Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

I. Roccoco Japonais

O toi dont l’oeil est noir, les tresses noires, les chairs blondes, écoute-moi, ô ma folâtre louve!

J’aime tes yeux fantasques, tes yeux qui se retroussent sur les tempes; j’aime ta bouche rouge comme une baie de sorbier, tes joues rondes et jaunes; j’aime tes pieds tors, ta gorge roide, tes grands ongles lancéolés, brillants comme des valves de nacre.

J’aime, ô mignarde louve, ton énervant nonchaloir, ton sourire alangui, ton attitude indolente, tes gestes mièvres.

J’aime, ô louve câline, les miaulements de ta voix, j’aime ses tons ululants et rauques, mais j’aime par-dessus tout, j’aime à en mourir, ton nez, ton petit nez qui s’échappe des vagues de ta chevelure, comme une rose jaune éclose dans un feuillage noir!

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 30

By ‘t beschouwen van een kunstwerk, by ‘t schatten ener uitstekende daad, by ‘t beoordelen van een uitgedrukte gedachte, leg ik myzelf altyd de vraag voor: wat is er omgegaan in de ziel des kunstenaars, van de held, van de wysgeer, om dat ideaal te scheppen, om tot die daad te besluiten, om die gedachte voort te brengen, en ze vorm te geven als denkbeeld? Dat is: ik vraag, hoe de ziel bevrucht werd? Welke toestanden ze doorliep by dracht en verlossing?

Welnu, de geschiedenis ener grote conceptie roept me altyd de tekst toe: met smart zult ge kinderen baren!

Als ‘n graankorrel spreken kon, zou ze klagen dat er smart ligt in ‘t ontkiemen.

Helden, artiesten en wysgeren zullen my begrypen, en de klacht van die graankorrel verstaan.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

Sonnet Liminaire

Des croquis de concert et de bals de barrière;

La reine Marguerite, un camaïeu pourpré;

Des naïades d’égout au sourire éploré,

Noyant leur long ennui dans des pintes de bière,

Des cabarets brodés de pampre et de lierre,

Le poète Villon, dans un cachot, prostré,

Ma tant douce tourmente, un hareng mordoré,

L’amour d’un paysan et d’une maraîchère,

Tels sont les principaux sujets que j’ai traités:

Un choix de bric-à-brac, vieux médaillons sculptés,

Emaux, pastels pâlis, eau-forte, estampe rousse,

Idoles aux grands yeux, aux charmes décevants,

Paysans de Brauwer, buvant, faisant carrousse,

Sont là. Les prenez-vous? A bas prix je les vends.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

Index

Sonnet liminaire

I. Rococo japonais

II. Ritournelle

III. Camaieu rouge.

IV. Déclaration d’amour

V. La Reine Margot

VI. La Kermesse de Rubens

VII. Lächeté

VIII. Claudine

IX. Le hareng saur

X. Ballade chlorotique

XI. Variation sur un air connu

XII. L’Extase

XIII. Ballade en l’honneur de ma tant douce tourmente

XIV. La rive gauche

XV. A maïtre François Villon

XVI. Adrien Brauwer

XVII. Cornélius Béga

XVIII. L’Emailleuse

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

Critiques

Journal illustré (Revue Litteraire), 8 novembre 1874: Il vient de paraître chez Dentu un volume étrange, signé Jorris-Karl Huysmans. L’auteur, dont le nom, inconnu aujourd’hui, nous parait appelé à prendre place à la suite des noms de certains écrivains coloristes, a réuni dans les quelques pièces qui forment le Drageoir à épices, une série de nouvelles et de petits poëms en prose dont la lecture nous a laissé une impression étrange, quelque fois bonne, souvent mauvaise, mais qui attirera l’attention des lettrés et des artistes.

Peut-être trouveront-ils, éparpillées ça et là, dans ce petit volume, quelques pièces d’un réalisme effroayable, qui les feront bondir et s’indiguer, peut-être regretteront-ils que l’auteur se soit donné tant de mal pour traiter des sujets aussi bizarres et quelquefois mème aussi scabreux, et peut-être encore…auront-ils raison?

Le rappel, 17 novembre 1874: Nous avons devant nous plusieurs publications d’un vif intérêt, dont nous regrettons de ne pouvoir parler à loisir. Le Drageoir à épices de M. Jorris-Karl Huysmans, un très joli volume édité chez Dentu, renferme des pages originales et chaudement colorées. Claudine et le Camaïeu rouge sont, entre autres, de remarkables études.

L’Illustration, 5 décembre, 1874: Le Drageoir à épices, de M. J.-K. Huysmans, est un petit livre pour les raffinés. Il y a là un prestigieux talent de description, avec de la bizarrerie et de la recherche. (Jules Claretie)

L’Evénement (Causerie littéraire), 10 décembre, 1874: …Un autre jeune homme, —il est tout seul celui-ci -, signe de son nom flamand Jorris Karl Huysmans le Drageoir à épices. Le dit drageoir a été ouvragé par Aloysius Bertrand, les épices ont été fournies par Baudelaire. En verité, nous retournons au dix-huitième siècle, au Sopha, à Angola, aux Bijoux indiscrets… (Charles Monselet)

Le National, 18 janvier, 1875: Le Drageoir aux épices par J.-K. Huysmans. Les poètes seuls savent célébrer les poètes et c’est ainsi que je trouve la plus touchante, la plus douloureuse, la plus superbe apostrophe au grand rimeur des Ballades, Villon, dans un petit livre de prose amoureusement ciselée par un poète, M. Jarris (sic) Karl Huysmans qui en un temps dédaigneux (sa part est pourtant la meillure!) s’occupe de sertir le mot, de peindre par l’harmonie et par le mouvement de la phrase, comme Gaspard de la Nuit, comme Flaubert, comme Baudelaire, commes les Goncourt! Son Drageoir aux épices est un joyau de savant orfèvre, ciselé d’une main ferme et légère… (Théodore de Banville)

Le conseilleur du Bibliophile, 1 septembre 1876: Ce petit volume est un régal pour les raffinés, les artistes et les poètes; ils se divertissent fort de cette faculté très-spéciale que possède J.-K. Huysmans, d’intéresser par une simple énumération de bibelots quelconques ; en lisant le Drageoir il semble qu’on soit transporté à l’hôtel Drouot, un jour de grande exposition d’objets d’art de toute sortes, ou rencontre aussi parfois, dans ses pages, des audaces juvéniles comme celle-ci : « Entends-tu, ribaude infâme, je te hais, je te méprise…et je t’aime !»

Le Drageoir à épices, tiré à un très-petit nombre d’exemplaires, sera bientôt une rareté bibliophilique, on le recherchera avidement, car son auteur, qui le considère peut-être aujourd’hui comme un péché de jeunesse, est en passe de devenir célèbre, avec un roman qu’il va publier prochainement. Il est intitulé Marthe.

Karl-Jorris Huysmans n’est pas d’ailleurs un inconnu, il a travaillé dans de nombreuses revues où il a connu d’excellents articles sur les arts ; en compagnie de G. Flaubert, E. Zola, Cladel, Maurice Bouchor, etc., il collabore actuellement à la Republique des lettres. (René Pajou)

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K., Joris-Karl Huysmans

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

See they come, post haste from Thanet

See they come, post haste from Thanet,

Lovely couple, side by side;

They’ve left behind them Richard Kennet

With the Parents of the Bride!

Canterbury they have passed through;

Next succeeded Stamford-bridge;

Chilham village they came fast through;

Now they’ve mounted yonder ridge.

Down the hill they’re swift proceeding,

Now they skirt the Park around;

Lo! The Cattle sweetly feeding

Scamper, startled at the sound!

Run, my Brothers, to the Pier gate!

Throw it open, very wide!

Let it not be said that we’re late

In welcoming my Uncle’s Bride!

To the house the chaise advances;

Now it stops–They’re here, they’re here!

How d’ye do, my Uncle Francis?

How does do your Lady dear?

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

.jpg)

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

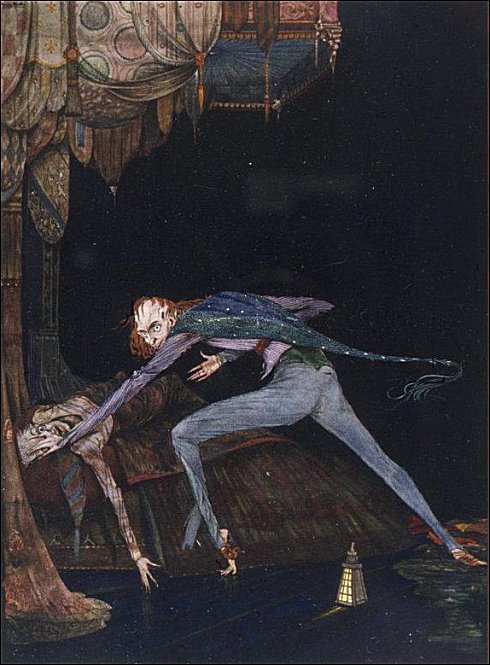

The Tell-Tale Heart

True! nervous, very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why WILL you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses, not destroyed, not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How then am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily, how calmly, I can tell you the whole story.

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain, but, once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! Yes, it was this! One of his eyes resembled that of a vulture — a pale blue eye with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me my blood ran cold, and so by degrees, very gradually, I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye for ever.

Now this is the point. You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded — with what caution — with what foresight, with what dissimulation, I went to work! I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him. And every night about midnight I turned the latch of his door and opened it oh, so gently! And then, when I had made an opening sufficient for my head, I put in a dark lantern all closed, closed so that no light shone out, and then I thrust in my head. Oh, you would have laughed to see how cunningly I thrust it in! I moved it slowly, very, very slowly, so that I might not disturb the old man’s sleep. It took me an hour to place my whole head within the opening so far that I could see him as he lay upon his bed. Ha! would a madman have been so wise as this? And then when my head was well in the room I undid the lantern cautiously — oh, so cautiously — cautiously (for the hinges creaked), I undid it just so much that a single thin ray fell upon the vulture eye. And this I did for seven long nights, every night just at midnight, but I found the eye always closed, and so it was impossible to do the work, for it was not the old man who vexed me but his Evil Eye. And every morning, when the day broke, I went boldly into the chamber and spoke courageously to him, calling him by name in a hearty tone, and inquiring how he had passed the night. So you see he would have been a very profound old man, indeed , to suspect that every night, just at twelve, I looked in upon him while he slept.

Upon the eighth night I was more than usually cautious in opening the door. A watch’s minute hand moves more quickly than did mine. Never before that night had I felt the extent of my own powers, of my sagacity. I could scarcely contain my feelings of triumph. To think that there I was opening the door little by little, and he not even to dream of my secret deeds or thoughts. I fairly chuckled at the idea, and perhaps he heard me, for he moved on the bed suddenly as if startled. Now you may think that I drew back — but no. His room was as black as pitch with the thick darkness (for the shutters were close fastened through fear of robbers), and so I knew that he could not see the opening of the door, and I kept pushing it on steadily, steadily.

I had my head in, and was about to open the lantern, when my thumb slipped upon the tin fastening , and the old man sprang up in the bed, crying out, “Who’s there?”

I kept quite still and said nothing. For a whole hour I did not move a muscle, and in the meantime I did not hear him lie down. He was still sitting up in the bed, listening; just as I have done night after night hearkening to the death watches in the wall.

Presently, I heard a slight groan, and I knew it was the groan of mortal terror. It was not a groan of pain or of grief — oh, no! It was the low stifled sound that arises from the bottom of the soul when overcharged with awe. I knew the sound well. Many a night, just at midnight, when all the world slept, it has welled up from my own bosom, deepening, with its dreadful echo, the terrors that distracted me. I say I knew it well. I knew what the old man felt, and pitied him although I chuckled at heart. I knew that he had been lying awake ever since the first slight noise when he had turned in the bed. His fears had been ever since growing upon him. He had been trying to fancy them causeless, but could not. He had been saying to himself, “It is nothing but the wind in the chimney, it is only a mouse crossing the floor,” or, “It is merely a cricket which has made a single chirp.” Yes he has been trying to comfort himself with these suppositions ; but he had found all in vain. ALL IN VAIN, because Death in approaching him had stalked with his black shadow before him and enveloped the victim. And it was the mournful influence of the unperceived shadow that caused him to feel, although he neither saw nor heard, to feel the presence of my head within the room.

When I had waited a long time very patiently without hearing him lie down, I resolved to open a little — a very, very little crevice in the lantern. So I opened it — you cannot imagine how stealthily, stealthily — until at length a single dim ray like the thread of the spider shot out from the crevice and fell upon the vulture eye.

It was open, wide, wide open, and I grew furious as I gazed upon it. I saw it with perfect distinctness — all a dull blue with a hideous veil over it that chilled the very marrow in my bones, but I could see nothing else of the old man’s face or person, for I had directed the ray as if by instinct precisely upon the damned spot.

And now have I not told you that what you mistake for madness is but over-acuteness of the senses? now, I say, there came to my ears a low, dull, quick sound, such as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I knew that sound well too. It was the beating of the old man’s heart. It increased my fury as the beating of a drum stimulates the soldier into courage.

But even yet I refrained and kept still. I scarcely breathed. I held the lantern motionless. I tried how steadily I could maintain the ray upon the eye. Meantime the hellish tattoo of the heart increased. It grew quicker and quicker, and louder and louder, every instant. The old man’s terror must have been extreme! It grew louder, I say, louder every moment! — do you mark me well? I have told you that I am nervous: so I am. And now at the dead hour of the night, amid the dreadful silence of that old house, so strange a noise as this excited me to uncontrollable terror. Yet, for some minutes longer I refrained and stood still. But the beating grew louder, louder! I thought the heart must burst. And now a new anxiety seized me — the sound would be heard by a neighbour! The old man’s hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once — once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But for many minutes the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more.

Illustration H. Clarke

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence.

I took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly so cunningly, that no human eye — not even his — could have detected anything wrong. There was nothing to wash out — no stain of any kind — no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that.

When I had made an end of these labours, it was four o’clock — still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart, — for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbour during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

I smiled, — for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search — search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

The officers were satisfied. My MANNER had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears; but still they sat, and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct : I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definitiveness — until, at length, I found that the noise was NOT within my ears.

No doubt I now grew VERY pale; but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased — and what could I do? It was A LOW, DULL, QUICK SOUND — MUCH SUCH A SOUND AS A WATCH MAKES WHEN ENVELOPED IN COTTON. I gasped for breath, and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly, more vehemently but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why WOULD they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men, but the noise steadily increased. O God! what COULD I do? I foamed — I raved — I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder — louder — louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly , and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God! — no, no? They heard! — they suspected! — they KNEW! — they were making a mockery of my horror! — this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! — and now — again — hark! louder! louder! louder! LOUDER! —

“Villains!” I shrieked, “dissemble no more! I admit the deed! — tear up the planks! — here, here! — it is the beating of his hideous heart!”

Edgar Allan Poe: The Tell-Tale Heart

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

.jpg)

Ein altes Blatt

Franz Kafka (1883-1924

Es ist, als wäre viel vernachlässigt worden in der Verteidigung unseres Vaterlandes. Wir haben uns bisher nicht darum gekümmert und sind unserer Arbeit nachgegangen; die Ereignisse der letzten Zeit machen uns aber Sorgen.

Ich habe eine Schusterwerkstatt auf dem Platz vor dem kaiserlichen Palast. Kaum öffne ich in der Morgendämmerung meinen Laden, sehe ich schon die Eingänge aller hier einlaufenden Gassen von Bewaffneten besetzt. Es sind aber nicht unsere Soldaten, sondern offenbar Nomaden aus dem Norden. Auf eine mir unbegreifliche Weise sind sie bis in die Hauptstadt gedrungen, die doch sehr weit von der Grenze entfernt ist. Jedenfalls sind sie also da; es scheint, daß jeden Morgen mehr werden.

Ihrer Natur entsprechend lagern sie unter freiem Himmel, denn Wohnhäuser verabscheuen sie. Sie beschäftigen sich mit dem Schärfen der Schwerter, dem Zuspitzen der Pfeile, mit Übungen zu Pferde. Aus diesem stillen, immer ängstlich rein gehaltenen Platz haben sie einen wahren Stall gemacht. Wir versuchen zwar manchmal aus unseren Geschäften hervorzulaufen und wenigstens den ärgsten Unrat wegzuschaffen, aber es geschieht immer seltener, denn die Anstrengung ist nutzlos und bringt uns überdies in die Gefahr, unter die wilden Pferde zu kommen oder von den Peitschen verletzt zu werden.

Sprechen kann man mit den Nomaden nicht. Unsere Sprache kennen sie nicht, ja sie haben kaum eine eigene. Unter einander verständigen sie sich ähnlich wie Dohlen. Immer wieder hört man diesen Schrei der Dohlen. Unsere Lebensweise, unsere Einrichtungen sind ihnen ebenso unbegreiflich wie gleichgültig. Infolgedessen zeigen sie sich auch gegen jede Zeichensprache ablehnend. Du magst dir die Kiefer verrenken und die Hände aus den Gelenken winden, sie haben dich doch nicht verstanden und werden dich nie verstehen. Oft machen sie Grimassen; dann dreht sich das Weiß ihrer Augen und Schaum schwillt aus ihrem Munde, doch wollen sie damit weder etwas sagen noch auch erschrecken; sie tun es, weil es so ihre Art ist. Was sie brauchen, nehmen sie. Man kann nicht sagen, daß sie Gewalt anwenden. Vor ihrem Zugriff tritt man beiseite und überläßt ihnen alles.

Auch von meinen Vorräten haben sie manches gute Stück genommen. Ich kann aber darüber nicht klagen, wenn ich zum Beispiel zusehe, wie es dem Fleischer gegenüber geht. Kaum bringt er seine Waren ein, ist ihm schon alles entrissen und wird von den Nomaden verschlungen. Auch ihre Pferde fressen Fleisch; oft liegt ein Reiter neben seinem Pferd und beide nähren sich vom gleichen Fleischstück, jeder an einem Ende. Der Fleischhauer ist ängstlich und wagt es nicht, mit den Fleischlieferungen aufzuhören. Wir verstehen das aber, schießen Geld zusammen und unterstützen ihn. Bekämen die Nomaden kein Fleisch, wer weiß, was ihnen zu tun einfiele; wer weiß allerdings, was ihnen einfallen wird, selbst wenn sie täglich Fleisch bekommen.

Letzthin dachte der Fleischer, er könne sich wenigstens die Mühe des Schlachtens sparen, und brachte am Morgen einen lebendigen Ochsen. Das darf er nicht mehr wiederholen. Ich lag wohl eine Stunde ganz hinten in meiner Werkstatt platt auf dem Boden und alle meine Kleider, Decken und Polster hatte ich über mir aufgehäuft, nur um das Gebrüll des Ochsen nicht zu hören, den von allen Seiten die Nomaden ansprangen, um mit den Zähnen Stücke aus seinem warmen Fleisch zu reißen. Schon lange war es still, ehe ich mich auszugehen getraute; wie Trinker um ein Weinfaß lagen sie müde um die Reste des Ochsen.

Gerade damals glaubte ich den Kaiser selbst in einem Fenster des Palastes gesehen zu haben; niemals sonst kommt er in diese äußeren Gemächer, immer nur lebt er in dem innersten Garten; diesmal aber stand er, so schien es mir wenigstens, an einem der Fenster und blickte mit gesenktem Kopf auf das Treiben vor seinem Schloß.

»Wie wird es werden?« fragen wir uns alle. »Wie lange werden wir diese Last und Qual ertragen? Der kaiserliche Palast hat die Nomaden angelockt, versteht es aber nicht, sie wieder zu vertreiben. Das Tor bleibt verschlossen; die Wache, früher immer festlich ein- und ausmarschierend, hält sich hinter vergitterten Fenstern. Uns Handwerkern und Geschäftsleuten ist die Rettung des Vaterlandes anvertraut; wir sind aber einer solchen Aufgabe nicht gewachsen; haben uns doch auch nie gerühmt, dessen fähig zu sein. Ein Mißverständnis ist es, und wir gehen daran zugrunde.

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 1077

…wanneer Tollens’ ouders hem vergund hadden z’n neiging te volgen, wat zou er gebeurd zyn? Me dunkt dat de man, met verfwaren en al, verzen genoeg gemaakt heeft. Ik heb nooit ‘in verf gedaan’ en weet dus niet of ‘t ‘n uitputtend onderwerp is, doch houd voor zeker dat ‘ndenkend wezen ‘t daarin langer kan uithouden dan in rymelary. Tollens weet niet welken dienst hem z’n ouders bewezen, en ook de Natie is hun dank schuldig. Het is juist een der verdiensten van ons landje, dat men daarin van verzenmaken alleen niet leven kan. Ten Kate zelf, die ‘t in de hebbelykheid om woorden in maat en rym te zetten, heel ver gebracht heeft, is in oogenblikken van matelooze ongerymdheid wel genoodzaakt te preeken en te katechizeeren om in leven te blyven, terwyl jeneverstokers hoogstens onbezoldigde leden van ‘n kieskollegie of ‘n kerkeraad behoeven te zyn, om hun plaats als ‘nuttig lid der maatschappy’ te handhaven.

Tollens heeft schoone stukken geleverd – Ten Kate ook! – maar ik betwyfel of ‘t getal daarvan grooter zou geweest zyn, indien hy niet door z’n ‘verfwaren’ ware geperst tot uiting. En tevens, of niet de massa onbeduidende geestelooze, en zelfs bespottelyke, dingen waaraan hy zich schuldig maakte, nog verpletterender zou geweest zyn, indien hy niet door z’n prozaïsch beroep nu-en-dan ware belemmerd in ‘t voortrymelen. Ik wou dat alle verzenmakers ‘in’ verfwaren gingen. Preeken en katechizeeren werkt minder krachtig, naar ‘t schynt.

Daar ik alzoo aan den smaak der kinderen zoo weinig invloed wil toegekend zien op de keuze van ‘n beroep, zou men misschien meenen dat ik ouders aanraad by-uitsluiting acht te slaan op ‘t karakter en de begaafdheden van hun kroost. Ook dit echter mag ik geenszins toestemmen, en wel vooral omdat het karakter en de gaven van ‘n kind gewoonlyk aan z’n ouders onbekend zyn. Velen zullen dit niet dan ongaarne erkennen, maar ieder zal het met my eens worden, zoodra hy ‘t oog slaat op de kinderen van ‘n ander. Dan ziet men in, dat weinigen minder geschikt zyn om ‘n jeugdig mensch te beoordeelen, dan de vader en de moeder die ‘t van wieg en borst af hebben gezien door ‘t prismavan liefde en ydelheid. En ook zonder deze beide oordeelbedervende elementen, men ziet niet goed van zéér – d.i. hier: van al te – naby. (122)

En dan de waarheidverdraaiende boekenpraatjes! De Ruiter was of werd ‘n heldomdat-i de lei stuk trapte op den Vlissingschen toren. In Gassendi stak ‘n groot sterrekundige want als herdersjongen zat-i met zoo’n slim gezichtje naar den hemel te kyken. Al zulke vertellingen zyn après coup gemaakt. Of, al ware dit zoo niet, ze zyn niet van toepassing. Zeker, er is verband tusschen de neigingen of de gaven van den knaap en de hoedanigheden van den man, maar dit verband ligt niet zóó, niet op die wyze, bloot. Zeer dikwyls openbaart het zich door iets dat den oppervlakkigen beschouwer voorkomt als tegenstelling. Hiervan slechts één voorbeeld, maar ‘t is sprekend en voldoende. Van Speyk, de nobele woordhoudende Van Speyk was – en niet alleen als kind, maar zelfs nog toen-i reeds lang zee-officier was, en in Indie tegen de roovers z’n sporen verdiend had – zeer beschroomd. Hy stamelde en toonde zich verlegen toen-i by den schilder Hodges z’n portret bestelde. Ik zie kans ‘t verband tusschen zoodanige gemoedsfout en heldendeugd aantetoonen, even goed als ik ‘t verband ken tusschen dierlyke brutaliteit en lafhartigheid, maar ik durf vragen of de meeste ouders op de hoogte zyn om deze schynbare psychische tegenstrydigheid optelossen?

Er bestaat nog ‘n andere reden die de vermeende eigenaardigheid van ‘n kind onbruikbaar maakt tot leiddraad voor beroepskeuze. Die eigenaardigheid is zeer dikwyls opgedrongen. Men meent iets in hem te hebben opgemerkt, en spreekt er over. Het kind hoort dit, wil belangwekkend zyn, enschynt weldra te wezen wat men voorgaf en uitbazuinde dat-i wàs. De zucht om niet beneden den roep te staan die er van hem uitgaat, is zóó sterk dat-i zich beyveren zal ‘n zeer ongunstige eigenschap ten-toon te spreiden, zoodra men die met geruchtmakende overdryving – als iets zéér byzonders dus – gelaakt heeft. Zóó, byv. kost het weinig moeite ‘n kind driftig, koppig, lui en leugenachtig te maken. Daartoe behoeft men hem slechts in den waan te brengen dat-i in-staat is in deze fraaie vakken iets uitstekends te leveren. Hy laat zich dan den roem van ‘t meesterschap niet ontgaan. De lezer weet immers dat kinderen dit met krankzinnigen en beschonkenen gemeen hebben, dat ze zich nooit voordoen zooals ze zyn, wanneer ze weten dat men hen gadeslaat? Deze opmerking is van volle toepassing op hun fouten. Zoodra dezen in de schatting hunner omgeving de gewone maat te-buiten gaan, wordt er mee gepronkt.

Doch, aangenomen eens dat eigenaardigheden in bekwaamheid of karakter ‘n minder bedriegelyken leiddraad opleverden tot het kiezen van ‘n beroep, wat zou er dan worden van de tallooze bedryven die geen byzondere gaven van verstand of gemoed vereischen? Wat ook van de kinderen die geen byzondere geestesrichting aan den dag leggen? Het bemannen onzer vloot kan immers niet wachten op de voltalligheid van ‘t kontingent kinderen die torens beklommen hebben? En, omgekeerd, moeten ouders de beslissing omtrent den werkkring van hun kroost uitstellen tot het blyk geeft van byzonderen aanleg? Welke byzonderheid zou dan telkens ‘t sein wezen dat het kind geschikt is voor zeker beroep? Hoe moet zich de knaap gedragen, om te kennen te geven dat-i door onzen lieven-heer bestemd is tot kleermaker? Tot vetweider? Tot winkelier? Tot kouponknipper? Hoe onderscheidt men de roeping voor onderdeelen van zekere vakken? Waaruit blykt of de knaap geschikter is voor ‘assurantie’ dan ‘reedery?’ Bekwamer in suiker dan in koffi? Wie verzekert ons dat de eskapade van den jongen De Ruiter niet ‘n vingerwyzing van de Natuur was, dat-i in den wieg was gelegd voor schoorsteenveger of leidekker?

En hoe te handelen, indien de knaap neigingen, begeerten of hebbelykheden aan den dag legt, die niet toepasselyk zyn op de omstandigheden of op ‘t land waarin hy geboren werd? Wat moet de Afrikaan met z’n zoontjen aanvangen, als ‘t door waggelenden gang byzonderen aanleg openbaart voor schaatsryden? Of de Hollander, wanneer-i bemerkt dat z’n kind behebt is met rechtsgevoel?

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

The Black Cat

For the most wild, yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief. Mad indeed would I be to expect it, in a case where my very senses reject their own evidence. Yet, mad am I not – and very surely do I not dream. But to-morrow I die, and to-day I would unburthen my soul. My immediate purpose is to place before the world, plainly, succinctly, and without comment, a series of mere household events. In their consequences, these events have terrified – have tortured – have destroyed me. Yet I will not attempt to expound them. To me, they have presented little but Horror – to many they will seem less terrible than barroques. Hereafter, perhaps, some intellect may be found which will reduce my phantasm to the common-place – some intellect more calm, more logical, and far less excitable than my own, which will perceive, in the circumstances I detail with awe, nothing more than an ordinary succession of very natural causes and effects.

From my infancy I was noted for the docility and humanity of my disposition. My tenderness of heart was even so conspicuous as to make me the jest of my companions. I was especially fond of animals, and was indulged by my parents with a great variety of pets. With these I spent most of my time, and never was so happy as when feeding and caressing them. This peculiarity of character grew with my growth, and in my manhood, I derived from it one of my principal sources of pleasure. To those who have cherished an affection for a faithful and sagacious dog, I need hardly be at the trouble of explaining the nature or the intensity of the gratification thus derivable. There is something in the unselfish and self-sacrificing love of a brute, which goes directly to the heart of him who has had frequent occasion to test the paltry friendship and gossamer fidelity of mere Man .

I married early, and was happy to find in my wife a disposition not uncongenial with my own. Observing my partiality for domestic pets, she lost no opportunity of procuring those of the most agreeable kind. We had birds, gold-fish, a fine dog, rabbits, a small monkey, and a cat .

This latter was a remarkably large and beautiful animal, entirely black, and sagacious to an astonishing degree. In speaking of his intelligence, my wife, who at heart was not a little tinctured with superstition, made frequent allusion to the ancient popular notion, which regarded all black cats as witches in disguise. Not that she was ever serious upon this point – and I mention the matter at all for no better reason than that it happens, just now, to be remembered.

Pluto – this was the cat’s name – was my favorite pet and playmate. I alone fed him, and he attended me wherever I went about the house. It was even with difficulty that I could prevent him from following me through the streets.

Our friendship lasted, in this manner, for several years, during which my general temperament and character – through the instrumentality of the Fiend Intemperance – had (I blush to confess it) experienced a radical alteration for the worse. I grew, day by day, more moody, more irritable, more regardless of the feelings of others. I suffered myself to use intemperate language to my wife. At length, I even offered her personal violence. My pets, of course, were made to feel the change in my disposition. I not only neglected, but ill-used them. For Pluto, however, I still retained sufficient regard to restrain me from maltreating him, as I made no scruple of maltreating the rabbits, the monkey, or even the dog, when by accident, or through affection, they came in my way. But my disease grew upon me – for what disease is like Alcohol! – and at length even Pluto, who was now becoming old, and consequently somewhat peevish – even Pluto began to experience the effects of my ill temper.

One night, returning home, much intoxicated, from one of my haunts about town, I fancied that the cat avoided my presence. I seized him; when, in his fright at my violence, he inflicted a slight wound upon my hand with his teeth. The fury of a demon instantly possessed me. I knew myself no longer. My original soul seemed, at once, to take its flight from my body and a more than fiendish malevolence, gin-nurtured, thrilled every fibre of my frame. I took from my waistcoat-pocket a pen-knife, opened it, grasped the poor beast by the throat, and deliberately cut one of its eyes from the socket! I blush, I burn, I shudder, while I pen the damnable atrocity.

When reason returned with the morning – when I had slept off the fumes of the night’s debauch – I experienced a sentiment half of horror, half of remorse, for the crime of which I had been guilty; but it was, at best, a feeble and equivocal feeling, and the soul remained untouched. I again plunged into excess, and soon drowned in wine all memory of the deed.

In the meantime the cat slowly recovered. The socket of the lost eye presented, it is true, a frightful appearance, but he no longer appeared to suffer any pain. He went about the house as usual, but, as might be expected, fled in extreme terror at my approach. I had so much of my old heart left, as to be at first grieved by this evident dislike on the part of a creature which had once so loved me. But this feeling soon gave place to irritation. And then came, as if to my final and irrevocable overthrow, the spirit of PERVERSENESS. Of this spirit philosophy takes no account. Yet I am not more sure that my soul lives, than I am that perverseness is one of the primitive impulses of the human heart – one of the indivisible primary faculties, or sentiments, which give direction to the character of Man. Who has not, a hundred times, found himself committing a vile or a silly action, for no other reason than because he knows he should not? Have we not a perpetual inclination, in the teeth of our best judgment, to violate that which is Law , merely because we understand it to be such? This spirit of perverseness, I say, came to my final overthrow. It was this unfathomable longing of the soul to vex itself – to offer violence to its own nature – to do wrong for the wrong’s sake only – that urged me to continue and finally to consummate the injury I had inflicted upon the unoffending brute. One morning, in cool blood, I slipped a noose about its neck and hung it to the limb of a tree; – hung it with the tears streaming from my eyes, and with the bitterest remorse at my heart; – hung it because I knew that it had loved me, and because I felt it had given me no reason of offence; – hung it because I knew that in so doing I was committing a sin – a deadly sin that would so jeopardize my immortal soul as to place it – if such a thing wore possible – even beyond the reach of the infinite mercy of the Most Merciful and Most Terrible God.

On the night of the day on which this cruel deed was done, I was aroused from sleep by the cry of fire. The curtains of my bed were in flames. The whole house was blazing. It was with great difficulty that my wife, a servant, and myself, made our escape from the conflagration. The destruction was complete. My entire worldly wealth was swallowed up, and I resigned myself thenceforward to despair.

I am above the weakness of seeking to establish a sequence of cause and effect, between the disaster and the atrocity. But I am detailing a chain of facts – and wish not to leave even a possible link imperfect. On the day succeeding the fire, I visited the ruins. The walls, with one exception, had fallen in. This exception was found in a compartment wall, not very thick, which stood about the middle of the house, and against which had rested the head of my bed. The plastering had here, in great measure, resisted the action of the fire – a fact which I attributed to its having been recently spread. About this wall a dense crowd were collected, and many persons seemed to be examining a particular portion of it with very minute and eager attention. The words “strange!” “singular!” and other similar expressions, excited my curiosity. I approached and saw, as if graven in bas relief upon the white surface, the figure of a gigantic cat. The impression was given with an accuracy truly marvellous. There was a rope about the animal’s neck.

When I first beheld this apparition – for I could scarcely regard it as less – my wonder and my terror were extreme. But at length reflection came to my aid. The cat, I remembered, had been hung in a garden adjacent to the house. Upon the alarm of fire, this garden had been immediately filled by the crowd – by some one of whom the animal must have been cut from the tree and thrown, through an open window, into my chamber. This had probably been done with the view of arousing me from sleep. The falling of other walls had compressed the victim of my cruelty into the substance of the freshly-spread plaster; the lime of which, with the flames, and the ammonia from the carcass, had then accomplished the portraiture as I saw it.

Although I thus readily accounted to my reason, if not altogether to my conscience, for the startling fact just detailed, it did not the less fail to make a deep impression upon my fancy. For months I could not rid myself of the phantasm of the cat; and, during this period, there came back into my spirit a half-sentiment that seemed, but was not, remorse. I went so far as to regret the loss of the animal, and to look about me, among the vile haunts which I now habitually frequented, for another pet of the same species, and of somewhat similar appearance, with which to supply its place.

One night as I sat, half stupified, in a den of more than infamy, my attention was suddenly drawn to some black object, reposing upon the head of one of the immense hogsheads of Gin, or of Rum, which constituted the chief furniture of the apartment. I had been looking steadily at the top of this hogshead for some minutes, and what now caused me surprise was the fact that I had not sooner perceived the object thereupon. I approached it, and touched it with my hand. It was a black cat – a very large one – fully as large as Pluto, and closely resembling him in every respect but one. Pluto had not a white hair upon any portion of his body; but this cat had a large, although indefinite splotch of white, covering nearly the whole region of the breast. Upon my touching him, he immediately arose, purred loudly, rubbed against my hand, and appeared delighted with my notice. This, then, was the very creature of which I was in search. I at once offered to purchase it of the landlord; but this person made no claim to it – knew nothing of it – had never seen it before.

I continued my caresses, and, when I prepared to go home, the animal evinced a disposition to accompany me. I permitted it to do so; occasionally stooping and patting it as I proceeded. When it reached the house it domesticated itself at once, and became immediately a great favorite with my wife.

For my own part, I soon found a dislike to it arising within me. This was just the reverse of what I had anticipated; but – I know not how or why it was – its evident fondness for myself rather disgusted and annoyed. By slow degrees, these feelings of disgust and annoyance rose into the bitterness of hatred. I avoided the creature; a certain sense of shame, and the remembrance of my former deed of cruelty, preventing me from physically abusing it. I did not, for some weeks, strike, or otherwise violently ill use it; but gradually – very gradually – I came to look upon it with unutterable loathing, and to flee silently from its odious presence, as from the breath of a pestilence.

What added, no doubt, to my hatred of the beast, was the discovery, on the morning after I brought it home, that, like Pluto, it also had been deprived of one of its eyes. This circumstance, however, only endeared it to my wife, who, as I have already said, possessed, in a high degree, that humanity of feeling which had once been my distinguishing trait, and the source of many of my simplest and purest pleasures.

With my aversion to this cat, however, its partiality for myself seemed to increase. It followed my footsteps with a pertinacity which it would be difficult to make the reader comprehend. Whenever I sat, it would crouch beneath my chair, or spring upon my knees, covering me with its loathsome caresses. If I arose to walk it would get between my feet and thus nearly throw me down, or, fastening its long and sharp claws in my dress, clamber, in this manner, to my breast. At such times, although I longed to destroy it with a blow, I was yet withheld from so doing, partly by a memory of my former crime, but chiefly – let me confess it at once – by absolute dread of the beast.

This dread was not exactly a dread of physical evil – and yet I should be at a loss how otherwise to define it. I am almost ashamed to own – yes, even in this felon’s cell, I am almost ashamed to own – that the terror and horror with which the animal inspired me, had been heightened by one of the merest chimaeras it would be possible to conceive. My wife had called my attention, more than once, to the character of the mark of white hair, of which I have spoken, and which constituted the sole visible difference between the strange beast and the one I had destroyed. The reader will remember that this mark, although large, had been originally very indefinite; but, by slow degrees – degrees nearly imperceptible, and which for a long time my Reason struggled to reject as fanciful – it had, at length, assumed a rigorous distinctness of outline. It was now the representation of an object that I shudder to name – and for this, above all, I loathed, and dreaded, and would have rid myself of the monster had I dared – it was now, I say, the image of a hideous – of a ghastly thing – of the GALLOWS ! – oh, mournful and terrible engine of Horror and of Crime – of Agony and of Death !

And now was I indeed wretched beyond the wretchedness of mere Humanity. And a brute beast – whose fellow I had contemptuously destroyed – a brute beast to work out for me – for me a man, fashioned in the image of the High God – so much of insufferable wo! Alas! neither by day nor by night knew I the blessing of Rest any more! During the former the creature left me no moment alone; and, in the latter, I started, hourly, from dreams of unutterable fear, to find the hot breath of the thing upon my face, and its vast weight – an incarnate Night-Mare that I had no power to shake off – incumbent eternally upon my heart!

Beneath the pressure of torments such as these, the feeble remnant of the good within me succumbed. Evil thoughts became my sole intimates – the darkest and most evil of thoughts. The moodiness of my usual temper increased to hatred of all things and of all mankind; while, from the sudden, frequent, and ungovernable outbursts of a fury to which I now blindly abandoned myself, my uncomplaining wife, alas! was the most usual and the most patient of sufferers.

One day she accompanied me, upon some household errand, into the cellar of the old building which our poverty compelled us to inhabit. The cat followed me down the steep stairs, and, nearly throwing me headlong, exasperated me to madness. Uplifting an axe, and forgetting, in my wrath, the childish dread which had hitherto stayed my hand, I aimed a blow at the animal which, of course, would have proved instantly fatal had it descended as I wished. But this blow was arrested by the hand of my wife. Goaded, by the interference, into a rage more than demoniacal, I withdrew my arm from her grasp and buried the axe in her brain. She fell dead upon the spot, without a groan.

This hideous murder accomplished, I set myself forthwith, and with entire deliberation, to the task of concealing the body. I knew that I could not remove it from the house, either by day or by night, without the risk of being observed by the neighbors. Many projects entered my mind. At one period I thought of cutting the corpse into minute fragments, and destroying them by fire. At another, I resolved to dig a grave for it in the floor of the cellar. Again, I deliberated about casting it in the well in the yard – about packing it in a box, as if merchandize, with the usual arrangements, and so getting a porter to take it from the house. Finally I hit upon what I considered a far better expedient than either of these. I determined to wall it up in the cellar – as the monks of the middle ages are recorded to have walled up their victims.

For a purpose such as this the cellar was well adapted. Its walls were loosely constructed, and had lately been plastered throughout with a rough plaster, which the dampness of the atmosphere had prevented from hardening. Moreover, in one of the walls was a projection, caused by a false chimney, or fireplace, that had been filled up, and made to resemble the red of the cellar. I made no doubt that I could readily displace the bricks at this point, insert the corpse, and wall the whole up as before, so that no eye could detect any thing suspicious. And in this calculation I was not deceived. By means of a crow-bar I easily dislodged the bricks, and, having carefully deposited the body against the inner wall, I propped it in that position, while, with little trouble, I re-laid the whole structure as it originally stood. Having procured mortar, sand, and hair, with every possible precaution, I prepared a plaster which could not be distinguished from the old, and with this I very carefully went over the new brickwork. When I had finished, I felt satisfied that all was right. The wall did not present the slightest appearance of having been disturbed. The rubbish on the floor was picked up with the minutest care. I looked around triumphantly, and said to myself – “Here at least, then, my labor has not been in vain.”

My next step was to look for the beast which had been the cause of so much wretchedness; for I had, at length, firmly resolved to put it to death. Had I been able to meet with it, at the moment, there could have been no doubt of its fate; but it appeared that the crafty animal had been alarmed at the violence of my previous anger, and forebore to present itself in my present mood. It is impossible to describe, or to imagine, the deep, the blissful sense of relief which the absence of the detested creature occasioned in my bosom. It did not make its appearance during the night – and thus for one night at least, since its introduction into the house, I soundly and tranquilly slept; aye, slept even with the burden of murder upon my soul!

The second and the third day passed, and still my tormentor came not. Once again I breathed as a freeman. The monster, in terror, had fled the premises forever! I should behold it no more! My happiness was supreme! The guilt of my dark deed disturbed me but little. Some few inquiries had been made, but these had been readily answered. Even a search had been instituted – but of course nothing was to be discovered. I looked upon my future felicity as secured.

Upon the fourth day of the assassination, a party of the police came, very unexpectedly, into the house, and proceeded again to make rigorous investigation of the premises. Secure, however, in the inscrutability of my place of concealment, I felt no embarrassment whatever. The officers bade me accompany them in their search. They left no nook or corner unexplored. At length, for the third or fourth time, they descended into the cellar. I quivered not in a muscle. My heart beat calmly as that of one who slumbers in innocence. I walked the cellar from end to end. I folded my arms upon my bosom, and roamed easily to and fro. The police were thoroughly satisfied and prepared to depart. The glee at my heart was too strong to be restrained. I burned to say if but one word, by way of triumph, and to render doubly sure their assurance of my guiltlessness.

“Gentlemen,” I said at last, as the party ascended the steps, “I delight to have allayed your suspicions. I wish you all health, and a little more courtesy. By the bye, gentlemen, this – this is a very well constructed house.” [In the rabid desire to say something easily, I scarcely knew what I uttered at all.] – “I may say an excellently well constructed house. These walls are you going, gentlemen? – these walls are solidly put together;” and here, through the mere phrenzy of bravado, I rapped heavily, with a cane which I held in my hand, upon that very portion of the brick-work behind which stood the corpse of the wife of my bosom.

But may God shield and deliver me from the fangs of the Arch-Fiend ! No sooner had the reverberation of my blows sunk into silence, than I was answered by a voice from within the tomb! – by a cry, at first muffled and broken, like the sobbing of a child, and then quickly swelling into one long, loud, and continuous scream, utterly anomalous and inhuman – a howl – a wailing shriek, half of horror and half of triumph, such as might have arisen only out of hell, conjointly from the throats of the dammed in their agony and of the demons that exult in the damnation.

Of my own thoughts it is folly to speak. Swooning, I staggered to the opposite wall. For one instant the party upon the stairs remained motionless, through extremity of terror and of awe. In the next, a dozen stout arms were toiling at the wall. It fell bodily. The corpse, already greatly decayed and clotted with gore, stood erect before the eyes of the spectators. Upon its head, with red extended mouth and solitary eye of fire, sat the hideous beast whose craft had seduced me into murder, and whose informing voice had consigned me to the hangman. I had walled the monster up within the tomb!

Edgar Allan Poe: The Black Cat

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

.jpg)

Auf der Galerie

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Wenn irgendeine hinfällige, lungensüchtige Kunstreiterin in der Manege auf schwankendem Pferd vor einem unermüdlichen Publikum vom peitschenschwingenden erbarmungslosen Chef monatelang ohne Unterbrechung im Kreise rundum getrieben würde, auf dem Pferde schwirrend, Küsse werfend, in der Taille sich wiegend, und wenn dieses Spiel unter dem nichtaussetzenden Brausen des Orchesters und der Ventilatoren in die immerfort weiter sich öffnende graue Zukunft sich fortsetzte, begleitet vom vergehenden und neu anschwellenden Beifallsklatschen der Hände, die eigentlich Dampfhämmer sind – vielleicht eilte dann ein junger Galeriebesucher die lange Treppe durch alle Ränge hinab, stürzte in die Manege, riefe das: Halt! durch die Fanfaren des immer sich anpassenden Orchesters.

Da es aber nicht so ist; eine schöne Dame, weiß und rot, hereinfliegt, zwischen den Vorhängen, welche die stolzen Livrierten vor ihr öffnen; der Direktor, hingebungsvoll ihre Augen suchend, in Tierhaltung ihr entgegenatmet; vorsorglich sie auf den Apfelschimmel hebt, als wäre sie seine über alles geliebte Enkelin, die sich auf gefährliche Fahrt begibt; sich nicht entschließen kann, das Peitschenzeichen zu geben; schließlich in Selbstüberwindung es knallend gibt; neben dem Pferde mit offenem Munde einherläuft; die Sprünge der Reiterin scharfen Blickes verfolgt; ihre Kunstfertigkeit kaum begreifen kann; mit englischen Ausrufen zu warnen versucht; die reifenhaltenden Reitknechte wütend zu peinlichster Achtsamkeit ermahnt; vor dem großen Saltomortale das Orchester mit aufgehobenen Händen beschwört, es möge schweigen; schließlich die Kleine vom zitternden Pferde hebt, auf beide Backen küßt und keine Huldigung des Publikums für genügend erachtet; während sie selbst, von ihm gestützt, hoch auf den Fußspitzen, vom Staub umweht, mit ausgebreiteten Armen, zurückgelehntem Köpfchen ihr Glück mit dem ganzen Zirkus teilen will – da dies so ist, legt der Galeriebesucher das Gesicht auf die Brüstung und, im Schlußmarsch wie in einem schweren Traum versinkend, weint er, ohne es zu wissen.

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 206

Ik zei dat sommige brieven en stukken my belang inboezemden als teekenen des tyds. Enkelen daarvan zal ik behandelen in m’n ideen. E.g:

Voor eenige dagen ontving ik ‘n brochure: ‘Opmerkingen en Gedachten over zaken van algemeen belang, door F.P.J. Mulder en C. de Gavere, studenten.’ De schryvers boden my dat met ‘n vriendelyk woordjen op den omslag aan.

Ik ontvang veel zulke geschenken – eens-voor-al dank! – en heb niet altyd loisir of lust den zenders ‘n brief te schryven. Ditmaal echter had ik reden om uitdrukkelyk te bedanken. Ik was namelyk getroffèn door twee byzonderheden. Ten eerste de schryvers waren studenten, dat is: ze behooren, wat leeftyd en werkkring aangaat, tot het Jonge Nederland, tot de adelborsten op ‘t schip dat bestemd is bres te schieten in de wallen van ‘t vermolmd roofslot ‘aan den oever der zee, tusschen Oostvriesland en de Schelde’ en ten-tweede: die jongelui staken myn vaan uit. Zy zeggen: ‘onze leus is vryheid en waarheid, liberaliteit, en humaniteit; onze vyanden vinden wy in despotisme en bygeloof, slaperigheid en dweepery.’

Die leus is ook myn leus. Die vyanden zyn ook myn vyanden.

Maar dit alleen zou niet genoeg zyn. ‘t Getal bestryders van die vyanden is Legio… binnen’skamers.

‘t Getal vaantjes die myn kleur dragen, zou als de pylen van Xerxes’ leger de zon verduisteren; wanneer men ze ophief by ‘t licht van die zon, in-stee van ze saamgerold te bewaren in ‘n net foudraaltje, tusschen de voering van z’n rokspand, om ze schoorhandend en ter-sluik even te ontrollen in ‘n nauw vertrekje, ongezien, met gegrendelde deur, gesloten blinden, by ‘n nachtpitje…

Welnu, die beide jonge-lieden ontrollen die vaan, en op hun krygsroep: à la rescousse! was myn plicht te antwoorden: hier ben ik! En dat heb ik geantwoord.

Maar zie, ‘n paar dagen later ontvang ik ‘n brief van twee andere studenten, die my – wat vorm en inkleeding aangaat, zeer beleefd – vragen of ‘t waar is dat ik aan die twee schandvlekken hunner hoogeschool ‘n brief zou geschreven hebben, waarin onder anderen voorkomt het woord: beste kerels?

‘Dat vertelt men hier… wy houden ‘t voor laster… wy gelooven ‘t niet voor gyzelf dat erkent, zwart op wit.’

Als ik dus met rooden inkt schreef: ja, ik heb ‘t gezegd! zouden ze ‘t nog niet gelooven.

‘We hebben respekt voor uw kunsttalent…

Dat maakt me den indruk alsof men aan Garibaldi ‘n kompliment maakte over z’n juiste denkbeelden omtrent de garnizoensdienst. Ik heb niets te maken met kunst, kunstigheid, kunstelary, gekunsteldheid, kunstenmaken, en wat dies meer zy.

‘Voor uw kunsttalent, uw waarheidsliefde, uw rechtvaardigheid, zooals we die meenden optemerken in uw werken…

Ei, jongelui, hebt ge dat meenen optemerken in m’n werken! Ei, ei!

Daar is ‘n man die eer, aanzien, toekomst, smyt in ‘t aangezicht der misdadige regeering van ‘n verbasterd volk…

Daar is ‘n man die ‘t leven van zich en de zynen niet acht, waar de prys van dat leven deelgenootschap wezen zou aan de schande van Nederland…

Daar is ‘n man die als Curtius neerspringt in de gapende kloof op ‘t Forum, doch in den sprong vrouw en kinderen meeneemt, of ‘t ook soms te weinig ware, ‘n romeinsch ridder alleen…

Daar is ‘n man die elken dag wordt weggeleid in de woestyn en op de tinne des tempels… die elken dag de koninkryken dezer aarde voor zich ziet uitgespreid als wat lokäas voor z’n afval… ‘n man, die elken dag den Satan wegstoot om te doen ‘het woord dat geschreven staat’ in z’n hart…

Daar is ‘n man die den langen weg kiest naar Golgotha… niet om dáár te worden gekruist alleen, maar om te worden gekruist by elken voetstap… weder en weder, en telkens weder, ten-pleiziere van Schmoel en konsorten…

Daar is ‘n man die dat alles deed, doet, draagde en draagt, leed en lydt om zyner zaak’s wille…

Om-den-wille van het recht…

En dan komen er ‘n paar…

‘Uwe werken zyn door de respektabelste jongelui gelezen en herlezen…

Dan komen er ‘n paar ‘respektabelste’ jongelui dien man vertellen dat ze uit z’n werken meenden te hebben opgemerkt dat hy liefde had voor waarheid en rechtvaardigheid!

Ei, respektabelste jongelui, hebt ge dat inderdaad meenen te merken?

Schaamt u!

En gy, zoogenaamde hoogleeraren onzer zoogenaamde hoogescholen, treedt af, en neemt patent als laagleeraren die ge zyt. ‘t Is uw schuld, uw schuld, uw grootste schuld, jeugdbedervers!

Hoe, ge leert onze jongelingschap preeken en bidden, pleiten en ontleeden, taalknoeiers en prozodie, wetuitleggen en schriftgeleerdheid… en by dat alles – neen, dóór dat alles – vergeet ge hun te leeren wat ‘n mensch is? Uw ‘respektabelste’ jongelui praten van kunsttalent tegen iemand die nooit dacht aan kunst? Ze zien slechts ‘n boek, ‘n menigte letters en woorden in zekere volgorde gedrukt op papier, in de protesten tegen Nederlandsche schande en Nederlandsche misdaad? Ze hebben van u slechts geleerd klanken en frazen te beoordeelen – en hoe! – waar daden geschied zyn? Treed af, zeg ik u, weest eerlyk en doet afstand van de anders zoo schoone roeping om meetewerken tot de vervulling der Spes Patriae die voor ‘n groot deel in uwe handen is… helaas!

Hoe, ge praat, preekt, katechizeert, leest diktaten voor van ‘t jaar nul, en by dat alles – weer: dóór dat alles – vergeet ge dat er maar één bron is, één bron van groote gedachten: het hart?

Schande over u, schriftgeleerden!

En gy ‘respektabelste’ jongelui, die meende optemerken dat ik liefde had voor waarheid en rechtvaardigheid…

Onder erkenning uwer verwonderlyke scherpzichtigheid, en om u te overtuigen dat uw meening redelyk juist is, geef ik u den raad uw alma mater vaarwel te zeggen, en plaats te nemen in de een of andere kruieniery. Misschien ook is er ‘n vakature by de drukkery van ‘t traktaatgenootschap. Daar kunt ge u vergasten op letters, woorden, frazen… zonder eind.

En in dien winkel, of op die drukkery, tusschen ‘t plakken van ‘n paar peperhuisjes, of ‘t zetten van twee vodjes over ‘Zoendood’ en ‘Genade’… tusschen die bezigheid in, als ge wat tyd hebt:

Schaamt u!

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature