Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Kaffa begreep heel goed waar het de slager om te doen was. Hij zou kunnen weigeren tegen Azurri te spelen, maar achteraf zou de man het kunnen uitleggen als lafheid. Kaffa voelde zich niet in beste conditie. Zijn handen trilden.

Kaffa begreep heel goed waar het de slager om te doen was. Hij zou kunnen weigeren tegen Azurri te spelen, maar achteraf zou de man het kunnen uitleggen als lafheid. Kaffa voelde zich niet in beste conditie. Zijn handen trilden.

Het gebeuren met de waarzegger werkte op zijn zenuwen. Toch besloot hij de uitdaging aan te nemen. Met kracht gooide Kaffa het mes zo diep in het land van Azurri dat zelfs een deel van het heft in de grond drong. Hij sneed een stuk van het gebied van zijn tegenstander af. Worp na worp wist hij grote stukken land van de slager te veroveren. Het leek erop dat hij zou gaan winnen, zonder dat de slager ook maar één keer aan de beurt was geweest. Maar het land van de slager werd zo klein dat Kaffa’s laatste worp ernaast ging. Het mes viel buiten de grenzen. Kaffa was af. Hij trok het mes uit de grond en wierp het naar de slager, die het handig opving, gewend als hij was met messen om te gaan. Om te zien of het scherp genoeg voor hem was, zette de slager het op zijn arm en schoor een baan haren af. Spuwde op het lemmet en wreef het droog op de rug van zijn hand. Hij gooide het mes in Kaffa’s land en won in één keer het grootste deel van diens gebied. Voor zijn volgende worp bekeek Azurri het mes opnieuw, spuwde op het lemmet en mikte. Het vochtige mes schoot iets te vroeg uit zijn hand en sloeg met een knal tegen de stam van de meidoorn. Het lemmet knapte af, het mes schoot als een boemerang naar de slager terug en schoof in zijn voet. Kaffa vloekte. Hij raapte het heft op en woog het in zijn hand. Zijn beste mes was nu waardeloos. Hij wilde Azurri’s schoen losmaken, maar voelde dat het trillen van zijn linkerhand door zijn hele lichaam kroop. Azurri’s vrouw kwam toelopen. Ze hielp haar man met het uittrekken van zijn schoen. Het bloed stroomde uit de voet en bleef als een korst op het droge zand achter. De vrouw bekeek de wonde, maar dat maakte haar niet veel wijzer. Ze goot er jenever over, om infectie te voorkomen. Om het bloed sneller te doen stollen, legde ze er een zakje gedroogde kruiden op en verbond de wond. Het gezicht van de slager was van pijn vertrokken. Om zijn voet niet te zien keek hij naar de bakfiets vol varkens, die naast de spoelbak stond. Nu hij kennis had gemaakt met de scherpte van een mes, zou hij moeten begrijpen hoe vreselijk het lot van de varkens was. Maar waarschijnlijk had zijn beroep hem te zeer afgestompt om dat gevoel op te brengen. Door alle drukte was Kaffa nogal van streek. Hij borg de resten van het mes in de dekenzak, die in de meidoorn hing, haalde een nieuw mes tevoorschijn en veegde de lijnen van de landen uit om het spel opnieuw te beginnen.

Met de punt van het nieuwe mes tekende hij eerst de as die de grens van de twee landen was, daarna de cirkel zelf. Ondanks de pijn nam Azurri het mes van Kaffa aan en gooide. Hij kon slechts een klein deel van het land van Kaffa winnen voordat zijn mes plat viel. Daarna was de beurt aan Kaffa. Hij voelde dat het mes in zijn handen talmde. Zijn hand trilde heftig. Hij móést gooien. Hij probeerde zuiver te mikken. Het mes viel languit neer. Azurri lachte. Met de volgende worpen wist hij zoveel van Kaffa te winnen dat die geen land meer had om er zijn koning in kwijt te kunnen. Kaffa begreep dat hij met dit verlies een stuk van het aanzien verloor dat hij, kampioen, had opgebouwd. Hij kon het zich niet permitteren verslagen te worden. Bij elk verder verlies zou hij een deel van zijn greep op het plein kwijtraken. Hij zou er de enige reden voor zijn aanwezigheid in het dorp door verliezen. De koning van het plein wankelde.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (34)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

2. A Society

(from: Monday or Tuesday)

This is how it all came about. Six or seven of us were sitting one day after tea. Some were gazing across the street into the windows of a milliner’s shop where the light still shone brightly upon scarlet feathers and golden slippers. Others were idly occupied in building little towers of sugar upon the edge of the tea tray.

After a time, so far as I can remember, we drew round the fire and began as usual to praise men — how strong, how noble, how brilliant, how courageous, how beautiful they were — how we envied those who by hook or by crook managed to get attached to one for life — when Poll, who had said nothing, burst into tears. Poll, I must tell you, has always been queer. For one thing her father was a strange man. He left her a fortune in his will, but on condition that she read all the books in the London Library. We comforted her as best we could; but we knew in our hearts how vain it was. For though we like her, Poll is no beauty; leaves her shoe laces untied; and must have been thinking, while we praised men, that not one of them would ever wish to marry her. At last she dried her tears. For some time we could make nothing of what she said. Strange enough it was in all conscience. She told us that, as we knew, she spent most of her time in the London Library, reading. She had begun, she said, with English literature on the top floor; and was steadily working her way down to the Times on the bottom. And now half, or perhaps only a quarter, way through a terrible thing had happened. She could read no more. Books were not what we thought them. “Books,” she cried, rising to her feet and speaking with an intensity of desolation which I shall never forget, “are for the most part unutterably bad!”

Of course we cried out that Shakespeare wrote books, and Milton and Shelley.

“Oh, yes,” she interrupted us. “You’ve been well taught, I can see. But you are not members of the London Library.” Here her sobs broke forth anew. At length, recovering a little, she opened one of the pile of books which she always carried about with her —“From a Window” or “In a Garden,” or some such name as that it was called, and it was written by a man called Benton or Henson, or something of that kind. She read the first few pages. We listened in silence. “But that’s not a book,” someone said. So she chose another. This time it was a history, but I have forgotten the writer’s name. Our trepidation increased as she went on. Not a word of it seemed to be true, and the style in which it was written was execrable.

“Poetry! Poetry!” we cried, impatiently.

“Read us poetry!” I cannot describe the desolation which fell upon us as she opened a little volume and mouthed out the verbose, sentimental foolery which it contained.

“It must have been written by a woman,” one of us urged. But no. She told us that it was written by a young man, one of the most famous poets of the day. I leave you to imagine what the shock of the discovery was. Though we all cried and begged her to read no more, she persisted and read us extracts from the Lives of the Lord Chancellors. When she had finished, Jane, the eldest and wisest of us, rose to her feet and said that she for one was not convinced.

“Why,” she asked, “if men write such rubbish as this, should our mothers have wasted their youth in bringing them into the world?”

We were all silent; and, in the silence, poor Poll could be heard sobbing out, “Why, why did my father teach me to read?”

Clorinda was the first to come to her senses. “It’s all our fault,” she said. “Every one of us knows how to read. But no one, save Poll, has ever taken the trouble to do it. I, for one, have taken it for granted that it was a woman’s duty to spend her youth in bearing children. I venerated my mother for bearing ten; still more my grandmother for bearing fifteen; it was, I confess, my own ambition to bear twenty. We have gone on all these ages supposing that men were equally industrious, and that their works were of equal merit. While we have borne the children, they, we supposed, have borne the books and the pictures. We have populated the world. They have civilized it. But now that we can read, what prevents us from judging the results? Before we bring another child into the world we must swear that we will find out what the world is like.”

So we made ourselves into a society for asking questions. One of us was to visit a man-of-war; another was to hide herself in a scholar’s study; another was to attend a meeting of business men; while all were to read books, look at pictures, go to concerts, keep our eyes open in the streets, and ask questions perpetually. We were very young. You can judge of our simplicity when I tell you that before parting that night we agreed that the objects of life were to produce good people and good books. Our questions were to be directed to finding out how far these objects were now attained by men. We vowed solemnly that we would not bear a single child until we were satisfied.

Off we went then, some to the British Museum; others to the King’s Navy; some to Oxford; others to Cambridge; we visited the Royal Academy and the Tate; heard modern music in concert rooms, went to the Law Courts, and saw new plays. No one dined out without asking her partner certain questions and carefully noting his replies. At intervals we met together and compared our observations. Oh, those were merry meeting! Never have I laughed so much as I did when Rose read her notes upon “Honour” and described how she had dressed herself as an Ethiopian Prince and gone aboard one of His Majesty’s ships. Discovering the hoax, the Captain visited her (now disguised as a private gentleman) and demanded that honour should be satisfied. “But how?” she asked. “How?” he bellowed. “With the cane of course!” Seeing that he was beside himself with rage and expecting that her last moment had come, she bent over and received, to her amazement, six light taps upon the behind. “The honour of the British Navy is avenged!” he cried, and, raising herself, she saw him with the sweat pouring down his face holding out a trembling right hand. “Away!” she exclaimed, striking an attitude and imitating the ferocity of his own expression, “My honour has still to be satisfied!” “Spoken like a gentleman!” he returned, and fell into profound thought. “If six strokes avenge the honour of the King’s Navy,” he mused, “how many avenge the honour of a private gentleman?” He said he would prefer to lay the case before his brother officers. She replied haughtily that she could not wait. He praised her sensibility. “Let me see,” he cried suddenly, “did your father keep a carriage?” “No,” she said. “Or a riding horse?” “We had a donkey,” she bethought her, “which drew the mowing machine.” At this his face lighted. “My mother’s name —” she added. “For God’s sake, man, don’t mention your mother’s name!” he shrieked, trembling like an aspen and flushing to the roots of his hair, and it was ten minutes at least before she could induce him to proceed. At length he decreed that if she gave him four strokes and a half in the small of the back at a spot indicated by himself (the half conceded, he said, in recognition of the fact that her great grandmother’s uncle was killed at Trafalgar) it was his opinion that her honour would be as good as new. This was done; they retired to a restaurant; drank two bottles of wine for which he insisted upon paying; and parted with protestations of eternal friendship.

Then we had Fanny’s account of her visit to the Law Courts. At her first visit she had come to the conclusion that the Judges were either made of wood or were impersonated by large animals resembling man who had been trained to move with extreme dignity, mumble and nod their heads. To test her theory she had liberated a handkerchief of bluebottles at the critical moment of a trial, but was unable to judge whether the creatures gave signs of humanity for the buzzing of the flies induced so sound a sleep that she only woke in time to see the prisoners led into the cells below. But from the evidence she brought we voted that it is unfair to suppose that the Judges are men.

Helen went to the Royal Academy, but when asked to deliver her report upon the pictures she began to recite from a pale blue volume, “O! for the touch of a vanished hand and the sound of a voice that is still. Home is the hunter, home from the hill. He gave his bridle reins a shake. Love is sweet, love is brief. Spring, the fair spring, is the year’s pleasant King. O! to be in England now that April’s there. Men must work and women must weep. The path of duty is the way to glory —” We could listen to no more of this gibberish.

“We want no more poetry!” we cried.

“Daughters of England!” she began, but here we pulled her down, a vase of water getting spilt over her in the scuffle.

“Thank God!” she exclaimed, shaking herself like a dog. “Now I’ll roll on the carpet and see if I can’t brush off what remains of the Union Jack. Then perhaps —” here she rolled energetically. Getting up she began to explain to us what modern pictures are like when Castalia stopped her.

“What is the average size of a picture?” she asked. “Perhaps two feet by two and a half,” she said. Castalia made notes while Helen spoke, and when she had done, and we were trying not to meet each other’s eyes, rose and said, “At your wish I spent last week at Oxbridge, disguised as a charwoman. I thus had access to the rooms of several Professors and will now attempt to give you some idea — only,” she broke off, “I can’t think how to do it. It’s all so queer. These Professors,” she went on, “live in large houses built round grass plots each in a kind of cell by himself. Yet they have every convenience and comfort. You have only to press a button or light a little lamp. Theirs papers are beautifully filed. Books abound. There are no children or animals, save half a dozen stray cats and one aged bullfinch — a cock. I remember,” she broke off, “an Aunt of mine who lived at Dulwich and kept cactuses. You reached the conservatory through the double drawing-room, and there, on the hot pipes, were dozens of them, ugly, squat, bristly little plants each in a separate pot. Once in a hundred years the Aloe flowered, so my Aunt said. But she died before that happened —” We told her to keep to the point. “Well,” she resumed, “when Professor Hobkin was out, I examined his life work, an edition of Sappho. It’s a queer looking book, six or seven inches thick, not all by Sappho. Oh, no. Most of it is a defence of Sappho’s chastity, which some German had denied, add I can assure you the passion with which these two gentlemen argued, the learning they displayed, the prodigious ingenuity with which they disputed the use of some implement which looked to me for all the world like a hairpin astounded me; especially when the door opened and Professor Hobkin himself appeared. A very nice, mild, old gentleman, but what could he know about chastity?” We misunderstood her.

“No, no,” she protested, “he’s the soul of honour I’m sure — not that he resembled Rose’s sea captain in the least. I was thinking rather of my Aunt’s cactuses. What could they know about chastity?”

Again we told her not to wander from the point — did the Oxbridge professors help to produce good people and good books? — the objects of life.

“There!” she exclaimed. “It never struck me to ask. It never occurred to me that they could possibly produce anything.”

“I believe,” said Sue, “that you made some mistake. Probably Professor Hobkin was a gynecologist. A scholar is a very different sort of man. A scholar is overflowing with humour and invention — perhaps addicted to wine, but what of that? — a delightful companion, generous, subtle, imaginative — as stands to reason. For he spends his life in company with the finest human beings that have ever existed.”

“Hum,” said Castalia. “Perhaps I’d better go back and try again.”

Some three months later it happened that I was sitting alone when Castalia entered. I don’t know what it was in the look of her that so moved me; but I could not restrain myself, and, dashing across the room, I clasped her in my arms. Not only was she very beautiful; she seemed also in the highest spirits. “How happy you look!” I exclaimed, as she sat down.

“I’ve been at Oxbridge,” she said.

“Asking questions?”

“Answering them,” she replied.

“You have not broken our vows?” I said anxiously, noticing something about her figure.

“Oh, the vow,” she said casually. “I’m going to have a baby, if that’s what you mean. You can’t imagine,” she burst out, “how exciting, how beautiful, how satisfying —”

“What is?” I asked.

“To — to — answer questions,” she replied in some confusion. Whereupon she told me the whole of her story. But in the middle of an account which interested and excited me more than anything I had ever heard, she gave the strangest cry, half whoop, half holloa —

“Chastity! Chastity! Where’s my chastity!” she cried. “Help Ho! The scent bottle!”

There was nothing in the room but a cruet containing mustard, which I was about to administer when she recovered her composure.

“You should have thought of that three months ago,” I said severely.

“True,” she replied. “There’s not much good in thinking of it now. It was unfortunate, by the way, that my mother had me called Castalia.”

“Oh, Castalia, your mother —” I was beginning when she reached for the mustard pot.

“No, no, no,” she said, shaking her head. “If you’d been a chaste woman yourself you would have screamed at the sight of me — instead of which you rushed across the room and took me in your arms. No, Cassandra. We are neither of us chaste.” So we went on talking.

Meanwhile the room was filling up, for it was the day appointed to discuss the results of our observations. Everyone, I thought, felt as I did about Castalia. They kissed her and said how glad they were to see her again. At length, when we were all assembled, Jane rose and said that it was time to begin. She began by saying that we had now asked questions for over five years, and that though the results were bound to be inconclusive — here Castalia nudged me and whispered that she was not so sure about that. Then she got up, and, interrupting Jane in the middle of a sentence, said:

“Before you say any more, I want to know — am I to stay in the room? Because,” she added, “I have to confess that I am an impure woman.”

Everyone looked at her in astonishment.

“You are going to have a baby?” asked Jane.

She nodded her head.

It was extraordinary to see the different expressions on their faces. A sort of hum went through the room, in which I could catch the words “impure,” “baby,” “Castalia,” and so on. Jane, who was herself considerably moved, put it to us:

“Shall she go? Is she impure?”

Such a roar filled the room as might have been heard in the street outside.

“No! No! No! Let her stay! Impure? Fiddlesticks!” Yet I fancied that some of the youngest, girls of nineteen or twenty, held back as if overcome with shyness. Then we all came about her and began asking questions, and at last I saw one of the youngest, who had kept in the background, approach shyly and say to her:

“What is chastity then? I mean is it good, or is it bad, or is it nothing at all?” She replied so low that I could not catch what she said.

“You know I was shocked,” said another, “for at least ten minutes.”

“In my opinion,” said Poll, who was growing crusty from always reading in the London Library, “chastity is nothing but ignorance — a most discreditable state of mind. We should admit only the unchaste to our society. I vote that Castalia shall be our President.”

This was violently disputed.

“It is as unfair to brand women with chastity as with unchastity,” said Poll. “Some of us haven’t the opportunity either. Moreover, I don’t believe Cassy herself maintains that she acted as she did from a pure love of knowledge.”

“He is only twenty-one and divinely beautiful,” said Cassy, with a ravishing gesture.

“I move,” said Helen, “that no one be allowed to talk of chastity or unchastity save those who are in love.”

“Oh, bother,” said Judith, who had been enquiring into scientific matters, “I’m not in love and I’m longing to explain my measures for dispensing with prostitutes and fertilizing virgins by Act of Parliament.”

She went on to tell us of an invention of hers to be erected at Tube stations and other public resorts, which, upon payment of a small fee, would safeguard the nation’s health, accommodate its sons, and relieve its daughters. Then she had contrived a method of preserving in sealed tubes the germs of future Lord Chancellors “or poets or painters or musicians,” she went on, “supposing, that is to say, that these breeds are not extinct, and that women still wish to bear children —”

“Of course we wish to bear children!” cried Castalia, impatiently. Jane rapped the table.

“That is the very point we are met to consider,” she said. “For five years we have been trying to find out whether we are justified in continuing the human race. Castalia has anticipated our decision. But it remains for the rest of us to make up our minds.”

Here one after another of our messengers rose and delivered their reports. The marvels of civilisation far exceeded our expectations, and, as we learnt for the first time how man flies in the air, talks across space, penetrates to the heart of an atom, and embraces the universe in his speculations, a murmur of admiration burst from our lips.

“We are proud,” we cried, “that our mothers sacrificed their youth in such a cause as this!” Castalia, who had been listening intently, looked prouder than all the rest. Then Jane reminded us that we had still much to learn, and Castalia begged us to make haste. On we went through a vast tangle of statistics. We learnt that England has a population of so many millions, and that such and such a proportion of them is constantly hungry and in prison; that the average size of a working man’s family is such, and that so great a percentage of women die from maladies incident to childbirth. Reports were read of visits to factories, shops, slums, and dockyards. Descriptions were given of the Stock Exchange, of a gigantic house of business in the City, and of a Government Office. The British Colonies were now discussed, and some account was given of our rule in India, Africa and Ireland. I was sitting by Castalia and I noticed her uneasiness.

“We shall never come to any conclusion at all at this rate,” she said. “As it appears that civilisation is so much more complex than we had any notion, would it not be better to confine ourselves to our original enquiry? We agreed that it was the object of life to produce good people and good books. All this time we have been talking of aeroplanes, factories, and money. Let us talk about men themselves and their arts, for that is the heart of the matter.”

So the diners out stepped forward with long slips of paper containing answers to their questions. These had been framed after much consideration. A good man, we had agreed, must at any rate be honest, passionate, and unworldly. But whether or not a particular man possessed those qualities could only be discovered by asking questions, often beginning at a remote distance from the centre. Is Kensington a nice place to live in? Where is your son being educated — and your daughter? Now please tell me, what do you pay for your cigars? By the way, is Sir Joseph a baronet or only a knight? Often it seemed that we learnt more from trivial questions of this kind than from more direct ones. “I accepted my peerage,” said Lord Bunkum, “because my wife wished it.” I forget how many titles were accepted for the same reason. “Working fifteen hours out of the twenty-four, as I do —” ten thousand professional men began.

“No, no, of course you can neither read nor write. But why do you work so hard?” “My dear lady, with a growing family —” “But why does your family grow?” Their wives wished that too, or perhaps it was the British Empire. But more significant than the answers were the refusals to answer. Very few would reply at all to questions about morality and religion, and such answers as were given were not serious. Questions as to the value of money and power were almost invariably brushed aside, or pressed at extreme risk to the asker. “I’m sure,” said Jill, “that if Sir Harley Tightboots hadn’t been carving the mutton when I asked him about the capitalist system he would have cut my throat. The only reason why we escaped with our lives over and over again is that men are at once so hungry and so chivalrous. They despise us too much to mind what we say.”

“Of course they despise us,” said Eleanor. “At the same time how do you account for this — I made enquiries among the artists. Now, no woman has ever been an artist, has she, Polls?”

“Jane — Austen — Charlotte — Bronte — George — Eliot,” cried Poll, like a man crying muffins in a back street.

“Damn the woman!” someone exclaimed. “What a bore she is!”

“Since Sappho there has been no female of first rate —” Eleanor began, quoting from a weekly newspaper.

“It’s now well known that Sappho was the somewhat lewd invention of Professor Hobkin,” Ruth interrupted.

“Anyhow, there is no reason to suppose that any woman ever has been able to write or ever will be able to write,” Eleanor continued. “And yet, whenever I go among authors they never cease to talk to me about their books. Masterly! I say, or Shakespeare himself! (for one must say something) and I assure you, they believe me.”

“That proves nothing,” said Jane. “They all do it. Only,” she sighed, “it doesn’t seem to help us much. Perhaps we had better examine modern literature next. Liz, it’s your turn.”

Elizabeth rose and said that in order to prosecute her enquiry she had dressed as a man and been taken for a reviewer.

“I have read new books pretty steadily for the past five years,” said she. “Mr. Wells is the most popular living writer; then comes Mr. Arnold Bennett; then Mr. Compton Makenzie; Mr. McKenna and Mr. Walpole may be bracketed together.” She sat down.

“But you’ve told us nothing!” we expostulated. “Or do you mean that these gentlemen have greatly surpassed Jane-Elliot and that English fiction is — where’s that review of yours? Oh, yes, ‘safe in their hands.’”

“Safe, quite safe,” she said, shifting uneasily from foot to foot. “And I’m sure that they give away even more than they receive.”

We were all sure of that. “But,” we pressed her, “do they write good books?”

“Good books?” she said, looking at the ceiling “You must remember,” she began, speaking with extreme rapidity, “that fiction is the mirror of life. And you can’t deny that education is of the highest importance, and that it would be extremely annoying, if you found yourself alone at Brighton late at night, not to know which was the best boarding house to stay at, and suppose it was a dripping Sunday evening — wouldn’t it be nice to go to the Movies?”

“But what has that got to do with it?” we asked.

“Nothing — nothing — nothing whatever,” she replied.

“Well, tell us the truth,” we bade her.

“The truth? But isn’t it wonderful,” she broke off —“Mr. Chitter has written a weekly article for the past thirty years upon love or hot buttered toast and has sent all his sons to Eton —”

“The truth!” we demanded.

“Oh, the truth,” she stammered, “the truth has nothing to do with literature,” and sitting down she refused to say another word.

It all seemed to us very inconclusive.

“Ladies, we must try to sum up the results,” Jane was beginning, when a hum, which had been heard for some time through the open window, drowned her voice.

“War! War! War! Declaration of War!” men were shouting in the street below.

We looked at each other in horror.

“What war?” we cried. “What war?” We remembered, too late, that we had never thought of sending anyone to the House of Commons. We had forgotten all about it. We turned to Poll, who had reached the history shelves in the London Library, and asked her to enlighten us.

“Why,” we cried, “do men go to war?”

“Sometimes for one reason, sometimes for another,” she replied calmly. “In 1760, for example —” The shouts outside drowned her words. “Again in 1797 — in 1804 — It was the Austrians in 1866-1870 was the Franco-Prussian — In 1900 on the other hand —”

“But it’s now 1914!” we cut her short.

“Ah, I don’t know what they’re going to war for now,” she admitted.

* * * *

The war was over and peace was in process of being signed, when I once more found myself with Castalia in the room where our meetings used to be held. We began idly turning over the pages of our old minute books. “Queer,” I mused, “to see what we were thinking five years ago.” “We are agreed,” Castalia quoted, reading over my shoulder, “that it is the object of life to produce good people and good books.” We made no comment upon that. “A good man is at any rate honest, passionate and unworldly.” “What a woman’s language!” I observed. “Oh, dear,” cried Castalia, pushing the book away from her, “what fools we were! It was all Poll’s father’s fault,” she went on. “I believe he did it on purpose — that ridiculous will, I mean, forcing Poll to read all the books in the London Library. If we hadn’t learnt to read,” she said bitterly, “we might still have been bearing children in ignorance and that I believe was the happiest life after all. I know what you’re going to say about war,” she checked me, “and the horror of bearing children to see them killed, but our mothers did it, and their mothers, and their mothers before them. And they didn’t complain. They couldn’t read. I’ve done my best,” she sighed, “to prevent my little girl from learning to read, but what’s the use? I caught Ann only yesterday with a newspaper in her hand and she was beginning to ask me if it was ‘true.’ Next she’ll ask me whether Mr. Lloyd George is a good man, then whether Mr. Arnold Bennett is a good novelist, and finally whether I believe in God. How can I bring my daughter up to believe in nothing?” she demanded.

“Surely you could teach her to believe that a man’s intellect is, and always will be, fundamentally superior to a woman’s?” I suggested. She brightened at this and began to turn over our old minutes again. “Yes,” she said, “think of their discoveries, their mathematics, their science, their philosophy, their scholarship —” and then she began to laugh, “I shall never forget old Hobkin and the hairpin,” she said, and went on reading and laughing and I thought she was quite happy, when suddenly she drew the book from her and burst out, “Oh, Cassandra, why do you torment me? Don’t you know that our belief in man’s intellect is the greatest fallacy of them all?” “What?” I exclaimed. “Ask any journalist, schoolmaster, politician or public house keeper in the land and they will all tell you that men are much cleverer than women.” “As if I doubted it,” she said scornfully. “How could they help it? Haven’t we bred them and fed and kept them in comfort since the beginning of time so that they may be clever even if they’re nothing else? It’s all our doing!” she cried. “We insisted upon having intellect and now we’ve got it. And it’s intellect,” she continued, “that’s at the bottom of it. What could be more charming than a boy before he has begun to cultivate his intellect? He is beautiful to look at; he gives himself no airs; he understands the meaning of art and literature instinctively; he goes about enjoying his life and making other people enjoy theirs. Then they teach him to cultivate his intellect. He becomes a barrister, a civil servant, a general, an author, a professor. Every day he goes to an office. Every year he produces a book. He maintains a whole family by the products of his brain — poor devil! Soon he cannot come into a room without making us all feel uncomfortable; he condescends to every woman he meets, and dares not tell the truth even to his own wife; instead of rejoicing our eyes we have to shut them if we are to take him in our arms. True, they console themselves with stars of all shapes, ribbons of all shades, and incomes of all sizes — but what is to console us? That we shall be able in ten years’ time to spend a weekend at Lahore? Or that the least insect in Japan has a name twice the length of its body? Oh, Cassandra, for Heaven’s sake let us devise a method by which men may bear children! It is our only chance. For unless we provide them with some innocent occupation we shall get neither good people nor good books; we shall perish beneath the fruits of their unbridled activity; and not a human being will survive to know that there once was Shakespeare!”

“It is too late,” I replied. “We cannot provide even for the children that we have.”

“And then you ask me to believe in intellect,” she said.

While we spoke, man were crying hoarsely and wearily in the street, and, listening, we heard that the Treaty of Peace had just been signed. The voices died away. The rain was falling and interfered no doubt with the proper explosion of the fireworks.

“My cook will have bought the Evening News,” said Castalia, “and Ann will be spelling it out over her tea. I must go home.”

“It’s no good — not a bit of good,” I said. “Once she knows how to read there’s only one thing you can teach her to believe in — and that is herself.”

“Well, that would be a change,” sighed Castalia.

So we swept up the papers of our Society, and, though Ann was playing with her doll very happily, we solemnly made her a present of the lot and told her we had chosen her to be President of the Society of the future — upon which she burst into tears, poor little girl.

Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf

2. A Society

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Monday or Tuesday, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

De kinderen gingen hem achterna en bleven hem sarren. Ze hadden altijd angst voor hem gehad. Weerloos was hij nu aan hen overgeleverd. Niemand deed een poging hen te bedaren. Ook Kaffa niet, hoewel hij walgde van het tafereel.

De kinderen gingen hem achterna en bleven hem sarren. Ze hadden altijd angst voor hem gehad. Weerloos was hij nu aan hen overgeleverd. Niemand deed een poging hen te bedaren. Ook Kaffa niet, hoewel hij walgde van het tafereel.

Vol weerzin hield hij het lemmet van het mes nogmaals onder de koude straal. Het water spoot bruisend uit de pomphals, of het kookte. Kaffa merkte dat het mes trilde als hij het in zijn linkerhand droeg. De hand waarmee hij had gegooid. Het verwonderde hem. Zijn linkerhand was altijd sterk en zeker geweest. Hij nam het mes over in de rechter. Die was rustiger. Hij nam het weer over in de linker. Die hand trilde zo heftig dat hij het mes direct weer moest overgeven aan de rechterhand. Hij vloekte. Hij kon niet verdragen dat de zenuwen de baas waren over zijn lijf. De slager kwam het plein op zeulen op zijn bakfiets, waarin enkele biggen gilden. Hijgend plaatste hij de bak naast de pomp. Hij transpireerde hevig en stonk naar stallen. `Je wast je mes?’ vroeg hij, verbaasd over zichzelf omdat hij de gek aansprak. `Ja, ik was mijn mes’, zei Kaffa, terwijl hij het trillen in zijn linkerhand voelde en vaag het geouwehoer van Jacob Ramesz over zijn worp met het mes opving. Wat hem bijna in woede deed uitbarsten. Godverdomme. Waar bemoeide die ouwe vent zich mee? `Ik was mijn mes’, zei hij nog eens. `Dat verrekte bloed kleeft eraan als teer.’ Azurri trok zijn hemd uit en waste kop en bovenlijf onder de koele straal van de pomp. Hij pompte een emmer vol en gooide hem over de varkens, die van het koude water schrokken en weer gilden. Waarschijnlijk hadden ze in de paar weken dat ze leefden nooit water gezien. Nu pas zag de slager hoe Elysee tussen de gebouwen van Chile door hinkte en om zijn ezel riep, al was het dier in geen velden of wegen te bekennen. En de joelende kinderen die de man naliepen. Er kwam een minachtende grijns rond de mond van de slager. Angela holde naar Kaffa. Dankbaar omdat hij haar uit de klauwen van Elysee had gehaald, sprong ze tegen hem op en bleef als een klit om zijn hals hangen. Hij drukte haar tegen zich aan. Voelde haar natte lijf door zijn kleren heen. Ze duwde haar wang in zijn nek, ademde in zijn gezicht. Hij zoende haar haren, proefde haar zoute tranen. Ze huilde geluidloos. Lieve, lieve vrouw. Hij streelde haar warme lijf, haar dijen. `Lekker warm dier’, lachte hij en hij beet in haar oor. Hij zag de blik van Azurri, die zich gruwelijk ergerde aan het gedrag van zijn dochter. Net toen hij tegen het meisje wilde uitvallen, fluisterde zijn vrouw hem wat in het oor.

Waarschijnlijk over het voorval met de waarzegger en de manier waarop Kaffa het meisje had bevrijd. Het leek de slager niet tot betere gevoelens voor Kaffa aan te zetten, maar hij hield zich koest en liep mokkend terug naar zijn bakfiets vol varkens. Om zijn gevoelens te luchten moesten de beesten, die nergens schuld aan hadden, het ontgelden. Met zijn blote vuisten sloeg hij de dieren waar hij ze raken kon. Op kop, rug en nek. De biggen, die niets van deze afstraffing begrepen, begonnen wild te krijsen en sprongen tegen de schotten van de bak omhoog. Geschrokken van het lawaai zette Kaffa het meisje op de grond. Hij zag dat er kort gras tegen de verdrukking in onder het granieten pompbed uitgroeide, een klein stukje maar, want verderop verstikte het in de modder en de door zeik verzuurde grond. Hij veegde het lemmet van zijn mes droog aan de pijp van zijn broek, zette het aan in zijn handpalm en voelde dat het nog scherper kon. Hij wette het secuur op de gladde rand van de spoelbak. Kleine gensters spoten in het rond. `Het is mijn beste mes’, zei Kaffa verontschuldigend tegen Azurri. `Het ligt goed in de hand. Het treft precies waar ik het hebben wil.’ Kaffa liep terug naar zijn plaats. Veegde met een voet de grenzen van de oude landen uit. Tekende met de punt van het mes een cirkel. Sneed de cirkel in twee gelijke delen. Legde in elk land een lucifer. Zo had elk land zijn eigen koning. De slager, die zag dat Kaffa met zijn spel wilde beginnen, vergat zijn varkens, veegde het zweet van zijn voorhoofd, schurkte zijn rug tegen de opstand van de pomp en liep naar Kaffa. Zonder te vragen of hij mocht meedoen spuwde hij in zijn handen en hurkte tegenover Kaffa neer. Nu had hij eindelijk de kans om die gek eens te laten zien wie de werkelijke kampioen van het dorp was.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (33)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Geschrokken keek hij op. Zag dat de buizerd in paniek tussen de dichte takken rond de kruin van de meidoorn fladderde, veel zachte veertjes verliezend die langzaam naar beneden dwarrelden. Toen pas zag hij Elysee bij de spoelbak.

Geschrokken keek hij op. Zag dat de buizerd in paniek tussen de dichte takken rond de kruin van de meidoorn fladderde, veel zachte veertjes verliezend die langzaam naar beneden dwarrelden. Toen pas zag hij Elysee bij de spoelbak.

Met zijn rechterhand hield hij Angela vast. Met de andere streelde hij haar dunne lijf. De andere kinderen zaten verstijfd van schrik in de spoelbak, hun ogen open, alsof ze waren betoverd. Zonder er verder over na te denken mikte Kaffa nauwkeurig met zijn linkerhand. Het mes trof de waarzegger in zijn poot. De man leek af te breken en zakte door zijn knieën. Wilde schreeuwen of vloeken of God weet wat, zijn mond ging tenminste open en dicht, maar er kwam alleen een vuile fontein van afgevreten woorden naar buiten. Angela sprong van de spoelbak, rende luidkeels gillend langs de geschrokken kraaien en de zieke jongen naar haar moeder, die naar buiten kwam hollen, en sprong haar in de armen. De katachtige heks Josanna had zich als eerste hersteld van de schrik en zakte languit in het water, kopje-onder. Om aandacht te trekken wilde ze laten zien dat het gebeuren haar verder koud liet. Wist zo’n kind veel! Opgehitst door de sensatie renden de kraaien kakelend rond het bed. Op het rode scherm voor zijn ogen zag de jongen de zwarte schaduwen op en neer dansen, wat hem deed schrikken. Hij sloeg een lange ijle kreet uit, waar zelfs opoe Ramesz een rilling van over de rug liep, zodat ze in haar stoel trilde en haar stoofje omviel, as en stof rond haar strooiend. Céleste liep tot onder de meidoorn. Ze hoorde de waarzegger janken van pijn en wilde hem helpen, maar iets in haar belette dat, al was het misschien alleen maar haar afkeer van hem.

Alleen de kaarters waren onverstoorbaar. Ze hadden niet eens bewondering voor Kaffa’s feilloze worp. In tegenstelling tot Jacob Ramesz, die enthousiast van zijn ene been op het andere hinkte en in de dovekwarteloren van opoe schreeuwde hoe goed Kaffa gemikt had. Opoe knikte maar, omdat ze bekend geluid opving. Jacob kon ouwehoeren wat hij wilde, opoe zou hem toch nooit meer tegenspreken. Een roofvogel, dacht Kaffa terwijl hij naar de waarzegger keek. Hij lachte met zijn hele gezicht. Godverdomme, een roofvogel verdiende niet beter. Kaffa trapte zijn hakken diep in het zand, om te blijven staan waar hij stond. Hij wist dat hij zich niet zou kunnen beheersen, dat hij Elysee zou afmaken als hij naar hem toe zou gaan. Het mes was in het been blijven steken. Vol afschuw trok Elysee het eruit. Bloed stroomde uit de wond. Op handen en knieën bereikte hij de ezel, die nog steeds aan de liguster in de caféhof vastgebonden stond, maakte hem los en kroop schrijlings op de rug van het dier. Traag en vol weerzin kwam de ezel in beweging. Schommelde het plein af op zijn danspasjes makende scheve poten, de man op zijn rug door elkaar rammelend als een zak knoken. Kaffa zag dat Josanna nog onder de waterspiegel lag. Roerloos, met open ogen. Hij dacht dat dit vreemde spelletje slecht kon aflopen voor het kind. Liep naar de spoelbak, trok haar uit het water en zette het wild om zich heen slaande schepsel op de grond. Hij begreep de woede van het kind niet. Zag dat er scheurtjes door het graniet van de spoelbak liepen, zo dun als haartjes. `Het is niets’, riep hij naar de vrouw die met Angela in haar armen naar hen keek. `Helemaal niets!’ Met afschuw zag hij het bloed aan het mes, dat nog in het zand lag. Raapte het op en keek nauwkeurig of het niet beschadigd was. Gelukkig had het niets geleden. Hij hield het lemmet in de waterstraal van de pomp om het bloed eraf te spoelen. Het mes tegen het licht houdend dat door de meidoorn scheen, keek hij of het schoon was. Maar het schijnsel van de meidoorn gaf alles de kleur van roze crèpepapier en roest. Kaffa zag dat Elysee zijn rijdier liet stoppen door hem met de vlakke hand op de kop te slaan. De waarzegger gleed van de ezel, ging met zijn rug tegen de muur van Chile zitten en rolde de pijp van zijn broek op. De kleine meisjes Azurri, bekomen van de schrik, waren achter de ezel aan gelopen. Om te laten zien dat ze geen angst meer hadden, raapten ze stenen op en gooiden die naar de waarzegger en zijn rijdier. De ezel, die meerdere malen werd getroffen, begreep dat het onveilig werd. Hij zette het op een lopen, zo vlug alsof hij door een horzel in zijn aars was gestoken. Zijn scheve poten ontwikkelden een ongekende vaart, hoewel ze soms onder hem uit sloegen, alsof hij over groene zeep liep. Zelfs de waarzegger liet zijn mond openvallen van verbazing toen hij het zag. Hij balde zijn vuisten naar de kinderen, maar die lachten hem uit. Elysee kon zich toch niet verweren. Hij kroop overeind. Op één been hinkend, het andere achter zich aan zeulend, verdween hij tussen de gebouwen van Chiles Plaats.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (32)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Hans Christian Andersen

(1805—1875)

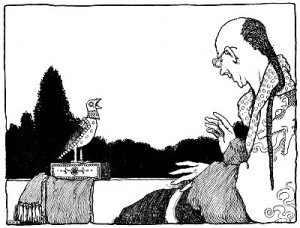

The nightingale

In China, you know, the emperor is a Chinese, and all those about him are Chinamen also. The story I am going t tell you happened a great many years ago, so it is well to hear it now before it is forgotten. The emperor’s palac was the most beautiful in the world. It was built entirely of porcelain, and very costly, but so delicate and brittle tha whoever touched it was obliged to be careful. In the garden could be seen the most singular flowers, with prett silver bells tied to them, which tinkled so that every one who passed could not help noticing the flowers.

Indeed everything in the emperor’s garden was remarkable, and it extended so far that the gardener himself did not kno where it ended. Those who travelled beyond its limits knew that there was a noble forest, with lofty trees, slopin down to the deep blue sea, and the great ships sailed under the shadow of its branches. In one of these trees live a nightingale, who sang so beautifully that even the poor fishermen, who had so many other things to do, woul stop and listen. Sometimes, when they went at night to spread their nets, they would hear her sing, and say, “Oh, i not that beautiful?” But when they returned to their fishing, they forgot the bird until the next night. Then they woul hear it again, and exclaim “Oh, how beautiful is the nightingale’s song!

Travellers from every country in the world came to the city of the emperor, which they admired very much, as well as the palace and gardens; but when they heard the nightingale, they all declared it to be the best of all.

And the travellers, on their return home, related what they had seen; and learned men wrote books, containing descriptions of the town, the palace, and the gardens; but they did not forget the nightingale, which was really the greatest wonder. And those who could write poetry composed beautiful verses about the nightingale, who lived in a forest near the deep sea.

The books travelled all over the world, and some of them came into the hands of the emperor; and he sat in his golden chair, and, as he read, he nodded his approval every moment, for it pleased him to find such a beautiful description of his city, his palace, and his gardens. But when he came to the words, “the nightingale is the most beautiful of all,” he exclaimed:

“What is this? I know nothing of any nightingale. Is there such a bird in my empire? and even in my garden? I have never heard of it. Something, it appears, may be learnt from books.”

Then he called one of his lords-in-waiting, who was so high-bred, that when any in an inferior rank to himself spoke to him, or asked him a question, he would answer, “Pooh,” which means nothing.

“There is a very wonderful bird mentioned here, called a nightingale,” said the emperor; “they say it is the best thing in my large kingdom. Why have I not been told of it?”

“I have never heard the name,” replied the cavalier; “she has not been presented at court.”

“It is my pleasure that she shall appear this evening.” said the emperor; “the whole world knows what I possess better than I do myself.”

“I have never heard of her,” said the cavalier; “yet I will endeavor to find her.”

But where was the nightingale to be found? The nobleman went up stairs and down, through halls and passages; yet none of those whom he met had heard of the bird. So he returned to the emperor, and said that it must be a fable, invented by those who had written the book. “Your imperial majesty,” said he, “cannot believe everything contained in books; sometimes they are only fiction, or what is called the black art.”

“But the book in which I have read this account,” said the emperor, “was sent to me by the great and mighty emperor of Japan, and therefore it cannot contain a falsehood. I will hear the nightingale, she must be here this evening; she has my highest favor; and if she does not come, the whole court shall be trampled upon after supper is ended.”

“Tsing-pe!” cried the lord-in-waiting, and again he ran up and down stairs, through all the halls and corridors; and half the court ran with him, for they did not like the idea of being trampled upon. There was a great inquiry about this wonderful nightingale, whom all the world knew, but who was unknown to the court.

At last they met with a poor little girl in the kitchen, who said, “Oh, yes, I know the nightingale quite well; indeed, she can sing. Every evening I have permission to take home to my poor sick mother the scraps from the table; she lives down by the sea-shore, and as I come back I feel tired, and I sit down in the wood to rest, and listen to the nightingale’s song. Then the tears come into my eyes, and it is just as if my mother kissed me.”

“Little maiden,” said the lord-in-waiting, “I will obtain for you constant employment in the kitchen, and you shall have permission to see the emperor dine, if you will lead us to the nightingale; for she is invited for this evening to the palace.”

So she went into the wood where the nightingale sang, and half the court followed her. As they went along, a cow began lowing.

“Oh,” said a young courtier, “now we have found her; what wonderful power for such a small creature; I have certainly heard it before.”

“No, that is only a cow lowing,” said the little girl; “we are a long way from the place yet.”

Then some frogs began to croak in the marsh.

“Beautiful,” said the young courtier again. “Now I hear it, tinkling like little church bells.”

“No, those are frogs,” said the little maiden; “but I think we shall soon hear her now:”

And presently the nightingale began to sing.

“Hark, hark! there she is,” said the girl, “and there she sits,” she added, pointing to a little gray bird who was perched on a bough.

“Is it possible?” said the lord-in-waiting, “I never imagined it would be a little, plain, simple thing like that. She has certainly changed color at seeing so many grand people around her.”

“Little nightingale,” cried the girl, raising her voice, “our most gracious emperor wishes you to sing before him.”

“With the greatest pleasure,” said the nightingale, and began to sing most delightfully.

“It sounds like tiny glass bells,” said the lord-in-waiting, “and see how her little throat works. It is surprising that we have never heard this before; she will be a great success at court.”

“Shall I sing once more before the emperor?” asked the nightingale, who thought he was present.

“My excellent little nightingale,” said the courtier, “I have the great pleasure of inviting you to a court festival this evening, where you will gain imperial favor by your charming song.”

“My song sounds best in the green wood,” said the bird; but still she came willingly when she heard the emperor’s wish.

The palace was elegantly decorated for the occasion. The walls and floors of porcelain glittered in the light of a thousand lamps. Beautiful flowers, round which little bells were tied, stood in the corridors: what with the running to and fro and the draught, these bells tinkled so loudly that no one could speak to be heard.

In the centre of the great hall, a golden perch had been fixed for the nightingale to sit on. The whole court was present, and the little kitchen-maid had received permission to stand by the door. She was not installed as a real court cook. All were in full dress, and every eye was turned to the little gray bird when the emperor nodded to her to begin.

The nightingale sang so sweetly that the tears came into the emperor’s eyes, and then rolled down his cheeks, as her song became still more touching and went to every one’s heart. The emperor was so delighted that he declared the nightingale should have his gold slipper to wear round her neck, but she declined the honor with thanks: she had been sufficiently rewarded already.

“I have seen tears in an emperor’s eyes,” she said, “that is my richest reward. An emperor’s tears have wonderful power, and are quite sufficient honor for me;” and then she sang again more enchantingly than ever.

“That singing is a lovely gift;” said the ladies of the court to each other; and then they took water in their mouths to make them utter the gurgling sounds of the nightingale when they spoke to any one, so thay they might fancy themselves nightingales. And the footmen and chambermaids also expressed their satisfaction, which is saying a great deal, for they are very difficult to please. In fact the nightingale’s visit was most successful.

She was now to remain at court, to have her own cage, with liberty to go out twice a day, and once during the night. Twelve servants were appointed to attend her on these occasions, who each held her by a silken string fastened to her leg. There was certainly not much pleasure in this kind of flying.

The whole city spoke of the wonderful bird, and when two people met, one said “nightin,” and the other said “gale,” and they understood what was meant, for nothing else was talked of. Eleven peddlers’ children were named after her, but not of them could sing a note.

One day the emperor received a large packet on which was written “The Nightingale.”

“Here is no doubt a new book about our celebrated bird,” said the emperor. But instead of a book, it was a work of art contained in a casket, an artificial nightingale made to look like a living one, and covered all over with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. As soon as the artificial bird was wound up, it could sing like the real one, and could move its tail up and down, which sparkled with silver and gold. Round its neck hung a piece of ribbon, on which was written “The Emperor of China’s nightingale is poor compared with that of the Emperor of Japan’s.”

“This is very beautiful,” exclaimed all who saw it, and he who had brought the artificial bird received the title of “Imperial nightingale-bringer-in-chief.”

“Now they must sing together,” said the court, “and what a duet it will be.”

But they did not get on well, for the real nightingale sang in its own natural way, but the artificial bird sang only waltzes. “That is not a fault,” said the music-master, “it is quite perfect to my taste,” so then it had to sing alone, and was as successful as the real bird; besides, it was so much prettier to look at, for it sparkled like bracelets and breast-pins.

Thirty three times did it sing the same tunes without being tired; the people would gladly have heard it again, but the emperor said the living nightingale ought to sing something. But where was she? No one had noticed her when she flew out at the open window, back to her own green woods.

“What strange conduct,” said the emperor, when her flight had been discovered; and all the courtiers blamed her, and said she was a very ungrateful creature. “But we have the best bird after all,” said one, and then they would have the bird sing again, although it was the thirty-fourth time they had listened to the same piece, and even then they had not learnt it, for it was rather difficult. But the music-master praised the bird in the highest degree, and even asserted that it was better than a real nightingale, not only in its dress and the beautiful diamonds, but also in its musical power.

“For you must perceive, my chief lord and emperor, that with a real nightingale we can never tell what is going to be sung, but with this bird everything is settled. It can be opened and explained, so that people may understand how the waltzes are formed, and why one note follows upon another.”

“This is exactly what we think,” they all replied, and then the music-master received permission to exhibit the bird to the people on the following Sunday, and the emperor commanded that they should be present to hear it sing. When they heard it they were like people intoxicated; however it must have been with drinking tea, which is quite a Chinese custom. They all said “Oh!” and held up their forefingers and nodded, but a poor fisherman, who had heard the real nightingale, said, “it sounds prettily enough, and the melodies are all alike; yet there seems something wanting, I cannot exactly tell what.”

And after this the real nightingale was banished from the empire.

The artificial bird was placed on a silk cushion close to the emperor’s bed. The presents of gold and precious stones which had been received with it were round the bird, and it was now advanced to the title of “Little Imperial Toilet Singer,” and to the rank of No. 1 on the left hand; for the emperor considered the left side, on which the heart lies, as the most noble, and the heart of an emperor is in the same place as that of other people. The music-master wrote a work, in twenty-five volumes, about the artificial bird, which was very learned and very long, and full of the most difficult Chinese words; yet all the people said they had read it, and understood it, for fear of being thought stupid and having their bodies trampled upon.

So a year passed, and the emperor, the court, and all the other Chinese knew every little turn in the artificial bird’s song; and for that same reason it pleased them better. They could sing with the bird, which they often did. The street-boys sang, “Zi-zi-zi, cluck, cluck, cluck,” and the emperor himself could sing it also. It was really most amusing.

One evening, when the artificial bird was singing its best, and the emperor lay in bed listening to it, something inside the bird sounded “whizz.” Then a spring cracked. “Whir-r-r-r” went all the wheels, running round, and then the music stopped.

The emperor immediately sprang out of bed, and called for his physician; but what could he do? Then they sent for a watchmaker; and, after a great deal of talking and examination, the bird was put into something like order; but he said that it must be used very carefully, as the barrels were worn, and it would be impossible to put in new ones without injuring the music. Now there was great sorrow, as the bird could only be allowed to play once a year; and even that was dangerous for the works inside it. Then the music-master made a little speech, full of hard words, and declared that the bird was as good as ever; and, of course no one contradicted him.

Five years passed, and then a real grief came upon the land. The Chinese really were fond of their emperor, and he now lay so ill that he was not expected to live. Already a new emperor had been chosen and the people who stood in the street asked the lord-in-waiting how the old emperor was.

But he only said, “Pooh!” and shook his head.

Cold and pale lay the emperor in his royal bed; the whole court thought he was dead, and every one ran away to pay homage to his successor. The chamberlains went out to have a talk on the matter, and the ladies’-maids invited company to take coffee. Cloth had been laid down on the halls and passages, so that not a footstep should be heard, and all was silent and still. But the emperor was not yet dead, although he lay white and stiff on his gorgeous bed, with the long velvet curtains and heavy gold tassels. A window stood open, and the moon shone in upon the emperor and the artificial bird.

The poor emperor, finding he could scarcely breathe with a strange weight on his chest, opened his eyes, and saw Death sitting there. He had put on the emperor’s golden crown, and held in one hand his sword of state, and in the other his beautiful banner. All around the bed and peeping through the long velvet curtains, were a number of strange heads, some very ugly, and others lovely and gentle-looking. These were the emperor’s good and bad deeds, which stared him in the face now Death sat at his heart.

“Do you remember this?” “Do you recollect that?” they asked one after another, thus bringing to his remembrance circumstances that made the perspiration stand on his brow.

“I know nothing about it,” said the emperor. “Music! music!” he cried; “the large Chinese drum! that I may not hear what they say.”

But they still went on, and Death nodded like a Chinaman to all they said.

“Music! music!” shouted the emperor. “You little precious golden bird, sing, pray sing! I have given you gold and costly presents; I have even hung my golden slipper round your neck. Sing! sing!”

But the bird remained silent. There was no one to wind it up, and therefore it could not sing a note. Death continued to stare at the emperor with his cold, hollow eyes, and the room was fearfully still.

Suddenly there came through the open window the sound of sweet music. Outside, on the bough of a tree, sat the living nightingale. She had heard of the emperor’s illness, and was therefore come to sing to him of hope and trust. And as she sung, the shadows grew paler and paler; the blood in the emperor’s veins flowed more rapidly, and gave life to his weak limbs; and even Death himself listened, and said, “Go on, little nightingale, go on.”

“Then will you give me the beautiful golden sword and that rich banner? and will you give me the emperor’s crown?” said the bird.

So Death gave up each of these treasures for a song; and the nightingale continued her singing. She sung of the quiet churchyard, where the white roses grow, where the elder-tree wafts its perfume on the breeze, and the fresh, sweet grass is moistened by the mourners’ tears. Then Death longed to go and see his garden, and floated out through the window in the form of a cold, white mist.

“Thanks, thanks, you heavenly little bird. I know you well. I banished you from my kingdom once, and yet you have charmed away the evil faces from my bed, and banished Death from my heart, with your sweet song. How can I reward you?”

“You have already rewarded me,” said the nightingale. “I shall never forget that I drew tears from your eyes the first time I sang to you. These are the jewels that rejoice a singer’s heart. But now sleep, and grow strong and well again. I will sing to you again.”

And as she sung, the emperor fell into a sweet sleep; and how mild and refreshing that slumber was!

When he awoke, strengthened and restored, the sun shone brightly through the window; but not one of his servants had returned– they all believed he was dead; only the nightingale still sat beside him, and sang.

“You must always remain with me,” said the emperor. “You shall sing only when it pleases you; and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.”

“No; do not do that,” replied the nightingale; “the bird did very well as long as it could. Keep it here still. I cannot live in the palace, and build my nest; but let me come when I like. I will sit on a bough outside your window, in the evening, and sing to you, so that you may be happy, and have thoughts full of joy. I will sing to you of those who are happy, and those who suffer; of the good and the evil, who are hidden around you. The little singing bird flies far from you and your court to the home of the fisherman and the peasant’s cot. I love your heart better than your crown; and yet something holy lingers round that also. I will come, I will sing to you; but you must promise me one thing.”

“Everything,” said the emperor, who, having dressed himself in his imperial robes, stood with the hand that held the heavy golden sword pressed to his heart.

“I only ask one thing,” she replied; “let no one know that you have a little bird who tells you everything. It will be best to conceal it.”

So saying, the nightingale flew away.

The servants now came in to look after the dead emperor; when, lo! there he stood, and, to their astonishment, said, “Good morning.”

END

Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Het meisje voelde Kaffa’s blik. Ze lachte naar hem. Ze lachte open. Niet als een meisje dat in de gaten had dat er een vent naar haar keek. Een lekker dier. Een kind nog, ook al had ze reeds het wezen van een vrouw, zacht en warm.

Het meisje voelde Kaffa’s blik. Ze lachte naar hem. Ze lachte open. Niet als een meisje dat in de gaten had dat er een vent naar haar keek. Een lekker dier. Een kind nog, ook al had ze reeds het wezen van een vrouw, zacht en warm.

Ze holde naar hem toe met handen vol water en gooide hem plagerig nat. Dat deed goed met deze hitte. Die verrekte zon leek meer dan dolgedraaid. En dat nog wel in een tijd van het jaar dat hij het kalmer aan hoorde te doen. Angela kwam zo dicht bij Kaffa dat hij haar natte huid rook. De geur van groen fruit en zout. Haar kleren plakten aan haar lijf, zodat haar vormen goed te zien waren. Met haar lange benen had ze het wezen van een hert. Even raakte ze hem aan. Als door een vlam getroffen keek hij op. Gelukkig had niemand het gezien. Ze liep terug naar de andere kinderen. Hij had haar liever dicht bij zich gehouden, maar hij wist dat hij zijn opwinding niet zou kunnen verbergen. Hij zou haar willen aanraken, haar huid willen voelen. Het meisje liet een nat spoor achter, tot langs de kraaien, die op hun knieën rond het bed zaten en weer de een of andere litanie aanhieven. Een klaaglijk gebed dat dreinerig uit hun bekken klonk en dat als smeekbede tot de gelukzalige kluizenaar was bedoeld. De kraaien beloofden dat ze voor hem, als hij zijn best maar wilde doen en de jongen in leven hield, door het stof naar Rome zouden kruipen. Daar zouden ze door hun getuigenis zijn heiligverklaring als belijder kunnen regelen. Compleet met kerkelijke feestdag, aflaten en genademiddelen. Zo’n wonder zou goed zijn voor iedereen. Het dorp zou een behoorlijke handel kunnen beleven in relikwieën en aftreksels daarvan. Want behalve de botten van de gelukzalige waren er in Solde nog de zweep waarmee hij zich dagelijks kastijdde, de dekens van zijn bed, de stenen van zijn krot, de grond van zijn tuin, de lucht waarin hij ademde en de wolken waartussen hij ten hemel was gestegen. Verder kon men zijn portret drukken op prentjes, vaasjes en kerkboeken. En op de wikkels van stukken zeep die de heilige zelf nooit zou hebben gebruikt. Het verhaal wilde dat hij zo kuis was geweest dat hij nooit zijn kont en kloten had gewassen.

Om de gelukzalige nog gunstiger te stemmen onderhielden de kraaien een koeriersdienst tussen kerk en bed. Lieten een dozijn kaarsen branden voor de foto van de nog niet heilig verklaarde en daarom nog niet in gips of cement gegoten heremiet. Niet de dikste kaarsen, maar toch twaalf. En niet allemaal tegelijk. Tenslotte zou de man eerst heilig moeten zijn vooraleer men er een hoop geld tegenaan zou willen gooien. De pastoor was helemaal niet blij met het vrome gedrag van de kraaien. Het hield hem uit zijn dagelijkse doen. Rusteloos beende hij door de kerk. Liep verschillende malen naar buiten om naar het zieke kind te kijken, bekeek het aandachtig en begreep dat alle hulp te laat zou komen, zelfs die van de heremiet. Ook de vier kaarters, die al aan hun zoveelste glas jenever bezig waren, was het duidelijk dat de kluizenaar het liet afweten. Dat verbaasde hen eigenlijk niks. Als kind hadden ze hem nog goed gekend. Ze hadden zich altijd al verbaasd over de vreemde man die zich het lijf tot bloedens toe kastijdde om aan alle verzoekingen, zoals kaarten en zuipen, te ontkomen. Onder het spel vloekten de vier luid. Het was tot in de kerk en ver daarbuiten te horen. Dat hielp het effect van de litanie en de brandende kaarsen bij voorbaat naar de bliksem. De kraaien, die het vloeken hoorden, begrepen dat ze nutteloos werk verrichtten en staakten hun pogingen om de jongen gezond te bidden. Hun medelijden loste op in een druk gekwetter. Er kwam zelfs een lach rond hun zure monden toen ze zagen hoe de oude Jacob Ramesz rammel kreeg met de pook. Jacob probeerde het kolenstoofje onder opoes voeten leeg te halen, maar opoe begreep niet meer zo goed wat die Jacob daar allemaal aan haar voeten deed. Omdat ze hem misschien helemaal niet meer kende en ook omdat ze dat pookje toevallig in haar handen hield, sloeg ze er maar op los. Woedend om zoveel ondank schopte Jacob tegen de poten van de stoel zodat het oude wijfje bijna omverviel. Kaffa speelde verder, zonder de minste aandacht voor de gebeurtenissen op het plein. Het zand onder de meidoorn beviel hem best. Een mes viel er niet in om. Het was niet te nat, niet te droog. Het was echter niet zo goed als het gewalste metselzand van het kerkpad, dat geroemd werd om zijn uitstekende kwaliteit. Maar Kaffa hield zich daar nooit op. Hij kwam niet in de kerk. Hij moest van de pastoor en zijn hele beweging niks hebben. Niet omdat hij een hekel aan de man had, welnee, enkel omdat hij dat gebouw met zijn hoge muren haatte. Voor zijn gevoel was het een gevangenis. Hij pakte het mes met de linkerhand en wierp het krachtig in het land van de rechter. Diens koning kon oprotten. Met de punt van het mes wipte Kaffa de koning van de rechterhand in het hem resterende land. Wierp het mes hoog in de lucht en ving het op. Wilde het mes opnieuw in het land van de rechterhand werpen, toen hij plotseling Angela hard en schel hoorde gillen.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (31)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Allure noch schijngestalte / Randjes

Ik ben zielig, zo zielig.

Ik haat de deuren die te hard dichtvallen.

Ik haat de randjes rond mijn nagels.

Ik haat de tegeltjes in mijn badkamer omdat ze niet naar boven of onder gaan.

Ik haat al mijn beslissingen, maar de beslissing om mijzelf te gaan vinden in Cambodja nog het meest.

Ik ben een mislukkeling en ik kan niks.

Ik heb nog altijd randjes rond mijn nagels

Ik haat de regen die niet doorzet en de mislukte kit in de zijkant van mijn ijskast.

Alles mislukt. Misluk!

Ik haat de herinnering aan het nergens bij horen.

Ik haat dat ik zelfs in de mooiste verfabeling van mijn herinnering toch geen stukje ontbijtkoek krijg en word uitgelachen.

Ik ben zielig.

Ik kan niet eens ritmisch haten, zoals de harmonie van de maquette voor een rijk van een dictator.

Ik kan niet eens de vetkwabben van de hoerige caissière, met blonde pluk in ’t haar, haten.

Hoe zij aan haar blonde pluk sabbelt en mijn pak mergpijpjes piept.

Ik bijt de velletjes rond mijn nagels en ik zwabber op mijn stoel.

Alles zou kunnen en ik doe niets.

Ik haat want ik weet alles beter, dat zei mijn net niet echt labiele tante tegen mij.

De tante waarbij ik schaamhaar voor het eerst goed zag. Ze had een donkere bos die ik later ook zou krijgen. Zij las mij voor en ik wist het beter.

Beter dan de meneren op het nieuws die altijd alles weten.

Zij kunnen tenminste niets vinden. Ik vind alles.

Ik pulk en scheur de vellen rond mijn nagels en ik haat de ademloze race van ik tegen ik.

Mama, je spijt me.

Ik ben zielig.

Esther Porcelijn, 2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Elysee bond de ezel aan een van de struiken in de caféhof. Hij groette Kaffa joviaal, alsof hij hem in dagen niet had gezien. Kaffa groette niet terug. Hij had al zijn aandacht nodig bij de twee landen. `Ik wil een spelletje met je doen’, riep Elysee. Kaffa schudde beslist van nee.

Elysee bond de ezel aan een van de struiken in de caféhof. Hij groette Kaffa joviaal, alsof hij hem in dagen niet had gezien. Kaffa groette niet terug. Hij had al zijn aandacht nodig bij de twee landen. `Ik wil een spelletje met je doen’, riep Elysee. Kaffa schudde beslist van nee.

Hij had geen behoefte aan gezelschap. Hij speelde alleen verder, nam het mes in zijn linkerhand en gooide het vol kracht in een van de landen. De waarzegger hield dreigend zijn vuist omhoog, maar Kaffa deed of hij het niet merkte. Terwijl hij zag dat er water uit de kleren van Elysee op de grond drupte, sneed hij een stuk van het land van de rechterhand af. Nam het mes over in de rechterhand en wierp het met kracht in het land van de linker. Woedend liep Elysee naar het café. De hond gromde en trok zich terug achter het buffet. Nog druipend van het water streek de man aan een tafel neer, zijn armen breeduit over het blad. Zonder zich te bekommeren om de blikken van de vier kaarters die op hem waren gericht, alsof ze hem wilden vertellen dat hij daar niet hoorde. Zoals gewoonlijk trok hij zijn poot in, trommelde met zijn vuisten op tafel en riep luid om jenever. Céleste had de woorden op haar lippen om hem te vragen naar wat hij daarstraks voor haar verborgen had gehouden. Ze deed het niet. Ze wist dat elke toenadering een kleine triomf voor hem zou zijn. Waarschijnlijk zou hij toch niets zeggen en alleen maar meer genieten van datgene wat hij over haar toekomst meende te weten. Hij lachte tegen haar, alsof er in de schuur van Chile niets gebeurd was. Neuriede wat voor zich uit, af en toe woorden zingend waarvan niemand wat begreep. Een deuntje op het ritme van zijn trommelende vingers. Céleste bracht hem jenever. Hij nam het glas aan en goot de drank klokkend door zijn keel. Goede jenever. Aardappeljenever liet hij zich niet meer opdringen. De kastelein had dikwijls geprobeerd hem het goedkoopste bocht dat de streek zelf voortbracht, voor te zetten. Vandaag zoop Elysee wat hij zuipen wilde. Geld of geen geld. En de kastelein, die hem vanuit de keukendeur stond te beloeren, moest maar oppassen. Die vent had hem al te vaak belazerd. Die kon zo een klap voor zijn hersens krijgen als hij dat wilde.

Elysee stond op en begaf zich naar de tafel van de vier kaarters. Joviaal klopte hij de vier oudjes op de schouders en lachte breed. `Zo, ouwe kerels,’ zei hij met wat dreiging in zijn stem, `laat me jullie handen maar eens zien, dan kan ik je de toekomst voorspellen.’ `Je houdt ons op met kaarten. Aan onze toekomst hebben we niks’, zei een van de vier. `We zijn er te oud voor. Je zou ons hooguit kunnen vertellen wie van ons dit spelletje wint, maar zelfs dat hoeven we niet te weten. Dan is de lol eraf.’ `Je bent een lul van een waarzegger’, zei een ander. `Weken geleden heb je regen voorspeld, maar het is nog steeds droog.’ `Vanavond gaat het regenen’, zei Elysee beslist. `Hier man, drink een borrel, ik hoop dat je gelijk hebt, en dan wegwezen’, zei de derde. Elysee dronk de borrel, hield de drank een ogenblik in zijn mond en spoog hem toen over de hoofden van de kaarters uit. Die waren te verbaasd om iets te doen. Ze bleven voor joker zitten, terwijl de waarzegger naar zijn tafeltje terugging en voor zich uit neuriede. Hij deed of hij niet zag dat de kastelein een paar stappen verder het café was ingekomen, zijn vuisten balde en naar de waarzegger keek alsof hij hem naar buiten wilde slaan. Buiten onder de meidoorn merkte Kaffa niets van de onheilspellende sfeer in de kroeg. Hij speelde ongestoord. Liet zich niet afleiden, ook al had hij goed in de gaten dat de oude Jacob Ramesz, die als een soldaat achter de stoel van de kleumende opoe stond, naar hem keek. Met vragende ogen, als een kind dat een snoepje wil hebben maar zijn mond niet open durft te doen. Jacob Ramesz, de ouwe vlooientemmer die een generatie lang kampioen landverbeuren van Solde en verre omgeving was geweest. Hij had zo weinig om handen dat hij de godganselijke dag rond het deurgat van zijn huis hing, in zijn neus peuterde en zijn reet krabde, terwijl roos op zijn schouders sneeuwde. De vlooientemmer probeerde uit te vissen of hij dichterbij mocht komen. Of hij naar het spelletje mocht kijken. In het gunstigste geval zou hij een partijtje mogen meespelen, al bestond daar weinig kans op. Kaffa hield niet van een tegenstander die hem nauwelijks of geen partij meer kon geven. Nog minder van mensen die hem alleen maar op de vingers keken, wachtend tot het mes hem van ergernis uit de hand zou schieten. Wat was de sensatie van het verlies? Wat maakte het Jacob Ramesz nou uit of Kaffa’s linkerhand verloor van zijn rechter? Ging het hem meer aan dan het sterven van de jongen? Het schijten van de buizerd, omdat het de gewoonste zaak van de wereld was? Het kakelen van de klanten in de winkels vlakbij? Wat trok een man als Jacob Ramesz naar Kaffa? Als hij nog geoefend was in het spel, dan was het anders. Maar een oude man, ook al was hij een half leven dorpskampioen geweest, was te zenuwachtig. Te rillerig. Een scherp mes in zijn hand was te gevaarlijk voor hemzelf en zijn tegenstander. Het zou makkelijk uit kunnen schieten en iemand verwonden, of een heel spel naar de bliksem helpen. Kaffa keek Jacob Ramesz afwijzend aan. De oude man begreep dat de gek hem niet te dicht in zijn omgeving wenste. Daar berustte hij dan maar in. Kaffa speelde ernstig. Hij wilde weten welke van zijn handen het sterkst was. Hij onderbrak het spel om af en toe naar Angela te kijken, die zich met de andere kinderen weer bij de spoelbak vermaakte. Ze had aan de bekoring van het water toch geen weerstand kunnen bieden en was er, met het voorbeeld van de waarzegger voor ogen, met kleren en al ingedoken.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (30)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

`Ik wil het niet op mijn geweten hebben’, zei hij schamper. `De mensen hebben me vaker uitgelachen als ik hun iets voorspelde wat niet in hun straatje te pas kwam. Ze wilden niet in hun ongeluk geloven. En later scholden ze me uit omdat alles uitkwam zoals ik het hun had gezegd.

`Ik wil het niet op mijn geweten hebben’, zei hij schamper. `De mensen hebben me vaker uitgelachen als ik hun iets voorspelde wat niet in hun straatje te pas kwam. Ze wilden niet in hun ongeluk geloven. En later scholden ze me uit omdat alles uitkwam zoals ik het hun had gezegd.

Ik zeg maar niks meer, meid, helemaal niks meer.’ `Ik wil het weten’, riep ze geschrokken. `Wat doet het er allemaal toe!’ riep hij uit, `de werkelijkheid bestaat toch pas achteraf.’ Toen lachte hij. Hij lachte breed. Hij leek te genieten van wat hij wist over de toekomst van de cafémeid. Door het voor haar geheim te houden had hij altijd een troef onder tafel voor het geval hij haar ergens voor nodig had. Hoe langer hij zou zwijgen, des te meer zou ze ervoor overhebben om dit geheim aan de weet te komen. Toen sprong hij op zijn ezel. Het arme dier leek bij dit onverwachte gewicht door zijn poten te zakken. Elysee schopte het dier met de hakken in de zij en stuurde het langs Céleste en de kinderen heen naar buiten. Hij sloeg de ezel met de vlakke hand op de schoft, alsof hij haast had om weg te komen. De anderen volgden hem naar buiten. Op de pomp afkoersend draaide Elysee zich naar haar om. Maakte een vaag armgebaar dat het hele dorp, het land, de bossen en de rivier insloot. Schudde misprijzend zijn hoofd. Keek weer voor zich. Liet zich, op zoek naar afkoeling, met al zijn kleren aan van de ezelsrug in de pompbak glijden. `Wat wil hij toch?’ vroeg Angela. Céleste haalde haar schouders op. Ze begreep niet veel van de bedoelingen van de man, maar hij maakte haar wel ongerust. Door het vreemde gedoe met de waarzegger waren de kinderen het spel vergeten.