Fleurs du Mal Magazine

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

When Stretch’d on One’s Bed

When stretch’d on one’s bed

With a fierce-throbbing head,

Which preculdes alike thought or repose,

How little one cares

For the grandest affairs

That may busy the world as it goes!

How little one feels

For the waltzes and reels

Of our Dance-loving friends at a Ball!

How slight one’s concern

To conjecture or learn

What their flounces or hearts may befall.

How little one minds

If a company dines

On the best that the Season affords!

How short is one’s muse

O’er the Sauces and Stews,

Or the Guests, be they Beggars or Lords.

How little the Bells,

Ring they Peels, toll they Knells,

Can attract our attention or Ears!

The Bride may be married,

The Corse may be carried

And touch nor our hopes nor our fears.

Our own bodily pains

Ev’ry faculty chains;

We can feel on no subject besides.

Tis in health and in ease

We the power must seize

For our friends and our souls to provide.

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

Albrecht Rodenbach

(1856 – 1880)

Vaarwel

De wereld in, gij Liedjes en Gedichten

der eerste jeugd, en, vraagt men wie gij zijt

en wat gij, vreemdelingen, doen komt, antwoordt,

en zegt met vroeden zin, want u ook past

het peilend denken, kinders van gevoel

en scheppende begeestring: "Wij zijn stralen

uit Leven en Natuur geschongen, vonken

die onze dichter uit de keien sloeg

langs zijne bane; klanken afgeluisterd

uit die onduidelike harmonie

van hemel, veld en zee en zielenwereld.–

Wat ware zonder ‘t Licht het bont Heelal?

Wat zijn der velden vrolike geruchten

den wandelaar, indien hen zijne ziel

niet vatten en tot harmonieën kan smelten?

Wat is het Leven zonder Oorbeeld en

Poësis? O! eene onvolledigheid,

eene ijdelheid waarin de zielen kwijnen

verdord. En toch roept de ingeboren weêrklank

des Vloeks die eens het wroetelend Menschdom sloeg

en schreeuwt het zingend Oorbeeld tegen, en

vol onbewuste wanhoop pijnt hij om

het buiten ziel en leven te verbannen,

zijn eigen tot een straf; gelijk die boeters

in ‘t heimelik en somber Heidendom

die, dansend voor een goddelik wangedrocht,

in bloeddolheid hun eigen lijf verminken.

Wij komen, stemmen van het Oorbeeld, wij,

voor wie ons hooren wilt ons liedje zingen."

Zoo zult gij spreken, en vaarwel daarmede,

o Dichten jong en licht: ons roept de tijd

tot hooger peil en zwaarder bezigheid.

Albrecht Rodenbach gedicht

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R

.jpg)

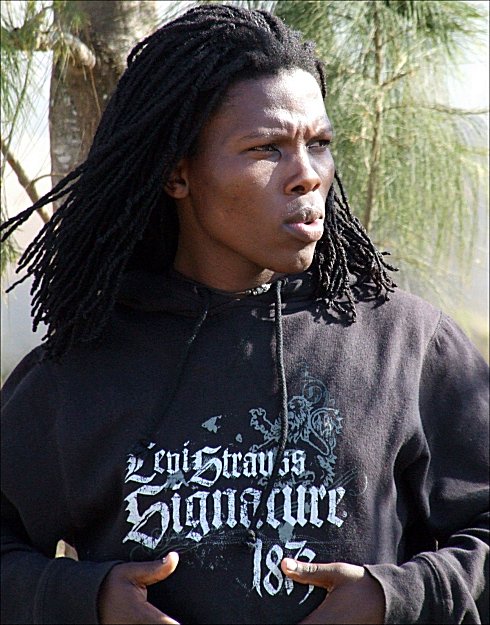

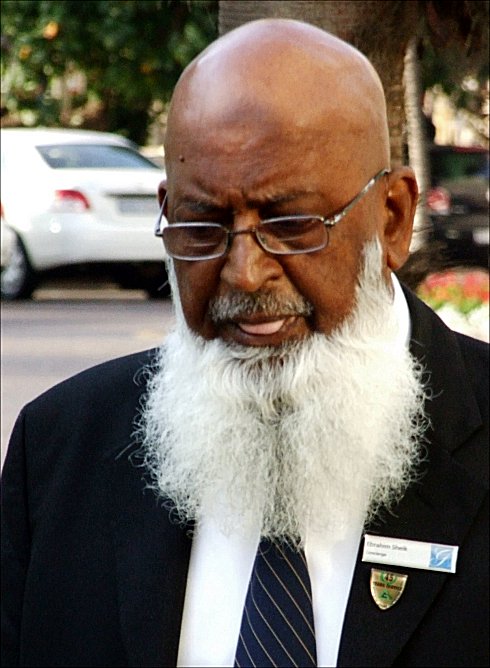

South African portraits (3)

Photos Co van Gorp

kempis poetry magazine ©

More in: Co van Gorp Photos, FDM in Africa

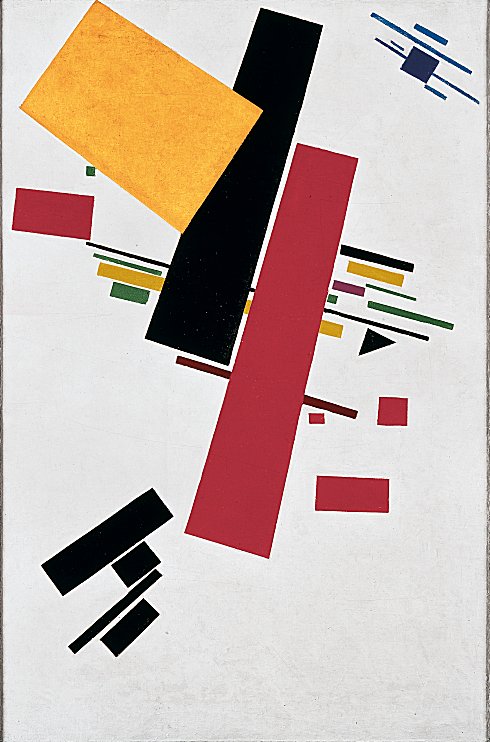

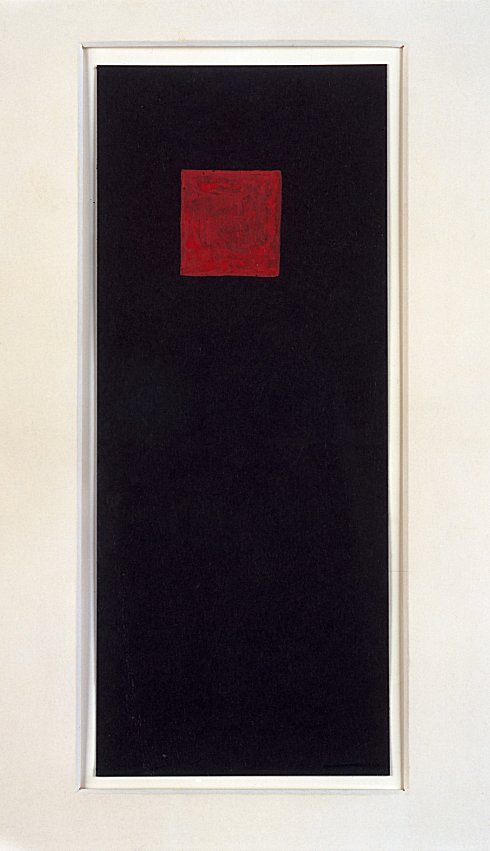

Museum Ludwig Köln

Kazimir Malevitsch and Suprematism

in the Ludwig Collection

5 February – 22 August 2010

After the exhibition “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste. Cubo-Futurism and the Rise of Modernism in Russia” Museum Ludwig contin-ues its project series on the Russian avant-garde with a cabinet exhibition of its Malevich collection. This is one of the largest collections worldwide of Malevich’s work and will be shown for the first time in nearly twenty years. The approximately fifty graphic works, four paintings and one sculpture from all periods of his work afford viewers an insight into the artist’s development from figurative art to abstraction and back again to figuration. As part of the exhibition preparations, our restorers subjected the four paintings to an art-technological examination. Ten suprematist works by artists from Malevitsch’s circle, Ekaterina Bugrova, Ivan Kliun, Nina Kogan, Liubov Popova, Kliment Redko, Nikolai Suetin and Ilya Chashnik, will complement the exhibition and demonstrate Malevich’s influence on his contemporaries.

The concept of Suprematism denotes both abstract composition using pure shapes as well as Malevich’s own theory of pure abstraction in art; for him, this implies “everything that goes beyond what has to this date been created in art”.

The focal point will be the presentation of the two paintings from his Suprematist period, “Supremus No. 38” from 1916 and “Suprematist Composition” from 1915. The latter underwent substantial restoration for the exhibition and both paintings were subjected to an art-technological examination. The findings will be comprehensively documented as part of the exhibition.

On the basis of the results of the examinations carried out (UV, infrared, X-ray) and based upon the history of the paintings (exhibitions; change of owner; earlier restoration measures), the state of preservation of the paintings as they are today, and also how they were created, will be rendered visible. From detailed close-ups, the viewers will learn how to spot certain traits of painting technique like, for example, surface structures and brush strokes – but also the impact restoration can have on the appearance of the paintings. In preparation the exhibition, also numerous works on paper by Malevich were restored.

Like the paintings in the collection, the drawings by Malevich too stem from various periods of his work, from his beginnings around 1903 to his famous invention and development of (abstract) Suprematism all the way to his return to figuration. This change of course in his later work has only recently become the subject of art historical research. The extensive Ludwig Collection is ideally suited to the exploration of abstraction as well as figuration. The public will be able to trace and comprehend the development of Malevich’s work. The confrontation of his early concrete works with his later ones makes a unique comparison possible.

A catalogue which documents the complete findings of the art technological examinations and features further scholarly essays on Malevich will be published in April 2010 with the support of the Friends of the Wallraf Richartz Museum and the Museum Ludwig e.V.

With over 800 works, the Museum Ludwig is home to one of the world’s largest collections of the Russian avant-garde. In May 2009, a se-ries of exhibitions started which highlights new aspects of the col-lection and its main emphases. The series goes hand in hand with in-tensive research into the techniques used in the works, the picture frames and the dates. Curator of the series is Katia Baudin, the deputy director of Museum Ludwig, with Emily Joyce Evans acting as assistant curator. Petra Mandt worked on the art technological examinations and their documentation.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Constructivism

.jpg)

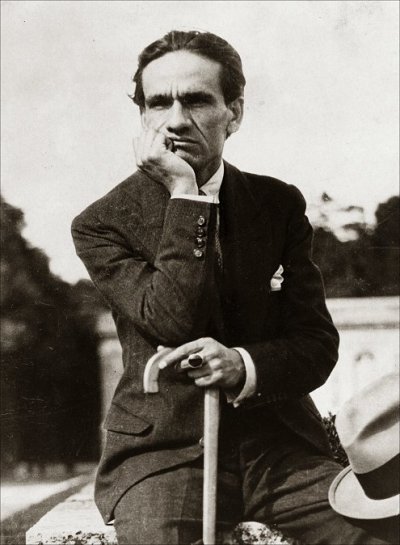

E u g e n e M a r a i s

(1871-1936)

D i e O o r w i n n a a r s

By die kindergrafte uit die Konsentrasiekamp van Nylstroom

Oorwinnaars vir ons volk,

bly u vir al wat beste in ons is ‘n ewig’ tolk;

nooit weer sal vyandsvoet u stof so diep vertrap en smoor

dat ons u langer nie kan sien – en hoor.

Nie onse Helde, wat die magtig’ leër

op glansryk’ velde kon weerstaan en keer;

nie onse Seuns, wat aan die galg en teen die muur

die diepe liefde vir hul eie moes verduur;

nie onse Moeders, wat met bloeiend hart en seer,

in swart Getsemane die ware smart moes leer;

nie onse Generaals, vereer met krans en riddersnoer;

– was waardig vir ons volk die hoë stryd te voer

en te oorwin.

Nie ons, met vuile hand en hart ontrou was waardig

om die vaandel hoog te hou.

Maar u, o bleke spokies, in U kermend’, klagend’ wee,

staan voor ons ewiglik beskermend – uit die lang verlee.

E u g e n e M a r a i s p o e t r y

fleursdumal.nl m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive M-N, Eugène Marais, Marais, Eugène

.jpg)

.jpg)

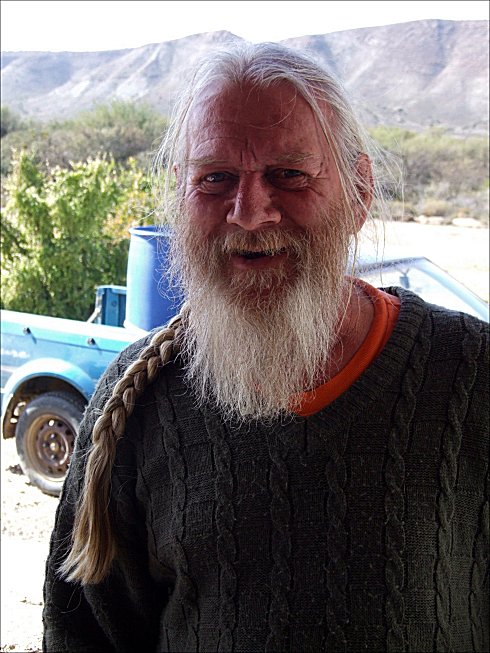

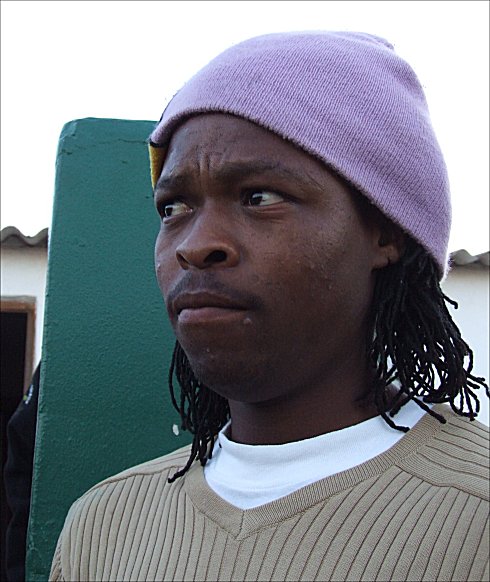

South African portraits (2)

Photos Co van Gorp

kempis poetry magazine ©

More in: Co van Gorp Photos, FDM in Africa

![]()

Museum Ludwig Köln

Roy Lichtenstein. Kunst als Motiv

2. Juli – 3. Oktober 2010

Die Rasterpunkte des Pop Art Meisters Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997) sind weltberühmt. Nach Motiven aus der Comic- und Konsumwelt fertigte Lichtenstein Gemälde, die er aus Punkten und Farbflächen zusammensetzte. In der Ausstellung im Museum Ludwig sind nun noch ganz andere Seiten seines Oeuvres zu entdecken. In rund 100 Exponaten, überwiegend großformatigen Gemälde, sowie einigen Skulpturen und Zeichnungen wird seine Auseinandersetzung mit kunsthistorischen Stilrichtungen von Expressionismus und Futurismus bis Bauhaus und Artdeco nachvollziehbar. Außerdem hat sich Lichtenstein Werke von Künstlerheroen wie Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian oder Dali angeeignet und sie oft ironisch, hintergründig in seiner eigenen Bildsprache interpretiert.

Viele seiner Frühwerke basieren auf historischen amerikanischen Gemälden, z.B. von Benjamin West. Außerdem malte er nach Vorbildern von Picasso, Braque und Klee, die er nach eigener Aussage in einem „expressionistischen Kubismus“ verarbeitet

Mit Picasso setzt er sich auch später weiter auseinander, als er bereits mit Rasterpunkten arbeitet. Unter seiner Hand wird Picasso zum Pseudo-Comic und erhält einen völlig eigenen Charakter. “Ein Werk zu malen, das eindeutig einem Picasso ähnelt, war ein Befreiungsschlag“

Mit seinen Perfect und Imperfect Paintings wollte Lichtenstein abstrakte, völlig zweckfreie Bilder schaffen. „Die Idee war, die Linie irgendwo beginnen zu lassen, um ihr dann zu folgen und alle Formen des Gemäldes zeichnen zu lassen“. Bei den „Perfect Paintings“ endet die Linie am Rand der Leinwand, bei den “Imperfect Paintings“ geht die Linie über den Bildträger hinaus; dies ist ein humorvolles Spiel mit den „shaped canvases“, die in den 60er Jahren sehr verbreitet waren.

Lichtensteins großformatige Gemälde aus der Serie der „Brushstrokes“ zeigen nichts als gigantische, comicartig stilisierte Pinselstriche auf Leinwand. Dieses Motiv hat eine große Bedeutung in der Kunstgeschichte: es steht als Symbol für die Malerei oder die Kunst. Es zeugt von Lichtensteins Reflexion einer Malerei über Malerei.

Er verarbeitet auch klassische Motive, wie den Laokoon mit stilisierten Pinselstrichen, die er teils mit Schablonen auf die Leinwand bringt und teils mit expressiver Geste von Hand aufträgt. Der Pinselstrich wird zum dominanten Motiv und überlagert das Sujet. So ist auch hier das eigentliche Thema wieder die Malerei an sich.

Außerdem beschäftigt sich Lichtenstein mit den klassischen Genres des Stilllebens und der Landschaft. Seine stark vereinfachende Malweise zeigt die klischeehafte Vorstellung seiner Sujets. Auch hier bezieht er sich wieder auf Picasso, aber auch auf Matisse. Außerdem zitiert er amerikanische Maler, die sich auf Marinestillleben spezialisiert haben. Für seine Landschaften dienten ihm die Hintergrundzeichnungen von Comics als Vorlage.

Das Museum Ludwig besitzt die größte Sammlung amerikanischer Pop Art außerhalb der USA, darunter auch zahlreiche Werke Lichtensteins. Im Vorfeld der Ausstellung konnte durch die Peter und Irene Ludwig Stiftung ein neues, großformatiges Spätwerk Lichtensteins erworben werden. Das 2,80 x 1,30 m große Gemälde von 1996 stammt aus einer Serie von asiatisch inspirierten Werken. Roy Lichtenstein setzte sich Mitte der 90er Jahre intensiv mit chinesischer und japanischer Landschaftsmalerei auseinander.

Im Anschluss an den Besuch der Lichtenstein-Ausstellung empfiehlt sich ein Rundgang durch die ständige Sammlung des Museum Ludwig, der spannende Einblicke und Vergleiche ermöglicht mit Werken von Léger und Picasso bis hin zu Kirchner oder Dalí.

Die Ausstellung wurde in enger Zusammenarbeit mit der Roy Lichtenstein Foundation organisiert. Von Januar bis Mai war sie in anderer Form in Mailand in der „Triennale di Milano“ unter dem Titel „Roy Lichtenstein: Meditations on Art“ zu sehen. Sie wurde von Gianni Mercurio kuratiert, für das Museum Ludwig gemeinsam mit Stephan Diederich.

In der Ausstellung wird ein Dokumentarfilm über Roy Lichtenstein gezeigt, der bisher unveröffentlichtes Material aus internationalen Archiven beinhaltet, sowie Ausschnitte aus Michael Blackwoods Film „Roy Lichtenstein“ von 1976 und Auszüge aus Interviews mit Diane Waldman und Martin Friedman.

Es erscheint ein umfangreiches, begleitendes Katalogbuch mit zahlreichen Abbildungen im DuMont Verlag.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive

![]()

Jose Marti

(1853-1895)

Pour Out Your Sorrows

My Heart (Verse XLVI)

Pour out your sorrows, my heart,

But let none discover where;

For my pride makes me forbear

My heart’s sorrows to impart.

I love you, Verse, my friend true,

Because when in pieces torn

My heart’s too burdened, you’ve borne

All my sorrows upon you.

For me you suffer and bear

Upon your amorous lap

Every anguish, every slap

That my painful love leaves there.

That I may love, in peace with all,

And do good works, as my goal,

You thrash your waves, rise and fall,

With whatever weighs my soul.

That I may cross with fierce stride,

Pure and without hate, this vale,

You drag yourself, hard and pale,

The loving friend at my side.

And so my life its way will wend

To the sky serene and pure,

While you my sorrows endure

And with divine patience tend.

Because I know this cruel habit

Of throwing myself on you

Upsets your harmony true

And tries your gentle spirit;

Because on your breast I’ve shed

All of my sorrows and torments,

And have whipped your quiet currents,

Which are here white and there red,

And then pale as death become,

At once roaring and attacking,

And then beneath the weight cracking

Of pain it can’t overcome: —

Should I the advice have taken

Of a heart so misbegotten,

Would have me leave you forgotten

Who never me has forsaken?

Verse, there’s a God, they aver

To whom the dying appealed;

Verse, as one our fates our sealed:

We are damned or saved together!

Vierte Corazón tu pena

(Verso XLVI)

Vierte, corazón, tu pena

Donde no se llegue a ver,

Por soberbia, y por no ser

Motivo de pena ajena.

Yo te quiero, verso amigo,

Porque cuando siento el pecho

Ya muy cargado y deshecho,

Parto la carga contigo.

Tú me sufres, tú aposentas

En tu regazo amoroso,

Todo mi amor doloroso,

Todas mis ansias y afrentas.

Tú, porque yo pueda en calma

Amar y hacer bien, consientes

En enturbiar tus corrientes

Con cuanto me agobia el alma.

Tú, porque yo cruce fiero

La tierra, y sin odio, y puro,

Te arrastras, pálido y duro,

Mi amoroso compañero.

Mi vida así se encamina

Al cielo limpia y serena,

Y tú me cargas mi pena

Con tu paciencia divina.

Y porque mi cruel costumbre

De echarme en ti te desvía

De su dichosa armonía

Y natural mansedumbre;

Porque mis penas arrojo

Sobre tu seno, y lo azotan,

Y tu corriente alborotan,

Y acá lívido, allá rojo,

Blanco allá como la muerte,

Ora arremetes y ruges,

Ora con el peso crujes

De un dolor más que tú fuerte,

¿Habré, como me aconseja

Un corazón mal nacido,

De dejar en el olvido

A aquel que nunca me deja?

¡Verso, nos hablan de un Dios

Adonde van los difuntos:

Verso, o nos condenan juntos,

O nos salvamos los dos!

Jose Marti poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

.jpg)

E m i l y D i c k i n s o n

(1830-1886)

T h e M o u n t a i n

The mountain sat upon the plain

In his eternal chair,

His observation omnifold,

His inquest everywhere.

The seasons prayed around his knees,

Like children round a sire:

Grandfather of the days is he,

Of dawn the ancestor.

.jpg)

Emily Dickinson poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Dickinson, Emily

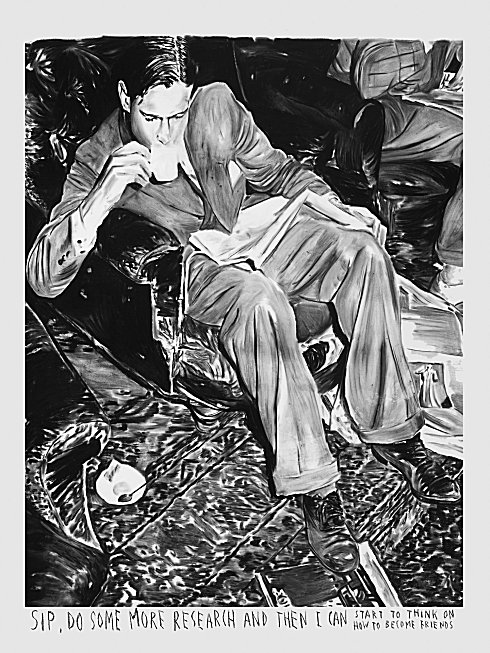

Watou 2010 – Tussen Taal en Beeld

Verzamelde Verhalen #2

03/07/10 – 05/09/10

Kunstenfestival Watou 2010 opent vandaag !!

Kunstenfestival Watou 2010 – Tussen Taal en Beeld/ Verzamelde Verhalen #02 opent vandaag zijn deuren. De laatste details worden in orde gebracht. Tientallen kunstenaars en dichters uit alle hoeken van de wereld zakten de voorbije weken af naar Watou om er hun werk te installeren. Sommigen kunstenaars verbleven dagen lang op locatie om hun werk optimaal in te passen in de ruimte. Veel kunstwerken kwamen terplekke tot stand. Leegstaande verlaten panden of aftandse gebouwen werden onherkenbaar getransformeerd tot verrassende werelden met onvermoede verhalen die vanaf nu volop door u kunnen worden ontdekt.

Openingweekend 3 & 4 juli

Kunstenfestival Watou 2010 opent feestelijk met interventies van het Theater van de Verloren Tijd (doorlopend van 14 tot 18 u. op diverse locaties), een performance/muziekconcert van TITHONUS met curator Jan Van Woensel (doorlopend van 14 tot 18 u. in het Parochiehuisje (naast de Parochiezaal in Watou) en de publieksperformance LICHTKARAVAAN op de site van het Blauwhuys. Op zaterdagavond omstreeks 21.30 u is iedereen (uit Watou en omgeving) er welkom. Van zodra dat het donker wordt, zullen er duizend lampions in de lucht gelaten worden. Alle inwoners uit Watou (en in het bijzonder de kinderen) kregen de kans om vooraf de lampionnen te versieren met tekeningen en gedichten. Voor meer info over het openingweekend en over alle activiteiten tijdens de Weekendhappenings bekijk de website http://www.watou2010.be/ bij weekendhappenings.

Kunstenfestival Watou 2010

toont werk van meer dan honderd beeldende kunstenaars, schrijvers en dichters: David Adamo (US) – Nel Aerts (BE) -Armando (NL)- Ingeborg Bachman (AT) – Charles Baudelaire (FR) – Peter Beyls (BE) – Thomas Bogaert (BE) – Inge Braeckman (BE) – Tsead Bruinja (NL) – Koen Broucke (BE) – Cees Buddingh’ (NL) – Buson (JP) – Céline Butaye (BE) – Sander Buyck (BE) – Remco Campert (NL) – Sofie Cerutti (NL) – Michiel Ceulers (BE) – Hou Chien Cheng (TW) – Hugo Claus (BE) – Paul Cox (BE) – Jozef L. de Belder (BE) – Marc De Blieck (BE) – Manon De Boer (NL) – Kristof De Borle (BE) – Jules Deelder (NL) – Jos de Haes (BE) – Wim Delvoye (BE) – Roger M.J. de Neef (BE) – Jasper De Pagie (BE) – Josse De Pauw (BE) – Bieke Depoorter (BE) – Johan De Wilde (BE) – Christine D’Haen (BE) – Honoré d’O (BE) en nog vele andere. Bekijk de volledige lijst op de website www.watou2010.be

Grensland

Naast de vele locaties met beeldende kunst, literatuur en poëzie, ontpopt de locatie grensland zich dit jaar tot een literair cluster van kamers met grensoverschrijdende presentaties waarin taal het uitgangspunt vormt. Naast de Zaplocatie met voorleessessies en performances van verschillende dichters en de filmruimte met een beklijvende documentaire over Rutger Kopland, is er ook een Literaire Slowfoodruimte (een boekengrot) met een selectie literaire fragmenten van Friedl’ Lesage en van Josse De Pauw.

Een ander bijzondere nieuwe ruimte in Grensland is: ‘Het Klein Museum van De Kunstenaar.’ Kunstenaar Koen Broucke creëerde niet zonder humor, zijn bijzondere intieme kamer: een klein museum ter ere van zichzelf.

Verder ontpopt Grensland zich tot dé broeiende happening plek van het festival. De meeste activiteiten van de weekendhappenings vinden er plaats: performances, muziek- en theatervoorstellingen.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Historia Belgica, MUSIC, THEATRE, Watou Kunstenfestival

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

“I Am Christina Rossetti”

On the fifth of this December [1930] Christina Rossetti will celebrate her centenary, or, more properly speaking, we shall celebrate it for her, and perhaps not a little to her distress, for she was one of the shyest of women, and to be spoken of, as we shall certainly speak of her, would have caused her acute discomfort. Nevertheless, it is inevitable; centenaries are inexorable; talk of her we must. We shall read her life; we shall read her letters; we shall study her portraits, speculate about her diseases — of which she had a great variety; and rattle the drawers of her writing-table, which are for the most part empty. Let us begin with the biography — for what could be more amusing? As everybody knows, the fascination of reading biographies is irresistible. No sooner have we opened the pages of Miss Sandars’s careful and competent book (Life of Christina Rossetti, by Mary F. Sandars. (Hutchinson)) than the old illusion comes over us. Here is the past and all its inhabitants miraculously sealed as in a magic tank; all we have to do is to look and to listen and to listen and to look and soon the little figures — for they are rather under life size — will begin to move and to speak, and as they move we shall arrange them in all sorts of patterns of which they were ignorant, for they thought when they were alive that they could go where they liked; and as they speak we shall read into their sayings all kinds of meanings which never struck them, for they believed when they were alive that they said straight off whatever came into their heads. But once you are in a biography all is different.

Here, then, is Hallam Street, Portland Place, about the year 1830; and here are the Rossettis, an Italian family consisting of father and mother and four small children. The street was unfashionable and the home rather poverty-stricken; but the poverty did not matter, for, being foreigners, the Rossettis did not care much about the customs and conventions of the usual middle-class British family. They kept themselves to themselves, dressed as they liked, entertained Italian exiles, among them organ-grinders and other distressed compatriots, and made ends meet by teaching and writing and other odd jobs. By degrees Christina detached herself from the family group. It is plain that she was a quiet and observant child, with her own way of life already fixed in her head — she was to write — but all the more did she admire the superior competence of her elders. Soon we begin to surround her with a few friends and to endow her with a few characteristics. She detested parties. She dressed anyhow. She liked her brother’s friends and little gatherings of young artists and poets who were to reform the world, rather to her amusement, for although so sedate, she was also whimsical and freakish, and liked making fun of people who took themselves with egotistic solemnity. And though she meant to be a poet she had very little of the vanity and stress of young poets; her verses seem to have formed themselves whole and entire in her head, and she did not worry very much what was said of them because in her own mind she knew that they were good. She had also immense powers of admiration — for her mother, for example, who was so quiet, and so sagacious, so simple and so sincere; and for her elder sister Maria, who had no taste for painting or for poetry, but was, for that very reason, perhaps more vigorous and effective in daily life. For example, Maria always refused to visit the Mummy Room at the British Museum because, she said, the Day of Resurrection might suddenly dawn and it would be very unseemly if the corpses had to put on immortality under the gaze of mere sight-seers — a reflection which had not struck Christina, but seemed to her admirable. Here, of course, we, who are outside the tank, enjoy a hearty laugh, but Christina, who is inside the tank and exposed to all its heats and currents, thought her sister’s conduct worthy of the highest respect. Indeed, if we look at her a little more closely we shall see that something dark and hard, like a kernel, had already formed in the centre of Christina Rossetti’s being.

It was religion, of course. Even when she was quite a girl her lifelong absorption in the relation of the soul with God had taken possession of her. Her sixty-four years might seem outwardly spent in Hallam Street and Endsleigh Gardens and Torrington Square, but in reality she dwelt in some curious region where the spirit strives towards an unseen God — in her case, a dark God, a harsh God — a God who decreed that all the pleasures of the world were hateful to Him. The theatre was hateful, the opera was hateful, nakedness was hateful — when her friend Miss Thompson painted naked figures in her pictures she had to tell Christina that they were fairies, but Christina saw through the imposture — everything in Christina’s life radiated from that knot of agony and intensity in the centre. Her belief regulated her life in the smallest particulars. It taught her that chess was wrong, but that whist and cribbage did not matter. But also it interfered in the most tremendous questions of her heart. There was a young painter called James Collinson, and she loved James Collinson and he loved her, but he was a Roman Catholic and so she refused him. Obligingly he became a member of the Church of England, and she accepted him. Vacillating, however, for he was a slippery man, he wobbled back to Rome, and Christina, though it broke her heart and for ever shadowed her life, cancelled the engagement. Years afterwards another, and it seems better founded, prospect of happiness presented itself. Charles Cayley proposed to her. But alas, this abstract and erudite man who shuffled about the world in a state of absent-minded dishabille, and translated the gospel into Iroquois, and asked smart ladies at a party “whether they were interested in the Gulf Stream”, and for a present gave Christina a sea mouse preserved in spirits, was, not unnaturally, a free thinker. Him, too, Christina put from her. Though “no woman ever loved a man more deeply”, she would not be the wife of a sceptic. She who loved the “obtuse and furry”— the wombats, toads, and mice of the earth — and called Charles Cayley “my blindest buzzard, my special mole”, admitted no moles, wombats, buzzards, or Cayleys to her heaven.

So one might go on looking and listening for ever. There is no limit to the strangeness, amusement, and oddity of the past sealed in a tank. But just as we are wondering which cranny of this extraordinary territory to explore next, the principal figure intervenes. It is as if a fish, whose unconscious gyrations we had been watching in and out of reeds, round and round rocks, suddenly dashed at the glass and broke it. A tea-party is the occasion. For some reason Christina went to a party given by Mrs. Virtue Tebbs. What happened there is unknown — perhaps something was said in a casual, frivolous, tea-party way about poetry. At any rate,

suddenly there uprose from a chair and paced forward into the centre of the room a little woman dressed in black, who announced solemnly, “I am Christina Rossetti!” and having so said, returned to her chair.

With those words the glass is broken. Yes [she seems to say], I am a poet. You who pretend to honour my centenary are no better than the idle people at Mrs. Tebb’s tea-party. Here you are rambling among unimportant trifles, rattling my writing-table drawers, making fun of the Mummies and Maria and my love affairs when all I care for you to know is here. Behold this green volume. It is a copy of my collected works. It costs four shillings and sixpence. Read that. And so she returns to her chair.

How absolute and unaccommodating these poets are! Poetry, they say, has nothing to do with life. Mummies and wombats, Hallam Street and omnibuses, James Collinson and Charles Cayley, sea mice and Mrs. Virtue Tebbs, Torrington Square and Endsleigh Gardens, even the vagaries of religious belief, are irrelevant, extraneous, superfluous, unreal. It is poetry that matters. The only question of any interest is whether that poetry is good or bad. But this question of poetry, one might point out if only to gain time, is one of the greatest difficulty. Very little of value has been said about poetry since the world began. The judgment of contemporaries is almost always wrong. For example, most of the poems which figure in Christina Rossetti’s complete works were rejected by editors. Her annual income from her poetry was for many years about ten pounds. On the other hand, the works of Jean Ingelow, as she noted sardonically, went into eight editions. There were, of course, among her contemporaries one or two poets and one or two critics whose judgment must be respectfully consulted. But what very different impressions they seem to gather from the same works — by what different standards they judge! For instance, when Swinburne read her poetry he exclaimed: “I have always thought that nothing more glorious in poetry has ever been written”, and went on to say of her New Year Hymn that it was

touched as with the fire and bathed as in the light of sunbeams, tuned as to chords and cadences of refluent sea-music beyond reach of harp and organ, large echoes of the serene and sonorous tides of heaven

Then Professor Saintsbury comes with his vast learning, and examines Goblin Market, and reports that

The metre of the principal poem [“Goblin Market”] may be best described as a dedoggerelised Skeltonic, with the gathered music of the various metrical progress since Spenser, utilised in the place of the wooden rattling of the followers of Chaucer. There may be discerned in it the same inclination towards line irregularity which has broken out, at different times, in the Pindaric of the late seventeenth and earlier eighteenth centuries, and in the rhymelessness of Sayers earlier and of Mr. Arnold later.

And then there is Sir Walter Raleigh:

I think she is the best poet alive. . . . The worst of it is you cannot lecture on really pure poetry any more than you can talk about the ingredients of pure water — it is adulterated, methylated, sanded poetry that makes the best lectures. The only thing that Christina makes me want to do, is cry, not lecture.

It would appear, then, that there are at least three schools of criticism: the refluent sea-music school; the line-irregularity school, and the school that bids one not criticise but cry. This is confusing; if we follow them all we shall only come to grief. Better perhaps read for oneself, expose the mind bare to the poem, and transcribe in all its haste and imperfection whatever may be the result of the impact. In this case it might run something as follows: O Christina Rossetti, I have humbly to confess that though I know many of your poems by heart, I have not read your works from cover to cover. I have not followed your course and traced your development. I doubt indeed that you developed very much. You were an instinctive poet. You saw the world from the same angle always. Years and the traffic of the mind with men and books did not affect you in the least. You carefully ignored any book that could shake your faith or any human being who could trouble your instincts. You were wise perhaps. Your instinct was so sure, so direct, so intense that it produced poems that sing like music in one’s ears — like a melody by Mozart or an air by Gluck. Yet for all its symmetry, yours was a complex song. When you struck your harp many strings sounded together. Like all instinctives you had a keen sense of the visual beauty of the world. Your poems are full of gold dust and “sweet geraniums’ varied brightness”; your eye noted incessantly how rushes are “velvet-headed”, and lizards have a “strange metallic mail”— your eye, indeed, observed with a sensual pre-Raphaelite intensity that must have surprised Christina the Anglo-Catholic. But to her you owed perhaps the fixity and sadness of your muse. The pressure of a tremendous faith circles and clamps together these little songs. Perhaps they owe to it their solidity. Certainly they owe to it their sadness — your God was a harsh God, your heavenly crown was set with thorns. No sooner have you feasted on beauty with your eyes than your mind tells you that beauty is vain and beauty passes. Death, oblivion, and rest lap round your songs with their dark wave. And then, incongruously, a sound of scurrying and laughter is heard. There is the patter of animals’ feet and the odd guttural notes of rooks and the snufflings of obtuse furry animals grunting and nosing. For you were not a pure saint by any means. You pulled legs; you tweaked noses. You were at war with all humbug and pretence. Modest as you were, still you were drastic, sure of your gift, convinced of your vision. A firm hand pruned your lines; a sharp ear tested their music. Nothing soft, otiose, irrelevant cumbered your pages. In a word, you were an artist. And thus was kept open, even when you wrote idly, tinkling bells for your own diversion, a pathway for the descent of that fiery visitant who came now and then and fused your lines into that indissoluble connection which no hand can put asunder:

But bring me poppies brimmed with sleepy death

And ivy choking what it garlandeth

And primroses that open to the moon.

Indeed so strange is the constitution of things, and so great the miracle of poetry, that some of the poems you wrote in your little back room will be found adhering in perfect symmetry when the Albert Memorial is dust and tinsel. Our remote posterity will be singing:

When I am dead, my dearest,

or:

My heart is like a singing bird,

when Torrington Square is a reef of coral perhaps and the fishes shoot in and out where your bedroom window used to be; or perhaps the forest will have reclaimed those pavements and the wombat and the ratel will be shuffling on soft, uncertain feet among the green undergrowth that will then tangle the area railings. In view of all this, and to return to your biography, had I been present when Mrs. Virtue Tebbs gave her party, and had a short elderly woman in black risen to her feet and advanced to the middle of the room, I should certainly have committed some indiscretion — have broken a paper-knife or smashed a tea-cup in the awkward ardour of my admiration when she said, “I am Christina Rossetti”.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader, Second Series

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Rossetti, Christina, Woolf, Virginia

Cesar Vallejo

(1892 – 1938)

Los heraldos negros

Hay golpes en la vida tan fuertes . . . ¡Yo no se!

Golpes como del odio de Dios; como si ante ellos;

la resaca de todo lo sufrido se empozara en el alma

¡Yo no se!

Son pocos; pero son . . . abren zanjas oscuras

en el rostro mas fiero y en el lomo mas fuerte,

Serán talvez los potros de bárbaros atilas;

o los heraldos negros que nos manda la Muerte

Son las caídas hondas de los Cristos del alma,

de alguna adorable que el Destino Blasfema,

Esos golpes sangrientos son las crepitaciones

de algún pan que en la puerta del horno se nos quema

Y el hombre….pobre…¡pobre!

Vuelve los ojos,

como cuando por sobre el hombro

nos llama una palmada;

vuelve los ojos locos,

y todo lo vivido

se empoza, como charco de culpa,

en la mirada.

Hay golpes en la vida, tan fuertes . . . ¡Yo no se!

Cesar Vallejo poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Vallejo, Cesar

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature