Fleurs du Mal Magazine

J o h a n K u i p e r s

Museum De Pont Tilburg

23 januari tm 14 maart 2010

Vier grote tekeningen uit de afgelopen twee jaar vormen de kern van de expositie van Johan Kuipers (Sneek 1960) in de projectzaal van Museum De Pont. De afmetingen overtreffen ruimschoots die van een ‘gewone’ tekening, maar dat gaat niet ten koste van de intimiteit. Kuipers heeft enorme vellen van 10 meter bij 1,50 – de lengte van een hele rol – met kroontjespen en Oost-Indische inkt betekend.

In For Whom the Bell Tolls is dat met een fijnmazige, celvormige structuur. Zowel qua techniek als structuur vertoont de tekening grote overeenkomst met zijn abstracte schilderijen. De subtiele kleurvelden van Kuipers’ doeken hebben een eigen dynamiek en gelaagdheid. Ze vragen erom van dichtbij te worden bekeken en dan ontvouwt zich een samenspel van talloze afzonderlijke lijnsegmentjes. Ook in de tekening is er de wisselwerking en de spanning tussen detail en geheel. Kleine variaties in toon en lijnvoering trekken de aandacht naar de afzonderlijke cellen die samen het enorme witte vlak in bezit nemen. In de overige tekeningen heeft deze abstracte structuur van dunne lijnen plaatsgemaakt voor het schrift. Hier staat de wisselwerking tussen taal en beeld centraal. Kuipers heeft steeds de tekst van een compleet boek als uitgangspunt genomen: de Max Havelaar van Multatuli, Lolita van Nabokov en het bijbelboek Job. Het is geen toeval dat de weigering om zich te conformeren aan de heersende moraal een centraal thema is in al deze boeken. Kuipers is gefascineerd door het verzet van het individu, dat zich niet laat breken door het besef dat die opstandigheid tot mislukken is gedoemd.

Door de teksten met de hand op te tekenen keert Kuipers terug naar de oorsprong van het manuscript. Tegelijkertijd saboteren de tekeningen het leesproces. De inhoud van de tekst, die zich tijdens het lezen geleidelijk ontvouwt, wijkt hier voor de onmiddellijkheid van het visuele beeld. Het ritme en de ordening van de tekstblokken geven het meterslange patroon een eigen schoonheid. Voor iedere tekening is een ander ordeningsprincipe gehanteerd; ieder ‘boek’ heeft zijn eigen, unieke beeld. In Max leveren de rijen staande en liggende blokken een overzichtelijk, ritmisch patroon op. In Lo is gekozen voor een grilliger opbouw. Nabokovs beroemde roman begint in het midden van het vel. De tekstblokken wentelen zich rondom dat punt en vullen het veld in een kronkelende beweging naar rechts en naar links. In Job heeft de oudtestamentische tekst de vorm van een litanie gekregen. In een fijnzinnig weefsel rijgen de woorden zich aaneen tot zinnen met de lengte van de rol papier, om vervolgens in omgekeerde richting terug te keren naar het begin.

De tekeningen zijn niet alleen het resultaat van een consequent uitgevoerd concept. Het beeld wordt evenzeer bepaald door de toevalligheden van de uitvoering: de verschillen in toon, veroorzaakt door de druk van de hand en de mate van slijtage van de kroontjespen; een onvoorziene vlek of smet; de restruimte die is overgebleven na voltooiing van de tekst. In die ‘oneffenheden’ wordt de handeling van het optekenen en de enorme hoeveelheid tijd die dat in beslag nam, extra voelbaar. Kunstmaken heeft voor Johan Kuipers niets van doen met een snel en op effect belust gebaar, maar alles met de kracht van een zich steeds herhalende handeling. Niet de aard van de handeling maar de volharding en concentratie waarmee deze is uitgevoerd, maken de betekenis en de schoonheid ervan uit. Door hun uitzonderlijk formaat zijn de hier getoonde werken een even symbolische als feitelijke uiting van die kunstopvatting.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive

Anton K. photos:

L i g h t – 6 –

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, Dutch Landscapes

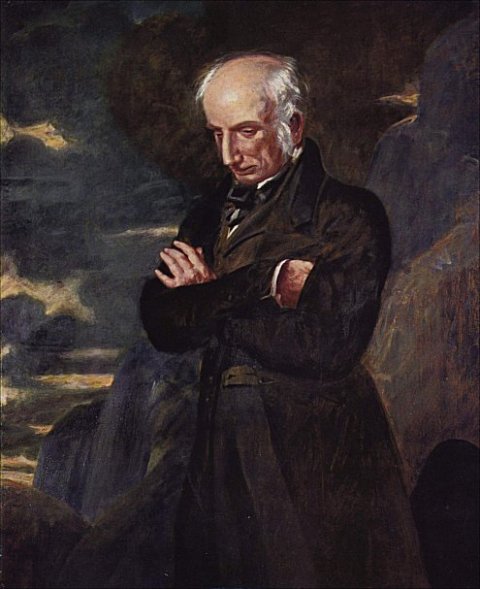

William Wordsworth

(1770-1850)

Among all lovely things my Love had been

Among all lovely things my Love had been;

Had noted well the stars, all flowers that grew

About her home; but she had never seen

A Glow-worm, never one, and this I knew.

While riding near her home one stormy night

A single Glow-worm did I chance to espy;

I gave a fervent welcome to the sight,

And from my Horse I leapt; great joy had I.

Upon a leaf the Glow-worm did I lay,

To bear it with me through the stormy night:

And, as before, it shone without dismay;

Albeit putting forth a fainter light.

When to the Dwelling of my Love I came,

I went into the Orchard quietly;

And left the Glow-worm, blessing it by name,

Laid safely by itself, beneath a Tree.

The whole next day, I hoped, and hoped with fear;

At night the Glow-worm shone beneath the Tree:

I led my Lucy to the spot, "Look here!"

Oh! joy it was for her, and joy for me!

.jpg)

William Wordsworth poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Wordsworth, William

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

An Unwritten Novel

Such an expression of unhappiness was enough by itself to make one’s eyes slide above the paper’s edge to the poor woman’s face insignificant without that look, almost a symbol of human destiny with it. Life’s what you see in people’s eyes; life’s what they learn, and, having learnt it, never, though they seek to hide it, cease to be aware of what? That life’s like that, it seems. Five faces opposite five mature faces and the knowledge in each face. Strange, though, how people want to conceal it! Marks of reticence are on all those faces: lips shut, eyes shaded, each one of the five doing something to hide or stultify his knowledge. One smokes; another reads; a third checks entries in a pocket book; a fourth stares at the map of the line framed opposite; and the fifththe terrible thing about the fifth is that she does nothing at all. She looks at life. Ah, but my poor, unfortunate woman, do play the game do, for all our sakes, conceal it!

As if she heard me, she looked up, shifted slightly in her seat and sighed. She seemed to apologise and at the same time to say to me, “If only you knew!” Then she looked at life again. “But I do know,” I answered silently, glancing at the Times for manners’ sake. “I know the whole business. ‘Peace between Germany and the Allied Powers was yesterday officially ushered in at Paris Signor Nitti, the Italian Prime Minister a passenger train at Doncaster was in collision with a goods train…’ We all know the Times knows but we pretend we don’t.” My eyes had once more crept over the paper’s rim. She shuddered, twitched her arm queerly to the middle of her back and shook her head. Again I dipped into my great reservoir of life. “Take what you like,” I continued, “births, death, marriages, Court Circular, the habits of birds, Leonardo da Vinci, the Sandhills murder, high wages and the cost of living oh, take what you like,” I repeated, “it’s all in the Times!” Again with infinite weariness she moved her head from side to side until, like a top exhausted with spinning, it settled on her neck.

The Times was no protection against such sorrow as hers. But other human beings forbade intercourse. The best thing to do against life was to fold the paper so that it made a perfect square, crisp, thick, impervious even to life. This done, I glanced up quickly, armed with a shield of my own. She pierced through my shield; she gazed into my eyes as if searching any sediment of courage at the depths of them and damping it to clay. Her twitch alone denied all hope, discounted all illusion.

So we rattled through Surrey and across the border into Sussex. But with my eyes upon life I did not see that the other travellers had left, one by one, till, save for the man who read, we were alone together. Here was Three Bridges station. We drew slowly down the platform and stopped. Was he going to leave us? I prayed both ways I prayed last that he might stay. At that instant he roused himself, crumpled his paper contemptuously, like a thing done with, burst open the door, and left us alone.

The unhappy woman, leaning a little forward, palely and colourlessly addressed me talked of stations and holidays, of brothers at Eastbourne, and the time of the year, which was, I forget now, early or late. But at last looking from the window and seeing, I knew, only life, she breathed, “Staying away hat’s the drawback of it” Ah, now we approached the catastrophe, “My sister-in-law” the bitterness of her tone was like lemon on cold steel, and speaking, not to me, but to herself, she muttered, “nonsense, she would say that’s what they all say,” and while she spoke she fidgeted as though the skin on her back were as a plucked fowl’s in a poulterer’s shop-window.

“Oh, that cow!” she broke off nervously, as though the great wooden cow in the meadow had shocked her and saved her from some indiscretion. Then she shuddered, and then she made the awkward, angular movement that I had seen before, as if, after the spasm, some spot between the shoulders burnt or itched. Then again she looked the most unhappy woman in the world, and I once more reproached her, though not with the same conviction, for if there were a reason, and if I knew the reason, the stigma was removed from life.

“Sisters-in-law,” I said

Her lips pursed as if to spit venom at the word; pursed they remained. All she did was to take her glove and rub hard at a spot on the window-pane. She rubbed as if she would rub something out for ever some stain, some indelible contamination. Indeed, the spot remained for all her rubbing, and back she sank with the shudder and the clutch of the arm I had come to expect. Something impelled me to take my glove and rub my window. There, too, was a little speck on the glass. For all my rubbing, it remained. And then the spasm went through me; I crooked my arm and plucked at the middle of my back. My skin, too, felt like the damp chicken’s skin in the poulterer’s shop-window; one spot between the shoulders itched and irritated, felt clammy, felt raw. Could I reach it? Surreptitiously I tried. She saw me. A smile of infinite irony, infinite sorrow, flitted and faded from her face. But she had communicated, shared her secret, passed her poison; she would speak no more. Leaning back in my corner, shielding my eyes from her eyes, seeing only the slopes and hollows, greys and purples, of the winter’s landscape, I read her message, deciphered her secret, reading it beneath her gaze.

Hilda’s the sister-in-law. Hilda? Hilda? Hilda Marsh Hilda the blooming, the full bosomed, the matronly. Hilda stands at the door as the cab draws up, holding a coin. “Poor Minnie, more of a grasshopper than ever old cloak she had last year. Well, well, with two children these days one can’t do more. No, Minnie, I’ve got it; here you are, cabby none of your ways with me. Come in, Minnie. Oh, I could carry you, let alone your basket!” So they go into the dining-room. “Aunt Minnie, children.”

Slowly the knives and forks sink from the upright. Down they get (Bob and Barbara), hold out hands stiffly; back again to their chairs, staring between the resumed mouthfuls. [But this we’ll skip; ornaments, curtains, trefoil china plate, yellow oblongs of cheese, white squares of biscuit skip oh, but wait! Half-way through luncheon one of those shivers; Bob stares at her, spoon in mouth. “Get on with your pudding, Bob;” but Hilda disapproves. “Why should she twitch?” Skip, skip, till we reach the landing on the upper floor; stairs brass-bound; linoleum worn; oh, yes! little bedroom looking out over the roofs of Eastbourne zigzagging roofs like the spines of caterpillars, this way, that way, striped red and yellow, with blue-black slating]. Now, Minnie, the door’s shut; Hilda heavily descends to the basement; you unstrap the straps of your basket, lay on the bed a meagre nightgown, stand side by side furred felt slippers. The looking-glass no, you avoid the looking-glass. Some methodical disposition of hat-pins. Perhaps the shell box has something in it? You shake it; it’s the pearl stud there was last year that’s all. And then the sniff, the sigh, the sitting by the window. Three o’clock on a December afternoon; the rain drizzling; one light low in the skylight of a drapery emporium; another high in a servant’s bedroom this one goes out. That gives her nothing to look at. A moment’s blankness then, what are you thinking? (Let me peep across at her opposite; she’s asleep or pretending it; so what would she think about sitting at the window at three o’clock in the afternoon? Health, money, hills, her God?) Yes, sitting on the very edge of the chair looking over the roofs of Eastbourne, Minnie Marsh prays to God. That’s all very well; and she may rub the pane too, as though to see God better; but what God does she see? Who’s the God of Minnie Marsh, the God of the back streets of Eastbourne, the God of three o’clock in the afternoon? I, too, see roofs, I see sky; but, oh, dear this seeing of Gods! More like President Kruger than Prince Albert that’s the best I can do for him; and I see him on a chair, in a black frock-coat, not so very high up either; I can manage a cloud or two for him to sit on; and then his hand trailing in the clouds holds a rod, a truncheon is it? black, thick, horned a brutal old bully Minnie’s God! Did he send the itch and the patch and the twitch? Is that why she prays? What she rubs on the window is the stain of sin. Oh, she committed some crime!

I have my choice of crimes. The woods flit and fly in summer there are bluebells; in the opening there, when Spring comes, primroses. A parting, was it, twenty years ago? Vows broken? Not Minnie’s!…She was faithful. How she nursed her mother! All her savings on the tombstone wreaths under glass daffodils in jars. But I’m off the track. A crime…They would say she kept her sorrow, suppressed her secret her sex, they’d say the scientific people. But what flummery to saddle her with sex! No more like this. Passing down the streets of Croyden twenty years ago, the violet loops of ribbon in the draper’s window spangled in the electric light catch her eye. She lingers past six. Still by running she can reach home. She pushes through the glass swing door. It’s sale-time. Shallow trays brim with ribbons. She pauses, pulls this, fingers that with the raised roses on it no need to choose, no need to buy, and each tray with its surprises. “We don’t shut till seven,” and then it is seven. She runs, she rushes, home she reaches, but too late. Neighbours the doctor baby brother the kettle scalded hospital dead or only the shock of it, the blame? Ah, but the detail matters nothing! It’s what she carries with her; the spot, the crime, the thing to expiate, always there between her shoulders. “Yes,” she seems to nod to me, “it’s the thing I did.”

Whether you did, or what you did, I don’t mind; it’s not the thing I want. The draper’s window looped with violet that’ll do; a little cheap perhaps, a little commonplace since one has a choice of crimes, but then so many (let me peep across again still sleeping, or pretending to sleep! white, worn, the mouth closed a touch of obstinacy, more than one would thin no hint of sex) so many crimes aren’t your crime; your crime was cheap; only the retribution solemn; for now the church door opens, the hard wooden pew receives her; on the brown tiles she kneels; every day, winter, summer, dusk, dawn (here she’s at it) prays. All her sins fall, fall, for ever fall. The spot receives them. It’s raised, it’s red, it’s burning. Next she twitches. Small boys point. “Bob at lunch to-day” But elderly women are the worst.

Indeed now you can’t sit praying any longer. Kruger’s sunk beneath the cloud washed over as with a painter’s brush of liquid grey, to which he adds a tinge of black even the tip of the truncheon gone now. That’s what always happens! Just as you’ve seen him, felt him, someone interrupts. It’s Hilda now.

How you hate her! She’ll even lock the bathroom door overnight, too, though it’s only cold water you want, and sometimes when the night’s been bad it seems as if washing helped. And John at breakfast the children meals are worst, and sometimes there are friends ferns don’t altogether hide ’em they guess, too; so out you go along the front, where the waves are grey, and the papers blow, and the glass shelters green and draughty, and the chairs cost tuppence too much for there must be preachers along the sands. Ah, that’s a nigger that’s a funny man that’s a man with parakeets poor little creatures! Is there no one here who thinks of God? just up there, over the pier, with his rod but no here’s nothing but grey in the sky or if it’s blue the white clouds hide him, and the music it’s military music and what are they fishing for? Do they catch them? How the children stare! Well, then home a back way”Home a back way!” The words have meaning; might have been spoken by the old man with whisker no, no, he didn’t really speak; but everything has meaning placards leaning against doorways names above shop-windows red fruit in baskets women’s heads in the hairdresser’ all say “Minnie Marsh!” But here’s a jerk. “Eggs are cheaper!” That’s what always happens! I was heading her over the waterfall, straight for madness, when, like a flock of dream sheep, she turns t’other way and runs between my fingers. Eggs are cheaper. Tethered to the shores of the world, none of the crimes, sorrows, rhapsodies, or insanities for poor Minnie Marsh; never late for luncheon; never caught in a storm without a mackintosh; never utterly unconscious of the cheapness of eggs. So she reaches home rapes her boots.

Have I read you right? But the human face the human face at the top of the fullest sheet of print holds more, withholds more. Now, eyes open, she looks out; and in the human eye how d’you define it? there’s a break a division so that when you’ve grasped the stem the butterfly’s off the moth that hangs in the evening over the yellow flower move, raise your hand, off, high, away. I won’t raise my hand. Hang still, then, quiver, life, soul, spirit, whatever you are of Minnie Marsh I, too, on my flower the hawk over the down alone, or what were the worth of life? To rise; hang still in the evening, in the midday; hang still over the down. The flicker of a hand off, up! then poised again. Alone, unseen; seeing all so still down there, all so lovely. None seeing, none caring. The eyes of others our prisons; their thoughts our cages. Air above, air below. And the moon and immortality…Oh, but I drop to the turf! Are you down too, you in the corner, what’s your name woman Minnie Marsh; some such name as that? There she is, tight to her blossom; opening her hand-bag, from which she takes a hollow shell an egg who was saying that eggs were cheaper? You or I? Oh, it was you who said it on the way home, you remember, when the old gentleman, suddenly opening his umbrella or sneezing was it? Anyhow, Kruger went, and you came “home a back way,” and scraped your boots. Yes. And now you lay across your knees a pocket-handkerchief into which drop little angular fragments of eggshell fragments of a map a puzzle. I wish I could piece them together! If you would only sit still. She’s moved her knees the map’s in bits again. Down the slopes of the Andes the white blocks of marble go bounding and hurtling, crushing to death a whole troop of Spanish muleteers, with their convoy Drake’s booty, gold and silver. But to return

To what, to where? She opened the door, and, putting her umbrella in the stand that goes without saying; so, too, the whiff of beef from the basement; dot, dot, dot. But what I cannot thus eliminate, what I must, head down, eyes shut, with the courage of a battalion and the blindness of a bull, charge and disperse are, indubitably, the figures behind the ferns, commercial travellers. There I’ve hidden them all this time in the hope that somehow they’d disappear, or better still emerge, as indeed they must, if the story’s to go on gathering richness and rotundity, destiny and tragedy, as stories should, rolling along with it two, if not three, commercial travellers and a whole grove of aspidistra. “The fronds of the aspidistra only partly concealed the commercial traveller” Rhododendrons would conceal him utterly, and into the bargain give me my fling of red and white, for which I starve and strive; but rhododendrons in Eastbourne in December on the Marshes’ table no, no, I dare not; it’s all a matter of crusts and cruets, frills and ferns. Perhaps there’ll be a moment later by the sea. Moreover, I feel, pleasantly pricking through the green fretwork and over the glacis of cut glass, a desire to peer and peep at the man opposite one’s as much as I can manage. James Moggridge is it, whom the Marshes call Jimmy? [Minnie, you must promise not to twitch till I’ve got this straight]. James Moggridge travels in shall we say buttons? but the time’s not come for bringing them in the big and the little on the long cards, some peacock-eyed, others dull gold; cairngorms some, and others coral sprays but I say the time’s not come. He travels, and on Thursdays, his Eastbourne day, takes his meals with the Marshes. His red face, his little steady eyes by no means altogether commonplac his enormous appetite (that’s safe; he won’t look at Minnie till the bread’s swamped the gravy dry), napkin tucked diamond-wise but this is primitive, and whatever it may do the reader, don’t take me in. Let’s dodge to the Moggridge household, set that in motion. Well, the family boots are mended on Sundays by James himself. He reads Truth. But his passion? Rose and his wife a retired hospital nurse interesting for God’s sake let me have one woman with a name I like! But no; she’s of the unborn children of the mind, illicit, none the less loved, like my rhododendrons. How many die in every novel that’s written the best, the dearest, while Moggridge lives. It’s life’s fault. Here’s Minnie eating her egg at the moment opposite and at t’other end of the line are we past Lewes? there must be Jimmy or what’s her twitch for?

There must be Moggridge life’s fault. Life imposes her laws; life blocks the way; life’s behind the fern; life’s the tyrant; oh, but not the bully! No, for I assure you I come willingly; I come wooed by Heaven knows what compulsion across ferns and cruets, tables splashed and bottles smeared. I come irresistibly to lodge myself somewhere on the firm flesh, in the robust spine, wherever I can penetrate or find foothold on the person, in the soul, of Moggridge the man. The enormous stability of the fabric; the spine tough as whalebone, straight as oak-tree; the ribs radiating branches; the flesh taut tarpaulin; the red hollows; the suck and regurgitation of the heart; while from above meat falls in brown cubes and beer gushes to be churned to blood again and so we reach the eyes. Behind the aspidistra they see something; black, white, dismal; now the plate again; behind the aspidistra they see elderly woman; “Marsh’s sister, Hilda’s more my sort;” the tablecloth now. “Marsh would know what’s wrong with Morrises…” talk that over; cheese has come; the plate again; turn it round the enormous fingers; now the woman opposite. “Marsh’s sister not a bit like Marsh; wretched, elderly female….You should feed your hens….God’s truth, what’s set her twitching? Not what I said? Dear, dear, dear! These elderly women. Dear, dear!”

[Yes, Minnie; I know you’ve twitched, but one moment James Moggridge].

“Dear, dear, dear!” How beautiful the sound is! like the knock of a mallet on seasoned timber, like the throb of the heart of an ancient whaler when the seas press thick and the green is clouded. “Dear, dear!” what a passing bell for the souls of the fretful to soothe them and solace them, lap them in linen, saying, “So long. Good luck to you!” and then, “What’s your pleasure?” for though Moggridge would pluck his rose for her, that’s done, that’s over. Now what’s the next thing? “Madam, you’ll miss your train,” for they don’t linger.

That’s the man’s way; that’s the sound that reverberates; that’s St. Paul’s and the motor-omnibuses. But we’re brushing the crumbs off. Oh, Moggridge, you won’t stay? You must be off? Are you driving through Eastbourne this afternoon in one of those little carriages? Are you the man who’s walled up in green cardboard boxes, and sometimes has the blinds down, and sometimes sits so solemn staring like a sphinx, and always there’s a look of the sepulchral, something of the undertaker, the coffin, and the dusk about horse and driver? Do tell me but the doors slammed. We shall never meet again. Moggridge, farewell!

Yes, yes, I’m coming. Right up to the top of the house. One moment I’ll linger. How the mud goes round in the mind what a swirl these monsters leave, the waters rocking, the weeds waving and green here, black there, striking to the sand, till by degrees the atoms reassemble, the deposit sifts itself, and again through the eyes one sees clear and still, and there comes to the lips some prayer for the departed, some obsequy for the souls of those one nods to, the people one never meets again.

James Moggridge is dead now, gone for ever. Well, Minnie”I can face it no longer.” If she said that (Let me look at her. She is brushing the eggshell into deep declivities). She said it certainly, leaning against the wall of the bedroom, and plucking at the little balls which edge the claret-coloured curtain. But when the self speaks to the self, who is speaking? the entombed soul, the spirit driven in, in, in to the central catacomb; the self that took the veil and left the world a coward perhaps, yet somehow beautiful, as it flits with its lantern restlessly up and down the dark corridors. “I can bear it no longer,” her spirit says. “That man at lunch Hilda the children.” Oh, heavens, her sob! It’s the spirit wailing its destiny, the spirit driven hither, thither, lodging on the diminishing carpets meagre footholds shrunken shreds of all the vanishing universe love, life, faith, husband, children, I know not what splendours and pageantries glimpsed in girlhood. “Not for me not for me.”

But then the muffins, the bald elderly dog? Bead mats I should fancy and the consolation of underlinen. If Minnie Marsh were run over and taken to hospital, nurses and doctors themselves would exclaim….There’s the vista and the vision there’s the distance the blue blot at the end of the avenue, while, after all, the tea is rich, the muffin hot, and the dog “Benny, to your basket, sir, and see what mother’s brought you!” So, taking the glove with the worn thumb, defying once more the encroaching demon of what’s called going in holes, you renew the fortifications, threading the grey wool, running it in and out.

Running it in and out, across and over, spinning a web through which God himself hush, don’t think of God! How firm the stitches are! You must be proud of your darning. Let nothing disturb her. Let the light fall gently, and the clouds show an inner vest of the first green leaf. Let the sparrow perch on the twig and shake the raindrop hanging to the twig’s elbow…. Why look up? Was it a sound, a thought? Oh, heavens! Back again to the thing you did, the plate glass with the violet loops? But Hilda will come. Ignominies, humiliations, oh! Close the breach.

Having mended her glove, Minnie Marsh lays it in the drawer. She shuts the drawer with decision. I catch sight of her face in the glass. Lips are pursed. Chin held high. Next she laces her shoes. Then she touches her throat. What’s your brooch? Mistletoe or merry-thought? And what is happening? Unless I’m much mistaken, the pulse’s quickened, the moment’s coming, the threads are racing, Niagara’s ahead. Here’s the crisis! Heaven be with you! Down she goes. Courage, courage! Face it, be it! For God’s sake don’t wait on the mat now! There’s the door! I’m on your side. Speak! Confront her, confound her soul!

“Oh, I beg your pardon! Yes, this is Eastbourne. I’ll reach it down for you. Let me try the handle.” [But, Minnie, though we keep up pretences, I’ve read you right I’m with you now].

“That’s all your luggage?”

“Much obliged, I’m sure.”

(But why do you look about you? Hilda won’t come to the station, nor John; and Moggridge is driving at the far side of Eastbourne).

“I’ll wait by my bag, ma’am, that’s safest. He said he’d meet me….Oh, there he is! That’s my son.”

So they walked off together.

Well, but I’m confounded….Surely, Minnie, you know better! A strange young man….Stop! I’ll tell him Minnie! Miss Marsh! I don’t know though. There’s something queer in her cloak as it blows. Oh, but it’s untrue; it’s indecent….Look how he bends as they reach the gateway. She finds her ticket. What’s the joke? Off they go, down the road, side by side….Well, my world’s done for! What do I stand on? What do I know? That’s not Minnie. There never was Moggridge. Who am I? Life’s bare as bone.

And yet the last look of them he stepping from the kerb and she following him round the edge of the big building brims me with wonder floods me anew. Mysterious figures! Mother and son. Who are you? Why do you walk down the street? Where to-night will you sleep, and then, to-morrow? Oh, how it whirls and surges floats me afresh! I start after them. People drive this way and that. The white light splutters and pours. Plate-glass windows. Carnations; chrysanthemums. Ivy in dark gardens. Milk carts at the door. Wherever I go, mysterious figures, I see you, turning the corner, mothers and sons; you, you, you. I hasten, I follow. This, I fancy, must be the sea. Grey is the landscape; dim as ashes; the water murmurs and moves. If I fall on my knees, if I go through the ritual, the ancient antics, it’s you, unknown figures, you I adore; if I open my arms, it’s you I embrace, you I draw to me adorable world!

Virginia Woolf: An unwritten novel

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

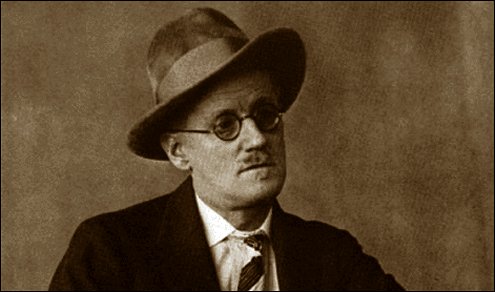

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

The Ballad of Persse O’Reilly

Have you heard of one Humpty Dumpty

How he fell with a roll and a rumble

And curled up like Lord Olofa Crumple

By the butt of the Magazine Wall,

(Chorus) Of the Magazine Wall,

Hump, helmet and all?

He was one time our King of the Castle

Now he’s kicked about like a rotten old parsnip.

And from Green street he’ll be sent by order of His Worship

To the penal jail of Mountjoy

(Chorus) To the jail of Mountjoy!

Jail him and joy.

He was fafafather of all schemes for to bother us

Slow coaches and immaculate contraceptives for the populace,

Mare’s milk for the sick, seven dry Sundays a week,

Openair love and religion’s reform,

(Chorus) And religious reform,

Hideous in form.

Arrah, why, says you, couldn’t he manage it?

I’ll go bail, my fine dairyman darling,

Like the bumping bull of the Cassidys

All your butter is in your horns.

(Chorus) His butter is in his horns.

Butter his horns!

(Repeat) Hurrah there, Hosty, frosty Hosty, change that shirt

on ye,

Rhyme the rann, the king of all ranns!

Balbaccio, balbuccio!

We had chaw chaw chops, chairs, chewing gum, the chicken-pox

and china chambers

Universally provided by this soffsoaping salesman.

Small wonder He’ll Cheat E’erawan our local lads nicknamed him.

When Chimpden first took the floor

(Chorus) With his bucketshop store

Down Bargainweg, Lower.

So snug he was in his hotel premises sumptuous

But soon we’ll bonfire all his trash, tricks and trumpery

And ’tis short till sheriff Clancy’ll be winding up his unlimited

company

With the bailiff’s bom at the door,

(Chorus) Bimbam at the door.

Then he’ll bum no more.

Sweet bad luck on the waves washed to our island

The hooker of that hammerfast viking

And Gall’s curse on the day when Eblana bay

Saw his black and tan man-o’-war.

(Chorus) Saw his man-o’-war

On the harbour bar.

Where from? roars Poolbeg. Cookingha’pence, he bawls

Donnez-moi scampitle, wick an wipin’fampiny

Fingal Mac Oscar Onesine Bargearse Boniface

Thok’s min gammelhole Norveegickers moniker

Og as ay are at gammelhore Norveegickers cod.

(Chorus) A Norwegian camel old cod.

He is, begod.

Lift it, Hosty, lift it, ye devil, ye! up with the rann,

the rhyming rann!

It was during some fresh water garden pumping

Or, according to the Nursing Mirror, while admiring the monkeys

That our heavyweight heathen Humpharey

Made bold a maid to woo

(Chorus) Woohoo, what’ll she doo!

The general lost her maidenloo!

He ought to blush for himself, the old hayheaded philosopher,

For to go and shove himself that way on top of her.

Begob, he’s the crux of the catalogue

Of our antediluvial zoo,

(Chorus) Messrs Billing and Coo.

Noah’s larks, good as noo.

He was joulting by Wellinton’s monument

Our rotorious hippopopotamuns

When some bugger let down the backtrap of the omnibus

And he caught his death of fusiliers,

(Chorus) With his rent in his rears.

Give him six years.

‘Tis sore pity for his innocent poor children

But look out for his missus legitimate!

When that frew gets a grip of old Earwicker

Won’t there be earwigs on the green?

(Chorus) Big earwigs on the green,

The largest ever you seen.

Suffoclose! Shikespower! Seudodanto! Anonymoses!

Then we’ll have a free trade Gael’s band and mass meeting

For to sod him the brave son of Scandiknavery.

And we’ll bury him down in Oxmanstown

Along with the devil and the Danes,

(Chorus) With the deaf and dumb Danes,

And all their remains.

And not all the king’s men nor his horses

Will resurrect his corpus

For there’s no true spell in Connacht or hell

(bis) That’s able to raise a Cain.

James Joyce poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Joyce, James

Paul Verlaine

(1844-1896)

Trois Poèmes

A Charles Baudelaire

Je ne t’ai pas connu, je ne t’ai pas aimé,

Je ne te connais point et je t’aime encor moins :

Je me chargerais mal de ton nom diffamé,

Et si j’ai quelque droit d’être entre tes témoins,

C’est que, d’abord, et c’est qu’ailleurs, vers les Pieds joints

D’abord par les clous froids, puis par l’élan pâmé

Des femmes de péché – desquelles ô tant oints,

Tant baisés, chrême fol et baiser affamé ! –

Tu tombas, tu prias, comme moi, comme toutes

Les âmes que la faim et la soif sur les routes

Poussaient belles d’espoir au Calvaire touché !

– Calvaire juste et vrai, Calvaire où, donc, ces doutes,

Ci, çà, grimaces, art, pleurent de leurs déroutes.

Hein ? mourir simplement, nous, hommes de péché.

Child wife

Vous n’avez rien compris à ma simplicité,

Rien, ô ma pauvre enfant !

Et c’est avec un front éventé, dépité

Que vous fuyez devant.

Vos yeux qui ne devaient refléter que douceur,

Pauvre cher bleu miroir

Ont pris un ton de fiel, ô lamentable soeur,

Qui nous fait mal à voir.

Et vous gesticulez avec vos petits bras

Comme un héros méchant,

En poussant d’aigres cris poitrinaires, hélas !

Vous qui n’étiez que chant !

Car vous avez eu peur de l’orage et du coeur

Qui grondait et sifflait,

Et vous bêlâtes vers votre mère – ô douleur ! –

Comme un triste agnelet.

Et vous n’aurez pas su la lumière et l’honneur

D’un amour brave et fort,

Joyeux dans le malheur, grave dans le bonheur,

Jeune jusqu’à la mort !

Lamento

La ville dresse ses hauts toits

Aux mille dentelures folles.

Un bruit de joyeuses paroles.

Monte au ciel, rassurante voix.

– Que me fait cette gaieté vile

De la ville !

Quelle paix vaste règne aux champs !

L’oiseau chante dans le grand chêne,

Les midis font blanche la plaine

Que dorent les soleils couchants.

– Peu m’importe ta gloire pure,

Ô nature !

Avec les signes de ses flots,

Avec sa plainte solennelle,

La mer immense nous appelle,

Nous tous, rêveurs et matelots.

– Qu’est-ce que tu me veux encore,

Mer sonore ?

– Ah ! ni les flots des Océans,

Ni les campagnes et leur ombre,

Ni les cités aux bruits sans nombre,

Qu’édifièrent des géants,

Rien ne réveillera ma mie

Tant endormie.

Paul Verlaine: Trois Poèmes

KEMP=MAG – kempis poetry magazine

More in: Verlaine, Paul

Robert Browning

(1812-1889)

Meeting at Night

The gray sea and the long black land;

And the yellow half-moon large and low;

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow,

And quench its speed i’ the slushy sand.

Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each!

Parting at Morning

Round the cape of a sudden came the sea,

And the sun looked over the mountain’s rim;

And straight was a path of gold for him,

And the need of a world of men for me.

My Star

All that I know

Of a certain star

Is, it can throw

(Like the angled spar)

Now a dart of red,

Now a dart of blue;

Till my friends have said

They would fain see, too,

My star that dartles the red and the blue!

Then it stops like a bird; like a flower, hangs furled:

They must solace themselves with the Saturn above it.

What matter to me if their star is a world?

Mine has opened its soul to me; therefore I love it.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Browning, Robert

Georg Trakl

(1887-1914)

Dichtungen und Briefe

Verlassenheit

Nichts unterbricht mehr das Schweigen der Verlassenheit. Über den dunklen, uralten Gipfeln der Bäume ziehn die Wolken hin und spiegeln sich in den grünlich-blauen Wassern des Teiches, der abgründlich scheint. Und unbeweglich, wie in trauervolle Ergebenheit versunken, ruht die Oberfläche – tagein, tagaus.

Inmitten des schweigsamen Teiches ragt das Schloß zu den Wolken empor mit spitzen, zerschlissenen Türmen und Dächern. Unkraut wuchert über die schwarzen, geborstenen Mauern, und an den runden, blinden Fenstern prallt das Sonnenlicht ab. In den düsteren, dunklen Höfen fliegen Tauben umher und suchen sich in den Ritzen des Gemäuers ein Versteck.

Sie scheinen immer etwas zu befürchten, denn sie fliegen scheu und hastend an den Fenstern hin. Drunten im Hof plätschert die Fontäne leise und fein. Aus bronzener Brunnenschale trinken dann und wann die dürstenden Tauben.

Durch die schmalen, verstaubten Gänge des Schlosses streift manchmal ein dumpfer Fieberhauch, daß die Fledermäuse erschreckt aufflattern. Sonst stört nichts die tiefe Ruhe.

Die Gemächer aber sind schwarz verstaubt! Hoch und kahl und frostig und voll erstorbener Gegenstände. Durch die blinden Fenster kommt bisweilen ein kleiner, winziger Schein, den das Dunkel wieder aufsaugt. Hier ist die Vergangenheit gestorben.

Hier ist sie eines Tages erstarrt in einer einzigen, verzerrten Rose. An ihrer Wesenlosigkeit geht die Zeit achtlos vorüber.

Und alles durchdringt das Schweigen der Verlassenheit.

Niemand vermag mehr in den Park einzudringen. Die Äste der Bäume halten sich tausendfach umschlungen, der ganze Park ist nur mehr ein einziges, gigantisches Lebewesen.

Und ewige Nacht lastet unter dem riesigen Blätterdach. Und tiefes Schweigen! Und die Luft ist durchtränkt von Vermoderungsdünsten!

Manchmal aber erwacht der Park aus schweren Träumen. Dann strömt er ein Erinnern aus an kühle Sternennächte, an tief verborgene heimliche Stellen, da er fiebernde Küsse und Umarmungen belauschte, an Sommernächte, voll glühender Pracht und Herrlichkeit, da der Mond wirre Bilder auf den schwarzen Grund zauberte, an Menschen, die zierlich galant voll rhythmischer Bewegungen unter seinem Blätterdache dahinwandelten, die sich süße, verrückte Worte zuraunten, mit feinem verheißenden Lächeln.

Und dann versinkt der Park wieder in seinen Todesschlaf.

Auf den Wassern wiegen sich die Schatten von Blutbuchen und Tannen und aus der Tiefe des Teiches kommt ein dumpfes, trauriges Murmeln.

Schwäne ziehen durch die glänzenden Fluten, langsam, unbeweglich, starr ihre schlanken Hälse emporrichtend. Sie ziehen dahin! Rund um das erstorbene Schloß! Tagein, tagaus!

Bleiche Lilien stehen am Rande des Teiches mitten unter grellfarbigen Gräsern. Und ihre Schatten im Wasser sind bleicher als sie selbst.

Und wenn die einen dahinsterben, kommen andere aus der Tiefe. Und sie sind wie kleine, tote Frauenhände.

Große Fische umschwimmen neugierig, mit starren, glasigen Augen die bleichen Blumen, und tauchen dann wieder in die Tiefe – lautlos!

Und alles durchdringt das Schweigen der Verlassenheit.

Und droben in einem rissigen Turmgemach sitzt der Graf. Tagein, tagaus.

Er sieht den Wolken nach, die über den Gipfeln der Bäume hinziehen, leuchtend und rein. Er sieht es gern, wenn die Sonne in den Wolken glüht, am Abend, da sie untersinkt. Er horcht auf die Geräusche in den Höhen: auf den Schrei eines Vogels, der am Turm vorbeifliegt oder auf das tönende Brausen des Windes, wenn er das Schloß umfegt.

Er sieht wie der Park schläft, dumpf und schwer, und sieht die Schwäne durch die glitzernden Fluten ziehn – die das Schloß umschwimmen. Tagein! Tagaus!

Und die Wasser schimmern grünlich-blau. In den Wassern aber spiegeln sich die Wolken, die über das Schloß hinziehen; und ihre Schatten in den Fluten leuchten strahlend und rein, wie sie selbst. Die Wasserlilien winken ihm zu, wie kleine, tote Frauenhände, und wiegen sich nach den leisen Tönen des Windes, traurig träumerisch.

Auf alles, was ihn da sterbend umgibt, blickt der arme Graf, wie ein kleines, irres Kind, über dem ein Verhängnis steht, und das nicht mehr Kraft hat, zu leben, das dahinschwindet, gleich einem Vormittagsschatten.

Er horcht nur mehr auf die kleine, traurige Melodie seiner Seele: Vergangenheit!

Wenn es Abend wird, zündet er seine alte, verrußte Lampe an und liest in mächtigen, vergilbten Büchern von der Vergangenheit Größe und Herrlichkeit.

Er liest mit fieberndem, tönendem Herzen, bis die Gegenwart, der er nicht angehört, versinkt. Und die Schatten der Vergangenheit steigen herauf – riesengroß. Und er lebt das Leben, das herrlich schöne Leben seiner Väter.

In Nächten, da der Sturm um den Turm jagt, daß die Mauern in ihren Grundfesten dröhnen und die Vögel angstvoll vor seinem Fenster kreischen, überkommt den Grafen eine namenlose Traurigkeit.

Auf seiner jahrhundertalten, müden Seele lastet das Verhängnis. Und er drückt das Gesicht an das Fenster und sieht in die Nacht hinaus. Und da erscheint ihm alles riesengroß traumhaft, gespensterlich! Und schrecklich. Durch das Schloß hört er den Sturm rasen, als wollte er alles Tote hinausfegen und in Lüfte zerstreuen.

Doch wenn das verworrene Trugbild der Nacht dahinsinkt wie ein heraufbeschworener Schatten – durchdringt alles wieder das Schweigen der Verlassenheit.

Georg Trakl: Dichtungen und Briefe

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Trakl, Georg

.jpg)

Op donderdag 28 januari zal de eerste Kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg officieel worden benoemd. Op Gedichtendag 2010 wordt tijdens een bijeenkomst in de Bibliotheek bekendgemaakt wie deze functie anderhalf jaar lang mag bekleden.

Alle kinderen tot 14 jaar uit Tilburg en omstreken konden meedoen aan de Kinderstadsdichtwedstrijd met als thema: ik schrijf – mijn stad. De organisatie mocht zestien inzendingen ontvangen. De winnaar wordt de Kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg tot augustus 2011.

Iedereen is welkom om de benoeming van de Kinderstadsdichter te vieren. Het precieze programma volgt binnenkort. In ieder geval zal de kersverse Kinderstadsdichter zijn of haar winnende gedicht voordragen en zal dichter Ienne Biemans uit haar werk voorlezen.

Wanneer: Donderdag 28 januari

Waar: Bibliotheek (Tilburg, Koningsplein)

Aanvang: 16:00 uur

De verkiezing van Kinderstadsdichter wordt georganiseerd door Stichting Dr. P.J. Cools, Cultuurconcepten.nl en Bibliotheek Midden-Brabant.

.jpg)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: City Poets / Stadsdichters, Kinderstadsdichters / Children City Poets

.jpg)

Anton K. photos:

L i g h t – 5 –

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, Dutch Landscapes

.jpg)

W i l l e m B i l d e r d i j k

(1756-1831)

Nagedachtenis van mijn’ Zoontjen Ursinus,

door een heimlijk ingegeven slaapmiddel

omgebracht

Ecce lacertis

Viscera nostra tenens animamque aveltitur infans.

Schoon stem en cyther zweeg, nog daalt ge, ô dierbaar Wichtjen,

Niet onvereerd in ’t graf, geheiligd door uw’ naam.

Die enkle naam is meer dan ’t sierlijkst lijkgestichtjen,

Dan ’t sleepend rouwgebaar van duizend Dichters saam

Ach! hadt ge in ’s levens bloei hem waardig mogen dragen,

Hoe heerlijk had mijn stam in beî mijn Zoon herbloeid!

Reeds vonkte u ’t roemrijk bloed van uw beroemde Magen

In ’t schittrend oogjen uit, van zeldzam vuur doorgloeid.

Dan, anders was de wil van ’t heilig Alvermogen!

Hy doemde de aard ten prooi’ aan ’t onrecht, aan ’t geweld.

Wat zoudt ge op eene aard — ? Van d’afgrond aangespogen

Verwelken onder ’t leed, dat Oudren deugd vergeldt ? —

Neen, de Almacht wilde u nooit uw leven doen beschreien :

Een lachjen, de onschuld waard van Edens paradijs,

Bestempelde u reeds vroeg voor ’s Hemels Englenreien:

En strekte op ’t lief gelaat uw roeping tot bewijs.

Welaan aan, dierbre telg, my niet van ’t hart te scheuren,

Dan bloedende aan een wond die nimmer heeling duldt:

Ik derf u! ’k voel dien slag; maar ’k zal hem niet betreuren!

Eén oogenblik op de aard heeft al uw leed vervuld.

Een oogenblik — ? De moord, met Godvergeten handen,

Verraste u in uw wieg — en ik — ik ben getroost?

Een doodlijk moordvenijn verscheurde uw ingewanden —

En ik — ik leve en zwijg by mijn mishandeld kroost? —

ô God, Gy zaagt me op ’t punt… Gy hebt mijn’ arm weêrhouen

Gy spraakt —: de nevel vlood, ik zag uw raadsbesluit,

Aanbidlijk, wijs, en goed : — en, zalig in ’t aanschouwen,

Verloochende ik de wraak, en loofde U in mijn spruit.

Ja, ’k offerde. U dit kind, blijmoedig, zonder weenen!

Ach, neem de rest van ’t bloed dat door mijne aadren vloeit

Maar wil, weldadig God! my deze beê verleenen:

Geef, dat me in ’t oovrig kroost een waardig Nakroost bloeit!

’s Gravenhage 1794

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Bilderdijk, Willem

.jpg)

Anne Brontë

(1820-1849)

Stanzas

Oh, weep not, love! each tear that springs

In those dear eyes of thine,

To me a keener suffering brings

Than if they flowed from mine.

And do not droop! however drear

The fate awaiting thee;

For MY sake combat pain and care,

And cherish life for me!

I do not fear thy love will fail;

Thy faith is true, I know;

But, oh, my love! thy strength is frail

For such a life of woe.

Were ‘t not for this, I well could trace

(Though banished long from thee)

Life’s rugged path, and boldly face

The storms that threaten me.

Fear not for me–I’ve steeled my mind

Sorrow and strife to greet;

Joy with my love I leave behind,

Care with my friends I meet.

A mother’s sad reproachful eye,

A father’s scowling brow–

But he may frown and she may sigh:

I will not break my vow!

I love my mother, I revere

My sire, but fear not me–

Believe that Death alone can tear

This faithful heart from thee.

If this be all

O God! if this indeed be all

That Life can show to me;

If on my aching brow may fall

No freshening dew from Thee;

If with no brighter light than this

The lamp of hope may glow,

And I may only dream of bliss,

And wake to weary woe;

If friendship’s solace must decay,

When other joys are gone,

And love must keep so far away,

While I go wandering on,–

Wandering and toiling without gain,

The slave of others’ will,

With constant care, and frequent pain,

Despised, forgotten still;

Grieving to look on vice and sin,

Yet powerless to quell

The silent current from within,

The outward torrent’s swell

While all the good I would impart,

The feelings I would share,

Are driven backward to my heart,

And turned to wormwood there;

If clouds must EVER keep from sight

The glories of the Sun,

And I must suffer Winter’s blight,

Ere Summer is begun;

If Life must be so full of care,

Then call me soon to thee;

Or give me strength enough to bear

My load of misery.

Home

How brightly glistening in the sun

The woodland ivy plays!

While yonder beeches from their barks

Reflect his silver rays.

That sun surveys a lovely scene

From softly smiling skies;

And wildly through unnumbered trees

The wind of winter sighs:

Now loud, it thunders o’er my head,

And now in distance dies.

But give me back my barren hills

Where colder breezes rise;

Where scarce the scattered, stunted trees

Can yield an answering swell,

But where a wilderness of heath

Returns the sound as well.

For yonder garden, fair and wide,

With groves of evergreen,

Long winding walks, and borders trim,

And velvet lawns between;

Restore to me that little spot,

With gray walls compassed round,

Where knotted grass neglected lies,

And weeds usurp the ground.

Though all around this mansion high

Invites the foot to roam,

And though its halls are fair within–

Oh, give me back my HOME!

Anne Brontë poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anne, Emily & Charlotte Brontë, Brontë, Anne, Emily & Charlotte

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature