Jack London: The Tears of Ah Kim

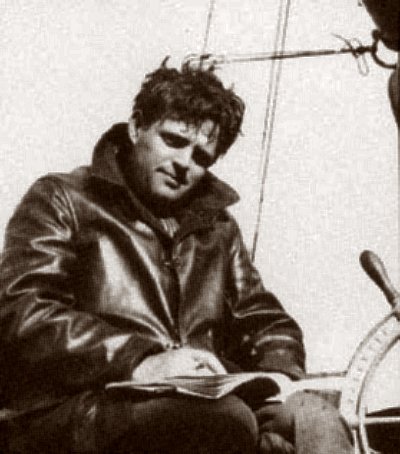

Jack London

(1876-1916)

The Tears of Ah Kim

There was a great noise and racket, but no scandal, in Honolulu’s

Chinatown. Those within hearing distance merely shrugged their

shoulders and smiled tolerantly at the disturbance as an affair of

accustomed usualness. “What is it?” asked Chin Mo, down with a

sharp pleurisy, of his wife, who had paused for a second at the

open window to listen.

“Only Ah Kim,” was her reply. “His mother is beating him again.”

The fracas was taking place in the garden, behind the living rooms

that were at the back of the store that fronted on the street with

the proud sign above: AH KIM COMPANY, GENERAL MERCHANDISE. The

garden was a miniature domain, twenty feet square, that somehow

cunningly seduced the eye into a sense and seeming of illimitable

vastness. There were forests of dwarf pines and oaks, centuries

old yet two or three feet in height, and imported at enormous care

and expense. A tiny bridge, a pace across, arched over a miniature

river that flowed with rapids and cataracts from a miniature lake

stocked with myriad-finned, orange-miracled goldfish that in

proportion to the lake and landscape were whales. On every side

the many windows of the several-storied shack-buildings looked

down. In the centre of the garden, on the narrow gravelled walk

close beside the lake Ah Kim was noisily receiving his beating.

No Chinese lad of tender and beatable years was Ah Kim. His was

the store of Ah Kim Company, and his was the achievement of

building it up through the long years from the shoestring of

savings of a contract coolie labourer to a bank account in four

figures and a credit that was gilt edged. An even half-century of

summers and winters had passed over his head, and, in the passing,

fattened him comfortably and snugly. Short of stature, his full

front was as rotund as a water-melon seed. His face was moon-

faced. His garb was dignified and silken, and his black-silk

skull-cap with the red button atop, now, alas! fallen on the

ground, was the skull-cap worn by the successful and dignified

merchants of his race.

But his appearance, in this moment of the present, was anything but

dignified. Dodging and ducking under a rain of blows from a bamboo

cane, he was crouched over in a half-doubled posture. When he was

rapped on the knuckles and elbows, with which he shielded his face

and head, his winces were genuine and involuntary. From the many

surrounding windows the neighbourhood looked down with placid

enjoyment.

And she who wielded the stick so shrewdly from long practice!

Seventy-four years old, she looked every minute of her time. Her

thin legs were encased in straight-lined pants of linen stiff-

textured and shiny-black. Her scraggly grey hair was drawn

unrelentingly and flatly back from a narrow, unrelenting forehead.

Eyebrows she had none, having long since shed them. Her eyes, of

pin-hole tininess, were blackest black. She was shockingly

cadaverous. Her shrivelled forearm, exposed by the loose sleeve,

possessed no more of muscle than several taut bowstrings stretched

across meagre bone under yellow, parchment-like skin. Along this

mummy arm jade bracelets shot up and down and clashed with every

blow.

“Ah!” she cried out, rhythmically accenting her blows in series of

three to each shrill observation. “I forbade you to talk to Li

Faa. To-day you stopped on the street with her. Not an hour ago.

Half an hour by the clock you talked.–What is that?”

“It was the thrice-accursed telephone,” Ah Kim muttered, while she

suspended the stick to catch what he said. “Mrs. Chang Lucy told

you. I know she did. I saw her see me. I shall have the

telephone taken out. It is of the devil.”

“It is a device of all the devils,” Mrs. Tai Fu agreed, taking a

fresh grip on the stick. “Yet shall the telephone remain. I like

to talk with Mrs. Chang Lucy over the telephone.”

“She has the eyes of ten thousand cats,” quoth Ah Kim, ducking and

receiving the stick stinging on his knuckles. “And the tongues of

ten thousand toads,” he supplemented ere his next duck.

“She is an impudent-faced and evil-mannered hussy,” Mrs. Tai Fu

accented.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy was ever that,” Ah Kim murmured like the dutiful

son he was.

“I speak of Li Faa,” his mother corrected with stick emphasis.

“She is only half Chinese, as you know. Her mother was a shameless

kanaka. She wears skirts like the degraded haole women–also

corsets, as I have seen for myself. Where are her children? Yet

has she buried two husbands.”

“The one was drowned, the other kicked by a horse,” Ah Kim

qualified.

“A year of her, unworthy son of a noble father, and you would

gladly be going out to get drowned or be kicked by a horse.”

Subdued chucklings and laughter from the window audience applauded

her point.

“You buried two husbands yourself, revered mother,” Ah Kim was

stung to retort.

“I had the good taste not to marry a third. Besides, my two

husbands died honourably in their beds. They were not kicked by

horses nor drowned at sea. What business is it of our neighbours

that you should inform them I have had two husbands, or ten, or

none? You have made a scandal of me, before all our neighbours,

and for that I shall now give you a real beating.”

Ah Kim endured the staccato rain of blows, and said when his mother

paused, breathless and weary:

“Always have I insisted and pleaded, honourable mother, that you

beat me in the house, with the windows and doors closed tight, and

not in the open street or the garden open behind the house.

“You have called this unthinkable Li Faa the Silvery Moon Blossom,”

Mrs. Tai Fu rejoined, quite illogically and femininely, but with

utmost success in so far as she deflected her son from continuance

of the thrust he had so swiftly driven home.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy told you,” he charged.

“I was told over the telephone,” his mother evaded. “I do not know

all voices that speak to me over that contrivance of all the

devils.”

Strangely, Ah Kim made no effort to run away from his mother, which

he could easily have done. She, on the other hand, found fresh

cause for more stick blows.

“Ah! Stubborn one! Why do you not cry? Mule that shameth its

ancestors! Never have I made you cry. From the time you were a

little boy I have never made you cry. Answer me! Why do you not

cry?”

Weak and breathless from her exertions, she dropped the stick and

panted and shook as if with a nervous palsy.

“I do not know, except that it is my way,” Ah Kim replied, gazing

solicitously at his mother. “I shall bring you a chair now, and

you will sit down and rest and feel better.”

But she flung away from him with a snort and tottered agedly across

the garden into the house. Meanwhile recovering his skull-cap and

smoothing his disordered attire, Ah Kim rubbed his hurts and gazed

after her with eyes of devotion. He even smiled, and almost might

it appear that he had enjoyed the beating.

Ah Kim had been so beaten ever since he was a boy, when he lived on

the high banks of the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse river. Here

his father had been born and toiled all his days from young manhood

as a towing coolie. When he died, Ah Kim, in his own young

manhood, took up the same honourable profession. Farther back than

all remembered annals of the family, had the males of it been

towing coolies. At the time of Christ his direct ancestors had

been doing the same thing, meeting the precisely similarly modelled

junks below the white water at the foot of the canyon, bending the

half-mile of rope to each junk, and, according to size, tailing on

from a hundred to two hundred coolies of them and by sheer, two-

legged man-power, bowed forward and down till their hands touched

the ground and their faces were sometimes within a foot of it,

dragging the junk up through the white water to the head of the

canyon.

Apparently, down all the intervening centuries, the payment of the

trade had not picked up. His father, his father’s father, and

himself, Ah Kim, had received the same invariable remuneration–per

junk one-fourteenth of a cent, at the rate he had since learned

money was valued in Hawaii. On long lucky summer days when the

waters were easy, the junks many, the hours of daylight sixteen,

sixteen hours of such heroic toil would earn over a cent. But in a

whole year a towing coolie did not earn more than a dollar and a

half. People could and did live on such an income. There were

women servants who received a yearly wage of a dollar. The net-

makers of Ti Wi earned between a dollar and two dollars a year.

They lived on such wages, or, at least, they did not die on them.

But for the towing coolies there were pickings, which were what

made the profession honourable and the guild a close and hereditary

corporation or labour union. One junk in five that was dragged up

through the rapids or lowered down was wrecked. One junk in every

ten was a total loss. The coolies of the towing guild knew the

freaks and whims of the currents, and grappled, and raked, and

netted a wet harvest from the river. They of the guild were looked

up to by lesser coolies, for they could afford to drink brick tea

and eat number four rice every day.

And Ah Kim had been contented and proud, until, one bitter spring

day of driving sleet and hail, he dragged ashore a drowning

Cantonese sailor. It was this wanderer, thawing out by his fire,

who first named the magic name Hawaii to him. He had himself never

been to that labourer’s paradise, said the sailor; but many Chinese

had gone there from Canton, and he had heard the talk of their

letters written back. In Hawaii was never frost nor famine. The

very pigs, never fed, were ever fat of the generous offal disdained

by man. A Cantonese or Yangtse family could live on the waste of

an Hawaii coolie. And wages! In gold dollars, ten a month, or, in

trade dollars, two a month, was what the contract Chinese coolie

received from the white-devil sugar kings. In a year the coolie

received the prodigious sum of two hundred and forty trade dollars-

-more than a hundred times what a coolie, toiling ten times as

hard, received on the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse. In short,

all things considered, an Hawaii coolie was one hundred times

better off, and, when the amount of labour was estimated, a

thousand times better off. In addition was the wonderful climate.

When Ah Kim was twenty-four, despite his mother’s pleadings and

beatings, he resigned from the ancient and honourable guild of the

eleventh cataract towing coolies, left his mother to go into a boss

coolie’s household as a servant for a dollar a year, and an annual

dress to cost not less than thirty cents, and himself departed down

the Yangtse to the great sea. Many were his adventures and severe

his toils and hardships ere, as a salt-sea junk-sailor, he won to

Canton. When he was twenty-six he signed five years of his life

and labour away to the Hawaii sugar kings and departed, one of

eight hundred contract coolies, for that far island land, on a

festering steamer run by a crazy captain and drunken officers and

rejected of Lloyds.

Honourable, among labourers, had Ah Kim’s rating been as a towing

coolie. In Hawaii, receiving a hundred times more pay, he found

himself looked down upon as the lowest of the low–a plantation

coolie, than which could be nothing lower. But a coolie whose

ancestors had towed junks up the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse

since before the birth of Christ inevitably inherits one character

in large degree, namely, the character of patience. This patience

was Ah Kim’s. At the end of five years, his compulsory servitude

over, thin as ever in body, in bank account he lacked just ten

trade dollars of possessing a thousand trade dollars.

On this sum he could have gone back to the Yangtse and retired for

life a really wealthy man. He would have possessed a larger sum,

had he not, on occasion, conservatively played che fa and fan tan,

and had he not, for a twelve-month, toiled among the centipedes and

scorpions of the stifling cane-fields in the semi-dream of a

continuous opium debauch. Why he had not toiled the whole five

years under the spell of opium was the expensiveness of the habit.

He had had no moral scruples. The drug had cost too much.

But Ah Kim did not return to China. He had observed the business

life of Hawaii and developed a vaulting ambition. For six months,

in order to learn business and English at the bottom, he clerked in

the plantation store. At the end of this time he knew more about

that particular store than did ever plantation manager know about

any plantation store. When he resigned his position he was

receiving forty gold a month, or eighty trade, and he was beginning

to put on flesh. Also, his attitude toward mere contract coolies

had become distinctively aristocratic. The manager offered to

raise him to sixty fold, which, by the year, would constitute a

fabulous fourteen hundred and forty trade, or seven hundred times

his annual earning on the Yangtse as a two-legged horse at one-

fourteenth of a gold cent per junk.

Instead of accepting, Ah Kim departed to Honolulu, and in the big

general merchandise store of Fong & Chow Fong began at the bottom

for fifteen gold per month. He worked a year and a half, and

resigned when he was thirty-three, despite the seventy-five gold

per month his Chinese employers were paying him. Then it was that

he put up his own sign: AH KIM COMPANY, GENERAL MERCHANDISE.

Also, better fed, there was about his less meagre figure a

foreshadowing of the melon-seed rotundity that was to attach to him

in future years.

With the years he prospered increasingly, so that, when he was

thirty-six, the promise of his figure was fulfilling rapidly, and,

himself a member of the exclusive and powerful Hai Gum Tong, and of

the Chinese Merchants’ Association, he was accustomed to sitting as

host at dinners that cost him as much as thirty years of towing on

the eleventh cataract would have earned him. Two things he missed:

a wife, and his mother to lay the stick on him as of yore.

When he was thirty-seven he consulted his bank balance. It stood

him three thousand gold. For twenty-five hundred down and an easy

mortgage he could buy the three-story shack-building, and the

ground in fee simple on which it stood. But to do this, left only

five hundred for a wife. Fu Yee Po had a marriageable, properly

small-footed daughter whom he was willing to import from China, and

sell to him for eight hundred gold, plus the costs of importation.

Further, Fu Yee Po was even willing to take five hundred down and

the remainder on note at 6 per cent.

Ah Kim, thirty-seven years of age, fat and a bachelor, really did

want a wife, especially a small-footed wife; for, China born and

reared, the immemorial small-footed female had been deeply

impressed into his fantasy of woman. But more, even more and far

more than a small-footed wife, did he want his mother and his

mother’s delectable beatings. So he declined Fu Yee Po’s easy

terms, and at much less cost imported his own mother from servant

in a boss coolie’s house at a yearly wage of a dollar and a thirty-

cent dress to be mistress of his Honolulu three-story shack

building with two household servants, three clerks, and a porter of

all work under her, to say nothing of ten thousand dollars’ worth

of dress goods on the shelves that ranged from the cheapest cotton

crepes to the most expensive hand-embroidered silks. For be it

known that even in that early day Ah Kim’s emporium was beginning

to cater to the tourist trade from the States.

For thirteen years Ah Kim had lived tolerably happily with his

mother, and by her been methodically beaten for causes just or

unjust, real or fancied; and at the end of it all he knew as

strongly as ever the ache of his heart and head for a wife, and of

his loins for sons to live after him, and carry on the dynasty of

Ah Kim Company. Such the dream that has ever vexed men, from those

early ones who first usurped a hunting right, monopolized a sandbar

for a fish-trap, or stormed a village and put the males thereof to

the sword. Kings, millionaires, and Chinese merchants of Honolulu

have this in common, despite that they may praise God for having

made them differently and in self-likable images.

And the ideal of woman that Ah Kim at fifty ached for had changed

from his ideal at thirty-seven. No small-footed wife did he want

now, but a free, natural, out-stepping normal-footed woman that,

somehow, appeared to him in his day dreams and haunted his night

visions in the form of Li Faa, the Silvery Moon Blossom. What if

she were twice widowed, the daughter of a kanaka mother, the wearer

of white-devil skirts and corsets and high-heeled slippers! He

wanted her. It seemed it was written that she should be joint

ancestor with him of the line that would continue the ownership and

management through the generations, of Ah Kim Company, General

Merchandise.

“I will have no half-pake daughter-in-law,” his mother often

reiterated to Ah Kim, pake being the Hawaiian word for Chinese.

“All pake must my daughter-in-law be, even as you, my son, and as

I, your mother. And she must wear trousers, my son, as all the

women of our family before her. No woman, in she-devil skirts and

corsets, can pay due reverence to our ancestors. Corsets and

reverence do not go together. Such a one is this shameless Li Faa.

She is impudent and independent, and will be neither obedient to

her husband nor her husband’s mother. This brazen-faced Li Faa

would believe herself the source of life and the first ancestor,

recognizing no ancestors before her. She laughs at our joss-

sticks, and paper prayers, and family gods, as I have been well

told–“

“Mrs. Chang Lucy,” Ah Kim groaned.

“Not alone Mrs. Chang Lucy, O son. I have inquired. At least a

dozen have heard her say of our joss house that it is all monkey

foolishness. The words are hers–she, who eats raw fish, raw

squid, and baked dog. Ours is the foolishness of monkeys. Yet

would she marry you, a monkey, because of your store that is a

palace and of the wealth that makes you a great man. And she would

put shame on me, and on your father before you long honourably

dead.”

And there was no discussing the matter. As things were, Ah Kim

knew his mother was right. Not for nothing had Li Faa been born

forty years before of a Chinese father, renegade to all tradition,

and of a kanaka mother whose immediate forebears had broken the

taboos, cast down their own Polynesian gods, and weak-heartedly

listened to the preaching about the remote and unimageable god of

the Christian missionaries. Li Faa, educated, who could read and

write English and Hawaiian and a fair measure of Chinese, claimed

to believe in nothing, although in her secret heart she feared the

kahunas (Hawaiian witch-doctors), who she was certain could charm

away ill luck or pray one to death. Li Faa would never come into

Ah Kim’s house, as he thoroughly knew, and kow-tow to his mother

and be slave to her in the immemorial Chinese way. Li Faa, from

the Chinese angle, was a new woman, a feminist, who rode horseback

astride, disported immodestly garbed at Waikiki on the surf-boards,

and at more than one luau (feast) had been known to dance the hula

with the worst and in excess of the worst, to the scandalous

delight of all.

Ah Kim himself, a generation younger than his mother, had been

bitten by the acid of modernity. The old order held, in so far as

he still felt in his subtlest crypts of being the dusty hand of the

past resting on him, residing in him; yet he subscribed to heavy

policies of fire and life insurance, acted as treasurer for the

local Chinese revolutionises that were for turning the Celestial

Empire into a republic, contributed to the funds of the Hawaii-born

Chinese baseball nine that excelled the Yankee nines at their own

game, talked theosophy with Katso Suguri, the Japanese Buddhist and

silk importer, fell for police graft, played and paid his insidious

share in the democratic politics of annexed Hawaii, and was

thinking of buying an automobile. Ah Kim never dared bare himself

to himself and thrash out and winnow out how much of the old he had

ceased to believe in. His mother was of the old, yet he revered

her and was happy under her bamboo stick. Li Faa, the Silvery Moon

Blossom, was of the new, yet he could never be quite completely

happy without her.

For he loved Li Faa. Moon-faced, rotund as a water-melon seed,

canny business man, wise with half a century of living–

nevertheless Ah Kim became an artist when he thought of her. He

thought of her in poems of names, as woman transmuted into flower-

terms of beauty and philosophic abstractions of achievement and

easement. She was, to him, and alone to him of all men in the

world, his Plum Blossom, his Tranquillity of Woman, his Flower of

Serenity, his Moon Lily, and his Perfect Rest. And as he murmured

these love endearments of namings, it seemed to him that in them

were the ripplings of running waters, the tinklings of silver wind-

bells, and the scents of the oleander and the jasmine. She was his

poem of woman, a lyric delight, a three-dimensions of flesh and

spirit delicious, a fate and a good fortune written, ere the first

man and woman were, by the gods whose whim had been to make all men

and women for sorrow and for joy.

But his mother put into his hand the ink-brush and placed under it,

on the table, the writing tablet.

“Paint,” said she, “the ideograph of TO MARRY.”

He obeyed, scarcely wondering, with the deft artistry of his race

and training painting the symbolic hieroglyphic.

“Resolve it,” commanded his mother.

Ah Kim looked at her, curious, willing to please, unaware of the

drift of her intent.

“Of what is it composed?” she persisted. “What are the three

originals, the sum of which is it: to marry, marriage, the coming

together and wedding of a man and a woman? Paint them, paint them

apart, the three originals, unrelated, so that we may know how the

wise men of old wisely built up the ideograph of to marry.”

And Ah Kim, obeying and painting, saw that what he had painted were

three picture-signs–the picture-signs of a hand, an ear, and a

woman.

“Name them,” said his mother; and he named them.

“It is true,” said she. “It is a great tale. It is the stuff of

the painted pictures of marriage. Such marriage was in the

beginning; such shall it always be in my house. The hand of the

man takes the woman’s ear, and by it leads her away to his house,

where she is to be obedient to him and to his mother. I was taken

by the ear, so, by your long honourably dead father. I have looked

at your hand. It is not like his hand. Also have I looked at the

ear of Li Faa. Never will you lead her by the ear. She has not

that kind of an ear. I shall live a long time yet, and I will be

mistress in my son’s house, after our ancient way, until I die.”

“But she is my revered ancestress,” Ah Kim explained to Li Faa.

He was timidly unhappy; for Li Faa, having ascertained that Mrs.

Tai Fu was at the temple of the Chinese AEsculapius making a food

offering of dried duck and prayers for her declining health, had

taken advantage of the opportunity to call upon him in his store.

Li Faa pursed her insolent, unpainted lips into the form of a half-

opened rosebud, and replied:

“That will do for China. I do not know China. This is Hawaii, and

in Hawaii the customs of all foreigners change.”

“She is nevertheless my ancestress,” Ah Kim protested, “the mother

who gave me birth, whether I am in China or Hawaii, O Silvery Moon

Blossom that I want for wife.”

“I have had two husbands,” Li Faa stated placidly. “One was a

pake, one was a Portuguese. I learned much from both. Also am I

educated. I have been to High School, and I have played the piano

in public. And I learned from my two husbands much. The pake

makes the best husband. Never again will I marry anything but a

pake. But he must not take me by the ear–“

“How do you know of that?” he broke in suspiciously.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy,” was the reply. “Mrs. Chang Lucy tells me

everything that your mother tells her, and your mother tells her

much. So let me tell you that mine is not that kind of an ear.”

“Which is what my honoured mother has told me,” Ah Kim groaned.

“Which is what your honoured mother told Mrs. Chang Lucy, which is

what Mrs. Chang Lucy told me,” Li Faa completed equably. “And I

now tell you, O Third Husband To Be, that the man is not born who

will lead me by the ear. It is not the way in Hawaii. I will go

only hand in hand with my man, side by side, fifty-fifty as is the

haole slang just now. My Portuguese husband thought different. He

tried to beat me. I landed him three times in the police court and

each time he worked out his sentence on the reef. After that he

got drowned.”

“My mother has been my mother for fifty years,” Ah Kim declared

stoutly.

“And for fifty years has she beaten you,” Li Faa giggled. “How my

father used to laugh at Yap Ten Shin! Like you, Yap Ten Shin had

been born in China, and had brought the China customs with him.

His old father was for ever beating him with a stick. He loved his

father. But his father beat him harder than ever when he became a

missionary pake. Every time he went to the missionary services,

his father beat him. And every time the missionary heard of it he

was harsh in his language to Yap Ten Shin for allowing his father

to beat him. And my father laughed and laughed, for my father was

a very liberal pake, who had changed his customs quicker than most

foreigners. And all the trouble was because Yap Ten Shin had a

loving heart. He loved his honourable father. He loved the God of

Love of the Christian missionary. But in the end, in me, he found

the greatest love of all, which is the love of woman. In me he

forgot his love for his father and his love for the loving Christ.

“And he offered my father six hundred gold, for me–the price was

small because my feet were not small. But I was half kanaka. I

said that I was not a slave-woman, and that I would be sold to no

man. My high-school teacher was a haole old maid who said love of

woman was so beyond price that it must never be sold. Perhaps that

is why she was an old maid. She was not beautiful. She could not

give herself away. My kanaka mother said it was not the kanaka way

to sell their daughters for a money price. They gave their

daughters for love, and she would listen to reason if Yap Ten Shin

provided luaus in quantity and quality. My pake father, as I have

told you, was liberal. He asked me if I wanted Yap Ten Shin for my

husband. And I said yes; and freely, of myself, I went to him. He

it was who was kicked by a horse; but he was a very good husband

before he was kicked by the horse.

“As for you, Ah Kim, you shall always be honourable and lovable for

me, and some day, when it is not necessary for you to take me by

the ear, I shall marry you and come here and be with you always,

and you will be the happiest pake in all Hawaii; for I have had two

husbands, and gone to high school, and am most wise in making a

husband happy. But that will be when your mother has ceased to

beat you. Mrs. Chang Lucy tells me that she beats you very hard.”

“She does,” Ah Kim affirmed. “Behold! He thrust back his loose

sleeves, exposing to the elbow his smooth and cherubic forearms.

They were mantled with black and blue marks that advertised the

weight and number of blows so shielded from his head and face.

“But she has never made me cry,” Ah Kim disclaimed hastily.

“Never, from the time I was a little boy, has she made me cry.”

“So Mrs. Chang Lucy says,” Li Faa observed. “She says that your

honourable mother often complains to her that she has never made

you cry.”

A sibilant warning from one of his clerks was too late. Having

regained the house by way of the back alley, Mrs. Tai Fu emerged

right upon them from out of the living apartments. Never had Ah

Kim seen his mother’s eyes so blazing furious. She ignored Li Faa,

as she screamed at him:

“Now will I make you cry. As never before shall I beat you until

you do cry.”

“Then let us go into the back rooms, honourable mother,” Ah Kim

suggested. “We will close the windows and the doors, and there may

you beat me.”

“No. Here shall you be beaten before all the world and this

shameless woman who would, with her own hand, take you by the ear

and call such sacrilege marriage! Stay, shameless woman.”

“I am going to stay anyway,” said Li Faa. She favoured the clerks

with a truculent stare. “And I’d like to see anything less than

the police put me out of here.”

“You will never be my daughter-in-law,” Mrs. Tai Fu snapped.

Li Faa nodded her head in agreement.

“But just the same,” she added, “shall your son be my third

husband.”

“You mean when I am dead?” the old mother screamed.

“The sun rises each morning,” Li Faa said enigmatically. “All my

life have I seen it rise–“

“You are forty, and you wear corsets.”

“But I do not dye my hair–that will come later,” Li Faa calmly

retorted. “As to my age, you are right. I shall be forty-one next

Kamehameha Day. For forty years I have seen the sun rise. My

father was an old man. Before he died he told me that he had

observed no difference in the rising of the sun since when he was a

little boy. The world is round. Confucius did not know that, but

you will find it in all the geography books. The world is round.

Ever it turns over on itself, over and over and around and around.

And the times and seasons of weather and life turn with it. What

is, has been before. What has been, will be again. The time of

the breadfruit and the mango ever recurs, and man and woman repeat

themselves. The robins nest, and in the springtime the plovers

come from the north. Every spring is followed by another spring.

The coconut palm rises into the air, ripens its fruit, and departs.

But always are there more coconut palms. This is not all my own

smart talk. Much of it my father told me. Proceed, honourable

Mrs. Tai Fu, and beat your son who is my Third Husband To Be. But

I shall laugh. I warn you I shall laugh.”

Ah Kim dropped down on his knees so as to give his mother every

advantage. And while she rained blows upon him with the bamboo

stick, Li Faa smiled and giggled, and finally burst into laughter.

“Harder, O honourable Mrs. Tai Fu!” Li Faa urged between paroxysms

of mirth.

Mrs. Tai Fu did her best, which was notably weak, until she

observed what made her drop the stick by her side in amazement. Ah

Kim was crying. Down both cheeks great round tears were coursing.

Li Faa was amazed. So were the gaping clerks. Most amazed of all

was Ah Kim, yet he could not help himself; and, although no further

blows fell, he cried steadily on.

“But why did you cry?” Li Faa demanded often of Ah Kim. “It was so

perfectly foolish a thing to do. She was not even hurting you.”

“Wait until we are married,” was Ah Kim’s invariable reply, “and

then, O Moon Lily, will I tell you.”

Two years later, one afternoon, more like a water-melon seed in

configuration than ever, Ah Kim returned home from a meeting of the

Chinese Protective Association, to find his mother dead on her

couch. Narrower and more unrelenting than ever were the forehead

and the brushed-back hair. But on her face was a withered smile.

The gods had been kind. She had passed without pain.

He telephoned first of all to Li Faa’s number but did not find her

until he called up Mrs. Chang Lucy. The news given, the marriage

was dated ahead with ten times the brevity of the old-line Chinese

custom. And if there be anything analogous to a bridesmaid in a

Chinese wedding, Mrs. Chang Lucy was just that.

“Why,” Li Faa asked Ah Kim when alone with him on their wedding

night, “why did you cry when your mother beat you that day in the

store? You were so foolish. She was not even hurting you.”

“That is why I cried,” answered Ah Kim.

Li Faa looked up at him without understanding.

“I cried,” he explained, “because I suddenly knew that my mother

was nearing her end. There was no weight, no hurt, in her blows.

I cried because I knew SHE NO LONGER HAD STRENGTH ENOUGH TO HURT

ME. That is why I cried, my Flower of Serenity, my Perfect Rest.

That is the only reason why I cried.”

WAIKIKI, HONOLULU.

June 16, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, London, Jack