Fleurs du Mal Magazine

François Coppée

(1842-1908)

Le Rêve du Poète

Ce serait sur les bords de la Seine. Je vois

Notre chalet, voilé par un bouquet de bois.

Un hamac au jardin, un bateau sur le fleuve.

Pas d’autre compagnon qu’un chien de Terre-Neuve

Qu’elle aimerait et dont je serais bien jaloux.

Des faïences à fleurs pendraient après des clous ;

Puis beaucoup de chapeaux de paille et des ombrelles.

Sous leurs papiers chinois les murs seraient si frêles

Que même, en travaillant à travers la cloison

Je l’entendrais toujours errer par la maison

Et traîner dans l’étroit escalier sa pantoufle.

Les miroirs de ma chambre auraient senti son souffle

Et souvent réfléchi son visage, charmés.

Elle aurait effleuré tout de ses doigts aimés.

Et ces bruits, ces reflets, ces parfums, venant d’elle,

Ne me permettraient pas d’être une heure infidèle.

Enfin, quand, poursuivant un vers capricieux,

Je serais là, pensif et la main sur les yeux,

Elle viendrait, sachant pourtant que c’est un crime,

Pour lire mon poème et me souffler ma rime,

Derrière moi, sans bruit, sur la pointe des pieds.

Moi, qui ne veux pas voir mes secrets épiés,

Je me retournerais avec un air farouche ;

Mais son gentil baiser me fermerait la bouche.

– Et dans les bois voisins, inondés de rayons,

Précédés du gros chien, nous nous promènerions,

Moi, vêtu de coutil, elle, en toilette blanche,

Et j’envelopperais sa taille, et sous sa manche

Ma main caresserait la rondeur de son bras.

On ferait des bouquets, et, quand nous serions las

On rejoindrait, toujours suivis du chien qui jappe,

La table mise, avec des roses sur la nappe,

Près du bosquet criblé par le soleil couchant ;

Et, tout en s’envoyant des baisers en mangeant,

Tout en s’interrompant pour se dire : Je t’aime !

On assaisonnerait des fraises à la crème,

Et l’on bavarderait comme des étourdis

Jusqu’à ce que la nuit descende…

François Coppée poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, CLASSIC POETRY

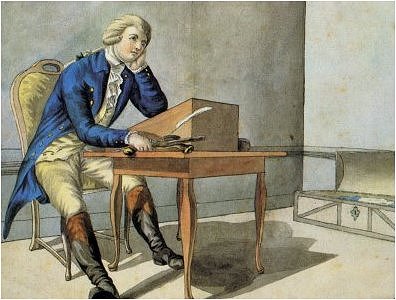

The Sorrows of Young Werther (11)

by J.W. von Goethe

16 June 1771

“Why do I not write to you?” You lay claim to learning, and ask such a question. You should have guessed that I am well–that is to say–in a word, I have made an acquaintance who has won my heart: I have–I know not.

To give you a regular account of the manner in which I have become acquainted with the most amiable of women would be a difficult task. I am a happy and contented mortal, but a poor historian.

An angel! Nonsense! Everybody so describes his mistress; and yet I find it impossible to tell you how perfect she is, or why she is so perfect: suffice it to say she has captivated all my senses.

So much simplicity with so much understanding–so mild, and yet so resolute–a mind so placid, and a life so active. But all this is ugly balderdash, which expresses not a single character nor feature. Some other time–but no, not some other time, now, this very instant, will I tell you all about it. Now or never. Well, between ourselves, since I commenced my letter, I have been three times on the point of throwing down my pen, of ordering my horse, and riding out.

And yet I vowed this morning that I would not ride to-day, and yet every moment I am rushing to the window to see how high the sun is.

I could not restrain myself–go to her I must. I have just returned, Wilhelm; and whilst I am taking supper I will write to you. What a delight it was for my soul to see her in the midst of her dear, beautiful children,–eight brothers and sisters!

But, if I proceed thus, you will be no wiser at the end of my letter than you were at the beginning. Attend, then, and I will compel myself to give you the details.

I mentioned to you the other day that I had become acquainted with S–, the district judge, and that he had invited me to go and visit him in his retirement, or rather in his little kingdom. But I neglected going, and perhaps should never have gone, if chance had not discovered to me the treasure which lay concealed in that retired spot. Some of our young people had proposed giving a ball in the country, at which I consented to be present. I offered my hand for the evening to a pretty and agreeable, but rather commonplace, sort of girl from the immediate neighbourhood; and it was agreed that I should engage a carriage, and call upon Charlotte, with my partner and her aunt, to convey them to the ball. My companion informed me, as we drove along through the park to the hunting-lodge, that I should make the acquaintance of a very charming young lady. “Take care,” added the aunt, “that you do not lose your heart.” “Why?” said I. “Because she is already engaged to a very worthy man,” she replied, “who is gone to settle his affairs upon the death of his father, and will succeed to a very considerable inheritance.” This information possessed no interest for me. When we arrived at the gate, the sun was setting behind the tops of the mountains. The atmosphere was heavy; and the ladies expressed their fears of an approaching storm, as masses of low black clouds were gathering in the horizon. I relieved their anxieties by pretending to be weather-wise, although I myself had some apprehensions lest our pleasure should be interrupted.

I alighted; and a maid came to the door, and requested us to wait a moment for her mistress. I walked across the court to a well-built house, and, ascending the flight of steps in front, opened the door, and saw before me the most charming spectacle I had ever witnessed. Six children, from eleven to two years old, were running about the hall, and surrounding a lady of middle height, with a lovely figure, dressed in a robe of simple white, trimmed with pink ribbons. She was holding a rye loaf in her hand, and was cutting slices for the little ones all around, in proportion to their age and appetite. She performed her task in a graceful and affectionate manner; each claimant awaiting his turn with outstretched hands, and boisterously shouting his thanks. Some of them ran away at once, to enjoy their evening meal; whilst others, of a gentler disposition, retired to the courtyard to see the strangers, and to survey the carriage in which their Charlotte was to drive away. “Pray forgive me for giving you the trouble to come for me, and for keeping the ladies waiting: but dressing, and arranging some household duties before I leave, had made me forget my children’s supper; and they do not like to take it from any one but me.” I uttered some indifferent compliment: but my whole soul was absorbed by her air, her voice, her manner; and I had scarcely recovered myself when she ran into her room to fetch her gloves and fan. The young ones threw inquiring glances at me from a distance; whilst I approached the youngest, a most delicious little creature. He drew back; and Charlotte, entering at the very moment, said, “Louis, shake hands with your cousin.” The little fellow obeyed willingly; and I could not resist giving him a hearty kiss, notwithstanding his rather dirty face. “Cousin,” said I to Charlotte, as I handed her down, “do you think I deserve the happiness of being related to you?” She replied, with a ready smile, “Oh! I have such a number of cousins, that I should be sorry if you were the most undeserving of them.” In taking leave, she desired her next sister, Sophy, a girl about eleven years old, to take great care of the children, and to say good-bye to papa for her when he came home from his ride. She enjoined to the little ones to obey their sister Sophy as they would herself, upon which some promised that they would; but a little fair-haired girl, about six years old, looked discontented, and said, “But Sophy is not you, Charlotte; and we like you best.” The two eldest boys had clambered up the carriage; and, at my request, she permitted them to accompany us a little way through the forest, upon their promising to sit very still, and hold fast.

We were hardly seated, and the ladies had scarcely exchanged compliments, making the usual remarks upon each other’s dress, and upon the company they expected to meet, when Charlotte stopped the carriage, and made her brothers get down. They insisted upon kissing her hands once more; which the eldest did with all the tenderness of a youth of fifteen, but the other in a lighter and more careless manner. She desired them again to give her love to the children, and we drove off.

The aunt inquired of Charlotte whether she had finished the book she had last sent her. “No,” said Charlotte; “I did not like it: you can have it again. And the one before was not much better.” I was surprised, upon asking the title, to hear that it was ****. (We feel obliged to suppress the passage in the letter, to prevent any one from feeling aggrieved; although no author need pay much attention to the opinion of a mere girl, or that of an unsteady young man.)

I found penetration and character in everything she said: every expression seemed to brighten her features with new charms,–with new rays of genius,–which unfolded by degrees, as she felt herself understood.

“When I was younger,” she observed, “I loved nothing so much as romances. Nothing could equal my delight when, on some holiday, I could settle down quietly in a corner, and enter with my whole heart and soul into the joys or sorrows of some fictitious Leonora. I do not deny that they even possess some charms for me yet. But I read so seldom, that I prefer books suited exactly to my taste. And I like those authors best whose scenes describe my own situation in life,–and the friends who are about me, whose stories touch me with interest, from resembling my own homely existence,–which, without being absolutely paradise, is, on the whole, a source of indescribable happiness.”

I endeavoured to conceal the emotion which these words occasioned, but it was of slight avail; for, when she had expressed so truly her opinion of “The Vicar of Wakefield,” and of other works, the names of which I omit (Though the names are omitted, yet the authors mentioned deserve Charlotte’s approbation, and will feel it in their hearts when they read this passage. It concerns no other person.), I could no longer contain myself, but gave full utterance to what I thought of it: and it was not until Charlotte had addressed herself to the two other ladies, that I remembered their presence, and observed them sitting mute with astonishment. The aunt looked at me several times with an air of raillery, which, however, I did not at all mind.

We talked of the pleasures of dancing. “If it is a fault to love it,” said Charlotte, “I am ready to confess that I prize it above all other amusements. If anything disturbs me, I go to the piano, play an air to which I have danced, and all goes right again directly.”

You, who know me, can fancy how steadfastly I gazed upon her rich dark eyes during these remarks, how my very soul gloated over her warm lips and fresh, glowing cheeks, how I became quite lost in the delightful meaning of her words, so much so, that I scarcely heard the actual expressions. In short, I alighted from the carriage like a person in a dream, and was so lost to the dim world around me, that I scarcely heard the music which resounded from the illuminated ballroom.

The two Messrs. Andran and a certain N. N. (I cannot trouble myself with the names), who were the aunt’s and Charlotte’s partners, received us at the carriage-door, and took possession of their ladies, whilst I followed with mine.

We commenced with a minuet. I led out one lady after another, and precisely those who were the most disagreeable could not bring themselves to leave off. Charlotte and her partner began an English country dance, and you must imagine my delight when it was their turnto dance the figure with us. You should see Charlotte dance. She dances with her whole heart and soul: her figure is all harmony, elegance, and grace, as if she were conscious of nothing else, and had no other thought or feeling; and, doubtless, for the moment, every other sensation is extinct.

She was engaged for the second country dance, but promised me the third, and assured me, with the most agreeable freedom, that she was very fond of waltzing. “It is the custom here,” she said, “for the previous partners to waltz together; but my partner is an indifferent waltzer,and will feel delighted if I save him the trouble. Your partner is not allowed to waltz, and, indeed, is equally incapable: but I observedduring the country dance that you waltz well; so, if you will waltz with me, I beg you would propose it to my partner, and I will propose it to yours.” We agreed, and it was arranged that our partners should mutually entertain each other.

We set off, and, at first, delighted ourselves with the usual graceful motions of the arms. With what grace, with what ease, she moved! Whenthe waltz commenced, and the dancers whirled around each other in the giddy maze, there was some confusion, owing to the incapacity of some of the dancers. We judiciously remained still, allowing the others to weary themselves; and, when the awkward dancers had withdrawn, we joined in, and kept it up famously together with one other couple,–Andran and his partner. Never did I dance more lightly. I felt myself more than mortal, holding this loveliest of creatures in my arms, flying, with her as rapidly as the wind, till I lost sight of every other object; and O Wilhelm, I vowed at that moment, that a maiden whom I loved, or for whom I felt the slightest attachment, never, never should waltz with any one else but with me, if I went to perdition for it!–you will understand this.

We took a few turns in the room to recover our breath. Charlotte sat down, and felt refreshed by partaking of some oranges which I had had secured,–the only ones that had been left; but at every slice which, from politeness, she offered to her neighbours, I felt as though a dagger went through my heart.

We were the second couple in the third country dance. As we were going down (and Heaven knows with what ecstasy I gazed at her arms and eyes, beaming with the sweetest feeling of pure and genuine enjoyment), we passed a lady whom I had noticed for her charming expression of countenance; although she was no longer young. She looked at Charlotte with a smile, then, holding up her finger in a threatening attitude, repeated twice in a very significant tone of voice the name of “Albert.”

“Who is Albert,” said I to Charlotte, “if it is not impertinent to ask?” She was about to answer, when we were obliged to separate, in order toexecute a figure in the dance; and, as we crossed over again in front of each other, I perceived she looked somewhat pensive. “Why need I conceal it from you?” she said, as she gave me her hand for the promenade.

“Albert is a worthy man, to whom I am engaged.” Now, there was nothing new to me in this (for the girls had told me of it on the way); but itwas so far new that I had not thought of it in connection with her whom, in so short a time, I had learned to prize so highly. Enough, I became confused, got out in the figure, and occasioned general confusion; so that it required all Charlotte’s presence of mind to set me right by pulling and pushing me into my proper place.

The dance was not yet finished when the lightning which had for some time been seen in the horizon, and which I had asserted to proceed entirely from heat, grew more violent; and the thunder was heard above the music. When any distress or terror surprises us in the midst of our amusements, it naturally makes a deeper impression than at other times, either because the contrast makes us more keenly susceptible, or rather perhaps because our senses are then more open to impressions, and the shock is consequently stronger. To this cause I must ascribe the fright and shrieks of the ladies. One sagaciously sat down in a corner with her back to the window, and held her fingers to her ears; a second knelt down before her, and hid her face in her lap; a third threw herself between them, and embraced her sister with a thousand tears; some insisted on going home; others, unconscious of their actions, wanted sufficient presence of mind to repress the impertinence of their young partners, who sought to direct to themselves those sighs which the lips of our agitated beauties intended for heaven. Some of the gentlemen had gone down-stairs to smoke a quiet cigar, and the rest of the company gladly embraced a happy suggestion of the hostess to retire into another room which was provided with shutters and curtains. We had hardly got there, when Charlotte placed the chairs in a circle; and, when the company had sat down in compliance with her request, she forthwith proposed a round game.

I noticed some of the company prepare their mouths and draw themselves up at the prospect of some agreeable forfeit. “Let us play at counting,” said Charlotte. “Now, pay attention: I shall go round the circle from right to left; and each person is to count, one after the other, the number that comes to him, and must count fast; whoever stops or mistakes is to have a box on the ear, and so on, till we have counted a thousand.” It was delightful to see the fun. She went round the circle with upraised arm. “One,” said the first; “two,” the second; “three,”the third; and so on, till Charlotte went faster and faster. One made a mistake, instantly a box on the ear; and, amid the laughter that ensued, came another box; and so on, faster and faster. I myself came in for two. I fancied they were harder than the rest, and felt quite delighted.

A general laughter and confusion put an end to the game long before we had counted as far as a thousand. The party broke up into little separate knots: the storm had ceased, and I followed Charlotte into the ballroom. On the way she said, “The game banished their fears of the storm.” I could make no reply. “I myself,” she continued, “was as much frightened as any of them; but by affecting courage, to keep up thespirits of the others, I forgot my apprehensions.” We went to the window. It was still thundering at a distance: a soft rain was pouring down over the country, and filled the air around us with delicious odours. Charlotte leaned forward on her arm; her eyes wandered over thescene; she raised them to the sky, and then turned them upon me; they were moistened with tears; she placed her hand on mine and said, “Klopstock!” at once I remembered the magnificent ode which was in her thoughts: I felt oppressed with the weight of my sensations, and sank under them. It was more than I could bear. I bent over her hand, kissed it in a stream of delicious tears, and again looked up to her eyes.

Divine Klopstock! why didst thou not see thy apotheosis in those eyes? And thy name so often profaned, would that I never heard it repeated!

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Jules Laforgue

(1860-1887)

Hypertrophie

Astres lointains des soirs, musiques infinies,

Ce Coeur universel ruisselant de douceur

Est le coeur de la Terre et de ses insomnies.

En un pantoum sans fin, magique et guérisseur

Bercez la Terre, votre soeur.

Le doux sang de l’Hostie a filtré dans mes moelles,

J’asperge les couchants de tragiques rougeurs,

Je palpite d’exil dans le coeur des étoiles,

Mon spleen fouette les grands nuages voyageurs.

Je beugle dans les vents rageurs.

Aimez-moi. Bercez-moi. Le cœur de l’oeuvre immense

Vers qui l’Océan noir pleurait, c’est moi qui l’ai.

Je suis le coeur de tout, et je saigne en démence

Et déborde d’amour par l’azur constellé,

Enfin ! que tout soit consolé.

Pauvre petit coeur sur la main,

La vie n’est pas folle pour nous

De sourires, ni de festins,

Ni de fêtes : et, de gros sous ?

Elle ne nous a pas gâtés

Et ne nous fait pas bon visage

Comme on fait à ces Enfants sages

Que nous sommes, en vérité.

Si sages nous ! Et, si peu fière

Notre façon d’être avec elle ;

Francs aussi, comme la lumière

Nous voudrions la trouver belle

Autant que d’Autres – pourtant quels ?

Et pieux, charger ses autels

Des plus belles fleurs du parterre

Et des meilleurs fruits de la terre.

Mais d’ailleurs, nous ne lui devrons

Que du respect, tout juste assez,

Qu’il faut professer envers ces

Empêcheurs de danser en rond.

Jules Laforgue poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive K-L, CLASSIC POETRY

Ada Christen

(1839-1901)

Nein!

Nein! … Nein!

Es ist

Kein Traum …

Was jetzt wie

Einer Braut

Dir bang den

Busen hebt,

Aus Deinem

Auge schaut,

Durch Deine

Glieder bebt!

Es ist

Kein Traum …

Nein! … Nein!

Ja? … Ja?!

Es ist

Das Glück!

Was Du mir

Anvertraut,

Erröthend,

Demuthsvoll,

Was ich nicht

Ueberlaut

In Lüfte

Jubeln soll …

Es ist

Das Glück!

Ja! … Ja!

Quelle: Ada Christen: Aus der Tiefe. Hamburg 1878.

Ada Christen poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Christen, Ada

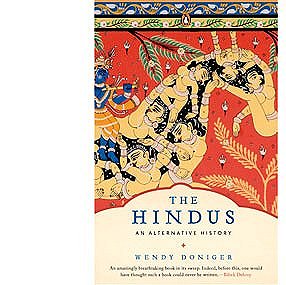

India: PEN protests withdrawal of best-selling book

In 2009, Penguin published The Hindus: An Alternative History by American Indologist Professor Wendy Doniger. The book became a number one bestseller in the non-fiction category in India and received positive reviews in the international media. It has also been subject to criticism, including an online petition highlighting supposed factual inaccuracies and calling for the immediate withdrawal of the book signed by more than 10,000 people.

In 2011, Dinanath Batra of Shiksha Bachao Andolan filed a case against the publisher, claiming that the book was offensive to Hindus and therefore in violation of Section 295A of the Indian penal code which prohibits ‘deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings or any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.’

According to the petitioners’ lawyer, on 10 February 2014 the publisher agreed to withdraw the book and to pulp recalled, withdrawn and unsold copies at their own cost.

The PEN All-India Centre in Mumbai and the PEN Delhi Centre have expressed their grave disappointment at the news, and published a statement from Professor Doniger: ‘I was, of course, angry and disappointed to see this happen, and I am deeply troubled by what it foretells for free speech in India in the present, and steadily worsening, political climate…. I do not blame Penguin Books, India. Other publishers have just quietly withdrawn other books without making the effort that Penguin made to save this book. Penguin, India, took this book on knowing that it would stir anger in the Hindutva ranks, and they defended it in the courts for four years, both as a civil and as a criminal suit.

They were finally defeated by the true villain of this piece – the Indian law that makes it a criminal rather than civil offense to publish a book that offends any Hindu, a law that jeopardizes the physical safety of any publisher, no matter how ludicrous the accusation brought against a book.’

On 14 February, Penguin India issued a statement on the case in which they echo Doniger’s concern about freedom of expression in the country: ‘The Indian Penal Code, and in particular section 295A of that code, will make it increasingly difficult for any Indian publisher to uphold international standards of free expression without deliberately placing itself outside the law. This is, we believe, an issue of great significance not just for the protection of creative freedoms in India but also for the defence of fundamental human rights.’

As former trustee and chair of English PEN’s Writers at Risk Committee: Salil Tripathi states in his piece on the controversy, Penguin’s disappointing surrender:

‘Those who disagreed with Doniger had options—to protest, to argue, to publish their own book as response, and if they had a copy, to shut it. Nobody is being forced to read it. Now, go to your electronic readers, buy it, download it, read it; if you go abroad, get copies—there’s no ban on its import; and reinforce the idea that a pluralistic India does not have singular views. India thrives in its diversity and plurality—its culture and its opinions.’

The Hindus: An Alternative History by Wendy Doniger is available from Foyles.

TAKE ACTION

Sign the petition: PEN Delhi is supporting this Change.org petition calling for the reform of Sections 153A and 295A of the Indian Penal Code. Sign the petition

Send a letter of appeal: Write to the Indian authorities protesting the withdrawal of Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus: An Alternative History and calling for the reform of Sections 153A and 295A. A sample letter is provided on the English PEN website but it is always better if you put the appeal in your own words.

Send a message of support: If you would like to send a message of support to Wendy Doniger, please email your message to cat@englishpen.org and they will pass it on.

# Read more on website English PEN

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (08)

`Laat dat godverdomme!’ brulde Kaspar tegen de muizen, wetend dat Bas van zijn boeken hield en al ongelukkig was als hij een ezelsoor aan een pagina ontdekte. `Boeken zijn er niet om te worden opgevreten. Boeken zijn er om te lezen!’

`Ze smaken anders best’, zei een van de papiervreters. `Ze drukken de boeken op goed papier. Lekker als toetje na een maaltijd kaas.’

`Als je het voortaan maar laat’, waarschuwde Kaspar, die nu het gevoel had dat hij weer iets ten opzichte van Bas aan het goedmaken was. `Bas heeft er al vaak over geklaagd dat al zijn boeken worden aangevreten. Straks is hij het moe en dan flikkert hij ons allemaal op straat.’

Kaspar wist best dat hij onzin sprak. Die goedaardige Bas zou het nooit over zijn hart kunnen verkrijgen hun ook maar één haar te krenken. Liever zou hij zelf zijn eten laten staan dan dat hij de muizen zag verkommeren.

Kaspar liep terug naar de bar, ontweek handig de benen van de klanten die aan de tafeltjes zaten, zette koers naar het raam en klom op het tafeltje voor het venster, waarop de fletsgroene critolis prijkte, de enige bloem die het café rijk was. Een vetplant die op niets anders leefde dan spuug, verschaald bier en sigarettenas.

Vanaf het tafeltje had Kaspar een goed uitzicht over een groot deel van de Kloveniersburgwal, al interesseerde hem dat nu niets, want hij was loom van het eten en in zijn kop spookte nog de ergernis over het gesprek met Bas.

Hij zag hoe Crazy Horse kwam aanhollen, midden op straat. Zo snel had hij nog nooit een mens zien lopen. Wat Crazy zich toch weer druk maakte, dacht Kaspar, terwijl hij wegdoezelde in een droomloze slaap, niet gestoord door de opgewonden kreten van de kaartende stamgasten en het ratelen van de flipperkast, dat zelfs de radio overstemde.

Ton van Reen: Katapult (08)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam, Reen, Ton van

Anatole France

(1844-1924)

La mort

Si la vierge vers toi jette sous les ramures

Le rire par sa mère à ses lèvres appris ;

Si, tiède dans son corps dont elle sait le prix,

Le désir a gonflé ses formes demi-mûres ;

Le soir, dans la forêt pleine de frais murmures,

Si, méditant d’unir vos chairs et vos esprits,

Vous mêlez, de sang jeune et de baisers fleuris,

Vos lèvres, en jouant, teintes du suc des mûres ;

Si le besoin d’aimer vous caresse et vous mord,

Amants, c’est que déjà plane sur vous la Mort :

Son aiguillon fait seul d’un couple un dieu qui crée.

Le sein d’un immortel ne saurait s’embraser.

Louez, vierges, amants, louez la Mort sacrée,

Puisque vous lui devez l’ivresse du baiser.

Anatole France poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, CLASSIC POETRY

The Sorrows of Young Werther (10)

by J.W. von Goethe

30 May 1771

What I have lately said of painting is equally true with respect to poetry. It is only necessary for us to know what is really excellent, and venture to give it expression; and that is saying much in few words.

To-day I have had a scene, which, if literally related, would, make the most beautiful idyl in the world. But why should I talk of poetry and scenes and idyls? Can we never take pleasure in nature without having recourse to art?

If you expect anything grand or magnificent from this introduction, you will be sadly mistaken. It relates merely to a peasant-lad, who has excited in me the warmest interest. As usual, I shall tell my story badly; and you, as usual, will think me extravagant. It is Walheim once more–always Walheim–which produces these wonderful phenomena.

A party had assembled outside the house under the linden-trees, to drink coffee. The company did not exactly please me; and, under one pretext or another, I lingered behind.

A peasant came from an adjoining house, and set to work arranging some part of the same plough which I had lately sketched. His appearance pleased me; and I spoke to him, inquired about his circumstances, made his acquaintance, and, as is my wont with persons of that class, was soon admitted into his confidence. He said he was in the service of a young widow, who set great store by him. He spoke so much of his mistress, and praised her so extravagantly, that I could soon see he was desperately in love with her. “She is no longer young,” he said: “and she was treated so badly by her former husband that she does not mean to marry again.” From his account it was so evident what incomparable charms she possessed for him, and how ardently he wished she would select him to extinguish the recollection of her first husband’s misconduct, that I should have to repeat his own words in order to describe the depth of the poor fellow’s attachment, truth, and devotion.

It would, in fact, require the gifts of a great poet to convey the expression of his features, the harmony of his voice, and the heavenly fire of his eye. No words can portray the tenderness of his every movement and of every feature: no effort of mine could do justice to the scene. His alarm lest I should misconceive his position with regard to his mistress, or question the propriety of her conduct, touched me particularly. The charming manner with which he described her form and person, which, without possessing the graces of youth, won and attached him to her, is inexpressible, and must be left to the imagination. I have never in my life witnessed or fancied or conceived the possibility of such intense devotion, such ardent affections, united with so much purity. Do not blame me if I say that the recollection of this innocence and truth is deeply impressed upon my very soul; that this picture of fidelity and tenderness haunts me everywhere; and that my own heart, as though enkindled by the flame, glows and burns within me.

I mean now to try and see her as soon as I can: or perhaps, on second thoughts, I had better not; it is better I should behold her through the eyes of her lover. To my sight, perhaps, she would not appear as she now stands before me; and why should I destroy so sweet a picture?

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

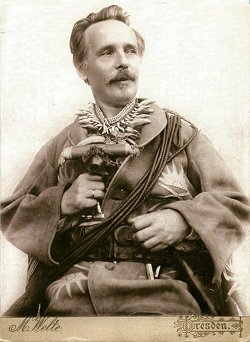

Karl May

(1842-1912)

Mein Liebchen

Wenn Sorge mich und Unmuth quälet,

Wenn mir’s an Moos im Beutel fehlet,

Wenn mich ein schwerer Kummer drückt,

Das Schicksal mich mit Pech beglückt:

Was ist es dann, wonach ich greife?

I nun! Die liebe Tabakspfeife!

Bei meinen Freuden, meinen Scherzen,

Beim Austausch gleichgesinnter Herzen,

In all’ den traulich frohen Stunden,

Die ich im Freundeskreis gefunden,

Bei meines Glück’s so seltner Reife

Ist stets um mich die liebe Pfeife.

Auf all’ den Reisen, die ich machte,

Wo die Natur mir freundlich lachte,

Auf all’ den einsam trauten Wegen,

Im Waldesgrün, wo ich gelegen,

In Feld und Flur, die ich durchstreife,

Begleitet mich die treue Pfeife.

Sie bleibt mir Braut durch’s ganze Leben;

Ja, sie in Adel zu erheben

Ist wohl ein Leichtes: Das Diplom

Schreibt sie sich selbst durch ihr Arom.

Sie heiße d’rum, ob man auch keife,

Von jetzt an: Edle von der Pfeife!

Karl May poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Karl May

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (07)

`Ik dacht dat de kleur van de vacht het enige verschil tussen de witte en de zwarte muizen was.’

`Nee hoor, de ene muis is de andere niet. Hoe is het mogelijk dat jij dat niet ziet. Ze zijn toch totaal anders, die witten. Ze klonteren altijd bij elkaar. Ze steken nooit een poot uit, ook al vreten ze meer dan wij. En manieren hebben ze niet. Swing it out, man! Swing it out! Wat ik zo walgelijk van hen vind is, dat ze stinken.’

`Ook dat nog’, riep Bas uit. `Waar heb ik dat meer gehoord!’

Hij was niet goed geworden van wat hij allemaal te horen had gekregen en bette zijn polsen en voorhoofd met een nat bierviltje.

`Trek het je niet zo aan’, zei Kaspar kalmerend. `Neem een lekker pilsje en laat het over je heen komen. Het is natuurlijk een teleurstelling, maar het was ook dom van je te verwachten dat muizen anders zouden zijn dan mensen. Je kunt ons niet kwalijk nemen dat we niet eens zoveel van jullie verschillen.’

`Ik voel me toch behoorlijk rottig.’ Bas tapte een pilsje uit het vat met Belgisch bier en dronk het glas in één teug leeg.

`Ik heb toch niks te veel gezegd’, zei Kaspar, geschrokken door de wezenloze blik in Bas’ ogen. `Zeg nou zelf, ik heb gelijk!’

`Het beste wat jíj kunt doen is een tijdje je bek houden’, zei Bas tegen de muis en hij staarde door het raam naar buiten.

Met de staart tussen de poten droop Kaspar af. Hij sprong van het buffet en bereikte via het deksel van de rommelbak de grond. Hij zocht naar dingen om zijn woede op af te reageren en zag dat een aantal muizen zich op de leesplanken achter in het café ophield. Hij besloot te controleren wat die daar uitvoerden en liep op een drafje naar de leeshoek. Jawel hoor, daar zag hij het al. Een paar onverlaten zaten aan de boeken te vreten die, tegen mogelijke ontvreemding, aan kettinkjes vastlagen. Uit de omslag van Mijn getijdenboek van Mulisch hadden ze de hele kop van Harry weggevreten, van oor tot oor. Ze waren druk bezig een mooi gat dwars door het boek te knagen. Eentje snoepte aan de nieuwste gedichten van Remco Campert. Een paar anderen vraten het gesponnen hoofdhaar van Mensje van Keulen uit de cover van een verjaarde Haagse Post.

Ton van Reen: Katapult (07)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam, Reen, Ton van

Théodore de BANVILLE

(1823-1891)

La Lune

Avec ses caprices, la Lune

Est comme une frivole amante ;

Elle sourit et se lamente,

Et vous fuit et vous importune.

La nuit, suivez-la sur la dune,

Elle vous raille et vous tourmente ;

Avec ses caprices, la Lune

Est comme une frivole amante.

Et souvent elle se met une

Nuée en manière de mante ;

Elle est absurde, elle est charmante ;

Il faut adorer sans rancune,

Avec ses caprices, la Lune

Théodore de Banville poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, CLASSIC POETRY

The Sorrows of Young Werther (09)

by J.W. von Goethe

27 May 1771

I find I have fallen into raptures, declamation, and similes, and have forgotten, in consequence, to tell you what became of the children.

Absorbed in my artistic contemplations, which I briefly described in my letter of yesterday, I continued sitting on the plough for two hours. Toward evening a young woman, with a basket on her arm, came running toward the children, who had not moved all that time. She exclaimed from a distance, “You are a good boy, Philip!” She gave me greeting: I returned it, rose, and approached her. I inquired if she were the mother of those pretty children. “Yes,” she said; and, giving the eldest a piece of bread, she took the little one in her arms and kissed it with a mother’s tenderness. “I left my child in Philip’s care,” she said, “whilst I went into the town with my eldest boy to buy some wheaten bread, some sugar, and an earthen pot.” I saw the various articles in the basket, from which the cover had fallen. “I shall make some broth to-night for my little Hans (which was the name of the youngest): that wild fellow, the big one, broke my pot yesterday, whilst he was scrambling with Philip for what remained of the contents.” I inquired for the eldest; and she had scarcely time to tell me that he was driving a couple of geese home from the meadow, when he ran up, and handed Philip an osier-twig. I talked a little longer with the woman, and found that she was the daughter of the schoolmaster, and that her husband was gone on a journey into Switzerland for some money a relation had left him. “They wanted to cheat him,” she said, “and would not answer his letters; so he is gone there himself. I hope he has met with no accident, as I have heard nothing of him since his departure.” I left the woman, with regret, giving each of the children a kreutzer, with an additional one for the youngest, to buy some wheaten bread for his broth when she went to town next; and so we parted. I assure you, my dear friend, when my thoughts are all in tumult, the sight of such a creature as this tranquillises my disturbed mind. She moves in a happy thoughtlessness within the confined circle of her existence; she supplies her wants from day to day; and, when she sees the leaves fall, they raise no other idea in her mind than that winter is approaching.

Since that time I have gone out there frequently. The children have become quite familiar with me; and each gets a lump of sugar when I drink my coffee, and they share my milk and bread and butter in the evening. They always receive their kreutzer on Sundays, for the good woman has orders to give it to them when I do not go there after evening service. They are quite at home with me, tell me everything; and I am particularly amused with observing their tempers, and the simplicity of their behaviour, when some of the other village children are assembled with them.

It has given me a deal of trouble to satisfy the anxiety of the mother, lest (as she says) “they should inconvenience the gentleman.”

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature