Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Mannen van Mobil

De mannen van Mobil houden Afrika in beweging

in hun vuilrode overalls met het Mobillogo

hurken ze bij de roestige benzinepomp

waarvan de teller op een getal zonder einde staat

ze kaarten en roken scherpe Sportsmansigaretten

De benzine wordt aangevoerd met ezels

die wie weet waar vandaan komen

in ieder geval van ver over de berg

geduldig schenken de mannen van Mobil

de zakken benzine over in plastic waterflessen

en betalen de ezeldrijver met beloftes

Ze kaarten verder en roken Sportsmansigaretten

rond de middag vallen ze in slaap

hurkend tegen de geblakerde benzinepomp

tot iemand de mannen van Mobil wakker maakt

iemand die een paar flessen benzine koopt

van de mannen die Afrika in beweging houden

Van het geld kopen ze white cap beer

en hurken weer neer bij de benzinepomp

ze delen de kaarten en roken Sportsmansigaretten

Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

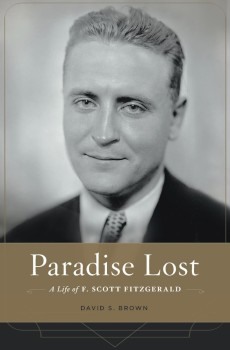

Pigeonholed in popular memory as a Jazz Age epicurean, a playboy, and an emblem of the Lost Generation, F. Scott Fitzgerald was at heart a moralist struck by the nation’s shifting mood and manners after World War I.

In Paradise Lost, David Brown contends that Fitzgerald’s deepest allegiances were to a fading antebellum world he associated with his father’s Chesapeake Bay roots. Yet as a midwesterner, an Irish Catholic, and a perpetually in-debt author, he felt like an outsider in the haute bourgeoisie haunts of Lake Forest, Princeton, and Hollywood—places that left an indelible mark on his worldview.

In Paradise Lost, David Brown contends that Fitzgerald’s deepest allegiances were to a fading antebellum world he associated with his father’s Chesapeake Bay roots. Yet as a midwesterner, an Irish Catholic, and a perpetually in-debt author, he felt like an outsider in the haute bourgeoisie haunts of Lake Forest, Princeton, and Hollywood—places that left an indelible mark on his worldview.

In this comprehensive biography, Brown reexamines Fitzgerald’s childhood, first loves, and difficult marriage to Zelda Sayre. He looks at Fitzgerald’s friendship with Hemingway, the golden years that culminated with Gatsby, and his increasing alcohol abuse and declining fortunes which coincided with Zelda’s institutionalization and the nation’s economic collapse.

Placing Fitzgerald in the company of Progressive intellectuals such as Charles Beard, Randolph Bourne, and Thorstein Veblen, Brown reveals Fitzgerald as a writer with an encompassing historical imagination not suggested by his reputation as “the chronicler of the Jazz Age.” His best novels, stories, and essays take the measure of both the immediate moment and the more distant rhythms of capital accumulation, immigration, and sexual politics that were moving America further away from its Protestant agrarian moorings. Fitzgerald wrote powerfully about change in America, Brown shows, because he saw it as the dominant theme in his own family history and life.

David S. Brown is Raffensperger Professor of History at Elizabethtown College.

“[An] incisive biography.”—The New Yorker

“Paradise Lost accomplishes much in its aim to contextualize Fitzgerald within both American historical and literary historical parameters. This new biography manages to get past the trappings of Fitzgerald’s boozy flapper-era persona and to credit his talent for taking the pulse of the America in which he lived.”—Christina Hunt Mahoney, The Irish Times

Paradise Lost

A Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald

David S. Brown

424 pag. – 2017

Harvard University Press

Belknap Press

Isbn 9780674504820

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, Fitzgerald, F. Scott

Flood

Goldbrown upon the sated flood

The rockvine clusters lift and sway;

Vast wings above the lambent waters brood

Of sullen day.

A waste of waters ruthlessly

Sways and uplifts its weedy mane

Where brooding day stares down upon the sea

In dull disdain.

Uplift and sway, O golden vine,

Your clustered fruits to love’s full flood,

Lambent and vast and ruthless as is thine

Incertitude!

James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

Flood

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

Ton van Reen

Het gras is van hem

Alle gras dat hij ziet is van hem

alle gras waar zijn oog op valt eigent hij zich toe

het gras tussen de stenen aan zijn voeten

het gras dat van steen naar steen kruipt

verder en verder

zo ver zijn oog reikt is alle gras van hem

Alles neemt hij

de hele grazige wereld die hij voor zich ziet

alle gras binnen zijn blikveld is van hem

Waar hij is, waar hij gaat is het gras van hem

hij hoort het zachte zuchten van zijn gras

Hij ruikt het ochtendgras

bewasemd door dauw

het groene gras dat zijn oog overweldigt

Ton van Reen: Het gras is van hem

Uit: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Natural history, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

The Invisible Girl

The Invisible Girl

by Mary Shelley

This slender narrative has no pretensions o the regularity of a story, or the development of situations and feelings; it is but a slight sketch, delivered nearly as it was narrated to me by one of the humblest of the actors concerned: nor will I spin out a circumstance interesting principally from its singularity and truth, but narrate, as concisely as I can, how I was surprised on visiting what seemed a ruined tower, crowning a bleak promontory overhanging the sea, that flows between Wales and Ireland, to find that though the exterior preserved all the savage rudeness that betokened many a war with the elements, the interior was fitted up somewhat in the guise of a summer-house, for it was too small to deserve any other name.

It consisted but of the ground-floor, which served as an entrance, and one room above, which was reached by a staircase made out of the thickness of the wall. This chamber was floored and carpeted, decorated with elegant furniture; and, above all, to attract the attention and excite curiosity, there hung over the chimney-piece — for to preserve the apartment from damp a fire-place had been built evidently since it had assumed a guise so dissimilar to the object of its construction — a picture simply painted in water-colours, which seemed more than any part of the adornments of the room to be at war with the rudeness of the building, the solitude in which it was placed, and the desolation of the surrounding scenery. This drawing represented a lovely girl in the very pride and bloom of youth; her dress was simple, in the fashion of the day — (remember, reader, I write at the beginning of the eighteenth century), her countenance was embellished by a look of mingled innocence and intelligence, to which was added the imprint of serenity of soul and natural cheerfulness. She was reading one of those folio romances which have so long been the delight of the enthusiastic and young; her mandoline was at her feet — her parroquet perched on a huge mirror near her; the arrangement of furniture and hangings gave token of a luxurious dwelling, and her attire also evidently that of home and privacy, yet bore with it an appearance of ease and girlish ornament, as if she wished to please. Beneath this picture was inscribed in golden letters, “The Invisible Girl.”

Rambling about a country nearly uninhabited, having lost my way, and being overtaken by a shower, I had lighted on this dreary looking tenement, which seemed to rock in the blast, and to be hung up there as the very symbol of desolation. I was gazing wistfully and cursing inwardly my stars which led me to a ruin that could afford no shelter, though the storm began to pelt more seriously than before, when I saw an old woman’s head popped out from a kind of loophole, and as suddenly withdrawn: — a minute after a feminine voice called to me from within, and penetrating a little brambly maze that skreened a door, which I had not before observed, so skilfully had the planter succeeded in concealing art with nature I found the good dame standing on the threshold and inviting me to take refuge within. “I had just come up from our cot hard by,” she said, “to look after the things, as I do every day, when the rain came on — will ye walk up till it is over?” I was about to observe that the cot hard by, at the venture of a few rain drops, was better than a ruined tower, and to ask my kind hostess whether “the things” were pigeons or crows that she was come to look after, when the matting of the floor and the carpeting of the staircase struck my eye. I was still more surprised when I saw the room above; and beyond all, the picture and its singular inscription, naming her invisible, whom the painter had coloured forth into very agreeable visibility, awakened my most lively curiosity: the result of this, of my.exceeding politeness towards the old woman, and her own natural garrulity, was a kind of garbled narrative which my imagination eked out, and future inquiries rectified, till it assumed the following form.

Some years before in the afternoon of a September day, which, though tolerably fair, gave many tokens of a tempestuous evening, a gentleman arrived at a little coast town about ten miles from this place; he expressed his desire to hire a boat to carry him to the town of about fifteen miles further on the coast. The menaces which the sky held forth made the fishermen loathe to venture, till at length two, one the father of a numerous family, bribed by the bountiful reward the stranger promised — the other, the son of my hostess, induced by youthful daring, agreed to undertake the voyage. The wind was fair, and they hoped to make good way before nightfall, and to get into port ere the rising of the storm. They pushed off with good cheer, at least the fishermen did; as for the stranger, the deep mourning which he wore was not half so black as the melancholy that wrapt his mind. He looked as if he had never smiled — as if some unutterable thought, dark as night and bitter as death, had built its nest within his bosom, and brooded therein eternally; he did not mention his name; but one of the villagers recognised him as Henry Vernon, the son of a baronet who possessed a mansion about three miles distant from the town for which be was bound. This mansion was almost abandoned by the family; but Henry had, in a romantic fit, visited it about three years before, and Sir Peter had been down there during the previous spring for about a couple of months.

The boat did not make so much way as was expected; the breeze failed them as they got out to sea, and they were fain with oar as well as sail, to try to weather the promontory that jutted out between them and the spot they desired to reach. They were yet far distant when the shifting wind began to exert its strength, and to blow with violent though unequal puffs. Night came on pitchy dark, and the howling waves rose and broke with frightful violence, menacing to overwhelm the tiny bark that dared resist their fury. They were forced to lower every sail, and take to their oars; one man was obliged to bale out the water, and Vernon himself took an oar, and rowing with desperate energy, equalled the force of the more practised boatmen. There had been much talk between the sailors before the tempest came on; now, except a brief command, all were silent. One thought of his wife and children, and silently cursed the caprice of the stranger that endangered in its effects, not only his life, but their welfare; the other feared less, for he was a daring lad, but he worked hard, and had no time for speech; while Vernon bitterly regretting the thoughtlessness which had made him cause others to share a peril, unimportant as far as he himself was concerned, now tried to cheer them with a voice full of animation and courage, and now pulled yet more strongly at the oar he held. The only person who did not seem wholly intent on the work he was about, was the man who baled; every now and then he gazed intently round, as if the sea held afar off, on its tumultuous waste, some object that he strained his eyes to discern. But all was blank, except as the crests of the high waves showed themselves, or far out on the verge of the horizon, a kind of lifting of the clouds betokened greater violence for the blast. At length he exclaimed — “Yes, I see it! — the larboard oar! — now! if we can make yonder light, we are saved!” Both the rowers instinctively turned their heads, — but cheerless darkness answered their gaze.

“You cannot see it,” cried their companion, ‘but we are nearing it; and, please God, we shall outlive this night.” Soon he took the oar from Vernon’s hand, who, quite exhausted, was failing in his strokes. He rose and looked for the beacon which promised them safety; — it glimmered with so faint a ray, that now he said, “I see it;” and again, “it is nothing:” still, as they made way, it dawned upon his sight, growing more steady and distinct as it beamed across the lurid waters,.which themselves be came smoother, so that safety seemed to arise from the bosom of the ocean under the influence of that flickering gleam.

“What beacon is it that helps us at our need?” asked Vernon, as the men, now able to manage their oars with greater ease, found breath to answer his question.

“A fairy one, I believe,” replied the elder sailor, “yet no less a true: it burns in an old tumble-down tower, built on the top of a rock which looks over the sea. We never saw it before this summer; and now each night it is to be seen, — at least when it is looked for, for we cannot see it from our village; — and it is such an out of the way place that no one has need to go near it, except through a chance like this. Some say it is burnt by witches, some say by smugglers; but this I know, two parties have been to search, and found nothing but the bare walls of the tower.

All is deserted by day, and dark by night; for no light was to be seen while we were there, though it burned sprightly enough when we were out at sea.

“I have heard say,” observed the younger sailor, “it is burnt by the ghost of a maiden who lost her sweetheart in these parts; he being wrecked, and his body found at the foot of the tower: she goes by the name among us of the ‘Invisible Girl.'”

The voyagers had now reached the landing-place at the foot of the tower. Vernon cast a glance upward, — the light was still burning. With some difficulty, struggling with the breakers, and blinded by night, they contrived to get their little bark to shore, and to draw her up on the beach:

they then scrambled up the precipitous pathway, overgrown by weeds and underwood, and, guided by the more experienced fishermen, they found the entrance to the tower, door or gate there was none, and all was dark as the tomb, and silent and almost as cold as death.

“This will never do,” said Vernon; “surely our hostess will show her light, if not herself, and guide our darkling steps by some sign of life and comfort.”

“We will get to the upper chamber,” said the sailor, “if I can but hit upon the broken down steps: but you will find no trace of the Invisible Girl nor her light either, I warrant.”

“Truly a romantic adventure of the most disagreeable kind,” muttered Vernon, as he stumbled over the unequal ground: “she of the beacon-light must be both ugly and old, or she would not be so peevish and inhospitable.”

With considerable difficulty, and, after divers knocks and bruises, the adventurers at length succeeded in reaching the upper story; but all was blank and bare, and they were fain to stretch themselves on the hard floor, when weariness, both of mind and body, conduced to steep their senses in sleep.

Long and sound were the slumbers of the mariners. Vernon but forgot himself for an hour; then, throwing off drowsiness, and finding his roughcouch uncongenial to repose, he got up and placed himself at the hole that served for a window, for glass there was none, and there being not even a rough bench, he leant his back against the embrasure, as the only rest he could find. He had forgotten his danger, the mysterious beacon, and its invisible guardian: his thoughts were occupied on the horrors of his own fate, and the unspeakable wretchedness that sat like a night-mare on his heart.

It would require a good-sized volume to relate the causes which had changed the once happy Vernon into the most woeful mourner that ever clung to the outer trappings of grief, as slight though cherished symbols of the wretchedness within. Henry was the only child of Sir Peter Vernon, and as much spoiled by his father’s idolatry as the old baronet’s violent and tyrannical temper would permit. A young orphan was educated in his father’s house, who in the same way was treated with generosity and kindness, and yet who lived in deep awe of Sir Peter’s authority, who was a widower; and these two children were all he had to exert his power over, or to whom.to extend his affection. Rosina was a cheerful-tempered girl, a little timid, and careful to avoid displeasing her protector; but so docile, so kind-hearted, and so affectionate, that she felt even less than Henry the discordant spirit of his parent. It is a tale often told; they were playmates and companions in childhood, and lovers in after days. Rosina was frightened to imagine that this secret affection, and the vows they pledged, might be disapproved of by Sir Peter. But sometimes she consoled herself by thinking that perhaps she was in reality her Henry’s destined bride, brought up with him under the design of their future union; and Henry, while he felt that this was not the case, resolved to wait only until he was of age to declare and accomplish his wishes in making the sweet Rosina his wife. Meanwhile he was careful to avoid premature discovery of his intentions, so to secure his beloved girl from persecution and insult. The old gentleman was very conveniently blind; he lived always in the country, and the lovers spent their lives together, unrebuked and uncontrolled. It was enough that Rosina played on her mandoline, and sang Sir Peter to sleep every day after dinner; she was the sole female in the house above the rank of a servant, and had her own way in the disposal of her time. Even when Sir Peter frowned, her innocent caresses and sweet voice were powerful to smooth the rough current of his temper. If ever human spirit lived in an earthly paradise, Rosina did at this time: her pure love was made happy by Henry’s constant presence; and the confidence they felt in each other, and the security with which they looked forward to the future, rendered their path one of roses under a cloudless sky. Sir Peter was the slight drawback that only rendered their tête — à — tête more delightful, and gave value to the sympathy they each bestowed on the other. All at once an ominous personage made its appearance in Vernon-Place, in the shape of a widow sister of Sir Peter, who, having succeeded in killing her husband and children with the effects of her vile temper, came, like a harpy, greedy for new prey, under her brother’s roof. She too soon detected the attachment of the unsuspicious pair. She made all speed to impart her discovery to her brother, and at once to restrain and inflame his rage. Through her contrivance Henry was suddenly despatched on his travels abroad, that the coast might be clear for the persecution of Rosina; and then the richest of the lovely girl’s many admirers, whom, under Sir Peter’s single reign, she was allowed, nay, almost commanded, to dismiss, so desirous was he of keeping her for his own comfort, was selected, and she was ordered to marry him. The scenes of violence to which she was now exposed, the bitter taunts of the odious Mrs. Bainbridge, and the reckless fury of Sir Peter, were the more frightful and overwhelming from their novelty. To all she could only oppose a silent, tearful, but immutable steadiness of purpose: no threats, no rage could extort from her more than a touching prayer that they would not hate her, because she could not obey.

“There must he something we don’t see under all this,” said Mrs. Bainbridge, “take my word for it, brother, — she corresponds secretly with Henry. Let us take her down to your seat in Wales, where she will have no pensioned beggars to assist her; and we shall see if her spirit be not bent to our purpose.”

Sir Peter consented, and they all three posted down to , — shire, and took up their abode in the solitary and dreary looking house before alluded to as belonging to the family. Here poor Rosina’s sufferings grew intolerable: — before, surrounded by well-known scenes, and in perpetual intercourse with kind and familiar faces, she had not despaired in the end of conquering by her patience the cruelty of her persecutors; — nor had she written to Henry, for his name had not been mentioned by his relatives, nor their attachment alluded to, and she felt an instinctive wish to escape the dangers about her without his being annoyed, or the sacred secret of her love being laid bare, and wronged by the vulgar abuse of his aunt or the bitter curses of his father. But when she was taken to Wales, and made a prisoner in her apartment, when the flinty.mountains about her seemed feebly to imitate the stony hearts she had to deal with, her courage began to fail. The only attendant permitted to approach her was Mrs. Bainbridge’s maid; and under the tutelage of her fiend-like mistress, this woman was used as a decoy to entice the poor prisoner into confidence, and then to be betrayed. The simple, kind-hearted Rosina was a facile dupe, and at last, in the excess of her despair, wrote to Henry, and gave the letter to this woman to be forwarded. The letter in itself would have softened marble; it did not speak of their mutual vows, it but asked him to intercede with his father, that he would restore her to the kind place she had formerly held in his affections, and cease from a cruelty that would destroy her. “For I may die,” wrote the hapless girl, “but marry another — never!” That single word, indeed, had sufficed to betray her secret, had it not been already discovered; as it was, it gave increased fury to Sir Peter, as his sister triumphantly pointed it out to him, for it need hardly be said that while the ink of the address was yet wet, and the seal still warm, Rosina’s letter was carried to this lady. The culprit was summoned before them; what ensued none could tell; for their own sakes the cruel pair tried to palliate their part. Voices were high, and the soft murmur of Rosina’s tone was lost in the howling of Sir Peter and the snarling of his sister. “Out of doors you shall go,” roared the old man; “under my roof you shall not spend another night.” And the words “infamous seductress,” and worse, such as had never met the poor girl’s ear before, were caught by listening servants; and to each angry speech of the baronet, Mrs. Bainbridge added an envenomed point worse than all.

More dead than alive, Rosina was at last dismissed. Whether guided by despair, whether she took Sir Peter’s threats literally, or whether his sister’s orders were more decisive, none knew, but Rosina left the house; a servant saw her cross the park, weeping, and wringing her hands as she went. What became of her none could tell; her disappearance was not disclosed to Sir Peter till the following day, and then he showed by his anxiety to trace her steps and to find her, that his words had been but idle threats. The truth was, that though Sir Peter went to frightful lengths to prevent the marriage of the heir of his house with the portionless orphan, the object of his charity, yet in his heart he loved Rosina, and half his violence to her rose from anger at himself for treating her so ill. Now remorse began to sting him, as messenger after messenger came back without tidings of his victim; he dared not confess his worst fears to himself; and when his inhuman sister, trying to harden her conscience by angry words, cried, “The vile hussy has too surely made away with herself out of revenge to us;” an oath, the most tremendous, and a look sufficient to make even her tremble, commanded her silence. Her conjecture, however, appeared too true: a dark and rushing stream that flowed at the extremity of the park had doubtless received the lovely form, and quenched the life of this unfortunate girl. Sir Peter, when his endeavours to find her proved fruitless, returned to town, haunted by the image of his victim, and forced to acknowledge in his own heart that he would willingly lay down his life, could he see her again, even though it were as the bride of his son — his son, before whose questioning he quailed like the veriest coward; for when Henry was told of the death of Rosina, he suddenly returned from abroad to ask the cause — to visit her grave, and mourn her loss in the groves and valleys which had been the scenes of their mutual happiness. He made a thousand inquiries, and an ominous silence alone replied. Growing more earnest and more anxious, at length he drew from servants and dependants, and his odious aunt herself, the whole dreadful truth. From that moment despair struck his heart, and misery named him her own. He fled from his father’s presence; and the recollection that one whom he ought to revere was guilty of so dark a crime, haunted him, as of old the Eumenides tormented the souls of men given up to their torturings.

His first, his only wish, was to visit Wales, and to learn if any new discovery had been made, and.whether it were possible to recover the mortal remains of the lost Rosina, so to satisfy the unquiet longings of his miserable heart. On this expedition was he bound, when he made his appearance at the village before named; and now in the deserted tower, his thoughts were busy with images of despair and death, and what his beloved one had suffered before her gentle nature had been goaded to such a deed of woe.

While immersed in gloomy reverie, to which the monotonous roaring of the sea made fit accompaniment, hours flew on, and Vernon was at last aware that the light of morning was creeping from out its eastern retreat, and dawning over the wild ocean, which still broke in furious tumult on the rocky beach. His companions now roused themselves, and prepared to depart. The food they had brought with them was damaged by sea water, and their hunger, after hard labour and many hours fasting, had become ravenous. It was impossible to put to sea in their shattered boat; but there stood a fisher’s cot about two miles off, in a recess in the bay, of which the promontory on which the tower stood formed one side, and to this they hastened to repair; they did not spend a second thought on the light which had saved them, nor its cause, but left the ruin in search of a more hospitable asylum. Vernon cast his eves round as he quitted it, but no vestige of an inhabitant met his eye, and he began to persuade himself that the beacon had been a creation of fancy merely. Arriving at the cottage in question, which was inhabited by a fisherman and his family, they made an homely breakfast, and then prepared to return to the tower, to refit their boat, and if possible bring her round. Vernon accompanied them, together with their host and his son. Several questions were asked concerning the Invisible Girl and her light, each agreeing that the apparition was novel, and not one being able to give even an explanation of how the name had become affixed to the unknown cause of this singular appearance; though both of the men of the cottage affirmed that once or twice they had seen a female figure in the adjacent wood, and that now and then a stranger girl made her appearance at another cot a mile off, on the other side of the promontory, and bought bread; they suspected both these to be the same, but could not tell. The inhabitants of the cot, indeed, appeared too stupid even to feel curiosity, and had never made any attempt at discovery. The whole day was spent by the sailors in repairing the boat; and the sound of hammers, and the voices of the men at work, resounded along the coast, mingled with the dashing of the waves. This was no time to explore the ruin for one who whether human or supernatural so evidently withdrew herself from intercourse with every living being. Vernon, however, went over the tower, and searched every nook in vain; the dingy bare walls bore no token of serving as a shelter; and even a little recess in the wall of the staircase, which he had not before observed, was equally empty and desolate.

Quitting the tower, he wandered in the pine wood that surrounded it, and giving up all thought of solving the mystery, was soon engrossed by thoughts that touched his heart more nearly, when suddenly there appeared on the ground at his feet the vision of a slipper. Since Cinderella so tiny a slipper had never been seen; as plain as shoe could speak, it told a tale of elegance, loveliness, and youth. Vernon picked it up; he had often admired Rosina’s singularly small foot, and his first thought was a question whether this little slipper would have fitted it. It was very strange! — it must belong to the Invisible Girl. Then there was a fairy form that kindled that light, a form of such material substance, that its foot needed to be shod; and yet how shod? — with kid so fine, and of shape so exquisite, that it exactly resembled such as Rosina wore! Again the recurrence of the image of the beloved dead came forcibly across him; and a thousand home-felt associations, childish yet sweet, and lover-like though trifling, so filled Vernon’s heart, that he threw himself his length on the ground, and wept more bitterly than ever the miserable fate of the sweet orphan.

In the evening the men quitted their work, and Vernon returned with them to the cot where.they were to sleep, intending to pursue their voyage, weather permitting, the following morning.

Vernon said nothing of his slipper, but returned with his rough associates. Often he looked back; but the tower rose darkly over the dim waves, and no light appeared. Preparations had been made in the cot for their accommodation, and the only bed in it was offered Vernon; but he refused to deprive his hostess, and spreading his cloak on a heap of dry leaves, endeavoured to give himself up to repose. He slept for some hours; and when he awoke, all was still, save that the hard breathing of the sleepers in the same room with him interrupted the silence. He rose, and going to the window, — looked out over the now placid sea towards the mystic tower; the light burning there, sending its slender rays across the waves. Congratulating himself on a circumstance he had not anticipated, Vernon softly left the cottage, and, wrapping his cloak round him, walked with a swift pace round the bay towards the tower. He reached it; still the light was burning. To enter and restore the maiden her shoe, would be but an act of courtesy; and Vernon intended to do this with such caution, as to come unaware, before its wearer could, with her accustomed arts, withdraw herself from his eyes; but, unluckily, while yet making his way up the narrow pathway, his foot dislodged a loose fragment, that fell with crash and sound down the precipice. He sprung forward, on this, to retrieve by speed the advantage he had lost by this unlucky accident. He reached the door; he entered: all was silent, but also all was dark. He paused in the room below; he felt sure that a slight sound met his ear. He ascended the steps, and entered the upper chamber; but blank obscurity met his penetrating gaze, the starless night admitted not even a twilight glimmer through the only aperture. He closed his eyes, to try, on opening them again, to be able to catch some faint, wandering ray on the visual nerve; but it was in vain. He groped round the room: he stood still, and held his breath; and then, listening intently, he felt sure that another occupied the chamber with him, and that its atmosphere was slightly agitated by an-other’s respiration. He remembered the recess in the staircase; but, before he approached it, he spoke: — he hesitated a moment what to say. “I must believe,” he said, ‘that misfortune alone can cause your seclusion; and if the assistance of a man — of a gentleman — “

An exclamation interrupted him; a voice from the grave spoke his name — the accents of Rosina syllabled, “Henry! — is it indeed Henry whom I hear?”

He rushed forward, directed by the sound, and clasped in his arms the living form of his own lamented girl — his own Invisible Girl he called her; for even yet, as he felt her heart beat near his, and as he entwined her waist with his arm, supporting her as she almost sank to the ground with agitation, he could not see her; and, as her sobs prevented her speech, no sense, but the instinctive one that filled his heart with tumultuous gladness, told him that the slender, wasted form he pressed so fondly was the living shadow of the Hebe beauty he had adored.

The morning saw this pair thus strangely restored to each other on the tranquil sea, sailing with a fair wind for L — , whence they were to proceed to Sir Peter’s seat, which, three months before, Rosina had quitted in such agony and terror. The morning light dispelled the shadows that had veiled her, and disclosed the fair person of the Invisible Girl. Altered indeed she was by suffering and woe, but still the same sweet smile played on her lips, and the tender light of her soft blue eyes were all her own. Vernon drew out the slipper, and shoved the cause that had occasioned him to resolve to discover the guardian of the mystic beacon; even now he dared not inquire how she had existed in that desolate spot, or wherefore she had so sedulously avoided observation, when the right thing to have been done was, to have sought him immediately, under whose care, protected by whose love, no danger need be feared. But Rosina shrunk from him as he spoke, and a death-like pallor came over her cheek, as she faintly whispered, ‘Your father’s curse — your father’s dreadful threats!” It appeared, indeed, that Sir Peter’s violence, and the cruelty of Mrs. Bainbridge, had succeeded in impressing Rosina with wild and unvanquishable terror. She had fled from their house without plan or forethought — driven by frantic horror and overwhelming fear, she had left it with scarcely any money, and there seemed to her no possibility of either returning or proceeding onward. She had no friend except Henry in the wide world; whither could she go? — to have sought Henry would have sealed their fates to misery; for, with an oath, Sir Peter had declared he would rather see them both in their coffins than married. After wandering about, hiding by day, and only venturing forth at night, she had come to this deserted tower, which seemed a place of refuge. I low she had lived since then she could hardly tell; — she had lingered in the woods by day, or slept in the vault of the tower, an asylum none were acquainted with or had discovered: by night she burned the pine-cones of the wood, and night was her dearest time; for it seemed to her as if security came with darkness. She was unaware that Sir Peter had left that part of the country, and was terrified lest her hiding-place should be revealed to him. Her only hope was that Henry would return — that Henry would never rest till he had found her. She confessed that the long interval and the approach of winter had visited her with dismay; she feared that, as her strength was failing, and her form wasting to a skeleton, that she might die, and never see her own Henry more.

An illness, indeed, in spite of all his care, followed her restoration to security and the comforts of civilized life; many months went by before the bloom revisiting her cheeks, and her limbs regaining their roundness, she resembled once more the picture drawn of her in her days of bliss, before any visitation of sorrow. It was a copy of this portrait that decorated the tower, the scene of her suffering, in which I had found shelter. Sir Peter, overjoyed to be relieved from the pangs of remorse, and delighted again to see his orphan-ward, whom he really loved, was now as eager as before he had been averse to bless her union with his son: Mrs. Bainbridge they never saw again. But each year they spent a few months in their Welch mansion, the scene of their early wedded happiness, and the spot where again poor Rosina had awoke to life and joy after her cruel persecutions. Henry’s fond care had fitted up the tower, and decorated it as I saw; and often did he come over, with his “Invisible Girl,” to renew, in the very scene of its occurrence, the remembrance of all the incidents which had led to their meeting again, during the shades of night, in that sequestered ruin.

Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851)

The Invisible Girl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

God zij geloofd is er Pepsi

Welkom in St. Mery Hotel

we hebben pepsi: drie birr

we hebben brood met pepsi: vijf birr

daarom kent iedereen ons in Konso

soms hebben we mirinda

dan kunnen we u brood met mirinda aanbieden

kom terug als we mirinda hebben

maar we hebben altijd pepsi

‘s ochtends, ‘s middags en ‘s avonds

kunnen we u brood met pepsi aanbieden

want we hebben altijd pepsi

kijk maar naar de blauwe letters

op het witte pepsireclamebord

met de rode pepsivlag

en de rood-wit-blauwe pepsibal

iedereen in Konso weet het

iedereen is welkom in St. Mery hotel

voor een maaltijd met pepsi: vijf birr

god zij dank is er pepsi

anders at u bij ons alleen droog brood

maar gelukkig hebben wij brood met pepsi

pepsi is echt een uitkomst voor u

wij zijn er trots op, heel trots

dat wij altijd pepsi in huis hebben

jammer dat we juist vandaag geen pepsi hebben

en gisteren was er ook geen pepsi

en morgen misschien ook niet,

maar volgende week of zeker over twee weken

hebben wij pepsi in huis, heel zeker

kom over een paar weken terug in St. Mery Hotel

want we hebben altijd pepsi

Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten. In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, FDM in Africa, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen

Dode Vogel

Een dode vogel

in een droog landschap

De nagels in een laatste kramp

vastgeklemd rond de tak

houden hem overeind in de zon

Kleurige vleugels

bedekken zijn lege lijf

de witte oogkassen

door de wind leeggevreten

Hij is de wachter

die waarschuwt voor de dood

Ton van Reen: Dode Vogel

Uit: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

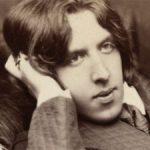

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

The Master

Now when the darkness came over the earth Joseph of Arimathea, having lighted a torch of pinewood, passed down from the hill into the valley. For he had business in his own home.

And kneeling on the flint stones of the Valley of Desolation he saw a young man who was naked and weeping. His hair was the colour of honey, and his body was as a white flower, but he had wounded his body with thorns and on his hair had he set ashes as a crown.

And he who had great possessions said to the young man who was naked and weeping, ‘I do not wonder that your sorrow is so great, for surely He was a just man.’

And the young man answered, ‘It is not for Him that I am weeping, but for myself. I too have changed water into wine, and I have healed the leper and given sight to the blind. I have walked upon the waters, and from the dwellers in the tombs I have cast out devils. I have fed the hungry in the desert where there was no food, and I have raised the dead from their narrow houses, and at my bidding, and before a great multitude of people, a barren fig-tree withered away. All things that this man has done I have done also. And yet they have not crucified me.

Oscar Wilde, 1894

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Ton van Reen

Het Oor van de Maaier

Sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

Ton van Reen: Het Oor van de Maaier

Uit: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Oscar Wilde

Her Voice

The wild bee reels from bough to bough

With his furry coat and his gauzy wing,

Now in a lily-cup, and now

Setting a jacinth bell a-swing,

In his wandering;

Sit closer love: it was here I trow

I made that vow,

Swore that two lives should be like one

As long as the sea-gull loved the sea,

As long as the sunflower sought the sun,-

It shall be, I said, for eternity

‘Twixt you and me!

Dear friend, those times are over and done;

Love’s web is spun.

Look upward where the poplar trees

Sway and sway in the summer air,

Here in the valley never a breeze

Scatters the thistledown, but there

Great winds blow fair

From the mighty murmuring mystical seas,

And the wave-lashed leas.

Look upward where the white gull screams,

What does it see that we do not see?

Is that a star? or the lamp that gleams

On some outward voyaging argosy,

Ah! can it be

We have lived our lives in a land of dreams!

How sad it seems.

Sweet, there is nothing left to say

But this, that love is never lost,

Keen winter stabs the breasts of May

Whose crimson roses burst his frost,

Ships tempest-tossed

Will find a harbour in some bay,

And so we may.

And there is nothing left to do

But to kiss once again, and part,

Nay, there is nothing we should rue,

I have my beauty,-you your Art,

Nay, do not start,

One world was not enough for two

Like me and you.

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

Her Voice

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Rain before dawn

The dull, faint patter in the drooping hours

Drifts in upon my sleep and fills my hair

With damp; the burden of the heavy air

Is strewn upon me where my tired soul cowers,

Shrinking like some lone queen in empty towers

Dying. Blind with unrest I grow aware:

The pounding of broad wings drifts down the stair

And sates me like the heavy scent of flowers.

I lie upon my heart. My eyes like hands

Grip at the soggy pillow. Now the dawn

Tears from her wetted breast the splattered blouse

Of night; lead-eyed and moist she straggles o’er the lawn,

Between the curtains brooding stares and stands

Like some drenched swimmer — Death’s within the house!

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896 – 1940)

Poem: Rain before dawn

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Fitzgerald, F. Scott

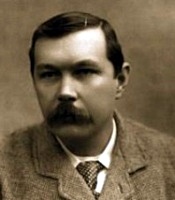

The Red-headed League

The Red-headed League

by Arthur Conan Doyle

I had called upon my friend, Mr. Sherlock Holmes, one day in the autumn of last year, and found him in deep conversation with a very stout, florid-faced, elderly gentleman, with fiery red hair. With an apology for my intrusion, I was about to withdraw, when Holmes pulled me abruptly into the room, and closed the door behind me.

“You could not possibly have come at a better time, my dear Watson,” he said cordially.

“I was afraid that you were engaged.”

“So I am. Very much so.”

“Then I can wait in the next room.”

“Not at all. This gentleman, Mr. Wilson, has been my partner and helper in many of my most successful cases, and I have no doubt that he will be of the utmost use to me in yours also.”

The stout gentleman half rose from his chair, and gave a bob of greeting, with a quick little questioning glance from his small, fat-encircled eyes.

“Try the settee,” said Holmes, relapsing into his armchair, and putting his fingertips together, as was his custom when in judicial moods. “I know, my dear Watson, that you share my love of all that is bizarre and outside the conventions and humdrum routine of every-day life. You have shown your relish for it by the enthusiasm which has prompted you to chronicle, and, if you will excuse my saying so, somewhat to embellish so many of my own little adventures.”

“Your cases have indeed been of the greatest interest to me,” I observed.

“You will remember that I remarked the other day, just before we went into the very simple problem presented by Miss Mary Sutherland, that for strange effects and extraordinary combinations we must go to life itself, which is always far more daring than any effort of the imagination.”

“A proposition which I took the liberty of doubting.”

“You did, Doctor, but none the less you must come round to my view, for otherwise I shall keep on piling fact upon fact on you until your reason breaks down under them and acknowledges me to be right. Now, Mr. Jabez Wilson here has been good enough to call upon me this morning, and to begin a narrative which promises to be one of the most singular which I have listened to for some time. You have heard me remark that the strangest and most unique things are very often connected not with the larger but with the smaller crimes, and occasionally, indeed, where there is room for doubt whether any positive crime has been committed. As far as I have heard, it is impossible for me to say whether the present case is an instance of crime or not, but the course of events is certainly among the most singular that I have ever listened to. Perhaps, Mr. Wilson, you would have the great kindness to recommence your narrative. I ask you, not merely because my friend Dr. Watson has not heard the opening part, but also because the peculiar nature of the story makes me anxious to have every possible detail from your lips. As a rule, when I have heard some slight indication of the course of events, I am able to guide myself by the thousands of other similar cases which occur to my memory. In the present instance I am forced to admit that the facts are, to the best of my belief, unique.”

The portly client puffed out his chest with an appearance of some little pride, and pulled a dirty and wrinkled newspaper from the inside pocket of his greatcoat. As he glanced down the advertisement column, with his head thrust forward, and the paper flattened out upon his knee, I took a good look at the man, and endeavoured, after the fashion of my companion, to read the indications which might be presented by his dress or appearance.

I did not gain very much, however, by my inspection. Our visitor bore every mark of being an average commonplace British tradesman, obese, pompous, and slow. He wore rather baggy gray shepherd’s check trousers, a not overclean black frockcoat, unbuttoned in the front, and a drab waistcoat with a heavy brassy Albert chain, and a square pierced bit of metal dangling down as an ornament. A frayed top hat and a faded brown overcoat with a wrinkled velvet collar lay upon a chair beside him. Altogether, look as I would, there was nothing remarkable about the man save his blazing red head, and the expression of extreme chagrin and discontent upon his features.

Sherlock Holmes’ quick eye took in my occupation, and he shook his head with a smile as he noticed my questioning glances. “Beyond the obvious facts that he has at some time done manual labour, that he takes snuff, that he is a Freemason, that he has been in China, and that he has done a considerable amount of writing lately, I can deduce nothing else.”

Mr. Jabez Wilson started up in his chair, with his forefinger upon the paper, but his eyes upon my companion.

“How, in the name of good fortune, did you know all that, Mr. Holmes?” he asked. “How did you know, for example, that I did manual labour. It’s as true as gospel, for I began as a ship’s carpenter.”

“Your hands, my dear sir. Your right hand is quite a size larger than your left. You have worked with it, and the muscles are more developed.”

“Well, the snuff, then, and the Freemasonry?”

“I won’t insult your intelligence by telling you how I read that, especially as, rather against the strict rules of your order, you use an arc and compass breastpin.”

“Ah, of course, I forgot that. But the writing?”

“What else can be indicated by that right cuff so very shiny for five inches, and the left one with the smooth patch near the elbow where you rest it upon the desk.”

“Well, but China?”

“The fish which you have tattooed immediately above your right wrist could only have been done in China. I have made a small study of tattoo marks, and have even contributed to the literature of the subject. That trick of staining the fishes’ scales of a delicate pink is quite peculiar to China. When, in addition, I see a Chinese coin hanging from your watch-chain, the matter becomes even more simple.”

Mr. Jabez Wilson laughed heavily. “Well, I never!” said he. “I thought at first that you had done something clever, but I see that there was nothing in it after all.”

“I begin to think, Watson,” said Holmes, “that I make a mistake in explaining. ‘Omne ignotum pro magnifico,’ you know, and my poor little reputation, such as it is, will suffer shipwreck if I am so candid. Can you not find the advertisement, Mr. Wilson?”

“Yes, I have got it now,” he answered, with his thick, red finger planted half-way down the column. “Here it is. This is what began it all. You just read it for yourself, sir.”

I took the paper from him, and read as follows:—

“To the Red-Headed League. On account of the bequest of the late Ezekiah Hopkins, of Lebanon, Penn., U.S.A., there is now another vacancy open which entitles a member of the League to a salary of four pounds a week for purely nominal services. All red-headed men who are sound in body and mind, and above the age of twenty-one years, are eligible. Apply in person on Monday, at eleven o’clock, to Duncan Ross, at the offices of the League, 7, Pope’s-court, Fleet-street.”

“What on earth does this mean?” I ejaculated, after I had twice read over the extraordinary announcement.

Holmes chuckled, and wriggled in his chair, as was his habit when in high spirits. “It is a little off the beaten track, isn’t it?” said he. “And now, Mr. Wilson, off you go at scratch, and tell us all about yourself, your household, and the effect which this advertisement had upon your fortunes. You will first make a note, Doctor, of the paper and the date.”

“It is The Morning Chronicle, of April 27, 1890. Just two months ago.”

“Very good. Now, Mr. Wilson?”

“Well, it is just as I have been telling you, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said Jabez Wilson, mopping his forehead, “I have a small pawnbroker’s business at Coburg-square, near the City. It’s not a very large affair, and of late years it has not done more than just give me a living. I used to be able to keep two assistants, but now I only keep one; and I would have a job to pay him, but that he is willing to come for half wages, so as to learn the business.”

“What is the name of this obliging youth?” asked Sherlock Holmes.

“His name is Vincent Spaulding, and he’s not such a youth either. It’s hard to say his age. I should not wish a smarter assistant, Mr. Holmes; and I know very well that he could better himself, and earn twice what I am able to give him. But after all, if he is satisfied, why should I put ideas in his head?”

“Why, indeed? You seem most fortunate in having an employé who comes under the full market price. It is not a common experience among employers in this age. I don’t know that your assistant is not as remarkable as your advertisement.”

“Oh, he has his faults, too,” said Mr. Wilson. “Never was such a fellow for photography. Snapping away with a camera when he ought to be improving his mind, and then diving down into the cellar like a rabbit into its hole to develop his pictures. That is his main fault; but, on the whole, he’s a good worker. There’s no vice in him.”

“He is still with you, I presume?”

“Yes, sir. He and a girl of fourteen, who does a bit of simple cooking, and keeps the place clean—that’s all I have in the house, for I am a widower, and never had any family. We live very quietly, sir, the three of us; and we keep a roof over our heads, and pay our debts, if we do nothing more.

“The first thing that put us out was that advertisement. Spaulding, he came down into the office just this day eight weeks with this very paper in his hand, and he says:—

“‘I wish to the Lord, Mr. Wilson, that I was a red-headed man.’

“‘Why that?’ I asks.

“‘Why,’ says he, ‘here’s another vacancy on the League of the Red-headed Men. It’s worth quite a little fortune to any man who gets it, and I understand that there are more vacancies than there are men, so that the trustees are at their wits’ end what to do with the money. If my hair would only change colour, here’s a nice little crib all ready for me to step into.’

“‘Why, what is it, then?’ I asked. You see, Mr. Holmes, I am a very stay-at-home man, and, as my business came to me instead of my having to go to it, I was often weeks on end without putting my foot over the door-mat. In that way I didn’t know much of what was going on outside, and I was always glad of a bit of news.

“‘Have you never heard of the League of the Red-headed Men?’ he asked, with his eyes open.

“‘Never.’

“‘Why, I wonder at that, for you are eligible yourself for one of the vacancies.’

“‘And what are they worth?’ I asked.

“‘Oh, merely a couple of hundred a year, but the work is slight, and it need not interfere very much with one’s other occupations.’

“Well, you can easily think that that made me prick up my ears, for the business has not been over good for some years, and an extra couple of hundred would have been very handy.

“‘Tell me all about it,’ said I.

“‘Well,’ said he, showing me the advertisement, ‘you can see for yourself that the League has a vacancy, and there is the address where you should apply for particulars. As far as I can make out, the League was founded by an American millionaire, Ezekiah Hopkins, who was very peculiar in his ways. He was himself red-headed, and he had a great sympathy for all red-headed men; so, when he died, it was found that he had left his enormous fortune in the hands of trustees, with instructions to apply the interest to the providing of easy berths to men whose hair is of that colour. From all I hear it is splendid pay, and very little to do.’

“‘But,’ said I, ‘there would be millions of red-headed men who would apply.’

“‘Not so many as you might think,’ he answered. ‘You see it is really confined to Londoners, and to grown men. This American had started from London when he was young, and he wanted to do the old town a good turn. Then, again, I have heard it is no use your applying if your hair is light red, or dark red, or anything but real, bright, blazing, fiery red. Now, if you cared to apply, Mr. Wilson, you would just walk in; but perhaps it would hardly be worth your while to put yourself out of the way for the sake of a few hundred pounds.’

“Now, it is a fact, gentlemen, as you may see for yourselves, that my hair is of a very full and rich tint, so that it seemed to me that, if there was to be any competition in the matter, I stood as good a chance as any man that I had ever met. Vincent Spaulding seemed to know so much about it that I thought he might prove useful, so I just ordered him to put up the shutters for the day, and to come right away with me. He was very willing to have a holiday, so we shut the business up, and started off for the address that was given us in the advertisement.

“I never hope to see such a sight as that again, Mr. Holmes. From north, south, east, and west every man who had a shade of red in his hair had tramped into the City to answer the advertisement. Fleet-street was choked with red-headed folk, and Pope’s-court looked like a coster’s orange barrow. I should not have thought there were so many in the whole country as were brought together by that single advertisement. Every shade of colour they were—straw, lemon, orange, brick, Irish-setter, liver, clay; but, as Spaulding said, there were not many who had the real vivid flame-coloured tint. When I saw how many were waiting, I would have given it up in despair; but Spaulding would not hear of it. How he did it I could not imagine, but he pushed and pulled and butted until he got me through the crowd, and right up to the steps which led to the office. There was a double stream upon the stair, some going up in hope, and some coming back dejected; but we wedged in as well as we could, and soon found ourselves in the office.”

“Your experience has been a most entertaining one,” remarked Holmes, as his client paused and refreshed his memory with a huge pinch of snuff. “Pray continue your very interesting statement.”

“There was nothing in the office but a couple of wooden chairs and a deal table, behind which sat a small man, with a head that was even redder than mine. He said a few words to each candidate as he came up, and then he always managed to find some fault in them which would disqualify them. Getting a vacancy did not seem to be such a very easy matter after all. However, when our turn came, the little man was much more favourable to me than to any of the others, and he closed the door as we entered, so that he might have a private word with us.

“‘This is Mr. Jabez Wilson,’ said my assistant, ‘and he is willing to fill a vacancy in the League.’

“‘And he is admirably suited for it,’ the other answered. ‘He has every requirement. I cannot recall when I have seen anything so fine.’ He took a step backwards, cocked his head on one side, and gazed at my hair until I felt quite bashful. Then suddenly he plunged forward, wrung my hand, and congratulated me warmly on my success.

“‘It would be injustice to hesitate,’ said he. ‘You will, however, I am sure, excuse me for taking an obvious precaution.’ With that he seized my hair in both his hands, and tugged until I yelled with the pain. ‘There is water in your eyes,’ said he, as he released me. ‘I perceive that all is as it should be. But we have to be careful, for we have twice been deceived by wigs and once by paint. I could tell you tales of cobbler’s wax which would disgust you with human nature.’ He stepped over to the window, and shouted through it at the top of his voice that the vacancy was filled. A groan of disappointment came up from below, and the folk all trooped away in different directions, until there was not a red head to be seen except my own and that of the manager.

“‘My name,’ said he, ‘is Mr. Duncan Ross, and I am myself one of the pensioners upon the fund left by our noble benefactor. Are you a married man, Mr. Wilson? Have you a family?’

“I answered that I had not.

“His face fell immediately.

“‘Dear me!’ he said, gravely, ‘that is very serious indeed! I am sorry to hear you say that. The fund was, of course, for the propagation and spread of the red-heads as well as for their maintenance. It is exceedingly unfortunate that you should be a bachelor.’

“My face lengthened at this, Mr. Holmes, for I thought that I was not to have the vacancy after all; but, after thinking it over for a few minutes, he said that it would be all right.

“‘In the case of another,’ said he, ‘the objection might be fatal, but we must stretch a point in favour of a man with such a head of hair as yours. When shall you be able to enter upon your new duties?’

“‘Well, it is a little awkward, for I have a business already,’ said I.

“‘Oh, never mind about that, Mr. Wilson!’ said Vincent Spaulding. ‘I shall be able to look after that for you.’

“‘What would be the hours?’ I asked.

“‘Ten to two.’

“Now a pawnbroker’s business is mostly done of an evening, Mr. Holmes, especially Thursday and Friday evening, which is just before pay-day; so it would suit me very well to earn a little in the mornings. Besides, I knew that my assistant was a good man, and that he would see to anything that turned up.

“‘That would suit me very well,’ said I. ‘And the pay?’

“‘Is four pounds a week.’

“‘And the work?’

“‘Is purely nominal.’

“‘What do you call purely nominal?’

“‘Well, you have to be in the office, or at least in the building, the whole time. If you leave, you forfeit your whole position for ever. The will is very clear upon that point. You don’t comply with the conditions if you budge from the office during that time.’

“‘It’s only four hours a day, and I should not think of leaving,’ said I.

“‘No excuse will avail,’ said Mr. Duncan Ross, ‘neither sickness, nor business, nor anything else. There you must stay, or you lose your billet.’

“‘And the work?’

“‘Is to copy out the “Encyclopædia Britannica.” There is the first volume of it in that press. You must find your own ink, pens, and blotting-paper, but we provide this table and chair. Will you be ready to-morrow?’

“‘Certainly,’ I answered.

“‘Then, good-bye, Mr. Jabez Wilson, and let me congratulate you once more on the important position which you have been fortunate enough to gain.’ He bowed me out of the room, and I went home with my assistant, hardly knowing what to say or do, I was so pleased at my own good fortune.

“Well, I thought over the matter all day, and by evening I was in low spirits again; for I had quite persuaded myself that the whole affair must be some great hoax or fraud, though what its object might be I could not imagine. It seemed altogether past belief that anyone could make such a will, or that they would pay such a sum for doing anything so simple as copying out the ‘Encyclopædia Britannica.’ Vincent Spaulding did what he could to cheer me up, but by bedtime I had reasoned myself out of the whole thing. However, in the morning I determined to have a look at it anyhow, so I bought a penny bottle of ink, and with a quill pen, and seven sheets of foolscap paper, I started off for Pope’s-court.

“Well, to my surprise and delight everything was as right as possible. The table was set out ready for me, and Mr. Duncan Ross was there to see that I got fairly to work. He started me off upon the letter A, and then he left me; but he would drop in from time to time to see that all was right with me. At two o’clock he bade me good-day, complimented me upon the amount that I had written, and locked the door of the office after me.

“This went on day after day, Mr. Holmes, and on Saturday the manager came in and planked down four golden sovereigns for my week’s work. It was the same next week, and the same the week after. Every morning I was there at ten, and every afternoon I left at two. By degrees Mr. Duncan Ross took to coming in only once of a morning, and then, after a time, he did not come in at all. Still, of course, I never dared to leave the room for an instant, for I was not sure when he might come, and the billet was such a good one, and suited me so well, that I would not risk the loss of it.

“Eight weeks passed away like this, and I had written about Abbots, and Archery, and Armour, and Architecture, and Attica, and hoped with diligence that I might get on to the Bs before very long. It cost me something in foolscap, and I had pretty nearly filled a shelf with my writings. And then suddenly the whole business came to an end.”

“To an end?”

“Yes, sir. And no later than this morning. I went to my work as usual at ten o’clock, but the door was shut and locked, with a little square of cardboard hammered on to the middle of the panel with a tack. Here it is, and you can read for yourself.”

He held up a piece of white cardboard, about the size of a sheet of notepaper. It read in this fashion:—

“The Red-Headed League

is

Dissolved.

Oct. 9, 1890.”

Sherlock Holmes and I surveyed this curt announcement and the rueful face behind it, until the comical side of the affair so completely overtopped every other consideration that we both burst out into a roar of laughter.

“I cannot see that there is anything very funny,” cried our client, flushing up to the roots of his flaming head. “If you can do nothing better than laugh at me, I can go elsewhere.”

“No, no,” cried Holmes, shoving him back into the chair from which he had half risen. “I really wouldn’t miss your case for the world. It is most refreshingly unusual. But there is, if you will excuse my saying so, something just a little funny about it. Pray what steps did you take when you found the card upon the door?”

“I was staggered, sir. I did not know what to do. Then I called at the offices round, but none of them seemed to know anything about it. Finally, I went to the landlord, who is an accountant living on the ground floor, and I asked him if he could tell me what had become of the Red-headed League. He said that he had never heard of any such body. Then I asked him who Mr. Duncan Ross was. He answered that the name was new to him.

“‘Well,’ said I, ‘the gentleman at No. 4.’

“‘What, the red-headed man?’

“‘Yes.’

“‘Oh,’ said he, ‘his name was William Morris. He was a solicitor, and was using my room as a temporary convenience until his new premises were ready. He moved out yesterday.’

“‘Where could I find him?’

“‘Oh, at his new offices. He did tell me the address. Yes, 17, King Edward-street, near St. Paul’s.’

“I started off, Mr. Holmes, but when I got to that address it was a manufactory of artificial knee-caps, and no one in it had ever heard of either Mr. William Morris, or Mr. Duncan Ross.”

“And what did you do then?” asked Holmes.

“I went home to Saxe-Coburg-square, and I took the advice of my assistant. But he could not help me in any way. He could only say that if I waited I should hear by post. But that was not quite good enough, Mr. Holmes. I did not wish to lose such a place without a struggle, so, as I had heard that you were good enough to give advice to poor folk who were in need of it, I came right away to you.”

“And you did very wisely,” said Holmes. “Your case is an exceedingly remarkable one, and I shall be happy to look into it. From what you have told me I think that it is possible that graver issues hang from it than might at first sight appear.”

“Grave enough!” said Mr. Jabez Wilson. “Why, I have lost four pound a week.”

“As far as you are personally concerned,” remarked Holmes, “I do not see that you have any grievance against this extraordinary league. On the contrary, you are, as I understand, richer by some thirty pounds, to say nothing of the minute knowledge which you have gained on every subject which comes under the letter A. You have lost nothing by them.”

“No, sir. But I want to find out about them, and who they are, and what their object was in playing this prank—if it was a prank—upon me. It was a pretty expensive joke for them, for it cost them two and thirty pounds.”

“We shall endeavor to clear up these points for you. And, first, one or two questions, Mr. Wilson. This assistant of yours who first called your attention to the advertisement—how long had he been with you?”

“About a month then.”

“How did he come?”

“In answer to an advertisement.”

“Was he the only applicant?”

“No, I had a dozen.”

“Why did you pick him?”

“Because he was handy, and would come cheap.”

“At half wages, in fact.”

“Yes.”

“What is he like, this Vincent Spaulding?”

“Small, stout-built, very quick in his ways, no hair on his face, though he’s not short of thirty. Has a white splash of acid upon his forehead.”

Holmes sat up in his chair in considerable excitement. “I thought as much,” said he. “Have you ever observed that his ears are pierced for earrings?”

“Yes, sir. He told me that a gypsy had done it for him when he was a lad.”

“Hum!” said Holmes, sinking back in deep thought. “He is still with you?”

“Oh, yes, sir; I have only just left him.”

“And has your business been attended to in your absence?”

“Nothing to complain of, sir. There’s never very much to do of a morning.”

“That will do, Mr. Wilson. I shall be happy to give you an opinion upon the subject in the course of a day or two. To-day is Saturday, and I hope that by Monday we may come to a conclusion.”

“Well, Watson,” said Holmes, when our visitor had left us, “what do you make of it all?”

“I make nothing of it,” I answered, frankly. “It is a most mysterious business.”

“As a rule,” said Holmes, “the more bizarre a thing is the less mysterious it proves to be. It is your commonplace, featureless crimes which are really puzzling, just as a commonplace face is the most difficult to identify. But I must be prompt over this matter.”

“What are you going to do then?” I asked.

“To smoke,” he answered. “It is quite a three pipe problem, and I beg that you won’t speak to me for fifty minutes.” He curled himself up in his chair, with his thin knees drawn up to his hawk-like nose, and there he sat with his eyes closed and his black clay pipe thrusting out like the bill of some strange bird. I had come to the conclusion that he had dropped asleep, and indeed was nodding myself, when he suddenly sprang out of his chair withArthur Conan Doyle the gesture of a man who has made up his mind, and put his pipe down upon the mantelpiece.

“Sarasate plays at the St. James’s Hall this afternoon,” he remarked. “What do you think, Watson? Could your patients spare you for a few hours?”

“I have nothing to do to-day. My practice is never very absorbing.”

“Then, put on your hat, and come. I am going through the City first, and we can have some lunch on the way. I observe that there is a good deal of German music on the programme, which is rather more to my taste than Italian or French. It is introspective, and I want to introspect. Come along!”

We travelled by the Underground as far as Aldersgate; and a short walk took us to Saxe-Coburg-square, the scene of the singular story which we had listened to in the morning. It was a poky, little, shabby-genteel place, where four lines of dingy two-storied brick houses looked out into a small railed-in enclosure, where a lawn of weedy grass, and a few clumps of faded laurel bushes made a hard fight against a smoke-laden and uncongenial atmosphere. Three gilt balls and a brown board with “Jabez Wilson” in white letters, upon a corner house, announced the place where our red-headed client carried on his business. Sherlock Holmes stopped in front of it with his head on one side, and looked it all over, with his eyes shining brightly between puckered lids. Then he walked slowly up the street, and then down again to the corner, still looking keenly at the houses. Finally he returned to the pawnbroker’s, and, having thumped vigorously upon the pavement with his stick two or three times, he went up to the door and knocked. It was instantly opened by a bright-looking, clean-shaven young fellow, who asked him to step in.

“Thank you,” said Holmes, “I only wished to ask you how you would go from here to the Strand.”

“Third right, fourth left,” answered the assistant promptly, closing the door.

“Smart fellow, that,” observed Holmes, as we walked away. “He is, in my judgment, the fourth smartest man in London, and for daring I am not sure that he has not a claim to be third. I have known something of him before.”

“Evidently,” said I, “Mr. Wilson’s assistant counts for a good deal in this mystery of the Red-headed League. I am sure that you inquired your way merely in order that you might see him.”

“Not him.”

“What then?”

“The knees of his trousers.”

“And what did you see?”

“What I expected to see.”

“Why did you beat the pavement?”

“My dear Doctor, this is a time for observation, not for talk. We are spies in an enemy’s country. We know something of Saxe-Coburg-square. Let us now explore the parts which lie behind it.”

The road in which we found ourselves as we turned round the corner from the retired Saxe-Coburg-square presented as great a contrast to it as the front of a picture does to the back. It was one of the main arteries which convey the traffic of the City to the north and west. The roadway was blocked with the immense stream of commerce flowing in a double tide inwards and outwards, while the footpaths were black with the hurrying swarm of pedestrians. It was difficult to realize as we looked at the line of fine shops and stately business premises that they really abutted on the other side upon the faded and stagnant square which we had just quitted.

“Let me see,” said Holmes, standing at the corner, and glancing along the line, “I should like just to remember the order of the houses here. It is a hobby of mine to have an exact knowledge of London. There is Mortimer’s, the tobacconist, the little newspaper shop, the Coburg branch of the City and Suburban Bank, the Vegetarian Restaurant, and McFarlane’s carriage-building depôt. That carries us right on to the other block. And now, Doctor, we’ve done our work, so it’s time we had some play. A sandwich, and a cup of coffee, and then off to violin-land, where all is sweetness, and delicacy, and harmony, and there are no red-headed clients to vex us with their conundrums.”

My friend was an enthusiastic musician, being himself not only a very capable performer, but a composer of no ordinary merit. All the afternoon he sat in the stalls wrapped in the most perfect happiness, gently waving his long, thin fingers in time to the music, while his gently smiling face and his languid, dreamy eyes were as unlike those of Holmes the sleuth-hound; Holmes the relentless, keen-witted, ready-handed criminal agent, as it was possible to conceive. In his singular character the dual nature alternately asserted itself, and his extreme exactness and astuteness represented, as I have often thought, the reaction against the poetic and contemplative mood which occasionally predominated in him. The swing of his nature took him from extreme languor to devouring energy; and, as I knew well, he was never so truly formidable as when, for days on end, he had been lounging in his armchair amid his improvisations and his black-letter editions. Then it was that the lust of the chase would suddenly come upon him, and that his brilliant reasoning power would rise to the level of intuition, until those who were unacquainted with his methods would look askance at him as on a man whose knowledge was not that of other mortals. When I saw him that afternoon so enwrapped in the music at St. James’s Hall I felt that an evil time might be coming upon those whom he had set himself to hunt down.

“You want to go home, no doubt, Doctor,” he remarked, as we emerged.

“Yes, it would be as well.”

“And I have some business to do which will take some hours. This business at Coburg-square is serious.”

“Why serious?”

“A considerable crime is in contemplation. I have every reason to believe that we shall be in time to stop it. But to-day being Saturday rather complicates matters. I shall want your help to-night.”

“At what time?”

“Ten will be early enough.”

“I shall be at Baker-street at ten.”

“Very well. And, I say, Doctor! there may be some little danger, so kindly put your army revolver in your pocket.” He waved his hand, turned on his heel, and disappeared in an instant among the crowd.

I trust that I am not more dense than my neighbours, but I was always oppressed with a sense of my own stupidity in my dealings with Sherlock Holmes. Here I had heard what he had heard, I had seen what he had seen, and yet from his words it was evident that he saw clearly not only what had happened, but what was about to happen, while to me the whole business was still confused and grotesque. As I drove home to my house in Kensington I thought over it all, from the extraordinary story of the red-headed copier of the “Encyclopædia” down to the visit to Saxe-Coburg-square, and the ominous words with which he had parted from me. What was this nocturnal expedition, and why should I go armed? Where were we going, and what were we to do? I had the hint from Holmes that this smooth-faced pawnbroker’s assistant was a formidable man—a man who might play a deep game. I tried to puzzle it out, but gave it up in despair, and set the matter aside until night should bring an explanation.

It was a quarter past nine when I started from home and made my way across the Park, and so through Oxford-street to Baker-street. Two hansoms were standing at the door, and, as I entered the passage, I heard the sound of voices from above. On entering his room, I found Holmes in animated conversation with two men, one of whom I recognized as Peter Jones, the official police agent; while the other was a long, thin, sad-faced man, with a very shiny hat and oppressively respectable frock-coat.