Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

Esther Porcelijn

Pest me maar en vraag dan hoe mijn oma heet

Er was eens een jongen met blonde krullen die ik tegenkwam in een dorp, een dorp zo klein dat je niet zou kunnen zeggen dat het bestaat.

Hij vroeg mij wat ik ervaar aan mijn schaamhaar.

Dit is mijn antwoord:

Dag 1:

Mijn schaamhaar is een wirwar.

Een wirwar aan politiek correcte mogelijkheden.

Elke dag weer vertellen de haren mij wat ik die dag moet doen.

De ene dag moet ik vóór zijn, de andere dag anti. Meer vóór dan anti natuurlijk, anders zouden het geen politiek correcte haren zijn.

Het zijn mijn vrienden, zo zal ik ze vanaf nu noemen, mijn vrienden.

Ze dwalen soms af, vertellen mij dat ik president moet worden, of dat ik met ze moet flossen.

Daar heb ik geen zin in, is dat raar?

Geschrokken kijken ze mij aan, recht overeind staan ze te gluren naar hoe ik wakker word.

Als ik te lang slaap prikken ze, ze gunnen mij geen nachtrust.

Dan word ik gedwongen om mensen argwanend aan te kijken, dat doen zij, zij zijn de schuldigen daarvan. Mijn argwanende blik moet net zo priemen als de haren in mijn onderbroek, de vrienden in mijn onderbroek!

Op een dag heb ik een oud vrouwtje geslagen, zomaar opeens.

Ze schreeuwde naar mij; “jij vuil wezen, jij bent niet meer dan een lampenkap, een lampenkap met grote oren.” Zodoende heb ik haar geslagen, en terecht verdomme!

Oude vrouwtjes zijn afgrijselijke schepsels, ze klagen en steunen, hebben altijd ziektes.

Wat is dat nou eigenlijk, mensen met ziektes? Ik vind het je reinste aanstellerij, schurft is het.

Een persoon met een ziekte heeft altijd schurft.

Zo ook het oude vrouwtje, dat moet haast wel, de rode vlokken vloekten met haar paarse regenkapje. En dan maar mindervalide zijn hè! Schurft heb je, hoer!

Ik zwaai elke ochtend naar mijn buurman, dat moet van mijn vrienden.

Kijkend uit zijn raam staat hij in zijn onderbroek de bloemen water te geven uit een knal oranje gieter.

Hij zwaait altijd als eerste, hij heeft knokige handen.

Ik kan zijn handen niet echt zien, maar ik weet het omdat hij zijn vingers heel langzaam uit elkaar haalt, het gaat moeizaam.

Zijn vingers blijven een beetje gebogen, hij heeft ook lange vingers.

En dan zwaai ik terug, en doe alsof ik mijn bloemen ook water geef.

Misschien dat hij ook vrienden in zijn onderbroek heeft.

Dag 2:

Ik heb mijzelf zojuist tegen een raam aan gegooid.

Flikkerend danst de lamp nog om mijn hoofd.

Geruisloos stampen de muizen onder mijn benen, ze dragen mij naar de andere kant van de kamer.

Ik sta op en krabbel aan mijn vrienden, woedend sissen ze.

De buurman zie ik nog net een slokje nemen uit zijn gieter. Goedzo buurman, geniet maar van de ochtend, en als er jenever in zit worden de bloemen dronken!

Geweldige blauwe plekken op mijn zij, en het raam ligt aan gruzelementen.

Genot is niet altijd vindbaar in pijn.

De buurman zwaait nu, dag buurman!

De buurman krabt aan iets dat net onder de vensterbank zit, waarschijnlijk aan zijn vrienden.

Ik doe hetzelfde.

Ik huil.

Er valt een traan op mijn knie, en dan besef ik dat mijn knie zo dik is geworden als een doos bonbons.

Ik leg mijn been in de ijskast, het verkoelt maar het bevriest mij langzaam.

Denken hoeft even niet in deze kou.

De kamer ziet er gek uit zo. Zou ik nu dan ook op het plafond kunnen lopen?

En als ik nu met mijn gieter giet, blijven de druppels dan zweven in de kamer, richtingloos?

Mijn lichaam voelt kapot, gebroken stukjes bot rammelen in de maat.

Glasscherven glinsteren in mijn elleboog.

Mijn vrienden sissen kwaadaardig tegen mij, ze trekken mij een kant op.

Ik word meegetrokken door ze.

Ik rol richting de verwarming, met de ijskast nog bevroren aan mijn knie.

Dan lig ik tegen de verwarming. Het voelt hetzelfde, de kou en de warmte.

Mijn vrienden zingen zachtjes een liedje:

Plaag me

Plaag me

Draai een rondje en wees blij

Gezond is ieder die

Erbij is als het hagelt

Pest me

Pest me

Drie keer om de tuin

Vier keer roepen

Dat je mooi bent

Pest me maar

En vraag dan

Hoe mijn oma heet.

Ik voel opeens in mijn onderbroek, iets nats.

Ik ben klaargekomen.

Maar, ik ben klaargekomen als een man.

Esther Porcelijn: Pest me maar en vraag dan hoe mijn oma heet

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Esther Porcelijn

Ehm excuseer mijnheer…

Een man komt vluchtend op, in paniek, kiest heel precies zijn positie. Hij is alleen.

Hij doet zijn boordje goed.

“klop klop.. wie is daar? IK….. ja…”

Er lopen verschillende vrouwen langs, met snor, bril, lelijk, mooi.

Bij één biedt hij zich aan om tegen te spreken, maar ze reageert niet.

Er komt nog een vrouw aan, hij biedt zich aan en..

“Ehm excuseer meneer.. kunt u mij de weg naar het station vertellen?”

De weg, de weg, nou.. ja….

De weg naar het station? Of ik die zomaar kan vertellen?

Er is niet één weg mejuffrouw, u zou rechts, links kunnen, onzichtbaar, of koprollend.

Ik zou u op mijn rug kunnen dragen, als hond of als paard.

Als paard naar het station, met u op mijn rug.

Dan zijn we op weg, op weg.

Ze dulden geen paarden in de trein mejuffrouw, dat is toch wel lastig denk ik, zorgt voor weerstand kan ik u wel vertellen, vermoed ik.

Maar als u mij als paard nou even in uw aktetas doet?

Dat scheelt ook nog tijd.

Waar gaan we dan heen?

Vrouw: weerzinwekkend.

Man: Spannend hè?

Waar zullen we heengaan, u ziet eruit als iemand die houdt van verre oorden, op weg naar verre oorden. Lijkt mij wel wat.

Zimbabwe?

Duurt even, maar als paard ben ik zeer vermakelijk.

En als we daar zijn, haalt u mij weer uit uw aktetas, of stiekem in de trein, zo nu en dan als niemand kijkt.

U weet de weg niet hè?

Nou, ver kan het niet zijn, nog niet op de helft van de wereld.

Ook nog wel fijn samen.

Recht door, het had iets te maken met rechtdoor…

Doorsteken over de oceaan.

Met wat hooi komen we denk ik een heel end.

Maar als we eerder willen uitstappen kan dat ook, dan pakken we de boot om onder water wat vissen te zoeken.

We moeten natuurlijk wel wat eten.

En als u verliefd wordt op.. op… de natuur, dan wil ik daar ook best wat tijd voor vrijmaken.

Al zullen mijn paardenhoeven zo af en toe klikken, zelfs op zand klikken ze, mooi klinkt dat hoor, poeh, nou en of!

En aangezien ik dan paardenbenen heb, heb ik, u hoort het al, BENEN, en met benen kun je een stuk meer.

Vrouw: Potsierlijk!

Man: Spannend hè?

Maar goed, u moet dus twee rondjes lopen, en dan op één arm tegen het stoplicht leunen, aan de rechter kant. Anders komt u er niet, echt waar eerlijk niet!

U moet en zal er komen.

Het is in elk geval nooit dichtbij, dat is iets dat zeker is.

U ziet eruit als iemand die grote stappen kan maken, ondanks uw zeer delicate voetformaat.

Maar u zet stappen, en niet zomaar stappen, grootse stappen, op weg naar verre oorden.

O en als we nou eens omlaag gaan, richting Australië, waarschijnlijk nog midden in Australië ook, zal je altijd zien!

En dan kunnen we picknicken op Ayers Rock.

En kijken hoe de Aboriginees larven eten, van die dikke witte, en het kopje blijft leven, daar moet je hem vastpakken, bij het kopje. En dan HAP.

Maar het was dus perron 3, perron drie is niet zo ver, als het nu 4 was, had dat behoorlijk uitgemaakt, trappenstelsels lopen soms erg in de knoop, en voor je het weet, moet je iemand met erg lange nagels hebben, zonder dat die je openkrabt..

Vrouw: begint op zijn rug te krabben

Man: Oee ja daar..iet lager, werkelijk iets lager ja, já dáár, precies daar, oei nee net mis ha.. haa… ja ja ja ja ja…

Vrouw: (krabt nog altijd op zijn rug) Ik moet echt gaan meneer, ik ben te laat.

Man: Maar mens! Vrouw, edele dame, snap dat dan. U komt nooit te laat want we zullen overal zijn, we zijn waarschijnlijk eerder te vroeg dan te laat..

Vrouw: Ik moet toch echt gaan

Man: pakt haar hand vast en gaat door zijn kniën. Dat hoeft niet, u houdt meer van luxe, ik snap het al, luxe. We kunnen ons baden in luxe.. dat gaan we doen, we gaan naar de noordpool en ons baden in ijskoude luxe, als zeehonden onze huid vetten met luxe.

Het uitsmeren over onze gezichten en ik ga u vertellen hoe prachtig luxieus u eruitziet.

Vrouw: Ja het is zo ver. Ik heb mijn trein gemist.

Man: pakt haar vast Dat is niet altijd zo zeker, want perron drie is toch echt minder ver, u haalt het, u kan het, het is onbeschrijfelijk dichtbij.

Vrouw is ondertussen al begonnen met lopen naar de deur, de man zakt langs haar lichaam omlaag en hang aan haar been, zij sleept hem voort.

Kunt u misschien niet tegen de warmte.. de hitte van de zon is zeker iets om te overwegen, en op de noordpool kan hij zeer sterk zijn. We smelten samen..

De vrouw kijkt hem treurig aan, schudt hem van haar been, en vertrekt.

De man is alleen.

U bent al te laat, u zal er nu niet meer komen, pas om 12.34 gaat er iets richting de wereld, tot die tijd bent u verloren madamme!

De man staat op, kijkt om zich heen, loopt naar de deur waar hij vandaan komt, doet hem open, wordt bang. Hij pakt zijn biezen en loopt af terwijl hij zijn boordje goed doet.

Esther Porcelijn: Ehm excuseer mijnheer…

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Esther Porcelijn

Een nacht met de professor

(monoloog voor een wegdromend meisje tijdens college)

Hij strijkt mij door de haren.

Vertelt mij dat ik dezelfde

ogen heb als Nietzsche.

Een hand onder mijn rokje

waar vlokken…vlagen van

weemoed als kristallen brokkelen

Scribbeldiwee

Scribbeldiwa

Gedanst in de kamer met rond mij

alle kennis die ik nodig heb

om ooit net zo groots wijs te worden als hij.

Waar zitten zijn wetenswaardigheden?

Wat moet ik doen, waar moet ik op lijken

om op hem te lijken.

Zijn baard prikt in mijn hersenpan

en ik, ik zoek nog verder naar beneden

is daar iets te halen?

Kluwen vrijpostigheid

zitten zich daar te schamen

te schamen voor hun onvermogen.

Als God in de kamer was

zou hij tevreden zijn.

Het zoeken schijnt belangrijker te wezen.

Woorden als: kleistervrouw, pepermuralis, klavertjevierigheid.

Zo klinken ze in mijn oren als hij ze zegt.

Ik zal ze misschien wel nooit begrijpen.

Ze zijn doelloos

dwalen mijn hoofd in

en uit.

En dan toch..

toch wil ik dat hij verdwijnt in mij.

Zijn Kant in mijn Plato.

Zodat ik net zo goeroe..net zo scribbeldiwee

als zijn plagend gekwartselde..

Zijn questiquatis.

Hij veegt de vloer met mij aan..

Mijn voeten heeft hij vast, hij dweilt met mijn haren en schreeuwt:

“ik weet niks, ik weet niks.”

Zo wijs is hij, om te weten dat hij niets weet.

Hij zal nooit van mij houden.

Want

dat is precies hetgeen

ik niet weet.

Esther Porcelijn poëzie

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

.jpg)

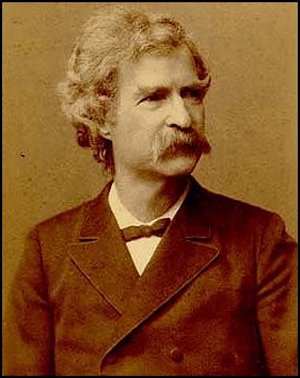

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

After the Fall

When I look back, the Garden is a dream to me. It was beautiful, surpassingly beautiful, enchantingly beautiful; and now it is lost, and I shall not see it any more.

The Garden is lost, but I have found him, and am content. He loves me as well as he can; I love him with all the strength of my passionate nature, and this, I think, is proper to my youth and sex. If I ask myself why I love him, I find I do not know, and do not really much care to know; so I suppose that this kind of love is not a product of reasoning and statistics, like one’s love for other reptiles and animals. I think that this must be so. I love certain birds because of their song; but I do not love Adam on account of his singing—no, it is not that; the more he sings the more I do not get reconciled to it. Yet I ask him to sing, because I wish to learn to like everything he is interested in. I am sure I can learn, because at first I could not stand it, but now I can. It sours the milk, but it doesn’t matter; I can get used to that kind of milk.

It is not on account of his brightness that I love him—no, it is not that. He is not to blame for his brightness, such as it is, for he did not make it himself; he is as God made him, and that is sufficient. There was a wise purpose in it, that I know. In time it will develop, though I think it will not be sudden; and besides, there is no hurry; he is well enough just as he is.

It is not on account of his gracious and considerate ways and his delicacy that I love him. No, he has lacks in these regards, but he is well enough just so, and is improving.

It is not on account of his industry that I love him—no, it is not that. I think he has it in him, and I do not know why he conceals it from me. It is my only pain. Otherwise he is frank and open with me, now. I am sure he keeps nothing from me but this. It grieves me that he should have a secret from me, and sometimes it spoils my sleep, thinking of it, but I will put it out of my mind; it shall not trouble my happiness, which is otherwise full to overflowing.

It is not on account of his education that I love him—no, it is not that. He is self-educated, and does really know a multitude of things, but they are not so.

It is not on account of his chivalry that I love him—no, it is not that. He told on me, but I do not blame him; it is a peculiarity of sex, I think, and he did not make his sex. Of course I would not have told on him, I would have perished first; but that is a peculiarity of sex, too, and I do not take credit for it, for I did not make my sex.

Then why is it that I love him? Merely because he is masculine, I think.

At bottom he is good, and I love him for that, but I could love him without it. If he should beat me and abuse me, I should go on loving him. I know it. It is a matter of sex, I think.

He is strong and handsome, and I love him for that, and I admire him and am proud of him, but I could love him without those qualities. If he were plain, I should love him; if he were a wreck, I should love him; and I would work for him, and slave over him, and pray for him, and watch by his bedside until I died.

Yes, I think I love him merely because he is mine and is masculine. There is no other reason, I suppose. And so I think it is as I first said: that this kind of love is not a product of reasonings and statistics. It just comes—none knows whence—and cannot explain itself. And doesn’t need to.

It is what I think. But I am only a girl, and the first that has examined this matter, and it may turn out that in my ignorance and inexperience I have not got it right.

Forty Years Later

It is my prayer, it is my longing, that we may pass from this life together—a longing which shall never perish from the earth, but shall have place in the heart of every wife that loves, until the end of time; and it shall be called by my name.

But if one of us must go first, it is my prayer that it shall be I; for he is strong, I am weak, I am not so necessary to him as he is to me—life without him would not be life; how could I endure it? This prayer is also immortal, and will not cease from being offered up while my race continues. I am the first wife; and in the last wife I shall be repeated.

At Eve’s Grave

Adam: Wheresoever she was, there was Eden.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Esther Porcelijn

Monoloog voor een man,

alleen in de woestijn in een tent

Man:

Nu vroeg ik mij af, waarom krijg ik teveel?

Teveel zand, teveel aandacht in één keer.

Teveel mensen op één dag.

Teveel verspreide eenzaamheid.

Ik bouw dit. Langzaam, maar ik bouw het.

Mijn salamander ben ik kwijt.

Mijn vrouw is zoek.

“Het is op,” zei ze..

En toch telkens teveel: als dit dan dat, dan zo, dan rood, als zwart dan avond, als wit dan sneeuw, maar wit is het nooit echt.

Alleen als ik soms door mijn wimpers kijk, in de ochtend.

Wanneer is het ochtend, maakt het wel iets uit?

Of ik nu slaap of niet, de tijd is verdreven.

Ooit had ik hem, tijd..

Er zat een tijd tussen, tussen dat ik tijd had en hem had weggejaagd.

Toen ook ergens raakte mijn vrouw zoek.

Poef, opeens met het zand.

Ik dacht even dat ik het verzon.

Dat is waarschijnlijk niet zo.

Waarschijnlijk ben ik nog wel meer kwijt….Sommige dagen komen er mannen, drie mannen met jurken die komen langs.

Soms zingen ze een lied.

Ik vind drie teveel van het goede

Enkele vogels zie ik wel.

Vaak teveel, in elk geval teveel.

Als er iets zou zijn als zee.. wat zou ik tevreden zijn, en vrij.

Verkoeling.

Maar water komt nooit alleen.

Het is met z’n velen.

Kon ik maar..

Kon ik maar één water..

Verdrink ik bijna.

Nu ook, kijk maar: “…” (man doet alsof hij verdrinkt)

Hoe waterig was dat?

Mijn vrouw, mijn vrouw is weggevlogen met de vogels.

Vier was wel genoeg voor haar denk ik..

Mijn plek, waar ik altijd zit, is weggevaagd.

Althans dat zou zo moeten zijn, het is niet zo, dat kan ook. Allebei..

Één gedachte, waarom nou nooit één gedachte?

Één vraag, maar één keer één geluid in mijn hoofd.

De zandkorrels zijn mijn gedachten..

Als de zon groen zou zijn, zou ik alleen daarover hoeven denken.

Maar het is niet zo, dat kan ook. Allebei.

1+1+1+1+1+1= iets van 8 ofzo.

1 kan nooit alleen 1 zijn. Het is en was iets.. altijd twee.

Teveel, teveel..

Als ik mijn salamander nu toch had.

Dan zou ik kunnen dromen, op mijn niet te vervagen plek.

Kunnen dromen over de groene zon.

(man tegen zichzelf): Blijven denken aan één ding!

Als de zeekoe maar water heeft, veel zeekoe maar wel in zijn eentje.

Alleene zeekoe vermoeid van de hoestsiroop..

Waar zijn mijn vogels? Mijn witte sneeuwvogels?

Ze waren met zoveel.. wel drie ongeveer.

Als een ader door de sporen van een ratelslang..

Wit is het nooit echt, ook de vogels niet..

Als ik nooit zou liegen zou mijn plek, de plek waar ik zit, nu onder de aarde zijn.

Maar het is omgekeerd, en dat kan ook.

(Tegen zichzelf): Éen ding!

Zandkorrels tellen blijft een verleiding, maar ik laat me niet verleiden..

Niet door getallen, getallen zijn altijd teveel.

De witte vogels, de mannen, de vogels. Ze waren weg, zoek..

Waar blijft het, hetgeen ik…

Nee, ja, jawel.. er is meer níet dan wél..

Liefde.. waar is ze? De vogels, wit maar soms niet.

Ik zit maar. Onder de grond maar dan omgekeerd.

Die getallen.. ik laat me niet verleiden

Ga toch weg, laat me met rust!

Mijn lief is zoek…

Ze is weggeweest, gegaan.. veredeld.. verregend.. laat me!

Ze is zoek en ik laat me niet verleiden, nee! 1.

Nee niet! (er klinkt muziek als van een orkest dat de instrumenten stemt)

1,2,3, 1,2,3. Gevlucht! Vlucht dan!!

Mijn groene zon, één ding! Nee! 1,2,3.. (orkest begint met een stuk van Frank Zappa)

Laat me! Laat me!…………………. Ik ben alleen! 1,2,3…….

(de man dirigeert)

Esther Porcelijn prose & poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

.jpg)

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

Extract from Adam’s Diary

Perhaps I ought to remember that she is very young, a mere girl, and make allowances. She is all interest, eagerness, vivacity, the world is to her a charm, a wonder, a mystery, a joy; she can’t speak for delight when she finds a new flower, she must pet it and caress it and smell it and talk to it, and pour out endearing names upon it. And she is color-mad: brown rocks, yellow sand, gray moss, green foliage, blue sky; the pearl of the dawn, the purple shadows on the mountains, the golden islands floating in crimson seas at sunset, the pallid moon sailing through the shredded cloud-rack, the star-jewels glittering in the wastes of space—none of them is of any practical value, so far as I can see, but because they have color and majesty, that is enough for her, and she loses her mind over them. If she could quiet down and keep still a couple of minutes at a time, it would be a reposeful spectacle. In that case I think I could enjoy looking at her; indeed I am sure I could, for I am coming to realize that she is a quite remarkably comely creature—lithe, slender, trim, rounded, shapely, nimble, graceful; and once when she was standing marble- white and sun-drenched on a bowlder, with her young head tilted back and her hand shading her eyes, watching the flight of a bird in the sky, I recognized that she was beautiful.

Monday noon.—If there is anything on the planet that she is not interested in it is not in my list. There are animals that I am indifferent to, but it is not so with her. She has no discrimination, she takes to all of them, she thinks they are all treasures, every new one is welcome.

When the mighty brontosaurus came striding into camp, she regarded it as an acquisition, I considered it a calamity; that is a good sample of the lack of harmony that prevails in our views of things. She wanted to do mesticate it, I wanted to make it a present of the homestead and move out. She believed it could be tamed by kind treatment and would be a good pet; I said a pet twenty-one feet high and eighty-four feet long would be no proper thing to have about the place, because, even with the best intentions and without meaning any harm, it could sit down on the house and mash it, for any one could see by the look of its eye that it was absent-minded.

Still, her heart was set upon having that monster, and she couldn’t give it up. She thought we could start a dairy with it, and wanted me to help her milk it; but I wouldn’t; it was too risky. The sex wasn’t right, and we hadn’t any ladder anyway. Then she wanted to ride it, and look at the scenery. Thirty or forty feet of its tail was lying on the ground, like a fallen tree, and she thought she could climb it, but she was mistaken; when she got to the steep place it was too slick and down she came, and would have hurt herself but for me.

Was she satisfied now? No. Nothing ever satisfies her but demonstration; untested theories are not in her line, and she won’t have them. It is the right spirit, I concede it; it attracts me; I feel the influence of it; if I were with her more I think I should take it up myself. Well, she had one theory remaining about this colossus: she thought that if we could tame him and make him friendly we could stand him in the river and use him for a bridge. It turned out that he was already plenty tame enough—at least as far as she was concerned—so she tried her theory, but it failed: every time she got him properly placed in the river and went ashore to cross over on him, he came out and followed her around like a pet mountain. Like the other animals. They all do that.

Friday.—Tuesday—Wednesday—Thursday—and to-day: all without seeing him. It is a long time to be alone; still, it is better to be alone than unwelcome.

I had to have company—I was made for it, I think—so I made friends with the animals. They are just charming, and they have the kindest disposition and the politest ways; they never look sour, they never let you feel that you are intruding, they smile at you and wag their tail, if they’ve got one, and they are always ready for a romp or an excursion or anything you want to propose. I think they are perfect gentlemen. All these days we have had such good times, and it hasn’t been lonesome for me, ever. Lonesome! No, I should say not. Why, there’s always a swarm of them around—sometimes as much as four or five acres—you can’t count them; and when you stand on a rock in the midst and look out over the furry expanse it is so mottled and splashed and gay with color and frisking sheen and sun-flash, and so rippled with stripes, that you might think it was a lake, only you know it isn’t; and there’s storms of sociable birds, and hurricanes of whirring wings; and when the sun strikes all that feathery commotion, you have a blazing up of all the colors you can think of, enough to put your eyes out.

We have made long excursions, and I have seen a great deal of the world; almost all of it, I think; and so I am the first traveller, and the only one. When we are on the march, it is an imposing sight—there’s nothing like it anywhere. For comfort I ride a tiger or a leopard, because it is soft and has a round back that fits me, and because they are such pretty animals; but for long distance or for scenery I ride the elephant. He hoists me up with his trunk, but I can get off myself; when we are ready to camp, he sits and I slide down the back way. The birds and animals are all friendly to each other, and there are no disputes about anything. They all talk, and they all talk to me, but it must be a foreign language, for I cannot make out a word they say; yet they often understand me when I talk back, particularly the dog and the elephant. It makes me ashamed. It shows that they are brighter than I am, and are therefore my superiors. It annoys me, for I want to be the principal Experiment myself—and I intend to be, too. I have learned a number of things, and am educated, now, but I wasn’t at first. I was ignorant at first. At first it used to vex me because, with all my watching, I was never smart enough to be around when the water was running up-hill; but now I do not mind it. I have experimented and experimented until now I know it never does run uphill, except in the dark. I know it does in the dark, because the pool never goes dry; which it would, of course, if the water didn’t come back in the night. It is best to prove things by actual experiment; then you know; whereas if you depend on guessing and supposing and conjecturing, you will never get educated.

Some things you can’t find out; but you will never know you can’t by guessing and supposing: no, you have to be patient and go on experimenting until you find out that you can’t find out. And it is delightful to have it that way, it makes the world so interesting. If there wasn’t anything to find out, it would be dull. Even trying to find out and not finding out is just as interesting as trying to find out and finding out, and I don’t know but more so. The secret of the water was a treasure until I got it; then the excitement all went away, and I recognized a sense of loss. By experiment I know that wood swims, and dry leaves, and feathers, and plenty of other things; therefore by all that cumulative evidence you know that a rock will swim; but you have to put up with simply knowing it, for there isn’t any way to prove it—up to now. But I shall find a way—then that excitement will go. Such things make me sad; because by-and-by when I have found out everything there won’t be any more excitements, and I do love excitements so! The other night I couldn’t sleep for thinking about it.

At first I couldn’t make out what I was made for, but now I think it was to search out the secrets of this wonderful world and be happy and thank the Giver of it all for devising it. I think there are many things to learn yet—I hope so; and by economizing and not hurrying too fast I think they will last weeks and weeks. I hope so. When you cast up a feather it sails away on the air and goes out of sight; then you throw up a clod and it doesn’t. It comes down, every time. I have tried it and tried it, and it is always so. I wonder why it is? Of course it doesn’t come down, but why should it seem to? I suppose it is an optical illusion. I mean, one of them is. I don’t know which one. It may be the feather, it may be the clod; I can’t prove which it is, I can only demonstrate that one or the other is a fake, and let a person take his choice.

By watching, I know that the stars are not going to last. I have seen some of the best ones melt and run down the sky. Since one can melt, they can all melt; since they can all melt, they can all melt the same night. That sorrow will come—I know it. I mean to sit up every night and look at them as long as I can keep awake; and I will impress those sparkling fields on my memory, so that by-and-by when theyare taken away I can by my fancy restore those lovely myriads to the black sky and make them sparkle again, and double them by the blur of my tears.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

Extract from Adam’s Diary (Eve’s Diary II)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

Esther Porcelijn

Happig

Ik zie je daar wel zitten, met je glimlach.

Met je haren zo perfect en je sik.

Je straalt van onderbuik en van gezag

En je geeft ondanks mijn pogen niet één blik.

Ik zie je daar wel zitten, met je overdaad

Hoe siert het je, en zonder blozen

Bestel je een drankje en dan nog een, raad

Eens hoe ik jou wil liefkozen

Is de drank voor mij, of voor een ander

Een mooiere, bijzondere, één met borsten

Zo een met onderdaad, zo een die jou verandert

Een zonder schurft en zonder korsten

Zij is misschien precies het meest perfecte

Juist omdat zij alles niet heeft dat jij wel

Maar ik heb alles dat jij wel, ik heb.

Je hoeft niet altijd de beste te zijn

Maar ik ben hier en heb ook zin in wijn

Ik voel niets (dan de hoop), kijk naar mij!

Kijk naar mij, zie mij dan, bestel er een.

En loop dan naar mij toe met je smoel en met je houding

En vertel mij over alle dromen en gedachten en hoe ik die ook heb

Dan rennen we weg en zwemmen we in oceanen ver hiervandaan

Er komt een vrouw binnen, je kijkt blij

Één wijn te weinig nu

Wat had ik gelukkig kunnen zijn.

“Barman! Twee wijn voor mij alleen graag."

Esther Porcelijn poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Esther Porcelijn

in voorstelling Over/Leven

Esther Porcelijn (1985) is toneelspeler en maakt ook zelf voorstellingen. Komend seizoen speelt ze in de voorstelling: “De Ingebeelde Zieke” van Molière van De Utrechtse Spelen onder leiding van Jos Thie met spelers als: Loes Luca, Tjitske Reidinga, Paul Kooij, Mini & Maxi e.a.

Esther schrijft gedichten, versjes, korte verhalen, monologen en dialogen. Vaak vanuit het perspectief van een personage: hoe iemand denkt, wat een ander persoon zou doen. Ze houdt van de eigenaardigheid en geestigheid van het leven en wil mensen door het lezen van haar gedichten meevoeren in haar soms absurde gedachtewereld. Ook houdt ze van sterke ritmes, mooie klanken, de schoonheid van taal, maar ook van ongemakkelijke situaties tussen mensen. Esther treedt regelmatig op met haar verhalen en gedichten om mensen te laten horen wat ze heeft geschreven, te laten luisteren naar haar eigen taal.

Na haar studie aan de Toneelacademie in Maastricht is Esther Porcelijn begonnen aan een tweede studie. Ze studeert Filosofie aan de Universiteit van Tilburg. Aan deze studie is ze begonnen met het doel om een betere schrijver te worden. Het leert haar om strenger te denken en om beter te zien wanneer iets klopt en wanneer niet. Bovendien vindt ze het ook fascinerend om te zien hoe mensen, door de tijd heen, totaal anders zijn gaan denken.

.jpg)

Momenteel is Esther Porcelijn bezig met een eigen theatervoorstelling. Deze voorstelling heet “Over/Leven” en is onderdeel van een avondvullend programma in Club Trouw in Amsterdam. De voorstelling wordt geregisseerd door Fransje Christiaans en Esther speelt samen met Jasper Hupkens. De voorstelling gaat over de vraag of er méér is na de dood en als dit zo is, of de kennis daarover iets oplevert voor het leven nú. Het stuk wordt op 16 en 17 februari 2011 opgevoerd.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther, THEATRE

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

Eve’s Diary

Translated from the original

Saturday.—I am almost a whole day old, now. I arrived yesterday. That is as it seems to me. And it must be so, for if there was a day-before-yesterday I was not there when it happened, or I should remember it. It could be, of course, that it did happen, and that I was not noticing. Very well; I will be very watchful, now, and if any day-before-yesterdays happen I will make a note of it. It will be best to start right and not let the record get confused, for some instinct tells me that these details are going to be important to the historian some day. For I feel like an experiment, I feel exactly like an experiment; it would be impossible for a person to feel more like an experiment than I do, and so I am coming to feel convinced that that is what I am—an experiment; just an experiment, and nothing more.

Then if I am an experiment, am I the whole of it? No, I think not; I think the rest of it is part of it. I am the main part of it, but I think the rest of it has its share in the matter. Is my position assured, or do I have to watch it and take care of it? The latter, perhaps. Some instinct tells me that eternal vigilance is the price of supremacy. [That is a good phrase, I think, for one so young.]

Everything looks better to-day than it did yesterday. In the rush of finishing up yesterday, the mountains were left in a ragged condition, and some of the plains were so cluttered with rubbish and remnants that the aspects were quite distressing. Noble and beautiful works of art should not be subjected to haste; and this majestic new world is indeed a most noble and beautiful work. And certainly marvellously near to being perfect, notwithstanding the shortness of the time. There are too many stars in some places and not enough in others, but that can be remedied presently, no doubt. The moon got loose last night, and slid down and fell out of the scheme—a very great loss; it breaks my heart to think of it. There isn’t another thing among the ornaments and decorations that is comparable to it for beauty and finish. It should have been fastened better. If we can only get it back again—

But of course there is no telling where it went to. And besides, whoever gets it will hide it; I know it because I would do it myself. I believe I can be honest in all other matters, but I already begin to realize that the core and centre of my nature is love of the beautiful, a passion for the beautiful, and that it would not be safe to trust me with a moon that belonged to another person and that person didn’t know I had it. I could give up a moon that I found in the daytime, because I should be afraid some one was looking; but if I found it in the dark, I am sure I should find some kind of an excuse for not saying anything about it. For I do love moons, they are so pretty and so romantic. I wish we had five or six; I would never go to bed; I should never get tired lying on the moss-bank and looking up at them. Stars are good, too. I wish I could get some to put in my hair. But I suppose I never can. You would be surprised to find how far off they are, for they do not look it. When they first showed, last night, I tried to knock some down with a pole, but it didn’t reach, which astonished me; then I tried clods till I was all tired out, but I never got one. It was because I am left-handed and cannot throw good. Even when I aimed at the one I wasn’t after I couldn’t hit the other one, though I did make some close shots, for I saw the black blot of the clod sail right into the midst of the golden clusters forty or fifty times, just barely missing them, and if I could have held out a little longer maybe I could have got one.

So I cried a little, which was natural, I suppose, for one of my age, and after I was rested I got a basket and started for a place on the extreme rim of the circle, where the stars were close to the ground and I could get them with my hands, which would be better, anyway, because I could gather them tenderly then, and not break them. But it was farther than I thought, and at last I had to give it up; I was so tired I couldn’t drag my feet another step; and besides, they were sore and hurt me very much. I couldn’t get back home; it was too far and turning cold; but I found some tigers and nestled in among them and was most adorably comfortable, and their breath was sweet and pleasant, because they live on strawberries. I had never seen a tiger before, but I knew them in a minute by the stripes. If I could have one of those skins, it would make a lovely gown.

To-day I am getting better ideas about distances. I was so eager to get hold of every pretty thing that I giddily grabbed for it, sometimes when it was too far off, and sometimes when it was but six inches away but seemed a foot—alas, with thorns between! I learned a lesson; also I made an axiom, all out of my own head—my very first one: The scratched Experiment shuns the thorn. I think it is a very good one for one so young.

I followed the other Experiment around, yesterday afternoon, at a distance, to see what it might be for, if I could. But I was not able to make out. I think it is a man. I had never seen a man, but it looked like one, and I feel sure that that is what it is. I realize that I feel more curiosity about it than about any of the other reptiles. If it is a reptile, and I suppose it is; for it has frowsy hair and blue eyes, and looks like a reptile. It has no hips; it tapers like a carrot; when it stands, it spreads itself apart like a derrick; so I think it is a reptile, though it may be architecture.

I was afraid of it at first, and started to run every time it turned around, for I thought it was going to chase me; but by-and-by I found it was only trying to get away, so after that I was not timid any more, but tracked it along, several hours, about twenty yards behind, which made it nervous and unhappy. At last it was a good deal worried, and climbed a tree. I waited a good while, then gave it up and went home.

To-day the same thing over. I’ve got it up the tree again.

Sunday.—It is up there yet. Resting, apparently. But that is a subterfuge: Sunday isn’t the day of rest; Saturday is appointed for that. It looks to me like a creature that is more interested in resting than in anything else. It would tire me to rest so much. It tires me just to sit around and watch the tree. I do wonder what it is for; I never see it do anything.

They returned the moon last night, and I was so happy! I think it is very honest of them. It slid down and fell off again, but I was not distressed; there is no need to worry when one has that kind of neighbors; they will fetch it back. I wish I could do something to show my appreciation. I would like to send them some stars, for we have more than we can use. I mean I, not we, for I can see that the reptile cares nothing for such things. It has low tastes, and is not kind. When I went there yesterday evening in the gloaming it had crept down and was trying to catch the little speckled fishes that play in the pool, and I had to clod it to make it go up the tree again and let them alone. I wonder if that is what it is for? Hasn’t it any heart? Hasn’t it any compassion for those little creatures? Can it be that it was designed and manufactured for such ungentle work? It has the look of it. One of the clods took it back of the ear, and it used language. It gave me a thrill, for it was the first time I had ever heard speech, except my own. I did not understand the words, but they seemed expressive.

When I found it could talk I felt a new interest in it, for I love to talk; I talk, all day, and in my sleep, too, and I am very interesting, but if I had another to talk to I could be twice as interesting, and would never stop, if desired. If this reptile is a man, it isn’t an it, is it? That wouldn’t be grammatical, would it? I think it would be he. I think so. In that case one would parse it thus: nominative, he; dative, him; possessive, his’n. Well, I will consider it a man and call it he until it turns out to be something else. This will be handier than having so many uncertainties.

Next week Sunday.—All the week I tagged around after him and tried to get acquainted. I had to do the talking, because he was shy, but I didn’t mind it. He seemed pleased to have me around, and I used the sociable “we” a good deal, because it seemed to flatter him to be included.

Wednesday.—We are getting along very well indeed, now, and getting better and better acquainted. He does not try to avoid me any more, which is a good sign, and shows that he likes to have me with him. That pleases me, and I study to be useful to him in every way I can, so as to increase his regard.

During the last day or two I have taken all the work of naming things off his hands, and this has been a great relief to him, for he has no gift in that line, and is evidently very grateful. He can’t think of a rational name to save him, but I do not let him see that I am aware of his defect. Whenever a new creature comes along I name it before he has time to expose himself by an awkward silence. In this way I have saved him many embarrassments. I have no defect like his. The minute I set eyes on an animal I know what it is. I don’t have to reflect a moment; the right name comes out instantly, just as if it were an inspiration, as no doubt it is, for I am sure it wasn’t in me half a minute before. I seem to know just by the shape of the creature and the way it acts what animal it is.

When the dodo came along he thought it was a wild-cat—I saw it in his eye. But I saved him. And I was careful not to do it in a way that could hurt his pride. I just spoke up in a quite natural way of pleased surprise, and not as if I was dreaming of conveying information, and said, “Well, I do declare, if there isn’t the dodo!” I explained—without seeming to be explaining—how I knew it for a dodo, and although I thought maybe he was a little piqued that I knew the creature when he didn’t, it was quite evident that he admired me. That was very agreeable, and I thought of it more than once with gratification before I slept. How little a thing can make us happy when we feel that we have earned it.

Thursday.—My first sorrow. Yesterday he avoided me and seemed to wish I would not talk to him. I could not believe it, and thought there was some mistake, for I loved to be with him, and loved to hear him talk, and so how could it be that he could feel unkind towards me when I had not done anything? But at last it seemed true, so I went away and sat lonely in the place where I first saw him the morning that we were made and I did not know what he was and was indifferent about him; but now it was a mournful place, and every little thing spoke of him, and my heart was very sore. I did not know why very clearly, for it was a new feeling; I had not experienced it before, and it was all a mystery, and I could not make it out. But when night came I could not bear the lonesomeness, and went to the new shelter which he has built, to ask him what I had done that was wrong and how I could mend it and get back his kindness again; but he put me out in the rain, and it was my first sorrow.

Sunday.—It is pleasant again, now, and I am happy; but those were heavy days; I do not think of them when I can help it. I tried to get him some of those apples, but I cannot learn to throw straight. I failed, but I think the good intention pleased him. They are forbidden, and he says I shall come to harm; but so I come to harm through pleasing him, why shall I care for that harm?

Monday.—This morning I told him my name, hoping it would interest him. But he did not care for it. It is strange. If he should tell me his name, I would care. I think it would be pleasanter in my ears than any other sound.

He talks very little. Perhaps it is because he is not bright, and is sensitive about it and wishes to conceal it. It is such a pity that he should feel so, for brightness is nothing; it is in the heart that the values lie. I wish I could make him understand that a loving good heart is riches, and riches enough, and that without it intellect is poverty. Although he talks so little he has quite a considerable vocabulary. This morning he used a surprisingly good word. He evidently recognized, himself, that it was a good one, for he worked it in twice afterwards, casually. It was not good casual art, still it showed that he possesses a certain quality of perception. Without a doubt that seed can be made to grow, if cultivated. Where did he get that word? I do not think I have ever used it. No, he took no interest in my name. I tried to hide my disappointment, but I suppose I did not succeed. I went away and sat on the moss-bank with my feet in the water. It is where I go when I hunger for companionship, some one to look at, some one to talk to. It is not enough—that lovely white body painted there in the pool—but it is something, and something is better than utter loneliness. It talks when I talk; it is sad when I am sad; it comforts me with its sympathy; it says, “Do not be downhearted, you poor friendless girl; I will be your friend.” It is a good friend to me, and my only one; it is my sister.

That first time that she forsook me! ah, I shall never forget that—never, never. My heart was lead in my body! I said, “She was all I had, and now she is gone!” In my despair I said, “Break, my heart; I cannot bear my life any more!” and hid my face in my hands, and there was no solace for me. And when I took them away, after a little, there she was again, white and shining and beautiful, and I sprang into her arms!

That was perfect happiness; I had known happiness before, but it was not like this, which was ecstasy. I never doubted her afterwards. Sometimes she stayed away—maybe an hour, maybe almost the whole day, but I waited and did not doubt; I said, “She is busy, or she is gone a journey, but she will come.” And it was so: she always did. At night she would not come if it was dark, for she was a timid little thing; but if there was a moon she would come. I am not afraid of the dark, but she is younger than I am; she was born after I was. Many and many are the visits I have paid her; she is my comfort and my refuge when my life is hard—and it is mainly that.

Tuesday.—All the morning I was at work improving the estate; and I purposely kept away from him in the hope that he would get lonely and come. But he did not. At noon I stopped for the day and took my recreation by flitting all about with the bees and the butterflies and revelling in the flowers, those beautiful creatures that catch the smile of God out of the sky and preserve it! I gathered them, and made them into wreaths and garlands and clothed myself in them while I ate my luncheon—apples, of course; then I sat in the shade and wished and waited. But he did not come.

But no matter. Nothing would have come of it, for he does not care for flowers. He calls them rubbish, and cannot tell one from another, and thinks it is superior to feel like that. He does not care for me, he does not care for flowers, he does not care for the painted sky at eventide—is there anything he does care for, except building shacks to coop himself up in from the good clean rain, and thumping the melons, and sampling the grapes, and fingering the fruit on the trees, to see how those properties are coming along?

I laid a dry stick on the ground and tried to bore a hole in it with another one, in order to carry out a scheme that I had, and soon I got an awful fright. A thin, transparent bluish film rose out of the hole, and I dropped everything and ran! I thought it was a spirit, and I was so frightened! But I looked back, and it was not coming; so I leaned against a rock and rested and panted, and let my limbs go on trembling until they got steady again; then I crept warily back, alert, watching, and ready to fly if there was occasion; and when I was come near, I parted the branches of a rose-bush and peeped through—wishing the man was about, I was looking so cunning and pretty—but the sprite was gone. I went there, and there was a pinch of delicate pink dust in the hole. I put my finger in, to feel it, and said ouch! and took it out again. It was a cruel pain. I put my finger in my mouth; and by standing first on one foot and then the other, and grunting, I presently eased my misery; then I was full of interest, and began to examine. I was curious to know what the pink dust was. Suddenly the name of it occurred to me, though I had never heard of it before. It was fire! I was as certain of it as a person could be of anything in the world. So without hesitation I named it that—fire. I had created something that didn’t exist before; I had added a new thing to the world’s uncountable properties; I realized this, and was proud of my achievement, and was going to run and find him and tell him about it, thinking to raise myself in his esteem—but I reflected, and did not do it. No—he would not care for it. He would ask what it was good for, and what could I answer? for if it was not good for something, but only beautiful, merely beautiful—So I sighed, and did not go. For it wasn’t good for anything; it could not build a shack, it could not improve melons, it could not hurry a fruit crop; it was useless, it was a foolishness and a vanity; he would despise it and say cutting words. But to me it was not despicable; I said, “Oh, you fire, I love you, you dainty pink creature, for you are beautiful—and that is enough!” and was going to gather it to my breast. But refrained. Then I made another maxim out of my own head, though it was so nearly like the first one that I was afraid it was only a plagiarism: “The burnt Experiment shuns the fire.”

I wrought again; and when I had made a good deal of fire-dust I emptied it into a handful of dry brown grass, intending to carry it home and keep it always and play with it; but the wind struck it and it sprayed up and spat out at me fiercely, and I dropped it and ran. When I looked back the blue spirit was towering up and stretching and rolling away like a cloud, and instantly I thought of the name of it—smoke!—though, upon my word, I had never heard of smoke before. Soon, brilliant yellow-and-red flares shot up through the smoke, and I named them in an instant—flames!—and I was right, too, though these were the very first flames that had ever been in the world. They climbed the trees, they flashed splendidly in and out of the vast and increasing volume of tumbling smoke, and I had to clap my hands and laugh and dance in my rapture, it was so new and strange and so wonderful and so beautiful! He came running, and stopped and gazed, and said not a word for many minutes. Then he asked what it was. Ah, it was too bad that he should ask such a direct question. I had to answer it, of course, and I did. I said it was fire. If it annoyed him that I should know and he must ask, that was not my fault; I had no desire to annoy him. After a pause he asked:

“How did it come?” Another direct question, and it also had to have a direct answer.

“I made it.”

The fire was travelling farther and farther off. He went to the edge of the burned place and stood looking down, and said:.

“What are these?”

“Fire-coals.”

He picked up one to examine it, but changed his mind and put it down again. Then he went away. Nothing interests him.

But I was interested. There were ashes, gray and soft and delicate and pretty—I knew what they were at once. And the embers; I knew the embers, too. I found my apples, and raked them out, and was glad; for I am very young and my appetite is active. But I was disappointed; they were all burst open and spoiled. Spoiled apparently; but it was not so; they were better than raw ones. Fire is beautiful; some day it will be useful, I think

Friday.—I saw him again, for a moment, last Monday at nightfall, but only for a moment. I was hoping he would praise me for trying to improve the estate, for I had meant well and had worked hard. But he was not pleased, and turned away and left me. He was also displeased on another account: I tried once more to persuade him to stop going over the Falls. That was because the fire had revealed to me a new passion—quite new, and distinctly different from love, grief, and those others which I had already discovered—fear. And it is horrible!—I wish I had never discovered it; it gives me dark moments, it spoils my happiness, it makes me shiver and tremble and shudder. But I could not persuade him, for he has not discovered fear yet, and so he could not understand me.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

XVIII. L’Emailleuse

Un beau matin, le poète Amilcar enfonça sur sa tête son chapeau noir, un chapeau célèbre, d’une hauteur prodigieuse, d’une envergure insolite, plein de plats et de méplats, de rides et de bosses, de crevasses et de meurtrissures, mit dans une poche, sise au-dessous de sa mamelle gauche, une pipe en terre à long col et s’achemina vers le nouveau domicile qu’avait choisi un sien ami, le peintre José.

Il le trouva couché sur un éboulement de coussins, l’oeil morne, la figure blafarde.

—Tu es malade, lui dit-il.

—Non.

—Tu vas bien alors?

—Non.

—Tu es amoureux

—Oui.

—Patatras! et de qui? bon Dieu!

—D’une Chinoise.

—D’une Chinoise? tu es amoureux d’une Chinoise!

—Je suis amoureux d’une Chinoise.

Amilcar s’affaissa sur l’unique chaise qui meublait la chambre.

—Mais enfin, clama-t-il lorsqu’il fut revenu de sa stupeur, où l’as-tu rencontrée, cette Chinoise?

—Ici, à deux pas, là, derrière ce mur. Ecoute, je l’ai suivie un soir, j’ai su qu’elle demeurait ici avec son père, j’ai loué la chambre contiguë à la sienne, je lui ai écrit une lettre à laquelle elle n’a pas encore répondu, mais j’ai appris par la concierge son nom: elle s’appelle Ophélie. Oh! si tu savais comme elle est belle, cria-t-il en se levant; un teint d’orange mûrie, une bouche aussi rose que la chair des pastèques, des yeux noirs comme du jayet!

Amilcar lui serra la main d’un air désolé et s’en fut annoncer a ses amis que José était devenu fou.

A peine eut-il franchi la porte, que celui-ci fit dans la muraille un petit trou avec une vrille et se mit aux aguets, espérant bien voir sa douce déité. Il était huit heures du matin, rien ne bougeait dans la chambre voisine; il commençait à se désespérer quand un bâillement se fit entendre, un bruit retentit, le bruit d’un corps sautant a terre, et une jeune fille parut dans le cercle que son oeil pouvait embrasser. Il reçut un grand coup dans l’estomac et manqua défaillir. C’était elle et ce n’était pas elle; c’était une Française qui ressemblait, autant que peut ressembler une Française à une Chinoise, à la fille jaune dont le regard l’avait bouleversé. Et pourtant c’était bien le même oeil câlin et profond, mais la peau était terne et pâle, le rouge de la bouche s’était amorti; enfin, c’était une Européenne! Il descendit l’escalier précipitamment. «Ophélie a donc une soeur? dit-il à la concierge. —Non. —Mais elle n’est pas Chinoise alors? —La concierge éclata de rire. «Comment, pas Chinoise! ah çà! est-ce que j’ai une figure comme elle, moi qui ne suis pas née en Chine?» poursuivit le vieux monstre en mirant sa peau ridée dans un miroir trouble. José restait debout, effaré, stupide, quand une voix forte fit tressaillir les carreaux de la loge. «Mlle Ophélie est là?» José se retourna et vit en face de lui, non une figure de vieux reître, comme semblait l’indiquer la voix, mais celle d’une vieille femme, gonflée comme une outre, le nez chevauché par d’énormes besicles, la bouche dessinant dans la bouffissure des chairs de capricieux zigzags. Sur la réponse affirmative de la portière, cette femme monta, et José s’aperçut qu’elle tenait à la main une boîte en toile cirée. Il s’élança sur ses pas, mais la porte se referma sur elle; alors il se précipita dans sa chambre et colla son oeil contre le trou qu’il avait percé dans la cloison.

Ophélie s’assit, lui tournant le dos, devant une grande glace, et la femme, s’étant débarrassée de son tartan, ouvrit sa valise et en tira un grand nombre de petites boites d’estompes et de brosses. Puis, soulevant la tête d’Ophélie comme si elle la voulait raser, elle étendit avec un petit pinceau une pâte d’un jaune rosé sur la figure de la jeune fille, brossa doucement la peau, pétrit un petit morceau de cire devant le feu, rectifia le nez, assortissant la teinte avec celle de la figure, soudant avec un blanc laiteux le morceau artificiel du nez avec la chair du véritable; enfin elle prit ses estompes, les frotta sur la poudre des boites, étendit une légère couche de bleu pâle sous l’oeil noir qui se creusa et s’allongea vers les tempes. La toilette terminée, elle se recula à distance pour mieux juger de l’effet, dodelina la tête, revint vers son pastel qu’elle retoucha, resserra ses outils et, après avoir pressé la main d’Ophélie sortit en reniflant.

José était inerte, les bras lui en étaient tombés. Eh quoi! c’était un tableau qu’il avait aimé, un déguisement de bal masqué! Il finit cependant par reprendre ses sens et courut à la recherche de l’émailleuse. Elle était déjà au bout de la rue; il bouscula tout le monde, courut à travers les voitures et la rejoignit enfin. «Que signifie tout cela? cria-t-il; qui êtes-vous? pourquoi la transfigurez-vous en Chinoise? —Je suis émailleuse, mon cher Monsieur; voici ma carte; toute à votre service si vous avez besoin de moi. —Eh! il s’agit bien de votre carte! cria le peintre tout haletant; je vous en prie, expliquez-moi le motif de cette comédie.

—Oh! pour ça, si vous y tenez et si vous êtes assez honnête pour offrir à une pauvre vieille artiste un petit verre de ratafia, je vous dirai tout au long pourquoi, tous les matins, je viens peindre Ophélie.

—Allons, dit José, en la poussant dans un cabaret et en l’installant sur une chaise, dans un cabinet particulier, voici du ratafia, parlez.

—Je vous dirai tout d’abord, commença-t-elle, que je suis émailleuse fort habile; au reste, vous avez pu voir… Ah! çà mais, à propos, comment avez-vous vu? … —Peu importe, cela ne peut vous regarder, continuez. —Eh bien! je vous disais donc que j’étais une émailleuse fort habile et que si jamais vous… —Au fait! au fait! cria José furieux. —Ne vous emportez pas, voyons, là, vous savez bien que la colère… —Mais tu me fais bouillir, misérable! hurla le peintre qui se sentait de furieuses envies de l’étrangler, parleras-tu? —Ah! mais pardon, jeune homme, je ne sais pourquoi vous vous permettez de me tutoyer et de m’appeler misérable; je vous préviens tout d’abord que si… —Ah! mon Dieu, gémit le pauvre garçon en frappant du pied il y a de quoi devenir fou.

—Voyons, jeune homme, taisez-vous et je continue; surtout ne m’interrompez pas, ajouta-t-elle en dégustant son verre. Je vous disais donc… —Que vous étiez une émailleuse fort habile; oui, je le sais, j’ai votre carte; voyons, passons: pourquoi Ophélie se fait-elle peindre en Chinoise?

—Mon Dieu, que vous êtes impatient! Connaissez-vous l’homme qui habite avec elle? —Son père? —Non. D’abord, ce n’est pas son vrai père, mais bien son père adoptif. —C’est un Chinois? —Pas le moins du monde; il est Chinois comme vous et moi; mais il a vécu longtemps dans le Thibet et y a fait fortune. Cet homme, qui est un brave et honnête homme, je vous avouerai même qu’il ressemble un peu à mon défunt qui… —Oui, oui, vous me l’avez déjà dit. —Bah! dit la femme, en le regardant avec stupeur, je vous ai parlé d’Isidore? —De grâce, laissons Isidore dans sa tombe, buvez votre ratafia et continuez. —Tiens, c’est drôle! il me semble pourtant que… Enfin, peu importe, je vous disais donc que c’était un brave et digne homme. Il se maria là-bas avec une Chinoise qui l’a planté là au bout d’un mois de mariage. Il faillit devenir fou, car il aimait sa femme, et ses amis durent le faire revenir en France au plus vite. Il se rétablit peu à peu et, un soir, il a trouvé dans la rue, défaillante de froid et de faim, prête à se livrer pour un morceau de pain, une jeune fille dont les yeux avaient la même expression que ceux de sa femme. Elle lui ressemblait même comme grandeur et comme taille; c’est alors qu’il lui a proposé de lui laisser toute sa fortune si elle consentait à se laisser peindre tous les matins. Il est venu me trouver, et chaque jour, à huit heures, je la déguise; il arrive à dix heures et déjeune avec elle. Jamais plus, depuis le jour où il l’a recueillie, il ne l’a vue telle qu’elle est réellement. Voilà; maintenant, je me sauve, car j’ai de l’ouvrage. Bonsoir, Monsieur.

Il resta abruti, inerte, sentant ses idées lui échapper. Il rentra chez lui dans un état à faire pitié.

Amilcar arriva sur ces entrefaites, suivi d’un de ses amis qui était médecin. Ils eurent toutes les peines du monde à faire sortir de sa torpeur le malheureux José, qui ne parlait rien moins que de s’aller jeter dans la Seine.

—Ce n’est, ma foi! pas la peine de se noyer pour si peu, dit derrière eux une petite voix aigrelette; je suis Ophélie, mon gros père, et ne suis point si cruelle que je vous laisse mourir d’amour pour moi. Profitons, si vous voulez, de l’absence du vieux, pour aller visiter les magasins de soieries. J’ai justement envie d’une robe; je vous autoriserai à me l’offrir. —Oh! non, cria le peintre, profondément révolté par cette espèce de marché, je suis guéri à tout jamais de mon amour.

Entendre de telles paroles sortir de la bouche de sa bien-aimée ou recevoir sur la tête une douche d’eau froide, l’effet est le même, observa le poète Amilcar, qui dégringola les escaliers et, chemin faisant, rima immédiatement un sonnet qu’il envoya le lendemain à la belle enfant, sous ce titre quelque peu satirique:

O Fleur de nénuphar!

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Archive G-H, Huysmans, J.-K.

.jpg)

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

In Memoriam

Olivia Susan Clemens

Died August 18, 1896; aged 24

In a fair valley—oh, how long ago, how long ago!

Where all the broad expanse was clothed in vines

And fruitful fields and meadows starred with flowers,

And clear streams wandered at their idle will,

And still lakes slept, their burnished surfaces

A dream of painted clouds, and soft airs

Went whispering with odorous breath,

And all was peace—in that fair vale,

Shut from the troubled world, a nameless hamlet drowsed.

Hard by, apart, a temple stood;

And strangers from the outer world

Passing, noted it with tired eyes,

And seeing, saw it not:

A glimpse of its fair form—an answering momentary thrill—

And they passed on, careless and unaware.

They could not know the cunning of its make;

They could not know the secret shut up in its heart;

Only the dwellers of the hamlet knew:

They knew that what seemed brass was gold;

What marble seemed, was ivory;

The glories that enriched the milky surfaces—

The trailing vines, and interwoven flowers,

And tropic birds awing, clothed all in tinted fire—

They knew for what they were, not what they seemed:

Encrustings all of gems, not perishable splendors of the brush.

They knew the secret spot where one must stand—

They knew the surest hour, the proper slant of sun—

To gather in, unmarred, undimmed,

The vision of the fane in all its fairy grace,

A fainting dream against the opal sky.

And more than this. They knew

That in the temple’s inmost place a spirit dwelt,

Made all of light!

For glimpses of it they had caught

Beyond the curtains when the priests

That served the altar came and went.

All loved that light and held it dear

That had this partial grace;

But the adoring priests alone who lived

By day and night submerged in its immortal glow

Knew all its power and depth, and could appraise the loss

If it should fade and fail and come no more.

All this was long ago—so long ago!

The light burned on; and they that worship’d it,

And they that caught its flash at intervals and held it dear,

Contented lived in its secure possession. Ah,

How long ago it was!

And then when they

Were nothing fearing, and God’s peace was in the air,

And none was prophesying harm—

The vast disaster fell:

Where stood the temple when the sun went down,

Was vacant desert when it rose again!

Ah, yes! ’Tis ages since it chanced!

So long ago it was,

That from the memory of the hamlet-folk the Light has passed—

They scarce believing, now, that once it was,

Or, if believing, yet not missing it,

And reconciled to have it gone.

Not so the priests! Oh, not so

The stricken ones that served it day and night,

Adoring it, abiding in the healing of its peace:

They stand, yet, where erst they stood

Speechless in that dim morning long ago;

And still they gaze, as then they gazed,

And murmur, “It will come again;

It knows our pain—it knows—it knows—

Ah, surely it will come again.”

S.L.C.

Lake Lucerne, August 18, 1897.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories & poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 56:

Er zyn dichters die verzen maken.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature