Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

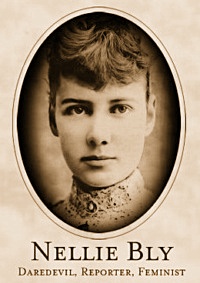

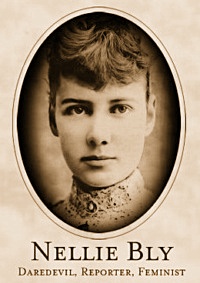

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter II: Preparing for the ordeal)

by Nellie Bly

BUT to return to my work and my mission. After receiving my instructions I returned to my boarding-house, and when evening came I began to practice the role in which I was to make my debut on the morrow. What a difficult task, I thought, to appear before a crowd of people and convince them that I was insane. I had never been near insane persons before in my life, and had not the faintest idea of what their actions were like. And then to be examined by a number of learned physicians who make insanity a specialty, and who daily come in contact with insane people! How could I hope to pass these doctors and convince them that I was crazy? I feared that they could not be deceived. I began to think my task a hopeless one; but it had to be done. So I flew to the mirror and examined my face. I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection. I assure you the sight was not reassuring, even to myself, especially in the dead of night. I tried to turn the gas up higher in hopes that it would raise my courage. I succeeded only partially, but I consoled myself with the thought that in a few nights more I would not be there, but locked up in a cell with a lot of lunatics.

The weather was not cold; but, nevertheless, when I thought of what was to come, wintery chills ran races up and down my back in very mockery of the perspiration which was slowly but surely taking the curl out of my bangs. Between times, practicing before the mirror and picturing my future as a lunatic, I read snatches of improbable and impossible ghost stories, so that when the dawn came to chase away the night, I felt that I was in a fit mood for my mission, yet hungry enough to feel keenly that I wanted my breakfast. Slowly and sadly I took my morning bath and quietly bade farewell to a few of the most precious articles known to modern civilization. Tenderly I put my tooth-brush aside, and, when taking a final rub of the soap, I murmured, “It may be for days, and it may be–for longer.” Then I donned the old clothing I had selected for the occasion.

I was in the mood to look at everything through very serious glasses. It’s just as well to take a last “fond look,” I mused, for who could tell but that the strain of playing crazy, and being shut up with a crowd of mad people, might turn my own brain, and I would never get back. But not once did I think of shirking my mission. Calmly, outwardly at least, I went out to my crazy business.

I first thought it best to go to a boarding-house, and, after securing lodging, confidentially tell the landlady, or lord, whichever it might chance to be, that I was seeking work, and, in a few days after, apparently go insane. When I reconsidered the idea, I feared it would take too long to mature. Suddenly I thought how much easier it would be to go to a boarding-home for working women. I knew, if once I made a houseful of women believe me crazy, that they would never rest until I was out of their reach and in secure quarters.

From a directory I selected the Temporary Home for Females, No. 84 Second Avenue. As I walked down the avenue, I determined that, once inside the Home, I should do the best I could to get started on my journey to Blackwell’s Island and the Insane Asylum.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter II: Preparing for the ordeal)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

NEW YORK: IAN L. MUNRO, PUBLISHER, 24 AND 26 VANDEWATER STREET

NEW YORK: IAN L. MUNRO, PUBLISHER, 24 AND 26 VANDEWATER STREET

WHY ARE THE MADAME MORA’S CORSETS A MARVEL OF COMFORT AND ELEGANCE!?!

Try them and you will Find

WHY they need no breaking in, but feel easy at once.

WHY they are liked by Ladies of full figure.

WHY they do not break down over the hips, and

WHY the celebrated French curved band prevents any wrinkling or stretching at the sides.

WHY dressmakers delight in fitting dresses over them.

WHY merchants say they give better satisfaction than any others.

WHY they take pains to recommend them.

Their popularity has induced many imitations, which are frauds, high at any price. Buy only the genuine, stamped Madame Mora’s. Sold by all leading dealers with this GUARANTEE: that if not perfectly satisfactory upon trial the money will be refunded.

L. KRAUS & CO., Manufacturers, Birmingham, Conn.

INTRODUCTION

SINCE my experiences in Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum were published in the World I have received hundreds of letters in regard to it. The edition containing my story long since ran out, and I have been prevailed upon to allow it to be published in book form, to satisfy the hundreds who are yet asking for copies.

I am happy to be able to state as a result of my visit to the asylum and the exposures consequent thereon, that the City of New York has appropriated $1,000,000 more per annum than ever before for the care of the insane. So I have at least the satisfaction of knowing that the poor unfortunates will be the better cared for because of my work.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter 1: A delicate mission)

by Nellie Bly

On the 22d of September I was asked by the World if I could have myself committed to one of the asylums for the insane in New York, with a view to writing a plain and unvarnished narrative of the treatment of the patients therein and the methods of management, etc. Did I think I had the courage to go through such an ordeal as the mission would demand? Could I assume the characteristics of insanity to such a degree that I could pass the doctors, live for a week among the insane without the authorities there finding out that I was only a “chiel amang ’em takin’ notes?” I said I believed I could. I had some faith in my own ability as an actress and thought I could assume insanity long enough to accomplish any mission intrusted to me. Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island? I said I could and I would. And I did.

My instructions were simply to go on with my work as soon as I felt that I was ready. I was to chronicle faithfully the experiences I underwent, and when once within the walls of the asylum to find out and describe its inside workings, which are always, so effectually hidden by white-capped nurses, as well as by bolts and bars, from the knowledge of the public. “We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time. But I am afraid of that chronic smile of yours,” said the editor. “I will smile no more,” I said, and I went away to execute my delicate and, as I found out, difficult mission.

My instructions were simply to go on with my work as soon as I felt that I was ready. I was to chronicle faithfully the experiences I underwent, and when once within the walls of the asylum to find out and describe its inside workings, which are always, so effectually hidden by white-capped nurses, as well as by bolts and bars, from the knowledge of the public. “We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time. But I am afraid of that chronic smile of yours,” said the editor. “I will smile no more,” I said, and I went away to execute my delicate and, as I found out, difficult mission.

If I did get into the asylum, which I hardly hoped to do, I had no idea that my experiences would contain aught else than a simple tale of life in an asylum.

That such an institution could be mismanaged, and that cruelties could exist ‘neath its roof, I did not deem possible. I always had a desire to know asylum

life more thoroughly–a desire to be convinced that the most helpless of God’s creatures, the insane, were cared for kindly and properly. The many stories I

had read of abuses in such institutions I had regarded as wildly exaggerated or else romances, yet there was a latent desire to know positively.

I shuddered to think how completely the insane were in the power of their keepers, and how one could weep and plead for release, and all of no avail, if

the keepers were so minded. Eagerly I accepted the mission to learn the inside workings of the Blackwell Island Insane Asylum.

“How will you get me out,” I asked my editor, “after I once get in?”

“I do not know,” he replied, “but we will get you out if we have to tell who you are, and for what purpose you feigned insanity–only get in.”

I had little belief in my ability to deceive the insanity experts, and I think my editor had less.

All the preliminary preparations for my ordeal were left to be planned by myself. Only one thing was decided upon, namely, that I should pass under the pseudonym of Nellie Brown, the initials of which would agree with my own name and my linen, so that there would be no difficulty in keeping track of my

movements and assisting me out of any difficulties or dangers I might get into.

There were ways of getting into the insane ward, but I did not know them. I might adopt one of two courses. Either I could feign insanity at the house of friends, and get myself committed on the decision of two competent physicians, or I could go to my goal by way of the police courts.

Nellie practices insanity at home

On reflection I thought it wiser not to inflict myself upon my friends or to get any good-natured doctors to assist me in my purpose. Besides, to get to Blackwell’s Island my friends would have had to feign poverty, and, unfortunately for the end I had in view, my acquaintance with the struggling poor, except my own self, was only very superficial. So I determined upon the plan which led me to the successful accomplishment of my mission. I succeeded in getting committed to the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island, where I spent ten days and nights and had an experience which I shall never forget. I took upon myself to enact the part of a poor, unfortunate crazy girl, and felt it my duty not to shirk any of the disagreeable results that should follow. I became one of the city’s insane wards for that length of time, experienced much, and saw and heard more of the treatment accorded to this helpless class of our population, and when I had seen and heard enough, my release was promptly secured. I left the insane ward with pleasure and regret–pleasure that I was once more able to enjoy the free breath of heaven; regret that I could not have brought with me some of the unfortunate women who lived and suffered with me, and who, I am convinced, are just as sane as I was and am now myself.

But here let me say one thing: From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted the crazier I was thought to be by all except one physician, whose kindness and gentle ways I shall not soon forget.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter 1: A delicate mission)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

His First Operation

His First Operation

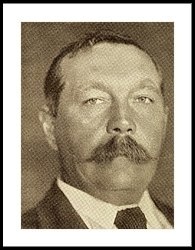

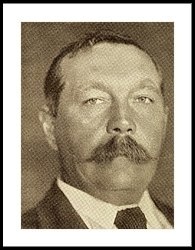

by Arthur Conan Doyle

It was the first day of the winter session, and the third year’s man was walking with the first year’s man. Twelve o’clock was just booming out from the Tron Church.

“Let me see,” said the third year’s man. “You have never seen an operation?”

“Never.”

“Then this way, please. This is Rutherford’s historic bar. A glass of sherry, please, for this gentleman. You are rather sensitive, are you not?”

“My nerves are not very strong, I am afraid.”

“Hum! Another glass of sherry for this gentleman. We are going to an operation now, you know.”

The novice squared his shoulders and made a gallant attempt to look unconcerned.

“Nothing very bad—eh?”

“Well, yes—pretty bad.”

“An—an amputation?”

“No; it’s a bigger affair than that.”

“I think—I think they must be expecting me at home.”

“There’s no sense in funking. If you don’t go to-day, you must to-morrow. Better get it over at once. Feel pretty fit?”

“Oh, yes; all right!” The smile was not a success.

“One more glass of sherry, then. Now come on or we shall be late. I want you to be well in front.”

“Surely that is not necessary.”

“Oh, it is far better! What a drove of students! There are plenty of new men among them. You can tell them easily enough, can’t you? If they were going down to be operated upon themselves, they could not look whiter.”

“I don’t think I should look as white.”

“Well, I was just the same myself. But the feeling soon wears off. You see a fellow with a face like plaster, and before the week is out he is eating his lunch in the dissecting rooms. I’ll tell you all about the case when we get to the theatre.”

The students were pouring down the sloping street which led to the infirmary—each with his little sheaf of note-books in his hand. There were pale, frightened lads, fresh from the high schools, and callous old chronics, whose generation had passed on and left them. They swept in an unbroken, tumultuous stream from the university gate to the hospital. The figures and gait of the men were young, but there was little youth in most of their faces. Some looked as if they ate too little—a few as if they drank too much. Tall and short, tweed-coated and black, round-shouldered, bespectacled, and slim, they crowded with clatter of feet and rattle of sticks through the hospital gate. Now and again they thickened into two lines, as the carriage of a surgeon of the staff rolled over the cobblestones between.

“There’s going to be a crowd at Archer’s,” whispered the senior man with suppressed excitement. “It is grand to see him at work. I’ve seen him jab all round the aorta until it made me jumpy to watch him. This way, and mind the whitewash.”

They passed under an archway and down a long, stone-flagged corridor, with drab-coloured doors on either side, each marked with a number. Some of them were ajar, and the novice glanced into them with tingling nerves. He was reassured to catch a glimpse of cheery fires, lines of white-counterpaned beds, and a profusion of coloured texts upon the wall. The corridor opened upon a small hall, with a fringe of poorly clad people seated all round upon benches. A young man, with a pair of scissors stuck like a flower in his buttonhole and a note-book in his hand, was passing from one to the other, whispering and writing.

“Anything good?” asked the third year’s man.

“You should have been here yesterday,” said the out-patient clerk, glancing up. “We had a regular field day. A popliteal aneurism, a Colles’ fracture, a spina bifida, a tropical abscess, and an elephantiasis. How’s that for a single haul?”

“I’m sorry I missed it. But they’ll come again, I suppose. What’s up with the old gentleman?”

A broken workman was sitting in the shadow, rocking himself slowly to and fro, and groaning. A woman beside him was trying to console him, patting his shoulder with a hand which was spotted over with curious little white blisters.

“It’s a fine carbuncle,” said the clerk, with the air of a connoisseur who describes his orchids to one who can appreciate them. “It’s on his back and the passage is draughty, so we must not look at it, must we, daddy? Pemphigus,” he added carelessly, pointing to the woman’s disfigured hands. “Would you care to stop and take out a metacarpal?”

“No, thank you. We are due at Archer’s. Come on!” and they rejoined the throng which was hurrying to the theatre of the famous surgeon.

The tiers of horseshoe benches rising from the floor to the ceiling were already packed, and the novice as he entered saw vague curving lines of faces in front of him, and heard the deep buzz of a hundred voices, and sounds of laughter from somewhere up above him. His companion spied an opening on the second bench, and they both squeezed into it.

“This is grand!” the senior man whispered. “You’ll have a rare view of it all.”

Only a single row of heads intervened between them and the operating table. It was of unpainted deal, plain, strong, and scrupulously clean. A sheet of brown water-proofing covered half of it, and beneath stood a large tin tray full of sawdust. On the further side, in front of the window, there was a board which was strewed with glittering instruments—forceps, tenacula, saws, canulas, and trocars. A line of knives, with long, thin, delicate blades, lay at one side. Two young men lounged in front of this, one threading needles, the other doing something to a brass coffee-pot-like thing which hissed out puffs of steam.

“That’s Peterson,” whispered the senior, “the big, bald man in the front row. He’s the skin-grafting man, you know. And that’s Anthony Browne, who took a larynx out successfully last winter. And there’s Murphy, the pathologist, and Stoddart, the eye-man. You’ll come to know them all soon.”

“Who are the two men at the table?”

“Nobody—dressers. One has charge of the instruments and the other of the puffing Billy. It’s Lister’s antiseptic spray, you know, and Archer’s one of the carbolic-acid men. Hayes is the leader of the cleanliness-and-cold-water school, and they all hate each other like poison.”

A flutter of interest passed through the closely packed benches as a woman in petticoat and bodice was led in by two nurses. A red woolen shawl was draped over her head and round her neck. The face which looked out from it was that of a woman in the prime of her years, but drawn with suffering, and of a peculiar beeswax tint. Her head drooped as she walked, and one of the nurses, with her arm round her waist, was whispering consolation in her ear. She gave a quick side-glance at the instrument table as she passed, but the nurses turned her away from it.

“What ails her?” asked the novice.

“Cancer of the parotid. It’s the devil of a case; extends right away back behind the carotids. There’s hardly a man but Archer would dare to follow it. Ah, here he is himself!”

As he spoke, a small, brisk, iron-grey man came striding into the room, rubbing his hands together as he walked. He had a clean-shaven face, of the naval officer type, with large, bright eyes, and a firm, straight mouth. Behind him came his big house-surgeon, with his gleaming pince-nez, and a trail of dressers, who grouped themselves into the corners of the room.

“Gentlemen,” cried the surgeon in a voice as hard and brisk as his manner, “we have here an interesting case of tumour of the parotid, originally cartilaginous but now assuming malignant characteristics, and therefore requiring excision. On to the table, nurse! Thank you! Chloroform, clerk! Thank you! You can take the shawl off, nurse.”

The woman lay back upon the water-proofed pillow, and her murderous tumour lay revealed. In itself it was a pretty thing—ivory white, with a mesh of blue veins, and curving gently from jaw to chest. But the lean, yellow face and the stringy throat were in horrible contrast with the plumpness and sleekness of this monstrous growth. The surgeon placed a hand on each side of it and pressed it slowly backwards and forwards.

“Adherent at one place, gentlemen,” he cried. “The growth involves the carotids and jugulars, and passes behind the ramus of the jaw, whither we must be prepared to follow it. It is impossible to say how deep our dissection may carry us. Carbolic tray. Thank you! Dressings of carbolic gauze, if you please! Push the chloroform, Mr. Johnson. Have the small saw ready in case it is necessary to remove the jaw.”

The patient was moaning gently under the towel which had been placed over her face. She tried to raise her arms and to draw up her knees, but two dressers restrained her. The heavy air was full of the penetrating smells of carbolic acid and of chloroform. A muffled cry came from under the towel, and then a snatch of a song, sung in a high, quavering, monotonous voice:

“He says, says he,

If you fly with me

You’ll be mistress of the ice-cream van.

You’ll be mistress of the——”

It mumbled off into a drone and stopped. The surgeon came across, still rubbing his hands, and spoke to an elderly man in front of the novice.

“Narrow squeak for the Government,” he said.

“Oh, ten is enough.”

“They won’t have ten long. They’d do better to resign before they are driven to it.”

“Oh, I should fight it out.”

“What’s the use. They can’t get past the committee even if they got a vote in the House. I was talking to——”

“Patient’s ready, sir,” said the dresser.

“Talking to McDonald—but I’ll tell you about it presently.” He walked back to the patient, who was breathing in long, heavy gasps. “I propose,” said he, passing his hand over the tumour in an almost caressing fashion, “to make a free incision over the posterior border, and to take another forward at right angles to the lower end of it. Might I trouble you for a medium knife, Mr. Johnson?”

The novice, with eyes which were dilating with horror, saw the surgeon pick up the long, gleaming knife, dip it into a tin basin, and balance it in his fingers as an artist might his brush. Then he saw him pinch up the skin above the tumour with his left hand. At the sight his nerves, which had already been tried once or twice that day, gave way utterly. His head swain round, and he felt that in another instant he might faint. He dared not look at the patient. He dug his thumbs into his ears lest some scream should come to haunt him, and he fixed his eyes rigidly upon the wooden ledge in front of him. One glance, one cry, would, he knew, break down the shred of self-possession which he still retained. He tried to think of cricket, of green fields and rippling water, of his sisters at home—of anything rather than of what was going on so near him.

And yet somehow, even with his ears stopped up, sounds seemed to penetrate to him and to carry their own tale. He heard, or thought that he heard, the long hissing of the carbolic engine. Then he was conscious of some movement among the dressers. Were there groans, too, breaking in upon him, and some other sound, some fluid sound, which was more dreadfully suggestive still? His mind would keep building up every step of the operation, and fancy made it more ghastly than fact could have been. His nerves tingled and quivered. Minute by minute the giddiness grew more marked, the numb, sickly feeling at his heart more distressing. And then suddenly, with a groan, his head pitching forward, and his brow cracking sharply upon the narrow wooden shelf in front of him, he lay in a dead faint.

When he came to himself, he was lying in the empty theatre, with his collar and shirt undone. The third year’s man was dabbing a wet sponge over his face, and a couple of grinning dressers were looking on.

“All right,” cried the novice, sitting up and rubbing his eyes. “I’m sorry to have made an ass of myself.”

“Well, so I should think,” said his companion.

“What on earth did you faint about?”

“I couldn’t help it. It was that operation.”

“What operation?”

“Why, that cancer.”

There was a pause, and then the three students burst out laughing. “Why, you juggins!” cried the senior man, “there never was an operation at all! They found the patient didn’t stand the chloroform well, and so the whole thing was off. Archer has been giving us one of his racy lectures, and you fainted just in the middle of his favourite story.”

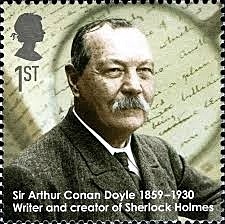

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

His First Operation (#02)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Beat Generation

Beat Generation

Until 3 October 2016

The Centre Pompidou is to present Beat Generation, a novel retrospective dedicated to the literary and artistic movement born in the late 1940s that would exert an ever-growing influence for the next two decades. The theme will be reflected in all the Centre’s activities, with a rich programme of events devised in collaboration with the Bibliothèque Public d’Information and Ircam: readings, concerts, discussions, film screenings, a colloquium, a young people’s programme at Studio 13/16, etc.

Foreshadowing the youth culture and the cultural and sexual liberation of the 1960s, the emergence of the Beat Generation in the years following the Second World War, just as the Cold War was setting in, scandalised a puritan and Mc Carthyite America. Then seen as subversive rebels, the Beats appear today as the representatives of one of the most important cultural movements of the 20th century – a movement the Centre Pompidou’s survey will examine in all its breadth and geographical amplitude, from New York to Los Angeles, from Paris to Tangier.

The Centre Pompidou’s exhibition maps both the shifting geographical focus of the movement and its ever-shifting contours. For the artistic practices of the Beat Generation – readings, performances, concerts and films – testify to a breaking down of artistic boundaries and a desire for interdisciplinary collaboration that puts the singularity of the artist into question. Alongside notable visual artists, mostly representative of the California scene (Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, George Herms, Jay DeFeo, Jess…), an important place is given to the literary dimension of the movement, to spoken poetry in its relationship to jazz, and more particularly to the Black American poetry (LeRoi Jones, Bob Kaufman…) that remains largely unknown in Europe, like the magazines in which it circulated (Beatitude, Umbra…). Photography was also an important medium, represented here by the productions of Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs – mostly portraits – and a substantial body of photographs by Robert Frank (Les Américains, From the Bus…), Fred McDarrah, and John Cohen, all taken during the shooting of Pull my Daisy, as well as work by Harold Chapman, who chronicled the life of the Beat Hotel in Paris between 1958 and 1963. The same was true of the films (Christopher MacLaine, Bruce Baillie, Stan Brakhage, Ron Rice…) that would both reflect and document the history and development of the movement.

Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris until October 3, 2016

New publication:

New publication:

Beat generation – exhibition album

Movement of literary and artistic inspiration born in the United States in the 1950s, at the initiative of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation has profoundly influenced contemporary creation.

The book displays the different artworks exhibited along with short explanatory essays. A clear and precise album suitable for a large audience.

Bilingual version French / English.

Binding: Softbound

Language: Bilingual French / English

EAN 9782844267467

Number of pages 60

Number of illustrations 60

Publication date 15/06/2016

Dimensions 27 x 27 cm

Author: Philippe-Alain Michaud

Publisher: Centre Pompidou

€9.50

# Information and schedule about the Beat Generation exhibition on website Centre Pompidou

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Beat Generation Archives, - Book News, Burroughs, William S., DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, DRUGS & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Ginsberg, Allen, Kerouac, Jack, Literaire sporen, LITERARY MAGAZINES

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Table of Contents

The Preface

Behind the Times. (#01)

His First Operation. (#02)

A Straggler of ‘15. (#03)

The Third Generation. (#04)

A False Start. (#05)

The Curse of Eve. (#06)

Sweethearts. (#07)

A Physiologist’s Wife. (#08)

The Case of Lady Sannox. (#09)

A Question of Diplomacy. (#10)

A Medical Document. (#11)

Lot No. 249. (#12)

The Los Amigos Fiasco. (#13)

The Doctors of Hoyland. (#14)

The Surgeon Talks. (#15)

The Preface.

[Being an extract from a long and animated correspondence with a friend in America.]

I quite recognise the force of your objection that an invalid or a woman in weak health would get no good from stories which attempt to treat some features of medical life with a certain amount of realism. If you deal with this life at all, however, and if you are anxious to make your doctors something more than marionettes, it is quite essential that you should paint the darker side, since it is that which is principally presented to the surgeon or physician. He sees many beautiful things, it is true, fortitude and heroism, love and self-sacrifice; but they are all called forth (as our nobler qualities are always called forth) by bitter sorrow and trial. One cannot write of medical life and be merry over it.

Then why write of it, you may ask? If a subject is painful why treat it at all? I answer that it is the province of fiction to treat painful things as well as cheerful ones. The story which wiles away a weary hour fulfils an obviously good purpose, but not more so, I hold, than that which helps to emphasise the graver side of life. A tale which may startle the reader out of his usual grooves of thought, and shocks him into seriousness, plays the part of the alterative and tonic in medicine, bitter to the taste but bracing in the result. There are a few stories in this little collection which might have such an effect, and I have so far shared in your feeling that I have reserved them from serial publication. In book-form the reader can see that they are medical stories, and can, if he or she be so minded, avoid them.

Yours very truly,

A. CONAN DOYLE

P.S.—You ask about the Red Lamp. It is the usual sign of the general practitioner in England.

Behind the Times

Behind the Times

by Arthur Conan Doyle

My first interview with Dr. James Winter was under dramatic circumstances. It occurred at two in the morning in the bedroom of an old country house. I kicked him twice on the white waistcoat and knocked off his gold spectacles, while he with the aid of a female accomplice stifled my angry cries in a flannel petticoat and thrust me into a warm bath. I am told that one of my parents, who happened to be present, remarked in a whisper that there was nothing the matter with my lungs. I cannot recall how Dr. Winter looked at the time, for I had other things to think of, but his description of my own appearance is far from flattering. A fluffy head, a body like a trussed goose, very bandy legs, and feet with the soles turned inwards—those are the main items which he can remember.

From this time onwards the epochs of my life were the periodical assaults which Dr. Winter made upon me. He vaccinated me; he cut me for an abscess; he blistered me for mumps. It was a world of peace and he the one dark cloud that threatened. But at last there came a time of real illness—a time when I lay for months together inside my wickerwork-basket bed, and then it was that I learned that that hard face could relax, that those country-made creaking boots could steal very gently to a bedside, and that that rough voice could thin into a whisper when it spoke to a sick child.

And now the child is himself a medical man, and yet Dr. Winter is the same as ever. I can see no change since first I can remember him, save that perhaps the brindled hair is a trifle whiter, and the huge shoulders a little more bowed. He is a very tall man, though he loses a couple of inches from his stoop. That big back of his has curved itself over sick beds until it has set in that shape. His face is of a walnut brown, and tells of long winter drives over bleak country roads, with the wind and the rain in his teeth. It looks smooth at a little distance, but as you approach him you see that it is shot with innumerable fine wrinkles like a last year’s apple. They are hardly to be seen when he is in repose; but when he laughs his face breaks like a starred glass, and you realise then that though he looks old, he must be older than he looks.

How old that is I could never discover. I have often tried to find out, and have struck his stream as high up as George IV and even the Regency, but without ever getting quite to the source. His mind must have been open to impressions very early, but it must also have closed early, for the politics of the day have little interest for him, while he is fiercely excited about questions which are entirely prehistoric. He shakes his head when he speaks of the first Reform Bill and expresses grave doubts as to its wisdom, and I have heard him, when he was warmed by a glass of wine, say bitter things about Robert Peel and his abandoning of the Corn Laws. The death of that statesman brought the history of England to a definite close, and Dr. Winter refers to everything which had happened since then as to an insignificant anticlimax.

But it was only when I had myself become a medical man that I was able to appreciate how entirely he is a survival of a past generation. He had learned his medicine under that obsolete and forgotten system by which a youth was apprenticed to a surgeon, in the days when the study of anatomy was often approached through a violated grave. His views upon his own profession are even more reactionary than in politics. Fifty years have brought him little and deprived him of less. Vaccination was well within the teaching of his youth, though I think he has a secret preference for inoculation. Bleeding he would practise freely but for public opinion. Chloroform he regards as a dangerous innovation, and he always clicks with his tongue when it is mentioned. He has even been known to say vain things about Laennec, and to refer to the stethoscope as “a new-fangled French toy.” He carries one in his hat out of deference to the expectations of his patients, but he is very hard of hearing, so that it makes little difference whether he uses it or not.

He reads, as a duty, his weekly medical paper, so that he has a general idea as to the advance of modern science. He always persists in looking upon it as a huge and rather ludicrous experiment. The germ theory of disease set him chuckling for a long time, and his favourite joke in the sick room was to say, “Shut the door or the germs will be getting in.” As to the Darwinian theory, it struck him as being the crowning joke of the century. “The children in the nursery and the ancestors in the stable,” he would cry, and laugh the tears out of his eyes.

He is so very much behind the day that occasionally, as things move round in their usual circle, he finds himself, to his bewilderment, in the front of the fashion. Dietetic treatment, for example, had been much in vogue in his youth, and he has more practical knowledge of it than any one whom I have met. Massage, too, was familiar to him when it was new to our generation. He had been trained also at a time when instruments were in a rudimentary state, and when men learned to trust more to their own fingers. He has a model surgical hand, muscular in the palm, tapering in the fingers, “with an eye at the end of each.” I shall not easily forget how Dr. Patterson and I cut Sir John Sirwell, the County Member, and were unable to find the stone. It was a horrible moment. Both our careers were at stake. And then it was that Dr. Winter, whom we had asked out of courtesy to be present, introduced into the wound a finger which seemed to our excited senses to be about nine inches long, and hooked out the stone at the end of it. “It’s always well to bring one in your waistcoat-pocket,” said he with a chuckle, “but I suppose you youngsters are above all that.”

We made him president of our branch of the British Medical Association, but he resigned after the first meeting. “The young men are too much for me,” he said. “I don’t understand what they are talking about.” Yet his patients do very well. He has the healing touch—that magnetic thing which defies explanation or analysis, but which is a very evident fact none the less. His mere presence leaves the patient with more hopefulness and vitality. The sight of disease affects him as dust does a careful housewife. It makes him angry and impatient. “Tut, tut, this will never do!” he cries, as he takes over a new case. He would shoo Death out of the room as though he were an intrusive hen. But when the intruder refuses to be dislodged, when the blood moves more slowly and the eyes grow dimmer, then it is that Dr. Winter is of more avail than all the drugs in his surgery. Dying folk cling to his hand as if the presence of his bulk and vigour gives them more courage to face the change; and that kindly, windbeaten face has been the last earthly impression which many a sufferer has carried into the unknown.

When Dr. Patterson and I—both of us young, energetic, and up-to-date—settled in the district, we were most cordially received by the old doctor, who would have been only too happy to be relieved of some of his patients. The patients themselves, however, followed their own inclinations—which is a reprehensible way that patients have—so that we remained neglected, with our modern instruments and our latest alkaloids, while he was serving out senna and calomel to all the countryside. We both of us loved the old fellow, but at the same time, in the privacy of our own intimate conversations, we could not help commenting upon this deplorable lack of judgment. “It’s all very well for the poorer people,” said Patterson. “But after all the educated classes have a right to expect that their medical man will know the difference between a mitral murmur and a bronchitic rale. It’s the judicial frame of mind, not the sympathetic, which is the essential one.”

I thoroughly agreed with Patterson in what he said. It happened, however, that very shortly afterwards the epidemic of influenza broke out, and we were all worked to death. One morning I met Patterson on my round, and found him looking rather pale and fagged out. He made the same remark about me. I was, in fact, feeling far from well, and I lay upon the sofa all the afternoon with a splitting headache and pains in every joint. As evening closed in, I could no longer disguise the fact that the scourge was upon me, and I felt that I should have medical advice without delay. It was of Patterson, naturally, that I thought, but somehow the idea of him had suddenly become repugnant to me. I thought of his cold, critical attitude, of his endless questions, of his tests and his tappings. I wanted something more soothing—something more genial.

“Mrs. Hudson,” said I to my housekeeper, “would you kindly run along to old Dr. Winter and tell him that I should be obliged to him if he would step round?”

She was back with an answer presently. “Dr. Winter will come round in an hour or so, sir; but he has just been called in to attend Dr. Patterson.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

Behind the Times. (#01)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Ooit ’n volmaakt mens ontmoet? En. . . . . beviel ‘t?

Ooit ’n volmaakt mens ontmoet? En. . . . . beviel ‘t?

Met deze slogan presenteert Het Dolhuys de tentoonstelling ‘De Maakbare Mens’.

Op eigenzinnige wijze stelt het museum de maakbaarheid ter discussie.

De Maakbare Mens

Tot 10 maart 2017

De expositie is ontworpen door Kossmann.dejong en door het hele gebouw te zien.

Veel Nederlanders willen vandaag de dag volmaakt zijn. We streven naar een gezonde geest, vlekkeloos gedrag en een perfect lichaam. Dagelijks posten we massaal selfies op Facebook, we scheppen een ideaal beeld van onszelf. Maar hoe lang kunnen we nog blijven voldoen aan deze hoge eisen? Mensen die dat niet kunnen, vallen buiten de boot.

De ‘onvolmaakten’ horen er niet bij, zijn gek, beperkt, eng, zielig of ziek. Maar om echt succesvol te zijn, denk aan beroemdheden, kunstenaars en wetenschappers, moet je dan juist niet afwijken van de norm?

Bij binnenkomst maakt de bezoeker een selfie en neemt gedurende de tentoonstelling zijn eigen ‘maakbaarheid’ onder de loep. Hij ontmoet een breed scala aan bijzondere, creatieve geesten, mensen die anders functioneren dan doorsnee. Denk aan de succesvolle schrijfster Myrthe van de Meer, de kunstenaars Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, Willem van Genk en Anton Heijboer. Aan de hand van kunstwerken, films en fotografie krijgt het publiek een kijkje in hun geest. ,,Hoe gek het ook klinkt, die depressie had ik tenminste nog. Ook al was hij de vijand, ik kende hem tenminste. Maar wat zou er van mij overblijven als ze die weg zou halen?’’ aldus Myrthe van der Meer. Of, zoals Munch het formuleert: ,,Waarom was ik niet zoals alle anderen? Waarom ben ik geboren – iets waar ik niet om heb gevraagd? Dit noodlot en daar over na te denken zijn de basis van mijn kunst.’’ Ook voor Munch was gekte de bron van succes.

Bij binnenkomst maakt de bezoeker een selfie en neemt gedurende de tentoonstelling zijn eigen ‘maakbaarheid’ onder de loep. Hij ontmoet een breed scala aan bijzondere, creatieve geesten, mensen die anders functioneren dan doorsnee. Denk aan de succesvolle schrijfster Myrthe van de Meer, de kunstenaars Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, Willem van Genk en Anton Heijboer. Aan de hand van kunstwerken, films en fotografie krijgt het publiek een kijkje in hun geest. ,,Hoe gek het ook klinkt, die depressie had ik tenminste nog. Ook al was hij de vijand, ik kende hem tenminste. Maar wat zou er van mij overblijven als ze die weg zou halen?’’ aldus Myrthe van der Meer. Of, zoals Munch het formuleert: ,,Waarom was ik niet zoals alle anderen? Waarom ben ik geboren – iets waar ik niet om heb gevraagd? Dit noodlot en daar over na te denken zijn de basis van mijn kunst.’’ Ook voor Munch was gekte de bron van succes.

Voor het eerst in Nederland zijn er tekeningen en fotografie te zien van de internationale kunstenaars Michelle Sank, Bryan Saunders en Suzan Aldworth die tonen hoe ver je kunt gaan in de perfectie van lichaam en geest. Nieuw werk van de Nederlandse fotografe Sofie Knijff toont de schoonheid van mensen met een verstandelijke beperking. In samenwerking met het Liliane Fonds laten jonge, internationale talenten zien hoe zij geïnspireerd raken door hun beperking.

Een bezoek aan ‘De Maakbare Mens’ eindigt met een blik in de spiegel waar je ‘een selfie maakt van je geest’. Kijk je nu anders naar je zelf? Onvolmaakt is zo gek nog niet..

# meer info op website van museum het dolhuys

tot 10 maart 2017

het dolhuys

museum van de geest

schotersingel 2

2021 ge haarlem

023 5410670

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, DRUGS & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, MONTAIGNE, Vincent van Gogh

Voorstelling: Ongerijmd

Voorstelling: Ongerijmd

Op 13 mrt van 15:00 tot 16:15

Wanneer ben je niet meer verantwoordelijk voor wat je doet, zegt of schrijft?

Als je als ‘s Neerlands grootste dichter je eigen gedachten niet op een rijtje hebt, wat betekenen alle lofuitingen dan nog? Als je een moord pleegt, maar ontoerekeningsvatbaar wordt verklaard, kunnen we je gedichten dan nog wel serieus nemen?

‘Ongerijmd’ is een poëtisch onderzoek naar de betekenis van ontoerekeningsvatbaarheid, aan de hand van het tumultueuze leven van Gerrit Achterberg. Een chaotische poging om overzicht en structuur te scheppen.

Tekst

Frank Siera

Regie

Arjen Arnoldussen

Spel

Studententoneelvereniging Cuculum:

Jessica Angevare

Jaap Bierman

Sascha Bol

Ruben Bosch

Youri Gorissen

Nina Lak

Rick Snelderwaard

Michelle Verhey

Muzikale Begeleiding

Emma Rekers en Clara de Mik

Zondag 13 maart 15.00 uur in museum Het Dolhuys, Schotersingel 2, Haarlem

# meer info op website van museum het dolhuys

tot 10 maart 2017

het dolhuys

museum van de geest

schotersingel 2

2021 ge haarlem

023 5410670

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Achterberg, Gerrit, Art & Literature News, DRUGS & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, THEATRE

William Ernest Henley

(1849 – 1903)

Suicide

Staring corpselike at the ceiling,

See his harsh, unrazored features,

Ghastly brown against the pillow,

And his throat—so strangely bandaged!

Lack of work and lack of victuals,

A debauch of smuggled whisky,

And his children in the workhouse

Made the world so black a riddle

That he plunged for a solution;

And, although his knife was edgeless,

He was sinking fast towards one,

When they came, and found, and saved him.

Stupid now with shame and sorrow,

In the night I hear him sobbing.

But sometimes he talks a little.

He has told me all his troubles.

In his broad face, tanned and bloodless,

White and wild his eyeballs glisten;

And his smile, occult and tragic,

Yet so slavish, makes you shudder!

William Ernest Henley poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY, Suicide

![]() Een indrukwekkend en tegelijkertijd confronterend tijdsdocument, waarin de pijnlijke gevolgen van de economische crisis, die sinds 2008 de wereld in zijn greep houdt, zijn opgetekend.

Een indrukwekkend en tegelijkertijd confronterend tijdsdocument, waarin de pijnlijke gevolgen van de economische crisis, die sinds 2008 de wereld in zijn greep houdt, zijn opgetekend.

Door de ogen van grafisch ontwerper Richard Sluijs – bij aanvang nog een relatieve buitenstaander in een land dat de dans leek te ontspringen – wordt het persoonlijke leed dat velen trof op monumentale wijze in beeld gebracht. Een verzameling verhalen van mensen die hun ellende niet langer konden verdragen, en zelfmoord als enige uitweg uit hun problemen zagen.

Het boek is een in memoriam voor alle slachtoffers van de crisis, en tegelijkertijd vormt het een kritisch tegengeluid voor de boodschap die politici, bankiers en economen propageren dat het strenge bezuinigingsbeleid zijn vruchten begint af te werpen en alles weldra weer bij het oude zal zijn. Want dat voor vele nabestaanden het leven nooit meer hetzelfde zal zijn, werd helaas ook voor de schrijver de trieste realiteit toen het boek na 6 jaar research bijna gereed was.

![]()

THE COMPLETE LEXICON OF CRISIS RELATED SUICIDES 2008-2013 VOLUME 1

Auteur: Richard Sluijs

Jaartal: 2014-11-20

Afmetingen: 15,5 x 24,5 cm, 6 cm dik

Pagina’s: 712 pagina’s met witte bedrukking

ISBN: 978-94-91525-37-7

Uitvoering: Hardcover, rood linnen, genaaid gebrocheerd, zwart op snee, zwart leeslint

NUR: 740

34,- EURO

Uitgeverij: d’jonge Hond / Komma

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, Galerie des Morts, Suicide

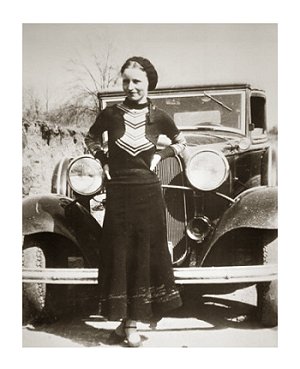

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker

(1910 – 1934)

The story of “Suicide Sal”

We each of us have a good “alibi”

For being down here in the “joint”

But few of them really are justified

If you get right down to the point.

You’ve heard of a woman’s glory

Being spent on a “downright cur”

Still you can’t always judge the story

As true, being told by her.

As long as I’ve stayed on this “island”

And heard “confidence tales” from each “gal”

Only one seemed interesting and truthful-

The story of “Suicide Sal”.

Now “Sal” was a gal of rare beauty,

Though her features were coarse and tough;

She never once faltered from duty

To play on the “up and up”.

“Sal” told me this tale on the evening

Before she was turned out “free”

And I’ll do my best to relate it

Just as she told it to me:

I was born on a ranch in Wyoming;

Not treated like Helen of Troy,

I was taught that “rods were rulers”

And “ranked” as a greasy cowboy.

Then I left my old home for the city

To play in its mad dizzy whirl,

Not knowing how little of pity

It holds for a country girl.

There I fell for “the line” of a “henchman”

A “professional killer” from “Chi”

I couldn’t help loving him madly,

For him even I would die.

One year we were desperately happy

Our “ill gotten gains” we spent free,

I was taught the ways of the “underworld”

Jack was just like a “god” to me.

I got on the “F.B.A.” payroll

To get the “inside lay” of the “job”

The bank was “turning big money”!

It looked like a “cinch for the mob”.

Eighty grand without even a “rumble”-

Jack was last with the “loot” in the door,

When the “teller” dead-aimed a revolver

From where they forced him to lie on the floor.

I knew I had only a moment-

He would surely get Jack as he ran,

So I “staged” a “big fade out” beside him

And knocked the forty-five out of his hand.

They “rapped me down big” at the station,

And informed me that I’d get the blame

For the “dramatic stunt” pulled on the “teller”

Looked to them, too much like a “game”.

The “police” called it a “frame-up”

Said it was an “inside job”

But I steadily denied any knowledge

Or dealings with “underworld mobs”.

The “gang” hired a couple of lawyers,

The best “fixers” in any mans town,

But it takes more than lawyers and money

When Uncle Sam starts “shaking you down”.

I was charged as a “scion of gangland”

And tried for my wages of sin,

The “dirty dozen” found me guilty-

From five to fifty years in the pen.

I took the “rap” like good people,

And never one “squawk” did I make

Jack “dropped himself” on the promise

That we make a “sensational break”.

Well, to shorten a sad lengthy story,

Five years have gone over my head

Without even so much as a letter-

At first I thought he was dead.

But not long ago I discovered;

From a gal in the joint named Lyle,

That Jack and his “moll” had “got over”

And were living in true “gangster style”.

If he had returned to me sometime,

Though he hadn’t a cent to give

I’d forget all the hell that he’s caused me,

And love him as long as I lived.

But there’s no chance of his ever coming,

For he and his moll have no fears

But that I will die in this prison,

Or “flatten” this fifty years.

Tommorow I’ll be on the “outside”

And I’ll “drop myself” on it today,

I’ll “bump ’em if they give me the “hotsquat”

On this island out here in the bay…

The iron doors swung wide next morning

For a gruesome woman of waste,

Who at last had a chance to “fix it”

Murder showed in her cynical face.

Not long ago I read in the paper

That a gal on the East Side got “hot”

And when the smoke finally retreated,

Two of gangdom were found “on the spot”.

It related the colorful story

Of a “jilted gangster gal”

Two days later, a “sub-gun” ended

The story of “Suicide Sal”.

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker (October 1, 1910 – May 23, 1934) and Clyde Chestnut Barrow (March 24, 1909 – May 23, 1934) were well-known (as Bonnie & Clyde) American outlaws and bankrobbers. They were both killed in a police ambush on May 23, 1934. Bonnie Parker wrote most of her poems, while in jail, in a little notebook she had obtained from The First National Bank of Burkburnett, Texas.

Bonnie Parker poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Suicide, Western Fiction

Van Gogh / Artaud. The Man Suicided by Society ♦ A few days before the opening of a van Gogh exhibition in Paris in 1947, gallery owner Pierre Loeb suggested that Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) write about the painter. Challenging the thesis of alienation, Artaud was determined to show how van Gogh’s exceptional lucidity made lesser minds uncomfortable.

Van Gogh / Artaud. The Man Suicided by Society ♦ A few days before the opening of a van Gogh exhibition in Paris in 1947, gallery owner Pierre Loeb suggested that Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) write about the painter. Challenging the thesis of alienation, Artaud was determined to show how van Gogh’s exceptional lucidity made lesser minds uncomfortable.

Wishing to prevent him from uttering certain “intolerable truths”, those who were disturbed by his painting drove him to suicide.

Based on the categories and the unusual designations put forward by Artaud in Van Gogh, the Man Suicided by Society, the exhibition will comprise some forty paintings, a selection of van Gogh’s drawings and letters, together with graphic works by the poet-illustrator.

The title of the exhibition is based on the title of Antonin Artaud’s book, Van Gogh the Man Suicided by Society Editions Gallimard, 1974

Musée d’Orsay Paris – until 6 july 2014

Publication:

Vincent Van Gogh-Antonin Artaud :

le suicidé de la société

Number of pages 192 , €39.00

EAN 9782370740038

Dimensions 34 x 25 cm

Publisher Skira Flammarion

Museum Musée d’Orsay

Language French

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Antonin Artaud, Art & Literature News, Artaud, Antonin, Suicide, Vincent van Gogh, Vincent van Gogh

William Blake

(1757-1827)

A POISON TREE

Was angry with my friend:

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

And I watered it in fears,

Night and morning with my tears;

And I sunnèd it with smiles,

And with soft deceitful wiles.

And it grew both day and night,

Till it bore an apple bright;

And my foe beheld it shine,

And he knew that it was mine,

And into my garden stole,

When the night had veiled the pole:

In the morning glad I see

My foe outstretched beneath the tree.

William Blake poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blake, William, DRUGS & MEDICINE & LITERATURE

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature