Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

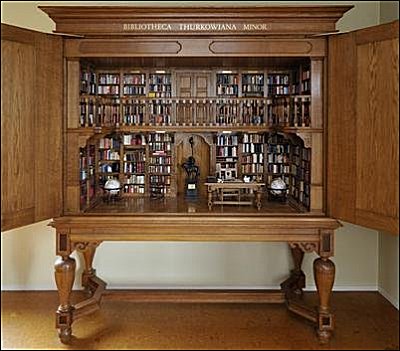

Museum Meermanno

verwerft Bibliotheca Thurkowiana minor

Vandaag, vrijdag 13 april vindt de overdracht plaats van een belangrijke nieuwe aanwinst voor Museum Meermanno | Huis van het boek: de Bibliotheca Thurkowiana Minor, een zeer aantrekkelijke miniatuurbibliotheek die werd opgericht door Guus en Luce Thurkow. De bibliotheek bevat 1515 miniatuurboeken en is een aanvulling op de collectie bijzondere boekvormen van het museum en uiteraard een fenomeen op zich.

Het was de wens van Guus Thurkow (1942-2011) en van het museum dat zijn miniatuurbibliotheek getoond zou worden aan het publiek en bewaard zou blijven voor toekomstige generaties. Met de genereuze steun van Fonds 1818 en de Vrienden van het museum is dit nu gerealiseerd.

Van 1984 tot 2003 verzorgden Guus en Luce Thurkow onder de naam ‘The Catharijne Press’ een antiquariaat en uitgeverij van miniatuurboeken. Op 1 januari 2001 besloten zij een bibliotheek voor miniatuurboeken te laten bouwen naar het voorbeeld van beroemde 17de- en 18de-eeuwse Nederlandse poppenhuizen. Uitgaande van de maximale grootte van een miniatuurboek van 3 inch oftewel 76 mm werd als maatvoering gekozen voor een schaal van 1 op 4.

Met medewerking van diverse specialisten werd deze Bibliotheca Thurkowiana Minor reeds binnen een jaar voltooid. De bibliotheek omvat twintig boekenkasten met zes planken en is verder ingericht met een aard- en een hemelglobe, een werktafel en stoel voor de bibliothecaris, een boekentrap en een standbeeld van Don Quichote, de beschermheer van de bibliotheek.

De collectie is klassiek ingedeeld in rubrieken als Historia Naturalis en Musica, en een enkele meer moderne categorie als Photographia. De afdeling Erotica is vanzelfsprekend achter een geheime toegang verborgen.

Zowel de inhoud als de verschijningsvorm van de boeken is zeer divers: van Prediker tot Het kleine insektenboek van Godfried Bomans en van buidelboek tot leporello, een modern gevouwen boek. Het oudste object in de verzameling is een kleitablet uit 1803 vóór Christus. Van deze boeken zijn er 59 unica: werken gedrukt in een oplage van slechts één exemplaar en enige handschriften. Vele hiervan zijn speciaal voor deze bibliotheek gemaakt, waaronder een xylotheek (verzameling houtmonsters) en een miniatuur wastafeltje, inclusief schrijfstift. Al deze werken zijn samengebracht onder het motto van de bibliotheek, een zinsnede uit Cervantes’ Don Quichote: ‘Ellos son gigantes’ (‘Zij zijn reuzen’).

Deze miniatuurbibliotheek is voorlopig beperkt toegankelijk. Iedere woensdagmiddag om 13.00 uur opent een museummedewerker de kast en toont diverse voorbeelden van miniatuurboeken.

Museum Meermanno | Huis van het boek – Prinsessegracht 30, Den Haag

Source website: www.meermanno.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers

Ton van Reen

EEN NOG SCHONERE SCHIJN VAN WITHEID

Een winterverhaal

5

“Alles mag je weten,” zei grootmoeder, “maar jongens hebben soms geheimen.”

“Dus het ging over jou,” zei moeder opgelucht, omdat alles wat wij te vertellen hadden, terwijl zij buiten met de lakens vocht, niets met haar van doen had. “Ik dacht al dat het over mij ging. Ik zag wel dat jullie me uitlachten.”

“We zouden niet durven,” zei grootmoeder.

Mijn moeder pakte de kam en liep naar haar slaapkamer om haar verwaaide haren te kammen. Wij bleven stil wachten. Wij wisten wat het betekende, vooral als het lang duurde. Soms zag ik mijn moeder als de deur van haar slaapkamer openstond en ze voor de spiegel van de commode zat, soms wel tien minuten. Dan was het altijd alsof ze haar haren kamde voor de grote en sprekende foto van mijn zo vroeg gestorven vader, wiens foto ze zo naar de spiegel had gekeerd dat het was of hij naar haar keek. Het leek alsof ze het voor hem deed. Ze maakte zich mooi voor hem. Door een kier van de deur bleef ik kijken, ademloos. En als ik wist dat zij wist dat ik er stond, liep ik fluitend of zingend naar beneden, spelend dat ik niets had gezien, maar de tranen stonden dik in mijn keel van ontroering.

“Je mag alles weten, mam,” zei ik, toen ze terugkwam in de keuken, haar haren mooi alsof ze naar de kerk ging. “Maar je weet alles al.”

“Ja, ik weet alles,” zei ze, kijkend naar de lakens die zacht als was waren geworden.

Ik liep naar buiten, net of ik naar de konijnen ging kijken, tenslotte wist ik dat van kinderen werd verwacht dat ze zich groot hielden en dat ze nooit klein moesten zijn. Ik speelde dat ik naar de wolken ging kijken, die misschien sneeuw zouden brengen. Of misschien liep ik gewoon naar buiten omdat kinderen soms buiten moeten zijn. Ik zweer het, kinderen moeten soms naar buiten geschopt worden, omdat geen mens snapt wat er in hun hoofden omgaat. Buiten kunnen ze pas alleen zijn. En ze weten dat daarbinnen de anderen over hen praten. Maar of grootmoeders en moeders echt iets van hun kinderen snappen, betwijfel ik.

Ik zweer het, als ik nu naar binnen zou gaan op fluistervoeten, in de sokken die mijn grootmoeder voor me heeft gebreid, zal ik horen dat ze over mij praten, grootmoeder en moeder. Maar ik mag het niet horen omdat wat ze zeggen niet voor mijn oren bestemd is en omdat het tegen de spelregels is. Ik loop buiten alleen maar wat rond om de tranen in mijn ogen te laten bevriezen. En er valt genoeg te lachen. Ik hoor de arbeiders van de steenfabriek met hun gore moppen waar ik geen bal van snap, maar die toch heel lollig moeten zijn.

Ik moet sterk zijn. Want straks komen mijn broers thuis. Ze moeten echt niet denken dat ik een hamster of een hond ben, alleen maar omdat ik een beetje verdrietig ben. Ik begin met terugslaan. Ik sla ze gewoon op hun kop. Ik weet alles.

EINDE

Het verhaal Een nog schonere schijn van witheid van Ton van Reen werd uitgegeven op 26 februari 2012 in opdracht van De Bibliotheek Maas en Peel, ter gelegenheid van de heropening van de bibliotheek in Maasbree. Teksten uit het verhaal zijn aangebracht op glazen wanden.

© Ton van Reen

Proza van Ton van Reen:

Geen oorlog roman

De moord novelle

De gevangene novelle

Lachgas roman

Landverbeuren roman

De zondvloed novelle

Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam roman

Bevroren dromen roman

Het diepste blauw roman

Concert voor de Führer roman

Het winterjaar roman

In het donkere zuiden verhalen

Thuiskomst novelle

Roomse meisjes roman

Zomerbloei novelle

Wie zo van vrouwen houdt verhaal

Gevallen ster roman

Brandende mannen roman

De bende van de bokkenrijders roman 12+

Gestolen jeugd roman 12+

Vlucht voor het vuur jeugdroman

Dwars door het glas jeugdroman

Voor meer informatie: www.tonvanreen.nl

fleursdumal.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

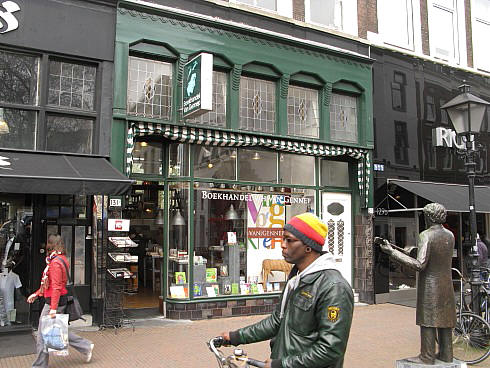

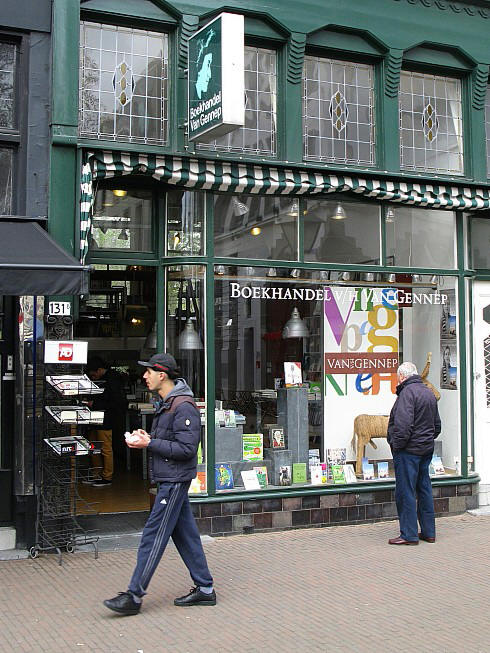

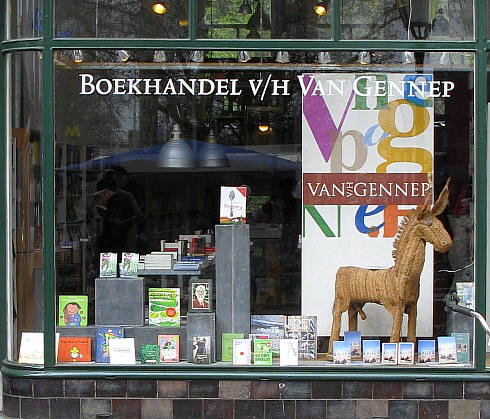

Bookstores: Boekhandel v/h Van Gennep

Oude Binnenweg 131b – 3012 JD Rotterdam

Books. The last chapter? Photos: anton k. 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Bookstores

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

5

A problem which I find it far more difficult to solve is this: how in the world Giorgio Mirelli, who would fly with such impatience from every complication, can have lost himself to this woman, to the point of laying down his life on her account.

Almost all the details are lacking that would enable me to solve this problem, and I have said already that I have no more than a summary report of the drama.

I know from various sources that the Nestoroff, at Capri, when Giorgio Mirelli saw her for the first time, was in distinctly bad odour, and was treated with great diffidence by the little Russian colony, which for some years past has been settled upon that island.

Some even suspected her of being a spy, perhaps because she, not very prudently, had introduced herself as the widow of an old conspirator, who had died some years before her coming to Capri, a refugee in Berlin. It appears that some one wrote for information, both to Berlin and to Petersburg, with regard to her and to this unknown conspirator, and that it came to light that a certain Nikolai Nestoroff had indeed been for some years in exile in Berlin, and had died there, but without ever having given anyone to understand that he was exiled for political reasons. It appears to have become known also that this Nikolai Nestoroff had taken her, as a little girl, from the streets, in one of the poorest and most disreputable quarters of Petersburg, and, after having her educated, had married her; and then, reduced by his vices to the verge of starvation had lived upon her, sending her out to sing in music-halls of the lowest order, until, with the police on his track, he had made his escape, alone, into Germany. But the Nestoroff, to my knowledge, indignantly denies all these stories.

That she may have complained privately to some one of the ill-treatment, not to say the cruelty she received from her girlhood at the hands of this old man is quite possible; but she does not say that he lived upon her; she says rather that, of her own accord, obeying the call of her passion, and also, perhaps, to supply the necessities of life, having overcome his opposition, she took to acting in the provinces, a-c-t-i-n-g, mind, on the legitimate stage; and that then, her husband having fled from Russia for political reasons and settled in Berlin, she, knowing him to be in frail health and in need of attention, taking pity on him, had joined him there and remained with him till his death. What she did then, in Berlin, as a widow, and afterwards in Paris and Vienna, cities to which she often refers, shewing a thorough knowledge of their life and customs, she neither says herself nor certainly does anyone ever venture to ask her.

For certain people, for innumerable people, I should say, who are incapable of seeing anything but themselves, love of humanity often, if not always, means nothing more than being pleased with themselves.

Thoroughly pleased with himself, with his art, with his studies of landscape, must Giorgio Mirelli, unquestionably, have been in those days at Capri.

Indeed–and I seem to have said this before–his habitual state of mind was one of rapture and amazement. Given such a state of mind, it is easy to imagine that this woman did not appear to him as she really was, with the needs that she felt, wounded, scourged, poisoned by the distrust and evil gossip that surrounded her; but in the fantastic transfiguration that he at once made of her, and illuminated by the light in which he beheld her. For him feelings must take the form of colours, and, perhaps, entirely engrossed in his art, he had no other feeling left save for colour. All the impressions that he formed of her were derived exclusively, perhaps, from the light which he shed upon her; impressions, therefore, that were felt by him alone. She need not, perhaps could not participate in them. Now, nothing irritates us more than to be shut out from an enjoyment, vividly present before our eyes, round about us, the reason of which we can neither discover nor guess. But even if Giorgio Mirelli had told her of his enjoyment, he could not have conveyed it to her mind. It was a joy felt by him alone, and proved that he too, in his heart, prayed and wished for nothing else of her than her body; not, it is true, like other men, with base intent; but even this, in the long run–if you think it over carefully–could not but increase the woman’s irritation. Because, if the failure to derive any assistance, in the maddening uncertainties of her spirit, from the many who saw and desired nothing in her save her body, to satisfy on it the brutal appetite of the senses, filled her with anger and disgust; her anger with the one man, who also desired her body and nothing more; her body, but only to extract from it an ideal and absolutely self-sufficient pleasure, must have been all the stronger, in so far as every provocative of disgust was entirely lacking, and must have rendered more difficult, if not absolutely futile, the vengeance which she was in the habit of wreaking upon other people. An angel, to a woman, is always more irritating than a beast.

I know from all Giorgio Mirelli’s artist friends in Naples that he was spotlessly chaste, not because he did not know how to make an impression upon women, but because he instinctively avoided every vulgar distraction.

To account for his suicide, which beyond question was largely due to the Nestoroff, we ought to assume that she, not cared for, not helped, and irritated to madness, in order to be avenged, must with the finest and subtlest art have contrived that her body should gradually come to life before his eyes, not for the delight of his eyes alone; and that, when she saw him, like all the rest, conquered and enslaved, she forbade him, the better to taste her revenge, to take any other pleasure from her than that with which, until then, he had been content, as the only one desired, because the only one worthy of him.

‘We ought’, I say, to assume this, but only if we wish to be ill-natured. The Nestoroff might say, and perhaps does say, that she did nothing to alter that relation of pure friendship which had grown up between herself and Mirelli; so much so that when he, no longer contented with that pure friendship, more impetuous than ever owing to the severe repulse with which she met his advances, yet, to obtain his purpose, offered to marry her, she struggled for a long time–and this is true; I learned it on good authority–to dissuade him, and proposed to leave Capri, to disappear; and in the end remained there only because of his acute despair.

But it is true that, if we wish to be ill-natured, we may also be of opinion that both the early repulse and the later struggle and threat and attempt to leave the island, to disappear, were perhaps so many artifices carefully planned and put into practice to reduce this young man to despair after having seduced him, and to obtain from him all sorts of things which otherwise he would never, perhaps, have conceded to her. Foremost among them, that she should be introduced as his future bride at the Villa by Sorrento to that dear Granny, to that sweet little sister, of whom he had spoken to her, and to the sister’s betrothed.

It seems that he, Aldo Nuti, more than, the two women, resolutely opposed this claim. Authority and power to oppose and to prevent this marriage he did not possess, for Giorgio was now his own master, free to act as he chose, and considered that he need no longer give an account of himself to anyone; but that he should bring this woman to the house and place her in contact with his sister, and expect the latter to welcome her and to treat her as a sister, this, by Jove, he could and must oppose, and oppose it he did with all his strength. But were they, Granny Rosa and Duccella, aware what sort of woman this was that Giorgio proposed to bring to the house and to marry? A Russian adventuress, an actress, if not something worse! How could he allow such a thing, how not oppose it with all his strength?

Again “with all his strength”… Ah, yes, who knows how hard Granny Rosa and Duccella had to fight in order to overcome, little by little, by their sweet and gentle persuasion, all the strength of Aldo Nuti. How could they have imagined what was to become of that strength at the sight of Varia Nestoroff, as soon as she set foot, timid, ethereal and smiling, in the dear villa by Sorrento!

Perhaps Giorgio, to account for the delay which Granny Rosa and Duccella shewed in answering, may have said to the Nestoroff that this delay was due to the opposition “with all his strength” of his sister’s future husband; so that the Nestoroff felt the temptation to measure her own strength against this other, at once, as soon as she set foot in the villa. I know nothing! I know that Aldo Nuti was drawn in as though into a whirlpool and at once carried away like a wisp of straw by passion for this woman.

I do not know him. I saw him as a boy, once only, when I was acting as Giorgio’s tutor, and he struck me as a fool. This impression of mine does not agree with what Mirelli said to me about him, on my return from Liege, namely that he was ‘complicated’. Nor does what I have heard from other people, with regard to him correspond in the least with this first impression, which however has irresistibly led me to speak of him according to the idea that I had formed of him from it. I must, really, have been mistaken. Duccella found it possible to love him! And this, to my mind, does more than anything else to prove me in the wrong. But we cannot control our impressions. He may be, as people tell me, a serious young man, albeit of a most ardent temperament; for me, until I see him again, he will remain that fool of a boy, with the baron’s coronet on his handkerchiefs and portfolios, the young gentleman who ‘would so love to become an actor’.

He became one, and not by way of make-believe, with the Nestoroff, at Giorgio Mirelli’s expense. The drama was unfolded at Naples, shortly after the Nestoroff’s introduction and brief visit to the house at Sorrento. It seems that Nuti returned to Naples with the engaged couple, after that brief visit, to help the inexperienced Giorgio and her who was not yet familiar with the town, to set their house in order before the wedding.

Perhaps the drama would not have happened, or would have had a different ending, had it not been for the complication of Duccella’s engagement to, or rather her love for Nuti. For this reason Giorgio Mirelli was obliged to concentrate on himself the violence of the unendurable horror that overcame him at the sudden discovery of his betrayal.

Aldo Nuti rushed from Naples like a madman before there arrived from Sorrento at the news of Giorgio’s suicide Granny Rosa and Duccella.

Poor Duccella, poor Granny Rosa! The woman who from thousands and thousands of miles away came to bring confusion and death into your little house where with the jasmines bloomed the most innocent of idylls, I have her here, now, in front of my machine, every day; and, if the news I have heard from Polacco be true, I shall presently have him here as well, Aldo Nuti, who appears to have heard that the Nestoroff is leading lady with the Kosmograph.

I do not know why, my heart tells me that, as I turn the handle of this photographic machine, I am destined to carry out both your revenge and your poor Giorgio’s, dear Duccella, dear Granny Rosa!

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

(to be continued)

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

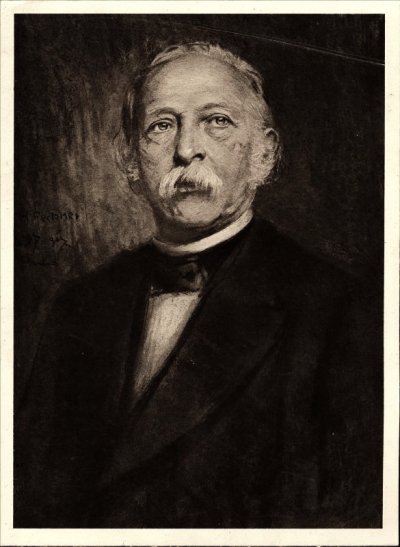

theodor fontane by max liebermann

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Memento

Geliebte, willst du doppelt leben,

So sei des Todes gern gedenk

Und nimm, was dir die Götter geben,

Tagtäglich hin wie ein Geschenk.

Mach dich vertraut mit dem Gedanken,

Daß doch das Letzte kommen muß,

Und statt in Trübsinn hinzukranken,

Wird dir das Dasein zum Genuß.

Du magst nicht länger mehr vergeuden

Die Spanne Zeit in eitlem Haß,

Du freust dich reiner deiner Freuden

Und sorgst nicht mehr um dies und das.

Du setzest an die rechte Stelle

Das Hohe, Göttliche der Zeit,

Und jede Stunde wird dir Quelle

Gesteigert neuer Dankbarkeit.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

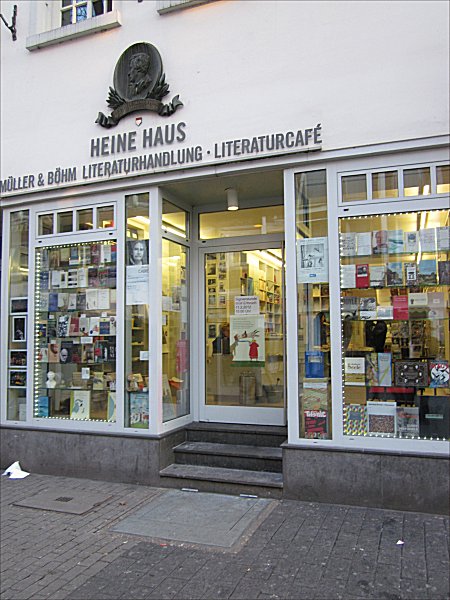

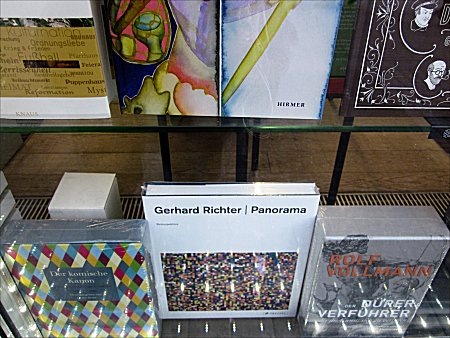

Books. The last chapter?

Bookstores :

Müller & Böhm – Literaturhandlung im Heine Haus

Bolkerstraße 53, Düsseldorf

photos: kemp=mag 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Bookstores

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (10)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

4

The experience of seeing men sink lower than the beasts must frequently have occurred to Varia Nestoroff.

And yet she has not killed them. A huntress, as you are a hunter. The snipe, you have killed. She has never killed anyone. One only, for her sake, has killed himself, by his own hand: Giorgio Mirelli; but not for her sake alone.

The beast, moreover, which does harm from a necessity of its nature, is not, so far as we know, unhappy.

The Nestoroff, as we have abundant grounds for supposing, is most unhappy. She does not enjoy her own wickedness, for all that it is carried out with such cold-blooded calculation.

If I were to say openly what I think of her to my fellow-operators, to the actors and actresses of the firm, all of them would at once suspect that I too had fallen in love with the Nestoroff.

I ignore this suspicion.

The Nestoroff feels for me, like all her fellow-artists, an almost instinctive aversion. I do not reciprocate it in any way because I do not spend my time with her, except when I am in the service of my machine, and then, as I turn the handle, I am what I am supposed to be, that is to say perfectly ‘impassive’. I am unable either to hate or to love the Nestoroff, as I am unable either to hate or to love anyone. I am ‘a hand that turns the handle’. When, finally, I am

restored to myself, that is to say when for me the torture of being only a hand is ended, and I can regain possession of the rest of my body, and marvel that I have still a head on my shoulders, and abandon myself once more to that wretched ‘superfluity’ which exists in me nevertheless and of which for almost the whole day my profession condemns me to be deprived; then… ah, then the affections, the memories that come to life in me are certainly not such as can persuade me to love this woman. I was the friend of Giorgio Mirelli, and among the most cherished memories of my life is that of the dear house in the country by Sorrento, where Granny Rosa and poor Duccella still live and mourn.

I study. I go on studying, because that is perhaps my ruling passion: it nourished in times of poverty and sustained my dreams, and it is the sole comfort that I have left, now that they have ended so miserably.

I study this woman, then, without passion but intently, who, albeit she may seem to understand what she is doing and why she does it, yet has not in herself any of that quiet “systematisation” of concepts, affections, rights and duties, opinions and habits, which I abominate in other people.

She knows nothing for certain, except the harm that she can do to others, and she does it, I repeat, with cold-blooded calculation.

This, in the opinion of other people, of all the “systematised,” debars her from any excuse. But I believe that she cannot offer any excuse, herself, for the harm which nevertheless she knows herself to have done.

She has something in her, this woman, which the others do not succeed in understanding, because even she herself does not clearly understand it. One guesses it, however, from the violent expressions which she assumes, involuntarily, unconsciously, in the parts that are assigned to her.

She alone takes them seriously, and all the more so the more illogical and extravagant they are, grotesquely heroic and contradictory. And there is no way of keeping her in check, of making her moderate the violence of those expressions. She alone ruins more films than all the other actors in the four companies put together. For one thing, she always moves out of the picture; when by any chance she does not move out, her action is so disordered, her face so strangely altered and disguised, that in the rehearsal theatre almost all the scenes in which she has taken part turn out useless and have to be done again.

Any other actress, who had not enjoyed and did not enjoy, as she does, the favour of the warm-hearted Commendator Borgalli, would long since have been given notice to leave.

Instead of which, “Dear, dear, dear…” exclaims the warm-hearted Commendatore, without the least annoyance, when he sees projected on the screen in the rehearsal theatre those demoniacal pictures, “dear, dear, dear… oh, come … no… is it possible? Oh, Lord, how horrible … cut it out, cut it out….”

And he finds fault with Polacco, and with all the producers in general, who keep the _scenarios_ to themselves, confining themselves to suggesting bit by bit to the actors the action to be performed in each separate scene, often disjointedly, because not all the scenes can be taken in order, one after another, in a studio. It often happens that the actors do not even know what part they are supposed to be taking in the play as a whole, and one hears some actor ask in the middle:

“I say, Polacco, am I the husband or the lover?”

In vain does Polacco protest that he has carefully explained the whole part to the Nestoroff. Commendator Borgalli knows that the fault does not lie with Polacco; so much so, that he has given him another leading lady, the Sgrelli, in order not to waste all the films that are allotted to his company. But the Nestoroff protests on her own account, if Polacco makes use of the Sgrelli alone, or of the Sgrelli more than of herself, the true leading lady of the company. Her

ill-wishers say that she does this to ruin Polacco, and Polacco himself believes it and goes about saying so. It is untrue: the only thing ruined, here, is film; and the Nestoroff is genuinely in despair at what she has done; I repeat, involuntarily and unconsciously. She herself remains speechless and almost terror-stricken at her own image on the screen, so altered and disordered. She sees there some one who is herself but whom she does not know. She would like not to recognise herself in this person, but at least to know her.

Possibly for years and years, through all the mysterious adventures of her life, she has gone in quest of this demon which exists in her and always escapes her, to arrest it, to ask it what it wants, why it is suffering, what she ought to do to soothe it, to placate it, to give it peace.

No one, whose eyes are not clouded by a passionate antipathy, and who has seen her come out of the rehearsal theatre after the presentation of those pictures of herself, can retain any doubt as to that. She is really tragic: terrified and enthralled, with that sombre stupor in her eyes which we observe in the eyes of the dying, and can barely restrain the convulsive tremor of her entire person.

I know the answer I should receive, were I to point this out to anyone:

“But it is rage! She is quivering with rage!”

It is rage, yes; but not the sort of rage that they all suppose, namely at a film that has gone wrong. A cold rage, colder than a blade of steel, is indeed this woman’s weapon against all her enemies. Now Cocò Polacco is not an enemy in her eyes. If he were, she would not tremble like that: with the utmost coldness she would avenge herself on him.

Enemies, to her, all the men become to whom she attaches herself, in order that they may help her to arrest the secret thing in her that escapes her: she herself, yes, but a thing that lives and suffers, so to speak, ‘outside herself’.

Well, no one has ever taken any notice of this thing, which to her is more pressing than anything else; everyone, rather, remains dazzled by her exquisite form, and does not wish to possess or to know anything else of her. And then she punishes them with a cold rage, just where their desires prick them; and first of all she exasperates those desires with the most perfidious art, that her revenge may be all the greater. She avenges herself by flinging her body, suddenly and coldly, at those whom they least expected to see thus favoured: like that, so as to shew them in what contempt she holds the thing that they prize most of all in her.

I do not believe that there can be any other explanation of certain sudden changes in her amorous relations, which appear to everyone, at first sight, inexplicable, because no one can deny that she has done harm to herself by them.

Except that the others, thinking it over and considering, on the one hand the nature of the men with whom she had consorted previously, and on the other that of the men at whom she has suddenly flung herself, say that this is due to the fact that with the former sort she could not remain, ‘could not breathe’; whereas to the latter she felt herself attracted by a “gutter” affinity; and this sudden and unexpected flinging of herself they explain as the sudden spring of a person who, after a long suffocation, seeks to obtain at last, ‘wherever he can’, a mouthful of air.

And if it should be just the opposite? If ‘in order to breathe’, to secure that help of which I have already spoken, she had attached herself to the former sort, and instead of having the ‘breathing-space’, the help for which she hoped, had found no breathing-space and no help from them, but rather an anger and disgust all the stronger because increased and embittered by disappointment, and also by a certain contempt which a person feels for the needs of another’s soul who sees and cares for nothing but his own SOUL, like that, in capital letters? No one knows; but of these “gutter” refinements those may well be capable who mostly highly esteem themselves, and are deemed ‘superior’ by their fellows. And then…then, better the gutter which offers itself as such, which, if it makes you sad, does not delude you; and which may have, as often it does have, a good side to it, and, now and then, certain traces of innocence, which cheer and refresh you all the more, the less you expected to find them there.

The fact remains that, for more than a year, the Nestoroff has been living with the Sicilian actor Carlo Ferro, who also is engaged by the Kosmograph: she is dominated by him and passionately in love with him. She knows what she may expect from such a man, and asks for nothing more. But it seems that she obtains far more from him than the others are capable of imagining.

This explains why, for some time back, I have set myself to study, with keen interest, Carlo Ferro also.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (10)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

(to be continued)

More in: -Shoot!

Ton van Reen

EEN NOG SCHONERE SCHIJN VAN WITHEID

Een winterverhaal

3

Vanachter het raam keken grootmoeder en ik toe hoe de gebeurtenis zich ging ontknopen. Ik verwachtte dat moeder aan de witte zeilen zou opstijgen en misschien zelfs tot boven de kersenbomen zou worden geblazen, zo wild gingen de lakens tekeer in de wind. En misschien zou ze wel over het dak van het kippenhok van buurman Hermans vliegen, en dan zou zijn zoon die een beetje gek was naar haar zwaaien. En misschien vloog ze wel over de drooghokken van de steenfabriek, waarin de uit leem gevormde stenen stonden te bevriezen in plaats van te drogen zodat de arbeiders die later weer allemaal weg moesten gooien. En misschien …, stel je toch voor dat ze met al haar lakens aan de bliksemafleider aan de top van de schoorsteen van de steenfabriek zou blijven hangen! Adembenemend, maar het zou kunnen! Het zou kunnen!!! Met moeder wist je het immers nooit. Een voor een werden de lakens uit haar handen gerukt en zeilden naar de boomgaard, alsof ze wilden ontkomen aan de zoveelste wasbeurt die ze nog doorzichtiger zou maken. Ze waren oud. Ze waren al van grootmoeder geweest. Twee generaties kinderen hadden ertussen geslapen.

Moeder won. Met de hark trok ze de lakens uit de takken, plukte ten slotte het laken van mijn zusje uit de kersenboom en klopte het af met een hardheid die op afstraffen leek. Triomfantelijk kwam ze naar binnen met het witrozige laken dat het kleinste was, maar het dapperst was geweest. Dat had je altijd: ik was ook het kleinst, en daarom moest ik altijd het hardst vechten tegen mijn oudere broers, die dachten dat ik een hamster of een hond was die je af en toe gewoon stiekem kon meppen als je een pestbui had.

Moeder zette de stijve lakens rechtop tegen de muur achter de kachel, waarna ze op een vreemde manier, vol schuldgevoel, in elkaar begonnen te zakken, ontmoedigd door de wetenschap dat ze opnieuw zouden worden gekookt en gestoomd tot ze weer kraakhelder zouden zijn en weer aan de wasdraad buiten zouden worden uitgehangen, hun uiterste witte witheid tonend, zodat de hele straat kon zien dat wij toch een proper gezin vormden ondanks het feit dat we drie jongens hadden die elke week op school tijdens de godsdienstles van de pastoor te horen kregen dat jongens nooit met zichzelf mochten spelen, omdat je dan langzaam krom ging groeien doordat het nat dat uit je piemel kwam afgetapt ruggenmerg was. Jongens die dat deden waren voorbestemd voor de hel of zouden in dit leven al gestraft worden doordat ze later alleen nog maar arbeider bij de steenfabriek of turfgraver in de Peel konden worden. Tja, waarschijnlijk had de pastoor gelijk, want de arbeiders die op het tasveld van de steenfabriek werkten, aan de overkant van de straat, waren allemaal wat grauw en mager en hadden dus de straf om arbeider te zijn zelf verdiend door als jongen in bed niet te slapen maar met zichzelf te spelen. En als ze het nou maar gebiecht hadden, want de pastoor wilde altijd van alle jongens weten hoe vaak ze het hadden gedaan, maar dat hadden ze waarschijnlijk niet gedurfd, ik ook niet trouwens, dus het was hun verdiende straf om in weer en wind stenen te vormen die later weer, als ze bevroren waren, moesten worden weggegooid. Vreemd volk, die arbeiders. Als ik in het poortje bij de straat stond, kon ik de schunnige moppen horen die ze aan elkaar vertelden. Het was geen leuke gedachte dat ik later een van hen zou moeten zijn en al dat gebazel van hen een leven lang zou moeten horen.

wordt vervolgd

Het verhaal Een nog schonere schijn van witheid van Ton van Reen werd uitgegeven op 26 februari 2012 in opdracht van De Bibliotheek Maas en Peel, ter gelegenheid van de heropening van de bibliotheek in Maasbree.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Das Fischermädchen

Steht auf sand’gem Dünenrücken

Eine Fischerhütt’ am Strand;

Abendrot und Netze schmücken

Wunderlich die Giebelwand.

Drinnen spinnt und schnurrt das Rädchen,

Blaß der Mond ins Fenster scheint,

Still am Herd das Fischermädchen

Denkt des letzten Sturms und – weint.

Und es klagen ihre Tränen:

»Weit der Himmel, tief die See,

Doch noch weiter geht mein Sehnen,

Und noch tiefer ist mein Weh.«

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Menno ter Braak

Onpolitieke reis

De Zwerftocht van Belcampo

De fantasie kan een bron van vertroosting zijn in dagen zoals wij die nu gedwongen zijn te beleven (en waarin het zo nu en dan bijna onmogelijk is de litteratuur en haar filialen voor iets belangrijks te houden). De werkelijke fantasie immers is zeldzaam; wie let op het wanhopige gebrek aan scheppende verbeeldingskracht, dat zekere politieke redevoeringen kenmerkt, komt niet ten onrechte tot de conclusie, dat de gemeenplaats voor de mens de gemakkelijkste manier is om zich te handhaven; wanneer hij dan bovendien nog kan loeien is zijn fortuin gemaakt en is hij volkomen ontslagen van de verplichting om zich te verdiepen in het wonder van zijn persoonlijk avontuur. Want daarvoor is fantasie nodig, en het is voor de betrokken staatslieden maar gelukkig, dat zij niet over de fantasie beschikken, nodig om zich reëel voor ogen te halen, met welke onberekenbare elementen zij voortdurend werken. Ware een staatsman een fantast, hij zou niet in staat zijn beslissingen te nemen, als hij tenminste niet tevens het type zou zijn van de gepassionneerde hazardspeler. De routine (van het spreken, van het handelen, van het in en uit een vliegtuig stappen, van het staan op de katheder, van het zitten in een parlement) is de tegenpool der fantasie; zij houdt de politiek zo lang op de been, tot de katastrofe komt en zelfs geen staatsman meer begrijpt, hoe hij tot voor kort zo… geroutineerd kon zijn.

‘Ik vind een van de ellendigste dingen’, lees ik in De Zwerftocht van Belcampo, dat het voor een gewoon mensch, ik bedoel iemand, die niet zelf achter de schermen werkt, onmogelijk is, zich een juiste voorstelling te vormen van de politieke toestand in zijn eigen tijd, omdat hem de gegevens daarvoor opzettelijk worden onthouden. Daardoor wordt al zijn denken over een van de belangrijkste dingen van zijn leven en het daarop gebaseerde kiezen voor een of andere politieke richting waardeloos. Wat de drukinkt biedt, is òf bewuste misleiding òf bewuste zoethouding van den lezer. Het grondbeginsel van de neutrale kranten is: de lezer moet, zonder dat hij het merkt, even wijs blijven als voorheen. Het neutrale is dan, dat de lezer tenminste niet in een bepaalde richting gedreven wordt; dat is ook zoo, hij wordt zijn heele leven lang rustig om den tuin geleid.

‘En dan, ten opzichte van de werkelijk belangrijke gebeurtenissen in de politiek is de pers, zonder dat zij het wil weten, een groep even groote leeken als de lezers zelf. Deze gebeurtenissen spelen zich af met de geheimzinnigheid van misdaden.’

De man, die deze regels schreef, werd bij het verschijnen van zijn vorige werk (De Verhalen van Belcampo, door mij besproken in het Zondagsblad van 10 Maart 1934), ergens vergeleken met Alfred Jarry, de auteur van de ‘guignolade’ Ubu Roi. De vergelijking gaat in sommige opzichten mank, maar treft gedeeltelijk doel, want juist dit inzicht in de absolute gemeenplaatsigheid der politieke voorgronden bracht Jarry er toe, in Ubu Roi de hele politiek voor te stellen als een spel van de meest elementaire driften; in dit stuk voltrekt zich het politieke drama van l père Ubu, de dikke dictator-generaal-veldmaarschalk, die door een staatsgreep aan het bewind komt om het weer te verliezen, in de sfeer van vloeken, schelden, opscheppen, gappen, lasteren, afpersen, vreten, paraderen en, niet te vergeten: op tijd uitknijpen naar het buitenland. Juist dit absoluut elementaire van de fantasie is het, waaraan Jarry’s beroemde Ubu zijn verdiende reputatie dankt; de politiek wordt hier gegeven als pure achtergrond van grote kwajongens, die behoefte hebben aan macht en die machtsbegeerte ook najagen, zolang de bodem hun niet te heet onder de voeten wordt. Door de voorgrond weg te nemen en de politieke wezens om te fantaseren tot personages, die in hun machtsbegeerte en vraatzucht onschuldig-elementair zijn gebleven, maakt Jarry van de politiek een enorme kinderkamer van volwassenen … wat zij onder een bepaald aspect ook is; de fantasie schept hier, dwars door de conventies der beschaving heen, een nieuwe wereld, die men een omgekeerd Paradijs zou kunnen noemen, zo naïef zijn deze pa en ma Ubu in het voldoen aan hun elementaire lusten.

Mensen met veel gevoel voor decorum kunnen Jarry en zijn held niet waarderen; anderzijds vindt men ook een bepaald soort gezellige anarchisten en bohémiens, die hem graag tot hun heilige zouden maken. Beide standpunten ten opzichte van Ubu zijn mij even vreemd; ik houd van Ubu om de elementaire paradijstoestand, waarin Jarry’s fantasie hem deed verkeren, maar ik heb er geen behoefte aan hem als een kurk op de fles van het wereldraadsel te beschouwen. Uit het feit, dat, zoals Belcampo zegt, een gewoon mens de gegevens van het politieke spel worden onthouden, is Ubu geboren als de voortreffelijk geslaagde wraakneming van een individualist en fantast, die er pleizier in had de hele poppenkast van het conventionele politieke gedoe in de lucht te laten vliegen. Die behoefte is, had ik bijna geschreven, menselijk; maar ik schrijf het niet, wetend, dat vele mensen niets prettiger vinden dan in Ubu een mystieke redder des volks en zo mogelijk een directe afgezant des hemels te zien. …

Om op De Zwerftocht van Belcampo terug te komen: dit boek is een volkomen onpolitieke reis door Europa, met name door Frankrijk en Italië. Ik bedoel met onpolitiek dus: onafhankelijk van ‘de gegevens, die ons worden onthouden’, geinspireerd door de dingen, die binnen ons bereik liggen, zoals daar zijn de mensen, die men ontmoet en de spijzen, die men opeet. Dat alles heeft een intens persoonlijk belang voor een ieder, en het doorkruist de politiek van Baedeker, die een voorgeschreven reisgenot in de wereld heeft gebracht. Tot Baedeker verhoudt Belcampo zich dus ongeveer als Ubu tot de officiële Mussolini, die altijd gelijk heeft, volgens de stempels op de Italiaanse muren; hij reist ‘op eigen gelegenheid’, haalt zijn kost op met het tekenen van portretten (een talent, dat hem, zij het kort, in een zeer persoonlijke relatie brengt tot de geportretteerden en hun ijdelheden), en is dus fantastisch, waar anderen maar al te vaak conventioneel zijn. Zo wordt de zwerftocht van Belcampo een persoonlijk avontuur, waardoor de lezer, die van zulke reizen vermag te genieten, van het begin tot het eind geboeid wordt. Hij wordt vooral geboeid, omdat Belcampo niet ‘fantaseert’, maar fantastisch denkt en voelt; hij zou niet anders kunnen schrijven dan hij doet, deze persoonlijke wijze van zien, die men ten onrechte met grappigheid zou verwarren, is volkomen spontaan. De stijl van Belcampo is ontstaan als een puberteitsgril, hetgeen men zo nu en dan ook nog wel even merkt; een zin als: ‘ik liet een behoorlijk diner aan- en mijn maag binnenrukken’ herinnert aan de afstamming dezer fantasie, die zich overigens van dat soort goedkoop effect vrijwel geheel heeft gemancipeerd. Want in het proza, dat Belcampo tegenwoordig schrijft, wordt de fantastische reis tevens een betuiging van trouw aan het persoonlijk observeren van mensen en dingen, waarvan de volwassenen doorgaans meer en meer verstoken raken; fantasie is hier geen bedenksel, maar een beroep op een realiteit, die voor het grijpen ligt en versmaad wordt. Iedereen zou zo kunnen reizen als Belcampo, wanneer hij maar niet gehandicapt werd door de vervloekte neiging om ook het meest tot persoonlijk leven aansporende, het reizen, direct om te zetten in een reeks conventionele gewaarwordingen; in plaats van alle sterretjes van Baedeker of de Guide Bleu af te lopen, kan men de mensen in hun gezicht zien en het landschap als een ontmoeting ondergaan, ook waar het niet officieel wordt aangeduid als bijzonder overweldigend schoon.

Wat is niet een dag, bij het reizen! ‘Dikwijls komt het me voor’, zegt Belcampo, ‘dat de dag schoksgewijze verloopt; plotseling verandert er iets in de lucht, je weet niet wat, maar je weet wel, nu is het middag geworden, nu is het namiddag geworden; dat een punt van het aardoppervlak dus niet een cirkel beschrijft, maar de omtrek van een zeshoek, waarvan men de zijden kan voorstellen als: ochtend, voormiddag, middag, namiddag, avond en nacht.’ Dit beleven van de reisdag is persoonlijk, maar is tevens algemeen genoeg om door een ander herkend te worden als een sensatie, die ook hem (zij het misschien niet geformuleerd) eens overkwam. Zo gaat het trouwens altijd met een fantastisch (werkelijk fantastisch) auteur; de beschrijving van diens gewaarwordingen ervaart de lezer als een verrassing, maar hij voelt ook, hoe de beschreven gewaarwordingen iets in hemzelf laten meetrillen, dat hij allang in zich had, maar om conventionele redenen niet durfde uitspreken. Belcampo nu heeft de onbevangenheid, die het iemand mogelijk maakt in een conventioneel geordende wereld anarchist te blijven (zonder daarom prijs te stellen op de naam anarchist, die immers alweer een politieke onderscheiding is!); hij vertoeft met een man uit Borne (Twente) op de Vesuvius, en men weet niet, hoe hij de onconventionele synthese tussen die twee elementen tot stand brengt, maar hij doet het!

Zulk een fantast moet men in ere houden, want hij houdt onze gevoeligheid voor persoonlijke indrukken zuiver, hij redt ons, met andere woorden, telkens weer van de steriliserende systeemdwang door de conventie. … Aan het slot van zijn Zwerftocht ontwikkelt Belcampo trouwens, plotseling en geheel onverwacht, zoals het een fantast betaamt, een soort eigen systeem, waarin zijn manier van reageren op de dingen stilzwijgend is verdisconteerd. Voornaamste kenmerk van een cultuurvolk is, zegt hij, dat de drang tot vereenvoudiging van het wereldbeeld heeft geleid tot een voor allen geldend resultaat. Voorshands is die vereenvoudiging alleen te bereiken in een wereldbeeld, gebaseerd op overeenkomst van indrukken: ‘Men zet het roode bij het roode, het natte bij het natte en beschouwt zulke overeenkomstige indrukken als op de een of andere wijze aan elkaar verwant, en het spreekt vanzelf dat deze verwantschap doorgetrokken kan worden tot buiten het waarneembare.’ Pas in latere, minder primitieve cultuurstadia wordt de vereenvoudiging bereikt door een tweede wereldbeeld, waarin de indrukken niet naar hun onderlinge overeenkomst worden gerangschikt, maar naar hun oorzaak en gevolg, een abstracte wetmatigheid dus. Men heeft, volgens Belcampo, te maken met twee cultuursystemen, waarvan het tweede het eerste langzamerhand heeft verdrongen… ten koste, voor een deel, van het gevoelsleven, dat onder het eerste systeem ‘gebonden was aan vaststaande en algemeen geldende begrippen’ en daardoor ongekende kracht kon ontplooien; na de overwinning van het tweede systeem blijft de behoefte aan emoties even levend, maar de oude samenhang is verbroken. ‘Voor hen, die weinig aanleg hebben, nieuwe emotiebronnen aan te boren, beteekent het doordringen van het tweede wereldsysteem de vernietiging van hun gevoelsleven, waartegen zij zich natuurlijk met hand en tand zullen verzetten; daarom blijven zij het eerste systeem trouw, uitsluitend om de emotioneele waarde ervan.’

De systeemverdeling, die Belcampo hier misschien vakphilosophisch gesproken niet netjes genoeg, maar overigens zeer plastisch verkondigt, is karakteristiek voor zijn eigen positie. Hij moet leven in een wereld, die de wet van oorzaak en gevolg erkent; hij kan bovendien niet vasthouden aan het eerste systeem, dat slechts op overeenkomst van indrukken berust, omdat hij geen reactionnair is; dus tracht hij kracht te ontplooien, door beide systemen tegen elkaar uit te spelen. Dat is zijn fantasie, dat is ook zijn humor.

Menno ter Braak over Belcampo

Menno ter Braak, ‘Onpolitieke reis’ In: Verzameld werk. Deel 7 (1951)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Belcampo, Menno ter Braak

Ton van Reen

EEN NOG SCHONERE SCHIJN VAN WITHEID

Een winterverhaal

2

“Er was eens een meisje dat haar moeder nooit wilde helpen met de was ophangen of op de bleek leggen,” herhaalde grootmoeder. “Niet dat ze er te lui voor was, maar ze vond al dat gedoe van de was koken met Reckits Blauw voor een nog schonere schijn van witheid, het drogen aan de waslijn of op de bleek, waar de lakens lagen uitgespreid met vier roestige bakstenen op de hoeken om de wind voor de gek te houden, en het strijken met het strijkijzer vol gloeiende kooltjes alleen maar verlies van tijd.”

“Dat snap ik, al die wasbeurten is werk voor niks,” zei ik, vol bewondering voor de lange zin die ze zojuist had uitgesproken, waarin ik vier komma’s had geteld. Ik telde altijd de komma’s. Dat was makkelijk, want na elke komma ademde ze even in. Soms maakte ze zinnen die in een boek een paginagroot zouden zijn. Vierentwintig komma’s was de hoogste score. Zo’n lange zin had ik nog nooit gelezen, maar voor haar waren zo’n lange zinnen heel gewoon.

“Ja, vroeger was ze net als jij,” zei grootmoeder vrolijk. “Zij maakte van haar bed ook altijd een holletje, waarin ze hokte met de beesten die haar in haar dromen kwamen bezoeken.”

“Als ze zelf zo goed weet hoe kinderen zijn,” zei ik wat verbaasd, “waarom laat ze dan mijn bed niet met rust? Die lakens waren nog goed.”

“Moeders doen onverklaarbare dingen,” zei grootje. “Misschien willen ze zelf het kind zijn dat ze op schoot hebben. Toen ik nog een moeder was, deed ik ook vreemde dingen hoor. Toen dacht ik ook dat ik de baas was. Dacht je dat ik ooit naar mijn kinderen luisterde? Nee hoor. Zij moesten luisteren naar mij. Nu ik grootmoeder ben, snap ik weer hoe het voelde om kind te zijn. Nu begrijp ik weer dat je de mooiste avonturen van je leven in je bed beleeft.”

“Mijn moeder is gek,” zei ik. “Als mijn bed naar mijn beesten ruikt, haalt ze er de lakens af en moeten ze in de was. Gewoon idioot. En dan moet ik weer helemaal vooraan beginnen met de dieren en de marsmannetjes en de… de – ik heb u nog niet verteld dat ik vannacht van lilliputters heb gedroomd – mijn tent in te lokken. Ze houden niet van schone lakens die stinken naar stijfsel.”

“Precies, zo praatte je moeder vroeger ook,” zei grootje. “Ze was altijd bezig met andere dingen dan de karweitjes die ze moest doen in huis. Ze had veel tijd nodig voor zichzelf. Ze was een trots meisje. Misschien zeg ik dat verkeerd, maar ze was veel bezig met zichzelf. Ze stond vaak in de gang waar de spiegel hing, om naar zichzelf te kijken. Ze was trots op haar mooie gezichtje en haar lange donkere vlechten met strikken. Soms kamde ze uren haar haren.”

“Dat doet ze nog steeds,” zei ik.

“Gelukkig wel,” zei grootje.

Het was oorlog. Moeder bond de strijd aan met de wind die de stijve lakens probeerde weg te blazen in de richting van de boomgaard. Een windvlaag kreeg het witrozige laken van mijn zusje te pakken en hing het, als een verdwaalde grote vlieger, in een van de kale kersenbomen. Ze holde achter de lappen aan die ze, met twintig handen te weinig, onmachtig boven zich hield en die haar naar de bongerd trokken. Moeder greep paniekerig naar de lappen die ze nog een beetje vast had, kijkend naar het verwaaide laken in de boom, dat een beetje naar kersen kleurde omdat het vroeger misschien echt roze was geweest.

wordt vervolgd

Het verhaal Een nog schonere schijn van witheid van Ton van Reen werd uitgegeven op 26 februari 2012 in opdracht van De Bibliotheek Maas en Peel, ter gelegenheid van de heropening van de bibliotheek in Maasbree.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (9)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

3

I know this woman well now, as well, that is to say, as it is possible to know her, and I can now explain many things that long remained incomprehensible to me. Though there is still the risk that the explanation I now offer myself of them may perhaps appear incomprehensible to others. But I offer it to myself and not to others; and I have not the slightest intention of offering it as an excuse for the Nestoroff.

To whom should I excuse her?

I keep away from people who are respectable by profession, as from the plague.

It seems impossible that a person should not enjoy his own wickedness when he practises it with a cold-blooded calculation. But if such unhappiness (and it must be tremendous) exists, I mean that of not being able to enjoy one’s own wickedness, our contempt for such wicked persons, as for all sorts of other unhappiness, may perhaps be conquered, or at least modified, by a certain pity. I speak, so as not to give offence, as a moderately respectable person. But we must,

surely to goodness, admit this fact: that we are all, more or less, wicked; but that we do not enjoy our wickedness, and are unhappy.

Is it possible?

We all of us readily admit our own unhappiness; no one admits his own wickedness; and the former we insist upon regarding as due to no reason or fault of our own; whereas we labour to find a hundred reasons, a hundred excuses and justifications for every trifling act of wickedness that we have committed, whether against other people or against our own conscience.

Would you like me to shew you how we at once rebel, and indignantly deny a wicked action, even when it is undeniable, and when we have undeniably enjoyed it?

The following two incidents have occurred. (This is not a digression, for the Nestoroff has been compared by someone to the beautiful tiger purchased, a few days ago, by the Kosmograph.) The following two incidents, I say, have occurred.

A flock of birds of passage–woodcock and snipe–have alighted to rest for a little after their long flight and to recuperate their strength in the Roman Campagna. They have chosen a bad spot. A snipe, more daring than the rest, says to his comrades:

“You remain here, hidden in this brake. I shall go and explore the country round, and, if I find a better place, I shall call you.”

An engineer friend of yours, of an adventurous spirit, a Fellow of the Geographical Society, has undertaken the mission of going to Africa, I do not exactly know (because you yourself do not know exactly) upon what scientific exploration. He is still a long way from his goal; you have had some news of him; his last letter has left you somewhat alarmed, because in it your friend explained to you the dangers which he was going to face, when he prepared to cross certain distant tracts, savage and deserted.

To-day is Sunday. You rise betimes to go out shooting. You have made all your preparations overnight, promising yourself a great enjoyment. You alight from the train, blithe and happy; off you go over the fresh, green Campagna, a trifle misty still, in search of a good place for the birds of passage. You wait there for half an hour, for an hour; you begin to feel bored and take from your pocket the newspaper you bought when you started, at the station. After a time, you hear what sounds like a flutter of wings in the dense foliage of the wood; you lay down the paper; you go creeping quietly up; you take aim; you fire. Oh, joy! A snipe!

Yes, indeed, a snipe. The very snipe, the explorer, that had left its comrades in the brake.

I know that you do not eat the birds you have shot; you make presents of them to your friends: for you everything consists in this, in the pleasure of killing what you call game.

The day does not promise well. But you, like all sportsmen, are inclined to be superstitious: you believe that reading the newspaper has brought you luck, and you go back to read the newspaper in the place where you left it. On the second page you find the news that your friend the engineer, who went to Africa on behalf of the Geographical Society, while crossing those savage and deserted tracts, has met a tragic end: attacked, torn in pieces and devoured by a wild beast.

As you read with a shudder the account in the newspaper, it never enters your head even remotely to draw any comparison between the wild beast that has killed your friend and yourself, who have killed the snipe, an explorer like him.

And yet such a comparison would be perfectly logical, and, I fear, would give a certain advantage to the beast, since you have killed for pleasure, and without any risk of your being killed yourself; whereas the beast has killed from hunger, that is to say from necessity, and with the risk of being killed by your friend, who must certainly have been armed.

Rhetoric, you say? Ah, yes, my friend; do not be too contemptuous; I admit as much, myself; rhetoric, because we, by the grace of God, are men and not snipe.

The snipe, for his part, without any fear of being rhetorical, might draw the comparison and demand that at least men, who go out shooting for pleasure, should not call the beasts savage.

We, no. We cannot allow the comparison, because on one side we have a man who has killed a beast, and on the other a beast that has killed a man.

At the very utmost, my dear snipe, to make some concession to you, we can say that you were a poor innocent little creature. There! Does that satisfy you? But you are not to infer from this, that our wickedness is therefore the greater; and, above all, you are not to say that, by calling you an innocent little creature and killing you, we have forfeited the right to call the beast savage which, from hunger and not for pleasure, has killed a man.

But when a man, you say, makes himself lower than a beast?

Ah, yes; we must be prepared, certainly, for the consequences of our logic. Often we make a slip, and then heaven only knows where we shall land.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (9)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature