroeger wordt alles beter.

Henk & Ingrid

http://www.henkeningrid.org/

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, The talk of the town

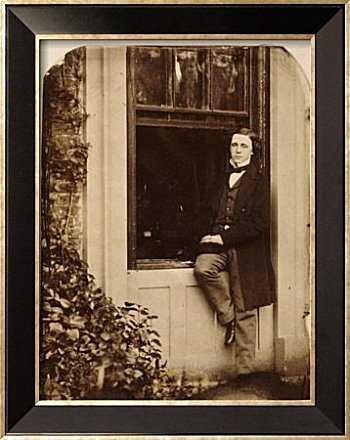

Lewis Carroll

(1832-1898)

Poeta Fit, Non Nascitur

“How shall I be a poet?

How shall I write in rhyme?

You told me once `the very wish

Partook of the sublime.’

The tell me how! Don’t put me off

With your `another time’!”

The old man smiled to see him,

To hear his sudden sally;

He liked the lad to speak his mind

Enthusiastically;

And thought “There’s no hum-drum in him,

Nor any shilly-shally.”

“And would you be a poet

Before you’ve been to school?

Ah, well! I hardly thought you

So absolute a fool.

First learn to be spasmodic —

A very simple rule.

“For first you write a sentence,

And then you chop it small;

Then mix the bits, and sort them out

Just as they chance to fall:

The order of the phrases makes

No difference at all.

`Then, if you’d be impressive,

Remember what I say,

That abstract qualities begin

With capitals alway:

The True, the Good, the Beautiful —

Those are the things that pay!

“Next, when we are describing

A shape, or sound, or tint;

Don’t state the matter plainly,

But put it in a hint;

And learn to look at all things

With a sort of mental squint.”

“For instance, if I wished, Sir,

Of mutton-pies to tell,

Should I say `dreams of fleecy flocks

Pent in a wheaten cell’?”

“Why, yes,” the old man said: “that phrase

Would answer very well.

“Then fourthly, there are epithets

That suit with any word —

As well as Harvey’s Reading Sauce

With fish, or flesh, or bird —

Of these, `wild,’ `lonely,’ `weary,’ `strange,’

Are much to be preferred.”

“And will it do, O will it do

To take them in a lump —

As `the wild man went his weary way

To a strange and lonely pump’?”

“Nay, nay! You must not hastily

To such conclusions jump.

“Such epithets, like pepper,

Give zest to what you write;

And, if you strew them sparely,

They whet the appetite:

But if you lay them on too thick,

You spoil the matter quite!

“Last, as to the arrangement:

Your reader, you should show him,

Must take what information he

Can get, and look for no im

mature disclosure of the drift

And purpose of your poem.

“Therefore to test his patience —

How much he can endure —

Mention no places, names, or dates,

And evermore be sure

Throughout the poem to be found

Consistently obscure.

“First fix upon the limit

To which it shall extend:

Then fill it up with `Padding’

(Beg some of any friend)

Your great SENSATION-STANZA

You place towards the end.”

“And what is a Sensation,

Grandfather, tell me, pray?

I think I never heard the word

So used before to-day:

Be kind enough to mention one

`Exempli gratiâ'”

And the old man, looking sadly

Across the garden-lawn,

Where here and there a dew-drop

Yet glittered in the dawn,

Said “Go to the Adelphi,

And see the `Colleen Bawn.’

“The word is due to Boucicault —

The theory is his,

Where Life becomes a Spasm,

And History a Whiz:

If that is not Sensation,

I don’t know what it is,

“Now try your hand, ere Fancy

Have lost its present glow —”

“And then,” his grandson added,

“We’ll publish it, you know:

Green cloth — gold-lettered at the back —

In duodecimo!”

Then proudly smiled that old man

To see the eager lad

Rush madly for his pen and ink

And for his blotting-pad —

But, when he thought of publishing,

His face grew stern and sad.

Lewis Carroll poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Carroll, Lewis

Menno ter Braak

(1902-1940)

De wereld van de dans I

Gedurende één etmaal is Christiaan zeer vertoornd geweest op de burgemeester van Amsterdam. Hij was steeds een voorstander van dansen geweest en verstond de kunst ook voortreffelijk. Wie zijn rank lichaam in lijnen van geleidelijkheid door een danszaal zag zwalpen, admireerde hem, wijl hij volgens het laatste Londense congres danste. Vrouwenogen hingen aan zijn welgesneden smoking, wanneer hij tussen Foxtrot en Blues keuvelend tussen de schonen rondwandelde. Men fluisterde van hem, dat hij gezworen had, zijn uitverkorene op een bal te leren kennen en anders ongehuwd te blijven maar dit is vuige laster en spruit voort uit Christiaan’s afkeer van de echtelijke staat.

Christiaan dan had vernomen, dat het dansen voortaan geen Privatsache meer zou zijn, maar een gemeenschapsbelang. Wijl hij het geld miste, om in Trianon of in Réserve een duur souper te nuttigen, maakte hij zich op naar het Concertgebouw Mille-Colonnes. Niet dan met weerzin en walging maakte hij zich op. Al te goed wist hij, welk een smet van burgerlijkheid zijn goede naam zou aankleven, wanneer men hem daar alleen signaleerde. Maar hij maakte zich op.

Christiaan betaalde aan de kassa ƒ 0.25. Daarna trad hij binnen en monsterde de zaal. Het gelukte hem niet enige verandering te bespeuren. Een zee van volvette hoofden deinde voor zijn blikken. Een specialiteit haalde zeep uit een hawaian-gitaar. Er werd vruchtenijs gegeten.

Christiaan bestelde een biertje en informeerde schuchter bij kelner No. 27, waarvan op zijn tafeltje stond dat hij serveerde, naar het dansen.

‘Het is zondag, meneer’, antwoorde No. 27…

… Nog drie kwartier bleef Christiaan zitten, argwanend rondspeurend, of hij geen kennissen zag. Hij dronk zijn biertje uit en loerde naar een gemene danseres. Hij peinsde over het dualisme in een burgemeesterlijke ziel, zodat No. 27 over zijn achteloos vastgeklemde wandelstok struikelde. Hij overwoog een adres aan de Raad, om op zondag religieuze dansen toe te laten.

Bij de uitgang zag hij twee boezemvrienden, die hij verloochende.

(wordt vervolgd)

Propria Cures 24 mei 1924

Menno ter Braak: De wereld van de dans I

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Menno ter Braak

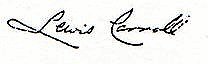

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Snake

A snake came to my water-trough

On a hot, hot day, and I in pyjamas for the heat,

To drink there.

In the deep, strange-scented shade of the great dark carob-tree

I came down the steps with my pitcher

And must wait, must stand and wait, for there he was at the trough before

me.

He reached down from a fissure in the earth-wall in the gloom

And trailed his yellow-brown slackness soft-bellied down, over the edge of

the stone trough

And rested his throat upon the stone bottom,

i o And where the water had dripped from the tap, in a small clearness,

He sipped with his straight mouth,

Softly drank through his straight gums, into his slack long body,

Silently.

Someone was before me at my water-trough,

And I, like a second comer, waiting.

He lifted his head from his drinking, as cattle do,

And looked at me vaguely, as drinking cattle do,

And flickered his two-forked tongue from his lips, and mused a moment,

And stooped and drank a little more,

Being earth-brown, earth-golden from the burning bowels of the earth

On the day of Sicilian July, with Etna smoking.

The voice of my education said to me

He must be killed,

For in Sicily the black, black snakes are innocent, the gold are venomous.

And voices in me said, If you were a man

You would take a stick and break him now, and finish him off.

But must I confess how I liked him,

How glad I was he had come like a guest in quiet, to drink at my water-trough

And depart peaceful, pacified, and thankless,

Into the burning bowels of this earth?

Was it cowardice, that I dared not kill him?

Was it perversity, that I longed to talk to him?

Was it humility, to feel so honoured?

I felt so honoured.

And yet those voices:

If you were not afraid, you would kill him!

And truly I was afraid, I was most afraid, But even so, honoured still more

That he should seek my hospitality

From out the dark door of the secret earth.

He drank enough

And lifted his head, dreamily, as one who has drunken,

And flickered his tongue like a forked night on the air, so black,

Seeming to lick his lips,

And looked around like a god, unseeing, into the air,

And slowly turned his head,

And slowly, very slowly, as if thrice adream,

Proceeded to draw his slow length curving round

And climb again the broken bank of my wall-face.

And as he put his head into that dreadful hole,

And as he slowly drew up, snake-easing his shoulders, and entered farther,

A sort of horror, a sort of protest against his withdrawing into that horrid black hole,

Deliberately going into the blackness, and slowly drawing himself after,

Overcame me now his back was turned.

I looked round, I put down my pitcher,

I picked up a clumsy log

And threw it at the water-trough with a clatter.

I think it did not hit him,

But suddenly that part of him that was left behind convulsed in undignified haste.

Writhed like lightning, and was gone

Into the black hole, the earth-lipped fissure in the wall-front,

At which, in the intense still noon, I stared with fascination.

And immediately I regretted it.

I thought how paltry, how vulgar, what a mean act!

I despised myself and the voices of my accursed human education.

And I thought of the albatross

And I wished he would come back, my snake.

For he seemed to me again like a king,

Like a king in exile, uncrowned in the underworld,

Now due to be crowned again.

And so, I missed my chance with one of the lords

Of life.

And I have something to expiate:

A pettiness.

Taormina, 1923

D. H. Lawrence: Snake

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Heinrich von Kleist

(1777-1811)

Jünglingsklage

Winter, so weichst du,

Lieblicher Greis,

Der die Gefühle

Ruhigt zu Eis.

Nun unter Frühlings

Ueppigem Hauch

Schmelzen die Ströme –

Busen, du auch!

Heinrich von Kleist poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Heinrich von Kleist, Kleist, Heinrich von

Renée Crevel

(1900-1935)

Mais si la mort n’était qu’un mot

Orgueil ou paresse –les deux peut-être– l’intelligence à l’état de veille prétend domestiquer les énigmes. Ainsi, du temps et de l’espace, nos jours ont fait des animaux dociles. Quant aux notions de vie ou de mort qui ne se laissent guère apprivoiser, pour fuir leur angoisse essentielle (angoisse qui, d’ailleurs, me semble seule capable de donner l’indiscutable sensation d’être) chaque minute essaie quelque nouveau suicide. A qui parle de la mort ou du geste qui la peut donner, le paradoxe est facile, mais comment ne point noter que déjà fut un suicide la vie de tel ou tel. Barrès destructeur ne se détruit que le jour où, arbitrairement, il construit. Au contraire, le Romain de la décadence s’ouvrant les veines, me semble si naturel que j’ose à peine parler de suicide ; car le sénateur romain s’ouvrant les veines ne renonçait pas à lui-même mais, au contraire, avait un dernier geste logique pour s’affirmer. J’entends que les hommes intelligents, trop intelligents (c’est l’esprit critique, assassin des possibilités, qui nous tue), usent et ont raison d’user contre eux-mêmes, de la corde, du poison, du revolver, etc., tout comme les nerveux prennent du Dial Cyba le soir, avant de se coucher, pour mieux dormir. Or sommeil, dont nous disons qu’il est l’image de la mort, réserve aux esprits inquiets les douloureuses surprises des rêves. Je ne puis croire que les intelligences supérieures aux préoccupations terrestres et qui s’en voulurent à jamais délivrer aient brisé, par le geste appelé suicide, la parabole d’une ascension. Au contraire, ceux dont on constate qu’il s’étourdissent ou se tuent de travail me paraissent des faibles, car le travail, l’activité humaine, sont des stupéfiants qui n’ont même point, pour séduire, telle ou telle petite note pittoresque (bien discutable quant à sa qualité d’ailleurs) mais qu’il est impossible de n’accorder point à d’autres stupéfiants. La plupart des hommes qui marchent et respirent ne méritent guère, dans notre civilisation occidentale, l’éloge d’hommes vivants puisqu’ils ne marchent et respirent que pour éviter la compagnie de ces problèmes qui, au reste, finiront toujours par venir les reprendre au jour de leur agonie. Il me faut donc déjà conclure : le mouvement est simulacre ; il est une forme de suicide, le suicide des lâches, puisque, laissant des possibilités pour l’avenir, il calme à la fois la peur de l’au-delà et l’ennui de vivre. Mais les calculs sont toujours faux. Le mensonge de l’activité spontanément se dénonce.

Oiseaux du mystère, oiseaux qui chantez au plus silencieux de moi-même, pour vous avoir entendus après le départ des autres hommes, je sais que, seule, la solitude permet quelque espoir de vérité. Certaine sensation d’âme trop bien enracinée pour que j’en puisse triompher, me force à confondre vie et vérité. Si la mort existe (la mort que les esprits forts ont, de tout temps, assimilée au néant), elle m’apparaît illogique. Certaine forme d’activité me semblant dénuée de raison valable, nul ne s’étonnera donc de me la voir, je le répète, considérer comme une forme de la mort. L’agitation emprisonne le corps, l’intelligence. Qu’on parle de filet ou de murs, le corps et l’intelligence sont emprisonnés, voilà le fait. Volière tyrannique, sous leurs ailes, dans la captivité de plomb devenues, meurent nos oiseaux de mystère. Mais vienne la nuit. Le grillage des simulacres ne résiste plus. Vague comme un ciel et comme un ciel indéniable, une certitude secrète spontanément domine les constructions de nos jours. La moindre secousse est tremblement de terre. Tours écroulées, les oiseaux rient dans nos rêves et, par vengeance, épanouissent l’éventail de leurs plus belles et plus terribles plumes. Par les rues des villes, mon corps qui se croyait éveillé fut somnambule. Dans sa maison endormie (la paix ! mes yeux, ma poitrine, mes bras, mes jambes, mon sexe), oui, dans sa maison endormie, mon esprit retrouve sa sérénité. La vie, la mort ? Mon esprit ne permet à mon corps de continuer à vivre que par certain masochisme bien illogique.

Au réveil, je me souviens mal. Tout de même, je ne puis oublier que tel rêve avait le goût de la vie, tel autre le goût de la mort, aussi précisément que tel plat avait le goût du sucre, tel autre, le goût du sel. C’est pourquoi, je me demande : à quoi bon protéger de la mort mes jours ?

La recherche des causes finales, comme une vierge consacrée à Dieu, est stérile, écrivait Bacon. Or, il faut beaucoup de frivolité pour préférer à cette vierge stérile ses sœurs fécondes. La recherche des causes qui ne sont pas finales vaut juste un divertissement. Faute de mieux, à l’égal des autres divertissements (voyages, dancings, essais sexuels), elle ne peut qu’aider à tuer le temps. Tuer le temps ? Mais si je commence à vouloir tuer le temps, l’ennui devenant plus fort à mesure que j’en désire triompher, je me retrouve contraint à de perpétuelles surenchères. Pour qui se refuse au terrible secours des problèmes essentiels, bien vite il n’y a d’autres possibilité que le geste ultime : le suicide.

Ainsi qui veut prendre des chemins frivoles et se soustraire à toute angoisse, n’en est pas moins obligé d’envisager l’idée de mort. Une telle nécessité, forçant à la douleur les plus médiocres, prête toujours une beauté tragique aux fêtes des hommes.

Mais, dira-t-on, certains se couchent sans avoir agi, sans avoir bu, sans avoir dansé, qui ne feront même l’amour avant de s’endormir. Supposons un de ceux-là en paix avec lui-même. Il pense que sa journée fut bonne, car rien ne s’y trouva désiré ou accompli qui pût choquer des soucis moraux intimes non plus que des conventions. Notre homme en paix se laisse glisser dans ses draps, se réjouit du sommeil à venir, se souhaite une bonne nuit, glousse d’aise, s’écoute glousser d’aise et s’endort.

Belle catastrophe ! Voilà qu’un premier rêve le prend, le prolonge dans la nuit, l’empêche de croire à l’oubli, au sommeil, à la mort. Il se dit que, s’il a tué le temps, dévoré l’espace, c’est qu’il voulait se tuer avec le temps, se dévorer avec l’espace. Une volonté d’anéantissement était à la naissance de tous ses actes. Il désirait prendre une notion des choses pour perdre celle qu’il allait prendre de lui-même. Il pensait que chaque réussite devait être une victoire contre soi bien plus qu’une victoire contre les autres. Il a mesuré le temps, l’espace, pour que ne viennent plus le hanter les notions de Dieu, d’absolu, de vie, de mort. Mais, hors du temps et de l’espace, il reste lui et il sait que sa vie, sa mort ne sauraient être confondues avec la vie, la mort des kilos de viande qui le désignent aux sens des autres. Le sommeil de son corps n’est pas son sommeil. Lui-même, il ne peut se mesurer. Alors, à quoi bon les bornes kilométriques, les montres ? Il a fait comme s’il savait où allait le chemin, combien valait l’heure. Il a marché, il a compté. En fait, il a continué d’ignorer la route, le nombre.

Économie, lâcheté, impuissance. Vaines sont les consolations offertes à sa curiosité, à l’inquiétude de son âme, consolations qu’il baptisait pompeusement : vérités relatives .

La vie est-elle constituée de l’ensemble des phénomènes bien connus ? Notre homme aime-t-il la vie ? Si oui, ayant mis dans cette vie toutes ses complaisances, son amour de la vie, s’il use de quelque logique, va le contraindre à se donner la mort, car, en vérité, si tant de moines vécurent vieux, aimant et désirant la mort, les jouisseurs des villes intelligentes se tuent jeunes, aimant et désirant la vie. N’est-ce pas Pétrone ? En effet, l’amour qui se veut justifier ou se trouve dans l’obligation de se vouloir justifier, critiquera ce dont justement il est né.

C’est de cette critique que sort l’activité dont l’ensemble est égal à la somme de ce que nous appelons suicides provisoires .

Mais, puis-je imaginer qu’à la suite de ces suicides provisoires, un geste définitif me permettra d’achever à jamais une vie que j’aime lorsque je la crois précaire et que j’exècre dès qu’elle me semble la simple projection terrestre d’un moment de marche éternelle ? L’intelligence pousse au suicide. Mais j’ai parlé de certaine sensation d’âme. Cette sensation d’âme, qui n’est ni la peur ni la joie, me force à poursuivre ce que j’ai entrepris.

Au reste, la hantise du suicide n’est-elle pas le meilleur remède contre le suicide ?

1925

Renée Crevel poetry & prose

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crevel, Renée

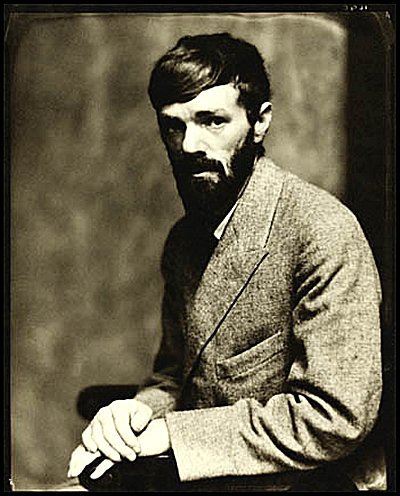

Norbert de Vries

Het huis van een dichter

Over Pierre Kemp

Pierre Kemp woonde van 23 april 1929 tot zijn dood (in 1967) in het pand Turennestraat 21 te Maastricht. En, hoera, op zaterdag 1 december 2007 is er, op initiatief van Wiel Kusters en oud-burgemeester van Maastricht, Philip Houben, een plaquette onthuld die in de gevel van dit pand is aangebracht, en waarop het volgende te lezen en te zien is:

“Ik woon al lang in een huis van de lucht,

iets hoger dan de vogels in de bomen”

Hier woonde en werkte van 1928 tot 1967 de dichter Pierre Kemp

De geciteerde dichtregels zijn de beginregels van het gedicht Emeritaat. De slotregels zijn het ook waard om te worden vermeld. Na te hebben beschreven dat hij in zijn stille straat zelden bezoek krijgt, lezen we:

“Jeroen Bosch komt hier wel eens voorbij

en even rusten,

om te praten over de na-aperij

van onze Tuinen der Lusten.”

Na de onthulling van de plaquette was er een bijeenkomst waar Wiel Kusters en Fred van Leeuwen ieder een korte causerie hielden.

Kusters las op waar Kemp in zijn jeugd en na zijn huwelijk allemaal gewoond had: een lange lijst van (ik heb niet geteld, maar schat) ruim over de twintig adressen, waarvan verreweg de meeste in Wyck (het – kleinere – deel van Maastricht dat aan de oostelijke oever van de Maas ligt) te situeren zijn. Alleen al in de Rechtstraat (een van de mooiste straten van Maastricht, als u het mij vraagt) heeft hij op meer dan een handvol verschillende huisnummers gewoond.

Maar dan vestigt Kemp zich in 1929 met vrouw en drie zonen in de huurwoning aan de Turennestraat, en zal er bijna veertig jaar blijven wonen.

Ja, het jaar 1929 is een soort scharnierjaar voor Kemp.

Het is het jaar van zijn verhuizing naar de Turennestraat, het jaar waarin zijn gedicht Verbascum in het tijdschrift De Gemeenschap verscheen (en Kemp zelf beschouwde dit als het moment van zijn tweede debuut), en het jaar waarin hij brak met de katholieke kunstzuil.

In 1921 was Kemp toegetreden tot de Algemeene R.K. Kunstenaarsvereeniging, maar in 1929 zegde hij zijn lidmaatschap op, stellende dat “het voor alle kunst, de Rooms-Katholieke niet uitgezonderd, wenselijk is, dat de kunstenaar zijn eigen autonomie bewaart en niet met behulp van een collectiviteit, en in afhankelijkheid daarvan, omziet naar een goede pers, beloningen in geld of eretekens.”

Het huis van de dichter is gelegen in een soort protestantse ‘enclave’. De Turennestraat komt uit op het Sterreplein waar een kerkje stond van de (naar ik meen) gereformeerde gemeente. Het kerkgebouw is er nog, maar het dient thans tot atelier.

De huizen van de Turennestraat zijn gebouwd in ‘een soort van’ Amsterdamse Stijl. Als il het zeggen mag: een saai huis in een saaie, stille straat, maar wat geeft dat als de dichterlijk bewoner het kon betoveren. Ziehier wat Kemp in 1957 dichtte:

Kindertekening

Ik heb een kindertekening gehuurd

en woon daar nu in.

Het is er zeer stil en er wordt gegluurd

door de takken van potlood. Ik begin

me al goed te wennen en er komen

wat kinderen van school voorbij.

Ze schilderen op de bomen

rode appels voor mij.

Er is ook een meisje. Het spreekt mij aan:

‘zonder bladeren kunnen geen appels bestaan’.

Nu wordt de lucht nog blauwer blauw

en de zon draait met meer plezier.

Was je niet van papier,

praktisch kind, ik vroeg je tot vrouw!

Fred van Leeuwen (1925), een vriend van Kemp, wijst op diens ongeëvenaarde talent om alles te ‘verongewonen’. Hij ziet de dichter nog zitten in de voorkamer (de schuifdeuren naar de achterkamer waren altijd gesloten: dáár was het gezinsleven, maar de voorkamer was zijn werkkamer). Hij ontving er je, gezeten achter zijn bureau. Langs de wanden zijn boeken, gekaft in vliegerpapier. Al die kleuren hadden een schilderachtig of, zo u wilt, poëtisch effect, maar de achtergrond was heel praktisch, ja prozaïsch: als je je boeken kaftte, dan bleef het omslag fris en kon je de boeken later veel beter verkopen.

De werkkamer was, aldus Van Leeuwen, zijn ‘camera obscura’. Was voorheen de trein zijn ‘bewegende camera’, na zijn pensionering per 1 januari 1945, dichtte hij in zijn werkkamer, aan zijn bureau. Vanuit zijn kamer ziet hij naar de wereld. In de straat, in de boeken.

Ook kan het gebeuren dat hij in de kelder bezig is, en een ogenblik opkijkt:

Keldergat

Het blijft me een vreemd bekoren

daar bij het keldergat.

De zon heeft er in een web verloren

rood licht, in paars en groen gevat.

En voor de achtergrond van het fluiten

met het grommen van het stadsverkeer

gaan pijpen van broeken en kuiten

statig wandelen-doende heen en weer.

Een mooi gedichtje, zeker, maar ik vraag me af of er in de derde regel niet ‘weeft’ moet staan, in plaats van ‘heeft’. (Ik citeer uit het Verzameld Werk)

Van Leeuwen vertelde, dat het niet zo simpel was om met de oudere Kemp in contact te komen. Dat ging meestal via de introductie door een goede vriend van Kemp, en dan nog na het voeren van enige correspondentie. In huize Kemp was er namelijk geen telefoon, zodat een telefonische afspraak niet tot de mogelijkheden behoorde.

Kemp leed op latere leeftijd aan een hardnekkige oogkwaal; hij zag bij tijden zo weinig dat hij enkel met behulp van een arsenaal aan vergrootglazen en sterke lampen nog enigszins kon schrijven. Lees hoe de bijna blinde dichter zich, zelfs in die benarde omstandigheid, verheugen kon over het bezoek van vrienden:

Leven

Ik zie een seconde van een paar vrienden

en glimlach van onder mijn haar,

zo intens, als ik dit, oudgediende,

nog word gewaar.

De lucht in de kamer voel ik beven

en spartelen tegen de wand.

Dit kan, zo juist gaf leven en leven

elkander de volle hand.

Norbert de Vries over Pierre Kemp (Maastricht, 2007)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Kemp, Pierre, Norbert de Vries

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (6)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio,

Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

OF THE NOTES OF SERAFINO GUBBIO

CINEMATOGRAPH OPERATOR

6

All the reflexions that I made at the beginning with regard to my wretched plight, and that of all the others who are condemned like myself to be nothing more than a hand that turns a handle, have as their starting point this man, whom I met on the morning after myarrival in Rome. Certainly I have been in a position to make them, because I too have been reduced to this office of being the servant of a machine; but that came afterwards.

I say this, because this man presented to the reader at this point, after the aforesaid reflexions, might appear to him to be a grotesque invention of my fancy. But let him remember that I should perhaps never have thought of those reflexions, had they not been, partly at least, suggested to me by Simone Pau’s introducing the unfortunate creature to me; while, for that matter, the whole of this first adventure of mine is grotesque, and is so because Simone Pau himself is, and means to be, almost by profession, grotesque, as he shewed on that first evening when he chose to take me to a Casual Shelter.

I did not make any reflexion whatsoever at the time; in the first place, because I could never, even in my wildest dreams, have thought that I should be reduced to this occupation; also, because I should have been interrupted by a great hubbub on the stair leading to the dormitory, and by the tumultuous and joyful inrush of all the inmates who had already gone down to the dressing-room to recover their clothes.

What had happened?

They came upstairs again, still swathed in the white wrappers, and with the slippers on their feet.

Among them, together with the attendants and the Sisters of Charity attached to the Shelter and to the soup kitchen, were a number of gentlemen and some ladies, all well dressed and smiling, with an air of curiosity and novelty. Two of these gentlemen were carrying, one a machine, which now I know well, wrapped in a black cover, while the other had under his arm its knock-kneed tripod. They were actors and operators from a cinematograph company, and had come about a film to take a scene from real life in a Casual Shelter.

The cinematograph company which had sent these actors was the Kosmograph, in which I for the last eight months have held the post of operator; and the stage manager who was in charge of them was Nicola Polacco, or, as they all call him, Cocò Polacco, my playmate and schoolfellow at Naples in my early boyhood. I am indebted to him for my post, and to the fortunate coincidence of my happening to have spent the night with Simone Pau in that Casual Shelter.

But neither, I repeat, did it enter my mind, that morning, that I should ever come down to setting up a photographic camera on its tripod, as I saw these two gentlemen doing, nor did it occur to Cocò Polacco to suggest such an occupation to me. He, like the good fellow that he is, made no bones about recognising me, whereas I, having at once recognised him, was trying my hardest not to catch his eye in that wretched place, seeing him radiant with Parisian smartness and with the air and in the setting of an invincible leader of men, among all those actors and actresses and all those recruits of poverty, whowere beside themselves with joy in their white gowns at this unlooked-for source of profit. He shewed surprise at finding me there, but only because of the early hour, and asked me how I had known that he and his company would be coming that morning to the Shelter for a real life interior. I left him under the illusion that I had turned up there by chance, out of curiosity; I introduced Simone Pau (the man with the violin, in the confusion, had slipped away); and I remained to look on disgusted at the indecent contamination of this grim reality, the full horror of which I had tasted overnight, by the stupid fiction which Polacco had come there to stage.

My disgust, however, I perhaps feel only now. That morning, I must have felt more than anything else curiosity at being present for the first time at the production of a film. This curiosity, though, was distracted at a certain point in the proceedings by one of the actresses, who, the moment I caught sight of her, aroused in me another curiosity far more keen.

Nestoroff? Was it possible? It seemed to be she and yet it seemed not to be. That hair of a strange tawny colour, almost coppery, that style of dress, sober, almost stiff, were not hers. But the motion of her slender, exquisite body, with a touch of the feline in the sway of her hips; the head raised high, inclined a little to one side, and that sweet smile on a pair of lips as fresh as a pair of rose-leaves, whenever anyone addressed her; those eyes, unnaturally wide, open,

greenish, fixed and at the same time vacant, and cold in the shadow of their long lashes were hers, entirely hers, with that certainty all her own that everyone, whatever she might say or ask, would answer yes.

Varia Nestoroff? Was it possible? Acting for a cinematograph company?

There flashed through my mind Capri, the Russian colony, Naples, all those noisy gatherings of young artists, painters, sculptors, in strange eccentric haunts, full of sunshine and colour, and a house, a dear house in the country, near Sorrento, into which this woman had brought confusion and death.

When, after a second rehearsal of the scene for which the company had come to the Shelter, Cocò Polacco invited me to come and see him at the Kosmograph, I, still in doubt, asked him if this actress was really the Nestoroff.

“Yes, my dear fellow,” he answered with a sigh. “You know her history, perhaps.”

I nodded my head.

“Ah, but you can’t know the rest of it!” Polacco went on. “Come, come and see me at the Kosmograph; I’ll tell you the whole story. Gubbio, I don’t know what I wouldn’t pay to get that woman off my hands. But, I can tell you, it is asier…”

“Polacco! Polacco!” she called to him at that moment.

And from the haste with which Cocò Polacco obeyed her summons, I fully realised the power that she had with the firm, from which she held a contract as principal with one of the most lavish salaries.

A day or two later I went to the Kosmograph, for no reason except to learn the rest of this woman’s story, of which I knew the beginning all too well.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (6)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

![]()

Niels Landstra: 2 gedichten

De oorsprong

Het lentelicht spat op je lach uiteen;

je schoonheid heeft dat onbestemde

van een vrouw in een jonge zomer

met een huid, geurend naar perenbloesems

die neerdalen op beken teer zonlicht

In de bossen kennen we de bomen

die de kuilen met de bladerbedden

aan het zicht onttrekken, waar je bloot

kirrend met je voeten wiebelt, je zin-

speelt op een bestendiging van dit aards

samenzijn, hier bouwen we leemhutten

heimelijkheid, met een interieur van

twijgjes, sprokkelhout en afgodsbeeldjes

is het zoel, en lommerrijk, adem ik

jou in de luwte van alledag, en,

als later onze bomen zijn geveld

beeld je dan in dat ik het marmer in

de wolken ben, wenend grijs bloed, sijpel

ik warm op je neer; proef van je schoonheid

en je mooie huid, als in de oorsprong.

De slijpende tijd

De tortels beklonken het conclaaf in de nok

van de kerkspits, de ruiten bogen vroom

in het lood. De zon kierde als uit een zoom

in de wolken op haar bruidsjurk, de regen trok

spijlen in de lucht, grauw als schroot. Het decor

voor een arme trouwscène: geen omafiets

die haar de stad uitreed, of het alternatief,

een wagen met slingerende blikjes, daardoor

brak er iets in dat meisje uit den vreemde;

ze zag ooit velden uitrollen naar een einder,

die vrij was van snelwegen en HSL treinen,

waar koeien graasden, dampende paarden

in galop naar haar omzagen; tractoren

daverden door dorpen in pompoenkleuren

langs sobere maar bloemrijke kerkhoven

en huizen met stal en boomgaard, hoe verloren

bleef ze hier, ook na die bruiloft zonder franje;

nu tast zij rond met dor trouwe handen, sijpelt

het ijle in haar rede, krast haar hoon als glas;

slijpt de tijd uit haar wie ze als vrouw aanbad.

Niels Landstra (1966) Op jonge leeftijd begon Niels Landstra met schrijven. Zijn eerste (nog ongepubliceerde) roman voltooide hij begin jaren negentig en was getiteld ‘Speelweide’. Zeven jaar later volgde ‘Het nietige verlangen’ en onlangs ‘De dwalende volgeling’ (De toenmalige proloog van de laatstgenoemde roman is te lezen in de Brakke Hond onder de titel “Van nul naar niets”). Na een periode waarin Niels Landstra zich bezighield met het schrijven van poëzie, verfijnde hij zijn stijl, en debuteerde in 2004 in Meander met het kortverhaal ‘Het portret’. In maart 2011 verscheen zijn kortverhaal ‘Een gelukkig man’ in: Aangeboord Talent. Deze verhalen- en poëziebundel, een bloemlezing met zestien schrijvers uit Vlaanderen en Nederland, uitgebracht door uitgeverij Beefcake Publishing in België, is goed ontvangen door de diverse media. Korte verhalen, interviews en poëzie verschenen in: Meander, Lava, De Brakke Hond, Deus ex Machina, De Gekooide Roos, De Neus, Woordenstroom, DWB, Op Ruwe Planken, Opspraak en Nieuw Letterkundig Magazijn.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

Marianne Moore

(1887 -1972)

Nevertheless

you’ve seen a strawberry

that’s had a struggle; yet

was, where the fragments met,

a hedgehog or a star-

fish for the multitude

of seeds. What better food

than apple seeds – the fruit

within the fruit – locked in

like counter-curved twin

hazelnuts? Frost that kills

the little rubber-plant –

leaves of kok-sagyyz-stalks, can’t

harm the roots; they still grow

in frozen ground. Once where

there was a prickley-pear –

leaf clinging to a barbed wire,

a root shot down to grow

in earth two feet below;

as carrots from mandrakes

or a ram’s-horn root some-

times. Victory won’t come

to me unless I go

to it; a grape tendril

ties a knot in knots till

knotted thirty times – so

the bound twig that’s under-

gone and over-gone, can’t stir.

The weak overcomes its

menace, the strong over-

comes itself. What is there

like fortitude! What sap

went through that little thread

to make the cherry red!

Marianne Moore poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

115

Those lines that I before have writ do lie,

Even those that said I could not love you dearer,

Yet then my judgment knew no reason why,

My most full flame should afterwards burn clearer,

But reckoning time, whose millioned accidents

Creep in ‘twixt vows, and change decrees of kings,

Tan sacred beauty, blunt the sharp’st intents,

Divert strong minds to the course of alt’ring things:

Alas why fearing of time’s tyranny,

Might I not then say ‘Now I love you best,’

When I was certain o’er incertainty,

Crowning the present, doubting of the rest?

Love is a babe, then might I not say so

To give full growth to that which still doth grow.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature