Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

photo kempis.nl

Esther Porcelijn

We saw your boobs

Seth Macfarlane (maker van tekenfilmseries Family Guy en American Dad) heeft een lied gezongen bij de Oscaruitreiking afgelopen zondag (24 februari 2013). Het lied dat hij zong was een eigen creatie genaamd: “We saw your Boobs”

In dat lied gaat hij alle actrices af waarvan hij de borsten heeft gezien in films.

Dit alles lijkt vrij onschuldig ware het niet dat hij de woede van veel actrices hiermee op de hals heeft gehaald. Let wel: Dit zijn actrices die welwillend en volledig vrijwillig hun borsten hebben getoond op film. Zelfs levend humoristisch fossiel Jane Fonda is boos, dit is haar statement: “What I really didn’t like was the song and dance number about seeing actresses boobs. I agree with someone who said, if they want to stoop to that, why not list all the penises we’ve seen? Better yet, remember that this is a telecast seen around the world watched by families with their children and to many this is neither appropriate or funny. I also didn’t like the remark made about Quvenzhane and Clooney, or the stuff out of Ted’s mouth and all the comments about what women do to get thin for their dresses. Waaaay too much stuff about women and bodies, as though that’s what defines us.” (janefonda.com/janes-blog-posts/)

Andere statements van actrices zijn al verzameld.

Na dit te hebben gelezen twijfelde ik even of de boze vrouwen niet toch een punt hadden maar ik moet toch echt concluderen dat dit niet zo is.

Stel je even voor dat je zelf een actrice bent. Je leest het script of scenario nog maanden of jaren voordat de film daadwerkelijk wordt opgenomen, en in een regieaanwijzing staat: ‘kleedt zich uit, staat met ontbloot bovenlichaam voor het raam, medium-shot van bovenlichaam, tegenspeler staat achter haar en omhelst haar innig.”

Dan weet je toch wat de consequentie is? Duizenden of misschien wel miljoenen mannen die zich verlekkeren aan je borsten. Youtube filmpjes die op repeat staan tijdens studentenhuis-feesten.

Goed, er is wat voor te zeggen als de nadruk van de Oscars al te veel ligt op het vrouwelijk lichaam maar de Oscaruitreiking is toch, behalve een erkenning van talent en goede films, ook een vleeskeuring? De vrouwen doffen zich op, kleden zich prachtig, trainen weken om er helemaal nonchie slank uit te zien. En dan feministisch gaan doen om een puberaal liedje van iemand waarvan je zo’n liedje kan verwachten. En dan nog over films waar die actrices miljoenen aan verdienen, mede door de blote borstenscènes.

Ben ik nu een antifeminist? Ik vind het filmpje namelijk enorm grappig want het verwoordt wat elke man stiekem denkt als hij de borsten van Charlize Theron heeft gezien: “Ha! Betrapt!” De scènes zijn voyeuristisch gefilmd met dit doel voor ogen. Nou fucking en? Er is zelfs een Mannenversie gemaakt van het nummer.

Ik weet dat grappen over vrouwen erg makkelijk worden gemaakt, tot op het punt dat ook ik mij ongemakkelijk voel als moderne vrouw die niet beter weet dan dat mannen en vrouwen gelijkwaardig zijn. Ook ik merk soms dat seksgrappen net iets te snel worden gemaakt, en als iemand vijf keer dezelfde grap maakt dan is het op een gegeven moment geen grap meer.

Maar dit voorbeeld is voor mij niet kwetsend, denigrerend of aanstootgevend, ik vind het grappig.

Hypocriet dekt de lading zelfs niet helemaal. Of zie ik dit verkeerd?

Esther Porcelijn: 01-03-2013 Univers Blog

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

Clay

The matron had given her leave to go out as soon as the women’s tea was over and Maria looked forward to her evening out. The kitchen was spick and span: the cook said you could see yourself in the big copper boilers. The fire was nice and bright and on one of the side-tables were four very big barmbracks. These barmbracks seemed uncut; but if you went closer you would see that they had been cut into long thick even slices and were ready to be handed round at tea. Maria had cut them herself.

Maria was a very, very small person indeed but she had a very long nose and a very long chin. She talked a little through her nose, always soothingly: “Yes, my dear,” and “No, my dear.” She was always sent for when the women quarrelled Over their tubs and always succeeded in making peace. One day the matron had said to her:

“Maria, you are a veritable peace-maker!”

And the sub-matron and two of the Board ladies had heard the compliment. And Ginger Mooney was always saying what she wouldn’t do to the dummy who had charge of the irons if it wasn’t for Maria. Everyone was so fond of Maria.

The women would have their tea at six o’clock and she would be able to get away before seven. From Ballsbridge to the Pillar, twenty minutes; from the Pillar to Drumcondra, twenty minutes; and twenty minutes to buy the things. She would be there before eight. She took out her purse with the silver clasps and read again the words A Present from Belfast. She was very fond of that purse because Joe had brought it to her five years before when he and Alphy had gone to Belfast on a Whit-Monday trip. In the purse were two half-crowns and some coppers. She would have five shillings clear after paying tram fare. What a nice evening they would have, all the children singing! Only she hoped that Joe wouldn’t come in drunk. He was so different when he took any drink.

Often he had wanted her to go and live with them;-but she would have felt herself in the way (though Joe’s wife was ever so nice with her) and she had become accustomed to the life of the laundry. Joe was a good fellow. She had nursed him and Alphy too; and Joe used often say:

“Mamma is mamma but Maria is my proper mother.”

After the break-up at home the boys had got her that position in the Dublin by Lamplight laundry, and she liked it. She used to have such a bad opinion of Protestants but now she thought they were very nice people, a little quiet and serious, but still very nice people to live with. Then she had her plants in the conservatory and she liked looking after them. She had lovely ferns and wax-plants and, whenever anyone came to visit her, she always gave the visitor one or two slips from her conservatory. There was one thing she didn’t like and that was the tracts on the walks; but the matron was such a nice person to deal with, so genteel.

When the cook told her everything was ready she went into the women’s room and began to pull the big bell. In a few minutes the women began to come in by twos and threes, wiping their steaming hands in their petticoats and pulling down the sleeves of their blouses over their red steaming arms. They settled down before their huge mugs which the cook and the dummy filled up with hot tea, already mixed with milk and sugar in huge tin cans. Maria superintended the distribution of the barmbrack and saw that every woman got her four slices. There was a great deal of laughing and joking during the meal. Lizzie Fleming said Maria was sure to get the ring and, though Fleming had said that for so many Hallow Eves, Maria had to laugh and say she didn’t want any ring or man either; and when she laughed her grey-green eyes sparkled with disappointed shyness and the tip of her nose nearly met the tip of her chin. Then Ginger Mooney lifted her mug of tea and proposed Maria’s health while all the other women clattered with their mugs on the table, and said she was sorry she hadn’t a sup of porter to drink it in. And Maria laughed again till the tip of her nose nearly met the tip of her chin and till her minute body nearly shook itself asunder because she knew that Mooney meant well though, of course, she had the notions of a common woman.

But wasn’t Maria glad when the women had finished their tea and the cook and the dummy had begun to clear away the tea- things! She went into her little bedroom and, remembering that the next morning was a mass morning, changed the hand of the alarm from seven to six. Then she took off her working skirt and her house-boots and laid her best skirt out on the bed and her tiny dress-boots beside the foot of the bed. She changed her blouse too and, as she stood before the mirror, she thought of how she used to dress for mass on Sunday morning when she was a young girl; and she looked with quaint affection at the diminutive body which she had so often adorned, In spite of its years she found it a nice tidy little body.

When she got outside the streets were shining with rain and she was glad of her old brown waterproof. The tram was full and she had to sit on the little stool at the end of the car, facing all the people, with her toes barely touching the floor. She arranged in her mind all she was going to do and thought how much better it was to be independent and to have your own money in your pocket. She hoped they would have a nice evening. She was sure they would but she could not help thinking what a pity it was Alphy and Joe were not speaking. They were always falling out now but when they were boys together they used to be the best of friends: but such was life.

She got out of her tram at the Pillar and ferreted her way quickly among the crowds. She went into Downes’s cake-shop but the shop was so full of people that it was a long time before she could get herself attended to. She bought a dozen of mixed penny cakes, and at last came out of the shop laden with a big bag. Then she thought what else would she buy: she wanted to buy something really nice. They would be sure to have plenty of apples and nuts. It was hard to know what to buy and all she could think of was cake. She decided to buy some plumcake but Downes’s plumcake had not enough almond icing on top of it so she went over to a shop in Henry Street. Here she was a long time in suiting herself and the stylish young lady behind the counter, who was evidently a little annoyed by her, asked her was it wedding-cake she wanted to buy. That made Maria blush and smile at the young lady; but the young lady took it all very seriously and finally cut a thick slice of plumcake, parcelled it up and said:

“Two-and-four, please.”

She thought she would have to stand in the Drumcondra tram because none of the young men seemed to notice her but an elderly gentleman made room for her. He was a stout gentleman and he wore a brown hard hat; he had a square red face and a greyish moustache. Maria thought he was a colonel-looking gentleman and she reflected how much more polite he was than the young men who simply stared straight before them. The gentleman began to chat with her about Hallow Eve and the rainy weather. He supposed the bag was full of good things for the little ones and said it was only right that the youngsters should enjoy themselves while they were young. Maria agreed with him and favoured him with demure nods and hems. He was very nice with her, and when she was getting out at the Canal Bridge she thanked him and bowed, and he bowed to her and raised his hat and smiled agreeably, and while she was going up along the terrace, bending her tiny head under the rain, she thought how easy it was to know a gentleman even when he has a drop taken.

Everybody said: “0, here’s Maria!” when she came to Joe’s house. Joe was there, having come home from business, and all the children had their Sunday dresses on. There were two big girls in from next door and games were going on. Maria gave the bag of cakes to the eldest boy, Alphy, to divide and Mrs. Donnelly said it was too good of her to bring such a big bag of cakes and made all the children say:

“Thanks, Maria.”

But Maria said she had brought something special for papa and mamma, something they would be sure to like, and she began to look for her plumcake. She tried in Downes’s bag and then in the pockets of her waterproof and then on the hallstand but nowhere could she find it. Then she asked all the children had any of them eaten it — by mistake, of course — but the children all said no and looked as if they did not like to eat cakes if they were to be accused of stealing. Everybody had a solution for the mystery and Mrs. Donnelly said it was plain that Maria had left it behind her in the tram. Maria, remembering how confused the gentleman with the greyish moustache had made her, coloured with shame and vexation and disappointment. At the thought of the failure of her little surprise and of the two and fourpence she had thrown away for nothing she nearly cried outright.

But Joe said it didn’t matter and made her sit down by the fire. He was very nice with her. He told her all that went on in his office, repeating for her a smart answer which he had made to the manager. Maria did not understand why Joe laughed so much over the answer he had made but she said that the manager must have been a very overbearing person to deal with. Joe said he wasn’t so bad when you knew how to take him, that he was a decent sort so long as you didn’t rub him the wrong way. Mrs. Donnelly played the piano for the children and they danced and sang. Then the two next-door girls handed round the nuts. Nobody could find the nutcrackers and Joe was nearly getting cross over it and asked how did they expect Maria to crack nuts without a nutcracker. But Maria said she didn’t like nuts and that they weren’t to bother about her. Then Joe asked would she take a bottle of stout and Mrs. Donnelly said there was port wine too in the house if she would prefer that. Maria said she would rather they didn’t ask her to take anything: but Joe insisted.

So Maria let him have his way and they sat by the fire talking over old times and Maria thought she would put in a good word for Alphy. But Joe cried that God might strike him stone dead if ever he spoke a word to his brother again and Maria said she was sorry she had mentioned the matter. Mrs. Donnelly told her husband it was a great shame for him to speak that way of his own flesh and blood but Joe said that Alphy was no brother of his and there was nearly being a row on the head of it. But Joe said he would not lose his temper on account of the night it was and asked his wife to open some more stout. The two next-door girls had arranged some Hallow Eve games and soon everything was merry again. Maria was delighted to see the children so merry and Joe and his wife in such good spirits. The next-door girls put some saucers on the table and then led the children up to the table, blindfold. One got the prayer-book and the other three got the water; and when one of the next-door girls got the ring Mrs. Donnelly shook her finger at the blushing girl as much as to say: 0, I know all about it! They insisted then on blindfolding Maria and leading her up to the table to see what she would get; and, while they were putting on the bandage, Maria laughed and laughed again till the tip of her nose nearly met the tip of her chin.

They led her up to the table amid laughing and joking and she put her hand out in the air as she was told to do. She moved her hand about here and there in the air and descended on one of the saucers. She felt a soft wet substance with her fingers and was surprised that nobody spoke or took off her bandage. There was a pause for a few seconds; and then a great deal of scuffling and whispering. Somebody said something about the garden, and at last Mrs. Donnelly said something very cross to one of the next-door girls and told her to throw it out at once: that was no play. Maria understood that it was wrong that time and so she had to do it over again: and this time she got the prayer-book.

After that Mrs. Donnelly played Miss McCloud’s Reel for the children and Joe made Maria take a glass of wine. Soon they were all quite merry again and Mrs. Donnelly said Maria would enter a convent before the year was out because she had got the prayer-book. Maria had never seen Joe so nice to her as he was that night, so full of pleasant talk and reminiscences. She said they were all very good to her.

At last the children grew tired and sleepy and Joe asked Maria would she not sing some little song before she went, one of the old songs. Mrs. Donnelly said “Do, please, Maria!” and so Maria had to get up and stand beside the piano. Mrs. Donnelly bade the children be quiet and listen to Maria’s song. Then she played the prelude and said “Now, Maria!” and Maria, blushing very much began to sing in a tiny quavering voice. She sang I Dreamt that I Dwelt, and when she came to the second verse she sang again:

I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls With vassals and serfs at my side, And of all who assembled within those walls That I was the hope and the pride.

I had riches too great to count; could boast Of a high ancestral name, But I also dreamt, which pleased me most, That you loved me still the same.

But no one tried to show her her mistake; and when she had ended her song Joe was very much moved. He said that there was no time like the long ago and no music for him like poor old Balfe, whatever other people might say; and his eyes filled up so much with tears that he could not find what he was looking for and in the end he had to ask his wife to tell him where the corkscrew was.

James Joyce stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Joyce, James, Joyce, James

photo jef van kempen

Esther Porcelijn

Te vroeg voor chips

Het gaat zo beginnen, het is bijna op!

Zou iemand komen vertellen over slagschepen

Over hoe we met problemen dwepen?

Over wartaal, dansen en een mop?

Of over crème-bruléé of taartbak-tips!

‘t Is niet dat ik daar zin in heb hoor

Zegt Lidy tegen haar man, Theodoor.

Maar het is te laat voor muesli en te vroeg voor chips.

Het is rustig in de rest van het huis

De kat krabt aan een paal

Iedereen wacht op het verhaal

Van een man en zijn circusmuis

“Wat jij schat?” port Lidy aan

“Wat is het dat jij wil horen”

Hmm. Iets over dat Ajax heeft verloren.

Of het verliezen van een baan.

Ach lieverd, boeiend hoor!

maar dat komt morgen misschien

Nu gaat het over hoe mensen kunst zien

En ik hoef pas later naar kantoor!

De telefoon gaat. Lidy wiebelt even

Hé nu liever niet, geen crisis geen zin

Geen oplossingen, geen spanning in ’t gezin

Geen werk, daar is niets te beleven

Theodoor slaat een arm om haar heen

Legt zijn andere hand op haar been.

Boze telefoontjes moeten wachten

Ook de zee golft even niet, en geen van de natuurkrachten

Ik kan nu niet komen delegeren, tot mijn spijt

De wasmachine heeft geen toeren

De bouwvakkers staken het loeren

De AEX staat stil, want ja, koffietijd!

Op 7 Maart 2013 was Esther Porcelijn te gast bij het programma Koffietijd op RTL4 naar aanleiding van het winnen van de Hollands Maandblad aanmoedigingsprijs voor poëzie. Na een kort interview droeg zij een speciaal voor koffietijd geschreven gedicht voor.

Esther Porcelijn poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

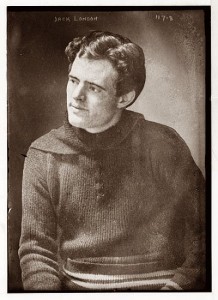

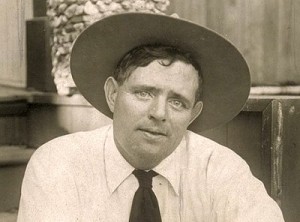

Jack London

(1876-1916)

The Tears of Ah Kim

There was a great noise and racket, but no scandal, in Honolulu’s

Chinatown. Those within hearing distance merely shrugged their

shoulders and smiled tolerantly at the disturbance as an affair of

accustomed usualness. “What is it?” asked Chin Mo, down with a

sharp pleurisy, of his wife, who had paused for a second at the

open window to listen.

“Only Ah Kim,” was her reply. “His mother is beating him again.”

The fracas was taking place in the garden, behind the living rooms

that were at the back of the store that fronted on the street with

the proud sign above: AH KIM COMPANY, GENERAL MERCHANDISE. The

garden was a miniature domain, twenty feet square, that somehow

cunningly seduced the eye into a sense and seeming of illimitable

vastness. There were forests of dwarf pines and oaks, centuries

old yet two or three feet in height, and imported at enormous care

and expense. A tiny bridge, a pace across, arched over a miniature

river that flowed with rapids and cataracts from a miniature lake

stocked with myriad-finned, orange-miracled goldfish that in

proportion to the lake and landscape were whales. On every side

the many windows of the several-storied shack-buildings looked

down. In the centre of the garden, on the narrow gravelled walk

close beside the lake Ah Kim was noisily receiving his beating.

No Chinese lad of tender and beatable years was Ah Kim. His was

the store of Ah Kim Company, and his was the achievement of

building it up through the long years from the shoestring of

savings of a contract coolie labourer to a bank account in four

figures and a credit that was gilt edged. An even half-century of

summers and winters had passed over his head, and, in the passing,

fattened him comfortably and snugly. Short of stature, his full

front was as rotund as a water-melon seed. His face was moon-

faced. His garb was dignified and silken, and his black-silk

skull-cap with the red button atop, now, alas! fallen on the

ground, was the skull-cap worn by the successful and dignified

merchants of his race.

But his appearance, in this moment of the present, was anything but

dignified. Dodging and ducking under a rain of blows from a bamboo

cane, he was crouched over in a half-doubled posture. When he was

rapped on the knuckles and elbows, with which he shielded his face

and head, his winces were genuine and involuntary. From the many

surrounding windows the neighbourhood looked down with placid

enjoyment.

And she who wielded the stick so shrewdly from long practice!

Seventy-four years old, she looked every minute of her time. Her

thin legs were encased in straight-lined pants of linen stiff-

textured and shiny-black. Her scraggly grey hair was drawn

unrelentingly and flatly back from a narrow, unrelenting forehead.

Eyebrows she had none, having long since shed them. Her eyes, of

pin-hole tininess, were blackest black. She was shockingly

cadaverous. Her shrivelled forearm, exposed by the loose sleeve,

possessed no more of muscle than several taut bowstrings stretched

across meagre bone under yellow, parchment-like skin. Along this

mummy arm jade bracelets shot up and down and clashed with every

blow.

“Ah!” she cried out, rhythmically accenting her blows in series of

three to each shrill observation. “I forbade you to talk to Li

Faa. To-day you stopped on the street with her. Not an hour ago.

Half an hour by the clock you talked.–What is that?”

“It was the thrice-accursed telephone,” Ah Kim muttered, while she

suspended the stick to catch what he said. “Mrs. Chang Lucy told

you. I know she did. I saw her see me. I shall have the

telephone taken out. It is of the devil.”

“It is a device of all the devils,” Mrs. Tai Fu agreed, taking a

fresh grip on the stick. “Yet shall the telephone remain. I like

to talk with Mrs. Chang Lucy over the telephone.”

“She has the eyes of ten thousand cats,” quoth Ah Kim, ducking and

receiving the stick stinging on his knuckles. “And the tongues of

ten thousand toads,” he supplemented ere his next duck.

“She is an impudent-faced and evil-mannered hussy,” Mrs. Tai Fu

accented.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy was ever that,” Ah Kim murmured like the dutiful

son he was.

“I speak of Li Faa,” his mother corrected with stick emphasis.

“She is only half Chinese, as you know. Her mother was a shameless

kanaka. She wears skirts like the degraded haole women–also

corsets, as I have seen for myself. Where are her children? Yet

has she buried two husbands.”

“The one was drowned, the other kicked by a horse,” Ah Kim

qualified.

“A year of her, unworthy son of a noble father, and you would

gladly be going out to get drowned or be kicked by a horse.”

Subdued chucklings and laughter from the window audience applauded

her point.

“You buried two husbands yourself, revered mother,” Ah Kim was

stung to retort.

“I had the good taste not to marry a third. Besides, my two

husbands died honourably in their beds. They were not kicked by

horses nor drowned at sea. What business is it of our neighbours

that you should inform them I have had two husbands, or ten, or

none? You have made a scandal of me, before all our neighbours,

and for that I shall now give you a real beating.”

Ah Kim endured the staccato rain of blows, and said when his mother

paused, breathless and weary:

“Always have I insisted and pleaded, honourable mother, that you

beat me in the house, with the windows and doors closed tight, and

not in the open street or the garden open behind the house.

“You have called this unthinkable Li Faa the Silvery Moon Blossom,”

Mrs. Tai Fu rejoined, quite illogically and femininely, but with

utmost success in so far as she deflected her son from continuance

of the thrust he had so swiftly driven home.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy told you,” he charged.

“I was told over the telephone,” his mother evaded. “I do not know

all voices that speak to me over that contrivance of all the

devils.”

Strangely, Ah Kim made no effort to run away from his mother, which

he could easily have done. She, on the other hand, found fresh

cause for more stick blows.

“Ah! Stubborn one! Why do you not cry? Mule that shameth its

ancestors! Never have I made you cry. From the time you were a

little boy I have never made you cry. Answer me! Why do you not

cry?”

Weak and breathless from her exertions, she dropped the stick and

panted and shook as if with a nervous palsy.

“I do not know, except that it is my way,” Ah Kim replied, gazing

solicitously at his mother. “I shall bring you a chair now, and

you will sit down and rest and feel better.”

But she flung away from him with a snort and tottered agedly across

the garden into the house. Meanwhile recovering his skull-cap and

smoothing his disordered attire, Ah Kim rubbed his hurts and gazed

after her with eyes of devotion. He even smiled, and almost might

it appear that he had enjoyed the beating.

Ah Kim had been so beaten ever since he was a boy, when he lived on

the high banks of the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse river. Here

his father had been born and toiled all his days from young manhood

as a towing coolie. When he died, Ah Kim, in his own young

manhood, took up the same honourable profession. Farther back than

all remembered annals of the family, had the males of it been

towing coolies. At the time of Christ his direct ancestors had

been doing the same thing, meeting the precisely similarly modelled

junks below the white water at the foot of the canyon, bending the

half-mile of rope to each junk, and, according to size, tailing on

from a hundred to two hundred coolies of them and by sheer, two-

legged man-power, bowed forward and down till their hands touched

the ground and their faces were sometimes within a foot of it,

dragging the junk up through the white water to the head of the

canyon.

Apparently, down all the intervening centuries, the payment of the

trade had not picked up. His father, his father’s father, and

himself, Ah Kim, had received the same invariable remuneration–per

junk one-fourteenth of a cent, at the rate he had since learned

money was valued in Hawaii. On long lucky summer days when the

waters were easy, the junks many, the hours of daylight sixteen,

sixteen hours of such heroic toil would earn over a cent. But in a

whole year a towing coolie did not earn more than a dollar and a

half. People could and did live on such an income. There were

women servants who received a yearly wage of a dollar. The net-

makers of Ti Wi earned between a dollar and two dollars a year.

They lived on such wages, or, at least, they did not die on them.

But for the towing coolies there were pickings, which were what

made the profession honourable and the guild a close and hereditary

corporation or labour union. One junk in five that was dragged up

through the rapids or lowered down was wrecked. One junk in every

ten was a total loss. The coolies of the towing guild knew the

freaks and whims of the currents, and grappled, and raked, and

netted a wet harvest from the river. They of the guild were looked

up to by lesser coolies, for they could afford to drink brick tea

and eat number four rice every day.

And Ah Kim had been contented and proud, until, one bitter spring

day of driving sleet and hail, he dragged ashore a drowning

Cantonese sailor. It was this wanderer, thawing out by his fire,

who first named the magic name Hawaii to him. He had himself never

been to that labourer’s paradise, said the sailor; but many Chinese

had gone there from Canton, and he had heard the talk of their

letters written back. In Hawaii was never frost nor famine. The

very pigs, never fed, were ever fat of the generous offal disdained

by man. A Cantonese or Yangtse family could live on the waste of

an Hawaii coolie. And wages! In gold dollars, ten a month, or, in

trade dollars, two a month, was what the contract Chinese coolie

received from the white-devil sugar kings. In a year the coolie

received the prodigious sum of two hundred and forty trade dollars-

-more than a hundred times what a coolie, toiling ten times as

hard, received on the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse. In short,

all things considered, an Hawaii coolie was one hundred times

better off, and, when the amount of labour was estimated, a

thousand times better off. In addition was the wonderful climate.

When Ah Kim was twenty-four, despite his mother’s pleadings and

beatings, he resigned from the ancient and honourable guild of the

eleventh cataract towing coolies, left his mother to go into a boss

coolie’s household as a servant for a dollar a year, and an annual

dress to cost not less than thirty cents, and himself departed down

the Yangtse to the great sea. Many were his adventures and severe

his toils and hardships ere, as a salt-sea junk-sailor, he won to

Canton. When he was twenty-six he signed five years of his life

and labour away to the Hawaii sugar kings and departed, one of

eight hundred contract coolies, for that far island land, on a

festering steamer run by a crazy captain and drunken officers and

rejected of Lloyds.

Honourable, among labourers, had Ah Kim’s rating been as a towing

coolie. In Hawaii, receiving a hundred times more pay, he found

himself looked down upon as the lowest of the low–a plantation

coolie, than which could be nothing lower. But a coolie whose

ancestors had towed junks up the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse

since before the birth of Christ inevitably inherits one character

in large degree, namely, the character of patience. This patience

was Ah Kim’s. At the end of five years, his compulsory servitude

over, thin as ever in body, in bank account he lacked just ten

trade dollars of possessing a thousand trade dollars.

On this sum he could have gone back to the Yangtse and retired for

life a really wealthy man. He would have possessed a larger sum,

had he not, on occasion, conservatively played che fa and fan tan,

and had he not, for a twelve-month, toiled among the centipedes and

scorpions of the stifling cane-fields in the semi-dream of a

continuous opium debauch. Why he had not toiled the whole five

years under the spell of opium was the expensiveness of the habit.

He had had no moral scruples. The drug had cost too much.

But Ah Kim did not return to China. He had observed the business

life of Hawaii and developed a vaulting ambition. For six months,

in order to learn business and English at the bottom, he clerked in

the plantation store. At the end of this time he knew more about

that particular store than did ever plantation manager know about

any plantation store. When he resigned his position he was

receiving forty gold a month, or eighty trade, and he was beginning

to put on flesh. Also, his attitude toward mere contract coolies

had become distinctively aristocratic. The manager offered to

raise him to sixty fold, which, by the year, would constitute a

fabulous fourteen hundred and forty trade, or seven hundred times

his annual earning on the Yangtse as a two-legged horse at one-

fourteenth of a gold cent per junk.

Instead of accepting, Ah Kim departed to Honolulu, and in the big

general merchandise store of Fong & Chow Fong began at the bottom

for fifteen gold per month. He worked a year and a half, and

resigned when he was thirty-three, despite the seventy-five gold

per month his Chinese employers were paying him. Then it was that

he put up his own sign: AH KIM COMPANY, GENERAL MERCHANDISE.

Also, better fed, there was about his less meagre figure a

foreshadowing of the melon-seed rotundity that was to attach to him

in future years.

With the years he prospered increasingly, so that, when he was

thirty-six, the promise of his figure was fulfilling rapidly, and,

himself a member of the exclusive and powerful Hai Gum Tong, and of

the Chinese Merchants’ Association, he was accustomed to sitting as

host at dinners that cost him as much as thirty years of towing on

the eleventh cataract would have earned him. Two things he missed:

a wife, and his mother to lay the stick on him as of yore.

When he was thirty-seven he consulted his bank balance. It stood

him three thousand gold. For twenty-five hundred down and an easy

mortgage he could buy the three-story shack-building, and the

ground in fee simple on which it stood. But to do this, left only

five hundred for a wife. Fu Yee Po had a marriageable, properly

small-footed daughter whom he was willing to import from China, and

sell to him for eight hundred gold, plus the costs of importation.

Further, Fu Yee Po was even willing to take five hundred down and

the remainder on note at 6 per cent.

Ah Kim, thirty-seven years of age, fat and a bachelor, really did

want a wife, especially a small-footed wife; for, China born and

reared, the immemorial small-footed female had been deeply

impressed into his fantasy of woman. But more, even more and far

more than a small-footed wife, did he want his mother and his

mother’s delectable beatings. So he declined Fu Yee Po’s easy

terms, and at much less cost imported his own mother from servant

in a boss coolie’s house at a yearly wage of a dollar and a thirty-

cent dress to be mistress of his Honolulu three-story shack

building with two household servants, three clerks, and a porter of

all work under her, to say nothing of ten thousand dollars’ worth

of dress goods on the shelves that ranged from the cheapest cotton

crepes to the most expensive hand-embroidered silks. For be it

known that even in that early day Ah Kim’s emporium was beginning

to cater to the tourist trade from the States.

For thirteen years Ah Kim had lived tolerably happily with his

mother, and by her been methodically beaten for causes just or

unjust, real or fancied; and at the end of it all he knew as

strongly as ever the ache of his heart and head for a wife, and of

his loins for sons to live after him, and carry on the dynasty of

Ah Kim Company. Such the dream that has ever vexed men, from those

early ones who first usurped a hunting right, monopolized a sandbar

for a fish-trap, or stormed a village and put the males thereof to

the sword. Kings, millionaires, and Chinese merchants of Honolulu

have this in common, despite that they may praise God for having

made them differently and in self-likable images.

And the ideal of woman that Ah Kim at fifty ached for had changed

from his ideal at thirty-seven. No small-footed wife did he want

now, but a free, natural, out-stepping normal-footed woman that,

somehow, appeared to him in his day dreams and haunted his night

visions in the form of Li Faa, the Silvery Moon Blossom. What if

she were twice widowed, the daughter of a kanaka mother, the wearer

of white-devil skirts and corsets and high-heeled slippers! He

wanted her. It seemed it was written that she should be joint

ancestor with him of the line that would continue the ownership and

management through the generations, of Ah Kim Company, General

Merchandise.

“I will have no half-pake daughter-in-law,” his mother often

reiterated to Ah Kim, pake being the Hawaiian word for Chinese.

“All pake must my daughter-in-law be, even as you, my son, and as

I, your mother. And she must wear trousers, my son, as all the

women of our family before her. No woman, in she-devil skirts and

corsets, can pay due reverence to our ancestors. Corsets and

reverence do not go together. Such a one is this shameless Li Faa.

She is impudent and independent, and will be neither obedient to

her husband nor her husband’s mother. This brazen-faced Li Faa

would believe herself the source of life and the first ancestor,

recognizing no ancestors before her. She laughs at our joss-

sticks, and paper prayers, and family gods, as I have been well

told–“

“Mrs. Chang Lucy,” Ah Kim groaned.

“Not alone Mrs. Chang Lucy, O son. I have inquired. At least a

dozen have heard her say of our joss house that it is all monkey

foolishness. The words are hers–she, who eats raw fish, raw

squid, and baked dog. Ours is the foolishness of monkeys. Yet

would she marry you, a monkey, because of your store that is a

palace and of the wealth that makes you a great man. And she would

put shame on me, and on your father before you long honourably

dead.”

And there was no discussing the matter. As things were, Ah Kim

knew his mother was right. Not for nothing had Li Faa been born

forty years before of a Chinese father, renegade to all tradition,

and of a kanaka mother whose immediate forebears had broken the

taboos, cast down their own Polynesian gods, and weak-heartedly

listened to the preaching about the remote and unimageable god of

the Christian missionaries. Li Faa, educated, who could read and

write English and Hawaiian and a fair measure of Chinese, claimed

to believe in nothing, although in her secret heart she feared the

kahunas (Hawaiian witch-doctors), who she was certain could charm

away ill luck or pray one to death. Li Faa would never come into

Ah Kim’s house, as he thoroughly knew, and kow-tow to his mother

and be slave to her in the immemorial Chinese way. Li Faa, from

the Chinese angle, was a new woman, a feminist, who rode horseback

astride, disported immodestly garbed at Waikiki on the surf-boards,

and at more than one luau (feast) had been known to dance the hula

with the worst and in excess of the worst, to the scandalous

delight of all.

Ah Kim himself, a generation younger than his mother, had been

bitten by the acid of modernity. The old order held, in so far as

he still felt in his subtlest crypts of being the dusty hand of the

past resting on him, residing in him; yet he subscribed to heavy

policies of fire and life insurance, acted as treasurer for the

local Chinese revolutionises that were for turning the Celestial

Empire into a republic, contributed to the funds of the Hawaii-born

Chinese baseball nine that excelled the Yankee nines at their own

game, talked theosophy with Katso Suguri, the Japanese Buddhist and

silk importer, fell for police graft, played and paid his insidious

share in the democratic politics of annexed Hawaii, and was

thinking of buying an automobile. Ah Kim never dared bare himself

to himself and thrash out and winnow out how much of the old he had

ceased to believe in. His mother was of the old, yet he revered

her and was happy under her bamboo stick. Li Faa, the Silvery Moon

Blossom, was of the new, yet he could never be quite completely

happy without her.

For he loved Li Faa. Moon-faced, rotund as a water-melon seed,

canny business man, wise with half a century of living–

nevertheless Ah Kim became an artist when he thought of her. He

thought of her in poems of names, as woman transmuted into flower-

terms of beauty and philosophic abstractions of achievement and

easement. She was, to him, and alone to him of all men in the

world, his Plum Blossom, his Tranquillity of Woman, his Flower of

Serenity, his Moon Lily, and his Perfect Rest. And as he murmured

these love endearments of namings, it seemed to him that in them

were the ripplings of running waters, the tinklings of silver wind-

bells, and the scents of the oleander and the jasmine. She was his

poem of woman, a lyric delight, a three-dimensions of flesh and

spirit delicious, a fate and a good fortune written, ere the first

man and woman were, by the gods whose whim had been to make all men

and women for sorrow and for joy.

But his mother put into his hand the ink-brush and placed under it,

on the table, the writing tablet.

“Paint,” said she, “the ideograph of TO MARRY.”

He obeyed, scarcely wondering, with the deft artistry of his race

and training painting the symbolic hieroglyphic.

“Resolve it,” commanded his mother.

Ah Kim looked at her, curious, willing to please, unaware of the

drift of her intent.

“Of what is it composed?” she persisted. “What are the three

originals, the sum of which is it: to marry, marriage, the coming

together and wedding of a man and a woman? Paint them, paint them

apart, the three originals, unrelated, so that we may know how the

wise men of old wisely built up the ideograph of to marry.”

And Ah Kim, obeying and painting, saw that what he had painted were

three picture-signs–the picture-signs of a hand, an ear, and a

woman.

“Name them,” said his mother; and he named them.

“It is true,” said she. “It is a great tale. It is the stuff of

the painted pictures of marriage. Such marriage was in the

beginning; such shall it always be in my house. The hand of the

man takes the woman’s ear, and by it leads her away to his house,

where she is to be obedient to him and to his mother. I was taken

by the ear, so, by your long honourably dead father. I have looked

at your hand. It is not like his hand. Also have I looked at the

ear of Li Faa. Never will you lead her by the ear. She has not

that kind of an ear. I shall live a long time yet, and I will be

mistress in my son’s house, after our ancient way, until I die.”

“But she is my revered ancestress,” Ah Kim explained to Li Faa.

He was timidly unhappy; for Li Faa, having ascertained that Mrs.

Tai Fu was at the temple of the Chinese AEsculapius making a food

offering of dried duck and prayers for her declining health, had

taken advantage of the opportunity to call upon him in his store.

Li Faa pursed her insolent, unpainted lips into the form of a half-

opened rosebud, and replied:

“That will do for China. I do not know China. This is Hawaii, and

in Hawaii the customs of all foreigners change.”

“She is nevertheless my ancestress,” Ah Kim protested, “the mother

who gave me birth, whether I am in China or Hawaii, O Silvery Moon

Blossom that I want for wife.”

“I have had two husbands,” Li Faa stated placidly. “One was a

pake, one was a Portuguese. I learned much from both. Also am I

educated. I have been to High School, and I have played the piano

in public. And I learned from my two husbands much. The pake

makes the best husband. Never again will I marry anything but a

pake. But he must not take me by the ear–“

“How do you know of that?” he broke in suspiciously.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy,” was the reply. “Mrs. Chang Lucy tells me

everything that your mother tells her, and your mother tells her

much. So let me tell you that mine is not that kind of an ear.”

“Which is what my honoured mother has told me,” Ah Kim groaned.

“Which is what your honoured mother told Mrs. Chang Lucy, which is

what Mrs. Chang Lucy told me,” Li Faa completed equably. “And I

now tell you, O Third Husband To Be, that the man is not born who

will lead me by the ear. It is not the way in Hawaii. I will go

only hand in hand with my man, side by side, fifty-fifty as is the

haole slang just now. My Portuguese husband thought different. He

tried to beat me. I landed him three times in the police court and

each time he worked out his sentence on the reef. After that he

got drowned.”

“My mother has been my mother for fifty years,” Ah Kim declared

stoutly.

“And for fifty years has she beaten you,” Li Faa giggled. “How my

father used to laugh at Yap Ten Shin! Like you, Yap Ten Shin had

been born in China, and had brought the China customs with him.

His old father was for ever beating him with a stick. He loved his

father. But his father beat him harder than ever when he became a

missionary pake. Every time he went to the missionary services,

his father beat him. And every time the missionary heard of it he

was harsh in his language to Yap Ten Shin for allowing his father

to beat him. And my father laughed and laughed, for my father was

a very liberal pake, who had changed his customs quicker than most

foreigners. And all the trouble was because Yap Ten Shin had a

loving heart. He loved his honourable father. He loved the God of

Love of the Christian missionary. But in the end, in me, he found

the greatest love of all, which is the love of woman. In me he

forgot his love for his father and his love for the loving Christ.

“And he offered my father six hundred gold, for me–the price was

small because my feet were not small. But I was half kanaka. I

said that I was not a slave-woman, and that I would be sold to no

man. My high-school teacher was a haole old maid who said love of

woman was so beyond price that it must never be sold. Perhaps that

is why she was an old maid. She was not beautiful. She could not

give herself away. My kanaka mother said it was not the kanaka way

to sell their daughters for a money price. They gave their

daughters for love, and she would listen to reason if Yap Ten Shin

provided luaus in quantity and quality. My pake father, as I have

told you, was liberal. He asked me if I wanted Yap Ten Shin for my

husband. And I said yes; and freely, of myself, I went to him. He

it was who was kicked by a horse; but he was a very good husband

before he was kicked by the horse.

“As for you, Ah Kim, you shall always be honourable and lovable for

me, and some day, when it is not necessary for you to take me by

the ear, I shall marry you and come here and be with you always,

and you will be the happiest pake in all Hawaii; for I have had two

husbands, and gone to high school, and am most wise in making a

husband happy. But that will be when your mother has ceased to

beat you. Mrs. Chang Lucy tells me that she beats you very hard.”

“She does,” Ah Kim affirmed. “Behold! He thrust back his loose

sleeves, exposing to the elbow his smooth and cherubic forearms.

They were mantled with black and blue marks that advertised the

weight and number of blows so shielded from his head and face.

“But she has never made me cry,” Ah Kim disclaimed hastily.

“Never, from the time I was a little boy, has she made me cry.”

“So Mrs. Chang Lucy says,” Li Faa observed. “She says that your

honourable mother often complains to her that she has never made

you cry.”

A sibilant warning from one of his clerks was too late. Having

regained the house by way of the back alley, Mrs. Tai Fu emerged

right upon them from out of the living apartments. Never had Ah

Kim seen his mother’s eyes so blazing furious. She ignored Li Faa,

as she screamed at him:

“Now will I make you cry. As never before shall I beat you until

you do cry.”

“Then let us go into the back rooms, honourable mother,” Ah Kim

suggested. “We will close the windows and the doors, and there may

you beat me.”

“No. Here shall you be beaten before all the world and this

shameless woman who would, with her own hand, take you by the ear

and call such sacrilege marriage! Stay, shameless woman.”

“I am going to stay anyway,” said Li Faa. She favoured the clerks

with a truculent stare. “And I’d like to see anything less than

the police put me out of here.”

“You will never be my daughter-in-law,” Mrs. Tai Fu snapped.

Li Faa nodded her head in agreement.

“But just the same,” she added, “shall your son be my third

husband.”

“You mean when I am dead?” the old mother screamed.

“The sun rises each morning,” Li Faa said enigmatically. “All my

life have I seen it rise–“

“You are forty, and you wear corsets.”

“But I do not dye my hair–that will come later,” Li Faa calmly

retorted. “As to my age, you are right. I shall be forty-one next

Kamehameha Day. For forty years I have seen the sun rise. My

father was an old man. Before he died he told me that he had

observed no difference in the rising of the sun since when he was a

little boy. The world is round. Confucius did not know that, but

you will find it in all the geography books. The world is round.

Ever it turns over on itself, over and over and around and around.

And the times and seasons of weather and life turn with it. What

is, has been before. What has been, will be again. The time of

the breadfruit and the mango ever recurs, and man and woman repeat

themselves. The robins nest, and in the springtime the plovers

come from the north. Every spring is followed by another spring.

The coconut palm rises into the air, ripens its fruit, and departs.

But always are there more coconut palms. This is not all my own

smart talk. Much of it my father told me. Proceed, honourable

Mrs. Tai Fu, and beat your son who is my Third Husband To Be. But

I shall laugh. I warn you I shall laugh.”

Ah Kim dropped down on his knees so as to give his mother every

advantage. And while she rained blows upon him with the bamboo

stick, Li Faa smiled and giggled, and finally burst into laughter.

“Harder, O honourable Mrs. Tai Fu!” Li Faa urged between paroxysms

of mirth.

Mrs. Tai Fu did her best, which was notably weak, until she

observed what made her drop the stick by her side in amazement. Ah

Kim was crying. Down both cheeks great round tears were coursing.

Li Faa was amazed. So were the gaping clerks. Most amazed of all

was Ah Kim, yet he could not help himself; and, although no further

blows fell, he cried steadily on.

“But why did you cry?” Li Faa demanded often of Ah Kim. “It was so

perfectly foolish a thing to do. She was not even hurting you.”

“Wait until we are married,” was Ah Kim’s invariable reply, “and

then, O Moon Lily, will I tell you.”

Two years later, one afternoon, more like a water-melon seed in

configuration than ever, Ah Kim returned home from a meeting of the

Chinese Protective Association, to find his mother dead on her

couch. Narrower and more unrelenting than ever were the forehead

and the brushed-back hair. But on her face was a withered smile.

The gods had been kind. She had passed without pain.

He telephoned first of all to Li Faa’s number but did not find her

until he called up Mrs. Chang Lucy. The news given, the marriage

was dated ahead with ten times the brevity of the old-line Chinese

custom. And if there be anything analogous to a bridesmaid in a

Chinese wedding, Mrs. Chang Lucy was just that.

“Why,” Li Faa asked Ah Kim when alone with him on their wedding

night, “why did you cry when your mother beat you that day in the

store? You were so foolish. She was not even hurting you.”

“That is why I cried,” answered Ah Kim.

Li Faa looked up at him without understanding.

“I cried,” he explained, “because I suddenly knew that my mother

was nearing her end. There was no weight, no hurt, in her blows.

I cried because I knew SHE NO LONGER HAD STRENGTH ENOUGH TO HURT

ME. That is why I cried, my Flower of Serenity, my Perfect Rest.

That is the only reason why I cried.”

WAIKIKI, HONOLULU.

June 16, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, London, Jack

![]()

hollands maandblad schrijversbeurzen uitgereikt

De dichteres en theatermaakster Esther Porcelijn (1985), schrijfster en kunsthistorica Bregje Hofstede (1988) en schrijver Maxim Roozen (1991) zijn de winnaars van de Hollands Maandblad beurzen 2012/2013. De laureaten kregen de prijzen uitgereikt in Amsterdam door Wim Brands tijdens het jaarlijkse Hollands Maandblad-literatuurfeest. Porcelijn en Hofstede ontvingen elk de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs (ter waarde van € 1000), en Roozen ontving de Hollands Maandblad schrijversbeurs (ter waarde van € 2000). Alle drie de schrijvers zijn medewerkers van het 54-jaar oude toonaangevende literaire tijdschrift dat onder redactie staat van Bastiaan Bommeljé, wordt uitgegeven door Uitgeverij Nieuw Amsterdam en onlangs door het Letterenfonds en Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds als een der vier beste literair tijdschriften van Nederland werd beloond met € 25.000 subsidie.

Porcelijn werd door de jury bekroond voor haar poëzie ‘die zonder kloppen binnenkomt’ met verzen die ‘onomwonden, gekarteld en tegendraads’ zijn. Hofstede kreeg de prijs vanwege het brede literaire spectrum dat zij bestrijkt, ‘dat reikt van dromerig proza tot hard-boiled essayistiek’. Roozen werd onderscheiden voor de ‘verbluffend vanzelfsprekende’ wijze waarop hij als debutant ‘het levensgevoel en de geesteswereld van de hedendaagse jeugd wist te schetsen’.

Eerdere laureaten van de Hollands Maandblad-beurzen waren onder anderen Vrouwkje Tuinman, Yusuf el-Halal (Ernest van der Kwast), Anke Scheeren, Nina Roos, Philip Huff en Kira Wuck.

Hollands Maandblad is het grootste zelfstandige literaire tijdschrift van Nederland en werd in 1959 opgericht door K.L. Poll. Tot de medewerkers behoren o.m. Arnon Grunberg, Leo Vroman, Kira Wuck, Eva Gerlach, Iris Le Rutte, Hugo Brandt Corstius, J.M.A. Biesheuvel, Wim Brands, Philip Huff, David Pefko, A.H.J. Dautzenberg, Maartje Wortel, Vrouwkje Tuinman en Maarten ’t Hart.

juryrapport hollands maandblad schrijversbeurzen 2012/2013

Redactie, redactieraad en uitgever van Hollands Maandblad,

tezamen met het bestuur van de Stichting Hollands Maandblad,

hebben het genoegen mede te delen dat tijdens een feestelijke bijeenkomst

te Amsterdam de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurzen 2012/2013 zijn uitgereikt.

Op voordracht van redactie & redactieraad werden de volgende medewerkers

van Hollands Maandblad aangewezen als winnaar

*

Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs: categorie poëzie

esther porcelijn

*

Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs: categorieën proza & essayistiek

bregje hofstede

*

Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs:

maxim roozen

*

Esther Porcelijn (1985) werd bekroond met een Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorie poëzie. En dat terwijl deze theatermaakster, toneelspeelster, schrijfster, filosofiestudente in feite weinig aanmoediging meer nodig heeft. Dat zij eind vorig jaar vrijwel gelijktijdig debuteerde met haar poëzie in Hollands Maandblad en werd uitverkoren tot stadsdichter van Tilburg was geen toeval. De laureaat heeft op talrijke podia en diverse festivals bewezen een buitengewoon multi-talent te zijn, en te beschikken over een tomeloze dadendrang, een wervelende dynamiek en een navenante pen. De jury werd onmiddellijk getroffen door haar gedichten die Hollands Maandblad binnenkwamen zonder kloppen en gewapend met woorden die even glashelder als persoonlijk, en even poëtisch als onomwonden, maar bovenal hard, gekarteld en tegendraads waren. In elk geval kreeg de lezer van Hollands Maandblad nimmer eerder nog voordat de titel van het gedicht aan de orde was bij wijze van poëtische preambule deze verzen toegeworpen:

Laten we het even niet over kwantummechanica hebben…

Even niet over mensenrechten…

Want daar loopt een vrouw met grote borsten.

Waarna een dichterlijk-wijsgerige zoektocht naar de zin van het leven volgt die klinkt als een urban rap met de urgentie van een locomotief die aan komt stormen uit de donkerste krochten van de menselijke beschaving, of misschien uit die van Tilburg. Vol verwachtingen over de letterkundige toekomst van deze laureaat kent de jury de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorie poëzie toe aan Esther Porcelijn.

Bregje Hofstede (1988) werd bekroond met de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorieën proza & essayistiek. In de ogen van de jury wist de laureaat haar diverse bijdragen aan de jaargang 2012 van Hollands Maandblad op drie overtuigende literaire fundamenten te grondvesten: ideeën, stijl en doorzettingsvermogen. Het is de jury niet ontgaan dat de laureaat ondanks, doch wellicht dankzij twee studies (Frans en Kunstgeschiedenis) die deels aan de Sorbonne en in Berlijn werden afgerond met het judicium cum laude, een bijzonder breed spectrum bestrijkt, dat reikt van dromerige fictie tot hard-boiled essayistiek. Vooral haar eersteling, het debuutverhaal over een al dan niet fictieve amour fou in de Parijse metro, waarbij de hartenklop samenvalt met het passeren van al die oh zo bekende ondergrondse stations, en haar laatsteling, een even wetenschappelijk als hartstochtelijk essay over de kosmopolitische kunstenaar en het multi-talent Alexander Alexeieff konden op unanieme bijval rekenen. De jury is ervan overtuigd dat deze laureaat nog van zich zal doen spreken, want zij heeft alles wat elke gewone sterveling zo graag zou willen hebben: intelligence, ténacité, promptitude et avant tout promesse et jeunesse. Vervuld van zowel ontzag als verwachtingen over haar schrijflust kent de jury Bregje Hofstede de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorieën proza & essayistiek toe.

Maxim Roozen (1991) werd bekroond met de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs. Hij is jong, in de ogen van de jury misschien wel benauwend jong, en toch is hij in zekere zin al gewassen door de literaire wateren die tegenwoordig zo vervaarlijk over de lage dijken van ons cultuurlandschap klotsen. Het is de jury niet ontgaan dat deze laureaat in 2009 op 17-jarige leeftijd een Wild Card wist te bemachtigen voor Write Now!-schrijfwedstrijd, die hij vervolgens zonder bloeddoping wist te winnen met een opmerkelijk verhaal dat hem meteen een pre-contract van een respectabele hoofdstedelijke uitgeverij voor een roman opleverde. Het is de jury evenmin ontgaan dat de schrijfster Maartje Wortel hem uitriep tot haar ‘jonge god’ en dat zij haar hartenkreet publiceerde nog voordat de laureaat buiten zijn vriendenkring bekend was. ‘Onthoud die naam,’ schreef zij over haar jonge god, ‘Voor nu en in de toekomst.’ Het kan dus geen toeval zijn dat het literaire debuut van deze laureaat, dat gewoon via de post in de brievenbus viel en eenmaal afgedrukt in Hollands Maandblad op de pagina stond met een verbluffende vanzelfsprekendheid alsof het altijd zo had moeten zijn. Overigens was er weinig vanzelfsprekends aan het verhaal van de laureaat, dat op treffende wijze het levensgevoel en het geestesleven van de hedendaagse jeugd wist te schetsen. De jury beseft dat de laureaat schrijven kan, de jury beseft ook dat zij de schouders van de laureaat thans belaadt met de verwachting dat hij een bijzonder talent is. Al met al leek het de redactieraad passend deze laureaat haar hoogste teken van waardering, ondersteuning en aanmoediging te verlenen, in de verwachting dat hij nog van zich zal doen spreken. Vandaar dat de jury de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs 2012/2013 toekent aan Maxim Roozen.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

After The Race

The cars came scudding in towards Dublin, running evenly like pellets in the groove of the Naas Road. At the crest of the hill at Inchicore sightseers had gathered in clumps to watch the cars careering homeward and through this channel of poverty and inaction the Continent sped its wealth and industry. Now and again the clumps of people raised the cheer of the gratefully oppressed. Their sympathy, however, was for the blue cars, the cars of their friends, the French.

The French, moreover, were virtual victors. Their team had finished solidly; they had been placed second and third and the driver of the winning German car was reported a Belgian. Each blue car, therefore, received a double measure of welcome as it topped the crest of the hill and each cheer of welcome was acknowledged with smiles and nods by those in the car. In one of these trimly built cars was a party of four young men whose spirits seemed to be at present well above the level of successful Gallicism: in fact, these four young men were almost hilarious. They were Charles Segouin, the owner of the car; Andre Riviere, a young electrician of Canadian birth; a huge Hungarian named Villona and a neatly groomed young man named Doyle. Segouin was in good humour because he had unexpectedly received some orders in advance (he was about to start a motor establishment in Paris) and Riviere was in good humour because he was to be appointed manager of the establishment; these two young men (who were cousins) were also in good humour because of the success of the French cars. Villona was in good humour because he had had a very satisfactory luncheon; and besides he was an optimist by nature. The fourth member of the party, however, was too excited to be genuinely happy.

He was about twenty-six years of age, with a soft, light brown moustache and rather innocent-looking grey eyes. His father, who had begun life as an advanced Nationalist, had modified his views early. He had made his money as a butcher in Kingstown and by opening shops in Dublin and in the suburbs he had made his money many times over. He had also been fortunate enough to secure some of the police contracts and in the end he had become rich enough to be alluded to in the Dublin newspapers as a merchant prince. He had sent his son to England to be educated in a big Catholic college and had afterwards sent him to Dublin University to study law. Jimmy did not study very earnestly and took to bad courses for a while. He had money and he was popular; and he divided his time curiously between musical and motoring circles. Then he had been sent for a term to Cambridge to see a little life. His father, remonstrative, but covertly proud of the excess, had paid his bills and brought him home. It was at Cambridge that he had met Segouin. They were not much more than acquaintances as yet but Jimmy found great pleasure in the society of one who had seen so much of the world and was reputed to own some of the biggest hotels in France. Such a person (as his father agreed) was well worth knowing, even if he had not been the charming companion he was. Villona was entertaining also, a brilliant pianist, but, unfortunately, very poor.

The car ran on merrily with its cargo of hilarious youth. The two cousins sat on the front seat; Jimmy and his Hungarian friend sat behind. Decidedly Villona was in excellent spirits; he kept up a deep bass hum of melody for miles of the road The Frenchmen flung their laughter and light words over their shoulders and often Jimmy had to strain forward to catch the quick phrase. This was not altogether pleasant for him, as he had nearly always to make a deft guess at the meaning and shout back a suitable answer in the face of a high wind. Besides Villona’s humming would confuse anybody; the noise of the car, too.

Rapid motion through space elates one; so does notoriety; so does the possession of money. These were three good reasons for Jimmy’s excitement. He had been seen by many of his friends that day in the company of these Continentals. At the control Segouin had presented him to one of the French competitors and, in answer to his confused murmur of compliment, the swarthy face of the driver had disclosed a line of shining white teeth. It was pleasant after that honour to return to the profane world of spectators amid nudges and significant looks. Then as to money, he really had a great sum under his control. Segouin, perhaps, would not think it a great sum but Jimmy who, in spite of temporary errors, was at heart the inheritor of solid instincts knew well with what difficulty it had been got together. This knowledge had previously kept his bills within the limits of reasonable recklessness, and if he had been so conscious of the labour latent in money when there had been question merely of some freak of the higher intelligence, how much more so now when he was about to stake the greater part of his substance! It was a serious thing for him.

Of course, the investment was a good one and Segouin had managed to give the impression that it was by a favour of friendship the mite of Irish money was to be included in the capital of the concern. Jimmy had a respect for his father’s shrewdness in business matters and in this case it had been his father who had first suggested the investment; money to be made in the motor business, pots of money. Moreover Segouin had the unmistakable air of wealth. Jimmy set out to translate into days’ work that lordly car in which he sat. How smoothly it ran. In what style they had come careering along the country roads! The journey laid a magical finger on the genuine pulse of life and gallantly the machinery of human nerves strove to answer the bounding courses of the swift blue animal.

They drove down Dame Street. The street was busy with unusual traffic, loud with the horns of motorists and the gongs of impatient tram-drivers. Near the Bank Segouin drew up and Jimmy and his friend alighted. A little knot of people collected on the footpath to pay homage to the snorting motor. The party was to dine together that evening in Segouin’s hotel and, meanwhile, Jimmy and his friend, who was staying with him, were to go home to dress. The car steered out slowly for Grafton Street while the two young men pushed their way through the knot of gazers. They walked northward with a curious feeling of disappointment in the exercise, while the city hung its pale globes of light above them in a haze of summer evening.

In Jimmy’s house this dinner had been pronounced an occasion. A certain pride mingled with his parents’ trepidation, a certain eagerness, also, to play fast and loose for the names of great foreign cities have at least this virtue. Jimmy, too, looked very well when he was dressed and, as he stood in the hall giving a last equation to the bows of his dress tie, his father may have felt even commercially satisfied at having secured for his son qualities often unpurchaseable. His father, therefore, was unusually friendly with Villona and his manner expressed a real respect for foreign accomplishments; but this subtlety of his host was probably lost upon the Hungarian, who was beginning to have a sharp desire for his dinner.

The dinner was excellent, exquisite. Segouin, Jimmy decided, had a very refined taste. The party was increased by a young Englishman named Routh whom Jimmy had seen with Segouin at Cambridge. The young men supped in a snug room lit by electric candle lamps. They talked volubly and with little reserve. Jimmy, whose imagination was kindling, conceived the lively youth of the Frenchmen twined elegantly upon the firm framework of the Englishman’s manner. A graceful image of his, he thought, and a just one. He admired the dexterity with which their host directed the conversation. The five young men had various tastes and their tongues had been loosened. Villona, with immense respect, began to discover to the mildly surprised Englishman the beauties of the English madrigal, deploring the loss of old instruments. Riviere, not wholly ingenuously, undertook to explain to Jimmy the triumph of the French mechanicians. The resonant voice of the Hungarian was about to prevail in ridicule of the spurious lutes of the romantic painters when Segouin shepherded his party into politics. Here was congenial ground for all. Jimmy, under generous influences, felt the buried zeal of his father wake to life within him: he aroused the torpid Routh at last. The room grew doubly hot and Segouin’s task grew harder each moment: there was even danger of personal spite. The alert host at an opportunity lifted his glass to Humanity and, when the toast had been drunk, he threw open a window significantly.

That night the city wore the mask of a capital. The five young men strolled along Stephen’s Green in a faint cloud of aromatic smoke. They talked loudly and gaily and their cloaks dangled from their shoulders. The people made way for them. At the corner of Grafton Street a short fat man was putting two handsome ladies on a car in charge of another fat man. The car drove off and the short fat man caught sight of the party.

“Andre.”

“It’s Farley!”

A torrent of talk followed. Farley was an American. No one knew very well what the talk was about. Villona and Riviere were the noisiest, but all the men were excited. They got up on a car, squeezing themselves together amid much laughter. They drove by the crowd, blended now into soft colours, to a music of merry bells. They took the train at Westland Row and in a few seconds, as it seemed to Jimmy, they were walking out of Kingstown Station. The ticket-collector saluted Jimmy; he was an old man:

“Fine night, sir!”

It was a serene summer night; the harbour lay like a darkened mirror at their feet. They proceeded towards it with linked arms, singing Cadet Roussel in chorus, stamping their feet at every:

“Ho! Ho! Hohe, vraiment!”

They got into a rowboat at the slip and made out for the American’s yacht. There was to be supper, music, cards. Villona said with conviction:

“It is delightful!”

There was a yacht piano in the cabin. Villona played a waltz for Farley and Riviere, Farley acting as cavalier and Riviere as lady. Then an impromptu square dance, the men devising original figures. What merriment! Jimmy took his part with a will; this was seeing life, at least. Then Farley got out of breath and cried “Stop!” A man brought in a light supper, and the young men sat down to it for form’s sake. They drank, however: it was Bohemian. They drank Ireland, England, France, Hungary, the United States of America. Jimmy made a speech, a long speech, Villona saying: “Hear! hear!” whenever there was a pause. There was a great clapping of hands when he sat down. It must have been a good speech. Farley clapped him on the back and laughed loudly. What jovial fellows! What good company they were!

Cards! cards! The table was cleared. Villona returned quietly to his piano and played voluntaries for them. The other men played game after game, flinging themselves boldly into the adventure. They drank the health of the Queen of Hearts and of the Queen of Diamonds. Jimmy felt obscurely the lack of an audience: the wit was flashing. Play ran very high and paper began to pass. Jimmy did not know exactly who was winning but he knew that he was losing. But it was his own fault for he frequently mistook his cards and the other men had to calculate his I.O.U.’s for him. They were devils of fellows but he wished they would stop: it was getting late. Someone gave the toast of the yacht The Belle of Newport and then someone proposed one great game for a finish.

The piano had stopped; Villona must have gone up on deck. It was a terrible game. They stopped just before the end of it to drink for luck. Jimmy understood that the game lay between Routh and Segouin. What excitement! Jimmy was excited too; he would lose, of course. How much had he written away? The men rose to their feet to play the last tricks. talking and gesticulating. Routh won. The cabin shook with the young men’s cheering and the cards were bundled together. They began then to gather in what they had won. Farley and Jimmy were the heaviest losers.

He knew that he would regret in the morning but at present he was glad of the rest, glad of the dark stupor that would cover up his folly. He leaned his elbows on the table and rested his head between his hands, counting the beats of his temples. The cabin door opened and he saw the Hungarian standing in a shaft of grey light:

“Daybreak, gentlemen!”

James Joyce: After the race

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Joyce, James, Joyce, James

foto joodse omroep

Esther Porcelijn in nieuwe serie

‘Zoek de verschillen’ bij de Joodse Omroep

Vanaf de eerste zondag in maart programmeert de Joodse Omroep drie nieuwe delen van de inmiddels populaire serie Zoek de verschillen. Per aflevering vertrekt steeds een andere jongere naar een voor hem of haar onbekende Joodse gemeenschap elders in de wereld. Van tevoren weten de deelnemers niet waar ze zullen belanden: dat horen ze pas op Schiphol. Vervolgens draait de Nederlandse hoofdpersoon een aantal dagen mee in een plaatselijke familie en wordt geconfronteerd met een andere cultuur, andere gebruiken en andere denkbeelden binnen het Jodendom. Dat dit niet altijd even gemakkelijk is, zien we in deze spannende reeks.

foto joodse omroep

De afgelopen weken zijn de opnamen gemaakt voor de nieuwe reeks met als een van de hoofdpersonen Esther Porcelijn, theatermaakster en stadsdichter van Tilburg. Tijdens een aantal voor haar zeer intensieve dagen was de seculiere Esther te gast bij de Chabad-gemeenschap in Brooklyn, New York. Onder de hoede van rabbijn Chaim Dalfin en zijn gezin, werd de seculiere theatermaakster ondergedompeld in het Amerikaanse orthodoxe leven. Hoe het de Tilburgse daar vergaan is, is te zien in Zoek de verschillen.

Op zondag 3, 10 en 17 maart Nederland 2, 14:15 uur (Esther Porcelijn in New York is te zien in de aflevering van 10 maart)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Mother

Mr Holohan, assistant secretary of the Eire Abu Society, had been walking up and down Dublin for nearly a month, with his hands and pockets full of dirty pieces of paper, arranging about the series of concerts. He had a game leg and for this his friends called him Hoppy Holohan. He walked up and down constantly, stood by the hour at street corners arguing the point and made notes; but in the end it was Mrs. Kearney who arranged everything.

Miss Devlin had become Mrs. Kearney out of spite. She had been educated in a high-class convent, where she had learned French and music. As she was naturally pale and unbending in manner she made few friends at school. When she came to the age of marriage she was sent out to many houses, where her playing and ivory manners were much admired. She sat amid the chilly circle of her accomplishments, waiting for some suitor to brave it and offer her a brilliant life. But the young men whom she met were ordinary and she gave them no encouragement, trying to console her romantic desires by eating a great deal of Turkish Delight in secret. However, when she drew near the limit and her friends began to loosen their tongues about her, she silenced them by marrying Mr. Kearney, who was a bootmaker on Ormond Quay.

He was much older than she. His conversation, which was serious, took place at intervals in his great brown beard. After the first year of married life, Mrs. Kearney perceived that such a man would wear better than a romantic person, but she never put her own romantic ideas away. He was sober, thrifty and pious; he went to the altar every first Friday, sometimes with her, oftener by himself. But she never weakened in her religion and was a good wife to him. At some party in a strange house when she lifted her eyebrow ever so slightly he stood up to take his leave and, when his cough troubled him, she put the eider-down quilt over his feet and made a strong rum punch. For his part, he was a model father. By paying a small sum every week into a society, he ensured for both his daughters a dowry of one hundred pounds each when they came to the age of twenty-four. He sent the older daughter, Kathleen, to a good convent, where she learned French and music, and afterward paid her fees at the Academy. Every year in the month of July Mrs. Kearney found occasion to say to some friend:

“My good man is packing us off to Skerries for a few weeks.”

If it was not Skerries it was Howth or Greystones.