Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

George Eliot

To read George Eliot attentively is to become aware how little one knows about her. It is also to become aware of the credulity, not very creditable to one’s insight, with which, half consciously and partly maliciously, one had accepted the late Victorian version of a deluded woman who held phantom sway over subjects even more deluded than herself. At what moment and by what means her spell was broken it is difficult to ascertain. Some people attribute it to the publication of her Life. Perhaps George Meredith, with his phrase about the “mercurial little showman” and the “errant woman” on the daïs, gave point and poison to the arrows of thousands incapable of aiming them so accurately, but delighted to let fly. She became one of the butts for youth to laugh at, the convenient symbol of a group of serious people who were all guilty of the same idolatry and could be dismissed with the same scorn. Lord Acton had said that she was greater than Dante; Herbert Spencer exempted her novels, as if they were not novels, when he banned all fiction from the London Library. She was the pride and paragon of her sex. Moreover, her private record was not more alluring than her public. Asked to describe an afternoon at the Priory, the story-teller always intimated that the memory of those serious Sunday afternoons had come to tickle his sense of humour. He had been so much alarmed by the grave lady in her low chair; he had been so anxious to say the intelligent thing. Certainly, the talk had been very serious, as a note in the fine clear hand of the great novelist bore witness. It was dated on the Monday morning, and she accused herself of having spoken without due forethought of Marivaux when she meant another; but no doubt, she said, her listener had already supplied the correction. Still, the memory of talking about Marivaux to George Eliot on a Sunday afternoon was not a romantic memory. It had faded with the passage of the years. It had not become picturesque.

Indeed, one cannot escape the conviction that the long, heavy face with its expression of serious and sullen and almost equine power has stamped itself depressingly upon the minds of people who remember George Eliot, so that it looks out upon them from her pages. Mr. Gosse has lately described her as he saw her driving through London in a victoria:

a large, thick-set sybil, dreamy and immobile, whose massive features, somewhat grim when seen in profile, were incongruously bordered by a hat, always in the height of Paris fashion, which in those days commonly included an immense ostrich feather.

Lady Ritchie, with equal skill, has left a more intimate indoor portrait:

She sat by the fire in a beautiful black satin gown, with a green shaded lamp on the table beside her, where I saw German books lying and pamphlets and ivory paper-cutters. She was very quiet and noble, with two steady little eyes and a sweet voice. As I looked I felt her to be a friend, not exactly a personal friend, but a good and benevolent impulse.

A scrap of her talk is preserved. “We ought to respect our influence,” she said. “We know by our own experience how very much others affect our lives, and we must remember that we in turn must have the same effect upon others.” Jealously treasured, committed to memory, one can imagine recalling the scene, repeating the words, thirty years later and suddenly, for the first time, bursting into laughter.

In all these records one feels that the recorder, even when he was in the actual presence, kept his distance and kept his head, and never read the novels in later years with the light of a vivid, or puzzling, or beautiful personality dazzling in his eyes. In fiction, where so much of personality is revealed, the absence of charm is a great lack; and her critics, who have been, of course, mostly of the opposite sex, have resented, half consciously perhaps, her deficiency in a quality which is held to be supremely desirable in women. George Eliot was not charming; she was not strongly feminine; she had none of those eccentricities and inequalities of temper which give to so many artists the endearing simplicity of children. One feels that to most people, as to Lady Ritchie, she was “not exactly a personal friend, but a good and benevolent impulse”. But if we consider these portraits more closely we shall find that they are all the portraits of an elderly celebrated woman, dressed in black satin, driving in her victoria, a woman who has been through her struggle and issued from it with a profound desire to be of use to others, but with no wish for intimacy, save with the little circle who had known her in the days of her youth. We know very little about the days of her youth; but we do know that the culture, the philosophy, the fame, and the influence were all built upon a very humble foundation — she was the grand-daughter of a carpenter.

The first volume of her life is a singularly depressing record. In it we see her raising herself with groans and struggles from the intolerable boredom of petty provincial society (her father had risen in the world and become more middle class, but less picturesque) to be the assistant editor of a highly intellectual London review, and the esteemed companion of Herbert Spencer. The stages are painful as she reveals them in the sad soliloquy in which Mr. Cross condemned her to tell the story of her life. Marked in early youth as one “sure to get something up very soon in the way of a clothing club”, she proceeded to raise funds for restoring a church by making a chart of ecclesiastical history; and that was followed by a loss of faith which so disturbed her father that he refused to live with her. Next came the struggle with the translation of Strauss, which, dismal and “soul-stupefying” in itself, can scarcely have been made less so by the usual feminine tasks of ordering a household and nursing a dying father, and the distressing conviction, to one so dependent upon affection, that by becoming a blue-stocking she was forfeiting her brother’s respect. “I used to go about like an owl,” she said, “to the great disgust of my brother.” “Poor thing,” wrote a friend who saw her toiling through Strauss with a statue of the risen Christ in front of her, “I do pity her sometimes, with her pale sickly face and dreadful headaches, and anxiety, too, about her father.” Yet, though we cannot read the story without a strong desire that the stages of her pilgrimage might have been made, if not more easy, at least more beautiful, there is a dogged determination in her advance upon the citadel of culture which raises it above our pity. Her development was very slow and very awkward, but it had the irresistible impetus behind it of a deep-seated and noble ambition. Every obstacle at length was thrust from her path. She knew every one. She read everything. Her astonishing intellectual vitality had triumphed. Youth was over, but youth had been full of suffering. Then, at the age of thirty-five, at the height of her powers, and in the fulness of her freedom, she made the decision which was of such profound moment to her and still matters even to us, and went to Weimar, alone with George Henry Lewes.

The books which followed so soon after her union testify in the fullest manner to the great liberation which had come to her with personal happiness. In themselves they provide us with a plentiful feast. Yet at the threshold of her literary career one may find in some of the circumstances of her life influences that turned her mind to the past, to the country village, to the quiet and beauty and simplicity of childish memories and away from herself and the present. We understand how it was that her first book was Scenes of Clerical Life, and not Middlemarch. Her union with Lewes had surrounded her with affection, but in view of the circumstances and of the conventions it had also isolated her. “I wish it to be understood”, she wrote in 1857, “that I should never invite any one to come and see me who did not ask for the invitation.” She had been “cut off from what is called the world”, she said later, but she did not regret it. By becoming thus marked, first by circumstances and later, inevitably, by her fame, she lost the power to move on equal terms unnoted among her kind; and the loss for a novelist was serious. Still, basking in the light and sunshine of Scenes of Clerical Life, feeling the large mature mind spreading itself with a luxurious sense of freedom in the world of her “remotest past”, to speak of loss seems inappropriate. Everything to such a mind was gain. All experience filtered down through layer after layer of perception and reflection, enriching and nourishing. The utmost we can say, in qualifying her attitude towards fiction by what little we know of her life, is that she had taken to heart certain lessons not usually learnt early, if learnt at all, among which, perhaps, the most branded upon her was the melancholy virtue of tolerance; her sympathies are with the everyday lot, and play most happily in dwelling upon the homespun of ordinary joys and sorrows. She has none of that romantic intensity which is connected with a sense of one’s own individuality, unsated and unsubdued, cutting its shape sharply upon the background of the world. What were the loves and sorrows of a snuffy old clergyman, dreaming over his whisky, to the fiery egotism of Jane Eyre? The beauty of those first books, Scenes of Clerical Life, Adam Bede, The Mill on the Floss, is very great. It is impossible to estimate the merit of the Poysers, the Dodsons, the Gilfils, the Bartons, and the rest with all their surroundings and dependencies, because they have put on flesh and blood and we move among them, now bored, now sympathetic, but always with that unquestioning acceptance of all that they say and do, which we accord to the great originals only. The flood of memory and humour which she pours so spontaneously into one figure, one scene after another, until the whole fabric of ancient rural England is revived, has so much in common with a natural process that it leaves us with little consciousness that there is anything to criticise. We accept; we feel the delicious warmth and release of spirit which the great creative writers alone procure for us. As one comes back to the books after years of absence they pour out, even against our expectation, the same store of energy and heat, so that we want more than anything to idle in the warmth as in the sun beating down from the red orchard wall. If there is an element of unthinking abandonment in thus submitting to the humours of Midland farmers and their wives, that, too, is right in the circumstances. We scarcely wish to analyse what we feel to be so large and deeply human. And when we consider how distant in time the world of Shepperton and Hayslope is, and how remote the minds of farmer and agricultural labourers from those of most of George Eliot’s readers, we can only attribute the ease and pleasure with which we ramble from house to smithy, from cottage parlour to rectory garden, to the fact that George Eliot makes us share their lives, not in a spirit of condescension or of curiosity, but in a spirit of sympathy. She is no satirist. The movement of her mind was too slow and cumbersome to lend itself to comedy. But she gathers in her large grasp a great bunch of the main elements of human nature and groups them loosely together with a tolerant and wholesome understanding which, as one finds upon re-reading, has not only kept her figures fresh and free, but has given them an unexpected hold upon our laughter and tears. There is the famous Mrs. Poyser. It would have been easy to work her idiosyncrasies to death, and, as it is, perhaps, George Eliot gets her laugh in the same place a little too often. But memory, after the book is shut, brings out, as sometimes in real life, the details and subtleties which some more salient characteristic has prevented us from noticing at the time. We recollect that her health was not good. There were occasions upon which she said nothing at all. She was patience itself with a sick child. She doted upon Totty. Thus one can muse and speculate about the greater number of George Eliot’s characters and find, even in the least important, a roominess and margin where those qualities lurk which she has no call to bring from their obscurity.

But in the midst of all this tolerance and sympathy there are, even in the early books, moments of greater stress. Her humour has shown itself broad enough to cover a wide range of fools and failures, mothers and children, dogs and flourishing midland fields, farmers, sagacious or fuddled over their ale, horse-dealers, inn-keepers, curates, and carpenters. Over them all broods a certain romance, the only romance that George Eliot allowed herself — the romance of the past. The books are astonishingly readable and have no trace of pomposity or pretence. But to the reader who holds a large stretch of her early work in view it will become obvious that the mist of recollection gradually withdraws. It is not that her power diminishes, for, to our thinking, it is at its highest in the mature Middlemarch, the magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels written for grown-up people. But the world of fields and farms no longer contents her. In real life she had sought her fortunes elsewhere; and though to look back into the past was calming and consoling, there are, even in the early works, traces of that troubled spirit, that exacting and questioning and baffled presence who was George Eliot herself. In Adam Bede there is a hint of her in Dinah. She shows herself far more openly and completely in Maggie in The Mill on the Floss. She is Janet in Janet’s Repentance, and Romola, and Dorothea seeking wisdom and finding one scarcely knows what in marriage with Ladislaw. Those who fall foul of George Eliot do so, we incline to think, on account of her heroines; and with good reason; for there is no doubt that they bring out the worst of her, lead her into difficult places, make her self-conscious, didactic, and occasionally vulgar. Yet if you could delete the whole sisterhood you would leave a much smaller and a much inferior world, albeit a world of greater artistic perfection and far superior jollity and comfort. In accounting for her failure, in so far as it was a failure, one recollects that she never wrote a story until she was thirty-seven, and that by the time she was thirty-seven she had come to think of herself with a mixture of pain and something like resentment. For long she preferred not to think of herself at all. Then, when the first flush of creative energy was exhausted and self-confidence had come to her, she wrote more and more from the personal standpoint, but she did so without the unhesitating abandonment of the young. Her self-consciousness is always marked when her heroines say what she herself would have said. She disguised them in every possible way. She granted them beauty and wealth into the bargain; she invented, more improbably, a taste for brandy. But the disconcerting and stimulating fact remained that she was compelled by the very power of her genius to step forth in person upon the quiet bucolic scene.

The noble and beautiful girl who insisted upon being born into the Mill on the Floss is the most obvious example of the ruin which a heroine can strew about her. Humour controls her and keeps her lovable so long as she is small and can be satisfied by eloping with the gipsies or hammering nails into her doll; but she develops; and before George Eliot knows what has happened she has a full-grown woman on her hands demanding what neither gipsies, nor dolls, nor St. Ogg’s itself is capable of giving her. First Philip Wakem is produced, and later Stephen Guest. The weakness of the one and the coarseness of the other have often been pointed out; but both, in their weakness and coarseness, illustrate not so much George Eliot’s inability to draw the portrait of a man, as the uncertainty, the infirmity, and the fumbling which shook her hand when she had to conceive a fit mate for a heroine. She is in the first place driven beyond the home world she knew and loved, and forced to set foot in middle-class drawing-rooms where young men sing all the summer morning and young women sit embroidering smoking-caps for bazaars. She feels herself out of her element, as her clumsy satire of what she calls “good society” proves.

Good society has its claret and its velvet carpets, its dinner engagements six weeks deep, its opera, and its faery ball rooms . . . gets its science done by Faraday and its religion by the superior clergy who are to be met in the best houses; how should it have need of belief and emphasis?

There is no trace of humour or insight there, but only the vindictiveness of a grudge which we feel to be personal in its origin. But terrible as the complexity of our social system is in its demands upon the sympathy and discernment of a novelist straying across the boundaries, Maggie Tulliver did worse than drag George Eliot from her natural surroundings. She insisted upon the introduction of the great emotional scene. She must love; she must despair; she must be drowned clasping her brother in her arms. The more one examines the great emotional scenes the more nervously one anticipates the brewing and gathering and thickening of the cloud which will burst upon our heads at the moment of crisis in a shower of disillusionment and verbosity. It is partly that her hold upon dialogue, when it is not dialect, is slack; and partly that she seems to shrink with an elderly dread of fatigue from the effort of emotional concentration. She allows her heroines to talk too much. She has little verbal felicity. She lacks the unerring taste which chooses one sentence and compresses the heart of the scene within that. “Whom are you going to dance with?” asked Mr. Knightley, at the Westons’ ball. “With you, if you will ask me,” said Emma; and she has said enough. Mrs. Casaubon would have talked for an hour and we should have looked out of the window.

Yet, dismiss the heroines without sympathy, confine George Eliot to the agricultural world of her “remotest past”, and you not only diminish her greatness but lose her true flavour. That greatness is here we can have no doubt. The width of the prospect, the large strong outlines of the principal features, the ruddy light of the early books, the searching power and reflective richness of the later tempt us to linger and expatiate beyond our limits. But it is upon the heroines that we would cast a final glance. “I have always been finding out my religion since I was a little girl,” says Dorothea Casaubon. “I used to pray so much — now I hardly ever pray. I try not to have desires merely for myself. . . .” She is speaking for them all. That is their problem. They cannot live without religion, and they start out on the search for one when they are little girls. Each has the deep feminine passion for goodness, which makes the place where she stands in aspiration and agony the heart of the book — still and cloistered like a place of worship, but that she no longer knows to whom to pray. In learning they seek their goal; in the ordinary tasks of womanhood; in the wider service of their kind. They do not find what they seek, and we cannot wonder. The ancient consciousness of woman, charged with suffering and sensibility, and for so many ages dumb, seems in them to have brimmed and overflowed and uttered a demand for something — they scarcely know what — for something that is perhaps incompatible with the facts of human existence. George Eliot had far too strong an intelligence to tamper with those facts, and too broad a humour to mitigate the truth because it was a stern one. Save for the supreme courage of their endeavour, the struggle ends, for her heroines, in tragedy, or in a compromise that is even more melancholy. But their story is the incomplete version of the story of George Eliot herself. For her, too, the burden and the complexity of womanhood were not enough; she must reach beyond the sanctuary and pluck for herself the strange bright fruits of art and knowledge. Clasping them as few women have ever clasped them, she would not renounce her own inheritance — the difference of view, the difference of standard — nor accept an inappropriate reward. Thus we behold her, a memorable figure, inordinately praised and shrinking from her fame, despondent, reserved, shuddering back into the arms of love as if there alone were satisfaction and, it might be, justification, at the same time reaching out with “a fastidious yet hungry ambition” for all that life could offer the free and inquiring mind and confronting her feminine aspirations with the real world of men. Triumphant was the issue for her, whatever it may have been for her creations, and as we recollect all that she dared and achieved, how with every obstacle against her — sex and health and convention — she sought more knowledge and more freedom till the body, weighted with its double burden, sank worn out, we must lay upon her grave whatever we have it in our power to bestow of laurel and rose.

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 526

Juistheid van uitdrukking… o, ‘t is zoo moeielyk! Ik zie nu reeds dat ik in 522 niet juist zeide, wat ik bedoelde. Ik beweer niet, een der beste schryvers te zyn – of de beste – maar geloof dat er weinigen of geenen zyn, die zoo goed schryven als ik, juist omdat ik geen schryver ben. De gil der moeder in dat sprookje uit de minnebrieven, was ‘zoo mooi,’ juist omdat zy geen actrice was. Zoo ‘mooi’ zou iedere welgeaarde moeder gillen, als ze haar kind in nood zag, maar ze zou ‘t weldra verleeren op de planken, als ze gillen moest op de maat. En zonder gillen – want, onder ons, ik houd er niet van – zelfs de meest gewone uitdrukking van ‘t dagelyksch leven, gaat het meest geroemd schryverstalent te-boven in waarheid. Wie ‘t minst schryver is, schryft het best, en m’n betuiging dat ik zoo hoog loop met myn schryvery, komt eigenlyk hierop neêr, dat ik erken geen schryver te wezen. Die Havelaar – ik meen ‘t boek – is my een walg, en ik kan dit niet beter uitdrukken dan – zoo als ik mondeling meermalen deed – hun die my verzekeren: dat werk ‘met zooveel genoegen te hebben gelezen’ te antwoorden:

– Dan ben je een ellendeling!

En waar een heel publiek zich schuldig maakt aan ‘t scheppen van ‘genoegen’ in zooveel leed… daar antwoord ik, zoo-als ik deed in ‘t eerste werk dat er van my verscheen, nà dien opgang:

‘Publiek, ik veracht u met groote innigheid.’

Die impresario uit het sprookje wachtte nog met z’n gemeen mooi-vinden, tot het kind gered was.

Hy stoorde de moeder niet in ‘t redden. Hy vergenoegde zich met niet-helpen, met stompzinnige hardhartigheid… en, après tout, hy bood de vrouw wat aan, al was ‘t dan ook niet wat zy noodig had. De man was alleen schuldig aan miskenning van gevoel, en z’n wreedheid was maar dom.

Maar wanneer-i z’n bewondering over ‘t gillen gebruikt had als beweegreden om moeder en kind onder water te houden? Indien hy gezegd had:

– Je gilt ‘mooi’ dus: verzuip, jy en je kind!

Hoe zoudt ge dàt hebben gevonden, gy ééne lezer?

Nederlanders, als ge ‘t woord ‘verzuipen’ plat vindt – een woord dat nooit over myn lippen kwam, want ik ben zoo grof niet – bedenkt dat ik tot u spreek, tot u, gy die erger dingen kunt verduwen dan gemeene woorden. Gemeene daden storen de digestie uwer zielen niet, en daarop o.a. doelde ik in 338, toen ik de Natuur bedankte voor de wyze regeling der spysvertering. Ik leende u niet gaarne de maag van myn ziel.

Ieder ziet hier, dat ik geen schryver ben. Een schryver legt zich toe op behagen. Een schryver is coquet. Een schryver is ‘n hoer. En wie nu, als ik, zich toelegde op eenvoudige meêdeeling van wat er omgaat in z’n gemoed, zonder te denken aan schryvery, zou weldra ‘even mooi’ schryven als ik. ‘Greift nur hinein, in ‘s volle menschenleben!’ Juist, Göthe!

Goed. Maar daarby behoort, dat men dat ingrypen dan ook doe in oogenblikken waarin ‘t ons schikt, in stemmingen die ons bekwaam maken om dezen of genen indruk optevangen en weêrtegeven. Het zit niet alleen in de keus van ons onderwerp – dat volle menschenleven! – maar tevens in ons ‘grypen.’ Daar ik nu op eenmaal geen lust had, langer te grypen in de volheid van ‘t avendje by den weduwnaar, laat ik hèm, Klaas, juffie-Laps, Sertrude en de bywyven van David los, ga wat wandelen, en geef u hier den herdruk van een betoog der stelling dat ik geen schryver ben. Denk nu maar onder ‘t lezen, dat ik bezig ben met vloeken tegen al de 999 lezers, die ook dàt betoog alweêr niet hebben begrepen. Maar eenmaal zal men ‘t begrypen, en inzien dat het myn verachting rechtvaardigt. (122)

kempis poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

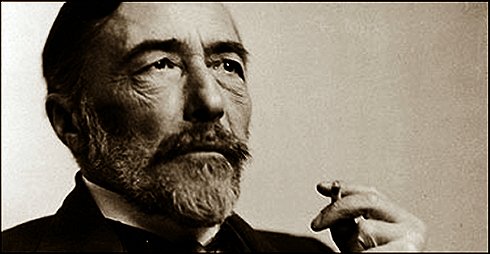

Joseph Conrad

(1857-1924)

The Lagoon

The white man, leaning with both arms over the roof of the little house

in the stern of the boat, said to the steersman–

“We will pass the night in Arsat’s clearing. It is late.”

The Malay only grunted, and went on looking fixedly at the river. The

white man rested his chin on his crossed arms and gazed at the wake

of the boat. At the end of the straight avenue of forests cut by the

intense glitter of the river, the sun appeared unclouded and dazzling,

poised low over the water that shone smoothly like a band of metal. The

forests, sombre and dull, stood motionless and silent on each side of

the broad stream. At the foot of big, towering trees, trunkless nipa

palms rose from the mud of the bank, in bunches of leaves enormous

and heavy, that hung unstirring over the brown swirl of eddies. In the

stillness of the air every tree, every leaf, every bough, every tendril

of creeper and every petal of minute blossoms seemed to have been

bewitched into an immobility perfect and final. Nothing moved on

the river but the eight paddles that rose flashing regularly, dipped

together with a single splash; while the steersman swept right and left

with a periodic and sudden flourish of his blade describing a glinting

semicircle above his head. The churned-up water frothed alongside with

a confused murmur. And the white man’s canoe, advancing upstream in the

short-lived disturbance of its own making, seemed to enter the portals

of a land from which the very memory of motion had forever departed.

The white man, turning his back upon the setting sun, looked along the

empty and broad expanse of the sea-reach. For the last three miles of

its course the wandering, hesitating river, as if enticed irresistibly

by the freedom of an open horizon, flows straight into the sea, flows

straight to the east–to the east that harbours both light and darkness.

Astern of the boat the repeated call of some bird, a cry discordant and

feeble, skipped along over the smooth water and lost itself, before it

could reach the other shore, in the breathless silence of the world.

The steersman dug his paddle into the stream, and held hard with

stiffened arms, his body thrown forward. The water gurgled aloud; and

suddenly the long straight reach seemed to pivot on its centre, the

forests swung in a semicircle, and the slanting beams of sunset touched

the broadside of the canoe with a fiery glow, throwing the slender and

distorted shadows of its crew upon the streaked glitter of the river.

The white man turned to look ahead. The course of the boat had been

altered at right-angles to the stream, and the carved dragon-head of its

prow was pointing now at a gap in the fringing bushes of the bank. It

glided through, brushing the overhanging twigs, and disappeared from the

river like some slim and amphibious creature leaving the water for its

lair in the forests.

The narrow creek was like a ditch: tortuous, fabulously deep; filled

with gloom under the thin strip of pure and shining blue of the heaven.

Immense trees soared up, invisible behind the festooned draperies of

creepers. Here and there, near the glistening blackness of the water,

a twisted root of some tall tree showed amongst the tracery of small

ferns, black and dull, writhing and motionless, like an arrested snake.

The short words of the paddlers reverberated loudly between the thick

and sombre walls of vegetation. Darkness oozed out from between the

trees, through the tangled maze of the creepers, from behind the

great fantastic and unstirring leaves; the darkness, mysterious and

invincible; the darkness scented and poisonous of impenetrable forests.

The men poled in the shoaling water. The creek broadened, opening out

into a wide sweep of a stagnant lagoon. The forests receded from the

marshy bank, leaving a level strip of bright green, reedy grass to frame

the reflected blueness of the sky. A fleecy pink cloud drifted high

above, trailing the delicate colouring of its image under the floating

leaves and the silvery blossoms of the lotus. A little house, perched

on high piles, appeared black in the distance. Near it, two tall nibong

palms, that seemed to have come out of the forests in the background,

leaned slightly over the ragged roof, with a suggestion of sad

tenderness and care in the droop of their leafy and soaring heads.

The steersman, pointing with his paddle, said, “Arsat is there. I see

his canoe fast between the piles.”

The polers ran along the sides of the boat glancing over their shoulders

at the end of the day’s journey. They would have preferred to spend the

night somewhere else than on this lagoon of weird aspect and ghostly

reputation. Moreover, they disliked Arsat, first as a stranger, and also

because he who repairs a ruined house, and dwells in it, proclaims

that he is not afraid to live amongst the spirits that haunt the places

abandoned by mankind. Such a man can disturb the course of fate by

glances or words; while his familiar ghosts are not easy to propitiate

by casual wayfarers upon whom they long to wreak the malice of their

human master. White men care not for such things, being unbelievers and

in league with the Father of Evil, who leads them unharmed through the

invisible dangers of this world. To the warnings of the righteous they

oppose an offensive pretence of disbelief. What is there to be done?

So they thought, throwing their weight on the end of their long poles.

The big canoe glided on swiftly, noiselessly, and smoothly, towards

Arsat’s clearing, till, in a great rattling of poles thrown down, and

the loud murmurs of “Allah be praised!” it came with a gentle knock

against the crooked piles below the house.

The boatmen with uplifted faces shouted discordantly, “Arsat! O Arsat!”

Nobody came. The white man began to climb the rude ladder giving access

to the bamboo platform before the house. The juragan of the boat said

sulkily, “We will cook in the sampan, and sleep on the water.”

“Pass my blankets and the basket,” said the white man, curtly.

He knelt on the edge of the platform to receive the bundle. Then the

boat shoved off, and the white man, standing up, confronted Arsat,

who had come out through the low door of his hut. He was a man young,

powerful, with broad chest and muscular arms. He had nothing on but

his sarong. His head was bare. His big, soft eyes stared eagerly at

the white man, but his voice and demeanour were composed as he asked,

without any words of greeting–

“Have you medicine, Tuan?”

“No,” said the visitor in a startled tone. “No. Why? Is there sickness

in the house?”

“Enter and see,” replied Arsat, in the same calm manner, and turning

short round, passed again through the small doorway. The white man,

dropping his bundles, followed.

In the dim light of the dwelling he made out on a couch of bamboos a

woman stretched on her back under a broad sheet of red cotton cloth.

She lay still, as if dead; but her big eyes, wide open, glittered in the

gloom, staring upwards at the slender rafters, motionless and unseeing.

She was in a high fever, and evidently unconscious. Her cheeks were sunk

slightly, her lips were partly open, and on the young face there was the

ominous and fixed expression–the absorbed, contemplating expression of

the unconscious who are going to die. The two men stood looking down at

her in silence.

“Has she been long ill?” asked the traveller.

“I have not slept for five nights,” answered the Malay, in a deliberate

tone. “At first she heard voices calling her from the water and

struggled against me who held her. But since the sun of to-day rose she

hears nothing–she hears not me. She sees nothing. She sees not me–me!”

He remained silent for a minute, then asked softly–

“Tuan, will she die?”

“I fear so,” said the white man, sorrowfully. He had known Arsat years

ago, in a far country in times of trouble and danger, when no friendship

is to be despised. And since his Malay friend had come unexpectedly to

dwell in the hut on the lagoon with a strange woman, he had slept many

times there, in his journeys up and down the river. He liked the man who

knew how to keep faith in council and how to fight without fear by the

side of his white friend. He liked him–not so much perhaps as a man

likes his favourite dog–but still he liked him well enough to help and

ask no questions, to think sometimes vaguely and hazily in the midst of

his own pursuits, about the lonely man and the long-haired woman with

audacious face and triumphant eyes, who lived together hidden by the

forests–alone and feared.

The white man came out of the hut in time to see the enormous

conflagration of sunset put out by the swift and stealthy shadows that,

rising like a black and impalpable vapour above the tree-tops, spread

over the heaven, extinguishing the crimson glow of floating clouds and

the red brilliance of departing daylight. In a few moments all the stars

came out above the intense blackness of the earth and the great lagoon

gleaming suddenly with reflected lights resembled an oval patch of night

sky flung down into the hopeless and abysmal night of the wilderness.

The white man had some supper out of the basket, then collecting a

few sticks that lay about the platform, made up a small fire, not

for warmth, but for the sake of the smoke, which would keep off the

mosquitos. He wrapped himself in the blankets and sat with his back

against the reed wall of the house, smoking thoughtfully.

Arsat came through the doorway with noiseless steps and squatted down by

the fire. The white man moved his outstretched legs a little.

“She breathes,” said Arsat in a low voice, anticipating the expected

question. “She breathes and burns as if with a great fire. She speaks

not; she hears not–and burns!”

He paused for a moment, then asked in a quiet, incurious tone–

“Tuan . . . will she die?”

The white man moved his shoulders uneasily and muttered in a hesitating

manner–

“If such is her fate.”

“No, Tuan,” said Arsat, calmly. “If such is my fate. I hear, I see,

I wait. I remember . . . Tuan, do you remember the old days? Do you

remember my brother?”

“Yes,” said the white man. The Malay rose suddenly and went in. The

other, sitting still outside, could hear the voice in the hut. Arsat

said: “Hear me! Speak!” His words were succeeded by a complete silence.

“O Diamelen!” he cried, suddenly. After that cry there was a deep sigh.

Arsat came out and sank down again in his old place.

They sat in silence before the fire. There was no sound within the

house, there was no sound near them; but far away on the lagoon they

could hear the voices of the boatmen ringing fitful and distinct on

the calm water. The fire in the bows of the sampan shone faintly in the

distance with a hazy red glow. Then it died out. The voices ceased.

The land and the water slept invisible, unstirring and mute. It was as

though there had been nothing left in the world but the glitter of stars

streaming, ceaseless and vain, through the black stillness of the night.

The white man gazed straight before him into the darkness with wide-open

eyes. The fear and fascination, the inspiration and the wonder of

death–of death near, unavoidable, and unseen, soothed the unrest of his

race and stirred the most indistinct, the most intimate of his thoughts.

The ever-ready suspicion of evil, the gnawing suspicion that lurks in

our hearts, flowed out into the stillness round him–into the stillness

profound and dumb, and made it appear untrustworthy and infamous, like

the placid and impenetrable mask of an unjustifiable violence. In that

fleeting and powerful disturbance of his being the earth enfolded in

the starlight peace became a shadowy country of inhuman strife, a

battle-field of phantoms terrible and charming, august or ignoble,

struggling ardently for the possession of our helpless hearts. An

unquiet and mysterious country of inextinguishable desires and fears.

A plaintive murmur rose in the night; a murmur saddening and startling,

as if the great solitudes of surrounding woods had tried to whisper

into his ear the wisdom of their immense and lofty indifference. Sounds

hesitating and vague floated in the air round him, shaped themselves

slowly into words; and at last flowed on gently in a murmuring stream

of soft and monotonous sentences. He stirred like a man waking up and

changed his position slightly. Arsat, motionless and shadowy, sitting

with bowed head under the stars, was speaking in a low and dreamy tone–

“. . . for where can we lay down the heaviness of our trouble but in

a friend’s heart? A man must speak of war and of love. You, Tuan, know

what war is, and you have seen me in time of danger seek death as other

men seek life! A writing may be lost; a lie may be written; but what the

eye has seen is truth and remains in the mind!”

“I remember,” said the white man, quietly. Arsat went on with mournful

composure–

“Therefore I shall speak to you of love. Speak in the night. Speak

before both night and love are gone–and the eye of day looks upon my

sorrow and my shame; upon my blackened face; upon my burnt-up heart.”

A sigh, short and faint, marked an almost imperceptible pause, and then

his words flowed on, without a stir, without a gesture.

“After the time of trouble and war was over and you went away from my

country in the pursuit of your desires, which we, men of the islands,

cannot understand, I and my brother became again, as we had been

before, the sword-bearers of the Ruler. You know we were men of family,

belonging to a ruling race, and more fit than any to carry on our right

shoulder the emblem of power. And in the time of prosperity Si Dendring

showed us favour, as we, in time of sorrow, had showed to him the

faithfulness of our courage. It was a time of peace. A time of

deer-hunts and cock-fights; of idle talks and foolish squabbles between

men whose bellies are full and weapons are rusty. But the sower watched

the young rice-shoots grow up without fear, and the traders came and

went, departed lean and returned fat into the river of peace. They

brought news, too. Brought lies and truth mixed together, so that no man

knew when to rejoice and when to be sorry. We heard from them about you

also. They had seen you here and had seen you there. And I was glad to

hear, for I remembered the stirring times, and I always remembered you,

Tuan, till the time came when my eyes could see nothing in the past,

because they had looked upon the one who is dying there–in the house.”

He stopped to exclaim in an intense whisper, “O Mara bahia! O Calamity!”

then went on speaking a little louder:

“There’s no worse enemy and no better friend than a brother, Tuan, for

one brother knows another, and in perfect knowledge is strength for good

or evil. I loved my brother. I went to him and told him that I could see

nothing but one face, hear nothing but one voice. He told me: ‘Open your

heart so that she can see what is in it–and wait. Patience is wisdom.

Inchi Midah may die or our Ruler may throw off his fear of a woman!’

. . . I waited! . . . You remember the lady with the veiled face, Tuan, and

the fear of our Ruler before her cunning and temper. And if she wanted

her servant, what could I do? But I fed the hunger of my heart on short

glances and stealthy words. I loitered on the path to the bath-houses in

the daytime, and when the sun had fallen behind the forest I crept along

the jasmine hedges of the women’s courtyard. Unseeing, we spoke to

one another through the scent of flowers, through the veil of leaves,

through the blades of long grass that stood still before our lips; so

great was our prudence, so faint was the murmur of our great longing.

The time passed swiftly . . . and there were whispers amongst women–and

our enemies watched–my brother was gloomy, and I began to think of

killing and of a fierce death. . . . We are of a people who take what

they want–like you whites. There is a time when a man should forget

loyalty and respect. Might and authority are given to rulers, but to all

men is given love and strength and courage. My brother said, ‘You shall

take her from their midst. We are two who are like one.’ And I answered,

‘Let it be soon, for I find no warmth in sunlight that does not shine

upon her.’ Our time came when the Ruler and all the great people went

to the mouth of the river to fish by torchlight. There were hundreds

of boats, and on the white sand, between the water and the forests,

dwellings of leaves were built for the households of the Rajahs. The

smoke of cooking-fires was like a blue mist of the evening, and many

voices rang in it joyfully. While they were making the boats ready to

beat up the fish, my brother came to me and said, ‘To-night!’ I looked

to my weapons, and when the time came our canoe took its place in the

circle of boats carrying the torches. The lights blazed on the water,

but behind the boats there was darkness. When the shouting began and the

excitement made them like mad we dropped out. The water swallowed our

fire, and we floated back to the shore that was dark with only here

and there the glimmer of embers. We could hear the talk of slave-girls

amongst the sheds. Then we found a place deserted and silent. We waited

there. She came. She came running along the shore, rapid and leaving

no trace, like a leaf driven by the wind into the sea. My brother said

gloomily, ‘Go and take her; carry her into our boat.’ I lifted her in

my arms. She panted. Her heart was beating against my breast. I said, ‘I

take you from those people. You came to the cry of my heart, but my arms

take you into my boat against the will of the great!’ ‘It is right,’

said my brother. ‘We are men who take what we want and can hold it

against many. We should have taken her in daylight.’ I said, ‘Let us be

off’; for since she was in my boat I began to think of our Ruler’s many

men. ‘Yes. Let us be off,’ said my brother. ‘We are cast out and this

boat is our country now–and the sea is our refuge.’ He lingered with

his foot on the shore, and I entreated him to hasten, for I remembered

the strokes of her heart against my breast and thought that two men

cannot withstand a hundred. We left, paddling downstream close to the

bank; and as we passed by the creek where they were fishing, the great

shouting had ceased, but the murmur of voices was loud like the humming

of insects flying at noonday. The boats floated, clustered together, in

the red light of torches, under a black roof of smoke; and men talked of

their sport. Men that boasted, and praised, and jeered–men that would

have been our friends in the morning, but on that night were already our

enemies. We paddled swiftly past. We had no more friends in the country

of our birth. She sat in the middle of the canoe with covered face;

silent as she is now; unseeing as she is now–and I had no regret at

what I was leaving because I could hear her breathing close to me–as I

can hear her now.”

He paused, listened with his ear turned to the doorway, then shook his

head and went on:

“My brother wanted to shout the cry of challenge–one cry only–to let

the people know we were freeborn robbers who trusted our arms and the

great sea. And again I begged him in the name of our love to be silent.

Could I not hear her breathing close to me? I knew the pursuit would

come quick enough. My brother loved me. He dipped his paddle without a

splash. He only said, ‘There is half a man in you now–the other half is

in that woman. I can wait. When you are a whole man again, you will come

back with me here to shout defiance. We are sons of the same mother.’ I

made no answer. All my strength and all my spirit were in my hands that

held the paddle–for I longed to be with her in a safe place beyond the

reach of men’s anger and of women’s spite. My love was so great, that

I thought it could guide me to a country where death was unknown, if I

could only escape from Inchi Midah’s fury and from our Ruler’s sword.

We paddled with haste, breathing through our teeth. The blades bit deep

into the smooth water. We passed out of the river; we flew in clear

channels amongst the shallows. We skirted the black coast; we skirted

the sand beaches where the sea speaks in whispers to the land; and the

gleam of white sand flashed back past our boat, so swiftly she ran upon

the water. We spoke not. Only once I said, ‘Sleep, Diamelen, for soon

you may want all your strength.’ I heard the sweetness of her voice, but

I never turned my head. The sun rose and still we went on. Water fell

from my face like rain from a cloud. We flew in the light and heat. I

never looked back, but I knew that my brother’s eyes, behind me, were

looking steadily ahead, for the boat went as straight as a bushman’s

dart, when it leaves the end of the sumpitan. There was no better

paddler, no better steersman than my brother. Many times, together, we

had won races in that canoe. But we never had put out our strength as we

did then–then, when for the last time we paddled together! There was no

braver or stronger man in our country than my brother. I could not spare

the strength to turn my head and look at him, but every moment I heard

the hiss of his breath getting louder behind me. Still he did not speak.

The sun was high. The heat clung to my back like a flame of fire. My

ribs were ready to burst, but I could no longer get enough air into

my chest. And then I felt I must cry out with my last breath, ‘Let us

rest!’ . . . ‘Good!’ he answered; and his voice was firm. He was strong.

He was brave. He knew not fear and no fatigue . . . My brother!”

A murmur powerful and gentle, a murmur vast and faint; the murmur of

trembling leaves, of stirring boughs, ran through the tangled depths of

the forests, ran over the starry smoothness of the lagoon, and the water

between the piles lapped the slimy timber once with a sudden splash.

A breath of warm air touched the two men’s faces and passed on with

a mournful sound–a breath loud and short like an uneasy sigh of the

dreaming earth.

Arsat went on in an even, low voice.

“We ran our canoe on the white beach of a little bay close to a long

tongue of land that seemed to bar our road; a long wooded cape going far

into the sea. My brother knew that place. Beyond the cape a river has

its entrance, and through the jungle of that land there is a narrow

path. We made a fire and cooked rice. Then we lay down to sleep on the

soft sand in the shade of our canoe, while she watched. No sooner had I

closed my eyes than I heard her cry of alarm. We leaped up. The sun was

halfway down the sky already, and coming in sight in the opening of the

bay we saw a prau manned by many paddlers. We knew it at once; it was

one of our Rajah’s praus. They were watching the shore, and saw us. They

beat the gong, and turned the head of the prau into the bay. I felt my

heart become weak within my breast. Diamelen sat on the sand and covered

her face. There was no escape by sea. My brother laughed. He had the

gun you had given him, Tuan, before you went away, but there was only a

handful of powder. He spoke to me quickly: ‘Run with her along the path.

I shall keep them back, for they have no firearms, and landing in the

face of a man with a gun is certain death for some. Run with her. On the

other side of that wood there is a fisherman’s house–and a canoe.

When I have fired all the shots I will follow. I am a great runner, and

before they can come up we shall be gone. I will hold out as long as I

can, for she is but a woman–that can neither run nor fight, but she has

your heart in her weak hands.’ He dropped behind the canoe. The prau was

coming. She and I ran, and as we rushed along the path I heard shots.

My brother fired–once–twice–and the booming of the gong ceased. There

was silence behind us. That neck of land is narrow. Before I heard my

brother fire the third shot I saw the shelving shore, and I saw the

water again; the mouth of a broad river. We crossed a grassy glade. We

ran down to the water. I saw a low hut above the black mud, and a small

canoe hauled up. I heard another shot behind me. I thought, ‘That is his

last charge.’ We rushed down to the canoe; a man came running from the

hut, but I leaped on him, and we rolled together in the mud. Then I got

up, and he lay still at my feet. I don’t know whether I had killed him

or not. I and Diamelen pushed the canoe afloat. I heard yells behind me,

and I saw my brother run across the glade. Many men were bounding after

him, I took her in my arms and threw her into the boat, then leaped in

myself. When I looked back I saw that my brother had fallen. He fell

and was up again, but the men were closing round him. He shouted, ‘I am

coming!’ The men were close to him. I looked. Many men. Then I looked

at her. Tuan, I pushed the canoe! I pushed it into deep water. She was

kneeling forward looking at me, and I said, ‘Take your paddle,’ while

I struck the water with mine. Tuan, I heard him cry. I heard him cry my

name twice; and I heard voices shouting, ‘Kill! Strike!’ I never turned

back. I heard him calling my name again with a great shriek, as when

life is going out together with the voice–and I never turned my head.

My own name! . . . My brother! Three times he called–but I was not

afraid of life. Was she not there in that canoe? And could I not with

her find a country where death is forgotten–where death is unknown!”

The white man sat up. Arsat rose and stood, an indistinct and silent

figure above the dying embers of the fire. Over the lagoon a mist

drifting and low had crept, erasing slowly the glittering images of

the stars. And now a great expanse of white vapour covered the land: it

flowed cold and gray in the darkness, eddied in noiseless whirls round

the tree-trunks and about the platform of the house, which seemed to

float upon a restless and impalpable illusion of a sea. Only far away

the tops of the trees stood outlined on the twinkle of heaven, like a

sombre and forbidding shore–a coast deceptive, pitiless and black.

Arsat’s voice vibrated loudly in the profound peace.

“I had her there! I had her! To get her I would have faced all mankind.

But I had her–and–”

His words went out ringing into the empty distances. He paused, and

seemed to listen to them dying away very far–beyond help and beyond

recall. Then he said quietly–

“Tuan, I loved my brother.”

A breath of wind made him shiver. High above his head, high above the

silent sea of mist the drooping leaves of the palms rattled together

with a mournful and expiring sound. The white man stretched his legs.

His chin rested on his chest, and he murmured sadly without lifting his

head–

“We all love our brothers.”

Arsat burst out with an intense whispering violence–

“What did I care who died? I wanted peace in my own heart.”

He seemed to hear a stir in the house–listened–then stepped in

noiselessly. The white man stood up. A breeze was coming in fitful

puffs. The stars shone paler as if they had retreated into the frozen

depths of immense space. After a chill gust of wind there were a few

seconds of perfect calm and absolute silence. Then from behind the black

and wavy line of the forests a column of golden light shot up into the

heavens and spread over the semicircle of the eastern horizon. The sun

had risen. The mist lifted, broke into drifting patches, vanished into

thin flying wreaths; and the unveiled lagoon lay, polished and black, in

the heavy shadows at the foot of the wall of trees. A white eagle rose

over it with a slanting and ponderous flight, reached the clear sunshine

and appeared dazzlingly brilliant for a moment, then soaring higher,

became a dark and motionless speck before it vanished into the blue as

if it had left the earth forever. The white man, standing gazing upwards

before the doorway, heard in the hut a confused and broken murmur of

distracted words ending with a loud groan. Suddenly Arsat stumbled out

with outstretched hands, shivered, and stood still for some time with

fixed eyes. Then he said–

“She burns no more.”

Before his face the sun showed its edge above the tree-tops rising

steadily. The breeze freshened; a great brilliance burst upon the

lagoon, sparkled on the rippling water. The forests came out of the

clear shadows of the morning, became distinct, as if they had rushed

nearer–to stop short in a great stir of leaves, of nodding boughs, of

swaying branches. In the merciless sunshine the whisper of unconscious

life grew louder, speaking in an incomprehensible voice round the dumb

darkness of that human sorrow. Arsat’s eyes wandered slowly, then stared

at the rising sun.

“I can see nothing,” he said half aloud to himself.

“There is nothing,” said the white man, moving to the edge of the

platform and waving his hand to his boat. A shout came faintly over the

lagoon and the sampan began to glide towards the abode of the friend of

ghosts.

“If you want to come with me, I will wait all the morning,” said the

white man, looking away upon the water.

“No, Tuan,” said Arsat, softly. “I shall not eat or sleep in this house,

but I must first see my road. Now I can see nothing–see nothing! There

is no light and no peace in the world; but there is death–death for

many. We are sons of the same mother–and I left him in the midst of

enemies; but I am going back now.”

He drew a long breath and went on in a dreamy tone:

“In a little while I shall see clear enough to strike–to strike. But

she has died, and . . . now . . . darkness.”

He flung his arms wide open, let them fall along his body, then stood

still with unmoved face and stony eyes, staring at the sun. The white

man got down into his canoe. The polers ran smartly along the sides

of the boat, looking over their shoulders at the beginning of a weary

journey. High in the stern, his head muffled up in white rags, the

juragan sat moody, letting his paddle trail in the water. The white man,

leaning with both arms over the grass roof of the little cabin, looked

back at the shining ripple of the boat’s wake. Before the sampan passed

out of the lagoon into the creek he lifted his eyes. Arsat had not

moved. He stood lonely in the searching sunshine; and he looked beyond

the great light of a cloudless day into the darkness of a world of

illusions.

.jpg)

Joseph Conrad: The Lagoon

fleursdumal.nl magazine

![]()

More in: Archive C-D, Conrad, Joseph, Joseph Conrad

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

VI. La Kermesse de Rubens

Le lendemain soir, j’errais dans les rues d’un petit village situé en Picardie, au bord de la mer. Le vent soufflait avec rage, les vagues croulaient les unes sur les autres, et les moulins à vent découpaient leurs silhouettes grêles sur de monstrueux amas de nuages noirs. çà et là, sur la route, étincelaient de petites chapelles, élevées par les marins à la Vierge protectrice. Je marchais lentement, baisant tes lèvres rudes, aspirant l’âcre et chaude senteur de ta bouche, ô ma vieille maîtresse, ma vieille Gambier! j’écoutais le grincement des meules et le renâclement farouche de la mer, quand soudain retentit à mon oreille un air de danse, et j’aperçus une faible lueur qui rougeoyait à la fenêtre d’une grange. C’était le bal des pêcheurs et des matelotes. Quelle différence avec celui que j’avais vu hier au soir! Au lieu de cette truandaille ramassée dans je ne sais quel ruisseau, j’avais devant les yeux des gars à la figure honnête et douce; au lieu de ces visages dépenaillés et rongés par les onguents, de ces yeux ardoisés et séchés par la débauche, de ces lèvres minces et orlées de carmin, je voyais de bonnes grosses figures rouges, des yeux vifs et gais, des lèvres épaisses et gonflées de sang; je voyais s’épanouir, au lieu de chairs flétries, des chairs énormes, comme les peignait Rubens, des joues roses et dures, comme les aimait Jordaens.

Au fond de la salle, se tenait un vieillard de quatre-vingts ans, tout rapetissé et ratatiné; sa figure était sillonnée de ravines et de sentes qui s’enlaçaient et formaient un capricieux treillis; ses petits yeux noirs, plissés, bridés jusqu’aux tempes, étaient couverts d’une taie blanche comme des boules d’agate marbrées de blanc, et son gros nez saillant étrangement, diapré de bubelettes nacarat, boutonné d’améthystes troubles.

C’était le doyen des pêcheurs, l’oracle du village. Dans le coin, à sa gauche, quatre loups de mer s’étaient attablés. Deux jouaient aux cartes et les deux autres les regardaient jouer. Ils avaient tous le teint hâlé et brun comme le vieux chêne, des chevelures emmêlées et grisonnantes, des mines truculentes et bonnes. Ils vidaient, à petites gorgées, leur tasse de café, et s’essuyaient les lèvres du revers de leur manche. La partie était intéressante, le coup était difficile; celui qui devait jouer tenait son menton dans sa grosse main couleur de cannelle et regardait son jeu avec inquiétude. Il touchait une carte, puis une autre, sans pouvoir se décider a choisir entre elles; son partner l’observait en riant et d’un air vainqueur, et les deux autres tiraient d’épaisses bouffées de leur pipe et se poussaient le coude en clignant de l’oeil. On eut dit un tableau de Teniers, il n’y manquait vraiment que les deux arbres et le château des Trois-Tours.

Pendant ce temps, le cornet et le violon faisaient rage, et de grands gaillards, membrus et souples, les oreilles ornées de petites poires d’or, gambadaient comme des singes et faisaient tournoyer les grosses pêcheuses, qui s’esclaffaient de rire comme des folles. La plupart étaient laides, et pourtant elles étaient charmantes avec leurs petits bonnets blancs, jaspés de fleurs violettes, leur grosse camisole et leurs manches en tricot rouge et jaune. Les enfants et les chiens se mirent bientôt de ]a partie et se roulèrent sur le plancher. Ce n’était plus une danse villageoise de Teniers, c’était la kermesse de Rubens, mais une kermesse pudique, car les mamans tricotaient sur les bancs et surveillaient, du coin de l’oeil, leurs garçons et leurs filles.

Eh bien! je vous jure que cette joie était bonne à voir, je vous jure que la naïve simplesse de ces grosses matelotes m’a ravi et que j’ai détesté plus encore ces bauges de Paris où s’agitent comme cinglés par le fouet de l’hystérie, un ramassis de naïades d’égout et de sinistres riboteurs!

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Professions for Women

A paper read to The Women’s Service League

When your secretary invited me to come here, she told me that your Society is concerned with the employment of women and she suggested that I might tell you something about my own professional experiences. It is true I am a woman; it is true I am employed; but what professional experiences have I had? It is difficult to say. My profession is literature; and in that profession there are fewer experiences for women than in any other, with the exception of the stage—fewer, I mean, that are peculiar to women. For the road was cut many years ago—by Fanny Burney, by Aphra Behn, by Harriet Martineau, by Jane Austen, by George Eliot—many famous women, and many more unknown and forgotten, have been before me, making the path smooth, and regulating my steps. Thus, when I came to write, there were very few material obstacles in my way. Writing was a reputable and harmless occupation. The family peace was not broken by the scratching of a pen. No demand was made upon the family purse. For ten and sixpence one can buy paper enough to write all the plays of Shakespeare—if one has a mind that way. Pianos and models, Paris, Vienna and Berlin, masters and mistresses, are not needed by a writer. The cheapness of writing paper is, of course, the reason why women have succeeded as writers before they have succeeded in the other professions.

But to tell you my story—it is a simple one. You have only got to figure to yourselves a girl in a bedroom with a pen in her hand. She had only to move that pen from left to right—from ten o’clock to one. Then it occurred to her to do what is simple and cheap enough after all—to slip a few of those pages into an envelope, fix a penny stamp in the corner, and drop the envelope into the red box at the corner. It was thus that I became a journalist; and my effort was rewarded on the first day of the following month—a very glorious day it was for me—by a letter from an editor containing a cheque for one pound ten shillings and sixpence. But to show you how little I deserve to be called a professional woman, how little I know of the struggles and difficulties of such lives, I have to admit that instead of spending that sum upon bread and butter, rent, shoes and stockings, or butcher’s bills, I went out and bought a cat—a beautiful cat, a Persian cat, which very soon involved me in bitter disputes with my neighbours.

What could be easier than to write articles and to buy Persian cats with the profits? But wait a moment. Articles have to be about something. Mine, I seem to remember, was about a novel by a famous man. And while I was writing this review, I discovered that if I were going to review books I should need to do battle with a certain phantom. And the phantom was a woman, and when I came to know her better I called her after the heroine of a famous poem, The Angel in the House. It was she who used to come between me and my paper when I was writing reviews. It was she who bothered me and wasted my time and so tormented me that at last I killed her. You who come of a younger and happier generation may not have heard of her—you may not know what I mean by the Angel in the House. I will describe her as shortly as I can. She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught she sat in it—in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others. Above all—I need not say it—–she was pure. Her purity was supposed to be her chief beauty—her blushes, her great grace. In those days—the last of Queen Victoria—every house had its Angel. And when I came to write I encountered her with the very first words. The shadow of her wings fell on my page; I heard the rustling of her skirts in the room. Directly, that is to say, I took my pen in my hand to review that novel by a famous man, she slipped behind me and whispered: “My dear, you are a young woman. You are writing about a book that has been written by a man. Be sympathetic; be tender; flatter; deceive; use all the arts and wiles of our sex. Never let anybody guess that you have a mind of your own. Above all, be pure.” And she made as if to guide my pen. I now record the one act for which I take some credit to myself, though the credit rightly belongs to some excellent ancestors of mine who left me a certain sum of money—shall we say five hundred pounds a year?—so that it was not necessary for me to depend solely on charm for my living. I turned upon her and caught her by the throat. I did my best to kill her. My excuse, if I were to be had up in a court of law, would be that I acted in self–defence. Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing. For, as I found, directly I put pen to paper, you cannot review even a novel without having a mind of your own, without expressing what you think to be the truth about human relations, morality, sex. And all these questions, according to the Angel of the House, cannot be dealt with freely and openly by women; they must charm, they must conciliate, they must—to put it bluntly—tell lies if they are to succeed. Thus, whenever I felt the shadow of her wing or the radiance of her halo upon my page, I took up the inkpot and flung it at her. She died hard. Her fictitious nature was of great assistance to her. It is far harder to kill a phantom than a reality. She was always creeping back when I thought I had despatched her. Though I flatter myself that I killed her in the end, the struggle was severe; it took much time that had better have been spent upon learning Greek grammar; or in roaming the world in search of adventures. But it was a real experience; it was an experience that was bound to befall all women writers at that time. Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer.

But to continue my story. The Angel was dead; what then remained? You may say that what remained was a simple and common object—a young woman in a bedroom with an inkpot. In other words, now that she had rid herself of falsehood, that young woman had only to be herself. Ah, but what is “herself”? I mean, what is a woman? I assure you, I do not know. I do not believe that you know. I do not believe that anybody can know until she has expressed herself in all the arts and professions open to human skill. That indeed is one of the reasons why I have come here out of respect for you, who are in process of showing us by your experiments what a woman is, who are in process Of providing us, by your failures and successes, with that extremely important piece of information.

But to continue the story of my professional experiences. I made one pound ten and six by my first review; and I bought a Persian cat with the proceeds. Then I grew ambitious. A Persian cat is all very well, I said; but a Persian cat is not enough. I must have a motor car. And it was thus that I became a novelist—for it is a very strange thing that people will give you a motor car if you will tell them a story. It is a still stranger thing that there is nothing so delightful in the world as telling stories. It is far pleasanter than writing reviews of famous novels. And yet, if I am to obey your secretary and tell you my professional experiences as a novelist, I must tell you about a very strange experience that befell me as a novelist. And to understand it you must try first to imagine a novelist’s state of mind. I hope I am not giving away professional secrets if I say that a novelist’s chief desire is to be as unconscious as possible. He has to induce in himself a state of perpetual lethargy. He wants life to proceed with the utmost quiet and regularity. He wants to see the same faces, to read the same books, to do the same things day after day, month after month, while he is writing, so that nothing may break the illusion in which he is living—so that nothing may disturb or disquiet the mysterious nosings about, feelings round, darts, dashes and sudden discoveries of that very shy and illusive spirit, the imagination. I suspect that this state is the same both for men and women. Be that as it may, I want you to imagine me writing a novel in a state of trance. I want you to figure to yourselves a girl sitting with a pen in her hand, which for minutes, and indeed for hours, she never dips into the inkpot. The image that comes to my mind when I think of this girl is the image of a fisherman lying sunk in dreams on the verge of a deep lake with a rod held out over the water. She was letting her imagination sweep unchecked round every rock and cranny of the world that lies submerged in the depths of our unconscious being. Now came the experience, the experience that I believe to be far commoner with women writers than with men. The line raced through the girl’s fingers. Her imagination had rushed away. It had sought the pools, the depths, the dark places where the largest fish slumber. And then there was a smash. There was an explosion. There was foam and confusion. The imagination had dashed itself against something hard. The girl was roused from her dream. She was indeed in a state of the most acute and difficult distress. To speak without figure she had thought of something, something about the body, about the passions which it was unfitting for her as a woman to say. Men, her reason told her, would be shocked. The consciousness of—what men will say of a woman who speaks the truth about her passions had roused her from her artist’s state of unconsciousness. She could write no more. The trance was over. Her imagination could work no longer. This I believe to be a very common experience with women writers—they are impeded by the extreme conventionality of the other sex. For though men sensibly allow themselves great freedom in these respects, I doubt that they realize or can control the extreme severity with which they condemn such freedom in women.

These then were two very genuine experiences of my own. These were two of the adventures of my professional life. The first—killing the Angel in the House—I think I solved. She died. But the second, telling the truth about my own experiences as a body, I do not think I solved. I doubt that any woman has solved it yet. The obstacles against her are still immensely powerful—and yet they are very difficult to define. Outwardly, what is simpler than to write books? Outwardly, what obstacles are there for a woman rather than for a man? Inwardly, I think, the case is very different; she has still many ghosts to fight, many prejudices to overcome. Indeed it will be a long time still, I think, before a woman can sit down to write a book without finding a phantom to be slain, a rock to be dashed against. And if this is so in literature, the freest of all professions for women, how is it in the new professions which you are now for the first time entering?

Those are the questions that I should like, had I time, to ask you. And indeed, if I have laid stress upon these professional experiences of mine, it is because I believe that they are, though in different forms, yours also. Even when the path is nominally open—when there is nothing to prevent a woman from being a doctor, a lawyer, a civil servant—there are many phantoms and obstacles, as I believe, looming in her way. To discuss and define them is I think of great value and importance; for thus only can the labour be shared, the difficulties be solved. But besides this, it is necessary also to discuss the ends and the aims for which we are fighting, for which we are doing battle with these formidable obstacles. Those aims cannot be taken for granted; they must be perpetually questioned and examined. The whole position, as I see it—here in this hall surrounded by women practising for the first time in history I know not how many different professions—is one of extraordinary interest and importance. You have won rooms of your own in the house hitherto exclusively owned by men. You are able, though not without great labour and effort, to pay the rent. You are earning your five hundred pounds a year. But this freedom is only a beginning—the room is your own, but it is still bare. It has to be furnished; it has to be decorated; it has to be shared. How are you going to furnish it, how are you going to decorate it? With whom are you going to share it, and upon what terms? These, I think are questions of the utmost importance and interest. For the first time in history you are able to ask them; for the first time you are able to decide for yourselves what the answers should be. Willingly would I stay and discuss those questions and answers—but not to–night. My time is up; and I must cease.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Death of the Moth, and other essays

kempis poetry magazine

![]()

More in: Woolf, Virginia

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

To the Memory of Mrs. Lefroy

who died Dec’r 16 — my Birthday

The day returns again, my natal day;

What mix’d emotions with the Thought arise!

Beloved friend, four years have pass’d away

Since thou wert snatch’d forever from our eyes.–

The day, commemorative of my birth

Bestowing Life and Light and Hope on me,

Brings back the hour which was thy last on Earth.

Oh! bitter pang of torturing Memory!–

Angelic Woman! past my power to praise

In Language meet, thy Talents, Temper, mind.

Thy solid Worth, they captivating Grace!–

Thou friend and ornament of Humankind!–

At Johnson’s death by Hamilton t’was said,

‘Seek we a substitute–Ah! vain the plan,

No second best remains to Johnson dead–

None can remind us even of the Man.’

So we of thee–unequall’d in thy race

Unequall’d thou, as he the first of Men.

Vainly we wearch around the vacant place,

We ne’er may look upon thy like again.

Come then fond Fancy, thou indulgant Power,–

–Hope is desponding, chill, severe to thee!–

Bless thou, this little portion of an hour,

Let me behold her as she used to be.

I see her here, with all her smiles benign,

Her looks of eager Love, her accents sweet.

That voice and Countenance almost divine!–

Expression, Harmony, alike complete.–

I listen–’tis not sound alone–’tis sense,

‘Tis Genius, Taste and Tenderness of Soul.

‘Tis genuine warmth of heart without pretence

And purity of Mind that crowns the whole.

She speaks; ’tis Eloquence–that grace of Tongue

So rare, so lovely!–Never misapplied

By her to palliate Vice, or deck a Wrong,

She speaks and reasons but on Virtue’s side.

Her’s is the Engergy of Soul sincere.

Her Christian Spirit ignorant to feign,

Seeks but to comfort, heal, enlighten, chear,

Confer a pleasure, or prevent a pain.–

Can ought enhance such Goodness?–Yes, to me,

Her partial favour from my earliest years

Consummates all.–Ah! Give me yet to see

Her smile of Love.–the Vision diappears.

‘Tis past and gone–We meet no more below.

Short is the Cheat of Fancy o’er the Tomb.

Oh! might I hope to equal Bliss to go!

To meet thee Angel! in thy future home!–

Fain would I feel an union in thy fate,

Fain would I seek to draw an Omen fair

From this connection in our Earthly date.

Indulge the harmless weakness–Reason, spare.–

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

Joseph Conrad

(1857-1924)

A Desperate Tale

An Anarchist

That year I spent the best two months of the dry season on one of

the estates–in fact, on the principal cattle estate–of a famous

meat-extract manufacturing company.

B.O.S. Bos. You have seen the three magic letters on the advertisement

pages of magazines and newspapers, in the windows of provision

merchants, and on calendars for next year you receive by post in the

month of November. They scatter pamphlets also, written in a sickly

enthusiastic style and in several languages, giving statistics of

slaughter and bloodshed enough to make a Turk turn faint. The “art”

illustrating that “literature” represents in vivid and shining colours

a large and enraged black bull stamping upon a yellow snake writhing

in emerald-green grass, with a cobalt-blue sky for a background. It

is atrocious and it is an allegory. The snake symbolizes disease,

weakness–perhaps mere hunger, which last is the chronic disease of the

majority of mankind. Of course everybody knows the B. O. S. Ltd., with

its unrivalled products: Vinobos, Jellybos, and the latest unequalled

perfection, Tribos, whose nourishment is offered to you not only highly

concentrated, but already half digested. Such apparently is the love

that Limited Company bears to its fellowmen–even as the love of the

father and mother penguin for their hungry fledglings.

Of course the capital of a country must be productively employed. I