Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

40

Take all my loves, my love, yea take them all,

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call,

All mine was thine, before thou hadst this more:

Then if for my love, thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee, for my love thou usest,

But yet be blamed, if thou thy self deceivest

By wilful taste of what thy self refusest.

I do forgive thy robbery gentle thief

Although thou steal thee all my poverty:

And yet love knows it is a greater grief

To bear love’s wrong, than hate’s known injury.

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites yet we must not be foes.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Anton K. photos: Nature Morte (8)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, Dutch Landscapes

.jpg)

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

Lightly Come or Lightly Go

Lightly come or lightly go:

Though thy heart presage thee woe,

Vales and many a wasted sun,

Oread let thy laughter run,

Till the irreverent mountain air

Ripple all thy flying hair.

Lightly, lightly — – ever so:

Clouds that wrap the vales below

At the hour of evenstar

Lowliest attendants are;

Love and laughter song-confessed

When the heart is heaviest.

Silently She’s Combing

Silently she’s combing,

Combing her long hair

Silently and graciously,

With many a pretty air.

The sun is in the willow leaves

And on the dappled grass,

And still she’s combing her long hair

Before the looking-glass.

I pray you, cease to comb out,

Comb out your long hair,

For I have heard of witchery

Under a pretty air,

That makes as one thing to the lover

Staying and going hence,

All fair, with many a pretty air

And many a negligence.

.jpg)

James Joyce poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Joyce, James

.jpg)

Aloysius Bertrand

(1807-1841)

L E M A Ç O N

(Gaspard de la Nuit)

"Le maître Maçon. – Regardez ces bastions, ces contreforts: on les dirait construits pour l’éternité."

SCHILLER. – Guillaume-Tell.

Le maçon Abraham Knupfer chante, la truelle ŕ la main, dans les airs échafaudé, si haut que, lisant les vers gothiques du bourdon, il nivelle de ses pieds et l’église aux trente arc-boutants, et la ville aux trente églises.

Il voit les tarasques de pierre vomir l’eau des ardoises dans l’abîme confus des galeries, des fenętres, des pendentifs, des clochetons, des tourelles, des toits et des charpentes, que tache d’un point gris l’aile échancrée et immobile du tiercelet.

Il voit les fortifications qui se découpent en étoile, la citadelle qui se rengorge comme une géline dans un tourteau, les cours des palais oů le soleil tarit les fontaines, et les cloîtres des monastčres oů l’ombre tourne autour des piliers.

Les troupes impériales se sont logées dans le faubourg. Voilŕ qu’un cavalier tambourine lŕ-bas. Abraham Knupfer distingue son chapeau ŕ trois cornes, ses aiguilles de laine rouge, sa cocarde traversée d’une ganse, et sa queue nouée d’un ruban.

Ce qu’il voit encore, ce sont des soudards qui, dans le parc empanaché de gigantesques ramées, sur de larges pelouses d’émeraude, criblent de coups d’arquebuse un oiseau de bois fiché ŕ la pointe d’un mai.

Et le soir, quand la nef harmonique de la cathédrale s’endormit couchée les bras en croix, il aperçut de l’échelle, ŕ l’horizon, un village incendié par des gens de guerre, qui flamboyait comme une comčte dans l’azur.

.jpg)

Aloysius Bertrand poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Bertrand, Aloysius

.jpg)

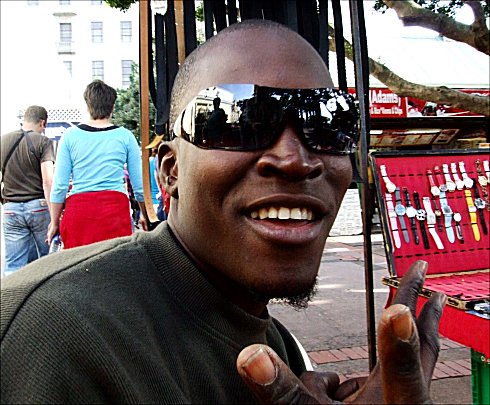

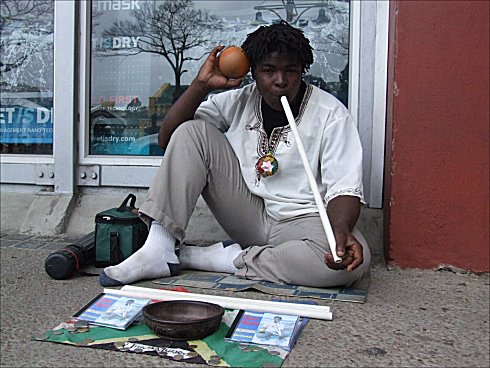

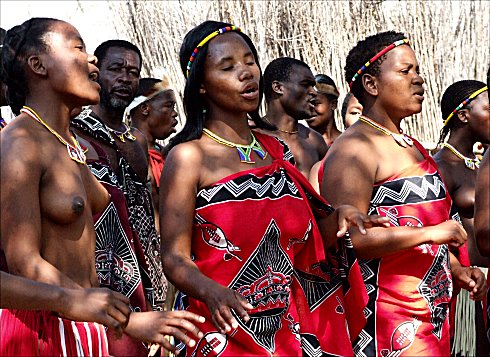

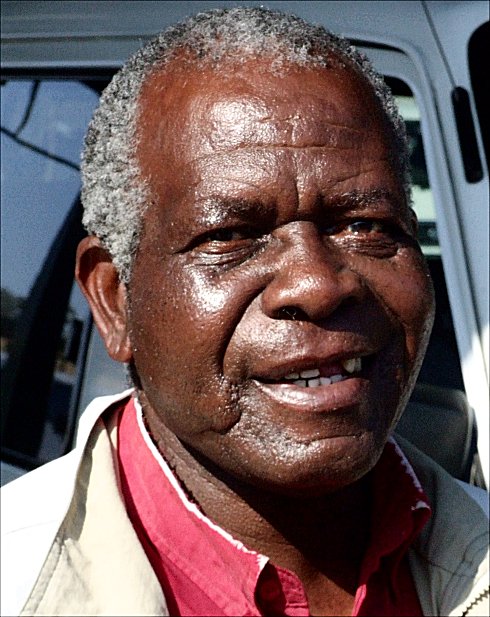

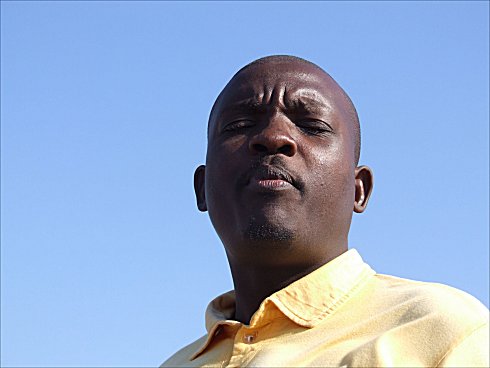

South African portraits (4)

Photos Co van Gorp

kempis poetry magazine ©

More in: Co van Gorp Photos, FDM in Africa

![]()

William Makepeace Thackeray

(1811-1863)

The End Of The Play

The play is done; the curtain drops,

Slow falling to the prompter’s bell:

A moment yet the actor stops,

And looks around, to say farewell.

It is an irksome word and task;

And, when he’s laughed and said his say,

He shows, as he removes the mask,

A face that’s anything but gay.

One word, ere yet the evening ends,

Let’s close it with a parting rhyme,

And pledge a hand to all young friends,

As fits the merry Christmas time.

On life’s wide scene you, too, have parts,

That Fate ere long shall bid you play;

Good night! with honest gentle hearts

A kindly greeting go alway!

Goodnight—I’d say, the griefs, the joys,

Just hinted in this mimic page,

The triumphs and defeats of boys,

Are but repeated in our age.

I’d say, your woes were not less keen,

Your hopes more vain than those of men;

Your pangs or pleasures of fifteen

At forty-five played o’er again.

I’d say, we suffer and we strive,

Not less nor more as men, than boys;

With grizzled beards at forty-five,

As erst at twelve in corduroys.

And if, in time of sacred youth,

We learned at home to love and pray,

Pray Heaven that early Love and Truth

May never wholly pass away.

And in the world, as in the school,

I’d say, how fate may change and shift;

The prize be sometimes with the fool,

The race not always to the swift.

The strong may yield, the good may fall,

The great man be a vulgar clown,

The knave be lifted over all,

The kind cast pitilessly down.

Who knows the inscrutable design?

Blessed be He who took and gave!

Why should your mother, Charles, not mine,

Be weeping at her darling’s grave?

We bow to Heaven that will’d it so,

That darkly rules the fate of all,

That sends the respite or the blow,

That’s free to give, or to recall.

This crowns his feast with wine and wit:

Who brought him to that mirth and state?

His betters, see, below him sit,

Or hunger hopeless at the gate.

Who bade the mud from Dives’ wheel

To spurn the rags of Lazarus?

Come, brother, in that dust we’ll kneel,

Confessing Heaven that ruled it thus.

So each shall mourn, in life’s advance,

Dear hopes, dear friends, untimely killed;

Shall grieve for many a forfeit chance,

And longing passion unfulfilled.

Amen! whatever fate be sent,

Pray God the heart may kindly glow,

Although the head with cares be bent,

And whitened with the winter snow.

Come wealth or want, come good or ill,

Let young and old accept their part,

And bow before the Awful Will,

And bear it with an honest heart,

Who misses or who wins the prize.

Go, lose or conquer as you can;

But if you fail, or if you rise,

Be each, pray God, a gentleman.

A gentleman, or old or young!

(Bear kindly with my humble lays);

The sacred chorus first was sung

Upon the first of Christmas days:

The shepherds heard it overhead—

The joyful angels raised it then:

Glory to Heaven on high, it said,

And peace on earth to gentle men.

My song, save this, is little worth;

I lay the weary pen aside,

And wish you health, and love, and mirth,

As fits the solemn Christmas-tide.

As fits the holy Christmas birth,

Be this, good friends, our carol still—

Be peace on earth, be peace on earth,

To men of gentle will.

William Makepeace Thackeray poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Jane Austen

It is probable that if Miss Cassandra Austen had had her way we should have had nothing of Jane Austen’s except her novels. To her elder sister alone did she write freely; to her alone she confided her hopes and, if rumour is true, the one great disappointment of her life; but when Miss Cassandra Austen grew old, and the growth of her sister’s fame made her suspect that a time might come when strangers would pry and scholars speculate, she burnt, at great cost to herself, every letter that could gratify their curiosity, and spared only what she judged too trivial to be of interest.

Hence our knowledge of Jane Austen is derived from a little gossip, a few letters, and her books. As for the gossip, gossip which has survived its day is never despicable; with a little rearrangement it suits our purpose admirably. For example, Jane “is not at all pretty and very prim, unlike a girl of twelve . . . Jane is whimsical and affected,” says little Philadelphia Austen of her cousin. Then we have Mrs. Mitford, who knew the Austens as girls and thought Jane “the prettiest, silliest, most affected husband-hunting butterfly she ever remembers “. Next, there is Miss Mitford’s anonymous friend “who visits her now [and] says that she has stiffened into the most perpendicular, precise, taciturn piece of ‘single blessedness’ that ever existed, and that, until Pride and Prejudice showed what a precious gem was hidden in that unbending case, she was no more regarded in society than a poker or firescreen. . . . The case is very different now”, the good lady goes on; “she is still a poker — but a poker of whom everybody is afraid. . . . A wit, a delineator of character, who does not talk is terrific indeed!” On the other side, of course, there are the Austens, a race little given to panegyric of themselves, but nevertheless, they say, her brothers “were very fond and very proud of her. They were attached to her by her talents, her virtues, and her engaging manners, and each loved afterwards to fancy a resemblance in some niece or daughter of his own to the dear sister Jane, whose perfect equal they yet never expected to see.” Charming but perpendicular, loved at home but feared by strangers, biting of tongue but tender of heart — these contrasts are by no means incompatible, and when we turn to the novels we shall find ourselves stumbling there too over the same complexities in the writer.

To begin with, that prim little girl whom Philadelphia found so unlike a child of twelve, whimsical and affected, was soon to be the authoress of an astonishing and unchildish story, Love and Freindship,8 which, incredible though it appears, was written at the age of fifteen. It was written, apparently, to amuse the schoolroom; one of the stories in the same book is dedicated with mock solemnity to her brother; another is neatly illustrated with water-colour heads by her sister. These are jokes which, one feels, were family property; thrusts of satire, which went home because all little Austens made mock in common of fine ladies who “sighed and fainted on the sofa”.

Brothers and sisters must have laughed when Jane read out loud her last hit at the vices which they all abhorred. “I die a martyr to my grief for the loss of Augustus. One fatal swoon has cost me my life. Beware of Swoons, Dear Laura. . . . Run mad as often as you chuse, but do not faint. . . .” And on she rushed, as fast as she could write and quicker than she could spell, to tell the incredible adventures of Laura and Sophia, of Philander and Gustavus, of the gentleman who drove a coach between Edinburgh and Stirling every other day, of the theft of the fortune that was kept in the table drawer, of the starving mothers and the sons who acted Macbeth. Undoubtedly, the story must have roused the schoolroom to uproarious laughter. And yet, nothing is more obvious than that this girl of fifteen, sitting in her private corner of the common parlour, was writing not to draw a laugh from brother and sisters, and not for home consumption. She was writing for everybody, for nobody, for our age, for her own; in other words, even at that early age Jane Austen was writing. One hears it in the rhythm and shapeliness and severity of the sentences. “She was nothing more than a mere good-tempered, civil, and obliging young woman; as such we could scarcely dislike her — she was only an object of contempt.” Such a sentence is meant to outlast the Christmas holidays. Spirited, easy, full of fun, verging with freedom upon sheer nonsense,— Love and Freindship is all that; but what is this note which never merges in the rest, which sounds distinctly and penetratingly all through the volume? It is the sound of laughter. The girl of fifteen is laughing, in her corner, at the world.

Girls of fifteen are always laughing. They laugh when Mr. Binney helps himself to salt instead of sugar. They almost die of laughing when old Mrs. Tomkins sits down upon the cat. But they are crying the moment after. They have no fixed abode from which they see that there is something eternally laughable in human nature, some quality in men and women that for ever excites our satire. They do not know that Lady Greville who snubs, and poor Maria who is snubbed, are permanent features of every ballroom. But Jane Austen knew it from her birth upwards. One of those fairies who perch upon cradles must have taken her a flight through the world directly she was born. When she was laid in the cradle again she knew not only what the world looked like, but had already chosen her kingdom. She had agreed that if she might rule over that territory, she would covet no other. Thus at fifteen she had few illusions about other people and none about herself. Whatever she writes is finished and turned and set in its relation, not to the parsonage, but to the universe. She is impersonal; she is inscrutable. When the writer, Jane Austen, wrote down in the most remarkable sketch in the book a little of Lady Greville’s conversation, there is no trace of anger at the snub which the clergyman’s daughter, Jane Austen, once received. Her gaze passes straight to the mark, and we know precisely where, upon the map of human nature, that mark is. We know because Jane Austen kept to her compact; she never trespassed beyond her boundaries. Never, even at the emotional age of fifteen, did she round upon herself in shame, obliterate a sarcasm in a spasm of compassion, or blur an outline in a mist of rhapsody. Spasms and rhapsodies, she seems to have said, pointing with her stick, end THERE; and the boundary line is perfectly distinct. But she does not deny that moons and mountains and castles exist — on the other side. She has even one romance of her own. It is for the Queen of Scots. She really admired her very much. “One of the first characters in the world”, she called her, “a bewitching Princess whose only friend was then the Duke of Norfolk, and whose only ones now Mr. Whitaker, Mrs. Lefroy, Mrs. Knight and myself.” With these words her passion is neatly circumscribed, and rounded with a laugh. It is amusing to remember in what terms the young Brontë‘s wrote, not very much later, in their northern parsonage, about the Duke of Wellington.

The prim little girl grew up. She became “the prettiest, silliest, most affected husband-hunting butterfly” Mrs. Mitford ever remembered, and, incidentally, the authoress of a novel called Pride and Prejudice, which, written stealthily under cover of a creaking door, lay for many years unpublished. A little later, it is thought, she began another story, The Watsons, and being for some reason dissatisfied with it, left it unfinished. The second-rate works of a great writer are worth reading because they offer the best criticism of his masterpieces. Here her difficulties are more apparent, and the method she took to overcome them less artfully concealed. To begin with, the stiffness and the bareness of the first chapters prove that she was one of those writers who lay their facts out rather baldly in the first version and then go back and back and back and cover them with flesh and atmosphere. How it would have been done we cannot say — by what suppressions and insertions and artful devices. But the miracle would have been accomplished; the dull history of fourteen years of family life would have been converted into another of those exquisite and apparently effortless introductions; and we should never have guessed what pages of preliminary drudgery Jane Austen forced her pen to go through. Here we perceive that she was no conjuror after all. Like other writers, she had to create the atmosphere in which her own peculiar genius could bear fruit. Here she fumbles; here she keeps us waiting. Suddenly she has done it; now things can happen as she likes things to happen. The Edwardses are going to the ball. The Tomlinsons’ carriage is passing; she can tell us that Charles is “being provided with his gloves and told to keep them on”; Tom Musgrave retreats to a remote corner with a barrel of oysters and is famously snug. Her genius is freed and active. At once our senses quicken; we are possessed with the peculiar intensity which she alone can impart. But of what is it all composed? Of a ball in a country town; a few couples meeting and taking hands in an assembly room; a little eating and drinking; and for catastrophe, a boy being snubbed by one young lady and kindly treated by another. There is no tragedy and no heroism. Yet for some reason the little scene is moving out of all proportion to its surface solemnity. We have been made to see that if Emma acted so in the ball-room, how considerate, how tender, inspired by what sincerity of feeling she would have shown herself in those graver crises of life which, as we watch her, come inevitably before our eyes. Jane Austen is thus a mistress of much deeper emotion than appears upon the surface. She stimulates us to supply what is not there. What she offers is, apparently, a trifle, yet is composed of something that expands in the reader’s mind and endows with the most enduring form of life scenes which are outwardly trivial. Always the stress is laid upon character. How, we are made to wonder, will Emma behave when Lord Osborne and Tom Musgrave make their call at five minutes before three, just as Mary is bringing in the tray and the knife-case? It is an extremely awkward situation. The young men are accustomed to much greater refinement. Emma may prove herself ill-bred, vulgar, a nonentity. The turns and twists of the dialogue keep us on the tenterhooks of suspense. Our attention is half upon the present moment, half upon the future. And when, in the end, Emma behaves in such a way as to vindicate our highest hopes of her, we are moved as if we had been made witnesses of a matter of the highest importance. Here, indeed, in this unfinished and in the main inferior story, are all the elements of Jane Austen’s greatness. It has the permanent quality of literature. Think away the surface animation, the likeness to life, and there remains, to provide a deeper pleasure, an exquisite discrimination of human values. Dismiss this too from the mind and one can dwell with extreme satisfaction upon the more abstract art which, in the ball-room scene, so varies the emotions and proportions the parts that it is possible to enjoy it, as one enjoys poetry, for itself, and not as a link which carries the story this way and that.

But the gossip says of Jane Austen that she was perpendicular, precise, and taciturn —“a poker of whom everybody is afraid”. Of this too there are traces; she could be merciless enough; she is one of the most consistent satirists in the whole of literature. Those first angular chapters of The Watsons prove that hers was not a prolific genius; she had not, like Emily Brontë, merely to open the door to make herself felt. Humbly and gaily she collected the twigs and straws out of which the nest was to be made and placed them neatly together. The twigs and straws were a little dry and a little dusty in themselves. There was the big house and the little house; a tea party, a dinner party, and an occasional picnic; life was hedged in by valuable connections and adequate incomes; by muddy roads, wet feet, and a tendency on the part of the ladies to get tired; a little principle supported it, a little consequence, and the education commonly enjoyed by upper middle-class families living in the country. Vice, adventure, passion were left outside. But of all this prosiness, of all this littleness, she evades nothing, and nothing is slurred over. Patiently and precisely she tells us how they “made no stop anywhere till they reached Newbury, where a comfortable meal, uniting dinner and supper, wound up the enjoyments and fatigues of the day”. Nor does she pay to conventions merely the tribute of lip homage; she believes in them besides accepting them. When she is describing a clergyman, like Edmund Bertram, or a sailor, in particular, she appears debarred by the sanctity of his office from the free use of her chief tool, the comic genius, and is apt therefore to lapse into decorous panegyric or matter-of-fact description. But these are exceptions; for the most part her attitude recalls the anonymous lady’s ejaculation —“A wit, a delineator of character, who does not talk is terrific indeed!” She wishes neither to reform nor to annihilate; she is silent; and that is terrific indeed. One after another she creates her fools, her prigs, her worldlings, her Mr. Collinses, her Sir Walter Elliotts, her Mrs. Bennets. She encircles them with the lash of a whip-like phrase which, as it runs round them, cuts out their silhouettes for ever. But there they remain; no excuse is found for them and no mercy shown them. Nothing remains of Julia and Maria Bertram when she has done with them; Lady Bertram is left “sitting and calling to Pug and trying to keep him from the flower-beds” eternally. A divine justice is meted out; Dr. Grant, who begins by liking his goose tender, ends by bringing on “apoplexy and death, by three great institutionary dinners in one week”. Sometimes it seems as if her creatures were born merely to give Jane Austen the supreme delight of slicing their heads off. She is satisfied; she is content; she would not alter a hair on anybody’s head, or move one brick or one blade of grass in a world which provides her with such exquisite delight.

Nor, indeed, would we. For even if the pangs of outraged vanity, or the heat of moral wrath, urged us to improve away a world so full of spite, pettiness, and folly, the task is beyond our powers. People are like that — the girl of fifteen knew it; the mature woman proves it. At this very moment some Lady Bertram is trying to keep Pug from the flower beds; she sends Chapman to help Miss Fanny a little late. The discrimination is so perfect, the satire so just, that, consistent though it is, it almost escapes our notice. No touch of pettiness, no hint of spite, rouse us from our contemplation. Delight strangely mingles with our amusement. Beauty illumines these fools.

That elusive quality is, indeed, often made up of very different parts, which it needs a peculiar genius to bring together. The wit of Jane Austen has for partner the perfection of her taste. Her fool is a fool, her snob is a snob, because he departs from the model of sanity and sense which she has in mind, and conveys to us unmistakably even while she makes us laugh. Never did any novelist make more use of an impeccable sense of human values. It is against the disc of an unerring heart, an unfailing good taste, an almost stern morality, that she shows up those deviations from kindness, truth, and sincerity which are among the most delightful things in English literature. She depicts a Mary Crawford in her mixture of good and bad entirely by this means. She lets her rattle on against the clergy, or in favour of a baronetage and ten thousand a year, with all the ease and spirit possible; but now and again she strikes one note of her own, very quietly, but in perfect tune, and at once all Mary Crawford’s chatter, though it continues to amuse, rings flat. Hence the depth, the beauty, the complexity of her scenes. From such contrasts there comes a beauty, a solemnity even, which are not only as remarkable as her wit, but an inseparable part of it. In The Watsons she gives us a foretaste of this power; she makes us wonder why an ordinary act of kindness, as she describes it, becomes so full of meaning. In her masterpieces, the same gift is brought to perfection. Here is nothing out of the way; it is midday in Northamptonshire; a dull young man is talking to rather a weakly young woman on the stairs as they go up to dress for dinner, with housemaids passing. But, from triviality, from commonplace, their words become suddenly full of meaning, and the moment for both one of the most memorable in their lives. It fills itself; it shines; it glows; it hangs before us, deep, trembling, serene for a second; next, the housemaid passes, and this drop, in which all the happiness of life has collected, gently subsides again to become part of the ebb and flow of ordinary existence.

What more natural, then, with this insight into their profundity, than that Jane Austen should have chosen to write of the trivialities of day-to-day existence, of parties, picnics, and country dances? No “suggestions to alter her style of writing” from the Prince Regent or Mr. Clarke could tempt her; no romance, no adventure, no politics or intrigue could hold a candle to life on a country-house staircase as she saw it. Indeed, the Prince Regent and his librarian had run their heads against a very formidable obstacle; they were trying to tamper with an incorruptible conscience, to disturb an infallible discretion. The child who formed her sentences so finely when she was fifteen never ceased to form them, and never wrote for the Prince Regent or his Librarian, but for the world at large. She knew exactly what her powers were, and what material they were fitted to deal with as material should be dealt with by a writer whose standard of finality was high. There were impressions that lay outside her province; emotions that by no stretch or artifice could be properly coated and covered by her own resources. For example, she could not make a girl talk enthusiastically of banners and chapels. She could not throw herself whole-heartedly into a romantic moment. She had all sorts of devices for evading scenes of passion. Nature and its beauties she approached in a sidelong way of her own. She describes a beautiful night without once mentioning the moon. Nevertheless, as we read the few formal phrases about “the brilliancy of an unclouded night and the contrast of the deep shade of the woods”, the night is at once as “solemn, and soothing, and lovely” as she tells us, quite simply, that it was.

The balance of her gifts was singularly perfect. Among her finished novels there are no failures, and among her many chapters few that sink markedly below the level of the others. But, after all, she died at the age of forty-two. She died at the height of her powers. She was still subject to those changes which often make the final period of a writer’s career the most interesting of all. Vivacious, irrepressible, gifted with an invention of great vitality, there can be no doubt that she would have written more, had she lived, and it is tempting to consider whether she would not have written differently. The boundaries were marked; moons, mountains, and castles lay on the other side. But was she not sometimes tempted to trespass for a minute? Was she not beginning, in her own gay and brilliant manner, to contemplate a little voyage of discovery?

Let us take Persuasion, the last completed novel, and look by its light at the books she might have written had she lived. There is a peculiar beauty and a peculiar dullness in Persuasion. The dullness is that which so often marks the transition stage between two different periods. The writer is a little bored. She has grown too familiar with the ways of her world; she no longer notes them freshly. There is an asperity in her comedy which suggests that she has almost ceased to be amused by the vanities of a Sir Walter or the snobbery of a Miss Elliott. The satire is harsh, and the comedy crude. She is no longer so freshly aware of the amusements of daily life. Her mind is not altogether on her object. But, while we feel that Jane Austen has done this before, and done it better, we also feel that she is trying to do something which she has never yet attempted. There is a new element in Persuasion, the quality, perhaps, that made Dr. Whewell fire up and insist that it was “the most beautiful of her works”. She is beginning to discover that the world is larger, more mysterious, and more romantic than she had supposed. We feel it to be true of herself when she says of Anne: “She had been forced into prudence in her youth, she learned romance as she grew older — the natural sequel of an unnatural beginning”. She dwells frequently upon the beauty and the melancholy of nature, upon the autumn where she had been wont to dwell upon the spring. She talks of the “influence so sweet and so sad of autumnal months in the country”. She marks “the tawny leaves and withered hedges”. “One does not love a place the less because one has suffered in it”, she observes. But it is not only in a new sensibility to nature that we detect the change. Her attitude to life itself is altered. She is seeing it, for the greater part of the book, through the eyes of a woman who, unhappy herself, has a special sympathy for the happiness and unhappiness of others, which, until the very end, she is forced to comment upon in silence. Therefore the observation is less of facts and more of feelings than is usual. There is an expressed emotion in the scene at the concert and in the famous talk about woman’s constancy which proves not merely the biographical fact that Jane Austen had loved, but the aesthetic fact that she was no longer afraid to say so. Experience, when it was of a serious kind, had to sink very deep, and to be thoroughly disinfected by the passage of time, before she allowed herself to deal with it in fiction. But now, in 1817, she was ready. Outwardly, too, in her circumstances, a change was imminent. Her fame had grown very slowly. “I doubt”, wrote Mr. Austen Leigh, “whether it would be possible to mention any other author of note whose personal obscurity was so complete.” Had she lived a few more years only, all that would have been altered. She would have stayed in London, dined out, lunched out, met famous people, made new friends, read, travelled, and carried back to the quiet country cottage a hoard of observations to feast upon at leisure.

And what effect would all this have had upon the six novels that Jane Austen did not write? She would not have written of crime, of passion, or of adventure. She would not have been rushed by the importunity of publishers or the flattery of friends into slovenliness or insincerity. But she would have known more. Her sense of security would have been shaken. Her comedy would have suffered. She would have trusted less (this is already perceptible in Persuasion) to dialogue and more to reflection to give us a knowledge of her characters. Those marvellous little speeches which sum up, in a few minutes’ chatter, all that we need in order to know an Admiral Croft or a Mrs. Musgrove for ever, that shorthand, hit-or-miss method which contains chapters of analysis and psychology, would have become too crude to hold all that she now perceived of the complexity of human nature. She would have devised a method, clear and composed as ever, but deeper and more suggestive, for conveying not only what people say, but what they leave unsaid; not only what they are, but what life is. She would have stood farther away from her characters, and seen them more as a group, less as individuals. Her satire, while it played less incessantly, would have been more stringent and severe. She would have been the forerunner of Henry James and of Proust — but enough. Vain are these speculations: the most perfect artist among women, the writer whose books are immortal, died “just as she was beginning to feel confidence in her own success”.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

P. A. d e G é n e s t e t

(1829 – 1861)

Waar het meeste wordt geleden

Het knaapje sluimert! maar de moeder aan zijn sponde

Bespiedt de onvaste rust van ’t krank en lijdend kind;

Ach, hoe dat hoofdje gloeit! ’t Is alles stil in ’t ronde,

Doch in heur ziele met, die vreest, zooveel zij mint.

O God, waar hier op aard wel ’t innigst wordt gestreden?….

Aan ’t kinderziekbed, Heer! Daar buigt ook ’t twijflend hoofd

Des fieren mans zich neêr met staamlende gebeden; –

Geen moeder die niet bidt en in haar God gelooft!

Aan ’t kinderziekbed, Heer! daar worstlen in de harten

Gedachten, waar het hart voor week wordt, of voor breekt.

Daar lijdt een liefde, die bij ’t foltren van haar smarten,

Uw Liefde zoeken moet en vurigst tot Haar smeekt.

Ook nergens, stil geloof, is deze Liefde u nader,

Dan waar uw lijden klimt, bij ’t klimmen der gebeên….

Van ’t krankbed van ons kroost trekt gij ons hart, o Vader

Ten Hemel uwer kindren heen.

1857

.jpg)

P.A. de Génestet gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Génestet, P.A. de

.jpg)

Aan de muze

Mijn god, je ziet dat ik me kan vervelen

dat het me dwars zit als een scheet

dat ik je bovendien dan niet wil delen

vertel dus hoe die Fransman heet!

je kunt de knoflook uit mijn pasta stelen

met al wat jij van dichtkunst weet

in jouw genade, vrouw ontstaan juwelen

al eist het schrijfproces een eed

aan welke dode grootheid mag ik denken

een Mallarmé, Verlaine of die vandaal?

heb geen idee, toe geef me nog wat wenken

voor alle loze woorden in mijn taal

zal ik je dan terstond vergeving schenken

aha, de dichter van Les fleurs du mal!

Kees Godefrooij

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Godefrooij, Kees

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

VIII. Claudine

Un matin d’avril, vers cinq heures, Just Moravaut, garçon boucher, remonta la rue Régis et se dirigea vers l’une des entrées du marché Saint-Maur. A la même heure, Aristide Spiker, marchand de poissons, sortit de la rue du Cherche-Midi par la rue Bérite et se dirigea vers l’entrée du marché opposée à celle de la rue Gerbillon. Just et Aristide marchèrent l’un vers l’autre et, sans dire mot, se bourrèrent la face de coups de poing. Avant que l’on fut venu les séparer, Just avait un oeil gonflé comme un oeuf poché et Aristide le nez rouge comme une framboise meurtrie. On les emmena au poste, et chacun d’eux put réfléchir à son aise sur les vicissitudes et horreurs de la guerre.

Une demi-heure après que cette rixe avait mis en émoi tout le marché, la petite Claudine arriva avec sa mère, la maman Turtaine, dans une grande charrette encombrée de légumes. Claudine sauta vivement à terre, caressa le nez du cheval et se mit à courir pour se réchauffer. C’était merveille de la voir se trémousser avec son madras sur la tête, sa grosse robe de burat gris, ses manchettes de couleur et ses sabots bourrés de paille. Le soleil se levait, jaune comme ces nymphéas qui nagent sur l’eau des étangs ; la brume se dissipait, une bise glaciale sifflait dans l’air, et le vent d’automne sonnait à plein cor ses navrantes fanfares. Les maraîchers arrivaient en foule, soigneusement emmitouflés, la figure enfouie dans une casquette, le nez seul sortant tout violet des plis d’un vieux foulard, les épaules protégées du froid par une couverture de laine grise vergetée de raies noires, les mains enveloppées de gros gants verts. Les uns déchargeaient leur charrette, les autres allaient boire un petit verre chez le marchand de vin, tandis que les chevaux, enchantés de se retrouver, se frottaient les naseaux et hennissaient joyeusement.

La chaussée était encombrée de légumes et de fruits, et un grand potiron, coupé par le milieu et couché sur le dos, arrondissait sa vasque jaune sur la pourpre sombre des pivoines jetées en tas, pêle-mêle, sur le rebord du trottoir.

Trois boutiques étaient seules ouvertes, celles d’un boucher, d’un marchand de vin et d’un pharmacien. La porte vitrée du cabaret était imprégnée d’une buée qui ne laissait voir les buveurs qu’à travers un voile. Ils ressemblaient ainsi à des ombres chinoises. Ces silhouettes dansaient sur le mur et sur la porte comme sur un drap blanc, les nez se dessinaient bizarrement, les moustaches semblaient démesurées, les barbes devenaient colossales et les chapeaux se cassaient de burlesque façon. Par instants, la porte s’ouvrait, un bruit de voix s’échappait de la salle, et celui qui sortait s’enfonçait les mains dans les poches et courait bien vite à sa boutique ou à sa voiture. Tout en travaillant et buvant, on échangeait le bonjour, on se serrait la main, on gloussait, on riait. Le boucher allumait le gaz, jetait sur le dos de ses garçons des charretées de viande ; sa femme bâillait et lavait avec une éponge la table de marbre de la devanture, pendant que, suspendu par les pieds à des crocs en fer fichés au plafond, le cadavre d’un grand boeuf étalait, sous la lumière crue du gaz, le monstrueux écrin de ses viscères. La tête avait été violemment arrachée du tronc et des bouts de nerfs palpitaient encore, convulsés comme des tronçons de vers, tortillés comme des lisérés. L’estomac tout grand ouvert bâillait atrocement et dégorgeait de sa large fosse des pendeloques d’entrailles rouges. Comme en une serre chaude, une végétation merveilleuse s’épanouissait dans ce cadavre. Des lianes de veines jaillissaient de tous côtés, des ramures échevelées fusaient le long du torse, des floraisons d’intestins déployaient leurs violâtres corolles, et de gros bouquets de graisse éclataient tout blancs sur le rouge fouillis des chairs pantelantes.

Le boucher semblait émerveillé par ce spectacle, et près de lui, sur le trottoir, deux vieux paysans avaient appuyé leurs pipes l’une sur l’autre et tiraient de grosses bouffées. Leurs joues s’enflaient comme des ballons et la fumée leur sortait par les narines. Ils aspirèrent une bonne provision d’air froid pour se rafraîchir la bouche, et mirent un petit morceau de papier sur le tabac qui se prit à grésiller et dessina tout flamboyant de capricieuses arabesques sur le papier qui se consumait.

—Voyons, Claudine, dit la mère Turtaine, tu te réchaufferas aussi bien en déchargeant la voiture qu’en sautant, viens m’aider.

—Voilà, maman. Et elle se mit en face de l’aile gauche de la carriole et reçut dans les bras des bottes de fleurs et de salades.

—Dis donc, lui dit une petite paysanne à l’oreille, il paraît que Just et Aristide se sont battus, ce matin: bien sûr pour toi.

—Oh! les vilains garçons! dit Claudine, dont la petite figure devint triste; je leur avais tant recommandé d’être sages!

—ah! tu es bonne! mais ils sont comme deux coqs, ils t’aiment tous les deux, et tu ne t’es pas encore décidée à faire un choix.

—Mais je ne sais pas, moi; je les aime autant l’un que l’autre, et maman ne les aime ni l’un ni l’autre, comment veux-tu que je choisisse?

—Satanée enfant, dit la mère Turtaine, qui sauta lourdement de sa voiture, elle bavarde, elle bavarde, et l’ouvrage n’avance pas. J’aurai aussi vite fait toute seule. Voyons, Claudine, va nettoyer notre case et préparer les chaufferettes. La petite s’éloigna et continua, avec son amie, à disputer des mérites et défauts de ses deux amoureux.

La situation était en effet embarrassante, Claudine les aimait tous deux comme une soeur aimerait deux frères; mais, dame, de là à choisir entre eux un mari, il y avait loin. Just et Aristide ne se ressemblaient pas comme figure, mais chacun, dans son genre, était aussi beau ou aussi laid que l’autre. Aristide était peut-être plus bel homme, mais il témoignait d’un penchant prononcé pour l’adiposité. Just était moins bien taillé, son encolure était moins large, mais il promettait de rester musculeux, et point trivialement bardé de graisse comme son adversaire. Just avait de jolis cheveux blonds, tout frisottants, mais ils n’étaient pas fournis, et, par endroits, l’on entrevoyait sous le buisson une petite clairière. Aristide avait des cheveux blonds, roides et sans grâce, mais d’une nuance plus tendre; et puis, c’était une véritable forêt luxuriante, la raie était à peine tracée, comme un tout petit sentier dans une épaisse forêt. Tous deux étaient francs et bons, mais batailleurs; tous deux n’avaient pas de fortune, mais étaient courageux et ne reculaient pas devant l’ouvrage.

—Enfin, disait la petite Marie, en se posant devant Claudine qui tournait les rubans de son tablier d’un air indécis, cette situation-là ne peut durer, ils finiront par s’égorger. Je parlerai à ta mère, si tu n’oses.

—Oh! non je t’en prie, ne dis rien, maman me gronderait, leur dirait des sottises et leur défendrait de m’adresser la parole.

—Voyons, Claudine, nous allons peser les qualités et les défauts, les avantages et les désavantages de chacun, et puis nous verrons lequel des deux vaut le mieux! D’un côté, Aristide est un brave garçon.

—Oui! oui, pour ça, c’est un brave garçon.

—Mais sais-tu bien qu’il deviendra comme un muid? et dame! c’est bien désagréable d’avoir pour mari un homme dont tout le monde plaint la corpulence. Il est vrai, poursuivit-elle, que Just est un brave garçon.

—Oh! oui, pour ça, c’est un brave garçon.

—Bien, mais sais-tu qu’il demeurera toute sa vie maigre comme un échalas, et, ma foi, je t’avoue qu’il est bien triste de vivre tous les jours avec un homme qui a l’air de mourir de faim.

—De sorte que, reprit en souriant Claudine, le mieux serait d’épouser un mari qui ne fut ni trop gras ni trop maigre; mais alors il ne faut prendre ni Just ni Aristide.

—Ah! mais non! s’écria Marie; ces garçons t’aiment, il faut au moins que l’un des deux soit heureux.

—Chut! je me sauve, j’entends maman qui gronde.

—Ah! bien oui! disait la mère Turtaine d’une voix courroucée, les mains plantées sur les hanches, le ventre proéminent sous son tablier bleu; c’est bien la peine d’élever une jeunesse pour qu’elle écoute ainsi les ordres de sa mère! Elle n’a pas seulement balayé notre place, il n’y a pas moyen de s’y tenir tant il y a d’épluchures.

—Voyons, petite maman, ne me gronde pas, fit sa fille, en prenant un petit air câlin qui ne justifiait que trop l’amour des pauvres garçons pour elle; je ne bavarderai plus autant, je te le promets.

Elle prépara sa devanture et demeura songeuse. Elle se rappelait maintenant que les deux rivaux s’étaient battus, et que c’était pour cela que ni l’un ni l’autre n’avait balayé son petit réduit, ainsi qu’ils avaient coutume de le faire. Pourvu qu’ils ne se soient pas blessés, pensait-elle, et elle se sentait plus d’inclination pour celui qui aurait le plus souffert.

—Voyons, dit sa mère, je vais chercher notre café; que tout soit prêt quand je reviendrai, que je puisse déjeuner tranquillement.

—Est-il vrai, dit Claudine à la femme Truchart, sa voisine et tante, que l’on s’est battu ce matin ici?

—On me l’a dit; c’est deux mauvais sujets; on devrait pendre des batailleurs comme ça, ou les mettre dans l’armée, puisqu’ils aiment les coups.

Petite Claudine se tut et cessa la conversation. Un quart d’heure après, la maman arriva, tenant dans chaque main un grand bol plein d’une liqueur fumante et saumâtre.

-Ah! bien, j’en apprends de belles, cria-t-elle, il paraît que ces deux gredins de Just et d’Aristide se sont battus, ce matin, à cause de toi. Qu’ils s’avisent un peu de rôder autour de nous! c’est moi qui vais les recevoir! Et toi, si tu leur adresses la parole ou si tu réponds à leurs discours, tu auras affaire à moi. A-t-on jamais vu!

La pauvre fille avait le coeur gros et ne pouvait manger; soudain elle pâlit et renversa la moitié de son bol sur sa jupe: les deux adversaires venaient d’entrer dans le marché, l’un avec son oeil bleu, l’autre avec son nez tout escarbouillé. Ils se séparèrent à la porte et chacun s’en fut à sa boutique par une allée différente.

Toute la journée, elle les regardait alternativement, se disant: Le pauvre garçon, comme il doit souffrir avec son visage enflé! Ce nez turgide et sanglant la désespérait. Puis elle regardait l’autre. A-t-il l’oeil abîmé! murmurait-elle. Et cet oeil qui débordait d’un cercle de charbon lui faisait passer de petits frissons dans le dos. Faut-il qu’un homme soit brutal, pensait-elle, pour frapper ainsi un ami aux yeux. Elle se prenait à détester Aristide, puis elle voyait ce nez turgescent, et elle en venait à exécrer le gros Just. Elle y songea toute la nuit et ne put dormir. Que faire, pensait-elle, que faire ? Ce n’est pas de leur faute s’ils m’aiment. Je tâcherai de leur parler demain et je leur ferai promettre de ne plus se battre. Elle s’endormit sur cette heureuse idée et prépara, dans sa petite cervelle, de belles paroles pour les apaiser. Elle s’habilla, le matin, toute songeuse, aida sa mère à atteler le cheval et chemin faisant, de Montrouge au marché, elle repassa son petit discours. La difficulté était de leur parler sans être vue par sa mère. Elle s’ingéniait à trouver des prétextes pour s’échapper un instant de la boutique et parler à chacun d’eux sans être vue par l’autre. Enfin, le hasard me fournira peut-être une occasion et, sur cette pensée consolante, elle fouetta vivement le cheval qui prit le petit trot et fit sonner, dans les rues endormies, les semelles de fer qu’il avait aux pieds.

Les deux rivaux étaient à leur place et se jetaient des regards défiants. Elle eut l’air de ne point les voir, déchargea la voiture et se promit, vers neuf heures, alors que le marché serait rempli de monde, de s’échapper. En effet, vers cette heure, une affluence de femmes mal peignées, couvertes de châles effilochés, jetant un regard de joie sur leurs chiens qui folâtraient dans les ruisseaux, inonda les rues étroites qui enserrent le marché. Sous prétexte de chercher une botte de persil qu’elle avait égarée, Claudine se faufila dans la foule et s’en fut à la boutique de Just. Il pâlit à sa vue, rougit subitement et son oeil devint d’un noir plus foncé; sa boutique était encombrée de clientes, il leur répondait à peine, avait grande envie de les envoyer au diable et n’osait le faire, attendu que son patron était là et le surveillait du coin de l’oeil. «Just,» lui dit-elle enfin à voix basse, oubliant toutes les belles phrases qu’elle avait préparées, promettez-moi de ne plus vous battre.

—Mais, mademoiselle…

—Promettez-moi, ou je me fâche pour toujours avec vous.

—Je vous le promets, dit-il, tout rouge.

—Merci. Et elle se sauva en courant et rentra chez sa mère. Un quart d’heure après, elle parvint également à s’enfuir et s’en fut trouver Aristide qui la regarda d’un air effaré, vacilla sur ses jambes, balbutia quelques mots et fut obligé de s’asseoir, au grand ébahissement des acheteuses, qui crurent qu’il se trouvait mal et se mirent à crier. Elle n’eut que le temps de se sauver. «Mon Dieu! mon Dieu!» murmurait-elle, «quel malheur! Je n’ai pourtant rien fait pour qu’ils m’aiment comme cela, ces pauvres garçons!»

Vers midi, Just s’en vint rôder autour d’elle et lui glissa un petit mot qu’elle s’en fut ouvrir dans la rue: «Je ne puis vivre ainsi, disait-il, je vais vendre mon fonds et quitter le marché. «Ah!» s’écria-t-elle, «celui-ci m’aime le plus; si maman veut, je l’épouse.» Un quart d’heure après, comme elle allait chercher du cerfeuil chez une amie, Aristide lui dit: «Mademoiselle Claudine, je vais m’en aller, je suis trop mal heureux.»

—Ah! mon Dieu! il m’aime autant que l’autre; c’est désespérant d’être aimée ainsi! Et, tout en disant cela, elle éprouvait, malgré elle, une certaine joie à se sentir ainsi adorée.

Elle revint plus perplexe encore. Que faire? Telle était la question qu’elle se posait sans cesse. En attendant, les jours passaient et les amoureux ne partaient pas. Le premier qui partira sera celui qui m’aimera le plus, pensait-elle; puis elle se reprenait et se disait tout bas: Non, celui qui me quittera le premier pourra vivre sans me voir, donc il m’aimera moins. En attendant, chacun restait à sa place, s’étant fait cette réflexion bien simple que partir c’était laisser le champ libre à son adversaire, qui ne partirait certainement pas. Donc, ils s’observaient et éprouvaient de furieuses tentations de se cribler la figure de nouvelles gourmades.

Malheureusement, cet amour insensé que les petits yeux et les bonnes joues de Claudine avaient allumé dans le coeur des pauvres garçons fut bientôt connu de tout le quartier. Le coiffeur d’en face, enchanté d’avoir une occasion de parler, en promenant ses mains graisseuses et son rasoir non moins graisseux sur la figure de ses clients, entra dans d’interminables discussions sur la beauté et la coquetterie de Claudine. Ces propos, grossissant à mesure qu’ils roulaient de bouche en bouche, ne devaient pas tarder à arriver aux oreilles de la mère Turtaine. Un marché, c’est une miniature de ville de province: on y passe son temps à médire de son prochain et à le piller autant que faire se peut, deux occupations agréables, si jamais il en fut. Les concierges du quartier, las de se plaindre de leurs locataires et de déplorer le sort qui les avait faits concierges, saisirent cette occasion d’interrompre leurs doléances et s’empressèrent de dire pis que pendre de la pauvre fille. Exaspérée par tous ces commérages et par toutes ces médisances, la mère Turtaine résolut de l’envoyer chez sa soeur, à Plaisir, dans le département de Seine-et-Oise.

Claudine partit le coeur gros en priant sa mère de la rappeler bientôt près d’elle. Les premiers jours lui semblèrent bien tristes et elle écrivit à sa mère une lettre dans laquelle elle la suppliait de lui permettre de revenir au marché. Bientôt cette lettre qu’elle désirait tant lui causa de terribles craintes. En quelques soirées son sort avait changé. Un soir qu’elle se promenait près de la tremblaie, elle fit rencontre d’un grand et beau garçon dont la mine éveillée et les allures puissantes lui plurent tout d’abord.

La première fois, il la regarda timidement et, sentant les yeux de la jeune fille fixés sur les siens, il baissa la tête, devint rouge du cou aux oreilles et ne put ouvrir la bouche; la seconde fois, il osa l’aborder, mais il balbutia comme un imbécile et devint plus rouge encore que la première fois; la troisième, il ouvrit la bouche, parvint à bredouiller quelques mots, à lui dire qu’il la connaissait, que son père était un grand ami de sa mère, et, depuis ce temps, ils étaient devenus les meilleurs amis du monde.

Le soir, ils s’échappaient, se rencontraient au bas de la côte et se promenaient le long d’un petit ruisseau. Claudine marchait tout doucement, les yeux fixés à terre, les mains dans les poches de son petit tablier, et elle se sentait oppressée de délicieuses épouvantes. Lui la regardait à la dérobée et se mourait d’envie d’embrasser une petite place rose sur laquelle bouffait, comme une touffe d’herbes folles, un petit bouquet de cheveux pâles; vingt fois il fut sur le point de se pencher et d’effleurer de ses lèvres cette rose moussue, puis, au moment où il se courbait et où sa bouche frôlait les cheveux, Claudine faisait un mouvement, et vite il reprenait son calme et marchait à côté d’elle, maudissant sa timidité, se jurant que la première fois il serait plus hardi. Un soir, ils marchaient tout au bord du ruisseau. La lune avait rejeté sa fourrure de nuées blanches et se mirait dans l’eau; on eût dit une faucille d’argent posée sur une bande de moire bleue. Notre amoureux s’approcha de Claudine, et, au moment ou il allait enfin lui embrasser le cou, il aperçut dans le ruisseau l’image de sa bien-aimée qui souriait de le voir si gauche. Cette fois, il perdit la tête et embrassa si fort la petite place rose, qu’elle en resta blanche pendant quelques secondes et devint subitement rouge.

Tandis que Claudine simulait une colère qu’elle était loin de ressentir, Just et Aristide, que leur commune détresse avait rapprochés, alternaient, en des strophes désolées, sur la bonne mine et les charmes de leur fugitive déité. Néanmoins, comme la plus cuisante douleur finit par se calmer, il arriva qu’un beau jour l’un et l’autre se marièrent. Encore qu’elle ne les aimât point, Claudine ne laissa pas que d’être un peu vexée lorsqu’elle apprit cette nouvelle. —Etre si vite oubliée! les hommes sont donc des monstres.

—Vois-tu, ma fille, lui dit sentencieusement la maman Turtaine qui était venue la rejoindre à Plaisir, plus un homme aime, moins longtemps il reste fidèle; retiens bien ça.

—Pourvu que mon amant ne m’aime pas autant que Just et Aristide! pensa Claudine, et elle lui défendit de l’aimer. «Si tu m’aimes beaucoup, je ne t’épouse pas,» dit-elle.

—Mais…

—C’est à prendre ou à laisser.

—J’accepte: il est donc bien entendu, Claudine, que je ne t’aime point, que je te déteste.

—Ah! mais non, je ne te demande pas de me détester, je veux seulement que tu ne m’aimes pas beaucoup tout d’abord.

—Et ensuite?…

—Ensuite, nous verrons.

Quinze jours après, le mariage eut lieu.

Ah! Claudine, la petite place rose est restée rouge depuis cette époque, et votre mari ne vous aime pas! mais quelle couleur arborera-t-elle, alors qu’il vous aimera et que vous lui permettrez de faire sonner sur elle le grelot des baisers?

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

W i l l e m B i l d e r d i j k

(1756-1831)

P o ë z y

Cui mens divinor (H O R A T I U S)

Zing met daavrende oorlogstoonen

Waar de woeste moord in brult,

’t Blinkend loof van zegekroonen

Dat des strijders hoofd omhult:

Brom den donder der musketten —

Kletter ’t ramm’len van het staal —

Bruis het brieschen der genetten —

Na, in Dichterlijken praal.

Kweel het tripplend maagdereien,

’t Ruischen van den zilvren vliet,

Door den toon der veldschalmeien

En het piepend Herdersriet:

Meng aan ’t tjilpnes boschgeschater

Filomeles orgelkeel;

Aan het stortend stroomgeklater,

’t Zuizen van het myrthprieel:

Huppele op uw Cythersnaren

Liefdelust of oorlogsmoed,

Naar het steigren van uw bloed!

Welig zal uw zangtoon vloeien,

Als hy aan de ziel ontstijgt;

Maar, ontbreekt dat innig gloeien,

Arme toonverwoesters, zwijgt!

Ja, die zang zal boezems treffen,

Hart en zin in kluisters slaan,

Zielen, boven de aard verheffen;

Maar, ô wierook aan geen waan; —

Tooi geen eigen hartsgevoelen,

Met een valsch-ontleende pracht: —

Wacht u, op den lof te doelen

Van een nietig wangeslacht!

Ach! die lof van laag gebroedsel,

Aarde en eigenzucht verkleefd,

Is vergif voor zielenvoedsel,

Dampt de lucht waarin gy zweeft.

Neem uw vlucht in hooger kringen,

Van hun ademwalming vrij,

Dan-alleen is ’t waarlijk ZINGEN,

Dan-alleen is ’t POËZY!

Ja, uit eigen hart geschoten,

Is de zangtoon ware zang;

Vrij als Edens lustgenooten,

Kent hy kunst- noch regeldwang.

Neen, de vloeistof waar we in drijven,

Is te hoog voor aardsche vlucht,

En, den echten toon te stijven

Eischt een zuiver Hemellucht.

Waar wy held- of zegepalmen,

Zomerlust of lentebloem,

Waar wy vreugd of liefde galmen,

Zingen we EEN-alleen ten roem!

U, ô bron van ZIJN en LEVEN,

Aan wiens oogwenk alles hangt!

U-alleen zij de eer gegeven,

Welk een stof ons lied omvangt!

Wat wy in het schepsel eeren

Is een dankcijns, U gewijd:

U behoort hy, Heer der Heeren,

U die door U-zelven zijt!

Dan, wat slaan wy slappe wieken

Naar dien zuivren luchtstroom uit,

Eer het zalig morgenkrieken

Zich aan ’t starend oog ontsluit!

Ach, wat zegt dat vleuglenkleppen

Als de gave slagpen faalt,

Om zich steiler vaart te scheppen,

Waar de dag ons tegenstraalt!

Doch Gy, GOËL, schenkt ons krachten,

Gy, der Hemelharpen lof,

Wien van Serafs, Thronen, Machten,

De eergalm weêrklinkt uit ons stof!

Zwak, onzuiver, en ontëngeld

In de sterfelijke borst,

En met wangeluid doormengeld,

U onwaardig, Hemelvorst:

Ja, Verlosser, U onwaardig;

Maar, wanneer Uw Geest ons roert,

Uit een hart, door U wilvaardig,

Tot Uw zetel opgevoerd.

Schenk, ô schenk hun die U loven,

Dropplen uit uw Hemelwel;

Dat zy ’t Aardsch geknars verdoven,

En het vloekgejoel der Hel!

1825.

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Bilderdijk, Willem

.jpg)

Joseph Conrad

(1857-1924)

The Idiots

We were driving along the road from Treguier to Kervanda. We passed at a

smart trot between the hedges topping an earth wall on each side of

the road; then at the foot of the steep ascent before Ploumar the horse

dropped into a walk, and the driver jumped down heavily from the box.

He flicked his whip and climbed the incline, stepping clumsily uphill

by the side of the carriage, one hand on the footboard, his eyes on the

ground. After a while he lifted his head, pointed up the road with the

end of the whip, and said–

“The idiot!”

The sun was shining violently upon the undulating surface of the land.

The rises were topped by clumps of meagre trees, with their branches

showing high on the sky as if they had been perched upon stilts. The

small fields, cut up by hedges and stone walls that zig-zagged over

the slopes, lay in rectangular patches of vivid greens and yellows,

resembling the unskilful daubs of a naive picture. And the landscape was

divided in two by the white streak of a road stretching in long loops

far away, like a river of dust crawling out of the hills on its way to

the sea.

“Here he is,” said the driver, again.

In the long grass bordering the road a face glided past the carriage

at the level of the wheels as we drove slowly by. The imbecile face was

red, and the bullet head with close-cropped hair seemed to lie alone,

its chin in the dust. The body was lost in the bushes growing thick

along the bottom of the deep ditch.

It was a boy’s face. He might have been sixteen, judging from the

size–perhaps less, perhaps more. Such creatures are forgotten by

time, and live untouched by years till death gathers them up into its

compassionate bosom; the faithful death that never forgets in the press

of work the most insignificant of its children.

“Ah! there’s another,” said the man, with a certain satisfaction in his

tone, as if he had caught sight of something expected.

There was another. That one stood nearly in the middle of the road in

the blaze of sunshine at the end of his own short shadow. And he stood

with hands pushed into the opposite sleeves of his long coat, his head

sunk between the shoulders, all hunched up in the flood of heat. From a

distance he had the aspect of one suffering from intense cold.

“Those are twins,” explained the driver.

The idiot shuffled two paces out of the way and looked at us over his

shoulder when we brushed past him. The glance was unseeing and staring,

a fascinated glance; but he did not turn to look after us. Probably the

image passed before the eyes without leaving any trace on the misshapen

brain of the creature. When we had topped the ascent I looked over the

hood. He stood in the road just where we had left him.

The driver clambered into his seat, clicked his tongue, and we went

downhill. The brake squeaked horribly from time to time. At the foot he

eased off the noisy mechanism and said, turning half round on his box–

“We shall see some more of them by-and-by.”

“More idiots? How many of them are there, then?” I asked.

“There’s four of them–children of a farmer near Ploumar here. . . . The

parents are dead now,” he added, after a while. “The grandmother lives

on the farm. In the daytime they knock about on this road, and they come

home at dusk along with the cattle. . . . It’s a good farm.”

We saw the other two: a boy and a girl, as the driver said. They were

dressed exactly alike, in shapeless garments with petticoat-like skirts.

The imperfect thing that lived within them moved those beings to howl

at us from the top of the bank, where they sprawled amongst the tough

stalks of furze. Their cropped black heads stuck out from the bright

yellow wall of countless small blossoms. The faces were purple with

the strain of yelling; the voices sounded blank and cracked like a

mechanical imitation of old people’s voices; and suddenly ceased when we

turned into a lane.

I saw them many times in my wandering about the country. They lived on

that road, drifting along its length here and there, according to the

inexplicable impulses of their monstrous darkness. They were an

offence to the sunshine, a reproach to empty heaven, a blight on the

concentrated and purposeful vigour of the wild landscape. In time the

story of their parents shaped itself before me out of the listless

answers to my questions, out of the indifferent words heard in wayside

inns or on the very road those idiots haunted. Some of it was told by

an emaciated and sceptical old fellow with a tremendous whip, while we

trudged together over the sands by the side of a two-wheeled cart loaded

with dripping seaweed. Then at other times other people confirmed and

completed the story: till it stood at last before me, a tale formidable

and simple, as they always are, those disclosures of obscure trials

endured by ignorant hearts.

When he returned from his military service Jean-Pierre Bacadou found the

old people very much aged. He remarked with pain that the work of the

farm was not satisfactorily done. The father had not the energy of

old days. The hands did not feel over them the eye of the master.

Jean-Pierre noted with sorrow that the heap of manure in the courtyard

before the only entrance to the house was not so large as it should

have been. The fences were out of repair, and the cattle suffered from

neglect. At home the mother was practically bedridden, and the girls

chattered loudly in the big kitchen, unrebuked, from morning to night.

He said to himself: “We must change all this.” He talked the matter over

with his father one evening when the rays of the setting sun entering

the yard between the outhouses ruled the heavy shadows with luminous

streaks. Over the manure heap floated a mist, opal-tinted and odorous,

and the marauding hens would stop in their scratching to examine with

a sudden glance of their round eye the two men, both lean and tall,

talking in hoarse tones. The old man, all twisted with rheumatism and

bowed with years of work, the younger bony and straight, spoke without

gestures in the indifferent manner of peasants, grave and slow.

But before the sun had set the father had submitted to the sensible

arguments of the son. “It is not for me that I am speaking,” insisted

Jean-Pierre. “It is for the land. It’s a pity to see it badly used. I am

not impatient for myself.” The old fellow nodded over his stick. “I dare

say; I dare say,” he muttered. “You may be right. Do what you like. It’s

the mother that will be pleased.”

The mother was pleased with her daughter-in-law. Jean-Pierre brought

the two-wheeled spring-cart with a rush into the yard. The gray horse

galloped clumsily, and the bride and bridegroom, sitting side by side,

were jerked backwards and forwards by the up and down motion of the

shafts, in a manner regular and brusque. On the road the distanced

wedding guests straggled in pairs and groups. The men advanced with

heavy steps, swinging their idle arms. They were clad in town clothes;

jackets cut with clumsy smartness, hard black hats, immense boots,

polished highly. Their women all in simple black, with white caps and

shawls of faded tints folded triangularly on the back, strolled lightly

by their side. In front the violin sang a strident tune, and the biniou

snored and hummed, while the player capered solemnly, lifting high his

heavy clogs. The sombre procession drifted in and out of the narrow

lanes, through sunshine and through shade, between fields and hedgerows,

scaring the little birds that darted away in troops right and left. In

the yard of Bacadou’s farm the dark ribbon wound itself up into a mass

of men and women pushing at the door with cries and greetings. The

wedding dinner was remembered for months. It was a splendid feast in the

orchard. Farmers of considerable means and excellent repute were to be

found sleeping in ditches, all along the road to Treguier, even as late

as the afternoon of the next day. All the countryside participated in

the happiness of Jean-Pierre. He remained sober, and, together with his

quiet wife, kept out of the way, letting father and mother reap their

due of honour and thanks. But the next day he took hold strongly, and

the old folks felt a shadow–precursor of the grave–fall upon them

finally. The world is to the young.

When the twins were born there was plenty of room in the house, for the

mother of Jean-Pierre had gone away to dwell under a heavy stone in the

cemetery of Ploumar. On that day, for the first time since his son’s

marriage, the elder Bacadou, neglected by the cackling lot of strange

women who thronged the kitchen, left in the morning his seat under the

mantel of the fireplace, and went into the empty cow-house, shaking his

white locks dismally. Grandsons were all very well, but he wanted his

soup at midday. When shown the babies, he stared at them with a fixed

gaze, and muttered something like: “It’s too much.” Whether he meant too

much happiness, or simply commented upon the number of his descendants,

it is impossible to say. He looked offended–as far as his old wooden

face could express anything; and for days afterwards could be seen,

almost any time of the day, sitting at the gate, with his nose over his

knees, a pipe between his gums, and gathered up into a kind of raging

concentrated sulkiness. Once he spoke to his son, alluding to the

newcomers with a groan: “They will quarrel over the land.” “Don’t bother

about that, father,” answered Jean-Pierre, stolidly, and passed, bent

double, towing a recalcitrant cow over his shoulder.

He was happy, and so was Susan, his wife. It was not an ethereal joy

welcoming new souls to struggle, perchance to victory. In fourteen years

both boys would be a help; and, later on, Jean-Pierre pictured two big

sons striding over the land from patch to patch, wringing tribute from

the earth beloved and fruitful. Susan was happy too, for she did not

want to be spoken of as the unfortunate woman, and now she had children

no one could call her that. Both herself and her husband had seen

something of the larger world–he during the time of his service; while

she had spent a year or so in Paris with a Breton family; but had been

too home-sick to remain longer away from the hilly and green country,

set in a barren circle of rocks and sands, where she had been born.

She thought that one of the boys ought perhaps to be a priest, but said

nothing to her husband, who was a republican, and hated the “crows,”

as he called the ministers of religion. The christening was a splendid

affair. All the commune came to it, for the Bacadous were rich

and influential, and, now and then, did not mind the expense. The

grandfather had a new coat.

Some months afterwards, one evening when the kitchen had been swept,

and the door locked, Jean-Pierre, looking at the cot, asked his wife:

“What’s the matter with those children?” And, as if these words, spoken

calmly, had been the portent of misfortune, she answered with a loud

wail that must have been heard across the yard in the pig-sty; for

the pigs (the Bacadous had the finest pigs in the country) stirred and

grunted complainingly in the night. The husband went on grinding his

bread and butter slowly, gazing at the wall, the soup-plate smoking

under his chin. He had returned late from the market, where he had

overheard (not for the first time) whispers behind his back. He revolved

the words in his mind as he drove back. “Simple! Both of them. . . .

Never any use! . . . Well! May be, may be. One must see. Would ask his

wife.” This was her answer. He felt like a blow on his chest, but said

only: “Go, draw me some cider. I am thirsty!”

She went out moaning, an empty jug in her hand. Then he arose, took up

the light, and moved slowly towards the cradle. They slept. He looked at

them sideways, finished his mouthful there, went back heavily, and sat

down before his plate. When his wife returned he never looked up,

but swallowed a couple of spoonfuls noisily, and remarked, in a dull

manner–

“When they sleep they are like other people’s children.”

She sat down suddenly on a stool near by, and shook with a silent

tempest of sobs, unable to speak. He finished his meal, and remained

idly thrown back in his chair, his eyes lost amongst the black rafters

of the ceiling. Before him the tallow candle flared red and straight,

sending up a slender thread of smoke. The light lay on the rough,

sunburnt skin of his throat; the sunk cheeks were like patches of

darkness, and his aspect was mournfully stolid, as if he had ruminated

with difficulty endless ideas. Then he said, deliberately–

“We must see . . . consult people. Don’t cry. . . . They won’t all be

like that . . . surely! We must sleep now.”

After the third child, also a boy, was born, Jean-Pierre went about his

work with tense hopefulness. His lips seemed more narrow, more tightly

compressed than before; as if for fear of letting the earth he tilled

hear the voice of hope that murmured within his breast. He watched the

child, stepping up to the cot with a heavy clang of sabots on the stone

floor, and glanced in, along his shoulder, with that indifference which

is like a deformity of peasant humanity. Like the earth they master and

serve, those men, slow of eye and speech, do not show the inner fire; so

that, at last, it becomes a question with them as with the earth,

what there is in the core: heat, violence, a force mysterious and

terrible–or nothing but a clod, a mass fertile and inert, cold and

unfeeling, ready to bear a crop of plants that sustain life or give

death.

The mother watched with other eyes; listened with otherwise expectant

ears. Under the high hanging shelves supporting great sides of bacon

overhead, her body was busy by the great fireplace, attentive to the pot

swinging on iron gallows, scrubbing the long table where the field hands

would sit down directly to their evening meal. Her mind remained by the

cradle, night and day on the watch, to hope and suffer. That child, like

the other two, never smiled, never stretched its hands to her, never

spoke; never had a glance of recognition for her in its big black eyes,

which could only stare fixedly at any glitter, but failed hopelessly to

follow the brilliance of a sun-ray slipping slowly along the floor.

When the men were at work she spent long days between her three idiot

children and the childish grandfather, who sat grim, angular, and

immovable, with his feet near the warm ashes of the fire. The feeble

old fellow seemed to suspect that there was something wrong with his

grandsons. Only once, moved either by affection or by the sense of

proprieties, he attempted to nurse the youngest. He took the boy up from

the floor, clicked his tongue at him, and essayed a shaky gallop of his

bony knees. Then he looked closely with his misty eyes at the child’s

face and deposited him down gently on the floor again. And he sat, his

lean shanks crossed, nodding at the steam escaping from the cooking-pot

with a gaze senile and worried.

Then mute affliction dwelt in Bacadou’s farmhouse, sharing the breath

and the bread of its inhabitants; and the priest of the Ploumar parish

had great cause for congratulation. He called upon the rich landowner,

the Marquis de Chavanes, on purpose to deliver himself with joyful

unction of solemn platitudes about the inscrutable ways of Providence.

In the vast dimness of the curtained drawing-room, the little man,

resembling a black bolster, leaned towards a couch, his hat on

his knees, and gesticulated with a fat hand at the elongated,

gracefully-flowing lines of the clear Parisian toilette from which the

half-amused, half-bored marquise listened with gracious languor. He was

exulting and humble, proud and awed. The impossible had come to pass.

Jean-Pierre Bacadou, the enraged republican farmer, had been to mass

last Sunday–had proposed to entertain the visiting priests at the next

festival of Ploumar! It was a triumph for the Church and for the good

cause. “I thought I would come at once to tell Monsieur le Marquis. I

know how anxious he is for the welfare of our country,” declared the

priest, wiping his face. He was asked to stay to dinner.

The Chavanes returning that evening, after seeing their guest to the

main gate of the park, discussed the matter while they strolled in

the moonlight, trailing their long shadows up the straight avenue of

chestnuts. The marquise, a royalist of course, had been mayor of the

commune which includes Ploumar, the scattered hamlets of the coast, and

the stony islands that fringe the yellow flatness of the sands. He had

felt his position insecure, for there was a strong republican element in

that part of the country; but now the conversion of Jean-Pierre made

him safe. He was very pleased. “You have no idea how influential

those people are,” he explained to his wife. “Now, I am sure, the next

communal election will go all right. I shall be re-elected.” “Your

ambition is perfectly insatiable, Charles,” exclaimed the marquise,

gaily. “But, ma chere amie,” argued the husband, seriously, “it’s most

important that the right man should be mayor this year, because of the

elections to the Chamber. If you think it amuses me . . .”

Jean-Pierre had surrendered to his wife’s mother. Madame Levaille was

a woman of business, known and respected within a radius of at least

fifteen miles. Thick-set and stout, she was seen about the country, on

foot or in an acquaintance’s cart, perpetually moving, in spite of her

fifty-eight years, in steady pursuit of business. She had houses in all

the hamlets, she worked quarries of granite, she freighted coasters

with stone–even traded with the Channel Islands. She was broad-cheeked,

wide-eyed, persuasive in speech: carrying her point with the placid and

invincible obstinacy of an old woman who knows her own mind. She very

seldom slept for two nights together in the same house; and the wayside

inns were the best places to inquire in as to her whereabouts. She had

either passed, or was expected to pass there at six; or somebody, coming

in, had seen her in the morning, or expected to meet her that evening.

After the inns that command the roads, the churches were the buildings

she frequented most. Men of liberal opinions would induce small children

to run into sacred edifices to see whether Madame Levaille was there,

and to tell her that so-and-so was in the road waiting to speak to her

about potatoes, or flour, or stones, or houses; and she would curtail

her devotions, come out blinking and crossing herself into the sunshine;

ready to discuss business matters in a calm, sensible way across a table

in the kitchen of the inn opposite. Latterly she had stayed for a few

days several times with her son-in-law, arguing against sorrow and

misfortune with composed face and gentle tones. Jean-Pierre felt the

convictions imbibed in the regiment torn out of his breast–not by

arguments but by facts. Striding over his fields he thought it over.

There were three of them. Three! All alike! Why? Such things did not

happen to everybody–to nobody he ever heard of. One–might pass. But

three! All three. Forever useless, to be fed while he lived and . . .

What would become of the land when he died? This must be seen to. He

would sacrifice his convictions. One day he told his wife–

“See what your God will do for us. Pay for some masses.”

Susan embraced her man. He stood unbending, then turned on his heels and

went out. But afterwards, when a black soutane darkened his doorway,

he did not object; even offered some cider himself to the priest.

He listened to the talk meekly; went to mass between the two women;

accomplished what the priest called “his religious duties” at Easter.

That morning he felt like a man who had sold his soul. In the afternoon

he fought ferociously with an old friend and neighbour who had remarked

that the priests had the best of it and were now going to eat the

priest-eater. He came home dishevelled and bleeding, and happening to

catch sight of his children (they were kept generally out of the way),

cursed and swore incoherently, banging the table. Susan wept. Madame

Levaille sat serenely unmoved. She assured her daughter that “It will

pass;” and taking up her thick umbrella, departed in haste to see after

a schooner she was going to load with granite from her quarry.

A year or so afterwards the girl was born. A girl. Jean-Pierre heard of

it in the fields, and was so upset by the news that he sat down on the

boundary wall and remained there till the evening, instead of going home