Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

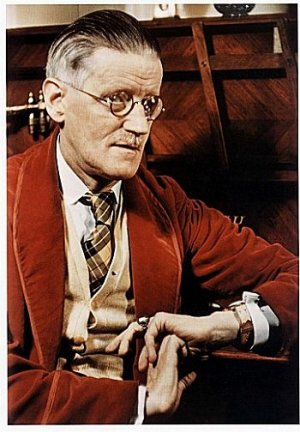

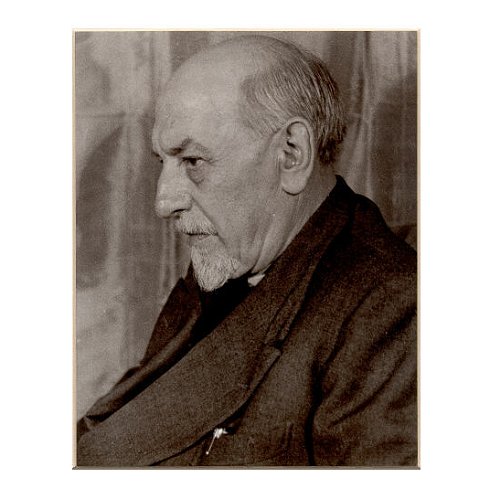

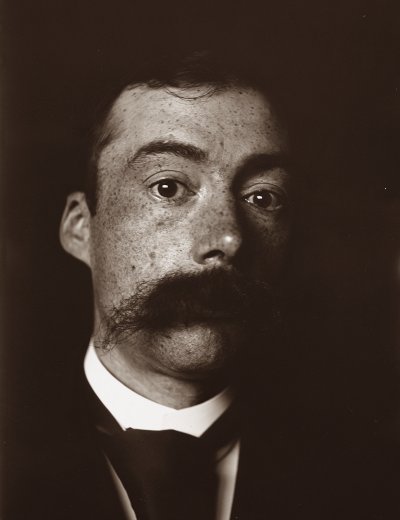

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Painful Case

Mr. James Duffy lived in Chapelizod because he wished to live as far as possible from the city of which he was a citizen and because he found all the other suburbs of Dublin mean, modern and pretentious. He lived in an old sombre house and from his windows he could look into the disused distillery or upwards along the shallow river on which Dublin is built. The lofty walls of his uncarpeted room were free from pictures. He had himself bought every article of furniture in the room: a black iron bedstead, an iron washstand, four cane chairs, a clothes-rack, a coal-scuttle, a fender and irons and a square table on which lay a double desk. A bookcase had been made in an alcove by means of shelves of white wood. The bed was clothed with white bedclothes and a black and scarlet rug covered the foot. A little hand-mirror hung above the washstand and during the day a white-shaded lamp stood as the sole ornament of the mantelpiece. The books on the white wooden shelves were arranged from below upwards according to bulk. A complete Wordsworth stood at one end of the lowest shelf and a copy of the Maynooth Catechism, sewn into the cloth cover of a notebook, stood at one end of the top shelf. Writing materials were always on the desk. In the desk lay a manuscript translation of Hauptmann’s Michael Kramer, the stage directions of which were written in purple ink, and a little sheaf of papers held together by a brass pin. In these sheets a sentence was inscribed from time to time and, in an ironical moment, the headline of an advertisement for Bile Beans had been pasted on to the first sheet. On lifting the lid of the desk a faint fragrance escaped, the fragrance of new cedarwood pencils or of a bottle of gum or of an overripe apple which might have been left there and forgotten.

Mr. Duffy abhorred anything which betokened physical or mental disorder. A medival doctor would have called him saturnine. His face, which carried the entire tale of his years, was of the brown tint of Dublin streets. On his long and rather large head grew dry black hair and a tawny moustache did not quite cover an unamiable mouth. His cheekbones also gave his face a harsh character; but there was no harshness in the eyes which, looking at the world from under their tawny eyebrows, gave the impression of a man ever alert to greet a redeeming instinct in others but often disappointed. He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glasses. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a predicate in the past tense. He never gave alms to beggars and walked firmly, carrying a stout hazel.

He had been for many years cashier of a private bank in Baggot Street. Every morning he came in from Chapelizod by tram. At midday he went to Dan Burke’s and took his lunch, a bottle of lager beer and a small trayful of arrowroot biscuits. At four o’clock he was set free. He dined in an eating-house in George’s Street where he felt himself safe from the society of Dublin’s gilded youth and where there was a certain plain honesty in the bill of fare. His evenings were spent either before his landlady’s piano or roaming about the outskirts of the city. His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.

He had neither companions nor friends, church nor creed. He lived his spiritual life without any communion with others, visiting his relatives at Christmas and escorting them to the cemetery when they died. He performed these two social duties for old dignity’s sake but conceded nothing further to the conventions which regulate the civic life. He allowed himself to think that in certain circumstances he would rob his hank but, as these circumstances never arose, his life rolled out evenly, an adventureless tale.

One evening he found himself sitting beside two ladies in the Rotunda. The house, thinly peopled and silent, gave distressing prophecy of failure. The lady who sat next him looked round at the deserted house once or twice and then said:

“What a pity there is such a poor house tonight! It’s so hard on people to have to sing to empty benches.”

He took the remark as an invitation to talk. He was surprised that she seemed so little awkward. While they talked he tried to fix her permanently in his memory. When he learned that the young girl beside her was her daughter he judged her to be a year or so younger than himself. Her face, which must have been handsome, had remained intelligent. It was an oval face with strongly marked features. The eyes were very dark blue and steady. Their gaze began with a defiant note but was confused by what seemed a deliberate swoon of the pupil into the iris, revealing for an instant a temperament of great sensibility. The pupil reasserted itself quickly, this half-disclosed nature fell again under the reign of prudence, and her astrakhan jacket, moulding a bosom of a certain fullness, struck the note of defiance more definitely.

He met her again a few weeks afterwards at a concert in Earlsfort Terrace and seized the moments when her daughter’s attention was diverted to become intimate. She alluded once or twice to her husband but her tone was not such as to make the allusion a warning. Her name was Mrs. Sinico. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather had come from Leghorn. Her husband was captain of a mercantile boat plying between Dublin and Holland; and they had one child.

Meeting her a third time by accident he found courage to make an appointment. She came. This was the first of many meetings; they met always in the evening and chose the most quiet quarters for their walks together. Mr. Duffy, however, had a distaste for underhand ways and, finding that they were compelled to meet stealthily, he forced her to ask him to her house. Captain Sinico encouraged his visits, thinking that his daughter’s hand was in question. He had dismissed his wife so sincerely from his gallery of pleasures that he did not suspect that anyone else would take an interest in her. As the husband was often away and the daughter out giving music lessons Mr. Duffy had many opportunities of enjoying the lady’s society. Neither he nor she had had any such adventure before and neither was conscious of any incongruity. Little by little he entangled his thoughts with hers. He lent her books, provided her with ideas, shared his intellectual life with her. She listened to all.

Sometimes in return for his theories she gave out some fact of her own life. With almost maternal solicitude she urged him to let his nature open to the full: she became his confessor. He told her that for some time he had assisted at the meetings of an Irish Socialist Party where he had felt himself a unique figure amidst a score of sober workmen in a garret lit by an inefficient oil-lamp. When the party had divided into three sections, each under its own leader and in its own garret, he had discontinued his attendances. The workmen’s discussions, he said, were too timorous; the interest they took in the question of wages was inordinate. He felt that they were hard-featured realists and that they resented an exactitude which was the produce of a leisure not within their reach. No social revolution, he told her, would be likely to strike Dublin for some centuries.

She asked him why did he not write out his thoughts. For what, he asked her, with careful scorn. To compete with phrasemongers, incapable of thinking consecutively for sixty seconds? To submit himself to the criticisms of an obtuse middle class which entrusted its morality to policemen and its fine arts to impresarios?

He went often to her little cottage outside Dublin; often they spent their evenings alone. Little by little, as their thoughts entangled, they spoke of subjects less remote. Her companionship was like a warm soil about an exotic. Many times she allowed the dark to fall upon them, refraining from lighting the lamp. The dark discreet room, their isolation, the music that still vibrated in their ears united them. This union exalted him, wore away the rough edges of his character, emotionalised his mental life. Sometimes he caught himself listening to the sound of his own voice. He thought that in her eyes he would ascend to an angelical stature; and, as he attached the fervent nature of his companion more and more closely to him, he heard the strange impersonal voice which he recognised as his own, insisting on the soul’s incurable loneliness. We cannot give ourselves, it said: we are our own. The end of these discourses was that one night during which she had shown every sign of unusual excitement, Mrs. Sinico caught up his hand passionately and pressed it to her cheek.

Mr. Duffy was very much surprised. Her interpretation of his words disillusioned him. He did not visit her for a week, then he wrote to her asking her to meet him. As he did not wish their last interview to be troubled by the influence of their ruined confessional they meet in a little cakeshop near the Parkgate. It was cold autumn weather but in spite of the cold they wandered up and down the roads of the Park for nearly three hours. They agreed to break off their intercourse: every bond, he said, is a bond to sorrow. When they came out of the Park they walked in silence towards the tram; but here she began to tremble so violently that, fearing another collapse on her part, he bade her good-bye quickly and left her. A few days later he received a parcel containing his books and music.

Four years passed. Mr. Duffy returned to his even way of life. His room still bore witness of the orderliness of his mind. Some new pieces of music encumbered the music-stand in the lower room and on his shelves stood two volumes by Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra and The Gay Science. He wrote seldom in the sheaf of papers which lay in his desk. One of his sentences, written two months after his last interview with Mrs. Sinico, read: Love between man and man is impossible because there must not be sexual intercourse and friendship between man and woman is impossible because there must be sexual intercourse. He kept away from concerts lest he should meet her. His father died; the junior partner of the bank retired. And still every morning he went into the city by tram and every evening walked home from the city after having dined moderately in George’s Street and read the evening paper for dessert.

One evening as he was about to put a morsel of corned beef and cabbage into his mouth his hand stopped. His eyes fixed themselves on a paragraph in the evening paper which he had propped against the water-carafe. He replaced the morsel of food on his plate and read the paragraph attentively. Then he drank a glass of water, pushed his plate to one side, doubled the paper down before him between his elbows and read the paragraph over and over again. The cabbage began to deposit a cold white grease on his plate. The girl came over to him to ask was his dinner not properly cooked. He said it was very good and ate a few mouthfuls of it with difficulty. Then he paid his bill and went out.

He walked along quickly through the November twilight, his stout hazel stick striking the ground regularly, the fringe of the buff Mail peeping out of a side-pocket of his tight reefer overcoat. On the lonely road which leads from the Parkgate to Chapelizod he slackened his pace. His stick struck the ground less emphatically and his breath, issuing irregularly, almost with a sighing sound, condensed in the wintry air. When he reached his house he went up at once to his bedroom and, taking the paper from his pocket, read the paragraph again by the failing light of the window. He read it not aloud, but moving his lips as a priest does when he reads the prayers Secreto. This was the paragraph:

DEATH OF A LADY AT SYDNEY PARADE

A PAINFUL CASE

Today at the City of Dublin Hospital the Deputy Coroner (in the absence of Mr. Leverett) held an inquest on the body of Mrs. Emily Sinico, aged forty-three years, who was killed at Sydney Parade Station yesterday evening. The evidence showed that the deceased lady, while attempting to cross the line, was knocked down by the engine of the ten o’clock slow train from Kingstown, thereby sustaining injuries of the head and right side which led to her death.

James Lennon, driver of the engine, stated that he had been in the employment of the railway company for fifteen years. On hearing the guard’s whistle he set the train in motion and a second or two afterwards brought it to rest in response to loud cries. The train was going slowly.

P. Dunne, railway porter, stated that as the train was about to start he observed a woman attempting to cross the lines. He ran towards her and shouted, but, before he could reach her, she was caught by the buffer of the engine and fell to the ground.

A juror. “You saw the lady fall?”

Witness. “Yes.”

Police Sergeant Croly deposed that when he arrived he found the deceased lying on the platform apparently dead. He had the body taken to the waiting-room pending the arrival of the ambulance.

Constable 57 corroborated.

Dr. Halpin, assistant house surgeon of the City of Dublin Hospital, stated that the deceased had two lower ribs fractured and had sustained severe contusions of the right shoulder. The right side of the head had been injured in the fall. The injuries were not sufficient to have caused death in a normal person. Death, in his opinion, had been probably due to shock and sudden failure of the heart’s action.

Mr. H. B. Patterson Finlay, on behalf of the railway company, expressed his deep regret at the accident. The company had always taken every precaution to prevent people crossing the lines except by the bridges, both by placing notices in every station and by the use of patent spring gates at level crossings. The deceased had been in the habit of crossing the lines late at night from platform to platform and, in view of certain other circumstances of the case, he did not think the railway officials were to blame.

Captain Sinico, of Leoville, Sydney Parade, husband of the deceased, also gave evidence. He stated that the deceased was his wife. He was not in Dublin at the time of the accident as he had arrived only that morning from Rotterdam. They had been married for twenty-two years and had lived happily until about two years ago when his wife began to be rather intemperate in her habits.

Miss Mary Sinico said that of late her mother had been in the habit of going out at night to buy spirits. She, witness, had often tried to reason with her mother and had induced her to join a League. She was not at home until an hour after the accident. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence and exonerated Lennon from all blame.

The Deputy Coroner said it was a most painful case, and expressed great sympathy with Captain Sinico and his daughter. He urged on the railway company to take strong measures to prevent the possibility of similar accidents in the future. No blame attached to anyone.

Mr. Duffy raised his eyes from the paper and gazed out of his window on the cheerless evening landscape. The river lay quiet beside the empty distillery and from time to time a light appeared in some house on the Lucan road. What an end! The whole narrative of her death revolted him and it revolted him to think that he had ever spoken to her of what he held sacred. The threadbare phrases, the inane expressions of sympathy, the cautious words of a reporter won over to conceal the details of a commonplace vulgar death attacked his stomach. Not merely had she degraded herself; she had degraded him. He saw the squalid tract of her vice, miserable and malodorous. His soul’s companion! He thought of the hobbling wretches whom he had seen carrying cans and bottles to be filled by the barman. Just God, what an end! Evidently she had been unfit to live, without any strength of purpose, an easy prey to habits, one of the wrecks on which civilisation has been reared. But that she could have sunk so low! Was it possible he had deceived himself so utterly about her? He remembered her outburst of that night and interpreted it in a harsher sense than he had ever done. He had no difficulty now in approving of the course he had taken.

As the light failed and his memory began to wander he thought her hand touched his. The shock which had first attacked his stomach was now attacking his nerves. He put on his overcoat and hat quickly and went out. The cold air met him on the threshold; it crept into the sleeves of his coat. When he came to the public-house at Chapelizod Bridge he went in and ordered a hot punch.

The proprietor served him obsequiously but did not venture to talk. There were five or six workingmen in the shop discussing the value of a gentleman’s estate in County Kildare They drank at intervals from their huge pint tumblers and smoked, spitting often on the floor and sometimes dragging the sawdust over their spits with their heavy boots. Mr. Duffy sat on his stool and gazed at them, without seeing or hearing them. After a while they went out and he called for another punch. He sat a long time over it. The shop was very quiet. The proprietor sprawled on the counter reading the Herald and yawning. Now and again a tram was heard swishing along the lonely road outside.

As he sat there, living over his life with her and evoking alternately the two images in which he now conceived her, he realised that she was dead, that she had ceased to exist, that she had become a memory. He began to feel ill at ease. He asked himself what else could he have done. He could not have carried on a comedy of deception with her; he could not have lived with her openly. He had done what seemed to him best. How was he to blame? Now that she was gone he understood how lonely her life must have been, sitting night after night alone in that room. His life would be lonely too until he, too, died, ceased to exist, became a memory, if anyone remembered him.

It was after nine o’clock when he left the shop. The night was cold and gloomy. He entered the Park by the first gate and walked along under the gaunt trees. He walked through the bleak alleys where they had walked four years before. She seemed to be near him in the darkness. At moments he seemed to feel her voice touch his ear, her hand touch his. He stood still to listen. Why had he withheld life from her? Why had he sentenced her to death? He felt his moral nature falling to pieces.

When he gained the crest of the Magazine Hill he halted and looked along the river towards Dublin, the lights of which burned redly and hospitably in the cold night. He looked down the slope and, at the base, in the shadow of the wall of the Park, he saw some human figures lying. Those venal and furtive loves filled him with despair. He gnawed the rectitude of his life; he felt that he had been outcast from life’s feast. One human being had seemed to love him and he had denied her life and happiness: he had sentenced her to ignominy, a death of shame. He knew that the prostrate creatures down by the wall were watching him and wished him gone. No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast. He turned his eyes to the grey gleaming river, winding along towards Dublin. Beyond the river he saw a goods train winding out of Kingsbridge Station, like a worm with a fiery head winding through the darkness, obstinately and laboriously. It passed slowly out of sight; but still he heard in his ears the laborious drone of the engine reiterating the syllables of her name.

He turned back the way he had come, the rhythm of the engine pounding in his ears. He began to doubt the reality of what memory told him. He halted under a tree and allowed the rhythm to die away. He could not feel her near him in the darkness nor her voice touch his ear. He waited for some minutes listening. He could hear nothing: the night was perfectly silent. He listened again: perfectly silent. He felt that he was alone.

James Joyce: A Painful Case

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

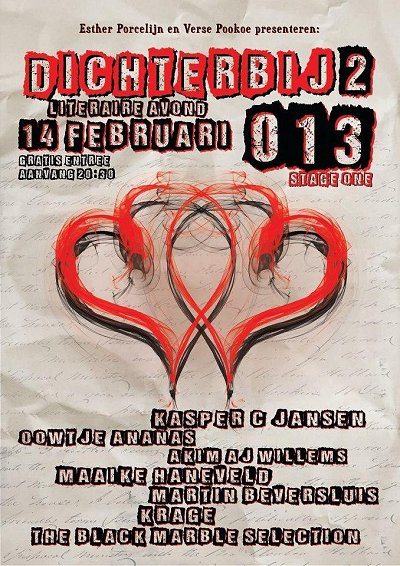

Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe presenteren: Dichterbij #2 + Kasper C Jansen + Oowtje Ananas + Akim AJ Willems + Maaike Haneveld + Martin Beversluis + Krage + The Black Marble Selection

do 14 feb 13

Poppodium 013 Tilburg

Tijdens deze valentijnsavond organiseren stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe de tweede editie van een nieuwe maandelijkse literaire avond genaamd: ‘Dichterbij’. De eerste editie vond plaats in de Rode Salon van De NWE Vorst. De avond zal een combinatie zijn van proza, poëzie en muziek met dichters en andere woordkunstenaars uit Tilburg en de rest van het land. Zowel beginnend talent als ervaren schrijvers krijgen de kans om het podium te betreden.

Na de sluiting van Ruimte-X (Ernest Potters) en het stoppen van Aardige Jongens (Martijn Neggers), voelde Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe zich geroepen om de literaire wereld van Tilburg in beweging te houden en ook een nieuw publiek aan te spreken met deze nieuwe avonden. Verse Pookoe en Esther Porcelijn nodigen u uit om gezellig langs te komen op deze gratis avond.

Locatie: Stage01 – Poppodium 013 Tilburg

Zaal open: 19:30 uur

Aanvang: 20:00 uur

Tickets: Gratis

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Vlezige mensen, wethouders, poppetjes, kastjes

Welkom iedereen! Het thema van vanavond is: ‘Verlichting’.

De stroming in de 17e en 18e eeuw die ons tot het inzicht heeft laten komen dat de Rede het enige instrument is om tot Waarheid te komen. Weg met het bijgeloof, weg met de onderdrukking van de kerk, weg met het feodale systeem, en op naar grondrechten, gelijkheid en vrijheid waarvoor vervolgens gestreden werd in de Franse Revolutie. Dit alles is uiteraard veroorzaakt door historici, filosofen en ontevreden burgers, maar niet enkel door hen. De Pamflettisten hebben zich een slag in de rondte gewerkt om iedereen te laten weten hoe vreselijk de adel was en dat de koning elke dag baadde in kinderbloed. Zij wisten met opruiende teksten, beschuldigingen, beledigingen en verdachtmakingen de burgerij voor zich te winnen. Ongeacht of de boodschap waarheid bevatte of niet.

Herkenbaar?

Wellicht dat we de pamflettisten van nu vanavond op het podium zullen zien.

Dan zullen we hen vast horen over wethouders van vroeger en van nu, en over andere mensen uit de politiek. Over hoe een of andere handeling van een of ander iemand exemplarisch is voor dit ‘dorp’ en haar mentaliteit.

Het kan ook zijn dat iemand in deze zaal hard wordt aangepakt. Maar niet té hard, het moet natuurlijk wel gezellig en grappig blijven. Maar om het grappig te laten zijn, moet het wel gaan over iemand die wij allemaal (persoonlijk) kennen, anders valt er niets te lachen. Als je dan niet lacht ben je de gebeten hond en dus iemand zonder humor.

Harde uitspraken moeten grappig zijn, anders zijn ze alleen maar pijnlijk! Jongens, lach dan, lach dan!

Het lijkt wel een formule. Een pamfletformule!

Eens kijken, wat zou de formule deze avond kunnen bevatten?

Ik gok dat het woord ‘dorp’ toch wel een aantal keer valt.

Wethouder van Cultuur Marjo Frenk is een goede kansmaker op een naamsvermelding denk ik.

Anton Dautzenberg komt vast weer met een sexuele verdachtmaking van iemand, misschien voormalig stadsdichter Cees van Raak die seks heeft gehad met de hond van Daan Taks? (Nachtdichter van Tilburg.) Wellicht betrekt hij er een landelijke bekendheid in, want dat onderscheid moet uiteraard gemaakt worden! Het onderscheid tussen de landelijke bekendheid versus het provincialisme dat noodzakelijk in die zin betrokken is als je een accent legt op lándelijke bekendheid. Hij wel, verdomme. Dan maar een grapje maken: Poep! Ha. Ha. Ha. Enig!

Misschien houdt Anton (zo mag ik ‘m noemen, zegt ook weer wat over mij, ik ken hem. Dat maakt mij iets meer immuun voor zijn harde uitspraken die mij mogelijk te wachten staan. Wauw!) eerder een betoog over iets met bloed en de nachtburgemeester Godelieve Engbersen. Iets over een moord die gepleegd is waarbij wederom de hond van Daan Taks betrokken was.

Luuk Koelman zal hoe dan ook de woede van heel het land op de hals halen met zijn column, dat moet haast wel. Als je de woede van bijna heel het land al op de hals hebt gehaald, met de column over Mariska Orbán-de Haas, dan moet je toch minstens het hele land boos maken wil je nog opvallen. Maar wij in de zaal zijn ‘insiders on the joke’ dus wij kunnen dan met een gerust hart zeggen dat de rest van het land zo kleinburgerlijk is en nooit iets snapt. “Hoe kun je die ironie nou niet inzien? On-be-grijpelijk”, fluistert ene Lidy uit Tilburg dan tegen haar man Hans; “Wij zijn dan nog behoorlijk open-minded, toch Hans?” “Gelukkig maar.”

Wat maakt het toch zo smakelijk, dat pakken op de persoon, de Ad Hominem?

“Polemiek!” Hoor ik Antonnetje en zijn billemaat Erik Hannema roepen in mijn hoofd.

Ja, polemiek jongens, polemiek! Het is een kunst, dat moet gezegd, maar bedrijf het dan ook! Polemiek betekent redetwisten. Daar hebben we het woord ‘rede’ dus weer. Diezelfde rede die ons tot de waarheid zou kunnen brengen. De twee deelnemers zouden het komen tot waarheid hoog in het vaandel hebben staan, waarom zou je anders redetwisten? Om je gelijk te halen misschien? Zou kunnen, maar een gelijk zonder daadwerkelijk gelijk lijkt mij weinig voldoenend. Misschien wordt deze kunst wel veel bedreven op avonden zoals deze uit een gevoel van nostalgie: “Vroeger kon men dit nog, vroeger was er nog iets om voor te strijden, vroeger waren er nog revoluties in het Westen!” Onrust stoken om mensen op te ruien en te motiveren. Maar, waarom zou je dan mensen persoonlijk pakken met fictieve gebeurtenissen of –verdachtmakingen?

Misschien omdat het te lang bespreken van de ware gebeurtenissen, fouten en terechte verdachtmakingen te pijnlijk en ongemakkelijk is. Het moet wel gezellig blijven en dus worden er een paar fictieve gebeurtenissen tussen de regels geplakt zodat de mogelijkheid dat de ware gebeurtenissen ook fictief zijn nog blijft bestaan.

We willen wel de roddels maar niet de confrontatie, niet echt. We willen alleen de smakelijke sappige details mits ze weinig lijken te zeggen over onszelf. Is ook makkelijker natuurlijk! De ander is gek, de ander is grappig.

Is het waar dat men vroeger dan wel eindeloos opzoek was naar de waarheid? Ik denk het niet, althans, niet meer dan nu. Ten tijde van de Franse Revolutie verzon de lage adel er ook op los, wat er maar nodig was om de burgers aan hun kant te krijgen. Dat dit lukte en uiteindelijk meer vrijheid tot stand bracht is een feit. Al waren de donkere tijden van de middeleeuwen iets minder donker dan zij ons tot op de dag van vandaag hebben doen denken. Maar zij deden dit met gevaar voor eigen leven, niet braaf in een zaal in Tilburg. Waarom zouden wij dan een hang hebben naar die revoluties van vroeger en de pamflettaal die daarmee samenhangt? Welke donkere tijden proberen wij te ontvluchten?

Kijk, Jace vd Ven (eerste stadsdichter van Tilburg) komt uit vroeger, dus hij hoeft het vroeger niet naar nu te trekken. Hij weet al hoe het toen was en kan hoogstens oprecht nostalgische gevoelens ervaren. Juist doordat hij uit vroeger komt weet hij ook dat de geschiedenis zich herhaalt. Hij kan zijn nootjes pakken, naar de show kijken en pogen iets universeels te schrijven als dichter. Want dat kan hij. Jace kan, en misschien wel hierdoor, gedichten maken die buiten de tijd staan. Dat is wat een goed gedicht doet.

Misschien dat Tom America ons nog een vieze film toont, met in een soundscape de naam van Burgermeester Noordanus in herhaling. Of iets met een jong Thais meisje, gespeeld door mij, dan kunnen we dat meteen voor het TilT-festival gebruiken, Tom! Theatermaker Peer de Graaf en dichter Martin Beversluis doen dan samen een interpretatieve dans, naakt uiteraard.

Nu, ik hoop dat u precies vaak genoeg genoemd wordt deze avond om belangrijk gevonden te worden, maar net te weinig om uw ziel ontbloot te voelen.

De formule zal het leren: Pastor Harm Schilder + grapje over piemeltjes van jonge jongens = hihi. Tilburg culturele hoofdstad + iets met de VVD + naamsbekendheid want ik ken d’n dieje – lekker gewoon gebleven = haha.

Deze avond gaat ons hopelijk enorm verlichten. Of de rede hier zegeviert kunt u allen zelf bepalen, we houden na afloop een opiniepeiling in het licht van: ‘uw stem is ook belangrijk’, dit past binnen het thema waar de pamflettisten zo voor gepamfletteerd hebben: Gelijkheid. Het bespotten van de poppetjes kan beginnen!

Het lucht vast wel op, dus in die zin wellicht…. Verlichting.

Esther Porcelijn, 19 jan 2013

(Column voorgedragen tijdens ‘Schuimt’, columnistenbijeenkomst met o.a. Anton Dautzenberg, Luuk Koelman, JACE vd Ven, en Tom America, in jazzpodium Paradox in Tilburg)

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Literaire avond “Dichterbij”

Donderdag 17 januari 2013

Theater De Nieuwe Vorst Tilburg

Op donderdag 17 januari organiseren stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe de eerste editie van een nieuwe maandelijkse literaire avond genaamd: ‘Dichterbij’.

De eerste editie zal plaatsvinden in de Rode Salon van Theater De Nieuwe Vorst.

De avond zal een combinatie zijn van proza, poëzie en muziek met dichters en andere woordkunstenaars uit Tilburg en de rest van het land.

Zowel beginnend talent als ervaren schrijvers krijgen de kans om het podium te betreden.

Na de sluiting van Ruimte-X en het stoppen van Aardige Jongens, voelde Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe zich geroepen om de literaire wereld van Tilburg in beweging te houden en ook een nieuw publiek aan te spreken met deze nieuwe avonden.

In deze eerste editie zullen onder anderen te zien zijn: Arnoud Rigter, Oowtje Ananas, Daan Taks, Martin Beversluis, Amber-Helena Reisig en Simon Mulder. Als afsluiter zal de band “The Liszt” optreden (Robert-Jan Gruijthuijzen, Ronald Herregraven, Tim Ruterink, Tom Delforterie).

De presentatie zal in handen zijn van de stadsdichter.

Locatie: Theater De Nieuwe Vorst Tilburg

Donderdag 17 januari 2013

Entree: Gratis

Aanvang: 19.30

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

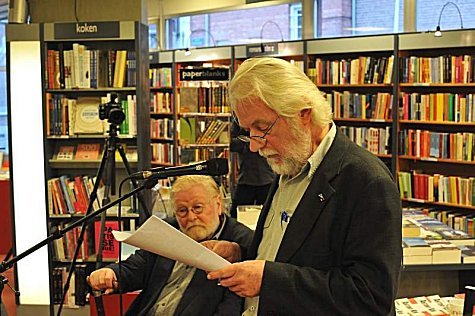

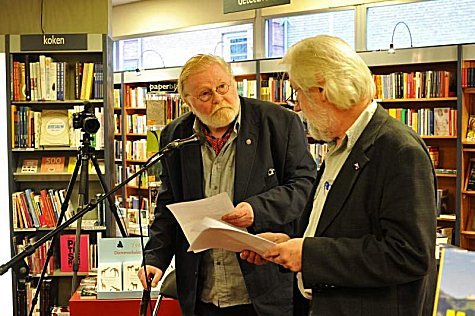

foto jef van kempen

Esther Porcelijn

NUT(S)

Ja. Ik geef het toe: Ik studeer filosofie. Guilty!! (zoals Peter Griffin het zegt in Family Guy). Ik ben die persoon die het advies van de ouders in de wind geslagen heeft en toch naar de toneelschool is gegaan en daarna naar het Departement Wijsbegeerte aan de UvT.

Ik weet het, je hoeft geen open deuren in te trappen: Ik ben geen advocaat of econoom aan het worden, Ergo: ik word niet erg rijk. Voor sommigen nog Ergoër: Ik volg geen nuttige studie. Ik ben voor velen dé vleeswording van de Linkse Kerk en beoefen dé linkse hobby der linkse hobby’s. Daarbij denken veel mensen dat filosofie vaag en esoterisch is; een studie waar je gewoon wat kletst over van alles en daar een 10 voor krijgt. Dus ik ben ook nog eens een vage linkse hobby-hippie.

Errug!! Pauper plebs. Nog erger misschien wel: Een toekomstige uitkeringstrekker en hoe dan ook een subsidieslurper. Nog Erruger!! Wow!

Op het departement woedt, tussen de studenten, onder leiding van enkelen die de moed echt stevig in de schoenen is gezakt, al een tijd een discussie, of een monoloog.. nee toch een discussie.

Daarin gaat het vaak over het nut van onze studie en van het vak van een filosoof. Tijdens lange gesprekken maakt iemand nét iets te vaak de grap: “Ach, we vinden een baan ondanks de filosofie, niet dankzíj.”

Dan, als iemand het zat wordt gaat het argumentenkanon aan. Nu zou ik de argumenten kunnen opnoemen, bijvoorbeeld dat o.a. Nederlandse politici, Amerikaanse presidenten, beroemde kunstenaars, journalisten en CEO’s van grote bedrijven filosofie hebben gestudeerd, maar dat is anekdotische argumentatie, en we weten allemaal dat een aantal individuele voorbeelden nog geen goed argument maakt.

Ik zou ook kunnen beginnen over hoe de democratie volledig is uitgedacht door filosofen en hoe de vrijheid die wij nu genieten alleen maar kan bestaan doordat een paar goede denkers de grenzen van die vrijheid hebben uitgedacht. Maar dan zou ik mijn professoren klakkeloos napraten, en in het verleden behaalde resultaten bieden geen garantie voor de toekomst, en meer van dat soort powerpoint-uitspraken. Of hoe exacte wetenschap ook niet exact is, voor als iemand beweert dat wat wij doen niet empirisch toetsbaar is en dus maar geklets. Maar dat is ook niks, iemand anders met hetzelfde probleem opzadelen als jijzelf. Misschien zou ik iets kunnen zeggen over communicatie- of vrijetijdswetenschappen, dat die studies pas écht nutteloos zijn, maar daar heeft niemand wat aan, laat staan dat het een argument is voor wat dan ook.

Beter kan ik iets proberen te zeggen, of nee, te duiden, wat betreft de termen ‘links’ en ‘nut’, alleen denk ik dat we daar toch een lang gesprek voor nodig hebben waarin we het vast ook zouden hebben over hoe wat ‘men’ vindt helemaal niet altijd waar hoeft te zijn, en over de invloed van de media en andere joop.nl onderwerpen.

Ik zou mijzelf fiks kunnen verdedigen uit pissigheid waaruit blijkt dat ik mij juist veel aantrek van wat men vindt, meer nog dan die abstracte groep ‘velen’ waar ik het over heb. Ik zou dan als ik echt boos word iets kunnen roepen als: “Alsof jij met je heftige hang naar rijkdom en dikke status echt gelukkig wordt of ook maar ergens verstand van kan hebben.”

Als ik dat zou doen dan zou ik dingen zeggen die ik helemaal niet vind en mij alleen maar meer stereotiep maken dan ik ben. Bovenal zou het de domste drogreden zijn. Ad hominem. Dat is pas echt errug. Ai.

Esther Porcelijn

(27) studeert filosofie aan de Universiteit van Tilburg. Ze is bovendien actrice en stadsdichter. Eerder gepubliceerd in UNIVERS 2012.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

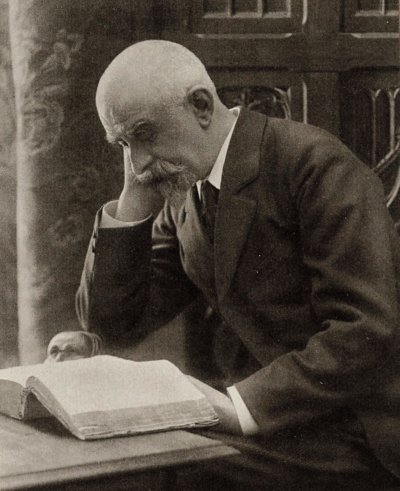

Ton van Reen

Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten

Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten.

Hoe is dat zo gekomen?

Lang geleden las Jef het gedicht DE MUS van Jan Hanlo. Hij las en beluisterde het goed.

Hij hoorde dit:

DE MUS

Tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp

etcetera.

Let op: het woord ETCETERA hoort bij het gedicht.

Dit etcetera betekent: eindeloos. Het gedicht DE MUS is dus een eeuwigdurend gedicht, dat overgaat van mus op mus.

Toen Jef het gedicht driemaal had gehoord, besloot hij vooral een vervolg te geven aan het laatste woord van het gedicht: etcetera.

Hij schafte vogeltjes aan om ten eeuwigen dage het gedicht van Jan rond te horen zingen.

Dat is nou eens een lesje leren uit de literatuur.

Etcetera, met een mensenleven lang durend vervolg op het getjielp.

Toevallig ben ik erachter gekomen waarom Jan Hanlo dit gedicht schreef.

In de donkere jaren van de wederopbouw na de oorlog gaf Jan les in de Engelse taal aan het instituut Schoevers voor aankomende secretaresses. En als het zo uitkwam gaf hij ook les in boekhouden.

Nu denken veel mensen dat zo’n bestaan voor een dichter vreemd is, maar het karakter van Jan Hanlo een beetje kennend, ik heb hem vaak meegemaakt, begrijp ik heel goed dat hij als dichter het dichtst bij zichzelf was als hij zijn kop vrij had in gebondenheid. De baan als leraar Engels en boekhouden beviel hem, omdat het zo absurd was. Tegen mijn achterneef Peter van Reen, illustrator en tekenaar bij de krant Het Volk, met wie hij bevriend was, zei hij dat alleen structuur het leven zinvol maakte.

Ten tijde van zijn gevangenschap in de klas en de leerlingen debet en credit leerde, moet hij ook naar buiten hebben verlangd. Vaak moet hij mussen aan het schoolraam hebben horen tjielpen en dat moet een zeker verlangen naar vrijheid hebben opgeroepen.

Terwijl hij de leerlingen sommen liet maken, luisterde hij naar de mus en, altijd op zoek naar structuur, zocht hij naar de structuur van het getjielp van het levenslied van de mus op de vensterbank van het klaslokaal.

Hij noteerde de klanken en hoorde zeven varianten, die eindeloos herhaald werden. Dat bracht hem ertoe het woord etcetera toe te voegen aan het klankgedicht over de mus.

Hij was blij, want hij had de structuur betrapt in het gezang van de mus.

Het bleek hem dat de mus niet zomaar wat zong, maar zichzelf oneindig bleef herhalen. Die eeuwige herhaling vatte hij samen in het woord etcetera.

Nu denken velen dat Jan Hanlo een liefhebber van vogels was. Dat was niet zo.

Als hij tijdens zijn lessen aan het Schoeversinstituut, naar buiten kijkend een kraai op een grasveld zou hebben gezien, had hij mogelijk het volgende gedicht geschreven:

Ka ka ka, kaka, krrr krrr , ka

krrr ka, ka krrr,

ka ka ka ka, krrrr , ka ka

krrr krrr krrr, ka

kaka, kaka, krrr, kaka, ka

kakaka, krrr ka, kakakaka, ka

ka

etcetera

Jef, die in de loop der jaren heeft geleerd om met vogels te praten zou dit gedicht als volgt hebben vertaald:

Wat doet die hond op ons grasveld

hij jaagt ons weg, die hond hoort hier niet

wat doet die hond, jaag hem weg

jaag hem de bomen in

die hond hoort hier niet, het gras is van ons

jaag hem de bomen in

wat doet die hond op ons gras

jaag hem weg

jaag hem de bomen in.

wat doet die hond op ons grasveld

wat?

etcetera

Zo is dus niet de kraai maar de mus heel toevallig in de Nederlandse literatuur terechtgekomen, maar had voor hetzelfde geld een kraai het onderwerp van een beroemd gedicht kunnen worden. Het had niet uitgemaakt. Het gedicht blijkt vooral bekend te zijn gebleven door het woord etcetera. Het ging Jan Hanlo in deze alleen om het woord etcetera. Heel tevreden schreef hij dat op, omdat hij de structuur van het vogelliedje had gevonden en hij begreep dat het gedicht eindeloos zou blijken te zijn.

Waarom was Hanlo zo uit op structuur? Waarom dwong hij zichzelf om alles wat hij deed gestructureerd aan te pakken? Tijdens mijn bezoeken aan Hanlo in het poorthuisje in Valkenburg, waar hij woonde in een eenkamervertrek, heb ik dat ontdekt. Hij legde zichzelf structuur op omdat hij geheel ongestructureerd was. En elke keer was hij blij om te ontdekken hoe anderen, in dit geval een mus, structuur aanbrachten in hun leven. Dat was ook de reden waarom hij in een piepklein huisje woonde. Een huis met meerdere vertrekken kon hij niet aan. Hij moest altijd alles onder handbereik hebben. Dat er zich spullen in andere vertrekken zouden bevinden, spullen die hij niet kon zien, was te veel van hem gevraagd.

Door zijn altijddurende jacht naar structuur beperkte hij zijn omgeving tot een steeds kleinere woonomgeving. In dat eenkamerwoninkje moest alles aanwezig zijn. Ook zijn motor.

Een andere reden om structuur aan te brengen was zijn armoe. Hij was zo arm als een rat. Wel beroemd in kleine kring, maar al heel lang zonder werk en af en toe vijf gulden vangend voor een gedicht in een literair tijdschrift. Het Fonds voor de Letteren bestond nog niet. Armoe dwong hem om heel gestructureerd met zijn geld om te gaan.

Waarom deze inleiding over Jan Hanlo als ik praat over het werk van Jef van Kempen?

Er moeten enkele dingen worden rechtgezet.

Jefs lievelingsgedicht is het gedicht De Mus van Jan Hanlo. Maar Jef heeft altijd gedacht dat Jan het gedicht heeft geschreven uit liefde voor de mus.

Niets is minder waar. Zaten er mussen op de vensterbank van zijn woninkje, dan joeg hij ze weg met een nijdig getik tegen het raam.

Het was Jan enkel en alleen te doen om het woord ETCETERA.

Herhaling van altijd hetzelfde: dat was structuur, dat was de structuur die hij voor zichzelf zocht.

Jef hoorde bij het lezen van het gedicht DE MUS inderdaad een tjielpende mus. En dacht dat Hanlo door dat ETCETERA het getjielp van de mus oneindig had willen horen. Waardoor het Jefs lievelingsgedicht werd omdat hij zelf ook oneindig naar het zingen van vogeltjes wilde luisteren. Om het gedicht van Jan Hanlo eindeloos te kunnen horen, schafte hij vogeltjes aan en zette zijn kleine tuin vol met vogelkooien om eindeloos het gedicht DE MUS te kunnen horen.

Vinken, sijsjes, paradijsvogeltjes, ik heb geen idee hoe die vogeltjes allemaal heten, maar vanaf de ontdekking van het gedicht DE MUS werd en wordt er in de kleine tuin van Jef dag en nacht, ETCETERA, gezongen.

Dames en heren, de inspiratie van een dichter kan uit onverwachte bronnen komen.

Jef ging verder dan Jan Hanlo. Niet alleen de vogeltjes en hun gezang boeien Jef, hij luistert naar de taal die zijn vogeltjes zingen. Naar de tekst van het vogellied. Vaak zit hij uren voor het hok, met een blocnote op schoot, te luisteren en streepjes te zetten. De dichter Jef van Kempen is de notulist van vogelcomposities.

Jef heeft ontdekt dat de taal van de vogels ingewikkeld is, maar ook dat er een bepaalde ordening in zit die lijkt op poëzie.

Dat eenmaal ontdekt hebbende blijkt dat, nu zijn verzamelde gedichten verschijnen, de meeste van zijn gedichten zijn ontstaan uit de aanzetten die hij heeft gemaakt in zijn blocnote met aantekeningen van het vogelgefluit in zijn tuin.

Om die vogeltjesteksten voor mensen zichtbaar en hoorbaar te maken, heeft Jef er mensenwoorden bij gevonden, zoals bij het gedicht van de kraaien die de hond op hun grasveld de boom in willen jagen Jef weet de vogeltjesteksten te vertalen naar het menselijk oor.

In aanzet zijn dus al zijn gedichten een vertaling van vogeltjesgefluit.

Zo blijkt dat Jef een dichter is geworden door het eindeloze woord ETCETERA van Jan Hanlo, die met dat woord een gedicht met eeuwigheidswaarde schiep.

Blij door het vertalen van de vogelliedjes in gedichten, ging Jef op zoek naar vergelijkingsmateriaal. Hij ontdekte de ene na de andere dichter die, elk op een eigen manier, de taal van vogels, olifanten, zebra’s en andere spraakmakende dieren opving en bewerkte voor het menselijk oor.

Er ontstond een grote collectie poëzie in huize Van Kempen, tot de kasten ervan uitpuilden. Jef besloot de gedichten die hij in zo’n prachtige vertalingen uit de meest uiteenlopende talen vond, uit te venten naar anderen.

Kortom, hij wilde anderen deelgenoot maken van het ETCETERA van Jan Hanlo.

Zo ontstond zijn weblog KEMPIS.nl.

In alle talen van de wereld vind je op zijn weblog gedichten van poëten, die net als Hanlo op zoek zijn naar iets wat aanvankelijk niet te begrijpen is, maar door de vertaling of de hertaling van de dichter begrijpelijk wordt.

Hanlo, die van kind af aan verdwaald was in het bestaan, was op zoek naar structuur in zijn leven. Pierre Kemp, altijd in het zwart gekleed, was juist op zoek naar kleur ter compensatie van zijn zwart gemoed. Vinkenoog was op zoek naar de structuur van het telefoonboek, omdat hij met alle mensen in de wereld in gesprek wilde blijven. Rilke was altijd op zoek naar de geluiden van de liefde.

Elke dichter blijkt op zoek te zijn naar iets dat aanvankelijk voor hem geheimzinnig is en dat hij wil bewoorden, waardoor hij er vertrouwd mee raakt.

Zo is Jef de verklanker geworden van de vogeltjestaal, maar ook van de taal van zijn omgeving. En dat is, in de ruimste zin, de stad Tilburg.

Ik besluit met een gedicht uit de bundel van Jef dat hij ook zelf heeft terugvertaald naar de taal van de vogels:

LANDSCHAP

Duizend kraaien

in de oude berk

tekenen

de grijze lucht

Deze leegte

had ik

niet vermoed

En nu het gedicht zoals het door Jef aan de vogels wordt verteld:

Bliep bliep tjiep, rrrrr

tjielp tjielp piep

piep piep piep piep

tjielp piep piep

rrrrr rrrrr piep tjielp piep

pieppiep rrrrrrr

hiep hiep tjielp piep

pieppiep piep rrrrrrrr

piep

etcetera

Zo vertelt Jef in de in hem opkomende gedichten aan de Tilburgse vogeltjes. De vogeltjes die in zijn tuintje zitten, de vogeltjes in het struikgewas rond de Hasseltse Kapel, het vogeltje dat doorklinkt in het gefluit van een vrolijke student op de fiets op weg naar school.

Kortom, voor al het gezang en getjielp dat Tilburg heet.

Jef heeft goed naar Jan Hanlo geluisterd. Hij heeft goed naar de vogeltjes geluisterd.

Wie Jef door Tilburg ziet dwalen en hem vreemde klanken hoort uitstoten, moet niet denken dat hij gek geworden is. Hij communiceert met de vogels.

ETCETERA. En dat nog vele jaren.

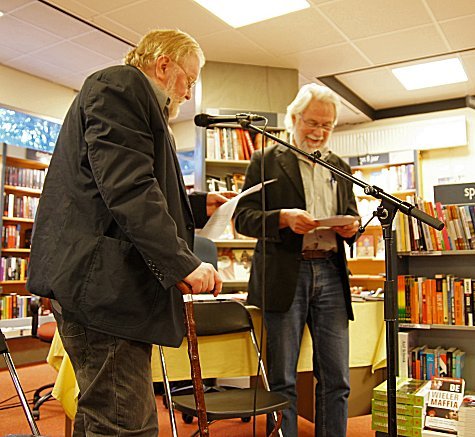

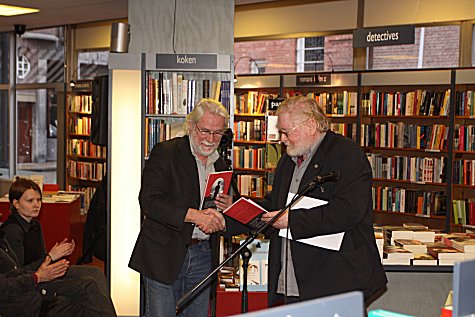

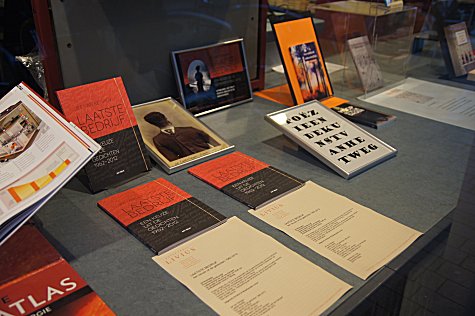

Op zondag 16 december 2012 vond in Boekhandel Livius in Tilburg de presentatie plaats van de nieuwe bundel van Jef van Kempen: Laatste bedrijf. Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012. Op die bijeenkomst ontving Jef van Kempen uit handen van burgemeester Peter Noordanus de grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg voor zijn verdiensten op het gebied van literatuur en cultuur. Ton van Reen las zijn verhaal: ‘Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten’ voor.

Jef van Kempen: Laatste Bedrijf. Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012. Uitgeverij Art Brut – ISBN: 978-90-76326-06-1 / 68 pag. – 12,50 euro – geïllustreerd, 24×15 cm / Gedichten en illustraties van Jef van Kempen / Vormgeving Michiel Leenaars / In de bundel zijn tevens een aantal bijdragen opgenomen van Julia Origo, Monica Richter en J.A. Woolf.

Foto’s: Hans Hermans, Joep Eijkens, Peter IJsenbrant

fleursdumal.nl m a g a z i n e

More in: Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

4

Turn the handle; I have turned it. I have kept my word: to the end. But the vengeance that I sought to accomplish upon the obligation imposed on me, as the slave of a machine, to serve up life to my machine as food, life has chosen to turn back upon me. Very good. No one henceforward can deny that I have now arrived at perfection.

As an operator I am now, truly, perfect.

About a month after the appalling disaster which is still being discussed everywhere, I bring these notes to an end.

A pen and a sheet of paper: there is no other way left to me now in which I can communicate with my fellow-men. I have lost my voice; I am dumb now for ever. Elsewhere in these notes I have written: “I suffer from this silence of mine, into which everyone comes, as into a place of certain hospitality. ‘I should like now my silence to close round me altogether’.” Well, it has closed round me. I could not be better qualified to act as the servant of a machine.

But I must tell you the whole story, as it happened.

The wretched fellow went, next morning, to Borgalli to complain forcibly of the ridiculous figure which, as he was informed, Polacco intended to make him cut with these precautions.

He insisted at all costs that the orders should be cancelled, offering to give them all a specimen, if they needed it, of his well-known skill as a marksman. Polacco excused himself to Borgalli, saying that he had taken these measures not from any want of confidence in Nuti’s courage or sureness of eye, but from prudence, knowing Nuti to be extremely nervous, as for that matter he was shewing himself to be at that moment by uttering this excited protest, instead of the grateful, friendly thanks which Polacco had a right to expect from him.

“Besides,” he unfortunately added, pointing to me, “you see, Commendatore, there’s Gubbio here too, who has to go into the cage….”

The poor wretch looked at me with such contempt that I immediately turned upon Polacco, exclaiming:

“No, no, my dear fellow! Don’t bother about me, please! You know very well that I shall go on quietly turning my handle, even if I see this gentleman in the jaws and claws of the beast!”

There was a laugh from the actors who had gathered round to listen; whereupon Polacco shrugged his shoulders and gave way, or pretended to give way. Fortunately for me, as I learned afterwards, he gave secret instructions to Fantappiè and one of the others to conceal their weapons and to stand ready for any emergency. Nuti went off to his dressing-room to put on his sporting clothes; I went to the Negative Department to prepare my machine for its meal. Fortunately for the company, I drew a much larger supply of film than would be required, to judge approximately by the length of the scene. When I returned to the crowded lawn, by the side of the enormous cage, set with a forest scene, the other cage, with the tiger inside it, had already been carried out and placed so that the two cages opened into one another. It only remained to pull up the door of the smaller cage.

Any number of actors from the four companies had assembled on either side, close to the cage, so that they could see between the tree trunks and branches that concealed its bars. I hoped for a moment that the Nestoroff, having secured her object, would at least have had the prudence not to come. But there she was, alas!

She stood apart from the crowd, a little way off, with Carlo Ferro, dressed in bright green, and was smiling as she repeatedly nodded her head in agreement with what Ferro was saying to her, albeit from the grim attitude in which he stood by her side it seemed evident that such a smile was not the appropriate answer to his words. But it was meant for the others, that smile, for all of us who stood watching her, and was also for me, a brighter smile, when I fixed my gaze on her; and it said to me once again that she was not afraid of anything, because the greatest possible evil for her I already knew: she had it by her side–there it was–Ferro; he was her punishment, and to the very end she I was determined, with that smile, to taste its, full flavour in the coarse words which he was probably addressing to her at that moment.

Taking my eyes from her, I sought those of Nuti. They were clouded. Evidently he too had caught sight of the Nestoroff there in the distance; but he chose to pretend that he had not. His face had grown stiff. He made an effort to smile, but smiled with his lips alone, a faint, nervous smile, at what some one was saying to him. With his black velvet cap on his head, with its long peak, his red coat, a huntsman’s brass horn slung over his shoulder, his white buckskin breeches fitting close to his thighs; booted and spurred, rifle in hand: he was ready.

The door of the big cage, through which ha and I were to enter, was opened from outside; to help us to climb in, two stage hands placed a pair of steps beneath it. He entered the cage first, then I. While I was setting up my machine on its tripod, which had been handed to me through the door of the cage, I noticed that Nuti first of all knelt down on the spot marked out for him, then rose and went across to thrust apart the boughs at one side of the cage, as though he were making a loophole there. I alone was in a position to ask him:

“Why?”

But the state of feeling that had grown up between us did not allow of our exchanging a single word at this stage. His action might therefore have been interpreted by me in several ways, which would have left me uncertain at a moment when the most absolute and precise certainty was essential. And then it was just as though Nuti had not moved at all; not only did I not think any more about his action, it was exactly as though I had not even noticed it.

He took his stand on the spot marked out for him, raising his rifle; I gave the signal:

“Ready.”

We heard from the other cage the sound of the door being pulled up. Polacco, perhaps seeing the animal begin to move towards the open door, shouted amid the silence:

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

And I began to turn the handle, with my eyes on the tree trunks in the background, through which the animal’s head was now protruding, lowered, as though peering out to explore the country; I saw that head slowly drawn back, the two forepaws remain firm, close together, and the hindlegs gradually, silently gather strength and the back rise in an arch in readiness for the spring. My hand was impassively keeping the time that I had set for its movement, faster, slower, dead slow, as though my will had flowed down–firm, lucid, inflexible–into my wrist, and from there had assumed entire control, leaving my brain free to think, my heart to feel; so that my hand continued to obey even when with a pang of terror I saw Nuti take his aim from the beast and slowly turn the muzzle of his rifle towards the spot where a moment earlier he had opened a loophole among the boughs, and fire, and the tiger immediately spring upon him and become merged with him, before my eyes, in a horrible writhing mass. Drowning the most deafening shouts that came from all the actors outside the cage as they ran instinctively towards the Nestoroff who had fallen at the shot, drowning the cries of Carlo Ferro, I heard there in the cage the deep growl of the beast and the horrible gasp of the man as he lay helpless in its fangs, in its claws, which were tearing his throat and chest; I heard, I heard, I kept on hearing above that growl, above that gasp, the continuous ticking of the machine, the handle of which my hand, alone, of its own accord, still kept on turning; and I waited for the beast to spring next upon me, having brought him down; and the moments of waiting seemed to me an eternity, and it seemed to me that throughout eternity I had been counting them, as I turned, still turned the handle, powerless to stop, when finally an arm was thrust in between the bars, carrying a revolver, and fired a shot point blank into the tiger’s ear over the mangled corpse of Nuti; and I was pulled back and dragged from the cage with the handle of the machine so tightly clasped in my fist that it was impossible at first to wrest it from me. I uttered no groan, no cry: my voice, from terror, had perished in my throat for ever.

Well, I have rendered the firm a service from which they will reap a fortune. As soon as I was able, I explained to the people who gathered round me terror-struck, first of all by signs, then in writing, that they were to take good care of the machine, which had been wrenched from my hand: that machine had in its maw the life of a man; I had given it that life to eat to the very last, until the moment when that arm had been thrust in to kill the tiger. There was a fortune to be extracted from this film, what with the enormous publicity and the morbid curiosity which the sordid atrocity of the drama of that slaughtered couple would everywhere arouse.

Ah, that it would fall to my lot to feed literally on the life of a man one of the many machines invented by man for his pastime, I could never have guessed. The life which this machine has devoured was naturally no more than it could be in a time like the present, in an age of machines; a production stupid in one aspect, mad in another, inevitably, and in the former more, in the latter rather less stamped with a brand of vulgarity.

I have found salvation, I alone, in my silence, with my silence, which has made me thus–according to the standard of the times–perfect. My friend Simone Pau will not understand this, more and more determined to drown himself in ‘superfluity’, the perpetual inmate of a Casual Shelter. I have already secured a life of ease with the compensation which the firm has given me for the service I have rendered it, and I shall soon be rich with the royalties which have been assigned to me from the hire of the monstrous film. It is true that I shall not know what to do with these riches; but I shall not reveal my embarrassment to anyone; least of all to Simone Pau, who comes every day to shake me, to abuse me, in the hope of forcing me out of this inanimate silence, which makes him furious. He would like to see me weep, would like me at least with my eyes to shew distress or anger; to make him understand by signs that I agree with him, that I too believe that life is there, in that ‘superfluity’ of his. I do not move an eyelid; I sit gazing at him, rigid, motionless, until he flies from the house in a rage. Poor Cavalena, from anoher angle, is studying on my behalf textbooks of nervous pathology, suggests injections and electric batteries, hovers round me to persuade me to agree to a surgical operation on my vocal chords; and Signorina Luisetta, penitent, heartbroken at my calamity, in which she chooses to detect an element of heroism, timidly lets me see now that she would like to hear issue, if not from my lips, at any rate from my heart a “yes” for herself.

No, thank you. Thanks to everybody. I have had enough. I prefer to remain like this. The times are what they are; life is what it is; and in the sense that I give to my profession, I intend to go on as I am–alone, mute and impassive–being the operator.

Is the stage set?

“Are you ready? Shoot….”

THE END

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

3

And now, God willing, we have reached the end. Nothing remains now save the final picture of the killing of the tiger.

The tiger: yes, I prefer, if I must be distressed, to be distressed over her; and I go to pay her a visit, standing for the last time in front of her cage.

She has grown used to seeing me, the beautiful creature, and does not stir. Only she wrinkles her brows a little, annoyed; but she endures the sight of me as she endures the burden of this sunlit silence, lying heavy round about her, which here in the cage is impregnated with a strong bestial odour. The sunlight enters the cage and she shuts her eyes, perhaps to dream, perhaps so as not to see descending ‘upon her the stripes of shadow cast by the iron bars. Ah, she must be tremendously bored with life also; bored, too, with my pity for her; and I believe that to make it cease, with a fit reward, she would gladly devour me. This desire, which she realises that the bars prevent her from satisfying, makes her heave a deep sigh; and since she is lying outstretched, her languid head drooping on one paw, I see, when she sighs, a cloud of dust rise from the floor of the cage.

Her sigh, really distresses me, albeit I understand why she has emitted it; it is her sorrowful recognition of the deprivation to which she has been condemned of her natural right to devour man, whom she has every reason to regard as her enemy.

“To-morrow,” I tell her. “To-morrow, my dear, this torment will be at an end. It is true that this torment still means something to you, and that, when it is over, nothing will matter to you any more. But if you have to choose between this torment and nothing, perhaps nothing is preferable! A captive like this, far from your savage haunts, powerless to tear anyone to pieces, or even to frighten him, what sort of tiger are you? Hark! They are making ready the big cage out there…. You are accustomed already to hearing these hammer-blows, and pay no attention to them. In this respect, you see, you are more fortunate than man: man may think, when he hears the hammer-blows: ‘There, those are for me; that is the undertaker, getting my coffin ready.’ You are already there, in your coffin, and do not know it: it will be a far larger cage than this; and you will have the comfort of a touch of local colour there too: it will represent a glade in a forest. The cage in which you now are will be carried out there and placed so that it opens into the other. A stage hand will climb on the roof of this cage, and pull up the door, while another man opens the door of the other cage; and you will then steal in between the tree trunks, cautious and wondering. But immediately you will notice a curious ticking noise. Nothing! It will be I, winding my machine on its tripod; yes, I shall be in the cage too, beside you; but don’t pay any attention to me! Do you see? Standing a little way in front of me is another man, another man who takes aim at you and fires, ah! there you are on the ground, a dead weight, brought down in your spring…. I shall come up to you; with no risk to the machine, I shall register your last convulsions, and so good-bye!”

If it ends like that…

This evening, on coming out of the Positive Department, where, in view of Borgalli’s urgency, I have been lending a hand myself in the developing and joining of the sections of this monstrous film, I saw Aldo Nuti advancing upon me with the unusual intention of accompanying me home. I at once observed that he was trying, or rather forcing himself not to let me see that he had something to say to me.

“Are you going home?”

“Yes.”

“So am I.”

When we had gone some distance he asked:

“Have you been in the rehearsal theatre to-day?”

“No. I’ve been working downstairs, in the dark room.”

Silence for a while. Then he made a painful effort to smile, with what he intended for a smile of satisfaction.

“They were trying my scenes. Everyone was pleased with them. I should never have imagined that they would come out so well. One especially.

I wish you could have seen it.”

“Which one?”

“The one that shews me by myself for a minute, close up, with a finger on my lips, like this, engaged in thinking. It lasts a little too long, perhaps… my face is a little too prominent … and my eyes…. You can count my eyelashes. I thought I should never disappear from the screen.”

I turned to look at him; but he at once took refuge in an obvious reflexion:

“Yes!” he said. “Curious the effect our own appearance has on us in a photograph, even on a plain card, when we look at it for the first time. Why is it?”

“Perhaps,” I answered, “because we feel that we are fixed there in a moment of time which no longer exists in ourselves; which will remain, and become steadily more remote.”

“Perhaps!” he sighed. “Always more remote for us….”

“No,” I went on, “for the picture as well. The picture ages too, just as we gradually age. It ages, although it is fixed there for ever in that moment; it ages young, if we are young, because that young man in the picture becomes older year by year with us, in us.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“It is quite easy to understand, if you will think a little. Just listen: the time, there, of the picture, does not advance, does not keep moving on, hour by hour, with us, into the future; you expect it to remain fixed at that point, but it is moving too, in the opposite direction; it recedes farther and farther into the past, that time. Consequently the picture itself is a dead thing which as time goes on recedes gradually farther into the past: and the younger it is the older and more remote it becomes.”

“Ah, yes, I see what you mean…. Yes, yes,” he said. “But there is something sadder still. A picture that has grown old young and empty.”

“How do you mean, empty?”

“The picture of somebody who has died young.”

I again turned to look at him; but he at once added:

“I have a portrait of my father, who died quite young, at about my age; so long ago that I don’t remember him. I have kept it reverently, this picture of him, although it means nothing to me. It has grown old too, yes, receding, as you say, into the past. But time, in ageing the picture, has not aged my father; my father has not lived through this period of time. And he presents himself before me empty, devoid of all the life that for him has not existed; he presents himself before me with his old picture of himself as a young man, which says nothing to me, which cannot say anything to me, because he does not even know that I exist. It is, in fact, a portrait he had made of himself before he married; a portrait, therefore, of a time when he was not my father. I do not exist in him, there, just as all my life has been lived without him.”

“It is sad….”

“Sad, yes. But in every family, in the old photograph albums, on the little table by the sofa in every provincial drawing-room, think of all the faded portraits of people who no longer mean anything to us, of whom we no longer know who they were, what they did, how they died….”

All of a sudden he changed the subject to ask me, with a frown:

“How long can a film be made to last?”

He no longer turned to me as to a person with whom he took pleasure in conversing; but in my capacity as an operator. And the tone of his voice was so different, the expression of his face had so changed that I suddenly felt rise up in me once again that contempt which for some time past I have been cherishing for everything and everybody. Why did he wish to know how long a film could last? Had he attached himself to me to find out this? Or from a desire to make my flesh creep, leaving me to guess that he intended to do something rash that very day, so that our walk together should leave me with a tragic memory or a sense of remorse?

I felt tempted to stop short in front of him and to shout in his face:

“I say, my dear fellow, you can drop all that with me, because I don’t take the slightest interest in you! You can do all the mad things you please, this evening, to-morrow: I shan’t stir! You may perhaps have asked me how long a film can last to make me think that you are leaving behind you that picture of yourself with your finger on your lips? And you think perhaps that you are going to fill the whole world with pity and terror with that enlarged picture, in which ‘they can count your eyelashes’? How long do you expect a film to last?”

I shrugged my shoulders and answered:

“It all depends upon how often it is used.”

He too from the change in my tone must have realised that my attitude towards him had changed also, and he began to look at me in a way that troubled me.

The position was this: he was still here on earth a petty creature. Useless, almost a nonentity; but he existed, and was walking beside me, and was suffering. It was true that he was suffering, like all the rest of us, from life which is the true malady of us all. He was suffering for no worthy reason; but whose fault was it if he had been born so petty? Petty as he was, he was suffering, and his suffering was great for him, however unworthy…. It was from life that he suffered, from one of the innumerable accidents of life, which had fallen upon him to take from him the little that he had in him and rend end destroy him! At the moment he was here, Etili walking by my side, on a June evening, the sweetness of which he could not taste; to-morrow perhaps, since life had so turned against him, he would no longer exist: those legs of his would never be set in motion again to walk; he would never see again this avenue along which we were going; and he would never again clothe his feet in those fine patent leather shoes and those silk socks, would never again take pleasure, even in the height of his desperation, as he stood before the glass of his wardrobe every morning, in the elegance of the faultless coat upon his handsome slim body which I could put out my hand now and touch, still living, conscious, by ray side.

“Brother….”

No, I did not utter that word. There are certain words that we hear, in a fleeting moment; we do not say them. Christ could say them, who was not dressed like me and was not, like me, an operator. Amid a human society which delights in a cinematographic show and tolerates a profession like mine, certain words, certain emotions become ridiculous.

“If I were to call this Signor Nuti ‘brother’,” I thought, “he would take offence; because… I may have taught him a little philosophy as to pictures that grow old, but what am I to him? An operator: a hand that turns a handle.”

He is a “gentleman,” with madness already latent perhaps in the ivory box of his skull, with despair in his heart, but a rich “titled gentleman” who can well remember having known me as a poor student, a humble tutor to Giorgio Mirelli in the villa by Sorrento. He intends to keep the distance between me and himself, and obliges me to keep it too, now, between him and myself: the distance that time and my profession have created. Between him and me, the machine.

“Excuse me,” he asked, just as we were reaching the house, “how will you manage to-morrow about taking the scene of the shooting of the tiger?”

“It is quite easy,” I answered. “I shall be standing behind you.”

“But won’t there be the bars of the cage, all the plants in between?”

“They won’t be in my way. I shall be inside the cage with you.”

He stood and stared at me in surprise:

“You will be inside the cage too?”

“Certainly,” I answered calmly.

“And if… if I were to miss?”

“I know that you are a crack shot. Not that it will make any difference. To-morrow all the actors will be standing round the cage, looking on. Several of them will be armed and ready to fire if you miss.”

He stood for a while lost in thought, as though this information had annoyed him.

Then: “They won’t fire before I do?” he said.

“No, of course not. They will fire if it is necessary.”

“But in that case,” he asked, “why did that fellow… that Signor Ferro insist upon all those conditions, if there is really no danger?”

“Because in Ferro’s case there might perhaps not have been all those others, outside the cage, armed.”

“Ah! Then they are for me? They have taken these precautions for me? How ridiculous! Whose doing is it? Yours, perhaps?”

“Mine, no. What have I got to do with it?”

“How do you know about it, then?”

“Polacco said so.”

“Said so to you? Then it was Polacco? Ah, I shall have something to say to him to-morrow morning! I won’t have it, do you understand? I won’t have it!”

“Are you addressing me?”

“You too!”

“Dear Sir, let me assure you that what you say leaves me perfectly indifferent: hit or miss your tiger; do all the mad things you like inside the cage: I shall not stir a finger, you may be sure of that. Whatever happens, I shall remain quite impassive and go on turning my handle. Bear that in mind, if you please!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (33)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

2

Trapped. That is all. This and this only is what Nestoroff wished–that it should be he who entered the cage.

With what object? That seems to me easily understood, after the way in which she has arranged things: that is to say that everyone, first of all, heaping contempt upon Carlo Ferro whom she had persuaded or forced to go away, should insist that there was no danger involved in entering the cage, so that afterwards the challenge of Nuti’s offer to enter it should seem all the more ridiculous, and, by the laughter with which that challenge was greeted, the other’s self-esteem might emerge if not unscathed still with the least possible damage; with no damage at all, indeed, since, with the malign satisfaction which people feel on seeing a poor bird caught in a snare, that the snare in question was not a pleasant thing everyone is now prepared to admit; all the more credit, therefore, to Ferro who has managed to free himself from it at this sparrow’s expense. In short, this to my mind is clearly what she wished: to take in Nuti, by shewing him her heartfelt determination to spare Ferro even a trifling inconvenience and the mere shadow of a remote danger, such as that of entering a cage and firing at an animal which everyone says is cowed by all these months of captivity. There: she has taken him neatly by the nose and amid universal laughter has led him into the cage.

Even the most moral of moralists, unintentionally, between the lines of their fables, allow us to observe their keen delight in the cunning of the fox, at the expense of the wolf or the rabbit or the hen: and heaven only knows what the fox represents in those fables! The moral to be drawn from them is always this: that the loss and the ridicule are borne by the foolish, the timid, the simple, and that the thing to be valued above all is therefore cunning, even when the fox fails to reach the grapes and says that they are sour. A fine moral! But this is a trick that the fox is always playing on the moralists, who, do what they may, can never succeed in making him cut a sorry figure. Have you laughed at the fable of the fox and the grapes? I never did. Because no wisdom has ever seemed to me wiser than this, which teaches us to cure ourselves of every desire by despising its object.

This, you understand, I am now saying of myself, who would like to be a fox and am not. I cannot find it in me to say sour grapes to Signorina Luisetta. And that poor child, whose heart I have not been able to reach, here she is doing everything in her power to make me, in her company, lose my reason, my calm impassivity, abandon the fine wise course which I have repeatedly declared my intention of following, in short all my boasted ‘inanimate silence’. I should like to despise her, Signorina Luisetta, when I see her throwing herself away like this upon that fool; I cannot. The poor child can no longer

sleep, and comes to tell me so every morning in my room, with eyes that change in colour, now a deep blue, now a pale green, with pupils that now dilate with terror, now contract to a pair of pin-points which seem stabbed by the most acute anguish.

I say to her: “You don’t sleep? Why not?” prompted by a malicious desire, which I would like to repress but cannot, to annoy her. Her youth, the calm weather ought surely to coax her to sleep. No? Why not? I feel a strong inclination to force her to tell me that she lies awake because she is afraid that he… Indeed? And then: “No, no, sleep sound, everything is going well, going perfectly. You should see the energy with which he has set to work to interpret his part in the tiger film! And he does it really well, because as a boy he used to say that if his grandfather had allowed it, he would have gone upon the stage; and he would not have been wrong! A marvellous natural aptitude; a true thoroughbred distinction; the perfect composure of an

English gentleman following the perfidious ‘Miss’ on her travels in the East! And you ought to see the courteous submission with which he accepts advice from the professional actors, from the producers Bertini and Polacco, and how delighted he is with their praise! So there is nothing to be afraid of, Signorina. He is perfectly calm….” “How do you account for that?” “Why, in this way, perhaps, that having never done anything, lucky fellow, in his life, now that, by force of circumstances, he has set himself to do something, and the very thing that at one time he would have liked to do, he has taken a fancy to it, finds distraction in it, flatters his vanity with it.”

No! Signorina Luisetta says no, persists in repeating no, no, no; that it does not seem to her possible; that she cannot believe it; that he must be brooding over some act of violence, which he is keeping dark.

Nothing could be easier, when a suspicion of this sort has taken root, than to find a corroborating significance in every trifling action. And Signorina Luisetta finds so many! And she comes and tells me about them every morning in my room: “He is writing,” “He is frowning,” “He never looked up,” “He forgot to say good morning….”

“Yes, Signorina, and what about this; he blew his nose with his left hand this morning, instead of using his right!”

Signorina Luisetta does not laugh: she looks at me, frowning, to see whether I am serious: then goes away in a dudgeon and sends to my room Cavalena, her father, who (I can see) is doing everything in his power, poor man, to overcome in my presence the consternation which his daughter has succeeded in conveying to him in its strongest form, trying to rise to abstract considerations.

“Women!” he begins, throwing out his hands. “You, fortunately for yourself (and may it always remain so, I wish with, all my heart, Signor Gubbio!) have never encountered the Enemy upon your path. But look at me! What fools the men are who, when they hear woman called’the enemy,’ at once retort: ‘But what about your mother? Your sisters? Your daughters?’ as though to a man, who in that case is a son, a brother, a father, those were women! Women, indeed! One’s mother? You have to consider your mother in relation to your father, and your sisters or daughters in relation to their husbands; then the true woman, the enemy will emerge! Is there anything dearer to me than my poor darling child? Yet I have not the slightest hesitation in admitting, Signor Gubbio, that even she, undoubtedly, even my Sesè is capable of becoming, like all other women when face to face with man, the enemy. And there is no goodness of heart, there is no submissiveness that can restrain them, believe me! When, at a turn in the road, you meet her, the particular woman, to whom I refer, the enemy: then one of two things must happen: either you kill her, or you have to submit, as I have done. But how many men are capable of submitting as I have done? Grant me at least the meagre satisfaction of saying very few, Signor Gubbio, very few!”

I reply that I entirely agree with him.

Whereupon: “You agree?” asks Cavalena, with a surprise which he makes haste to conceal, fearing lest from his surprise I may divine his purpose. “You agree?”

And he looks me timidly in the face, as though seeking the right moment to descend, without marring our agreement, from the abstract consideration to the concrete instance. But here I quickly stop him.

“Good Lord, but why,” I ask him, “must you believe in such a desperate resolution on Signora Nestoroff’s part to be Signor Nuti’s enemy!”

“What’s that? But surely? Don’t you think so? But she is! She is the enemy!” exclaims Cavalena. “That seems to me to be unquestionable!”

“And why?” I persisted. “What seems to me unquestionable is that she has no desire to be his friend or his enemy or anything at all.”