Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Street Poetry: Signs

photo: fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Street Art

Verwisseling van de hoofden

De grotere, mooie zussen van mijn kamergenoot

waren echte teenagers, hielden van Buddy Holly.

Ik was tien jaar, verbleef zes hoog in het ziekenhuis,

leed aan een long waarin zich water had opgehoopt.

Uit een raam op de gang zag ik de zeven koolmijnen

in mijn provincie. Ik kende hun plaatsnamen en kon

de terril aanwijzen waarover elke dag mijn vader liep.

Herfst, de roetmoppen waren al uit de schoorsteen geveegd,

een vrachtauto laadde kolen af op ons erf

– de mijnwerkers mochten per dag een volle emmer

naar huis dragen, kolenbons sparen. Nadat ik kolen

in kruiwagens had geschopt telde ik mijn handblaren.

Kompel was hij niet, zijn naamwoord lichtte ik uit

compulsieve rompzinnen. Hij werkte in ’t zonlicht

boven op de mijn, schop ter hand, is in veertig jaar

niet één keer in de schacht afgedaald. Op de terril

won hij op een regendag vertrouwen van een jonge,

verdwaalde hond, bracht hem in zijn tas op de bus mee naar huis.

Er zijn jonge hondjes van gekomen.

Het ijverig bespuugde eelt in zijn handen is verdwenen.

Op zijn schouders staat soms mijn hoofd, dat bevangen raakt

door enge gedachten aan de reusachtige dreiging

van zware aardlagen op de diepdonkere, hete delfplek,

waar een claustrofobie, het eeuwig uitschurend stof en

nesten van ratten de totale schedelholte willen innemen.

Of op mijn schouders zijn hoofd, waarin ik eenvoudig denk

de dood te kunnen afhouden die hem onder de grond stopt.

Richard Steegmans

(Uit: Richard Steegmans: Ringelorend zelfportret op haar leeuwenhuid, uitgeverij Holland, Haarlem, 2005)

Richard Steegmans (Hasselt, 1952) is dichter en muzikant met een grote voorliefde voor rock, pop, soul, blues, country uit de jaren 60. Hij publiceerde de dichtbundels Uitgeslagen zomers, uitgeverij Perdu, Amsterdam, 2002, en Ringelorend zelfportret op haar leeuwenhuid, uitgeverij Holland, Haarlem, 2005. Gedichten van zijn hand verschenen in de literaire tijdschriften De Gids, Poëziekrant, Parmentier, DWB, Deus ex Machina, De Brakke Hond, Tortuca, Krakatau, Tzum en in talrijke bloemlezingen.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Steegmans, Richard

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

111

O for my sake do you with Fortune chide,

The guilty goddess of my harmful deeds,

That did not better for my life provide,

Than public means which public manners breeds.

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand:

Pity me then, and wish I were renewed,

Whilst like a willing patient I will drink,

Potions of eisel ‘gainst my strong infection,

No bitterness that I will bitter think,

Nor double penance to correct correction.

Pity me then dear friend, and I assure ye,

Even that your pity is enough to cure me.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (4)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

4

Coming to the end of the Corso Vittorio Emanuele, we crossed the bridge. I remember that I gazed almost with a religious awe at the dark rounded mass of Castel Sant’ Angelo, high and solemn under the twinkling of the stars. The great works of human architecture, by night, and the heavenly constellations seem to have a mutual understanding. In the humid chill of that immense nocturnal background, I felt this awe start up, flicker as in a succession of spasms, which were caused in me perhaps by the serpentine reflexions of the lights on the other bridges and on the banks, in the black mysterious water of the river. But Simone Pau tore me from this attitude of admiration, turning first in the direction of Saint Peter’s, then dodging aside along the Vicolo del Villano. Uncertain of the way, uncertain of everything, in the empty horror of the deserted streets, full of strange phantoms quivering from the rusty reflectors of the infrequent lamps, at every breath of air, on the walls of the old houses, I thought with terror and disgust of the people that were lying comfortably asleep in those houses and had no idea how their homes appeared from outside to such as wandered homeless through the night, without there being a single house anywhere which they might enter. Now and again, Simone Pau shook his head and tapped his chest

with two fingers. Oh, yes! The mountain was he, and the tree, and the sea; but the hotel, where was it? There, in Borgo Pio? Yes, close at hand, in the Vicolo del Falco. I raised my eyes; I saw on the right hand side of that alley a grim building, with a lantern hung out above the door: a big lantern, in which the flame of the gas-jet yawned through the dirty glass. I stopped in front of this door which was standing ajar, and read over the arch:

CASUAL SHELTER

“Do you sleep here?”

“Yes, and feed too. Lovely bowls of soup. In the best of company. Come in: this is my home.”

Indeed the old porter and two other men of the night staff of the Shelter, huddled and crouching together round a copper brazier, welcomed him as a regular guest, greeting him with gestures and in words from their glass cage in the echoing orridor:

“Good evening, Signor Professore.”

Simone Pau warned me, darkly, with great solemnity, that I must not be disappointed, for I should not be able to sleep in this hotel for more than six nights in succession. He explained to me that after every sixth night I should have to spend at least one outside, in the open, in order to start a fresh series.

I, sleep there?

In the presence of those three watchmen, I listened to his explanation with a melancholy smile, which, however, hovered ently over my lips, as though to preserve the buoyancy of my spirits and to keep them from sinking into the shame of this abyss.

Albeit in a wretched plight, with but a few lire in my pocket, I was well dressed, with gloves on my hands, spats on my ankles. I wanted to take the adventure, with this smile, as a whimsical caprice on the part of my strange friend. But Simone Pau was annoyed:

“You don’t take me seriously?”

“No, my dear fellow, indeed I don’t take you seriously.”

“You are right,” said Simone Pau, “serious, do you know who is really serious? The quack doctor with a black coat and no collar, with a big black beard and spectacles, who sends the medium to sleep in the market-place. I am not quite as serious as that yet. You may laugh, friend Serafino.”

And he went on to explain to me that it was all free of charge there. In winter, on the hammocks, a pair of clean sheets, solid and fresh as the sails of a ship, and two thick woollen blankets; in summer, the sheets alone, and a counterpane for anyone who wanted it; also a wrapper and a pair of canvas slippers, washable.

“Remember that, washable!”

“And why?”

“Let me explain. With these slippers and wrapper they give you a ticket; you go into that dressing-room there–through that door on the right–undress, and hand in your clothes, including your shoes, to be disinfected, which is done in the ovens over there. Then, come over here, look…. Do you see this lovely pond?”

I lowered my eyes and looked.

A pond? It was a chasm, mouldy, narrow and deep, a sort of den to herd swine in, carved out of the living rock, to which one went down by five or six steps, and over which there hung a pungent odour of suds.

A tin pipe, pierced with holes that were all yellow with rust, ran above it along the middle from end to end.

“Well?”

“You undress over there; hand in your clothes….”

“… shoes included….”

“… shoes included, to be disinfected, and step down here naked.”

“Naked?”

“Naked, in company with six or seven other nudes. One of our dear friends in the cage there turns on the tap, and you, standing under the pipe, zifff…, you get, free for nothing, a most beautiful shower. Then you dry yourself sumptuously with your wrapper, put on your canvas slippers, and steal quietly out in procession with the other draped figures up the stairs; there they are; up there is the dormitory, and so goodnight.”

“Is it compulsory?”

“What? The shower? Ah, because you are wearing gloves and spats, friend Serafino? But you can take them off without shame. Everyone here strips himself of his shame, and offers himself naked to the baptism of this pond! Haven’t you the courage to descend to these nudities?”

There was no need. The shower is obligatory only for unclean mendicants. Simone Pau had never taken it.

In this place he is, really, a schoolmaster. Attached to the shelter there are a soup kitchen and a refuge for homeless children of either sex, beggars’ children, prisoners’ children, children of every form of sin and shame. They are under the care of certain Sisters of Charity, who have managed to set up a little school for them as well. Simone Pau, albeit by profession a bitter enemy of humanity and of every form of teaching, gives lessons with the greatest pleasure to these

children, for two hours daily, in the early morning, and the children are extremely grateful to him. He is given, in return, his board and lodging: that is to say a little room, all to himself, clean and neat, and a special service of meals, shared with four other teachers, who are a poor old pensioner of the Papal Government and three spinster schoolmistresses, friends of the Sisters and taken in here by them. But Simone Pau dispenses with the special meals, since at midday he is never in the Shelter, and it is only in the evenings, when it suits his convenience, that he takes a bowlful or two of soup from the common kitchen; he keeps the little room, but he never uses it, because he goes and sleeps in the dormitory of the Night Shelter, for the sake of the company to be found there, which he has grown to relish, of queer, vagrant types. Apart from these two hours devoted to teaching, he spends all his time in the libraries and the ‘caffè’; every now and then, he publishes in some philosophic review an essay which amazes everyone by the bizarre novelty of the views expressed in it, the strangeness of the arguments and the abundance of learning displayed; and he flourishes again for a while.

At the time, I repeat, I was not aware of all this. I supposed, and perhaps it was partly true, that he had brought me there for the pleasure of bewildering me; and since there is no better way of disconcerting a person who is seeking to bewilder one with extravagant paradoxes or with the strangest, most fantastic suggestions than to pretend to accept those paradoxes as though they were the most obvious truisms, and his suggestions as entirely natural and opportune; so I behaved that evening, to disconcert my friend Simone Pau. He, realising my intention, looked me in the eyes and, seeing them to be completely impassive, exclaimed with a smile: “What an idiot you are!”

He offered me his room; I thought at first that he was joking; but when he assured me that he really had a room there to himself, I would not accept it and went with him to the dormitory of the Shelter. I am not sorry, since, for the discomfort and repulsion that I felt in that odious place, I had two compensations:

First; that of finding the post which I now hold, or rather the opportunity of going as an operator to the great cinematograph company, the Kosmograph;

Secondly; that of meeting the man who has remained for me ever since the symbol of the wretched fate to which continuous progress condemns the human race.

First of all, the man.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (4)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

to be continued

More in: -Shoot!

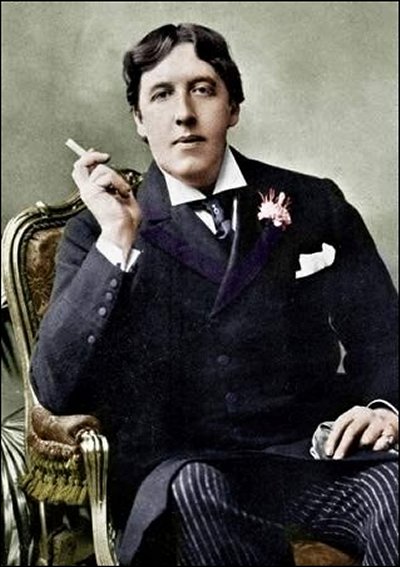

Oscar Wilde

(1854-1900)

Impression du Voyage

(sonnet)

The sea was sapphire colored, and the sky

Burned like a heated opal through the air,

We hoisted sail; the wind was blowing fair

For the blue lands that to the eastward lie.

From the steep prow I marked with quickening eye

Zakynthos, every olive grove and creek,

Ithaca’s cliff, Lycaon’s snowy peak,

And all the flower-strewn hills of Arcady.

The flapping of the sail against the mast,

The ripple of the water on the side,

The ripple of girls’ laughter at the stern,

The only sounds:- when ‘gan the West to burn,

And a red sun upon the seas to ride,

I stood upon the soil of Greece at last!

Katakolo

Oscar Wilde

Reisimpressie

(sonnet)

In de nieuwe vertaling van Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Het zeevlak glom met een saffieren tint,

De hemel stond als hete opaal in brand,

De wind trok aan; we tuigden ‘t want,

Voor ‘t blauwe land dat oostwaarts zich bevindt.

Ik zag vanaf de hoogste stevenkant

Zakynthos’ kreek en zijn olijventrots,

Lycaon’s sneeuwtop en Ithaca’s rots,

En ‘t bloemenrijk Arcadisch heuvelland.

De fok die klapperend om de stag zich wond,

Het water kabbelend voorlangs de boeg,

De meisjes kwebbelend in de kajuit,

Meer klonk er niet – dan brandde langzaam uit

Een rode zon op zee, die ‘m westwaarts droeg,

Ik stond nu eindelijk op Griekse grond!

Katakolo

VALLEND BLOEMBLAD

Verzameling van 90 korte gedichten van OSCAR WILDE

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld

tweetalige uitgave, 2011

ongepubliceerd

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Wilde, Wilde, Oscar

Dromen voor beginners

Een: Doe een handgeschreven brief op de post.

Twee: Plooi u in een warm bed naar een diepe slaap.

Drie: Heb in uw bestemming het volste vertrouwen.

Vier: Wals alleen met lang vergeten klasgenootjes.

Vijf: Groet zwaaiende matrozen met een glimlach.

Zes: Streel de drieste, warme zadels zachtjes.

Zeven: Hoor van de haan die u spant de klik.

Bert Bevers

(Verschenen in Het Hemelbed, Diksmuide, augustus 2006)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Street poetry: Soldaten sind Mörder (Berlin)

photo anton K. – fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, Street Art, Urban Art

Niet te bevatten

Duizend jaar worden

alleen al de gedachte

is te lang voor haiku.

Freda Kamphuis haiku

kempis.nl poetry magazine

©2011 fk

More in: Archive K-L, Kamphuis, Freda

![]()

Merels als kluizenaar

en een geleerde ‘witte volder’

Twee kanttekeningen bij Ierse ‘natuurgedichten’

Door Lauran Toorians

In het Oudiers (6e-10e eeuw) en in het Middeliers (10e-12e eeuw) zijn een groot aantal gedichten overgeleverd die traditioneel worden beschouwd als het werk van monniken (kluizenaars) en die zeker sinds de negentiende eeuw worden gelezen als lyrische natuurpoëzie. Deze opvatting werd vooral bekend door publicaties van mensen als Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) en Robin Flower (1881-1946) en bleef lang de gangbaar. Vreemd is dat niet, want het betreft gedichten die vaak nog direct – zonder uitgebreide toelichting of voetnoten – spreken tot de verbeelding van de moderne lezer. Ook na meer dan duizend jaar en ondanks het grote cultuurverschil slagen zij er nog steeds in de lezer direct te raken.

In 1989 publiceerde professor Donnchadh Ó Corráin echter een belangrijk artikel waarin hij niet alleen een vraagteken plaatste bij deze categorie van ‘vroege Ierse kluizenaarsgedichten’, maar waarin hij ook de romantische idee verwierp dat we in het Oudiers een groep gedichten hebben die uitdrukking geeft aan de primaire emoties en ervaringen van het kluizenaarsbestaan, als een ‘spirituele autobiografie in versvorm’. Ó Corráin kwam tot de conclusie dat de boodschap van de bedoelde gedichten geen persoonlijke was, maar de uitdrukking van het ideaal van een groep: ‘het klerikale leven is superieur aan het seculiere, zowel in deze wereld als in het hiernamaals’.

Deze gedichten, zo betoogde Ó Corráin, zetten ons op het verkeerde been doordat zij precies doen wat romantische natuurlyriek ook doet: zij spiegelen de lezer een geïdealiseerde wereld voor. De dichter was geen kluizenaar die in en dicht bij de natuur leefde, maar een monnik die in een grote kloostergemeenschap een zwaar leven leidde en hooguit kon dromen van een bestaan als heilige kluizenaar in de woeste natuur. Precies zoals een moderne bankklerk droomt van een vakantie op een onbewoond tropisch eiland en kan worden geraakt door jonge eendjes in de stadsvijver, zo verlangden de Oudierse kloosterlingen naar een leven als kluizenaar en droomden zij weg bij het lied van een merel.

Lees de volledige tekst van Lauran Toorians. . . Turdus merula-nl

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Mother

Mr Holohan, assistant secretary of the Eire Abu Society, had been walking up and down Dublin for nearly a month, with his hands and pockets full of dirty pieces of paper, arranging about the series of concerts. He had a game leg and for this his friends called him Hoppy Holohan. He walked up and down constantly, stood by the hour at street corners arguing the point and made notes; but in the end it was Mrs. Kearney who arranged everything.

Miss Devlin had become Mrs. Kearney out of spite. She had been educated in a high-class convent, where she had learned French and music. As she was naturally pale and unbending in manner she made few friends at school. When she came to the age of marriage she was sent out to many houses, where her playing and ivory manners were much admired. She sat amid the chilly circle of her accomplishments, waiting for some suitor to brave it and offer her a brilliant life. But the young men whom she met were ordinary and she gave them no encouragement, trying to console her romantic desires by eating a great deal of Turkish Delight in secret. However, when she drew near the limit and her friends began to loosen their tongues about her, she silenced them by marrying Mr. Kearney, who was a bootmaker on Ormond Quay.

He was much older than she. His conversation, which was serious, took place at intervals in his great brown beard. After the first year of married life, Mrs. Kearney perceived that such a man would wear better than a romantic person, but she never put her own romantic ideas away. He was sober, thrifty and pious; he went to the altar every first Friday, sometimes with her, oftener by himself. But she never weakened in her religion and was a good wife to him. At some party in a strange house when she lifted her eyebrow ever so slightly he stood up to take his leave and, when his cough troubled him, she put the eider-down quilt over his feet and made a strong rum punch. For his part, he was a model father. By paying a small sum every week into a society, he ensured for both his daughters a dowry of one hundred pounds each when they came to the age of twenty-four. He sent the older daughter, Kathleen, to a good convent, where she learned French and music, and afterward paid her fees at the Academy. Every year in the month of July Mrs. Kearney found occasion to say to some friend:

“My good man is packing us off to Skerries for a few weeks.”

If it was not Skerries it was Howth or Greystones.

When the Irish Revival began to be appreciable Mrs. Kearney determined to take advantage of her daughter’s name and brought an Irish teacher to the house. Kathleen and her sister sent Irish picture postcards to their friends and these friends sent back other Irish picture postcards. On special Sundays, when Mr. Kearney went with his family to the pro-cathedral, a little crowd of people would assemble after mass at the corner of Cathedral Street. They were all friends of the Kearneys, musical friends or Nationalist friends; and, when they had played every little counter of gossip, they shook hands with one another all together, laughing at the crossing of so many hands, and said good-bye to one another in Irish. Soon the name of Miss Kathleen Kearney began to be heard often on people’s lips. People said that she was very clever at music and a very nice girl and, moreover, that she was a believer in the language movement. Mrs. Kearney was well content at this. Therefore she was not surprised when one day Mr. Holohan came to her and proposed that her daughter should be the accompanist at a series of four grand concerts which his Society was going to give in the Antient Concert Rooms. She brought him into the drawing-room, made him sit down and brought out the decanter and the silver biscuit-barrel. She entered heart and soul into the details of the enterprise, advised and dissuaded: and finally a contract was drawn up by which Kathleen was to receive eight guineas for her services as accompanist at the four grand concerts.

As Mr. Holohan was a novice in such delicate matters as the wording of bills and the disposing of items for a programme, Mrs. Kearney helped him. She had tact. She knew what artistes should go into capitals and what artistes should go into small type. She knew that the first tenor would not like to come on after Mr. Meade’s comic turn. To keep the audience continually diverted she slipped the doubtful items in between the old favourites. Mr. Holohan called to see her every day to have her advice on some point. She was invariably friendly and advising, homely, in fact. She pushed the decanter towards him, saying:

“Now, help yourself, Mr. Holohan!”

And while he was helping himself she said:

“Don’t be afraid! Don t be afraid of it! “

Everything went on smoothly. Mrs. Kearney bought some lovely blush-pink charmeuse in Brown Thomas’s to let into the front of Kathleen’s dress. It cost a pretty penny; but there are occasions when a little expense is justifiable. She took a dozen of two-shilling tickets for the final concert and sent them to those friends who could not be trusted to come otherwise. She forgot nothing, and, thanks to her, everything that was to be done was done.

The concerts were to be on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. When Mrs. Kearney arrived with her daughter at the Antient Concert Rooms on Wednesday night she did not like the look of things. A few young men, wearing bright blue badges in their coats, stood idle in the vestibule; none of them wore evening dress. She passed by with her daughter and a quick glance through the open door of the hall showed her the cause of the stewards’ idleness. At first she wondered had she mistaken the hour. No, it was twenty minutes to eight.

In the dressing-room behind the stage she was introduced to the secretary of the Society, Mr. Fitzpatrick. She smiled and shook his hand. He was a little man, with a white, vacant face. She noticed that he wore his soft brown hat carelessly on the side of his head and that his accent was flat. He held a programme in his hand, and, while he was talking to her, he chewed one end of it into a moist pulp. He seemed to bear disappointments lightly. Mr. Holohan came into the dressingroom every few minutes with reports from the box-office. The artistes talked among themselves nervously, glanced from time to time at the mirror and rolled and unrolled their music. When it was nearly half-past eight, the few people in the hall began to express their desire to be entertained. Mr. Fitzpatrick came in, smiled vacantly at the room, and said:

“Well now, ladies and gentlemen. I suppose we’d better open the ball.”

Mrs. Kearney rewarded his very flat final syllable with a quick stare of contempt, and then said to her daughter encouragingly:

“Are you ready, dear?”

When she had an opportunity, she called Mr. Holohan aside and asked him to tell her what it meant. Mr. Holohan did not know what it meant. He said that the committee had made a mistake in arranging for four concerts: four was too many.

“And the artistes!” said Mrs. Kearney. “Of course they are doing their best, but really they are not good.”

Mr. Holohan admitted that the artistes were no good but the committee, he said, had decided to let the first three concerts go as they pleased and reserve all the talent for Saturday night. Mrs. Kearney said nothing, but, as the mediocre items followed one another on the platform and the few people in the hall grew fewer and fewer, she began to regret that she had put herself to any expense for such a concert. There was something she didn’t like in the look of things and Mr. Fitzpatrick’s vacant smile irritated her very much. However, she said nothing and waited to see how it would end. The concert expired shortly before ten, and everyone went home quickly.

The concert on Thursday night was better attended, but Mrs. Kearney saw at once that the house was filled with paper. The audience behaved indecorously, as if the concert were an informal dress rehearsal. Mr. Fitzpatrick seemed to enjoy himself; he was quite unconscious that Mrs. Kearney was taking angry note of his conduct. He stood at the edge of the screen, from time to time jutting out his head and exchanging a laugh with two friends in the corner of the balcony. In the course of the evening, Mrs. Kearney learned that the Friday concert was to be abandoned and that the committee was going to move heaven and earth to secure a bumper house on Saturday night. When she heard this, she sought out Mr. Holohan. She buttonholed him as he was limping out quickly with a glass of lemonade for a young lady and asked him was it true. Yes. it was true.

“But, of course, that doesn’t alter the contract,” she said. “The contract was for four concerts.”

Mr. Holohan seemed to be in a hurry; he advised her to speak to Mr. Fitzpatrick. Mrs. Kearney was now beginning to be alarmed. She called Mr. Fitzpatrick away from his screen and told him that her daughter had signed for four concerts and that, of course, according to the terms of the contract, she should receive the sum originally stipulated for, whether the society gave the four concerts or not. Mr. Fitzpatrick, who did not catch the point at issue very quickly, seemed unable to resolve the difficulty and said that he would bring the matter before the committee. Mrs. Kearney’s anger began to flutter in her cheek and she had all she could do to keep from asking:

“And who is the Cometty pray?”

But she knew that it would not be ladylike to do that: so she was silent.

Little boys were sent out into the principal streets of Dublin early on Friday morning with bundles of handbills. Special puffs appeared in all the evening papers, reminding the music loving public of the treat which was in store for it on the following evening. Mrs. Kearney was somewhat reassured, but be thought well to tell her husband part of her suspicions. He listened carefully and said that perhaps it would be better if he went with her on Saturday night. She agreed. She respected her husband in the same way as she respected the General Post Office, as something large, secure and fixed; and though she knew the small number of his talents she appreciated his abstract value as a male. She was glad that he had suggested coming with her. She thought her plans over.

The night of the grand concert came. Mrs. Kearney, with her husband and daughter, arrived at the Ancient Concert Rooms three-quarters of an hour before the time at which the concert was to begin. By ill luck it was a rainy evening. Mrs. Kearney placed her daughter’s clothes and music in charge of her husband and went all over the building looking for Mr. Holohan or Mr. Fitzpatrick. She could find neither. She asked the stewards was any member of the committee in the hall and, after a great deal of trouble, a steward brought out a little woman named Miss Beirne to whom Mrs. Kearney explained that she wanted to see one of the secretaries. Miss Beirne expected them any minute and asked could she do anything. Mrs. Kearney looked searchingly at the oldish face which was screwed into an expression of trustfulness and enthusiasm and answered:

“No, thank you!”

The little woman hoped they would have a good house. She looked out at the rain until the melancholy of the wet street effaced all the trustfulness and enthusiasm from her twisted features. Then she gave a little sigh and said:

“Ah, well! We did our best, the dear knows.”

Mrs. Kearney had to go back to the dressing-room.

The artistes were arriving. The bass and the second tenor had already come. The bass, Mr. Duggan, was a slender young man with a scattered black moustache. He was the son of a hall porter in an office in the city and, as a boy, he had sung prolonged bass notes in the resounding hall. From this humble state he had raised himself until he had become a first-rate artiste. He had appeared in grand opera. One night, when an operatic artiste had fallen ill, he had undertaken the part of the king in the opera of Maritana at the Queen’s Theatre. He sang his music with great feeling and volume and was warmly welcomed by the gallery; but, unfortunately, he marred the good impression by wiping his nose in his gloved hand once or twice out of thoughtlessness. He was unassuming and spoke little. He said yous so softly that it passed unnoticed and he never drank anything stronger than milk for his voice’s sake. Mr. Bell, the second tenor, was a fair-haired little man who competed every year for prizes at the Feis Ceoil. On his fourth trial he had been awarded a bronze medal. He was extremely nervous and extremely jealous of other tenors and he covered his nervous jealousy with an ebullient friendliness. It was his humour to have people know what an ordeal a concert was to him. Therefore when he saw Mr. Duggan he went over to him and asked:

“Are you in it too? “

“Yes,” said Mr. Duggan.

Mr. Bell laughed at his fellow-sufferer, held out his hand and said:

“Shake!”

Mrs. Kearney passed by these two young men and went to the edge of the screen to view the house. The seats were being filled up rapidly and a pleasant noise circulated in the auditorium. She came back and spoke to her husband privately. Their conversation was evidently about Kathleen for they both glanced at her often as she stood chatting to one of her Nationalist friends, Miss Healy, the contralto. An unknown solitary woman with a pale face walked through the room. The women followed with keen eyes the faded blue dress which was stretched upon a meagre body. Someone said that she was Madam Glynn, the soprano.

“I wonder where did they dig her up,” said Kathleen to Miss Healy. “I’m sure I never heard of her.”

Miss Healy had to smile. Mr. Holohan limped into the dressing-room at that moment and the two young ladies asked him who was the unknown woman. Mr. Holohan said that she was Madam Glynn from London. Madam Glynn took her stand in a corner of the room, holding a roll of music stiffly before her and from time to time changing the direction of her startled gaze. The shadow took her faded dress into shelter but fell revengefully into the little cup behind her collar-bone. The noise of the hall became more audible. The first tenor and the baritone arrived together. They were both well dressed, stout and complacent and they brought a breath of opulence among the company.

Mrs. Kearney brought her daughter over to them, and talked to them amiably. She wanted to be on good terms with them but, while she strove to be polite, her eyes followed Mr. Holohan in his limping and devious courses. As soon as she could she excused herself and went out after him.

“Mr. Holohan, I want to speak to you for a moment,” she said.

They went down to a discreet part of the corridor. Mrs Kearney asked him when was her daughter going to be paid. Mr. Holohan said that Mr. Fitzpatrick had charge of that. Mrs. Kearney said that she didn’t know anything about Mr. Fitzpatrick. Her daughter had signed a contract for eight guineas and she would have to be paid. Mr. Holohan said that it wasn’t his business.

“Why isn’t it your business?” asked Mrs. Kearney. “Didn’t you yourself bring her the contract? Anyway, if it’s not your business it’s my business and I mean to see to it.”

“You’d better speak to Mr. Fitzpatrick,” said Mr. Holohan distantly.

“I don’t know anything about Mr. Fitzpatrick,” repeated Mrs. Kearney. “I have my contract, and I intend to see that it is carried out.”

When she came back to the dressing-room her cheeks were slightly suffused. The room was lively. Two men in outdoor dress had taken possession of the fireplace and were chatting familiarly with Miss Healy and the baritone. They were the Freeman man and Mr. O’Madden Burke. The Freeman man had come in to say that he could not wait for the concert as he had to report the lecture which an American priest was giving in the Mansion House. He said they were to leave the report for him at the Freeman office and he would see that it went in. He was a grey-haired man, with a plausible voice and careful manners. He held an extinguished cigar in his hand and the aroma of cigar smoke floated near him. He had not intended to stay a moment because concerts and artistes bored him considerably but he remained leaning against the mantelpiece. Miss Healy stood in front of him, talking and laughing. He was old enough to suspect one reason for her politeness but young enough in spirit to turn the moment to account. The warmth, fragrance and colour of her body appealed to his senses. He was pleasantly conscious that the bosom which he saw rise and fall slowly beneath him rose and fell at that moment for him, that the laughter and fragrance and wilful glances were his tribute. When he could stay no longer he took leave of her regretfully.

“O’Madden Burke will write the notice,” he explained to Mr. Holohan, “and I’ll see it in.”

“Thank you very much, Mr. Hendrick,” said Mr. Holohan, “you’ll see it in, I know. Now, won’t you have a little something before you go?”

“I don’t mind,” said Mr. Hendrick.

The two men went along some tortuous passages and up a dark staircase and came to a secluded room where one of the stewards was uncorking bottles for a few gentlemen. One of these gentlemen was Mr. O’Madden Burke, who had found out the room by instinct. He was a suave, elderly man who balanced his imposing body, when at rest, upon a large silk umbrella. His magniloquent western name was the moral umbrella upon which he balanced the fine problem of his finances. He was widely respected.

While Mr. Holohan was entertaining the Freeman man Mrs. Kearney was speaking so animatedly to her husband that he had to ask her to lower her voice. The conversation of the others in the dressing-room had become strained. Mr. Bell, the first item, stood ready with his music but the accompanist made no sign. Evidently something was wrong. Mr. Kearney looked straight before him, stroking his beard, while Mrs. Kearney spoke into Kathleen’s ear with subdued emphasis. From the hall came sounds of encouragement, clapping and stamping of feet. The first tenor and the baritone and Miss Healy stood together, waiting tranquilly, but Mr. Bell’s nerves were greatly agitated because he was afraid the audience would think that he had come late.

Mr. Holohan and Mr. O’Madden Burke came into the room In a moment Mr. Holohan perceived the hush. He went over to Mrs. Kearney and spoke with her earnestly. While they were speaking the noise in the hall grew louder. Mr. Holohan became very red and excited. He spoke volubly, but Mrs. Kearney said curtly at intervals:

“She won’t go on. She must get her eight guineas.”

Mr. Holohan pointed desperately towards the hall where the audience was clapping and stamping. He appealed to Mr Kearney and to Kathleen. But Mr. Kearney continued to stroke his beard and Kathleen looked down, moving the point of her new shoe: it was not her fault. Mrs. Kearney repeated:

“She won’t go on without her money.”

After a swift struggle of tongues Mr. Holohan hobbled out in haste. The room was silent. When the strain of the silence had become somewhat painful Miss Healy said to the baritone:

“Have you seen Mrs. Pat Campbell this week?”

The baritone had not seen her but he had been told that she was very fine. The conversation went no further. The first tenor bent his head and began to count the links of the gold chain which was extended across his waist, smiling and humming random notes to observe the effect on the frontal sinus. From time to time everyone glanced at Mrs. Kearney.

The noise in the auditorium had risen to a clamour when Mr. Fitzpatrick burst into the room, followed by Mr. Holohan who was panting. The clapping and stamping in the hall were punctuated by whistling. Mr. Fitzpatrick held a few banknotes in his hand. He counted out four into Mrs. Kearney’s hand and said she would get the other half at the interval. Mrs. Kearney said:

“This is four shillings short.”

But Kathleen gathered in her skirt and said: “Now. Mr. Bell,” to the first item, who was shaking like an aspen. The singer and the accompanist went out together. The noise in hall died away. There was a pause of a few seconds: and then the piano was heard.

The first part of the concert was very successful except for Madam Glynn’s item. The poor lady sang Killarney in a bodiless gasping voice, with all the old-fashioned mannerisms of intonation and pronunciation which she believed lent elegance to her singing. She looked as if she had been resurrected from an old stage-wardrobe and the cheaper parts of the hall made fun of her high wailing notes. The first tenor and the contralto, however, brought down the house. Kathleen played a selection of Irish airs which was generously applauded. The first part closed with a stirring patriotic recitation delivered by a young lady who arranged amateur theatricals. It was deservedly applauded; and, when it was ended, the men went out for the interval, content.

All this time the dressing-room was a hive of excitement. In one corner were Mr. Holohan, Mr. Fitzpatrick, Miss Beirne, two of the stewards, the baritone, the bass, and Mr. O’Madden Burke. Mr. O’Madden Burke said it was the most scandalous exhibition he had ever witnessed. Miss Kathleen Kearney’s musical career was ended in Dublin after that, he said. The baritone was asked what did he think of Mrs. Kearney’s conduct. He did not like to say anything. He had been paid his money and wished to be at peace with men. However, he said that Mrs. Kearney might have taken the artistes into consideration. The stewards and the secretaries debated hotly as to what should be done when the interval came.

“I agree with Miss Beirne,” said Mr. O’Madden Burke. “Pay her nothing.”

In another corner of the room were Mrs. Kearney and he: husband, Mr. Bell, Miss Healy and the young lady who had to recite the patriotic piece. Mrs. Kearney said that the Committee had treated her scandalously. She had spared neither trouble nor expense and this was how she was repaid.

They thought they had only a girl to deal with and that therefore, they could ride roughshod over her. But she would show them their mistake. They wouldn’t have dared to have treated her like that if she had been a man. But she would see that her daughter got her rights: she wouldn’t be fooled. If they didn’t pay her to the last farthing she would make Dublin ring. Of course she was sorry for the sake of the artistes. But what else could she do? She appealed to the second tenor who said he thought she had not been well treated. Then she appealed to Miss Healy. Miss Healy wanted to join the other group but she did not like to do so because she was a great friend of Kathleen’s and the Kearneys had often invited her to their house.

As soon as the first part was ended Mr. Fitzpatrick and Mr. Holohan went over to Mrs. Kearney and told her that the other four guineas would be paid after the committee meeting on the following Tuesday and that, in case her daughter did not play for the second part, the committee would consider the contract broken and would pay nothing.

“I haven’t seen any committee,” said Mrs. Kearney angrily. “My daughter has her contract. She will get four pounds eight into her hand or a foot she won’t put on that platform.”

“I’m surprised at you, Mrs. Kearney,” said Mr. Holohan. “I never thought you would treat us this way.”

“And what way did you treat me?” asked Mrs. Kearney.

Her face was inundated with an angry colour and she looked as if she would attack someone with her hands.

“I’m asking for my rights.” she said.

You might have some sense of decency,” said Mr. Holohan.

“Might I, indeed? . . . And when I ask when my daughter is going to be paid I can’t get a civil answer.”

She tossed her head and assumed a haughty voice:

“You must speak to the secretary. It’s not my business. I’m a great fellow fol-the-diddle-I-do.”

“I thought you were a lady,” said Mr. Holohan, walking away from her abruptly.

After that Mrs. Kearney’s conduct was condemned on all hands: everyone approved of what the committee had done. She stood at the door, haggard with rage, arguing with her husband and daughter, gesticulating with them. She waited until it was time for the second part to begin in the hope that the secretaries would approach her. But Miss Healy had kindly consented to play one or two accompaniments. Mrs. Kearney had to stand aside to allow the baritone and his accompanist to pass up to the platform. She stood still for an instant like an angry stone image and, when the first notes of the song struck her ear, she caught up her daughter’s cloak and said to her husband:

“Get a cab!”

He went out at once. Mrs. Kearney wrapped the cloak round her daughter and followed him. As she passed through the doorway she stopped and glared into Mr. Holohan’s face.

“I’m not done with you yet,” she said.

“But I’m done with you,” said Mr. Holohan.

Kathleen followed her mother meekly. Mr. Holohan began to pace up and down the room, in order to cool himself for he his skin on fire.

“That’s a nice lady!” he said. “O, she’s a nice lady!”

“You did the proper thing, Holohan,” said Mr. O’Madden Burke, poised upon his umbrella in approval.

James Joyce: A Mother

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

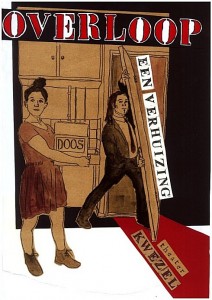

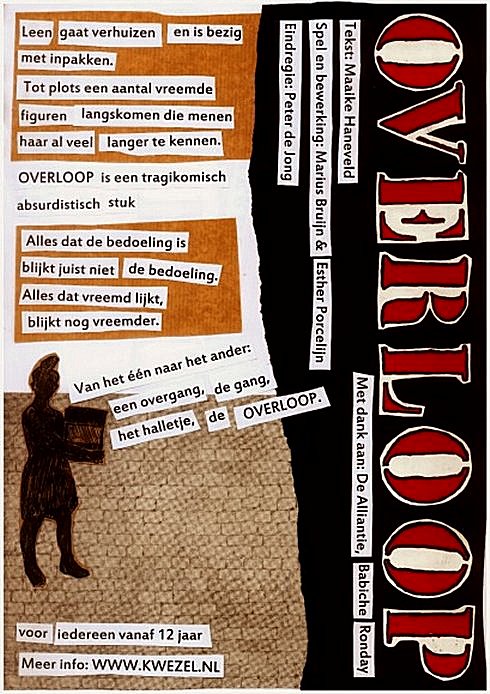

Theater Kwezel speelt:

OVERLOOP, een verhuizing

Een locatieproject in de Staalmanpleinbuurt, Amsterdam. Een theatervoorstelling over die belangrijke stap in je leven. Van Esther Porcelijn, Marius Bruijn en Maaike Haneveld. Overloop wordt een komische voorstelling met tekstscenes, poppenspel (voor volwassenen) en muziek voor iedereen vanaf 12 jaar.

Theater

OVERLOOP is gemaakt op locatie op het Abraham Staalmanplein in Amsterdam Slotervaart. In deze buurt, de Staalmanpleinbuurt, zijn grootschalige veranderingen gaande. Oude flats worden afgebroken, nieuwe worden gebouwd. Overal zijn mensen aan het verhuizen. Dit is het decor van de komische en absurdistische theatervoorstelling. Ons personage, Leen, woont te midden van deze straten. En ze is vastbesloten te vertrekken.

Thema

Overloop gaat over een overgangsfase, een stap in het onbekende. Het onbekende ziet er wellicht duister, bedreigend en verwarrend uit, er lijken weinig wegen te bewandelen en weinig perspectief op verbetering. En toch wil hoofdpersoon Leen die stap zetten. Om er in de nieuwe situatie beter en zelfverzekerder uit te komen. En misschien is die nieuwe situatie wel gewoon in het oude huis!

De Makers

Bewerking en spel: Marius Bruijn & Esther Porcelijn

Regie: Peter de Jong

Tekst: Maaike Haneveld

Bekijk de Teaser op YouTube

Voorstellingen

OP LOCATIE op het Abraham Staalmanplein 12, Amsterdam Slotervaart, Borrel na afloop

– try out – vrijdag 13 jan. 19:00

– première – vrijdag 13 jan. 21:00

– zaterdag 14 jan. 16:00 en 20:00

– zondag 15 jan. 14:00 en 17:00

– zaterdag 21 jan. 16:00 en 20:00

– zondag 22 jan. 14:00 en 17:00

Extra voorstellingen in de

Vondelbunker: Vondelpark 6, Amsterdam

www.vondelbunker.nl

– vrijdag 20 januari 2012, Toegang 10 euro,

reserveren aanbevolen via: marius@kwezel.nl

Meer info op www.kwezel.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther, THEATRE

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

110

Alas ’tis true, I have gone here and there,

And made my self a motley to the view,

Gored mine own thoughts, sold cheap what is most dear,

Made old offences of affections new.

Most true it is, that I have looked on truth

Askance and strangely: but by all above,

These blenches gave my heart another youth,

And worse essays proved thee my best of love.

Now all is done, have what shall have no end,

Mine appetite I never more will grind

On newer proof, to try an older friend,

A god in love, to whom I am confined.

Then give me welcome, next my heaven the best,

Even to thy pure and most most loving breast.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature