Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Curse of Eve

The Curse of Eve

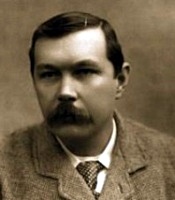

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Robert Johnson was an essentially commonplace man, with no feature to distinguish him from a million others. He was pale of face, ordinary in looks, neutral in opinions, thirty years of age, and a married man. By trade he was a gentleman’s outfitter in the New North Road, and the competition of business squeezed out of him the little character that was left. In his hope of conciliating customers he had become cringing and pliable, until working ever in the same routine from day to day he seemed to have sunk into a soulless machine rather than a man. No great question had ever stirred him. At the end of this snug century, self-contained in his own narrow circle, it seemed impossible that any of the mighty, primitive passions of mankind could ever reach him. Yet birth, and lust, and illness, and death are changeless things, and when one of these harsh facts springs out upon a man at some sudden turn of the path of life, it dashes off for the moment his mask of civilisation and gives a glimpse of the stranger and stronger face below.

Johnson’s wife was a quiet little woman, with brown hair and gentle ways. His affection for her was the one positive trait in his character. Together they would lay out the shop window every Monday morning, the spotless shirts in their green cardboard boxes below, the neckties above hung in rows over the brass rails, the cheap studs glistening from the white cards at either side, while in the background were the rows of cloth caps and the bank of boxes in which the more valuable hats were screened from the sunlight. She kept the books and sent out the bills. No one but she knew the joys and sorrows which crept into his small life. She had shared his exultations when the gentleman who was going to India had bought ten dozen shirts and an incredible number of collars, and she had been as stricken as he when, after the goods had gone, the bill was returned from the hotel address with the intimation that no such person had lodged there. For five years they had worked, building up the business, thrown together all the more closely because their marriage had been a childless one. Now, however, there were signs that a change was at hand, and that speedily. She was unable to come downstairs, and her mother, Mrs. Peyton, came over from Camberwell to nurse her and to welcome her grandchild.

Little qualms of anxiety came over Johnson as his wife’s time approached. However, after all, it was a natural process. Other men’s wives went through it unharmed, and why should not his? He was himself one of a family of fourteen, and yet his mother was alive and hearty. It was quite the exception for anything to go wrong. And yet in spite of his reasonings the remembrance of his wife’s condition was always like a sombre background to all his other thoughts.

Dr. Miles of Bridport Place, the best man in the neighbourhood, was retained five months in advance, and, as time stole on, many little packets of absurdly small white garments with frill work and ribbons began to arrive among the big consignments of male necessities. And then one evening, as Johnson was ticketing the scarfs in the shop, he heard a bustle upstairs, and Mrs. Peyton came running down to say that Lucy was bad and that she thought the doctor ought to be there without delay.

It was not Robert Johnson’s nature to hurry. He was prim and staid and liked to do things in an orderly fashion. It was a quarter of a mile from the corner of the New North Road where his shop stood to the doctor’s house in Bridport Place. There were no cabs in sight so he set off upon foot, leaving the lad to mind the shop. At Bridport Place he was told that the doctor had just gone to Harman Street to attend a man in a fit. Johnson started off for Harman Street, losing a little of his primness as he became more anxious. Two full cabs but no empty ones passed him on the way. At Harman Street he learned that the doctor had gone on to a case of measles, fortunately he had left the address—69 Dunstan Road, at the other side of the Regent’s Canal. Robert’s primness had vanished now as he thought of the women waiting at home, and he began to run as hard as he could down the Kingsland Road. Some way along he sprang into a cab which stood by the curb and drove to Dunstan Road. The doctor had just left, and Robert Johnson felt inclined to sit down upon the steps in despair.

Fortunately he had not sent the cab away, and he was soon back at Bridport Place. Dr. Miles had not returned yet, but they were expecting him every instant. Johnson waited, drumming his fingers on his knees, in a high, dim lit room, the air of which was charged with a faint, sickly smell of ether. The furniture was massive, and the books in the shelves were sombre, and a squat black clock ticked mournfully on the mantelpiece. It told him that it was half-past seven, and that he had been gone an hour and a quarter. Whatever would the women think of him! Every time that a distant door slammed he sprang from his chair in a quiver of eagerness. His ears strained to catch the deep notes of the doctor’s voice. And then, suddenly, with a gush of joy he heard a quick step outside, and the sharp click of the key in the lock. In an instant he was out in the hall, before the doctor’s foot was over the threshold.

“If you please, doctor, I’ve come for you,” he cried; “the wife was taken bad at six o’clock.”

He hardly knew what he expected the doctor to do. Something very energetic, certainly—to seize some drugs, perhaps, and rush excitedly with him through the gaslit streets. Instead of that Dr. Miles threw his umbrella into the rack, jerked off his hat with a somewhat peevish gesture, and pushed Johnson back into the room.

“Let’s see! You DID engage me, didn’t you?” he asked in no very cordial voice.

“Oh, yes, doctor, last November. Johnson the outfitter, you know, in the New North Road.”

“Yes, yes. It’s a bit overdue,” said the doctor, glancing at a list of names in a note-book with a very shiny cover. “Well, how is she?”

“I don’t——”

“Ah, of course, it’s your first. You’ll know more about it next time.”

“Mrs. Peyton said it was time you were there, sir.”

“My dear sir, there can be no very pressing hurry in a first case. We shall have an all-night affair, I fancy. You can’t get an engine to go without coals, Mr. Johnson, and I have had nothing but a light lunch.”

“We could have something cooked for you—something hot and a cup of tea.”

“Thank you, but I fancy my dinner is actually on the table. I can do no good in the earlier stages. Go home and say that I am coming, and I will be round immediately afterwards.”

A sort of horror filled Robert Johnson as he gazed at this man who could think about his dinner at such a moment. He had not imagination enough to realise that the experience which seemed so appallingly important to him, was the merest everyday matter of business to the medical man who could not have lived for a year had he not, amid the rush of work, remembered what was due to his own health. To Johnson he seemed little better than a monster. His thoughts were bitter as he sped back to his shop.

“You’ve taken your time,” said his mother-in-law reproachfully, looking down the stairs as he entered.

“I couldn’t help it!” he gasped. “Is it over?”

“Over! She’s got to be worse, poor dear, before she can be better. Where’s Dr. Miles!”

“He’s coming after he’s had dinner.” The old woman was about to make some reply, when, from the half-opened door behind a high whinnying voice cried out for her. She ran back and closed the door, while Johnson, sick at heart, turned into the shop. There he sent the lad home and busied himself frantically in putting up shutters and turning out boxes. When all was closed and finished he seated himself in the parlour behind the shop. But he could not sit still. He rose incessantly to walk a few paces and then fell back into a chair once more. Suddenly the clatter of china fell upon his ear, and he saw the maid pass the door with a cup on a tray and a smoking teapot.

“Who is that for, Jane?” he asked.

“For the mistress, Mr. Johnson. She says she would fancy it.”

There was immeasurable consolation to him in that homely cup of tea. It wasn’t so very bad after all if his wife could think of such things. So light-hearted was he that he asked for a cup also. He had just finished it when the doctor arrived, with a small black leather bag in his hand.

“Well, how is she?” he asked genially.

“Oh, she’s very much better,” said Johnson, with enthusiasm.

“Dear me, that’s bad!” said the doctor. “Perhaps it will do if I look in on my morning round?”

“No, no,” cried Johnson, clutching at his thick frieze overcoat. “We are so glad that you have come. And, doctor, please come down soon and let me know what you think about it.”

The doctor passed upstairs, his firm, heavy steps resounding through the house. Johnson could hear his boots creaking as he walked about the floor above him, and the sound was a consolation to him. It was crisp and decided, the tread of a man who had plenty of self-confidence. Presently, still straining his ears to catch what was going on, he heard the scraping of a chair as it was drawn along the floor, and a moment later he heard the door fly open and someone come rushing downstairs. Johnson sprang up with his hair bristling, thinking that some dreadful thing had occurred, but it was only his mother-in-law, incoherent with excitement and searching for scissors and some tape. She vanished again and Jane passed up the stairs with a pile of newly aired linen. Then, after an interval of silence, Johnson heard the heavy, creaking tread and the doctor came down into the parlour.

“That’s better,” said he, pausing with his hand upon the door. “You look pale, Mr. Johnson.”

“Oh no, sir, not at all,” he answered deprecatingly, mopping his brow with his handkerchief.

“There is no immediate cause for alarm,” said Dr. Miles. “The case is not all that we could wish it. Still we will hope for the best.”

“Is there danger, sir?” gasped Johnson.

“Well, there is always danger, of course. It is not altogether a favourable case, but still it might be much worse. I have given her a draught. I saw as I passed that they have been doing a little building opposite to you. It’s an improving quarter. The rents go higher and higher. You have a lease of your own little place, eh?”

“Yes, sir, yes!” cried Johnson, whose ears were straining for every sound from above, and who felt none the less that it was very soothing that the doctor should be able to chat so easily at such a time. “That’s to say no, sir, I am a yearly tenant.”

“Ah, I should get a lease if I were you. There’s Marshall, the watchmaker, down the street. I attended his wife twice and saw him through the typhoid when they took up the drains in Prince Street. I assure you his landlord sprung his rent nearly forty a year and he had to pay or clear out.”

“Did his wife get through it, doctor?”

“Oh yes, she did very well. Hullo! hullo!”

He slanted his ear to the ceiling with a questioning face, and then darted swiftly from the room.

It was March and the evenings were chill, so Jane had lit the fire, but the wind drove the smoke downwards and the air was full of its acrid taint. Johnson felt chilled to the bone, though rather by his apprehensions than by the weather. He crouched over the fire with his thin white hands held out to the blaze. At ten o’clock Jane brought in the joint of cold meat and laid his place for supper, but he could not bring himself to touch it. He drank a glass of the beer, however, and felt the better for it. The tension of his nerves seemed to have reacted upon his hearing, and he was able to follow the most trivial things in the room above. Once, when the beer was still heartening him, he nerved himself to creep on tiptoe up the stair and to listen to what was going on. The bedroom door was half an inch open, and through the slit he could catch a glimpse of the clean-shaven face of the doctor, looking wearier and more anxious than before. Then he rushed downstairs like a lunatic, and running to the door he tried to distract his thoughts by watching what; was going on in the street. The shops were all shut, and some rollicking boon companions came shouting along from the public-house. He stayed at the door until the stragglers had thinned down, and then came back to his seat by the fire. In his dim brain he was asking himself questions which had never intruded themselves before. Where was the justice of it? What had his sweet, innocent little wife done that she should be used so? Why was nature so cruel? He was frightened at his own thoughts, and yet wondered that they had never occurred to him before.

As the early morning drew in, Johnson, sick at heart and shivering in every limb, sat with his great coat huddled round him, staring at the grey ashes and waiting hopelessly for some relief. His face was white and clammy, and his nerves had been numbed into a half conscious state by the long monotony of misery. But suddenly all his feelings leapt into keen life again as he heard the bedroom door open and the doctor’s steps upon the stair. Robert Johnson was precise and unemotional in everyday life, but he almost shrieked now as he rushed forward to know if it were over.

One glance at the stern, drawn face which met him showed that it was no pleasant news which had sent the doctor downstairs. His appearance had altered as much as Johnson’s during the last few hours. His hair was on end, his face flushed, his forehead dotted with beads of perspiration. There was a peculiar fierceness in his eye, and about the lines of his mouth, a fighting look as befitted a man who for hours on end had been striving with the hungriest of foes for the most precious of prizes. But there was a sadness too, as though his grim opponent had been overmastering him. He sat down and leaned his head upon his hand like a man who is fagged out.

“I thought it my duty to see you, Mr. Johnson, and to tell you that it is a very nasty case. Your wife’s heart is not strong, and she has some symptoms which I do not like. What I wanted to say is that if you would like to have a second opinion I shall be very glad to meet anyone whom you might suggest.”

Johnson was so dazed by his want of sleep and the evil news that he could hardly grasp the doctor’s meaning. The other, seeing him hesitate, thought that he was considering the expense.

“Smith or Hawley would come for two guineas,” said he. “But I think Pritchard of the City Road is the best man.”

“Oh, yes, bring the best man,” cried Johnson.

“Pritchard would want three guineas. He is a senior man, you see.”

“I’d give him all I have if he would pull her through. Shall I run for him?”

“Yes. Go to my house first and ask for the green baize bag. The assistant will give it to you. Tell him I want the A. C. E. mixture. Her heart is too weak for chloroform. Then go for Pritchard and bring him back with you.”

It was heavenly for Johnson to have something to do and to feel that he was of some use to his wife. He ran swiftly to Bridport Place, his footfalls clattering through the silent streets and the big dark policemen turning their yellow funnels of light on him as he passed. Two tugs at the night-bell brought down a sleepy, half-clad assistant, who handed him a stoppered glass bottle and a cloth bag which contained something which clinked when you moved it. Johnson thrust the bottle into his pocket, seized the green bag, and pressing his hat firmly down ran as hard as he could set foot to ground until he was in the City Road and saw the name of Pritchard engraved in white upon a red ground. He bounded in triumph up the three steps which led to the door, and as he did so there was a crash behind him. His precious bottle was in fragments upon the pavement.

For a moment he felt as if it were his wife’s body that was lying there. But the run had freshened his wits and he saw that the mischief might be repaired. He pulled vigorously at the night-bell.

“Well, what’s the matter?” asked a gruff voice at his elbow. He started back and looked up at the windows, but there was no sign of life. He was approaching the bell again with the intention of pulling it, when a perfect roar burst from the wall.

“I can’t stand shivering here all night,” cried the voice. “Say who you are and what you want or I shut the tube.”

Then for the first time Johnson saw that the end of a speaking-tube hung out of the wall just above the bell. He shouted up it,—

“I want you to come with me to meet Dr. Miles at a confinement at once.”

“How far?” shrieked the irascible voice.

“The New North Road, Hoxton.”

“My consultation fee is three guineas, payable at the time.”

“All right,” shouted Johnson. “You are to bring a bottle of A. C. E. mixture with you.”

“All right! Wait a bit!”

Five minutes later an elderly, hard-faced man, with grizzled hair, flung open the door. As he emerged a voice from somewhere in the shadows cried,—

“Mind you take your cravat, John,” and he impatiently growled something over his shoulder in reply.

The consultant was a man who had been hardened by a life of ceaseless labour, and who had been driven, as so many others have been, by the needs of his own increasing family to set the commercial before the philanthropic side of his profession. Yet beneath his rough crust he was a man with a kindly heart.

“We don’t want to break a record,” said he, pulling up and panting after attempting to keep up with Johnson for five minutes. “I would go quicker if I could, my dear sir, and I quite sympathise with your anxiety, but really I can’t manage it.”

So Johnson, on fire with impatience, had to slow down until they reached the New North Road, when he ran ahead and had the door open for the doctor when he came. He heard the two meet outside the bed-room, and caught scraps of their conversation. “Sorry to knock you up—nasty case—decent people.” Then it sank into a mumble and the door closed behind them.

Johnson sat up in his chair now, listening keenly, for he knew that a crisis must be at hand. He heard the two doctors moving about, and was able to distinguish the step of Pritchard, which had a drag in it, from the clean, crisp sound of the other’s footfall. There was silence for a few minutes and then a curious drunken, mumbling sing-song voice came quavering up, very unlike anything which he had heard hitherto. At the same time a sweetish, insidious scent, imperceptible perhaps to any nerves less strained than his, crept down the stairs and penetrated into the room. The voice dwindled into a mere drone and finally sank away into silence, and Johnson gave a long sigh of relief, for he knew that the drug had done its work and that, come what might, there should be no more pain for the sufferer.

Johnson sat up in his chair now, listening keenly, for he knew that a crisis must be at hand. He heard the two doctors moving about, and was able to distinguish the step of Pritchard, which had a drag in it, from the clean, crisp sound of the other’s footfall. There was silence for a few minutes and then a curious drunken, mumbling sing-song voice came quavering up, very unlike anything which he had heard hitherto. At the same time a sweetish, insidious scent, imperceptible perhaps to any nerves less strained than his, crept down the stairs and penetrated into the room. The voice dwindled into a mere drone and finally sank away into silence, and Johnson gave a long sigh of relief, for he knew that the drug had done its work and that, come what might, there should be no more pain for the sufferer.

But soon the silence became even more trying to him than the cries had been. He had no clue now as to what was going on, and his mind swarmed with horrible possibilities. He rose and went to the bottom of the stairs again. He heard the clink of metal against metal, and the subdued murmur of the doctors’ voices. Then he heard Mrs. Peyton say something, in a tone as of fear or expostulation, and again the doctors murmured together. For twenty minutes he stood there leaning against the wall, listening to the occasional rumbles of talk without being able to catch a word of it. And then of a sudden there rose out of the silence the strangest little piping cry, and Mrs. Peyton screamed out in her delight and the man ran into the parlour and flung himself down upon the horse-hair sofa, drumming his heels on it in his ecstasy.

But often the great cat Fate lets us go only to clutch us again in a fiercer grip. As minute after minute passed and still no sound came from above save those thin, glutinous cries, Johnson cooled from his frenzy of joy, and lay breathless with his ears straining. They were moving slowly about. They were talking in subdued tones. Still minute after minute passing, and no word from the voice for which he listened. His nerves were dulled by his night of trouble, and he waited in limp wretchedness upon his sofa. There he still sat when the doctors came down to him—a bedraggled, miserable figure with his face grimy and his hair unkempt from his long vigil. He rose as they entered, bracing himself against the mantelpiece.

“Is she dead?” he asked.

“Doing well,” answered the doctor.

And at the words that little conventional spirit which had never known until that night the capacity for fierce agony which lay within it, learned for the second time that there were springs of joy also which it had never tapped before. His impulse was to fall upon his knees, but he was shy before the doctors.

“Can I go up?”

“In a few minutes.”

“I’m sure, doctor, I’m very—I’m very——” he grew inarticulate. “Here are your three guineas, Dr. Pritchard. I wish they were three hundred.”

“So do I,” said the senior man, and they laughed as they shook hands.

Johnson opened the shop door for them and heard their talk as they stood for an instant outside.

“Looked nasty at one time.”

“Very glad to have your help.”

“Delighted, I’m sure. Won’t you step round and have a cup of coffee?”

“No, thanks. I’m expecting another case.”

The firm step and the dragging one passed away to the right and the left. Johnson turned from the door still with that turmoil of joy in his heart. He seemed to be making a new start in life. He felt that he was a stronger and a deeper man. Perhaps all this suffering had an object then. It might prove to be a blessing both to his wife and to him. The very thought was one which he would have been incapable of conceiving twelve hours before. He was full of new emotions. If there had been a harrowing there had been a planting too.

“Can I come up?” he cried, and then, without waiting for an answer, he took the steps three at a time.

Mrs. Peyton was standing by a soapy bath with a bundle in her hands. From under the curve of a brown shawl there looked out at him the strangest little red face with crumpled features, moist, loose lips, and eyelids which quivered like a rabbit’s nostrils. The weak neck had let the head topple over, and it rested upon the shoulder.

“Kiss it, Robert!” cried the grandmother. “Kiss your son!”

But he felt a resentment to the little, red, blinking creature. He could not forgive it yet for that long night of misery. He caught sight of a white face in the bed and he ran towards it with such love and pity as his speech could find no words for.

“Thank God it is over! Lucy, dear, it was dreadful!”

“But I’m so happy now. I never was so happy in my life.”

Her eyes were fixed upon the brown bundle.

“You mustn’t talk,” said Mrs. Peyton.

“But don’t leave me,” whispered his wife.

So he sat in silence with his hand in hers. The lamp was burning dim and the first cold light of dawn was breaking through the window. The night had been long and dark but the day was the sweeter and the purer in consequence. London was waking up. The roar began to rise from the street. Lives had come and lives had gone, but the great machine was still working out its dim and tragic destiny.

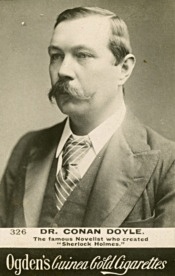

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Curse of Eve (#06)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

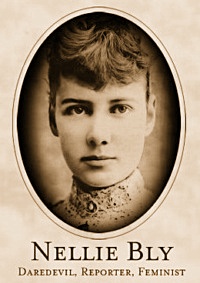

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter IV: Judge Duffy and the Police)

by Nellie Bly

But to return to my story. I kept up my role until the assistant matron, Mrs. Stanard, came in. She tried to persuade me to be calm. I began to see clearly that she wanted to get me out of the house at all hazards, quietly if possible. This I did not want. I refused to move, but kept up ever the refrain of my lost trunks. Finally some one suggested that an officer be sent for. After awhile Mrs. Stanard put on her bonnet and went out. Then I knew that I was making an advance toward the home of the insane. Soon she returned, bringing with her two policemen–big, strong men–who entered the room rather unceremoniously, evidently expecting to meet with a person violently crazy. The name of one of them was Tom Bockert.

When they entered I pretended not to see them. “I want you to take her quietly,” said Mrs. Stanard. “If she don’t come along quietly,” responded one of the men, “I will drag her through the streets.” I still took no notice of them, but certainly wished to avoid raising a scandal outside. Fortunately Mrs. Caine came to my rescue. She told the officers about my outcries for my lost trunks, and together they made up a plan to get me to go along with them quietly by telling me they would go with me to look for my lost effects. They asked me if I would go. I said I was afraid to go alone. Mrs. Stanard then said she would accompany me, and she arranged that the two policemen should follow us at a respectful

distance. She tied on my veil for me, and we left the house by the basement and started across town, the two officers following at some distance behind. We walked along very quietly and finally came to the station house, which the good woman assured me was the express office, and that there we should certainly find my missing effects. I went inside with fear and trembling, for good reason.

A few days previous to this I had met Captain McCullagh at a meeting held in Cooper Union. At that time I had asked him for some information which he had given me. If he were in, would he not recognize me? And then all would be lost so far as getting to the island was concerned. I pulled my sailor hat as low down over my face as I possibly could, and prepared for the ordeal. Sure enough there was sturdy Captain McCullagh standing near the desk.

He watched me closely as the officer at the desk conversed in a low tone with Mrs. Stanard and the policeman who brought me.

“Are you Nellie Brown?” asked the officer. I said I supposed I was. “Where do you come from?” he asked. I told him I did not know, and then Mrs. Stanard gave him a lot of information about me–told him how strangely I had acted at her home; how I had not slept a wink all night, and that in her opinion I was a poor unfortunate who had been driven crazy by inhuman treatment. There was some discussion between Mrs. Standard and the two officers, and Tom Bockert was told to take us down to the court in a car.

In the hands of the police.

“Come along,” Bockert said, “I will find your trunk for you.” We all went together, Mrs. Stanard, Tom Bockert, and myself. I said it was very kind of them to go with me, and I should not soon forget them. As we walked along I kept up my refrain about my trucks, injecting occasionally some remark about the dirty condition of the streets and the curious character of the people we met on the way. “I don’t think I have ever seen such people before,” I said. “Who are they?” I asked, and my companions looked upon me with expressions of pity, evidently believing I was a foreigner, an emigrant or something of the sort. They told me that the people around me were working people. I remarked once more that I thought there were too many working people in the world for the amount of work to be done, at which remark Policeman P. T. Bockert eyed me closely, evidently thinking that my mind was gone for good. We passed several other policemen, who generally asked my sturdy guardians what was the matter with me. By this time quite a number of ragged children were following us too, and they passed remarks about me that were to me original as well as amusing.

“What’s she up for?” “Say, kop, where did ye get her?” “Where did yer pull ‘er?”

“She’s a daisy!”

Poor Mrs. Stanard was more frightened than I was. The whole situation grew interesting, but I still had fears for my fate before the judge.

At last we came to a low building, and Tom Bockert kindly volunteered the information: “Here’s the express office. We shall soon find those trunks of yours.”

The entrance to the building was surrounded by a curious crowd and I did not think my case was bad enough to permit me passing them without some remark, so I asked if all those people had lost their trunks.

“Yes,” he said, “nearly all these people are looking for trunks.”

I said, “They all seem to be foreigners, too.” “Yes,” said Tom, “they are all foreigners just landed. They have all lost their trunks, and it takes most of our time to help find them for them.”

We entered the courtroom. It was the Essex Market Police Courtroom. At last the question of my sanity or insanity was to be decided. Judge Duffy sat behind the high desk, wearing a look which seemed to indicate that he was dealing out the milk of human kindness by wholesale. I rather feared I would not get the fate I sought, because of the kindness I saw on every line of his face, and it was with rather a sinking heart that I followed Mrs. Stanard as she answered the summons to go up to the desk, where Tom Bockert had just given an account of the affair.

“Come here,” said an officer. “What is your name?”

“Nellie Brown,” I replied, with a little accent. “I have lost my trunks, and would like if you could find them.”

“When did you come to New York?” he asked.

“I did not come to New York,” I replied (while I added, mentally, “because I have been here for some time.”)

“But you are in New York now,” said the man.

“No,” I said, looking as incredulous as I thought a crazy person could, “I did not come to New York.”

“That girl is from the west,” he said, in a tone that made me tremble. “She has a western accent.”

Some one else who had been listening to the brief dialogue here asserted that he had lived south and that my accent was southern, while another officer was positive it was eastern. I felt much relieved when the first spokesman turned to the judge and said:

“Judge, here is a peculiar case of a young woman who doesn’t know who she is or where she came from. You had better attend to it at once.”

I commenced to shake with more than the cold, and I looked around at the strange crowd about me, composed of poorly dressed men and women with stories printed on their faces of hard lives, abuse and poverty. Some were consulting eagerly with friends, while others sat still with a look of utter hopelessness. Everywhere was a sprinkling of well-dressed, well-fed officers watching the scene passively and almost indifferently. It was only an old story with them. One more unfortunate added to a long list which had long since ceased to be of any interest or concern to them.

Nellie before Judge Duffy.

“Come here, girl, and lift your veil,” called out Judge Duffy, in tones which surprised me by a harshness which I did not think from the kindly face he possessed.

“Who are you speaking to?” I inquired, in my stateliest manner.

“Come here, my dear, and lift your veil. You know the Queen of England, if she were here, would have to lift her veil,” he said, very kindly.

“That is much better,” I replied. “I am not the Queen of England, but I’ll lift my veil.”

As I did so the little judge looked at me, and then, in a very kind and gentle tone, he said:

“My dear child, what is wrong?”

“Nothing is wrong except that I have lost my trunks, and this man,” indicating Policeman Bockert, “promised to bring me where they could be found.”

“What do you know about this child?” asked the judge, sternly, of Mrs. Stanard, who stood, pale and trembling, by my side.

“I know nothing of her except that she came to the home yesterday and asked to remain overnight.”

“The home! What do you mean by the home?” asked Judge Duffy, quickly.

“It is a temporary home kept for working women at No. 84 Second Avenue.”

“What is your position there?”

“I am assistant matron.”

“Well, tell us all you know of the case.”

“When I was going into the home yesterday I noticed her coming down the avenue. She was all alone. I had just got into the house when the bell rang and she came in. When I talked with her she wanted to know if she could stay all night, and I said she could. After awhile she said all the people in the house looked crazy, and she was afraid of them. Then she would not go to bed, but sat up all the night.”

“Had she any money?”

“Yes,” I replied, answering for her, “I paid her for everything, and the eating was the worst I ever tried.”

There was a general smile at this, and some murmurs of “She’s not so crazy on the food question.”

“Poor child,” said Judge Duffy, “she is well dressed, and a lady. Her English is perfect, and I would stake everything on her being a good girl. I am positive she is somebody’s darling.”

At this announcement everybody laughed, and I put my handkerchief over my face and endeavored to choke the laughter that threatened to spoil my plans, in despite of my resolutions.

“I mean she is some woman’s darling,” hastily amended the judge. “I am sure some one is searching for her. Poor girl, I will be good to her, for she looks like my sister, who is dead.”

There was a hush for a moment after this announcement, and the officers glanced at me more kindly, while I silently blessed the kind-hearted judge, and hoped that any poor creatures who might be afflicted as I pretended to be should have as kindly a man to deal with as Judge Duffy.

“I wish the reporters were here,” he said at last. “They would be able to find out something about her.”

I got very much frightened at this, for if there is any one who can ferret out a mystery it is a reporter. I felt that I would rather face a mass of expert doctors, policemen, and detectives than two bright specimens of my craft, so I said:

“I don’t see why all this is needed to help me find my trunks. These men are impudent, and I do not want to be stared at. I will go away. I don’t want to stay here.”

So saying, I pulled down my veil and secretly hoped the reporters would be detained elsewhere until I was sent to the asylum.

“I don’t know what to do with the poor child,” said the worried judge. “She must be taken care of.”

“Send her to the Island,” suggested one of the officers.

“Oh, don’t!” said Mrs. Stanard, in evident alarm. “Don’t! She is a lady and it would kill her to be put on the Island.”

For once I felt like shaking the good woman. To think the Island was just the place I wanted to reach and here she was trying to keep me from going there! It was very kind of her, but rather provoking under the circumstances.

“There has been some foul work here,” said the judge. “I believe this child has been drugged and brought to this city. Make out the papers and we will send her to Bellevue for examination. Probably in a few days the effect of the drug will pass off and she will be able to tell us a story that will be startling. If the reporters would only come!”

I dreaded them, so I said something about not wishing to stay there any longer to be gazed at. Judge Duffy then told Policeman Bockert to take me to the back office. After we were seated there Judge Duffy came in and asked me if my home was in Cuba.

“Yes,” I replied, with a smile. “How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew it, my dear. Now, tell me were was it? In what part of Cuba?”

“On the hacienda,” I replied.

“Ah,” said the judge, “on a farm. Do you remember Havana?”

“Si, senor,” I answered; “it is near home. How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew all about it. Now, won’t you tell me the name of your home?” he asked, persuasively.

“That’s what I forget,” I answered, sadly. “I have a headache all the time, and it makes me forget things. I don’t want them to trouble me. Everybody is asking me questions, and it makes my head worse,” and in truth it did.

“Well, no one shall trouble you any more. Sit down here and rest awhile,” and the genial judge left me alone with Mrs. Stanard.

Just then an officer came in with a reporter. I was so frightened, and thought I would be recognized as a journalist, so I turned my head away and said, “I don’t want to see any reporters; I will not see any; the judge said I was not to be troubled.”

“Well, there is no insanity in that,” said the man who had brought the reporter, and together they left the room. Once again I had a fit of fear. Had I gone too far in not wanting to see a reporter, and was my sanity detected? If I had given the impression that I was sane, I was determined to undo it, so I jumped up and ran back and forward through the office, Mrs. Stanard clinging terrified to my arm.

“I won’t stay here; I want my trunks! Why do they bother me with so many people?” and thus I kept on until the ambulance surgeon came in, accompanied by the judge.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter IV: Judge Duffy and the Police)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

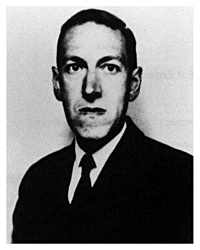

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka

Forschungen eines Hundes

Wie sich mein Leben verändert hat und wie es sich doch nicht verändert hat im Grunde! Wenn ich jetzt zurückdenke und die Zeiten mir zurückrufe, da ich noch inmitten der Hundeschaft lebte, teilnahm an allem, was sie bekümmert, ein Hund unter Hunden, finde ich bei näherem Zusehen doch, daß hier seit jeher etwas nicht stimmte, eine kleine Bruchstelle vorhanden war, ein leichtes Unbehagen inmitten der ehrwürdigsten volklichen Veranstaltungen mich befiel, ja manchmal selbst im vertrauten Kreise, nein, nicht manchmal, sondern sehr oft, der bloße Anblick eines mir lieben Mithundes, der bloße Anblick, irgendwie neu gesehen, mich verlegen, erschrocken, hilflos, ja mich verzweifelt machte. Ich suchte mich gewissermaßen zu begütigen, Freunde, denen ich es eingestand, halfen mir, es kamen wieder ruhigere Zeiten – Zeiten, in denen zwar jene Überraschungen nicht fehlten, aber gleichmütiger aufgenommen, gleichmütiger ins Leben eingefügt wurden, vielleicht traurig und müde machten, aber im übrigen mich bestehen ließen als einen zwar ein wenig kalten, zurückhaltenden, ängstlichen, rechnerischen, aber alles in allem genommen doch regelrechten Hund. Wie hätte ich auch ohne die Erholungspausen das Alter erreichen können, dessen ich mich jetzt erfreue, wie hätte ich mich durchringen können zu der Ruhe, mit der ich die Schrecken meiner Jugend betrachte und die Schrecken des Alters ertrage, wie hätte ich dazu kommen können, die Folgerungen aus meiner, wie ich zugebe, unglücklichen oder, um es vorsichtiger auszudrücken, nicht sehr glücklichen Anlage zu ziehen und fast völlig ihnen entsprechend zu leben. Zurückgezogen, einsam, nur mit meinen hoffnungslosen, aber mir unentbehrlichen kleinen Untersuchungen beschäftigt, so lebe ich, habe aber dabei von der Ferne den Überblick über mein Volk nicht verloren, oft dringen Nachrichten zu mir und auch ich lasse hie und da von mir hören. Man behandelt mich mit Achtung, versteht meine Lebensweise nicht, aber nimmt sie mir nicht übel, und selbst junge Hunde, die ich hier und da in der Ferne vorüberlaufen sehe, eine neue Generation, an deren Kindheit ich mich kaum dunkel erinnere, versagen mir nicht den ehrerbietigen Gruß.

Man darf eben nicht außer acht lassen, daß ich trotz meinen Sonderbarkeiten, die offen zutage liegen, doch bei weitem nicht völlig aus der Art schlage. Es ist ja, wenn ichs bedenke – und dies zu tun habe ich Zeit und Lust und Fähigkeit -, mit der Hundeschaft überhaupt wunderbar bestellt. Es gibt außer uns Hunden vierlei Arten von Geschöpfen ringsumher, arme, geringe, stumme, nur auf gewisse Schreie eingeschränkte Wesen, viele unter uns Hunden studieren sie, haben ihnen Namen gegeben, suchen ihnen zu helfen, sie zu erziehen, zu veredeln und dergleichen. Mir sind sie, wenn sie mich nicht etwa zu stören versuchen, gleichgültig, ich verwechsle sie, ich sehe über sie hinweg. Eines aber ist zu auffallend, als daß es mir hätte entgehen können, wie wenig sie nämlich mit uns Hunden verglichen, zusammenhalten, wie fremd und stumm und mit einer gewissen Feindseligkeit sie aneinander vorübergehen, wie nur das gemeinste Interesse sie ein wenig äußerlich verbinden kann und wie selbst aus diesem Interesse oft noch Haß und Streit entsteht. Wir Hunde dagegen! Man darf doch wohl sagen, daß wir alle förmlich in einem einzigen Haufen leben, alle, so unterschieden wir sonst durch die unzähligen und tiefgehenden Unterscheidungen, die sich im Laufe der Zeiten ergeben haben. Alle in einem Haufen! Es drängt uns zueinander und nichts kann uns hindern, diesem Drängen genugzutun, alle unsere Gesetze und Einrichtungen, die wenigen, die ich noch kenne und die zahllosen, die ich vergessen habe, gehen zurück auf die Sehnsucht nach dem größten Glück, dessen wir fähig sind, dem warmen Beisammensein. Nun aber das Gegenspiel hierzu. Kein Geschöpf lebt meines Wissens so weithin zerstreut wie wir Hunde, keines hat so viele, gar nicht übersehbare Unterschiede der Klassen, der Arten, der Beschäftigungen. Wir, die wir zusammenhalten wollen, – und immer wieder gelingt es uns trotz allem in überschwenglichen Augenblicken – gerade wir leben weit von einander getrennt, in eigentümlichen, oft schon dem Nebenhund unverständlichen Berufen, festhaltend an Vorschriften, die nicht die der Hundeschaft sind; ja, eher gegen sie gerichtet. Was für schwierige Dinge das sind, Dinge, an die man lieber nicht rührt – ich verstehe auch diesen Standpunkt, verstehe ihn besser als den meinen -, und doch Dinge, denen ich ganz und gar verfallen bin. Warum tue ich es nicht wie die anderen, lebe einträchtig mit meinem Volke und nehme das, was die Eintracht stört, stillschweigend hin, vernachlässige es als kleinen Fehler in der großen Rechnung, und bleibe immer zugekehrt dem, was glücklich bindet, nicht dem, was, freilich immer wieder unwiderstehlich, uns aus dem Volkskreis zerrt.

Ich erinnere mich an einen Vorfall aus meiner Jugend, ich war damals in einer jener seligen, unerklärlichen Aufregungen, wie sie wohl jeder als Kind erlebt, ich war noch ein ganz junger Hund, alles gefiel mir, alles hatte Bezug zu mir, ich glaubte, daß große Dinge um mich vorgehen, deren Anführer ich sei, denen ich meine Stimme leihen müsse, Dinge, die elend am Boden liegenbleiben müßten, wenn ich nicht für sie lief, für sie meinen Körper schwenkte, nun, Phantasien der Kinder, die mit den Jahren sich verflüchtigen. Aber damals waren sie stark, ich war ganz in ihrem Bann, und es geschah dann auch freilich etwas Außerordentliches, was den wilden Erwartungen Recht zu geben schien. An sich war es nichts Außerordentliches, später habe ich solche und noch merkwürdigere Dinge oft genug gesehen, aber damals traf es mich mit dem starken, ersten, unverwischbaren, für viele folgende richtunggebenden Eindruck. Ich begegnete nämlich einer kleinen Hundegesellschaft, vielmehr, ich begegnete ihr nicht, sie kam auf mich zu. Ich war damals lange durch die Finsternis gelaufen, in Vorahnung großer Dinge – eine Vorahnung, die freilich leicht täuschte, denn ich hatte sie immer-, war lange durch die Finsternis gelaufen, kreuz und quer, blind und taub für alles, geführt von nichts als dem unbestimmten Verlangen, machte plötzlich halt in dem Gefühl, hier sei ich am rechten Ort, sah auf und es war überheller Tag, nur ein wenig dunstig, alles voll durcheinander wogender, berauschender Gerüche, ich begrüßte den Morgen mit wirren Lauten, da – als hätte ich sie heraufbeschworen – traten aus irgendwelcher Finsternis unter Hervorbringung eines entsetzlichen Lärms, wie ich ihn noch nie gehört hatte, sieben Hunde ans Licht. Hätte ich nicht deutlich gesehen, daß es Hunde waren und daß sie selbst diesen Lärm mitbrachten, obwohl ich nicht erkennen konnte, wie sie ihn erzeugten – ich wäre sofort weggelaufen, so aber blieb ich. Damals wußte ich noch fast nichts von der nur dem Hundegeschlecht verliehenen schöpferischen Musikalität, sie war meiner sich erst langsam entwickelnden Beobachtungskraft bisher natürlicherweise entgangen, hatte mich doch die Musik schon seit meiner Säuglingszeit umgeben als ein mir selbstverständliches, unentbehrliches Lebenselement, welches von meinem sonstigen Leben zu sondern nichts mich zwang, nur in Andeutungen, dem kindlichen Verstand entsprechend, hatte man mich darauf hinzuweisen versucht, um so überraschender, geradezu niederwerfend waren jene sieben großen Musikkünstler für mich. Sie redeten nicht, sie sangen nicht, sie schwiegen im allgemeinen fast mit einer großen Verbissenheit, aber aus dem leeren Raum zauberten sie die Musik empor. Alles war Musik, das Heben und Niedersetzen ihrer Füße, bestimmte Wendungen des Kopfes, ihr Laufen und ihr Ruhen, die Stellungen, die sie zueinander einnahmen, die reigenmäßigen Verbindungen, die sie miteinander eingingen, indem etwa einer die Vorderpfoten auf des anderen Rücken stützte und sie sich dann so ordneten, daß der erste aufrecht die Last aller andern trug, oder indem sie mit ihren nah am Boden hinschleichenden Körpern verschlungene Figuren bildeten und niemals sich irrten; nicht einmal der letzte, der noch ein wenig unsicher war, nicht immer gleich den Anschluß an die andern fand, gewissermaßen im Anschlagen der Melodie manchmal schwankte, aber doch unsicher war nur im Vergleich mit der großartigen Sicherheit der anderen und selbst bei viel größerer, ja bei vollkommener Unsicherheit nichts hätte verderben können, wo die anderen, große Meister, den Takt unerschütterlich hielten. Aber man sah sie ja kaum, man sah sie ja alle kaum. Sie waren hervorgetreten, man hatte sie innerlich begrüßt als Hunde, sehr beirrt war man zwar von dem Lärm, der sie begleitete, aber es waren doch Hunde, Hunde wie ich und du, man beobachtete sie gewohnheitsmäßig, wie Hunde, denen man auf dem Weg begegnet, man wollte sich ihnen nähern, Grüße tauschen, sie waren auch ganz nah, Hunde, zwar viel älter als ich und nicht von meiner langhaarigen wolligen Art, aber doch auch nicht allzu fremd an Größe und Gestalt, recht vertraut vielmehr, viele von solcher oder ähnlicher Art kannte ich, aber während man noch in solchen Überlegungen befangen war, nahm allmählich die Musik überhand, faßte einen förmlich, zog einen hinweg von diesen wirklichen kleinen Hunden und, ganz wider Willen, sich sträubend mit allen Kräften, heulend, als würde einem Schmerz bereitet, durfte man sich mit nichts anderem beschäftigen, als mit der von allen Seiten, von der Höhe, von der Tiefe, von überall her kommenden, den Zuhörer in die Mitte nehmenden, überschüttenden, erdrückenden, über seiner Vernichtung noch in solcher Nähe, daß es schon Ferne war, kaum hörbar noch Fanfaren blasenden Musik. Und wieder wurde man entlassen, weil man schon zu erschöpft, zu vernichtet, zu schwach war, um noch zu hören, man wurde entlassen und sah die sieben kleinen Hunde ihre Prozessionen führen, ihre Sprünge tun, man wollte sie, so ablehnend sie aussahen, anrufen, um Belehrung bitten, sie fragen, was sie denn hier machten – ich war ein Kind und glaubte immer und jeden fragen zu dürfen -, aber kaum setzte ich an, kaum fühlte ich die gute, vertraute, hündische Verbindung mit den sieben, war wieder ihre Musik da, machte mich besinnungslos, drehte mich im Kreis herum, als sei ich selbst einer der Musikanten, während ich doch nur ihr Opfer war, warf mich hierhin und dorthin, so sehr ich auch um Gnade bat, und rettete mich schließlich vor ihrer eigenen Gewalt, indem sie mich in ein Gewirr von Hölzern drückte, das in jener Gegend ringsum sich erhob, ohne daß ich es bisher bemerkt hatte, mich jetzt fest umfing, den Kopf mir niederduckte und mir, mochte dort im Freien die Musik noch donnern, die Möglichkeit gab, ein wenig zu verschnaufen. Wahrhaftig, mehr als über die Kunst der sieben Hunde – sie war mir unbegreiflich, aber auch gänzlich unanknüpfbar außerhalb meiner Fähigkeiten -, wunderte ich mich über ihren Mut, sich dem, was sie erzeugten, völlig und offen auszusetzen, und über ihre Kraft, es, ohne daß es ihnen das Rückgrat brach, ruhig zu ertragen. Freilich erkannte ich jetzt aus meinem Schlupfloch bei genauerer Beobachtung, daß es nicht so sehr Ruhe, als äußerste Anspannung war, mit der sie arbeiteten, diese scheinbar so sicher bewegten Beine zitterten bei jedem Schritt in unaufhörlicher ängstlicher Zuckung, starr wie in Verzweiflung sah einer den anderen an, und die immer wieder bewältigte Zunge hing doch gleich wieder schlapp aus den Mäulern. Es konnte nicht Angst wegen des Gelingens sein, was sie so erregte; wer solches wagte, solches zustande brachte, der konnte keine Angst mehr haben. – Wovor denn Angst? Wer zwang sie denn zu tun, was sie hier taten? Und ich konnte mich nicht mehr zurückhalten, besonders da sie mir jetzt so unverständlich hilfsbedürftig erschienen, und so rief ich durch allen Lärm meine Fragen laut und fordernd hinaus. Sie aber – unbegreiflich! unbegreiflich! – sie antworteten nicht, taten, als wäre ich nicht da. Hunde, die auf Hundeanruf gar nicht antworten, ein Vergehen gegen die guten Sitten, das dem kleinsten wie dem größten Hunde unter keinen Umständen verziehen wird. Waren es etwa doch nicht Hunde? Aber wie sollten es denn nicht Hunde sein, hörte ich doch jetzt bei genauerem Hinhorchen sogar leise Zurufe, mit denen sie einander befeuerten, auf Schwierigkeiten aufmerksam machten, vor Fehlern warnten, sah ich doch den letzten kleinsten Hund, dem die meisten Zurufe galten, öfters nach mir hinschielen, so als hätte er viel Lust, mir zu antworten, bezwänge sich aber, weil es nicht sein dürfe. Aber warum durfte es nicht sein, warum durfte denn das, was unsere Gesetze bedingungslos immer verlangen, diesmal nicht sein? Das empörte sich in mir, fast vergaß ich die Musik. Diese Hunde hier vergingen sich gegen das Gesetz. Mochten es noch so große Zauberer sein, das Gesetz galt auch für sie, das verstand ich Kind schon ganz genau. Und ich merkte von da aus noch mehr. Sie hatten wirklich Grund zu schweigen, vorausgesetzt, daß sie aus Schuldgefühl schwiegen. Denn wie führten sie sich auf, vor lauter Musik hatte ich es bisher nicht bemerkt, sie hatten ja alle Scham von sich geworfen, die elenden taten das gleichzeitig Lächerlichste und Unanständigste, sie gingen aufrecht auf den Hinterbeinen. Pfui Teufel! Sie entblößten sich und trugen ihre Blöße protzig zur Schau: sie taten sich darauf zugute, und wenn sie einmal auf einen Augenblick dem guten Trieb gehorchten und die Vorderbeine senkten, erschraken sie förmlich, als sei es ein Fehler, als sei die Natur ein Fehler, hoben wieder schnell die Beine und ihr Blick schien um Verzeihung dafür zu bitten, daß sie in ihrer Sündhaftigkeit ein wenig hatten innehalten müssen. War die Welt verkehrt? Wo war ich? Was war denn geschehen? Hier durfte ich um meines eigenen Bestandes willen nicht mehr zögern, ich machte mich los aus den umklammernden Hölzern, sprang mit einem Satz hervor und wollte zu den Hunden, ich kleiner Schüler mußte Lehrer sein, mußte ihnen begreiflich machen, was sie taten, mußte sie abhalten vor weiterer Versündigung. »So alte Hunde, so alte Hunde!« wiederholte ich mir immerfort. Aber kaum war ich frei und nur noch zwei, drei Sprünge trennten mich von den Hunden, war es wieder der Lärm, der seine Macht über mich bekam. Vielleicht hätte ich in meinem Eifer sogar ihm, den ich doch nun schon kannte, widerstanden, wenn nicht durch alle seine Fülle, die schrecklich war, aber vielleicht doch zu bekämpfen, ein klarer, strenger, immer sich gleich bleibender, förmlich aus großer Ferne unverändert ankommender Ton, vielleicht die eigentliche Melodie inmitten des Lärms, geklungen und mich in die Knie gezwungen hätte. Ach, was machten doch diese Hunde für eine betörende Musik. Ich konnte nicht weiter, ich wollte sie nicht mehr belehren, mochten sie weiter die Beine spreizen, Sünden begehen und andere zur Sünde des stillen Zuschauens verlocken, ich war ein so kleiner Hund, wer konnte so Schweres von mir verlangen? Ich machte mich noch kleiner, als ich war, ich winselte, hätten mich danach die Hunde um meine Meinung gefragt, ich hätte ihnen vielleicht recht gegeben. Es dauerte übrigens nicht lange und sie verschwanden mit allem Lärm und allem Licht in der Finsternis, aus der sie gekommen waren.

Wie ich schon sagte: dieser ganze Vorfall enthielt nichts Außergewöhnliches, im Verlauf eines langen Lebens begegnet einem mancherlei, was, aus dem Zusammenhang genommen und mit den Augen eines Kindes angesehen, noch viel erstaunlicher wäre. Überdies kann man es natürlich – wie der treffende Ausdruck lautet – >verreden<, so wie alles, dann zeigt sich, daß hier sieben Musiker zusammengekommen waren, um in der Stille des Morgens Musik zu machen, daß ein kleiner Hund sich hinverirrt hatte, ein lästiger Zuhörer, den sie durch besonders schreckliche oder erhabene Musik leider vergeblich zu vertreiben suchten. Er störte sie durch Fragen, hätten sie, die schon durch die bloße Anwesenheit des Fremdlings genug gestört waren, auch noch auf diese Belästigung eingehen und sie durch Antworten vergrößern sollen? Und wenn auch das Gesetz befiehlt, jedem zu antworten, ist denn ein solcher winziger, hergelaufener Hund überhaupt ein nennenswerter Jemand? Und vielleicht verstanden sie ihn gar nicht, er bellte ja doch wohl seine Fragen recht unverständlich. Oder vielleicht verstanden sie ihn wohl und antworteten in Selbstüberwindung, aber er, der Kleine, der Musik-Ungewohnte, konnte die Antwort von der Musik nicht sondern. Und was die Hinterbeine betrifft, vielleicht gingen sie wirklich ausnahmsweise nur auf ihnen, es ist eine Sünde, wohl! Aber sie waren allein, sieben Freunde unter Freunden, im vertraulichen Beisammensein, gewissermaßen in den eigenen vier Wänden, gewissermaßen ganz allein, denn Freunde sind doch keine Öffentlichkeit und wo keine Öffentlichkeit ist, bringt sie auch ein kleiner, neugieriger Straßenhund nicht hervor, in diesem Fall aber: ist es hier nicht so, als wäre nichts geschehen? Ganz so ist es nicht, aber nahezu, und die Eltern sollten ihre Kleinen weniger herumlaufen und dafür besser schweigen und das Alter achten lehren.

Ist man soweit, dann ist der Fall erledigt. Freilich, was für die Großen erledigt ist, ist es für die Kleinen noch nicht. Ich lief umher, erzählte und fragte, klagte an und forschte und wollte jeden hinziehen zu dem Ort, wo alles geschehen war, und wollte jedem zeigen, wo ich gestanden war und wo die sieben gewesen und wo und wie sie getanzt und musiziert hatten und, wäre jemand mit mir gekommen, statt daß mich jeder abgeschüttelt und ausgelacht hätte, ich hätte dann wohl meine Sündlosigkeit geopfert und mich auch auf die Hinterbeine zu stellen versucht, um alles genau zu verdeutlichen. Nun, einem Kinde nimmt man alles übel, verzeiht ihm aber schließlich auch alles. Ich aber habe dieses kindhafte Wesen behalten und bin darüber ein alter Hund geworden. So wie ich damals nicht aufhörte, jenen Vorfall, den ich allerdings heute viel niedriger einschätze, laut zu besprechen, in seine Bestandteile zu zerlegen, an den Anwesenden zu messen ohne Rücksicht auf die Gesellschaft, in der ich mich befand, nur immer mit der Sache beschäftigt, die ich lästig fand genau so wie jeder andere, die ich aber – das war der Unterschied – gerade deshalb restlos durch Untersuchung auflösen wollte, um den Blick endlich wieder freizubekommen für das gewöhnliche, ruhige, glückliche Leben des Tages. Ganz so wie damals habe ich, wenn auch mit weniger kindlichen Mitteln – aber sehr groß ist der Unterschied nicht – in der Folgezeit gearbeitet und halte auch heute nicht weiter.

Mit jenem Konzert aber begann es. Ich klage nicht darüber, es ist mein eingeborenes Wesen, das hier wirkt und das sich gewiß, wenn das Konzert nicht gewesen wäre, eine andere Gelegenheit gesucht hätte, um durchzubrechen. Nur daß es so bald geschah, tat mir früher manchmal leid, es hat mich um einen großen Teil meiner Kindheit gebracht, das glückselige Leben der jungen Hunde, das mancher für sich jahrelang auszudehnen imstande ist, hat für mich nur wenige kurze Monate gedauert. Sei’s drum. Es gibt wichtigere Dinge als die Kindheit. Und vielleicht winkt mir im Alter, erarbeitet durch ein hartes Leben, mehr kindliches Glück, als ein wirkliches Kind zu ertragen die Kraft hätte, die ich dann aber haben werde.

Ich begann damals meine Untersuchungen mit den einfachsten Dingen, an Material fehlte es nicht, leider, der Überfluß ist es, der mich in dunklen Stunden verzweifeln läßt. Ich begann zu untersuchen, wovon sich die Hundeschaft nährt. Das ist nun, wenn man will, natürlich keine einfache Frage, sie beschäftigt uns seit Urzeiten, sie ist der Hauptgegenstand unseres Nachdenkens, zahllos sind die Beobachtungen und Versuche und Ansichten auf diesem Gebiete, es ist eine Wissenschaft geworden, die in ihren ungeheuren Ausmaßen nicht nur über die Fassungskraft des einzelnen, sondern über jene aller Gelehrten insgesamt geht und ausschließlich von niemandem anderen als von der gesamten Hundeschaft und selbst von dieser nur seufzend und nicht ganz vollständig getragen werden kann, immer wieder abbröckelt in altem, längst besessenem Gut und mühselig ergänzt werden muß, von den Schwierigkeiten und kaum zu erfüllenden Voraussetzungen meiner Forschung ganz zu schweigen. Das alles wende man mir nicht ein, das alles weiß ich, wie nur irgendein Durchschnittshund, es fällt mir nicht ein, mich in die wahre Wissenschaft zu mengen, ich habe alle Ehrfurcht vor ihr, die ihr gebührt, aber sie zu vermehren fehlt es mir an Wissen und Fleiß und Ruhe und – nicht zuletzt, besonders seit einigen Jahren – auch an Appetit. Ich schlinge das Essen hinunter, aber der geringsten vorgängigen geordneten landwirtschaftlichen Betrachtung ist es mir nicht wert. Mir genügt in dieser Hinsicht der Extrakt aller Wissenschaft, die kleine Regel, mit welcher die Mütter die Kleinen von ihren Brüsten ins Leben entlassen: »Mache alles naß, soviel du kannst.« Und ist hier nicht wirklich fast alles enthalten? Was hat die Forschung, von unseren Urvätern angefangen, entscheidend Wesentliches denn hinzuzufügen? Einzelheiten, Einzelheiten und wie unsicher ist alles. Diese Regel aber wird bestehen, solange wir Hunde sind. Sie betrifft unsere Hauptnahrung. Gewiß, wir haben noch andere Hilfsmittel, aber im Notfall und wenn die Jahre nicht zu schlimm sind, könnten wir von dieser Hauptnahrung leben, diese Hauptnahrung finden wir auf der Erde, die Erde aber braucht unser Wasser, nährt sich von ihm, und nur für diesen Preis gibt sie uns unsere Nahrung, deren Hervorkommen man allerdings, dies ist auch nicht zu vergessen, durch bestimmte Sprüche, Gesänge, Bewegungen beschleunigen kann. Das ist aber meiner Meinung nach alles; von dieser Seite her ist über diese Sache grundsätzlich nicht mehr zu sagen. Hierin bin ich auch einig mit der ganzen Mehrzahl der Hundeschaft und von allen in dieser Hinsicht ketzerischen Ansichten wende ich mich streng ab. Wahrhaftig, es geht mir nicht um Besonderheiten, um Rechthaberei, ich bin glücklich, wenn ich mit den Volksgenossen übereinstimmen kann, und in diesem Falle geschieht es. Meine eigenen Unternehmungen gehen aber in anderer Richtung. Der Augenschein lehrt mich, daß die Erde, wenn sie nach den Regeln der Wissenschaft besprengt und bearbeitet wird, die Nahrung hergibt, und zwar in solcher Qualität, in solcher Menge, auf solche Art, an solchen Orten, zu solchen Stunden, wie es die gleichfalls von der Wissenschaft ganz oder teilweise festgestellten Gesetze verlangen. Das nehme ich hin, meine Frage aber ist: »Woher nimmt die Erde diese Nahrung?« Eine Frage, die man im allgemeinen nicht zu verstehen vorgibt und auf die man mir bestenfalls antwortet: »Hast du nicht genug zu essen, werden wir dir von dem unseren geben.« Man beachte diese Antwort. Ich weiß: Es gehört nicht zu den Vorzügen der Hundeschaft, daß wir Speisen, die wir einmal erlangt haben, zur Verteilung bringen. Das Leben ist schwer, die Erde spröde, die Wissenschaft reich an Erkenntnissen, aber arm genug an praktischen Erfolgen; wer Speise hat, behält sie; das ist nicht Eigennutz, sondern das Gegenteil, ist Hundegesetz, ist einstimmiger Volksbeschluß, hervorgegangen aus Überwindung der Eigensucht, denn die Besitzenden sind ja immer in der Minderzahl. Und darum ist jene Antwort: »Hast du nicht genug zu essen, werden wir dir von dem unseren geben« eine ständige Redensart, ein Scherzwort, eine Neckerei. Ich habe das nicht vergessen. Aber eine um so größere Bedeutung hatte es für mich, daß man mir gegenüber, damals als ich mich mit meinen Fragen in der Welt umhertrieb, den Spott beiseiteließ – man gab mir zwar noch immer nichts zu essen – woher hätte man es gleich nehmen sollen -, und wenn man es gerade zufällig hatte, vergaß man natürlich in der Raserei des Hungers jede andere Rücksicht, aber das Angebot meinte man ernst, und hie und da bekam ich dann wirklich eine Kleinigkeit, wenn ich schnell genug dabei war, sie an mich zu reißen. Wie kam es, daß man sich zu mir so besonders verhielt, mich schonte, mich bevorzugte? Weil ich ein magerer, schwacher Hund war, schlecht genährt und zu wenig um Nahrung besorgt? Aber es laufen viele schlecht genährte Hunde herum und man nimmt ihnen selbst die elendste Nahrung vor dem Mund weg, wenn man es kann, oft nicht aus Gier, sondern meist aus Grundsatz. Nein, man bevorzugte mich, ich konnte es nicht so sehr mit Einzelheiten belegen, als daß ich vielmehr den bestimmten Eindruck dessen hatte. Waren es also meine Fragen, über die man sich freute, die man für besonders klug ansah? Nein, man freute sich nicht und hielt sie alle für dumm. Und doch konnten es nur die Fragen sein, die mir die Aufmerksamkeit erwarben. Es war, als wolle man lieber das Ungeheuerliche tun, mir den Mund mit Essen zustopfen – man tat es nicht, aber man wollte es -, als meine Fragen dulden. Aber dann hätte man mich doch besser verjagen können und meine Fragen sich verbitten. Nein, das wollte man nicht, man wollte zwar meine Fragen nicht hören, aber gerade wegen dieser meiner Fragen wollte man mich nicht verjagen. Es war, so sehr ich ausgelacht, als dummes, kleines Tier behandelt, hin- und hergeschoben wurde, eigentlich die Zeit meines größten Ansehens, niemals hat sich später etwas derartiges wiederholt, überall hatte ich Zutritt, nichts wurde mir verwehrt, unter dem Vorwand rauher Behandlung wurde mir eigentlich geschmeichelt. Und alles also doch nur wegen meiner Fragen, wegen meiner Ungeduld, wegen meiner Forschungsbegierde. Wollte man mich damit einlullen, ohne Gewalt, fast liebend mich von einem falschen Wege abbringen, von einem Wege, dessen Falschheit doch nicht so über allem Zweifel stand, daß sie erlaubt hätte, Gewalt anzuwenden? – Auch hielt eine gewisse Achtung und Furcht von Gewaltanwendung ab. Ich ahnte schon damals etwas derartiges, heute weiß ich es genau, viel genauer als die, welche es damals taten, es ist wahr, man hat mich ablocken wollen von meinem Wege. Es gelang nicht, man erreichte das Gegenteil, meine Aufmerksamkeit verschärfte sich. Es stellte sich mir sogar heraus, daß ich es war, der die andern verlocken wollte, und daß mir tatsächlich die Verlockung bis zu einem gewissen Grade gelang. Erst mit Hilfe der Hundeschaft begann ich meine eigenen Fragen zu verstehen. Wenn ich zum Beispiel fragte: Woher nimmt die Erde diese Nahrung, – kümmerte mich denn dabei, wie es den Anschein haben konnte, die Erde, kümmerten mich etwa der Erde Sorgen? Nicht im geringsten, das lag mir, wie ich bald erkannte, völlig fern, mich kümmerten nur die Hunde, gar nichts sonst. Denn was gibt es außer den Hunden? Wen kann man sonst anrufen in der weiten, leeren Welt? Alles Wissen, die Gesamtheit aller Fragen und aller Antworten ist in den Hunden enthalten. Wenn man nur dieses Wissen wirksam, wenn man es nur in den hellen Tag bringen könnte, wenn sie nur nicht so unendlich viel mehr wüßten, als sie zugestehen, als sie sich selbst zugestehen. Noch der redseligste Hund ist verschlossener, als es die Orte zu sein pflegen, wo die besten Speisen sind. Man umschleicht den Mithund, man schäumt vor Begierde, man prügelt sich selbst mit dem eigenen Schwanz, man fragt, man bittet, man heult, man beißt und erreicht – und erreicht das, was man auch ohne jede Anstrengung erreichen würde: liebevolles Anhören, freundliche Berührungen, ehrenvolle Beschnupperungen, innige Umarmungen, mein und dein Heulen mischt sich in eines, alles ist darauf gerichtet, ein Entzücken, Vergessen und Finden, aber das eine, was man vor allem erreichen wollte: Eingeständnis des Wissens, das bleibt versagt. Auf diese Bitte, ob stumm, ob laut, antworten bestenfalls, wenn man die Verlockung schon aufs äußerste getrieben hat, nur stumpfe Mienen, schiefe Blicke, verhängte, trübe Augen. Es ist nicht viel anders, als es damals war, da ich als Kind die Musikerhunde anrief und sie schwiegen.

Nun könnte man sagen: »Du beschwerst dich über deine Mithunde, über ihre Schweigsamkeit hinsichtlich der entscheidenden Dinge, du behauptest, sie wüßten mehr, als sie eingestehen, mehr, als sie im Leben gelten lassen wollen, und dieses Verschweigen, dessen Grund und Geheimnis sie natürlich auch noch mitverschweigen, vergifte das Leben, mache es dir unerträglich, du müßtest es ändern oder es verlassen, mag sein, aber du bist doch selbst ein Hund, hast auch das Hundewissen, nun sprich es aus, nicht nur in Form der Frage, sondern als Antwort. Wenn du es aussprichst, wer wird dir widerstehen? Der große Chor der Hundeschaft wird einfallen, als hätte er darauf gewartet. Dann hast du Wahrheit, Klarheit, Eingeständnis, soviel du nur willst. Das Dach dieses niedrigen Lebens, dem du so Schlimmes nachsagst, wird sich öffnen und wir werden alle, Hund bei Hund, aufsteigen in die hohe Freiheit. Und sollte das Letzte nicht gelingen, sollte es schlimmer werden als bisher, sollte die ganze Wahrheit unerträglicher sein als die halbe, sollte sich bestätigen, daß die Schweigenden als Erhalter des Lebens im Rechte sind, sollte aus der leisen Hoffnung, die wir jetzt noch haben, völlige Hoffnungslosigkeit werden, des Versuches ist das Wort doch wert, da du so, wie du leben darfst, nicht leben willst. Nun also, warum machst du den anderen ihre Schweigsamkeit zum Vorwurf und schweigst selbst?« Leichte Antwort: Weil ich ein Hund bin. Im Wesentlichen genau so wie die anderen fest verschlossen, Widerstand leistend den eigenen Fragen, hart aus Angst. Frage ich denn, genau genommen, zumindest seit ich erwachsen bin, die Hundeschaft deshalb, damit sie mir antwortet? Habe ich so törichte Hoffnungen? Sehe ich die Fundamente unseres Lebens, ahne ihre Tiefe, sehe die Arbeiter beim Bau, bei ihrem finstern Werk, und erwarte noch immer, daß auf meine Fragen hin alles dies beendigt, zerstört, verlassen wird? Nein, das erwarte ich wahrhaftig nicht mehr. Ich verstehe sie, ich bin Blut von ihrem Blut, von ihrem armen, immer wieder jungen, immer wieder verlangenden Blut. Aber nicht nur das Blut haben wir gemeinsam, sondern auch das Wissen und nicht nur das Wissen, sondern auch den Schlüssel zu ihm. Ich besitze es nicht ohne die anderen, ich kann es nicht haben ohne ihre Hilfe. – Eisernen Knochen, enthaltend das edelste Mark, kann man nur beikommen durch ein gemeinsames Beißen aller Zähne aller Hunde. Das ist natürlich nur ein Bild und übertrieben; wären alle Zähne bereit, sie müßten nicht mehr beißen, der Knochen würde sich öffnen und das Mark läge frei dem Zugriff des schwächsten Hündchens. Bleibe ich innerhalb dieses Bildes, dann zielen meine Absicht, meine Fragen, meine Forschungen allerdings auf etwas Ungeheuerliches. Ich will diese Versammlung aller Hunde erzwingen, will unter dem Druck ihres Bereitseins den Knochen sich öffnen lassen, will sie dann zu ihrem Leben, das ihnen lieb ist, entlassen und dann allein, weit und breit allein, das Mark einschlürfen. Das klingt ungeheuerlich, ist fast so, als wollte ich mich nicht vom Mark eines Knochens nur, sondern vom Mark der Hundeschaft selbst nähren. Doch es ist nur ein Bild. Das Mark, von dem hier die Rede ist, ist keine Speise, ist das Gegenteil, ist Gift.

Mit meinen Fragen hetze ich nur noch mich selbst, will mich anfeuern durch das Schweigen, das allein ringsum mir noch antwortet. Wie lange wirst du es ertragen, daß die Hundeschaft, wie du dir durch deine Forschungen immer mehr zu Bewußtsein bringst, schweigt und immer schweigen wird? Wie lange wirst du es ertragen, so lautet über allen Einzelfragen meine eigentliche Lebensfrage: sie ist nur an mich gestellt und belästigt keinen andern. Leider kann ich sie leichter beantworten als die Einzelfragen: Ich werde es voraussichtlich aushalten bis zu meinem natürlichen Ende, den unruhigen Fragen widersteht immer mehr die Ruhe des Alters. Ich werde wahrscheinlich schweigend, vom Schweigen umgeben, nahezu friedlich, sterben und ich sehe dem gefaßt entgegen. Ein bewundernswürdig starkes Herz, eine vorzeitig nicht abzunützende Lunge sind uns Hunden wie aus Bosheit mitgegeben, wir widerstehen allen Fragen, selbst den eigenen, Bollwerk des Schweigens, das wir sind.