Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

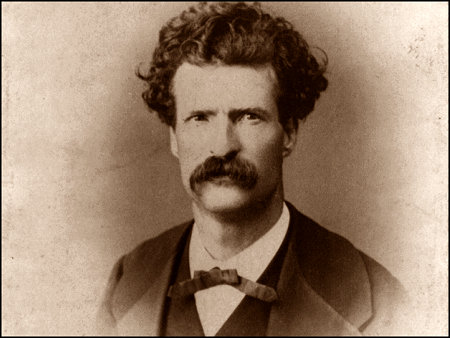

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

An Entertaining Article

I take the following paragraph from an article in the Boston Advertiser:

“Perhaps the most successful flights of the humor of Mark Twain have been descriptions of the persons who did not appreciate his humor at all. We have become familiar with the Californians who were thrilled with terror by his burlesque of a newspaper reporter’s way of telling a story, and we have heard of the Pennsylvania clergyman who sadly returned his Innocents Abroad to the book-agent with the remark that ‘the man who could shed tears over the tomb of Adam must be an idiot.’ But Mark Twain may now add a much more glorious instance to his string of trophies. The Saturday Review, in its number of October 8th, reviews his book of travels, which has been republished in England, and reviews it seriously. We can imagine the delight of the humorist in reading this tribute to his power; and indeed it is so amusing in itself that he can hardly do better than reproduce the article in full in his next monthly Memoranda.”

(Publishing the above paragraph thus, gives me a sort of authority for reproducing the Saturday Review’s article in full in these pages. I dearly wanted to do it, for I cannot write anything half so delicious myself. If I had a cast-iron dog that could read this English criticism and preserve his austerity, I would drive him off the door-step.)

(From the London “Saturday Review.”)

“Reviews of New Books”

“The Innocents Abroad. A Book of Travels. By Mark Twain. London: Hotten, publisher. 1870. “Lord Macaulay died too soon. We never felt this so deeply as when we finished the last chapter of the above- named extravagant work. Macaulay died too soon—for none but he could mete out complete and comprehensive justice to the insolence, the impertinence, the presumption, the mendacity, and, above all, the majestic ignorance of this author.

“To say that the Innocents Abroad is a curious book, would be to use the faintest language—would be to speak of the Matterhorn as a neat elevation or of Niagara as being ‘nice’ or ‘pretty.’ ‘Curious’ is too tame a word wherewith to describe the imposing insanity of this work. There is no word that is large enough or long enough. Let us, therefore, photograph a passing glimpse of book and author, and trust the rest to the reader. Let the cultivated English student of human nature picture to himself this Mark Twain as a person capable of doing the following-described things—and not only doing them, but with incredible innocence printing them calmly and tranquilly in a book. For instance:

“He states that he entered a hair-dresser’s in Paris to get shaved, and the first ‘rake’ the barber gave with his razor it loosened his ‘hide’ and lifted him out of the chair.

“This is unquestionably exaggerated. In Florence he was so annoyed by beggars that he pretends to have seized and eaten one in a frantic spirit of revenge. There is, of course, no truth in this. He gives at full length a theatrical programme seventeen or eighteen hundred years old, which he professes to have found in the ruins of the Coliseum, among the dirt and mould and rubbish. It is a sufficient comment upon this statement to remark that even a cast-iron programme would not have lasted so long under such circumstances. In Greece he plainly betrays both fright and flight upon one occasion, but with frozen efforntery puts the latter in this falsely tame form: ‘We sidled towards the Piræus.’ ‘Sidled,’ indeed! He does not hesitate to intimate that at Ephesus, when his mule strayed from the proper course, he got down, took him under his arm, carried him to the road again, pointed him right, remounted, and went to sleep contentedly till it was time to restore the beast to the path once more. He states that a growing youth among his ship’s passengers was in the constant habit of appeasing his hunger with soap and oakum between meals. In Palestine he tells of ants that came eleven miles to spend the summer in the desert and brought their provisions with them; yet he shows by his description of the country that the feat was an impossibility. He mentions, as if it were the most commonplace of matters, that he cut a Moslem in two in broad daylight in Jerusalem, with Godfrey de Bouillon’s sword, and would have shed more blood if he had had a graveyard of his own. These statements are unworthy a moment’s attention. Mr. Twain or any other foreigner who did such a thing in Jerusalem would be mobbed, and would infallibly lose his life. But why go on? Why repeat more of his audacious and exasperating falsehoods? Let us close fittingly with this one: he affirms that ‘in the mosque of St. Sophia at Constantinople I got my feet so stuck up with a complication of gums, slime, and general impurity, that I wore out more than two thousand pair of bootjacks getting my boots off that night, and even then some Christian hide peeled off with them.’ It is monstrous. Such statements are simply lies—there is no other name for them. Will the reader longer marvel at the brutal ignorance that pervades the American nation when we tell him that we are informed upon perfectly good authority that this extravagant compilation of falsehoods, this exhaustless mine of stupendous lies, this Innocents Abroad, has actually been adopted by the schools and colleges of several of the States as a text-book!

“But if his falsehoods are distressing, his innocence and his ignorance are enough to make one burn the book and despise the author. In one place he was so appalled at the sudden spectacle of a murdered man, unveiled by the moonlight, that he jumped out of the window, going through sash and all, and then remarks with the most childlike simplicity that he ‘was not scared, but was considerably agitated.’ It puts us out of patience to note that the simpleton is densely unconscious that Lucrezia Borgia ever existed off the stage. He is vulgarly ignorant of all foreign languages, but is frank enough to criticise the Italians’ use of their own tongue. He says they spell the name of their great painter ‘Vinci, but pronounce it Vinchy’—and then adds with a naïveté possible only to helpless ignorance, ‘foreigners always spell better than they pronounce.’ In another place he commits the bald absurdity of putting the phrase ‘tare an ouns’ into an Italian’s mouth. In Rome he unhesitatingly believes the legend that St. Philip Neri’s heart was so inflamed with divine love that it burst his ribs—believes it wholly because an author with a learned list of university degrees strung after his name endorses it—‘otherwise,’ says this gentle idiot, ‘I should have felt a curiosity to know what Philip had for dinner.’ Our author makes a long, fatiguing journey to the Grotto del Cane on purpose to test its poisoning powers on a dog—got elaborately ready for the experiment, and then discovered that he had no dog. A wiser person would have kept such a thing discreetly to himself, but with this harmless creature everything comes out. He hurts his foot in a rut two thousand years old in exhumed Pompeii, and presently, when staring at one of the cinder-like corpses unearthed in the next square, conceives the idea that may be it is the remains of the ancient Street Commissioner, and straightway his horror softens down to a sort of chirpy contentment with the condition of things. In Damascus he visits the well of Ananias, three thousand years old, and is as surprised and delighted as a child to find that the water is ‘as pure and fresh as if the well had been dug yesterday.’ In the Holy Land he gags desperately at the hard Arabic and Hebrew Biblical names, and finally concludes to call them Baldwinsville, Williamsburgh, and so on, ‘for convenience of spelling.’

“We have thus spoken freely of this man’s stupefying simplicity and innocence, but we cannot deal similarly with his colossal ignorance. We do not know where to begin. And if we knew where to begin, we certainly would not know where to leave off. We will give one specimen, and one only. He did not know, until he got to Rome, that Michael Angelo was dead! And then, instead of crawling away and hiding his shameful ignorance somewhere, he proceeds to express a pious, grateful sort of satisfaction that he is gone and out of his troubles!

“No, the reader may seek out the author’s exhibition of his uncultivation for himself. The book is absolutely dangerous, considering the magnitude and variety of its misstatements, and the convincing confidence with which they are made. And yet it is a text-book in the schools of America.

The poor blunderer mouses among the sublime creations of the Old Masters, trying to acquire the elegant proficiency in art-knowledge, which he has a groping sort of comprehension is a proper thing for the travelled man to be able to display. But what is the manner of his study? And what is the progress he achieves? To what extent does he familiarize himself with the great pictures of Italy, and what degree of appreciation does he arrive at? Read:

“‘When we see a monk going about with a lion and looking up into heaven, we know that that is St. Mark. When we see a monk with a book and a pen, looking tranquilly up to heaven, trying to think of a word, we know that that is St. Matthew. When we see a monk sitting on a rock, looking tranquilly up to heaven, with a human skull beside him, and without other baggage, we know that that is St. Jerome. Because we know that he always went flying light in the matter of baggage. When we see other monks looking tranquilly up to heaven, but having no trade-mark, we always ask who those parties are. We do this because we humbly wish to learn.’

“He then enumerates the thousands and thousands of copies of these several pictures which he has seen, and adds with accustomed simplicity that he feels encouraged to believe that when he has seen ‘Some More’ of each, and had a larger experience, he will eventually ‘begin to take an absorbing interest in them’—the vulgar boor.

“That we have shown this to be a remarkable book, we think no one will deny. That it is a pernicious book to place in the hands of the confiding and uninformed, we think we have also shown. That the book is a deliberate and wicked creation of a diseased mind, is apparent upon every page. Having placed our judgement thus upon record, let us close with what charity we can, by remarking that even in this volume there is some good to be found; for whenever the author talks of his own country and lets Europe alone, he never fails to make himself interesting, and not only interesting, but instructive. No one can read without benefit his occasional chapters and paragraphs, about life in the gold and silver mines of California and Nevada; about the Indians of the plains and deserts of the West, and their cannibalism; about the raising of vegetables in kegs of gunpowder by the aid of two or three teaspoonfuls of guano; about the moving of small farms from place to place at night in wheelbarrows to avoid taxes; and about a sort of cows and mules in the Humboldt mines, that climb down chimneys and disturb the people at night. These matters are not only new, but are well worth knowing. It is a pity the author did not put in more of the same kind. His book is well written and is exceedingly entertaining, and so it just barely escaped being quite valuable also.”

(One month later)

Latterly I have received several letters, and see a number of newspaper paragraphs, all upon a certain subject, and all of about the same tenor. I here give honest specimens. One is from a New York paper, one is from a letter from an old friend, and one is from a letter from a New York publisher who is a stranger to me. I humbly endeavor to make these bits tooth-some with the remark that the article they are praising (which appeared in the December Galaxy, and pretended to be a criticism from the London Saturday Review on my Innocents Abroad) was written by myself, every line of it:

“The Herald says the richest thing out is the ‘serious critique’ in the London Saturday Review, on Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad. We thought before we read it that it must be ‘serious,’ as everybody said so, and were even ready to shed a few tears; but since perusing it, we are bound to confess that next to Mark Twain’s ‘Jumping Frog’ it’s the finest bit of humor and sarcasm that we’ve come across in many a day.”

(I do not get a compliment like that every day.)

“I used to think that your writings were pretty good, but after reading the criticism in The Galaxy from the London Review, have discovered what an ass I must have been. If suggestions are in order, mine is, that you put that article in your next edition of the Innocents, as an extra chapter, if you are not afraid to put your own humor in competition with it. It is as rich a thing as I ever read.”

(Which is strong commendation from a book publisher.)

“The London Reviewer, my friend, is not the stupid, ‘serious’ creature he pretends to be, I think; but, on the contrary, has a keen appreciation and enjoyment of your book. As I read his article in The Galaxy, I could imagine him giving vent to many a hearty laugh. But he is writing for Catholics and Established Church people, and high-toned, antiquated, conservative gentility, whom it is a delight to him to help you shock, while he pretends to shake his head with owlish density. He is a magnificent humorist himself.” (Now that is graceful and handsome. I take off my hat to my life-long friend and comrade, and with my feet together and my fingers spread over my heart, I say, in the language of Alabama, “You do me proud.”)

I stand guilty of the authorship of the article, but I did not mean any harm. I saw by an item in the Boston Advertiser that a solemn, serious critique on the English edition of my book had appeared in the London Saturday Review, and the idea of such a literary breakfast by a stolid, ponderous British ogre of the quill was too much for a naturally weak virtue, and I went home and burlesqued it—revelled in it, I may say. I never saw a copy of the real Saturday Review criticism until after my burlesque was written and mailed to the printer. But when I did get hold of a copy, I found it to be vulgar, awkwardly written, ill- natured, and entirely serious and in earnest. The gentleman who wrote the newspaper paragraph above quoted had not been misled as to its character.

If any man doubts my word now, I will kill him. No, I will not kill him; I will win his money. I will bet him twenty to one, and let any New York publisher hold the stakes, that the statements I have above made as to the authorship of the article in question are entirely true. Perhaps I may get wealthy at this, for I am willing to take all the bets that offer; and if a man wants larger odds, I will give him all he requires. But he ought to find out whether I am betting on what is termed “a sure thing” or not before he ventures his money, and he can do that by going to a public library and examining the London Saturday Review of October 8th, which contains the real critique.

Bless me, some people thought that I was the “sold” person!

P. S.—I cannot resist the temptation to toss in this most savory thing of all—this easy, graceful, philosophical disquisition, with its happy, chirping confidence. It is from the Cincinnati Enquirer:

“Nothing is more uncertain than the value of a fine cigar. Nine smokers out of ten would prefer an ordinary domestic article, three for a quarter, to a fifty-cent Partaga, if kept in ignorance of the cost of the latter. The flavor of the Partaga is too delicate for palates that have been accustomed to Connecticut seed leaf. So it is with humor. The finer it is in quality, the more danger of its not being recognized at all. Even Mark Twain has been taken in by an English review of his Innocents Abroad. Mark Twain is by no means a coarse humorist, but the Englishman’s humor is so much finer than his, that he mistakes it for solid earnest, and ‘larfs most consumedly.’ ”

A man who cannot learn stands in his own light. Hereafter, when I write an article which I know to be good, but which I may have reason to fear will not, in some quarters, be considered to amount to much, coming from an American, I will aver that an Englishman wrote it and that it is copied from a London journal. And then I will occupy a back seat and enjoy the cordial applause.

(Still later)

“Mark Twain at last sees that the Saturday Review’s criticism of his Innocents Abroad was not serious, and he is intensely mortified at the thought of having been so badly sold. He takes the only course left him, and in the last Galaxy claims that he wrote the criticism himself, and published it in The Galaxy to sell the public. This is ingenious, but unfortunately it is not true. If any of our readers will take the trouble to call at this office we will show them the original article in the Saturday Review of October 8th, which, on comparison, will be found to be identical with the one published in The Galaxy. The best thing for Mark to do will be to admit that he was sold, and say no more about it.”

The above is from the Cincinnati Enquirer, and is a falsehood. Come to the proof. If the Enquirer people, through any agent, will produce at The Galaxy office a London Saturday Review of October 8th, containing an “article which, on comparison, will be found to be that identical with the one published in The Galaxy, I will pay to that agent five hundred dollars cash. Moreover, if at any specified time I fail to produce at the same place a copy of the London Saturday Review of October 8th, containing a lengthy criticism upon the Innocents Abroad, entirely different, in every paragraph and sentence, from the one I published in The Galaxy, I will pay to the Enquirer agent another five hundred dollars cash. I offer Sheldon & Co., publishers, 500 Broadway, New York, as my “backers.” Any one in New York, authorized by the Enquirer, will receive prompt attention. It is an easy and profitable way for the Enquirer people to prove that they have not uttered a pitiful, deliberate falsehood in the above paragraphs. Will they swallow that falsehood ignominiously, or will they send an agent to The Galaxy office? I think the Cincinnati Enquirer must be edited by children.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

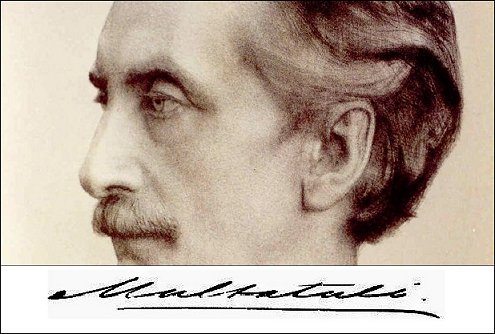

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 1096

Ik zal wel genoodzaakt wezen soms terugtekomen op eenige byzonderheden in de werking van zekere boeken op Wouter’s gemoed. Evenals dokter Holsma vroeg wat de familie gewoon was te eten, toen-i geraadpleegd werd over de menigvuldige kwalen van Petrò, heeft de lezer eenig recht op de kennis van wat er al zoo aan Wouter werd ingegeven in die leesbibliotheek op den Zeedyk. En ik zou ‘n slordige geschiedschryver zyn als ik daarvan geen melding maakte.

Daar waren drie, vier, planken, die met ‘r allen één schryver torschten…

O!

Voor-als-nog voel ik me onbekwaam den indruk te schetsen van die… vier planken! Ik zou daartoe meer kans zien wanneer ik alleen bejaarde menschen onder m’n gehoor had, personen by wie ‘tmeminisse me kon te-hulp komen…

Ach!

Maar om nu, nu, in 1873…

na ‘t wonderjaar ’48…

na en gedurende de toepassing van stoom en elektriciteit…

na ‘t uitvinden van debating-clubs en kieskollegien…

na de verheffing der Industrie tot ‘n generale agentuur ter bevordering der sofistikatie van levensmiddelen…

na ‘t oprichten van hoogere-burgerscholen en de schrikbarende vermenigvuldiging van knappe kinderen…

na ‘t meedoogenloos uitroeien van het naïve…

na, na… na alles dus wat het tegenwoordig geslacht zoo oneindig hoog verheft boven ‘t voorlaatste…

Ik wil maar zeggen dat ik niet den moed heb, den naam te noemen van ‘n schryver die zestig jaar geleden zooveel planken buigen, en zooveel harten kloppen deed, tot brekens en berstens toe.

Toch hoop ik ‘t eenmaal te doen, en wel zoodra ik mezelf betrap op ‘n vleugje van excentriciteit.

Maar vooraf heb ik behoefte aan ‘t opfrisschen van m’n herinnering. Al beleefde ik den bloeityd der hier bedoelde soort van litteratuur niet, toch ligt de kennismaking te lang achter my, om zonder opzettelyke studie den toenmaligen smaak te kunnen toetsen aan m’n tegenwoordig oordeel. Ik moet eerst ‘n gedeelte van die werken – godbewaarme voor de heele vier planken! – met aandacht weder lezen. De my opgelegde taak heeft iets van ‘n geestbezwering, en de veelschryvende vriend van m’n jeugd zal wel genoodzaakt wezen ter-zyner tyd de rol te spelen van revenant.

Dit weet ik, en ‘t verwonderde my dus in ‘t minst niet by onderscheiden gelegenheden te bemerken dat z’n naam uit het geheugen gewischt is van de kleinkinderen zyner vereerders niet alleen, maar zelfs van bekwame boekhandelaars en bibliofilen! Ach – en: O! – sic transit!

Die naam was toch eenmaal ‘t pas- wacht- en heiligwoord, waaraan legioenen eenzame kluizenaars in afgelegen dalen en ongenaakbare wildernissen, elkaar herkenden! Er bestond ‘n tyd, dat het portret van dien man in armband of halssieraad, het uitsluitend bevoorrecht embleem was, hetshibboleth van modieuze gevoeligheid en sentimenteelen goeden toon. Verloofden zwoeren dure eeden dat ‘s mans helden en heldinnen – nu ja, één of twee uit den groep – peet wezen zouden van de eerste – en volgende – vruchten hunner ‘bekroonde’ liefde, en menig trouwverbond werd gesloten onder aanroeping van de… aandoeningen – ‘beginselen’ mag ik niet zeggen – die hy had opgewekt in de harten!

Om me voortebereiden tot de nauwkeurigheid die ik hoop in-acht te nemen by de behandeling van dien schryver, moet ik reeds nu de opmerking maken dat dit: ‘opwekken van aandoeningen’ slechts in zeer betrekkelyken zin juist gezegd is. Op de individuen die zich overgaven aan de betoovering van z’n stem, moge deze uitdrukking nagenoeg toepasselyk zyn, over ‘t geheel echter was de door my bedoelde voorganger van één dag, slechts de uitdrukking van z’n tyd, een der trompetten waarop de logika der feiten ‘t mondstuk zet.

Voorloopig echter wil ik dit voorbyzien. Hy oefende grooten invloed uit, en is in zekeren zin een der hoofdbewerkers van ‘t hedendaagsch materialismus, geenszins in theologischen zin – j’en suis! – maar in zedelyke en artistieke beteekenis. Ik bedoel het materialismus der geldmakery, en van de jacht op plomp genot.

De lezer zal aan ‘n drukfout denken, of – met ‘n krant die me dezer dagen onder de oogen kwam – meenen dat ‘de oorlog met Atjin me in ‘t hoofd geslagen is’ wanneer-i, na deze bewering, te weten komt dat de O! ‘s en Ach! ‘s waarmee ik zoo-even ‘n paar zinsneden verfraaide, aan dien schryver ontleend zyn. O- en Ach-auteurs en… materialismus?

Ja. O! Ach! en materialismus!

Om nu den lezer nog verder van den weg te helpen…

Reklame! Onder al de dertienhonderd millioen aardbewoners is niemand dan ik in-staat hem er weer behoorlyk op te brengen. En alzoo:

… om ‘t verband tusschen die eenzame kluizenaars, halssieraden, peetschappen en trouwbeloften met materialismus, nog ontastbaarder te maken…

O!

…en den lezer te dwingen op myn bon plaisir te wachten voor-i den sleutel vindt, waarmee deze mysterie kan ontraadseld worden…

Ach!

…daarom hier ‘n citaat uit onzen schryver. Men bedenke dat ik z’n boeken niet by-de-hand heb, en uit het geheugen aanhaal.

‘En zuchtte zy: Ergoteles,

Dan lispte hy: Theone!’

Zie-zoo, m’n ‘knoop’ is gereed! De lezer is nu wel genoodzaakt m’n schryfheld onder verzenmakers te zoeken: éérste dwaling. Hy moet hem voor ‘n graecus houden: Ergoteles…?????! Theone…????! Dit is duidelyk, niet waar? Zeer duidelyk, en de tweede dwaling. Hy was ‘n schoolmeester, en plaatste ‘t woord: Ergoteles in de maat, om z’n leerlingen te waarschuwen tegen ‘n lapsisch: èrregotélis. Ook dit lydt geen tegenspraak, en vormt alzoo de derde dwaling die ik in ‘t leven roepen wilde.

Quaeritur nu: welke graecizeerende verzenmakende schoolmeester heeft met behulp van: O! en:Ach! meegewerkt aan ‘t veroorzaken van het thans heerschend materialismus op ‘t gebied van Smaak, Kunst en Zeden?

O? Ja! Ach? Ja! En men durft spreken van Göthe’s Werther! Van ‘t onnoozel liefdeheldje dat de schuld dragen zou van zooveel zelfmoorden? Gekheid! Noch Göthe, noch een van z’n scheppingen waren ooit zoo populair als de man van m’n raadseltje en die vyf planken – misschien waren ‘t er zeven of acht! – en wat al die zelfmoorden aangaat, lezer, ik geloof er niet aan. Mocht ik hierin ongelyk hebben, dan nog beweer ik dat één held van myn gevoelsman, des-verkiezende zou in-staat geweest zyn meer kerkhoven te bevolken dan tien Werthers… met de misteekende Mignon er by. Maar dit deden die helden niet, waarlyk niet! Zonder deze pryzenswaardige onthouding toeteschryven aan diskretie alleen… geloof me, lezer, dat sterven aan ongelukkige liefden is ‘n boosaardig uitstrooisel van ‘bekroonde’ echtparen die zich vervelen, en die niet verdragen kunnen dat anderen ‘t romantisch geluk hebben zoo belangwekkend ongelukkig te zyn.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 1

Misschien is niets geheel waar,

en zelfs dát niet.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

IX. Le hareng saur

Ta robe, ô hareng, c’est la palette des soleils couchants, la patine du vieux cuivre, le ton d’or bruni des cuirs de Cordoue, les teintes de santal et de safran des feuillages d’automne!

Ta tête, ô hareng, flamboie comme un casque d’or, et l’on dirait de tes yeux des clous noirs plantés dans des cercles de cuivre!

Toutes les nuances tristes et mornes, toutes les nuances rayonnantes et gaies amortissent et illuminent tour à tour ta robe d’écailles.

A côté des bitumes, des terres de Judée et de Cassel, des ombres brûlées et des verts de Scheele, des bruns Van Dyck et des bronzes florentins, des teintes de rouille et de feuille morte, resplendissent, de tout leur éclat, les ors verdis, les ambres jaunes, les orpins, les ocres de rhu, les chromes, les oranges de mars!

O miroitant et terne enfumé, quand je contemple ta cotte de mailles, je pense aux tableaux de Rembrandt, je revois ses têtes superbes, ses chairs ensoleillées, ses scintillements de bijoux sur le velours noir; je revois ses jets de lumière dans la nuit, ses traînées de poudre d’or dans l’ombre, ses éclosions de soleils sous les noirs arceaux!

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

.jpg)

Elf Söhne

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Ich habe elf Söhne.

Der Erste ist äußerlich sehr unansehnlich, aber ernsthaft und klug; trotzdem schätze ich ihn, wiewohl ich ihn als Kind wie alle andern liebe, nicht sehr hoch ein. Sein Denken scheint mir zu einfach. Er sieht nicht rechts noch links und nicht in die Weite; in seinem kleinen Gedankenkreis läuft er immerfort rundum oder dreht sich vielmehr.

Der Zweite ist schön, schlank, wohlgebaut; es entzückt, ihn in Fechterstellung zu sehen. Auch er ist klug, aber überdies welterfahren; er hat viel gesehen, und deshalb scheint selbst die heimische Natur vertrauter mit ihm zu sprechen, als mit den Daheimgebliebenen. Doch ist gewiß dieser Vorzug nicht nur und nicht einmal wesentlich dem Reisen zu verdanken, er gehört vielmehr zu dem Unnachahmlichen dieses Kindes, das zum Beispiel von jedem anerkannt wird, der etwa seinen vielfach sich überschlagenden und doch geradezu wild beherrschten Kunstsprung ins Wasser ihm nachmachen will. Bis zum Ende des Sprungbrettes reicht der Mut und die Lust, dort aber statt zu springen, setzt sich plötzlich der Nachahmer und hebt entschuldigend die Arme. – Und trotz dem allen (ich sollte doch eigentlich glückselig sein über ein solches Kind) ist mein Verhältnis zu ihm nicht ungetrübt. Sein linkes Auge ist ein wenig kleiner als das rechte und zwinkert viel; ein kleiner Fehler nur, gewiß, der sein Gesicht sogar noch verwegener macht als es sonst gewesen wäre, und niemand wird gegenüber der unnahbaren Abgeschlossenheit seines Wesens dieses kleinere zwinkernde Auge tadelnd bemerken. Ich, der Vater, tue es. Es ist natürlich nicht dieser körperliche Fehler, der mir weh tut, sondern eine ihm irgendwie entsprechende kleine Unregelmäßigkeit seines Geistes, irgendein in seinem Blut irrendes Gift, irgendeine Unfähigkeit, die mir allein sichtbare Anlage seines Lebens rund zu vollenden. Gerade dies macht ihn allerdings andererseits wieder zu meinem wahren Sohn, denn dieser sein Fehler ist gleichzeitig der Fehler unserer ganzen Familie und an diesem Sohn nur überdeutlich.

Der dritte Sohn ist gleichfalls schön, aber es ist nicht die Schönheit, die mir gefällt. Es ist die Schönheit des Sängers: der geschwungene Mund; das träumerische Auge; der Kopf, der eine Draperie hinter sich benötigt, um zu wirken; die unmäßig sich wölbende Brust; die leicht auffahrenden und viel zu leicht sinkenden Hände; die Beine, die sich zieren, weil sie nicht tragen können. Und überdies: der Ton seiner Stimme ist nicht voll; trügt einen Augenblick; läßt den Kenner aufhorchen; veratmet aber kurz darauf. – Trotzdem im allgemeinen alles verlockt, diesen Sohn zur Schau zu stellen, halte ich ihn doch am liebsten im Verborgenen; er selbst drängt sich nicht auf, aber nicht etwa deshalb, weil er seine Mängel kennt, sondern aus Unschuld. Auch fühlt er sich fremd in unserer Zeit; als gehöre er zwar zu meiner Familie, aber überdies noch zu einer andern, ihm für immer verlorenen, ist er oft unlustig und nichts kann ihn aufheitern.

Mein vierter Sohn ist vielleicht der umgänglichste von allen. Ein wahres Kind seiner Zeit, ist er jedermann verständlich, er steht auf dem allen gemeinsamen Boden und jeder ist versucht, ihm zuzunicken. Vielleicht durch diese allgemeine Anerkennung gewinnt sein Wesen etwas Leichtes, seine Bewegungen etwas Freies, seine Urteile etwas Unbekümmertes. Manche seiner Aussprüche möchte man oft wiederholen, allerdings nur manche, denn in seiner Gesamtheit krankt er doch wieder an allzu großer Leichtigkeit. Er ist wie einer, der bewundernswert abspringt, schwalbengleich die Luft teilt, dann aber doch trostlos im öden Staube endet, ein Nichts. Solche Gedanken vergällen mir den Anblick dieses Kindes.

Der fünfte Sohn ist lieb und gut; versprach viel weniger als er hielt; war so unbedeutend, daß man sich förmlich in seiner Gegenwart allein fühlte; hat es aber doch zu einigem Ansehen gebracht. Fragte man mich, wie das geschehen ist, so könnte ich kaum antworten. Unschuld dringt vielleicht doch noch am leichtesten durch das Toben der Elemente in dieser Welt, und unschuldig ist er. Vielleicht allzu unschuldig.

Freundlich zu jedermann. Vielleicht allzu freundlich. Ich gestehe: mir wird nicht wohl, wenn man ihn mir gegenüber lobt. Es heißt doch, sich das Loben etwas zu leicht zu machen, wenn man einen so offensichtlich Lobenswürdigen lobt, wie es mein Sohn ist.

Mein sechster Sohn scheint, wenigstens auf den ersten Blick, der tiefsinnigste von allen. Ein Kopfhänger und doch ein Schwätzer. Deshalb kommt man ihm nicht leicht bei. Ist er am Unterliegen, so verfällt er in unbesiegbare Traurigkeit; erlangt er das Übergewicht, so wahrt er es durch Schwätzen. Doch spreche ich ihm eine gewisse selbstvergessene Leidenschaft nicht ab; bei hellem Tag kämpft er sich oft durch das Denken wie im Traum. Ohne krank zu sein – vielmehr hat er eine sehr gute Gesundheit – taumelt er manchmal, besonders in der Dämmerung, braucht aber keine Hilfe, fällt nicht. Vielleicht hat an dieser Erscheinung seine körperliche Entwicklung schuld, er ist viel zu groß für sein Alter. Das macht ihn unschön im Ganzen, trotz auffallend schöner Einzelheiten, zum Beispiel der Hände und Füße. Unschön ist übrigens auch seine Stirn; sowohl in der Haut, als in der Knochenbildung irgendwie verschrumpft.

Der siebente Sohn gehört mir vielleicht mehr als alle andern. Die Welt versteht ihn nicht zu würdigen; seine besondere Art von Witz versteht sie nicht. Ich überschätze ihn nicht; ich weiß, er ist geringfügig genug; hätte die Welt keinen andern Fehler als den, daß sie ihn nicht zu würdigen weiß, sie wäre noch immer makellos. Aber innerhalb der Familie wollte ich diesen Sohn nicht missen. Sowohl Unruhe bringt er, als auch Ehrfurcht vor der Überlieferung, und beides fügt er, wenigstens für mein Gefühl, zu einem unanfechtbaren Ganzen. Mit diesem Ganzen weiß er allerdings selbst am wenigsten etwas anzufangen; das Rad der Zukunft wird er nicht ins Rollen bringen; aber diese seine Anlage ist so aufmunternd, so hoffnungsreich; ich wollte, er hätte Kinder und diese wieder Kinder. Leider scheint sich dieser Wunsch nicht erfüllen zu wollen. In einer mir zwar begreiflichen, aber ebenso unerwünschten Selbstzufriedenheit, die allerdings in großartigem Gegensatz zum Urteil seiner Umgebung steht, treibt er sich allein umher, kümmert sich nicht um Mädchen und wird trotzdem niemals seine gute Laune verlieren.

Mein achter Sohn ist mein Schmerzenskind, und ich weiß eigentlich keinen Grund dafür. Er sieht mich fremd an, und ich fühle mich doch väterlich eng mit ihm verbunden. Die Zeit hat vieles gut gemacht; früher aber befiel mich manchmal ein Zittern, wenn ich nur an ihn dachte. Er geht seinen eigenen Weg; hat alle Verbindungen mit mir abgebrochen; und wird gewiß mit seinem harten Schädel, seinem kleinen athletischen Körper – nur die Beine hatte er als Junge recht schwach, aber das mag sich inzwischen schon ausgeglichen haben – überall durchkommen, wo es ihm beliebt. Öfters hatte ich Lust, ihn zurückzurufen, ihn zu fragen, wie es eigentlich um ihn steht, warum er sich vom Vater so abschließt und was er im Grunde beabsichtigt, aber nun ist er so weit und so viel Zeit ist schon vergangen, nun mag es so bleiben wie es ist. Ich höre, daß er als der einzige meiner Söhne einen Vollbart trägt; schön ist das bei einem so kleinen Mann natürlich nicht.

Mein neunter Sohn ist sehr elegant und hat den für Frauen bestimmten süßen Blick. So süß, daß er bei Gelegenheit sogar mich verführen kann, der ich doch weiß, daß förmlich ein nasser Schwamm genügt, um allen diesen überirdischen Glanz wegzuwischen. Das Besondere an diesem Jungen aber ist, daß er gar nicht auf Verführung ausgeht; ihm würde es genügen, sein Leben lang auf dem Kanapee zu liegen und seinen Blick an die Zimmerdecke zu verschwenden oder noch viel lieber ihn unter den Augenlidern ruhen zu lassen. Ist er in dieser von ihm bevorzugten Lage, dann spricht er gern und nicht übel; gedrängt und anschaulich; aber doch nur in engen Grenzen; geht er über sie hinaus, was sich bei ihrer Enge nicht vermeiden läßt, wird sein Reden ganz leer. Man würde ihm abwinken, wenn man Hoffnung hätte, daß dieser mit Schlaf gefüllte Blick es bemerken könnte.

Mein zehnter Sohn gilt als unaufrichtiger Charakter. Ich will diesen Fehler nicht ganz in Abrede stellen, nicht ganz bestätigen. Sicher ist, daß, wer ihn in der weit über sein Alter hinausgehenden Feierlichkeit herankommen sieht, im immer festgeschlossenen Gehrock, im alten, aber übersorgfältig geputzten schwarzen Hut, mit dem unbewegten Gesicht, dem etwas vorragenden Kinn, den schwer über die Augen sich wölbenden Lidern, den manchmal an den Mund geführten zwei Fingern – wer ihn so sieht, denkt: das ist ein grenzenloser Heuchler. Aber, nun höre man ihn reden! Verständig; mit Bedacht; kurz angebunden; mit boshafter Lebendigkeit Fragen durchkreuzend; in erstaunlicher, selbstverständlicher und froher Übereinstimmung mit dem Weltganzen; eine Übereinstimmung, die notwendigerweise den Hals strafft und den Kopf erheben läßt. Viele, die sich sehr klug dünken und die sich, aus diesem Grunde wie sie meinten, von seinem Äußern abgestoßen fühlten, hat er durch sein Wort stark angezogen. Nun gibt es aber wieder Leute, die sein Äußeres gleichgültig läßt, denen aber sein Wort heuchlerisch erscheint. Ich, als Vater, will hier nicht entscheiden, doch muß ich eingestehen, daß die letzteren Beurteiler jedenfalls beachtenswerter sind als die ersteren.

Mein elfter Sohn ist zart, wohl der schwächste unter meinen Söhnen; aber täuschend in seiner Schwäche; er kann nämlich zu Zeiten kräftig und bestimmt sein, doch ist allerdings selbst dann die Schwäche irgendwie grundlegend. Es ist aber keine beschämende Schwäche, sondern etwas, das nur auf diesem unsern Erdboden als Schwäche erscheint. Ist nicht zum Beispiel auch Flugbereitschaft Schwäche, da sie doch Schwanken und Unbestimmtheit und Flattern ist? Etwas Derartiges zeigt mein Sohn. Den Vater freuen natürlich solche Eigenschaften nicht; sie gehen ja offenbar

auf Zerstörung der Familie aus. Manchmal blickt er mich an, als wollte er mir sagen: »Ich werde dich mitnehmen, Vater.« Dann denke ich: »Du wärst der Letzte, dem ich mich vertraue.« Und sein Blick scheint wieder zu sagen: »Mag ich also wenigstens der Letzte sein.«

Das sind die elf Söhne.

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Jane Austen

It is probable that if Miss Cassandra Austen had had her way we should have had nothing of Jane Austen’s except her novels. To her elder sister alone did she write freely; to her alone she confided her hopes and, if rumour is true, the one great disappointment of her life; but when Miss Cassandra Austen grew old, and the growth of her sister’s fame made her suspect that a time might come when strangers would pry and scholars speculate, she burnt, at great cost to herself, every letter that could gratify their curiosity, and spared only what she judged too trivial to be of interest.

Hence our knowledge of Jane Austen is derived from a little gossip, a few letters, and her books. As for the gossip, gossip which has survived its day is never despicable; with a little rearrangement it suits our purpose admirably. For example, Jane “is not at all pretty and very prim, unlike a girl of twelve . . . Jane is whimsical and affected,” says little Philadelphia Austen of her cousin. Then we have Mrs. Mitford, who knew the Austens as girls and thought Jane “the prettiest, silliest, most affected husband-hunting butterfly she ever remembers “. Next, there is Miss Mitford’s anonymous friend “who visits her now [and] says that she has stiffened into the most perpendicular, precise, taciturn piece of ‘single blessedness’ that ever existed, and that, until Pride and Prejudice showed what a precious gem was hidden in that unbending case, she was no more regarded in society than a poker or firescreen. . . . The case is very different now”, the good lady goes on; “she is still a poker — but a poker of whom everybody is afraid. . . . A wit, a delineator of character, who does not talk is terrific indeed!” On the other side, of course, there are the Austens, a race little given to panegyric of themselves, but nevertheless, they say, her brothers “were very fond and very proud of her. They were attached to her by her talents, her virtues, and her engaging manners, and each loved afterwards to fancy a resemblance in some niece or daughter of his own to the dear sister Jane, whose perfect equal they yet never expected to see.” Charming but perpendicular, loved at home but feared by strangers, biting of tongue but tender of heart — these contrasts are by no means incompatible, and when we turn to the novels we shall find ourselves stumbling there too over the same complexities in the writer.

To begin with, that prim little girl whom Philadelphia found so unlike a child of twelve, whimsical and affected, was soon to be the authoress of an astonishing and unchildish story, Love and Freindship,8 which, incredible though it appears, was written at the age of fifteen. It was written, apparently, to amuse the schoolroom; one of the stories in the same book is dedicated with mock solemnity to her brother; another is neatly illustrated with water-colour heads by her sister. These are jokes which, one feels, were family property; thrusts of satire, which went home because all little Austens made mock in common of fine ladies who “sighed and fainted on the sofa”.

Brothers and sisters must have laughed when Jane read out loud her last hit at the vices which they all abhorred. “I die a martyr to my grief for the loss of Augustus. One fatal swoon has cost me my life. Beware of Swoons, Dear Laura. . . . Run mad as often as you chuse, but do not faint. . . .” And on she rushed, as fast as she could write and quicker than she could spell, to tell the incredible adventures of Laura and Sophia, of Philander and Gustavus, of the gentleman who drove a coach between Edinburgh and Stirling every other day, of the theft of the fortune that was kept in the table drawer, of the starving mothers and the sons who acted Macbeth. Undoubtedly, the story must have roused the schoolroom to uproarious laughter. And yet, nothing is more obvious than that this girl of fifteen, sitting in her private corner of the common parlour, was writing not to draw a laugh from brother and sisters, and not for home consumption. She was writing for everybody, for nobody, for our age, for her own; in other words, even at that early age Jane Austen was writing. One hears it in the rhythm and shapeliness and severity of the sentences. “She was nothing more than a mere good-tempered, civil, and obliging young woman; as such we could scarcely dislike her — she was only an object of contempt.” Such a sentence is meant to outlast the Christmas holidays. Spirited, easy, full of fun, verging with freedom upon sheer nonsense,— Love and Freindship is all that; but what is this note which never merges in the rest, which sounds distinctly and penetratingly all through the volume? It is the sound of laughter. The girl of fifteen is laughing, in her corner, at the world.

Girls of fifteen are always laughing. They laugh when Mr. Binney helps himself to salt instead of sugar. They almost die of laughing when old Mrs. Tomkins sits down upon the cat. But they are crying the moment after. They have no fixed abode from which they see that there is something eternally laughable in human nature, some quality in men and women that for ever excites our satire. They do not know that Lady Greville who snubs, and poor Maria who is snubbed, are permanent features of every ballroom. But Jane Austen knew it from her birth upwards. One of those fairies who perch upon cradles must have taken her a flight through the world directly she was born. When she was laid in the cradle again she knew not only what the world looked like, but had already chosen her kingdom. She had agreed that if she might rule over that territory, she would covet no other. Thus at fifteen she had few illusions about other people and none about herself. Whatever she writes is finished and turned and set in its relation, not to the parsonage, but to the universe. She is impersonal; she is inscrutable. When the writer, Jane Austen, wrote down in the most remarkable sketch in the book a little of Lady Greville’s conversation, there is no trace of anger at the snub which the clergyman’s daughter, Jane Austen, once received. Her gaze passes straight to the mark, and we know precisely where, upon the map of human nature, that mark is. We know because Jane Austen kept to her compact; she never trespassed beyond her boundaries. Never, even at the emotional age of fifteen, did she round upon herself in shame, obliterate a sarcasm in a spasm of compassion, or blur an outline in a mist of rhapsody. Spasms and rhapsodies, she seems to have said, pointing with her stick, end THERE; and the boundary line is perfectly distinct. But she does not deny that moons and mountains and castles exist — on the other side. She has even one romance of her own. It is for the Queen of Scots. She really admired her very much. “One of the first characters in the world”, she called her, “a bewitching Princess whose only friend was then the Duke of Norfolk, and whose only ones now Mr. Whitaker, Mrs. Lefroy, Mrs. Knight and myself.” With these words her passion is neatly circumscribed, and rounded with a laugh. It is amusing to remember in what terms the young Brontë‘s wrote, not very much later, in their northern parsonage, about the Duke of Wellington.

The prim little girl grew up. She became “the prettiest, silliest, most affected husband-hunting butterfly” Mrs. Mitford ever remembered, and, incidentally, the authoress of a novel called Pride and Prejudice, which, written stealthily under cover of a creaking door, lay for many years unpublished. A little later, it is thought, she began another story, The Watsons, and being for some reason dissatisfied with it, left it unfinished. The second-rate works of a great writer are worth reading because they offer the best criticism of his masterpieces. Here her difficulties are more apparent, and the method she took to overcome them less artfully concealed. To begin with, the stiffness and the bareness of the first chapters prove that she was one of those writers who lay their facts out rather baldly in the first version and then go back and back and back and cover them with flesh and atmosphere. How it would have been done we cannot say — by what suppressions and insertions and artful devices. But the miracle would have been accomplished; the dull history of fourteen years of family life would have been converted into another of those exquisite and apparently effortless introductions; and we should never have guessed what pages of preliminary drudgery Jane Austen forced her pen to go through. Here we perceive that she was no conjuror after all. Like other writers, she had to create the atmosphere in which her own peculiar genius could bear fruit. Here she fumbles; here she keeps us waiting. Suddenly she has done it; now things can happen as she likes things to happen. The Edwardses are going to the ball. The Tomlinsons’ carriage is passing; she can tell us that Charles is “being provided with his gloves and told to keep them on”; Tom Musgrave retreats to a remote corner with a barrel of oysters and is famously snug. Her genius is freed and active. At once our senses quicken; we are possessed with the peculiar intensity which she alone can impart. But of what is it all composed? Of a ball in a country town; a few couples meeting and taking hands in an assembly room; a little eating and drinking; and for catastrophe, a boy being snubbed by one young lady and kindly treated by another. There is no tragedy and no heroism. Yet for some reason the little scene is moving out of all proportion to its surface solemnity. We have been made to see that if Emma acted so in the ball-room, how considerate, how tender, inspired by what sincerity of feeling she would have shown herself in those graver crises of life which, as we watch her, come inevitably before our eyes. Jane Austen is thus a mistress of much deeper emotion than appears upon the surface. She stimulates us to supply what is not there. What she offers is, apparently, a trifle, yet is composed of something that expands in the reader’s mind and endows with the most enduring form of life scenes which are outwardly trivial. Always the stress is laid upon character. How, we are made to wonder, will Emma behave when Lord Osborne and Tom Musgrave make their call at five minutes before three, just as Mary is bringing in the tray and the knife-case? It is an extremely awkward situation. The young men are accustomed to much greater refinement. Emma may prove herself ill-bred, vulgar, a nonentity. The turns and twists of the dialogue keep us on the tenterhooks of suspense. Our attention is half upon the present moment, half upon the future. And when, in the end, Emma behaves in such a way as to vindicate our highest hopes of her, we are moved as if we had been made witnesses of a matter of the highest importance. Here, indeed, in this unfinished and in the main inferior story, are all the elements of Jane Austen’s greatness. It has the permanent quality of literature. Think away the surface animation, the likeness to life, and there remains, to provide a deeper pleasure, an exquisite discrimination of human values. Dismiss this too from the mind and one can dwell with extreme satisfaction upon the more abstract art which, in the ball-room scene, so varies the emotions and proportions the parts that it is possible to enjoy it, as one enjoys poetry, for itself, and not as a link which carries the story this way and that.

But the gossip says of Jane Austen that she was perpendicular, precise, and taciturn —“a poker of whom everybody is afraid”. Of this too there are traces; she could be merciless enough; she is one of the most consistent satirists in the whole of literature. Those first angular chapters of The Watsons prove that hers was not a prolific genius; she had not, like Emily Brontë, merely to open the door to make herself felt. Humbly and gaily she collected the twigs and straws out of which the nest was to be made and placed them neatly together. The twigs and straws were a little dry and a little dusty in themselves. There was the big house and the little house; a tea party, a dinner party, and an occasional picnic; life was hedged in by valuable connections and adequate incomes; by muddy roads, wet feet, and a tendency on the part of the ladies to get tired; a little principle supported it, a little consequence, and the education commonly enjoyed by upper middle-class families living in the country. Vice, adventure, passion were left outside. But of all this prosiness, of all this littleness, she evades nothing, and nothing is slurred over. Patiently and precisely she tells us how they “made no stop anywhere till they reached Newbury, where a comfortable meal, uniting dinner and supper, wound up the enjoyments and fatigues of the day”. Nor does she pay to conventions merely the tribute of lip homage; she believes in them besides accepting them. When she is describing a clergyman, like Edmund Bertram, or a sailor, in particular, she appears debarred by the sanctity of his office from the free use of her chief tool, the comic genius, and is apt therefore to lapse into decorous panegyric or matter-of-fact description. But these are exceptions; for the most part her attitude recalls the anonymous lady’s ejaculation —“A wit, a delineator of character, who does not talk is terrific indeed!” She wishes neither to reform nor to annihilate; she is silent; and that is terrific indeed. One after another she creates her fools, her prigs, her worldlings, her Mr. Collinses, her Sir Walter Elliotts, her Mrs. Bennets. She encircles them with the lash of a whip-like phrase which, as it runs round them, cuts out their silhouettes for ever. But there they remain; no excuse is found for them and no mercy shown them. Nothing remains of Julia and Maria Bertram when she has done with them; Lady Bertram is left “sitting and calling to Pug and trying to keep him from the flower-beds” eternally. A divine justice is meted out; Dr. Grant, who begins by liking his goose tender, ends by bringing on “apoplexy and death, by three great institutionary dinners in one week”. Sometimes it seems as if her creatures were born merely to give Jane Austen the supreme delight of slicing their heads off. She is satisfied; she is content; she would not alter a hair on anybody’s head, or move one brick or one blade of grass in a world which provides her with such exquisite delight.

Nor, indeed, would we. For even if the pangs of outraged vanity, or the heat of moral wrath, urged us to improve away a world so full of spite, pettiness, and folly, the task is beyond our powers. People are like that — the girl of fifteen knew it; the mature woman proves it. At this very moment some Lady Bertram is trying to keep Pug from the flower beds; she sends Chapman to help Miss Fanny a little late. The discrimination is so perfect, the satire so just, that, consistent though it is, it almost escapes our notice. No touch of pettiness, no hint of spite, rouse us from our contemplation. Delight strangely mingles with our amusement. Beauty illumines these fools.

That elusive quality is, indeed, often made up of very different parts, which it needs a peculiar genius to bring together. The wit of Jane Austen has for partner the perfection of her taste. Her fool is a fool, her snob is a snob, because he departs from the model of sanity and sense which she has in mind, and conveys to us unmistakably even while she makes us laugh. Never did any novelist make more use of an impeccable sense of human values. It is against the disc of an unerring heart, an unfailing good taste, an almost stern morality, that she shows up those deviations from kindness, truth, and sincerity which are among the most delightful things in English literature. She depicts a Mary Crawford in her mixture of good and bad entirely by this means. She lets her rattle on against the clergy, or in favour of a baronetage and ten thousand a year, with all the ease and spirit possible; but now and again she strikes one note of her own, very quietly, but in perfect tune, and at once all Mary Crawford’s chatter, though it continues to amuse, rings flat. Hence the depth, the beauty, the complexity of her scenes. From such contrasts there comes a beauty, a solemnity even, which are not only as remarkable as her wit, but an inseparable part of it. In The Watsons she gives us a foretaste of this power; she makes us wonder why an ordinary act of kindness, as she describes it, becomes so full of meaning. In her masterpieces, the same gift is brought to perfection. Here is nothing out of the way; it is midday in Northamptonshire; a dull young man is talking to rather a weakly young woman on the stairs as they go up to dress for dinner, with housemaids passing. But, from triviality, from commonplace, their words become suddenly full of meaning, and the moment for both one of the most memorable in their lives. It fills itself; it shines; it glows; it hangs before us, deep, trembling, serene for a second; next, the housemaid passes, and this drop, in which all the happiness of life has collected, gently subsides again to become part of the ebb and flow of ordinary existence.

What more natural, then, with this insight into their profundity, than that Jane Austen should have chosen to write of the trivialities of day-to-day existence, of parties, picnics, and country dances? No “suggestions to alter her style of writing” from the Prince Regent or Mr. Clarke could tempt her; no romance, no adventure, no politics or intrigue could hold a candle to life on a country-house staircase as she saw it. Indeed, the Prince Regent and his librarian had run their heads against a very formidable obstacle; they were trying to tamper with an incorruptible conscience, to disturb an infallible discretion. The child who formed her sentences so finely when she was fifteen never ceased to form them, and never wrote for the Prince Regent or his Librarian, but for the world at large. She knew exactly what her powers were, and what material they were fitted to deal with as material should be dealt with by a writer whose standard of finality was high. There were impressions that lay outside her province; emotions that by no stretch or artifice could be properly coated and covered by her own resources. For example, she could not make a girl talk enthusiastically of banners and chapels. She could not throw herself whole-heartedly into a romantic moment. She had all sorts of devices for evading scenes of passion. Nature and its beauties she approached in a sidelong way of her own. She describes a beautiful night without once mentioning the moon. Nevertheless, as we read the few formal phrases about “the brilliancy of an unclouded night and the contrast of the deep shade of the woods”, the night is at once as “solemn, and soothing, and lovely” as she tells us, quite simply, that it was.

The balance of her gifts was singularly perfect. Among her finished novels there are no failures, and among her many chapters few that sink markedly below the level of the others. But, after all, she died at the age of forty-two. She died at the height of her powers. She was still subject to those changes which often make the final period of a writer’s career the most interesting of all. Vivacious, irrepressible, gifted with an invention of great vitality, there can be no doubt that she would have written more, had she lived, and it is tempting to consider whether she would not have written differently. The boundaries were marked; moons, mountains, and castles lay on the other side. But was she not sometimes tempted to trespass for a minute? Was she not beginning, in her own gay and brilliant manner, to contemplate a little voyage of discovery?

Let us take Persuasion, the last completed novel, and look by its light at the books she might have written had she lived. There is a peculiar beauty and a peculiar dullness in Persuasion. The dullness is that which so often marks the transition stage between two different periods. The writer is a little bored. She has grown too familiar with the ways of her world; she no longer notes them freshly. There is an asperity in her comedy which suggests that she has almost ceased to be amused by the vanities of a Sir Walter or the snobbery of a Miss Elliott. The satire is harsh, and the comedy crude. She is no longer so freshly aware of the amusements of daily life. Her mind is not altogether on her object. But, while we feel that Jane Austen has done this before, and done it better, we also feel that she is trying to do something which she has never yet attempted. There is a new element in Persuasion, the quality, perhaps, that made Dr. Whewell fire up and insist that it was “the most beautiful of her works”. She is beginning to discover that the world is larger, more mysterious, and more romantic than she had supposed. We feel it to be true of herself when she says of Anne: “She had been forced into prudence in her youth, she learned romance as she grew older — the natural sequel of an unnatural beginning”. She dwells frequently upon the beauty and the melancholy of nature, upon the autumn where she had been wont to dwell upon the spring. She talks of the “influence so sweet and so sad of autumnal months in the country”. She marks “the tawny leaves and withered hedges”. “One does not love a place the less because one has suffered in it”, she observes. But it is not only in a new sensibility to nature that we detect the change. Her attitude to life itself is altered. She is seeing it, for the greater part of the book, through the eyes of a woman who, unhappy herself, has a special sympathy for the happiness and unhappiness of others, which, until the very end, she is forced to comment upon in silence. Therefore the observation is less of facts and more of feelings than is usual. There is an expressed emotion in the scene at the concert and in the famous talk about woman’s constancy which proves not merely the biographical fact that Jane Austen had loved, but the aesthetic fact that she was no longer afraid to say so. Experience, when it was of a serious kind, had to sink very deep, and to be thoroughly disinfected by the passage of time, before she allowed herself to deal with it in fiction. But now, in 1817, she was ready. Outwardly, too, in her circumstances, a change was imminent. Her fame had grown very slowly. “I doubt”, wrote Mr. Austen Leigh, “whether it would be possible to mention any other author of note whose personal obscurity was so complete.” Had she lived a few more years only, all that would have been altered. She would have stayed in London, dined out, lunched out, met famous people, made new friends, read, travelled, and carried back to the quiet country cottage a hoard of observations to feast upon at leisure.

And what effect would all this have had upon the six novels that Jane Austen did not write? She would not have written of crime, of passion, or of adventure. She would not have been rushed by the importunity of publishers or the flattery of friends into slovenliness or insincerity. But she would have known more. Her sense of security would have been shaken. Her comedy would have suffered. She would have trusted less (this is already perceptible in Persuasion) to dialogue and more to reflection to give us a knowledge of her characters. Those marvellous little speeches which sum up, in a few minutes’ chatter, all that we need in order to know an Admiral Croft or a Mrs. Musgrove for ever, that shorthand, hit-or-miss method which contains chapters of analysis and psychology, would have become too crude to hold all that she now perceived of the complexity of human nature. She would have devised a method, clear and composed as ever, but deeper and more suggestive, for conveying not only what people say, but what they leave unsaid; not only what they are, but what life is. She would have stood farther away from her characters, and seen them more as a group, less as individuals. Her satire, while it played less incessantly, would have been more stringent and severe. She would have been the forerunner of Henry James and of Proust — but enough. Vain are these speculations: the most perfect artist among women, the writer whose books are immortal, died “just as she was beginning to feel confidence in her own success”.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

VIII. Claudine

Un matin d’avril, vers cinq heures, Just Moravaut, garçon boucher, remonta la rue Régis et se dirigea vers l’une des entrées du marché Saint-Maur. A la même heure, Aristide Spiker, marchand de poissons, sortit de la rue du Cherche-Midi par la rue Bérite et se dirigea vers l’entrée du marché opposée à celle de la rue Gerbillon. Just et Aristide marchèrent l’un vers l’autre et, sans dire mot, se bourrèrent la face de coups de poing. Avant que l’on fut venu les séparer, Just avait un oeil gonflé comme un oeuf poché et Aristide le nez rouge comme une framboise meurtrie. On les emmena au poste, et chacun d’eux put réfléchir à son aise sur les vicissitudes et horreurs de la guerre.

Une demi-heure après que cette rixe avait mis en émoi tout le marché, la petite Claudine arriva avec sa mère, la maman Turtaine, dans une grande charrette encombrée de légumes. Claudine sauta vivement à terre, caressa le nez du cheval et se mit à courir pour se réchauffer. C’était merveille de la voir se trémousser avec son madras sur la tête, sa grosse robe de burat gris, ses manchettes de couleur et ses sabots bourrés de paille. Le soleil se levait, jaune comme ces nymphéas qui nagent sur l’eau des étangs ; la brume se dissipait, une bise glaciale sifflait dans l’air, et le vent d’automne sonnait à plein cor ses navrantes fanfares. Les maraîchers arrivaient en foule, soigneusement emmitouflés, la figure enfouie dans une casquette, le nez seul sortant tout violet des plis d’un vieux foulard, les épaules protégées du froid par une couverture de laine grise vergetée de raies noires, les mains enveloppées de gros gants verts. Les uns déchargeaient leur charrette, les autres allaient boire un petit verre chez le marchand de vin, tandis que les chevaux, enchantés de se retrouver, se frottaient les naseaux et hennissaient joyeusement.

La chaussée était encombrée de légumes et de fruits, et un grand potiron, coupé par le milieu et couché sur le dos, arrondissait sa vasque jaune sur la pourpre sombre des pivoines jetées en tas, pêle-mêle, sur le rebord du trottoir.

Trois boutiques étaient seules ouvertes, celles d’un boucher, d’un marchand de vin et d’un pharmacien. La porte vitrée du cabaret était imprégnée d’une buée qui ne laissait voir les buveurs qu’à travers un voile. Ils ressemblaient ainsi à des ombres chinoises. Ces silhouettes dansaient sur le mur et sur la porte comme sur un drap blanc, les nez se dessinaient bizarrement, les moustaches semblaient démesurées, les barbes devenaient colossales et les chapeaux se cassaient de burlesque façon. Par instants, la porte s’ouvrait, un bruit de voix s’échappait de la salle, et celui qui sortait s’enfonçait les mains dans les poches et courait bien vite à sa boutique ou à sa voiture. Tout en travaillant et buvant, on échangeait le bonjour, on se serrait la main, on gloussait, on riait. Le boucher allumait le gaz, jetait sur le dos de ses garçons des charretées de viande ; sa femme bâillait et lavait avec une éponge la table de marbre de la devanture, pendant que, suspendu par les pieds à des crocs en fer fichés au plafond, le cadavre d’un grand boeuf étalait, sous la lumière crue du gaz, le monstrueux écrin de ses viscères. La tête avait été violemment arrachée du tronc et des bouts de nerfs palpitaient encore, convulsés comme des tronçons de vers, tortillés comme des lisérés. L’estomac tout grand ouvert bâillait atrocement et dégorgeait de sa large fosse des pendeloques d’entrailles rouges. Comme en une serre chaude, une végétation merveilleuse s’épanouissait dans ce cadavre. Des lianes de veines jaillissaient de tous côtés, des ramures échevelées fusaient le long du torse, des floraisons d’intestins déployaient leurs violâtres corolles, et de gros bouquets de graisse éclataient tout blancs sur le rouge fouillis des chairs pantelantes.

Le boucher semblait émerveillé par ce spectacle, et près de lui, sur le trottoir, deux vieux paysans avaient appuyé leurs pipes l’une sur l’autre et tiraient de grosses bouffées. Leurs joues s’enflaient comme des ballons et la fumée leur sortait par les narines. Ils aspirèrent une bonne provision d’air froid pour se rafraîchir la bouche, et mirent un petit morceau de papier sur le tabac qui se prit à grésiller et dessina tout flamboyant de capricieuses arabesques sur le papier qui se consumait.

—Voyons, Claudine, dit la mère Turtaine, tu te réchaufferas aussi bien en déchargeant la voiture qu’en sautant, viens m’aider.

—Voilà, maman. Et elle se mit en face de l’aile gauche de la carriole et reçut dans les bras des bottes de fleurs et de salades.

—Dis donc, lui dit une petite paysanne à l’oreille, il paraît que Just et Aristide se sont battus, ce matin: bien sûr pour toi.

—Oh! les vilains garçons! dit Claudine, dont la petite figure devint triste; je leur avais tant recommandé d’être sages!

—ah! tu es bonne! mais ils sont comme deux coqs, ils t’aiment tous les deux, et tu ne t’es pas encore décidée à faire un choix.

—Mais je ne sais pas, moi; je les aime autant l’un que l’autre, et maman ne les aime ni l’un ni l’autre, comment veux-tu que je choisisse?

—Satanée enfant, dit la mère Turtaine, qui sauta lourdement de sa voiture, elle bavarde, elle bavarde, et l’ouvrage n’avance pas. J’aurai aussi vite fait toute seule. Voyons, Claudine, va nettoyer notre case et préparer les chaufferettes. La petite s’éloigna et continua, avec son amie, à disputer des mérites et défauts de ses deux amoureux.

La situation était en effet embarrassante, Claudine les aimait tous deux comme une soeur aimerait deux frères; mais, dame, de là à choisir entre eux un mari, il y avait loin. Just et Aristide ne se ressemblaient pas comme figure, mais chacun, dans son genre, était aussi beau ou aussi laid que l’autre. Aristide était peut-être plus bel homme, mais il témoignait d’un penchant prononcé pour l’adiposité. Just était moins bien taillé, son encolure était moins large, mais il promettait de rester musculeux, et point trivialement bardé de graisse comme son adversaire. Just avait de jolis cheveux blonds, tout frisottants, mais ils n’étaient pas fournis, et, par endroits, l’on entrevoyait sous le buisson une petite clairière. Aristide avait des cheveux blonds, roides et sans grâce, mais d’une nuance plus tendre; et puis, c’était une véritable forêt luxuriante, la raie était à peine tracée, comme un tout petit sentier dans une épaisse forêt. Tous deux étaient francs et bons, mais batailleurs; tous deux n’avaient pas de fortune, mais étaient courageux et ne reculaient pas devant l’ouvrage.

—Enfin, disait la petite Marie, en se posant devant Claudine qui tournait les rubans de son tablier d’un air indécis, cette situation-là ne peut durer, ils finiront par s’égorger. Je parlerai à ta mère, si tu n’oses.

—Oh! non je t’en prie, ne dis rien, maman me gronderait, leur dirait des sottises et leur défendrait de m’adresser la parole.

—Voyons, Claudine, nous allons peser les qualités et les défauts, les avantages et les désavantages de chacun, et puis nous verrons lequel des deux vaut le mieux! D’un côté, Aristide est un brave garçon.

—Oui! oui, pour ça, c’est un brave garçon.

—Mais sais-tu bien qu’il deviendra comme un muid? et dame! c’est bien désagréable d’avoir pour mari un homme dont tout le monde plaint la corpulence. Il est vrai, poursuivit-elle, que Just est un brave garçon.

—Oh! oui, pour ça, c’est un brave garçon.

—Bien, mais sais-tu qu’il demeurera toute sa vie maigre comme un échalas, et, ma foi, je t’avoue qu’il est bien triste de vivre tous les jours avec un homme qui a l’air de mourir de faim.

—De sorte que, reprit en souriant Claudine, le mieux serait d’épouser un mari qui ne fut ni trop gras ni trop maigre; mais alors il ne faut prendre ni Just ni Aristide.

—Ah! mais non! s’écria Marie; ces garçons t’aiment, il faut au moins que l’un des deux soit heureux.

—Chut! je me sauve, j’entends maman qui gronde.

—Ah! bien oui! disait la mère Turtaine d’une voix courroucée, les mains plantées sur les hanches, le ventre proéminent sous son tablier bleu; c’est bien la peine d’élever une jeunesse pour qu’elle écoute ainsi les ordres de sa mère! Elle n’a pas seulement balayé notre place, il n’y a pas moyen de s’y tenir tant il y a d’épluchures.

—Voyons, petite maman, ne me gronde pas, fit sa fille, en prenant un petit air câlin qui ne justifiait que trop l’amour des pauvres garçons pour elle; je ne bavarderai plus autant, je te le promets.

Elle prépara sa devanture et demeura songeuse. Elle se rappelait maintenant que les deux rivaux s’étaient battus, et que c’était pour cela que ni l’un ni l’autre n’avait balayé son petit réduit, ainsi qu’ils avaient coutume de le faire. Pourvu qu’ils ne se soient pas blessés, pensait-elle, et elle se sentait plus d’inclination pour celui qui aurait le plus souffert.

—Voyons, dit sa mère, je vais chercher notre café; que tout soit prêt quand je reviendrai, que je puisse déjeuner tranquillement.

—Est-il vrai, dit Claudine à la femme Truchart, sa voisine et tante, que l’on s’est battu ce matin ici?

—On me l’a dit; c’est deux mauvais sujets; on devrait pendre des batailleurs comme ça, ou les mettre dans l’armée, puisqu’ils aiment les coups.

Petite Claudine se tut et cessa la conversation. Un quart d’heure après, la maman arriva, tenant dans chaque main un grand bol plein d’une liqueur fumante et saumâtre.

-Ah! bien, j’en apprends de belles, cria-t-elle, il paraît que ces deux gredins de Just et d’Aristide se sont battus, ce matin, à cause de toi. Qu’ils s’avisent un peu de rôder autour de nous! c’est moi qui vais les recevoir! Et toi, si tu leur adresses la parole ou si tu réponds à leurs discours, tu auras affaire à moi. A-t-on jamais vu!

La pauvre fille avait le coeur gros et ne pouvait manger; soudain elle pâlit et renversa la moitié de son bol sur sa jupe: les deux adversaires venaient d’entrer dans le marché, l’un avec son oeil bleu, l’autre avec son nez tout escarbouillé. Ils se séparèrent à la porte et chacun s’en fut à sa boutique par une allée différente.

Toute la journée, elle les regardait alternativement, se disant: Le pauvre garçon, comme il doit souffrir avec son visage enflé! Ce nez turgide et sanglant la désespérait. Puis elle regardait l’autre. A-t-il l’oeil abîmé! murmurait-elle. Et cet oeil qui débordait d’un cercle de charbon lui faisait passer de petits frissons dans le dos. Faut-il qu’un homme soit brutal, pensait-elle, pour frapper ainsi un ami aux yeux. Elle se prenait à détester Aristide, puis elle voyait ce nez turgescent, et elle en venait à exécrer le gros Just. Elle y songea toute la nuit et ne put dormir. Que faire, pensait-elle, que faire ? Ce n’est pas de leur faute s’ils m’aiment. Je tâcherai de leur parler demain et je leur ferai promettre de ne plus se battre. Elle s’endormit sur cette heureuse idée et prépara, dans sa petite cervelle, de belles paroles pour les apaiser. Elle s’habilla, le matin, toute songeuse, aida sa mère à atteler le cheval et chemin faisant, de Montrouge au marché, elle repassa son petit discours. La difficulté était de leur parler sans être vue par sa mère. Elle s’ingéniait à trouver des prétextes pour s’échapper un instant de la boutique et parler à chacun d’eux sans être vue par l’autre. Enfin, le hasard me fournira peut-être une occasion et, sur cette pensée consolante, elle fouetta vivement le cheval qui prit le petit trot et fit sonner, dans les rues endormies, les semelles de fer qu’il avait aux pieds.

Les deux rivaux étaient à leur place et se jetaient des regards défiants. Elle eut l’air de ne point les voir, déchargea la voiture et se promit, vers neuf heures, alors que le marché serait rempli de monde, de s’échapper. En effet, vers cette heure, une affluence de femmes mal peignées, couvertes de châles effilochés, jetant un regard de joie sur leurs chiens qui folâtraient dans les ruisseaux, inonda les rues étroites qui enserrent le marché. Sous prétexte de chercher une botte de persil qu’elle avait égarée, Claudine se faufila dans la foule et s’en fut à la boutique de Just. Il pâlit à sa vue, rougit subitement et son oeil devint d’un noir plus foncé; sa boutique était encombrée de clientes, il leur répondait à peine, avait grande envie de les envoyer au diable et n’osait le faire, attendu que son patron était là et le surveillait du coin de l’oeil. «Just,» lui dit-elle enfin à voix basse, oubliant toutes les belles phrases qu’elle avait préparées, promettez-moi de ne plus vous battre.

—Mais, mademoiselle…

—Promettez-moi, ou je me fâche pour toujours avec vous.

—Je vous le promets, dit-il, tout rouge.

—Merci. Et elle se sauva en courant et rentra chez sa mère. Un quart d’heure après, elle parvint également à s’enfuir et s’en fut trouver Aristide qui la regarda d’un air effaré, vacilla sur ses jambes, balbutia quelques mots et fut obligé de s’asseoir, au grand ébahissement des acheteuses, qui crurent qu’il se trouvait mal et se mirent à crier. Elle n’eut que le temps de se sauver. «Mon Dieu! mon Dieu!» murmurait-elle, «quel malheur! Je n’ai pourtant rien fait pour qu’ils m’aiment comme cela, ces pauvres garçons!»

Vers midi, Just s’en vint rôder autour d’elle et lui glissa un petit mot qu’elle s’en fut ouvrir dans la rue: «Je ne puis vivre ainsi, disait-il, je vais vendre mon fonds et quitter le marché. «Ah!» s’écria-t-elle, «celui-ci m’aime le plus; si maman veut, je l’épouse.» Un quart d’heure après, comme elle allait chercher du cerfeuil chez une amie, Aristide lui dit: «Mademoiselle Claudine, je vais m’en aller, je suis trop mal heureux.»

—Ah! mon Dieu! il m’aime autant que l’autre; c’est désespérant d’être aimée ainsi! Et, tout en disant cela, elle éprouvait, malgré elle, une certaine joie à se sentir ainsi adorée.

Elle revint plus perplexe encore. Que faire? Telle était la question qu’elle se posait sans cesse. En attendant, les jours passaient et les amoureux ne partaient pas. Le premier qui partira sera celui qui m’aimera le plus, pensait-elle; puis elle se reprenait et se disait tout bas: Non, celui qui me quittera le premier pourra vivre sans me voir, donc il m’aimera moins. En attendant, chacun restait à sa place, s’étant fait cette réflexion bien simple que partir c’était laisser le champ libre à son adversaire, qui ne partirait certainement pas. Donc, ils s’observaient et éprouvaient de furieuses tentations de se cribler la figure de nouvelles gourmades.

Malheureusement, cet amour insensé que les petits yeux et les bonnes joues de Claudine avaient allumé dans le coeur des pauvres garçons fut bientôt connu de tout le quartier. Le coiffeur d’en face, enchanté d’avoir une occasion de parler, en promenant ses mains graisseuses et son rasoir non moins graisseux sur la figure de ses clients, entra dans d’interminables discussions sur la beauté et la coquetterie de Claudine. Ces propos, grossissant à mesure qu’ils roulaient de bouche en bouche, ne devaient pas tarder à arriver aux oreilles de la mère Turtaine. Un marché, c’est une miniature de ville de province: on y passe son temps à médire de son prochain et à le piller autant que faire se peut, deux occupations agréables, si jamais il en fut. Les concierges du quartier, las de se plaindre de leurs locataires et de déplorer le sort qui les avait faits concierges, saisirent cette occasion d’interrompre leurs doléances et s’empressèrent de dire pis que pendre de la pauvre fille. Exaspérée par tous ces commérages et par toutes ces médisances, la mère Turtaine résolut de l’envoyer chez sa soeur, à Plaisir, dans le département de Seine-et-Oise.

Claudine partit le coeur gros en priant sa mère de la rappeler bientôt près d’elle. Les premiers jours lui semblèrent bien tristes et elle écrivit à sa mère une lettre dans laquelle elle la suppliait de lui permettre de revenir au marché. Bientôt cette lettre qu’elle désirait tant lui causa de terribles craintes. En quelques soirées son sort avait changé. Un soir qu’elle se promenait près de la tremblaie, elle fit rencontre d’un grand et beau garçon dont la mine éveillée et les allures puissantes lui plurent tout d’abord.

La première fois, il la regarda timidement et, sentant les yeux de la jeune fille fixés sur les siens, il baissa la tête, devint rouge du cou aux oreilles et ne put ouvrir la bouche; la seconde fois, il osa l’aborder, mais il balbutia comme un imbécile et devint plus rouge encore que la première fois; la troisième, il ouvrit la bouche, parvint à bredouiller quelques mots, à lui dire qu’il la connaissait, que son père était un grand ami de sa mère, et, depuis ce temps, ils étaient devenus les meilleurs amis du monde.