Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

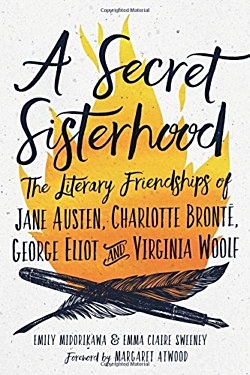

Male literary friendships are the stuff of legend; think Byron and Shelley, Fitzgerald and Hemingway.  But the world’s best-loved female authors are usually mythologized as solitary eccentrics or isolated geniuses.

But the world’s best-loved female authors are usually mythologized as solitary eccentrics or isolated geniuses.

Coauthors and real-life friends Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney prove this wrong, thanks to their discovery of a wealth of surprising collaborations: the friendship between Jane Austen and one of the family servants, playwright Anne Sharp; the daring feminist author Mary Taylor, who shaped the work of Charlotte Bronte; the transatlantic friendship of the seemingly aloof George Eliot and Harriet Beecher Stowe; and Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield, most often portrayed as bitter foes, but who, in fact, enjoyed a complex friendship fired by an underlying erotic charge.

Through letters and diaries that have never been published before, A Secret Sisterhood resurrects these forgotten stories of female friendships. They were sometimes scandalous and volatile, sometimes supportive and inspiring, but always–until now–tantalizingly consigned to the shadows.

Emily Midorikawa’s work has been published in the Daily Telegraph, the Independent on Sunday, and the Times. She is a winner of the Lucy Cavendish Fiction Prize and was a runner-up in the SI Leeds Literary Prize (judged by Margaret Busby) and the Yeovil Literary Prize (judged by Tracy Chevalier). She has a history degree from University College London, and is a graduate of the University of East Anglia’s creative writing masters program. She now teaches at New York University–London.

A Secret Sisterhood:

The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf

by Emily Midorikawa (Author), Emma Claire Sweeney (Author), Margaret Atwood (Foreword)

Hardcover, 352 pages

Publication: October 2017

by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

ISBN 054488373X

(ISBN13: 9780544883734)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane, Brontë, Anne, Emily & Charlotte, Eliot, George, Mansfield, Katherine, Mansfield, Katherine, Virginia Woolf, Woolf, Virginia

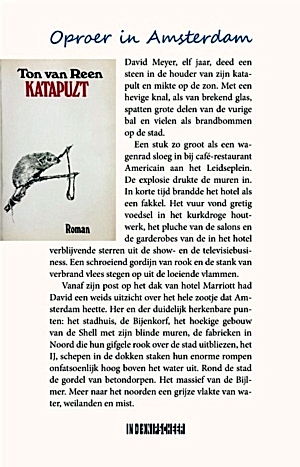

In de tijd waarin de roman Katapult, Oproer in Amsterdam speelt, de jaren zeventig van de vorige eeuw, was er nog hoop, ook al toont het verhaal niet het Amsterdam van de glamour maar het Amsterdam dat aan de rand staat van de verloedering.

Het is het verhaal van een dag uit het leven van een kleine groep mensen, een familie en hun vrienden, die in een grote stad toch in een uiterst kleine kring blijken te leven. Het lijkt dat ze ver staan van de boze en wonderlijke rampen die zich in de stad voltrekken en die ze niet kunnen benoemen, maar feitelijk ondervinden ze alle gebeurtenissen aan hun lijf.

Het is het verhaal van een dag uit het leven van een kleine groep mensen, een familie en hun vrienden, die in een grote stad toch in een uiterst kleine kring blijken te leven. Het lijkt dat ze ver staan van de boze en wonderlijke rampen die zich in de stad voltrekken en die ze niet kunnen benoemen, maar feitelijk ondervinden ze alle gebeurtenissen aan hun lijf.

Wat er in Katapult gebeurt, speelt zich alleen af in zwarte sprookjes, maar vaak hebben sprookjes meer met de werkelijkheid gemeen dan de exacte verslagen van gebeurtenissen. Wie denkt dat het onmogelijk is om met een katapult een brandende scherf van de zon te schieten, om zo hotel-restaurant Americain in de fik te zetten, moet dit boek maar niet lezen.

Katapult is vijfenveertig jaar geleden geschreven. Veel in Amsterdam lijkt nu nog hetzelfde, maar dat is schijn. Wie met dit boek door de stad loopt en de sporen zoekt van het Amsterdam van toen, ziet dat de mooie gevels er nog zijn en worden gefotografeerd door hordes toeristen uit de hele wereld, maar ook dat achter de fraaie gevels heel veel is weggehaald.

Nu zijn er supermarkten gevestigd en kantoren van advocaten, multinationals en brievenbusmaatschappijen die de stad en Nederland misbruiken om belasting te ontduiken. De gezinnen zoals die van Albert Meyer zijn grotendeels verdreven naar de Bijlmer, Purmerend en Almere.

Ook café De Engelbewaarder, aan de Kloveniersburgwal is er niet meer. Kastelein Bas, in wie de toenmalige uitbater en boekenliefhebber Bas Lubberhuizen herkend kan worden, leeft nog, maar de redacteuren van Vrij Nederland die er dagelijks hun kelkjes leeg dronken, zoals Martin van Amerongen en Joop van Tijn, zijn al jaren heen.

Ook café De Engelbewaarder, aan de Kloveniersburgwal is er niet meer. Kastelein Bas, in wie de toenmalige uitbater en boekenliefhebber Bas Lubberhuizen herkend kan worden, leeft nog, maar de redacteuren van Vrij Nederland die er dagelijks hun kelkjes leeg dronken, zoals Martin van Amerongen en Joop van Tijn, zijn al jaren heen.

Net als Ischa Meier die er vaak kwam met zijn vrouwen, minnaressen en favoriete hoertjes en een zak vol boeken waarvan hij de flapteksten las. Ook stamklant Robert Jasper Grootveld, die model stond voor Crazy Horse is er niet meer, net als Simon Vinkenoog, de magiër van het vrije woord. Wel zijn gelijkgestemde filosofen als Roel van Duijn en Luud Schimmelpennink nog onder ons, maar hun ideeën worden nauwelijks nog begrepen.

In de gevoelswereld van schrijver Ton van Reen spelen de zelfgenoegzame leden van de georganiseerde samenleving een uiterst sinistere rol. Wreedheid, vreemdelingenhaat en bloeddorst liggen achter hun oppervlakkige en zo fatsoenlijk lijkende gedrag voortdurend op de loer.

De helden van Ton van Reen behoren zonder uitzondering tot de kwetsbaren en de slachtoffers: eenzame kinderen, hoeren, landlopers, kermisgasten en zonderlingen, mensen die echter een warmer hart hebben dan de directeuren van de Rabobank en de Tweede Kamerleden van de VVD.

Over de boeken van Ton van Reen schreef Aad Nuis in de Haagse Post: ‘Hij schrijft eigenlijk steeds sprookjes, waarbij de toon onverhoeds kan omslaan van Andersen op zijn charmantst in Grimm op zijn gruwelijkst.’ Reinjan Mulder schreef in NRC-Handelsblad: ‘Het proza van Ton van Reen is mooi als poëzie.’ En Gerrit Krol schreef in dezelfde krant: ‘Ton van Reen schrijft leerboeken voor schrijvers.’

Ton van Reen

Katapult

Oproer in Amsterdam

Roman

Gebrocheerd in omslag met flappen,

148 blz., € 14,50

ISBN 978 90 6265 978 4

oktober 2017

Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer

# Meer info op website Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, - Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, David van Reen, David van Reen Photos, PRESS & PUBLISHING, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van

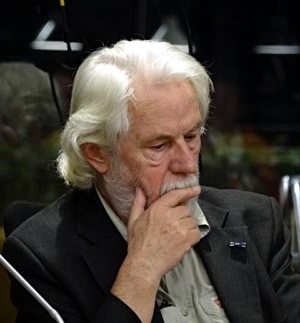

Ton van Reen lanceert zijn nieuwste roman Dochters op vrijdag 3 november 2017 in het Wereldpaviljoen te Steyl

Het boek speelt grotendeels in Nederland, Duitsland en Zwitserland, maar het gaat vooral over Afrika.

Op de vlucht voor zijn verleden is de hoofdpersoon er gaan werken als correspondent voor De Volkskrant. Op de reis naar de bruiloft van zijn dochter in Zwitserland raakt hij in gesprek met een jonge vrouw. Voor beiden wordt het een louterende ontmoeting.

Peter Winkels zal Ton van Reen interviewen over zijn nieuwe boek en zijn levenslange band met Afrika. Al in de jaren zeventig was Ton initiatiefnemer en uitgever van de Afrikaanse Bibliotheek. Ook schreef hij talloze artikelen over Afrika in kranten als De Volkskrant. Het boek is ter plekke te koop.

Het boek wordt gepresenteerd op vrijdag 3 november, tijdens een gevarieerde avond van de Stichting Lalibela in het Wereldpaviljoen te Steyl-Tegelen. Tijdens de avond is er aandacht voor de stichting die tal van sociale projecten uitvoert in de gelijknamige plaats. De Stichting Lalibela is negentien jaar geleden opgericht door Ton van Reen en zijn twee jaar geleden overleden zoon David. (David van Reen 1969 – 2015)

Het boek wordt gepresenteerd op vrijdag 3 november, tijdens een gevarieerde avond van de Stichting Lalibela in het Wereldpaviljoen te Steyl-Tegelen. Tijdens de avond is er aandacht voor de stichting die tal van sociale projecten uitvoert in de gelijknamige plaats. De Stichting Lalibela is negentien jaar geleden opgericht door Ton van Reen en zijn twee jaar geleden overleden zoon David. (David van Reen 1969 – 2015)

Bestuurslid Marc van der Sterren zal vertellen over zijn projecten rond kleinschalige landbouw in Afrika.

De film over het leven en het werk van David in Ethiopië, gemaakt door Marijn Poels voor L1-tv voor het programma Limburg helpt, zal worden vertoond. De presentaties worden omlijst door de muzikale inbreng van de Syrische groep AROA AND FRIENDS.

Vrijdag 3 november 2017

Tijd: 20.00 tot 22.30

Inloop vanaf 19.30. Gratis entree

Wereldpaviljoen

Sint Michaëlstraat 6a

5935 BL Steyl

D O C H T E R S

D O C H T E R S

Lennert Rosenberg, 59 jaar, journalist in Afrika voor de Volkskrant, reist met de nachttrein naar Zwitserland voor de bruiloft van zijn dochter Miriam. Aan het begin van de reis ontmoet hij Nena, een jonge vrouw, op weg naar haar ouders in Zwitserland.

Al vlug blijkt dat ze belangstelling hebben voor dezelfde dingen. Ondanks het grote leeftijdsverschil begrijpen ze elkaar.

Door urenlang oponthoud, er is iemand onder de trein gelopen, verkennen ze het nachtelijke Keulen. Als de trein na middernacht vertrekt, komt hij niet meer op tijd aan in Freiburg voor de aansluitende trein naar Bazel. Omdat ze lang moeten wachten, besluiten ze een dag in Freiburg te blijven, de stad waar de roots van Nena’s familie liggen.

Speelde Lennert even met het idee dat een verhouding met haar mogelijk zou zijn, nog net op tijd begrijpt hij dat zij geen minnaar zoekt, maar iemand die haar begrijpt. Doordat hij na zijn scheiding van zijn dochter Miriam is vervreemd, lijkt hij in Nena de dochter te vinden die hij heeft gemist. En zij vindt de vertrouwdheid van de vader die ze kwijt is.

Langzaam ontvouwt zich het levensverhaal van haar familie die in de oorlog naar Zwitserland is gevlucht. En het verhaal van haar vader die zijn best doet zijn Joodse verleden te verhullen en probeert een authentieke Zwitser te zijn.

Door haar verhalen gaan zijn ogen open voor zijn eigen geschiedenis die hij is ontvlucht door zich in Afrika te vestigen.

Hij viel in slaap en droomde dat hij een jongen was die samen met een man een lange weg afliep. Beiden waren ze naakt, maar de man droeg een rugzak.

‘Wat zit er in die rugzak?’ vroeg hij.

‘Mijn herinneringen,’ zei de man. ‘Later zijn ze voor jou.’

‘Kan ik dat dan allemaal onthouden?’

‘Je moet wel, zeker als je wilt weten wie je zelf bent. Je weet toch dat ik je vader ben?’

Toen pas herkende hij de man die hij zo vaak op foto’s had gezien.

Plotseling liep zijn vader naar de rand van een ravijn, gooide hem de rugzak toe en sprong naar beneden.

‘Ik wil hem niet!’ riep hij. ‘Kom terug!’

Hij durfde de zak niet op te rapen. Er kwam een spelend kind aan. Het opende de zak.

Ton van Reen schreef onder meer romans, kinder- en jeugdboeken en journalistiek werk, vaak over Afrika, in kranten zoals de Volkskrant, de GPD-kranten, en in tijdschriften.

Een aantal verhalen over de cultuurshock in Afrika werden gebundeld in WEENSE WALSEN IN MOMBASA. Ook schreef hij de novelle EEN OCHTEND IN CAIRO, een inleiding bij het werk van de Egyptische Nobelprijswinnaar Naguib Mahfoez.

Presentatie 3 november 2017

Wereldpaviljoen Steyl

Ton van Reen

Dochters

Nederland – Afrika

Roman

Gebrocheerd in omslag met flappen,

340 blz.

€ 19,50

Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer

ISBN 978 90 6265 963 0

# Meer info op website Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, David van Reen, David van Reen Photos, PRESS & PUBLISHING, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

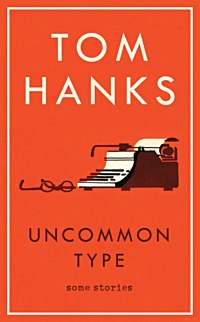

A collection of seventeen wonderful short stories showing that two-time Oscar winner Tom Hanks is as talented a writer as he is an actor.

A gentle Eastern European immigrant arrives in New York City after his family and his life have been torn apart by his country’s civil war.

A gentle Eastern European immigrant arrives in New York City after his family and his life have been torn apart by his country’s civil war.

A man who loves to bowl rolls a perfect game – and then another and then another and then many more in a row until he winds up ESPN’s newest celebrity, and he must decide if the combination of perfection and celebrity has ruined the thing he loves.

An eccentric billionaire and his faithful executive assistant venture into America looking for acquisitions and discover a down and out motel, romance and a bit of real life.

These are just some of the tales Tom Hanks tells in this first collection of his short stories. They are surprising, intelligent, heart-warming, and, for the millions and millions of Tom Hanks fans, an absolute must-have.

Tom Hanks has been an actor, screenwriter, director and through Playtone, a producer. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. This is his first collection of fiction.

Publisher: Cornerstone

ISBN: 9781785151514

Number of pages: 416

Weight: 620 g

Dimensions: 222 x 144 x 38 mm

October 2017

Hardback

£13.99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV

Neem me mee

Een vrachtwagen verdwijnt

verscholen achter een wolk smook

Kinderen rennen erachteraan

‘neem me mee,’ roepen ze

‘neem me mee!’

Steeds luider klinkt hun roep

tot hun keel dichtslaat van rook

en ze oplossen

in een wolk van stof

Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van

Mannen van Mobil

De mannen van Mobil houden Afrika in beweging

in hun vuilrode overalls met het Mobillogo

hurken ze bij de roestige benzinepomp

waarvan de teller op een getal zonder einde staat

ze kaarten en roken scherpe Sportsmansigaretten

De benzine wordt aangevoerd met ezels

die wie weet waar vandaan komen

in ieder geval van ver over de berg

geduldig schenken de mannen van Mobil

de zakken benzine over in plastic waterflessen

en betalen de ezeldrijver met beloftes

Ze kaarten verder en roken Sportsmansigaretten

rond de middag vallen ze in slaap

hurkend tegen de geblakerde benzinepomp

tot iemand de mannen van Mobil wakker maakt

iemand die een paar flessen benzine koopt

van de mannen die Afrika in beweging houden

Van het geld kopen ze white cap beer

en hurken weer neer bij de benzinepomp

ze delen de kaarten en roken Sportsmansigaretten

Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

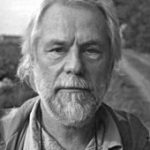

Pigeonholed in popular memory as a Jazz Age epicurean, a playboy, and an emblem of the Lost Generation, F. Scott Fitzgerald was at heart a moralist struck by the nation’s shifting mood and manners after World War I.

In Paradise Lost, David Brown contends that Fitzgerald’s deepest allegiances were to a fading antebellum world he associated with his father’s Chesapeake Bay roots. Yet as a midwesterner, an Irish Catholic, and a perpetually in-debt author, he felt like an outsider in the haute bourgeoisie haunts of Lake Forest, Princeton, and Hollywood—places that left an indelible mark on his worldview.

In Paradise Lost, David Brown contends that Fitzgerald’s deepest allegiances were to a fading antebellum world he associated with his father’s Chesapeake Bay roots. Yet as a midwesterner, an Irish Catholic, and a perpetually in-debt author, he felt like an outsider in the haute bourgeoisie haunts of Lake Forest, Princeton, and Hollywood—places that left an indelible mark on his worldview.

In this comprehensive biography, Brown reexamines Fitzgerald’s childhood, first loves, and difficult marriage to Zelda Sayre. He looks at Fitzgerald’s friendship with Hemingway, the golden years that culminated with Gatsby, and his increasing alcohol abuse and declining fortunes which coincided with Zelda’s institutionalization and the nation’s economic collapse.

Placing Fitzgerald in the company of Progressive intellectuals such as Charles Beard, Randolph Bourne, and Thorstein Veblen, Brown reveals Fitzgerald as a writer with an encompassing historical imagination not suggested by his reputation as “the chronicler of the Jazz Age.” His best novels, stories, and essays take the measure of both the immediate moment and the more distant rhythms of capital accumulation, immigration, and sexual politics that were moving America further away from its Protestant agrarian moorings. Fitzgerald wrote powerfully about change in America, Brown shows, because he saw it as the dominant theme in his own family history and life.

David S. Brown is Raffensperger Professor of History at Elizabethtown College.

“[An] incisive biography.”—The New Yorker

“Paradise Lost accomplishes much in its aim to contextualize Fitzgerald within both American historical and literary historical parameters. This new biography manages to get past the trappings of Fitzgerald’s boozy flapper-era persona and to credit his talent for taking the pulse of the America in which he lived.”—Christina Hunt Mahoney, The Irish Times

Paradise Lost

A Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald

David S. Brown

424 pag. – 2017

Harvard University Press

Belknap Press

Isbn 9780674504820

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, Fitzgerald, F. Scott

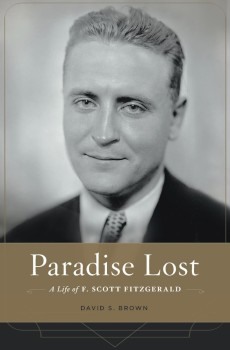

Flood

Goldbrown upon the sated flood

The rockvine clusters lift and sway;

Vast wings above the lambent waters brood

Of sullen day.

A waste of waters ruthlessly

Sways and uplifts its weedy mane

Where brooding day stares down upon the sea

In dull disdain.

Uplift and sway, O golden vine,

Your clustered fruits to love’s full flood,

Lambent and vast and ruthless as is thine

Incertitude!

James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

Flood

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

Ton van Reen

Het gras is van hem

Alle gras dat hij ziet is van hem

alle gras waar zijn oog op valt eigent hij zich toe

het gras tussen de stenen aan zijn voeten

het gras dat van steen naar steen kruipt

verder en verder

zo ver zijn oog reikt is alle gras van hem

Alles neemt hij

de hele grazige wereld die hij voor zich ziet

alle gras binnen zijn blikveld is van hem

Waar hij is, waar hij gaat is het gras van hem

hij hoort het zachte zuchten van zijn gras

Hij ruikt het ochtendgras

bewasemd door dauw

het groene gras dat zijn oog overweldigt

Ton van Reen: Het gras is van hem

Uit: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Natural history, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

The Invisible Girl

The Invisible Girl

by Mary Shelley

This slender narrative has no pretensions o the regularity of a story, or the development of situations and feelings; it is but a slight sketch, delivered nearly as it was narrated to me by one of the humblest of the actors concerned: nor will I spin out a circumstance interesting principally from its singularity and truth, but narrate, as concisely as I can, how I was surprised on visiting what seemed a ruined tower, crowning a bleak promontory overhanging the sea, that flows between Wales and Ireland, to find that though the exterior preserved all the savage rudeness that betokened many a war with the elements, the interior was fitted up somewhat in the guise of a summer-house, for it was too small to deserve any other name.

It consisted but of the ground-floor, which served as an entrance, and one room above, which was reached by a staircase made out of the thickness of the wall. This chamber was floored and carpeted, decorated with elegant furniture; and, above all, to attract the attention and excite curiosity, there hung over the chimney-piece — for to preserve the apartment from damp a fire-place had been built evidently since it had assumed a guise so dissimilar to the object of its construction — a picture simply painted in water-colours, which seemed more than any part of the adornments of the room to be at war with the rudeness of the building, the solitude in which it was placed, and the desolation of the surrounding scenery. This drawing represented a lovely girl in the very pride and bloom of youth; her dress was simple, in the fashion of the day — (remember, reader, I write at the beginning of the eighteenth century), her countenance was embellished by a look of mingled innocence and intelligence, to which was added the imprint of serenity of soul and natural cheerfulness. She was reading one of those folio romances which have so long been the delight of the enthusiastic and young; her mandoline was at her feet — her parroquet perched on a huge mirror near her; the arrangement of furniture and hangings gave token of a luxurious dwelling, and her attire also evidently that of home and privacy, yet bore with it an appearance of ease and girlish ornament, as if she wished to please. Beneath this picture was inscribed in golden letters, “The Invisible Girl.”

Rambling about a country nearly uninhabited, having lost my way, and being overtaken by a shower, I had lighted on this dreary looking tenement, which seemed to rock in the blast, and to be hung up there as the very symbol of desolation. I was gazing wistfully and cursing inwardly my stars which led me to a ruin that could afford no shelter, though the storm began to pelt more seriously than before, when I saw an old woman’s head popped out from a kind of loophole, and as suddenly withdrawn: — a minute after a feminine voice called to me from within, and penetrating a little brambly maze that skreened a door, which I had not before observed, so skilfully had the planter succeeded in concealing art with nature I found the good dame standing on the threshold and inviting me to take refuge within. “I had just come up from our cot hard by,” she said, “to look after the things, as I do every day, when the rain came on — will ye walk up till it is over?” I was about to observe that the cot hard by, at the venture of a few rain drops, was better than a ruined tower, and to ask my kind hostess whether “the things” were pigeons or crows that she was come to look after, when the matting of the floor and the carpeting of the staircase struck my eye. I was still more surprised when I saw the room above; and beyond all, the picture and its singular inscription, naming her invisible, whom the painter had coloured forth into very agreeable visibility, awakened my most lively curiosity: the result of this, of my.exceeding politeness towards the old woman, and her own natural garrulity, was a kind of garbled narrative which my imagination eked out, and future inquiries rectified, till it assumed the following form.

Some years before in the afternoon of a September day, which, though tolerably fair, gave many tokens of a tempestuous evening, a gentleman arrived at a little coast town about ten miles from this place; he expressed his desire to hire a boat to carry him to the town of about fifteen miles further on the coast. The menaces which the sky held forth made the fishermen loathe to venture, till at length two, one the father of a numerous family, bribed by the bountiful reward the stranger promised — the other, the son of my hostess, induced by youthful daring, agreed to undertake the voyage. The wind was fair, and they hoped to make good way before nightfall, and to get into port ere the rising of the storm. They pushed off with good cheer, at least the fishermen did; as for the stranger, the deep mourning which he wore was not half so black as the melancholy that wrapt his mind. He looked as if he had never smiled — as if some unutterable thought, dark as night and bitter as death, had built its nest within his bosom, and brooded therein eternally; he did not mention his name; but one of the villagers recognised him as Henry Vernon, the son of a baronet who possessed a mansion about three miles distant from the town for which be was bound. This mansion was almost abandoned by the family; but Henry had, in a romantic fit, visited it about three years before, and Sir Peter had been down there during the previous spring for about a couple of months.

The boat did not make so much way as was expected; the breeze failed them as they got out to sea, and they were fain with oar as well as sail, to try to weather the promontory that jutted out between them and the spot they desired to reach. They were yet far distant when the shifting wind began to exert its strength, and to blow with violent though unequal puffs. Night came on pitchy dark, and the howling waves rose and broke with frightful violence, menacing to overwhelm the tiny bark that dared resist their fury. They were forced to lower every sail, and take to their oars; one man was obliged to bale out the water, and Vernon himself took an oar, and rowing with desperate energy, equalled the force of the more practised boatmen. There had been much talk between the sailors before the tempest came on; now, except a brief command, all were silent. One thought of his wife and children, and silently cursed the caprice of the stranger that endangered in its effects, not only his life, but their welfare; the other feared less, for he was a daring lad, but he worked hard, and had no time for speech; while Vernon bitterly regretting the thoughtlessness which had made him cause others to share a peril, unimportant as far as he himself was concerned, now tried to cheer them with a voice full of animation and courage, and now pulled yet more strongly at the oar he held. The only person who did not seem wholly intent on the work he was about, was the man who baled; every now and then he gazed intently round, as if the sea held afar off, on its tumultuous waste, some object that he strained his eyes to discern. But all was blank, except as the crests of the high waves showed themselves, or far out on the verge of the horizon, a kind of lifting of the clouds betokened greater violence for the blast. At length he exclaimed — “Yes, I see it! — the larboard oar! — now! if we can make yonder light, we are saved!” Both the rowers instinctively turned their heads, — but cheerless darkness answered their gaze.

“You cannot see it,” cried their companion, ‘but we are nearing it; and, please God, we shall outlive this night.” Soon he took the oar from Vernon’s hand, who, quite exhausted, was failing in his strokes. He rose and looked for the beacon which promised them safety; — it glimmered with so faint a ray, that now he said, “I see it;” and again, “it is nothing:” still, as they made way, it dawned upon his sight, growing more steady and distinct as it beamed across the lurid waters,.which themselves be came smoother, so that safety seemed to arise from the bosom of the ocean under the influence of that flickering gleam.

“What beacon is it that helps us at our need?” asked Vernon, as the men, now able to manage their oars with greater ease, found breath to answer his question.

“A fairy one, I believe,” replied the elder sailor, “yet no less a true: it burns in an old tumble-down tower, built on the top of a rock which looks over the sea. We never saw it before this summer; and now each night it is to be seen, — at least when it is looked for, for we cannot see it from our village; — and it is such an out of the way place that no one has need to go near it, except through a chance like this. Some say it is burnt by witches, some say by smugglers; but this I know, two parties have been to search, and found nothing but the bare walls of the tower.

All is deserted by day, and dark by night; for no light was to be seen while we were there, though it burned sprightly enough when we were out at sea.

“I have heard say,” observed the younger sailor, “it is burnt by the ghost of a maiden who lost her sweetheart in these parts; he being wrecked, and his body found at the foot of the tower: she goes by the name among us of the ‘Invisible Girl.'”

The voyagers had now reached the landing-place at the foot of the tower. Vernon cast a glance upward, — the light was still burning. With some difficulty, struggling with the breakers, and blinded by night, they contrived to get their little bark to shore, and to draw her up on the beach:

they then scrambled up the precipitous pathway, overgrown by weeds and underwood, and, guided by the more experienced fishermen, they found the entrance to the tower, door or gate there was none, and all was dark as the tomb, and silent and almost as cold as death.

“This will never do,” said Vernon; “surely our hostess will show her light, if not herself, and guide our darkling steps by some sign of life and comfort.”

“We will get to the upper chamber,” said the sailor, “if I can but hit upon the broken down steps: but you will find no trace of the Invisible Girl nor her light either, I warrant.”

“Truly a romantic adventure of the most disagreeable kind,” muttered Vernon, as he stumbled over the unequal ground: “she of the beacon-light must be both ugly and old, or she would not be so peevish and inhospitable.”

With considerable difficulty, and, after divers knocks and bruises, the adventurers at length succeeded in reaching the upper story; but all was blank and bare, and they were fain to stretch themselves on the hard floor, when weariness, both of mind and body, conduced to steep their senses in sleep.

Long and sound were the slumbers of the mariners. Vernon but forgot himself for an hour; then, throwing off drowsiness, and finding his roughcouch uncongenial to repose, he got up and placed himself at the hole that served for a window, for glass there was none, and there being not even a rough bench, he leant his back against the embrasure, as the only rest he could find. He had forgotten his danger, the mysterious beacon, and its invisible guardian: his thoughts were occupied on the horrors of his own fate, and the unspeakable wretchedness that sat like a night-mare on his heart.

It would require a good-sized volume to relate the causes which had changed the once happy Vernon into the most woeful mourner that ever clung to the outer trappings of grief, as slight though cherished symbols of the wretchedness within. Henry was the only child of Sir Peter Vernon, and as much spoiled by his father’s idolatry as the old baronet’s violent and tyrannical temper would permit. A young orphan was educated in his father’s house, who in the same way was treated with generosity and kindness, and yet who lived in deep awe of Sir Peter’s authority, who was a widower; and these two children were all he had to exert his power over, or to whom.to extend his affection. Rosina was a cheerful-tempered girl, a little timid, and careful to avoid displeasing her protector; but so docile, so kind-hearted, and so affectionate, that she felt even less than Henry the discordant spirit of his parent. It is a tale often told; they were playmates and companions in childhood, and lovers in after days. Rosina was frightened to imagine that this secret affection, and the vows they pledged, might be disapproved of by Sir Peter. But sometimes she consoled herself by thinking that perhaps she was in reality her Henry’s destined bride, brought up with him under the design of their future union; and Henry, while he felt that this was not the case, resolved to wait only until he was of age to declare and accomplish his wishes in making the sweet Rosina his wife. Meanwhile he was careful to avoid premature discovery of his intentions, so to secure his beloved girl from persecution and insult. The old gentleman was very conveniently blind; he lived always in the country, and the lovers spent their lives together, unrebuked and uncontrolled. It was enough that Rosina played on her mandoline, and sang Sir Peter to sleep every day after dinner; she was the sole female in the house above the rank of a servant, and had her own way in the disposal of her time. Even when Sir Peter frowned, her innocent caresses and sweet voice were powerful to smooth the rough current of his temper. If ever human spirit lived in an earthly paradise, Rosina did at this time: her pure love was made happy by Henry’s constant presence; and the confidence they felt in each other, and the security with which they looked forward to the future, rendered their path one of roses under a cloudless sky. Sir Peter was the slight drawback that only rendered their tête — à — tête more delightful, and gave value to the sympathy they each bestowed on the other. All at once an ominous personage made its appearance in Vernon-Place, in the shape of a widow sister of Sir Peter, who, having succeeded in killing her husband and children with the effects of her vile temper, came, like a harpy, greedy for new prey, under her brother’s roof. She too soon detected the attachment of the unsuspicious pair. She made all speed to impart her discovery to her brother, and at once to restrain and inflame his rage. Through her contrivance Henry was suddenly despatched on his travels abroad, that the coast might be clear for the persecution of Rosina; and then the richest of the lovely girl’s many admirers, whom, under Sir Peter’s single reign, she was allowed, nay, almost commanded, to dismiss, so desirous was he of keeping her for his own comfort, was selected, and she was ordered to marry him. The scenes of violence to which she was now exposed, the bitter taunts of the odious Mrs. Bainbridge, and the reckless fury of Sir Peter, were the more frightful and overwhelming from their novelty. To all she could only oppose a silent, tearful, but immutable steadiness of purpose: no threats, no rage could extort from her more than a touching prayer that they would not hate her, because she could not obey.

“There must he something we don’t see under all this,” said Mrs. Bainbridge, “take my word for it, brother, — she corresponds secretly with Henry. Let us take her down to your seat in Wales, where she will have no pensioned beggars to assist her; and we shall see if her spirit be not bent to our purpose.”

Sir Peter consented, and they all three posted down to , — shire, and took up their abode in the solitary and dreary looking house before alluded to as belonging to the family. Here poor Rosina’s sufferings grew intolerable: — before, surrounded by well-known scenes, and in perpetual intercourse with kind and familiar faces, she had not despaired in the end of conquering by her patience the cruelty of her persecutors; — nor had she written to Henry, for his name had not been mentioned by his relatives, nor their attachment alluded to, and she felt an instinctive wish to escape the dangers about her without his being annoyed, or the sacred secret of her love being laid bare, and wronged by the vulgar abuse of his aunt or the bitter curses of his father. But when she was taken to Wales, and made a prisoner in her apartment, when the flinty.mountains about her seemed feebly to imitate the stony hearts she had to deal with, her courage began to fail. The only attendant permitted to approach her was Mrs. Bainbridge’s maid; and under the tutelage of her fiend-like mistress, this woman was used as a decoy to entice the poor prisoner into confidence, and then to be betrayed. The simple, kind-hearted Rosina was a facile dupe, and at last, in the excess of her despair, wrote to Henry, and gave the letter to this woman to be forwarded. The letter in itself would have softened marble; it did not speak of their mutual vows, it but asked him to intercede with his father, that he would restore her to the kind place she had formerly held in his affections, and cease from a cruelty that would destroy her. “For I may die,” wrote the hapless girl, “but marry another — never!” That single word, indeed, had sufficed to betray her secret, had it not been already discovered; as it was, it gave increased fury to Sir Peter, as his sister triumphantly pointed it out to him, for it need hardly be said that while the ink of the address was yet wet, and the seal still warm, Rosina’s letter was carried to this lady. The culprit was summoned before them; what ensued none could tell; for their own sakes the cruel pair tried to palliate their part. Voices were high, and the soft murmur of Rosina’s tone was lost in the howling of Sir Peter and the snarling of his sister. “Out of doors you shall go,” roared the old man; “under my roof you shall not spend another night.” And the words “infamous seductress,” and worse, such as had never met the poor girl’s ear before, were caught by listening servants; and to each angry speech of the baronet, Mrs. Bainbridge added an envenomed point worse than all.

More dead than alive, Rosina was at last dismissed. Whether guided by despair, whether she took Sir Peter’s threats literally, or whether his sister’s orders were more decisive, none knew, but Rosina left the house; a servant saw her cross the park, weeping, and wringing her hands as she went. What became of her none could tell; her disappearance was not disclosed to Sir Peter till the following day, and then he showed by his anxiety to trace her steps and to find her, that his words had been but idle threats. The truth was, that though Sir Peter went to frightful lengths to prevent the marriage of the heir of his house with the portionless orphan, the object of his charity, yet in his heart he loved Rosina, and half his violence to her rose from anger at himself for treating her so ill. Now remorse began to sting him, as messenger after messenger came back without tidings of his victim; he dared not confess his worst fears to himself; and when his inhuman sister, trying to harden her conscience by angry words, cried, “The vile hussy has too surely made away with herself out of revenge to us;” an oath, the most tremendous, and a look sufficient to make even her tremble, commanded her silence. Her conjecture, however, appeared too true: a dark and rushing stream that flowed at the extremity of the park had doubtless received the lovely form, and quenched the life of this unfortunate girl. Sir Peter, when his endeavours to find her proved fruitless, returned to town, haunted by the image of his victim, and forced to acknowledge in his own heart that he would willingly lay down his life, could he see her again, even though it were as the bride of his son — his son, before whose questioning he quailed like the veriest coward; for when Henry was told of the death of Rosina, he suddenly returned from abroad to ask the cause — to visit her grave, and mourn her loss in the groves and valleys which had been the scenes of their mutual happiness. He made a thousand inquiries, and an ominous silence alone replied. Growing more earnest and more anxious, at length he drew from servants and dependants, and his odious aunt herself, the whole dreadful truth. From that moment despair struck his heart, and misery named him her own. He fled from his father’s presence; and the recollection that one whom he ought to revere was guilty of so dark a crime, haunted him, as of old the Eumenides tormented the souls of men given up to their torturings.

His first, his only wish, was to visit Wales, and to learn if any new discovery had been made, and.whether it were possible to recover the mortal remains of the lost Rosina, so to satisfy the unquiet longings of his miserable heart. On this expedition was he bound, when he made his appearance at the village before named; and now in the deserted tower, his thoughts were busy with images of despair and death, and what his beloved one had suffered before her gentle nature had been goaded to such a deed of woe.

While immersed in gloomy reverie, to which the monotonous roaring of the sea made fit accompaniment, hours flew on, and Vernon was at last aware that the light of morning was creeping from out its eastern retreat, and dawning over the wild ocean, which still broke in furious tumult on the rocky beach. His companions now roused themselves, and prepared to depart. The food they had brought with them was damaged by sea water, and their hunger, after hard labour and many hours fasting, had become ravenous. It was impossible to put to sea in their shattered boat; but there stood a fisher’s cot about two miles off, in a recess in the bay, of which the promontory on which the tower stood formed one side, and to this they hastened to repair; they did not spend a second thought on the light which had saved them, nor its cause, but left the ruin in search of a more hospitable asylum. Vernon cast his eves round as he quitted it, but no vestige of an inhabitant met his eye, and he began to persuade himself that the beacon had been a creation of fancy merely. Arriving at the cottage in question, which was inhabited by a fisherman and his family, they made an homely breakfast, and then prepared to return to the tower, to refit their boat, and if possible bring her round. Vernon accompanied them, together with their host and his son. Several questions were asked concerning the Invisible Girl and her light, each agreeing that the apparition was novel, and not one being able to give even an explanation of how the name had become affixed to the unknown cause of this singular appearance; though both of the men of the cottage affirmed that once or twice they had seen a female figure in the adjacent wood, and that now and then a stranger girl made her appearance at another cot a mile off, on the other side of the promontory, and bought bread; they suspected both these to be the same, but could not tell. The inhabitants of the cot, indeed, appeared too stupid even to feel curiosity, and had never made any attempt at discovery. The whole day was spent by the sailors in repairing the boat; and the sound of hammers, and the voices of the men at work, resounded along the coast, mingled with the dashing of the waves. This was no time to explore the ruin for one who whether human or supernatural so evidently withdrew herself from intercourse with every living being. Vernon, however, went over the tower, and searched every nook in vain; the dingy bare walls bore no token of serving as a shelter; and even a little recess in the wall of the staircase, which he had not before observed, was equally empty and desolate.

Quitting the tower, he wandered in the pine wood that surrounded it, and giving up all thought of solving the mystery, was soon engrossed by thoughts that touched his heart more nearly, when suddenly there appeared on the ground at his feet the vision of a slipper. Since Cinderella so tiny a slipper had never been seen; as plain as shoe could speak, it told a tale of elegance, loveliness, and youth. Vernon picked it up; he had often admired Rosina’s singularly small foot, and his first thought was a question whether this little slipper would have fitted it. It was very strange! — it must belong to the Invisible Girl. Then there was a fairy form that kindled that light, a form of such material substance, that its foot needed to be shod; and yet how shod? — with kid so fine, and of shape so exquisite, that it exactly resembled such as Rosina wore! Again the recurrence of the image of the beloved dead came forcibly across him; and a thousand home-felt associations, childish yet sweet, and lover-like though trifling, so filled Vernon’s heart, that he threw himself his length on the ground, and wept more bitterly than ever the miserable fate of the sweet orphan.

In the evening the men quitted their work, and Vernon returned with them to the cot where.they were to sleep, intending to pursue their voyage, weather permitting, the following morning.

Vernon said nothing of his slipper, but returned with his rough associates. Often he looked back; but the tower rose darkly over the dim waves, and no light appeared. Preparations had been made in the cot for their accommodation, and the only bed in it was offered Vernon; but he refused to deprive his hostess, and spreading his cloak on a heap of dry leaves, endeavoured to give himself up to repose. He slept for some hours; and when he awoke, all was still, save that the hard breathing of the sleepers in the same room with him interrupted the silence. He rose, and going to the window, — looked out over the now placid sea towards the mystic tower; the light burning there, sending its slender rays across the waves. Congratulating himself on a circumstance he had not anticipated, Vernon softly left the cottage, and, wrapping his cloak round him, walked with a swift pace round the bay towards the tower. He reached it; still the light was burning. To enter and restore the maiden her shoe, would be but an act of courtesy; and Vernon intended to do this with such caution, as to come unaware, before its wearer could, with her accustomed arts, withdraw herself from his eyes; but, unluckily, while yet making his way up the narrow pathway, his foot dislodged a loose fragment, that fell with crash and sound down the precipice. He sprung forward, on this, to retrieve by speed the advantage he had lost by this unlucky accident. He reached the door; he entered: all was silent, but also all was dark. He paused in the room below; he felt sure that a slight sound met his ear. He ascended the steps, and entered the upper chamber; but blank obscurity met his penetrating gaze, the starless night admitted not even a twilight glimmer through the only aperture. He closed his eyes, to try, on opening them again, to be able to catch some faint, wandering ray on the visual nerve; but it was in vain. He groped round the room: he stood still, and held his breath; and then, listening intently, he felt sure that another occupied the chamber with him, and that its atmosphere was slightly agitated by an-other’s respiration. He remembered the recess in the staircase; but, before he approached it, he spoke: — he hesitated a moment what to say. “I must believe,” he said, ‘that misfortune alone can cause your seclusion; and if the assistance of a man — of a gentleman — “

An exclamation interrupted him; a voice from the grave spoke his name — the accents of Rosina syllabled, “Henry! — is it indeed Henry whom I hear?”

He rushed forward, directed by the sound, and clasped in his arms the living form of his own lamented girl — his own Invisible Girl he called her; for even yet, as he felt her heart beat near his, and as he entwined her waist with his arm, supporting her as she almost sank to the ground with agitation, he could not see her; and, as her sobs prevented her speech, no sense, but the instinctive one that filled his heart with tumultuous gladness, told him that the slender, wasted form he pressed so fondly was the living shadow of the Hebe beauty he had adored.

The morning saw this pair thus strangely restored to each other on the tranquil sea, sailing with a fair wind for L — , whence they were to proceed to Sir Peter’s seat, which, three months before, Rosina had quitted in such agony and terror. The morning light dispelled the shadows that had veiled her, and disclosed the fair person of the Invisible Girl. Altered indeed she was by suffering and woe, but still the same sweet smile played on her lips, and the tender light of her soft blue eyes were all her own. Vernon drew out the slipper, and shoved the cause that had occasioned him to resolve to discover the guardian of the mystic beacon; even now he dared not inquire how she had existed in that desolate spot, or wherefore she had so sedulously avoided observation, when the right thing to have been done was, to have sought him immediately, under whose care, protected by whose love, no danger need be feared. But Rosina shrunk from him as he spoke, and a death-like pallor came over her cheek, as she faintly whispered, ‘Your father’s curse — your father’s dreadful threats!” It appeared, indeed, that Sir Peter’s violence, and the cruelty of Mrs. Bainbridge, had succeeded in impressing Rosina with wild and unvanquishable terror. She had fled from their house without plan or forethought — driven by frantic horror and overwhelming fear, she had left it with scarcely any money, and there seemed to her no possibility of either returning or proceeding onward. She had no friend except Henry in the wide world; whither could she go? — to have sought Henry would have sealed their fates to misery; for, with an oath, Sir Peter had declared he would rather see them both in their coffins than married. After wandering about, hiding by day, and only venturing forth at night, she had come to this deserted tower, which seemed a place of refuge. I low she had lived since then she could hardly tell; — she had lingered in the woods by day, or slept in the vault of the tower, an asylum none were acquainted with or had discovered: by night she burned the pine-cones of the wood, and night was her dearest time; for it seemed to her as if security came with darkness. She was unaware that Sir Peter had left that part of the country, and was terrified lest her hiding-place should be revealed to him. Her only hope was that Henry would return — that Henry would never rest till he had found her. She confessed that the long interval and the approach of winter had visited her with dismay; she feared that, as her strength was failing, and her form wasting to a skeleton, that she might die, and never see her own Henry more.

An illness, indeed, in spite of all his care, followed her restoration to security and the comforts of civilized life; many months went by before the bloom revisiting her cheeks, and her limbs regaining their roundness, she resembled once more the picture drawn of her in her days of bliss, before any visitation of sorrow. It was a copy of this portrait that decorated the tower, the scene of her suffering, in which I had found shelter. Sir Peter, overjoyed to be relieved from the pangs of remorse, and delighted again to see his orphan-ward, whom he really loved, was now as eager as before he had been averse to bless her union with his son: Mrs. Bainbridge they never saw again. But each year they spent a few months in their Welch mansion, the scene of their early wedded happiness, and the spot where again poor Rosina had awoke to life and joy after her cruel persecutions. Henry’s fond care had fitted up the tower, and decorated it as I saw; and often did he come over, with his “Invisible Girl,” to renew, in the very scene of its occurrence, the remembrance of all the incidents which had led to their meeting again, during the shades of night, in that sequestered ruin.

Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851)

The Invisible Girl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

God zij geloofd is er Pepsi

Welkom in St. Mery Hotel

we hebben pepsi: drie birr

we hebben brood met pepsi: vijf birr

daarom kent iedereen ons in Konso

soms hebben we mirinda

dan kunnen we u brood met mirinda aanbieden

kom terug als we mirinda hebben

maar we hebben altijd pepsi

‘s ochtends, ‘s middags en ‘s avonds

kunnen we u brood met pepsi aanbieden

want we hebben altijd pepsi

kijk maar naar de blauwe letters

op het witte pepsireclamebord

met de rode pepsivlag

en de rood-wit-blauwe pepsibal

iedereen in Konso weet het

iedereen is welkom in St. Mery hotel

voor een maaltijd met pepsi: vijf birr

god zij dank is er pepsi

anders at u bij ons alleen droog brood

maar gelukkig hebben wij brood met pepsi

pepsi is echt een uitkomst voor u

wij zijn er trots op, heel trots

dat wij altijd pepsi in huis hebben

jammer dat we juist vandaag geen pepsi hebben

en gisteren was er ook geen pepsi

en morgen misschien ook niet,

maar volgende week of zeker over twee weken

hebben wij pepsi in huis, heel zeker

kom over een paar weken terug in St. Mery Hotel

want we hebben altijd pepsi

Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten. In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, FDM in Africa, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen

Dode Vogel

Een dode vogel

in een droog landschap

De nagels in een laatste kramp

vastgeklemd rond de tak

houden hem overeind in de zon

Kleurige vleugels

bedekken zijn lege lijf

de witte oogkassen

door de wind leeggevreten

Hij is de wachter

die waarschuwt voor de dood

Ton van Reen: Dode Vogel

Uit: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature