Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 909

Alle waarheden, – konsekwente gevolgen slechts van ‘t voorafgaande – zyn even eenvoudig, en zy die aan ‘n persoonlyken God gelooven, durven slechts dan z’n tusschenkomst inroepen, als de reeks der syllogismen waaruit het gehoopte of gevreesde moet voortvloeien, door meerder uitgebreidheid hun waarnemingsvermogen te-boven gaat. (167) Er wordt gebeden om regen, omdat we geen kontrole hebben over de massa damp waaruit ze geleverd wordt, maar niemand zal ooit durven aandringen op vermeerdering van ‘t hem bekend aantal muntstukken in z’n porte-monnaie. ‘t Heeft er veel van, of men meent dat God genegen is wonderen te doen – d.i. afwyking te gelasten van den aard der dingen – mits men hem nooit kunne bewyzen dat de verleende hulp in-stryd was met gezond verstand. Men mag dus aannemen dat-i zich voor z’n wonderen schaamt. Het is dan ook zeker hierom dat er wel gebeden wordt om ‘t herstel van ‘n kranke, maar aan ‘n verzoek om opwekking uit den dood, waagt zich de hardnekkigste bidder niet.

Daar nu overigens – altyd onder de voorwaarde dat het verlangde kan worden voorgesteld als iets natuurlyks – ‘t vertrouwen op Gods tusschenkomst aangroeit naarmate de zaak waartoe die wordt ingeroepen, ingewikkelder schynt, volgt hieruit vanzelf dat dit vertrouwen in omgekeerde verhouding staat tot onze kennis en ontwikkeling. Hoe minder wetenschap alzoo, hoe meer geloof. Men meene echter niet dat alleen eigenlyk-gezegde wetenschap de tegenvoetster is van goddienery. Oordeel, vlyt, moed, karakter, al wat den mensch tot mensch maakt…

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

The Sonnets

26

Lord of my love, to whom in vassalage

Thy merit hath my duty strongly knit;

To thee I send this written embassage

To witness duty, not to show my wit.

Duty so great, which wit so poor as mine

May make seem bare, in wanting words to show it;

But that I hope some good conceit of thine

In thy soul’s thought (all naked) will bestow it:

Till whatsoever star that guides my moving,

Points on me graciously with fair aspect,

And puts apparel on my tattered loving,

To show me worthy of thy sweet respect,

Then may I dare to boast how I do love thee,

Till then, not show my head where thou mayst prove me.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

.jpg)

Novalis

(Friedrich von Hardenberg, 1772–1802)

Hymnen an die Nacht 3

Einst da ich bittre Thränen vergoß, da in Schmerz aufgelöst meine Hoffnung zerrann, und ich einsam stand am dürren Hügel, der in engen, dunkeln Raum die Gestalt meines Lebens barg – einsam, wie noch kein Einsamer war, von unsäglicher Angst getrieben – kraftlos, nur ein Gedanken des Elends noch. – Wie ich da nach Hülfe umherschaute, vorwärts nicht konnte und rückwärts nicht, und am fliehenden, verlöschten Leben mit unendlicher Sehnsucht hing: – da kam aus blauen Fernen – von den Höhen meiner alten Seligkeit ein Dämmerungsschauer – und mit einemmale riß das Band der Geburt – des Lichtes Fessel. Hin floh die irdische Herrlichkeit und meine Trauer mit ihr – zusammen floß die Wehmuth in eine neue, unergründliche Welt – du Nachtbegeisterung, Schlummer des Himmels kamst über mich – die Gegend hob sich sacht empor; über der Gegend schwebte mein entbundner, neugeborner Geist. Zur Staubwolke wurde der Hügel – durch die Wolke sah ich die verklärten Züge der Geliebten. In ihren Augen ruhte die Ewigkeit – ich faßte ihre Hände, und die Thränen wurden ein funkelndes, unzerreißliches Band. Jahrtausende zogen abwärts in die Ferne, wie Ungewitter. An Ihrem Halse weint ich dem neuen Leben entzückende Thränen. – Es war der erste, einzige Traum – und erst seitdem fühl ich ewigen, unwandelbaren Glauben an den Himmel der Nacht und sein Licht, die Geliebte.

.jpg)

Novalis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

A u g u s t S t r a m m

(1874-1915)

Dämmerung

Hell weckt Dunkel

Dunkel wehrt Schein

Der Raum zersprengt die Räume

Fetzen ertrinken in Einsamkeit!

Die Seele tanzt

Und

Schwingt und schwingt

Und

Bebt im Raum

Du!

Meine Glieder suchen sich

Meine Glieder kosen sich

Meine Glieder

Schwingen sinken sinken ertrinken

In

Unermeßlichkeit

Du!

Hell wehrt Dunkel

Dunkel frißt Schein!

Der Raum ertrinkt in Einsamkeit

Die Seele

Strudelt

Sträubet

Halt!

Meine Glieder

Wirbeln

In

Unermeßlichkeit

Du!

Hell ist Schein!

Einsamkeit schlürft!

Unermeßlichkeit strömt

Zerreißt

Mich

In

Du!

Du!

August Stramm poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Expressionism, Stramm, August

.jpg)

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

The Masque of the Red Death

The red death had long devastated the country. No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its seal–the madness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution. The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim, were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow-men. And the whole seizure, progress, and termination of the disease, were incidents of half an hour.

But Prince Prospero was happy and dauntless and sagacious. When his dominions were half depopulated, he summoned to his presence a thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court, and with these retired to the deep seclusion of one of his crenellated abbeys. This was an extensive and magnificent structure, the creation of the prince’s own eccentric yet august taste. A strong and lofty wall girdled it in. This wall had gates of iron. The courtiers, having entered, brought furnaces and massy hammers and welded the bolts.

They resolved to leave means neither of ingress nor egress to the sudden impulses of despair or of frenzy from within. The abbey was amply provisioned. With such precautions the courtiers might bid defiance to contagion. The external world could take care of itself. In the meantime it was folly to grieve or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure. There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballet-dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine. All these and security were within. Without was the “Red Death.”

It was toward the close of the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion that the Prince Prospero entertained his thousand friends at a masked ball of the most unusual magnificence.

It was a voluptuous scene, that masquerade. But first let me tell of the rooms in which it was held. There were seven–an imperial suite, In many palaces, however, such suites form a long and straight vista, while the folding doors slide back nearly to the walls on either hand, so that the view of the whole extant is scarcely impeded. Here the case was very different; as might have been expected from the duke’s love of the “bizarre.” The apartments were so irregularly disposed that the vision embraced but little more than one at a time. There was a sharp turn at the right and left, in the middle of each wall, a tall and narrow Gothic window looked out upon a closed corridor of which pursued the windings of the suite. These windows were of stained glass whose color varied in accordance with the prevailing hue of the decorations of the chamber into which it opened. That at the eastern extremity was hung, for example, in blue–and vividly blue were its windows. The second chamber was purple in its ornaments and tapestries, and here the panes were purple. The third was green throughout, and so were the casements. The fourth was furnished and lighted with orange–the fifth with white–the sixth with violet. The seventh apartment was closely shrouded in black velvet tapestries that hung all over the ceiling and down the walls, falling in heavy folds upon a carpet of the same material and hue. But in this chamber only, the color of the windows failed to correspond with the decorations. The panes were scarlet–a deep blood color. Now in no one of any of the seven apartments was there any lamp or candelabrum, amid the profusion of golden ornaments that lay scattered to and fro and depended from the roof. There was no light of any kind emanating from lamp or candle within the suite of chambers. But in the corridors that followed the suite, there stood, opposite each window, a heavy tripod, bearing a brazier of fire, that projected its rays through the tinted glass and so glaringly lit the room. And thus were produced a multitude of gaudy and fantastic appearances. But in the western or back chamber the effect of the fire-light that streamed upon the dark hangings through the blood-tinted panes was ghastly in the extreme, and produced so wild a look upon the countenances of those who entered, that there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all. It was within this apartment, also, that there stood against the western wall, a gigantic clock of ebony. It pendulum swung to and fro with a dull, heavy, monotonous clang; and when the minute-hand made the circuit of the face, and the hour was to be stricken, there came from the brazen lungs of the clock a sound which was clear and loud and deep and exceedingly musical, but of so peculiar a note and emphasis that, at each lapse of an hour, the musicians of the orchestra were constrained to pause, momentarily, in their performance, to hearken to the sound; and thus the waltzers perforce ceased their evolutions; and there was a brief disconcert of the whole gay company; and while the chimes of the clock yet rang. it was observed that the giddiest grew pale, and the more aged and sedate passed their hands over their brows as if in confused revery or meditation. But when the echoes had fully ceased, a light laughter at once pervaded the assembly; the musicians looked at each other and smiled as if at their own nervousness and folly, and made whispering vows, each to the other, that the next chiming of the clock should produce in them no similar emotion; and then, after the lapse of sixty minutes (which embrace three thousand and six hundred seconds of Time that flies), there came yet another chiming of the clock, and then were the same disconcert and tremulousness and meditation as before. But, in spite of these things, it was a gay and magnificent revel. The tastes of the duke were peculiar. He had a fine eye for color and effects. He disregarded the “decora” of mere fashion. His plans were bold and fiery, and his conceptions glowed with barbaric lustre. There are some who would have thought him mad. His followers felt that he was not. It was necessary to hear and see and touch him to be sure he was not.

He had directed, in great part, the movable embellishments of the seven chambers, upon occasion of this great fete; and it was his own guiding taste which had given character to the masqueraders. Be sure they were grotesque. There were much glare and glitter and piquancy and phantasm–much of what has been seen in “Hernani.” There were arabesque figures with unsuited limbs and appointments. There were delirious fancies such as the madman fashions. There were much of the beautiful, much of the wanton, much of the bizarre, something of the terrible, and not a little of that which might have excited disgust. To and fro in the seven chambers stalked, in fact, a multitude of dreams. And these the dreams–writhed in and about, taking hue from the rooms, and causing the wild music of the orchestra to seem as the echo of their steps. And, anon, there strikes the ebony clock which stands in the hall of the velvet. And then, for a moment, all is still, and all is silent save the voice of the clock. The dreams are stiff-frozen as they stand. But the echoes of the chime die away–they have endured but an instant–and a light half-subdued laughter floats after them as they depart. And now the music swells, and the dreams live, and writhe to and fro more merrily than ever, taking hue from the many-tinted windows through which stream the rays of the tripods. But to the chamber which lies most westwardly of the seven there are now none of the maskers who venture, for the night is waning away; and there flows a ruddier light through the blood-colored panes; and the blackness of the sable drapery appalls; and to him whose foot falls on the sable carpet, there comes from the near clock of ebony a muffled peal more solemnly emphatic than any which reaches their ears who indulge in the more remote gaieties of the other apartments.

But these other apartments were densely crowded, and in them beat feverishly the heart of life. And the revel went whirlingly on, until at length there commenced the sounding of midnight upon the clock. And then the music ceased, as I have told; and the evolutions of the waltzers were quieted; and there was an uneasy cessation of all things as before. But now there were twelve strokes to be sounded by the bell of the clock; and thus it happened, perhaps that more of thought crept, with more of time into the meditations of the thoughtful among those who revelled. And thus too, it happened, that before the last echoes of the last chime had utterly sunk into silence, there were many individuals in the crowd who had found leisure to become aware of the presence of a masked figure which had arrested the attention of no single individual before. And the rumor of this new presence having spread itself whisperingly around, there arose at length from the whole company a buzz, or murmur, of horror, and of disgust.

In an assembly of phantasms such as I have painted, it may well be supposed that no ordinary appearance could have excited such sensation. In truth the masquerade license of the night was nearly unlimited; but the figure in question had out-Heroded Herod, and gone beyond the bounds of even the prince’s indefinite decorum. There are chords in the hearts of the most reckless which cannot be touched without emotion. Even with the utterly lost, to whom life and death are equally jests, there are matters of which no jest can be made. The whole company, indeed, seemed now deeply to feel that in the costume and bearing of the stranger neither wit nor propriety existed. The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the habiliments of the grave. The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have difficulty in detecting the cheat. And yet all this might have been endured, if not approved, by the mad revellers around. But the mummer had gone so far as to assume the type of the Red Death. His vesture was dabbled in blood–and his broad brow, with all the features of his face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.

When the eyes of Prince Prospero fell on this spectral image (which, with a slow and solemn movement, as if more fully to sustain its role, stalked to and fro among the waltzers) he was seen to be convulsed, in the first moment with a strong shudder either of terror or distaste; but in the next, his brow reddened with rage.

“Who dares”–he demanded hoarsely of the courtiers who stood near him–“who dares insult us with this blasphemous mockery? Seize him and unmask him–that we may know whom we have to hang, at sunrise, from the battlements!”

It was in the eastern or blue chamber in which stood Prince Prospero as he uttered these words. They rang throughout the seven rooms loudly and clearly, for the prince was a bold and robust man, and the music had become hushed at the waving of his hand.

It was in the blue room where stood the prince, with a group of pale courtiers by his side. At first, as he spoke, there was a slight rushing movement of this group in the direction of the intruder, who, at the moment was also near at hand, and now, with deliberate and stately step, made closer approach to the speaker. But from a certain nameless awe with which the mad assumptions of the mummer had inspired the whole party, there were found none who put forth a hand to seize him; so that, unimpeded, he passed within a yard of the prince’s person; and while the vast assembly, as with one impulse, shrank from the centers of the rooms to the walls, he made his way uninterruptedly, but with the same solemn and measured step which had distinguished him from the first, through the blue chamber to the purple–to the purple to the green–through the green to the orange–through this again to the white–and even thence to the violet, ere a decided movement had been made to arrest him. It was then, however, that the Prince Prospero, maddened with rage and the shame of his own momentary cowardice, rushed hurriedly through the six chambers, while none followed him on account of a deadly terror that had seized upon all. He bore aloft a drawn dagger, and had approached, in rapid impetuosity, to within three or four feet of the retreating figure, when the latter, having attained the extremity of the velvet apartment, turned suddenly and confronted his pursuer. There was a sharp cry–and the dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet, upon which most instantly afterward, fell prostrate in death the Prince Prospero. Then summoning the wild courage of despair, a throng of the revellers at once threw themselves into the black apartment, and seizing the mummer whose tall figure stood erect and motionless within the shadow of the ebony clock, gasped in unutterable horror at finding the grave cerements and corpse-like mask, which they handled with so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form.

And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.

Edgar Allan Poe: The Masque of the Red Death

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

.jpg)

.jpg)

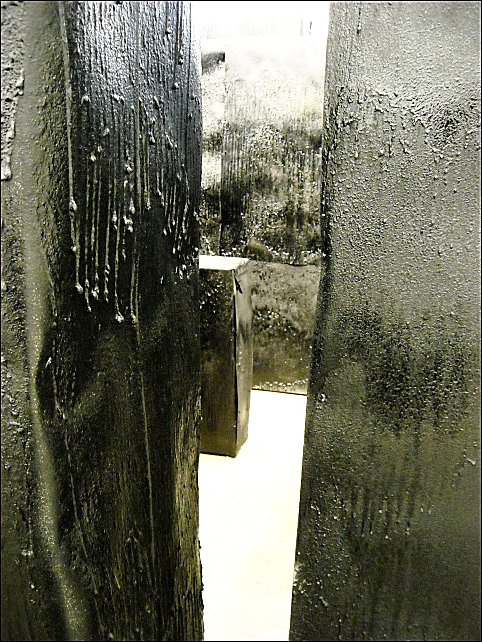

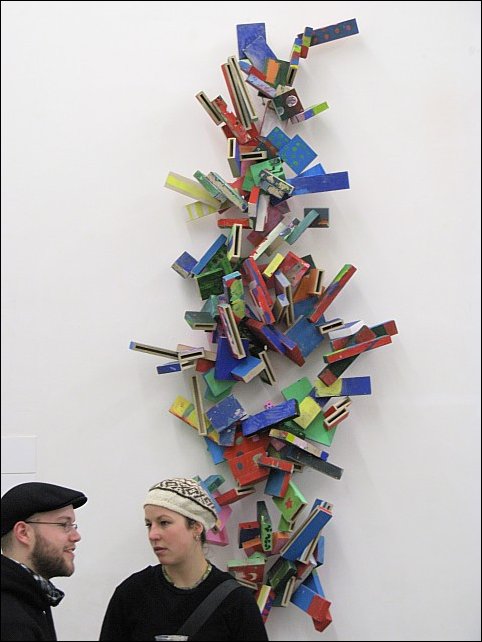

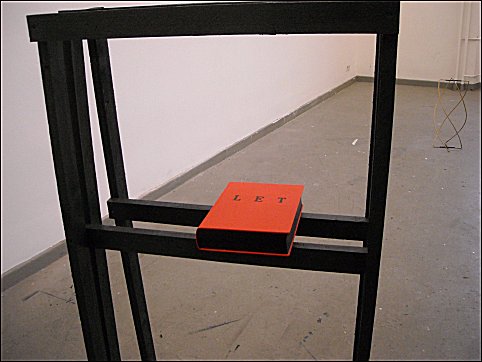

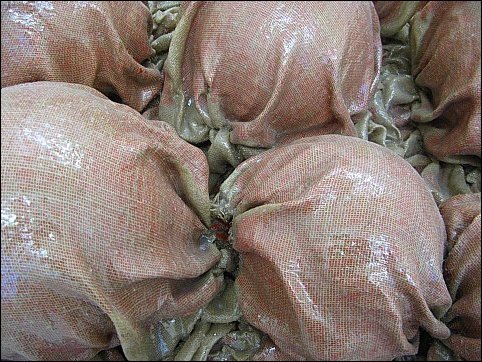

Kunstakademie Düsseldorf

Rundgang 2010 – Teil 3

Photos Anton & Joseph K.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

(to be continued)

More in: FDM Art Gallery, Galerie Deutschland

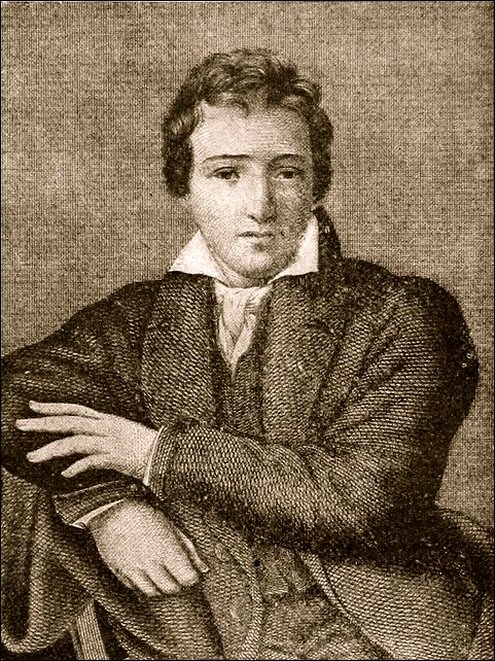

Heinrich Heine

(1797-1856)

T r a u m b i l d e r

I

Mir traeumte einst von wildem Liebesgluehn,

Von huebschen Locken, Myrten und Resede,

Von suessen Lippen und von bittrer Rede,

Von duestrer Lieder duestern Melodien.

Verblichen und verweht sind laengst die Traeume,

Verweht ist gar mein liebstes Traumgebild!

Geblieben ist mir nur, was glutenwild

Ich einst gegossen hab in weiche Reime.

Du bliebst, verwaistes Lied! Verweh jetzt auch,

Und such das Traumbild, das mir laengst entschwunden,

Und gruess es mir, wenn du es aufgefunden —

Dem luftgen Schatten send ich luftgen Hauch.

II

Ein Traum, gar seltsam schauerlich,

Ergoetzte und erschreckte mich.

Noch schwebt mir vor mach grausig Bild,

Und in dem Herzen wogt es wild.

Das war ein Garten, wunderschoen,

Da wollte ich lustig mich ergehn;

Viel schoene Blumen sahn mich an,

Ich hatte meine Freude dran.

Es zwitscherten die Voegelein

Viel muntre Liebesmelodein;

Die Sonne rot, von Gold umstrahlt,

Die Blumen lustig bunt bemalt.

Viel Balsamduft aus Kraeutern rinnt,

Die Luefte wehen lieb und lind;

Und alles schimmert, alles lacht,

Und zeigt mir freundlich seine Pracht.

Inmitten in dem Blumenland

Ein klarer Marmorbrunnen stand;

Da schaut ich eine schoene Maid,

Die emsig wusch ein weisses Kleid.

Die Waenglein suess, die AEuglein mild,

Ein blondgelocktes Heilgenbild;

Und wie ich schau, die Maid ich fand

So fremd und doch so wohlbekannt.

Die schoene Maid, die sputet sich,

Sie summt ein Lied gar wunderlich;

"Rinne, rinne, Waesserlein,

Wasche mir das Linnen rein."

Ich ging und nahete mich ihr,

Und fluesterte: O sage mir,

Du wunderschoene, suesse Maid,

Fuer wen ist dieses weisse Kleid?

Da sprach sie schnell: "Sei bald bereit,

Ich wasche dir dein Totenkleid!"

Und als sie dies gesprochen kaum,

Zerfloss das ganze Bild, wie Schaum. —

Und fortgezaubert stand ich bald

In einem duestern, wilden Wald.

Die Baeume ragten himmelan;

Ich stand erstaunt und sann und sann.

Und horch! Welch dumpfer Widerhall!

Wie ferner AExtenschlaege Schall;

Ich eil durch Busch und Wildnis fort,

Und komm an einen freien Ort.

Inmitten in dem gruenen Raum,

Da stand ein grosser Eichenbaum;

Und sieh! mein Maegdlein wundersam

Haut mit dem Beil den Eichenstamm.

Und Schlag auf Schlag, und sonder Weil,

Summt sie ein Lied und schwingt das Beil:

"Eisen blink, Eisen blank,

Zimmre hurtig Eichenschrank."

Ich ging und nahete mich ihr,

Und fluesterte: O sage mir,

Du wundersuesses Maegdelein,

Wem zimmerst du den Eichenschrein?

Da sprach sie schnell: "Die Zeit ist karg,

Ich zimmre deinen Totensarg!"

Und als sie dies gesprochen kaum,

Zerfloss das ganze Bild, wie Schaum. —

Es lag so bleich, es lag so weit

Ringsum nur kahle, kahle Heid;

Ich wusste nicht, wie mir geschah,

Und heimlich schaudernd stand ich da.

Und nun ich eben fuerder schweif,

Gewahr ich einen weissen Streif;

Ich eilt drauf zu, und eilt und stand,

Und sieh! die schoene Maid ich fand.

Auf weiter Heid stand weisse Maid,

Grub tief die Erd mit Grabescheit.

Kaum wagt ich noch sie anzuschaun,

Sie war so schoen und doch ein Graun.

Die schoene Maid, die sputet sich,

Sie summt ein Lied gar wunderlich:

"Spaten, Spaten, scharf und breit,

Schaufle Grube tief und weit."

Ich ging und nahete mich ihr,

Und fluesterte: O sage mir,

Du wunderschoene, suesse Maid,

Was diese Grube hier bedeut’t?

Da sprach sie schnell: "Sei still, ich hab

Geschaufelt dir ein kuehles Grab."

Und als so sprach die schoene Maid,

Da oeffnet sich die Grube weit;

Und als ich in die Grube schaut,

Ein kalter Schauer mich durchgraut;

Und in die dunkle Grabesnacht

Stuerzt ich hinein — und bin erwacht.

III

Im naechtgen Traum hab ich mich selbst geschaut,

In schwarzem Galafrack und seidner Weste,

Manschetten an der Hand, als ging’s zum Feste,

Und vor mir stand mein Liebchen, suess und traut.

Ich beugte mich und sagte: "Sind Sie Braut?

Ei! ei! so gratulier ich, meine Beste!"

Doch fast die Kehle mir zusammenpresste

Der langgezogne, vornehm kalte Laut.

Und bittre Traenen ploetzlich sich ergossen

Aus Liebchens Augen, und in Traenenwogen

Ist mir das holde Bildnis fast zerflossen.

O suesse Augen, fromme Liebessterne,

Obschon ihr mir im Wachen oft gelogen,

Und auch im Traum, glaub ich euch dennoch gerne.

IV

Im Traum sah ich ein Maennchen klein und putzig,

Das ging auf Stelzen, Schritte ellenweit,

Trug weisse Waesche und ein feines Kleid,

Inwendig aber war es grob und schmutzig.

Inwendig war es jaemmerlich, nichtsnutzig,

Jedoch von aussen voller Wuerdigkeit;

Von der Courage sprach es lang und breit,

Und tat sogar recht trutzig und recht stutzig.

"Und weisst Du, wer das ist, Komm her und schau!"

So sprach der Traumgott, und er zeigt’ mir schlau

Die Bilderflut in eines Spiegels Rahmen.

Vor einem Altar stand das Maennchen da,

Mein Lieb daneben, beide sprachen: Ja!

Und tausend Teufel riefen lachend: Amen!

V

Was treibt und tobt mein tolles Blut?

Was flammt mein Herz in wilder Glut?

Es kocht mein Blut und schaeumt und gaert,

Und grimme Wut mein Herz verzehrt.

Das Blut ist toll, und gaert und schaeumt,

Weil ich den boesen Traum getraeumt;

Es kam der finstre Sohn der Nacht,

Und hat mich keuchend fortgebracht.

Er bracht mich in ein helles Haus,

Wo Harfenklang und Saus und Braus

Und Fackelglanz und Kerzenschein;

Ich kam zum Saal, ich trat hinein.

Das war ein lustig Hochzeitfest;

Zu Tafel sassen froh die Gaest.

Und wie ich nach dem Brautpaar schaut —

O weh! mein Liebchen war die Braut.

Das war mein Liebchen wunnesam,

Ein fremder Mann war Braeutigam;

Dicht hinterm Ehrenstuhl der Braut,

Da blieb ich stehn, gab keinen Laut.

Es rauscht Musik — gar still stand ich;

Der Freudenlaerm betruebte mich.

Die Braut, sie blickt so hochbeglueckt,

Der Braeutigam ihre Haende drueckt.

Der Braeutigam fuellt den Becher sein,

Und trinkt daraus, und reicht gar fein

Der Braut ihn hin; sie laechelt Dank —

O weh! mein rotes Blut sie trank.

Die Braut ein huebsches AEpflein nahm,

Und reicht es hin dem Braeutigam.

Der nahm sein Messer, schnitt hinein —

O weh! das war das Herze mein.

Sie aeugeln suess, sie aeugeln lang,

Der Braeutigam kuehn die Braut umschlang,

Und kuesst sie auf die Wangen rot —

O weh! mich kuesst der kalte Tod.

Wie Blei lag meine Zung im Mund,

Dass ich kein Woertlein sprechen kunt.

Da rauscht es auf, der Tanz begann;

Das schmucke Brautpaar tanzt voran.

Und wie ich stand so leichenstumm,

Die Taenzer schweben flink herum; —

Ein leises Wort der Braeutigam spricht,

Die Braut wird rot, doch zuernt sie nicht. —

VI

Im suessen Traum, bei stiller Nacht

Da kam zu mir, mit Zaubermacht,

Mit Zaubermacht, die Liebste mein,

Sie kam zu mir ins Kaemmerlein.

Ich schau sie an, das holde Bild!

Ich schau sie an, sie laechelt mild,

Und laechelt, bis das Herz mir schwoll,

Und stuermisch kuehn das Wort entquoll:

"Nimm hin, nimm alles was ich hab,

Mein Liebstes tret ich gern dir ab,

Duerft ich dafuer dein Buhle sein,

Von Mitternacht bis Hahnenschrein."

Da staunt’ mich an gar seltsamlich,

So lieb, so weh und inniglich,

Und sprach zu mir die schoene Maid:

O, gib mir deine Seligkeit!

"Mein Leben suess, mein junges Blut,

Gaeb ich, mit Freud und wohlgemut,

Fuer dich, o Maedchen engelgleich —

Doch nimmermehr das Himmelreich."

Wohl braust hervor mein rasches Wort,

Doch bluehet schoener immerfort,

Und immer spricht die schoene Maid:

O, gib mir deine Seligkeit!

Dumpf droehnt dies Wort mir ins Gehoer

Und schleudert mir ein Glutenmeer

Wohl in der Seele tiefsten Raum;

Ich atme schwer, ich atme kaum. —

Das waren weisse Engelein,

Umglaenzt von goldnem Glorienschein;

Nun aber stuermte wild herauf

Ein greulich schwarzer Koboldhauf.

Die rangen mit den Engelein,

Und draengten fort die Engelein;

Und endlich auch die schwarze Schar

In Nebelduft zerronnen war. —

Ich aber wollt in Lust vergehn,

Ich hielt im Arm mein Liebchen schoen;

Sie schmiegt sich an mich wie ein Reh,

Doch weint sie auch mit bitterm Weh.

Feins Liebchen weint; ich weiss warum,

Und kuesst ihr Rosenmuendlein stumm. —

"O still feins Lieb, die Traenenflut,

Ergib dich meiner Liebesglut!"

"Ergib dich meiner Liebesglut –"

Da ploetzlich starrt zu Eis mein Blut;

Laut bebet auf der Erde Grund,

Und oeffnet gaehnend sich ein Schlund.

Und aus dem schwarzen Schlunde steigt

Die schwarze Schar; — feins Lieb erbleicht!

Aus meinen Armen schwand feins Lieb;

Ich ganz alleine stehen blieb.

Da tanzt im Kreise wunderbar,

Um mich herum, die schwarze Schar,

Und draengt heran, erfasst mich bald,

Und gellend Hohngelaechter schallt.

Und immer enger wird der Kreis,

Und immer summt die Schauerweis:

Du gabest hin die Seligkeit,

Gehoerst uns nun in Ewigkeit!

VII

Nun hast du das Kaufgeld, nun zoegerst du doch?

Blutfinstrer Gesell, was zoegerst du noch?

Schon sitze ich harrend im Kaemmerlein traut,

Und Mitternacht naht schon — es fehlt nur die Braut.

Viel schauernde Lueftchen vom Kirchhofe wehn; —

Ihr Lueftchen! habt ihr mein Braeutchen gesehn?

Viel blasse Larven gestalten sich da,

Umknicksen mich grinsend und nicken: O ja!

Pack aus, was bringst du fuer Botschafterei,

Du schwarzer Schlingel in Feuerlivrei?

"Die gnaedige Herrschaft meldet sich an,

Gleich kommt sie gefahren im Drachengespann."

Du lieb grau Maennchen, was ist dein Begehr?

Mein toter Magister, was treibt dich her?

Er schaut mich mit schweigend truebseligem Blick,

Und schuettelt das Haupt, und wandelt zurueck.

Was winselt und wedelt der zottge Gesell?

Was glimmert schwarz Katers Auge so hell?

Was heulen die Weiber mit fliegendem Haar?

Was lullt mir Frau Amme mein Wiegenlied gar?

Frau Amme, bleib heut mit dem Singsang zu Haus,

Das Eiapopeia ist lange schon aus;

Ich feire ja heute mein Hochzeitsfest —

Da schau mal, dort kommen schon zierliche Gaest.

Da schau mal! Ihr Herren, das nenn ich galant!

Ihr tragt, statt der Huete, die Koepf in der Hand!

Ihr Zappelbeinleutchen im Galgenornat,

Der Wind ist still, was kommt ihr so spat?

Da kommt auch alt Besenstielmuetterchen schon.

Ach segne mich, Muetterchen, bin ja dein Sohn.

Da zittert der Mund im weissen Gesicht:

"In Ewigkeit Amen!" das Muetterchen spricht.

Zwoelf windduerre Musiker schlendern herein;

Blind Fiedelweib holpert wohl hintendrein.

Da schleppt der Hanswurst, in buntscheckiger Jack,

Den Totengraeber huckepack.

Es tanzen zwoelf Klosterjungfrauen herein;

Die schielende Kupplerin fuehret den Reihn.

Es folgen zwoelf luesterne Pfaeffelein schon,

Und pfeifen ein Schandlied im Kirchenton.

Herr Troedler, o schrei dir nicht blau das Gesicht,

Im Fegfeuer nuetzt mir dein Pelzroeckel nicht;

Dort heizet man gratis jahraus, jahrein,

Statt mit Holz, mit Fuersten– und Bettlergebein.

Die Blumenmaedchen sind bucklicht und krumm,

Und purzeln kopfueber im Zimmer herum.

Ihr Eulengesichter mit Heuschreckenbein,

Hei! lasst mir das Rippengeklapper nur sein!

Die saemtliche Hoell ist los fuerwahr,

Und laermet und schwaermet in wachsender Schar.

Sogar der Verdammniswalzer erschallt —

Still, still! nun kommt mein feins Liebchen auch bald.

Gesindel, sei still, oder trolle dich fort!

Ich hoere kaum selber mein leibliches Wort —

Ei, rasselt nicht eben ein Wagen vor?

Frau Koechin! wo bist du? Schnell oeffne das Tor!

Willkommen, feins Liebchen, wie geht’s dir, mein Schatz?

Willkommen, Herr Pastor, ach nehmen Sie Platz!

Herr Pastor mit Pferdefuss und Schwanz,

Ich bin Eur Ehrwuerden Diensteigener ganz!

Lieb Braeutchen, was stehst du so stumm und bleich?

Der Herr Pastor schreitet zur Trauung sogleich;

Wohl zahl ich ihm teure, blutteure Gebuehr,

Doch dich zu besitzen gilts Kinderspiel mir.

Knie nieder, suess Braeutchen, knie hin mir zur Seit! —

Da kniet sie, da sinkt sie — o selige Freud! —

Sie sinkt mir ans Herz, an die schwellende Brust,

Ich halt sie umschlungen mit schauernder Lust.

Die Goldlockenwellen umspielen uns beid:

An mein Herze pocht das Herze der Maid.

Sie pochen wohl beide vor Lust und vor Weh,

Und schweben hinauf in die Himmelshoeh.

Die Herzlein schwimmen im Freudensee,

Dort oben in Gottes heilger Hoeh;

Doch auf den Haeuptern, wie Grausen und Brand,

Da hat die Hoelle gelegt die Hand.

Das ist der finstre Sohn der Nacht,

Der hier den segnenden Priester macht;

Er murmelt die Formel aus blutigem Buch,

Sein Beten ist Laestern, sein Segnen ist Fluch.

Und es kraechzet und zischet und heulet toll,

Wie Wogengebrause, wie Donnergroll; —

Da blitzet auf einmal ein blaeuliches Licht —

"In Ewigkeit Amen!" das Muetterchen spricht.

VIII

Ich kam von meiner Herrin Haus

Und wandelt in Wahnsinn und Mitternachtgraus.

Und wie ich am Kirchhof voruebergehn will,

Da winken die Graeber ernst und still.

Da winkts von des Spielmanns Leichenstein;

Das war der flimmernde Mondesschein.

Da lispelts: Lieb Bruder, ich komme gleich!

Da steigts aus dem Grabe nebelbleich.

Der Spielmann war’s, der entstiegen jetzt,

Und hoch auf den Leichenstein sich setzt.

In die Saiten der Zither greift er schnell,

Und singt dabei recht hohl und grell:

Ei! kennt ihr noch das alte Lied,

Das einst so wild die Brust durchglueht,

Ihr Saiten dumpf und truebe?

Die Engel, die nennen es Himmelsfreud,

Die Teufel, die nennen es Hoellenleid,

Die Menschen, die nennen es: Liebe!

Kaum toente des letzten Wortes Schall,

Da taten sich auf die Graeber all;

Viel Luftgestalten dringen hervor,

Umschweben den Spielmann und schrillen im Chor:

Liebe! Liebe! deine Macht

Hat uns hier zu Bett gebracht

Und die Augen zugemacht —

Ei, was rufst du in der Nacht?

So heult es verworren, und aechzet und girrt,

Und brauset und sauset, und kraechzet und klirrt;

Und der tolle Schwarm den Spielmann umschweift,

Und der Spielmann wild in die Saiten greift:

Bravo! bravo! immer toll!

Seid willkommen!

Habt vernommen,

Dass mein Zauberwort erscholl!

Liegt man doch jahraus, jahrein

Maeuschenstill im Kaemmerlein;

Lasst uns heute lustig sein!

Mit Vergunst —

Seht erst zu, sind wir allein? —

Narren waren wir im Leben

Und mit toller Wut ergeben

Einer tollen Liebesbrunst.

Kurzweil kann uns heut nicht fehlen,

Jeder soll hier treu erzaehlen,

Was ihn weiland hergebracht,

Wie gehetzt,

Wie zerfetzt

Ihn die tolle Liebesjagd.

Da huepft aus dem Kreise, so leicht wie der Wind,

Ein mageres Wesen, das summend beginnt:

Ich war ein Schneidergeselle

Mit Nadel und mit Scher;

Ich war so flink und schnelle

Mit Nadel und mit Scher;

Da kam die Meisterstochter

Mit Nadel und mit Scher;

Und hat mir ins Herz gestochen

Mit Nadel und mit Scher.

Da lachten die Geister im lustigen Chor;

Ein Zweiter trat still und ernst hervor:

Den Rinaldo Rinaldini,

Schinderhanno, Orlandini,

Und besonders Carlo Moor

Nahm ich mir als Muster vor.

Auch verliebt — mit Ehr zu melden —

Hab ich mich, wie jene Helden,

Und das schoenste Frauenbild

Spukte mir im Kopfe wild.

Und ich seufzte auch und girrte;

Und wenn Liebe mich verwirrte,

Stecht ich meine Finger rasch

In des Herren Nachbars Tasch.

Doch der Gassenvogt mir grollte,

Dass ich Sehnsuchtstraenen wollte

Trocknen mit dem Taschentuch,

Das mein Nachbar bei sich trug.

Und nach frommer Haeschersitte

Nahm man still mich in die Mitte,

Und das Zuchthaus, heilig gross,

Schloss mir auf den Mutterschoss.

Schwelgend suess in Liebessinnen,

Sass ich dort beim Wollespinnen,

Bis Rinaldos Schatten kam

Und die Seele mit sich nahm.

Da lachten die Geister im lustigen Chor;

Geschminkt und geputzt trat ein Dritter hervor:

Ich war ein Koenig der Bretter

Und spielte das Liebhaberfach,

Ich bruellte manch wildes: Ihr Goetter!

Ich seufzte manch zaertliches: Ach!

Den Mortimer spielt ich am besten,

Maria war immer so schoen!

Doch trotz der natuerlichsten Gesten,

Sie wollte mich nimmer verstehn. —

Einst, als ich verzweifelnd am Ende:

"Maria, du Heilige!" rief,

Da nahm ich den Dolch behende —

Und stach mich in bisschen zu tief.

Da lachten die Geister im lustigen Chor;

Im weissen Flausch trat ein Vierter hervor:

Vom Katheder schwatzte herab der Professor,

Er schwatzte, und ich schlief gut dabei ein;

Doch haett mirs behagt noch tausendmal besser

Bei seinem holdseligen Toechterlein.

Sie hat mir oft zaertlich am Fenster genicket,

Die Blume der Blumen, mein Lebenslicht!

Doch die Blume der Blumen ward endlich gepfluecket

Vom duerren Philister, dem reichen Wicht.

Da flucht ich den Weibern und reichen Halunken,

Und mischte mir Teufelskraut in den Wein,

Und hab mit dem Tode Smollis getrunken, —

Der sprach: Fiduzit, ich heisse Freund Hein!

Da lachten die Geister im lustigen Chor;

Einen Strick um den Hals, trat ein Fuenfter hervor:

Es prunkte und prahlte der Graf beim Wein

Mit dem Toechterchen sein und dem Edelgestein.

Was schert mich, du Graeflein, dein Edelgestein?

Mir mundet weit besser dein Toechterlein.

Sie lagen wohl beid unter Riegel und Schloss,

Und der Graf besold’te viel Dienertross.

Was scheren mich Diener und Riegel und Schloss? —

Ich stieg getrost auf die Leiterspross.

An Liebchens Fensterlein klettr ich getrost,

Da hoer ich es unten fluchen erbost:

"Fein sachte, mein Buebchen, muss auch dabei sein,

Ich liebe ja auch das Edelgestein."

So spoettelt der Graf und erfasst mich gar,

Und jauchzend umringt mich die Dienerschar.

"Zum Teufel, Gesindel! ich bin ja kein Dieb;

Ich wollte nur stehlen mein trautes Lieb!"

Da half kein Gerede, da half kein Rat,

Da machte man hurtig die Stricke parat;

Wie die Sonne kam, da wundert sie sich,

Am hellen Galgen fand sie mich.

Da lachten die Geister im lustigen Chor;

Den Kopf in der Hand, trat ein Sechster hervor:

Zum Weidwerk trieb mich Liebesharm;

Ich schlich umher, die Buechs im Arm.

Da schnarrets hohl vom Baum herab,

Der Rabe rief: Kopf — ab! Kopf — ab!

O, spuert ich doch ein Taeubchen aus,

Ich braecht es meinem Lieb nach Haus!

So dacht ich, und in Busch und Strauch

Spaeht ringsumher mein Jaegeraug.

Was koset dort? was schnaebelt fein?

Zwei Turteltaeubchen moegens sein.

Ich schleich herbei, — den Hahn gespannt, —

Sieh da! mein eignes Lieb ich fand.

Das war mein Taeubchen, meine Braut,

Ein fremder Mann umarmt sie traut —

Nun, alter Schuetze, treffe gut!

Da lag der fremde Mann im Blut.

Bald drauf ein Zug mit Henkersfron —

Ich selbst dabei als Hauptperson —

Den Wald durchzog. Vom Baum herab

Der Rabe rief: Kopf — ab! Kopf — ab!

Da lachten die Geister im lustigen Chor;

Da trat der Spielmann selber hervor:

Ich hab mal ein Liedchen gesungen,

Das schoene Lied ist aus;

Wenn das Herz im Leibe zersprungen,

Dann gehen die Lieder nach Haus!

Und das tolle Gelaechter sich doppelt erhebt,

Und die bleiche Schar im Kreise schwebt.

Da scholl vom Kirchturm "Eins" herab,

Da stuerzten die Geister sich heulend ins Grab.

IX

Ich lag und schlief, und schlief recht mild,

Verscheucht war Gram und Leid;

Da kam zu mir ein Traumgebild,

Die allerschoenste Maid.

Sie war wie Marmelstein so bleich,

Und heimlich wunderbar;

Im Auge schwamm es perlengleich,

Gar seltsam wallt’ ihr Haar.

Und leise, leise sich bewegt

Die marmorblasse Maid,

Und an mein Herz sich niederlegt

Die marmorblasse Maid.

Wie bebt und pocht vor Weh und Lust

Mein Herz, und brennet heiss!

Nicht bebt, nicht pocht der Schoenen Brust,

Die ist so kalt wie Eis.

"Nicht bebt, nicht pocht wohl meine Brust,

Die ist wie Eis so kalt;

Doch kenn auch ich der Liebe Lust,

Der Liebe Allgewalt.

"Mir blueht kein Rot auf Mund und Wang,

Mein Herz durchstroemt kein Blut;

Doch straeube dich nicht schaudernd bang,

Ich bin dir hold und gut."

Und wilder noch umschlang sie mich,

Und tat mir fast ein Leid;

Da kraeht der Hahn — und stumm entwich

Die marmorblasse Maid.

X

Da hab ich viel blasse Leichen

Beschworen mit Wortesmacht;

Die wollen nun nicht mehr weichen

Zurueck in die alte Nacht.

Das zaehmende Spruechlein vom Meister

Vergass ich vor Schauer und Graus;

Nun ziehn die eignen Geister

Mich selber ins neblichte Haus.

Lasst ab, ihr finstren Daemonen!

Lasst ab, und draengt mich nicht!

Noch manche Freude mag wohnen

Hier oben im Rosenlicht.

Ich muss ja immer streben

Nach der Blume wunderhold;

Was bedeutet’ mein ganzes Leben,

Wenn ich sie nicht lieben sollt?

Ich moecht sie nur einmal umfangen

Und pressen ans gluehende Herz!

Nur einmal auf Lippen und Wangen

Kuessen den seligsten Schmerz!

Nur einmal aus ihrem Munde

Moecht ich hoeren ein liebendes Wort —

Alsdann wollt ich folgen zur Stunde

Euch, Geister, zum finsteren Ort.

Die Geister habens vernommen,

Und nicken schauerlich.

Feins Liebchen, nun bin ich gekommen;

Feins Liebchen, liebst du mich?

Heinrich Heine poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Heine, Heinrich

.jpg)

Gerard Manley Hopkins

(1844-1889)

Spring and Fall

To a young child

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

Ah! as the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you will weep and know why.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sorrow’s springs are the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

![]()

Gerard Manley Hopkins poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Classic Poetry Archive, 4SEASONS#Spring, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hopkins, Gerard Manley

.jpg)

William Butler Yeats

(1865-1939)

The Meditation Of The Old Fisherman

YOU waves, though you dance by my feet like children at play,

Though you glow and you glance, though you purr and you dart;

In the Junes that were warmer than these are, the waves were more gay,

When I was a boy with never a crack in my heart.

The herring are not in the tides as they were of old;

My sorrow! for many a creak gave the creel in the-cart

That carried the take to Sligo town to be sold,

When I was a boy with never a crack in my heart.

And ah, you proud maiden, you are not so fair when his oar

Is heard on the water, as they were, the proud and apart,

Who paced in the eve by the nets on the pebbly shore,

When I was a boy with never a crack in my heart.

Natuurdagboek Februari 2010

Hans Hermans photos

W.B. Yeats poem

► Website Hans Hermans Fotografie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Yeats, William Butler

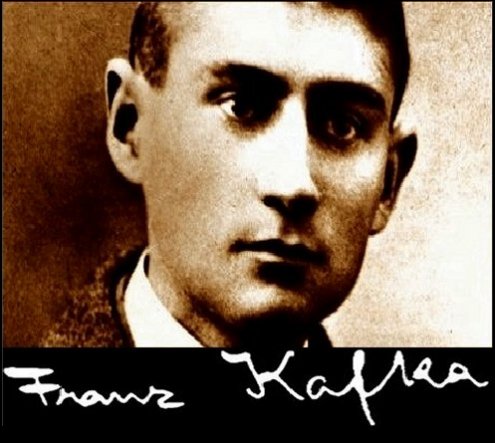

Der neue Advokat

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Wir haben einen neuen Advokaten, den Dr. Bucephalus. In seinem Äußern erinnert wenig an die Zeit, da er noch Streitroß Alexanders von Macedonien war. Wer allerdings mit den Umständen vertraut ist, bemerkt einiges. Doch sah ich letzthin auf der Freitreppe selbst einen ganz einfältigen Gerichtsdiener mit dem Fachblick des kleinen Stammgastes der Wettrennen den Advokaten bestaunen, als dieser, hoch die Schenkel hebend, mit auf dem Marmor aufklingendem Schritt von Stufe zu Stufe stieg.

Im allgemeinen billigt das Barreau die Aufnahme des Bucephalus. Mit erstaunlicher Einsicht sagt man sich, daß Bucephalus bei der heutigen Gesellschaftsordnung in einer schwierigen Lage ist und daß er deshalb, sowie auch wegen seiner weltgeschichtlichen Bedeutung, jedenfalls Entgegenkommen verdient. Heute – das kann niemand leugnen – gibt es keinen großen Alexander. Zu morden verstehen zwar manche; auch an der Geschicklichkeit, mit der Lanze über den Bankettisch hinweg den Freund zu treffen, fehlt es nicht; und vielen ist Macedonien zu eng, so daß sie Philipp, den Vater, verfluchen – aber niemand, niemand kann nach Indien führen. Schon damals waren Indiens Tore unerreichbar, aber ihre Richtung war durch das Königsschwert bezeichnet. Heute sind die Tore ganz anderswohin und weiter und höher vertragen; niemand zeigt die Richtung; viele halten Schwerter, aber nur, um mit ihnen zu fuchteln; und der Blick, der ihnen folgen will, verwirrt sich.

Vielleicht ist es deshalb wirklich das Beste, sich, wie es Bucephalus getan hat, in die Gesetzbücher zu versenken. Frei, unbedrückt die Seiten von den Lenden des Reiters, bei stiller Lampe, fern dem Getöse der Alexanderschlacht, liest und wendet er die Blätter unserer alten Bücher.

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

Anne Brontë

(1820-1849)

Vanitas Vanitatum,

Omnia Vanitas

In all we do, and hear, and see,

Is restless Toil and Vanity.

While yet the rolling earth abides,

Men come and go like ocean tides;

And ere one generation dies,

Another in its place shall rise;

THAT, sinking soon into the grave,

Others succeed, like wave on wave;

And as they rise, they pass away.

The sun arises every day,

And hastening onward to the West,

He nightly sinks, but not to rest:

Returning to the eastern skies,

Again to light us, he must rise.

And still the restless wind comes forth,

Now blowing keenly from the North;

Now from the South, the East, the West,

For ever changing, ne’er at rest.

The fountains, gushing from the hills,

Supply the ever-running rills;

The thirsty rivers drink their store,

And bear it rolling to the shore,

But still the ocean craves for more.

‘Tis endless labour everywhere!

Sound cannot satisfy the ear,

Light cannot fill the craving eye,

Nor riches half our wants supply,

Pleasure but doubles future pain,

And joy brings sorrow in her train;

Laughter is mad, and reckless mirth–

What does she in this weary earth?

Should Wealth, or Fame, our Life employ,

Death comes, our labour to destroy;

To snatch the untasted cup away,

For which we toiled so many a day.

What, then, remains for wretched man?

To use life’s comforts while he can,

Enjoy the blessings Heaven bestows,

Assist his friends, forgive his foes;

Trust God, and keep His statutes still,

Upright and firm, through good and ill;

Thankful for all that God has given,

Fixing his firmest hopes on Heaven;

Knowing that earthly joys decay,

But hoping through the darkest day.

Memory

Brightly the sun of summer shone

Green fields and waving woods upon,

And soft winds wandered by;

Above, a sky of purest blue,

Around, bright flowers of loveliest hue,

Allured the gazer’s eye.

But what were all these charms to me,

When one sweet breath of memory

Came gently wafting by?

I closed my eyes against the day,

And called my willing soul away,

From earth, and air, and sky;

That I might simply fancy there

One little flower–a primrose fair,

Just opening into sight;

As in the days of infancy,

An opening primrose seemed to me

A source of strange delight.

Sweet Memory! ever smile on me;

Nature’s chief beauties spring from thee;

Oh, still thy tribute bring

Still make the golden crocus shine

Among the flowers the most divine,

The glory of the spring.

Still in the wallflower’s fragrance dwell;

And hover round the slight bluebell,

My childhood’s darling flower.

Smile on the little daisy still,

The buttercup’s bright goblet fill

With all thy former power.

For ever hang thy dreamy spell

Round mountain star and heather bell,

And do not pass away

From sparkling frost, or wreathed snow,

And whisper when the wild winds blow,

Or rippling waters play.

Is childhood, then, so all divine?

Or Memory, is the glory thine,

That haloes thus the past?

Not ALL divine; its pangs of grief

(Although, perchance, their stay be brief)

Are bitter while they last.

Nor is the glory all thine own,

For on our earliest joys alone

That holy light is cast.

With such a ray, no spell of thine

Can make our later pleasures shine,

Though long ago they passed.

Anne Brontë poetry

fleursdumal magazine

More in: Anne, Emily & Charlotte Brontë, Brontë, Anne, Emily & Charlotte

.jpg)

.jpg)

Monica Richter:

F a r e w e l l

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Monica Richter

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature