Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Alfonsina Storni

(1892-1938)

¿Qué Diría?

¿Qué diría la gente, recortada y vacía,

Si un día fortuito, por ultra fantasía,

Me tiñera el cabello de plateado y violeta,

Usara peplo griego, cambiara la peineta

Por cintillo de flores: miosotis o jazmines,

Cantara por las calles al compás de violines,

O dijera mis versos recorriendo las plazas

Libertado mi gusto de vulgares mordazas?

¿Irían a mirarme cubriendo las aceras?

¿Me quemarían como quemaron heciceras?

¿Campanas tocarían para llamar a misa?

En verdad que pensarlo me da un poco de risa.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Storni, Alfonsina

J.A. dèr Mouw

(1863-1919)

‘k Zie nu al hoe ‘k, als jij gestorven bent

‘K zie nu al hoe ‘k, als jij gestorven bent,

Zal zitten, kijkend naar je stil gezicht;

Wel vol verleden, toch pijnlijk verlicht,

Dat jij ten minste geen verdriet meer kent.

Mijn handen zullen, vroeger lang gewend,

Van zelf aaien je haar, waar levend ligt,

Als vroeger, nog het diep glanzende licht,

Dat uit de dood mij jouw vergeving zendt.

‘T is alles tevergeefs: nu weet ik al,

Dat ‘k dan, mijn hartje, niet begrijpen zal,

Hoe ‘k jou geen liefde gaf, mijzelf geen rust;

Zelfkwellend zal ‘k je, herrezen, zien staan,

Jong, als toen ik ‘t geluk voorbij liet gaan,

Die ene nacht. toen ‘k je niet heb gekust.

J.A. dèr Mouw gedicht

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Professions for Women

A paper read to The Women’s Service League

When your secretary invited me to come here, she told me that your Society is concerned with the employment of women and she suggested that I might tell you something about my own professional experiences. It is true I am a woman; it is true I am employed; but what professional experiences have I had? It is difficult to say. My profession is literature; and in that profession there are fewer experiences for women than in any other, with the exception of the stage—fewer, I mean, that are peculiar to women. For the road was cut many years ago—by Fanny Burney, by Aphra Behn, by Harriet Martineau, by Jane Austen, by George Eliot—many famous women, and many more unknown and forgotten, have been before me, making the path smooth, and regulating my steps. Thus, when I came to write, there were very few material obstacles in my way. Writing was a reputable and harmless occupation. The family peace was not broken by the scratching of a pen. No demand was made upon the family purse. For ten and sixpence one can buy paper enough to write all the plays of Shakespeare—if one has a mind that way. Pianos and models, Paris, Vienna and Berlin, masters and mistresses, are not needed by a writer. The cheapness of writing paper is, of course, the reason why women have succeeded as writers before they have succeeded in the other professions.

But to tell you my story—it is a simple one. You have only got to figure to yourselves a girl in a bedroom with a pen in her hand. She had only to move that pen from left to right—from ten o’clock to one. Then it occurred to her to do what is simple and cheap enough after all—to slip a few of those pages into an envelope, fix a penny stamp in the corner, and drop the envelope into the red box at the corner. It was thus that I became a journalist; and my effort was rewarded on the first day of the following month—a very glorious day it was for me—by a letter from an editor containing a cheque for one pound ten shillings and sixpence. But to show you how little I deserve to be called a professional woman, how little I know of the struggles and difficulties of such lives, I have to admit that instead of spending that sum upon bread and butter, rent, shoes and stockings, or butcher’s bills, I went out and bought a cat—a beautiful cat, a Persian cat, which very soon involved me in bitter disputes with my neighbours.

What could be easier than to write articles and to buy Persian cats with the profits? But wait a moment. Articles have to be about something. Mine, I seem to remember, was about a novel by a famous man. And while I was writing this review, I discovered that if I were going to review books I should need to do battle with a certain phantom. And the phantom was a woman, and when I came to know her better I called her after the heroine of a famous poem, The Angel in the House. It was she who used to come between me and my paper when I was writing reviews. It was she who bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her. You who come of a younger and happier generation may not have heard of her—you may not know what I mean by the Angel in the House. I will describe her as shortly as I can. She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught she sat in it—in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. Above all—I need not say it—–she was pure. Her purity was supposed to be her chief beauty—her blushes, her great grace. In those days—the last of Queen Victoria—every house had its Angel. And when I came to write I encountered her with the very first words. The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. Directly, that is to say, I took my pen in my hand to review that novel by a famous man, she slipped behind me and whispered: “My dear, you are a young woman. You are writing about a book that has been written by a man. Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex. Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of your own. Above all, be pure.” And she made as if to guide my pen. I now record the one act for which I take some credit to myself, though the credit rightly belongs to some excellent ancestors of mine who left me a certain sum of money—shall we say five hundred pounds a year?—so that it was not necessary for me to depend solely on charm for my living. I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self–defence. Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. For, as I found, directly I put pen to paper, you cannot review even a novel without having a mind of your own, without expressing what you think to be the truth about human relations, morality, sex. And all these questions, according to the Angel of the House, cannot be dealt with freely and openly by women; they must charm, they must conciliate, they must—to put it bluntly—tell lies if they are to succeed. Thus, whenever I felt the shadow of her wing or the radiance of her halo upon my page, I took up the inkpot and flung it at her. She died hard. Her fictitious nature was of great assistance to her. It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality. She was always creeping back when I thought I had despatched her. Though I flatter myself that I killed her in the end, the struggle was severe; it took much time that had better have been spent upon learning Greek grammar; or in roaming the world in search of adventures. But it was a real experience; it was an experience that was bound to befall all women writers at that time. Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer.

But to continue my story. The Angel was dead; what then remained? You may say that what remained was a simple and common object—a young woman in a bedroom with an inkpot. In other words, now that she had rid herself of falsehood, that young woman had only to be herself. Ah, but what is “herself”? I mean, what is a woman? I assure you, I do not know. I do not believe that you know. I do not believe that anybody can know until she has expressed herself in all the arts and professions open to human skill. That indeed is one of the reasons why I have come here out of respect for you, who are in process of showing us by your experiments what a woman is, who are in process Of providing us, by your failures and successes, with that extremely important piece of information.

But to continue the story of my professional experiences. I made one pound ten and six by my first review; and I bought a Persian cat with the proceeds. Then I grew ambitious. A Persian cat is all very well, I said; but a Persian cat is not enough. I must have a motor car. And it was thus that I became a novelist—for it is a very strange thing that people will give you a motor car if you will tell them a story. It is a still stranger thing that there is nothing so delightful in the world as telling stories. It is far pleasanter than writing reviews of famous novels. And yet, if I am to obey your secretary and tell you my professional experiences as a novelist, I must tell you about a very strange experience that befell me as a novelist. And to understand it you must try first to imagine a novelist’s state of mind. I hope I am not giving away professional secrets if I say that a novelist’s chief desire is to be as unconscious as possible. He has to induce in himself a state of perpetual lethargy. He wants life to proceed with the utmost quiet and regularity. He wants to see the same faces, to read the same books, to do the same things day after day, month after month, while he is writing, so that nothing may break the illusion in which he is living—so that nothing may disturb or disquiet the mysterious nosings about, feelings round, darts, dashes and sudden discoveries of that very shy and illusive spirit, the imagination. I suspect that this state is the same both for men and women. Be that as it may, I want you to imagine me writing a novel in a state of trance. I want you to figure to yourselves a girl sitting with a pen in her hand, which for minutes, and indeed for hours, she never dips into the inkpot. The image that comes to my mind when I think of this girl is the image of a fisherman lying sunk in dreams on the verge of a deep lake with a rod held out over the water. She was letting her imagination sweep unchecked round every rock and cranny of the world that lies submerged in the depths of our unconscious being. Now came the experience, the experience that I believe to be far commoner with women writers than with men. The line raced through the girl’s fingers. Her imagination had rushed away. It had sought the pools, the depths, the dark places where the largest fish slumber. And then there was a smash. There was an explosion. There was foam and confusion. The imagination had dashed itself against something hard. The girl was roused from her dream. She was indeed in a state of the most acute and difficult distress. To speak without figure she had thought of something, something about the body, about the passions which it was unfitting for her as a woman to say. Men, her reason told her, would be shocked. The consciousness of—what men will say of a woman who speaks the truth about her passions had roused her from her artist’s state of unconsciousness. She could write no more. The trance was over. Her imagination could work no longer. This I believe to be a very common experience with women writers—they are impeded by the extreme conventionality of the other sex. For though men sensibly allow themselves great freedom in these respects, I doubt that they realize or can control the extreme severity with which they condemn such freedom in women.

These then were two very genuine experiences of my own. These were two of the adventures of my professional life. The first—killing the Angel in the House—I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. I doubt that any woman has solved it yet. The obstacles against her are still immensely powerful—and yet they are very difficult to define. Outwardly, what is simpler than to write books? Outwardly, what obstacles are there for a woman rather than for a man? Inwardly, I think, the case is very different; she has still many ghosts to fight, many prejudices to overcome. Indeed it will be a long time still, I think, before a woman can sit down to write a book without finding a phantom to be slain, a rock to be dashed against. And if this is so in literature, the freest of all professions for women, how is it in the new professions which you are now for the first time entering?

Those are the questions that I should like, had I time, to ask you. And indeed, if I have laid stress upon these professional experiences of mine, it is because I believe that they are, though in different forms, yours also. Even when the path is nominally open—when there is nothing to prevent a woman from being a doctor, a lawyer, a civil servant—there are many phantoms and obstacles, as I believe, looming in her way. To discuss and define them is I think of great value and importance; for thus only can the labour be shared, the difficulties be solved. But besides this, it is necessary also to discuss the ends and the aims for which we are fighting, for which we are doing battle with these formidable obstacles. Those aims cannot be taken for granted; they must be perpetually questioned and examined. The whole position, as I see it—here in this hall surrounded by women practising for the first time in history I know not how many different professions—is one of extraordinary interest and importance. You have won rooms of your own in the house hitherto exclusively owned by men. You are able, though not without great labour and effort, to pay the rent. You are earning your five hundred pounds a year. But this freedom is only a beginning—the room is your own, but it is still bare. It has to be furnished; it has to be decorated; it has to be shared. How are you going to furnish it, how are you going to decorate it? With whom are you going to share it, and upon what terms? These, I think are questions of the utmost importance and interest. For the first time in history you are able to ask them; for the first time you are able to decide for yourselves what the answers should be. Willingly would I stay and discuss those questions and answers—but not to–night. My time is up; and I must cease.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Death of the Moth, and other essays

kempis poetry magazine

![]()

More in: Woolf, Virginia

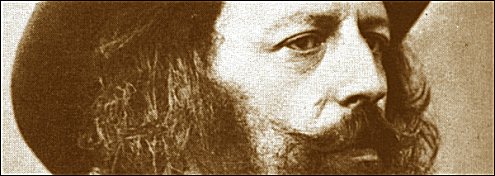

Alfred Lord Tennyson

(1809-1892)

Nothing will die

When will the stream be aweary of flowing

Under my eye?

When will the wind be aweary of blowing

Over the sky?

When will the clouds be aweary of fleeting?

When will the heart be aweary of beating?

And nature die?

Never, oh! never, nothing will die?

The stream flows,

The wind blows,

The cloud fleets,

The heart beats,

Nothing will die.

Nothing will die;

All things will change

Through eternity.

‘Tis the world’s winter;

Autumn and summer

Are gone long ago;

Earth is dry to the centre,

But spring, a new comer,

A spring rich and strange,

Shall make the winds blow

Round and round,

Through and through,

Here and there,

Till the air

And the ground

Shall be filled with life anew.

The world was never made;

It will change, but it will not fade.

So let the wind range;

For even and morn

Ever will be

Through eternity.

Nothing was born;

Nothing will die;

All things will change.

.jpg)

Alfred Lord Tennyson poetry

kempis poetry magazine

![]()

More in: Tennyson, Alfred Lord

Christian Morgenstern

(1871-1914)

Der zertrümmerte Spiegel

Am Himmel steht ein Spiegel, riesengroß.

Ein Wunderland, im klarsten Sonnenlichte,

entwächst berückend dem kristallnen Schoß.

Um bunter Tempel marmorne Gedichte

ergrünt geheimnisvoller Haine Kranz;

der Seen Silber dunkle Kähne spalten,

und wallender Gewänder heller Glanz

verrät dem Auge wandelnde Gestalten.

Wohl kenn ich dich, du seliges Gefild! . .

Doch was in heitrer Ruh erglänzt dort oben,

ist mehr als dein getreues Spiegelbild,

ist Irdisches zu Göttlichem erhoben.

Du zeigst ein friedsam wolkenloses Glück,

um das umsonst die Staubgebornen werben . . .

Und doch! Auch du bist nur ein Schemenstück!

Ein Hauch -: Du schläfst im Grund in tausend Scherben.

Ein Hauch! . . Von düstren Wolken löst ein Flug

sich von der Felskluft Schautribünenstufen.

Um meinen Gipfel streift ihr dumpfer Zug,

als hätte sie mein fürchtend Herz gerufen.

Hinunter weist beschwörend meine Hand,

indes mein Aug nach oben bittet «Bleibe!»

Umsonst! Ein Stoß zermalmt des Spiegels Rand,

und donnernd bäumt sich die gewaltige Scheibe

und stürzt, von tausend Sprüngen überzackt,

mit fürchterlichem Tosen in die Tiefen.

Der Abgrund schreit, von wildem Graun gepackt.

Blutüberströmt die Wolken talwärts triefen.

Fahlgrüner Splitterregen spritzt umher,

den Leib der Nacht zerschneidend und zerfleischend.

Mordbrüllend wühlt der Sturm im Nebelmeer

und heult in jede Höhle, wollustkreischend.

Der Berge Adern schwellen, brechen auf

und schäumen graue Fülle ins Geklüfte.

Ihr Flutsturz reißt verstreuter Scherben Hauf

unhemmbar mit in finstre Waldnachtgrüfte.

Es wogt der Forsten nasses Kronenhaar,

durchblendet von demantnem Pfeilgewimmel . .

Doch um die Höhen wird es langsam klar,

durch Tränen lächelt der beraubte Himmel.

Und bald verblitzt der letzten Scherbe Schein,

zum Grund gefegt vom Sturm- und Wellentanze.

Nur feiner Glasstaub deckt noch Baum und Stein

und funkelt tausendfach im Sonnenglanze . . .

Ich schau, ich sinne, hab der Zeit nicht acht -:

Den Tag verscheuchte längst der Schattenriese.

Und aus der Tiefe predigen durch die Nacht

die Fälle vom versunknen Paradiese.

Christian Morgenstern poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Christian Morgenstern, Morgenstern, Christian

O s c a r W i l d e

(1854-1900)

Flower of Love

Sweet, I blame you not, for mine the fault

was, had I not been made of common clay

I had climbed the higher heights unclimbed

yet, seen the fuller air, the larger day.

From the wildness of my wasted passion I had

struck a better, clearer song,

Lit some lighter light of freer freedom, battled

with some Hydra-headed wrong.

Had my lips been smitten into music by the

kisses that but made them bleed,

You had walked with Bice and the angels on

that verdant and enamelled mead.

I had trod the road which Dante treading saw

the suns of seven circles shine,

Ay! perchance had seen the heavens opening,

as they opened to the Florentine.

And the mighty nations would have crowned

me, who am crownless now and without name,

And some orient dawn had found me kneeling

on the threshold of the House of Fame.

I had sat within that marble circle where the

oldest bard is as the young,

And the pipe is ever dropping honey, and the

lyre’s strings are ever strung.

Keats had lifted up his hymeneal curls from out

the poppy-seeded wine,

With ambrosial mouth had kissed my forehead,

clasped the hand of noble love in mine.

And at springtide, when the apple-blossoms

brush the burnished bosom of the dove,

Two young lovers lying in an orchard would

have read the story of our love;

Would have read the legend of my passion,

known the bitter secret of my heart,

Kissed as we have kissed, but never parted as

we two are fated now to part.

For the crimson flower of our life is eaten by

the cankerworm of truth,

And no hand can gather up the fallen withered

petals of the rose of youth.

Yet I am not sorry that I loved you – ah!

what else had I a boy to do, –

For the hungry teeth of time devour, and the

silent-footed years pursue.

Rudderless, we drift athwart a tempest, and

when once the storm of youth is past,

Without lyre, without lute or chorus, Death

the silent pilot comes at last.

And within the grave there is no pleasure,

for the blindworm battens on the root,

And Desire shudders into ashes, and the tree

of Passion bears no fruit.

Ah! what else had I to do but love you?

God’s own mother was less dear to me,

And less dear the Cytheraean rising like an

argent lily from the sea.

I have made my choice, have lived my

poems, and, though youth is gone in wasted days,

I have found the lover’s crown of myrtle better

than the poet’s crown of bays.

.jpg)

O s c a r W i l d e p o e t r y

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Wilde, Oscar

![]()

D E R T I E N H E C T A R E H E E S W I J K

The woods that see and hear

30 mei – 11 juli 2010

Tue Greenfort, ‘Eutrophication’

dertien hectare presenteert de tentoonstelling

‘The woods that see and hear’,

samengesteld door Sarah Farrar (NZ).

De tentoonstelling reageert op de directe fysieke omgeving van dertien hectare; het Noord-Brabantse gebied dat de afgelopen decennia veelbetekenende sociale, economische en ecologische veranderingen heeft ondergaan. De tentoonstelling vindt plaats op twee locaties; het terrein van dertien hectare, een voormalige intensieve varkenshouderij, dat getransformeerd is tot een gebied voor herbebossing, en de ruimte van het CBK ’s-Hertogenbosch in een voormalige fabriek in ´s-Hertogenbosch.

Zoals in elk landschap, liggen hier vele sporen van veranderende opvattingen verborgen. Het land herbergt vele lagen geschiedenis en vormt een nauwkeurig getuigschrift van menselijke activiteit en veranderende normen en waarden. ‘The woods that see and hear’ benadert het land als ware het een levende archeologie, dat de invloed van menselijke migratie; welvaart; technologische ontwikkelingen; veranderende waarden met betrekking tot het milieu; overheidsbeleid; commerciële belangen en de verschuivende grenzen van stedelijke en landelijke gebieden registreert.

Eve Armstrong, ‘Turn‘

Geïnspireerd door de radicale verandering van het gebruik van het tentoonstellingsterrein en de daaraan verbonden ecologische implicaties, ontrafelen en onderzoeken de kunstenaarsprojecten noties rondom duurzaamheid, maatschappelijke verantwoordelijkheid, verontreiniging en vergroening vanuit een ‘post-environmentalist’ benadering. Waar de historische milieubeweging de ‘natuurlijke omgeving’ nog als een apart domein beschouwde, betogen de aanhangers van de post-environmentalist beweging dat om de ecologische crises waar we vandaag de dag mee geconfronteerd worden het hoofd te bieden, we hun intrinsieke verbondenheid met grotere sociale, politieke en economische krachten in overweging moeten nemen. Door het terrein van dertien hectare met een voormalige sigarenfabriek in de stad ’s-Hertogenbosch te verbinden onderzoekt de tentoonstelling de verregaande en tegelijkertijd nabije gevolgen van industrialiseringsprocessen.

De tentoonstellingstitel verwijst naar een pentekening van Jheronimus Bosch (zelf afkomstig uit de omgeving Bernheze) van een bosje kreupelhout en grasland, bewoond door een uil, een vos, een groepje vogels en, bizar genoeg, twee afgesneden oren en zeven ogen. Oorspronkelijk symboliseerde het prentje een waarschuwing tegen spionnen en luistervinken, maar in het licht van de huidige landschappelijke ontwikkelingen vormt het een herinnering aan onze intrinsieke verbondenheid met de natuurlijke wereld.

Tea Mäkipää, ‘Petrol Engine Memorial Park’

Door de twee locaties als onderzoeksterrein en -platform te gebruiken wil de tentoonstelling een bewust engagement met en nieuwsgierigheid naar onze relatie met het land en de wereld die wij bewonen genereren – als individuen, als leden van een gemeenschap en als wereldburgers.

Deelnemende kunstenaars:

Eduardo Abaroa (MX) / Eve Armstrong (NZ) / Melanie Bonajo (NL), Kinga Kielczynska (PL) en Emmeline de Mooij (NL) / Marjolijn Dijkman (NL) / Bright Ugochukwu Eke (NG) / Tue Greenfort (DK) / Jonathan Horowitz (US) / Ives Maes (BE) / Tea Mäkipää (FI) / Nick Mangan (AU) / Heather en Ivan Morison (GB) / Overtreders W (NL).

Locatie Dertien Hectare:

Meerstraat 22, 5473 VW Heeswijk

Eduardo Abaroa, ‘Sanitary Stonehenge’

DERTIEN HECTARE

dertien hectare is een Brabantse kunststichting die elke twee jaar een tentoonstelling presenteert in het buitengebied van Heeswijk-Bernheze, omgeving ‘s-Hertogenbosch. Het tentoonstellingsterrein is een voormalige boerderij die getransformeerd wordt tot aanplantbos, onder invloed van veranderend nationale en Europese natuurbeleid. In dit zich ontwikkelende landschap, tussen de alsmaar groter wordende bomen, presenteert dertien hectare werk van internationale hedendaagse kunstenaars.

Elke tentoonstelling wordt geïnspireerd door, en ontwikkeld in relatie tot, de specifieke context van het terrein. dertien hectare verwelkomt de reacties van kunstenaars en curatoren uit verschillende globale contexten en moedigt de ontwikkeling van site-specific projecten aan. De tentoonstellingen van dertien hectare bezitten een gelaagdheid aan interpretaties en spreken tot een lokaal, nationaal en international publiek.

dertien hectare bevindt zich in een regio met een rijke landbouwgeschiedenis. Generaties lang was het terrein onderdeel van een groot boerenbedrijf, maar het ondergaat sinds 2003 een radicale transformatie door de aanplant van meer dan 35.000 bomen in het kader van landschapsontwikkeling.

Het terrein, dat beschikt over dertien hectare grond, bevindt zich in het buitengebied van de dorpen Heeswijk-Dinther in de provincie Noord-Brabant. Het terrein bevindt zich in de omgeving van boerderijen, woonhuizen en vrijetijdsbestemmingen, waaronder een aantal campings, restaurants, hotels, een openlucht theater en maneges. De regio geeft ook plaats aan een aantal historische trekpleisters, zoals de Meierijsche Museumboerderij, de Berne Abdij en het middeleeuwse kasteel Heeswijk.

In tegenstelling tot andere openlucht tentoonstellingen, wordt dertien hectare niet gepresenteerd in een statige tuin of stadspark, maar bevindt het zich te midden van een agrarisch gebied dat volop in ontwikkeling is. Deze context biedt een prikkelend uitgangspunt en inspiratie voor de gastcuratoren en deelnemende kunstenaars.

Overblijfselen van eerdere dertien hectare tentoonstellingen kunnen nog steeds op het terrein worden teruggevonden, zoals het zebrapad ‘De oversteek’ van Jan van den Langenberg, ‘All Alone Among the Stars’ van Marjolijn Dijkman, en een houten tribune dat onderdeel was van de installatie ‘Stereo rain’, van Jeroen Doorenweerd.

Het terrein van dertien hectare is in particulier bezit, maar publiek toegankelijk via de oevers van het riviertje de Leijgraaf of, tijdens de tentoonstelling, langs de entree op Meerstraat 22, Heeswijk.

Ives Maes

dertien hectare wordt georganiseerd door: Miesjel van Gerwen, Toine van der Heijden, Frans van Lokven, Jannemeis Snels en Ivonne van der Velden.

photos ton van kempen

Heather and Ivan Morison, ´Saint John´

fleursdumal.nl magazine

![]()

More in: Dutch Landscapes, FDM Art Gallery

.jpg)

Louis Couperus

(1863-1923)

Baadster

Een blanke nymf steeg ze uit het marmren bad,

En toefde op de eerste treê; heur armen beurden

En wrongen ‘t blonde hair, dat druipend nat

Nog van den amber der violen geurde.

Hoe ‘t rozig-blond van ‘t blozend rozeblad

De sneeuw haars teedren lichaams warmer kleurde,

Terwijl van paerlen vloeyende en omspat,

Zij lelie was, die in den dauwe treurde!

Daar stond ze, steunende op het slanke been,

Zoo, dat bevallig zich de heupe rondde,

Nu de armen hoog de dartle lokken bonden.

Daar stond ze, glanzend-wit als marmersteen,

Geheel omsluyerd in den korenblonde:

Antieke vaas met douden veile omwonden.

Louis Couperus gedicht

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Louis Couperus

Ton van Reen was bevriend met Jan Hanlo. Met Jan Hanlo maakte van Reen vaak wandelingen door de Peel en de omgeving van Valkenburg. Ze correspondeerden over honing, wijn en gedichten.

Een paar dagen voordat Jan Hanlo op zijn motor verongelukte had hij Ton van Reen nog bezocht. Later bezocht Van Reen het graf van Jan en liet er het gedicht BERICHT VOOR JAN HANLO achter voor de bijen.

Ton van Reen

Bericht voor Jan Hanlo

Eenzaam sta ik aan jouw graf

de zon gaat als een beest tekeer

en keer op keer laat een spin

zich aan een zijden draad neer op jouw zerk

weeft een web

dwars over het goed onderhouden perk

van jouw hof

zodat je onder een zilveren sluier

verscholen ligt

begraven onder het stof

van jouw laatste gedicht

Net voordat jij je de dood inreed

schreef jij dat je me bezocht

daarom had ik honing voor je gekocht

vier potten zeem van het soort

dat jij met kilo’s eten kon

raatzuivere honing uit de Peel –

die honing laat ik achter bij jouw graf

wellicht komen er bijen op af

jij hield zo van het dol getik

van bijen tegen het glas van jouw huis

op zoek naar honing op de vensterbank

uit dank kreeg jij de ene na de andere prik

jij juichte blij

dacht dat je na elke steek

weer een jaar meer had te leven

terwijl je mij vlak daarvoor nog had geschreven

dat je er de brui aan gaf

je zag van alle rotzooi af

maar de starre eenheid van een bijenvolk

maakte jou weer vrij, gaf jou een nieuwe kick

terwijl jij zelf de grootste eenling was

Er groeit vochtig steenkruid langs jouw graf

hondsdraf, viool en paardenbloem

dit kruid bereidt veel zuurstof

dat komt jou goed van pas

vaker had je ademnood

gebrek aan licht en lucht

soms was je al een beetje dood

Ter hoogte van je rechterbeen

vreet een zonnedauw

het laatste segment van een libel

aan die plant ben jij verwant

hij staat passend op jouw graf

als zonnedauw vrat je elk woord kaal

tot op het laatst fragment

jij verkleinde alles

tot de kleinste schaal

zodat jij nu jezelf pas bent

Jan Hanlo (1912-1969)

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Hanlo, Jan, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Comte Nikolai de Godemiché

(1878-1935)

Literaire Salon

…het zou een onverwarmd, mager verlicht zaaltje moeten zijn met ijsbloemen op de ramen aan de rand van een desolate stad waar een aantal dichters, in aanwezigheid van een raaf, bijeenkomt om een grootse salon op te richten, een literair sociale werkplaats voor contactgestoorden en aan schrijfdrang lijdende leprozen. Deze salon zou bestaan uit meerdere vertrekken, één die enkel toegankelijk is voor leden, met beleefde obers, lederen fauteuils en een donkere lambrisering, waar de gebruikelijke drankjes worden geserveerd alleen vele vele jaren ouder, met een knetterend haardvuur en aangenaam keuvelende bezoekers die somtijds over de vloer rollen om een vrouw dan wel om een rijm- of rangtelwoord. Een salon waar een elegante dame rondwaart achteloos chic met zware lokken, omgeven door een betoverende geur stammend uit een achttiende-eeuws parfumhuis, slechts mondjesmaat verkrijgbaar en dan nog voor ingewijden; zij komt en gaat. Vriendelijke tabakswalmen drijven richting deur bij binnenkomst van weer een gast, het literaire neusje van de zalm zou hier de grizzlys ontwijken met historisch bewogen teksten en koliekopwekkende verzen. Uitgevers zouden een moord begaan om in deze salon te mogen oogsten (de schrijver X zal er in ontredderde toestand worden aangetroffen, maar dat is nog toekomstmuziek).

Een ander vertrek zal voor iedereen toegankelijk zijn, een vertrek met grote leestafels. Grote leestafels en veel ruimte tussen de tafels zoals in café Griensteidl, zodat je met een bontjas kunt binnenkomen. Dagbladen en tijdschriften uit de landen van de grote denkers en kunstenaars liggen er ter inzage. De bediening echter zal povertjes zijn aangezien deze in handen is van oudere jongedames die, gebeeldhouwd naar de kwabben van een uitgewoonde volkszanger en ruw van de tongriem gesneden, onverstoorbaar uitblinken in desinteresse voor hun cliëntèle.

“Vanaf welke sterren zijn wij elkaar toegevallen?” Met deze woorden begroet Nietzsche, bij hun eerste ontmoeting, Lou Andreas-Salome op 24 april 1882 in de Sint-Pieterskerk te Rome. Deze regel zal een plekje krijgen aan de wand van de Salome-salon, een gedeelte slechts toegankelijk voor vrouwen, het derde en één na laatste vertrek van de literaire salon. Salome schreef over de Liebesrausch als zijnde het scheppende moment in de kunst. Volgens haar hebben vrouwen huis en haard niet nodig, zij vergelijkt de vrouw met een ‘rondtrekkende dievenbende’ die zich van wetten weinig aantrekt. Zij die Nietzsche afwees, een verhouding begon met Rilke, samenwerkte met Freud en eerst haar oriëntalist huwde nadat deze zich door het hart schoot maar op wonderbaarlijke wijze overleefde. Ze huwde hem op voorwaarde van geen seks en een vrij huwelijk.

De Salome-salon dus.

Het mooiste en oudste vertrek tenslotte, met het hoge van een fresco voorziene plafond, zal worden omgevormd tot bibliotheek. Een unieke bibliotheek van meer dan honderdtwintigduizend titels op het gebied van poëzie, met o.a. de collectie boeken die eens toebehoorde aan graaf de Montesquiou-Fézensac, de verfijnde estheet die model stond voor Huysmans’ Des Esseintes en Prousts baron de Charlus en die Verlaine vaak financieel had ondersteund.

Er zal wellicht discussie ontstaan over de portrettengalerij in de salon en over de omgang met de raaf, want komt Poe nu bij de Fransen te hangen, of boven de deur naast de kooi met de raaf? Of mag de raaf los? Het laten rondvliegen van de raaf kent voornamelijk bezwaren van hygiënische aard (heer Y.; ”ik wil geen bakkie vogelenkak!”), desondanks zal heer Z. blijven ijveren voor een vrij vogel verkeer. In een tweede vergadering wordt de motivatie aangedragen voor de opening van nog een gelegenheid, een herenclub dit keer, club ‘Nevermore’, voor die momenten wanneer de sublimatie van het libido eens misloopt, deze club zal worden bewoond door negen aan de dichtkunst gewijde vulva’s met de blauwgeaderde rondingen van een begrijpend gemoed.

‘s Ochtends vroeg bij het verlaten van deze cocon, de wereld wit als een laken, een diepe ademteug in je sjaal en steevast verse sporen in de sneeuw.

(Comte Nikolai de Godemiché: Fauneske Verzen & Prozagedichten. Erotica. Uitgeverij Spleen Amsterdam, 2008, 2e druk)

Comte Nikolai de Godemiché (1878-1935) stamt af van het kind dat op wonderbaarlijke wijze werd geboren uit een overleden en reeds begraven moeder. Dieven hadden het graf geschonden en ontdekten dat de dode vrouw in barensweeën verkeerde. Ze namen het kind mee en begroeven de vrouw opnieuw. Heinrich Heine doet verslag over deze bizarre gebeurtenis in zijn verhaal ‘Florentijnse nachten’.

De voorvader van Nikolai werd bijwijze van zwijggeld een adellijke titel toegekend om zijn afkomst te verdoezelen als bastaardzoon van een telg uit een bekende Duits-Franse bankiersfamilie. Oorspronkelijk was Comte de Godemiché de titel van een libertijn die zijn huurdames placht te ontvangen in een gecapitonneerde kamer opdat het gillen voor de buitenwacht verborgen bleef. Het was een van de vele titels die vrij rolde door het werk van de guillotine in de nadagen van de Revolutie en als zodanig voor hergebruik in aanmerking kwam.

Op 57 jarige leeftijd wierp de aan alcohol en opium verslaafde Nikolai zich van de Notre Dame. Deze getalenteerde misantropische polyglot beheerste onder andere het Nederlands, de taal waarin hij schreef. Zijn literaire nalatenschap bestaat uit 19 wulpse gedichten.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Erotic literature

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

To the Memory of Mrs. Lefroy

who died Dec’r 16 — my Birthday

The day returns again, my natal day;

What mix’d emotions with the Thought arise!

Beloved friend, four years have pass’d away

Since thou wert snatch’d forever from our eyes.–

The day, commemorative of my birth

Bestowing Life and Light and Hope on me,

Brings back the hour which was thy last on Earth.

Oh! bitter pang of torturing Memory!–

Angelic Woman! past my power to praise

In Language meet, thy Talents, Temper, mind.

Thy solid Worth, they captivating Grace!–

Thou friend and ornament of Humankind!–

At Johnson’s death by Hamilton t’was said,

‘Seek we a substitute–Ah! vain the plan,

No second best remains to Johnson dead–

None can remind us even of the Man.’

So we of thee–unequall’d in thy race

Unequall’d thou, as he the first of Men.

Vainly we wearch around the vacant place,

We ne’er may look upon thy like again.

Come then fond Fancy, thou indulgant Power,–

–Hope is desponding, chill, severe to thee!–

Bless thou, this little portion of an hour,

Let me behold her as she used to be.

I see her here, with all her smiles benign,

Her looks of eager Love, her accents sweet.

That voice and Countenance almost divine!–

Expression, Harmony, alike complete.–

I listen–’tis not sound alone–’tis sense,

‘Tis Genius, Taste and Tenderness of Soul.

‘Tis genuine warmth of heart without pretence

And purity of Mind that crowns the whole.

She speaks; ’tis Eloquence–that grace of Tongue

So rare, so lovely!–Never misapplied

By her to palliate Vice, or deck a Wrong,

She speaks and reasons but on Virtue’s side.

Her’s is the Engergy of Soul sincere.

Her Christian Spirit ignorant to feign,

Seeks but to comfort, heal, enlighten, chear,

Confer a pleasure, or prevent a pain.–

Can ought enhance such Goodness?–Yes, to me,

Her partial favour from my earliest years

Consummates all.–Ah! Give me yet to see

Her smile of Love.–the Vision diappears.

‘Tis past and gone–We meet no more below.

Short is the Cheat of Fancy o’er the Tomb.

Oh! might I hope to equal Bliss to go!

To meet thee Angel! in thy future home!–

Fain would I feel an union in thy fate,

Fain would I seek to draw an Omen fair

From this connection in our Earthly date.

Indulge the harmless weakness–Reason, spare.–

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

![]()

Louise Ackermann

(1813-1890)

L’amour et la mort

(A M. Louis de Ronchaud)

I

Regardez-les passer, ces couples éphémères !

Dans les bras l’un de l’autre enlacés un moment,

Tous, avant de mêler à jamais leurs poussières,

Font le même serment :

Toujours ! Un mot hardi que les cieux qui vieillissent

Avec étonnement entendent prononcer,

Et qu’osent répéter des lèvres qui pâlissent

Et qui vont se glacer.

Vous qui vivez si peu, pourquoi cette promesse

Qu’un élan d’espérance arrache à votre coeur,

Vain défi qu’au néant vous jetez, dans l’ivresse

D’un instant de bonheur ?

Amants, autour de vous une voix inflexible

Crie à tout ce qui naît : “Aime et meurs ici-bas ! ”

La mort est implacable et le ciel insensible ;

Vous n’échapperez pas.

Eh bien ! puisqu’il le faut, sans trouble et sans murmure,

Forts de ce même amour dont vous vous enivrez

Et perdus dans le sein de l’immense Nature,

Aimez donc, et mourez !

II

Non, non, tout n’est pas dit, vers la beauté fragile

Quand un charme invincible emporte le désir,

Sous le feu d’un baiser quand notre pauvre argile

A frémi de plaisir.

Notre serment sacré part d’une âme immortelle ;

C’est elle qui s’émeut quand frissonne le corps ;

Nous entendons sa voix et le bruit de son aile

Jusque dans nos transports.

Nous le répétons donc, ce mot qui fait d’envie

Pâlir au firmament les astres radieux,

Ce mot qui joint les coeurs et devient, dès la vie,

Leur lien pour les cieux.

Dans le ravissement d’une éternelle étreinte

Ils passent entraînés, ces couples amoureux,

Et ne s’arrêtent pas pour jeter avec crainte

Un regard autour d’eux.

Ils demeurent sereins quand tout s’écroule et tombe ;

Leur espoir est leur joie et leur appui divin ;

Ils ne trébuchent point lorsque contre une tombe

Leur pied heurte en chemin.

Toi-même, quand tes bois abritent leur délire,

Quand tu couvres de fleurs et d’ombre leurs sentiers,

Nature, toi leur mère, aurais-tu ce sourire

S’ils mouraient tout entiers ?

Sous le voile léger de la beauté mortelle

Trouver l’âme qu’on cherche et qui pour nous éclôt,

Le temps de l’entrevoir, de s’écrier : ” C’est Elle ! ”

Et la perdre aussitôt,

Et la perdre à jamais ! Cette seule pensée

Change en spectre à nos yeux l’image de l’amour.

Quoi ! ces voeux infinis, cette ardeur insensée

Pour un être d’un jour !

Et toi, serais-tu donc à ce point sans entrailles,

Grand Dieu qui dois d’en haut tout entendre et tout voir,

Que tant d’adieux navrants et tant de funérailles

Ne puissent t’émouvoir,

Qu’à cette tombe obscure où tu nous fais descendre

Tu dises : ” Garde-les, leurs cris sont superflus.

Amèrement en vain l’on pleure sur leur cendre ;

Tu ne les rendras plus ! ”

Mais non ! Dieu qu’on dit bon, tu permets qu’on espère ;

Unir pour séparer, ce n’est point ton dessein.

Tout ce qui s’est aimé, fût-ce un jour, sur la terre,

Va s’aimer dans ton sein.

III

Eternité de l’homme, illusion ! chimère !

Mensonge de l’amour et de l’orgueil humain !

Il n’a point eu d’hier, ce fantôme éphémère,

Il lui faut un demain !

Pour cet éclair de vie et pour cette étincelle

Qui brûle une minute en vos coeurs étonnés,

Vous oubliez soudain la fange maternelle

Et vos destins bornés.

Vous échapperiez donc, ô rêveurs téméraires

Seuls au Pouvoir fatal qui détruit en créant ?

Quittez un tel espoir ; tous les limons sont frères

En face du néant.

Vous dites à la Nuit qui passe dans ses voiles :

” J’aime, et j’espère voir expirer tes flambeaux. ”

La Nuit ne répond rien, mais demain ses étoiles

Luiront sur vos tombeaux.

Vous croyez que l’amour dont l’âpre feu vous presse

A réservé pour vous sa flamme et ses rayons ;

La fleur que vous brisez soupire avec ivresse :

“Nous aussi nous aimons !”

Heureux, vous aspirez la grande âme invisible

Qui remplit tout, les bois, les champs de ses ardeurs ;

La Nature sourit, mais elle est insensible :

Que lui font vos bonheurs ?

Elle n’a qu’un désir, la marâtre immortelle,

C’est d’enfanter toujours, sans fin, sans trêve, encor.

Mère avide, elle a pris l’éternité pour elle,

Et vous laisse la mort.

Toute sa prévoyance est pour ce qui va naître ;

Le reste est confondu dans un suprême oubli.

Vous, vous avez aimé, vous pouvez disparaître :

Son voeu s’est accompli.

Quand un souffle d’amour traverse vos poitrines,

Sur des flots de bonheur vous tenant suspendus,

Aux pieds de la Beauté lorsque des mains divines

Vous jettent éperdus ;

Quand, pressant sur ce coeur qui va bientôt s’éteindre

Un autre objet souffrant, forme vaine ici-bas,

Il vous semble, mortels, que vous allez étreindre

L’Infini dans vos bras ;

Ces délires sacrés, ces désirs sans mesure

Déchaînés dans vos flancs comme d’ardents essaims,

Ces transports, c’est déjà l’Humanité future

Qui s’agite en vos seins.

Elle se dissoudra, cette argile légère

Qu’ont émue un instant la joie et la douleur ;

Les vents vont disperser cette noble poussière

Qui fut jadis un coeur.

Mais d’autres coeurs naîtront qui renoueront la trame

De vos espoirs brisés, de vos amours éteints,

Perpétuant vos pleurs, vos rêves, votre flamme,

Dans les âges lointains.

Tous les êtres, formant une chaîne éternelle,

Se passent, en courant, le flambeau de l’amour.

Chacun rapidement prend la torche immortelle

Et la rend à son tour.

Aveuglés par l’éclat de sa lumière errante,

Vous jurez, dans la nuit où le sort vous plongea,

De la tenir toujours : à votre main mourante

Elle échappe déjà.

Du moins vous aurez vu luire un éclair sublime ;

Il aura sillonné votre vie un moment ;

En tombant vous pourrez emporter dans l’abîme

Votre éblouissement.

Et quand il régnerait au fond du ciel paisible

Un être sans pitié qui contemplât souffrir,

Si son oeil éternel considère, impassible,

Le naître et le mourir,

Sur le bord de la tombe, et sous ce regard même,

Qu’un mouvement d’amour soit encor votre adieu !

Oui, faites voir combien l’homme est grand lorsqu’il aime,

Et pardonnez à Dieu !

Louise Ackermann poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature